Introduction

In 2020, esophageal cancer, a lethal type of cancer,

was responsible for ~5.5% of all cancer-associated fatalities

globally (1). Compared with other

regions globally, the incidence and mortality rates of esophageal

cancer are greater in Asian countries (2). According to the Taiwan Cancer Registry

Annual Report, esophageal cancer ranks ninth for cancer-related

mortality; squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most frequent

histological subtype, accounting for up to 91.4% of all cases

(3). The prognosis is poor for

esophageal SCC (ESCC) due to its aggressive nature, which includes

early distant organ metastases and regional tracheal invasion

(4). Typically, metastasis affects

the liver, lung and lymph nodes (3,5). A

thorough understanding of the intricate processes underlying the

spread of ESCC and distant metastases is essential for future

advancements in early prevention and intervention.

Small non-coding RNA molecules known as microRNAs

(miRNAs/miRs) functionally control gene expression by degrading or

suppressing the translation of mRNA targets (6,7). These

compounds exert key regulatory effects on cellular functions such

as apoptosis, differentiation and cell cycle entry and progression

(8–10). miRNAs typically function as

oncogenes or tumor suppressors in different types of cancer. In

cancer, tumor development, aggressiveness and treatment evasion are

associated with dysregulation of miRNAs (6,11).

miRNAs primarily regulate intricate signaling pathways and networks

that regulate gene expression to regulate the growth and

progression of a tumor with metastases and treatment sensitivity

(12). Targeting oncogenic miRNAs

or boosting tumor suppressor miRNAs in cancer is considered to be a

unique form of cancer treatment (12).

Previous studies have demonstrated that obesity

enhances the risk of cancer progression and metastases,

particularly for malignancy of the kidney, prostate, endometrium,

breast, colon and esophagus (13,14).

Adipocytes secrete bioactive chemicals known as adipokines, which

are key in the advancement of cancer, metabolic disorder,

cardiovascular disease, inflammation and metastasis (15–17).

In the tumor microenvironment, adipokines may trigger the

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and enhance metastasis

(18). Visfatin was originally

revealed in visceral adipose tissue and is considered a

multifunctional adipokine and an extracellular nicotinamide

phosphoribosyltransferase enzyme (19). Patients with numerous types of

cancer have elevated serum levels of visfatin (20,21).

Visfatin is key for the invasion and metastasis of cancer (19,22).

In esophageal cancer, visfatin levels have been documented to be

upregulated compared with those of healthy controls and promote

VEGF-C-regulated lymphangiogenesis (3). However, the regulatory roles of

visfatin in miRNA synthesis and cell motility in esophageal cancer

remain unclear. The aim of the present study was to investigate the

regulatory role of visfatin in miRNA synthesis and to elucidate the

underlying mechanisms by which miRNA influences cell motility in

esophageal cancer.

Materials and methods

Materials

Vascular endothelial zinc finger 1 (VEZF1; cat. no

SC-365560; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) β-actin (cat. no GT5512;

Genetex International Corporation), and versican (VCAN) antibody

(cat. no SAB1408906; MilliporeSigma) were used. Recombinant human

visfatin (cat. no. 130-09-25UG) was obtained from PeproTech, Inc.

The small interfering (si)RNAs targeting VEZF1 (cat no. sc-94046)

and VCAN (cat no. sc-41903) were purchased from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc. A non-targeting negative control siRNA (cat no.

D-001810-10-05) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

PI3K (Ly294002) inhibitor (cat. no. ALX-270-038) was obtained from

Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. AKT (cat. no. A6730) and mTOR (rapamycin)

inhibitors (cat. no. R0395) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck

KGaA). The miR-3613-5p mimic (5′-UGUUGUACUUUUUUUUUUGUUC-3′) and miR

mimic negative control (5′-UUGUACUACACAAAAGUACUG-3′) were purchased

from AllBio. All other reagents and chemicals were obtained from

MilliporeSigma, unless otherwise specified.

Cell culture

The invasive ESCC cell line KYSE-410 (cat no.

94072023) was obtained from the European Collection of Cell

Cultures and human ESCC cell line CE81T (cat. no. 60166) was

purchased from Bioresource Collection and Research Centre. Cells

were cultured in either RPMI-1640 or DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf

serum (Corning, Inc), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100

µg/ml streptomycin. All cells were maintained at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

miRNA sequencing and bioinformatics

analysis

For miRNA sequencing (NEXTflex small RNA sequencing

kit v3, cat no. NOVA-5132-06, PerkinElmer) was utilized,

high-quality total RNA samples from the visfatin (30 ng/ml)-treated

for 24 h at 37°C and untreated control KYSE-410 cells were

utilized. The experimental workflow was performed by Azenta Life

Sciences. To prepare the library, 1 µg total RNA was used

quantified using both Qubit and qPCR methods. The qualified library

were sequenced pair end PE150 (150 pair-End) Small RNA sequencing

was conducted using the Illumina, Inc. HiSeq/Novaseq or MGI2000

platform. Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and RNA integrity was confirmed with an Agilent

2100 Bioanalyzer (RNA integrity number >7). To prevent

adaptor-dimer formation, an excess of 3′ SR Adaptor for Illumina

was hybridized with the SR RT Primer. Subsequently, the 5′ SR

Adaptor for Illumina was ligated to the small RNA using a 5′

Ligation Enzyme. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using

ProtoScript II Reverse Transcriptase (New England Biolabs, US).

Each sample was then amplified by PCR kit (Bioo Scientific,

PerkinElmer) using thermocycling conditions: initial denaturation

95°C for 2 min, 20–25 cycles of denaturation 95°C for 20 sec,

annealing 60°C for 30 sec, Extension 72°C for 15 sec, final

extension 95°C for 2 minusing P5 (Forward,

5′-GTTCAGAGTTCTACAGTCCGACGATC-3′) and P7 (Reverse,

5′-AGATCGGAAGAGCACACGTCT-3′) primers and the PCR product was

purified by DNA Clean Beads (Bioo Scientific, PerkinElmer). The

purified products of 140–160 bp were recovered and cleaned using

PAGE (6%) and validated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. The raw

readings underwent quality control before processing, which

included removing adapter sequences and contaminants. To guarantee

data quality, analysis of the lengths and counts of the filtered

reads was performed by Trimmomatic (V0.30), Cutadapt (V1.3) and

FastQC (V0.10.1), along with an evaluation of the data volume

(9). DEseq2 (V1.6.3), DEseq

(V1.18.0), EdgeR (V3.4.6) and bowtie2 (V2.1.0), software was used

for Heatmap and volcano plot to analyzed differentially expressed

miRNA.

The levels of visfatin in patients with primary and

metastatic esophageal cancer were analyzed using a UALCAN, dataset

and cell motility genes associated with VEZF1 were obtained from

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (3,11).

Target genes were predicted using TargetScan

(targetscan.org/vert_80/), miRTarBase (https://mirtarbase.cuhk.edu.cn), miRDB (https://mirdb.org/) and ENCORI (https://rnasysu.com/encori/index.php) databases

(24). Spearman correlation was

used to analyze gene correlation. Gene expression levels in ESCC

patients were analyzed using the GEO dataset GSE161533.

Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to assess the VCAN levels in

ESCC. Expression levels of Visfatin, VEZF1, and VCAN were evaluated

using GSE77861, while miR-3613-5p levels were examined using

GSE97051 in ESCC patient tissues.

Migration and invasion assay

Transwell inserts (Costar, Inc.; 8-µm pores) were

used in 24-well plates for the migration experiments and pre-coated

with a layer of Matrigel at 37°C for 30 min before the invasion

assay. KYSE410 and CE81T Cells were pretreated with or without (10

µM) of PI3K (Ly294002), AKT inhibitor (AKTi), mTOR (Rapamycin)

inhibitors. KYSE410 and CE81T cells were transfected using

(Lipofectamine 2000, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

with or without siVEZF1, siVCAN siRNAs and miRNA mimics (50 nM) and

incubated at 37°C for 24 h, immediately followed by migration and

invasion assay. The upper chamber contained 1×104

KYSE410 and CE81T cells in 200 µl serum-free medium (DMEM or RPMI),

whereas the lower chamber contained 300 µl 10% FBS and medium with

various concentrations (1,3,10, 30)

ng/ml of visfatin and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in 5%

CO2. Cotton-tipped swabs were used to remove the

Matrigel from the upper side of the filters, and PBS was used to

wash the filters (23,24). Cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde

for 5 min at room temperature, incubated for 24 h at 37°C in 5%

CO2 and stained with 0.05% crystal violet in PBS for 20

min at room temperature. Stained cells were observed under an

Olympus CKX53 inverted light microscope, and quantified by ImageJ

(V1.52a; imagej.net/ij/) and GraphPad prism (V8.0;

graphpad.com/guides/prism/8/user-guide/index.htm).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q)PCR

TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) cat no. 12183555)

was used to extract total RNA from the esophageal cancer KYSE410

cells. In summary, oligo-dT primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), 10 mM dNTP (Cyrusbioscience), 5× standard buffer

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 0.1 M DTT (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used to reverse-transcribe 1 µg RNA

into cDNA in compliance with the manufacturer's instructions. The

KAPA SYBER FAST qPCR kit (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) was used to mix 100 ng cDNA sample with specific

primers. qPCR was performed using a Senso Quest Labcycler thermal

cycler. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial

denaturation at 95°C for 6 min, followed by 40 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing at 60°C for 30 sec and

extension at 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 10

min. The Mir-XTM miRNA First Strand Synthesis kit (Takara Bio Inc.)

was used to create cDNA from 100 ng total RNA for the miRNA assay.

The endogenous control GAPDH was used to achieve relative

quantification of gene expression. The comparative Cq approach was

performed to calculate the relative expression (25,26).

