1. Introduction

Morbidity and mortality rates associated with

diabetes mellitus (DM) are high and result from

hyperglycemia-related complications that can develop in various

organ systems. The mechanisms involved in the development of

complications are versatile and varied, with each complication

being organ-specific (1). Diabetic

neuropathy (DNP) is one of the most prevalent complications of DM,

which affects >50% of individuals with long-standing DM. It is a

microvascular complication characterized by pain and high morbidity

rates, mostly caused by damage to the somatosensory nervous system.

The longevity of diabetes and hemoglobin A1c levels are two key

predictors of DNP. The latter is often linked to poor glycemic

control, genetic predisposition, environmental variables, metabolic

factors and cardiovascular risk factors (2).

Even though there are several factors at play in the

development of DNP and the precise pathogenic process remains

unknown, numerous theories can be described. Hyperglycemia and a

complex metabolic imbalance, primarily oxidative stress (OS), are

current hypotheses (3). Since

neurons obtain glucose via facilitated concentration-dependent

transport, they are probably more vulnerable to glucose flow, which

leads to elevated levels of OS. The polyol pathway, diacylglycerol

(DAG)/protein kinase C (PKC), hexosamine biosynthetic pathway

(HBP), advanced glycation end products (AGEs)/inflammation and

nitric oxide all play critical roles in DNP. Evidence suggests that

OS plays a role in each of the aforementioned pathways (4-6).

Despite concerted efforts to detect and prevent the

progression of DNP, there are presently only a limited number of

alleviative medications available; the remainder essentially

provide symptomatic improvement. In the meantime, the present

objective of DNP treatment is to improve quality of life and

functionality of patients, while reducing pain. However, beyond

glycemic control, several antidiabetic medications can alleviate

DNP and prevent its progression (7-9).

The aim of the present review was to synthesize currently available

knowledge on OS-related mechanisms in DNP, while critically

appraising the evidence on the antioxidant potential of various

antidiabetic drug classes. By integrating mechanistic insights with

clinical outcomes, the present review aimed to bridge the gap

between basic the pathophysiological understanding and therapeutic

applications for this condition. Unlike prior reviews, the present

review discusses antidiabetic agents, such as metformin,

pioglitazone, dapagliflozin and others, with emphasis on OS

modulation and mechanistic pathways linked to diabetic neuropathy

and integrates clinical prescribing recommendations, providing a

practical translation of mechanistic insights into the management

of diabetes.

2. Clinical spectrum of DNP

The dorsal root ganglia neurons are subjected to

systemic metabolic and hypoxic stresses, rendering them very

sensitive to damage. The structure of the sensory system outside

the blood-brain barrier may also explain its extraordinary

vulnerability. DNP presents as a diffuse neuropathy (distal

symmetrical polyneuropathy or autonomic neuropathy), as well as

mononeuropathy or radiculopathy/polyradiculopathy. Distal symmetric

polyneuropathy (DSPN), the most common form of DNP, is mostly

accompanied by pain and distal sensory loss. However, approximately

half of the patients do not experience any symptoms (10). The symptoms are usually manifested

as a perception of tingling, numbness, sharpness, or burning that

begins in the feet and extends proximally. The clinical feature of

DSPN is that symptoms manifest in the lower extremities at rest and

worsen at night. Paresthesia, hyperesthesia and dysesthesia may

also occur. The pain becomes less severe over time with DSPN;

however, there is still a loss of sensory function, and motor

dysfunction may appear (11).

Another form of DNP is autonomic neuropathy, which

is presented as autonomic dysfunction and is manifested in patients

with long-term DM, affecting both the parasympathetic and

sympathetic nervous systems. Thus, it can affect a number of

systems, including the cardiovascular system. Complications of

cardiac autonomic neuropathy include resting tachycardia, exercise

intolerance, orthostatic hypotension associated with dizziness,

silent myocardial ischemia and an increased risk of sudden death

syndrome. Other systems that are also affected include the

gastrointestinal (bloating, diarrhea, or constipation),

genitourinary (infections, bladder dysfunction, or sexual

dysfunction) and metabolic (sweating abnormalities, and trouble

identifying low blood sugar) systems (12). Mononeuropathy, a less prevalent

form of DNP, manifests as a painful sensation and a lack of

strength in the muscles along with motor dysfunction in a

particular nerve. Mononeuropathy involves the malfunctioning of

isolated cranial or peripheral nerves and may be non-compressive or

arise at entrapment sites such as as the carpal tunnel. Other

examples of peripheral mononeuropathies include ulnar neuropathy at

the elbow, peroneal neuropathy at the fibular head, radial

neuropathy causing wrist drop, and femoral neuropathy with

quadriceps weakness (13).

3. Oxidative stress in diabetes

OS describes a condition when there is an imbalance

between the generation of oxidants inside the body and the

endogenous antioxidant system. Free radicals or other oxidants

mediate OS. Free radicals include reactive oxygen species (ROS),

which are the most critical, and reactive nitrogen species (RNS).

Previous population studies on DM and its chronic complications

have provided evidence of an association between DM and OS

(14-16).

ROS are naturally occurring oxygen-containing free

radicals that result from oxygen metabolism as a byproduct. These

include hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anion radicals, hypochlorite,

oxygen singlet and hydroxyl radicals. They arise inside organelles,

such as the mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum and peroxisomes.

Mitochondrial OS impairs insulin signaling, leading to insulin

resistance, and contributes to pancreatic β-cell dysfunction and

death (15). When the protein

folding capacity of the endoplasmic reticulum is overwhelmed, it

triggers an unfolded protein response that, if prolonged, can lead

to inflammation and the apoptosis of insulin-producing cells and

insulin resistance. The dysfunction of peroxisomes worsens the

metabolic imbalances observed in diabetic patients and interferes

with insulin secretion. However, RNS comprise nitric oxide, the

nitroxyl ion, peroxynitrite anion, nitrosyl-containing compounds,

and organic hydroperoxide (17).

To blunt or scavenge the excessive generation of

ROS, and consequently OS, cells have a variety of defensive

mechanisms. Antioxidant enzymes, such as glutathione peroxidase,

catalase, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) are among these (18). Glutathione peroxidase eliminates

hydrogen peroxide and lipid peroxides via detoxification, whereas

SOD scavenges superoxide radicals by promoting their conversion

into hydrogen peroxide. Catalase catalyzes the decomposition of

hydrogen peroxide into oxygen and water. Hyperglycemia can suppress

the endogenous antioxidant defense system, which may alter the

activity of antioxidant enzymes. For instance, SOD is known to be

inactivated by increased hydrogen peroxide concentration, although

its activity may also be reduced by glycosylation of the enzyme

and/or loss of copper, an essential cofactor. OS in diabetic

patients may arise due to either an increase in the generation of

free radicals or a decline in the protective mechanisms of

antioxidants (19). Another

mechanism for scavenging the excessive generation of ROS is the

non-enzymatic antioxidants. These include metal-binding proteins

such as ferritin, which sequester pro-oxidant metals; glutathione,

a primary cellular reductant that neutralizes free radicals; uric

acid, a potent scavenger of hydroxyl radicals; melatonin, a potent

antioxidant and free radical scavenger that easily crosses cell

membranes; bilirubin, which provides lipophilic antioxidant

protection; and polyamines, which stabilize cellular structures and

directly scavenge ROS (20).

4. Mechanisms of oxidant generation in

DNP

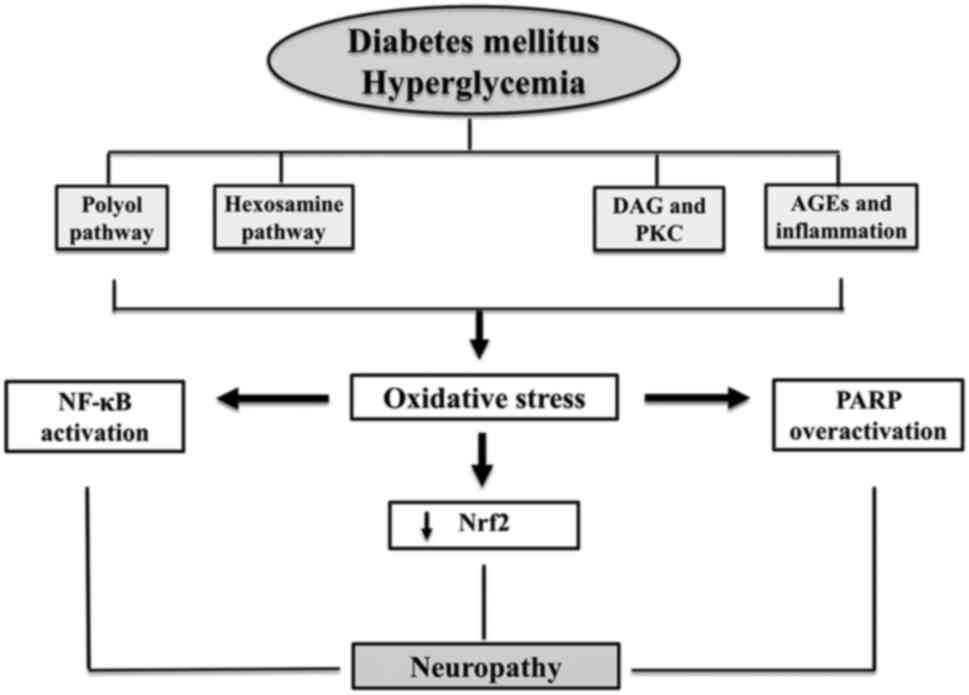

Evidence is presented to support the hypothesis that

both chronic and acute high blood sugar levels lead to OS in the

peripheral nervous system, which may contribute to the onset of

DNP. Various damaging molecular mechanisms may clarify the adverse

consequences of reactive oxidants in DNP generated by hyperglycemia

(Fig. 1). These mechanisms include

the polyol pathway and HBP, which have consistently been recognized

in patients with DNP. The AGE and PKC pathways exert direct or

indirect effects on proteins, lipids, and DNAs via glucose. All

these are associated with DNP through the excessive production of

ROS, a distinguishing characteristic found in all cell types

affected by hyperglycemia (21).

