Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases represent >30% of all

deaths worldwide in 2008(1). Heart

failure alone, one of the consequences of ischemic heart disease,

leads to ~2% of the health expenditure in the whole western world;

therefore, the economic impact of cardiovascular diseases is huge.

Therefore, it is important to identify at-risk patients early in

order to optimize treatment and reduce costs. However, little is

known regarding the association between genetic polymorphism and

cardiovascular mortality risk.

Previous studies have shown a genetic association

between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and cardiovascular

diseases. Special interest has been focused on the low-density

lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1). In particular, the

SNP rs1799986, of LRP1 is associated with increased rates of

premature cardiovascular disease in familial hypercholesterolemia

(2) and rs1466535 was identified in a

genome-wide association study as a novel polymorphism associated

with abdominal aortic aneurysm affecting the gene expression of

LRP1(3). According to Bown et

al (3) functional analyses have

demonstrated that rs1466535 might alter the sterol regulatory

element-binding protein 1 binding site and therefore influence the

activity at the locus.

Interestingly, the association between LRP1 and

platelet-derived growth factor D (PDGF-D) was elucidated by Boucher

et al (4). They demonstrated

that LRP1 forms a complex of the PDGF receptor β and that

inactivation of LRP1 causes abnormal activation of PDGF with

increased risk of atherosclerosis as a result. Therefore, as PDGF

has been shown to be associated with vascular diseases and stroke

(5), LRP1 is even more interesting to

evaluate. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the

possible influence of polymorphisms in LRP1, rs1466535, on

all-cause and cardiovascular (CV) mortality in an elderly primary

health care population, and to identify possible gender differences

as the latter has not been studied before.

Materials and methods

Patient population

The study population consisted of 489 individuals

(men: 248; females: 241) with a mean age of 77.0 years (range: 18

years) living in a rural municipality in the south-east of Sweden,

who were all part of a longitudinal epidemiological study focusing

on CV risk factors (6). All the

participants in that study were invited to participate in the

present sub-study conducted from 13th January 2003 through 18th

June 2005. The blood samples were collected at the University

Hospital of Linköping (Linköping, Sweden). All those living in the

municipality within a specific age bracket were invited to

participate in the longitudinal project in order to minimize bias

in the selection process. The population that agreed to participate

donated blood samples and submitted to echocardiographic

examinations and an electrocardiogram (ECG). The New York Heart

Association functional class was evaluated by the on-site physician

based on the patient information.

All participants gave their written informed consent

and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki principles. The study protocol was approved by the

Regional Ethical Review Board of Linköping, Sweden (Dnr 95044).

Mortality information was obtained from autopsy reports or from the

National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden, which registers all

deaths.

Co-morbidity

In this study the following definitions have been

used; hypertension was defined as a blood pressure of >140/90

mmHg measured in the right arm with the patient in a supine

position after at least 30 min rest. Hypertension was also assumed

if the participant had previously been diagnosed with hypertension

and was receiving antihypertensive medication. Diabetes mellitus

was defined as a previous diagnosis with on-going treatment, or a

fasting blood glucose ≥7 mmol/l measured on a single occasion.

Ischemic heart disease was defined as a history of angina

pectoris/myocardial infarction or ECG-verified myocardial

infarction. Heart failure was defined as a previous diagnosis with

on-going treatment, or symptoms/signs of heart failure and

objective demonstration of reduced cardiac function in terms of

impaired cardiac function on echocardiography. CV death was defined

as death caused by fatal arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, heart

failure, or cerebrovascular insult.

Ultrasound examinations

Echocardiography examinations were performed using

an Accuson XP-128c with the patient in a left supine position.

Values for systolic function were expressed as left ventricular

ejection fraction (EF), and were split into four classes with

interclass limits of 30, 40 and 50%. Normal systolic function was

defined as EF ≥50% (7-9). Thus,

only the systolic function was evaluated.

The abdominal aorta was examined through routine

ultrasound examination, using an Accuson XP-128c ultrasound

machine.

Determination of LRP1 levels in

plasma

All blood samples (20 ml) were obtained while the

patients were at rest in a supine position and all samples were

collected in pre-chilled plastic Vacutainer tubes (Terumo EDTA

K-3); however, 2 ml was used for subsequent analysis. Plasma was

prepared by centrifugation at 3,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C. All

samples were stored at -70˚C until used for analysis. None of the

samples were thawed more than twice.

Plasma levels of LRP1 were measured using a

commercially available ELISA kit (Cloud-Clone Corporation, Houston,

TX, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Plasma samples were

diluted 1:2,000.

Genotype determination

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood using

the QIAmp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany), following

the manufacturer's protocol. Genomic determination was performed as

described in the literature (10).

Briefly, DNA (10 ng) was mixed with TaqMan genotyping master mix

coding rs1466535 in LRP1 gene (assay ID: C 7499211 10; Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and with TaqMan

Universal PCR Master mix II. The 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used with

initial cycle at 50˚C for 2 min, followed by one cycle at 95˚C for

10 min and 40 cycles at 95˚C for 15 sec and at 60˚C for 1 min. The

manual calling option in the allelic discrimination application ABI

PRISM 7500 SDS software, version 1.3.1 (Applied Biosystems; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was then used to assign the genotypes.

