Introduction

Unicellular algae, including cyanobacteria, commonly

known to the general public as microalgae, have been recognized for

their potential in commercial production as functional foods. The

most widely utilized species in this category include

Chlamydomonas, Chlorella, Haematococcus

pluvialis and Arthrospira platensis. These organisms are

ubiquitous photoautotrophs, thriving in both marine and freshwater

environments. They capture solar energy and use CO2 and

mineral salts to synthesize carbohydrates for energy (1,2).

Owing to their broad applicability, microalgae are often termed

‘green biofactories’. Their increasing use in the production of

natural products, nutraceuticals, pharmaceuticals and food

ingredients is due to their palatability and rich content of

proteins, essential amino acids, vitamins and minerals (3).

Microalgae are a valuable resource, which could be

particularly beneficial in developing countries, due to their rapid

growth, energy efficiency and rich nutrient profile. They can

contain protein levels as high as 60-70% (surpassing those in meat

and milk), carbohydrates (up to 30-40%), essential minerals such as

iodine, iron and calcium, vitamins, and 10-20% omega-3, omega-6 and

omega-9 fatty acids (4). Their

versatility has attracted increasing interest from industries

aiming to develop healthier and more sustainable products,

including natural food colorants and eco-friendly biodiesel.

Microalgae are particularly appreciated for their rapid growth,

ease of harvesting, efficient drying into powder form and long

shelf life (5).

Arthrospira platensis, commonly known as

Spirulina platensis (SP), is a cyanobacterium that exists in

two phases: A green phase under optimal growth conditions and a

blue phase when exposed to stress (6). Nutritionally, SP stands out for its

high protein content and abundance of vitamins (complexes B, D, E

and K), minerals (calcium, magnesium, iron, potassium, zinc,

copper, manganese, chromium and selenium), β-carotene, and

polyunsaturated fatty acids from the omega-3 and omega-6 series

(7). Above all, Spirulina is

especially known for its phycocyanin (PC) content, a blue pigment

protein widely recognized for its significant health-promoting

properties and frequently used as a dietary supplement. This

natural pigment has been shown to exhibit strong antioxidant,

anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective (liver-protecting) and

neuroprotective (nerve-protecting) effects in various in

vitro and in vivo studies (8). Due to its extensive therapeutic

potential, phycocyanin is increasingly incorporated into health and

wellness products aimed at supporting cellular health, reducing

oxidative stress and preventing chronic inflammation (9). Its favorable safety and

biocompatibility also support further research and application in

preventive medicine and nutraceutical development (10). These components are known for their

preventive effects on the cardiovascular system and their potent

antioxidant properties (11). SP

extracts are also used to prevent and manage conditions linked to

metabolic syndrome-related disorders (3), oxidative stress, and diseases such as

atherosclerosis, cardiac hypertrophy, heart failure and

hypertension (12).

Selenium (symbol, Se) is a key trace element present

in some microalgae, including, including SP. It plays a crucial

role in human nutrition as a structural component of antioxidant

enzymes, such as glutathione peroxidase and reductase, which help

mitigate oxidative stress (11).

Oxidative stress is a major biological event that can negatively

affect the health and function of living organisms (13). This imbalance may contribute to

conditions, such type 2 diabetes (often associated with

hyperlipidemia), ischemia, cardiovascular diseases,

neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's, and cancer; the

free radicals produced in these processes can also cause severe

organ damage (14). Over the

years, research has aimed to identify the most effective selenium

sources and, numerous investigations have indicated that selenium

nanoparticles derived from Spirulina exhibit significant anti-tumor

activity, (15) exhibiting greater

efficacy in inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis than larger

selenium particles (16).

The present systematic review aimed to evaluate the

antioxidant and cytotoxic efficacy of selenium-enriched SP (Se-SP)

and selenium-containing phycocyanin (Se-PC), a major bioactive

component derived from Se-SP, by synthesizing evidence from both

in vivo and in vitro studies. The primary objective

was to determine whether selenium enrichment enhances the

biological activity of these compounds compared to their

non-enriched counterparts (Spirulina or phycocyanin alone). By

comparing Se-SP and Se-PC to their respective controls, the present

systematic review sought to clarify their potential health benefits

and inform future applications in nutritional and therapeutic

interventions.

Data and methods

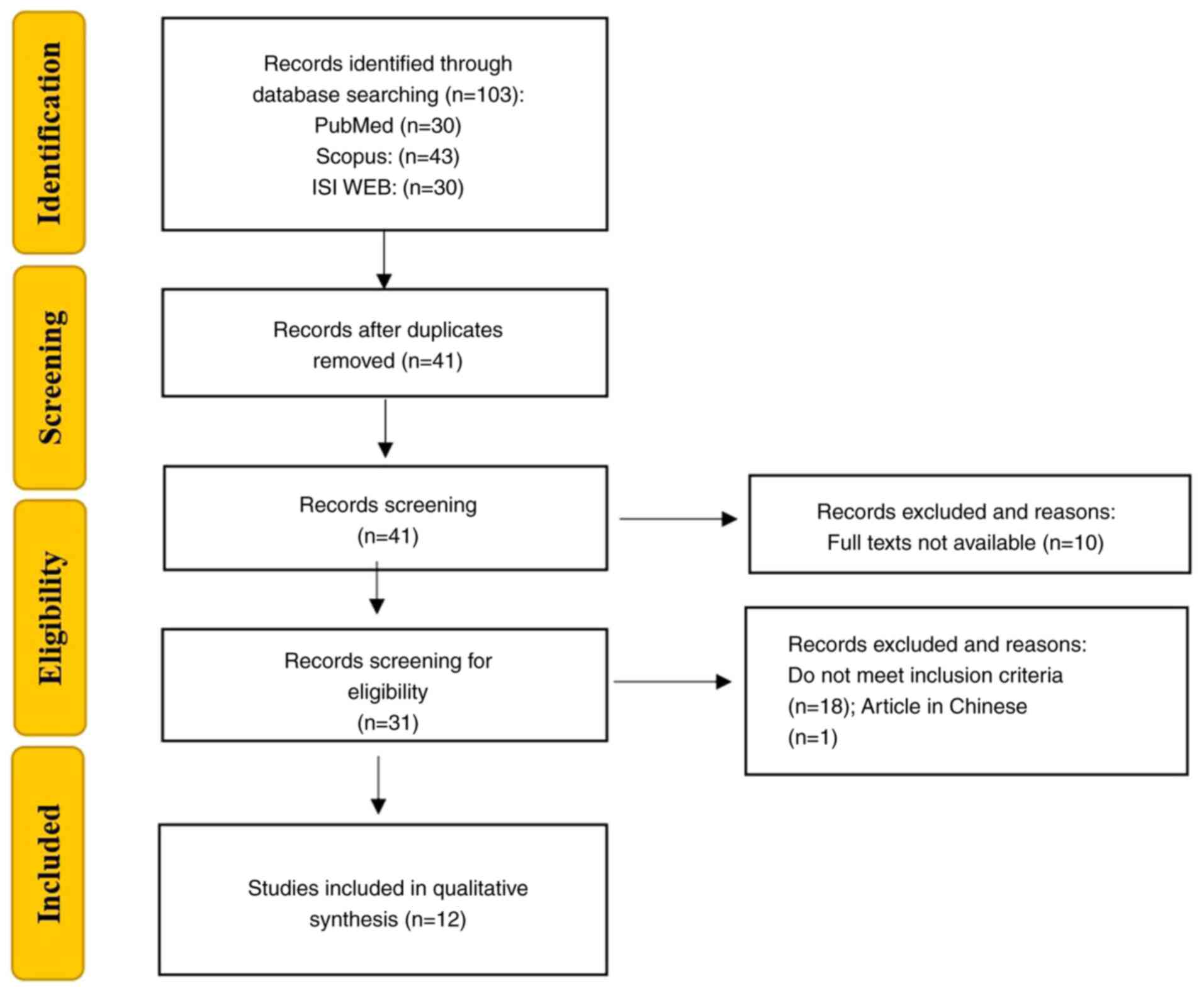

The present systematic review followed the Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)

