Introduction

Metabolic syndrome is one of the most important

illnesses of the recent century (1).

It is a set of symptoms, namely hypertension, dyslipidemia,

dysglycemia and abdominal obesity, which occur secondary to insulin

resistance (2). Its prevalence is

20.2% in the United States (3), 30%

in Brazil (4) and 10.7% in South

Korea (5). A meta-analysis on a

sample of 74,440 Iranians stated that its prevalence in Iran is

34.7% (6).

Metabolic syndrome increases the risk of chronic

illnesses, particularly cardiovascular disease (7). People with metabolic syndrome are at

twice the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, three times

the risk of developing ischemic stroke (8), and five times the risk of developing

diabetes mellitus (9). Furthermore,

those with metabolic syndrome are prone to developing

osteoarthritis, certain types of cancer, with increased disability

and mortality risks (10). Metabolic

syndrome imposes heavy costs on healthcare systems (1).

The pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome remains

unclear. It involves a variety of contributing factors, including

lifestyle, environmental and genetic factors (11), stress (12), sex (13), number of parities (14), and shift work (15). Certain studies have reported a higher

risk of metabolic syndrome among women (14) and shift workers (15). Shift work is defined as working night

shifts between 6:00 p.m. to 07:00 a.m. It can negatively affect

circadian rhythm, and thereby, cause alterations in the secretion

of hormones, such as growth hormone, melatonin, cortisol, leptin

and ghrelin (16,17). Alterations to these hormones may

affect body metabolism, reduce glucose tolerance and increase

insulin resistance (18,19). A study on 2,089 hospital staff in

South Korea concluded that shift work significantly increases the

risk of metabolic syndrome (20).

However, certain studies reported an insignificant association with

metabolic syndrome (21,22), weight gain (23) and serum lipid levels (24).

In Iran, women are primarily employed in service

jobs (25), particularly in hospitals

(26), welfare centers (27) and nursing homes, whereby shift work is

typically encountered (28). Around

two thirds of employed women in Iran are of reproductive age

(25), and thus, experience pregnancy

and childbirth during their employment (29). Besides shift work, parity and the

number of parities can increase the risk of metabolic syndrome

among these women due to parity-associated increased abdominal

circumference (14) and increased

insulin resistance (30). Therefore,

female shift workers with more children appear to be at greater

risk of developing metabolic syndrome. Previous studies in Iran

investigating the association between shift work and metabolic

syndrome have been performed on industrial workers (24) and drivers (7). However, to the best of our knowledge, no

study has yet evaluated the prevalence of metabolic syndrome among

Iranian female shift workers, particularly those who are married

and are of reproductive age. The current study aimed to evaluate

the association between shift work with metabolic syndrome during

reproductive age.

Materials and methods

Patients

The present multi-center cross-sectional

correlational study was performed between September 2017 and May

2018 in three central cities located in Mazandaran, Iran (Amol,

Babol and Ghaemshahr). Participants were female shift and day

workers purposively selected from hospitals, welfare and

rehabilitation centers, nursing homes, and textile and sewing

mills. Participants were recruited if they were between 18 and 45

years old, married and had >2 years of work experience. The

exclusion criteria maintained were voluntary withdrawal from the

study or incompletion of the study, and having cardiovascular

disease, diabetes mellitus, or hypertension (with a blood pressure

of >140/90 mmHg) at the beginning of work.

For sample size calculation, the prevalence of

metabolic syndrome was considered to be at most 25% based on

results from two previous studies (31,32).

Accordingly, with a confidence level of 95% and an estimation error

of 6%, the sample size was estimated to be 200 participants/group.

Yet, considering an attrition rate of 5%, 419 women were

selected.

Assessment of demographical,

occupational and medical characteristics

A questionnaire was used to assess participant

demographical, occupational and reproductive characteristics.

Demographical characteristics included age, educational level,

place of residence and family income. Occupational characteristics

were work schedule (shift work or day work), work experience,

number of working hours/month, organizational position, workload

and occupational stress. Workload was assessed using a question

answered on a five-point Likert scale from ‘light’ to ‘heavy’,

while occupational stress was assessed using a question answered on

a five-point Likert scale from ‘very low’ to ‘very high’.

Reproductive characteristics assessed in the present study were

number of parities and route of delivery.

