1. Introduction

Over the years, research on the gut microbiota and

its influence on respiratory health has evolved into the concept of

the gut-lung axis. Initially regarded as a simple connection,

studies in the 1990s and early 2000s began exploring the role of

probiotics in supporting immune function and reducing respiratory

infections (1-7).

The discoveries laid the foundation for understanding the intricate

association between the microbiome and the immune system in

maintaining lung health. A deeper understanding of the role of the

microbiome in both healthy and diseased individuals has

significantly contributed to identifying biomarker patterns, aiding

in early disease detection and personalized treatment strategies.

The integration of microbiome research into precision medicine has

been particularly impactful, as specific beneficial bacterial

strains have shown resilience to physiological stress, providing

promising therapeutic potential. Patients with a well-defined

microbial niche could benefit from next-generation treatments

tailored to their microbiome composition (8).

Microbial communities within the human body play

essential metabolic and immunological roles. The lung microbiome,

primarily composed of Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Prevotella,

Fusobacterium, Haemophilus, Veillonella and

Porphyromonas (9),

contributes to respiratory health through the production of

small-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which help regulate immune

responses. While precision medicine was initially centered on

genetic and phenotypic variations, there is currently a paradigm

shift towards the understanding the microbiome as a key factor

influencing health and disease (10). Investigating the crosstalk between

gut and lung microbiomes in various diseases holds promise for the

development of novel diagnostic markers and advancing personalized

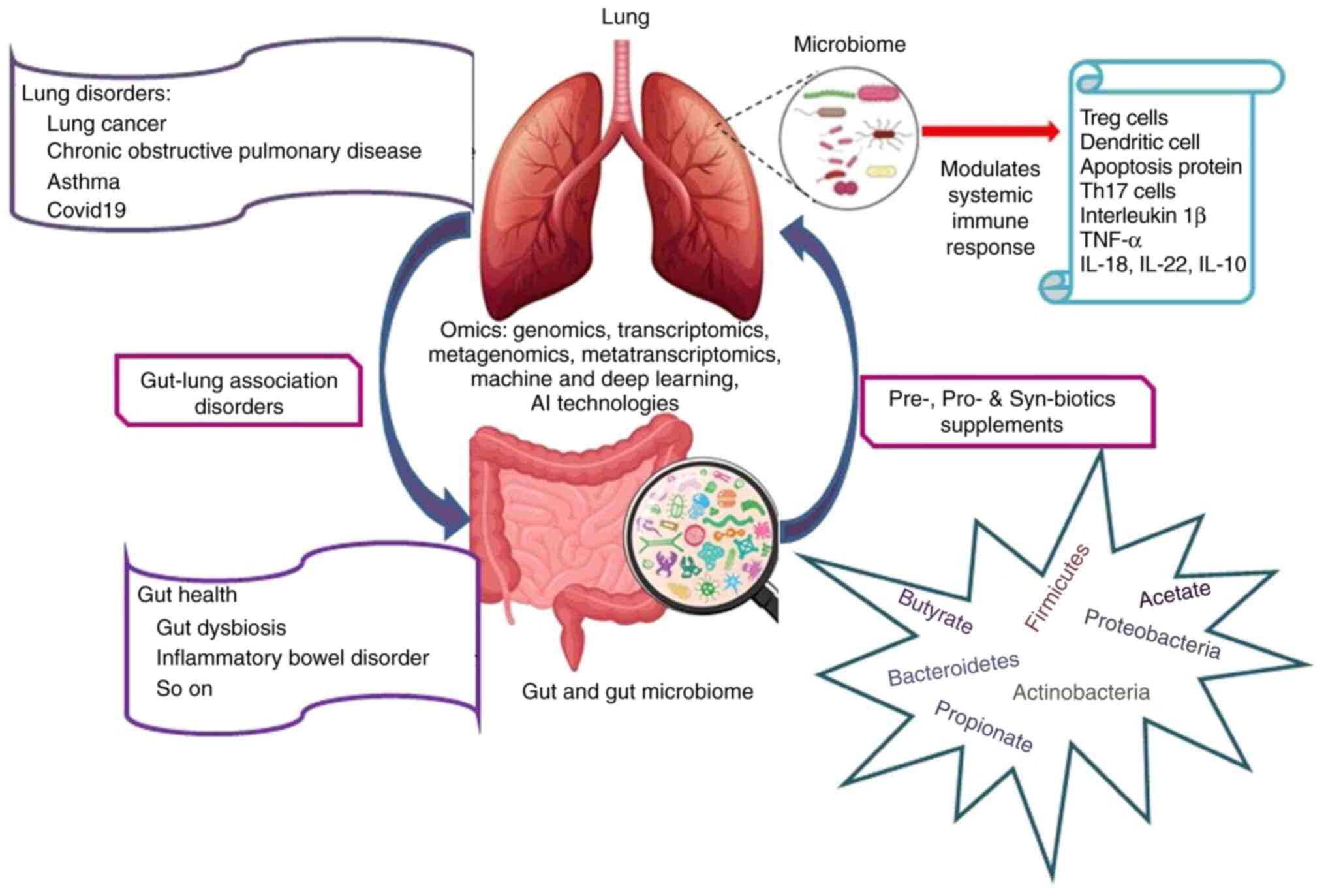

medicine (Fig. 1). This evolving

perspective opens new avenues for integrating microbiome-targeted

therapies into clinical practice.

2. Precision medicine and the human

microbiome

Precision medicine is based on the deep

characterization of the genome, proteome, metabolome and microbiome

of an individual. Rapidity and technical advancements in genome

studies (DNA-Seq, RNA-Seq, Exosome-Seq, etc.) decreased the cost of

sequencing and genotyping that typically shifted the paradigm of

precision medicine from academic exercise to clinical applications

(11). The milestone projects,

such as complete human genome sequencing, HapMap (Haplotype Map)

project, Phase 1- NIH human microbiome project, and the phase 1-

European Union MetaHit (Metagenomics of the Human Intestinal Tract)

Project contributed to the understanding of the molecular basis of

diseases and to the development of initiatives to propose new

prototypes of personalized medicine (12,13).

The most recent advancement in understanding human disease is to

derive its association with the human microbiota. The human

microbiome is referred to as the second genome, as trillions of

microbial inhabitants are integrated ecologically and symbiotically

with their host. The analyzed omics profile of an individual aids

in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of diseases. Knowledge

of human genomic variants and phenotypic changes is critical for

understanding the molecular basis of the disease (14). The human body colonizes diverse

communities of microbes, and also resists the colonization of

pathogenic organisms, such as Clostridium difficile

(15), which clearly suggests the

existence of symbiotic associations between the human body and its

microbiota. A previous study confirmed the presence of bacterial

peptides in blood serum and plasma of approximate range/of 0.1 nM

to 1 µM (16). That study utilized

the human microbiota protein sequences from NIH Human Microbiome

Project which as useful for determining the microbiota composition

in the intestinal regions. Well-structured databases are available

to provide the genotypic and phenotypic related variants and

related traits [ClinGen (https://clinicalgenome.org/), ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/),

dbVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/dbvar/), The Cancer

Genome Atlas (TCGA) (https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga),

dbGENVOC (https://research.nibmg.ac.in/dbcares/dbgenvoc/home.php),

HGMD (https://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php), OMIM

(https://omim.org/), etc.]. The concept of ‘One dose

fits all’ is ideologically replaced with personalized medicine to

ensure a tailored treatment with effective and safe drug usage. For

an accelerated research, the accessibility to Electronic Health

Records (Electronic Medical Records and Genomics-Pharmacogenomics

(eMERGE-PGx) project, GANI_MED project, SCAN-B initiative and

Cancer 2015) provides an in-depth analysis of the medical history

of an individual against various infections and higher predictive

nature to derive the susceptibility of the patient to other

comorbid diseases. Other than this, knowledge-based approaches

derived from documented literature utilize sophisticated

text-mining and natural language processing for literature curation

and annotation to extract the vast amount of information buried

about the genetic variants and their functional phenotypic

associations (17).

3. Role of the gut microbiome in precision

medicine: Gut-lung axis microbiome

In recent days, ‘Gut Microbiota’ is a buzz word and

often termed as a forgotten organ/metabolic organ that plays a

fine-tuned symbiotic association with the host. Hundreds of

trillions of diverse microbial communities that include protozoa,

fungi, archaea, viruses, protists and bacteria reside within the

gastrointestinal tract (GIT) compared to the regions of skin, eye,

urogenital and epithelial layers of the respiratory system. In

general, the microbiome of an individual is more complex than the

human genome and it imparts a specific immunity to the individual

that characterizes the need to have personalized medicine.