OS, when combined with hyperglycemia, triggers the

induction of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), which then breaks

down nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) into

nicotinamide and ADP-ribose fragments. This process proceeds via

the interaction with nuclear proteins, leading to alterations in

gene expression and transcription, depletion of NAD+,

and the redirection of glycolytic products towards other

disease-causing mechanisms, such as PKC and AGEs (21,22).

Activated polyol pathway

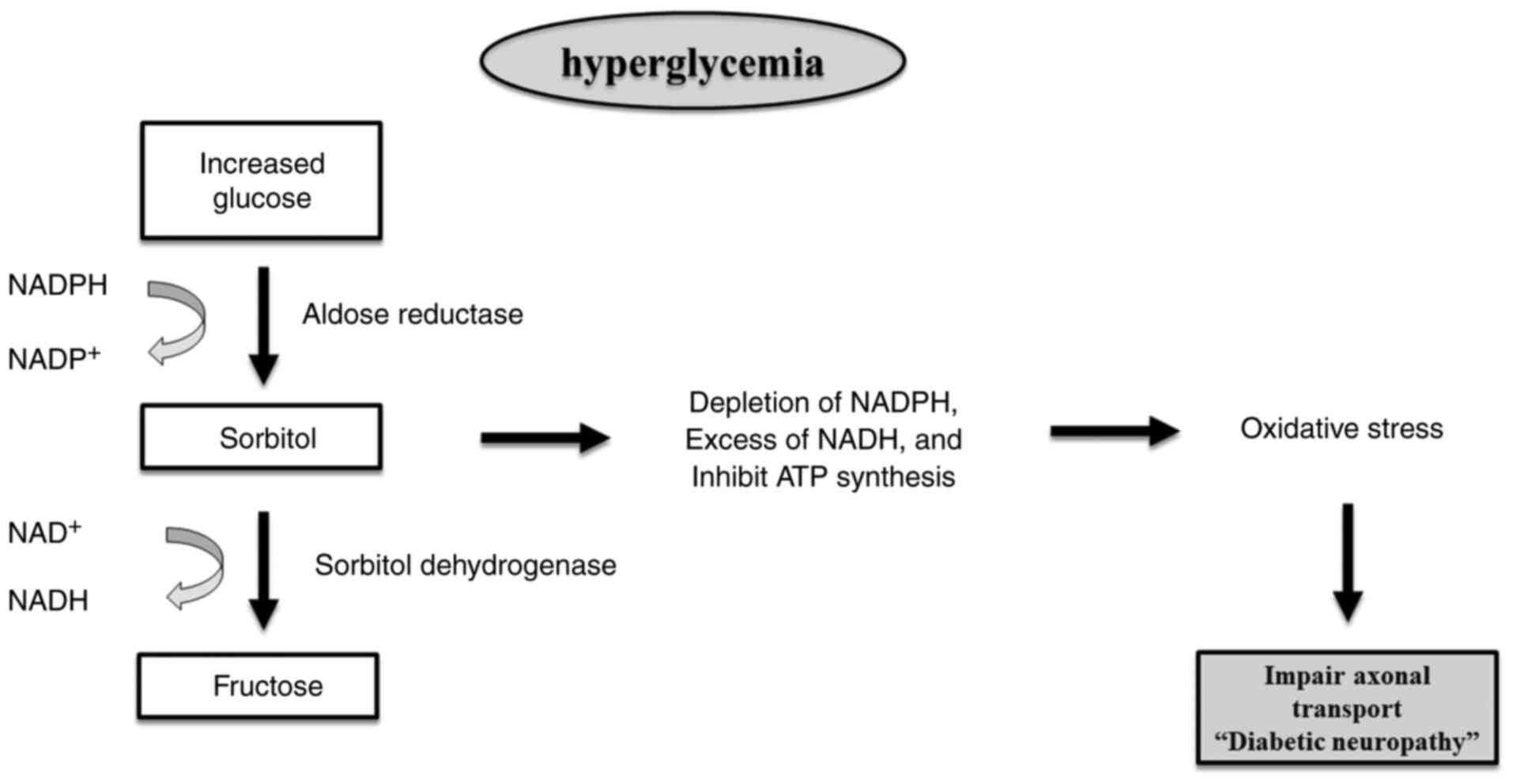

Under conditions of hyperglycemia, excess glucose

saturates glycolysis in nerve cells, diverting it into the polyol

pathway (Fig. 2). This pathway,

involving aldose reductase and sorbitol dehydrogenase, converts

glucose to sorbitol and then fructose, consuming nicotinamide

adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and generating NADH. This

process markedly contributes to ROS production, driving OS

(23).

The polyol pathway results in a decline in

intracellular NADPH levels and an accumulation of NADH. The greater

production of NADH serves as a substrate for NADH oxidase, leading

to the production of ROS. Intracellular hyperosmolarity occurs due

to an elevated polyol flow, which leads to the buildup of

impermeable sorbitol and the efflux of other osmolytes.

Consequently, the inhibition of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)

production occurs (24). The

conversion of glucose to sorbitol by the action of aldose reductase

leads to the utilization of NADPH. Since NADPH is necessary for the

reformation of reduced glutathione, this process directly adds to

OS generation. Furthermore, the conversion of sorbitol into

fructose contributes to glycation, leading to reduced NADPH

availability and elevated AGEs, all of which contribute to a

significant disruption in redox balance (25).

As regards DNP, the peripheral nerves of diabetic

patients have been shown to exhibit an accumulation of sorbitol and

fructose. Additionally, the shunting of glycolytic intermediates to

the polyol pathway increases glycation and the generation of DAG in

the dorsal root ganglia. These processes minimize the activity of

Na+/K+-ATPase, suppressed axonal transport

and the structural deterioration of nerves, ultimately manifesting

as an abnormal action potential. Therefore, the suppression of the

polyol pathway remains a focal point for therapeutic development in

the control of diabetic neuropathy (26,27).