guidelines. Studies were included if they met the following

criteria: Published in the English language; investigated the

antioxidant and/or cytotoxic activities of Se-SP or Se-PC; employed

in vitro and/or in vivo experimental models; included

at least one comparative group treated with non-enriched Spirulina

or phycocyanin, in order to isolate and assess the specific

contribution of the organic selenium component to the observed

biological effects. Studies that were reviews, conference

proceedings, editorials, articles without available full texts and

those published outside the specified time frame were excluded from

the review. A comprehensive literature search was conducted using

the PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science databases, focusing the

search on title and abstract by the use of the following key words:

Selenium-containing AND phycocyanin; selenium-enriched AND

spirulina. The selection process is detailed in a PRISMA flowchart,

including both included and excluded studies with the reasons for

exclusion (Fig. 1). The selected

studies are summarized in Table I,

which outlines the study objectives, the cellular or animal models

used, the experimental conditions, and a concise summary of the

most effective treatment identified in each case.

| Table ISelected studies from the scientific

literature. |

Table I

Selected studies from the scientific

literature.

| First author, year

of publication | Highlights | In vivo

experimental groups | In vitro

experimental groups | Se-SP and Se-PC vs.

SP and PC | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Yang, 2024 | Aim: Investigate

the therapeutic potential of selenium-containing protein extracted

from Se-enriched Spirulina platensis (Se-SP) in alleviating

osteoporosis by modulating inflammation, osteoblast activity, and

osteoclasto genesis in vitro and in vivo. Animal

Model: Female C57 mice Cell line: MC3T3-E1 | Control group: Mice

that underwent a mock surgery without ovariectomy. OVX group

(Ovariectomy): Mice that underwent ovariectomy without additional

treatment. SP-treated group: OVX mice treated with 10 mg/kg SP via

intraperitoneal injections every other day for 2 months.

Se-SP-treated group: OVX mice treated with 10 mg/kg Se-SP via

intraperitoneal injections every other day for 2 months. | Control group:

Cells were cultured in a differentiation medium without any

treatment. SP-treated groups: Cells were treated with SP at

concentrations of 5 and 10 µg/ml for 14 days in the differentiation

medium. Se-SP-treated groups: Cells were treated with Se-SP at

concentrations of 5 and 10 µg/ml for 14 days in the differentiation

medium | Compared to SP

alone, Se-SP demonstrated superior efficacy in reversing bone loss

and restoring bone microarchitecture in ovariectomized mice. | (25) |

| Castel, 2024 | Aim: Evaluate the

effectiveness of Se-SP in restoring selenium levels and modulating

antioxidant enzyme activities and selenoprotein expression in rats

fed a selenium-deficient diet. Animal model: Old female Wistar

rats | Pre-treatment: 8

weeks with Se deficient diet Control: Se sufficient diet containing

0.3 mg Se/kg of food; Deficient group (D):only water for 4 weeks;

SS: SS at adose of 20 µg Se/kg b.w. day in water for 4 weeks. SP: 3

g/kg b.w. day of SP in water for 4 weeks Se-SP: 3 g/kg b.w. day of

Se-SP (providing 20 µg Se/kg b.w. day) in water for 4 weeks. | NA | Se-SP ensures

better selenium distribution and tissue bioavailability, while SS

more effectively enhances antioxidant enzyme activity and certain

selenoprotein expressions. SP alone shows only marginal antioxidant

benefit without selenium repletion. | (24) |

| Shen, 2023 | Aim: Evaluate the

efficacy of Se-PC in photodynamic therapy (PDT) against lung cancer

and compare its effects to other treatments, including PC-PDT and

PC combined with SS. Animal model: Lung carcinoma-bearing male mice

C57BL/6 Cell line: LLC cell | Control: Mice

injected with normal saline (0.2 ml), every 3 days and for 11 days.

Laser-only: Laser light (630 nm at 100 J/cm²) for 4 h after

receiving 0.2 ml of normal saline, every 3 days and for 11 days.

PC-PDT Mice injected with 0.2 ml of PC (15 mg/ml) and exposed to

laser light (630 nm at 100 J/cm²) for 4 h every 3 days and for 11

days. PC + SS-PDT: Mice injected with a combination of 0.2 ml of PC

(15 mg/ml) and SS at an equivalent Se dose to the Se-PC group,

followed by laser light (630 nm at 100 J/cm²) for 4 h, every 3 days

and for 11 days. Se-PC-PDT: Mice injected with 0.2 ml of Se-PC (15

mg/mll) and exposed to laser light (630 nm at 100 J/cm²) for 4 h,

every 3 days and for 11 days. | Control: Cells with

no treatment. PC-PDT: Cells treated with 150 µg/ml of PC, then

exposed to laser light (26 J/cm²) for 9 min and incubated for 12 h

SS + PC-PDT: Cells treated with a combination of 150 µg/ml PC and

1.14 µg/ml SS (providing an equivalent Se content to the Se-PC

group) and exposed to the same laser parameters (26 J/cm² for 9

min) and incubated for 12 h. Se-PC PDT: Cells treated with 150

µg/ml Se-PC, then exposed to laser light (26 J/cm² for 9 min) and

incubated for 12 h. | Se-PC represents

the most effective and balanced treatment, offering strong

cytotoxicity against tumor cells while preserving antioxidant

defenses in normal tissues and minimizing systemic toxicity. Its

dual action on tumor inhibition and immune activation makes it the

most promising strategy among the three approaches evaluated. | (30) |

| Castel, 2021 | Aim: Evaluate the

effects of Se-SP supplementation on sepsis outcomes in

selenium-deficient rats. Animal model: female Wistar rats | Pre-treatment: 8

weeks with Sedeficient diet Deficient group (D): Continued to

receive Sedeficient food and tap water for 4 weeks. SS: Se

supplementation in the form of SS (20 µg Se/kg b.w. day) in

drinking water for 4 weeks. SP: SP powder (3 g/kg b.w. day) in

drinking water for 4 weeks. Se-SP: Se-SP (3 g/kg b.w. day),

providing 20 µg of Se/kg b.w. day in drinking water for 4 weeks.

