Introduction

Chemicals constitute a part of everyday life.

Approximately 1,000 new chemicals are placed on the market each

year, usually found as mixtures in commercial products, while more

than 100,000 chemical substances are used worldwide (1). Many of these chemicals may, especially

if not properly used, possess hazards for human health and be toxic

to the environment.

The hazards of chemicals can be classified based on

physical, chemical and ecotoxicological endpoints using criteria

developed in the framework of scientific or regulatory processes

(2). A number of national and

international schemes have been developed over the past 50 years.

To avoid multiplicity and confusion at the user level, the globally

harmonized system (GHS) for the classification and labeling of

chemicals was adopted in 1992 during the Rio Earth summit. GHS

includes easily understandable symbols that can be applied in the

manufacture, transport, use and disposal of chemical substances

(2).

At a European Union (EU) level, two Regulations have

been introduced, Regulation (EC) 1907/2006 (REACH) and Regulation

(EC) 1272/2008 aimed to effectively handle hazards and risks from

chemicals. The new EU chemicals legislation applies to all industry

sectors dealing with chemicals along the entire supply chain. It

therefore makes companies responsible for the safety of chemicals

they place on the market.

The CLP Regulation, which is based on GHS, ensures

that the hazards presented by chemicals are clearly communicated to

workers and consumers in the European Union through the

classification and labelling of chemicals. The industry must

establish the potential risks to human health and the environment

of substances and mixtures prior to placing them on the market as

commercial products, by classifying them using the classification,

labelling and packaging (CLP) criteria, in line with the identified

hazards. The need to develop harmonized criteria for classification

is essential in ensuring effective communication of the risk

(3). Hazardous chemicals also have to

be accordingly labeled using hazard and precautionary statements

and pictograms.

In addition, suppliers established in the EU and

placing hazardous products on the market have to provide

standardised information to be used only by Poison Centres (Article

45 of the CLP). The Poison Centres provide medical advice in case

of poisoning due to exposure to hazardous chemicals or to other

toxic agents to the general public and to physicians. Poison

centres in the EU answer on average 600,000 calls for support each

year. However, EU legislation does not specify the precise

information needed for this product notification. Therefore,

varying requirements have been developed by each EU member state

(4).

Safety data sheets (SDSs) are the main communication

tool under the REACH Regulation between suppliers and users of

substances and mixtures and it is a regulatory obligation for the

industry. SDSs include information on the physical, chemical and

hazardous properties of the substance or mixture as well as

instructions for their handling, disposal and transport, and for

first-aid, fire-fighting and exposure control measures.

The aim of the present study was to assess for the

first time, to the best of our knowledge, the level of

comprehension of the hazard and risk communication and awareness

regarding the safe use of chemicals among Greek professional users

and health care specialists eight years after the introduction of

the respective EU legislation.

Materials and methods

A total of 1,500 individuals (850 industrial workers

and professional users of chemicals from 35 different small and

medium enterprises, self-employed professionals included, and 650

health care specialists from 6 public and private hospitals/medical

centres, 40 private practitioners included), in Athens;

Thessaloniki; Larissa; Ionnina; Patras and Heraklion Crete, Greece,

were asked to answer an anonymous validated, self-administered

questionnaire with 26 close-ended questions from May 2016 to April

2017. The questionnaire was left at the reception desk of the

various workplaces, accompanied with an explanatory opening page,

where it was stated that the results of the survey were to be

published. The return of the completed questionnaire was considered

as written consent of the study population. A total of 350

individuals (200 workers and professional users, 150 health care

specialists) returned the questionnaire by placing it in a

specifically marked receptacle at the reception desk of the various

workplaces (return rate 23.3%, in the range of the typical

self-completed surveys) (5).

The questionnaire was developed at the University of

Thessaly, Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology (Larissa,

Greece) in the framework of the MSc Course on Toxicology and was

structured in three sections. The first section addressed

demographic information (6 questions); the second investigated the

risk/hazard communication of chemicals (14 questions); and the

third explored the use and application of personal protective

measures (6 questions).

