Introduction

Gynecological malignancies represent a major threat

to women's health. According to data from the International Agency

for Research on Cancer in 2020, there are ~1.33 million new cases

and 540,000 deaths related to gynecological cancers worldwide each

year (1,2). Cervical, endometrial and ovarian

cancers are the three most common malignancies of the female

reproductive system and, together with breast cancer, constitute a

substantial global health burden for women, accounting for nearly

one-third of all cancer-related incidence and mortality among

female patients (3). Despite

significant progress in screening, diagnosis and treatment, these

malignancies remain leading causes of female cancer-related deaths

due to their biological heterogeneity, late-stage diagnosis and

therapeutic resistance (4,5). Breast cancer is the most prevalent

malignancy in women. Molecular subtyping-such as

estrogen/progesterone receptor (ER/PR)-positive, HER2-enriched, and

triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)-has led to breakthroughs in

targeted therapies, including CDK4/6 inhibitors and anti-HER2

agents (6). However, the management

of metastatic disease and the emergence of drug resistance continue

to pose major challenges. Among gynecological cancers, ovarian

cancer has the highest mortality rate due to its asymptomatic

nature and frequent diagnosis at an advanced stage (7). Recent advances, such as PARP

inhibitors for BRCA-mutated tumors and immunotherapy, have

redefined treatment strategies, yet the high recurrence rate

underscores the urgent need for novel biomarkers (8). Endometrial cancer has traditionally

been associated with obesity and metabolic disorders, and molecular

subtypes identified through The Cancer Genome Atlas-including

POLE-ultra-mutated and microsatellite instability-high types-have

provided a basis for risk stratification and immunotherapy

application (9). While cervical

cancer is largely preventable through HPV vaccination and early

screening, it remains prevalent in low-resource regions. Emerging

therapies, such as PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and therapeutic vaccines,

offer new hope for patients with advanced disease (10).

Currently, surgical resection, radiotherapy,

chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy are employed in

the treatment of gynecological malignancies. However, the incidence

and mortality rates of these cancers continue to rise annually

(11,12). Despite advances in modern medicine,

therapeutic efficacy remains limited, and challenges such as drug

resistance and adverse side effects persist (13). Increasing attention has therefore

been directed toward bioactive compounds from traditional Chinese

medicine as complementary or alternative therapeutic strategies in

breast and gynecological cancers (14). Natural products such as curcumin,

quercetin and tanshinone have demonstrated anti-proliferative,

pro-apoptotic, anti-metastatic and chemo-sensitizing activities via

regulation of multiple signaling pathways, including PI3K/AKT,

NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin (15–17).

Among them, ursolic acid (UA), a pentacyclic triterpenoid widely

distributed in vegetables, fruits and medicinal herbs (18), has attracted increasing interest due

to its potent anticancer properties and relatively low toxicity. UA

exerts broad antitumor effects by modulating diverse cellular

processes, including proliferation, apoptosis, metastasis and

chemoresistance, while sparing normal cells (19,20).

Furthermore, UA exhibits neuroprotective effects such as analgesic,

anxiolytic, antidepressant and memory-enhancing properties,

underscoring its vast pharmacological potential and clinical

applicability (21,22). Recent studies suggest that UA holds

significant therapeutic potential in gynecological and breast

cancers, particularly through regulation of key oncogenic pathways

and enhancement of conventional treatment efficacy (23–25).

The present review summarizes current progress on the anticancer

mechanisms of UA in these malignancies, with emphasis on molecular

targets, the development of UA derivatives, and novel formulations

aimed at improving its bioavailability and clinical

applicability.

Structural properties, natural origins and

extraction methods of UA

UA, with the molecular formula

C30H48O3, is a pentacyclic

triterpenoid compound (26). It

exists either in its free acid form or as the aglycone component of

triterpenoid saponins, and is widely distributed in natural plants

such as Plantago asiatica, Cornus officinalis, Crataegus

pinnatifida, Hedyotis diffusa, Prunella vulgaris, rosemary,

loquat and apples (27). UA is a

structurally complex molecule featuring 10 chiral centers, making

it challenging to synthesize via conventional chemical methods. At

present, extraction from natural plant sources remains the primary

approach for obtaining UA.

Pure UA appears as white crystals that are soluble

in methanol, ethanol and butanol, sparingly soluble in ether and

chloroform, and insoluble in water and petroleum ether (28). Traditional extraction

techniques-such as Soxhlet extraction, pulverization extraction and

reflux extraction-often suffer from limitations including low

purity and extended processing time (29). With technological advancements,

novel extraction methods such as ultrasonic-assisted extraction,

supercritical fluid extraction and semi-bionic extraction have

gained attention (30). Among

these, the semi-bionic approach, which simulates gastrointestinal

digestion and absorption based on biopharmaceutics theory, has

shown improved efficiency in isolating target compounds. Studies

have demonstrated that parameters such as the solvent-to-material

ratio, ethanol concentration, ultrasonic duration and power

significantly influence the yield of UA during ultrasonic-assisted

extraction (21,31,32).

Due to its strong lipophilicity, UA is optimally extracted using

low-polarity solvents such as ethanol (33). Furthermore, with continued research,

the pharmacological potential of UA derivatives has been

increasingly recognized. Structural modifications at the C-3 and

C-28 positions have been found to enhance its bioactivity (19,34).

Some derivatives exhibit notable antitumor, antifungal and

antioxidant properties, providing a theoretical foundation and

experimental support for novel drug development (35,36).

Anticancer mechanisms of UA in gynecological

and breast cancers

UA, a natural pentacyclic triterpenoid compound, has

demonstrated broad-spectrum anticancer potential in various

gynecological malignancies, including ovarian, endometrial and

cervical cancers, as well as in breast cancer. Its multifaceted

mechanisms of action include induction of apoptosis, inhibition of

cell proliferation and metastasis, regulation of metabolic

reprogramming, suppression of cancer stem cell (CSC) properties,

and enhancement of chemosensitivity (Table SI).