HBP

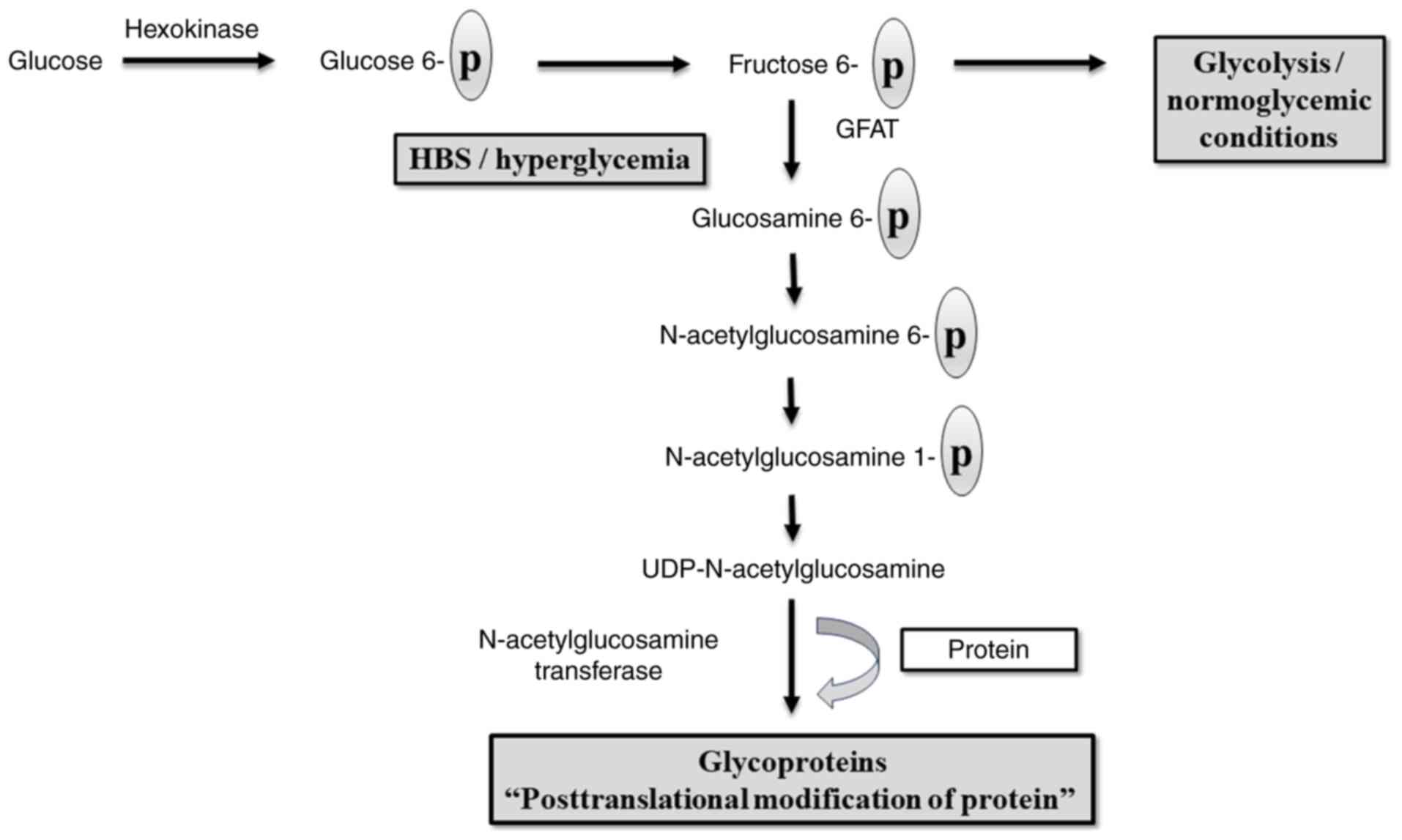

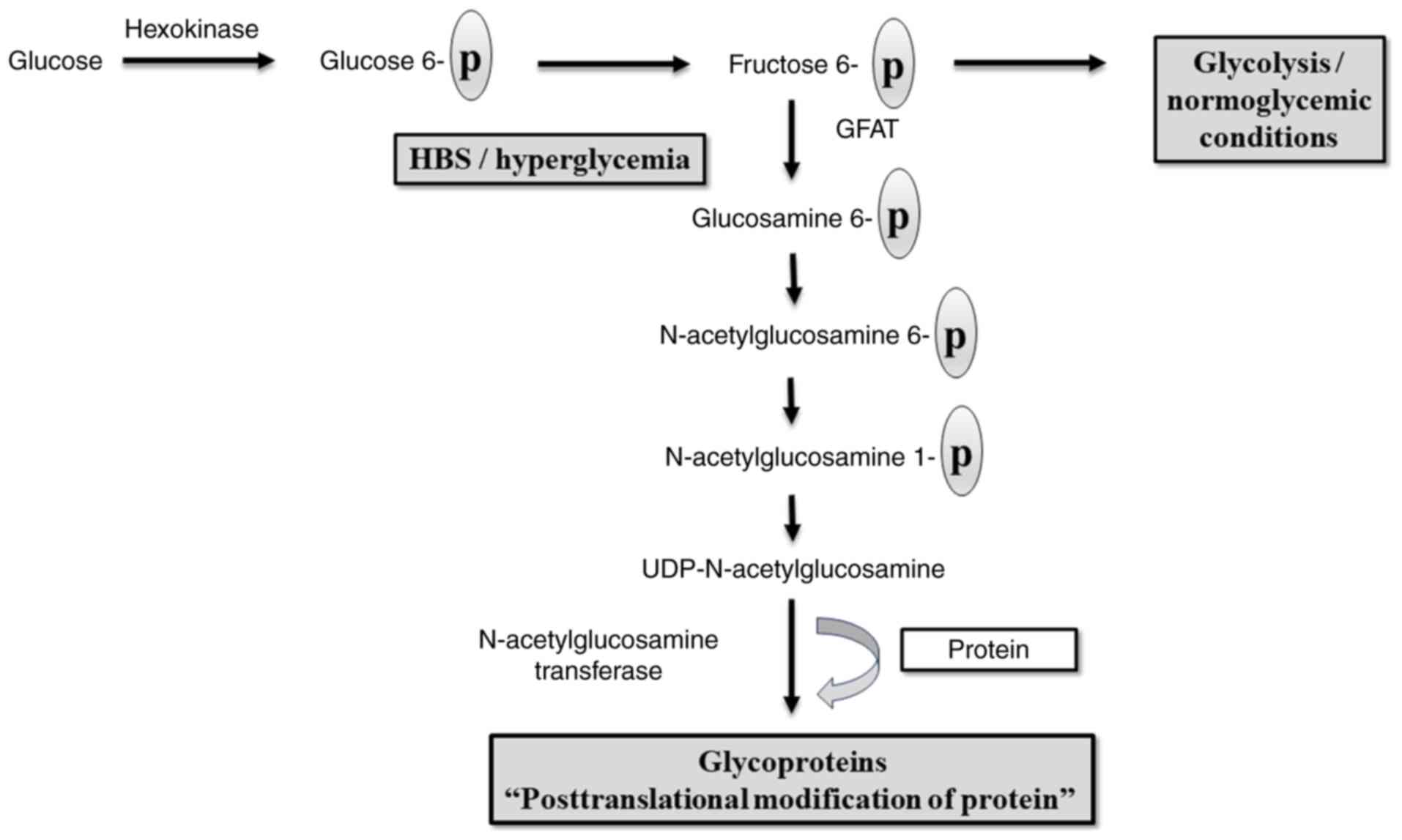

Diabetic complications, including DNP, may be caused

by the shunting of excess glucose in nerve cells into another

pathway rather than glycolysis, including the HBP, in addition to

the polyol pathway (28). The most

commonly proposed mechanism by which HBP contributes to DNP is the

effect of intracellular uridine-5-diphosphat-N-acetylglucosamine

(UDP-GlcNAc) on the modification of proteins (Fig. 3). Under healthy conditions, the HBP

represents a minor pathway of the glycolytic system, with

glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase (GFAT), the

rate-limiting enzyme, converting only 2 to 5% of

fructose-6-phosphate to glucosamine-6-phosphate (29).

| Figure 3Hexosamine biosynthetic pathway:

Under normal conditions, glucose undergoes a phosphorylation

process catalyzed by hexokinase, and phosphorylated glucose is

formed which is then converted to fructose that undergoes

glycolysis. In hyperglycemia, shifting from glycolysis into a

hexosamine biosynthetic pathway occurs resulting in the formation

of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine, the rate-limiting step is catalyzed by

GFAT. UDP-N-acetylglucosamine interferes with the action of

N-acetylglucosamine transferase, an enzyme that interferes with the

action of a number of proteins, including insulin receptor

substrate and glucose transporter protein (102,103). GFAT,

glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase; HBS, hexosamine

biosynthetic pathway; UDP, uridine diphosphate. |

However, under conditions of hyperglycemia, the

increased generation of ROS inside the mitochondria hinders the

action of the glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

dehydrogenase, which inhibits fructose-6-phosphate from flowing

through glycolysis (30).

Subsequently, UDP-GlcNAc is established from

glucosamine-6-phosphate, acetyl-CoA, and uridine-5-triphosphate.

UDP-GlcNAc regulates the activity of O-linked

N-acetylglucosamine transferase, which is present in both

the nucleus and cytosol. The latter is an enzyme that transfers

N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) to certain serine and threonine

residues on proteins, allowing for a reversible posttranslational

modification. Notable proteins that have undergone O-GlcNAcylation,

including glucose transporter 4 and insulin receptor substrates 1

and 2, result in insulin resistance (31,32).

Concerning DNP, there was a noticeable increase in

GFAT activity and UDP-GlcNAc levels in the muscle of ob/ob mice. By

contrast, mice with continuous caloric restriction exhibit a

decrease in the UDP-GlcNAc concentration, which is accompanied by

an improvement in insulin sensitivity in their muscles (33). Since peripheral nerves are highly

metabolically active and insulin-dependent, this disruption

directly links insulin resistance to neuronal injury, leading to

axon degeneration, demyelination, and ultimately, DNP. However, the

particular peripheral nerve proteins that can be altered by the

activated HBP in response to DM have yet to be identified.

Therefore, further investigations are required to fully elucidate

the interplay between HBP and DNP (21).

AGEs and inflammation

Hyperglycemia increases the formation of AGEs by

non-enzymatic reactions between reducing sugars and proteins,

nucleic acids, or lipids. These groups tend to impair the

biological activity of proteins, affecting cellular function. AGEs

promote modification through glycation of the extracellular matrix

protein laminin, which causes impaired regenerative activity in

DNP. In addition, AGEs induce segmental demyelination; as a result,

the nerves become susceptible to phagocytosis by macrophages.