The sequences of primers were as follows: miR-3613-5p,

5′-TGTTGTACTTTTTTTTTTGTTC-3′ (melting temperature (Tm), 43.7°C;

length, 22 bases); VEZF1: Forward, 5′-GGTTCTGCAGCATTTCACCC-3′ and

reverse, 5′-TGATGGGAAGCTTCATGGGC-3′ (Tm, 53.8°C; length, 20 bases

each); VCAN: Forward, 5′-GTAACCCATGCGCTACATAAAGT-3′ (Tm, 53.5°C;

length, 23 bases) and reverse, 5′-GGCAAAGTAGGCATCGTTGAAA-3′ (Tm,

53.0°C; length, 22 bases) and GAPDH: Forward

5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ (Tm, 53.5°C, length, 20 bases) and

reverse, 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′ (Tm, 53.8, length, 20 bases).

Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method (27).

Western blot analysis

Proteins from KYSE410 cells were extracted using

RIPA lysis buffer (cat. No. P0012, Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). The total protein concentration was determined

using a BCA Protein Assay Kit and 30 µg of protein per lane was

used for analysis. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using a 10%

gel and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Merck KGaA). Membranes

were blocked with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature for 1 h and

incubated with primary antibodies VEZF1 (1:1,000), VCAN (1:1,000)

as target proteins and β-actin (1:3,000) for an entire night (18–20

h) at 4°C. Membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature

with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies

(1:5,000) goat anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. sc-516102), Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc. An ECL kit (MilliporeSigma) was used to detect

the expression of the target protein and an ImageQuant LAS 4000

biomolecular imager was used for visualization (28,29).

Luciferase reporter assay

A luciferase assay kit was utilized to track the

luciferase activity in order to measure the 3′-untranslated region

(UTR). After transfecting the cells with either the wild-type (wt)-

or mutant (mt)-VEZF1-3′-UTR luciferase plasmid (Stratagene; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.), using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific) the cells were transfected for 24 h at 37°C

using miR-3613-5p mimic (sequence: 5′-ACAAAAAAAAAAGUACAACAUU-3′;

(AllBio). Following 24 h transfection, cells were lysis and

instantly the luciferase activity was measured using the

Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega

Corporation). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla

luciferase activity to control for transfection efficiency.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using ImageJ software (V1.52a)

(https://imagej.net/ij/) and GraphPad Prism

software (V8.0) (graphpad.com/guides/prism/8/user-guide/index.htm).

All data are presented as the mean ± SD from 3 independent

experiments. Statistical significance between two groups was

assessed using the unpaired Student's t-test. Comparisons involving

>2 groups with a single variable were performed using one-way

ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Visfatin promotes esophageal cancer

migration by inhibiting miR-3613-5p

Visfatin is key for the development of numerous

types of cancer (3,30). However, the mechanisms through which

visfatin affects esophageal cancer metastases remain unknown. The

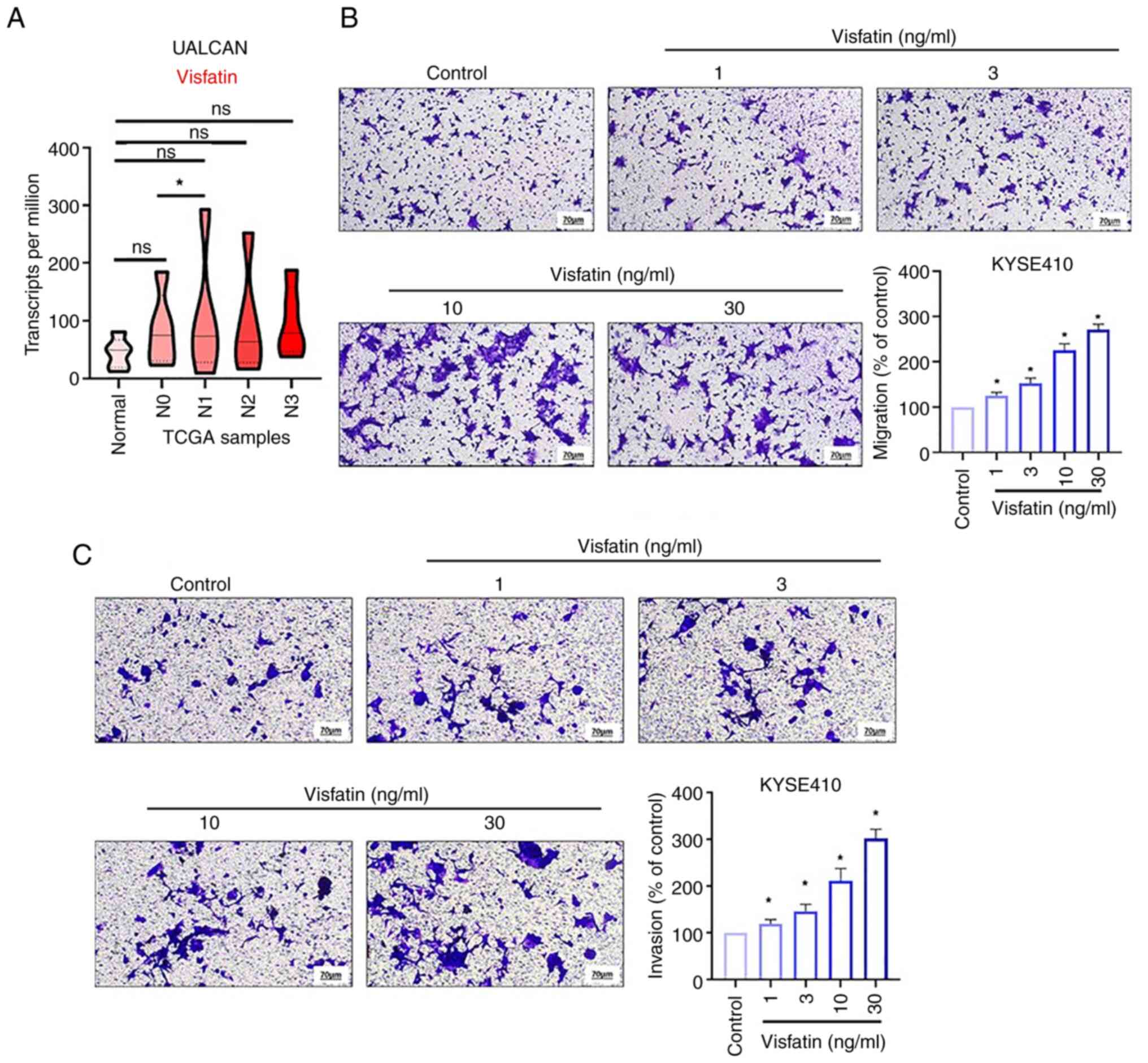

UALCAN data revealed that the levels of visfatin were higher in

patients with metastatic esophageal cancer than in those with

primary esophageal cancer (Fig.

1A). Transwell migration assay was used to examine the effects

of visfatin on the migration of esophageal cancer cells. Visfatin

promoted the migration of KYSE-410 esophageal cancer cells in a

concentration-dependent manner (Fig.

1B). Additionally, visfatin enhanced the invasive ability of

esophageal cancer cells (Fig.

1C).

