Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a

hematological malignancy characterized by malignant transformation

and proliferation of lymphoid progenitor cells in bone marrow. The

prognosis of relapsed or refractory ALL (RR-ALL) remains poor, with

a reported median overall survival (OS) of 6 months and a 5-year

survival rate of 7% (1,2). Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

(HSCT) is the only treatment option for achieving long-term

survival in RR-ALL. Although achieving complete remission (CR)

before the initiation of HSCT is preferable, conventional salvage

chemotherapy regimens are associated with CR rates of only 30–40%

(3).

Inotuzumab ozogamicin (IO), a novel therapeutic drug

for RR-ALL, is a humanized anti-cluster of differentiation (CD) 22

monoclonal antibody conjugated with calicheamicin. IO was approved

in August 2017 in the United States for the treatment of

CD22+ RR-ALL. The pivotal INO-VATE study compared

clinical efficacy of IO with that of conventional chemotherapies

used as the control; it revealed that CR and CR with incomplete

hematologic recovery were markedly higher in the IO group (80.7%)

compared with those in the control group (29.4%). On the other

hand, the duration of remission and median OS in the IO group were

only 4.6 months and 7.7 months, respectively, which is only 1.5

months longer than in the control group (4). The final report from the INO-VATE

study revealed 2-year OS rates of 22.8 and 10.8% in the IO group

and in the control group, respectively (5,6). Thus,

while IO is far more effective for treating RR-ALL than

conventional regimens, the duration of remission remains short. As

a result, effective combination strategies are needed to enhance

the anti-leukemic effects of IO.

IO comprises the cytotoxic antibiotic

N-acetyl-gamma-calicheamicin dimethylhydrazine, a calicheamicin

derivative, attached to a humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody via

the 4-(4 acetylphenoxy) butanoic acid (acetyl butyrate) linker.

Once IO is administered to patients, the drug binds to the CD22

leukemic cell surface antigen. The complex is then internalized and

fuses with lysosomes inside the cell. Calicheamicin detaches from

the antibody site following the breakdown of the linker, inducing

DNA single-strand breaks (SSBs) and double-strand breaks (DSBs) in

the nucleus and subsequent apoptosis (7).

PARPs are a family of 17 proteins involved in the

repair of DNA strand breaks. The most well-studied members of the

PARP family are PARP-1 and PARP-2, which play crucial roles in the

repair of SSBs. PARP inhibitors are novel anticancer drugs

targeting the DNA damage response (8). Olaparib, a potent inhibitor of

PARP-1/2, was first approved for the treatment of breast cancer

susceptibility gene (BRCA)-mutant ovarian cancer in 2014.

Since then, several other PARP inhibitors have been developed and

approved, and their use has been expanded to the treatment of

various types of cancer (9,10). Talazoparib is the latest approved

PARP-1/2 inhibitor with the most potent PARP1 inhibitory activity

for the treatment of BRCA-mutant breast cancer. Loss of

BRCA function causes failure of the DSB repair pathway. In

BRCA-defective tumor cells, PARP inhibitors prevent the

repair of SSBs, which then convert to irreparable and toxic DSBs,

effectively exerting cytotoxicity through synthetic lethality

(11).

One strategy to increase the cytotoxicity of IO is

inhibition of DSB repair. Leukemic cells evoke a DSB repair

response following DNA damage triggered by IO. Inhibition of the

repair response is hypothesized to accumulate unrepaired DNA strand

breaks, thereby enhancing the cytotoxicity of IO. The present study

aimed to compare synergistic anti-leukemic effects between IO and

PARP inhibitors in B-ALL cells. For this purpose, the cytotoxicity

of IO was first evaluated in detail using Philadelphia

(Ph)− and Ph+ B-ALL cell lines in

vitro. Next, the alkaline comet assay was used to determine DNA

damage repair kinetics in cells treated with IO. Finally, attempts

were made to increase the cytotoxic effects of IO by adding either

olaparib or talazoparib, which are PARP inhibitors, under a

hypothesized interaction between these drugs.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures

The Reh Ph−B-ALL cell line (cat. no.

CRL-8286), the SUP-B15 Ph+ B-ALL cell line (cat. no.

CRL-1929) and the HL-60 acute promyelocytic leukemia cell line

(cat. no. CLL-240) were purchased from American Type Culture

Collection (ATCC). Reh and HL-60 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640

medium (ATCC) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), at 37°C under 5% CO2 in a

humidified atmosphere. SUP-B15 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's

medium (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) with 20% FBS in

the same atmosphere. Reverse transcription PCR testing was used to

ensure the absence of mycoplasma contamination (Biotherapy

Institute of Japan, Inc.). Reh and SUP-B15 cells were confirmed to

be free of mycoplasma.

Chemicals and reagents

IO was kindly provided by Pfizer, Inc. and dissolved

in water for injection (FUSO Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd.) to a

stock concentration of 250 µg/ml. Olaparib and talazoparib were

obtained from Selleck Chemicals and dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide

(Wako Yakuhin Co., Ltd.) to a stock concentration of 10 mM.

