Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) refers to

neurodevelopmental disorders marked by significant challenges in

socialization, communication and behavior (1). A previous systematic review of 71

studies included sample sizes which were relatively large, ranging

from 465 to 50 million participants. Prevalence in these studies

ranged from 1.09/10,000 to 436/10,000, with a median majority of

100/10,000(2). Notably, the

reported prevalence of ASD among children has increased over time.

This may be attributable to several factors, including a broadening

of the diagnostic criteria, heightened public awareness of ASD and

its symptoms, and the enhanced availability of early interventions

and educational services tailored for children with ASD (3).

Sociodemographic factors, such as socio-economic

status, parental education and cultural background significantly

affect the development, diagnosis and management of ASD in

children. Studies from Australia and Bangladesh have highlighted

how parental education, occupation and cultural background

influence ASD diagnoses and access to services, emphasizing the

need for equitable healthcare policies and intervention programs

tailored to diverse needs (4,5).

Understanding these factors is essential for ensuring access to

support services for all children with ASD, regardless of

sociodemographic background.

Medical comorbidities are more common in children

with ASD than in the general population. For instance, children

with ASD are more likely to develop various neurological disorders,

including epilepsy, macrocephaly, migraines/headaches and

congenital abnormalities of the nervous system (6). Additionally, the risk of falls is

strongly prevalent in such children. This may be due to cognitive

and motor impairments that increase the risk of falls. The high

rate of non-fatal falls, the associated healthcare costs and the

significant risk of mortality (particularly as a result of head

injuries) render it essential to prioritize the prevention of

fall-related injuries in child safety efforts worldwide (7).

Numerous risk and protective factors for falls among

children have been reported, including sociodemographic

characteristics, maternal psychiatric disorders, and child

psychological and behavioral issues (8). A previous study employing

multivariate logistic regression analyzes identified significant

predictors of falls, such as an age <3 years, neurological

diagnosis (including epilepsy), dependency in activities of daily

living, physical developmental delay and multiple usage of

fall-risk-increasing drugs (9).

Antipsychotic medications are the agents most critically studied as

treatments for reducing symptoms. However, such medications can

increase the risk of falls due to syncope, sedation, slowed

reflexes, loss of balance and impaired psychomotor function

(9). Moreover, the administration

of antipsychotic medications requires careful monitoring due to

associated safety concerns and the potential for extended

utilization (10).

Interventions in general predominantly focus on

reducing ASD-specific symptoms, mitigating concurrent issues, and

enhancing overall quality of life (11). Notably, early interventions

demonstrate considerable efficacy, significantly improving outcomes

across domains (12). In Saudi

Arabia, children begin treatment at 3.3 years of age, whereas in

the USA, treatment is commenced at 2.2 years of age, indicating

delayed intervention in Saudi Arabia. Utilizing an online survey

methodology with a sample size of ~200 participants, a study

conducted >6 years prior highlighted the need for a

comprehensive investigation into the prevalence of ASD and related

services within the Saudi community (13).

This underscores the necessity of identifying and

implementing suitable interventions tailored to children with ASD

from different age groups, thus ensuring timely and effective

support mechanisms. In Saudi Arabia, to the best of our knowledge,

no study has yet evaluated the pediatric risk of falls among

children with ASD. To fill this gap in the research literature, the

present study examined the ASD profile through an analysis of

sociodemographic variables, the type of medications children with

ASD receive, and the presence of comorbidities. The present study

also conducted a correlational analysis to evaluate the risk of

falls among different age groups.

Patients and methods

Study participants

The sample size was determined using G*Power

software (http://www.gpower.hhu.de/). A priori

power analysis for a two-tailed correlation indicated that the

minimum sample size needed to yield a statistical power of 0.95

with an α value of 0.05 and a medium effect size (Cohen's d=0.5) is

134. For an independent samples Student's t-test, a minimal sample

size of 210 is required. Furthermore, a minimum of 172 participants

are required for a linear regression model with 10 predictor

variables, while 66 participants are required for a repeated

measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The sample for the present

study comprised 250 autistic children attending the Psychology

Clinic at King Khalid University Hospital (KSUM) in Riyadh, Saudi

Arabia. This hospital operates under King Saud University.

Therefore, the sample size was appropriate. The sample included

children diagnosed with ASD from January, 2015 to the end of

October, 2023. All the children had received multidisciplinary

evaluations, including diagnostic, cognitive and behavioral

assessments.

Study design and procedure

A retrospective cohort study was designed using a

healthcare digital record system known as electronic medical record

(EMR) systems to collect the data from KSUM. Ethical approval for

the study was granted by the Institutional Review Board at King

Saud University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (Ref. E-22-7451 no.

23/0175/IRB), with an issue date of March 2, 2023. The ethics

committee granted a waiver of written informed consent.

Measurements and patient

demographics

The demographic variables collected from EMR systems

included geographical regions of Saudi Arabia (Riyadh and other

regions), current age categories in three groups: Early (3-6

years), middle (7-12 years) and late (13-17 years), age at first

diagnosis, body mass index (BMI), sex (female or male), education

(public school with/without mixed classes, disability/ASD center,

others) and parents' knowledge of ASD.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics included frequencies and

percentages of survey responses for categorical variables, as well

as the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) values for continuous

data. Spearman's (RS) correlation analyses were

performed to examine the correlation between age and the number of

medications the participants received. As a sensitivity analysis, a

repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to

examine whether the number of antipsychotic and non-antipsychotic

medications taken (repeated measurement) was dependent on the

participants' age (early, middle or late childhood). The current

medications reported in the study are depicted in Data S1. In addition, supplementary the

categorization of diseases reported in children with autism is

demonstrated in Table SI and

Data S2. The effect size was

assessed using partial eta-square (η2p),

while a Bonferroni post hoc test was performed to evaluate

significant differences between particular samples.