According to the studies of the Human Microbiome project (18), it was revealed that the ratio of

commensal microbial genes to the total number of human genes was

high and the adult human gut can harbor trillions of microbes;

therefore, it exceeds the total number of somatic and germ cells by

10-fold (19).

The composition and pattern of the microbiota of an

individual is very specific and hence, it enables the

identification of disease-specific microbial signatures, providing

personalized predictive biomarkers for various diseases (20,21).

The insights from the gut-lung axis and the identification of

microbial patterns aids in the early identification and diagnostics

based on various immunological responses. With respect to

conventional therapies, this also triggers microbiome-targeted

interventions, such as probiotics, prebiotics and fecal microbiota

transplantation, which are more promising and safe strategies

(22,23). Given the complexity of microbiome

data, analyzing it is a challenge. which is strategically now being

done using various machine learning, deep learning and more

recently quantum methods (24).

The integration of microbiome-based diagnostics and therapies into

clinical frameworks has the potential to optimize respiratory

illness care, while maintaining microbial equilibrium, as precision

medicine moves beyond genetic and phenotypic differences.

The reasons for studying the gut

microbiome instead of the lung microbiome for addressing lung

disorders

The lung was originally described to be a sterile

organ; however, with technical advancements, the lung microbiome

was then defined, which is composed of a complex and diverse

bacterial community, with a low biomass. There is substantial

variation between upper and lower respiratory tract microbiomes due

to higher flux exhibited by microbes (25). Different environmental niches are

created as a result of the differential availability of pH and

nutritional factors, which plays a critical role during

inflammation or through structural changes in chronic respiratory

diseases (CRDs) (26). The

respiratory microbiome is also combined with the upper respiratory

tract and gut microbiota, which renders the assessment of its role

difficult (27,28).

The gut-lung axis refers to the communication

between the gut, lung and vice versa, where the gut microbial

metabolites enter the lung via the blood stream and influence the

pulmonary microbiome. Emerging scientific reports demonstrate the

modulation of systemic immune responses through altering the diet

and antibiotic treatment. In addition, an altered lung microbiome

in various chronic lung disorders indicates that the gut-lung axis

is bidirectional (29).

Immunological crosstalk between the respiratory and gut microbiome

is reflected by the fact that patients with chronic respiratory

disease are prone to GIT-related issues and vice-versa, where

patients with inflammatory bowel disease display pulmonary

involvement (30).

The gut and lung microbial communities overlap in

their phylum, but differ in local compositions and total microbial

biomass (31). This overlap may be

responsible for microbial interference in different disease

associations. The gut microbiota modulates immune responses

differently in healthy individuals and in patients with lung

disorders, which is dependent on diet and food intake.

Diet-Microbiota-Immunity link supplemented by high fiber diet is

well explained in different studies (30). The fiber intake influences the gut

microbiota by increasing the production of bacterial metabolites,

such as SCFAs (e.g., propionate, acetate and butyrate) (32); this in turn modulates different

aspects of defense lines, such as promoting goblet cell

differentiation and mucus production, stimulating the proliferation

of T-regulatory cells which produces anti-inflammatory cytokine

(e.g. IL-10), as well as the production of intestinal IgA by

affecting plasma B-cell metabolism and modulating tight junction

permeability to enhance intestinal epithelial barrier function in

the gut of the host (33).

The so-called exposome that includes socio-economic

factors, nutrition, stress, environmental factors (pollutants,

antibiotics, etc.) and the individual's genetics, sex and age

composes the microbial diversity of the GIT (34). Metabolites produced by the gut

microbiota are capable of eliciting or activating the downstream

cascades of reactions. The continuous interplay between the gut

microbiota and intestinal epithelium sends signals for the

regulation of immune responses to infectious diseases and

disorders. In the case of infectious diseases, the microbial

colonization of commensals and pathogenic organisms undergo

crosstalk with host immune responses (35). The consumption of a healthy diet

could modulate the local and systemic host physiology, metabolism,

immune function and nutrition state.

In the GIT, the bacterial cell-cell communication

takes place through the exchange of chemical messages using quorum

sensing mechanisms that are capable of triggering changes in the

gene expression. Extensive studies on quorum sensing between

bacterial communities in a local niche are being carried out; the

GIT is a complex system where bacteria respond to a milieu of

chemical signals to synchronize bacterial behavior and convert them

into reliable messages to coordinate the relative species, as well

as with the host immune system. Hence, in the GIT, multidirectional

communication pathways of quorum sensing occur and are referred

generally as interspecies communications and interkingdom signaling

(36). Gram-negative bacteria

produce N-acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) that bind to LuxR

receptors to communicate with each other and their accumulation to

a threshold concentration activates the gene expression for toxin

production and biofilm formation. Certainly, AHLs influence the

host immune system through the secretion of IL-10, where their

specific functions are to limit the host immune response towards

pathogens; in addition, due to the lipid solubility nature of AHLs,

they diffuse into the mammalian cells and induces apoptosis through

cascades of reactions (37). A

more systematic detail of the crosstalk of metabolites through

quorum sensing that interrelates with the gut microbiota and host

immune system has been previously discussed (36).

4. Microbial niches and their metabolites in

the gut homeostasis

Gut microbes mostly constitute the phyla of

Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and

occasionally, Verrucomicrobia and Fusobacteria (38-40).

Of these, Bateroidetes and Firmicutes constitute ~90% of intestinal

microbiota. Firmicutes are abundant in populations consuming

animal-based diets, whereas Bacteroidetes are largely found in

populations consuming plant-based diets (41). The genes for the hydrolysis of

plant-based polysaccharides are reported in the bacterial strains

of Prevotella and Xylanibacter; therefore, the GIT

possesses higher counts of these organisms in populations depending

on plant-based food varieties. Among the Indian population, the

genera of Prevotella, Lactobacillus and

Carnobacterium are abundant, owing to vegetarian diets of

the majority of the population (42). SCFAs are the most abundant form of

saturated aliphatic organic acids where 10% of SCFAs are

constituted by the daily diet and 70% are generated as a product

synthesized through the microbial niche (43), found within the GIT (Table I). The concentration of SCFA plays

a crucial role at local (colon) and systemic (blood) levels for

immune regulations (44,45). SCFAs supplied from the diet are

utilized by the host for its other metabolic process, whereas

microbial-synthesized SCFAs are employed as energy sources for

epithelial and endothelial cells of the colon (colonocytes). In a

normal human gut, the ratio of the SCFA concentration comprises 60%

of acetate, 25% of propionate and 15% of butyrate (46). Alterations in the microbiome may

influence the susceptibility of an individual to infectious

diseases. For example, the rate of ethanol-induced liver damage is

reduced with the supplementation of butyrate than acetate (47). SCFAs regulate immune functions via

several receptors and pathways; specifically, G-protein coupled

receptors (GPCRs) namely GPCR43 and GPCR120 enhance reactive oxygen

species-mediated killing, phagocytosis and cytokine production,

leading to apoptosis (48).

| Table IFormation of SCFA products in the

GIT. |

Table I

Formation of SCFA products in the

GIT.

| Name of SCFA |

Formation/pathways | Microbes utilizes

the pathway | Function | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Acetate | 1. Decarboxylation

of pyruvate followed by Acetyl-CoA is hydrolyzed to acetate by an

acetyl- CoA hydrolase 2. Wood-Ljungdahl pathway | Prevotella

spp., Ruminococcus spp., Bifidobacterium spp.,

Bacteroides spp., Clostridium spp.,

Streptococcus spp., Akkermansia muciniphila,

Blautia hydrogenotrophica | 1. Insulin level

maintenance 2. Body weight loss 3. Energy production for other

cells of host 4. Lipid synthesis 5. Protein acetylation | (49) |

| Propionate | 1. Succinate

pathway 2. Acrylate pathway 3. Propanediol pathway | Bacteroidetes and

several Firmicutes, Coprococcus catus, Salmonella

enterica serovar Typhimurium, Roseburia

inulinivorans, Akkermansia municiphilla | Gluconeogenesis in

the liver Inhibits histone deacetylase | (50) |

| Butyrate | 1. Classical

Pathway: phosphotransbutyrylase and butyrate kinase enzymes are

involved 2. Butyryl-CoA: acetate CoA-transferase converts

butyryl-CoA into butyrate and acetyl-CoA | Ruminococcus

bromii, Coprococcus species, Eubacterium rectale,

Eubacterium rectale/Roseburia spp., Faecalibacterium

prausnitzii | Intestinal and

extra-intestinal functions | (51) |

5. Significance of pre- and probiotics

Prebiotics are non-digestible food ingredients that

have a positive impact on the composition of the gut microbiome and

their metabolic function at the level of the small intestine and

colon. Alternating the nutrient supplements selectively stimulates

the growth and/or activity of one or a bacterial community within

the colon. Prebiotics and dietary fibers promote the growth of

beneficial bacteria in the gut by acting as a substrate for

fermentation (49-51).

