Introduction

Melanoma is a highly aggressive malignancy arising

from the malignant transformation of melanocytes, neural

crest-derived cells located in the basal epidermis (1). Cutaneous melanoma (CM) is the

predominant subtype, accounting for >90% of new melanoma

diagnoses and ~75% of skin cancer-associated mortalities due to its

rapid systemic dissemination and high metastatic potential

(2,3). In autopsy studies, brain metastases

(MTS) have been observed in up to 74% of patients with advanced

melanoma (4).

Pregnancy-associated melanoma (PAM) is rare, with an

estimated incidence rate ranging from 1.4 to 8.5 cases per 100,000

pregnancies, based on data from European and U.S. studies (5–8).

Melanoma is also one of the few cancer types capable of

metastasizing to the placenta and fetus, accounting for

approximately one-third of all reported placental MTS (9). With placental involvement, the

transmission risk to the fetus is ~22%, placing such neonates at

high risk (10).

The therapeutic landscape of advanced melanoma has

been transformed by targeted inhibitors of the mitogen-activated

protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and immune checkpoint blockade

(11–13). However, systemic treatment during

pregnancy remains challenging due to concerns regarding

teratogenicity and limited available data. Only a few case reports

have described the use of the B-Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine

kinase (BRAF) inhibitor vemurafenib during pregnancy (14–17);

however, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the

first report documenting combined BRAF and mitogen-activated

protein kinase kinase (MEK) inhibition with dabrafenib and

trametinib (D + T) in a pregnant patient with melanoma brain

MTS.

The current report presents the clinical course of a

35-year-old woman diagnosed at 24 weeks of gestation with multiple

brain MTS from melanoma, who was managed with a multidisciplinary

approach, including neurosurgery, targeted therapy and subsequent

immunotherapy.

Case report

Patient history

The current study presents the case of a 35-year-old

pregnant woman with a history of superficial spreading melanoma on

the scalp. The primary tumor showed ulceration, vertical growth

phase, Clark's level IV (18) and a

Breslow thickness of 1.1 mm (19).

Initial treatment consisted of an excisional biopsy with narrow

resection margins (May 2021). Despite medical recommendations, a

radical re-excision of the tumor bed and sentinel lymph node biopsy

were not performed, mainly due to circumstances related to the

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

At the follow-up in January 2023, a whole-body

18F-FDG PET/CT revealed a non-specific pulmonary nodule

in the left anterior segment (S3) of the lung, without evidence of

MTS. The melanoma was staged as IIA (T2bN0M0) according to the

American Joint Committee on Cancer system (20). Systemic treatment was not indicated,

and routine surveillance was continued.

Presentation during pregnancy

In January 2024, ~3 years later, the patient

presented to the Academician Ladislav Dérer Hospital (University

Hospital Bratislava; Bratislava, Slovakia) at 24+2 weeks of

gestation with a brief episode of expressive aphasia that resolved

within 15 min. Upon admission, the neurological examination was

normal.