Statistical methods

Descriptive data are presented as percentages or

mean and standard deviation (SD). Comparative analyses were

performed using the Student's unpaired two-sided t-test, whereas

the Chi-square test was used for discrete variables. Both

univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression

analyses were used to analyze and illustrate the risk of mortality

during the follow-up period, where both all-cause mortality and CV

mortality were analyzed. Kaplan-Meier graphs were used to

illustrate CV mortality as a function of follow-up time. Censored

patients were those who were still alive at the end of the study

period or who had died of causes other than CV disease. Completed

patients comprised those who had died due to CV disease. In the

multivariate multivariable regression model, adjustments were made

for the following co-variates: Age, hypertension, ischemic heart

disease, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, Hb <120 g/l, EF <40%,

ACE-inhibitors/Angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers,

diuretics, s-cholesterol, s-triglycerides, s-low density

lipoporotein (LDL) and s-high density lipoporoteins (HDL).

In the Cox regressions, the C/T and T/T genotypes

were amalgamated because almost identical mortality figures were

found during the follow-up with the two groups, and because the

group size of the T/T group was small.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. All data were analyzed using standard

software packages (Statistica v. 13.1; Statsoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK,

USA).

Results

The basic characteristics of the study population

divided into gender and genotypes of LPR1 are presented in Table I.

| Table IBasal characteristics of the study

population divided into the three polymorphisms of LRP1. |

Table I

Basal characteristics of the study

population divided into the three polymorphisms of LRP1.

| | LRP1 | |

|---|

| Variable | TT | CT | CC | P-value |

|---|

| n | 65 | 222 | 202 | |

|

Males/females,

n | 25/40 | 107/115 | 105/97 | |

|

Age, mean

(SD) | 77.4 (4.0) | 77.3 (3.6) | 77.7 (3.9) | |

| History | | | | |

|

Diabetes, n

(%) | 13 (20.0) | 56 (25.2) | 47 (23.3) | 0.66 |

|

Hypertension,

n (%) | 49 (75.4) | 171 (77.0) | 163 (80.7) | 0.99 |

|

IHD, n

(%) | 12 (18.5) | 52 (23.4) | 51 (25.2) | 0.53 |

|

NYHA I, n

(%) | 33 (50.8) | 112 (50.5) | 95 (47.0) | 0.75 |

|

NYHA II, n

(%) | 17 (26.2) | 67 (30.2) | 72 (35.6) | 0.27 |

|

NYHA III, n

(%) | 13 (20.0) | 41 (18.5) | 35 (17.3) | 0.88 |

|

NYHA IV, n

(%) | 2 (3.1) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | |

|

Unclassified,

n | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | |

| Medication | | | | |

|

Beta

blockers, n (%) | 24(37) | 70(32) | 93(46) | 0.08 |

|

ACEI/AII, n

(%) | 12(19) | 57(26) | 65(32) | 0.07 |

|

Diuretics, n

(%) | 21(32) | 81(36) | 73(36) | 0.81 |

| Examinations | | | | |

|

BP, systolic

mm Hg, mean (SD) | 151(20) | 148(24) | 150(19) | 0.62 |

|

BP,

diastolic mmHg, mean (SD) | 75(10) | 75(12) | 75(10) | 0.97 |

|

IMT,

thickness, mm (SD) | 0.61 (0.22) | 0.54 (0.16) | 0.59 (0.18) | 0.02 |

|

EF <40%,

n (%) | 5(8) | 14(6) | 20(10) | 0.31 |

Almost equal numbers of males and females were

included (237 vs. 252). In the total study population, 383/489

(78.3%) of the participants had hypertension, 116/489 (23.7%) had

diabetes, 115/489 (23.5%) had ischemic heart disease and 134/489

(27.4%) were receiving treatment with ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin

receptor blockers. Of the population, 187/489 (38.2%) were

receiving treatment with beta-blockers and 175/489 (35.8%) were

receiving treatment with diuretics.

The abdominal aorta of in the study population was

examined and a systolic dimension between 29.3 to 9.7 mm was found.

Based on these measurements there were no signs of abdominal aortic

aneurysms in the individuals examined.

When analyzing the two genders, it was found that

significantly more females with the C/T genotype were receiving

treatment with diuretics compared with the corresponding genotype

among males (47.2% vs. 26.3%; P=0.001), which is in concurrence

with other gender-divided reports (6). In the population with the C/C genotype,

a higher systolic blood pressure was recorded among the females

compared with the males with the same genotype. Also, it could be

demonstrated that there was a larger proportion of participants

with an impaired heart function out of the male population with the

genotypes C/T and C/C, compared with the females with the

corresponding genotypes.

Plasma levels of LRP1

In a small subsection of the study population

(n=221) the level of LRP1 was evaluated using an ELISA. When

evaluating the three genotypes, it could also be seen that the C/C

genotype had a reduced level of LRP1 in comparison with the T/T

genotype [mean 20,994 (SD 7131) pg/ml vs. 23,409 (SD 5651) pg/ml;

P=0.043) and the C/T genotype with a level mean 21534 (SD 7,969)

pg/ml]. No other differences in levels of LRP1 between clinical or

gender groups could be found.