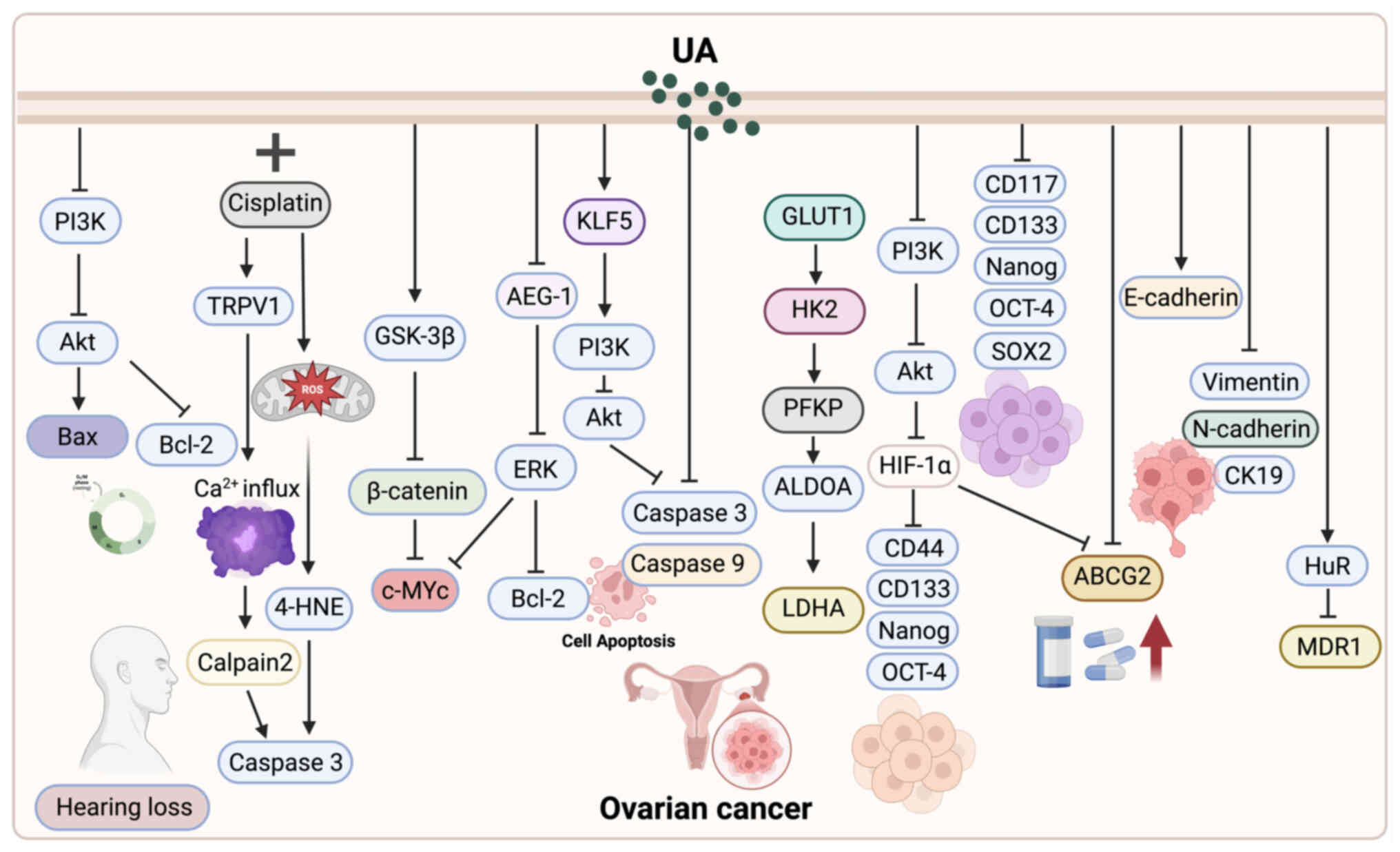

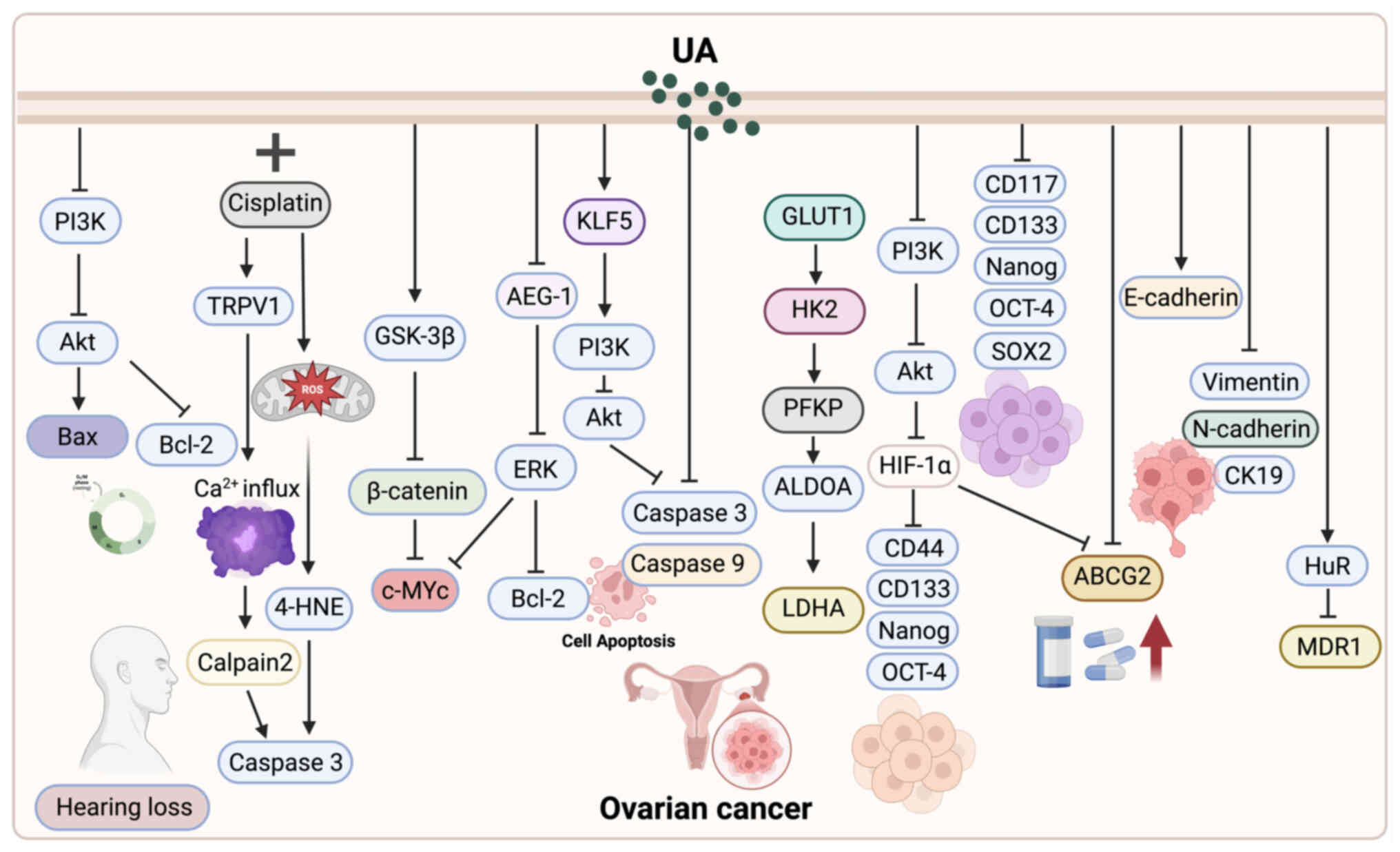

UA and ovarian cancer

Induction of tumor cell apoptosis

UA can effectively inhibit the proliferation of

tumor cells by inducing apoptosis and causing cell cycle arrest.

Song et al (23)

systematically elucidated the pro-apoptotic mechanisms of UA and

found that it induces a classical apoptotic process in SKOV3

ovarian cancer cells, activates the caspase cascade, suppresses the

expression of oncogenic proteins such as c-Myc, and enhances its

antitumor effects by activating the GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling

pathway. Subsequently, Lin and Ye (37) further confirmed the inhibitory

effects of UA on ovarian cancer cells, demonstrating that it

suppresses cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner with high

selectivity. The underlying mechanisms include the induction of

apoptosis, G2/M phase cell cycle arrest, elevation of intracellular

reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, modulation of the Bax/Bcl-2

ratio, and inhibition of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

Regulation of metabolic reprogramming

Beyond apoptosis, UA also disrupts ovarian cancer

metabolism. Glycolysis serves as a critical energy metabolism

pathway in ovarian cancer cells, and its dysregulation is closely

associated with tumor progression and chemoresistance (38). RNA sequencing and a series of in

vitro and in vivo experiments have demonstrated that UA

significantly inhibits ovarian cancer cell proliferation, induces

apoptosis, and reduces glycolytic activity (39). Mechanistically, UA binds to and

inhibits the transcription factor KLF5, thereby blocking the

transcriptional activation of the downstream PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway. This dual inhibition of glycolysis and cancer cell

survival highlights the therapeutic potential of UA in targeting

metabolic vulnerabilities in ovarian cancer.

Enhancing efficacy and reducing toxicity via

chemotherapy combination

In addition to direct tumor inhibition, UA also

plays an important role in improving chemotherapy outcomes.

Cisplatin (CDDP) is widely used in the treatment of various

cancers; however, its ototoxicity often leads to irreversible

hearing loss (40,41). A study by Di et al (42) demonstrated that UA significantly

alleviates CDDP-induced ototoxic damage and preserves auditory

function by inhibiting the TRPV1/Ca2+/calpain-oxidative

stress signaling pathway. Notably, UA also enhances the antitumor

efficacy of CDDP against ovarian cancer cells, exerting synergistic

and protective effects without compromising its anticancer potency.

Beyond CDDP, ovarian cancer is also prone to developing resistance

to chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin, which remains a

major cause of treatment failure. Li et al (43) established a doxorubicin-resistant

SKOV3-Adr cell model and found that UA markedly increased the

sensitivity of these cells to doxorubicin. Furthermore, UA

synergistically enhanced the efficacy of doxorubicin in both

parental SKOV3 and A2780 cells. Mechanistically, although HuR mRNA

expression levels were comparable between SKOV3 and SKOV3-Adr

cells, HuR protein was predominantly accumulated in the cytoplasm

of resistant cells, where it stabilized MDR1 mRNA and promoted drug

resistance. UA facilitated the translocation of HuR from the

cytoplasm to the nucleus, thereby reducing MDR1 mRNA stability and

downregulating its expression, ultimately restoring sensitivity to

doxorubicin. The present study highlights a novel mechanism by

which UA reverses chemoresistance in ovarian cancer through

post-transcriptional regulation of mRNA stability, underscoring its

potential as an adjuvant to conventional chemotherapy.

Inhibition of CSC traits and drug-resistant

phenotype

In ovarian cancer, CSCs are recognized as key

contributors to tumor recurrence, metastasis and chemoresistance

(44,45). Emerging evidence suggests that UA

can enhance the sensitivity of ovarian cancer CSCs to CDDP,

significantly reversing the stemness and drug-resistant phenotypes

typically induced by the hypoxic tumor microenvironment (TME). This

effect is closely associated with inhibition of the PI3K/Akt

signaling pathway and downregulation of the HIF-1α/ABCG2 axis, with

further therapeutic enhancement observed when combined with HIF-1α

inhibitors (46). Moreover, UA

suppresses the self-renewal and migratory capacities of ovarian

CSCs by downregulating stem cell markers such as CD133 and ALDH1,

as well as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-related factors

including N-cadherin and vimentin. These changes contribute to a

marked improvement in the efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents

(47). Collectively, these findings

highlight the promising potential of UA in targeting CSC-associated

stemness maintenance and overcoming chemoresistance in ovarian

cancer (Fig. 1).

| Figure 1.UA exerts multifaceted antitumor

effects against ovarian cancer. It induces apoptosis and cell cycle

arrest by activating the caspase cascade, modulating the Bax/Bcl-2

ratio, and inhibiting the PI3K/AKT and GSK-3β/β-catenin pathways.