Axonal atrophy, degeneration and impaired axonal transport are

consequences of AGE-modified major axonal cytoskeletal proteins

such as tubulin, neurofilamen and actin (34). In the peripheral nerves of

diabetics, the AGE receptor [receptor of advanced glycation end

products (RAGE)] has been shown to colocalize with AGEs. It appears

that AGEs and their interactions with RAGE cause OS in DNP

(35). Consequently, this leads to

an increase in nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and numerous

pro-inflammatory genes regulated by NF-κB. Furthermore, the blood

of individuals with DM contains inflammatory mediators, such as

C-reactive protein and TNF-α (5,36).

The combined effects of AGE-induced biochemical damage include

reduced neurotrophic support, nerve blood flow impairment, neuronal

integrity disruption and compromised repair mechanisms (37).

DAG and PKC pathway

Chronically increased levels of DAG occur in

hyperglycemia as a result of an increased glycolytic intermediary,

dihydroxyacetone phosphate. This intermediate is converted into

glycerol-3-phosphate, which then enhances the production of DAG by

de novo synthesis. The PKC family consists of 11 isoforms,

of which nine are activated by DAG. The activation of the DAG-PKC

pathway increases ROS production via NADPH oxidase, reinforcing OS,

while simultaneously disrupting mitochondrial electron transport,

uncoupling endothelial nitric oxide synthetase and influencing

transcription factors, such as NF-κB, which promotes

pro-inflammatory signaling (38).

Animal studies support the role of PKC in DNP, as

inhibition using LY333531 has been shown to improve sciatic nerve

blood flow, conduction and hyperalgesia (39). PKC activation contributes to

neuropathy via two mechanisms: Reduced activity limits blood flow

and alters conduction, while excessive activity disrupts neuronal

function by affecting neurochemical signaling. Several PKC

inhibitors, similar to aldose reductase inhibitors, also

demonstrate antioxidant properties antioxidant (40).

PARP overactivation

PARP is a nuclear enzyme that facilitates the

attachment of ADP-ribose units to DNA, histones and other DNA

repair enzymes. This process has an impact on cellular functions

(41). Recent evidence indicates

that the overactivation of PARP and the occurrence of OS are two

interconnected pathways. PARP activity is minimal under normal

physiological circumstances. Nevertheless, in the presence of OS,

DNA single-strand breaks become abundant and result in excessive

activation of PARP. As regards DNP, research has demonstrated that

the overactivation of PARP may contribute to the development of

DNP, whereas preventing its function may impede the progression of

this condition (42). PARP is

found in both endothelial cells and Schwann cells inside the

peripheral nerve. The activation of PARP is evident in DM and plays

a role in diabetic endothelial dysfunction, which is a key

contributor to DNP. Activation of PARP induces marked metabolic

alterations and influences the expression of genes. Furthermore,

PARP is necessary for the translocation of apoptosis-provoking

factors from the mitochondria to the nucleus. This process plays a

crucial role in PARP-mediated programmed cell death, which has

recently been linked to the development of DNP (43).

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor 2 (Nrf2) in DNP

Nrf2 is a major leucine zipper protein that mainly

acts as a defense mechanism against cellular OS. It functions as a

transcription factor to regulate the development of cytoprotective

enzymes. Typically, Nrf2 is not active within cells; however, it

becomes activated when there is stress or an increase in the

generation of free radicals (44).

Upon activation, Nrf2 translocates to the cell nucleus and

selectively interacts with the DNA at the antioxidant response

element, decreasing free radicals and OS. Similarly, in the

presence of DM, elevated blood sugar levels lead to the activation

of several neuroinflammatory pathways and the generation of free

radicals. During the first phases of hyperglycemia, Nrf2 signaling

plays a crucial role in controlling the activation of several

cytoprotective genes. However, in cases of prolonged hyperglycemia,

the levels of Nrf2 decline, leading to the development of DNP via

linked neuroinflammatory pathways (3).

5. Impact of antidiabetics on DNP and

oxidative stress

Generally, antidiabetics cannot interfere directly

with the polyol pathway or HBP, which are the main pathways of the

generation of free radicals in DNP (45). Nevertheless, antidiabetic

medications can decrease the production of AGEs and disrupt the

activation of the PKC pathway. In addition, antidiabetics tend to

suppress the inflammatory condition that often induces OS (46-48).

Some antidiabetics exert antioxidant effects either by improving

the endogenous antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD and catalase, or by

reducing the production of ROS. The antioxidant effects of

antidiabetics are accompanied by a reduction in the occurrence of

diabetic complications, including DNP. Thus, in the case of DNP or

high-risk conditions, some antidiabetics may be recommended over

others (Table I) (49).

| Table IEffects of antidiabetics on diabetic

neuropathy along with antioxidant effects. |

Table I

Effects of antidiabetics on diabetic

neuropathy along with antioxidant effects.

| Drug group | Antioxidant

effect | Effect on diabetic

neuropathy | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Metformin | Present | Inconclusive

effects: Several studies have proven positive benefits; on the

other hand, it may be an iatrogenic cause of DNP exacerbation | (55-58,60) |

| Sulfonylurea | Present | Beneficial effects

(gliclazide) | (66) |

|

Thiazolidinediones | Present | Beneficial

effects | (7,71) |

| SGLT-2

inhibitors | Present | Beneficial

effects | (75) |

| DDP-IV

inhibitors | Present | Beneficial

effects | (91-93) |

| GLP-1 receptor

agonists | Present | Inconclusive

effects: Some studies have proven positive effects, while others

have failed to demonstrate improvements in the clinical

presentations of DNP | (80,81,83-85) |

| Alpha-glucosidase

inhibitors | No effect | No effects | (65) |

| Meglitinides | No effect | No effects | (65) |

Metformin

Metformin, a biguanide derivative, is primarily used

for controlling type 2 DM. Adenosine monophosphate-activated

protein kinase (AMPK) is a key prospective target of metformin

since it serves as a cellular energy sensor that becomes activated

in response to metabolic stress, leading to improved glucose uptake

(50). Metformin can significantly

reduce the OS associated with diabetic patients. Previous studies

have demonstrated that metformin has the ability to inhibit

mitochondrial complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase), which

contributes to the antioxidant effect of metformin (51-53).

The cellular production of ROS may be greatly

influenced by mitochondrial complex I. There is much documentation

indicating that a blockage of this complex results in a decrease in

the generation of reactive species. This is caused by a reduction

in the transportation of electrons from NADH plus hydrogen. In

addition, metformin has been demonstrated to scavenge oxygenated

free radicals produced in vitro directly and to inhibit the

opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in both

intact and permeabilized human epithelial carcinoma cells (KB

cells), as well as in permeabilized human microvascular endothelial

cells (HMEC-1 cells) (51,54).

The use of metformin for the treatment of the

manifestations of DNP in both animals and humans has yielded

inconclusive results to date. Several studies have proven the

positive benefits of metformin on DNP (55-58).

Metformin has been shown to reduce the accumulation of AGEs in the

sciatic nerves of rats with streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes

by activating AMPK, leading to improved nerve conduction velocity,

and the attenuation of heat and mechanical hyperalgesia (59). It has also been shown to decrease

serum malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and enhance SOD activity,

highlighting its role in counteracting diabetes-induced OS

(59).

Conversely, other studies suggest that metformin may

worsen neuropathic outcomes, with reports of it functioning as an

iatrogenic factor contributing to more severe neuropathy in type 2

DM (60). This negative effect has

been partly attributed to the association of long-term metformin

use with vitamin B12 deficiency, a known risk factor for DNP. These

contrasting findings underscore the complexity of the effects of

metformin on DNP, indicating a dual role where protective

mechanisms against OS may be counterbalanced by adverse effects

under certain conditions (61).

Sulfonylureas

Sulfonylureas promote insulin secretion by their

interaction with the ATP-sensitive potassium channel located on the

β-cell of the pancreas. Sulfonylureas decrease the level of AGEs

indirectly by controlling blood glucose levels (62). The administration of glimepiride

has been shown to cause a decrease in the levels of peroxides and

MDA, and an increase in the activity of SOD and glutathione

peroxidase in rats following the administration of STZ; this

suggests that glimepiride may effectively inhibit the development

of OS in DM (63). Gliclazide also

exerts a prominent antioxidant effect mainly due to the free

radical scavenging effect. The main mechanism for this effect is

not yet clearly understood; however, the characteristic of an

azabicyclo-octyl ring grafted on a hydrazide group, a structure

unique to gliclazide, may provide the compound with free radical

scavenging properties (64).

Glibenclamide, glipizide, tolazamide and other sulfonylureas do not

exert antioxidant effects. Similar to sulfonylureas, meglitinides

such as repaglinide and nateglinide form a bond with the KATP

channel on the pancreatic beta cells, but at a different binding

location. However, it has not been shown that these medications

have any antioxidant properties (65).