Post-treatment: Sepsis induced in a subgroup of each group using

the cecal ligature and puncture (CLP) method. Another subgroup

underwent a sham surgery (laparotomy only) to serve as a

control. | NA | SS remains the most

effective option in correcting selenium deficiency and mitigating

sepsis-induced oxidative and metabolic disturbances. Se-SP shows

promise in upregu-lating antioxidant genes, but fails to deliver

functional protection in the acute setting, likely due to lower

bioavailability of organic Se forms (e.g., SeMet) or matrix

interactions. SP alone, while theoretically antioxidant, offered no

protective effect and may even exacerbate early stress responses in

sepsis | (23) |

| Song, 2021 | Aim:

Neuroprotective effects of selenium-containing protein derived from

Se-SP under conditions simulating ischemic injury induced by

oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD). Cell line: Primary hippocampal

neurons isolated from Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats | NA | Control: Cells with

no treatments. OGD: Cells subjected to oxygen-glucose deprivation

(OGD) for 6 h without any additional treatment. SP: Cells treated

with 5 or 10 µg/ml of SP during OGD exposure for 6 h. Se-SP: Cells

treated with 5 or 10 µg/ml of Se-SP during OGD exposure for 6 h.

CsA + OGD: Cells pre-treated with 5 µM CsA (cyclosporine A) for 30

min, followed by OGD exposure for 6 h.CsA + SP + OGD: Cells

pre-treated with 5 µM CsA for 30 min, followed by 5 or 10 µg/ml SP

treatment during OGD exposure for 6 h. CsA + Se-SP + OGD: Cells

pre-treated with 5 µM CsA for 30 min, followed by 5 or 10 µg/ml.

Se-SP treatment during OGD exposure for 6 h. | Se-SP showed

superior antioxidant and cytoprotective effects compared to SP

alone, effectively reducing ROS, preserving mitochondrial function,

and preventing neuronal apoptosis under OGD conditions | (22) |

| Lin, 2020 | Aim: Investigate

the protective effects and underlying mechanisms of Se-SP against

high glucose-induced calcification in mouse aortic vascular smooth

muscle cells (MOVAS). Cell line: Mouse aortic vascular smooth

muscle cells (MOVAS). | NA | Control: Cells

cultured with 5 mM glucose. High glucose: Cells exposed to 10-50 mM

glucose for 48 h to investigate dose-dependent effects on

proliferation; In calcification assays, cells were exposed to 25 mM

glucose for 14 days.SP: Cells treated with 5 or 10 µg/ml SP along

with 25 mM glucose for 14 days. Se-SP: Cells treated with 5 or 10

µg/ml Se-SP along with 25 mM glucose for 14 days. GSH

pre-treatment: (specific for ROS evaluation): Cells pre-treated

with 5 mM glutathione (GSH) for 2 h before exposure to 25 mM

glucose. MAPK inhibitor: Cells treated with 10 µM SP600125 (JNK

inhibitor) along with 25 mM glucose for 14 days | Se-SP effectively

counteracts high glucose-induced oxidative stress and calcification

in vascular cells, showing superior protective and antioxidant

properties compared to SP alone. | (21) |

| Sun, 2019 | Aim: Investigate

the protective effects of Se-SP against cisplatin-induced apoptosis

Cell line: MC3T3-E1 mouse preosteoblast cells. | | Control: Cells with

no treatments. Cisplatin-only: Cells exposed to 20, 40, or 80 µg/ml

cisplatin for 24 h. Se-SP: Cells pre-treated with 5, 10, or 20

µg/ml of Se-SP for 24 h before being co-treated with 40 or 80 µg/ml

of cisplatin for another 24 h. SP: Cells were with 80 µg/ml SP or

Se-SP alone for 48 h in cytotoxicity assays. Co-treatment: Cells

treated with 10 µg/ml Se-SP and 80 µg/ml cisplatin. | Se-SP showed strong

antioxidant and cytoprotective effects by preventing mitochondrial

dysfunction and ROS-mediated apoptosis in cisplatin-injured

osteoblasts. Unlike SP, Se-SP preserved cell viability and reduced

oxidative stress through mitochondrial stabilization and DNA

protection, highlighting its potential in chemoprevention of bone

damage. | (20) |

| Fu, 2018 | Aim: Investigate

the protective effects and underlying mechanisms of Se-SP against

chronic alcohol-induced liver injury. Animal model: KM mice Cell

line: HL7702 human liver cell line. | Control: Mice

treated with physiological saline. Model: Mice treated with 30%

absolute alcohol (10 ml/kg bw) via gavage for the last 15 days of

the experiment. SP: Mice treated with 200 mg/kg bw SP via gavage

daily for 42 days, with alcohol gavage during the last 15 days.

Low-dose Se-SP: Mice treated with 100 mg/kg bw of Se-SP via gavage

daily for 42 days, with alcohol gavage during the last 15 days.

Middle-dose Se-SP: Mice treated with 200 mg/kg bw of Se-SP via

gavage daily for 42 days, with alcohol gavage during the last 15

days. High-dose Se-SP: Mice treated with 400 mg/kg bw of Se-SP via

gavage daily for 42 days, with alcohol gavage during the last 15

days. | Control: Cells

cultured in normal conditions. Alcohol-only: Cells exposed to 200

mM ethanol for 24 h. SP: Cells co-treated with 200 mM ethanol and

200 µg/ml of SP for 24 h. Se-SP: Cells co-treated with 200 mM

ethanol and varying concentrations of Se-SP (50, 100, and 200

µg/ml) for 24 h. Positive control: Cells treated with an

antioxidant or apoptosis inhibitor. | Se-SP exhibits

strong protective effects against chronic alcohol-induced liver

injury both in vitro and in vivo. It outperforms native SP

by reducing apoptosis, autophagy, and pyroptosis, while enhancing

antioxidant enzyme activity. Its optimal effectiveness is observed

at 200 mg/kg, offering a promising dietary supplement for oxidative

liver damage | (19) |

| Liu, 2018 | Aim: Evaluate the

therapeutic potential of Se-PC in enhancing the efficacy of

photodynamic therapy (PDT) for cancer treatment. Animal model:

BALB/c mice. Cell line: HepG2 and the HL7702. | Control: Mice

received no treatment. Laser-only: Mice exposed to laser

irradiation 632.8 nm, (150 J/cm²) without any photosensitizer. PC:

Mice injected with 0.2 ml PC 10 mg/ml for 10 days without laser

irradiation Se-PC: Mice injected with 0.2 ml Se-PC 10 mg/ml for 10

days without laser irradiation. PC-PDT: Mice injected with 0.2 ml

of PC 10 mg/ml for 10 days and exposed to laser irradiation (150

J/cm²). Se-PC-PDT: Mice injected with 0.2 ml of Se-PC 10 mg/ml for

10 days and exposed to laser irradiation (150 J/cm²). | Control: Cells

cultured without treatments. PC: Cells treated with 50-400 µg/ml of

PC for 4 h. Se-PC: Cells treated with 50-200 µg/ml of Se-PC for 4

h.Laser: Cells exposed to laser irradiation (632.8 nm, 45 mW/cm²,

26 J/cm²) for 9 min without photosensitizer. PC-PDT: Cells treated

with PC (50-400 µg/ml) for 4 h, followed by laser irradiation.