Mortality and genotypes

The median follow-up time of the population was 80

months (6.7 years) and during that time 116 (23.7%) all-cause and

75 (15.3%) CV deaths were registered. Analyzing the three genotypes

and the total number of mortalities, significant differences could

be detected in the distribution of both all-cause and CV mortality,

with a higher mortality in the male population with the C/C

genotype (Table II).

| Table IICardiovascular and all-cause

mortality in the study population distributed in the three

genotypes of LRP1, and gender, during a follow-up period of 80

months. |

Table II

Cardiovascular and all-cause

mortality in the study population distributed in the three

genotypes of LRP1, and gender, during a follow-up period of 80

months.

| | CV mortality | All-cause

mortality |

|---|

| LRP1 | Females | Males | P-value | Females | Males | P-value |

|---|

| C/C, n (%) | 14/97 (14.4) | 32/105 (30.5) |

Χ2=7.38 | 22/97 (22.7) | 47/105 (44.8) |

Χ2=10.9 |

| | | | P=0.007 | | | P=0.0009 |

| C/T, n (%) | 20/115 (17.4) | 21/107 (19.6) | P=0.67 | 35/115 (30.4) | 37/107 (34.6) | 0.51 |

| T/T, n (%) | 6/40 (15.0) | 7/25 (28.0) | 0.20 | 9/40 (23.0) | 11/25 (44.0) | 0.07 |

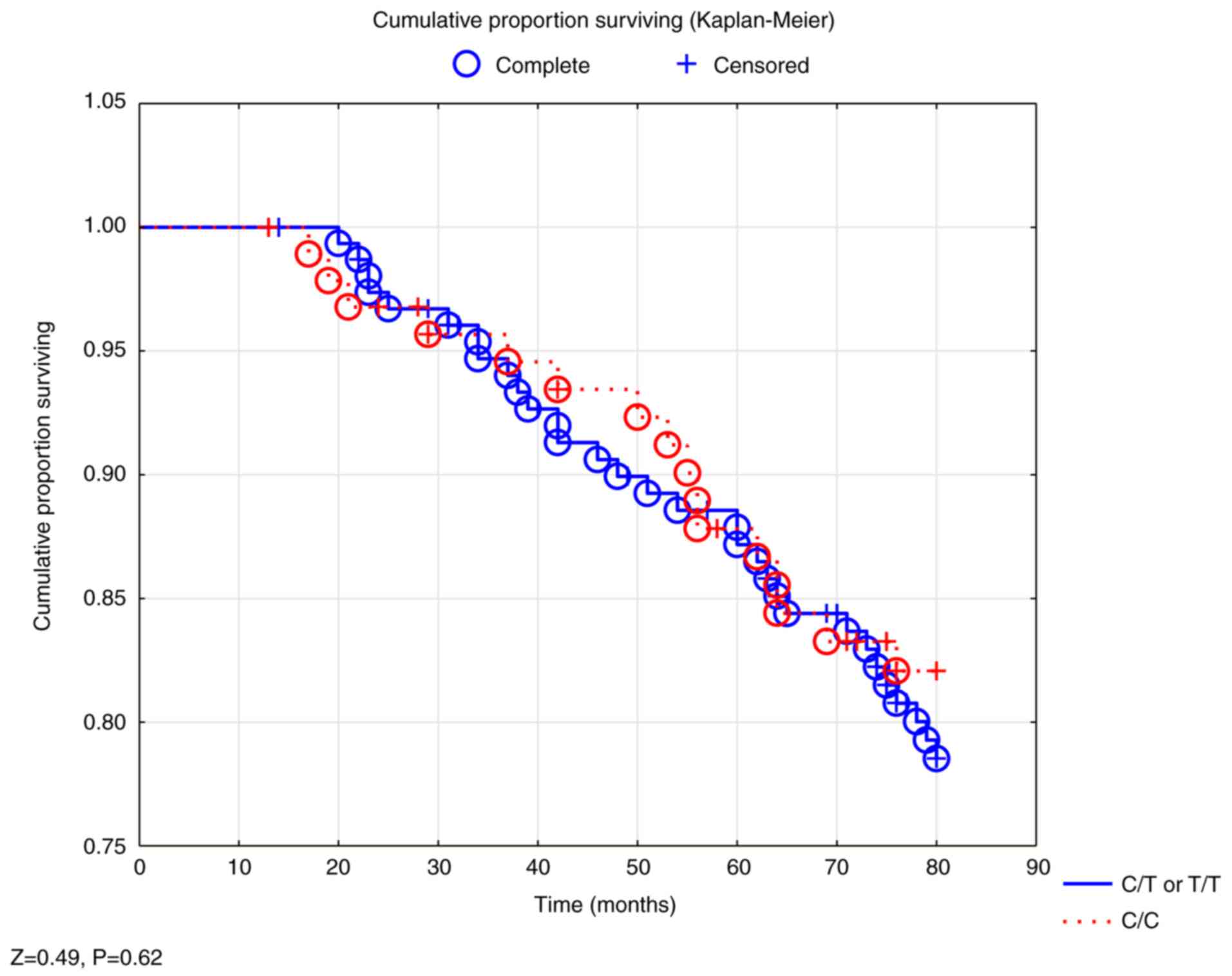

In a survival analysis, no significant difference in

survival could be demonstrated between the three genotypes in the

total study population, nor in the male population (Fig. 1).