The total study sample was divided into two groups

in terms of risk of falls, using the cut score of 12 on the Humpty

Dumpty Falls Scale (HDFS). The group with a lower risk of falls

(HDFS <12) included 176 children with ASD, whereas the group

with a higher risk of falls (HDFS ≥12) comprised 74 children with

ASD. These two groups were then compared using a Mann-Whitney U

test. The following dependent variables (considered as continuous

or ordinal data) were examined: Age at first diagnosis, current

age, BMI, number of diagnoses, number of comorbidities and number

of medications taken per person, including the number of

antipsychotics, non-antipsychotics and vitamins. Rank biserial

correlation (RBC) was performed to assess the effect size for the

Mann-Whitney U test. In addition, the total sample was divided into

three groups according to age stages during childhood: Early

(children between 3 and 6 years of age), middle (children between 7

and 12 years of age) and late (adolescents between 13 and 17 years

of age). As a sensitivity analysis, Pearson's χ2 test of

independence or Fisher's exact test were then conducted to examine

associations between pediatric risk of falls (lower vs. higher) and

the categorical variables of age, sex, education status, region of

Saudi Arabia, and parent's self-reported knowledge of ASD (answered

as either yes or no). The Phi (φ) statistic was used to assess the

effect size for bi-categorical variables (i.e., sex, region, and

knowledge), while Cramer's V was used to determine the effect size

for multi-categorical variables (i.e., age and education status) in

the χ2 test.

Finally, the contribution of demographic variables

to the risk of falls among children with ASD was examined using

linear regression. The following predictor variables were included

in the regression model: Age at first diagnosis, current age, BMI,

sex, education status, parents' knowledge about ASD, number of

diagnoses, number of comorbidities, number of antipsychotics,

non-antipsychotics and vitamins taken. Tolerance was >0.25

(ranging from 0.48 to 0.97) and the variance inflation factor (VIF)

was <3 (ranging from 1.03 to 2.19), suggesting that

multicollinearity was not an issue in the multiple regression

model. All statistical analyses were performed using JASP version

0.18.3.0 software for Windows (https://jasp-stats.org). A value of P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Characteristics of the study

sample

The demographic characteristics of the study

participants are presented in Table

I. The mean age of first ASD diagnosis was seven years, whereas

the mean current age of participants was twelve years. In terms of

sex differences, the majority of the participants were male (74.4%)

and the remainder (25.6%) were female. The average BMI was 19. The

majority of the patients with ASD were males, had attended some

schools or rehabilitation centers and resided in Riyadh. In the

majority of the families, both parents took care of the children,

and the majority of parents had knowledge about ASD. The majority

of the children had been diagnosed with ASD, and were usually

diagnosed once. Almost 39% of the children had another health

condition, usually took one medication, and often did not take any

vitamins. The study sample was divided according to the HDFS. The

group with low pediatric risk of falls (HDFS scores <12)

prevailed over those who met the criteria for a high risk of falls

(HDFS scores ≥12).

| Table ICharacteristic of the study

participants (n=250). |

Table I

Characteristic of the study

participants (n=250).

| Variable | Range/code | M/n | SD/% |

|---|

| Age at first

diagnosis | 0-15 | 7.27 | 3.4 |

| Current age | 3-22 | 11.65 | 3.85 |

|

Early

(3-6) | 0 | 30 | 12 |

|

Middle

(7-12) | 1 | 114 | 45.6 |

|

Late

(13-17) | 2 | 106 | 42.4 |

| Body mass index

(BMI) | 8.33-42.58 | 18.56 | 5.57 |

| Sex | 0-1 | 0.75 | 0.44 |

|

Female | 0 | 64 | 25.6 |

|

Male | 1 | 186 | 74.4 |

| Education

statusa | 0-1 | 0.57 | 0.5 |

|

Public

school with/without mixed classes | 1 | 71 | 28.4 |

|

Disability

and autism center | 2 | 67 | 26.8 |

|

Other | 3 | 4 | 1.6 |

|

Not

mentioned | 4 | 108 | 43.2 |

| Region of Saudi

Arabia | | | |

|

Riyadh | 0 | 181 | 72.4 |

|

Other

regions | 1 | 69 | 27.6 |

| Parents' knowledge

about autism | 0-1 | 0.28 | 0.45 |

|

Yes | 0 | 180 | 72 |

|

No | 1 | 70 | 28 |

| Current

diagnosis | | | |

|

Atypical

autism | 7 | 2.8 | |

|

Childhood

autism | 39 | 15.6 | |

|

Autism | 204 | 81.6 | |

| No. of

diagnoses | 1-3 | 1.22 | 0.45 |

|

One | 1 | 199 | 79.6 |

|

Two | 2 | 47 | 18.8 |

|

Three | 3 | 4 | 1.6 |

| No. of

comorbidities | 0-3 | 1.29 | 1 |

|

No | 0 | 59 | 23.6 |

|

One | 1 | 97 | 38.8 |

|

Two | 2 | 55 | 22.0 |

|

Three | 3 | 39 | 15.6 |

| No. of current

medications taken per person | 0-5 | 1.96 | 1.36 |

| No. of

antipsychotic drugs | 0-4 | 1.24 | 0.98 |

| No. of

non-antipsychotic drugs | 0-5 | 0.72 | 1.12 |

| No. of vitamins

taken | 0-3 | 0.64 | 0.88 |

| Humpty Dumpty Falls

Scale (HDFS) | 2-18 | 10.66 | 1.79 |

| Pediatric risk of

falls | 0-1 | 0.3 | 0.46 |

|

Low (HDFS

<12) | 0 | 176 | 70.4 |

|

High (HDFS

≥12) | 1 | 74 | 29.6 |

Prevalence and type of

comorbidity

A diagnosis of ASD was reported in 82% of the

participants, among whom childhood ASD was detected in 15.6% and

atypical ASD in 2.8%. In the study sample, the majorty of the

children with ASD (76.4%) reported a comorbidity (Table I). One additional disease (apart

from ASD) was found in 38.8% of the children, two coexisting

diseases in 22%, and three in 15.6% of the childrern (Table I). The prevalence of particular

types of coexisting diseases is presented in Table II. The most common was ADHD (46%

of the total sample), followed by intellectual disabilities

(18.4%), epilepsy (17.6%), genetic conditions (9.2%), global

developmental delay (6.4%), asthma (6.4%) and metabolic disorders

(6%). Other types of diseases were less frequent. The

categorization of particular diseases is presented in Data S2.