Once the questionnaire was constructed, a

multidisciplinary group of professionals that were not

participating in the research group was asked to review the

document and provide input. This expert group consisted of a

toxicologist, a regulatory officer, an officer from the industry

and a psychiatrist. The group provided input on the general content

and face validity of the questionnaire (Content Validity Ratio-CRV

=0.993, P<0.05) (6), which was

proven complete and adequate for distribution.

The 103rd General Assembly of Specific Interest

(09/03/2016) of the Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology,

University of Thessaly, provided approval for the conduct of the

study and distribution of the questionnaire, as part of the

dissertation theses of the students M.A. and I.K.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS

22.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive data were

calculated as frequencies and percentages. Chi-square

(χ2) tests were computed to reveal meaningful

associations between supplements use and the categorical study

variables (sex and level of education) and Pearson's correlation

was performed for continuous variables (i.e., age and exercise

years). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the study

population are shown in Table I.

Professional users (group 1) and health care specialists (group 2)

were of statistically similar age (P=0.323) and work experience

(P=0.224). Women are statistically more in the health care

specialists group, while men dominate the professional workers

group. Twenty different professions were identified in the

participants of group 1, including industrial workers (chemical

products, plastics, pharmaceuticals, food industry and energy

products/fuels), gas station employees, painters, carpenters,

farmers, hairdressers and drivers. The vast majority of these

professions belong to the private sector (>80%). The level of

education in group 1 was significantly lower than 2, as expected.

More specifically, in group 1, 81% of the responders did not go to

University or attend post-graduate courses, whereas in group 2 the

respective value was 29%. Of note is the low percentage of

professional users of chemicals with no diagnosed health problems

(28%), while the prevalence of allergies (skin and respiratory

system) is high in this population (>50%). The picture is

opposite in health care specialists.

| Table I.Demographical characteristics and

diagnosed health status, type of working activity, work experience

and educational level of the studied population. |

Table I.

Demographical characteristics and

diagnosed health status, type of working activity, work experience

and educational level of the studied population.

| Characteristics | Professional

users | Health care

specialists |

|---|

| Population (no) | 200 | 150 |

| Age (years) | 41.8±7.5 (21–61) | 38.8±9.5 (24–64) |

| Sex |

|

|

| Male | 115 (60) | 55 (37) |

| Female | 85 (40) | 95 (63) |

| Occupation |

|

|

| Workers (private

sector) | 78 (39) |

|

| Workers (public

sector) | 37 (18) |

|

| Self-employed | 85 (42) |

|

| Medical doctors |

| 116 (77)a |

| Nurses |

| 22 (15) |

| Clinical

chemists |

| 12 (8) |

| Working experience

(years) | 12.0±8.80 (1–40) | 16.2±9.78 (5–52) |

| Education |

|

|

| Primary | 42 (21) | 0 (0) |

| Secondary | 74 (37) | 11 (7) |

| Technological | 46 (23) | 33 (22) |

| University | 22 (11) | 63 (42) |

| Post-graduate | 18 (9) | 51 (32) |

| Diagnosed health

problems |

|

|

| None | 56 (28) | 104 (69) |

| Dermatological

problems | 66 (33) | 4 (3) |

| Respiratory

problems | 38 (19) | 4 (3) |

| Musculoskeletal

problems | 20 (10) | 9 (6) |

| Cardiovascular

problems | 4 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Hypertension | 10 (5) | 9 (6) |