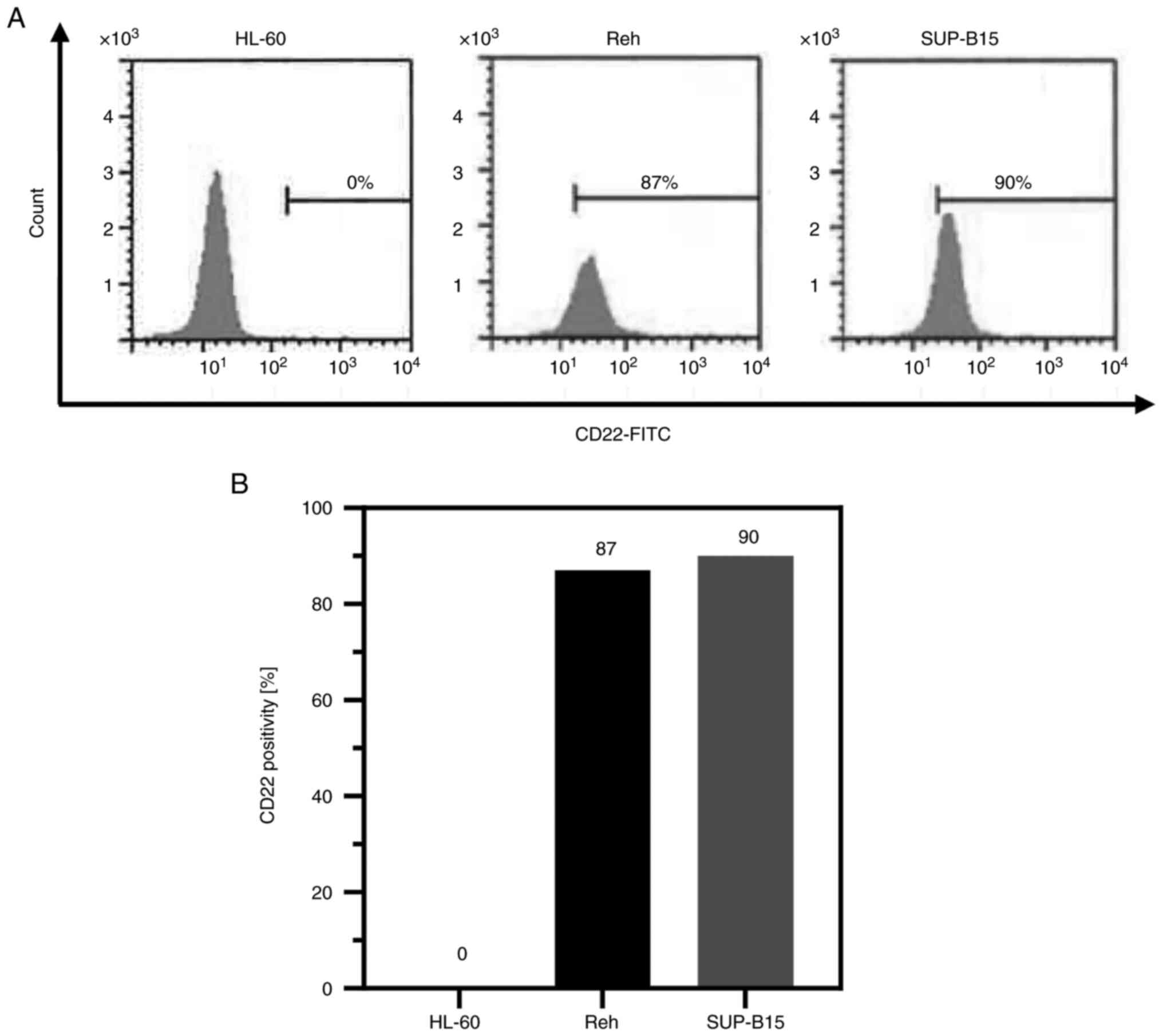

Determination of CD22 positivity

Flow cytometry was performed to determine CD22

expression on the cell surface of Reh and SUP-B15 cells using

antibodies against CD22. The analysis of CD22 expression was

performed by LSI Medience Corporation. CD22 expression was measured

using a flow cytometer (FACSCanto II; Becton, Dickinson and

Company) using undiluted IOTest CD22-Fluorescein isothiocyanate

(FITC; cat. no. IM0779U; Beckman Coulter, Inc.) and undiluted IgG2a

mouse-FITC (cat. no. A12689; Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Twice-diluted

IgG1 mouse-RD1 (cat. no. 6602884; Beckman Coulter, Inc.) was used

as a control. The acute promyelocytic leukemia cell line HL-60 was

used as a CD22− control.

Cell proliferation inhibition

assay

Cells (2.0×105/ml Reh cells and

5.0×105/ml SUP-B15 cells) were continuously exposed to

various concentrations of IO (1×10−3−1×102

ng/ml), olaparib (1×10−3−1×102 µM) and

talazoparib (1×10−1−1×104 nM) to evaluate

proliferation inhibition effects for 48 h. Cell viability was

assessed using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (cat. no. CK04;

Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.) in accordance with the manufacturer's

instructions. A total of 10 µl of the CCK-8 reagent was added to

100 µl of cell suspension and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Absorbance

was measured at 450 nm using a plate reader (SPECTRA MAX iD3;

Molecular Devices, LLC).

Annexin-V binding assay

To detect the induction of apoptosis in Reh and

SUP-B15 cells, a total of 2.0×105/ml cells were treated

with various concentrations of IO, olaparib and talazoparib for 24

or 48 h. After drug administration, cells were stained with

annexin-V and propidium iodide using Annexin V FLUOS Staining Kit

(cat. no. 49734400; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and analyzed by flow

cytometry (FACSDiva Software version 6.1.3; Becton, Dickinson and

Company) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Untreated

cells were used as negative controls and cells treated with drug

concentrations sufficient to induce apoptosis were used as positive

controls.

Calculation of combination index

(CI)

The effects of combining IO and PARP inhibitors were

calculated using the CI method (12), with values determined using CompuSyn

(version 2.11; Informert Technologies, Inc.). CI values were

classified as follows: i) CI >1.1, antagonism; ii) CI, 0.9–1.1,

additive; iii) CI, 0.85–0.9, slight synergism; iv) CI, 0.7–0.85,

moderate synergism; v) CI, 0.3–0.7, synergism; vi) CI, 0.1–0.3,

strong synergism; and vii) CI <0.1, very strong synergism

(13).

Alkaline comet assay

Alkaline comet assay was conducted to quantify the

amount of DNA strand breaks using an OxiSelect Comet Assay Kit

(cat. no. STA-351; Cell Biolabs, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. A total of 1×105 Reh

cells/ml were incubated with 2 ng/ml of IO in the presence or

absence of 1 µM olaparib or 100 nM talazoparib for 1 or 6 h at

37°C. A total of 1×105 SUP-B15 cells/ml were incubated

with 20 ng/ml IO in the presence or absence of 10 µM olaparib or 1

nM talazoparib under the same conditions used for Reh cells.

Resuspended cells were then mixed with melted 90% agarose gel and

transferred onto the base layer. These embedded cells were treated

with lysis buffer (included in OxiSelect Comet Assay Kit) and

alkaline solution. After electrophoresis, samples were washed and

fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol at room temperature for 5 min. Slides

were dried, stained with Vista Green DNA dye (OxiSelect Comet Assay

Kit), and visualized using an epifluorescence microscope (BX50F;

Olympus corporation). The Olive tail moment was calculated using

Comet (version 4.0; Oxford Instruments plc). For each sample, 50

cells were selected and analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis and graph creation were conducted

using GraphPad Prism (version 10.0.3; Dotmatics). The results are

shown as the mean ± standard division, and two-way ANOVA with

Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons on the interaction

between IO and PARP inhibitors. All of the results were derived

from at least triplicate independent experiments. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Cell surface CD22 expression

Cell surface CD22 expression, which is indispensable

to the internalization of IO in B-ALL cells, was determined by flow

cytometry (14). The expression

levels of CD22 in Reh and SUP-B15 cells were 87 and 90%,

respectively (Fig. 1). These two

cell lines expressed sufficient levels of CD22 for IO to show

cytotoxicity (7). CD22 was not

expressed in the negative control HL-60 cells.