Assessment of health-associated

behaviors

Participant health-associated behaviors were

assessed through questions regarding cigarette smoking (yes/no),

alcohol consumption (yes/no), sleep quantity and quality, and

physical activity. The questions for sleep quantity and quality

assessment were, ‘How many hours do you sleep a day, on average?’

and ‘Is your current sleep adequate to fulfil your need for sleep?’

(yes/no), respectively. For physical activity assessment,

participants were asked if they walked ≥30 min thrice weekly. ‘Yes’

and ‘No’ responses to this question were respectively interpreted

as physically active and physically inactive.

Anthropometric measures

An analogue weight scale (MW84; EmsiG GmbH Co.,

Hamburg, Germany) and a wall-mounted plastic tape were used to

respectively measure weight and height in upright position without

shoes and with minimum possible clothes. Waist circumference (WC)

was also measured in the midway between the lowest rib edge and the

iliac crest.

Blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) was measured using an analogue

sphygmomanometer (EmsiG GmbH Co.) from the right arm in the sitting

position, and following a 15-min rest.

Biomarkers

Biomarkers assessed in the current study were

triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and fasting blood

sugar (FBS). Accordingly, a 5-mm blood sample was taken from each

participant at 07:00-09:00 a.m. following a night time fasting

period of 12-14 h. Subsequently, biochemical analysis was performed

in a laboratory of a hospital affiliated to Babol University of

Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran. All laboratory analyses were

performed by a laboratory technician, using an identical kit (Pars

Azmoon kit, Pars Azmoon Inc., Tehran, Iran), and one biochemistry

analyzer (Sapphire 800; Audit Diagnostics, Cork, Ireland).

Furthermore, blood sampling and anthropometric and blood pressure

measurements were performed by one person.

Diagnostic criteria for metabolic

syndrome

According to the National Cholesterol Education

Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines (33), participants were diagnosed with

metabolic syndrome if they simultaneously met three of the

following five criteria: i) Hypertension as determined by a BP

>130/85 mmHg or taking blood pressure medications; ii) high

serum TG level (>150 mg/dl); iii) high FBS (>110 mg/dl); iv)

low serum HDL level (<50 mg/dl); and v) abdominal obesity as

determined by a WC of >88 cm.

Shift work assessment

Participants were divided into two main groups based

on the work schedules, day workers and shift workers. Participants

who did morning or evening shifts and never did night shift were

considered as day workers. Shift workers included participants who

had rotational work. Shift workers were those participants who

worked 3 shifts of 8 h (morning, evening and night shifts) or who

worked two shifts of 8 h and one of 12 h or who worked 2 shifts of

12 h.

Statistical data analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS (version 16.0;

SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Shift worker and day worker

participants were compared with each other respecting their

demographical, occupational, and reproductive characteristics and

health-associated behaviors using the independent-sample t,

Chi-square and the Fisher's exact tests. Furthermore, logistic

regression analysis was performed to determine the effect of shift

work on the odds of metabolic syndrome following adjustments for

the effects of potential confounders. For regression analysis, the

variable number of sleeping hours was dichotomized as ‘<6 h’ and

‘>6 h’. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Participants' demographical,