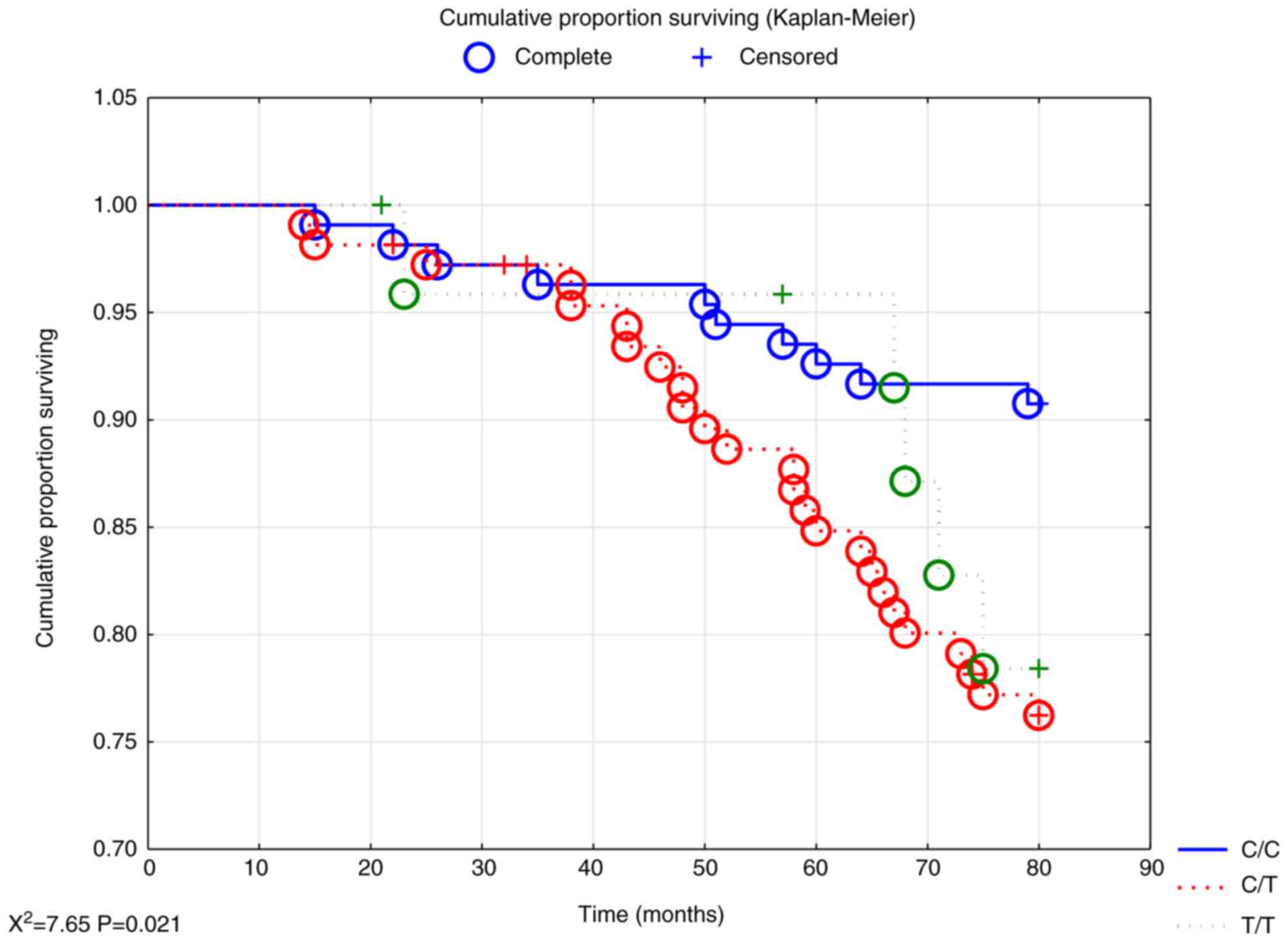

However, evaluating the female population revealed

significant differences in survival between the three genotypes,

where increased all-cause mortality could be seen in the T/T and

C/T genotypes (P<0.05; Fig.

2).

Analyzing mortality risk during the 6.7 years of

follow-up in a multivariate model demonstrated a significantly

increased risk both of all-cause mortality (HR 1.68; 95% CI

1.12-2.52; P=0.01) and CV mortality (HR 2.07; 95% CI 1.23-3.49;

P=0.006) of the total study population for those with the T/T or

C/T genotype (Table III).

| Table IIIMultivariate Cox proportional hazard

regression illustrating risk of cardiovascular and all-cause

mortality in the total population and with a follow-up period of 80

months. |

Table III

Multivariate Cox proportional hazard

regression illustrating risk of cardiovascular and all-cause

mortality in the total population and with a follow-up period of 80

months.