| Table IIFrequency of occurrence of various

types of comorbidity in the sample (n=250). |

Table II

Frequency of occurrence of various

types of comorbidity in the sample (n=250).

| Type of

comorbidity | No. of

participants | % |

|---|

| ADHD | 115 | 46.0 |

| Anxiety

disorder | 5 | 2.0 |

| Asthma | 16 | 6.4 |

| Cardiovascular

disease | 3 | 1.2 |

| Constipation | 3 | 1.2 |

| Epilepsy | 44 | 17.6 |

| Genetic

condition | 23 | 9.2 |

| Global

developmental delay | 16 | 6.4 |

| Hematological

disease | 3 | 1.2 |

| Infection | 1 | 0.4 |

| Intellectual

disability | 46 | 18.4 |

| Metabolic

disorder | 15 | 6.0 |

| Obesity | 3 | 1.2 |

| Other neurological

diseases | 10 | 4.0 |

| Others | 15 | 6.0 |

| Respiratory

disorders | 6 | 2.4 |

Type of medications taken depending on

age

On average, the participants currently took two

medications (M=1.96, SD=1.36), the number of which ranged from 0 to

5 per child (Table I).

Specifically, the majority of children used one medication (n=102,

40.8%), followed by two medications (n=56, 22.4%), three

medications (n=34, 13.6%), four medications (n=20, 8.0%), and five

medications (n=19, 7.6%). In total, 19 children (7.6%) reported not

using any medication. The frequency with which particular types of

medications were currently taken per child is presented in Table III. Participants took more

antipsychotic medications (M=1.24, SD=0.98, range 0-4) than

non-antipsychotics (M=0.72, SD=1.12, range 0-5) and vitamins

(M=0.64, SD=0.88, range 0-3).

| Table IIINo. of particular types of

medications taken currently per child. |

Table III

No. of particular types of

medications taken currently per child.

| | Antipsychotics |

Non-antipsychotics | Vitamins |

|---|

| No. of

medications | No. of

participants | % | No. of

participants | % | No. of

participants | % |

|---|

| 0 | 56 | 22.4 | 153 | 61.2 | 144 | 57.4 |

| 1 | 112 | 44.8 | 47 | 18.8 | 67 | 26.7 |

| 2 | 54 | 21.6 | 26 | 10.4 | 26 | 10.4 |

| 3 | 22 | 8.8 | 16 | 6.4 | 14 | 5.6 |

| 4 | 6 | 2.4 | 6 | 2.4 | | |

| 5 | | | 2 | 0.8 | | |

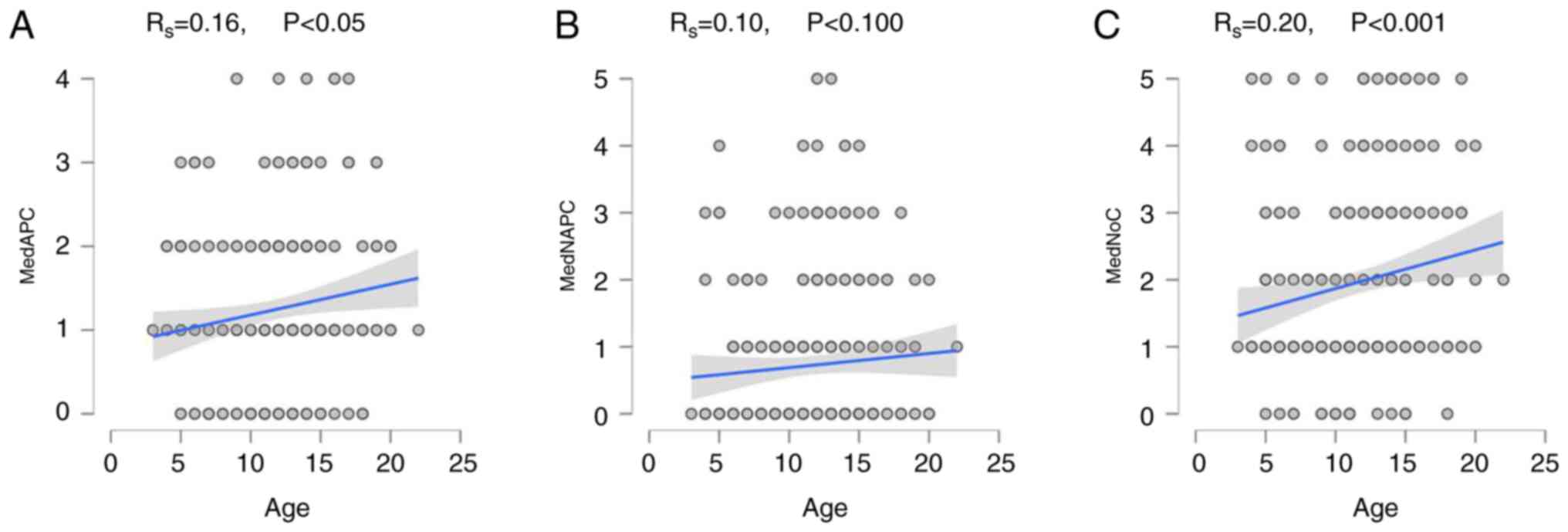

The correlation between age and the current number

of medications taken was examined using Spearman's correlation

analysis (Fig. 1). The results

revealed that the age of the children with ASD positively

correlated with the total number of medications taken

(RS=0.20, P<0.001) and antipsychotic medications used

(RS=0.16, P<0.05). Non-significant correlations were

found between age and non-antipsychotic medication use

(RS=0.10, P=0.10).