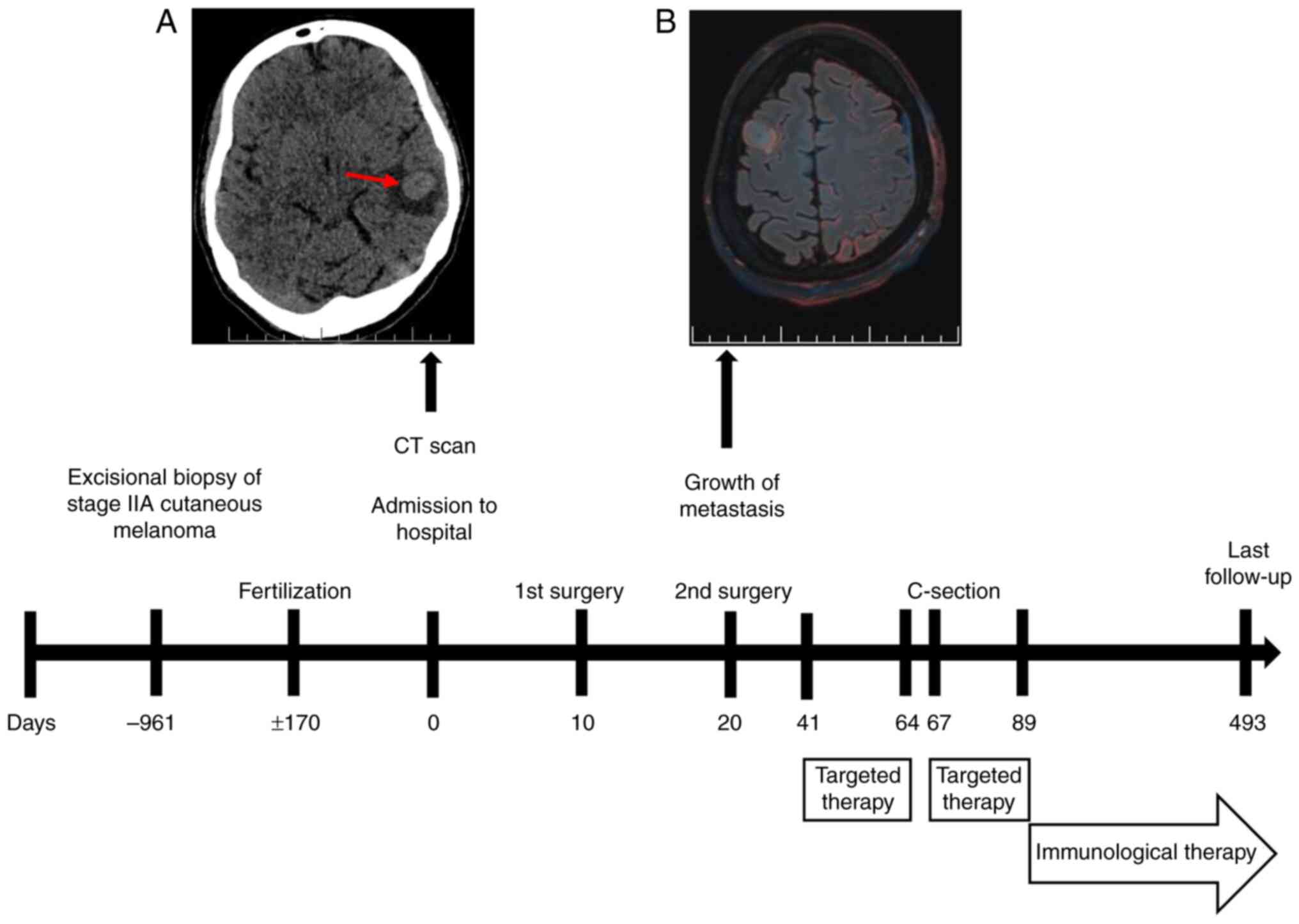

A non-contrast low-dose CT scan of the brain

revealed an intra-axial lesion in the left temporal lobe, with

perifocal edema (Fig. 1A). The

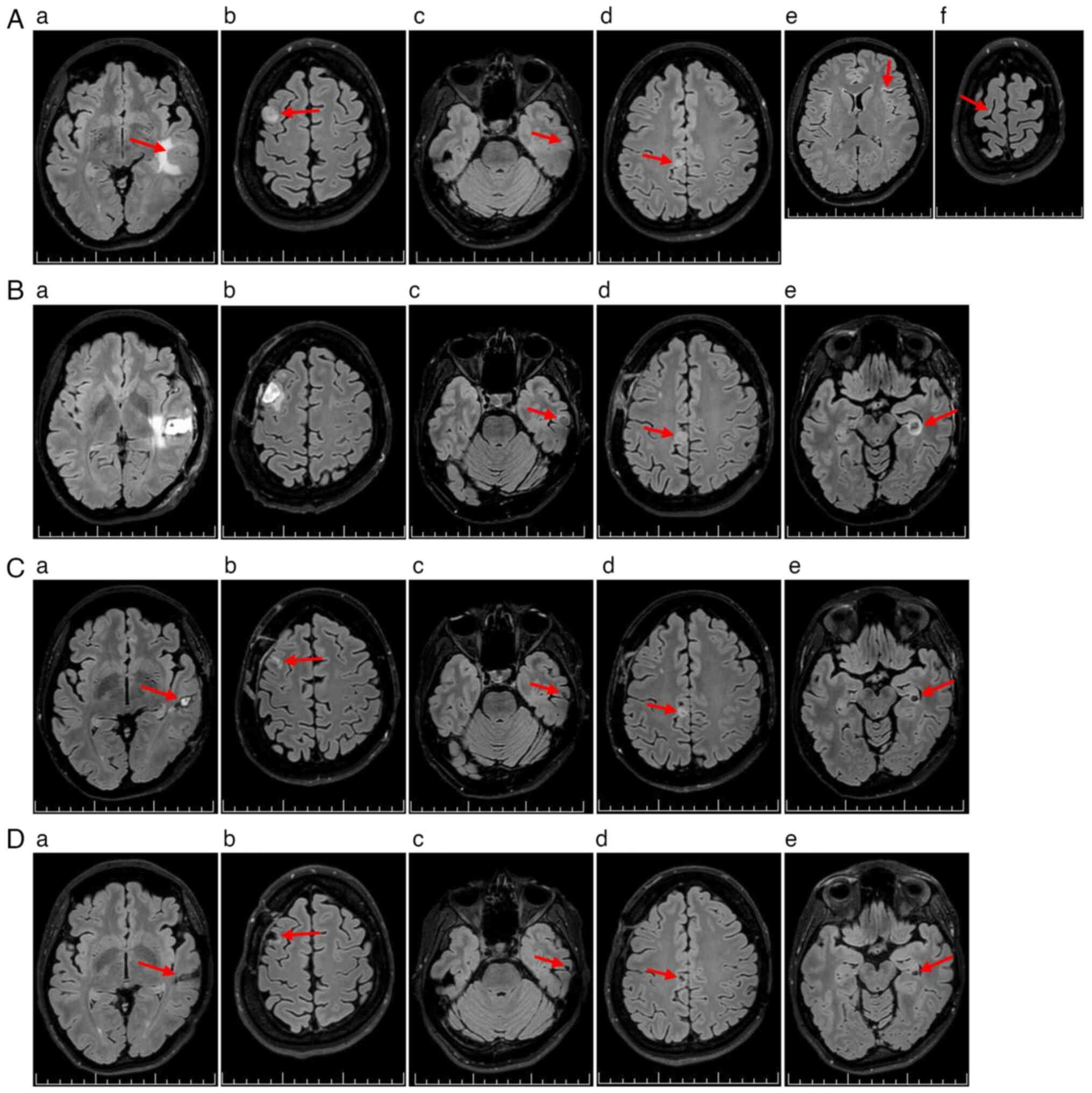

following day, non-contrast 3T brain MRI identified six

supratentorial lesions. A total of four lesions showed radiological

features consistent with MTS (Fig.