Prebiotic supplements maintain the homeostasis barrier and elevate

mineral absorption, thereby modulating energy metabolism and

satiety. The relevance of microbial diversity and its association

with metabolizing prebiotics and dietary fiber in the upper and

lower GIT, as well as the colon has been previously discussed

(52,53).

Probiotics are supplements with live bacterial feed;

when supplied in adequate quantity, they provide health benefits to

the host. The genera Lactococcus and Bifidobacterium

strains are predominant in the gut. These microbes are considered

significant for use as probiotics due to their exclusive

properties, such as acid and bile tolerance, adhesion to mucosal

and epithelial surfaces, antimicrobial activity against pathogenic

bacteria and bile salt hydrolase activity. The rationale behind the

supply of probiotics is to reshape and strengthen the commensal

microbes to compete for nutritional and functional resources with

the pathogens and to produce antimicrobial substances (54). However, factors such as safety,

product compatibility, viability of the microorganism, pH,

packaging, storage conditions and food processing should be

considered in the case of probiotics supplementation. Therefore,

probiotics should be improved for their viability and stability to

achieve the 100% establishment of microbes in the GIT. Soft cheeses

have an added advantage over yogurts and fermented products for

their delivery system of viable products to the GIT. The selection

of probiotics strains should meet up with the regulations according

to the World Health Organization (WHO), the European Food Safety

Authority (EFSA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for their

safety and functional criteria (55). Technologies, including

microencapsulation, straw delivery system and viable spores of

spore forming organisms are being improvised to overcome the

delivery of live microorganisms into the GIT; however, advanced

techniques to supply other beneficial microbes as probiotics need

to be identified (56).

Dietary supplements can be a combination of

prebiotics and probiotics, that are together represented as either

conbiotics and as synbiotics. The use of synbiotics improves the

survival rate of beneficial microbes and supplies the respective

food or feed required for their proliferation. The challenge in

synbiotics supplementation is to identify the right formulations of

prebiotics and probiotics that are capable of modulating the

intestinal microbiota (55).

6. Human microbiome and its association with

diseases

Microbiome disease associations are very complex and

various omics approaches are integrated to understand them. A major

concern is the ongoing evolution of the microbiome and its direct

effect on metabolite production and its susceptibility towards any

disease, since it has the ability to modulate the immune system.

The human gut is inhabited symbiotically by a complex and

metabolically active microbial ecosystem, which systematically

controls the metabolic activity of humans. In healthy individuals,

the microbiota bacteria present in the lungs are

Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Prevotella,

Fusobacterium, Haemophilus, Veillonella and

Porphyromonas (57). The

microbial metabolic products are of great use for maintaining gut

homeostasis and their varied taxonomic associations provide

detailed information on the diagnostic features of the individual

for personalized medicine. Nutritional supplements mostly include

dietary fibers, prebiotics and probiotics that play a critical role

in the gut homeostasis, and have also been reported to ameliorate

chronic disorders (58). The

association between food intake, microbiome health and the

occurrence of various diseases has been studied. CRDs includes a

range of lung disorders and are major concerns among the global

health burdens. CRDs affect the airways and lungs; among these,

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third leading

cause of mortality worldwide (59). Frequent exposure to polluted air,

hazardous chemical substances such as carcinogens, poor lifestyle

habits (smoking and alcohol consumption) are key factors for the

increased prevalence of asthma and lung cancer (60,61).

COVID-19, although an acute respiratory syndrome, increased risk of

mortality of patients infected with COPD and asthma (62).

The microbial composition in diseased lower airways

exhibits a decreased abundance of the phylum Bacteroidetes and

increased Gammaproteobacteria in contrast to the healthy

population. These Gram-negative pathogens of

Gammaproteobacteria are capable of utilizing the

inflammatory byproducts for their survival under anaerobic and

lower oxygen conditions (63).

Cancer

The association between diet and cancer (colorectal,

post-menopausal breast cancer) was recognized by the Dietary

Guideline Advisory Committee (DGAC) in 2015(64). It has been observed that the

consumption of a high-fat ketogenic diet (HFD) affects the

intestinal stem cell functions through the metabolite

β-hydroxybutyrate-mediated Notch signaling through the expression

of the gene, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthetase 2. A HFD

along with glucose inhibits the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA

synthase 2, an enzyme involved in the production of beneficial

ketone bodies (65). Switching

from glycogenic to ketogenic energy consumption benefits the growth

of normal cells instead of cancer cells by limiting the glucose

production (66). At present, the

University of Iowa is investigating the potential effect of a

ketogenic diet along with chemoradiation therapy for non-small cell

lung cancer (NCT01419587).

Butyrate has pleiotropic functions and plays a role

in the apoptosis of colon cancer cells, intestinal gluconeogenesis

and in controlling gut dysbiosis. Butyrate indirectly regulates the

health of the lungs through systemic inflammatory processes;

treatment with butyrate attenuates inflammation and promotes mucus

production in the lungs (67).

Mucin production is promoted by the butyrate-producing bacteria,

Roseburia spp. Although the mechanisms connecting the

gut-lung axis have not yet been elucidated, there is some

scientific evidence indicating that variant associations among

species and their relative abundance can be used as markers for

lung cancer prediction (68). The

enhanced activation of glutamate metabolism requires the

consumption of the majority of butyrate in the cells of lung

cancer; therefore, the shortage of butyrate for mucin production

leads to its destruction and causes inflammation (69). Consistently, dysbiosis has been

found to occur in the gut microbiota among patients with lung

cancer and the decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria, such as

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Clostridium leptum,

Clostridium cluster I, Ruminococcus spp.,

Clostridium cluster XIVa and Roseburia spp. are

observed in NSCLC. Therefore, the mentioned butyrate-producing

bacterial strains along with Clostridium cluster IV and

Eubacterium rectalis can be considered as gut probiotics. In

addition, these butyrate-producing bacteria have attracted

attention due to their ability to maintain the gut homeostasis

(70). The three proposed theories

for microbial dysbiosis for the onset of carcinogenesis include the

disruption of the immune equilibrium, the initiation of chronic

inflammation and the activation of cancer-causing pathways

(71).

In lung cancer, cell proliferation is associated

with various microbial genera. The microbiome number is altered in

the normal and diseased condition. The most dominant phyla in the

lungs of healthy individuals are Actinobacteria,

Bacteroides, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria

(9). Variations in these

microorganisms are observed in different types of cancer. For

example, in the patients affected with squamous cell carcinoma of

the lung and adenocarcinoma, the genera Capnocytophaga,

Selenomonas and Veillonella are abundant when

compared with the genus Neisseria (72). These microbiota thrive due to their

expression and their role in the activation of signaling and cell

proliferation pathways. For example, the β-catenin signaling

pathway, which promotes cell proliferation, is activated by

Fusobacterium nucleatum. Estimating the occurrence of levels

bacteria such as Fusobacterium nucleatum may be useful for

predicting the progression of cancer. It has also been observed

that patients with lung cancer, when compared with those with

benign disease, have an abundant population of Veillonella

and Megasphaera. Genetic variations in individuals are also

helpful for developing biomarkers. Patients suffering from squamous

cell carcinoma of the lung, lung cancer or benign lung disease with

the TP53 mutation have been shown to have abundant levels of the

genus Acidovorax. Microbiota dysbiosis can contribute to the

pathogenesis of lung cancer, as it leads to the upregulation of

IL6/8, IL17A, MAPK and inflammasome pathways (72).

In a previous study, when probiotic supplements with

aqueous extracts of Bifidobacterium species were to NSCLC

cell lines (A549, H1299 and HCC827) particularly reduced cell

proliferation with the increased expression of cleaved caspase-3

and cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) associated with the

apoptotic pathway (73). In

another study, the additional supplementation of probiotics

containing Bifidobacterium and Clostridium butyricum

in patients with NSCLC receiving anti-programmed cell death-1

therapy (nivolumab, or pembrolizumab monotherapy) increased their

survival state (74).