The metastasis of esophageal cancer is associated

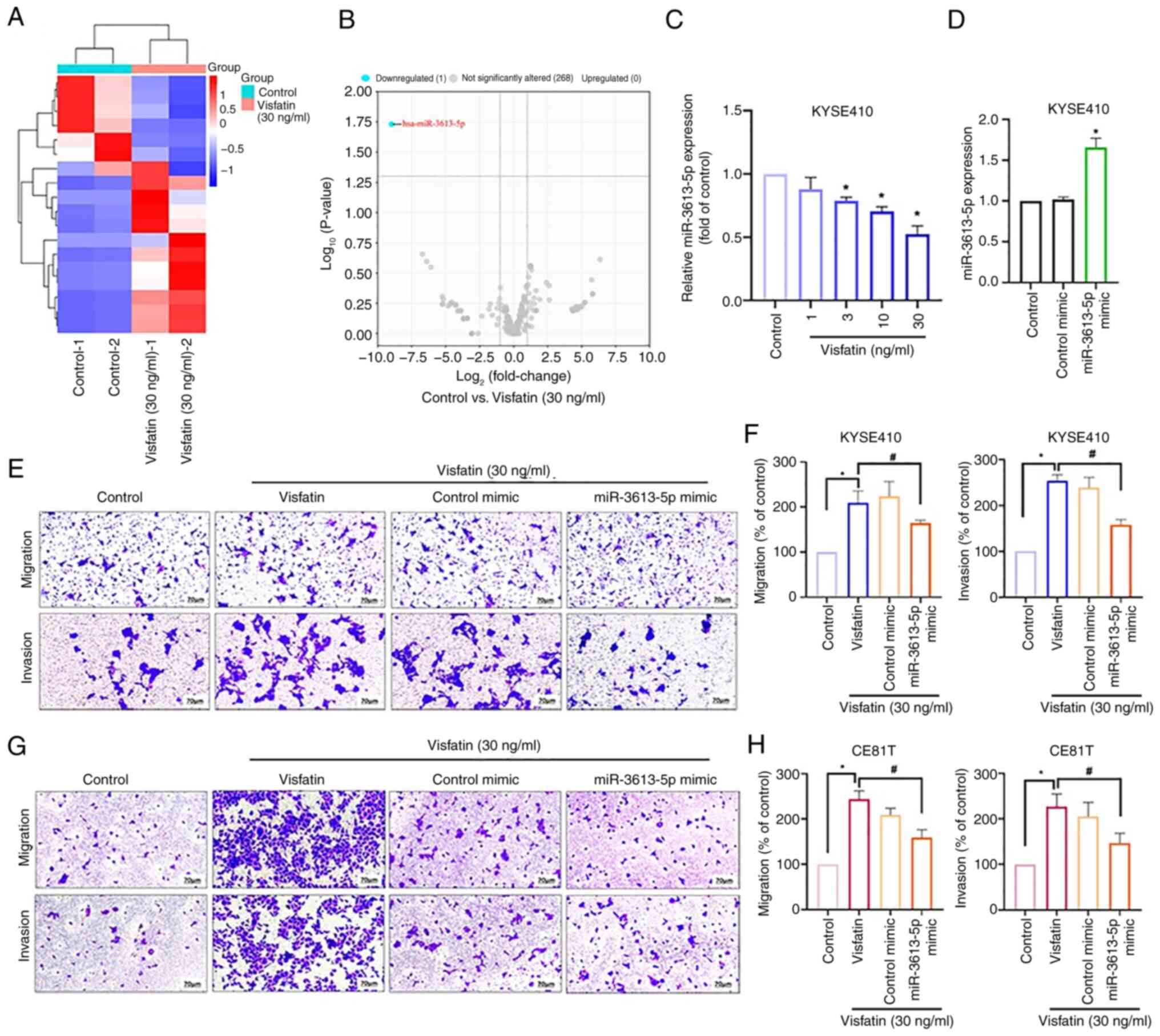

with dysregulated miRNAs (31). To

investigate whether miRNAs mediate visfatin-induced esophageal

cancer cell migration, miRNA sequencing was performed to assess the

differential expression of miRNAs in KYSE-410 cells treated with

visfatin. The resulting heatmap and volcano plot illustrated

differentially expressed miRNAs (Fig.

2A and B); among these, miR-3613-5p was the most downregulated

(Fig. 2B). Visfatin (≥3 ng/ml)

inhibited miR-3613-5p synthesis in a concentration-dependent manner

(Fig. 2C). Transfection with a

miR-3613-5p mimic increased the miR-3613-5p expression compared

with control (Fig. 2D). miR-3613-5p

mimic antagonized the visfatin-induced promotion of cell migration

and invasion (Fig. 2E and F).

Consistent with the KYSE-410 results, miR-3613-5p mimic treatment

inhibited visfatin-induced migration and invasion in CE81T cells

(Fig. 2G and H). Thus, these

findings demonstrate that visfatin promoted esophageal cancer cell

migration by decreasing miR-3613-5p production.

miR-3613-5p inhibits the VEZF1/VCAN

axis and mediates visfatin-promoted cell migration

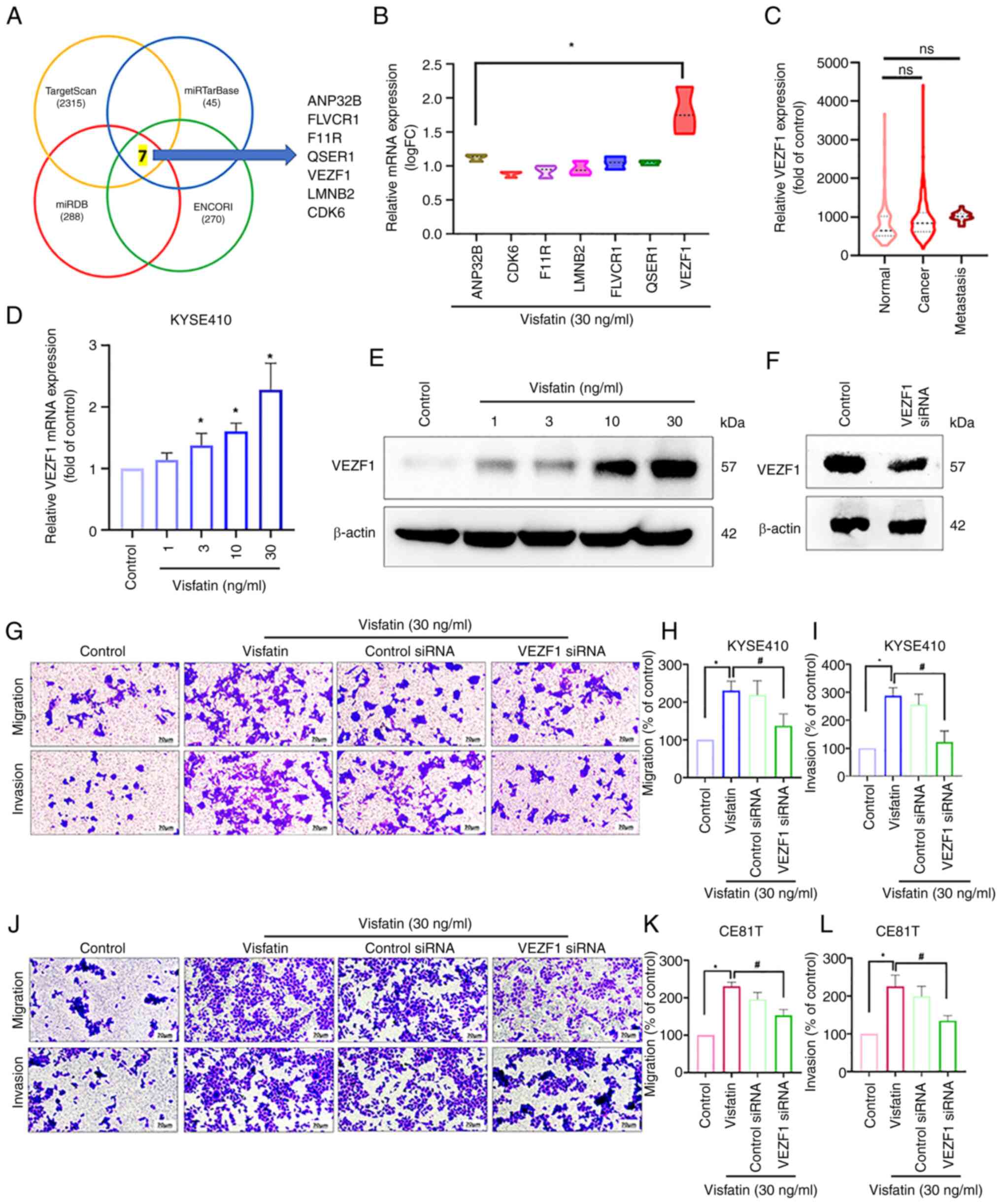

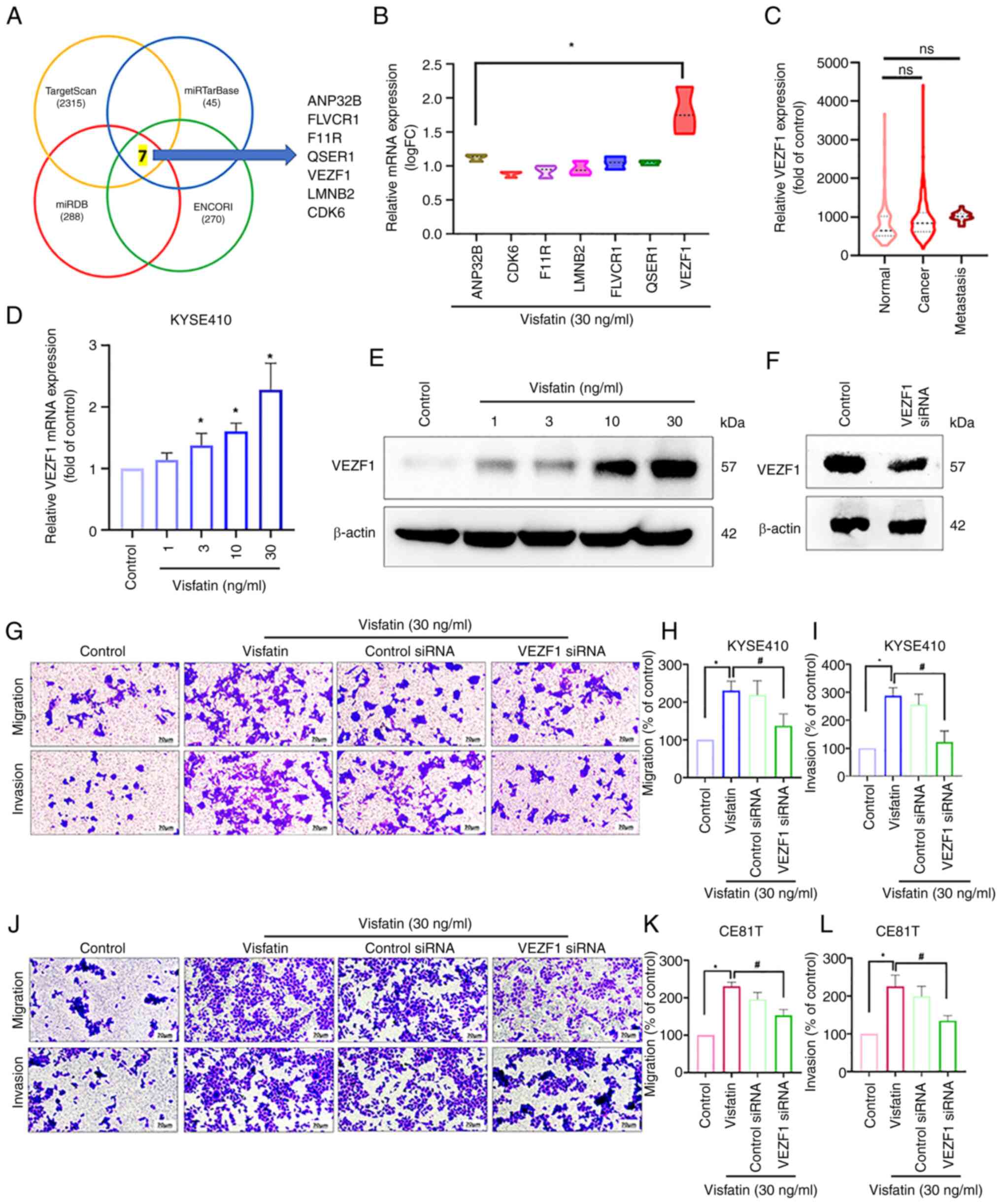

A total of four publicly available miRNA databases

(TargetScan, miRTarBase, miRDB and ENCORI) predicted that

miR-3613-5p targets seven potential candidates (Fig. 3A). Among these, VEZF1 was markedly

upregulated compared with ANP32B in patients with esophageal cancer

(Fig. 3B). Additionally, VEZF1 was

more highly upregulated in patients with metastatic than in those

with primary esophageal cancer, however this was not significant

(Fig. 3C). The direct application

of visfatin to esophageal cancer cells enhanced VEZF1 mRNA and

protein expression (Fig. 3D and E).