2Aa-Ad), while two small cortical hyperintensities on

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences were atypical but

suspicious for metastatic disease (Fig.

2Ae and Af).

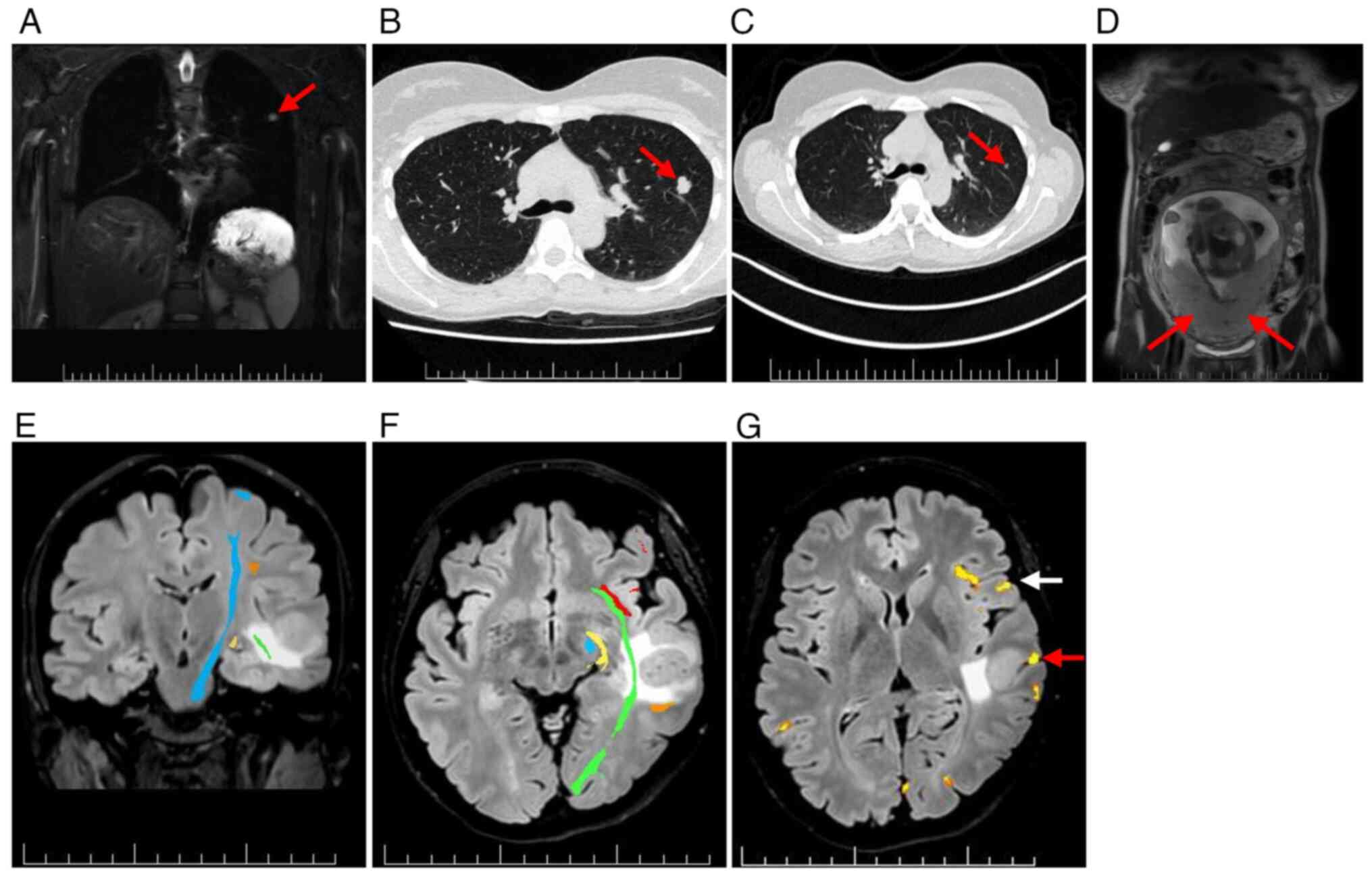

For systemic staging, whole-body (WB)-MRI with

diffusion-weighted imaging demonstrated a small solid lesion in the

left upper lung lobe (Fig. 3A).