occupational and reproductive characteristics

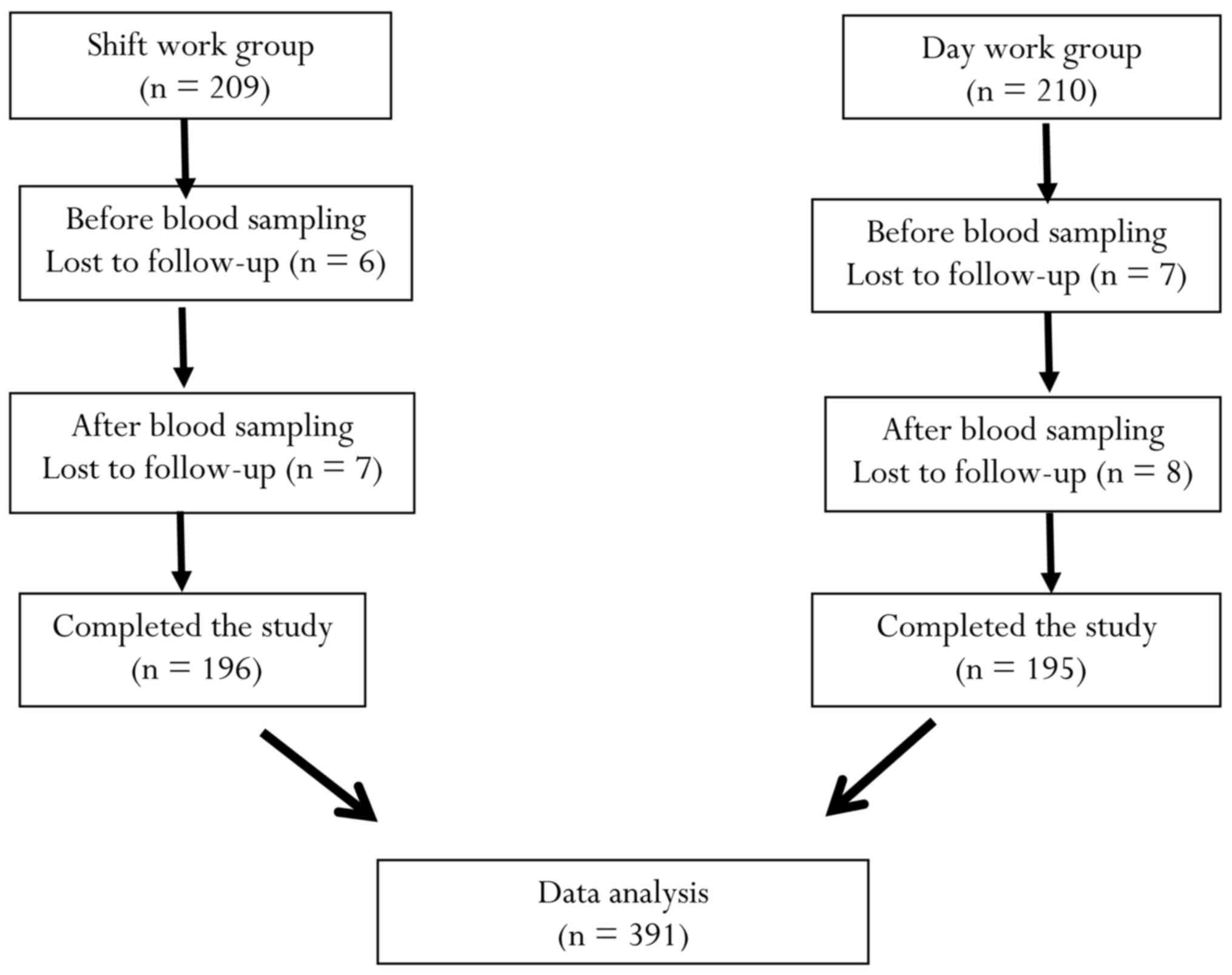

Among the 419 women recruited to the study, 28 were

excluded due to voluntary withdrawal or study incompletion.

Consequently, statistical data analysis was performed on the data

collected from 391 participants (Fig.

1). A total of 196 shift workers and 195 day workers were

included. Those who were excluded from the study did not

significantly differ from participants respecting their

demographical, occupational and reproductive characteristics

(P>0.05).

The mean age and work experience of participants

were 36.12±5.21 and 12.38±5.92 years, respectively, and there was

no statistically significant difference between shift workers and

day workers in terms of age and work experience. Shift workers had

significantly higher levels of Monthly work (h) compared with day

workers. (P<0.001; 192.61±23.33 vs. 179.12±18.76).

The majority of participants held university degrees

(73%), resided in urban areas (84%), were a healthcare provider

(70%), had a heavy workload with high levels of occupational stress

(60%), and had given birth through a caesarean section (70%).

Approximately 50% of women had one child (49.5%). Shift workers had

significantly higher levels of occupational stress compared with

day workers (P=0.02) and participants with more parities had

significantly greater WC measures (P<0.001).