Bifidobacterium activates dendritic cell function and

directs the T-cell mediated antitumor efficiency, whereas

Clostridium butyricum arrests cancer cell invasion and

migration by reducing Th17 cells (75). It has been shown that bacterial

supplements with Akkermansia muciniphila along with butyrate

inhibit tumor cell proliferation and migration by upregulating the

expression of miRNA (interference RNA) (76). Treatment of NSCLC with propionate

regulates survivin, an inhibitor of the apoptosis protein family

and suppresses p21 expression and the cell cycle (77). To date, the full regulatory

mechanisms of the gut microbiome in systemic inflammation and lung

diseases are not yet completely known; thus, it is necessary to

take a multidisciplinary approach to elucidate these

mechanisms.

COPD and asthma

COPD is a fatal lung disorder and an irreversible

obstruction in the respiratory tract potentially accompanied with

progressive decline in the function of lungs. The pathologies

include chronic bronchitis, airway remodeling and emphysema. One of

the major causes of COPD is smoking. There is a visible difference

between the gut microbiota of healthy smokers and non-smokers

(78). The intestinal levels of

Firmicutes are decreased and the count of Bacteroidetes increases

in smokers, whereas when an individual quits smoking, the effects

are vice versa. The production of SCFAs is highly variable between

smokers, non-smokers and in those who have quit smoking, and this

has direct response to the immune response exerted in the lungs.

The core microbiome of the lungs is mainly composed of

Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Prevotella, Fusobacterium,

Haemophilus, Veillonella and Porphyromonas; these also

play a protective role by producing SCFAs. For example, butyrate

secreted by the gut microbiota can reduce the lung damage caused by

cigarette smoke-induced-COPD, by inhibiting the mevalonate pathway

in the gut, lungs and liver. However, the inflammation/emphysema

pathological condition can be reduced by supplementing with a high

fiber diet and probiotic intake of Lactobacillus rhamnosus

and Bifidobacterium (79,80).

The lung microbiota of patients with COPD exhibits an increase in

Gammaproteobacteria, whereas healthy lungs exhibit

Bacteroidetes (81).

The lung microbiome is frequently assessed through

samples, such as serum, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF)

and lung tissue, whereas for the gut microbiome, fecal samples are

used. In a number of respiratory disease conditions, the spatial

heterogeneity in the composition of the lung microbiome is highly

variable; however, within an individual, the microbial spatial

variation is less among healthy populations and either the segment

of lingula or BALF from the right middle lobe are used for

microbial assessment (82). Of

note, in COPD the microbial diversity varies with the sampling from

upper and lower bronchial regions of the lung (83). Exacerbations of COPD, are often

caused by respiratory viruses or bacteria; these exacerbations are

associated with markedly increased morbidity and mortality rates

(84). Studies on the dynamics of

the microbiome in different exacerbation phenotypes have indicated

that diverse patterns of microbiota existence are associated with

the types of exacerbation events (types 1, 2 and 3) (85,86).

Therefore, for the understanding of disease etiology, associated

changes in the microbial community and cytokine profiles are key

features to be explored towards the development of more effective

therapeutic strategies. The microbial niches and their associated

mediators of inflammation for Haemophilus are IL-1β and

tumor necrosis factor-α in sputum, as well as neutrophilic

inflammation and Moraxella, which are related to Th1

pathways such as interferon signaling (87). The evaluation of the gut microbiome

does not indicate the severity of COPD; however, the varied

prevalence of microbiota at different stages of COPD has been

observed (88). Diet plays a major

role in maintaining microbial diversity; mortality rates due to

COPD have been found to increase with western diets and may be

reduced among populations consuming diets rich in antioxidants and

fiber (88).

Medications for COPD include antibiotics, steroids

and the use of bronchodilators, which exert effects on microbial

composition. Recent day challenges, such as the emergence of

multidrug resistance for several antibiotics and metal-based drugs

with the capability of modulating the microbiome in COPD have been

previously discussed (71). A

comprehensive elucidation of the existing evidence, challenges and

the future concerns regarding the possible use of the lung

microbiome either as a potential biomarker or therapeutic target

for COPD has been previously provided (89). The microbial distribution of the

lung and gut in COPD has also bene previously detailed (83).

COPD and asthma are the two most frequently

diagnosed chronic respiratory diseases and it has been suggested

that the oral, lung and gut microbiota are associated with these

conditions. Asthma is a multifactorial and heterogeneous disease

characterized by the presence of airflow limitation associated with

chronic bronchitis or emphysema. Microbiota composition in the

respiratory tract mainly consists of Actinobacteria, Firmicutes,

Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, etc. and it is suggested that the

development of allergic diseases such as asthma is dependent on

these, as they influence inflammation via the gut-lung axis

(90). As regards gut microbial

dysbiosis, the lower abundance of Firmicutes increases the risk of

asthma and as with COPD lung microbial composition,

Proteobacteria such as Haemophilus and

Moraxella are the predominant among the lung microbiome

(91).

Delivering probiotics orally has its own efficiency

in immune cell regulation in the respiratory system; the most

common probiotics include lactic acid-producing bacterial species

such as Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Bifidobacterium and

Enterococcus, as well as the non-pathogenic yeast,

Saccharomyces boulardii. The systemic immune modulating

capability of Lactobacilli has been found to affect the cytokine

profile, T-cell proliferation, and the phagocytic activity of

mononuclear cells and natural killer (NK) cells (92,93).

Research has demonstrated the involvement of immune cells like Th17

(T-helper) and Treg (regulatory T-cells), which indicates the role

of CD4+ T-cells in the production of pro-inflammatory

cytokines, as well as the transcription factor FoxP3 + CD4 cells in

the immune homeostasis. The administration of Lactobacillus

reuteri, Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12, Lacticaseibacillus

rhamnosus strain GG (LGG) and Lactobacillus casei

increase the levels of these immune cells (94,95).

In asthmatic conditions, the reduction of airway

hyperresponsiveness and the number of inflammatory cells in BALF

and in lung tissue have been reported with the supplementation of

Lactobacillus reuteri, LGG and Bifidobacterium breve

(96). Furthermore, probiotic

supplements with the heat-killed Mycobacterium vaccae confer

protection against airway allergic inflammation (97). Intaking Enterococcus

faecalis FK-23 attenuates TH17 cell development as an asthmatic

response, whereas NK cell impairment in lungs due to cigarette

smoking indicates an increase in NK cell activity with the

supplementation of Lactobacillus casei (98). The markers of systemic inflammation

and oxidative stress, such as plasma C-reactive proteins and

8-isoprostane are significantly reduced by probiotic treatment.

Moreover, multistrain probiotics stabilize the neuromuscular

junction by improvising muscle strength and its functional

performance by reducing the intestinal permeability (a randomized

controlled clinical trial no. GMC-CREC-00263) (99,100). The therapeutic application of the

gut bacteriome for the treatment of COPD and asthma has been

previously discussed (101).

The bacterium Parabacteroides goldsteinii

ameliorates COPD by reducing intestinal inflammation and enhancing

cellular mitochondrial activities, restoring the abnormal amino

acids metabolism through ribosomal activities. The derived

lipopolysaccharides of P. glodsteinii are efficient to

interact with Toll-like receptor (TLR)4 signaling pathways, thereby

acting as an anti-inflammatory agent (102). Similarly, the derived saponins of

the plant American ginseng have been reported to ameliorate COPD

(103). Butyrate has pleiotropic

functionality and has several beneficial effects on the maintenance

of homeostasis of the gut and lung microbiota. Despite the short

half-life of butyrate, rendering it a poor oral supplement for lung

disorders, a pre-clinical evaluation of the administration of

butyrate and metformin through inhalation was performed, to

directly target the lung (103).

COVID-19

COVID-19 is the recent pandemic caused by a virus

mainly affecting the respiratory tract. Recent research has

indicated the association between gut microbiome alterations and

COVID-19 severity, providing evidence that the translocation of

bacteria into blood is associated with gut microbiome dysbiosis

(104). This can lead to the

occurrence of secondary infections. In this recent study,

alterations in Paneth cells, goblet cells and markers of

permeability barriers in association with alterations in the gut

microbiome were observed. The gut-lung crosstalk is bidirectional,

where the metabolites produced by the altered gut microbes

transfuse through and exert affect the lungs, and lung inflammation

affects the gut microbiota, and vice versa (104). Angiotensin converting enzyme

(ACE2) is the enzyme that is located on the outer surface and

functions as the gateway for viral entry and it regulates

intestinal inflammation (105).