High-resolution CT confirmed a lobulated nodule in the left S3

region (Fig. 3B). Retrospective

comparison with a CT scan from January 2023, showed interval growth

of 12 mm (Fig. 3C). No uterine or

placental involvement was detected using WB-MRI (Fig. 3D).

Neurosurgical management

After multidisciplinary counseling and obtaining

informed consent, a pro-fetus strategy was adopted. Due to

symptomatic peritumoral edema from brain MTS, the patient received

intravenous dexamethasone (4 mg every 8 h for 12 doses; total, 48

mg), followed by oral methylprednisolone (16 mg every 8 h), which

was gradually reduced and discontinued after 6 weeks.

Preoperative MRI mapping with diffusion tensor

imaging and functional MRI showed the largest left temporal MTS

abutting eloquent language and motor areas (Fig. 3E-G). In January 2024, an awake

craniotomy with resection of the left middle temporal gyrus MTS was

performed (Fig. 2Ba).

Histopathological analysis of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded

samples confirmed metastatic melanoma (Fig. S1) (21). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated the

following results: Cytokeratin AE1/3(−), S100(+), SOX10(+),

melan-A(+), HMB-45(+), preferentially expressed antigen in

melanoma(+), with a Ki-67 proliferation index up to 30% (Fig. S1) (22,23).

Molecular testing detected a BRAF V600E mutation using the CE-IVD

certified PNAClamp™ BRAF Mutation Detection Kit (HLP

Panagene Co., Ltd.), performed according to the manufacturer's

instructions. No epileptiform activity was observed on preoperative

electroencephalography or intraoperative electrocorticography.

Due to interval progression, a second craniotomy was

undertaken in January 2024, to resect the right superior frontal

gyrus MTS (Figs. 1B and 2Bb). Both procedures were uneventful. The

patient and fetus remained clinically stable without neurological

deficit, and the patient was discharged to close outpatient

surveillance in February 2024.

Initiation of targeted therapy

A follow-up MRI in February 2024 demonstrated

progression of brain MTS (Fig. 2Bc and

Bd) and the emergence of a new unresectable left hippocampal

MTS, with perifocal edema (Fig.

2Be). At 30+1 weeks' gestation, the patient was counseled

regarding three potential management strategies: i) Induction of

preterm delivery to permit systemic therapy; ii) initiation of

systemic therapy during pregnancy; or iii) a conservative

watch-and-wait approach.

A multidisciplinary board, chaired by the hospital

director and including an oncologist, neonatologist, gynecologist,

neurosurgeon, neurologist and clinical psychologist, reviewed the

case. Counseling addressed maternal neurological risks, potential

teratogenicity of targeted therapy, expected neonatal outcomes at

different gestational ages, the rationale for delaying vs.

expediting delivery and the scope of fetal surveillance. The

patient was given >24 h to reflect on the information and had

the opportunity to consult with their husband and family.

After providing informed consent, the patient

elected to continue the pregnancy and initiate systemic targeted

therapy. In February 2024, oral dabrafenib (150 mg twice daily) and

trametinib (2 mg once daily) were commenced (Fig. 1).

A subsequent MRI in March 2024 demonstrated

favorable postoperative changes (Fig.

2Ca and Cb), along with a marked reduction in brain MTS volume

compared with that in February 2024 (Fig. 2Cc-Ce).

Peripartum events

To allow for fetal maturation, delivery was planned

for ~34 weeks' gestation. Oncological therapy was interrupted 3

days beforehand, and intramuscular dexamethasone (6 mg every 12 h;

four doses) was administered for fetal lung maturation.

In March 2024 (33+6 weeks), the patient experienced

a focal impaired consciousness seizure, necessitating an urgent

cesarean section. A eutrophic premature male neonate was delivered,

weighing 2,030 g and measuring 46 cm, with Apgar scores of 9/9/9

(24). The patient resumed targeted

oncological therapy postoperatively and was started on

levetiracetam, titrated to 500 mg twice daily, for seizure

control.

Neonatal findings and follow-up

At birth, the neonate exhibited delayed cranial

ossification with widely open anterior and posterior fontanelles

and a broad sagittal suture. Cutaneous findings included fragile

vasculature with dark discoloration, most pronounced in the cubital

veins, and several isolated dark gray macules (4–5 mm in

diameter).

The neonate developed respiratory insufficiency

requiring admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and

continuous positive airway pressure support. Transient hypotension

was managed with intravenous crystalloids. Progression to

respiratory distress syndrome necessitated surfactant replacement

and 6 days of mechanical ventilation. Pulmonary hypertension was

treated with inhaled nitric oxide and vasopressors. Cranial

ultrasound revealed a grade I intraventricular hemorrhage and stage

I hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. No congenital malformations were

identified. Histological examination of the placenta and umbilical

cord showed no evidence of metastatic disease (Fig. S1). The neonate was discharged 27

days after birth.

The child has been followed up at the National

Institute of Children's Diseases (Bratislava, Slovakia).

Neurodevelopmental assessment at 11 months of chronological age

(corrected age, 9 months) included standardized testing with the

Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Fourth Edition

(Bayley-4) (25) for cognitive,

communication and motor domains, and the Bayley-III (26) for social-emotional behavior.