Se-PC-PDT: Cells treated with Se-PC (50-200 µg/ml) for 4 h followed

by laser irradiation. | Se-PC combined with

PDT induces potent anticancer activity through

mitochondria-mediated apoptosis, partial inhibition of autophagy,

and enhanced antioxidant enzyme modulation. It demonstrates

stronger efficacy and higher tumour selectivity than PC alone,

offering a promising and safer strategy for liver tumour

therapy. | (29) |

| Zhang, 2011 | Aim: Evaluate Se-PC

protective effects against oxidative stress induced by AAPH

(2,2'-azobis (2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride). Specifically, the

study explored Se-APC's ability to inhibit reactive oxygen species

(ROS) generation, prevent lipid peroxidation, and protect

antioxidant defense systems in human erythrocytes. Cell line: human

erythrocytes | NA | Control group: No

oxidative agent, no treatment (baseline erythrocyte/plasma

conditions) AAPH group (oxidative stress control): Erythrocytes or

plasma treated with 100 mM AAPH only (oxidative stress inducer)

Se-APC pretreated groups: Erythrocytes or plasma pretreated with

Se-APC at concentrations ranging from 0.3 to 1.5 µM, then exposed

to 100 mM AAPH; Also used in plasma oxidation assay at 0.06 to 0.3

µM APC pretreated groups: Erythrocytes or plasma pretreated with

APC at matching concentrations to Se-APC (e.g., 0.3 µM), followed

by AAPH exposure Positive control for antioxidant comparison:

Included Trolox as a known antioxidant for reference in the ABTS

assay | Se-APC shows

clearly superior antioxidant and cytoprotective properties compared

to native APC in vitro. It effectively scavenges radicals,

protects erythrocytes from oxidative hemolysis, and preserves

cellular antioxidant defenses, making it a promising candidate for

functional food or therapeutic applications targeting oxidative

stress-related damage. | (28) |

| Chen, 2008 | Aim: Evaluate the

antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of Se-PC. Cell line:

A375, MCF-7, erythrocytes, Hs68 | NA | A375 and MCF-7:

Control: Cells no treated. Se-PC: Cells treated with Se-PC at

varying concentrations (5, 10, 20 and 40 µM) and incubated for 72 h

to evaluate antiproliferative effects and for 24 h for apoptosis

assays.PCs: Cells treated with phycocyanin (PC) at the same

concentrations as Se-PC for comparison and incubated for 72 h to

evaluate antiproliferative effects and for 24 h for apoptosis

assays. Erythrocytes from Sprague-Dawley rats: Control: Cells

exposed to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). AAPH: Cells treated

with 200 mM AAPH for 3 h. AAPH + Se-PC: Cells pre-treated with

Se-PC for 30 min at concentrations of 0.1 to 1.25 µM, followed by

200 mM AAPH Se-PC: Cells treated with Se-PC alone for 30 min to

confirm its non-toxic effects. | Selenium

incorporation into phycocyanin enhances both antioxidant and

antiproliferative activities in vitro. Se-PC outperformed

native PC across all assays, confirming its potential as a

selenium-based chemopreventive agent. | (27) |

| Riss, 2007 | Aim: Evaluate the

cardiovascular and oxidative stress protective effects of Se-PC

derived from Se-SP in the context of atherogenesis. Animal model:

Male Golden Syrian hamsters. | Control: Hamsters

received tap water. PC: Hamsters received native phycocyanin at a

dose of 3.63 mg/day per 100 g bw in water for 12 weeks. Se-PC:

Hamsters received Se-PC at a dose of 3.63 mg/day per 100 g bw for

12 weeks, providing 0.4 µg selenium per 100 g bw. SP: Hamsters

received crude SP at a dose of 2.66 mg/day per 100 g bw in water

for 12 weeks. Se-SP: Hamsters received Se-SP at a dose of 2.66

mg/day per 100 g bw for 12 weeks, providing 0.4 µg selenium per 100

g bw. | NA | Se-PC demonstrated

the most potent antioxidant and anti-atherogenic effects in

vivo, significantly reducing oxidative stress markers and

improving lipid profiles. Although PC and Se-SP showed beneficial

effects, Se-PC was the most effective in modulating NADPH oxidase

expression and plasma antioxidant capacity. | (26) |

Results and Discussion

Included studies

A total of 103 reports were identified, of which 62

articles were excluded due to duplications, 10 articles were

excluded as the full text was not available, 18 articles were out

of the scope and one article was published in Chinese. The

remaining 12 eligible articles were included in the systematic

review (Table I).

Se-SP

Se-SP is a biofortified form of the well-known

microalga, enhanced with selenium to boost its antioxidant and

protective properties (17). This

enriched form combines the natural benefits of Spirulina with the

potent biological activity of selenium, rendering it a promising

agent for health applications involving oxidative stress

management, immune support and cellular protection (18).

The protective effects of Se-SP against

alcohol-induced liver damage were evaluated in a study involving

HL7702 human liver cells and mice exposed to subacute alcohol

injury (19). In that study, in

vitro experiments revealed that Se-SP significantly alleviated

ethanol-related cytotoxicity in a concentration-dependent manner.

Compared to native SP, Se-SP was more effective in maintaining cell

viability, lowering the intracellular levels of reactive oxygen

species (ROS) and malondialdehyde (MDA), and boosting the activity

of key antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and

glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px or GPx). Se-SP also preserved

mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and reduced apoptosis, as

reflected by the lower expression of pro-apoptotic markers (Bax and

cleaved caspase-3) and higher levels of the anti-apoptotic protein,

Bcl-2. While SP also exhibited some antioxidant and cytoprotective

effects, its overall efficacy was consistently lower than that of

Se-SP (19). In vivo, mice

receiving 200 mg/kg Se-SP over a period of 42 days exhibited marked

improvement in biochemical indicators of liver injury. Serum

alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels were

significantly reduced compared to the alcohol-only group and

remained closer to physiological ranges than in animals treated

with SP. Similarly, Se-SP was more effective in normalizing lipid

profiles, including total cholesterol (TC) and triglycerides,

without overshooting the normal values, an effect observed with SP

in some parameters. Se-SP also provided superior control over

oxidative stress. The activity of SOD and GSH-Px was more

significantly enhanced, and the MDA levels were more effectively

suppressed in the Se-SP-treated animals than in those treated with

SP (19). The histological

examination of liver tissues further confirmed these findings:

Se-SP more effectively preserved hepatic architecture and reduced

necrosis and inflammatory infiltration. Immunohistochemical

analyses revealed that Se-SP downregulated the levels of key

markers of apoptosis (caspase-9), autophagy (LC3) and pyroptosis

(caspase-1) more efficiently than SP. These findings underscore the

superior protective effects of Se-SP against alcohol-induced liver

cell injury, demonstrating greater efficacy than native Spirulina

in reducing apoptosis, autophagy and pyroptosis, while enhancing

antioxidant enzyme activity. Se-SP emerges as a promising dietary

supplement for the prevention and management of oxidative liver

damage (19).