The components of the bacterial envelope (lipopolysaccharides and

peptidoglycans) facilitate the interaction of viral proteins, which

enhances thermostability in Polio and other viruses (106). This indicates the importance of

commensals in the increasing/decreasing of viral infections.

The gut microbiota of patients with COVID-19 are

abundant with opportunistic pathogens, such as Acinetobacter

baumannii and Candida spp. Furthermore, the functional

loss of ACE2 results in gut microbiome imbalance and a leaky gut.

These changes affect the host immune responses to SARS-CoV-2

infection (107). The pro- and

pre-biotic treatment for other viral influenza confirms their

potency to combat COVID-19. The flagellin of commensal bacteria are

capable of activating pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) of the

pathogen and stimulate the release of IL-18 and IL-22, which are

cytokine derivatives of the intestinal epithelium and significantly

contribute to host defense mechanisms against inflammation and

intestinal infection (108).

Treatment with retinoic acid mediates the production of interferons

through the bacterium Lactobacillus sp. and also increases

the antiviral activity of vitamin A (109,110). Gut commensal Clostridium

orbiscindens promotes host immune protection against influenza

infection by enhancing the type I interferon signaling (111). The antiviral role of TLRs are

scientifically proven mechanisms of host immune responses and the

gut commensal microbiomes are expected to activate the TLRs and the

release of antiviral protein cathelicidin from mast cells (112). Through TLR ligand stimulation,

the death rate due to viral infections is significantly reduced

with the restoring responses of interferon gamma and

CD4+ T-cell responses (113). The bacterial species

Lactobacillus paracasei and Lactobacillus plantarum

activate the release of the cytokine IL-10 and suppress the

inflammatory responses in the lungs (114,115).

Apart from bacterial balances within the gut, the

intra-kingdom crosstalk between fungi, virus and bacteria has a

marked influence in maintaining the gut homeostasis (116). A significant attenuation of

COVID-19 infection and a reduced risk of respiratory failure was

observed when patients were provided with standard medication and

additional supplements with bacterial strains (Bifidobacterium

longum, Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. Lactis and Lactobacillus

rhamnosus, in addition vitamin D, zinc and selenium); this

clinical trial was registered with the number NCT04666116(117).

Dietary fibers, such as fructans and

galactooligosaccharides increase the prevalence of

Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli (118). The intestinal commensals,

Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, which are essential

for inhibiting the colonization of pathogenic organisms in the gut

epithelial cells. Adhesin production by commensals and probiotic

supplements regenerates the intestinal mucosa, thereby suppressing

viral adhesion and replication, and reducing the risk of

respiratory tract infections. Peptides produced by

Lactobacillus and Paenibacillus block the binding of

SARS-CoV-2 with ACE2(119). The

lesions in the lung affects the gas exchange capability among

COVID-19-infected patients, where the probiotic formulation SLAB51

combats the breathing difficulty by reducing nitric oxide synthesis

within the gut (120).

Polyphenols of beverages and other foods favor the growth of

beneficial gut bacteria and provide intestinal barrier function

(120). The active clinical

trials for lung cancer, COPD, asthma and COVID-19 are presented in

Table II.

| Table IIActive clinical trials utilizing pre-

and probiotics for lung cancer, COPD, asthma and COVID-19

(https://clinicaltrials.gov/). |

Table II

Active clinical trials utilizing pre-

and probiotics for lung cancer, COPD, asthma and COVID-19

(https://clinicaltrials.gov/).

| Clinical Trial Gov.

identifier | Subject or

title |

|---|

| NCT04699721 | Clinical study of

neoadjuvant chemotherapy and immunotherapy combined with probiotics

in patients with potential/resectable NSCLC |

| NCT05094167 |

Lactobacillus Bifidobacterium

V9(Kex02) improving the efficacy of carilizumab combined with

platinum in non-small cell lung cancer |

| NCT03642548 | Probiotics combined

with chemotherapy for patients with advanced-stage NSCLC |

| NCT03068663 | Microbiota and the

lung cancer |

| NCT04871412 | The thoracic

peri-operative integrative surgical care evaluation trial- Stage II

(POISE) |

| NCT05037825 | The gut microbiome

and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in solid tumors

(PARADIGM) |

| NCT05303493 | Camu-Camu prebiotic

and immune checkpoint inhibition in patients with non-small cell

lung cancer and melanoma |

| NCT05492448 | Probiotic on type 2

diabetes and chronic obstruction pulmonary disease |

| NCT05126654 | Partially

hydrolyzed Guar Gum (PHGG) for amelioration of chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease (COPD) |

| NCT05523180 | A study to evaluate

the effect of probiotic supplement on quality of life |

| NCT04366089 | Oxygen-ozone as

adjuvant treatment in early control of COVID-19 progression and

modulation of the gut microbial flora (PROBIOZOVID) |

| NCT04368351 | Bacteriotherapy in

the treatment of COVID-19 (BACT-ovid) |

| NCT00298337 | Use of probiotic

bacteria in prevention of allergic disease in children

1999-2008 |

| NCT01419587 | Ketogenic diet with

chemoradiation for lung cancer (KETOLUNG) |

Bacterial pneumonia and its impact on

the gut microbiota

Bacterial pneumonia remains a leading cause of

respiratory illness and mortality worldwide, with treatment relying

heavily on antimicrobial agents (121). According to recent research, the

human gut microbiota plays a critical role in protecting the body

from infections due to antimicrobial resistance. The body is

protected by a balanced microbiota through defense mechanisms, such

as nutritional competition, niche exclusion, colonization

resistance by secreting antibacterial substances, restoring the

mucosal barrier, suppressing inflammation and immune modulation

etc., rendering it a vital ally in the battle against antimicrobial

resistance. However, this protection is compromised by gut

dysbiosis, which makes it easier for resistant infections to

persist, colonize and spread (122). While antibiotics are essential

for managing the infection, they can significantly disrupt the gut

microbiota, leading to dysbiosis and potential long-term health

consequences (123). Antibiotic

resistance genes are derived from the gut microbiome, which has

developed into a major part of the resistome. Antibiotics alter the

natural microbiota of the host by favoring resistant microorganisms

that may cause opportunistic illnesses (124). The dysbiosis in the upper

respiratory tract microbiome has been shown to be a major cause of

bacterial pneumonia in the elderly and in young adults (125). Gut dysbiosis may be linked to

subtherapeutic antibiotic treatment, the consumption of low-dosage

antibiotics from food and horizontal gene transfer, leading to gene

acquisition or loss, bacterial biofilms, quorum sensing and other

environment factors (125).

Commonly prescribed antibiotics, including β-lactams

(such as penicillins and cephalosporins), macrolides (such as

azithromycin and clarithromycin), fluoroquinolones (such as

levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin), tetracyclines and aminoglycosides,

have been shown to reduce microbial diversity and deplete

beneficial gut bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus. This disruption weakens immune function,

promotes the growth of opportunistic pathogens, and increases the

risk of developing antibiotic-resistant infections, such as

Clostridium difficile. Over time, these alterations can

contribute to metabolic disorders and chronic health issues

(126). Restoring the gut balance

through probiotics, prebiotics, fecal microbiota transplantation

and dietary interventions may help mitigate these effects and

support overall gut and immune health.

7. OMICS techniques: Metagenomics,

metatranscripto-mics, metaproteomics and metabolomics

The human intestine is colonized by >1,000

microbial species. The gut microbial community plays a critical

role in the protection of the host against pathogenic microbes,

modulating immunity and regulating metabolic processes (127,128). Since the beginning of microscopy,

several human gut microbial communities have been identified.

Recent technological advances in genomics and microbial genetics

have led to the identification of human microbiota associated with

various diseases.

Molecular biological technology plays a vital role

in the intestinal microbiome analysis; in particular, metagenomic

sequencing using the next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques

has led to notable developments in the study of the human gut

microbiome. Metagenomics is widely used in the study of human gut

microbiome diversity and to gain the knowledge of its insight with

relation to various diseases, as well as its association with

health and disease (129,130). This aids in the identification of

taxonomic identification, and in the detection and characterization

of microbial species (131).