Participants' health-associated

behaviors

One third of participants (33.3%) were physically

active, 2% of them smoked cigarettes and none reported alcohol

consumption. Furthermore, 48% of participants reported having

inadequate sleep. Sleep adequacy among shift workers was

significantly reduced compared with day workers (P=0.006; Table I). In addition, the length of sleep in

a 24-h period among shift workers was significantly shorter

compared with day workers (P<0.001).

| Table IParticipants' demographical,

occupational and reproductive characteristics. |

Table I

Participants' demographical,

occupational and reproductive characteristics.

|

Characteristics | Total N (%) | Shift workers N

(%) | Day workers N

(%) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | | | | 0.26a |

|

20-29 | 46 (11.8) | 27 (13.8) | 19 (9.7) | |

|

30-39 | 222 (55.9) | 113 (57.9) | 109 (55.9) | |

|

40-45 | 122 (31.3) | 55 (28.2) | 67 (34.4) | |

| Educational

level | | | | 0.82a |

|

Bachelor's | 287 (8.73) | 146 (75.3) | 141 (72.3) | |

|

Diploma | 72 (18.5) | 34 (17.5) | 38 (19.5) | |

|

Incomplete

secondary | 87 (13.3) | 14 (4.2) | 16 (8.2) | |

| Place of

residence | | | | 0.20a |

|

Urban

areas | 61 (15.7) | 35 (18.0) | 26 (13.3) | |

|

Rural

areas | 328 (84.3) | 159 (82.0) | 169 (86.7) | |

| Family income | | | | 0.036a |

|

Sufficient | 149 (40.38) | 63 (32.5) | 86 (44.3) | |

|

Moderately

sufficient | 179 (46.1) | 95 (49.0) | 84 (43.3) | |

|

Insufficient | 60 (15.5) | 36 (18.6) | 24 (12.4) | |

| Body mass index

(kg/m2) | | | | 0.27a |

|

<18.5 | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

|

18.5-25 | 131 (33.5) | 69 (35.2) | 62 (31.8) | |

|

25-30 | 176 (45.0) | 81 (41.3) | 95 (48.7) | |

|

>30 | 82 (21.0) | 44 (22.4) | 38 (19.5) | |

| Number of

parities | | | | 0.64a |

|

1 | 185 (49.6) | 91 (48.4) | 94 (50.8) | |

|

≥2 | 188 (50.4) | 97 (51.6) | 91 (49.2) | |

| Route of

delivery | | | | 0.46a |

|

Normal

vaginal delivery | 109 (29.8) | 50 (27.0) | 59 (32.6) | |

|

Cesarean

section | 234 (63.9) | 122 (65.9) | 112 (61.9) | |

|

Both (in

different deliveries) | 23 (6.3) | 13 (7.0) | 10 (5.5) | |

| Physical

activity | | | | 0.057a |

|

Inactive | 143 (38.3) | 61 (33.3) | 82 (43.2) | |

|

Active | 230 (61.7) | 122 (66.7) | 108 (56.8) | |

| Cigarette

smoking | | | | 0.68b |

|

Yes | 5 (1.3) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | |

|

No | 611 (98.1) | 125 (97.7) | 477 (98.1) | |

| Sleep adequacy

(h/day) | | | | 0.006a |

|

Inadequate | 180 (48.0) | 103 (55.1) | 77 (41.0) | |

|

Adequate | 195 (52.0) | 84 (44.9) | 111 (59.0) | |

| Employment

status | | | | 0.17a |

|

Healthcare

provider | 273 (70.7) | 136 (69.4) | 137 (72.1) | |

|

Mother aid

or nurse aid | 61 (15.7) | 38 (19.4) | 23 (12.1) | |

|

Laborer | 34 (8.8) | 15 (7.7) | 19 (10.0) | |

|

Service

worker | 18 (4.7) | 7 (3.6) | 11 (5.8) | |

| Workload | | | | 0.14a |

|

Low to

moderate | 151 (39.6) | 67 (35.3) | 84 (44.0) | |

|

Heavy | 161 (42.3) | 83 (43.7) | 78 (40.8) | |

|

Very

heavy | 69 (18.1) | 40 (21.1) | 29 (15.2) | |

| Occupational

stress | | | | 0.002a |

|

Very

high | 66 (17.3) | 43 (22.6) | 23 (12.0) | |

|

High | 138 (36.1) | 74 (38.9) | 64 (33.3) | |

|

Low to

moderate | 178 (46.6) | 73 (38.4) | 105 (54.7) | |

Association between shift work and

metabolic syndrome

The total prevalence of metabolic syndrome was

16.3%. The rate among shift workers and day workers was 17.3 and

14.9%, respectively, with no statistically significant

between-group difference (P=0.50; Table

II). The most prevalent components of metabolic syndrome among

participants were low serum HDL level (88%) and abdominal obesity

(73%). The prevalence of low serum HDL level among shift workers

was significantly increased compared with day workers (P=0.019).