UA also suppresses glycolysis and metabolic reprogramming by

targeting KLF5 and downstream PI3K/AKT signaling. When combined

with chemotherapeutic agents such as cisplatin and doxorubicin, UA

enhances efficacy while reducing toxicity and reversing drug

resistance through regulation of HuR/MDR1 expression. Additionally,

UA targets ovarian cancer stem cells, inhibiting their

self-renewal, migration and stemness via suppression of the

PI3K/AKT and HIF-1α/ABCG2 pathways, and downregulation of CD133,

ALDH1, N-cadherin and vimentin. These mechanisms collectively

highlight UA's therapeutic potential in overcoming chemoresistance

and improving ovarian cancer treatment outcomes. UA, ursolic

acid. |

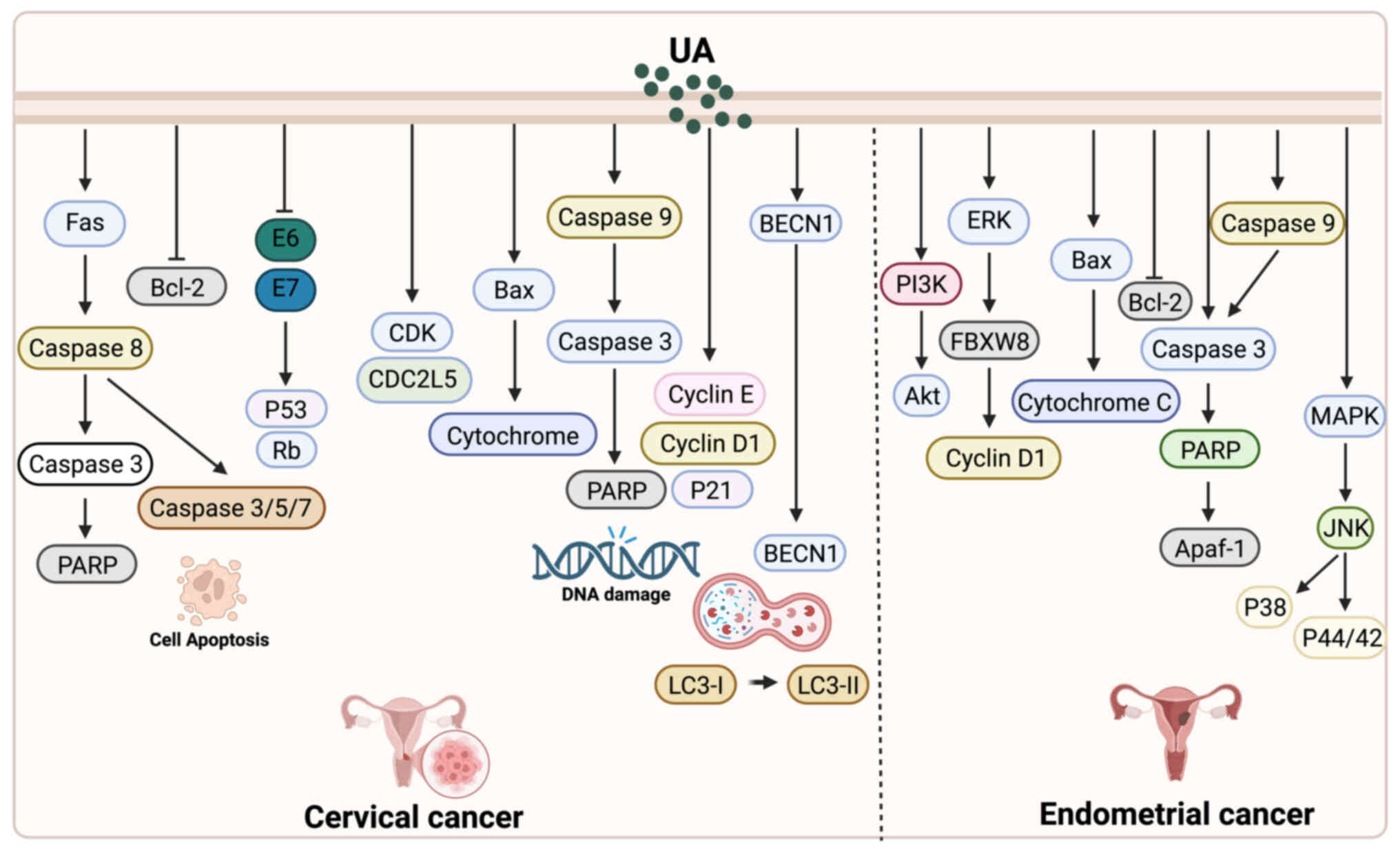

UA and cervical cancer

Antiviral and pro-apoptotic

effects

UA exhibits multiple biological effects in cervical

cancer cells, with particularly notable advantages in antiviral

activity and apoptosis induction. Using proteomic techniques

including 2DE/MALDI-TOF-MS and SELDI-TOF-MS, Yim et al

(25) analyzed HeLa cells treated

with UA and identified significant alterations in the expression of

25 proteins, most of which were associated with apoptotic

processes. Additionally, eight distinct peptide peaks were

observed. In a subsequent study, Yim et al (48) further demonstrated that UA exerts

potent antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic effects specifically in

HPV-positive cervical cancer cells, along with measurable antiviral

activity. Mechanistically, UA was shown to activate the

Fas/caspase-mediated apoptotic pathway and suppress the expression

of HPV oncogenes E6 and E7.

Autophagy-mediated cell death

Beyond apoptosis, UA also induces autophagy as an

alternative form of tumor cell death. Leng et al (49) reported that in mouse cervical cancer

TC-1 cells, UA predominantly induces Atg5-dependent autophagy

rather than classical apoptosis to exert its anticancer effects.

Inhibition of autophagy or knockdown of Atg5 significantly

increased cell viability, suggesting that UA promotes tumor cell

death primarily through autophagic pathways. These findings provide

new insights into autophagy as a complementary mechanism to

apoptosis in UA-mediated cancer therapy. Notably, however, in other

tumor types such as breast cancer, UA-induced autophagy may not

uniformly lead to cell death but instead exert context-dependent,

and occasionally cytoprotective, effects.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress-related

apoptotic mechanism

Another important mechanism by which UA induces

cervical cancer cell death involves the activation of the ER stress

pathway. Guo et al (50)

treated HeLa cells with UA and/or the ER stress inhibitor

4-phenylbutyric acid (4-PBA), and found that UA inhibited cell

viability and induced apoptosis in a time- and dose-dependent

manner. Mechanistically, UA significantly upregulated the

expression of key ER stress markers such as GRP78 and CHOP, while

the addition of 4-PBA partially reversed its pro-apoptotic

effects.

Chemotherapy synergistic effect

In addition to its direct anticancer actions, UA

enhances the efficacy of conventional chemotherapy in cervical

cancer. Li et al (51)

reported that UA increases the sensitivity of cervical cancer cells

to commonly used chemotherapeutic agents such as paclitaxel and

CDDP by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway. Combination

treatment activates the Fas/FasL-caspase-8-BID axis and enhances

the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, selectively promoting

apoptosis in tumor cells without exerting toxicity on normal cells.

Furthermore, co-treatment with UA and CDDP significantly

downregulates the expression of NF-κB p65 and Bcl-2, while

upregulating the levels of Bax, cleaved caspase-3 and PARP cleavage

products, thereby markedly increasing the rate of apoptosis

(Fig. 2).

UA and endometrial cancer

UA has demonstrated multiple antitumor mechanisms in

endometrial cancer research (Fig.

2). Achiwa et al (52)

found that UA downregulates Cyclin D1 expression and interferes

with cell cycle regulation by inhibiting the MAPK-Cyclin D1

signaling pathway and the RING-type E3 ligase SCF complex, thereby

preventing the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of Cyclin D1.

Additionally, UA has been identified to exert its effects via the

CD36 membrane receptor, suggesting a potentially important role in

protein homeostasis and membrane receptor signaling regulation

(53). In terms of apoptosis'

induction, UA inhibits the proliferation of endometrial cancer

cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. It triggers

mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis by activating caspases-3, −8, and

−9, promoting PARP cleavage, inducing DNA fragmentation, and

facilitating cytochrome c release. This is accompanied by

downregulation of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and upregulation

of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax (54). Moreover, UA significantly suppresses

the PI3K-Akt and MAPK signaling pathways (including JNK, p38 and

ERK1/2), reducing the phosphorylation levels of key proteins and

thereby further enhancing its antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic

effects-particularly notable in SNG-II cells (55). Taken together, UA exerts synergistic

effects through multiple signaling pathways to regulate the cell

cycle, inhibit proliferation, and induce apoptosis, highlighting

its therapeutic potential in endometrial cancer.