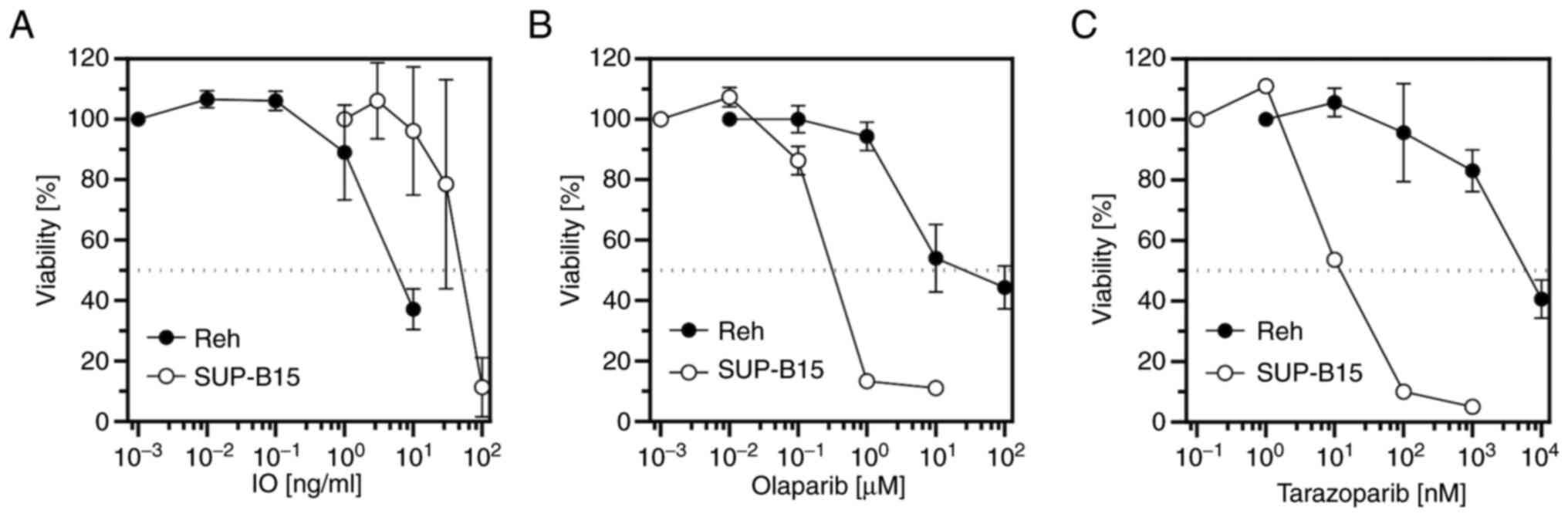

Cell proliferation inhibition and

induction of apoptosis by IO or PARP inhibitors

The anti-proliferative activity of IO in Reh and

SUP-B15 cells was examined. Cells were incubated with increasing

concentrations of IO for 48 h, then cell viability was measured by

water soluble tetrazolium assay using CCK-8. IO inhibited the

proliferation of these cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). The half-maximal inhibitory

concentration (IC50) values for IO are shown in Table I. Similarly, cell proliferation