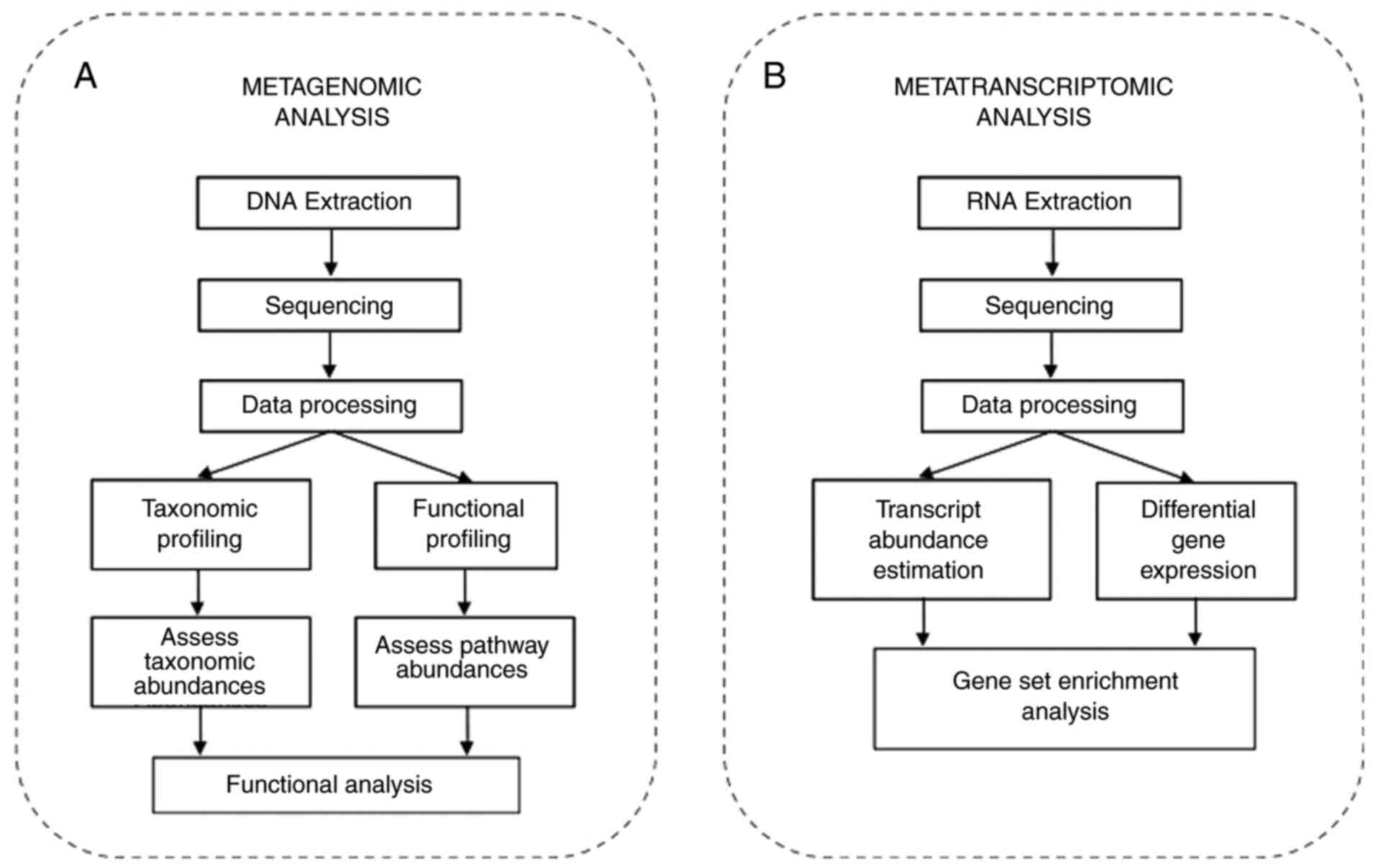

Metagenomic analysis involves the extraction of genomic DNA and

sequencing. The next step involves annotation after assembly and

the mapping of sequences to the reference database (Fig. 2A). Further, computational

annotation is performed using bioinformatics tools, such BLAST, COG

and KEGG, and statistical analysis can be performed using R and

Bioconductor (132,133).

The application of metagenomics involves the

identification of novel functional genes, microbial pathways,

antibiotic resistance genes, functional dysbiosis of the intestinal

microbiome, and the determination of interactions and co-evolution

between microbiota and host (134,135). Although the complete bacterial

repertoire of the human microbiome is unidentified, the study by

Almeida et al (136)

provided information of a vast diversity of uncultured gut

bacteria, and supports the expansion of the gut microbiome

repertoire of the human gut microbiota. Metagenomics also enables

the profiling of whole gene repertoire and plays a vital role in

the pan-genomic analyses and also enables the identification of

whole genome content from a sample and determination of closely

related taxa (137).

Metatranscriptomics involves the sequencing of the

complete transcriptome of the microbial community and determines

the genes that are expressed by the microbiome and helps determine

the functional profile of the community under different conditions

(138). In brief, metagenomics

helps to identify the composition of a microbial community under

different conditions, while metatranscriptomics helps identify the

genes that are collectively expressed under different conditions

(139). A metatranscriptome

experiment involves the isolation of total RNA from a sample and

its sequencing followed by annotation, assembly and bioinformatics

analysis (140), as illustrated

in Fig. 2B.

Other novel omics approaches, such as

metatranscriptomics (141),

metaproteomics (142) and

metabolomics (143) also

complement the study of the human gut microbiome and support the

identification of the microbiota community. Metaproteomics provides

the knowledge of the entire protein complement of the microbiota

communities, provides insight into the genes expressed and helps in

the identification of the key metabolic activities (144). Metabolomics provides details of

the metabolite composition of the microbiota community, and

provides an understanding of the functional dynamics of the

microbiome community and the host interactions (145). A brief comparison of the

different omics techniques, including advantages and disadvantages

to understand the choices and limitations of each approach is

provided in Table III.

| Table IIIA brief comparison of the different

omics techniques. |

Table III

A brief comparison of the different

omics techniques.

| Omics

techniques | What is

analyzed | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|

| Metagenomics | DNA (microbial

genomes) | Identifies

microbial composition and potential functional genes. | Does not indicate

active gene expression; unable to assess actual function. |

|

Metatranscriptomics | RNA (microbial

transcripts) | Captures gene

expression and functional activity under specific conditions. | RNA is unstable;

requires careful sample handling; highly dynamic and

contextual. |

| Metaproteomics | Proteins (microbial

proteome) | Provides direct

evidence of expressed proteins and metabolic function. | Technically

challenging; limited by protein extraction and database

completeness. |

| Metabolomics | Metabolites (small

molecule end-products) | Reflects functional

output of microbiome and host-microbe interactions. | Difficult to link

metabolites to specific microbes; complex data interpretation. |

8. Machine learning for the development of

microbiome therapeutics

Machine learning is an artificial intelligence (AI)

technique that focuses on developing the intelligence to imitate

humans for analyzing a large volume of data. The technique is

widely applied to answer various biological and biomedical queries

including the microbiome field. A simple boolean search using the

query ‘gut microbiome’ and ‘machine learning’ retrieved 513 PubMed

articles (on May 31, 2025). The first article was published in 2013

and the study focused on predicting the genes in metagenomic

fraction by using support vector machines (SVM), one of the

standard machine learning approaches for classification (146). The authors of that study

presented a novel gene prediction method called MetaGUN and

included three different stages: i) classifying the fragments into

different phylogenetic groups with k-mer based sequence binding

approach; ii) identifying protein coding sequences from each

phylogenetic group using SVM that uses entropy density profiles,

translation initiation site, and open reading frame length as input

patterns; and iii) adjusting the translation initiation site

(146).