| Other | 6 (3) | 18 (12) |

Perception of various GHS

pictograms

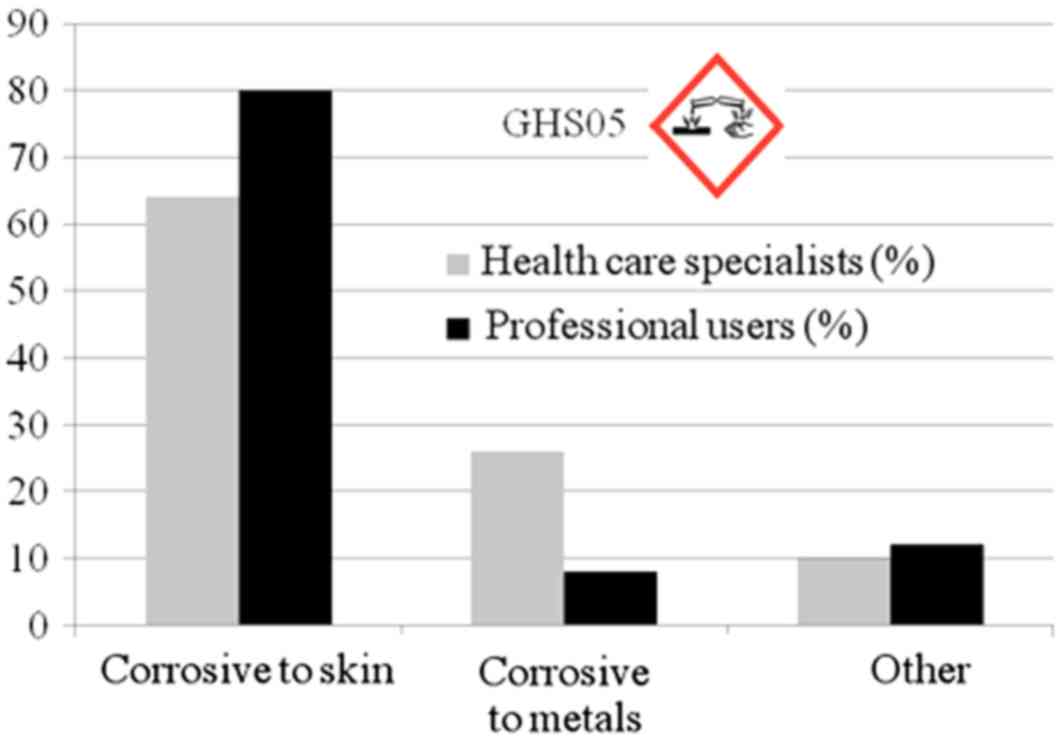

In several issues the two groups had statistically

similar responses. Over 85% of the responders are not aware of the

CLP Regulation per se, while 20% of professional users of chemicals

are aware of the REACH Regulation. Over 65% of the responders did

not notice any changes in the labeling of the products being used.