In the aspect of DNP control, gliclazide is a novel

sulfonylurea that inhibits the development of DNP. Regardless of

blood glucose levels in mice with STZ-induced diabetes, gliclazide

considerably reduces peripheral nerve morphological alterations and

improves the slowing of motor nerve conduction velocity. The

morphological alterations observed in diabetic rats compared to

non-diabetic rats include an increase in nerve fiber density and a

reduction in fascicular area, axon/myelin ratio and nerve fiber

area (66). Animal research has

demonstrated that potassium-ATP channel blockage by sulfonylurea

may enhance glutamate-induced superoxide generation and

neurotoxicity by selectively intensifying mitochondrial inhibitors;

however, no such data have been reported for humans, at least to

the best of our knowledge (67).

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs)

TZDs exert their insulin-sensitizing effects through

the activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

(PPAR-γ) nuclear receptor, hence reducing insulin resistance. TZDs

possess exert antioxidant effects. The potential mechanism may be

attributed to the triggering of the transcription of several genes,

including NADPH, SOD and catalase, via the activation of PPAR-γ

receptors, resulting in the improvement of mitochondrial health

(68). Some TZDs, such as

troglitazone, provide direct antioxidant effects via a side chain

that resembles α-tocopherol, in addition to their ability to

indirectly upregulate antioxidant genes. Due to their ability to

decrease NO production via the trans-repression of inducible nitric

oxide synthetase, all TZDs exert intracellular antioxidant effects.

Pioglitazone is beneficial in reducing OS via correction of the PKC

pathway and pro-inflammatory process (69).

It has been shown that the administration of

pioglitazone improves biochemical markers via reduced MDA levels

and improved GSH and SOD activities (70). Pioglitazone has also been shown to

be more effective than metformin in reducing OS, as seen by a

decrease in MDA levels. However, only metformin exerts an

antioxidant effect through an increase in SOD levels. The distinct

mechanisms of action of the two medications on OS support the

concurrent prescription of both treatments to enhance the result in

ameliorating insulin resistance and diabetes complications

(49). TZDs are associated with

increased total serum soluble RAGE levels that may lead to a

decrease in the harmful effects of AGEs. Furthermore, TZDs reduce

the tissue expression of RAGE, resulting in decreased

proinflammatory effects of AGEs (62).

Several studies have been conducted to demonstrate

the efficacy of TZD in slowing or preventing the progression of

DNP. In STZ-treated rats, troglitazone protected against nerve

conduction velocity slowing and maintained normal myelinated fiber

architecture and number (71).

Pioglitazone has the triple advantage of lowering central

sensitization, hyperglycemia and hyperalgesia; hence, TZDs are a

desirable pharmacotherapy for those with neuropathic pain related

to type 2 DM (7). Furthermore,

pioglitazone has neuroprotective properties by enhancing nerve

conduction velocity and diminishing macrophage infiltration in the

sciatic nerve (72). Rosiglitazone

reduces the OS in the sciatic nerve, thus reducing the progression

of DNP (73).

Sodium-glucose co-transporter (SGLT-2)

inhibitors

SGLT-2 inhibitors block SGLT2, which are responsible

for glucose reabsorption in renal proximal convoluted tubules,

leading to glycosuria and a reduction in blood glucose level.

Recently, SGLT-2 inhibitors have been identified as potent

antioxidant agents that can prevent oxidative damage to tissues by

lowering glucose levels, generating fewer free radicals, or by

potentiating the antioxidant system (Table II). The observed therapeutic

advantages of SGLT-2 inhibitors in diabetic complications may be

attributed to the reduction of OS (74).

| Table IIMechanisms of SGLT-2 inhibitors in

reducing oxidative stress (74). |

Table II

Mechanisms of SGLT-2 inhibitors in

reducing oxidative stress (74).

| Effect | Mechanisms |

|---|

| Reduction of

free-radical generation | Decreasing the

level of prooxidant enzymes, such as |

| | Nox and eNOS |

| | Reduction of levels

of AGEs |

| | Lowering the level

of proinflammatory cytokines |

| | Improvement of

insulin sensitivity |

| | Normalization of

hemodynamic condition |

| | Enhancement of

mitochondrial function |

| Antioxidant

effect | Directly via

increasing the endogenous antioxidant system and scavenging the

free radicals or indirectly by inducing normoglycemia. |

A previous meta-analysis of 89 articles in the field

of DNP demonstrated that SGLT-2 inhibitors have the potential to

preserve the nerves by significantly enhancing the speed at which

sensory and motor nerves conduct signals (75). This improvement in nerve function

leads to improved clinical manifestations for patients with DNP,

with a reduction in the activity of the sympathetic nervous system

(75). A follow-up study

demonstrated that the use of SGLT-2 inhibitors for >3 years led

to significant improvements in certain measures of neuropathy

(76).

Combining dapagliflozin and mecobalamin may

considerably reduce clinical symptoms in patients with DNP. This

combination may lower blood glucose, control MDA, SOD and

cyclooxygenase 2 levels, and prevent nerve cell damage.

Additionally, it promotes sensory and motor nerve transmission. The

approach of using dapagliflozin and mecobalamin is safe and

warrants clinical promotion (77).

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1)

agonists

GLP-1 receptor agonists, as a class of antidiabetic

medications, have been observed to enhance the secretion of insulin

in response to glucose stimulation, inhibit the release of

glucagon, and delay the process of stomach emptying. GLP-1 can

reverse the oxidative action, as the administration of GLP-1 or its

receptor agonist has been found to have a beneficial effect on OS

markers, such as SOD, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione amount,

glutathione reductase, catalase, lipid peroxidation and

non-enzymatic glycosylated proteins, stimulated by different stress

factors (78). The mechanism by

which GLP-1 reduces OS in DM involves the activation of cyclic

adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), PI3K and PKC pathways via

receptors, as well as the activation of Nrf-2, increasing

antioxidant capacity. These findings indicate that activating Nrf2

by GLP-1 and its subsequent antioxidative effects may have

potential benefits in preventing and treating DM, as well as

reducing the likelihood of complications. Also, GLP-1 receptor

agonists were suggested to suppress OS generation induced by

AGEs-RAGE and reduce tissue expression of RAGE via activation of

cAMP pathways (79).

However, the effect of GLP-1s receptor agonists in

DNP remain uncertain. Some clinical studies support the role of

GLP-1 receptor agonists in improving DNP through a number of

mechanisms including the antioxidant effect, the anti-inflammatory

signaling through microglia/astrocyte modulation, improvement in

peripheral nerve blood flow and endothelial function, and metabolic

improvement (80,81). The antioxidant effect is one of the

most effective mechanisms. GLP-1 receptor agonists activate SOD;

however, they do not cause alterations in the distribution pattern

of neuronal markers. Exenatide protects cells against apoptosis

caused by OS and promotes neurite. These findings suggest that

GLP-1 receptor agonists function as neuroprotective agents,

considering their direct effects on neurons (82). Another study documented that the

use of liraglutide alleviated DNP through antioxidant and

anti-inflammatory effects, as well as via the remodeling of the

extracellular matrix (81).

On the other hand, other research has demonstrated

that GLP-1 receptor agonists have no significant effect in

improving DNP (8). Despite the

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of liraglutide, no

clinical improvement in autonomic neuropathy or polyneuropathy has

been observed (83). In addition,

exenatide has failed to provide a significant effect on DNP

(84,85).

Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DDP-IV)

inhibitors

DPP-IV inhibitors prevent the breakdown of

endogenous GLP-1, consequently enhancing the incretin action.

DPP-IV, a cell surface enzyme found in endothelial cells and some

lymphocytes, is responsible for the degradation of various

peptides. DPP-IV inhibitors have been observed to stimulate insulin

secretion without causing hypoglycemia or weight gain (86). Clinical studies have demonstrated

that DPP-IV inhibitors exert antioxidant effects by reducing ROS

generation and promoting the activity of antioxidant enzymes,

including increased nitric oxide, SOD, catalase and reduced

glutathione (87,88).

Furthermore, it has been discovered that the

production of ROS caused by the AGE-RAGE interaction leads to the

release of DPP-4. DPP-4 inhibitors prevent this release (89). Additionally, another study

demonstrated that the use of vildagliptin, a DPP-4 inhibitor, was

associated with decreased AGEs to a certain extent (90).

As regards DNP, sitagliptin plays protective roles

on neurons via activating GLP-1 receptor, resulting in an

anti-apoptotic effect, improving microtubule stabilization and axon

regeneration, ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction, and promoting

locomotor functional recovery. The mechanism of action of

sitagliptin in DNP is related to AMPK/peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) signaling

pathway. The activation of the AMPK/PGC-1α signaling pathway

results in the development of neurites and the regeneration of

axons (9). It is well-established

that when teneligliptin is orally administered, it produces

analgesic properties in humans specifically against thermal pain.

It has been demonstrated that teneligliptin exerts mild

antinociceptive effects in response to acute pain; however, it

exerts, significant analgesic effects against DNP. Furthermore,

teneligliptin can improve the synthesis of glutathione antioxidants

inside the cellular environment (91,92).

Vildagliptin improves glucose intolerance and increases serum

insulin and GLP-1 levels, accompanied by the amelioration of

delayed nerve conduction velocity and neuronal atrophy (93).