The in vitro protective effects of Se-SP

against cisplatin-induced apoptosis were also previously

investigated (20). Cisplatin

exposure induced a dose-dependent increase in both early and late

apoptosis, accompanied by significant mitochondrial dysfunction,

opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP)

and the excessive production of ROS. Pre-treatment with Se-SP

effectively mitigated these cytotoxic effects by preserving MMP and

restoring the balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic members of

the Bcl-2 family. This mitochondrial stabilization limited MPTP

opening and prevented the activation of the intrinsic apoptotic

cascade. Additionally, Se-SP markedly reduced ROS production and

superoxide anion levels, enhanced the activity of endogenous

antioxidant systems, such as SOD and GSH-Px, and protected cellular

DNA from oxidative damage (20).

At the molecular level, Se-SP pre-treatment suppressed the cleavage

of PARP and reduced the activation of caspase-3, caspase-7 and

caspase-9, key mediators of apoptosis. It also inhibited the

phosphorylation of DNA damage response proteins, including ataxia

telangiectasia mutated, ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related, and

tumor protein p53, confirming its role in attenuating oxidative

stress-driven apoptotic signaling (20). By contrast, SP without selenium

enrichment did not provide significant protection under the same

experimental conditions. SP pre-treatment failed to improve cell

viability, did not reduce apoptosis, and had negligible effects on

oxidative markers. This direct comparison highlights the

substantial enhancement of biological activity conferred by

selenium incorporation. In summary, Se-SP displayed a markedly

superior protective profile compared to its non-enriched

counterpart, demonstrating its potential as an effective adjuvant

in preventing cisplatin-induced oxidative damage and mitochondrial

dysfunction in bone-forming cells (20).

The protective effects and underlying mechanisms of

Se-SP against high glucose-induced calcification in mouse aortic

vascular smooth muscle cells was also examined in a previous study

(21). Exposure to elevated

glucose concentrations led to significant oxidative stress,

increased ROS production and DNA damage, all contributing to

pathological calcification in vascular tissues. Pre-treatment with

Se-SP significantly mitigated these effects by reducing ROS

accumulation and limiting oxidative DNA injury (21). In addition, Se-SP modulated key

intracellular signaling cascades involved in the calcification

process. Specifically, it suppressed the overactivation of the

mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and prevented the

inhibition of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B

(PI3K/AKT) pathway, thereby preserving cell homeostasis and

inhibiting pro-calcific responses. When compared to native SP,

Se-SP exhibited markedly greater efficacy. SP alone exhibited only

modest antioxidant activity and did not significantly affect either

MAPK or PI3K/AKT signaling under high-glucose conditions (21). Conversely, Se-SP not only reduced

oxidative stress more effectively, but also provided broader

cytoprotective effects by interfering with multiple

calcification-related molecular pathways. Overall, Se-SP

demonstrated superior protective effects against glucose-induced

vascular damage compared to SP, emphasizing the added value of

selenium enrichment in enhancing the bioactivity of SP. These

findings support the potential application of Se-SP in the

prevention of vascular complications associated with diabetes and

metabolic disorders (21).

The neuroprotective potential of Se-SP was further

evaluated in a study examining its effects against damage induced

by oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) in hippocampal neurons

harvested from neonatal rats (22). Se-SP treatment significantly

improved neuronal viability under OGD conditions. Neurons treated

with 10 µg/ml Se-SP exhibited a marked increase in viability, which

increased from 57.2 to 94.5%, whereas treatment with SP alone did

not provide significant protection (22). Se-SP also substantially reduced

OGD-induced neuronal apoptosis, as evidenced by a decrease in the

number of TUNEL-positive cells from 45.6 to 6.3%. Furthermore,

Se-SP inhibited the accumulation of ROS induced by OGD, improved

MMP and modulated the expression of Bcl-2 family proteins,

effectively maintaining a balance between pro-apoptotic and

anti-apoptotic factors (22).

These findings suggest that Se-SP exerts superior antioxidant and

cytoprotective effects compared to SP alone, effectively reducing

ROS production, preserving mitochondrial function, and preventing

neuronal apoptosis under OGD conditions. Thus, Se-SP has promising

neuroprotective effects, suggesting its potential as an

intervention to support neuronal survival and prevent damage

associated with ischemic events (22).

The potential of Se-SP to enhance health outcomes

has been investigated vs. its role in managing severe conditions

such as sepsis. Notably, its efficacy was assessed in an in

vivo study involving selenium-deficient female rats (23). That study found that rats treated

with Se-SP or sodium selenite (SS) exhibited significantly longer

survival times compared to those that received standard SP.

Specifically, rats supplemented with Se-SP demonstrated increased

plasma selenium levels and longer survival post-sepsis induction,

highlighting the beneficial role of selenium-enriched

supplementation. Se-SP treatment led to a significant increase in

the levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, whereas other

treatment groups exhibited lower levels. Elevated levels of the

pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and TNF-α, were observed in most

groups following sepsis induction; however, the Se-SP group

maintained a more balanced cytokine response (23). Although Se-SP improved metabolic

stability and acid-base balance, the treatment did not fully

prevent sepsis-related mortality. These results suggest that while

Se-SP exhibits potential in enhancing survival and modulating

inflammatory responses during sepsis, its effectiveness in fully

combating severe sepsis remains limited (23). Overall, SS remains the most

effective option in correcting selenium deficiency and mitigating

sepsis-induced oxidative and metabolic disturbances. Although Se-SP

exhibits promise in upregulating antioxidant genes, it fails to

deliver functional protection in the acute setting, likely due to

lower bioavailability of organic Se forms (e.g., SeMet) or matrix

interactions. Spirulina, while theoretically antioxidant, offered

no protective effect and may even exacerbate early stress responses

in sepsis (23).

The effects of SP, Se-SP and SS on restoring

selenium levels and antioxidant defenses were also investigated in

another study involving 32 female Wistar rats fed a

selenium-deficient diet over a 12-week period (24). Se-SP supplementation effectively

restored selenium concentrations in the majority of tissues, such

as the liver and kidneys, outperforming SS. While Se-SP increased

GPx activity in some tissues, SS was more effective in enhancing

SOD activity, particularly in the heart. Additionally, Se-SP

restored the expression levels of certain selenoproteins in a

tissue-dependent manner, whereas SS had a more pronounced impact on

GPx1 expression in the heart. Se-SP ensured better selenium

distribution and tissue bioavailability, while SS more effectively

enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity and certain selenoprotein

expressions. Spirulina alone exhibited only marginal antioxidant

benefits without selenium repletion (24).

The anti-osteoporotic efficacy of

selenium-containing protein extracted from Se-SP, using both in

vitro and in vivo models was also previously

investigated (25). In

vitro, MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells were treated with 5 and

10 µg/ml of either Se-SP or non-enriched SP for 14 days. In

vivo, ovariectomized female mice were divided into four groups

as follows: The sham-operated, untreated ovariectomized SP-treated

(10 mg/kg) and Se-SP-treated (10 mg/kg) mice, with treatment

administered intraperitoneally every other day for 2 months

(25). That study found that Se-SP

enhanced calcium deposition, alkaline phosphatase activity and the

expression of osteoblastic markers (BMP2, RUNX2, COL-I and OCN),

while also reducing osteoclastogenesis (TRAcP and RANKL) and

promoting anti-inflammatory cytokine production (IL-4 and IL-10).