inhibition by the PARP inhibitors olaparib and talazoparib in Reh

and SUP-B15 cells was examined. Olaparib and talazoparib inhibited

cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner in both cell lines

(Fig. 2B and C). The

IC50 values of olaparib and talazoparib are shown in

Table II, revealing that

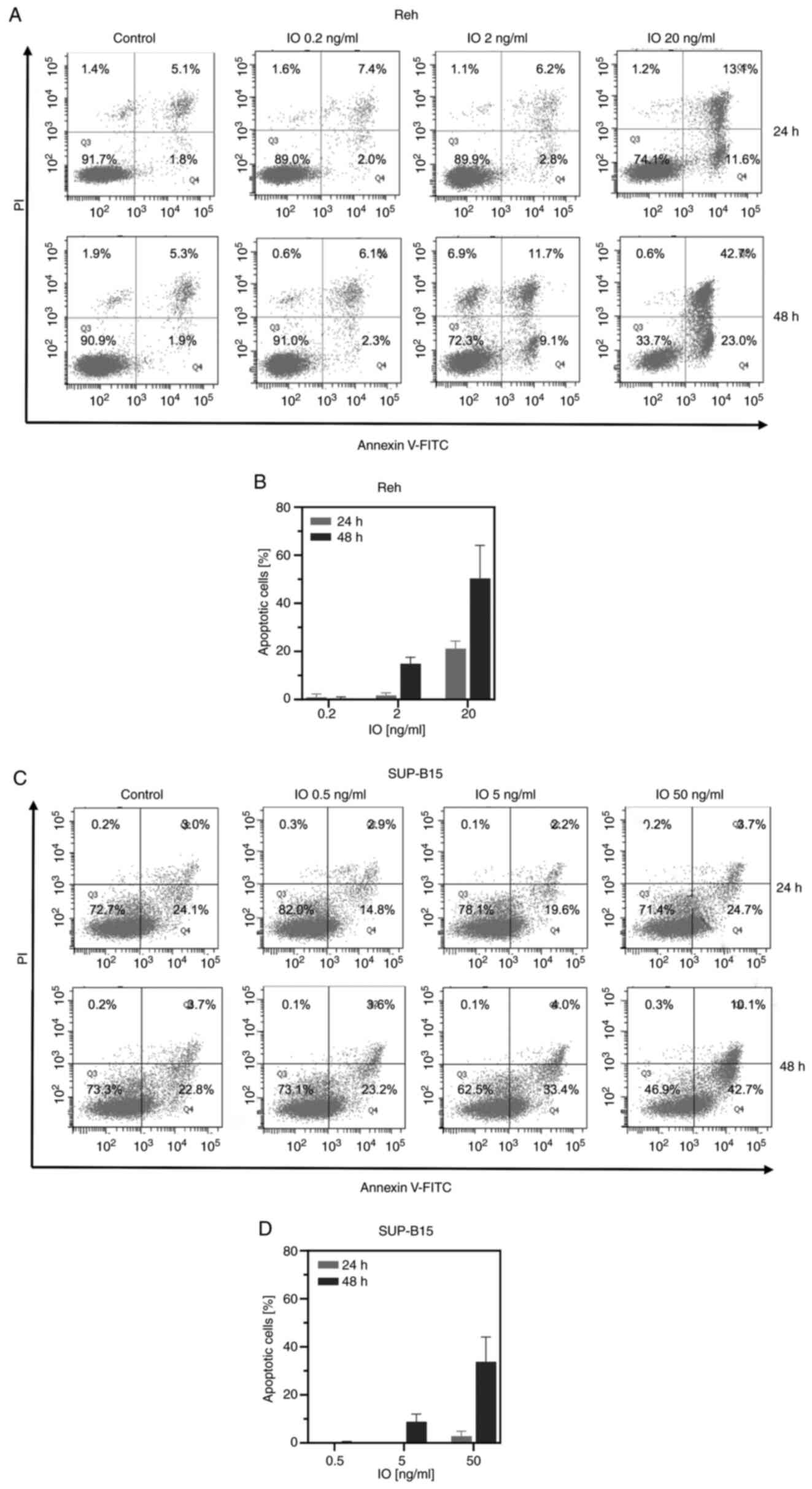

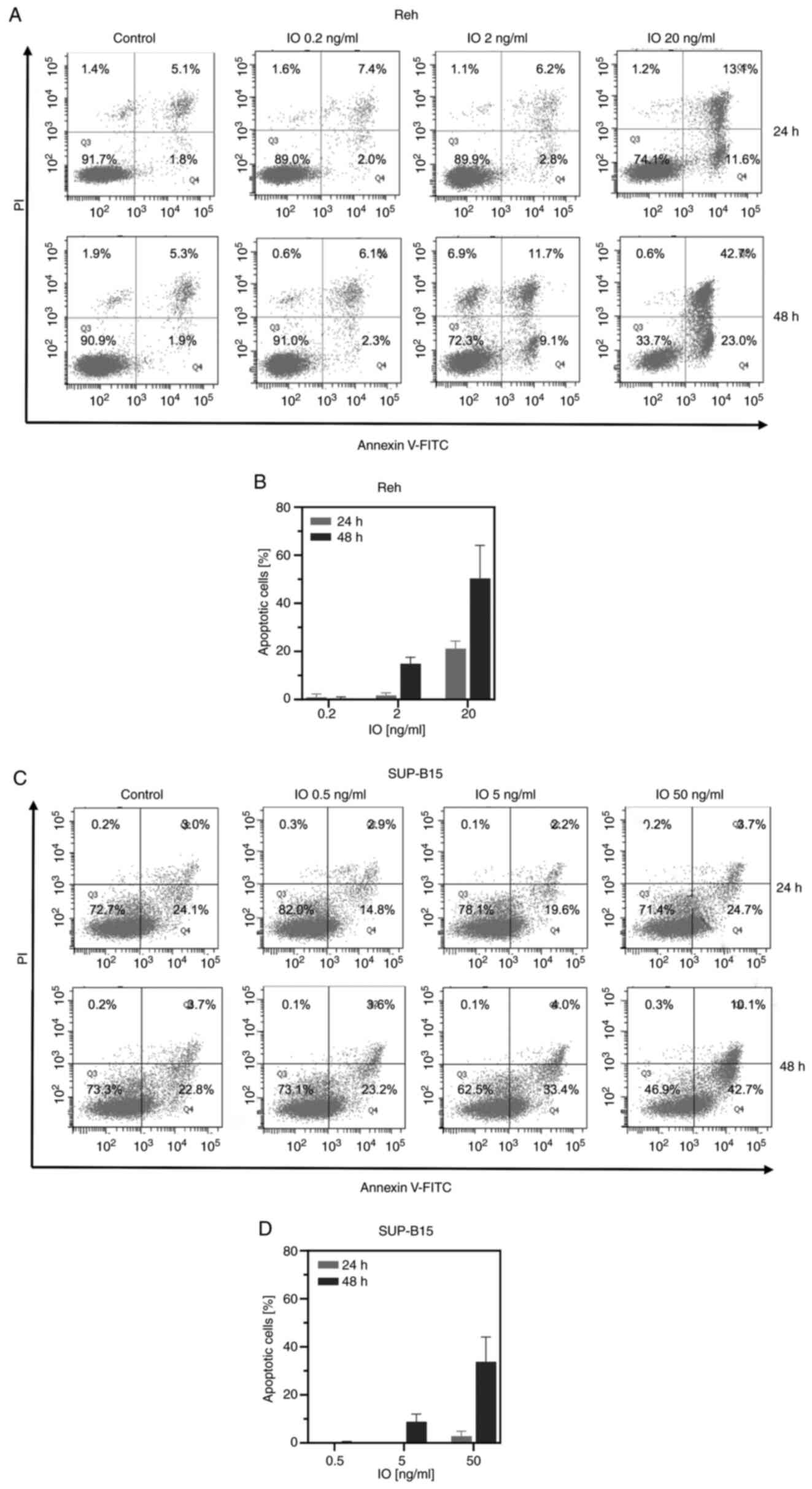

talazoparib was more potent than olaparib. An Annexin-V binding

assay was conducted to determine IO-induced apoptosis. When Reh and

SUP-B15 cells were treated with various concentrations of IO for 24

or 48 h, IO increased early and late cell apoptosis in a

dose-dependent manner. Moreover, exposure to IO induced more

apoptosis at 48 h than at 24 h for every IO concentration tested

(Fig. 3). In Fig. 3C, untreated SUP-B15 cells underwent

>20% apoptosis. SUP-B15 cells are prone to elimination by

apoptosis very easily and spontaneously. Previous studies using

SUP-B15 cell line also revealed some extent of cell death of

untreated SUP-B15 cells (15,16).

The live cell percentage of untreated SUP-B15 was ~83–88% in these

studies. These present results indicated that IO was cytotoxic to

both Ph− and Ph+ B-ALL cells, and talazoparib

was more cytotoxic to both Ph− and Ph+ B-ALL

cells than olaparib.

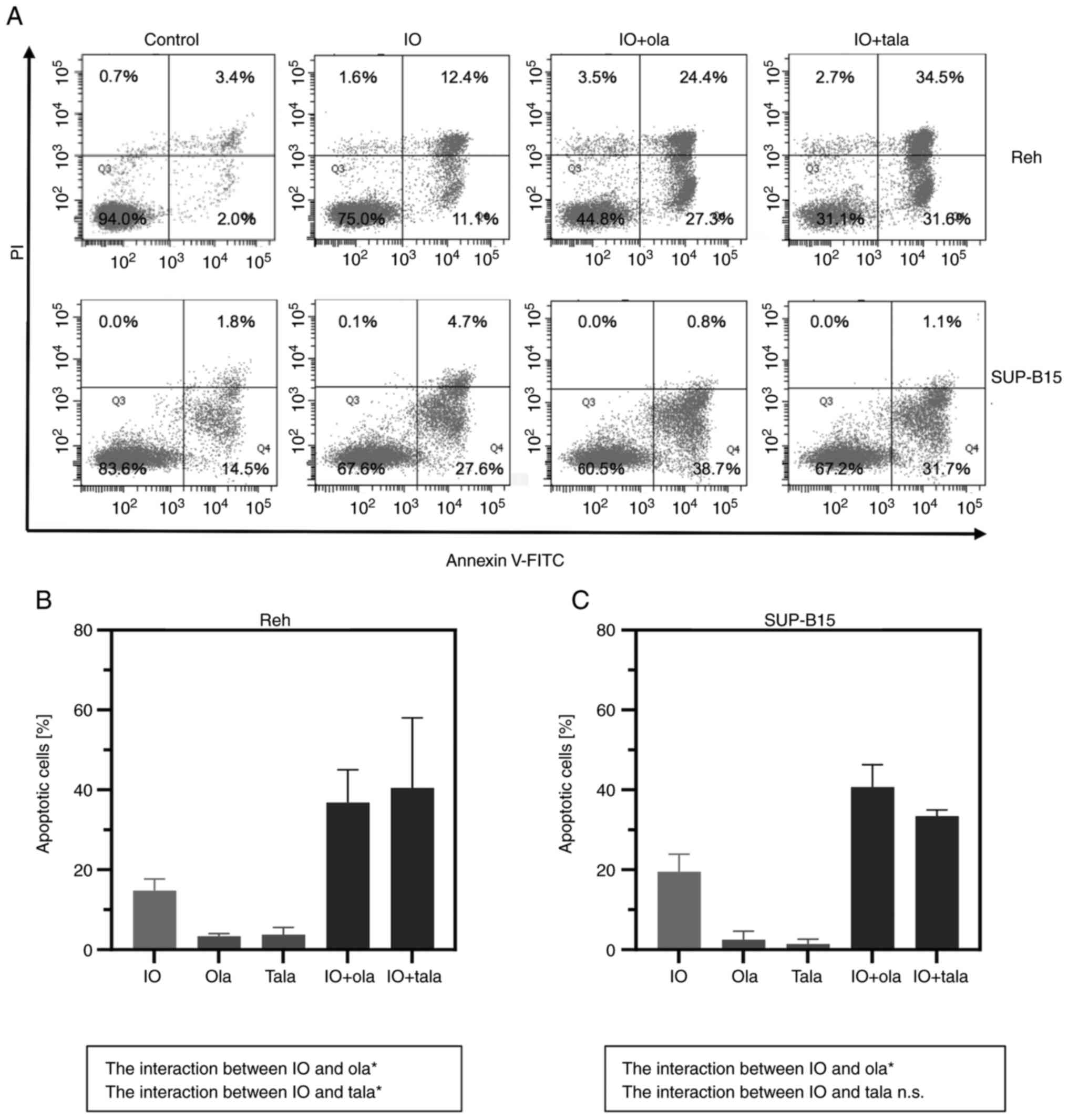

| Figure 3.Induction of apoptosis by IO. Cells

were incubated with (A and B) 0.2, 2, or 20 ng/ml IO for Reh cells;

(C and D) 0.5, 5, or 50 ng/ml IO for SUP-B15 cells for 24 or 48 h,

followed by (A and C) Annexin-V and propidium iodide co-staining

and flow cytometry. The left lower quadrant shows live cells, and

the left upper quadrant shows necrotic cells. The right lower and

upper quadrants, as annexin-V+ quadrants, show early and late

apoptotic cells, respectively. The percentage of cells in every

quadrant is indicated. (B and D) Histograms represent the

percentage of apoptotic cells (drug-treated apoptotic cells minus

control apoptotic cells). Error bars represent standard deviation

from triplicate experiments. IO, inotuzumab ozogamicin. |

| Table I.IC50 values for IO, Ola

and Tala. |

Table I.