| | CV-mortality | All cause

mortality |

|---|

| Variables | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence

interval | P-value | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence

interval | P-value |

|---|

| Age | 1.07 | 1.00-1.15 | 0.04 | 1.06 | 1.01-1.12 | 0.02 |

| Hypertension | 1.34 | 0.75-2.40 | 0.32 | 1.61 | 0.99-2.61 | 0.06 |

| IHD | 1.21 | 0.70-2.11 | 0.50 | 1.34 | 0.85-2.09 | 0.21 |

| Atrial

fibrillation | 2.39 | 1.29-4.46 | 0.006 | 2.27 | 1.37-3.76 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.64 | 0.97-2.77 | 0.07 | 1.51 | 0.98-2.32 | 0.06 |

| Hb <120 g/l | 1.69 | 0.90-3.17 | 0.10 | 1.26 | 0.71-2.22 | 0.43 |

| EF <40% | 1.72 | 0.82-3.57 | 0.15 | 1.81 | 1.02-3.23 | 0.04 |

| ACEI/ARB | 0.79 | 0.46-1.38 | 0.41 | 0.75 | 0.48-1.18 | 0.21 |

| Beta blockers | 1.27 | 0.76-2.10 | 0.36 | 1.09 | 0.72-1.65 | 0.67 |

| Diuretics | 1.00 | 0.60-1.69 | 0.99 | 1.09 | 0.72-1.65 | 0.69 |

| s-Chol | 0.59 | 0.02-22.4 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.19-3.54 | 0.80 |

| s-Triglyc | 0.99 | 0.18-5.36 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.40-1.82 | 0.69 |

| s-LDL | 1.73 | 0.04-66.7 | 0.77 | 1.11 | 0.26-4.74 | 0.89 |

| s-HDL | 1.49 | 0.04-54.4 | 0.83 | 1.08 | 0.23-5.04 | 0.92 |

| LRP1 C/T or

T/T | 2.07 | 1.23-3.49 | 0.006 | 1.68 | 1.12-2.52 | 0.01 |

Evaluating the female population with the same

multivariate model showed increased risk for all-cause mortality

(HR 2.75; 95% CI 1.28-5.90; P=0.01) and for CV mortality (HR 5.61;

95% CI 1.98-15.85; P=0.001) for those with the T/T or C/T

genotypes, as compared to those with the C/C genotype (Table IV).

| Table IVMultivariate Cox proportional hazard

regression illustrating risk of cardiovascular and all-cause

mortality in the female population and with a follow-up period of

80 months. |

Table IV

Multivariate Cox proportional hazard

regression illustrating risk of cardiovascular and all-cause

mortality in the female population and with a follow-up period of

80 months.

| | CV-mortality | All cause

mortality |

|---|

| Variables | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence

interval | P-value | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence

interval | P-value |

|---|

| Age | 0.98 | 0.88-1.10 | 0.77 | 1.04 | 0.95-1.15 | 0.38 |

| Hypertension | 1.18 | 0.43-3.23 | 0.74 | 1.29 | 0.56-2.98 | 0.55 |

| IHD | 1.69 | 0.60-4.77 | 0.32 | 1.90 | 0.86-4.19 | 0.11 |

| Atrial

fibrillation | 3.38 | 0.95-12.00 | 0.06 | 2.41 | 0.89-6.53 | 0.08 |

| Diabetes | 3.23 | 1.26-8.30 | 0.01 | 1.99 | 0.95-4.14 | 0.07 |

| Hb <120 g/l | 4.12 | 1.62-10.51 | 0.03 | 2.57 | 1.11-5.94 | 0.03 |

| EF<40% | 2.14 | 0.41.11.08 | 0.36 | 0.90 | 0.19-4.35 | 0.90 |

| ACEI/ARB | 0.60 | 0.22-1.65 | 0.32 | 1.08 | 0.50-2.32 | 0.85 |

| Beta blockers | 1.40 | 0.56-3.48 | 0.47 | 1.09 | 0.53-2.24 | 0.81 |

| Diuretics | 2.04 | 0.81-5.15 | 0.13 | 1.85 | 0.86-3.98 | 0.11 |

| s-Chol | 1.08 | 0.19-6.15 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.20-4.01 | 0.88 |

| s-Triglyc | 1.17 | 0.37-3.76 | 0.79 | 0.98 | 0.36-2.68 | 0.96 |

| s-LDL | 0.91 | 0.16-5.07 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.24-4.74 | 0.93 |

| s-HDL | 2.82 | 0.35-22.91 | 0.33 | 1.56 | 0.26-9.48 | 0.63 |

| LRP1 C/T or

T/T | 5.61 | 1.98-15.85 | 0.001 | 2.75 | 1.28-5.90 | 0.01 |

No corresponding increased risk could be seen in the

male population (for all-cause mortality HR 1.19; 95% CI 0.72-1.97;

P=0.49; for CV mortality HR 1.39; 95% CI 0.74-2.60; P=0.31).

Discussion

In this study three genotypes of LRP1 were

evaluated; C/C, C/T and T/T, and different risks of both all-cause,

and CV mortality were demonstrated in different genotypes of the

female population, but not in males. It should be noted that the

population evaluated in this study was an elderly community-living

group and there, a representative one even though the sample size

was not large. The results are interesting as they show

gender-specific differences both regarding all-cause and to a

greater extent CV mortality. The main project has been presented in

several previous publications (11-22).