Compared to SP alone, Se-SP demonstrated superior efficacy in

reversing bone loss and restoring bone microarchitecture in

ovariectomized mice (25).

Se-PC

Se-PC, a compound derived from Se-SP, has attracted

marked interest for its potent antioxidant and anticancer

properties. This bioactive molecule combines the well-known

benefits of phycocyanin with the enhanced activity provided by

selenium, an essential trace element known for its antioxidant

capabilities. The studies identified in the literature collectively

highlight the diverse and significant biological activities of

Se-PC and its potential applications in various health and

therapeutic contexts. The cardiovascular and oxidative stress

protective effects of Se-PC derived from SP was first studied in

the context of atherogenesis (26). In that study conducted in

vivo on male Golden Syrian hamsters, Se-PC demonstrated

significant lipid-lowering and antioxidant effects. Se-PC reduced

plasma TC levels by 10%, outperforming native phycocyanin (PC),

which achieved a 7.5% reduction. Additionally, Se-PC significantly

decreased non-HDL cholesterol levels by 34%, a more pronounced

effect compared to PC. As regards oxidative stress markers, Se-PC

restored plasma antioxidant capacity to near-normal levels, showing

a 42% improvement over the control group, while PC, SP and Se-SP

were effective to a lesser extent (26). In cardiac tissue, Se-PC reduced

superoxide anion production by 76%, significantly exceeding the

reductions achieved by PC (54%) and spirulina variants (46-56%). In

liver tissues, GSH-Px and SOD activities were lower in all

treatment groups compared to the controls, suggesting a potential

‘sparing effect’ of the exogenous antioxidants provided by Se-PC

and PC. These results highlight the superior efficacy of Se-PC in

modulating lipid metabolism and reducing oxidative stress (26). Se-PC demonstrated the most potent

antioxidant and anti-atherogenic effects in vivo,

significantly reducing oxidative stress markers and improving lipid

profiles. Although PC and Se-SP exerted beneficial effects, Se-PC

was the most effective in modulating NADPH oxidase expression and

plasma antioxidant capacity (26).

The in vitro antioxidant and

antiproliferative activities of Se-PC were investigated in another

study with the aim of examining its role in inducing the apoptosis

of human melanoma cells (A375), human breast adenocarcinoma cells

(MCF-7) and human fibroblasts (Hs68) (27). The findings of that study revealed

that Se-PC significantly increased the percentage of depolarized

mitochondria in A375 cells from 11.6% in the control group to 39.0

and 54.7% at the 10 and 20 µM concentrations, respectively. A

similar trend was observed in MCF-7 cells, where the percentage of

depolarized mitochondria increased from 1.3% in the control to 13.2

and 20.9% at the same concentrations (27). These results suggest that Se-PC

induces apoptosis via a mitochondria-mediated pathway. Furthermore,

Se-PC demonstrated potent antioxidant properties, inhibiting

2,2'-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate) (ABTS)

oxidation by 18.8% at 0.5 µM and 46.0% at 1.0 µM. This performance

surpassed that of regular PC, which exhibited inhibition rates of

11.7 and 31.1% at the same concentrations. Furthermore, both Se-PC

and PC led to a significantly greater inhibition of ABTS oxidation

compared to ascorbic acid and Trolox (27). Another significant finding was the

scavenging activity of Se-PC against superoxide anions, which are

biologically crucial due to their potential to decompose into more

reactive oxidative species, such as singlet oxygen and hydroxyl

radicals. That study found that Se-PC and PC inhibited superoxide

anions in a concentration-dependent manner over a range of 1-16 µM.

Additionally, Se-PC demonstrated protective effects against

H2O2-induced DNA damage. While the control

group treated with H2O2 alone exhibited DNA

damage, no significant DNA damage was observed in groups treated

with Se-PC at concentrations of 10 or 50 µM. Notably, Se-PC was

found to be a non-genotoxic compound (27). In summary, Se-PC exhibited superior

antioxidant activities compared to PC by effectively neutralizing

ABTS, superoxide anion, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and

2,2'-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AAPH) free

radicals. It also exerted protective effects against

H2O2-induced DNA damage in blood cells. The

most noteworthy effect of Se-PC was its ability to inhibit cell

growth in A375 melanoma and MCF-7 breast adenocarcinoma cells,

primarily by inducing mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. Overall,

Se-PC outperformed native PC across all assays, confirming its

potential as a selenium-based chemopreventive agent (27).

In another study in vitro, the protective

effects of Se-PC were evaluated against oxidative stress induced by

AAPH (28). Specifically, that

study explored the ability of selenium-enriched allophycocyanin

(Se-APC) to inhibit ROS generation, prevent lipid peroxidation and

protect antioxidant defense systems in human erythrocytes. Se-APC

demonstrated superior antioxidant activity compared to regular APC,

as evidenced by its significantly higher inhibition of ABTS

radicals. It also exhibited protective effects against hemolysis,

reducing AAPH-induced hemolysis in erythrocytes in a dose-dependent

manner. Additionally, Se-APC effectively inhibited lipid

peroxidation, significantly decreasing MDA formation and restoring

levels to near control values at a concentration of 1.5 µM.

Furthermore, Se-APC protected against ROS generation, reducing ROS

levels to 195% at 0.3 µM and returning them to near control levels

at 1.5 µM (28). Finally, Se-APC

preserved the antioxidant defense system by significantly restoring

GSH levels in a concentration-dependent manner. It also prevented

the increase in GPx and GSH reductase activities, maintaining their

levels comparable to controls when used at 1.5 µM. Se-APC exhibited

clearly superior antioxidant and cytoprotective properties compared

to native APC in vitro. It effectively scavenged radicals,

protected erythrocytes from oxidative hemolysis and preserved

cellular antioxidant defenses, rendering it a promising candidate

for functional food or therapeutic applications targeting oxidative

stress-related damage (28).

The therapeutic potential of Se-PC in enhancing the

efficacy of photodynamic therapy (PDT) for cancer treatment was

evaluated both in vitro and in vivo (29,30).

In vitro experiments conducted on Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC)

cells demonstrated that Se-PC PDT resulted in significantly higher

levels of ROS compared to PC PDT or PC-SS PDT, indicating an

enhanced induction of oxidative stress within the cancer cells

(30). Furthermore, Se-PC PDT

treatment led to significantly reduced cell survival rates compared

to PC PDT alone, highlighting its superior efficacy in targeting

LLC cells. Se-PC represented the most effective and balanced

treatment, providing potent cytotoxicity against tumor cells, while

preserving antioxidant defenses in normal tissues and minimizing

systemic toxicity. Its dual action on tumor inhibition and immune

activation rendered it the most promising strategy among the three

approaches evaluated (30). In a

study conducted on HepG2 cells (human liver cancer cells) and

HL7702 cells (normal human liver cells), Se-PC photodynamic therapy

(Se-PC PDT) demonstrated selective cytotoxicity, significantly

reducing cell viability in HepG2 cells while sparing HL7702 cells

(29). The treatment markedly

increased intracellular ROS levels in HepG2 cells, leading to

oxidative damage and apoptosis, which was significantly more

pronounced in the Se-PC PDT group compared to the PC PDT group.