Cognitive function (37th percentile), communication (50th

percentile) and motor function (73rd percentile) were all within

the average range (16th-84th percentile) for corrected age, while

social-emotional behavior was in the higher-average range (75th

percentile). Repeated screening with the S-PMV test (Slovakian,

Skríning psychomotorického vývoja) was also normal. At the

latest follow-up (May 2025), growth and psychomotor development

were within normal limits.

Maternal oncological course and

follow-up

The patient's targeted therapy with D + T was

terminated after 7 weeks (April 2024) due to pyrexia and fatigue.

The patient was subsequently transitioned to combined immune

checkpoint inhibitor therapy as second-line treatment (Fig. 1). The concurrent regimen of

ipilimumab (3 mg per kg) and nivolumab (1 mg per kg) was

administered intravenously every 3 weeks for four doses, followed

by maintenance nivolumab (240 mg) every 2 weeks.

In May 2024, the patient experienced a second

epileptic seizure of the focal to bilateral tonic-clonic type, and

the levetiracetam dosage was increased to 750 mg twice daily. As of

May 2025, the patient remains on maintenance nivolumab therapy with

partial disease remission and no evidence of treatment-related

toxicity (Fig. 2Da-De).

Cognitive function remained intact, with a Montreal

Cognitive Assessment (27) score of

30 out of 30. Quality of life, assessed with the Patient-Weighted

Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory (version 2) (28), was 70.6 out of 100. Psychological

evaluation revealed moderate anxiety, with a Generalized Anxiety

Disorder-7 (29) score of 8 out of

21 and mild depressive symptoms, with a Patient Health

Questionnaire-9 (30) score of 9

out of 27, without suicidal ideation.

The patient remains under regular oncological

follow-up, receiving maintenance nivolumab every 2 weeks and under

neurological surveillance every 3 months. The partial remission

response could be durable as demonstrated in the CheckMate 204

study (12); however, long-term

vigilance is warranted.

Discussion

CM is a highly aggressive malignancy responsible for

>60,000 mortalities annually (31). Over the past decade, innovative

systemic therapies, including MAPK pathway inhibitors (BRAF and

MEK) and immune checkpoint blockers (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte

associated protein 4 and programmed cell death protein 1), have

notably improved melanoma prognosis, with 3-year overall survival

rates reaching 41.3 and 58.4%, respectively. During the first year

of treatment, the combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors has shown

superior efficacy compared with immune checkpoint blockade, with a

rapid onset of response even in brain MTS, although typically

limited to 6 months (11,32). In patients with symptomatic brain

MTS, intracranial responses to vemurafenib (a BRAF inhibitor) were

seen in only 16% of cases (33). By

contrast, D + T therapy achieved an intracranial response rate of

58% in patients with BRAF V600-mutant melanoma brain MTS, compared

with 31% in patients treated with dabrafenib monotherapy (11).

Human placental cotyledon models indicate notable

passage of D + T molecules through the placental barrier, with

higher fetal transfer for dabrafenib (14.9%) compared with

trametinib (8.6%) (34).

Preclinical animal studies have shown that BRAF inhibitors

(vemurafenib, dabrafenib and encorafenib) possess teratogenic

potential, while trametinib (a MEK inhibitor) has been associated

with possible teratogenic and embryotoxic effects (35). Dabrafenib demonstrated teratogenic

and embryotoxic properties at doses three times higher compared

with standard human exposure (36,37). D

+ T may disrupt fetal growth and development by inhibiting the

RAS/MAPK signaling pathway, potentially causing congenital defects

(including cardiomyopathies, and facial and skeletal anomalies),

developmental delay, intellectual disability and tumor

predisposition (35,38). Furthermore, the MAPK/ERK pathway

serves a crucial role in trophoblast proliferation, making BRAF/MEK

inhibitor use particularly concerning during early pregnancy

(5,39).

As of May 2025, to the best of our knowledge, no

reports have documented the combined use of BRAF and MEK inhibitors

during pregnancy. Available data and well-controlled studies on the

safety of D + T in pregnant women remain limited, precluding

definitive conclusions (35).

Current European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and American

Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines advise against combined

BRAF/MEK inhibition during pregnancy due to teratogenic and

embryotoxic risks. As alternatives, interferon-α or BRAF inhibitor

monotherapy may be considered as temporizing measures if urgent

systemic treatment cannot be delayed (40–43).

In the present case of advanced metastatic melanoma

during pregnancy, two surgical resections of the largest

symptomatic brain MTS were prioritized. However, due to further

inoperable progression and the patient's refusal of preterm

delivery, systemic therapy with D + T was initiated, based on its

superior efficacy over vemurafenib or dabrafenib monotherapy

(11,33,44).

The immediacy of life-threatening brain MTS justified short-term

dual BRAF/MEK inhibition despite guideline cautions, supported by

multidisciplinary consensus, comprehensive maternal counseling and

close materno-fetal monitoring. Therapy was initiated only after

the period of fetal organogenesis had been completed. Histological

examination of the placenta and umbilical cord, in line with ESMO

guidance, revealed no metastatic involvement.