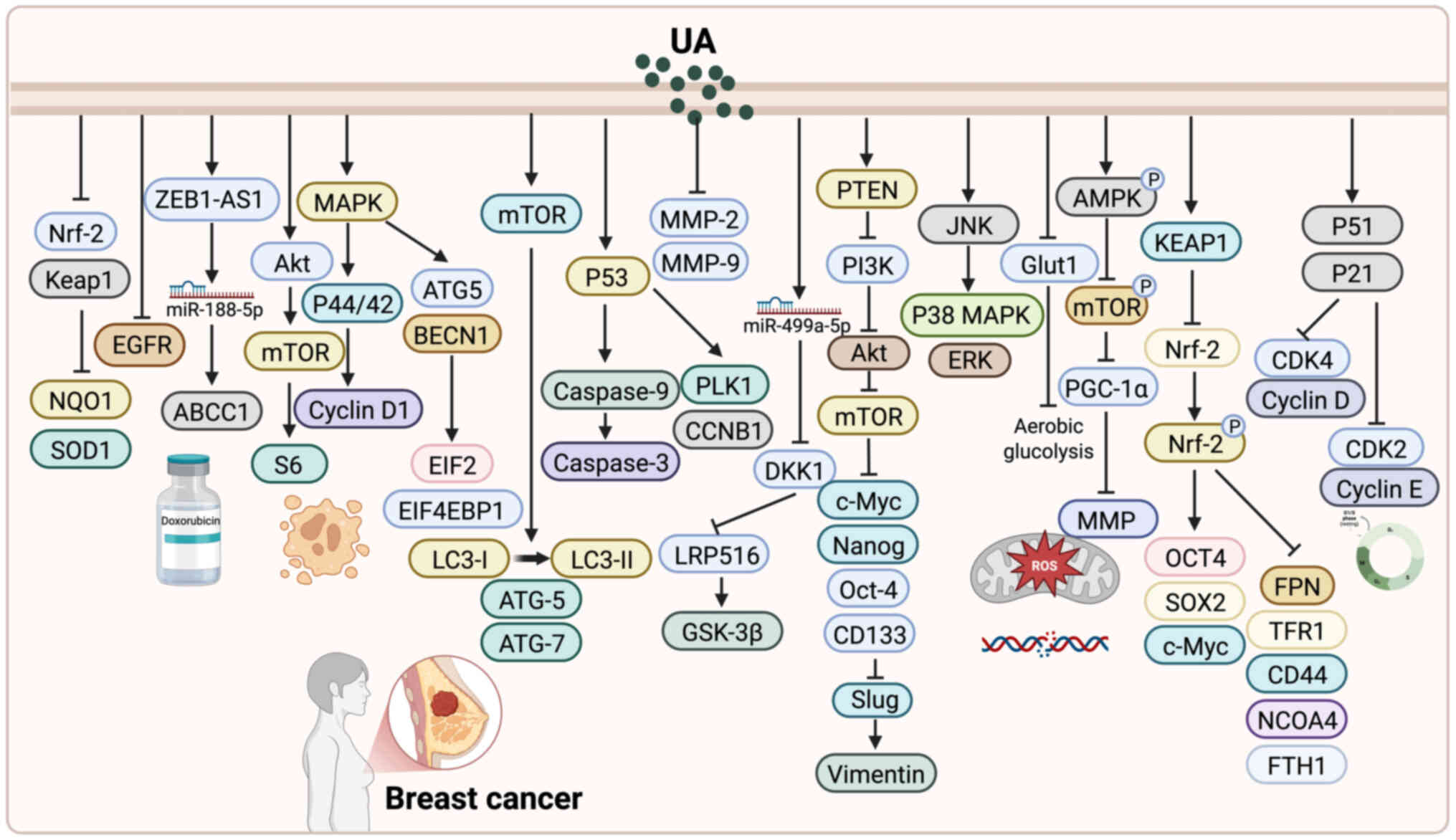

UA and breast cancer

Inhibition of cell proliferation and

induction of apoptosis

One of the most extensively studied effects of UA in

breast cancer is its ability to suppress tumor cell proliferation

and trigger apoptosis. Zhang et al (24) found that UA suppresses the

proliferation of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells by modulating the

Keap1/Nrf2 and EGFR/Nrf2 pathways. It also upregulates Nrf2 and its

downstream target genes such as NQO1 and SOD1 via

post-translational regulation. De Angel et al (56) demonstrated that UA inhibits tumor

growth in breast cancer mouse models, potentially through

modulation of the Akt/mTOR pathway, induction of apoptosis, and

disruption of the cell cycle. Wang et al (57) reported that UA suppresses MCF-7 cell

proliferation by downregulating the transcription factor FoxM1 and

inhibiting the Cyclin D1/CDK4 signaling pathway. Additionally,

Kassi et al (58) observed

that UA induces intrinsic apoptosis via activation of the

mitochondrial pathway and may interact with the glucocorticoid

receptor (GR), suggesting a regulatory effect on GR function.

Mallepogu et al (59) found

that UA induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, and inhibits EMT

by downregulating EMT-related genes such as Snail and Slug.

Manouchehri and Kalafatis (60)

revealed that UA sensitizes triple-negative breast cancer cells to

rhTRAIL-induced apoptosis by upregulating death receptors DR4/5 and

downregulating the anti-apoptotic molecule c-FLIPL. Guo et

al (61) showed that UA

significantly inhibits the proliferation of MCF-7 cells by

suppressing both the RAF/ERK and IKK/NF-κB signaling pathways.

Furthermore, Kim (62) reported

that UA induces cell cycle arrest in breast cancer stem-like cells

by increasing the expression of p53 and p21 and decreasing the

expression of cyclins D and E, as well as CDK4 and CDK2. This is

accompanied by inhibition of the ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling

pathways, contributing to the anti-proliferative effects.

Induction of autophagy and improvement

of metabolism

UA exhibits significant potential in inducing

autophagy and modulating cellular metabolism in breast cancer

cells, but its effects appear to be context-dependent. Regarding

autophagy, Zhao et al (63)

reported that UA upregulates MCL1 via the MAPK1/3 signaling

pathway, which partially counteracts UA-induced apoptosis,

indicating a cytoprotective role of autophagy. By contrast, Gupta

et al (64) demonstrated

that UA, in combination with oleanolic acid, synergistically

induces cytotoxic autophagy, thereby enhancing its antitumor

efficacy. Lewinska et al (65) further showed that UA promotes

oxidative stress and DNA damage by inhibiting the AKT pathway and

activating the AMPK pathway, ultimately triggering both autophagy

and apoptosis, while Fogde et al (66) found that UA induces apoptosis by

disrupting lysosomal function and indirectly suppressing autophagy.

Collectively, these findings suggest that UA-induced autophagy in

breast cancer may function as a ‘double-edged sword’, either

supporting tumor cell survival or promoting cell death depending on

the cellular and signaling context.

In addition to its role in autophagy, UA also

exhibits pronounced metabolic regulatory effects. Guerra et

al (67) revealed that UA

influences key metabolic processes, including glycolysis the

tricarboxylic acid cycle and lipid biosynthesis, in both breast

cancer cells and normal mammary epithelial cells, suggesting a

broader cellular detoxification response. Similarly, Wang et

al (68) demonstrated that UA

activates the SP1/Caveolin-1 pathway to suppress glycolysis and

impair mitochondrial function, leading to mitochondria-dependent

apoptosis. These findings highlight that UA not only reprograms

cancer cell metabolism but also couples metabolic stress with cell

death pathways. Taken together, UA enhances its antitumor activity

in breast cancer through the dual regulation of autophagy and

metabolic reprogramming.

Importantly, the context-dependent nature of

UA-induced autophagy also carries therapeutic implications. When

autophagy functions as a pro-death mechanism, UA may synergize with

apoptosis to maximize anticancer efficacy. Conversely, when

autophagy plays a pro-survival role, it could undermine UA's

therapeutic effects, suggesting that combination with autophagy

inhibitors (for example, chloroquine or 3-methyladenine) may

enhance treatment outcomes. This dualistic role underscores the

necessity of identifying tumor-specific contexts and potential

biomarkers to predict autophagy responses. Future studies should

therefore not only clarify the upstream and downstream signaling

pathways of UA-mediated autophagy but also evaluate combined

therapeutic strategies that either exploit or counteract autophagy,

thereby optimizing the clinical benefit of UA-based

interventions.

Targeting breast CSCs

CSCs play a crucial role in therapy resistance and

disease relapse. Accumulating evidence suggests that UA effectively

targets breast CSCs (BCSCs). Mandal et al (69) found that UA downregulates the

oncogenic microRNA miR-499a-5p and upregulates the Wnt inhibitor

sFRP4, thereby inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and

attenuating the proliferation, migration and stem-like traits of

BCSCs. Similarly, Liao et al (70) demonstrated that UA suppresses the

expression of Argonaute 2, leading to reduced levels of miR-9 and

miR-221, which in turn decreases the expression of stemness markers

and EMT-related proteins. This results in the inhibition of CSC

characteristics, as well as diminished migratory and invasive

capacities. Moreover, Yang et al (71) reported that UA stabilizes KEAP1 and

inhibits NRF2 pathway activation, inducing ferroptosis in

triple-negative BCSCs. This effectively impairs their stemness and

proliferative abilities and has been validated in vivo using

animal models. Collectively, these findings highlight the potential

of UA in targeting BCSCs, offering novel insights into its

application as an anticancer therapeutic agent.

Interfering with metastasis and

invasion

Metastasis is the leading cause of breast cancer

mortality, and UA has been shown to effectively inhibit this

process. Yeh et al (72)

reported that UA, at non-cytotoxic concentrations, markedly

suppresses the migration and invasion of TNBC cells. This effect is

mediated by the downregulation of MMP-2 and u-PA expression, along

with the upregulation of endogenous inhibitors, thereby disrupting

metastatic signaling pathways. Luo et al (73) further confirmed that UA inhibits the

PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, activates GSK and caspase-3, and

downregulates Cyclin D1 and Bcl-2 expression. These molecular

events collectively induce autophagy and apoptosis while

suppressing NF-κB signaling, contributing to both anti-inflammatory

effects and reduced cellular invasiveness. Additionally, Zhang

et al (74) demonstrated

that UA inhibits TNBC cell proliferation, migration and invasion in

a dose-dependent manner by inducing cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis. Together, these studies highlight the potential of UA as

a promising agent for targeting metastasis and invasion in breast

cancer therapy.