This selective induction of apoptosis highlights the potential of

Se-PC PDT as a targeted therapeutic approach against liver cancer

cells, while minimizing damage to normal liver cells (29).

In vivo, using lung carcinoma-bearing male

C57BL/6 mice, Se-PC PDT demonstrated notable efficacy with a tumor

inhibition rate of 90.1%, significantly higher than the PC PDT

group (53.1%) and the PC-SS PDT group (68.3%) (30). Se-PC PDT also inhibited metastasis,

as evidenced by reduced luminescence in major organs, such as the

liver and lungs. The treatment enhanced antioxidant defense

mechanisms, increasing the activities of SOD and GSH-Px in liver

and lung tissues, while maintaining lower levels of MDA, an

oxidative stress marker, compared to the PC-SS PDT group,

indicating reduced damage to normal tissues. Additionally, Se-PC

PDT significantly elevated serum levels of IL-6 and TNF-α,

suggesting an enhanced immune response. Mechanistically, Se-PC PDT

induced both apoptosis and pyroptosis in tumor cells, with gene

expression analysis revealing the upregulation of caspase-1,

caspase-3 and caspase-9, alongside the reduced expression of the

anti-apoptotic marker, Bcl-2. Furthermore, Se-PC PDT modulated

critical signaling pathways, including NF-κB, IL-17 and HIF-1,

involved in inflammation, tumor metabolism and immune responses.

The treatment also downregulated genes associated with angiogenesis

and tumor progression, such as Vegfa, Mmp13, and Serpine1,

highlighting its multifaceted anti-tumor effects (30). In a study conducted on BALB/c mice,

the Se-PC PDT group exhibited the most significant reduction in

tumor volume and weight compared to all other groups (29). This treatment also effectively

decreased oxidative stress markers, such as MDA, while enhancing

the activity of antioxidant enzymes, including SOD and GSH-Px, in

tumor tissues. Additionally, the Se-PC PDT group exhibited a marked

increase in apoptosis within tumor cells, highlighting its potent

antitumor and antioxidative effects (30). These findings collectively

emphasize Se-PC combined with PDT induces potent anticancer

activity through mitochondria-mediated apoptosis, partial

inhibition of autophagy, and enhanced antioxidant enzyme

modulation. It demonstrates stronger efficacy and higher tumor

selectivity than PC alone, offering a promising and safer strategy

for liver tumor therapy (30).

In conclusion, the present systematic review

provides robust evidence that selenium enrichment significantly

enhances the biological efficacy of both SP and its key

pigment-protein complex, phycocyanin extracted from Se-SP, across a

wide range of experimental settings. Compared to their native

counterparts, both Se-SP and Se-PC consistently show superior

antioxidant, cytoprotective, anti-inflammatory, and in some cases,

anticancer activities.

Specifically, Se-SP exhibits markedly more potent

protective effects than SP alone, as demonstrated in models of

alcohol-induced liver damage, cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity, high

glucose-induced vascular calcification, and oxygen-glucose

deprivation in neurons. Se-SP improves mitochondrial function,

reduces oxidative markers (e.g., ROS and MDA), enhances antioxidant

enzyme activity (e.g., SOD and GPx), and modulates

apoptosis-related pathways more effectively than non-enriched

Spirulina. Notably, the superiority of Se-SP emerges most clearly

in models of hepatic injury, neuroprotection and bone loss, where

its selenium-mediated modulation of signaling pathways plays a

decisive role. However, Se-SP appears less bioavailable and less

effective than inorganic selenium (e.g., SS) in acute systemic

conditions such as sepsis, limiting its applicability in urgent or

high-burden clinical contexts.

Likewise, Se-PC significantly outperforms native PC

in antioxidant capacity, radical scavenging activity, mitochondrial

protection and selective cytotoxicity in cancer models. In

particular, Se-PC demonstrates enhanced efficacy in PDT for cancer,

exerting dual effects of tumor apoptosis and immune activation

while maintaining low systemic toxicity. Compared to PC, Se-PC more

potently modulates oxidative stress, preserves redox homeostasis,

and activates apoptosis-related gene pathways, making it a

promising candidate for targeted therapeutic strategies,

particularly in oncology.

Despite the compelling results, the available

literature presents several limitations, including the scarcity of

direct comparative studies between Se-SP and Se-PC, and between

these selenium-enriched compounds and conventional selenium forms

or combinatorial strategies. Variability in enrichment protocols,

dosage regimens, and biological models further complicates

comparative interpretation.

Future research is required to prioritize direct

head-to-head comparisons of Se-SP vs. Se-PC under standardized

conditions, both to elucidate their mechanistic divergences and to

optimize their use in specific pathological contexts. Long-term

in vivo studies and clinical trials will be crucial for

validating safety profiles, bioavailability, and dose-response

relationships. Exploring combinatorial therapies and synergistic

interactions with other bioactive may further expand their

application in preventive and functional nutrition, as well as in

integrative medicine.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Ministry of

University and Research (MUR) as part of the FSE REACT-EU-PON

2014-2020 ‘Research and Innovation’ resources-Green/Innovation

Action-DM MUR 1062/2021-Title of the Research ‘GrEEnoncoprev’. The

present study was also supported by the Department of Medical,

Surgical and Advanced Technologies ‘G.F. Ingrassia’, University of

Catania, Italy.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

CS conceptualized the study. CS, CF and CC were

involved in the study methodology. CS, CF, CC, PR carried out the

search and screening of the articles for inclusion in the

systematic review. For the records whose inclusion was in doubt, a

focus group was carried out with MF, GOC and MC. The focus group

approved the final eligibility of records. PR validated the

methodological approach. CC, GOC, and MC were involved in assessing

the risk of bias for the articles screening. CF, PR, MC, MF, and

GOC were involved in data curation, writing and preparation of the

original draft of the manuscript. CC, GOC, MF and MC reviewed and

edited the final draft of manuscript. MF and GOC, supervised, and

edited the final draft. GOC and MF confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Leong YK and Chang JS: Integrated role of

algae in the closed-loop circular economy of anaerobic digestion.

Bioresour Technol. 360(127618)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Copat C, Favara C, Tomasello MF, Sica C,

Grasso A, Dominguez HG, Conti GO and Ferrante M: Astaxanthin in

cancer therapy and prevention (review). Biomed Rep.

22(66)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Gutiérrez-Salmeán G, Fabila-Castillo L and

Chamorro-Cevallos G: Nutritional and toxicological aspects of

spirulina (Arthrospira). Nutr Hosp. 32:34–40. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zakaria SM and Kamal SMM: Subcritical

water extraction of bioactive compounds from plants and algae:

Applications in pharmaceutical and food ingredients. Food Eng Rev.