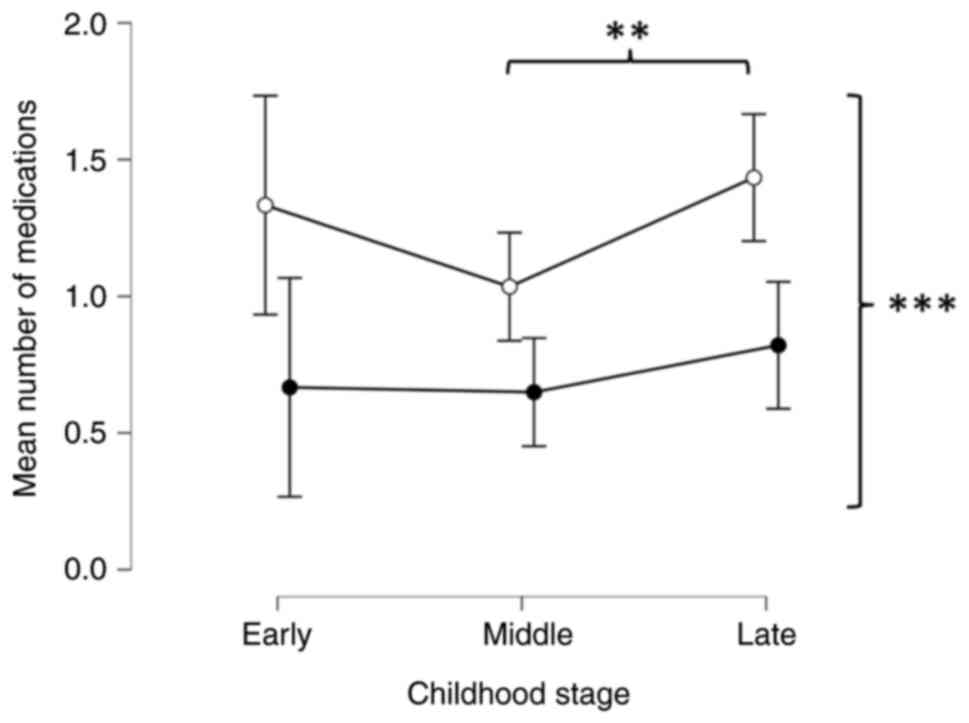

A repeated measures ANOVA was then conducted with

the type of medication (antipsychotic, non-antipsychotic) as a

dependent variable (repeated measures) and the three categories of

age during childhood (early, middle, and late) as a factor. A

significant difference was found between the mean number of

antipsychotic and non-antipsychotic medications taken

[F(1,247)=21.15, P< 0.001, η2p=0.08)]. A

Bonferroni post hoc test revealed that children with ASD used

significantly more antipsychotic medications than non-antipsychotic

(ΔM=0.56, SE=0.12, t=4.60, P<0.001). A significant effect was

also found for childhood stages [F(2,247)=4.98, P=0.008,

η2p=0.04]. A Bonferroni post hoc test

revealed that children in the middle stage took fewer medications

on average than adolescents (ΔM=-0.29, SE=0.09, t=-3.15, P=0.005).

There was no interaction effect between type of medication and age

[F(2,247)=0.71, P=493, η2p=0.01)].

Differences in the mean number of antipsychotic and

non-antipsychotic medications across ages are presented in Fig. 2.

Differences between children at high

and low risk of falls in terms of demographic variable

A Mann-Whitney U test was conducted to assess the

differences between children at lower and higher risk of falls for

the following continuous or ordinal variables: age of first

diagnosis, current age, BMI, number of diagnoses, number of

comorbidities and number of medications taken per child, including

the number of antipsychotics, non-antipsychotics, and vitamins

(Table IV). Significant

differences were found between these groups in terms of first

diagnosis and current age. In particular, participants at higher

risk of falls were diagnosed <6 years of age, whereas those at

lower risk were diagnosed at ~8 years of age. Similarly, younger

children (mean age, 10 years) had a higher risk of falls than older

children (mean age, 12 years). The differences in BMI, number of

diagnoses, comorbidity and medications taken per child were not

significant.

| Table IVMann-Whitney U test for examining the

differences between children at a high and low risk of falls in

demographic continuous or ordinal variables. |

Table IV

Mann-Whitney U test for examining the

differences between children at a high and low risk of falls in

demographic continuous or ordinal variables.

| | Low risk

(n=176) | High risk

(n=74) | |

|---|

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | U test | P-value | RBC |

|---|

| Age at first

diagnosis | 7.84 | 3.39 | 5.93 | 3.02 | 8632.0 |

<0.001 | 0.33 |

| Current age | 12.43 | 3.65 | 9.78 | 3.67 | 9082.5 |

<0.001 | 0.40 |

| Body mass index

(BMI) | 18.92 | 5.71 | 17.69 | 5.14 | 7359.5 | 0.071 | 0.15 |

| No. of

diagnoses | 1.24 | 0.48 | 1.16 | 0.37 | 6923.0 | 0.261 | 0.06 |

| Comorbidity | 1.33 | 1.01 | 1.22 | 0.97 | 6917.0 | 0.418 | 0.06 |

| No. of

medications | 1.90 | 1.32 | 2.11 | 1.46 | 5987.0 | 0.294 | 0.00 |

|

Antipsychotics | 1.26 | 0.94 | 1.20 | 1.07 | 6818.0 | 0.535 | 0.05 |

|

Non-antipsychotics | 0.65 | 1.04 | 0.91 | 1.27 | 5865.0 | 0.156 | -0.10 |

|

Vitamins | 0.62 | 0.87 | 0.70 | 0.92 | 6228.5 | 0.542 | -0.04 |

As regards categorical variables, the analyses

identified significant associations between pediatric risk of falls

and age (Table V). Among the

children who were at a higher risk of falls, those at an early age

(60%) were more susceptible than their counterparts in middle

childhood (34%) and adolescents (16%). However, the effect size was

small (P<0.001, φ=31).

| Table VAnalysis of the associations between

pediatric risk of falls and categorical demographic variables. |

Table V

Analysis of the associations between

pediatric risk of falls and categorical demographic variables.