However, they did not significantly differ from each other

respecting the other components of metabolic syndrome, including

hypertension, dysglycemia, abdominal obesity and

hypertriglyceridemia (P>0.05; Table

II).

| Table IIPrevalence of metabolic syndrome and

its components among shift and day workers. |

Table II

Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and

its components among shift and day workers.

| Metabolic syndrome

and its components | Total N (%) | Shift workers N

(%) | Day workers N

(%) |

P-valuea |

|---|

| BP (mmHg) | | | | 0.29 |

|

<130/85 | 377 (96.2) | 186 (94.9) | 190 (97.4) | |

|

≥130/85 | 15 (3.8) | 10 (5.1) | 5 (2.6) | |

| FBS (Mg/dl) | | | | 0.47 |

|

<110 | 384(98) | 191 (97.4) | 192 (98.5) | |

|

≥110 | 8(2) | 5 (2.6) | 3 (1.5) | |

| WC (cm) | | | | 0.42 |

|

<88 | 105 (26.8) | 49 (25.0) | 56 (28.7) | |

|

≥88 | 287 (73.2) | 147 (75.0) | 139 (71.3) | |

| HDL (Mg/dl) | | | | 0.019 |

|

<50 | 47 (12.0) | 16 (8.2) | 31 (15.9) | |

|

≥50 | 345 (88.0) | 180 (91.8) | 164 (84.1) | |

| TG (Mg/dl) | | | | 0.73 |

|

<150 | 314 (80.1) | 159 (81.1) | 155 (79.5) | |

|

≥150 | 78 (19.9) | 37 (18.9) | 40 (20.5) | |

| Metabolic

syndrome | | | | 0.50 |

|

Yes | 64 (16.3) | 34 (17.3) | 29 (14.9) | |

|

No | 328 (83.7) | 162 (82.7) | 166 (85.1) | |

Logistic regression analysis was used to determine

the odds of metabolic syndrome in relation to shift work. Following

adjustment for the effects of potential demographical, occupational

and medical confounders, the results of the logistic regression

analysis demonstrated that the odds of metabolic syndrome among

shift workers was nearly two times greater compared with day

workers (odds ratio, 1.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.088-3.79;

P=0.10; Table III).

| Table IIIRegression analysis for the

prediction of metabolic syndrome affliction based on work schedule

(shift or day work) adjusted for confounders. |

Table III

Regression analysis for the

prediction of metabolic syndrome affliction based on work schedule

(shift or day work) adjusted for confounders.

| Work schedule | Unadjusted OR (95%

CI) | Model 2 OR (95%

CI) | Model 3 OR (95%

CI) | Model 4 OR (95%

CI) | Model 5OR (95%

CI) |

|---|

| Day workers | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Shift workers | 1.20

(0.7-2.06) | 1.22

(0.71-2.11) | 1.21

(0.69-2.12) | 1.24

(0.77-2.54) | 1.83

(0.88-3.79) |

Discussion

The present study evaluated the association between

shift work and metabolic syndrome among women of reproductive age.

The results revealed that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome

among shift worker participants was 16.3%. However, two previous

studies reported that this rate was 22.4% among healthcare workers

in Iran (32) and 19.8% among

patients in a primary healthcare setting in Germany (34). This contradiction may be due the fact

that the present study was performed on women aged 18-45 years,

while the two previous studies were performed on people from

different age groups. Age is a significant risk factor for

metabolic syndrome (35), a previous

study on 3,024 Iranian women reported that the prevalence of

metabolic syndrome was 20% among women aged 25-34 years and 72%

among women aged 55-64 years (35).

Th present study findings also demonstrated that

shift work doubled the risk of metabolic syndrome. Previous studies

in Iran (7,32) and Italy (36) have reported the same finding. A

probable explanation for the higher risk of metabolic syndrome

among female shift workers in the current study may be their lower

serum HDL level compared to their day worker counterparts. This is

in line with the findings of two earlier studies (8,37). The

results of a meta-analysis on 74,440 Iranians also revealed that

low serum HDL level was the most common predisposing factor for

metabolic syndrome (39). Another

study on Iranian physicians reported that >50% of participants

exhibited low serum HDL levels (40).