The most common pictogram encountered is the old hazard symbol of a

black cross on an orange background from the Dangerous

Substances/Products Directives (approximately 40%), which became

obsolete in June 2015. In general, 50–60% of professional users

perceive pictograms adequately, while for health care specialists

the percentage rises to 80%. Nevertheless, both groups understand

only the corrosive hazard for the skin/eyes in pictogram GHS05 and

only 8% in group 1 and 26% in group 2 also comprehended the

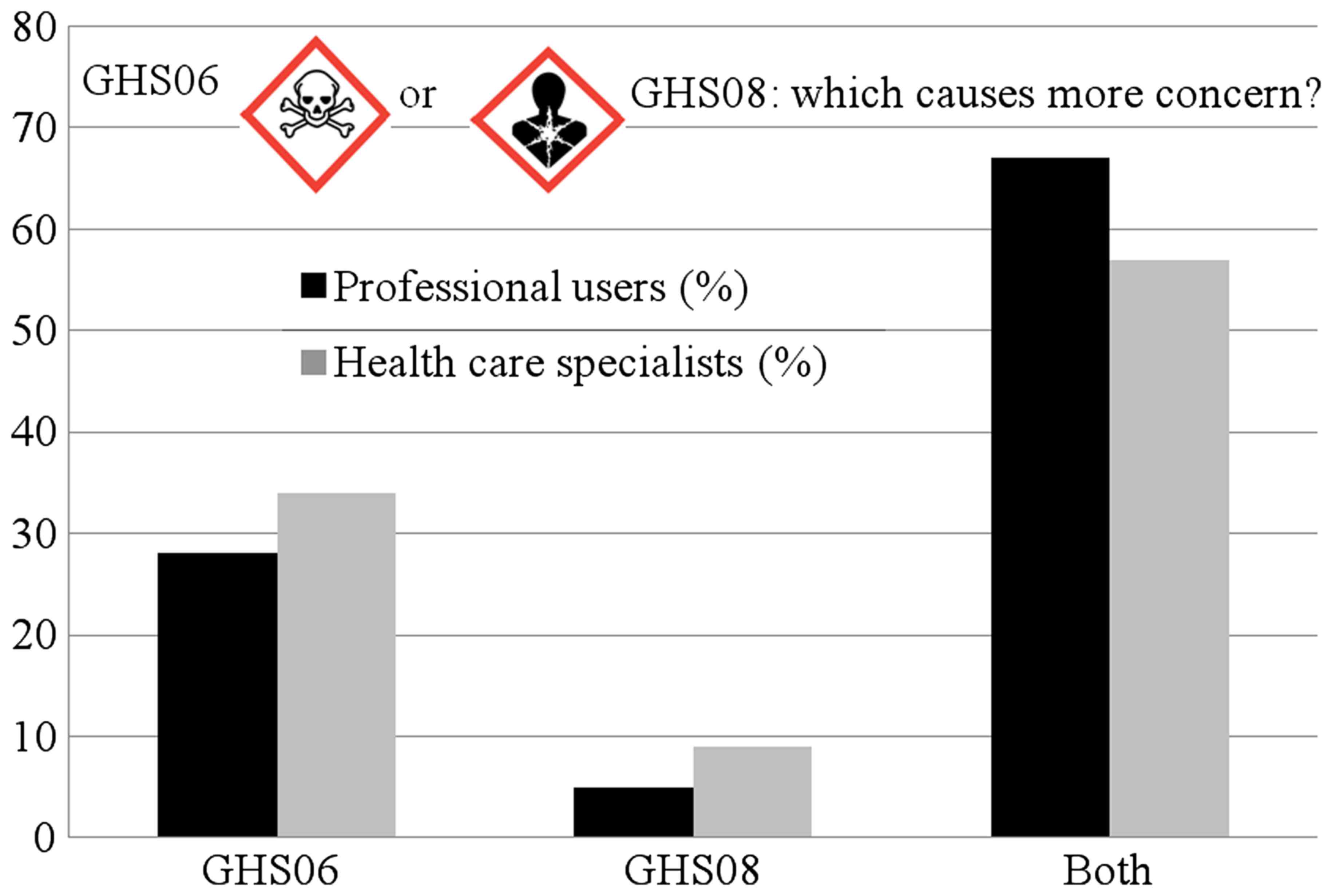

corrosivity for metals depicted by the same pictogram (Fig. 1). Over 65% of the responders consider

pictograms GHS06 and GHS08 equally hazardous for human health, but

only 5% in group 1 expect carcinogenicity or reproductive toxicity

to be communicated with the use of GHS08 (Fig. 2).

The majority of the responders (>75%) are aware

of the use of hazardous products during their everyday life, but

the perception of hazard and the severity varies significantly

between the two groups (P=0.012) and statistically depends on the

educational (P=0.022) and professional (P=0.014) level.

Professional users declare that they commonly use flammable liquids

(26%), while 7% declare use of carcinogens and chemicals hazardous

for the environment.

In general, age (P=0.02), work experience (P=0.025)

and profession (P=0.022) significantly correlate with the level of

familiarization with CLP. One third of the professional users

enrolled in this study read the label as the main source of

information for the product, while for health care specialists the

number increased to 65%. A strong correlation was detected with the

educational level of the responders (P=0.017). In both groups a

significant 7% declared that hazard communication through the

labeling of the product is not well understood. Limited use of SDSs

regarding the safe use of chemicals has been observed both in

professional users (18%) and in health care specialists (23%).

The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) is

almost universal in health care specialists with women being more

sensitive (P=0.041), while 25% of the professional users do not use

any PPE. In addition, 30% of the professional users who use PPE, do

so after being instructed by their employer or the shift

supervisor. The most commonly recommended PPE are gloves (50% in

group 1 and 80% in group 2) followed by protective goggles/mask

(35% in group 1 and 15% in group 2). Nevertheless, when it comes to

everyday practice, only gloves are used in group 1. In both groups,

15% of the responders do not take any special precautions regarding

their workware at home, while younger (P=0.015) and more educated

(P=0.035) users of chemicals utilize special cleaning

practices.

Almost 60% of the health care specialists

interviewed have been informed on the safe use of chemicals or

actions to be undertaken in case of accident. In the latter

situation, the National Poisoning Centre is the reference point for

information, whereas 20% of the health care specialists prefer

SDSs.