| | Low risk

(n=176) | High risk

(n=74) | |

|---|

| Variable | Categories | No. of

participants | % | No. of

participants | % | χ2 | df | P | φ/V |

|---|

| Age | Early (3-6

years) | 12 | 40.0 | 18 | 60.0 | 23.82 | 2 |

<0.001 | 0.31 |

| | Middle (7-12

years) | 75 | 65.8 | 39 | 34.2 | | | | |

| | Late (13-17

years) | 89 | 84.0 | 17 | 16.0 | | | | |

| Sex | Female | 51 | 79.7 | 13 | 20.3 | 3.56 | 1 | 0.059 | 0.12 |

| | Male | 125 | 67.2 | 61 | 32.8 | | | | |

| Education

status | Public school | 51 | 71.8 | 20 | 28.2 | 6.76a | 3 | 0.152 | 0.15 |

| | Disability/autism

center | 52 | 77.6 | 15 | 22.4 | | | | |

| | Other | 4 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | | | | |

| | Not mentioned | 69 | 63.9 | 39 | 36.1 | | | | |

| Region | Riyadh | 130 | 71.8 | 51 | 28.2 | 0.64 | 1 | 0.425 | 0.05 |

| | Other regions | 46 | 66.7 | 23 | 33.3 | | | | |

| Parents'

knowledge | Yes | 133 | 73.9 | 47 | 26.1 | 3.76 | 1 | 0.053 | 0.12 |

| | No | 43 | 61.4 | 27 | 38.6 | | | | |

Logistic regression analysis of

pediatric risk of falls

Linear regression analysis was performed for

pediatric risk of falls, assessed using the HDFS as the dependent

variable. The predictors were age at first diagnosis, current age,

BMI, sex, education status, parents' knowledge about ASD, number of

diagnoses, number of comorbidities, number of antipsychotics and

non-antipsychotics taken (Table

VI). The regression model explained 23% of the pediatric risk

of falls variance [R=0.48, R2=0.23, F(10,238)=6.92,

P<0.001]. However, only two variables predicted a high risk of

falls in children with ASD: A lower current age of the child

(β=-0.34, P<0.001) and being male (β=0.21, P<0.001).

| Table VILinear regression analysis of

pediatric risk of falls. |

Table VI

Linear regression analysis of

pediatric risk of falls.

| | 95% CI | Collinearity |

|---|

| Independent

variables | b | SE | β | t | P-value | LL | UL | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|

| (Intercept) | 12.30 | 0.63 | | 19.61 | <0.001 | 11.06 | 13.53 | | |

| Age at first

diagnosis | -0.06 | 0.04 | -0.12 | -1.46 | 0.145 | -0.15 | 0.02 | 0.48 | 2.10 |

| Current age | -0.16 | 0.04 | -0.34 | -3.96 | <0.001 | -0.23 | -0.08 | 0.46 | 2.19 |

| Body mass index

(BMI) | -0.01 | 0.02 | -0.04 | -0.56 | 0.578 | -0.05 | 0.03 | 0.84 | 1.19 |

| Sex | 0.86 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 3.64 | <0.001 | 0.40 | 1.33 | 0.97 | 1.03 |

| Education

status | -0.03 | 0.08 | -0.02 | -0.31 | 0.754 | -0.19 | 0.14 | 0.91 | 1.11 |

| Parents' knowledge

of autism | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.64 | 0.524 | -0.31 | 0.61 | 0.93 | 1.08 |

| No. of

diagnoses | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.818 | -0.21 | 0.26 | 0.74 | 1.35 |

| No. of

comorbidities | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.923 | -0.44 | 0.48 | 0.94 | 1.07 |

| No. of

antipsychotics taken | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.54 | 0.590 | -0.16 | 0.28 | 0.88 | 1.14 |

| No. of

non-antipsychotics taken | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.92 | 0.357 | -0.11 | 0.31 | 0.71 | 1.42 |

Discussion

The present study identified an association between

the age of children and the total number of medications taken and

antipsychotic medications used. Furthermore, the findings indicated

a significant association between the risk of falls and age. The

results of logistic regression analysis suggested that multiple

factors, including a lower current age and the male sex, predict

the risk of falls. Among the health conditions that were comorbid

with ASD, the results revealed that ASD conditions have a high

comorbidity burden with a significant co-occurrence of ADHD,

followed by intellectual disabilities and epilepsy. Overall,

comorbidity profiles were present in almost 80% of ASD cases. This

reflects the fact that comorbidity is an emerging health concern in

ASD (14). Notably, the high

comorbidity profile associated with ASD is a confounding factor in

elucidating the pathological mechanisms of ASD and is the

foundation of ASD heterogeneity. It has been previously proposed

that ASD can be categorized into essential and complex ASD, the

latter of which refers to individuals who have a greater number of

seizures and lower intellectual capabilities (15).

Presenting with a comorbidity is linked to poorer

health outcomes and elevated healthcare needs among children

diagnosed with ASD, including, but not restricted, to management by

different clinical disciplines, economic burden, and coordinating

clinical, behavioral and pharmacological management (16). Identifying and characterizing the

number of health comorbidities is essential in mapping ASD cases as

it aids in treatment and prognosis (17). A comprehensive understanding of

comorbidities generally improves health metrics and quality of life

(18).

The comorbidity of ADHD and ASD is, however, well

recognized. In a previous study, utilizing a cross-sectional study

design, the co-occurrence of both conditions was evident in almost

50% of the study sample which comprised more than three thousand

children with ASD (19). In a

meta-analysis study, it was found that compared to adolescents,

children with ASD exhibited a higher prevalence of ADHD and

sleep-related issues (20).

However, the comorbidity of ASD-ADHD continues to be a subject of

debate (21). Furthermore, both

ASD and ADHD are described separately in the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders version 5 (DSM-5).

Nevertheless, both similarities and differences between them were

included (22), indicating a

potential recognition of ASD-ADHD in future versions of DSM. Our

findings align with existing literature and highlight the existence

of a clinically distinct subgroup of ASD-ADHD (19,21,23).