Enhancing drug sensitivity and

reversing drug resistance

Chemoresistance is a major obstacle in breast cancer

treatment, and UA has shown significant promise in overcoming this

challenge. Lu et al (75)

found that UA reverses doxorubicin (DOX) resistance in TNBC by

downregulating ZEB1-AS1, thereby releasing its sponging effect on

miR-186-5p and ultimately suppressing ABCC1 expression. Similarly,

Wang et al (76) reported

that UA significantly increases the sensitivity of breast cancer

cells to epirubicin, partly by modulating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR

signaling pathway to enhance chemotherapeutic efficacy. Zong et

al (77) demonstrated that UA,

when co-administered with DOX, markedly increases DOX accumulation

in multidrug-resistant breast cancer cells and promotes its nuclear

translocation, thereby enhancing its antitumor activity. Further

studies by the same group revealed that UA also inhibits the

Erk-VEGF/MMP-9 signaling pathway, thereby reducing cell invasion

and migration while concurrently increasing intracellular DOX

accumulation (78). Luo et

al (79) showed that the

combination of UA and DOX significantly suppresses the

proliferation and migration of drug-resistant breast cancer cells.

This effect is mediated through modulation of the AMPK/mTOR/PGC-1α

axis, resulting in elevated ROS production and inhibition of

aerobic glycolysis, ultimately enhancing DOX efficacy.

Additionally, UA has been shown to reverse paclitaxel resistance in

breast cancer by upregulating miR-149-5p, inhibiting MyD88, and

downregulating the Akt signaling pathway (80). Collectively, these findings provide

robust theoretical and experimental support for the use of UA as an

adjuvant agent in combination chemotherapy to overcome drug

resistance (Fig. 3).

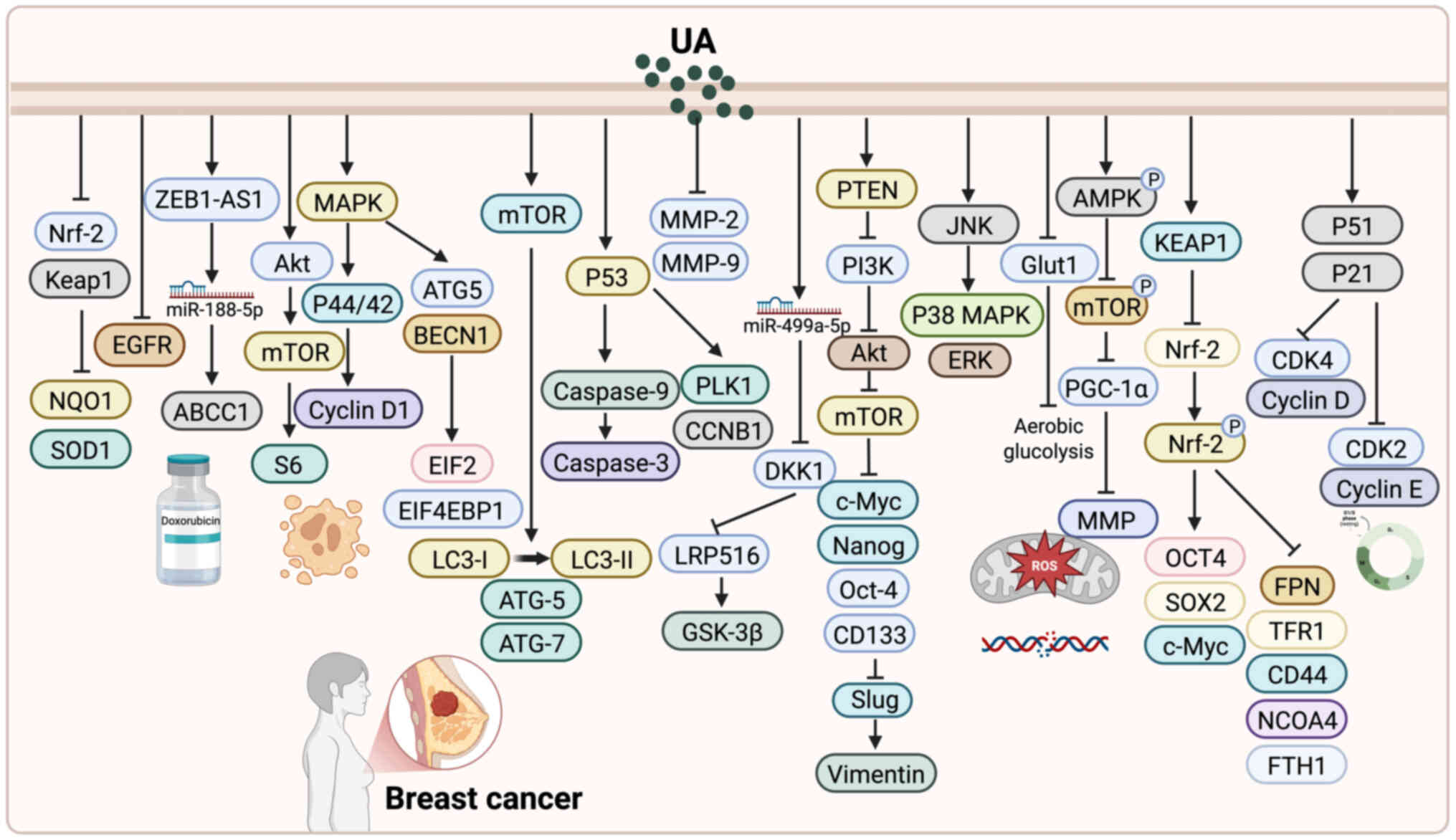

| Figure 3.Antitumor mechanisms of UA in breast

cancer. UA inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in breast

cancer cells via pathways such as Keap1/Nrf2, Akt/mTOR, FoxM1 and

mitochondrial caspase signaling. It induces autophagy and metabolic

disruption through modulation of MAPK, SP1/CAV1, AMPK and AKT

pathways, and regulates glycolysis and mitochondrial function. UA

also targets breast cancer stem cells by suppressing Wnt/β-catenin,

AGO2/miR-9/miR-221 and NRF2 signaling, impairing stemness and

promoting ferroptosis. Additionally, UA inhibits invasion and

metastasis by downregulating MMP-2, u-PA, and PI3K/Akt, while

enhancing autophagy, apoptosis, and anti-inflammatory responses.

UA, ursolic acid. |

Advances in drug delivery strategies and

derivatives of UA

In recent years, various drug delivery strategies

and structural derivatives have been developed to address the

clinical limitations of UA, including poor water solubility, low

bioavailability and limited targeting capacity. In ovarian cancer,

Wang et al (81) designed a

reduction-responsive amphiphilic prodrug, Pt(IV)-UA-PEG, which

self-assembles into nanoparticles [Pt(IV)-UA NPs] with high

drug-loading efficiency. These nanoparticles enable efficient drug

release in the reductive and acidic TME, effectively overcoming

cisplatin resistance and significantly suppressing the

proliferation of resistant ovarian cancer cells. In breast cancer,

Jin et al (82) reported

folic acid-modified chitosan nanoparticles that enhance targeted

uptake and mitochondrial localization, inducing apoptosis via the

mitochondrial pathway. Similarly, Fu et al (83) fabricated UA nanofibers for topical

therapy in advanced breast cancer with skin ulceration, achieving

improved transdermal penetration, inhibition of STAT3 and ERK1/2

signaling, and caspase-3-mediated apoptosis. For TNBC, Sharma et

al (84) developed

enzyme-responsive HA-UA/PTX nanoparticles, which enhanced

CD44-mediated cellular uptake, apoptosis, and tumor suppression

in vivo. Additionally, Liu et al (85) combined UA with a Nectin-4-targeted

oncolytic measles virus, demonstrating synergistic apoptosis

induction and enhanced autophagic flux, while UA-loaded

nanoparticles further reinforced antitumor effects across breast

cancer cell lines. In cervical cancer, Wang et al (86) constructed UA-loaded gold/PLGA

nanocomposites for intranasal delivery, which inhibited

proliferation, invasion and migration, while activating p53 and

caspase signaling to induce apoptosis in vitro and in

vivo.

Beyond delivery systems, structural optimization of

UA has yielded derivatives with improved anticancer activity and

pharmacological properties. The derivative FZU3010 demonstrated

stronger anticancer activity than UA, particularly in renal cancer

and TNBC cells, where it induced G1-phase arrest and apoptosis by

inhibiting STAT3 and upregulating p21/p27 (87,88).

The same group also reported an Asp-UA co-drug that effectively

inhibited breast cancer cell adhesion, migration and invasion,

highlighting its potential against metastasis (89). Pattnaik et al (90) synthesized novel UA derivatives with

selective activity against MDA-MB-231 cells, among which compound

17 showed superior efficacy compared with doxorubicin. UA232,

another optimized derivative, inhibited breast and cervical cancer

cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, ER

stress and lysosomal dysfunction, and exhibited robust antitumor

effects in vivo (91). Other

derivatives, such as water-soluble UAOS-Na with improved

pharmacokinetics (92) and UA312

with radioprotective effects in zebrafish models (93), further demonstrate the versatility

of rational structural modifications. Substitutions at key

positions (for example, C-3 or C-28) have also generated potent

derivatives with selective activity against leukemia and glioma

cells (94).