That genetic variance could result in effects on

CV-associated mortality is well-known from the literature (23-25).

However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the

first time that differences in gender-specific risk in mortality

that are associated with a genetic variance have been

demonstrated.

In recent years, special interest has been focused

on LRP1 and its possible association with CV diseases. Gonias

(26) demonstrated in an excellent

review the important relationship between LRP1 and smooth muscle

cell properties. In a report from Italy, Galora et al

(27) demonstrated an interesting

association between the T allele of rs1466535 and abdominal aortic

aneurysms, but not with the other alleles investigated. The present

study was able to confirm that the T allele also had an association

with mortality, but only in one of the two genders. Ye et al

(28) in a study of abdominal

aneurysms, demonstrated significant sex differences, where a faster

expansion of the aneurysms could be seen in the female group and

therefore the present study intended to evaluate any sex

differences in CV mortality in the different genotypes of

rs1466535.

As Giusti et al (29) reported, the present study also found

that the majority of participants had the C/C genotype and only a

small number had the T/T genotype. After combining the T/T and the

C/T genotypes, Giusti was able to report a greater proportion of

patients suffering from carotid stenosis in this group compared

with the C/C genotype. The same amalgamating process of the T/T and

C/T genotypes in the evaluations was performed in the present

study.

In the literature there are reports of a study with

a larger number of participants compared to the present study, such

as the huge genome-wide association study for coronary artery

disease reported by Webb et al (30), which included more than 120,000

participants. However, the important difference compared with the

present study is that mortality data for all participants is

included; no one was lost during the follow-up period of 6.7 years.

CV mortality is regarded as the definite endpoint of the CV risks

that the participants were exposed to, rather than getting

diagnosed with coronary artery disease, as was done in the

genome-wide association study mentioned above, which is why the

small study sample reported in the present study is notable.

In the ELISA evaluation of the levels of LRP1, a

significant difference was demonstrated in the levels between the

T/T and the C/C genotypes, a fact that has not been reported before

to the best of our knowledge. In the genome-wide study by Bown

et al they reported a tendency toward an increased level of

the C/C genotype of LRP1 in comparison with the T/T genotype

(3). However, Bown et al

reported on a population with abdominal aortic aneurysms, something

that the population of the present study did not have and thus it

is not surprising that the opposite results were reported regarding

the level of the C/C genotype of LRP1.

The female population of individuals with the T/T or

C/T genotypes of LRP1 demonstrated a 2.75-fold increased risk of

all-cause mortality and a 5.61-fold increased risk of CV mortality

when applying a multivariate model adjusting for certain well-known

variables influencing the CV mortality risk. However, it should be

pointed out that the confidence interval is wide in the evaluation,

so it is important to interpret the point estimate of the HR with

caution. The wide confidence interval is probably the result of the

limited size of the different genotype groups analyzed. The

important message is that an increased mortality risk exists in the

C/T and T/T genotypes in comparison with the C/C genotype. In the

male population no such prognostic differences between the

different genotypes of LRP1 could be found. This could imply that

irrespective of the LRP1 genotype, there are stronger factors that

determine the mortality risk in the male group, for example

mortality based on ischemic heart disease, a condition with a

substantial preponderance in the male population.

In the literature there are a multitude of reports

indicating that there are gender differences regarding CV mortality

in general and a higher mortality is generally reported in the male

population of corresponding age, compared to the female population

(31,32). The major reason for this is the higher

incidence of ischemic heart disease among males (33). It is possible that the SNP may in some

(secondary) way be influenced by variation in genes situated on the

sex chromosomes, or by hormonal differences between men and women,

and this should be a focus of further study.

The presented gender differences in some of the

genotypes of LRP1 are of importance in clinical routine since

individuals with increased risk for CV mortality can be identified.

Even if it is not possible to modify the genetic constitution, it

is possible to provide more intense prevention procedures and an

individualized follow-up program for patients, which also may

reduce CV mortality and health care costs.

It should also be noted that the genetic analyses

exhibited in the present study were conducted at a cost that was

below the cost for analyses of the golden-standard biomarker used

to identify patients with heart failure, the N-terminal fragment of

the natriuretic peptide proBNP. Thus, it was concluded that the

presented genetic analyses are also cost-effective in the

clinic.

It could be argued that it would only be relevant to

evaluate the at-risk genotypes in an at-risk population. However,

this assumption is only correct in a population with known or

assumed increased risk and this is usually not the case in the

clinical routine. Therefore, elderly persons from a

community-living population with mixed CV risks were included to

better reflect the situation that clinicians are faced with every

day. Despite this fact, it was possible to obtain significant and

interesting data indicating that certain individuals are exposed to

an increased risk that can be identified through genotype

evaluation.

Therefore, out of the female group, those with the

C/T or T/T genotypes of the LPR1 gene, with a more than 5-fold

increased risk of CV mortality, constituted a high-risk population

and thus it was important to identify them, even though the

obtained point estimate should be interpreted with caution due to

the limited sample size.