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors attenuate the process

of starch digestion in the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in a

slow release of glucose into the circulation. The currently used

alpha-glucosidase inhibitors consist of acarbose and miglitol. Thus

far, there have been no documented antioxidant properties observed

for these medications (65).

However, a previous study demonstrated that miglitol improved the

activity of catalase, SOD, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione

reductase and thioredoxin reductase (94).

6. Clinical significance, prescribing

recommendations and future directions

Clinical significance

Glycemic control is the primary goal of DNP

treatment. The pathogenesis of the complication is regarded as the

primary focus of interest while developing pharmaceutical DNP

targets. Although there is no curative treatment for DNP, several

medications can alleviate the symptoms. When managing diabetic

neuropathy, it is important to select antidiabetics with

antioxidant properties that attenuate the progression of the

disease, in addition to controlling the blood sugar levels

(75-77,95).

Prescribing recommendations

The use of metformin should be accompanied by

routine vitamin B12 monitoring and supplementation to maximize its

benefit in DNP, while minimizing deficiency-related risks. The use

of pioglitazone may be considered in patients with neuropathic pain

due to its neuroprotective potential, although caution is advised

due to its side-effect profile. Combination therapy with metformin,

pioglitazone and vitamin B12 supplementation may provide the most

prominent protective effect against DNP (7,49,72,96).

Concerning sulfonylureas, gliclazide is a novel sulfonylurea that

inhibits the development of DNP (65). However, the use of sulfonylureas or

insulin in combination with metformin and pioglitazone may worsen

DNP (75,76,97).

SGLT-2 inhibitors, particularly dapagliflozin, may be incorporated

into diabetes therapy where neuropathy is a concern, with potential

added benefit when combined with cobalamin (77).

The effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists in DNP is

uncertain, and the use of such medications in DNP requires further

investigations (8,80,81,83-85).

Sitagliptin, as a DPP-IV inhibitor, on the other hand, plays a

protective role in neurons by improving the actions of GLP-1. The

administration of sitagliptin in conjunction with metformin leads

to enhanced grip strength and increased pain sensitivity, while

also demonstrating neuroprotective effects (95).

Future directions

Future studies for the management of DNP are

required to focus on identifying medications that can directly

interfere with the main pathways of ROS generation, including the

polyol pathway and HBP. Furthermore, additional studies may be

required to provide sufficient insight into the role of

antidiabetic combinations in preventing DNP, and to determine which

combinations are the most effective.

7. Conclusion

Hyperglycemia and a complex metabolic imbalance,

primarily OS, are current hypotheses for the progression of DNP. A

number of antidiabetics exert antioxidant effects that can reduce

OS in patients with DM. The antioxidant effects of antidiabetics

are accompanied by a reduction in the occurrence of diabetic

complications, including DNP. Some antidiabetics may be beneficial

in preventing the progression of DNP, while others have no effect

or could trigger or worsen the existing DNP. Thus, in the case of

DNP or high-risk conditions, some antidiabetics may be recommended

over others.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their deepest

appreciation to the University of Mosul and the College of Pharmacy

(University of Mosul), Mosul, Iraq, for their critical advice, and

invaluable academic guidance.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

KAH and MKZ were involved in the writing, reviewing

and editing of the manuscript, as well as in the writing and

preparation of the original draft of the manuscript, and the

conceptualization of the study. FAA and MNA supervised the study,

and were also involved in project administration, in the literature

search and in the conceptualization of the study. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ahmed GM, Abed MN and Alassaf FA: Impact

of calcium channel blockers and angiotensin receptor blockers on

hematological parameters in type 2 diabetic patients. Naunyn

Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 397:1817–1828. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Liu X, Xu Y, An M and Zeng Q: The risk

factors for diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A meta-analysis. PLoS

One. 14(e0212574)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

González P, Lozano P, Ros G and Solano F:

Hyperglycemia and oxidative stress: An integral, updated and

critical overview of their metabolic interconnections. Int J Mol

Sci. 24(9352)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Al-dabbagh BM, Abed MN, Mahmood NM,

Alassaf FA, Jasim MH, Alfahad MA and Thanoon IAJ:

Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and hepatoprotective potential of

milk thistle in albino rats. Lat Am J Pharm. 41:1832–1841.

2022.

|

|

5

|

Hadid KA, Alassaf FA and Abed MN:

Mechanisms and linkage of insulin signaling, resistance, and

inflammation. Iraqi J Pharm. 21:1–8. 2024.

|

|

6

|

Lin Q, Li K, Chen Y, Xie J, Wu C, Cui C

and Deng B: Oxidative stress in diabetic peripheral neuropathy:

Pathway and mechanism-based treatment. Mol Neurobiol. 60:4574–4594.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Griggs RB, Donahue RR, Adkins BG, Anderson

KL, Thibault O and Taylor BK: Pioglitazone inhibits the development

of hyperalgesia and sensitization of spinal nociresponsive neurons

in type 2 diabetes. J Pain. 17:359–373. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

García-Casares N, González-González G, de

la Cruz-Cosme C, Garzón-Maldonado FJ, de Rojas-Leal C, Ariza MJ,

Narváez M, Barbancho MÁ, García-Arnés JA and Tinahones FJ: Effects

of GLP-1 receptor agonists on neurological complications of

diabetes. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 24:655–672. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Han W, Li Y, Cheng J, Zhang J, Chen D,

Fang M, Xiang G, Wu Y, Zhang H, Xu K, et al: Sitagliptin improves

functional recovery via GLP-1R-induced anti-apoptosis and

facilitation of axonal regeneration after spinal cord injury. J

Cell Mol Med. 24:8687–8702. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Maeda-Gutiérrez V, Galván-Tejada CE, Cruz

M, Valladares-Salgado A, Galván-Tejada JI, Gamboa-Rosales H,

García-Hernández A, Luna-García H, Gonzalez-Curiel I and

Martínez-Acuña M: Distal symmetric polyneuropathy identification in

type 2 diabetes subjects: A random forest approach. Healthcare

(Basel). 9(138)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Oh J: Clinical spectrum and diagnosis of

diabetic neuropathies. Korean J Intern Med. 35:1059–1069.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Sharma JK, Rohatgi A and Sharma D:

Diabetic autonomic neuropathy: A clinical update. J R Coll

Physicians Edinb. 50:269–273. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Bell DSH: Diabetic mononeuropathies and

diabetic amyotrophy. Diabetes Ther. 13:1715–1722. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ahmed GM, Abed MN and Alassaf FA: The

diabetic-anemia nexus: Implications for clinical practice. Mil Med

Sci Lett. 92:1–11. 2023.

|

|

15

|

Bhatti JS, Sehrawat A, Mishra J, Sidhu IS,

Navik U, Khullar N, Kumar S, Bhatti GK and Reddy PH: Oxidative

stress in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes and related

complications: Current therapeutics strategies and future

perspectives. Free Radic Biol Med. 184:114–134. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Mosquera-Sulbarán JA and Hernández-Fonseca

JP: Advanced glycation end products in diabetes. In: Patel VB,

Preedy VR (eds) Biomarkers in Diabetes. Biomarkers in Disease:

Methods, Discoveries and Applications. Springer, Cham, pp171-194,

2023.

|

|

17

|

Abed MN, Alassaf FA, Jasim MHM, Alfahad M

and Qazzaz ME: Comparison of antioxidant effects of the proton

pump-inhibiting drugs omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole,

pantoprazole, and rabeprazole. Pharmacology. 105:645–651.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Alfahad M, Qazzaz ME, Abed MN, Alassaf FA

and Jasim MHM: Comparison of anti-oxidant activity of different

brands of esomeprazole available in Iraqi pharmacies. Syst Rev

Pharm. 11:330–33. 2020.

|

|

19

|

Dilworth L, Stennett D, Facey A, Omoruyi

F, Mohansingh S and Omoruyi FO: Diabetes and the associated

complications: The role of antioxidants in diabetes therapy and

care. Biomed Pharmacother. 181(117641)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ganjifrockwala FA, Joseph JT and George G:

Decreased total antioxidant levels and increased oxidative stress

in South African type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. J Endocrinol

Metab Diabetes South Africa. 22:21–25. 2017.

|

|

21

|

Pang L, Lian X, Liu H, Zhang Y, Li Q, Cai

Y, Ma H and Yu X: Understanding diabetic neuropathy: Focus on

oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2020(9524635)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Zampieri M, Bacalini MG, Barchetta I,

Scalea S, Cimini FA, Bertoccini L, Tagliatesta S, De Matteis G,

Zardo G, Cavallo MG and Reale A: Increased PARylation impacts the

DNA methylation process in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin

Epigenetics. 13(114)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Chung SSM, Ho ECM, Lam KSL and Chung SK:

Contribution of polyol pathway to diabetes-induced oxidative

stress. J Am Soc Nephrol. 14 (8 Suppl 3):S233–S236. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Lv Y, Yao X, Li X, Ouyang Y, Fan C and

Qian Y: Cell metabolism pathways involved in the pathophysiological

changes of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Neural Regen Res.