Collectively, nanoparticle-based strategies,

including polymeric nanoparticles and gold/PLGA nanocomposites,

have proven most effective in improving water solubility, tumor

targeting and controlled release, thereby enhancing intra-tumoral

accumulation and antitumor efficacy. Liposomal and nanofiber-based

formulations provide additional advantages in topical delivery and

tissue penetration, making them particularly promising for breast

cancer with skin involvement. By contrast, structural derivatives

such as FZU3010 and UA232 demonstrate superior pharmacological

potency and a broader range of mechanisms, including apoptosis,

ferroptosis and ER stress, although their pharmacokinetic

advantages remain less established compared with nanoparticle

systems. Taken together, these complementary approaches indicate

that while nanoparticles effectively overcome bioavailability

limitations, rational structural modifications expand UA's

mechanistic spectrum and therapeutic potential. Future

translational studies could benefit from combining both

strategies-for example, encapsulating potent derivatives into

advanced nanocarriers-to maximize bioavailability, therapeutic

efficacy and clinical applicability.

Challenges and future perspectives

UA has demonstrated broad-spectrum antitumor

potential in gynecologic malignancies, including ovarian

endometrial cervical and breast cancers. Its anticancer mechanisms

are multifaceted, involving the induction of apoptosis, cell cycle

arrest, regulation of metabolic reprogramming, inhibition of CSC

properties and enhancement of chemotherapeutic efficacy (95). Studies have shown that UA induces

apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells through the activation of caspase

cascades, upregulation of the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and inhibition of the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, thereby effectively suppressing tumor

cell proliferation. Notably, when used in combination with

chemotherapeutic agents, UA not only enhances their antitumor

effects but also alleviates associated toxicities, such as

CDDP-induced ototoxicity. Moreover, UA has been reported to exert

antitumor effects in ovarian cancer by inhibiting glycolysis and

modulating the KLF5/PI3K/AKT signaling axis, offering a novel

strategy to overcome chemoresistance. In endometrial and cervical

cancers, UA also exhibits potent antiproliferative and

pro-apoptotic activities. Particularly in cervical cancer, UA

activates the Fas/caspase-mediated apoptotic pathway and suppresses

HPV-related oncogene expression, demonstrating both antiviral and

antitumor effects. Regarding its synergistic role in cervical

cancer chemotherapy, UA has been found to enhance the efficacy of

paclitaxel and CDDP by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Importantly, it exerts minimal toxicity on normal cells,

highlighting its potential for clinical application as an adjuvant

therapeutic agent (Table SII).

Although UA demonstrates promising antitumor

activity in vitro and in animal models, its clinical

application is significantly hindered by poor oral bioavailability

and complex metabolic processing. As a Biopharmaceutics

Classification System Class IV compound, UA suffers from low

aqueous solubility and limited intestinal permeability, resulting

in poor absorption and diminished therapeutic efficacy (96). Following oral administration, UA is

primarily distributed to the lungs, spleen and liver, but undergoes

extensive first-pass metabolism-mainly through cytochrome P450

enzymes CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 in the liver and intestines-thereby

reducing its systemic exposure and bioactivity (90,92).

To overcome these limitations, various advanced drug delivery

systems-such as chitosan-modified nanoparticles, liposomes and

co-amorphous formulations-have been developed to improve UA's

solubility, bioavailability and tumor-targeting capacity (87–91).

These strategies have shown encouraging results in preclinical

models, including enhanced oral absorption and increased

accumulation at tumor sites. Nonetheless, their clinical utility

remains uncertain and requires further optimization and validation

(97). In addition, the safety and

long-term toxicity profile of UA are not yet fully understood.

Although current data suggest minimal toxicity toward normal cells

in short-term studies, potential off-target effects,

bioaccumulation and organ-specific toxicity following prolonged

administration cannot be excluded. Most available evidence is

limited to preclinical research, highlighting the urgent need for

systematic and long-term toxicological evaluations to support

future clinical development.

UA has shown promise as an adjuvant agent in

gynecological cancers, where it can enhance the efficacy of

conventional chemotherapeutic drugs such as CDDP and paclitaxel

while reversing drug resistance. Its therapeutic potential in

breast cancer, particularly TNBC, also merits further

investigation. However, most current evidence derives from in

vitro studies and small animal models, and robust clinical

trial data are still lacking. Future research should therefore

prioritize clinical evaluation of UA to clarify its

pharmacodynamics, safety and potential synergistic effects with

standard treatments. In addition, the development of UA derivatives

and novel combinatory regimens with other anticancer agents,

including immunotherapies, represents an important direction.

Notably, UA's anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties

suggest that it may improve the tumor immune microenvironment and

enhance responsiveness to immune checkpoint inhibitors such as

PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, although this hypothesis requires validation

in preclinical and clinical studies.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

TC drafted the manuscript and prepared the figures.

SS conducted the literature search and data collection. ZZ revised

and proofread the manuscript. XZ supervised the overall study

design, guided the research direction, and was responsible for

manuscript drafting and final approval of the submitted version.

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Hanvic B and Ray-Coquard I: Gynecological

sarcomas: Literature review of 2020. Curr Opin Oncol. 33:345–350.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Korenaga TK and Tewari KS: Gynecologic

cancer in pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol. 157:799–809. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Marcolin JC, Lichtenfels M, da Silva CA

and de Farias CB: Gynecologic and breast cancers: What's new in

chemoresistance and chemosensitivity tests? Curr Probl Cancer.

47:1009962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Alizadeh H, Akbarabadi P, Dadfar A, Tareh

MR and Soltani B: A comprehensive overview of ovarian cancer stem

cells: Correlation with high recurrence rate, underlying

mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Mol Cancer. 24:1352025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhang M, Liu C, Tu J, Tang M, Ashrafizadeh

M, Nabavi N, Sethi G, Zhao P and Liu S: Advances in cancer

immunotherapy: Historical perspectives, current developments, and

future directions. Mol Cancer. 24:1362025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rosenbaum SR, Hughes CJ, Fields KM, Purdy

SC, Gustafson AL, Wolin A, Hampton D, Shrivastava NM, Turner N,

Danis E, et al: EYA3 regulation of NF-κB and CCL2 suppresses

cytotoxic NK cells in the premetastatic niche to promote TNBC

metastasis. Sci Adv. 11:eadt05042025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Konstantinopoulos PA and Matulonis UA:

Clinical and translational advances in ovarian cancer therapy. Nat

Cancer. 4:1239–1257. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gupta R, Kumar R, Penn CA and Wajapeyee N:

Immune evasion in ovarian cancer: Implications for immunotherapy

and emerging treatments. Trends Immunol. 46:166–181. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Makker V, MacKay H, Ray-Coquard I, Levine

DA, Westin SN, Aoki D and Oaknin A: Endometrial cancer. Nat Rev Dis

Primers. 7:882021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Burd EM: Human papillomavirus and cervical

cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 16:1–17. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Qin SY, Cheng YJ, Lei Q, Zhang AQ and

Zhang XZ: Combinational strategy for high-performance cancer

chemotherapy. Biomaterials. 171:178–197. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zemek RM, Anagnostou V, Pires da Silva I,

Long GV and Lesterhuis WJ: Exploiting temporal aspects of cancer

immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 24:480–497. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Stewart MD, Keane A, Butterfield LH,

Levine BL, Thompson B, Xu Y, Ramsborg C, Lee A, Kalos M, Koerner C,

et al: Accelerating the development of innovative cellular therapy

products for the treatment of cancer. Cytotherapy. 22:239–246.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang X, Wei X, Shi L, Jiang H, Ma F, Li

Y, Li C and Ma Y and Ma Y: The latest research progress: Active

components of traditional Chinese medicine as promising candidates

for ovarian cancer therapy. J Ethnopharmacol. 337:1188112025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Shafabakhsh R and Asemi Z: Quercetin: A

natural compound for ovarian cancer treatment. J Ovarian Res.

12:552019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Liu Z, Zhu W, Kong X, Chen X, Sun X, Zhang

W and Zhang R: Tanshinone IIA inhibits glucose metabolism leading

to apoptosis in cervical cancer. Oncol Rep. 42:1893–1903.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Zhang X, Zhu L, Wang X, Zhang H, Wang L

and Xia L: Basic research on curcumin in cervical cancer: Progress

and perspectives. Biomed Pharmacother. 162:1145902023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sandhu SS, Rouz SK, Kumar S, Swamy N,

Deshmukh L, Hussain A, Haque S and Tuli HS: Ursolic acid: A

pentacyclic triterpenoid that exhibits anticancer therapeutic

potential by modulating multiple oncogenic targets. Biotechnol

Genet Eng Rev. 39:729–759. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kashyap D, Tuli HS and Sharma AK: Ursolic

acid (UA): A metabolite with promising therapeutic potential. Life

Sci. 146:201–213. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sun Q, He M, Zhang M, Zeng S, Chen L, Zhou

L and Xu H: Ursolic acid: A systematic review of its pharmacology,

toxicity and rethink on its pharmacokinetics based on PK-PD model.

Fitoterapia. 147:1047352020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cargnin ST and Gnoatto SB: Ursolic acid

from apple pomace and traditional plants: A valuable triterpenoid

with functional properties. Food Chem. 220:477–489. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ramos-Hryb AB, Pazini FL, Kaster MP and

Rodrigues ALS: Therapeutic potential of ursolic acid to manage

neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases. CNS Drugs.