Transfection of the cells with VEZF1 siRNA, effectively suppressed

VEZF1 protein levels, as confirmed by western blot analysis

(Fig. 3F), and inhibited the

visfatin-induced promotion of cell migration and invasion (Fig. 3G-I). These findings were validated

in CE81T cells, where VEZF1 siRNA also reversed visfatin-induced

cell motility, confirming a consistent effect across ESCC cell

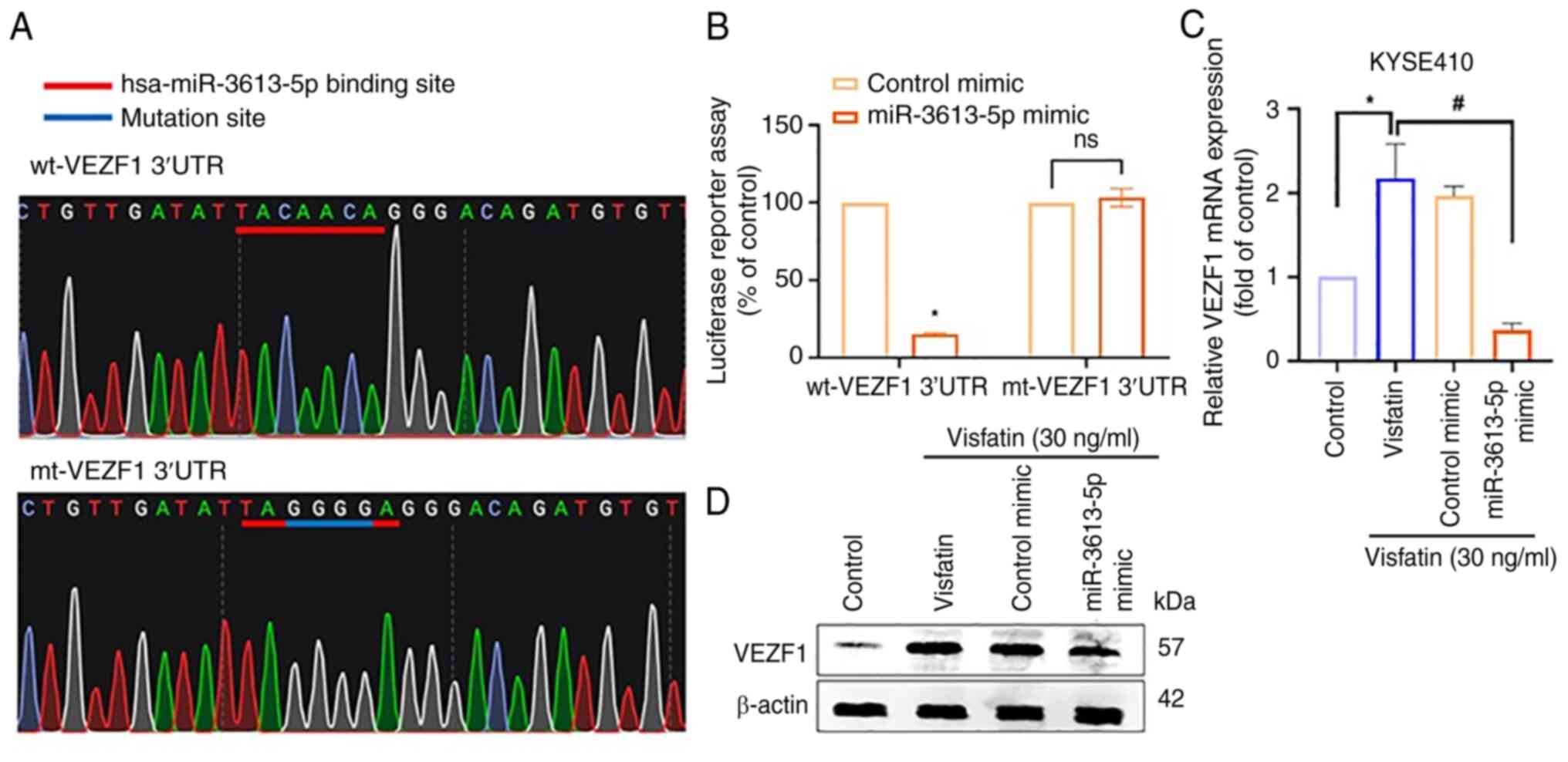

lines (Fig. 3J-L). Subsequently,

wt- and mt-VEZF1-3′-UTR luciferase plasmids were generated to

examine the direct binding effects of miR-3613-5p on VEZF1

(Fig. 4A). The miR-3613-5p mimic

decreased wt-VEZF1-3′-UTR, but not mt-VEZF1-3′-UTR luciferase

activity (Fig. 4B). Furthermore,

the miR-3613-5p mimic blocked visfatin-induced VEZF1 mRNA

expression (Fig. 4C) and protein

levels (Fig. 4D).

| Figure 3.VEZF1, regulated by miR-3613-5p, is

involved in visfatin-induced esophageal cancer cell migration. (A)

miR databases (TargetScan, miRTarBase, miRDB and ENCORI) predicted

that miR-3613-5p targets seven potential candidates. (B) Gene

levels in patients with esophageal cancer retrieved from TCGA. (C)

VEZF1 gene levels in normal tissue and tissues from patients with

primary and metastatic esophageal cancer retrieved from TCGA. (D)

KYSE 410 cells were stimulated with visfatin, and VEZF1 expression

was examined using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and (E)

western blot analysis. (F) VEZF1 siRNA transfection efficiency

examined by western blot. (G) KYSE410 cells were transfected with

VEZF1 siRNA and treated with visfatin, then cell (H) migration and

(I) cell invasion was examined. (J) CE81T cells were transfected

with VEZF1 siRNA followed by visfatin treatment and then (K)

Migration and (L) invasion was examined. *P<0.05 vs. control;

#P<0.05 vs. visfatin. miR, microRNA; TCGA, The Cancer

Genome Atlas; VEZF1, Vascular endothelial Zinc Finger 1; si, small

interfering; FC, fold change; ANP32B, Acidic Leucine-Rich Nuclear

Phosphoprotein 32 Family Member B; CDK, Cyclin-dependent kinase;

F11R, F11 receptor; LMNB2, Lamin B2; FLVCR, Feline Leukemia Virus

subgroup C Receptor 1; QSER, Glutamine and Serine-rich protein 1;