Similarly, a study on Egyptian nurses reported that the level of

serum HDL among nurse day worker was twice that of nurse shift

workers (38). Lower levels of serum

HDL among shift workers may be due to circadian disorders (41). Circadian rhythm causes variations in

lipid metabolism (41), whereby

periodical alterations in cholesterol and triglycerides over a 24-h

period are 31.6 for and 38.5%, respectively (16). Accordingly, shift work may result in

dyslipidemia through altering circadian rhythm and

sleep-wakefulness cycle (40).

Although, a previous study indicated no significant association

between serum HDL level and shift work (17).

The present study also demonstrated that sleep

quantity and quality among shift workers were significantly less

compared with that of day workers, and the majority of shift

workers reported that they have inadequate sleep. Sleep has a

mediating role in the association between shift work and metabolic

syndrome (42). This role is probably

due to the negative effects of disturbed sleep among shift workers

on circadian rhythm, subsequent alterations in the metabolism of

serum lipids and endogenous glucose, and effects on glucose

tolerance (42).

The findings in the current study also indicated

that a third of participants regularly performed physical activity.

Furthermore, the rate of regular physical activity among shift

workers was considerably less compared with their day worker

counterparts. Similarly, a study on a group of Iranian nurses

reported that poor physical activity status' due to their multiple

parental and spousal responsibilities, and inadequate time for

engagement in physical activity (43). Regular physical activity can reduce

the risk of metabolic syndrome through reducing WC and body mass

index (44).

None of the participants in the current study

reported alcohol consumption and the majority (98%) did not smoke.

Two earlier studies in Iran also reported the same findings

(7,45). Unlike the high prevalence of low serum

HDL level and abdominal obesity in the present study, only a

limited number of participants (<4%) suffered from hypertension

and diabetes mellitus. These low rates of hypertension and diabetes

mellitus in the present study are attributable to the fact that all

participants were female and <45. Compared with men, women

>50 years are less likely to develop hypertension (46).

Due to time and financial limitations, the current

study was performed using a cross-sectional design. Future studies

are recommended to use cohort designs to provide more reliable data

on the association between shift work and metabolic syndrome.

Additionally, only a third of participants were mother aid, nurse

aid, labourer or service workers. The low number of these workers

in this study was associated with the limited number of welfare and

rehabilitation centers, nursing homes, and industrial female shift

workers in the area.

The results of the current study revealed that shift

work is associated with greater risk of metabolic syndrome among

women of reproductive age. Therefore, metabolic syndrome screening

programs should be essential for female shift workers. In addition,

the present study suggests that the most important components of

metabolic syndrome are low serum HDL level and abdominal obesity,

probably due to the limited physical activity intake and high

occupational stress of female shift workers. Strategies, including

awareness raising, dietary educations, and provision of physical

activity facilities at the workplace may reduce the risk of

metabolic syndrome among female shift workers, and improve their

health status during the reproductive age.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Mohammad Ghasemi

(laboratory technician, Shahid Beheshti Hospital, Babol, Iran) who

helped collect the study data.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Health Research

Institute in Babol University of Medical Sciences (grant no.

9542537).

Authors' contributions

MN, AT, MH, AH, AE, FG, FN, BH and MF contributed in

the design of the study. MN and FH performed measurements of

biomarkers. MN, AT, MH prepared analyzed the data and the first

draft of the manuscript. MN, AT, AE, FG, FN, BH and MF reviewed the

manuscript and provided comments. All authors approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All the datasets generated and analyzed in the

present study are included in this published manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The Ethics Committee of Babol University of Medical

Sciences, Babol, Iran, approved this study (approval no.

MUBABOL.HRI.REC.1395.58). Written informed consent was obtained

from all participants and they were given the right to voluntarily

withdraw from the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

McCullough AJ: Epidemiology of the

metabolic syndrome in the USA. J Dig Dis. 12:333–340.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kawabe Y, Nakamura Y, Kikuchi S, Murakami

Y, Tanaka T, Takebayashi T, Okayama A, Miura K, Okamura T and

Ueshima H: Relationship between shift work and clustering of the

metabolic syndrome diagnostic components. J Atheroscler Thromb.

21:703–711. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Davila EP, Florez H, Fleming LE, Lee DJ,

Goodman E, LeBlanc WG, Caban-Martinez AJ, Arheart KL, McCollister

KE, Christ SL, et al: Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among

U.S. workers. Diabetes Care. 33:2390–2395. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

de Carvalho Vidigal F, Bressan J, Babio N

and Salas-Salvadó J: Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Brazilian

adults: A systematic review. BMC Public Health.