However, from a clinical and economical point of

view it is also interesting to identify those with a low risk of

mortality. As the present study demonstrated above, the females

with the C/C genotype of LRP1 only exhibited a 9.3% all-cause and a

4.6% CV mortality during almost seven years of follow-up in spite

of being an elderly patient group. From this it could be concluded

that identifying both those at high as well as those at low risk of

death is important from a clinical point of view and the use of

genetic information could further aid in this identification

process.

The presented research is a community-based study

and thus includes most patients with discrete or no CV symptoms.

Therefore, those with CV disease are in a minority and thus the

size of the CV group is small, which results in wide CIs in risk

evaluations, thus making their interpretation uncertain.

Also, the presented study population is an elderly

one and therefore it is not possible to extrapolate the obtained

results into other age groups without uncertainty.

Finally, as the subgroups of those with certain

genotypes are small, the results of some of the evaluations should

be interpreted with caution and the results should be regarded as

hypothesis-generating. However, the results of the present study

are in line with and strengthen previous findings and a hypothesis

that the investigated genes and SNPs could play an important role

as markers to identify individuals at risk.

In conclusion, information regarding the LRP1 gene

was applied to an elderly primary health care population that was

followed for almost seven years and where all mortality was

registered. Specific gender differences were noted, and in the

female group those with the LRP1 T/T or C/T genotype had a

5.61-fold increased risk for CV mortality in the multivariate

analysis.

In the male group however, no such gender difference

could be found.

Applying a combined analysis using, for the females,

those with LRP1 C/T or T/T could substantially increase the

possibility of identifying individuals with high CV risk and

thereby help to optimize CV prevention and treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank research nurse Mrs.

Anette Gylling for all her valuable help in preparation of the

blood samples.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the

County Council of Östergötland, University of Linköping, Linköping,

Sweden and the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

Under Swedish Law, the datasets generated/analyzed

are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding

author upon reasonable request and with permission of the

University of Linköping.

Authors' contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: UA and DW;

performed the experiments: UA and DW; analyzed the data: UA and DW;

contributed reagents/material/analysis tools: DW; wrote the

manuscript: UA and DW.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All participants gave their written informed consent

and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki principles. The study protocol was approved by the

Regional Ethical Review Board of Linköping, Sweden (Dnr 95044).

Patient consent for publication

All participants gave their written informed

consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Alwan A: Global report on noncommunicable

diseases 2010. Italy, World Health Organization. 2011.

|

|

2

|

Aledo R, Alonso R, Mata P, Llorente-Cortés

V, Padró T and Badimon L: LRP1 gene polymorphisms are associated

with premature risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with

familial hypercholesterolemia. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed).

65:807–812. 2012.(In English, Spanish). PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Bown MJ, Jones GT, Harrison SC, Wright BJ,

Bumpstead S, Baas AF, Gretarsdottir S, Badger SA, Bradley DT,

Burnand K, et al: Abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with a

variant in low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1. Am J

Hum Genet. 89:619–627. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Boucher P, Gotthardt M, Li WP, Anderson RG

and Herz J: LRP: Role in vascular wall integrity and protection

from atherosclerosis. Science. 300:329–332. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Folestad E, Kunath A and Wågsäter D:

PDGF-C and PDGF-D signaling in vascular diseases and animal models.

Mol Aspects Med. 62:1–11. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Alehagen U, Ericsson A and Dahlström U:

Are there any significant differences between females and males in

the management of heart failure? Gender aspects of an elderly

population with symptoms associated with heart failure. J Card

Fail. 15:501–507. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Pombo JF, Troy BL and Russell RO Jr: Left

ventricular volumes and ejection fraction by echocardiography.

Circulation. 43:480–490. 1971. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wahr DW, Wang YS and Schiller NB: Left

ventricular volumes determined by two-dimensional echocardiography

in a normal adult population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1:863–868.

1983.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Gibbons RJ, Lee KL, Cobb F and Jones RH:

Ejection fraction response to exercise in patients with chest pain

and normal coronary arteriograms. Circulation. 64:952–957.

1981.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Shamoun L, Skarstedt M, Andersson RE,

Wågsäter D and Dimberg J: Association study on IL-4, IL-4Rα and

IL-13 genetic polymorphisms in Swedish patients with colorectal

cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 487:101–106. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ljungberg L, Alehagen U, Länne T, Björck

H, De Basso R, Dahlström U and Persson K: The association between

circulating angiotensin-converting enzyme and cardiovascular risk

in the elderly: A cross-sectional study. J Renin Angiotensin

Aldosterone Syst. 12:281–289. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Björck HM, Länne T, Alehagen U, Persson K,

Rundkvist L, Hamsten A, Dahlström U and Eriksson P: Association of

genetic variation on chromosome 9p21.3 and arterial stiffness. J

Intern Med. 265:373–381. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ljungberg LU, De Basso R, Alehagen U,

Björck HM, Persson K, Dahlström U and Länne T: Impaired abdominal

aortic wall integrity in elderly men carrying the

angiotensin-converting enzyme D allele. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg.