19:598–605. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Gugliucci A: Formation of

fructose-mediated advanced glycation end products and their roles

in metabolic and inflammatory diseases. Adv Nutr. 8:54–62.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Rendell MS: The time to develop treatments

for diabetic neuropathy. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 30:119–130.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Niimi N, Yako H, Takaku S, Chung SK and

Sango K: Aldose reductase and the polyol pathway in schwann cells:

Old and new problems. Int J Mol Sci. 22(1031)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Brownlee M: Biochemistry and molecular

cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 414:813–820.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Nagel AK and Ball LE: Intracellular

protein O-GlcNAc modification integrates nutrient status with

transcriptional and metabolic regulation. Adv Cancer Res.

126:137–166. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Paneque A, Fortus H, Zheng J, Werlen G and

Jacinto E: The hexosamine biosynthesis pathway: Regulation and

function. Genes (Basel). 14(933)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Nelson ZM, Leonard GD and Fehl C: Tools

for investigating O-GlcNAc in signaling and other fundamental

biological pathways. J Biol Chem. 300(105615)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Alasaf FA, Jasim MHM, Alfahad M, Qazzaz

ME, Abed MN and Thanoo IAJ: Effects of bee propolis on FBG, HbA1c,

and insulin resistance in healthy volunteers. Turkish J Pharm Sci.

18:405–409. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Buse MG, Robinson KA, Gettys TW, McMahon

EG and Gulve EA: Increased activity of the hexosamine synthesis

pathway in muscles of insulin-resistant ob/ob mice. Am J Physiol.

272:E1080–E1088. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Papachristou S, Pafili K and Papanas N:

Skin AGEs and diabetic neuropathy. BMC Endocr Disord.

21(28)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Sugimoto K, Yasujima M and Yagihashi S:

Role of advanced glycation end products in diabetic neuropathy.

Curr Pharm Des. 14:953–961. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Jasim MHM, Alfahad M, Al-Dabbagh BM,

Alassaf FA, Abed MN and Mustafa YF: Synthesis, characterization,

ADME study and in-vitro anti-inflammatory activity of aspirin amino

acid conjugates. Pharm Chem J. 57:243–249. 2023.

|

|

37

|

Kim J and Lee J: Role of obesity-induced

inflammation in the development of insulin resistance and type 2

diabetes: History of the research and remaining questions. Ann

Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 26:1–13. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Kolczynska K, Loza-Valdes A, Hawro I and

Sumara G: Diacylglycerol-evoked activation of PKC and PKD isoforms

in regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism: A review. Lipids

Health Dis. 19(113)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Kim H, Sasaki T, Maeda K, Koya D,

Kashiwagi A and Yasuda H: Protein kinase Cbeta selective inhibitor

LY333531 attenuates diabetic hyperalgesia through ameliorating cGMP

level of dorsal root ganglion neurons. Diabetes. 52:2102–2109.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Oyenihi AB, Ayeleso AO, Mukwevho E and

Masola B: Antioxidant strategies in the management of diabetic

neuropathy. Biomed Res Int. 2015(515042)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Arruri VK, Gundu C, Khan I, Khatri DK and

Singh SB: PARP overactivation in neurological disorders. Mol Biol

Rep. 48:2833–2841. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Brady PN, Goel A and Johnson MA:

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases in host-pathogen interactions,

inflammation, and immunity. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 83:e00038–18.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Yuan P, Song F, Zhu P, Fan K, Liao Q,

Huang L and Liu Z: Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1-mediated

defective mitophagy contributes to painful diabetic neuropathy in

the db/db model. J Neurochem. 162:276–289. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Kumar A and Mittal R: Nrf2: A potential

therapeutic target for diabetic neuropathy. Inflammopharmacology.

25:393–402. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Gawli K and Bojja KS: Molecules and

targets of antidiabetic interest. Phytomedicine Plus.

4(100506)2024.

|

|

46

|

Alnaser RI, Alassaf FA and Abed MN:

Adulteration of hypoglycemic products: The silent threat. Rom J Med

Pract. 18:157–160. 2023.

|

|

47

|

Abdollahi E, Keyhanfar F, Delbandi AA,

Falak R, Hajimiresmaiel SJ and Shafiei M: Dapagliflozin exerts

anti-inflammatory effects via inhibition of LPS-induced TLR-4

overexpression and NF-κB activation in human endothelial cells and

differentiated macrophages. Eur J Pharmacol.

918(174715)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Mehdi SF, Pusapati S, Anwar MS, Lohana D,

Kumar P, Nandula SA, Nawaz FK, Tracey K, Yang H, LeRoith D, et al:

Glucagon-like peptide-1: A multi-faceted anti-inflammatory agent.

Front Immunol. 14(1148209)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Singh RK, Gupta B, Tripathi K and Singh

SK: Anti oxidant potential of metformin and pioglitazone in type 2

diabetes mellitus: Beyond their anti glycemic effect. Diabetes

Metab Syndr. 10:102–104. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Rena G, Hardie DG and Pearson ER: The

mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia. 60:1577–1585.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Fontaine E: Metformin-induced

mitochondrial complex I Inhibition: Facts, uncertainties, and

consequences. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 9(753)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Martín-Rodríguez S, de Pablos-Velasco P

and Calbet JAL: Mitochondrial complex I inhibition by metformin:

Drug-exercise interactions. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 31:269–271.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Cameron AR, Logie L, Patel K, Erhardt S,

Bacon S, Middleton P, Harthill J, Forteath C, Coats JT, Kerr C, et

al: Metformin selectively targets redox control of complex I energy

transduction. Redox Biol. 14:187–197. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Carvalho C, Correia S, Santos MS, Seiça R,

Oliveira CR and Moreira PI: Metformin promotes isolated rat liver

mitochondria impairment. Mol Cell Biochem. 308:75–83.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Wei J, Wei Y, Huang M, Wang P and Jia S:

Is metformin a possible treatment for diabetic neuropathy? J

Diabetes. 14:658–669. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Lós DB, Oliveira WH, Duarte-Silva E,

Sougey WWD, Freitas EDSR, de Oliveira AGV, Braga CF, França MER,

Araújo SMDR, Rodrigues GB, et al: Preventive role of metformin on

peripheral neuropathy induced by diabetes. Int Immunopharmacol.

74(105672)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Alcántara Montero A, Goicoechea García C,

Pacheco de Vasconcelos SR and Alvarado PMH: Potential benefits of

metformin in the treatment of chronic pain. Neurol Perspect.

2:107–109. 2022.

|

|

58

|

Kim SH, Park TS and Jin HY: Metformin

preserves peripheral nerve damage with comparable effects to alpha

lipoic acid in streptozotocin/high-fat diet induced diabetic rats.

Diabetes Metab J. 44:842–853. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Kakhki FSH, Asghari A, Bardaghi Z,

Anaeigoudari A, Beheshti F, Salmani H and Hosseini M: The

antidiabetic drug metformin attenuated depressive and anxiety-like

behaviors and oxidative stress in the brain in a rodent model of

inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide in male rats. Endocr

Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 24:1525–1537. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Yang R, Yu H, Wu J, Chen H, Wang M, Wang

S, Qin X, Wu T, Wu Y and Hu Y: Metformin treatment and risk of

diabetic peripheral neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes

mellitus in Beijing, China. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14(1082720)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Alvarez M, Sierra OR, Saavedra G and

Moreno S: Vitamin B12 deficiency and diabetic neuropathy in

patients taking metformin: A cross-sectional study. Endocr Connect.

8:1324–1329. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Ragazzi E, Burlina S, Cosma C, Chilelli

NC, Lapolla A and Sartore G: Anti-diabetic combination therapy with

pioglitazone or glimepiride added to metformin on the AGE-RAGE

axis: A randomized prospective study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14(1163554)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Krauss H, Koźlik J, Grzymisławski M,

Sosnowski P, Mikrut K, Piatek J and Paluszak J: The influence of

glimepiride on the oxidative state of rats with

streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemia. Med Sci Monit. 9:BR389–BR393.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

O'Brien RC, Luo M, Balazs N and Mercuri J:

In vitro and in vivo antioxidant properties of gliclazide. J

Diabetes Complications. 14:201–206. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Choi SW and Ho CK: Antioxidant properties

of drugs used in type 2 diabetes management: Could they contribute

to, confound or conceal effects of antioxidant therapy? Redox Rep.

23:1–24. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Qiang X, Satoh J, Sagara M, Fukuzawa M,

Masuda T, Miyaguchi S, Takahashi K and Toyota T: Gliclazide

inhibits diabetic neuropathy irrespective of blood glucose levels

in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Metabolism. 47:977–981.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Kou J, Klorig DC and Bloomquist JR:

Potentiating effect of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel blocker

glibenclamide on complex I inhibitor neurotoxicity in vitro and in

vivo. Neurotoxicology. 27:826–834. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Hwang J, Kleinhenz DJ, Rupnow HL, Campbell

AG, Thulé PM, Sutliff RL and Hart CM: The PPARgamma ligand,

rosiglitazone, reduces vascular oxidative stress and NADPH oxidase

expression in diabetic mice. Vascul Pharmacol. 46:456–462.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Alhowail A, Alsikhan R, Alsaud M,

Aldubayan M and Rabbani SI: Protective effects of pioglitazone on

cognitive impairment and the underlying mechanisms: A review of

literature. Drug Des Devel Ther. 16:2919–2931. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Al-Muzafar HM, Alshehri FS and Amin KA:

The role of pioglitazone in antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and

insulin sensitivity in a high fat-carbohydrate diet-induced rat

model of insulin resistance. Braz J Med Biol Res.