13(1198)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Yu KH, Yi YH, Kim YJ, Cho BM, Lee SY, Lee

JG, Jeong DW and Ji SY: Shift work is associated with metabolic

syndrome in young female Korean workers. Korean J Fam Med.

38:51–56. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Dalvand S, Bakhshi E, Zarei M, Asl MT and

Ghanei R: Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in Iran: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. MSNJ. 5:1–14. 2017.

|

|

7

|

Mohebbi I, Shateri K and Seyedmohammadzad

M: The relationship between working schedule patterns and the

markers of the metabolic syndrome: Comparison of shift workers with

day workers. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 25:383–391.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Guize L, Pannier B, Thomas F, Bean K, Jégo

B and Benetos A: Recent advances in metabolic syndrome and

cardiovascular disease. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 101:577–583.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ginsberg HN and MacCallum PR: The obesity,

metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes mellitus pandemic: Part I.

Increased cardiovascular disease risk and the importance of

atherogenic dyslipidemia in persons with the metabolic syndrome and

type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Cardiometab Syndr. 4:113–119.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Bolton MM: Sounding the alarm about

metabolic syndrome. Nursing. 40:34–40; quiz 40-41. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Cai H, Huang J, Xu G, Yang Z, Liu M, Mi Y,

Liu W, Wang H and Qian D: Prevalence and determinants of metabolic

syndrome among women in Chinese rural areas. PLoS One.

7(e36936)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Chandola T, Brunner E and Marmot M:

Chronic stress at work and the metabolic syndrome: Prospective

study. BMJ. 332:521–525. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kaur J: A comprehensive review on

metabolic syndrome. Cardiol Res Pract. 2014(943162)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Lye MS, Ahmadi N, Khor GL, Hassan STBS,

Hanachi P and Delavar AM: Parity and metabolic syndrome in

middle-aged Iranian women: A cross-sectional study. Casp J Reprod

Med. 1:19–24. 2015.

|

|

15

|

Ye HH, Jeong JU, Jeon MJ and Sakong J: The

association between shift work and the metabolic syndrome in female

workers. Ann Occup Environ Med. 25(33)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Boivin DB and Boudreau P: Impacts of shift

work on sleep and circadian rhythms. Pathol Biol (Paris).

62:292–301. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kim TW, Jeong JH and Hong SC: The impact

of sleep and circadian disturbance on hormones and metabolism. Int

J Endocrinol. 2015(591729)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Morris CJ, Purvis TE, Hu K and Scheer FA:

Circadian misalignment increases cardiovascular disease risk

factors in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 113:E1402–E1411.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Scheer FA, Hilton MF, Mantzoros CS and

Shea SA: Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of

circadian misalignment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106:4453–4458.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Oh JI and Yim HW: Association between

rotating night shift work and metabolic syndrome in Korean workers:

Differences between 8-hour and 12-hour rotating shift work. Ind

Health. 56:40–48. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Karlsson BH, Knutsson AK, Lindahl BO and

Alfredsson LS: Metabolic disturbances in male workers with rotating

three-shift work. Results of the WOLF study. Int Arch Occup Environ

Health. 76:424–430. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Puttonen S, Viitasalo K and Härmä M: The

relationship between current and former shift work and the

metabolic syndrome. Scand J Work Environ Health. 38:343–348.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Nazri SM, Tengku MA and Winn T: The

association of shift work and hypertension among male factory

workers in Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop

Med Public Health. 39:176–183. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Akbari H, Mirzaei R, Nasrabadi T and

Gholami-Fesharaki M: Evaluation of the effect of shift work on

serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Iran Red Crescent Med J.

17(e18723)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Firouzbakht M, Nikpour M and Tirgar A: The

study of impact of employment on gestational age and weight of

newborn. Iran J Health Sci. 3:9–14. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Heydarikhayat N, Mohammadinia N,

Sharifipour H and Almasy A: Assessing frequency and causes of

verbal abuse against the clinical staff. Q J Nurs Manage. 1:70–78.