ns, not significant. |

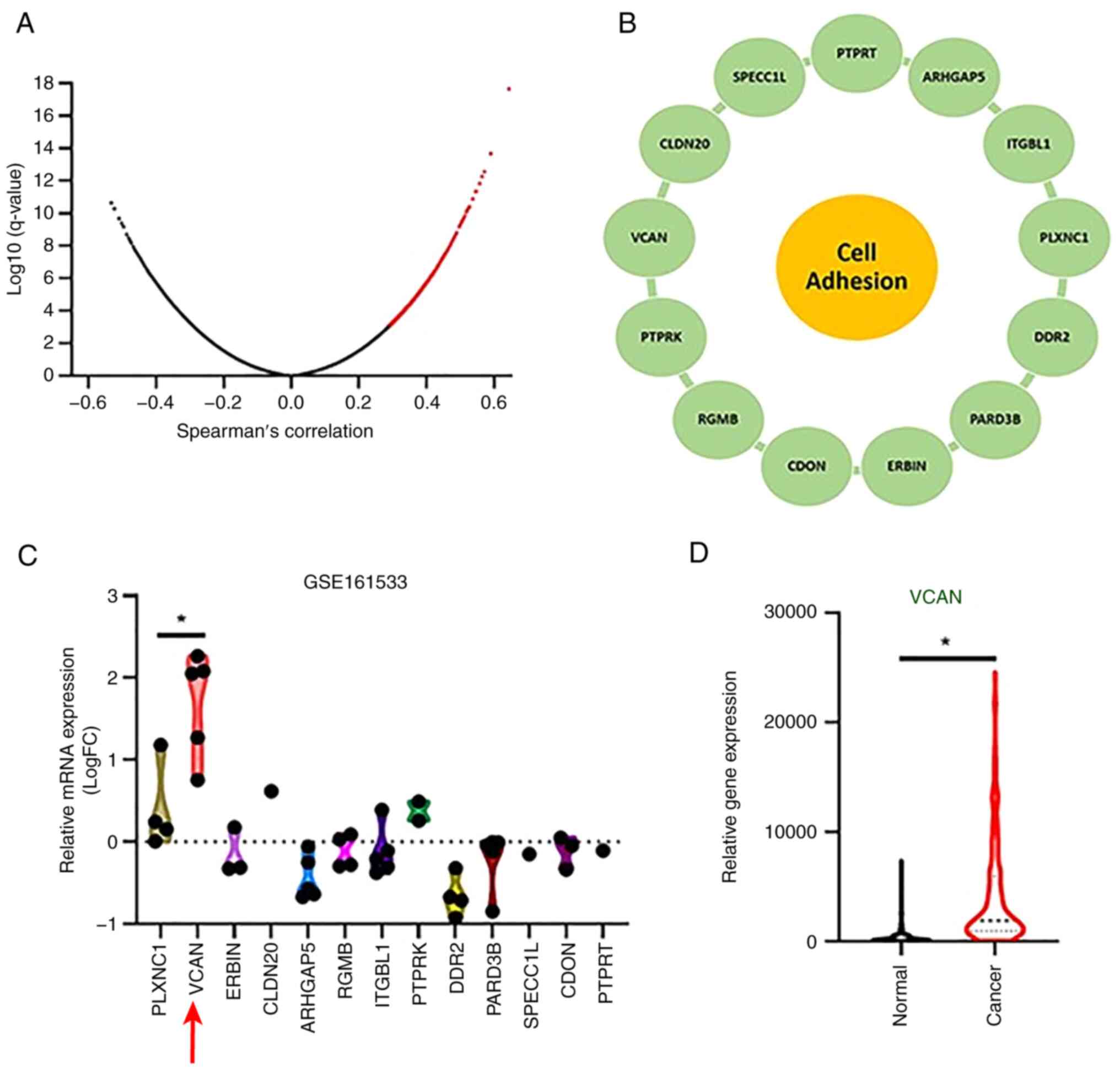

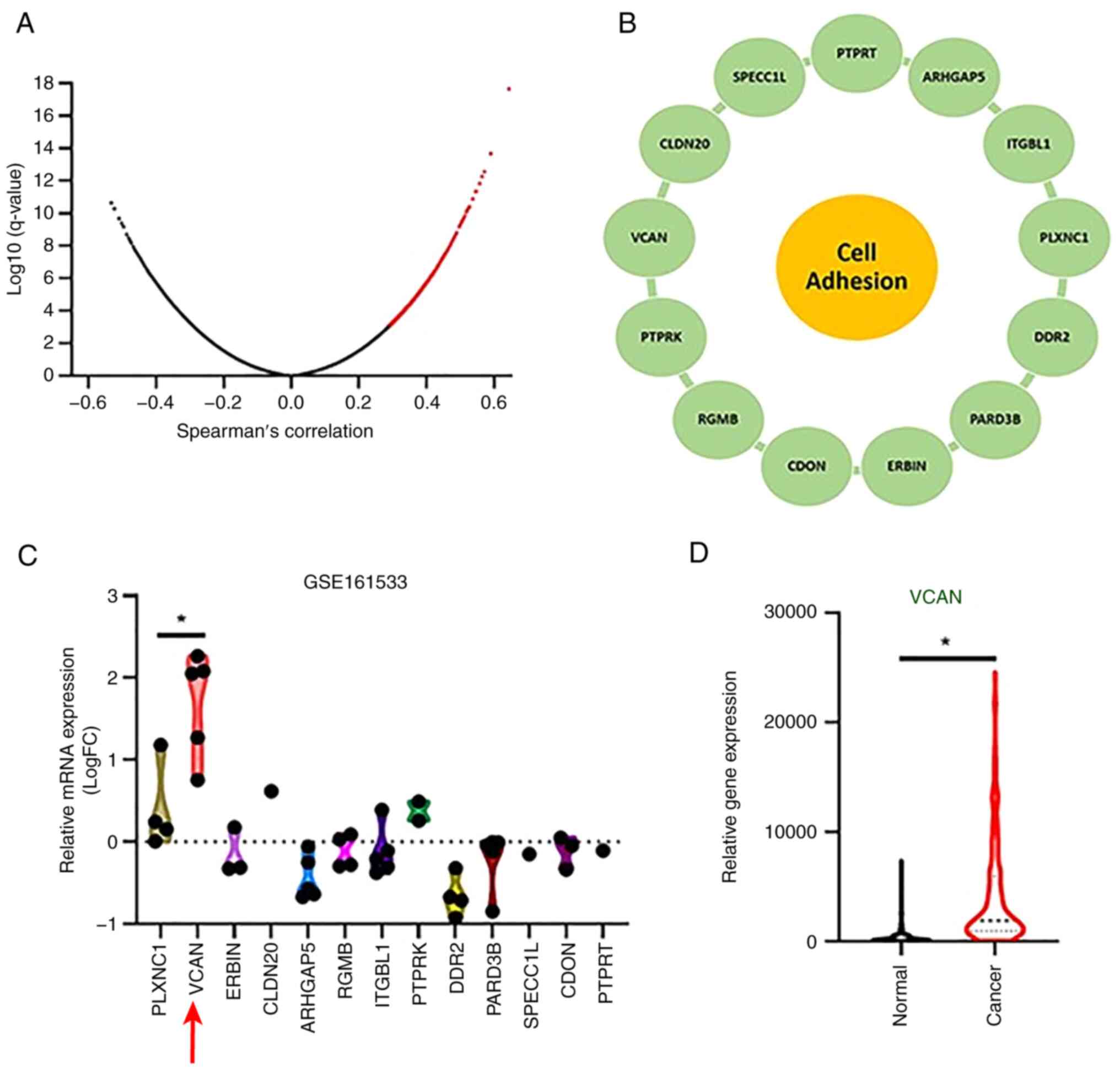

To investigate whether the visfatin-induced

expression of VEZF1 regulates cell motility genes, TCGA database

was searched for genes associated with VEZF1 (Fig. 5A). Among 300 genes exhibiting a

positive correlation, 13 genes were also associated with cell

adhesion functions (Fig. 5B). Data

from the GSE161533 database indicated that VCAN was the most

upregulated gene in patients with esophageal cancer (Fig. 5C). Kaplan-Meier analysis confirmed

that the VCAN levels were higher in patients with esophageal cancer

than in healthy controls (Fig. 5D).