Therefore, moving forward and establishing characteristic

diagnostic and management strategies is paramount.

A previous study also indicated that the rate of

antipsychotics taken in children with ASD is high (24). According to a previous

meta-analysis, the rate is expected to reach 1 adolescent with ASD

in every 10 adolescents treated with antipsychotics. This could be

driven by the fact that aggression, irritability (25) and other psychiatric conditions are

commonplace in ASD (26). Evidence

extracted from a systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that

antipsychotics engender a significant clinical improvement in

children with ASD compared to adults (27). The present study found that the age

of the children and the total number of medications taken were

positively associated. In support of these findings, previous

studies have indicated that increases in age correlate with the

number of medicines used (28-30).

For instance, a significant association between age and treatment

was found in a report utilizing the Simons Simplex Collection

(29).

The present study also identified an association

between the age at first diagnosis and the risk of falls among

children with ASD. Specifically, those at a higher risk of falls

were diagnosed with their condition <6 years of age, while those

at a lower risk received their diagnosis at ~8 years of age. In

general, the risk of falls and fall-related consequences were

reported to be higher in younger children than in older ones.

Specifically, it was found that there were ~20 fall-related deaths

in children <5 years of age and 10 fall-related deaths in

children aged between 5 and 9 years (31).

Herein, a significant association was also found

between the age at first diagnosis and the risks of falls. This

could be driven by the fact that a younger age at first diagnosis

is linked to severe behavioral symptoms, including aggression and

tantrums (32). In line with this

finding, a significant number of toddlers diagnosed with ASD <4

years of age present with more complex medical conditions (33). Alongside this, the time of

diagnosis is also clinically relevant (34).

One of the ASD-associated symptoms is motor

dysfunction. Hypotonia was documented to have prevailed in 50% of

ASD cases in a retrospective study conducted at the New Jersey

Medical School autism center. Notably, this functional reduction in

muscle tone was found to be improved in older ASD cases (35). Supporting these findings, the risks

of falls are reduced as age increases. In support of this, a recent

qualitative study demonstrated that children with ASD are prone to

accidental injuries. These injuries were associated with risk

factors, including comorbidity of other conditions (36). Another report indicated that the

most common accidental injury in ASD was a mechanical fall, which

was documented in 44% of the study sample (37). According to the World Health

Organization, falls account for >600,000 deaths each year, and

it is the second leading cause of mortality (38). Yet, the defined characterizations

of motor dysfunction consequences, detection, and interventions

have not been well investigated in ASD (39).

The prevalence of ASD differs regionally. For

example, in some USA states such as Pennsylvania and California, it

can reach around 50 cases per 1,000 children. Other states could be

estimated to be 15 per 1,000 children (40). On the other hand, ASD is estimated

at 9.4 per 1,000 children in Korea (41). Even there are regional differences

in the documented ASD cases, the fact that it is comorbid with ADHD

and linked to an elevated rate of falls is consistent. The data of

the present study enhance existing knowledge regarding the

association between the pediatric risk of falls and younger age and

the comorbidities of ASD and ADHD. The present study found that in

the Saudi population, the comorbidity of ASD-ADHD was consistent

with previous findings in Taiwanese (42), English (43) and Korean populations (44). In line with this, the elevated risk

of falls was recognized to be linked to ASD in different

populations (8,45).

The associated ASD-ADHD comorbidity and risk of

falls are predominant in different cultures, providing insights

that enrich global understandings and recognition of ASD-associated

conditions and consequences. It underscores the significance of

raising parents' awareness of the risks of falls, considering that

sometimes falls are not reported to the healthcare system (46). It further highlights the need to

establish an early intervention in younger ASD children to reduce

the health burden and improve clinical safety in ASD children at

the global level.

The present study has several clinical implications.

Firstly, it highlights the heterogeneity of ASD and its association

with severe consequences such as risk of falls. Thus, it is

recommended that healthcare professionals establish policies aimed

at raising awareness and educating families about the risk of falls

in younger individuals with ASD, particularly those who are taking

antipsychotics, and implement these educational workshops to be

mandatory appointments/sessions with healthcare professionals,

whether under a family care unit or primary healthcare clinic.

Secondly, as the association is significant, the findings affirm

ASD-ADHD comorbidity, and thus the need to establish characteristic

diagnostic and management strategies is paramount.

The present study however, also has certain

limitations, which should be mentioned. The present study provides

evidence regarding the current status of treatment and

comorbidities of children with ASD. The children's comorbidity

burden and treatment patterns were characterized. The present study

also conducted a correlation analysis to evaluate the risks of

falls among different age groups using observational data on 250

patients with ASD from routine clinical practice at KSUMC. However,

the present study has a number of limitations that need to be

addressed. Firstly, the sample size was relatively small. Although

multiple EMR studies have been published with a similar sample size

range (47,48), 250 is appropriate if statistically

robust conclusions are to be drawn. It is therefore recommended

that these findings be replicated using a larger sample size.

Furthermore, the present study was a single-center report, thus

rendering it necessary to expand these findings using a multicenter

study design (49,50). Additionally, the present study

focused on the pharmacological treatment approach. Indeed, it is

widely acknowledged that a majority of children with ASD take

pharmacological treatment (11).

However, ASD is also managed using behavioral and pharmacological

treatment strategies (51).

Furthermore, the findings report the current status of the number

of medications taken; however, no history of the number of

medications taken was obtained. In addition, although

pharmacological treatment was characterized, compliance was not

investigated. Moreover, in any follow-up, further adjustment of

diverse covariance is required for the multifactorial features of

ASD, ASD management, comorbidity and the risk of falls.

In conclusion, ASD is increasingly being recognized

as a significant and growing public health concern. It places a

substantial socio-economic burden upon families. The findings of

the present study confirm existing evidence regarding the link

between the pediatric risk of falls and a younger age.

Additionally, the present study confirmed the comorbidity of ASD

and ADHD, emphasizing the need to identify ASD-ADHD in the future

as a clinical subgroup of developmental disorders. These results

will also encourage healthcare practitioners to increase parental

awareness of the risks of falls in young autistic children.