31:1029–1041. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Song YH, Jeong SJ, Kwon HY, Kim B, Kim SH

and Yoo DY: Ursolic acid from Oldenlandia diffusa induces apoptosis

via activation of caspases and phosphorylation of glycogen synthase

kinase 3 beta in SK-OV-3 ovarian cancer cells. Biol Pharm Bull.

35:1022–1028. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang X, Li T, Gong ES and Liu RH:

Antiproliferative activity of ursolic acid in MDA-MB-231 human

breast cancer cells through Nrf2 pathway regulation. J Agric Food

Chem. 68:7404–7415. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yim EK, Lee KH, Namkoong SE, Um SJ and

Park JS: Proteomic analysis of ursolic acid-induced apoptosis in

cervical carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 235:209–220. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Khwaza V and Aderibigbe BA: Potential

pharmacological properties of triterpene derivatives of ursolic

acid. Molecules. 29:38842024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Shi Y, Leng Y, Liu D, Liu X, Ren Y, Zhang

J and Chen F: Research advances in protective effects of ursolic

acid and oleanolic acid against gastrointestinal diseases. Am J

Chin Med. 49:413–435. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu HR, Ahmad N, Lv B and Li C: Advances

in production and structural derivatization of the promising

molecule ursolic acid. Biotechnol J. 16:e20006572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Giacinti G, Raynaud C, Capblancq S and

Simon V: Evaluation and prevention of the negative matrix effect of

terpenoids on pesticides in apples quantification by gas

chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 1483:8–19.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Li H, Liu Y, Guo S, Shi M, Qin S and Zeng

C: Extraction of ursolic acid from apple peel with hydrophobic deep

eutectic solvents: comparison between response surface methodology

and artificial neural networks. Foods. 12:3102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Xia EQ, Yu YY, Xu XR, Deng GF, Guo YJ and

Li HB: Ultrasound-assisted extraction of oleanolic acid and ursolic

acid from Ligustrum lucidum Ait. Ultrason Sonochem. 19:772–776.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Xia EQ, Wang BW, Xu XR, Zhu L, Song Y and

Li HB: Microwave-assisted extraction of oleanolic acid and ursolic

acid from Ligustrum lucidum Ait. Int J Mol Sci. 12:5319–5329. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

K V, L S, N V K, R P, M P DR, Suneetha C,

Palpandi Raja R and Muthusamy S: Promising approaches in the

extraction, characterization, and biotechnological applications of

ursolic acid: A review. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 55:973–984. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Mlala S, Oyedeji AO, Gondwe M and Oyedeji

OO: Ursolic acid and its derivatives as bioactive agents.

Molecules. 24:27512019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Khwaza V, Oyedeji OO and Aderibigbe BA:

Ursolic acid-based derivatives as potential anti-cancer agents: An

update. Int J Mol Sci. 21:59202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Erdmann J, Kujaciński M and Wiciński M:

Beneficial effects of ursolic acid and its derivatives-focus on

potential biochemical mechanisms in cardiovascular conditions.

Nutrient. 13:39002021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Lin W and Ye H: Anticancer activity of

ursolic acid on human ovarian cancer cells via ROS and MMP mediated

apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and downregulation of PI3K/AKT

pathway. J BUON. 25:750–756. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Ganapathy-Kanniappan S and Geschwind JF:

Tumor glycolysis as a target for cancer therapy: Progress and

prospects. Mol Cancer. 12:1522013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Xu M, Li X, Yuan C, Zhu T, Wang M, Zhu Y,

Duan Y, Yao J, Luo B, Wang Z, et al: Ursolic acid inhibits

glycolysis of ovarian cancer via KLF5/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

Am J Chin Med. 52:2211–2231. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liu H, Zou J, Li X, Ge Y and He W: Drug

delivery for platinum therapeutics. J Control Release. 380:503–523.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Talach T, Rottenberg J, Gal B, Kostrica R,

Jurajda M, Kocak I, Lakomy R and Vogazianos E: Genetic risk factors

of cisplatin induced ototoxicity in adult patients. Neoplasma.

63:263–268. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Di Y, Xu T, Tian Y, Ma T, Qu D, Wang Y,

Lin Y, Bao D, Yu L, Liu S and Wang A: Ursolic acid protects against

cisplatin-induced ototoxicity by inhibiting oxidative stress and

TRPV1-mediated Ca2+-signaling. Int J Mol Med. 46:806–816. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Li W, Luo L, Shi W, Yin Y and Gao S:

Ursolic acid reduces Adriamycin resistance of human ovarian cancer

cells through promoting the HuR translocation from cytoplasm to

nucleus. Environ Toxicol. 36:267–275. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Batlle E and Clevers H: Cancer stem cells

revisited. Nat Med. 23:1124–1134. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Saw PE, Liu Q, Wong PP and Song E: Cancer

stem cell mimicry for immune evasion and therapeutic resistance.

Cell Stem Cell. 31:1101–1112. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wang WJ, Sui H, Qi C, Li Q, Zhang J, Wu

SF, Mei MZ, Lu YY, Wan YT, Chang H and Guo PT: Ursolic acid

inhibits proliferation and reverses drug resistance of ovarian

cancer stem cells by downregulating ABCG2 through suppressing the

expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in vitro. Oncol Rep.

36:428–440. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhang J, Wang W, Qian L, Zhang Q, Lai D

and Qi C: Ursolic acid inhibits the proliferation of human ovarian

cancer stem-like cells through epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

Oncol Rep. 34:2375–2384. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Yim EK, Lee MJ, Lee KH, Um SJ and Park JS:

Antiproliferative and antiviral mechanisms of ursolic acid and

dexamethasone in cervical carcinoma cell lines. Int J Gynecol

Cancer. 16:2023–2031. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Leng S, Hao Y, Du D, Xie S, Hong L, Gu H,

Zhu X, Zhang J, Fan D and Kung HF: Ursolic acid promotes cancer

cell death by inducing Atg5-dependent autophagy. Int J Cancer.

133:2781–2790. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Guo JL, Han T, Bao L, Li XM, Ma JQ and

Tang LP: Ursolic acid promotes the apoptosis of cervical cancer

cells by regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Obstet Gynaecol

Res. 45:877–881. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Li Y, Xing D, Chen Q and Chen WR:

Enhancement of chemotherapeutic agent-induced apoptosis by

inhibition of NF-kappaB using ursolic acid. Int J Cancer.

127:462–473. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Achiwa Y, Hasegawa K and Udagawa Y: Effect

of ursolic acid on MAPK in cyclin D1 signaling and RING-type E3

ligase (SCF E3s) in two endometrial cancer cell lines. Nutr Cancer.

65:1026–1033. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Achiwa Y, Hasegawa K and Udagawa Y:

Molecular mechanism of ursolic acid induced apoptosis in poorly

differentiated endometrial cancer HEC108 cells. Oncol Rep.

14:507–512. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Achiwa Y, Hasegawa K and Udagawa Y:

Regulation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt and the

mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways by ursolic acid in human

endometrial cancer cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 71:31–37.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Achiwa Y, Hasegawa K, Komiya T and Udagawa

Y: Ursolic acid induces Bax-dependent apoptosis through the

caspase-3 pathway in endometrial cancer SNG-II cells. Oncol Rep.

13:51–57. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

De Angel RE, Smith SM, Glickman RD,

Perkins SN and Hursting SD: Antitumor effects of ursolic acid in a

mouse model of postmenopausal breast cancer. Nutr Cancer.

62:1074–1086. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Wang JS, Ren TN and Xi T: Ursolic acid

induces apoptosis by suppressing the expression of FoxM1 in MCF-7

human breast cancer cells. Med Oncol. 29:10–15. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Kassi E, Sourlingas TG, Spiliotaki M,

Papoutsi Z, Pratsinis H, Aligiannis N and Moutsatsou P: Ursolic

acid triggers apoptosis and Bcl-2 downregulation in MCF-7 breast

cancer cells. Cancer Invest. 27:723–733. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Mallepogu V, Sankaran KR, Pasala C, Bandi

LR, Maram R, Amineni UM and Meriga B: Ursolic acid regulates key

EMT transcription factors, induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis

in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 breast cancer cells, an in-vitro and in

silico studies. J Cell Biochem. 124:1900–1918. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Manouchehri JM and Kalafatis M: Ursolic

acid promotes the sensitization of rhTRAIL-resistant

triple-negative breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 38:6789–6795. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Guo W, Xu B, Wang X, Zheng B, Du J and Liu

S: The analysis of the anti-tumor mechanism of ursolic acid using

connectively map approach in breast cancer cells line MCF-7. Cancer

Manag Res. 12:3469–3476. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Kim GD: Ursolic acid decreases the

proliferation of MCF-7 cell-derived breast cancer stem-like cells

by modulating the ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Prev Nutr

Food Sci. 26:434–444. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Zhao C, Yin S, Dong Y, Guo X, Fan L, Ye M

and Hu H: Autophagy-dependent EIF2AK3 activation compromises

ursolic acid-induced apoptosis through upregulation of MCL1 in

MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Autophagy. 9:196–207. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Gupta KB, Gao J, Li X, Thangaraju M, Panda

SS and Lokeshwar BL: Cytotoxic autophagy: A novel treatment

paradigm against breast cancer using oleanolic acid and ursolic

acid. Cancers (Basel). 16:33672024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Lewinska A, Adamczyk-Grochala J,

Kwasniewicz E, Deregowska A and Wnuk M: Ursolic acid-mediated

changes in glycolytic pathway promote cytotoxic autophagy and

apoptosis in phenotypically different breast cancer cells.