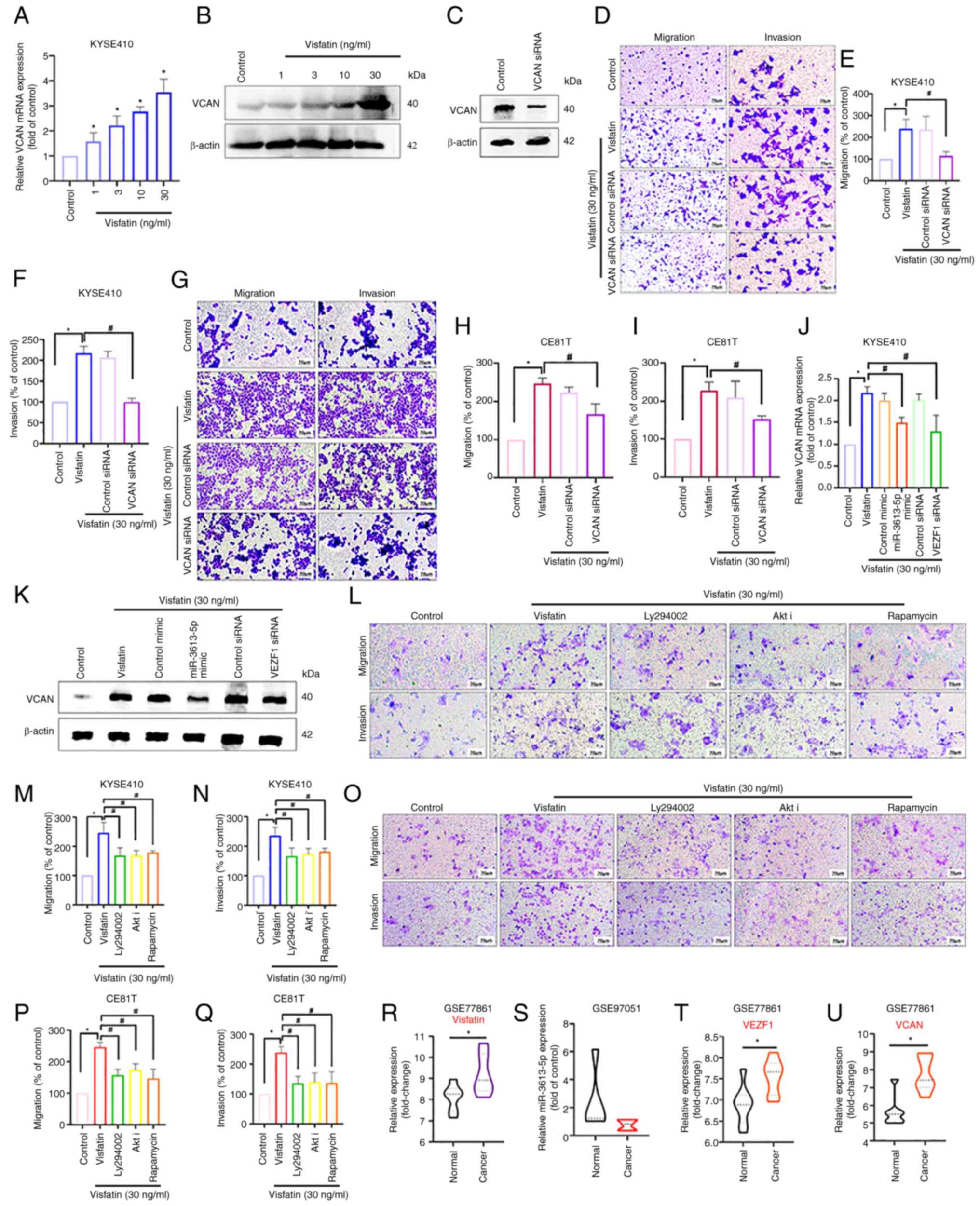

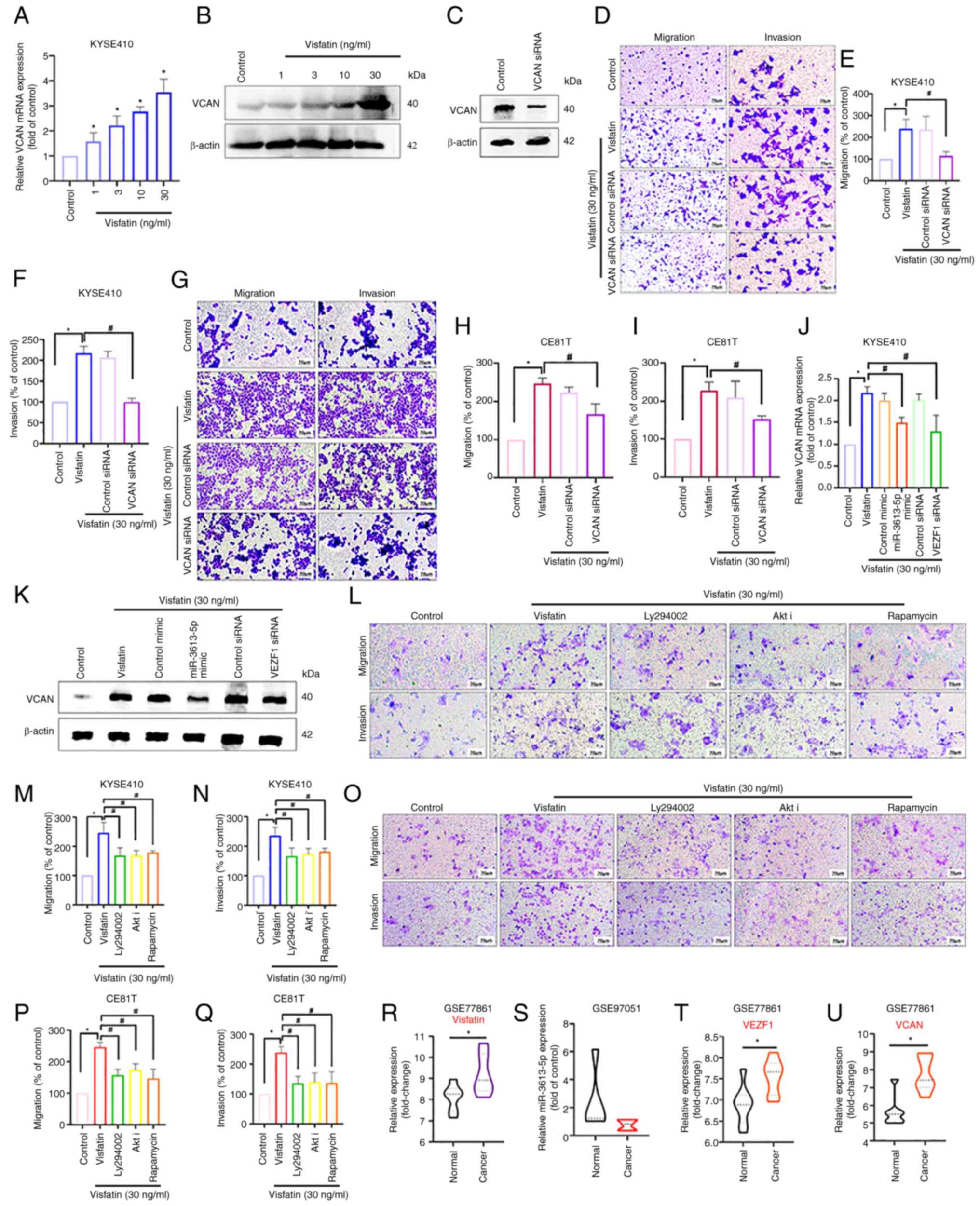

Visfatin promoted the mRNA and protein expression of VCAN (Fig. 6A and B). Transfection with VCAN

siRNA effectively decreased VCAN protein levels, as confirmed by

western blot analysis (Fig. 6C),

and also attenuated visfatin-induced cell motility (Fig. 6D-F); this effect was validated in

CE81T cells (Fig. 6G-I).

miR-3613-5p mimic and VEZF1 siRNA also suppressed visfatin-induced

VCAN expression (Fig. 6J and K),

indicating that the inhibition of miR-3613-5p and the promotion of

VEZF1 occurred upstream of visfatin-induced VCAN expression and

cell motility. Mechanically, visfatin inhibits miR-1264 and

promotes platelet derived growth factor C (PDGF-C) synthesis

through activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway (19). To elucidate the molecular mechanism,

the present study examined the role of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in

visfatin-mediated ESCC migration and invasion Transwell assay

results indicate that treatment with PI3K (Ly294002), AKTi and mTOR

(rapamycin) pathway inhibitors effectively reversed the migration

and invasion effects induced by visfatin, confirming the

involvement of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling axis in visfatin-driven

migration and invasion (Fig. 6L-Q).

To explore the clinical relevance of visfatin-related genes,

GSE77861 dataset was analyzed to compare gene expression between

normal and esophageal cancer tissue. Visfatin (Fig. 6R), VEZF1 (Fig. 6T) and VCAN (Fig. 6U) were significantly upregulated in

esophageal cancer tissues compared with normal controls

(P<0.05). In addition, analysis of the GSE97051 dataset showed

that miR-3613-5p expression was slightly decreased in cancerous

tissue compared with normal samples (Fig. 6S). Together, these findings support

the potential involvement of the visfatin/miR-3613-5p/VEZF1/VCAN

axis in the progression of esophageal cancer.

| Figure 5.VCAN is highly expressed in patients

with esophageal cancer. (A) Spearman correlation analysis from

TCGA. (B) A total of 13 genes correlated with VEZF1 and were

associated with cell adhesion functions. (C) Gene levels in

patients with esophageal cancer retrieved from the GSE161533 and

TCGA database. (D) Kaplan-Meier analysis of VCAN level in normal

and cancer stage in ESCC *P<0.05. VCAN, Versican; VEZF1,

Vascular Endothelial Zinc Finger 1; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas;

FC, Fold Change; PLXNC1, Plexin C1; ERBIN, interacting protein;

CLDN, claudin; ARAHGAP, Rho GTPase-activating protein 5; RGMB,

Repulsive Guidance Molecule BMP Co-Receptor B; ITGBL, Integrin

subunit beta 1; PTPRK, Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Receptor Type

Kappa; DDR, DNA Damage Response; PARD, Par-3 family cell polarity

regulator; SPECC1L, sperm antigen with calponin homology and

coiled-coil domains 1 like; CDON, Cell Adhesion Associated,

Oncogene Regulated; PTPRT, protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor

type, T. |

| Figure 6.VCAN is involved in visfatin-induced

esophageal cancer migration. Cells were stimulated with visfatin

and VCAN expression was examined using (A) RT-qPCR and (B) western

blot analysis. (C) VCAN siRNA transfection efficiency confirmed by

western blot analysis. (D) KYSE410 cells were transfected with or

without VCAN siRNA followed by visfatin treatment and cell (E)

migration and (F) invasion were examined. (G) CE81T cells were

transfected with VCAN siRNA and treated with visfatin; cell (H)

migration and (I) invasion were examined. Cells were transfected

with miR-3613-5p mimic or VEZF-1 siRNA and treated with visfatin;

VCAN expression was examined using (J) RT-qPCR and (K) western

blotting. (L) KYSE 410 cells treated with PI3K (Ly294002), AKT and

mTOR (rapamycin) inhibitors and visfatin treatment to assess

effects on (M) migration and (N) invasion. (O) CE81T cells treated

with PI3K (Ly294002), AKT and mTOR (rapamycin) inhibitors and

visfatin treatment were assayed for (P) cell migration and (Q)

invasion. Gene Expression Omnibus dataset GSE77861 shows

significantly increased mRNA expression of (R) NAMPT, (S)

miR-3613-5p, (T) VEZF1 and (U) VCAN in esophageal cancer compared

with normal tissue. *P<0.05 vs. control; #P<0.05

vs. visfatin. miR, microRNA; VCAN, versican; RT-q, Reverse

Transcriptase Quantitative; si, small interfering; VEZf-1, Vascular

Endothelial Zinc Finger 1; NAMPT, Nicotinamide

phosphoribosyltransferase; Akti, Akt inhibitor. |

Discussion

Esophageal cancer is a relatively prevalent

malignancy worldwide, marked by a poor prognosis and a strong

tendency for metastasis. It is the eighth most commonly diagnosed

cancer and the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths

globally. Notably, over 80% of all cases and fatalities are

reported in developing countries. In the United States alone, the

National Cancer Institute estimated approximately 18,000 new cases

and over 15,000 deaths due to esophageal cancer in 2013 (32). The ESCC subtype, which accounts for

almost 90% of esophageal malignancies in Asia, has a high mortality

rate and poor prognosis (33).