Supplementary Material

Data S1

Data S2

Categorization of particular

additional diseases reported in children with autism (n=250).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the College

of Pharmacy Research Center and the Deanship of Scientific Research

at King Saud University for their continuous support, the provision

of research facilities and infrastructure, administrative

assistance, and encouragement throughout the duration of this

study.

Funding

Funding: Financial funding was provided by the King Abdul-Aziz

City for Science and Technology, General Directorate for Fund and

Grants to King Saud University to implement the study (Project no.

5-21-01-001-0015).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MAA, TKA and AMR conceptualized the study and were

involved in the study methodology. AMR was involved in the formal

analysis. HMA and SAA were involved in the investigative aspects of

the study. HAA, SAA and AMR were involved in data curation. MAA and

TKA confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. HAA, SAA, TKA and

AMR were involved in the writing and preparation of the original

draft of the manuscript. TKA, MAA and AMR were involved in the

writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. MAA and TKA

supervised the study. MAA was involved in project administration.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional

Review Board at King Saud University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (Ref.

E-22-7451 no. 23/0175/IRB); issue date, March 2, 2023. A waiver of

written informed consent was granted by the ethics committee.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cervera GR, Romero MGM, Mas LA and Delgado

FM: Intervention models in children with autism spectrum disorders.

In: Autism Spectrum Disorders. Tim W (ed). IntechOpen, Rijeka, p7,

2011.

|

|

2

|

Zeidan J, Fombonne E, Scorah J, Ibrahim A,

Durkin MS, Saxena S, Yusuf A, Shih A and Elsabbagh M: Global

prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res.

15:778–790. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hyman SL, Levy SE and Myers SM: Council on

Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental and Behavioral

Pediatrics. Identification, evaluation, and management of children

with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics.

145(e20193447)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hussain A, John JR, Dissanayake C, Frost

G, Girdler S, Karlov L, Masi A, Alach T and Eapen V: Sociocultural

factors associated with detection of autism among culturally and

linguistically diverse communities in Australia. BMC Pediatr.

23(415)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Faruk MO, Rahman MS, Rana MS, Mahmud S,

Al-Neyma M, Karim MS and Alam N: Socioeconomic and demographic risk

factors of autism spectrum disorder among children and adolescents

in Bangladesh: Evidence from a cross-sectional study in 2022. PLoS

One. 18(e0289220)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Pan PY, Bölte S, Kaur P, Jamil S and

Jonsson U: Neurological disorders in autism: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Autism. 25:812–830. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Craig F, Castelnuovo R, Pacifico R, Leo R

and Trabacca A: BIM Falls Study Group*. Falls in hospitalized

children with neurodevelopmental conditions: A cross-sectional,

correlational study. Rehabil Nurs. 43:335–342. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

DiGuiseppi C, Levy SE, Sabourin KR, Soke

GN, Rosenberg S, Lee LC, Moody E and Schieve LA: Injuries in

children with autism spectrum disorder: Study to explore early

development (SEED). J Autism Dev Disord. 48:461–472.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Shin HJ, Kim YN, Kim JH, Son IS and Bang

KS: A pediatric fall-risk assessment tool for hospitalized

children. Child Health Nurs Res. 20:215–224. 2014.

|

|

10

|

Malone RP and Waheed A: The role of

antipsychotics in the management of behavioural symptoms in

children and adolescents with autism. Drugs. 69:535–548.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Jonkman KM, Back E and Begeer S:

Predicting intervention use in autistic children: Demographic and

autism-specific characteristics. Autism. 27:428–442.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lee McIntyre L and Zemantic PK: Examining

services for young children with autism spectrum disorder: Parent

satisfaction and predictors of service utilization. Early Child

Educ J. 45:727–734. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Alnemary FM, Aldhalaan HM, Simon-Cereijido

G and Alnemary FM: Services for children with autism in the Kingdom

of Saudi Arabia. Autism. 21:592–602. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ahmedani BK and Hock RM: Health care

access and treatment for children with co-morbid autism and

psychiatric conditions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol.

47:1807–1814. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Miles JH, Takahashi TN, Bagby S, Sahota

PK, Vaslow DF, Wang CH, Hillman RE and Farmer JE: Essential versus

complex autism: Definition of fundamental prognostic subtypes. Am J

Med Genet A. 135:171–180. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Casanova MF, Frye RE, Gillberg C and

Casanova EL: Editorial: Comorbidity and autism spectrum disorder.

Front Psychiatry. 11(617395)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Rim SJ, Kwak K and Park S: Risk of

psychiatric comorbidity with autism spectrum disorder and its

association with diagnosis timing using a nationally representative

cohort. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 104(102134)2023.

|

|

18

|

Butterly EW, Hanlon P, Shah ASV, Hannigan

LJ, McIntosh E, Lewsey J, Wild SH, Guthrie B, Mair FS, Kent DM, et

al: Comorbidity and health-related quality of life in people with a

chronic medical condition in randomised clinical trials: An

individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Med.

20(e1004154)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Gordon-Lipkin E, Marvin AR, Law JK and

Lipkin PH: Anxiety and mood disorder in children with autism

spectrum disorder and ADHD. Pediatrics.

141(e20171377)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Micai M, Fatta LM, Gila L, Caruso A,

Salvitti T, Fulceri F, Ciaramella A, D'Amico R, Del Giovane C,

Bertelli M, et al: Prevalence of co-occurring conditions in

children and adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev.

155(105436)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Hours C, Recasens C and Baleyte JM: ASD

and ADHD comorbidity: What are we talking about? Front Psychiatry.

13(837424)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

American Psychiatric Association (APA):

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR).

APA, Washington, DC, 2013.

|

|

23

|

Miller M, Austin S, Iosif AM, de la Paz L,

Chuang A, Hatch B and Ozonoff S: Shared and distinct developmental

pathways to ASD and ADHD phenotypes among infants at familial risk.