Apoptosis. 22:800–815. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Fogde DL, Xavier CPR, Balnytė K, Holland

LKK, Stahl-Meyer K, Dinant C, Corcelle-Termeau E, Pereira-Wilson C,

Maeda K and Jäättelä M: Ursolic acid impairs cellular lipid

homeostasis and lysosomal membrane integrity in breast carcinoma

cells. Cells. 11:40782022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Guerra ÂR, Paulino AF, Castro MM, Oliveira

H, Duarte MF and Duarte IF: Triple negative breast cancer and

breast epithelial cells differentially reprogram glucose and lipid

metabolism upon treatment with triterpenic acids. Biomolecules.

10:11632020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Wang S, Chang X, Zhang J, Li J, Wang N,

Yang B, Pan B, Zheng Y, Wang X, Ou H and Wang Z: Ursolic acid

inhibits breast cancer metastasis by suppressing glycolytic

metabolism via activating SP1/caveolin-1 signaling. Front Oncol.

11:7455842021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Mandal S, Gamit N, Varier L, Dharmarajan A

and Warrier S: Inhibition of breast cancer stem-like cells by a

triterpenoid, ursolic acid, via activation of Wnt antagonist, sFRP4

and suppression of miRNA-499a-5p. Life Sci. 265:1188542021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Liao WL, Liu YF, Ying TH, Shieh JC, Hung

YT, Lee HJ, Shen CY and Cheng CW: Inhibitory effects of ursolic

acid on the stemness and progression of human breast cancer cells

by modulating argonaute-2. Int J Mol Sci. 24:3662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Yang X, Liang B, Zhang L, Zhang M, Ma M,

Qing L, Yang H, Huang G and Zhao J: Ursolic acid inhibits the

proliferation of triple-negative breast cancer stem-like cells

through NRF2-mediated ferroptosis. Oncol Rep. 52:942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Yeh CT, Wu CH and Yen GC: Ursolic acid, a

naturally occurring triterpenoid, suppresses migration and invasion

of human breast cancer cells by modulating c-Jun N-terminal kinase,

Akt and mammalian target of rapamycin signaling. Mol Nutr Food Res.

54:1285–1295. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Luo J, Hu YL and Wang H: Ursolic acid

inhibits breast cancer growth by inhibiting proliferation, inducing

autophagy and apoptosis, and suppressing inflammatory responses via

the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways in vitro. Exp Ther Med.

14:3623–3631. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Zhang Y, Ma X, Li H, Zhuang J, Feng F, Liu

L, Liu C and Sun C: Identifying the effect of ursolic acid against

triple-negative breast cancer: Coupling network pharmacology with

experiments verification. Front Pharmacol. 12:6857732021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Lu Q, Chen W, Ji Y, Liu Y and Xue X:

Ursolic acid enhances cytotoxicity of doxorubicin-resistant

triple-negative breast cancer cells via ZEB1-AS1/miR-186-5p/ABCC1

axis. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 37:673–683. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Wang Z, Zhang P, Jiang H, Sun B, Luo H and

Jia A: Ursolic acid enhances the sensitivity of MCF-7 and

MDA-MB-231 cells to epirubicin by modulating the autophagy pathway.

Molecules. 27:33992022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Zong L, Cheng G, Liu S, Pi Z, Liu Z and

Song F: Reversal of multidrug resistance in breast cancer cells by

a combination of ursolic acid with doxorubicin. J Pharm Biomed

Anal. 165:268–275. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Zong L, Cheng G, Zhao J, Zhuang X, Zheng

Z, Liu Z and Song F: Inhibitory effect of ursolic acid on the

migration and invasion of doxorubicin-resistant breast cancer.

Molecules. 27:12822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Luo F, Zhao J, Liu S, Xue Y, Tang D, Yang

J, Mei Y, Li G and Xie Y: Ursolic acid augments the

chemosensitivity of drug-resistant breast cancer cells to

doxorubicin by AMPK-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction. Biochem

Pharmacol. 205:1152782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Xiang F, Fan Y, Ni Z, Liu Q, Zhu Z, Chen

Z, Hao W, Yue H, Wu R and Kang X: Ursolic acid reverses the

chemoresistance of breast cancer cells to paclitaxel by targeting

MiRNA-149-5p/MyD88. Front Oncol. 9:5012019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Wang Y, Luo Z, Zhou D, Wang X, Chen J,

Gong S and Yu Z: Nano-assembly of ursolic acid with platinum

prodrug overcomes multiple deactivation pathways in

platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Biomater Sci. 9:4110–4119. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Jin H, Pi J, Yang F, Jiang J, Wang X, Bai

H, Shao M, Huang L, Zhu H, Yang P, et al: Folate-chitosan

nanoparticles loaded with ursolic acid confer anti-breast cancer

activities in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep. 6:307822016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Fu H, Wu TH, Ma CP and Yen FL: Improving

water solubility and skin penetration of ursolic acid through a

nanofiber process to achieve better in vitro anti-breast cancer

activity. Pharmaceutics. 16:11472024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Sharma R, Yadav V, Jha S, Dighe S and Jain

S: Unveiling the potential of ursolic acid modified hyaluronate

nanoparticles for combination drug therapy in triple negative

breast cancer. Carbohydr Polym. 338:1221962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Liu CH, Wong SH, Tai CJ, Tai CJ, Pan YC,

Hsu HY, Richardson CD and Lin LT: Ursolic acid and its

nanoparticles are potentiators of oncolytic measles virotherapy

against breast cancer cells. Cancers (Basel). 13:1362021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Wang S, Meng X and Dong Y: Ursolic acid

nanoparticles inhibit cervical cancer growth in vitro and in vivo

via apoptosis induction. Int J Oncol. 50:1330–1340. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Li W, Zhang H, Nie M, Tian Y, Chen X, Chen

C, Chen H and Liu R: Ursolic acid derivative FZU-03,010 inhibits

STAT3 and induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in renal and

breast cancer cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai).

49:367–373. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Li W, Zhang H, Nie M, Wang W, Liu Z, Chen

C, Chen H, Liu R, Baloch Z and Ma K: A novel synthetic ursolic acid

derivative inhibits growth and induces apoptosis in breast cancer

cell lines. Oncol Lett. 15:2323–2329. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Tang Q, Liu Y, Li T, Yang X, Zheng G, Chen

H, Jia L and Shao J: A novel co-drug of aspirin and ursolic acid

interrupts adhesion, invasion and migration of cancer cells to

vascular endothelium via regulating EMT and EGFR-mediated signaling

pathways: Multiple targets for cancer metastasis prevention and

treatment. Oncotarget. 7:73114–73129. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Pattnaik B, Lakshmi JK, Kavitha R,

Jagadeesh B, Bhattacharjee D, Jain N and Mallavadhani UV:

Synthesis, structural studies, and cytotoxic evaluation of novel

ursolic acid hybrids with capabilities to arrest breast cancer

cells in mitosis. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 19:260–271. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Gou W, Luo N, Yu B, Wu H, Wu S, Tian C,

Guo J, Ning H, Bi C, Wei H, et al: Ursolic acid derivative UA232

promotes tumor cell apoptosis by inducing endoplasmic reticulum

stress and lysosomal dysfunction. Int J Biol Sci. 18:2639–2651.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Wang M, Gu C, Yang Y, Chen L, Chen K, Du

J, Wu H and Li Y: Ursolic acid derivative UAOS-Na treats

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by immunoregulation and

protecting myelin. Front Neurol. 14:12698622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Xu FF, Shang Y, Wei HQ, Zhang WY, Wang LX,

Hu T, Zhang SQ, Li YL, Shang HH, Hou WB, et al: Ursolic acid

derivative UA312 ameliorates ionizing radiation-induced

cardiotoxicity and neurodevelopmental toxicity in zebrafish via

targeting chrna3 and grik5. Acta Pharmacol Sin. April 28–2025.(Epub

ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

da Silva EF, de Vargas AS, Willig JB, de

Oliveira CB, Zimmer AR, Pilger DA, Buffon A and Gnoatto SCB:

Synthesis and antileukemic activity of an ursolic acid derivative:

A potential co-drug in combination with imatinib. Chem Biol

Interact. 344:1095352021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Shanmugam MK, Dai X, Kumar AP, Tan BK,

Sethi G and Bishayee A: Ursolic acid in cancer prevention and

treatment: molecular targets, pharmacokinetics and clinical

studies. Biochem Pharmacol. 85:1579–1587. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Antonio E, Dos Reis Antunes Junior O,

Marcano RGDJV, Diedrich C, da Silva Santos J, Machado CS, Khalil NM

and Mainardes RM: Chitosan modified poly (lactic acid)

nanoparticles increased the ursolic acid oral bioavailability. Int

J Biol Macromol. 172:133–142. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Namdeo P, Gidwani B, Tiwari S, Jain V,

Joshi V, Shukla SS, Pandey RK and Vyas A: Therapeutic potential and

novel formulations of ursolic acid and its derivatives: An updated

review. J Sci Food Agric. 103:4275–4292. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|