Discussion

Use of chemicals in the work environment may have

consequences on human health, which influences the protection

measures that need to be employed and the supportive system in case

of accidents or poisonings by health care specialists.

Workers in gas stations are reported to suffer from

headaches (32%) and fatigue (20%) (7). In addition, a statistically significant

increase in red blood cell counts, haemoglobin, mean corpuscular

hemoglobin and platelet counts were found in all self-reported

health-related complaints among liquefied petroleum gas workers

(8). These symptoms are directly

associated with benzene inhalation and workers are found to be

exposed regardless of their position in the gas station (9,10).

The prevalence of respiratory and pulmonary problems

and even cholangiocarcinoma in printing workers is markedly

elevated, with concerns also being applicable for consumers

(11–13). In addition the association between

exposure to chemicals and asthma and rhinitis remains independent

of exposure to dust (14). A

meta-analysis of 13 European cohorts spanning births from 1994 to

2011 indicated that employment during pregnancy in occupations

classified as possibly or probably exposed to endocrine disruptors

was associated with an increased risk of term (15). An association has also been reported

between textile industry and different types of cancer including

lung, bladder, colorectal and breast cancer (16).

In the present study, 72% of professional users of

chemicals face health issues connected to skin and respiratory

sensitisation.

Several studies have attempted to elucidate the

comprehension of the legislation on chemicals and the hazard

communication among workers and the general public (17–21).

Pictograms are the prevailing element in hazard/risk

communication. It has been shown that the underlying core elements

that enhance understanding of GHS pictograms, which are also

essential in developing competent individuals in the use of SDSs,

are training and education (22).

Cleaning workers found not to be familiar with the pictograms had

not been properly informed on the safe usage of chemicals by their

employers (20). Age and educational

level may impact workers' performance and cognitive process of

comprehension of pictograms (19), as

evidenced in the present study. Some pictograms are more easily

perceived, while others remain controversial, such as GHS05, GHS06

and GHS08, as identified in our study. Similar concerns have been

raised regarding the labeling of fragrances (23).

In a meta-analysis of 9 research studies published

from 1983 to 2005 evaluating the relationship between literacy and

hazard communication three main gaps were recognized regarding lack

of learner involvement to improve hazard communication, lack of

employer assessment of employee understanding of training provided,

and lack of studies assessing retention of the material taught and

its application at the worksite (18). In the present study, 30% of the

professional users of chemicals tend to perceive the hazard/risk of

a chemical after instruction by the employer or the shift

supervisor to use PPE. Of note, low PPE compliance persists despite

worker awareness of herbicide exposure risks, potentially as a

result of the influence of the sex dynamics and social culture

(24).

Appropriate work practices and selection and use of

PPE are strongly recommended and measurements at the workplace have

proven the efficacy thereof (25,26).

Nevertheless, use of PPEs is restricted, as observed in the present

study. Farmers that are overexposed to pesticides toxicity do not

use PPE (27). On the other hand,

disposable latex gloves commonly worn by gardeners provide

inadequate protection even for contact with pesticides over a short

period of time (28). Thus, more

emphasis should be given on awareness-raising activities and

increase of the communication of chemicals hazard/risk.

Health care specialists are expected to use PPE more

extensively to protect themselves from infectious diseases and

pathogens (29,30). Nevertheless, these PPEs are not

adequate for protection from chemicals and lack of compliance is

evident regarding PPEs, even among medical technicians (31). Consequently, the observed almost

universal use of PPEs by health care specialists in the present

study is potentially misleading. Regarding compliance of the

medical staff engagement of the personnel in auditing PPE use and

reporting activities may significatnly improve compliance (32).

Health care specialists are often asked to treat

cases that are linked with exposure to different chemicals. In the

present study, 60% of responders were informed regarding the safe

use of chemicals or actions to be undertaken in case of accident.

In the latter situation, the National Poisoning Centre is

considered the reference point for information for the vast

majority of medical doctors. However, the National Poisoning

Centers are less often consulted when emergency poisonings are

treated in the primary or tertiary care centers (33). Data legally required to be declared to

National Poisoning Centers should be harmonized within EU and the

new regulatory framework, which is the primary aim of these legal

frameworks (34,35).