Dev Psychopathol. 32:1323–1334. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Rast JE, Anderson KA, Roux AM and Shattuck

PT: Medication use in youth with autism and

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Acad Pediatr. 21:272–279.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Park SY, Cervesi C, Galling B, Molteni S,

Walyzada F, Ameis SH, Gerhard T, Olfson M and Correll CU:

Antipsychotic use trends in youth with autism spectrum disorder

and/or intellectual disability: A meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child

Adolesc Psychiatry. 55:456–468.e4. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Posey DJ, Stigler KA, Erickson CA and

McDougle CJ: Antipsychotics in the treatment of autism. J Clin

Invest. 118:6–14. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Deb S, Roy M, Limbu B, Akrout Brizard B,

Murugan M, Roy A and Santambrogio J: Randomised controlled trials

of antipsychotics for people with autism spectrum disorder: A

systematic review and a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 53:7964–7972.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Houghton R, Ong RC and Bolognani F:

Psychiatric comorbidities and use of psychotropic medications in

people with autism spectrum disorder in the United States. Autism

Res. 10:2037–2047. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Mire SS, Raff NS, Brewton CM and

Goin-Kochel RP: Age-related trends in treatment use for children

with autism spectrum disorder. Res Autism Spect Disord.

15-16:29–41. 2015.

|

|

30

|

Xu G, Strathearn L, Liu B, O'Brien M,

Kopelman TG, Zhu J, Snetselaar LG and Bao W: Prevalence and

treatment patterns of autism spectrum disorder in the United

States, 2016. JAMA Pediatr. 173:153–159. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Gill AC and Kelly NR: Falls and

fall-related injuries in children: Prevention.

UpToDate®, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/falls-and-fall-related-injuries-in-children-prevention.

Accessed November 23, 2024.

|

|

32

|

Sicherman N, Charite J, Eyal G, Janecka M,

Loewenstein G, Law K, Lipkin PH, Marvin AR and Buxbaum JD: Clinical

signs associated with earlier diagnosis of children with autism

Spectrum disorder. BMC Pediatr. 21(96)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Kim SH, Macari S, Koller J and Chawarska

K: Examining the phenotypic heterogeneity of early autism spectrum

disorder: Subtypes and short-term outcomes. J Child Psychol

Psychiatry. 57:93–102. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Wiggins LD, Baio J and Rice C: Examination

of the time between first evaluation and first autism spectrum

diagnosis in a population-based sample. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 27 (2

Suppl):S79–S87. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Ming X, Brimacombe M and Wagner GC:

Prevalence of motor impairment in autism spectrum disorders. Brain

Dev. 29:565–570. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Morgan CH, Mercier A, Stein B, Guest KC,

O'Kelley SE and Schwebel DC: A qualitative analysis of

unintentional injuries in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev

Disord: Jan 27, 2025 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

37

|

Jones V, Ryan L, Rooker G, Debinski B,

Parnham T, Mahoney P and Shields W: An exploration of emergency

department visits for home unintentional injuries among children

with autism spectrum disorder for evidence to modify injury

prevention guidelines. Pediatr Emerg Care. 37:e589–e593.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

World Health Organization (WHO): Falls

Fact Sheet. WHO, Geneva, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls.

|

|

39

|

Zampella CJ, Wang LAL, Haley M, Hutchinson

AG and de Marchena A: Motor skill differences in autism spectrum

disorder: A clinically focused review. Curr Psychiatry Rep.

23(64)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Shaw KA, Williams S, Patrick ME,

Valencia-Prado M, Durkin MS, Howerton EM, Ladd-Acosta CM, Pas ET,

Bakian AV, Bartholomew P, et al: Prevalence and early

identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4

and 8 years-autism and developmental disabilities monitoring

network, 16 sites, United States, 2022. MMWR Surveill Summ.

74:1–22. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Yoo SM, Kim KN, Kang S, Kim HJ, Yun J and

Lee JY: Prevalence and premature mortality statistics of autism

spectrum disorder among children in Korea: A nationwide

population-based birth cohort study. J Korean Med Sci.

37(e1)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Chen MH, Wei HT, Chen LC, Su TP, Bai YM,

Hsu JW, Huang KL, Chang WH, Chen TJ and Chen YS: Autistic spectrum

disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and psychiatric

comorbidities: A nationwide study. Res Autism Spect Disord. 10:1–6.

2015.

|

|

43

|

Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler

S, Loucas T and Baird G: Psychiatric disorders in children with

autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated

factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc

Psychiatry. 47:921–929. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Kim MJ, Park I, Lim MH, Paik KC, Cho S,

Kwon HJ, Lee SG, Yoo SJ and Ha M: Prevalence of

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and its comorbidity among

Korean children in a community population. J Korean Med Sci.

32:401–406. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Florence C, Simon T, Haegerich T, Luo F

and Zhou C: Estimated lifetime medical and work-loss costs of fatal

injuries-United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.

64:1074–1077. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Shmueli D, Razi T, Almog M, Menashe I and

Mimouni Bloch A: Injury rates among children with autism spectrum

disorder with or without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

JAMA Netw Open. 8(e2459029)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Al-Amoosh HHS, Al-Amer R, Alamoush AH,

Alquran F, Atallah Aldajeh TM, Al Rahamneh TA, Gharaibeh A, Ali AM,

Maaita M and Darwish T: Outcomes of COVID-19 in pregnant women: A

retrospective analysis of 300 cases in Jordan. Healthcare (Basel).

12(2113)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Spencer RA, Spencer SEF, Rodgers S,

Campbell SM and Avery AJ: Processing of discharge summaries in

general practice: A retrospective record review. Br J Gen Pract.

68:e576–e585. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Jo D: The interpretation bias and trap of

multicenter clinical research. Korean J Pain. 33:199–200.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Seifirad S and Alquran L: The bigger, the

better? When multicenter clinical trials and meta-analyses do not

work. Curr Med Res Opin. 37:321–326. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Höfer J, Hoffmann F and Bachmann C: Use of

complementary and alternative medicine in children and adolescents

with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Autism.

21:387–402. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|