Despite progress in detection and treatment, the 5-year survival

rate of patients with esophageal cancer is relatively low (34). The high mortality rate from

esophageal cancer may be decreased with improved treatment

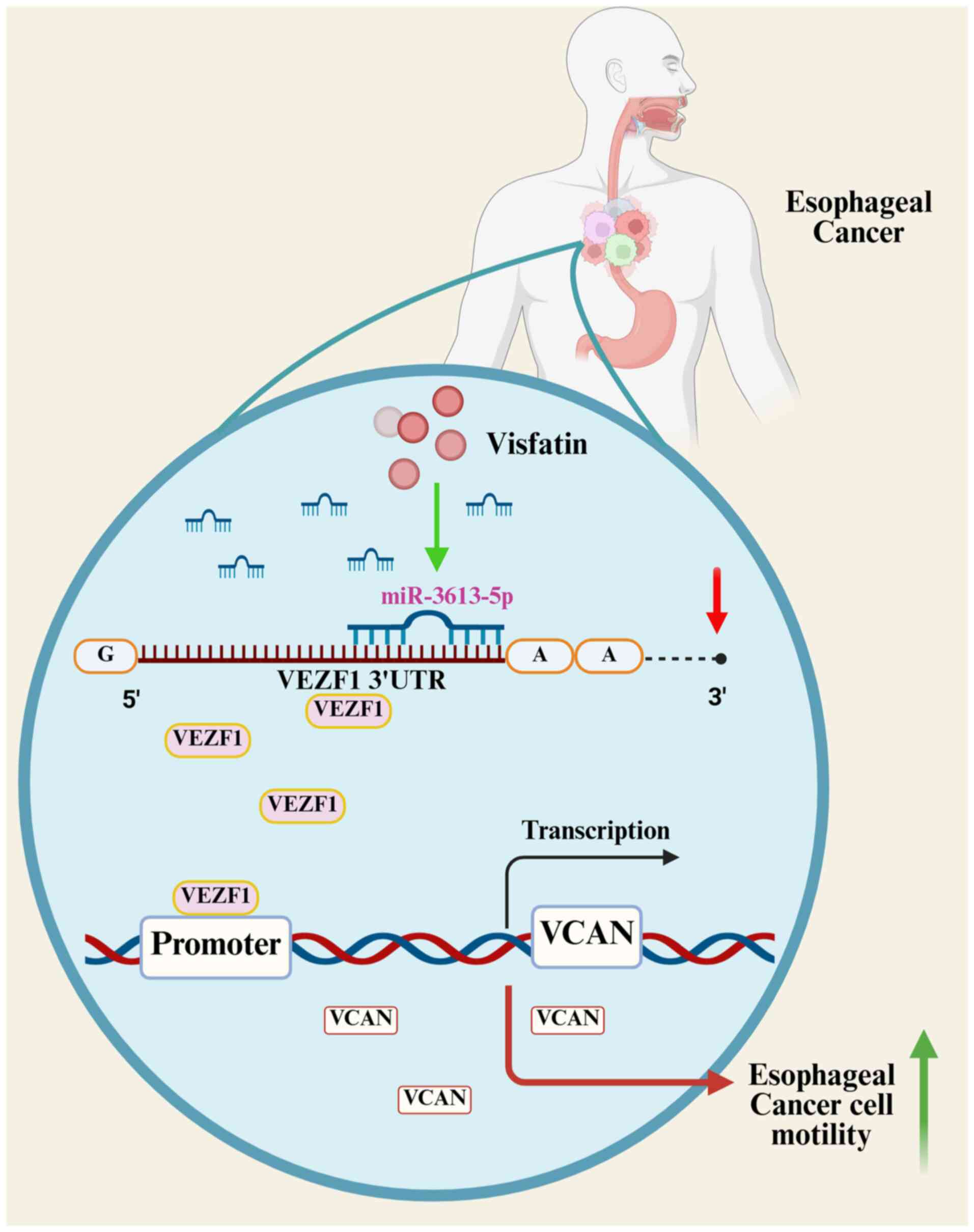

approaches (35). The present study

demonstrated that the levels of visfatin were associated with

metastasis in patients with esophageal cancer. The present study

showed that inhibition of miR-3613-5p and the promotion of the

VEZF1/VCAN axis mediated visfatin-facilitated esophageal cancer

cell motility (Fig. 7). The present

study also demonstrated the expression of visfatin, VEZF1, and VCAN

in normal and cancer samples from the GEO database. However, a

limitation is the lack of experimental validation using clinical

samples from patients with ESCC, underscoring the need for further

investigation.

Adipocytokines are associated with development,

spread, recurrence and metastasis of numerous types of malignancy

(36). Lower resistin mRNA levels

are found in ESCC samples and blood compared with normal esophageal

samples (37), Patients with ESCC

have lower adiponectin levels compared with controls (38). Additionally, a significant

association has been found between leptin levels and advanced tumor

stage in ESCC, as well as lymph node involvement (39). Specifically, visfatin serves a key

role in inflammation and cancer. Additionally, visfatin promotes

the metastasis of chondrosarcoma (40). Visfatin is associated with a higher

disease stage in ESCC tissue and promotes lymphangiogenesis. Our

previous study demonstrated that visfatin is highly expressed in

ESCC N1 and N2 stage samples compared with N0 and is associated

with lymph node metastasis (3). In

the present study, Transwell migration and Matrigel invasion assays

revealed that visfatin facilitated the migration and invasion of

esophageal cancer cells. To the best of our knowledge, the present

study is the first to demonstrate that visfatin promotes cell

motility in esophageal cancer.

At the post-transcriptional level, small, non-coding

miRNAs are key for regulating gene expression (41). This regulation controls

physiological and pathological processes, including cancer, by

destroying or inhibiting the translation of target mRNAs (42–44). A

promising treatment strategy to combat tumor metastasis is to alter

miRNA expression through pharmacological intervention, which may be

utilized to inhibit cancer cells from migrating (45,46).

In the present study, the miRNA sequencing analysis revealed that

miR-3613-5p was the most downregulated miRNA following the use of

visfatin. Subsequent experiments demonstrated that visfatin reduced

miR-3613-5p expression and introducing a miR-3613-5p mimic into

esophageal cancer cells reversed visfatin-induced cell motility.

These findings indicated that visfatin promoted esophageal cancer

cell migration and invasion by suppressing miR-3613-5p synthesis.

Additionally, visfatin-induced inhibition of miR-1264 promotes

PDGF-C synthesis via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (19). In the present study, Transwell

assays demonstrated that inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

effectively reversed the metastatic effects induced by visfatin. To

the best of our knowledge, however, there is no direct evidence

linking the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway to the regulation of miR-3613-5p.

Absence of direct evidence limits understanding of the upstream

regulatory network controlling miR-3613-5p expression in response

to visfatin stimulation. Whether the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is

involved in visfatin-mediated regulation of miR-3613-5p expression

needs further investigation.

With its six-type zinc finger motifs, poly glutamine

domain and proline-rich region, VEZF1 is a potential zinc finger

transcription factor that is key for angiogenesis (47). Initially, VEZF1 expression was found

in both the embryo proper and the mesodermal components of the

extraembryonic mesoderm (48).

Subsequently, endothelial cells that emerge during angiogenesis

were found to express VEZF1 (48).

By targeting downstream genes, such as metallothionein 1 and

stathmin, VEZF1 controls different phases of angiogenesis (49). VEZF1 transcriptional activity also

controls the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma (50). According to four publicly accessible

miRNA databases, miR-3613-5p targets seven possible candidates, and

patients with esophageal cancer have significantly higher levels of

VEZF1. Visfatin-induced cell migration and invasion were reduced by

VEZF1 siRNA, suggesting that VEZF1 mediated the motility of

esophageal cancer. The present study also identified VCAN as a

downstream molecule of VEZF1. Therefore, the VEZF1/VCAN axis may

mediates visfatin-induced esophageal cancer cell migration.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

visfatin facilitated the migration and invasion of esophageal

cancer cells. The inhibition of miR-3613-5p and the promotion of

the VEZF1/VCAN axis mediated visfatin-induced esophageal cancer

cell motility.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Science and

Technology Council (grant nos. 113-2320-B-039-049-MY3,

113-2320-B-371-002- and 112-2314-B-039-018-MY3), China Medical

University (grant no. CMU111-ASIA-05) and China Medical University

Hospital (grant nos. DMR-114-014, DMR-114-021, DMR-113-008 and

DMR-114-069).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE298998 or

at the following URL: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE298998).

Authors' contributions

CLH, CHT and PIL wrote the manuscript. SSG, JHG,

CLL, YHC and CLH performed experiments and analyzed data. HCT, PIL,

YHC, MYL and CHT analyzed data. HCT, SSG and CHT edited the

manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. CLH, MYL and CHT confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global Cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhang HZ, Jin GF and Shen HB:

Epidemiologic differences in esophageal cancer between Asian and

Western populations. Chin J Cancer. 31:281–286. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Huang CL, Achudhan D, Liu PI, Lin YY, Liu

SC, Guo JH, Liu CL, Wu CY, Wang SW and Tang CH: Visfatin

upregulates VEGF-C expression and lymphangiogenesis in esophageal

cancer by activating MEK1/2-ERK and NF-κB signaling. Aging (Albany

NY). 15:4774–4793. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Shai SE, Lai YL, Tang HW and Hung SC:

Treatment of trivial esophageal cancer with huge devastating airway

obstruction via the use of a modified emergency tracheostomy under

local anesthesia. Asian J Surg. 43:1182–1185. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Quint LE, Hepburn LM, Francis IR, Whyte RI

and Orringer MB: Incidence and distribution of distant metastases

from newly diagnosed esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 76:1120–1125.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT,

Hernando-Monge E, Mu D, Goodson S, Powers S, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe

SW, Hannon GJ and Hammond SM: A microRNA polycistron as a potential

human oncogene. Nature. 435:828–833. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Achudhan D, Lai YL, Lin YY, Huang YL, Tsai

CH, Ho TL, Ko CY, Fong YC, Huang CC and Tang CH: CXCL13 promotes

TNF-α synthesis in rheumatoid arthritis through activating ERK/p38

pathway and inhibiting miR-330-3p generation. Biochem Pharmacol.