In conclusion, on a national level,

awareness-raising campaigns are imperative (36,37), in

collaboration with trade unions and health care professional

associations, in order to alert professionals regarding the safe

use of chemicals to protect human health and the environment.

References

|

1

|

Shukla KP, Singh NK and Sharma S:

Bioremediation: developments, current practices and perspectives.

Genet Eng Biotechnol J. 3:1–20. 2010.

|

|

2

|

Winder C, Azzi R and Wagner D: The

development of the globally harmonized system (GHS) of

classification and labelling of hazardous chemicals. J Hazard

Mater. 125:29–44. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Morita T and Morikawa K: Expert review for

GHS classification of chemicals on health effects. Ind Health.

49:559–565. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Brekelmans P, de Groot R, Desel H, Mostin

M, Feychting K and Meulenbelt J: Harmonisation of product

notification to Poisons Centres in EU Member States. Clin Toxicol.

51:65–69. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Petróczi A, Naughton DP, Mazanov J,

Holloway A and Bingham J: Performance enhancement with supplements:

Incongruence between rationale and practice. J Int Soc Sports Nutr.

4:192007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Cohen J: Statistical power analysis for

the behavioral sciences. 2nd edition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates;

Hillsdale, NJ: 1988, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Sairat T, Homwuttiwong S, Homwutthiwong K

and Ongwandee M: Investigation of gasoline distributions within

petrol stations: Spatial and seasonal concentrations, sources,

mitigation measures, and occupationally exposed symptoms. Environ

Sci Pollut Res Int. 22:13870–13880. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sirdah MM, Al Laham NA and El Madhoun RA:

Possible health effects of liquefied petroleum gas on workers at

filling and distribution stations of Gaza governorates. EMHJ.

19:289–294. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Moura-Correa MJ, Jacobina AJ, dos Santos

SA, Pinheiro RD, Menezes MA, Tavares AM and Pinto NF: Exposure to

benzene in gas stations in Brazil: Occupational health surveillance

(VISAT) network. Cien Saude Colet. 19:4637–4648. 2014.(In

Portuguese). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Fenga C, Gangemi S, Giambò F, Tsitsimpikou

C, Golokhvast K, Tsatsakis A and Costa C: Low-dose occupational

exposure to benzene and signal transduction pathways involved in

the regulation of cellular response to oxidative stress. Life Sci.

147:67–70. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Karimi A, Eslamizad S, Mostafaee M, Momeni

Z, Ziafati F and Mohammadi S: Restrictive pattern of pulmonary

symptoms among photocopy and printing workers: A retrospective

cohort study. J Res Health Sci. 16:81–84. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Pirela SV, Lu X, Miousse I, Sisler JD,

Qian Y, Guo N, Koturbash I, Castranova V, Thomas T, Godleski J, et

al: Effects of intratracheally instilled laser printer-emitted

engineered nanoparticles in a mouse model: A case study of

toxicological implications from nanomaterials released during

consumer use. NanoImpact. 1:1–8. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sato Y, Kubo S, Takemura S, Sugawara Y,

Tanaka S, Fujikawa M, Arimoto A, Harada K, Sasaki M and Nakanuma Y:

Different carcinogenic process in cholangiocarcinoma cases

epidemically developing among workers of a printing company in

Japan. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 7:4745–4754. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Schyllert C, Rönmark E, Andersson M,

Hedlund U, Lundbäck B, Hedman L and Lindberg A: Occupational

exposure to chemicals drives the increased risk of asthma and

rhinitis observed for exposure to vapours, gas, dust and fumes: A

cross-sectional population-based study. Occup Environ Med.

73:663–669. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Birks L, Casas M, Garcia AM, Alexander J,

Barros H, Bergström A, Bonde JP, Burdorf A, Costet N, Danileviciute

A, et al: Occupational exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals

and birth weight and length of gestation: A European meta-analysis.