42:309–319. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Johansson P, Alehagen U, Ulander M,

Svanborg E, Dahlström U and Broström A: Sleep disordered breathing

in community dwelling elderly: Associations with cardiovascular

disease, impaired systolic function, and mortality after a six-year

follow-up. Sleep Med. 12:748–753. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chisalita SI, Dahlström U, Arnqvist HJ and

Alehagen U: Increased IGF1 levels in relation to heart failure and

cardiovascular mortality in an elderly population: Impact of ACE

inhibitors. Eur J Endocrinol. 165:891–898. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Johansson P, Alehagen U, Svanborg E,

Dahlström U and Broström A: Clinical characteristics and mortality

risk in relation to obstructive and central sleep apnoea in

community-dwelling elderly individuals: A 7-year follow-up. Age

Ageing. 41:468–474. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ljungberg LU, Alehagen U, De Basso R,

Persson K, Dahlström U and Länne T: Circulating

angiotensin-converting enzyme is associated with left ventricular

dysfunction, but not with central aortic hemodynamics. Int J

Cardiol. 166:540–541. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Johansson P, Riegel B, Svensson E,

Broström A, Alehagen U, Dahlström U and Jaarsma T: The contribution

of heart failure to sleep disturbances and depressive symptoms in

older adults. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 25:179–187.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Johansson P, Riegel B, Svensson E,

Broström A, Alehagen U, Dahlström U and Jaarsma T: Sickness

behavior in community-dwelling elderly: Associations with impaired

cardiac function and inflammation. Biol Res Nurs. 16:105–113.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Johansson P, Svensson E, Alehagen U,

Jaarsma T and Broström A: The contribution of hypoxia to the

association between sleep apnoea, insomnia, and cardiovascular

mortality in community-dwelling elderly with and without

cardiovascular disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 14:222–231.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chisalita SI, Dahlström U, Arnqvist HJ and

Alehagen U: Proinsulin and IGFBP-1 predicts mortality in an elderly

population. Int J Cardiol. 174:260–267. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Alehagen U, Vorkapic E, Ljungberg L, Länne

T and Wågsäter D: Gender difference in adiponectin associated with

cardiovascular mortality. BMC Med Genet. 16:37:2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Eppinga RN, Hagemeijer Y, Burgess S, Hinds

DA, Stefansson K, Gudbjartsson DF, van Veldhuisen DJ, Munroe PB,

Verweij N and van der Harst P: Identification of genomic loci

associated with resting heart rate and shared genetic predictors

with all-cause mortality. Nat Genet. 48:1557–1563. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ansani L, Marchesini J, Pestelli G, Luisi

GA, Scillitani G, Longo G, Milani D, Serino ML, Tisato V and

Gemmati D: F13A1 gene variant (V34L) and residual circulating

FXIIIA levels predict Short- and Long-term mortality in acute

myocardial infarction after coronary angioplasty. Int J Mol Sci.

19pii. (E2766)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Heijmans BT, Westendorp RG, Knook DL,

Kluft C and Slagboom PE: Angiotensin I-converting enzyme and

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene variants: Risk of mortality

and fatal cardiovascular disease in an elderly population-based

cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 34:1176–1183. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Gonias SL: Mechanisms by which LRP1

(Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein-1) maintains

arterial integrity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 38:2548–2549.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Galora S, Saracini C, Pratesi G, Sticchi

E, Pulli R, Pratesi C, Abbate R and Giusti B: Association of

rs1466535 LRP1 but not rs3019885 SLC30A8 and rs6674171 TDRD10 gene

polymorphisms with abdominal aortic aneurysm in Italian patients. J

Vasc Surg. 61:787–792. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Ye Z, Austin E, Schaid DJ, Bailey KR,

Pellikka PA and Kullo IJ: A DAB2IP genotype: Sex interaction is

associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion. J Investig

Med. 65:1077–1082. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Giusti B, Galora S, Saracini C, Pratesi G,

Gensini GF, Pulli R, Pratesi C and Abbate R: Role of rs1466535 low

density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) gene

polymorphism in carotid artery disease. Atherosclerosis.

237:135–137. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Webb TR, Erdmann J, Stirrups KE, Stitziel

NO, Masca NG, Jansen H, Kanoni S, Nelson CP, Ferrario PG, König IR,

et al: Systematic evaluation of pleiotropy identifies 6 further

loci associated with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol.

69:823–836. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Kappert K, Böhm M, Schmieder R, Schumacher

H, Teo K, Yusuf S, Sleight P and Unger T: ONTARGET/TRANSCEND

Investigators. Impact of sex on cardiovascular outcome in patients

at high cardiovascular risk: Analysis of the Telmisartan randomized

assessment study in ACE-intolerant subjects with cardiovascular

disease (TRANSCEND) and the ongoing telmisartan alone and in

combination with ramipril global end point trial (ONTARGET).

Circulation. 126:934–941. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Regitz-Zagrosek V, Oertelt-Prigione S,

Seeland U and Hetzer R: Sex and gender differences in myocardial

hypertrophy and heart failure. Circ J. 74:1265–1273.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Dudas K, Björck L, Jernberg T, Lappas G,

Wallentin L and Rosengren A: Differences between acute myocardial

infarction and unstable angina: A longitudinal cohort study

reporting findings from the Register of Information and Knowledge

about Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admissions (RIKS-HIA). BMJ Open.

3pii. (e002155)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|