8:23–34. 2016.

|

|

5

|

Abdel-Moneim AME, El-Saadony MT, Shehata

AM, Saad AM, Aldhumri SA, Ouda SM and Mesalam NM: Antioxidant and

antimicrobial activities of Spirulina platensis extracts and

biogenic selenium nanoparticles against selected pathogenic

bacteria and fungi. Saudi J Biol Sci. 29:1197–1209. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Maddiboyina B, Vanamamalai HK, Roy H,

Ramaiah null, Gandhi S, Kavisri M and Moovendhan M: Food and drug

industry applications of microalgae Spirulina platensis: A

review. J Basic Microbiol. 63:573–583. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Khan Z, Bhadouria P and Bisen PS:

Nutritional and therapeutic potential of Spirulina. Curr Pharm

Biotechnol. 6:373–379. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Pak W, Takayama F, Mine M, Nakamoto K,

Kodo Y, Mankura M, Egashira T, Kawasaki H and Mori A:

Anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects of spirulina on rat

model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Biochem Nutr.

51:227–234. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zhang Y, Li L, Qin S, Yuan J, Xie X, Wang

F, Hu S, Yi Y and Chen M: C-phycocyanin alleviated

cisplatin-induced oxidative stress and inflammation via gut

microbiota-metabolites axis in mice. Front Nutr.

9(996614)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Li X, Ma L, Zheng W and Chen T: Inhibition

of islet amyloid polypeptide fibril formation by

selenium-containing phycocyanin and prevention of beta cell

apoptosis. Biomaterials. 35:8596–8604. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Surai PF, Fisinin VI and Karadas F:

Antioxidant systems in chick embryo development. Part 1. Vitamin E,

carotenoids and selenium. Anim Nutr. 2:1–11. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Wu Q, Liu L, Miron A, Klímová B, Wan D and

Kuča K: The antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory

activities of Spirulina: an overview. Arch Toxicol. 90:1817–1840.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Tajvidi E, Nahavandizadeh N, Pournaderi M,

Pourrashid AZ, Bossaghzadeh F and Khoshnood Z: Study the

antioxidant effects of blue-green algae Spirulina extract on ROS

and MDA production in human lung cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Rep.

28(101139)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Han P, Li J, Zhong H, Xie J, Zhang P, Lu

Q, Li J, Xu P, Chen P, Leng L and Zhou Z: Anti-oxidation properties

and therapeutic potentials of spirulina. Algal Res.

55(102240)2021.

|

|

15

|

Yang F, Tang Q, Zhong X, Bai Y, Chen T,

Zhang Y, Li Y and Zheng W: Surface decoration by Spirulina

polysaccharide enhances the cellular uptake and anticancer efficacy

of selenium nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 7:835–844.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Alipour S, Kalari S, Morowvat MH, Sabahi Z

and Dehshahri A: Green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles by

cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis (abdf2224): Cultivation

condition quality controls. BioMed Res Int.

2021(6635297)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Menon S, Ks SD, R S, S R and S VK:

Selenium nanoparticles: A potent chemotherapeutic agent and an

elucidation of its mechanism. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces.

170:280–292. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Pires R, Costa M, Pereira H, Cardoso H,

Ferreira L, Lapa N, Silva J and Ventura M: Microalgae as a selenium

vehicle for nutrition: A review. Discov Food. 4(84)2024.

|

|

19

|

Fu X, Zhong Z, Hu F, Zhang Y, Li C, Yan P,

Feng L, Shen J and Huang B: The protective effects of

selenium-enriched Spirulina platensis on chronic

alcohol-induced liver injury in mice. Food Funct. 9:3155–3165.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Sun JY, Hou YJ, Fu XY, Fu XT, Ma JK, Yang

MF, Sun BL, Fan CD and Oh J: Selenium-containing protein from

selenium-enriched Spirulina platensis attenuates

cisplatin-induced apoptosis in MC3T3-E1 mouse preosteoblast by

inhibiting mitochondrial dysfunction and ros-mediated oxidative

damage. Front Physiol. 9(1907)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Lin C, Zhang LJ, Li B, Zhang F, Shen QR,

Kong GQ, Wang XF, Cui SH, Dai R, Cao WQ and Zhang P:

Selenium-containing protein from selenium-enriched Spirulina

platensis attenuates high glucose-induced calcification of

MOVAS cells by inhibiting ROS-mediated DNA damage and regulating

MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways. Front Physiol. 11(791)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Song X, Zhang L, Hui X, Sun X, Yang J,

Wang J, Wu H, Wang X, Zheng Z, Che F and Wang G:

Selenium-containing protein from selenium-enriched Spirulina

platensis antagonizes oxygen glucose deprivation-induced

neurotoxicity by inhibiting ROS-mediated oxidative damage through

regulating MPTP opening. Pharm Biol. 59:629–638. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Castel T, Theron M, Pichavant-Rafini K,

Guernec A, Joublin-Delavat A, Gueguen B and Leon K: Can

selenium-enriched spirulina supplementation ameliorate sepsis

outcomes in selenium-deficient animals? Physiol Rep.

9(e14933)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Castel T, Léon K, Gandubert C, Gueguen B,

Amérand A, Guernec A, Théron M and Pichavant-Rafini K: Comparison

of sodium selenite and selenium-enriched spirulina supplementation

effects after selenium deficiency on growth, tissue selenium

concentrations, antioxidant activities, and selenoprotein

expression in rats. Biol Trace Elem Res. 202:685–700.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Yang Y, Yang H, Feng X, Song Q, Cui J, Hou

Y, Fu X and Pei Y: Selenium-containing protein from

selenium-enriched Spirulina platensis relieves osteoporosis

by inhibiting inflammatory response, osteoblast inactivation, and

osteoclastogenesis. J Food Biochem. 2024(3873909)2024.

|

|

26

|

Riss J, Décordé K, Sutra T, Delage M,

Baccou JC, Jouy N, Brune JP, Oréal H, Cristol JP and Rouanet JM:

Phycobiliprotein C-phycocyanin from Spirulina platensis is

powerfully responsible for reducing oxidative stress and NADPH

oxidase expression induced by an atherogenic diet in hamsters. J

Agric Food Chem. 55:7962–7967. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chen T and Wong YS: In vitro antioxidant

and antiproliferative activities of selenium-containing phycocyanin

from selenium-enriched Spirulina platensis. J Agric Food

Chem. 56:4352–4358. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Zhang H, Chen T, Jiang J, Wong YS, Yang F

and Zheng W: Selenium-containing allophycocyanin purified from

selenium-enriched Spirulina platensis attenuates

AAPH-induced oxidative stress in human erythrocytes through

inhibition of ROS generation. J Agric Food Chem. 59:8683–8690.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Liu Z, Fu X, Huang W, Li C, Wang X and

Huang B: Photodynamic effect and mechanism study of

selenium-enriched phycocyanin from Spirulina platensis

against liver tumours. J Photochem Photobiol B. 180:89–97.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Shen J, Xia H, Zhou X, Zhang L, Gao Q, He

K, Liu D and Huang B: Selenium enhances photodynamic therapy of

C-phycocyanin against lung cancer via dual regulation of

cytotoxicity and antioxidant activity. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin

(Shanghai). 55:1925–1937. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|