IC50 values for IO, Ola

and Tala.

|

| Drugs |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

|

| IO | Ola | Tala |

|---|

|

IC50 |

|

|

|

|

Reh | 5.3 ng/ml | 24.0 µM | 4.9 µM |

|

SUP-B15 | 49.7 ng/ml | 0.3 µM | 0.01 µM |

| Table II.IO sensitivity in combination with

Ola or Tala. |

Table II.

IO sensitivity in combination with

Ola or Tala.

|

| Drugs |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

|

| IO + Ola | IO + Tala |

|---|

|

IC50 |

|

|

|

Reh | 0.8 ng/ml | 2.9 ng/ml |

|

SUP-B15 | 36.1 ng/ml | 39.6 ng/ml |

Cell proliferation-inhibiting effects

of combining IO with PARP inhibitors

Both Reh and SUP-B15 cells were incubated with IO

for 48 h with minimally toxic concentrations of either olaparib (1

µM in Reh cells; 10 nM in SUP-B15 cells) or talazoparib (100 nM in

Reh cells; 1 nM in SUP-B15 cells) to investigate the cell

proliferation inhibition effects of IO combined with olaparib or

talazoparib. Combined with olaparib or talazoparib, IC50

values of IO were apparently decreased (Table II). These cells became more

sensitive to IO administered in combination with PARP

inhibitors.

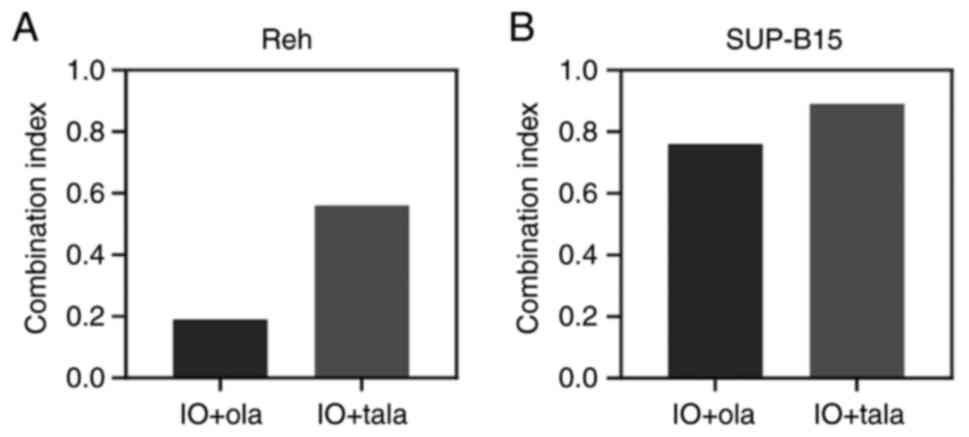

Determination of synergism between IO

and PARP inhibitors

To further investigate the combination effects

between IO and olaparib or talazoparib, the CI was calculated. Reh

and SUP-B15 cells were incubated with various concentrations of IO

in the presence of minimally toxic concentrations of olaparib or

talazoparib. When combined with olaparib or talazoparib, the CI

values were 0.19 and 0.56 for Reh cells, and 0.76 and 0.89 for

SUP-B15 cells, respectively (Fig.

4). These results revealed the synergism between IO and both

olaparib and talazoparib for Reh and SUP-B15 cells.

Induction of cell apoptosis by IO

combined with PARP inhibitors

Apoptosis was measured after cells were treated with

IO (0.2 ng/ml in Reh cells; 3.0 ng/ml in SUP-B15 cells) in the

presence or absence of minimally toxic concentrations of either

olaparib or talazoparib. Combining IO with olaparib or talazoparib

induced higher apoptosis than IO alone (Fig. 5). In both Reh and SUP-B15 cells, the

interaction between IO and olaparib was significant. In Reh cells,

the interaction between IO and talazoparib was also significant

(P<0.05; two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparisons

test). The data indicated that combining IO with PARP inhibitors

augmented IO-induced apoptosis.