Human health is greatly affected by the gut

microbiota, which affects immune responses, metabolism and disease

prevention. Numerous diseases, including cancer, are associated

with microbial imbalance, or dysbiosis, a key observation that can

be utilized for the early detection of disease. AI methods are well

suited for large-scale biomedical big data mining, including

microbiome data mining. Foundation models and transfer learning (ML

and DL models) have been shown to have immense success with

microbiome-based classification and prediction (147). Random Forest (RF), an ensemble

learning technique, has been used for feature selection and

classification in microbiome datasets to identify key microbial

taxa associated with diseases such as type 2 diabetes and

inflammatory bowel disease (148). SVMs and other machine learning

techniques have markeldy enhanced the predictive power of cancer

diagnosis and prognosis, especially in research involving gut

microbiota. When trying to understand the complex interaction

between the gut microbiota and cancer prevention, the SHapley

Additive exPlanations (SHAP) algorithm is a crucial part of the

eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) architecture (146,149). Machine learning models such as

Ridge regression, Elastic Net, LASSO, Random Forest, Ridge

regression and LASSO were constructed using the SIAMCAT v_2.0 and

v_2.10 toolbox and have been used to accurately classify patients

with Parkinson's diasease, with an average AUC of 71.9%. However,

it was found that the trained models were study-specific and do not

generalize well to datasets from other neurodegenerative diseases

research (150). The increasing

application of these varied algorithms highlights their potential

for improving integrative multi-omics analysis, precision medicine

and microbiome-based diagnostics.

Recent research has focused on disease prediction

(151-153),

the association between the gut microbiome and disease (e.g.

obesity, constipation, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases)

(154-157),

the epigenetic regulation of brain disorders (158), and the role of the gut microbiome

in promoting precision medicine for cancer (159). The interaction between the gut

microbiome and the intestinal cells is well known. Recently, the

interaction between the gut microbiome and nervous system,

particularly the enteric nervous system and central nervous system

has gained increasing attention among researchers and neurologists

(158). Studies have shown the

involvement of the gun microbiome in anxiety (160), autism (161), depression (162), and a number of neurodegenerative

diseases (163-167).

The influence of the gut microbiome on the host metabolism by

activating epigenetic regulators plays a crucial role in

understanding the pathogenesis of numerous neurological disorders,

including brain disorders (143).

The integration of multi-omics data, including genomics,

metabolomics, connectomics and gut microbiome multi-omics can

provide a path for moving forward towards the prevention of disease

and for the development of personalized therapeutics, as opposed to

merely the prediction of diseases. Both supervised and unsupervised

machine learning approaches can be used for such studies (158). Thus, machine learning approaches

find a wide range of applications in gut microbiome research.

9. Conclusion and future perspectives

Respiratory diseases are markedly affected both by

genetic and external factors. Where the genetic factors are

difficult to control, the immunological response to the

environmental factors can be mediated. In this regard, the human

microbiota serves as a source towards this approach. The health of

the gut microbiota is sustained with fibrous food intake,

probiotics, etc. This cascades the immunological response in

chronic respiratory diseases. The omics approach provides details

of the metabolite composition and provides an understanding of the

functional dynamics of the microbiome community and host

interactions. The association between diet and the gut microbiome

is analyzed using machine learning approaches, and much of the

hidden information in literature can be explored using text mining

approaches. This survey highlights the diagnostic aspects of

personalized medicine based on the gut-lung axis microbiome of an

individual by integrating various areas of research, such as

molecular biology, immunology, omics, machine learning and text

mining.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

All the authors (SM, ORI, AP, BB and KR) were

involved in the conceptualization of the study. All the authors

(SM, ORI, AP, BB and KR) were also involved in the formal analysis

(collecting the relevant data and articles from the literature), in

the writing and preparation of the original draft of the

manuscript, and in the writing, review and editing of the

manuscript. SM, ORI and AP were involved in visualization

(preparation of the figures). KR supervised the study. All authors

have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Miedema I, Feskens EJ, Heederik D and

Kromhout D: Dietary determinants of long-term incidence of chronic

nonspecific lung diseases. The zutphen study. Am J Epidemiol.

138:37–45. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Wilson DO, Donahoe M, Rogers RM and

Pennock BE: Metabolic rate and weight loss in chronic obstructive

lung disease. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 14:7–11.

1990.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Han SN and Meydani SN: Vitamin E and

infectious diseases in the aged. Proc Nutr Soc. 58:697–705.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Tabak C, Feskens EJ, Heederik D, Kromhout

D, Menotti A and Blackburn HW: Fruit and fish consumption: A

possible explanation for population differences in COPD mortality

(The Seven Countries Study). Eur J Clin Nutr. 52:819–825.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

DeMeo MT, Van de Graaff W, Gottlieb K,

Sobotka P and Mobarhan S: Nutrition in acute pulmonary disease.

Nutr Rev. 50:320–328. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ellis JA: The immunology of the bovine

respiratory disease complex. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract.

17:535–550, vi-vii. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Furrie E: Probiotics and allergy. Proc

Nutr Soc. 64:465–469. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Behrouzi A, Nafari AH and Siadat SD: The

significance of microbiome in personalized medicine. Clin Transl

Med. 8(16)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hou K, Wu ZX, Chen XY, Wang JQ, Zhang D,

Xiao C, Zhu D, Koya JB, Wei L, Li J and Chen ZS: Microbiota in

Health and Diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

7(135)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Liu XF, Shao JH, Liao YT, Wang LN, Jia Y,

Dong PJ, Liu ZZ, He DD, Li C and Zhang X: Regulation of short-chain

fatty acids in the immune system. Front Immunol.

14(1186892)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Brittain HK, Scott R and Thomas E: The

rise of the genome and personalised medicine. Clin Med (Lond).

17:545–551. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lin BM, Grinde KE, Brody JA, Breeze CE,

Raffield LM, Mychaleckyj JC, Thornton TA, Perry JA, Baier LJ, de

las Fuentes L, et al: Whole genome sequence analyses of eGFR in

23,732 people representing multiple ancestries in the NHLBI

trans-omics for precision medicine (TOPMed) consortium.

EBioMedicine. 63(103157)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kowalski MH, Qian H, Hou Z, Rosen JD,

Tapia AL, Shan Y, Jain D, Argos M, Arnett DK, Avery C, et al: Use

of >100,000 NHLBI trans-omics for precision medicine (TOPMed)

consortium whole genome sequences improves imputation quality and

detection of rare variant associations in admixed African and

hispanic/latino populations. PLoS Genet.

15(e1008500)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Eichler EE: Genetic variation, comparative

genomics, and the diagnosis of disease. N Engl J Med. 381:64–74.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Khan I, Bai Y, Zha L, Ullah N, Ullah H,

Shah SRH, Sun H and Zhang C: Mechanism of the gut microbiota

colonization resistance and enteric pathogen infection. Front Cell

Infect Microbiol. 11(716299)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Arapidi GP, Urban AS, Osetrova MS, Shender

VO, Butenko IO, Bukato ON, Kuznetsov AA, Saveleva TM, Nos GA,

Ivanova OM, et al: Non-human peptides revealed in blood reflect the

composition of small intestine microbiota. BMC Biol.

22(178)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Davis OK and Rosenwaks Z: Personalized

medicine or ‘one size fits all’? Fertil Steril. 101:922–923.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

NIH HMP Working Group. Peterson J, Garges

S, Giovanni M, McInnes P, Wang L, Schloss JA, Bonazzi V, McEwen JE,

Wetterstrand KA, et al: The NIH human microbiome project. Genome

Res. 19:2317–2323. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Sender R, Fuchs S and Milo R: Revised

estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body.

PLoS Biol. 14(e1002533)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Martinez FJ, Erb-Downward JR and Huffnagle

GB: Significance of the microbiome in chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 10 (Suppl 1):S170–S179. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Kamel M, Aleya S, Alsubih M and Aleya L:

Microbiome dynamics: A paradigm shift in combatting infectious

diseases. J Pers Med. 14(217)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Druszczynska M, Sadowska B, Kulesza J,

Gąsienica-Gliwa N, Kulesza E and Fol M: The intriguing connection

between the gut and lung microbiomes. Pathogens.

13(1005)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Belaid A, Roméo B, Rignol G, Benzaquen J,

Audoin T, Vouret-Craviari V, Brest P, Varraso R, von Bergen M, Hugo

Marquette C, et al: Impact of the lung microbiota on development

and progression of lung cancer. Cancers (Basel).

16(3342)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Borges RM, Colby SM, Das S, Edison AS,

Fiehn O, Kind T, Lee J, Merrill AT, Merz KM Jr, Metz TO, et al:

Quantum chemistry calculations for metabolomics. Chem.Rev.

121:5633–5670. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Natalini JG, Singh S and Segal LN: The

dynamic lung microbiome in health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol.

21:222–235. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kennedy MS and Chang EB: The microbiome:

Composition and locations. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 176:1–42.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Budden KF, Shukla SD, Rehman SF, Bowerman

KL, Keely S, Hugenholtz P, Armstrong-James DPH, Adcock IM,

Chotirmall SH, Chung KF and Hansbro PM: Functional effects of the

microbiota in chronic respiratory disease. Lancet Respir Med.