54(e10782)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Qiang X, Satoh J, Sagara M, Fukuzawa M,

Masuda T, Sakata Y, Muto G, Muto Y, Takahashi K and Toyota T:

Inhibitory effect of troglitazone on diabetic neuropathy in

streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetologia. 41:1321–1326.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Yamagishi S, Ogasawara S, Mizukami H,

Yajima N, Wada R, Sugawara A and Yagihashi S: Correction of protein

kinase C activity and macrophage migration in peripheral nerve by

pioglitazone, proliferator activated-gamma-ligand, in

insulin-deficient diabetic rats. J Neurochem. 104:491–499.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Wiggin TD, Kretzler M, Pennathur S,

Sullivan KA, Brosius FC and Feldman EL: Rosiglitazone treatment

reduces diabetic neuropathy in streptozotocin-treated DBA/2J mice.

Endocrinology. 149:4928–4937. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Nabrdalik-Leśniak D, Nabrdalik K,

Sedlaczek K, Główczyński P, Kwiendacz H, Sawczyn T, Hajzler W,

Drożdż K, Hendel M, Irlik K, et al: Influence of SGLT2 inhibitor

treatment on urine antioxidant status in type 2 diabetic patients:

A pilot study. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021(5593589)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Kandeel M: The outcomes of sodium-glucose

co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2I) on diabetes-associated

neuropathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol.

13(926717)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Ishibashi F, Kosaka A and Tavakoli M:

Sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor protects against diabetic

neuropathy and nephropathy in modestly controlled type 2 diabetes:

Follow-up study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

13(864332)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Wang C, Pan H, Wang W and Xu A: Effect of

dapagliflozin combined with mecobalamin on blood glucose

concentration and serum MDA, SOD, and COX-2 in patients with type 2

diabetes mellitus complicated with peripheral neuropathy. Acta

medica Mediterr. 35:2211–2215. 2019.

|

|

78

|

Bray JJH, Foster-Davies H, Salem A, Hoole

AL, Obaid DR, Halcox JPJ and Stephens JW: Glucagon-like peptide-1

receptor agonists improve biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative

stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised

controlled trials. Diabetes, Obes Metab. 23:1806–1822.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Oh Y and Jun HS: Effects of glucagon-like

peptide-1 on oxidative stress and Nrf2 signaling. Int J Mol Sci.

19(26)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Ma J, Shi M, Zhang X, Liu X, Chen J, Zhang

R, Wang X and Zhang H: GLP-1R agonists ameliorate peripheral nerve

dysfunction and inflammation via p38 MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathways

in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int J Mol Med.

41:2977–2985. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Moustafa PE, Abdelkader NF, El Awdan SA,

El-Shabrawy OA and Zaki HF: Liraglutide ameliorated peripheral

neuropathy in diabetic rats: Involvement of oxidative stress,

inflammation and extracellular matrix remodeling. J Neurochem.

146:173–185. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Mohiuddin MS, Himeno T, Inoue R,

Miura-Yura E, Yamada Y, Nakai-Shimoda H, Asano S, Kato M, Motegi M,

Kondo M, et al: Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist protects

dorsal root ganglion neurons against oxidative insult. J Diabetes

Res. 2019(9426014)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Brock C, Hansen CS, Karmisholt J, Møller

HJ, Juhl A, Farmer AD, Drewes AM, Riahi S, Lervang HH, Jakobsen PE

and Brock B: Liraglutide treatment reduced interleukin-6 in adults

with type 1 diabetes but did not improve established autonomic or

polyneuropathy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 85:2512–2523. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Jaiswal M, Martin CL, Brown MB, Callaghan

B, Albers JW, Feldman EL and Pop-Busui R: Effects of exenatide on

measures of diabetic neuropathy in subjects with type 2 diabetes:

Results from an 18-month proof-of-concept open-label randomized

study. J Diabetes Complications. 29:1287–1294. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Ponirakis G, Abdul-Ghani MA, Jayyousi A,

Almuhannadi H, Petropoulos IN, Khan A, Gad H, Migahid O, Megahed A,

DeFronzo R, et al: Effect of treatment with exenatide and

pioglitazone or basal-bolus insulin on diabetic neuropathy: A

substudy of the Qatar study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care.

8(e001420)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Saini K, Sharma S and Khan Y: DPP-4

inhibitors for treating T2DM-hype or hope? An analysis based on the

current literature. Front Mol Biosci. 10(1130625)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Bolevich S, Milosavljevic I, Draginic N,

Andjic M, Jeremic N, Bolevich S, Litvitskiy PF and Jakovljevic V:

The effect of the chronic administration of dpp4-inhibitors on

systemic oxidative stress in rats with diabetes type 2. Serbian J

Exp Clin Res. 20:199–206. 2019.

|

|

88

|

Choi SW and Ho CK-C: Antioxidant

properties of drugs used in type 2 diabetes management. In:

Diabetes. 2nd Edition. Academic Press, pp139-148, 2020.

|

|

89

|

Nakashima S, Matsui T, Takeuchi M and

Yamagishi SI: Linagliptin blocks renal damage in type 1 diabetic

rats by suppressing advanced glycation end products-receptor axis.

Horm Metab Res. 46:717–721. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Zhang L, Li P, Tang Z, Dou Q and Feng B:

Effects of GLP-1 receptor analogue liraglutide and DPP-4 inhibitor

vildagliptin on the bone metabolism in ApoE-/- mice. Ann

Transl Med. 7(369)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Kuthati Y, Rao VN, Busa P and Wong CS:

Teneligliptin exerts antinociceptive effects in rat model of

partial sciatic nerve transection induced neuropathic pain.

Antioxidants (Basel). 10(1438)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Busa P, Kuthati Y, Huang N and Wong CS:

New advances on pathophysiology of diabetes neuropathy and pain

management: Potential role of melatonin and DPP-4 inhibitors. Front

Pharmacol. 13(864088)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Tsuboi K, Mizukami H, Inaba W, Baba M and

Yagihashi S: The dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor vildagliptin

suppresses development of neuropathy in diabetic rodents: Effects

on peripheral sensory nerve function, structure and molecular

changes. J Neurochem. 136:859–870. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Shrivastava A, Chaturvedi U, Singh SV,

Saxena JK and Bhatia G: Lipid lowering and antioxidant effect of

miglitol in triton treated hyperlipidemic and high fat diet induced

obese rats. Lipids. 48:597–607. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Sharma AK, Sharma A, Kumari R, Kishore K,

Sharma D, Srinivasan BP, Sharma A, Singh SK, Gaur S, Jatav VS, et

al: Sitagliptin, sitagliptin and metformin, or sitagliptin and

amitriptyline attenuate streptozotocin-nicotinamide induced

diabetic neuropathy in rats. J Biomed Res. 26:200–210.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Pecikoza U, Tomić M, Nastić K, Micov A and

Stepanović-Petrović R: Synergism between metformin and

analgesics/vitamin B12 in a model of painful diabetic

neuropathy. Biomed Pharmacother. 153(113441)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Pop-Busui R, Lu J, Lopes N and Jones TLZ:

BARI 2D Investigators. Prevalence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy

and relation to glycemic control therapies at baseline in the BARI

2D cohort. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 14:1–13. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Singh R, Farooq SA, Mannan A, Singh TG,

Najda A, Grażyna Z, Albadrani GM, Sayed AA and Abdel-Daim MM:

Animal models of diabetic microvascular complications: Relevance to

clinical features. Biomed Pharmacother. 145(112305)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Ahmad AA, Barani SSI and Sultan SJ: Role

of the IL-10 gene and its genetic variations in the development of

diabetes mellitus in women. World Acad Sci J. 7:1–7. 2025.

|

|

100

|

Singh M, Kapoor A and Bhatnagar A:

Physiological and pathological roles of aldose reductase.

Metabolites. 11(655)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Mohammad RA, Saeed MK and Ali WK:

Evaluation of sorbitol dehydrogenase and some biochemical

parameters in patients with hepatitis. Kirkuk Univ J Sci Stud.

14:21–32. 2019.

|

|

102

|

Chiaradonna F, Ricciardiello F and

Palorini R: The nutrient-sensing hexosamine biosynthetic pathway as

the hub of cancer metabolic rewiring. Cells. 7(53)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Mustafa YF: Harmful free radicals in

aging: A narrative review of their detrimental effects on health.

Indian J Clin Biochem. 39:154–167. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|