There are isolated reports of BRAF inhibitor use in

pregnancy-associated stage IV melanoma (Table I). In all 4 cases (including one set

of twins), vemurafenib was administered (14–17),

with low-level transplacental transfer (37). Administration occurred between 17

and 25 weeks' gestation, and all 5 infants were born prematurely

(26–36 weeks). A total of 3 had a low birth weight (1,028, 950 and

900 g), 1 weighed 2,510 g and 1 had an unspecified weight, with 3

of the newborns requiring NICU admission. With regard to the

mothers, 1 patient with a solitary brain metastasis in the temporal

lobe died from an intracranial hemorrhage 78 days after treatment

initiation (16). Another was

diagnosed with cerebral and dural MTS postpartum and died 3.5

months after initiating vemurafenib therapy (15). The present case therefore contrasts

with previous vemurafenib-only reports, being the first to describe

combined BRAF/MEK inhibition in pregnancy. Notably, the patient

remains alive in partial remission at >14 months (452 days)

after the initiation of D + T.

| Table I.Case reports of targeted therapy in

pregnancy-associated stage IV melanoma. |

Table I.

Case reports of targeted therapy in

pregnancy-associated stage IV melanoma.

| First author,

year | Drug | Patient age,

years | Weeks gestation at

initiation of treatment | Weeks gestation at

delivery | Neonate birth

weight, g | NICU admission of

neonate | Metastatic

involvement in patient | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Pagan et al,

2019 | Vemurafenib | 25 | 25 | 34 | 2,510 | Yes | Lungs, subcutaneous

and lymph node | (14) |

| Maleka et

al, 2013 | Vemurafenib | 37 | 25 | 30 | 1,028 | No | Subcutaneous,

liver, lungs, brain and meninges | (15) |

| de Haan et

al, 2018 | Vemurafenib | 30 | 22 | 26 | 950 and 900 | Yes (both) | Cutaneous, bowel,

mesentery, breast and brain | (16) |

| Marcé et al,

2019 | Vemurafenib | 29 | 17 | 36 | Not mentioned | No | Liver, lymph node,

subcutaneous and bone | (17) |

| Present case | Dabrafenib +

trametinib | 35 | 30 | 33 | 2,030 | Yes | Brain |

|

Checkpoint inhibitors introduced postpartum in the

present case provided additional long-term disease control.

Previous research highlights the heterogeneity of the melanoma

immune microenvironment and identifies a prognostic NOD-like

receptor gene signature strongly associated with survival in skin

CM (45). Such insights into

tumor-immune interactions may help explain the durable partial

remission observed in the present patient under nivolumab

maintenance.

The neonate in the present case exhibited delayed

cranial ossification, fragile vasculature and respiratory

complications requiring admission to the NICU. These findings are

most likely multifactorial, reflecting prematurity and possible

in utero exposure to targeted therapy. While inhibition of

the MAPK pathway provides a plausible mechanistic link to abnormal

ossification, causality cannot be established. A limitation is that

therapeutic drug monitoring of D + T plasma levels was not

available at the Academician Ladislav Dérer Hospital (University

Hospital Bratislava, Bratislava, Slovakia) and therefore was not

performed.

The present case provides rare insight into the

management of PAM with brain MTS, illustrating that, in selected

situations with immediate maternal risk, combined BRAF/MEK

inhibition may be justified following multidisciplinary evaluation,

despite current guideline cautions. The present report emphasizes

the importance of individualized decision-making, careful

materno-fetal monitoring and long-term follow-up of both mother and

child.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Associate Professor

Andrej Steno, Head of the Department of Neurosurgery, Faculty of

Medicine, Comenius University (Bratislava, Slovakia), for

performing both neurosurgical procedures and for expert guidance.

The authors also thank Dr Robert Godal, oncologist at the 2nd

Department of Oncology, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University

(Bratislava, Slovakia), for providing valuable input regarding

oncological management and follow-up care.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JM, MJ, SM, KKG, MKa and GT collected and analyzed

clinical data. JM drafted the manuscript. PV and GT contributed to

the study conception and supervised the project. IS and MKr

participated in data interpretation and provided critical revisions

of the manuscript. MJ, SM, KKG, MKa, IS, MKr, PV and GT reviewed

and edited the manuscript. JM and GT confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present case study was performed in accordance

with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were

not required for this type of study on human participants,

according to local legislation and institutional requirements. The

patient provided written informed consent to participate in all the

diagnostic, neurosurgical and oncological treatment procedures

described in the present report.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of clinical data, accompanying images

and any potentially identifiable information included in the

present article. The patient was informed that the published

material would be available in print and online, and consented to

publication under these terms.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

BRAF

|

B-Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine

kinase

|

|

CM

|

cutaneous melanoma

|

|

D + T

|

dabrafenib and trametinib

|

|

MAPK

|

mitogen-activated protein kinase

|

|

MEK

|

mitogen-activated protein kinase

kinase

|

|

MTS

|

metastases

|

|

NICU

|

neonatal intensive care unit

|

|

PAM

|

pregnancy-associated melanoma

|

|

WB

|

whole-body

|

References

|

1

|

Leonardi GC, Falzone L, Salemi R, Zanghì

A, Spandidos DA, Mccubrey JA, Candido S and Libra M: Cutaneous

melanoma: From pathogenesis to therapy (Review). Int J Oncol.