221:1160372024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chang TK, Ho TL, Lin YY, Thuong LHH, Lai

KY, Tsai CH, Liaw CC and Tang C: Ugonin P facilitates chondrogenic

properties in chondrocytes by inhibiting miR-3074-5p production:

Implications for the treatment of arthritic disorders. Int J Biol

Sci. 21:1378–1390. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tran NB, Chang TK, Chi NDP, Lai KY, Chen

HT, Fong YC, Liaw CC and Tang CH: Ugonin inhibits chondrosarcoma

metastasis through suppressing cathepsin V via promoting

miR-4799-5p expression. Int J Biol Sci. 21:1144–1157. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Thuong LHH, Huang CL, Fong YC, Liu CL, Guo

JH, Wu CY, Liu PI and Tang CH: Bone sialoprotein facilitates

anoikis resistance in lung cancer by inhibiting miR-150-5p

expression. J Cell Mol Med. 28:e701552024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lin LW, Lin TH, Swain S, Fang JK, Guo JH,

Yang SF and Tang CH: Melatonin inhibits ET-1 production to break

crosstalk between prostate cancer and bone cells: Implication for

osteoblastic bone metastasis treatment. J Pineal Res.

76:e700002024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Inui M, Martello G and Piccolo S: MicroRNA

control of signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 11:252–263.

2010. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Annett S, Moore G and Robson T: Obesity

and cancer metastasis: Molecular and translational perspectives.

Cancers (Basel). 12:37982020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lin CJ, Chang YC, Hsu HY, Tsai MC, Hsu LY,

Hwang LC, Chien KL and Yeh TL: Metabolically healthy

overweight/obesity and cancer risk: A representative cohort study

in Taiwan. Obes Res Clin Pract. 15:564–569. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ and Walsh K:

Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol.

11:85–97. 2011. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Rana MN and Neeland IJ: Adipose tissue

inflammation and cardiovascular disease: An update. Curr Diab Rep.

22:27–37. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

de Liyis BG, Nolan J and Maharjana MA:

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1-bound extracellular vesicle as

novel therapy for osteoarthritis. Biomedicine (Taipei). 12:1–9.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Akrida I and Papadaki H: Adipokines and

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cancer. Mol Cell

Biochem. 478:2419–2433. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Song CY, Chang SL, Lin CY, Tsai CH, Yang

SY, Fong YC, Huang YW, Wang SW, Chen WC and Tang CH:

Visfatin-Induced inhibition of miR-1264 facilitates PDGF-C

synthesis in chondrosarcoma cells and enhances endothelial

progenitor cell angiogenesis. Cells. 11:34702022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cymbaluk-Płoska A, Chudecka-Głaz A,

Pius-Sadowska E, Sompolska-Rzechuła A, Machaliński B and Menkiszak

J: Circulating serum level of visfatin in patients with endometrial

cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2018:85761792018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hu SL, Liu SC, Lin CY, Fong YC, Wang SS,

Chen LC, Yang SF and Tang CH: Genetic associations of visfatin

polymorphisms with clinicopathologic characteristics of prostate

cancer in Taiwanese males. Int J Med Sci. 21:2494–2501. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lin CY, Law YY, Yu CC, Wu YY, Hou SM, Chen

WL, Yang SY, Tsai CH, Lo YS, Fong YC and Tang CH: NAMPT enhances

LOX expression and promotes metastasis in human chondrosarcoma

cells by inhibiting miR-26b-5p synthesis. J Cell Physiol.

239:e313452024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chang AC, Chen PC, Lin YF, Su CM, Liu JF,

Lin TH, Chuang SM and Tang CH: Osteoblast-secreted WISP-1 promotes

adherence of prostate cancer cells to bone via the VCAM-1/integrin

α4β1 system. Cancer Lett. 426:47–56. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Chang YH, Huang YL, Tsai HC, Chang AC, Ko

CY, Fong YC and Tang CH: Chemokine ligand 2 promotes migration in

osteosarcoma by regulating the miR-3659/MMP-3 axis. Biomedicines.

11:27682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lee HP, Chen PC, Wang SW, Fong YC, Tsai

CH, Tsai FJ, Chung JG, Huang CY, Yang JS, Hsu YM, et al: Plumbagin

suppresses endothelial progenitor cell-related angiogenesis in

vitro and in vivo. J Funct Foods. 52:537–544. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Lee HP, Wang SW, Wu YC, Lin LW, Tsai FJ,

Yang JS, Li TM and Tang CH: Soya-cerebroside inhibits

VEGF-facilitated angiogenesis in endothelial progenitor cells. Food

and Agricultural Immunology. 31:193–204. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lee KT, Su CH, Liu SC, Chen BC, Chang JW,

Tsai CH, Huang WC, Hsu CJ, Chen WC, Wu YC and Tang C:

Cordycerebroside A inhibits ICAM-1-dependent M1 monocyte adhesion

to osteoarthritis synovial fibroblasts. J Food Biochem.

46:e141082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Liu SC, Tsai CH, Wu TY, Tsai CH, Tsai FJ,

Chung JG, Huang CY, Yang JS, Hsu YM, Yin MC, et al:

Soya-cerebroside reduces IL-1β-induced MMP-1 production in

chondrocytes and inhibits cartilage degradation: Implications for

the treatment of osteoarthritis. Food and Agricultural Immunology.

30:620–632. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Song CY, Wu CY, Lin CY, Tsai CH, Chen HT,

Fong YC, Chen LC and Tang CH: The stimulation of exosome generation

by visfatin polarizes M2 macrophages and enhances the motility of

chondrosarcoma. Environ Toxicol. 39:3790–3798. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

He Z, Ji Y, Yuan Y, Liang T, Liu C, Jiao

Y, Chen Y, Yang Y, Han L, Hu Y and Cong X: Uncovering the role of

microRNAs in esophageal cancer: From pathogenesis to clinical

applications. Front Pharmacol. 16:15325582025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Napier KJ, Scheerer M and Misra S:

Esophageal cancer: A review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, staging

workup and treatment modalities. World J Gastrointest Oncol.

6:112–120. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li D, Zhang L, Liu Y, Sun H, Onwuka JU,

Zhao Z, Tian W, Xu J, Zhao Y and Xu H: Specific DNA methylation

markers in the diagnosis and prognosis of esophageal cancer. Aging

(Albany NY). 11:11640–11658. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang L, Han H, Wang Z, Shi L, Yang M and

Qin Y: Targeting the microenvironment in esophageal cancer. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 9:6849662021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

He S, Xu J, Liu X and Zhen Y: Advances and

challenges in the treatment of esophageal cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B.

11:3379–3392. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kim JW, Kim JH and Lee YJ: The role of

adipokines in tumor progression and its association with obesity.

Biomedicines. 12:972024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Hung AC, Wang YY, Lee KT, Chiang HH, Chen

YK, Du JK, Chen CM, Chen MY, Chen KJ, Hu SC and Yuan SF: Reduced

tissue and serum resistin expression as a clinical marker for

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 22:7742021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dalamaga M, Diakopoulos KN and Mantzoros

CS: The role of adiponectin in cancer: A review of current

evidence. Endocr Rev. 33:547–594. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ray A and Cleary MP: The potential role of

leptin in tumor invasion and metastasis. Cytokine Growth Factor

Rev. 38:80–97. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Hung SY, Lin CY, Yu CC, Chen HT, Lien MY,

Huang YW, Fong YC, Liu JF, Wang SW, Chen WC and Tang CH: Visfatin

promotes the metastatic potential of chondrosarcoma cells by

stimulating AP-1-dependent MMP-2 production in the MAPK pathway.

Int J Mol Sci. 22:86422021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Tehrani SS, Zaboli E, Sadeghi F, Khafri S,

Karimian A, Rafie M and Parsian H: MicroRNA-26a-5p as a potential

predictive factor for determining the effectiveness of trastuzumab

therapy in HER-2 positive breast cancer patients. Biomedicine

(Taipei). 11:30–39. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kanwal R, Plaga AR, Liu X, Shukla GC and

Gupta S: MicroRNAs in prostate cancer: Functional role as

biomarkers. Cancer Lett. 407:9–20. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kong YW, Ferland-McCollough D, Jackson TJ

and Bushell M: microRNAs in cancer management. Lancet Oncol.

13:e249–e258. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

He L and Hannon GJ: MicroRNAs: Small RNAs

with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 5:522–531. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Tsai HC, Lai YY, Hsu HC, Fong YC, Lien MY

and Tang CH: CCL4 stimulates cell migration in human osteosarcoma

via the mir-3927-3p/Integrin αvβ3 axis. Int J Mol Sci.

22:127372021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Tzeng HE, Lin SL, Thadevoos LA, Lien MY,

Yang WH, Ko CY, Lin CY, Huang YW, Liu JF, Fong YC, et al: Nerve

growth factor promotes lysyl oxidase-dependent chondrosarcoma cell

metastasis by suppressing miR-149-5p synthesis. Cell Death Dis.

12:11012021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Bruderer M, Alini M and Stoddart MJ: Role

of HOXA9 and VEZF1 in endothelial biology. J Vasc Res. 50:265–278.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Xiong JW, Leahy A, Lee HH and Stuhlmann H:

Vezf1: A Zn finger transcription factor restricted to endothelial

cells and their precursors. Dev Biol. 206:123–141. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Miyashita H, Kanemura M, Yamazaki T, Abe M

and Sato Y: Vascular endothelial zinc finger 1 is involved in the

regulation of angiogenesis: Possible contribution of stathmin/OP18

as a downstream target gene. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

24:878–884. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Shi X, Zhao P and Zhao G: VEZF1,

destabilized by STUB1, affects cellular growth and metastasis of

hepatocellular carcinoma by transcriptionally regulating PAQR4.

Cancer Gene Ther. 30:256–266. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|