2012.

|

|

27

|

Tavafi N, Hatami-Zadeh N, Kazem-Nezhad A

and Jazayeri A: Organizational stressors and related stress

intensities in Tehran's comprehensive rehabilitation centers: From

the employees' point of view. jrehab. 7:30–34. 2007.

|

|

28

|

Rajaratnam SM, Howard ME and Grunstein RR:

Sleep loss and circadian disruption in shift work: Health burden

and management. Med J Aust. 199:S11–S15. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Nikpour M, Tirgar A, Ebadi A, Ghaffari F,

Firouzbakht M and Hajiahmadi M: Development and psychometric

evaluation of a women shift workers' reproductive health

questionnaire: Study protocol for a sequential exploratory

mixed-method study. Reprod Health. 15(22)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Sourinejad H, Niyati S and Moghaddam

Banaen L: The metabolic syndrome and its components in

mid-pregnancy in Tehran. J Urmia Nurs Midwifery Fac. 14:465–473.

2016.

|

|

31

|

Amiri A and Hakimi A: The study of

prevalence of metabolic syndrome among nurses of Shahid Mohammadi

Hospital of Bandar Abbas city, Iran. jcnm. 6:1–8. 2017.

|

|

32

|

Niazi E, Saraei M, Aminian O and Izadi N:

Frequency of metabolic syndrome and its associated factors in

health care workers. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 13:338–342.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Expert Panel on Detection Evaluation and

Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults: Executive summary of

the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program

(NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high

blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA.

285:2486–2497. 2001.

|

|

34

|

Moebus S, Hanisch JU, Aidelsburger P,

Bramlage P, Wasem J and Jöckel K-H: Impact of 4 different

definitions used for the assessment of the prevalence of the

Metabolic Syndrome in primary healthcare: The German Metabolic and

Cardiovascular Risk Project (GEMCAS). Cardiovasc Diabetol.

6(22)2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Delavari A, Forouzanfar MH, Alikhani S,

Sharifian A and Kelishadi R: First nationwide study of the

prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and optimal cutoff points of

waist circumference in the Middle East: The national survey of risk

factors for noncommunicable diseases of Iran. Diabetes Care.

32:1092–1097. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Pietroiusti A, Neri A, Somma G, Coppeta L,

Iavicoli I, Bergamaschi A and Magrini A: Incidence of metabolic

syndrome among night-shift healthcare workers. Occup Environ Med.

67:54–57. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Karlsson B, Knutsson A and Lindahl B: Is

there an association between shift work and having a metabolic

syndrome? Results from a population based study of 27,485 people.

Occup Environ Med. 58:747–752. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Gadallah M, Hakim SA, Mohsen A and Eldin

WS: Association of rotating night shift with lipid profile among

nurses in an Egyptian tertiary university hospital. East Mediterr

Health J. 23:295–302. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Daneshpour M, Mehrabi Y, Hedayati M,

Houshmand M and Azizi F: A multivariate study of metabolic syndrome

risk factors, using factor analysis: Tehran Lipid and Glucose

Study. IJEM. 8:139–146. 2006.

|

|

40

|

Chiti H, Shakibi E, Soltani Z,

Mazloomzadeh S and Mousavinasab S: Prevalence of metabolic syndrome

and cardiovascular risk factors among physicians of Zanjan city.

ZUMS J. 24:10–20. 2016.

|

|

41

|

Rivera-Coll A, Fuentes-Arderiu X and

Díez-Noguera A: Circadian rhythmic variations in serum

concentrations of clinically important lipids. Clin Chem.

40:1549–1553. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kim JY, Yadav D, Ahn SV, Koh SB, Park JT,

Yoon J, Yoo BS and Lee SH: A prospective study of total sleep

duration and incident metabolic syndrome: The ARIRANG study. Sleep

Med. 16:1511–1515. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Kalroozi F, Pishgooie S, Taheriyan A,

Khayat S and Faraz R: Health-promoting behaviours and related

factors among nurses in selected military hospitals. Journal of

Faculty of Nursing, AJA university of Medical Sciences. 1:73–80.

2015.

|

|

44

|

Monteiro CA, Conde WL, Lu B and Popkin BM:

Obesity and inequities in health in the developing world. Int J

Obes Relat Metab Disord. 28:1181–1186. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Fotouhi A, Khabazkhoob M, Hashemi H and

Mohammad K: The prevalence of cigarette smoking in residents of

Tehran. Arch Iran Med. 12:358–364. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Everett B and Zajacova A: Gender

differences in hypertension and hypertension awareness among young

adults. Biodemogr Soc Biol. 61:1–17. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|