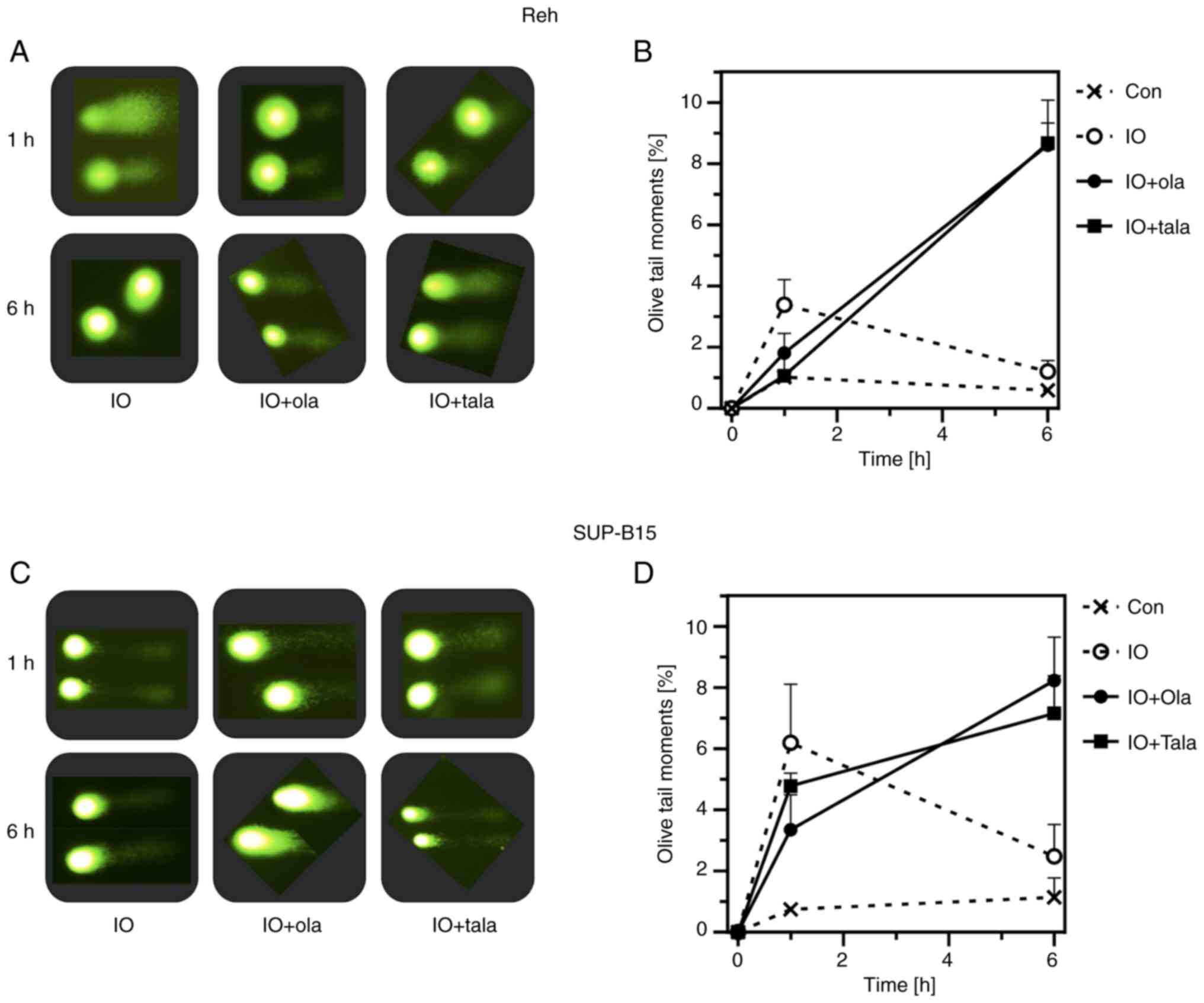

Inhibition of IO-induced DNA damage

repair by PARP inhibitors

The comet assay was conducted to verify DNA damage

and repair. The tail moment is an appropriate indicator of the

amount of DNA damage induced since this value takes under

consideration both the amount of DNA migration and the relative

amount of DNA in the tail (17).

Reh and SUP-B15 cells were treated with IO (2 ng/ml in Reh cells;

20 ng/ml in SUP-B15 cells) in the presence or absence of minimally

toxic concentrations of olaparib or talazoparib for 1 or 6 h.

Representative comet images are shown in Fig. 6A and C. A total of 1 h treatment

with IO induced the comet tail, indicating the induction of DNA

strand breaks. However, the image at 6 h did not reveal any tails,

suggesting that breaks were repaired after that time. Conversely,

in the presence of olaparib or talazoparib, comet tails remained at

6 h, indicating that breaks remained unrepaired by the inhibition

of PARP function. Line graphs revealed that the line for the Olive

tail moment of combination went upwards from 1 to 6 h after drug

administration; by contrast, that of IO alone went down (Fig. 6B and D). Olaparib and talazoparib

were thought to inhibit PARP-dependent SSB repair. These results

suggested that the enhancement of IO cytotoxicity by PARP

inhibitors was attributable to the inhibition of IO-induced DNA

damage repair.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that the combination

of IO with olaparib or talazoparib demonstrated synergistic

anti-leukemic effects via the inhibition of DNA damage repair

mechanisms. As single agents, IO, olaparib and talazoparib all

inhibited cell proliferation in B-ALL cell lines. Combining IO with

either olaparib or talazoparib resulted in greater inhibition of

cell proliferation, showing synergistic effects. Furthermore, the

addition of minimally toxic concentrations of olaparib or

talazoparib combined with IO increased apoptosis. The comet assay

demonstrated that DNA strand breaks induced by IO alone had almost

disappeared by 6 h, suggesting successful completion of DNA repair.

However, in the presence of olaparib or talazoparib, DNA strand

breaks persisted even at 6 h, suggesting the inhibition of the DNA

repair function. These results indicated that the cytotoxicity of

IO was enhanced by olaparib or talazoparib via inhibition of DNA

damage repair.

SSBs are repaired by base excision repair (BER) and

nucleotide excision repair (18),

while DSBs are repaired by homologous recombination and

non-homologous end rejoining (19–21).

Calicheamicin, as the payload of IO, exhibits cytotoxicity by

inducing both SSBs and DSBs. The ratio of DSBs to SSBs among

cellular DNA is 1:3, close to the 1:2 ratio observed when

calicheamicin g1 cleaves purified plasmid DNA (22). PARP senses and binds to SSBs, then

forms long chains of poly(ADP-ribose) to recruit DNA repair

proteins involved in BER (23).

PARP inhibitors achieve cytotoxicity by inhibiting SSB repair. In

the presence of PARP inhibitors, calicheamicin-induced SSBs are not

repaired, and unrepaired SSBs convert to accumulating DSBs during

DNA replication, resulting in cell death. The strategy of combining

IO with PARP inhibitors thus achieves synergistic effects based on

a different concept from synthetic lethality. Previous studies have

reported that doxorubicin, which causes both SSBs and DSBs, similar

to calicheamicin, in combination with olaparib also demonstrated

synergistic effects in breast cancer and leukemia cells (24,25).

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin, an antibody-drug conjugate similar to IO,

reportedly demonstrated synergistic effects on CD33+

myeloid leukemia cells in combination with olaparib (26). Moreover, PARP1 was previously

revealed to be involved in DSB repair (27–30).

Combining IO with PARP inhibitors thus appears to represent a

reasonable strategy to enhance the cytotoxicity of IO.

Tirrò et al (31) investigated the cytotoxicity of IO in

CD22+ cells from the perspective of checkpoint kinase1

(Chk1) inhibition. When CD22+ cells were treated with

IO, the surviving cells were arrested in the G2/M phase during

which DNA repair was performed. The Chk1 inhibitor UCNO-1 abrogated

this IO-induced G2/M arrest. Such treatment increased cell death

rates among cells showing mutant p53. That study suggested the

cellular damage response as a therapeutic target for patients with

ALL receiving IO therapy. Takeshita et al (32) reported that cancer cells expressing

the multidrug resistance protein P-glycoprotein (P-gp) were

resistant to IO treatment in vitro. The cell lines used in

the present study did not exhibit P-gp upregulation, therefore the

results of the cytotoxicity experiments performed were not biased

in that regard. Nevertheless, the expression of P-gp should be

evaluated to further clarify the cytotoxicity of IO for RR-ALL in

the light of P-gp.

Jabbour et al (33) investigated the clinical efficacy of

IO combined with mini-hyper-CVD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine and

dexamethasone) chemotherapy with or without blinatumomab in newly

diagnosed elderly patients with Ph−ALL. A total of 135

patients were treated prospectively with standard hyper-CVAD

(cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and dexamethasone)

(n=77) or with the combination of IO plus mini-hyper-CVD with or

without blinatumomab (n=58). The identified 38 patients of each

cohort were compared with standard hyper-CVAD and mini hyper-CVD

plus IO using a propensity score matching. The 3-year event-free

survival rates were 34 and 64%, respectively (P=0.003). The 3-year

OS rates were 34 and 63%, respectively (P=0.004). Moreover, the

authors also investigated the clinical efficacy of IO combined with

mini-hyper-CVD chemotherapy. Mini-hyper CVD plus IO were performed

in combination with or without blinatumomab. Of 110 patients

(median age 37 years), 91 patients (83%) responded with 69 CR

(63%). Median OS was 17 months (34). Thus, more effective and less toxic

combination regimens are needed to improve the clinical efficacy of

ALL treatment.

A limitation of the present study includes the use

of cell lines only for experimentation. Although cancer cell lines

are widely used in basic research, cell lines do not completely

represent the molecular features of primary tumor cells (35). Cell lines likely represent a

subpopulation of the original tumor because of cell culture without

the original microenvironment, resulting in genetic or epigenetic

differences between cell lines and primary tumor cells (36). Therefore, experiments using primary

ALL cells for evaluation the efficacy of the combination therapy of

IO with PARP inhibitors are desired. The present study has another

limitation with regards to safety evaluation. The maximum drug

concentration of IO administration reached 200 ng/ml with the

half-life of 130 h in clinic (4,37).