52:1071–1080. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chang AE, Karnell LH and Menck HR: The

national cancer data base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous

melanoma: A summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. The

American college of surgeons commission on cancer and the American

cancer society. Cancer. 83:1664–1678. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Shenenberger DW: Cutaneous malignant

melanoma: A primary care perspective. Am Fam Physician. 85:161–168.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sampson JH, Carter JH Jr, Friedman AH and

Seigler HF: Demographics, prognosis, and therapy in 702 patients

with brain metastases from malignant melanoma. J Neurosurg.

88:11–20. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ziogas DC, Diamantopoulos P, Benopoulou O,

Anastasopoulou A, Bafaloukos D, Stratigos AJ, Kirkwood JM and Gogas

H: Prognosis and management of BRAF V600E-mutated

pregnancy-associated melanoma. Oncologist. 25:e1209–e1220. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Serrano-Ortega S and Buendía-Eisman A:

Melanoma and pregnancy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 102:647–649. 2011.(In

Spanish). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

O'Meara AT, Cress R, Xing G, Danielsen B

and Smith LH: Malignant melanoma in pregnancy: A population-based

evaluation. Cancer. 103:1217–1226. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Dillman RO, Vandermolen LA, Barth NM and

Bransford KJ: Malignant melanoma and pregnancy ten questions. West

J Med. 164:156–161. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hepner A, Negrini D, Hase EA, Exman P,

Testa L, Trinconi AF, Filassi JR, Francisco RPV, Zugaib M, O'Connor

TL and Martin MG: Cancer during pregnancy: The oncologist overview.

World J Oncol. 10:28–34. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Alexander A, Samlowski WE, Grossman D,

Bruggers CS, Harris RM, Zone JJ, Noyes RD, Bowen GM and Leachman

SA: Metastatic melanoma in pregnancy: Risk of transplacental

metastases in the infant. J Clin Oncol. 21:2179–2186. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Davies MA, Saiag P, Robert C, Grob JJ,

Flaherty KT, Arance A, Chiarion-Sileni V, Thomas L, Lesimple T,

Mortier L, et al: Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with

BRAFV600-mutant melanoma brain metastases (COMBI-MB): A

multicentre, multicohort, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol.

18:863–873. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tawbi HA, Forsyth PA, Hodi FS, Algazi AP,

Hamid O, Lao CD, Moschos SJ, Atkins MB, Lewis K, Postow MA, et al:

Long-term outcomes of patients with active melanoma brain

metastases treated with combination nivolumab plus ipilimumab

(CheckMate 204): Final results of an open-label, multicentre, phase

2 study. Lancet Oncol. 22:1692–1704. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ascierto PA, Mandalà M, Ferrucci PF,

Guidoboni M, Rutkowski P, Ferraresi V, Arance A, Guida M, Maiello

E, Gogas H, et al: Sequencing of ipilimumab plus nivolumab and

encorafenib plus binimetinib for untreated BRAF-mutated metastatic

melanoma (SECOMBIT): A randomized, three-arm, open-label phase II

trial. J Clin Oncol. 41:212–221. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Pagan M, Jinks H and Sewell M: Treatment

of metastatic malignant melanoma during pregnancy with a BRAF

kinase inhibitor. Case Rep Womens Health. 24:e001422019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Maleka A, Enblad G, Sjörs G, Lindqvist A

and Ullenhag GJ: Treatment of metastatic malignant melanoma with

vemurafenib during pregnancy. J Clin Oncol. 31:e192–e193. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

de Haan J, van Thienen JV, Casaer M,

Hannivoort RA, Van Calsteren K, van Tuyl M, van Gerwen MM, Debeer

A, Amant F and Painter RC: Severe adverse reaction to vemurafenib

in a pregnant woman with metastatic melanoma. Case Rep Oncol.

11:119–124. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Marcé D, Cornillier H, Denis C,

Jonville-Bera AP and Machet L: Partial response of metastatic

melanoma to BRAF-inhibitor-monotherapy in a pregnant patient with

no fetal toxicity. Melanoma Res. 29:446–447. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Clark WH Jr, From L, Bernardino EA and

Mihm MC: The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human

malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 29:705–727.

1969.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Breslow A: Thickness, cross-sectional

areas and depth of invasion in the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma.

Ann Surg. 172:902–908. 1970. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Keung EZ and Gershenwald JE: The eighth

edition American joint committee on cancer (AJCC) melanoma staging

system: Implications for melanoma treatment and care. Expert Rev

Anticancer Ther. 18:775–784. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Suvarna KS, Layton C and Bancroft JD:

Bancroft's Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. 8th

edition. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2018

|

|

22

|

Ramos-Vara JA: Technical aspects of

immunohistochemistry. Vet Pathol. 42:405–426. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ and

Binder SW: Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan

Pathol. 35:433–444. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Apgar V: A proposal for a new method of

evaluation of the newborn infant. Curr Res Anesth Analg.