Environ Health Perspect. 124:1785–1793. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Singh Z and Chadha P: Textile industry and

occupational cancer. J Occup Med Toxicol. 11:392016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sathar F, Dalvie MA and Rother HA: Review

of the literature on determinants of chemical hazard information

recall among workers and consumers. Int J Environ Res Public

Health. 13:132016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Bouchard C: Literacy and hazard

communication: Ensuring workers understand the information they

receive. J AAOHN. 55:18–25. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Beaufils E, Hommet C, Brault F, Marqué A,

Eudo C, Vierron E, De Toffol B, Constans T and Mondon K: The effect

of age and educational level on the cognitive processes used to

comprehend the meaning of pictograms. Aging Clin Exp Res. 26:61–65.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Martí Fernández F, van der Haar R, López

López JC, Portell M and Torner Solé A: Comprehension of hazard

pictograms of chemical products among cleaning workers. Arch Prev

Riesgos Labor. 18:66–71. 2015.(In Spanish). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Vaillancourt R, Pouliot A, Streitenberger

K, Hyland S and Thabet P: Pictograms for safer medication

management by health care workers. Can J Hosp Pharm. 69:286–293.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ta GC, Mokhtar MB, Mohd Mokhtar HA, Ismail

AB and Abu Yazid MF: Analysis of the comprehensibility of chemical

hazard communication tools at the industrial workplace. Ind Health.

48:835–844. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Klaschka U: The hazard communication of

fragrance allergens must be improved. Integr Environ Assess Manag.

9:358–362. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Andrade-Rivas F and Rother HA: Chemical

exposure reduction: Factors impacting on South African herbicide

sprayer's personal protective equipment compliance and high risk

work practices. Environ Res. 142:34–45. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ceballos DM, Whittaker SG, Lee EG, Roberts

J, Streicher R, Nourian F, Gong W and Broadwater K: Occupational

exposures to new dry cleaning solvents: High-flashpoint

hydrocarbons and butylal. J Occup Environ Hyg. 13:759–769. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Park H, Park HD and Jang JK: Exposure

characteristics of construction painters to organic solvents. Saf

Health Work. 7:63–71. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Quinteros E, Ribó A, Mejía R, López A,

Belteton W, Comandari A, Orantes CM, Pleites EB, Hernández CE and

López DL: Heavy metals and pesticide exposure from agricultural

activities and former agrochemical factory in a Salvadoran rural

community. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 24:1662–1676. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Beránková M, Hojerová J and Peráčková Z:

Estimated exposure of hands inside the protective gloves used by

non-occupational handlers of agricultural pesticides. J Expo Sci

Environ Epidemiol. 27:625–631. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Honda H and Iwata K: Personal protective

equipment and improving compliance among healthcare workers in

high-risk settings. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 29:400–406. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Gralton J, Rawlinson WD and McLaws ML:

Health care worker's perceptions predicts uptake of personal

protective equipment. Am J Infect Control. 41:2–7. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Dukic K, Zoric M, Pozaic P, Starcic J,

Culjak M, Saracevic A and Miler M: How compliant are technicians

with universal safety measures in medical laboratories in

Croatia?-A pilot study. Biochem Med. 25:386–392. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Hennessy KA and Dynan J: Improving

compliance with personal protective equipment use through the model

for improvement and staff champions. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 18:497–500.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Schurter D, Rauber-Lüthy C, Jahns M,

Haberkern M, Kupferschmidt H, Exadaktylos A, Eriksson U and Ceschi

A: Factors that trigger emergency physicians to contact a poison

centre: Findings from a Swiss study. Postgrad Med J. 90:139–143.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Settimi L, Orford R, Davanzo F, Hague C,

Desel H, Pelclova D, Dragelyte G, Mathieu-Nolf M, Adams R and

Duarte-Davidson R: Development of a new categorization system for

pesticides exposure to support harmonized reporting between EU

Member States. Environ Int. 91:332–340. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

de Groot R, Brekelmans P, Desel H and de

Vries I: New legal requirements for submission of product

information to poisons centres in EU member states. Clin Toxicol.

Jun 23–2017.(E-pub ahead of print).

|

|

36

|

Walsh C: CLP activities and control in

Ireland. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 47:165–170. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Pistolese P and Scimonelli L: CLP

Regulation and REACH Regulation: Links, implementation and control

in Italy. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 47:157–164. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|