Therefore, the IO concentrations used in the present study (2–100

ng/ml) were markedly lower, which can assure the safety. Moreover,

PARP inhibitors were used at minimally toxic concentrations in the

combination with IO [olaparib (1 µM in Reh cells and 10 nM in

SUP-B15 cells] or talazoparib (100 nM in Reh cells and 1 nM in

SUP-B15 cells)) here. These concentrations also were markedly lower

than the maximum drug concentration in clinic (olaparib 8.43 µg/ml,

talazoparib 13.78 ng/ml) (38,39).

Several clinical trials for combination therapy of chemotherapeutic

drugs with PARP inhibitors have been reported (40–42).

There was a major issue with a narrow therapeutic window. Both

chemotherapeutic drugs and PARP inhibitors are not selective for

tumor cells, therefore PARP inhibition of normal cells enhances the

toxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs, including myelosuppression. On

the other hand, IO targets CD22+ leukemic cells, not

other normal cells including neutrophils. The interaction between

IO and PARP inhibitors theoretically occurs in CD22+

leukemic cells, which will not increase adverse reactions in the

patient's body. To confirm the safety of this combination therapy,

experiments using patient-derived tumor xenografts as pre-clinical

models are also necessary (43).

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated

synergistic anti-leukemic effects from the combination of IO with

olaparib or talazoparib. There were no previous studies of clinical

trials on the combination of IO with PARP inhibitors. Therefore,

the present study is considered to be highly novel. The impact of

such combination is dependent on the inhibition of DNA damage

repair. In ALL cells, IO-induced DNA strand breaks were inhibited

by PARP inhibitors. Such combination may not increase damage to

normal cells, since IO specifically targets CD22+ cancer

cells. Targeting the inhibition of DNA damage repair may thus

represent a potent therapeutic strategy for ALL.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Life Science Research

Laboratory in the Division of Bioresearch, University of Fukui for

the use of research instruments. Parts of the present study were

presented in the 65th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting

and Exposition in December 9–12, 2023. Inotuzumab ozogamicin was

kindly provided by Pfizer, Inc.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

NI, MO, ST, NH and TY have participated sufficiently

in the conception and design of the study and were involved in the

acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, as well as

drafting the manuscript. NI acquired and analyzed the data,

produced the figures, and wrote the manuscript as principal

investigator. ST was involved in acquisition and interpretation of

data. MO and TY confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. NH

supervised the study design and critically revised the work for

important intellectual content. TY developed the study concept and

designed the work. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

IO

|

inotuzumab ozogamicin

|

|

RR-ALL

|

relapsed or refractory acute

lymphoblastic leukemia

|

|

CD

|

cluster of differentiation

|

|

B-ALL

|

B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia

|

|

PARP

|

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

|

|

Ph

|

Philadelphia

|

|

IC50

|

half-maximal inhibitory

concentration

|

|

OS

|

overall survival

|

|

HSCT

|

hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation

|

|

CR

|

complete remission

|

|

SSBs

|

single strand breaks

|

|

DSBs

|

double strand breaks

|

|

BRCA

|

breast cancer susceptibility gene

|

|

ATCC

|

American Type culture collection

|

|

FBS

|

fatal bovine serum

|

|

FITC

|

fluorescein isothiocyanate

|

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

CI

|

combination index

|

|

BER

|

base excision repair

|

|

Chk1

|

checkpoint kinase 1

|

|

P-gp

|

P-glycoprotein

|

|

CVD

|

cyclophosphamide, vincristine and

dexamethasone

|

|

CVAD

|

cyclophosphamide, vincristine,

doxorubicin and dexamethasone

|

References

|

1

|

Annino L, Vegna ML, Camera A, Specchia G,

Visani G, Fioritoni G, Ferrara F, Peta A, Ciolli S, Deplano W, et

al: Treatment of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL):

Long-Term follow-up of the GIMEMA ALL 0288 randomized study. Blood.

99:863–871. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Takeuchi J, Kyo T, Naito K, Sao H,

Takahashi M, Miyawaki S, Kuriyama K, Ohtake S, Yagasaki F, Murakami

H, et al: Induction therapy by frequent administration of

doxorubicin with four other drugs, followed by intensive

consolidation and maintenance therapy for adult acute lymphoblastic

leukemia: The JALSG-ALL93 study. Leukemia. 16:1259–1266. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gökbuget N, Stanze D, Beck J, Diedrich H,

Horst HA, Hüttmann A, Kobbe G, Kreuzer KA, Leimer L, Reichle A, et

al: Outcome of relapsed adult lymphoblastic leukemia depends on

response to salvage chemotherapy, prognostic factors, and

performance of stem cell transplantation. Blood. 120:2032–2041.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kantarjian HM, DeAngelo DJ, Stelljes M,

Martinelli G, Liedtke M, Stock W, Gökbuget N, O'Brien S, Wang K,

Wang T, et al: Inotuzumab ozogamicin versus standard therapy for

acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 375:740–753. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kantarjian HM, DeAngelo DJ, Stelljes M,

Liedtke M, Stock W, Gökbuget N, O'Brien SM, Jabbour E, Wang T,

Liang White J, et al: Inotuzumab ozogamicin versus standard of care

in relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Final

report and long-term survival follow-up from the randomized, phase

3 INO-VATE study. Cancer. 125:2474–2487. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kantarjian HM, Su Y, Jabbour EJ,

Bhattacharyya H, Yan E, Cappelleri JC and Marks DI:

Patient-Reported outcomes from a phase 3 randomized controlled

trial of inotuzumab ozogamicin versus standard therapy for

relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer.

124:2151–2160. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

de Vries JF, Zwaan CM, De Bie M, Voerman

JSA, den Boer ML, van Dongen JJM and van der Velden VHJ: The novel

calicheamicin-conjugated CD22 antibody inotuzumab ozogamicin

(CMC-544) effectively kills primary pediatric acute lymphoblastic

leukemia cells. Leukemia. 26:255–264. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rose M, Burgess JT, O'Byrne K, Richard DJ

and Bolderson E: PARP inhibitors: Clinical relevance, mechanisms of

action and tumor resistance. Front Cell Dev Biol. 8:5646012020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

DiSilvestro P, Colombo N, Harter P,

González-Martín A, Ray-Coquard I and Coleman RL: Maintenance

treatment of newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer: Time for a

paradigm shift? Cancers (Basel). 13:57562021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker

KM, Flower D, Lopez E, Kyle S, Meuth M, Curtin NJ and Helleday T:

Specific killing of BRCA2-Deficient tumours with inhibitors of

poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase. Nature. 434:913–917. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Cortesi L, Rugo HS and Jackisch C: An

overview of PARP inhibitors for the treatment of breast cancer.

Targ Oncol. 16:255–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chou TC: Drug combination studies and

their synergy quantification using the chou-talalay method. Cancer

Res. 70:440–446. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bhatla T, Wang J, Morrison DJ, Raetz EA,

Burke MJ, Brown P and Carroll WL: Epigenetic reprogramming reverses

the relapse-specific gene expression signature and restores

chemosensitivity in childhood B-Lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood.