32:260–267. 1953. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Bayley N and Aylward GP: Bayley Scales of

Infant and Toddler Development. 4th edition. Pearson Education,

Inc.; San Antonio, TX: 2019

|

|

26

|

Bayley N: Bayley scales of Infant and

Toddler Development. 3rd edition. Harcourt Assessment; San Antonio,

TX: 2006

|

|

27

|

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V,

Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL and Chertkow H:

The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for

mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 53:695–699. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Cramer JA and Van Hammée G; N132 Study

Group, : Maintenance of improvement in health-related quality of

life during long-term treatment with levetiracetam. Epilepsy Behav.

4:118–123. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW and

Löwe B: A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder:

The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 166:1092–1097. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL and Williams JBW:

The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen

Intern Med. 16:606–613. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Global Burden of Disease Cancer

Collaboration, . Fitzmaurice C, Abate D, Abbasi N, Abbastabar H,

Abd-Allah F, Abdel-Rahman O, Abdelalim A, Abdoli A, Abdollahpour I,

et al: Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality,

years of life lost, years lived with disability, and

disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990 to 2017:

A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA

Oncol. 5:1749–1768. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ugurel S, Röhmel J, Ascierto PA, Becker

JC, Flaherty KT, Grob JJ, Hauschild A, Larkin J, Livingstone E,

Long GV, et al: Survival of patients with advanced metastatic

melanoma: The impact of MAP kinase pathway inhibition and immune

checkpoint inhibition-update 2019. Eur J Cancer. 130:126–138. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Dummer R, Goldinger SM, Turtschi CP,

Eggmann NB, Michielin O, Mitchell L, Veronese L, Hilfiker PR,

Felderer L and Rinderknecht JD: Vemurafenib in patients with

BRAF(V600) mutation-positive melanoma with symptomatic brain

metastases: Final results of an open-label pilot study. Eur J

Cancer. 50:611–621. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Heggarty E, Combarel D, Vialard F,

Rodriguez Y, Grassin-Delyle S, Lamy E, Mir O, Paci A and Berveiller

P: 36 Evaluation of transplacental transfer of cancer therapies in

melanoma via the perfused human placental model. Am J Obstet

Gynecol. 230 (Suppl 1):S28–S29. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Hassel JC, Livingstone E, Allam JP, Behre

HM, Bojunga J, Klein HH, Landsberg J, Nawroth F, Schüring A, Susok

L, et al: Fertility preservation and management of pregnancy in

melanoma patients requiring systemic therapy. ESMO Open.

6:1002482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Pelczar P, Kosteczko P, Wieczorek E,

Kwieciński M, Kozłowska A and Gil-Kulik P: Melanoma in

pregnancy-diagnosis, treatment, and consequences for fetal

development and the maintenance of pregnancy. Cancers (Basel).

16:21732024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lorenzi E, Simonelli M, Persico P,

Dipasquale A and Santoro A: Risks of molecular targeted therapies

to fertility and safety during pregnancy: A review of current

knowledge and future needs. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 20:503–521. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Tajan M, Paccoud R, Branka S, Edouard T

and Yart A: The RASopathy family: Consequences of germline

activation of the RAS/MAPK pathway. Endocr Rev. 39:676–700. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Grunewald S and Jank A: New systemic

agents in dermatology with respect to fertility, pregnancy, and

lactation. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 13:277–290. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Peccatori FA, Azim HA Jr, Orecchia R,

Hoekstra HJ, Pavlidis N, Kesic V and Pentheroudakis G; ESMO

Guidelines Working Group, : Cancer, pregnancy and fertility: ESMO

clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and

follow-up. Ann Oncol. 24 (Suppl 6):vi160–vi170. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Amaral T, Ottaviano M, Arance A, Blank C,

Chiarion-Sileni V, Donia M, Dummer R, Garbe C, Gershenwald JE,

Gogas H, et al: Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO clinical practice

guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol.

36:10–30. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Silverstein J, Post AL, Chien AJ, Olin R,

Tsai KK, Ngo Z and Loon KV: Multidisciplinary management of cancer

during pregnancy. JCO Oncol Pract. 16:545–557. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Sorouri K, Loren AW, Amant F and Partridge

AH: Patient-centered care in the management of cancer during

pregnancy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 43:e1000372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Garzón-Orjuela N, Prieto-Pinto L, Lasalvia

P, Herrera D, Castrillón J, González-Bravo D, Castañeda-Cardona C

and Rosselli D: Efficacy and safety of dabrafenib-trametinib in the

treatment of unresectable advanced/metastatic melanoma with

BRAF-V600 mutation: A systematic review and network meta-analysis.

Dermatol Ther. 33:e131452020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Geng Y, Sun YJ, Song H, Miao QJ, Wang YF,

Qi JL, Xu XL and Sun JF: Construction and identification of an

NLR-associated prognostic signature revealing the heterogeneous

immune response in skin cutaneous melanoma. Clin Cosmet Investig

Dermatol. 16:1623–1639. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|