7:907–920. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Ritchie AI and Wedzicha JA: Definition,

causes, pathogenesis, and consequences of chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease exacerbations. Clin Chest Med. 41:421–438.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wang L, Cai Y, Garssen J, Henricks PAJ,

Folkerts G and Braber S: The bidirectional gut-lung axis in chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.

207:1145–1160. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Rastogi S, Mohanty S, Sharma S and

Tripathi P: Possible role of gut microbes and host's immune

response in gut-lung homeostasis. Front Immunol.

13(954339)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Liu Y, Teo SM, Méric G, Tang HHF, Zhu Q,

Sanders JG, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Verspoor K, Vartiainen VA, Jousilahti

P, et al: The gut microbiome is a significant risk factor for

future chronic lung disease. J Allergy Clin. Immunol. 151:943–952.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P

and Bäckhed F: From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain

fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 165:1332–1345.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Wu W, Sun M, Chen F, Cao AT, Liu H, Zhao

Y, Huang X, Xiao Y, Yao S, Zhao Q, et al: Microbiota metabolite

short-chain fatty acid acetate promotes intestinal IgA response to

microbiota which is mediated by GPR43. Mucosal Immunol. 10:946–956.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Deguen S, Amuzu M, Simoncic V and

Kihal-Talantikite W: Exposome and social vulnerability: An overview

of the literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

19(3534)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Wiertsema SP, van Bergenhenegouwen J,

Garssen J and Knippels LMJ: The interplay between the gut

microbiome and the immune system in the context of infectious

diseases throughout life and the role of nutrition in optimizing

treatment strategies. Nutrients. 13(886)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Yang L, Yuan TJ, Wan Y, Li WW, Liu C,

Jiang S and Duan JA: Quorum sensing: A new perspective to reveal

the interaction between gut microbiota and host. Future Microbiol.

17:293–309. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Xiao Y, Zou H, Li J, Song T, Lv W, Wang W,

Wang Z and Tao S: Impact of quorum sensing signaling molecules in

gram-negative bacteria on host cells: Current understanding and

future perspectives. Gut Microbes. 14(2039048)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Kho ZY and Lal SK: The human gut

microbiome-A potential controller of wellness and disease. Front

Microbiol. 9(1835)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Dubourg G, Lagier JC, Armougom F, Robert

C, Audoly G, Papazian L and Raoult D: High-level colonisation of

the human gut by verrucomicrobia following broad-spectrum

antibiotic treatment. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 41:149–155.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Markus V, Paul AA, Teralı K, Özer N, Marks

RS, Golberg K and Kushmaro A: Conversations in the Gut: The role of

quorum sensing in normobiosis. Int J Mol Sci.

24(3722)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Tomova A, Bukovsky I, Rembert E, Yonas W,

Alwarith J, Barnard ND and Kahleova H: The Effects of vegetarian

and vegan diets on gut microbiota. Front Nutr. 6(47)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Nagata N, Takeuchi T, Masuoka H, Aoki R,

Ishikane M, Iwamoto N, Sugiyama M, Suda W, Nakanishi Y,

Terada-Hirashima J, et al: Human gut microbiota and its metabolites

impact immune responses in COVID-19 and its complications.

Gastroenterology. 164:272–288. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Fusco W, Lorenzo MB, Cintoni M, Porcari S,

Rinninella E, Kaitsas F, Lener E, Mele MC, Gasbarrini A, Collado

MC, et al: Short-chain fatty-acid-producing bacteria: Key

components of the human gut microbiota. Nutrients.

15(2211)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Maslowski KM and Mackay CR: Diet, gut

microbiota and immune responses. Nat Immunol. 12:5–9.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK,

Venema K, Reijngoud DJ and Bakker BM: The role of short-chain fatty

acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host

energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 54:2325–2340. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Miller TL and Wolin MJ: Pathways of

acetate, propionate, and butyrate formation by the human fecal

microbial flora. Appl Environ Microbiol. 62:1589–1592.

1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Martino C, Zaramela LS, Gao B, Embree M,

Tarasova J, Parker SJ, Wang Y, Chu H, Chen P, Lee KC, et al:

Acetate reprograms gut microbiota during alcohol consumption. Nat

Commun. 13(4630)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Priyadarshini M, Kotlo KU, Dudeja PK and

Layden BT: Role of short chain fatty acid receptors in intestinal

physiology and pathophysiology. Compr Physiol. 8:1091–1115.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Nogal A, Louca P, Zhang X, Wells PM,

Steves CJ, Spector TD, Falchi M, Valdes AM and Menni C: Circulating

levels of the short-chain fatty acid acetate mediate the effect of

the gut microbiome on visceral fat. Front Microbiol.

12(711359)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Louis P and Flint HJ: Formation of

propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ

Microbiol. 19:29–41. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Canani RB, Costanzo MD, Leone L, Pedata M,

Meli R and Calignano A: Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in

intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol.

17:1519–1528. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Peredo-Lovillo A, Romero-Luna HE and

Jiménez-Fernández M: Health promoting microbial metabolites

produced by gut microbiota after prebiotics metabolism. Food Res

Int. 136(109473)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Slavin J: Fiber and prebiotics: Mechanisms

and health benefits. Nutrients. 5:1417–1435. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Ramirez-Olea H, Reyes-Ballesteros B and

Chavez-Santoscoy RA: Potential application of the probiotic as an

adjuvant in the treatment of diseases in humans and animals: A

systematic review. Front Microbiol. 13(993451)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Markowiak P and Śliżewska K: Effects of

probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on human health. Nutrients.

9(1021)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Luo Y, De Souza C, Ramachandran M, Wang S,

Yi H, Ma Z, Zhang L and Lin K: Precise oral delivery systems for

probiotics: A review. J Control Release. 352:371–384.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Cui L, Morris A, Huang L, Beck JM, Twigg

HL III, von Mutius E and Ghedin E: The microbiome and the lung. Ann

Am Thorac Soc. 11 (Suppl 4):S227–S232. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Vijay A and Valdes AM: Role of the gut

microbiome in chronic diseases: A narrative review. Eur J Clin

Nutr. 76:489–501. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Chen S, Kuhn M, Prettner K, Yu F, Yang T,

Bärnighausen T, Bloom DE and Wang C: The global economic burden of

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for 204 countries and

territories in 2020-50: A health-augmented macroeconomic modelling

study. Lancet Glob Health. 11:e1183–e1193. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Xiong T, Bai X, Wei X, Wang L, Li F, Shi H

and Shi Y: Exercise rehabilitation and chronic respiratory

diseases: effects, mechanisms, and therapeutic benefits. Int J

Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 18:1251–1266. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Mattiuzzi C and Lippi G: Worldwide asthma

epidemiology: Insights from the global health data exchange

database. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 10:75–80. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Halpin DMG, Faner R, Sibila O, Badia JR

and Agusti A: Do chronic respiratory diseases or their treatment

affect the risk of SARS-CoV-2 Infection? Lancet Respir Med.

8:436–438. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Weinberg F, Dickson RP, Nagrath D and

Ramnath N: The lung microbiome: A central mediator of host

inflammation and metabolism in lung cancer patients? Cancers

(Basel). 13(13)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Millen BE, Abrams S, Adams-Campbell L,

Anderson CA, Brenna JT, Campbell WW, Clinton S, Hu F, Nelson M,

Neuhouser ML, et al: The 2015 dietary guidelines advisory committee

scientific report: Development and major conclusions. Adv Nutr.

7:438–444. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Cheng CW, Biton M, Haber AL, Gunduz N, Eng

G, Gaynor LT, Tripathi S, Calibasi-Kocal G, Rickelt S, Butty VL, et

al: Ketone body signaling mediates intestinal stem cell homeostasis

and adaptation to diet. Cell. 178:1115–1131.e15. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Tan-Shalaby J: Ketogenic diets and cancer:

Emerging evidence. Fed Pract. 34 (Suppl 1):37S–42S. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Vieira RS, Castoldi A, Basso PJ, Hiyane

MI, Câmara NOS and Almeida RR: Butyrate attenuates lung

inflammation by negatively modulating Th9 cells. Front Immunol.

10(67)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Zhao H and Jin X: Causal associations

between dietary antioxidant vitamin intake and lung cancer: A

mendelian randomization study. Front Nutr. 9(965911)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Hagihara M, Kato H, Yamashita M, Shibata