119:5201–5210. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Uy N, Nadeau M, Stahl M and Zeidan AM:

Inotuzumab ozogamicin in the treatment of relapsed/refractory acute

B cell lymphoblastic leukemia. J Blood Med. 9:67–74. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Pardee TS, Stadelman K, Gee JJ, Caudell DL

and Gmeiner WH: The poison oligonucleotide F10 is highly effective

against acute lymphoblastic leukemia while sparing normal

hematopoietic cells. Oncotarget. 5:4170–4179. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Punzo F, Argenziano M, Tortora C, Paola

AD, Mutarelli M, Pota E, Martino MD, Pinto DD, Marrapodi MM,

Roberti D, et al: Effect of CB2 stimulation on gene expression in

pediatric B-Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: New possible targets. Int

J Mol Sci. 23:86512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kumaravel TS, Vilhar B, Faux SP and Jha

AN: Comet assay measurements: A perspective. Cell Biol Toxicol.

25:53–64. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Madhusudan S and Hickson ID: DNA Repair

inhibition: A selective tumour targeting strategy. Trends Mol Med.

11:503–511. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Moynahan ME and Jasin M: Mitotic

homologous recombination maintains genomic stability and suppresses

tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 11:196–207. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ceccaldi R, Rondinelli B and D'Andrea AD:

Repair pathway choices and consequences at the double-strand break.

Trends Cell Biol. 26:52–64. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

O'Connor MJ: Targeting the DNA damage

response in cancer. Mol Cell. 60:547–560. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Elmroth K, Nygren J, Mårtensson S, Ismail

IH and Hammarsten O: Cleavage of cellular DNA by calicheamicin

gamma1. DNA Repair (Amst). 2:363–374. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Javle M and Curtin NJ: The role of PARP in

DNA repair and its therapeutic exploitation. Br J Cancer.

105:1114–1122. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mariano G, Ricciardi MR, Trisciuoglio D,

Zampieri M, Ciccarone F, Guastafierro T, Calabrese R, Valentini E,

Tafuri A, Bufalo DD, et al: PARP inhibitor ABT-888 affects response

of MDA-MB-231 cells to doxorubicin treatment, targeting snail

expression. Oncotarget. 6:15008–15021. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wu J, Xiao S, Yuan M, Li Q, Xiao G, Wu W,

Ouyang Y, Huang L and Yao C: PARP inhibitor re-sensitizes

adriamycin resistant leukemia cells through DNA damage and

apoptosis. Mol Med Rep. 19:75–84. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yamauchi T, Uzui K, Nishi R, Shigemi H and

Ueda T: Gemtuzumab ozogamicin and olaparib exert synergistic

cytotoxicity in CD33-positive HL-60 myeloid leukemia cells.

Anticancer Res. 34:5487–5494. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ariumi Y, Masutani M, Copeland TD, Mimori

T, Sugimura T, Shimotohno K, Ueda K, Hatanaka M and Noda M:

Suppression of the poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase activity by

DNA-dependent protein kinase in vitro. Oncogene. 18:4616–4625.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Galande S and Kohwi-Shigematsu T:

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and Ku autoantigen form a complex and

synergistically bind to matrix attachment sequences. J Biol Chem.

274:20521–20528. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Haince JF, Kozlov S, Dawson VL, Dawson TM,

Hendzel MJ, Lavin MF and Poirier GG: Ataxia telangiectasia mutated

(ATM) signaling network is modulated by a novel

poly(ADP-ribose)-dependent pathway in the early response to

DNA-damaging agents. J Biol Chem. 282:16441–16453. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Haince JF, McDonald D, Rodrigue A, Déry U,

Masson JY, Hendzel MJ and Poirier GG: PARP1-dependent kinetics of

recruitment of MRE11 and NBS1 proteins to multiple DNA damage

sites. J Biol Chem. 283:1197–1208. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Tirrò E, Massimino M, Romano C, Pennisi

MS, Stella S, Vitale SR, Fidilio A, Manzella L, Parrinello NL,

Stagno F, et al: Chk1 inhibition restores inotuzumab ozogamicin

citotoxicity in CD22-positive cells expressing mutant P53. Front

Oncol. 9:572019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Takeshita A, Shinjo K, Yamakage N, Ono T,

Hirano I, Matsui H, Shigeno K, Nakamura S, Tobita T, Maekawa M, et

al: CMC-544 (inotuzumab ozogamicin) shows less effect on multidrug

resistant cells: Analyses in cell lines and cells from patients

with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and lymphoma. Br J

Haematol. 146:34–43. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Jabbour EJ, Sasaki K, Ravandi F, Short NJ,

Garcia-Manero G, Daver N, Kadia T, Konopleva M, Jain N, Cortes J,

et al: Inotuzumab ozogamicin in combination with low-intensity

chemotherapy (Mini-HCVD) with or without blinatumomab versus

standard intensive chemotherapy (HCVAD) as frontline therapy for

older patients with philadelphia chromosome-negative acute

lymphoblastic leukemia: A propensity score analysis. Cancer.

125:2579–2586. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Kantarjian H, Haddad FG, Jain N, Sasaki K,

Short NJ, Loghavi S, Kanagal-Shamanna R, Jorgensen J, Khouri I,

Kebriaei P, et al: Results of salvage therapy with mini-hyper-CVD

and inotuzumab ozogamicin with or without blinatumomab in pre-B

acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 16:442023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Javad N, Francisca V and James MM:

Bridging the gap between cancer cell line models and tumours using

gene expression data. Br J Cancer. 125:311–312. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Wilding JL and Bodmer WF: Cancer cell

lines for drug discovery and development. Cancer Res. 74:2377–2384.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ricart AD: Antibody-drug conjugates of

calicheamicin derivative: Gemtuzumab ozogamicin and inotuzumab

ozogamicin. Clin Cancer Res. 17:6417–6427. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yonemori K, Tamura K, Kodaira M, Fujikawa

K, Sagawa T, Esaki T, Shirakawa T, Hirai F, Yokoi Y, Kawata T, et

al: Safety and tolerability of the olaparib tablet formulation in

Japanese patients with advanced solid tumours. Cancer Chemother

Pharmacol. 78:525–531. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Naito Y, Kuboki Y, Ikeda M, Harano K,

Matsubara N, Toyoizumi S, Mori Y, Hori N, Nagasawa T and Kogawa T:

Safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary efficacy of the PARP

inhibitor talazoparib in Japanese patients with advanced solid

tumors: Phase 1 study. Invest New Drugs. 39:1568–1576. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Lee JM, Peer CJ, Yu M, Amable L, Gordon N,

Annunziata CM, Houston N, Goey AKL, Sissung TM, Parker B, et al:

Sequence-specific pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic phase I/Ib

study of olaparib tablets and carboplatin in Women's cancer. Clin

Cancer Res. 23:1397–1406. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Bang YJ, Xu RH, Chin K, Lee KW, Park SH,

Rha SY, Shen L, Qin S, Xu N, Im SA, et al: Olaparib in combination

with paclitaxel in patients with advanced gastric cancer who have

progressed following first-line therapy (GOLD): A double-blind,

randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.

18:1637–1651. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Oza AM, Cibula D, Benzaquen AO, Poole C,

Mathijissen RHJ, Sonke GS, Colombo N, Spacek J, Vuylsteke P, Hirte

H, et al: Olaparib combined with chemotherapy for recurrent

platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer: A randomised phase 2 trial.

Lamcet Oncol. 16:87–97. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Lai Y, Wei X, Lin S, Qin L, Cheng L and Li

P: Current status and perspectives of patient-derived xenograft

models in cancer research. J Hematol Oncol. 10:1062017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|