Introduction

The survival rates of malignant diseases such as

breast cancer, lymphoma and leukemia, are increasing (1), because of the improvements in

therapeutic techniques. However, premature ovarian failure (POF) is

an established long-term adverse effect of chemotherapy in young

women. The POF can lead to infertility and amenorrhea and typical

climacteric symptoms such as palpitations, heat intolerance, hot

flashes, night sweats, irritability, anxiety, depression, sleep

disturbance, decreased libido, hair coarseness, vaginal dryness,

and fatigue (2), which have a

significant impact on the quality of life of young women.

Younger women of childbearing age are confronted

with the risk of infertility by chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea.

Though a number of options to preserve fertility are available,

such as cryopreservation of oocyte, embryo or ovarian tissue,

ovarian transposition and hormonal protection with GnRH analogs

(3), the latter has an edge over

the others since it is less invasive and more convenient.

Animal studies and phase II clinical research have

suggested that GnRHa can lead to temporary ovarian suppression to

preserve ovarian function (4–6).

Recently, several studies have been conducted on the ovarian

function preservation in young women undergoing gonadotoxic

chemotherapy. But the conclusions drawn from these studies are not

unanimous. There were also some reviews and meta-analysis on the

topic, some of which came up with the results that GnRHa can

benefit the ovarian function following chemotherapy (7,8),

while one of the studies produced the conclusion that the benefit

of using GnRHa for fertility preservation in young breast cancer

patients remains uncertain (9). In

the present study, we conducted a meta-analysis to assess the

efficacy of GnRH agonists in protecting the ovaries against

chemotherapy induced damage in premenopausal women with malignant

diseases.

Materials and methods

Data sources and searches

The electronic medical literature databases

including Pubmed, MELINE, Cochrane library, Embase, CNKI and

Wanfang, were explored for available articles on the topic

published till November, 2013 using crosslinking keywords. Articles

in Chinese and English were included. Only randomized controlled

trials (RCTs) were selected. The keywords included fertility,

ovarian failure, ovarian preservation, chemotherapy and GnRHa.

Reference lists were also searched for additional studies. The

experimental groups were prescribed GnRHa while undergoing

chemotherapy and the control group underwent chemotherapy without

GnRHa.

Study selection

Two investigators reviewed each study. The following

inclusion criteria were used to select the studies for our

meta-analysis: i) premenopausal females under the age of 46

undergoing potentially gonadotoxic chemotherapy; ii) a control

group suffering with similar ailments, who were undergoing

chemotherapy but were not given GnRHa; iii) a clear definition to

evaluate ovarian function, such as recurrence of menses, level of

follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). If the study have repeated

publications, we took the one with the most complete data. The

following studies were excluded: i) the studies were not RCTs, such

as case-control design, reviews, letters or case reports; ii)

publications in languages other than Chinese and English; and iii)

studies with a dropout rate of greater than 10%.

Data extraction and quality

assessment

The data were extracted by two reviewers

independently, the terms were as follows: i) the basic information

of author, year of publication, country of the study, study type;

ii) patient population, type of disease, age; iii) GnRHa dose,

timing; iv) chemotherapy regimens; v) definition of premature

ovarian failure; and vi) duration of follow-up.

The methodological quality of each study was

assessed in accordance to the guidelines in the Cochrane reviewers’

handbook (Version 5.1.0) (10).

The following trial features were assessed: i) random sequence

generation; ii) allocation concealment; iii) blinding of

participants and personnel; iv) blinding of outcome assessment; v)

incomplete outcome data; vi) selective reporting; vii) other

sources of bias. The evaluations were categorized as ‘low risk’,

‘high risk’ or ‘unclear risk’ of bias. If all the qualities

criteria were judged low risk, the trial was considered to have low

risk of bias (score A); if one or more qualities criteria were

judged unclear risk, but no one were judged high risk, the trial

was considered to have moderate risk of bias (score B); and if one

or more qualities criteria were judged high risk, the trial was

considered high risk of bias (score C). The publication bias was

also assessed using funnel plot.

Statistical methods

In this meta-analysis, the main outcomes were the

post-chemotherapy ovarian function. All analyses were performed

with Review Manager statistical software (Review Manager 5.1).

Dichotomous data were used to calculate the risk ratio (RR) and 95%

confidence interval, the heterogeneity of the RR were also tested.

In the Q test, it was considered heterogeneous if P<0.1, while

in the I2 statistic, 0 to 40% were deemed not important;

30 to 60% might represent moderate heterogeneity; 50 to 90% might

represent substantial heterogeneity; and 75 to 100% considerable

heterogeneity (10). A

fixed-effect model was used when there was no heterogeneity, when

the heterogeneity present could not be readily explained; a

random-effect model was used. In this meta-analysis, our results

showed P=0.0002, I2=72% indicating that there was

substantial heterogeneity, so a random-effect model was employed.

In the overall results, P<0.05 signifies that GnRHa has a

positive effect in preserving the ovarian function.

The publication bias was also assessed by funnel

plot, which was plotted by Review Manager 5.1. Using RR as abscissa

and standard error of RR napierian logarithm as ordinate, bias was

considered to be under control if the funnel plot was

symmetrical.

Results

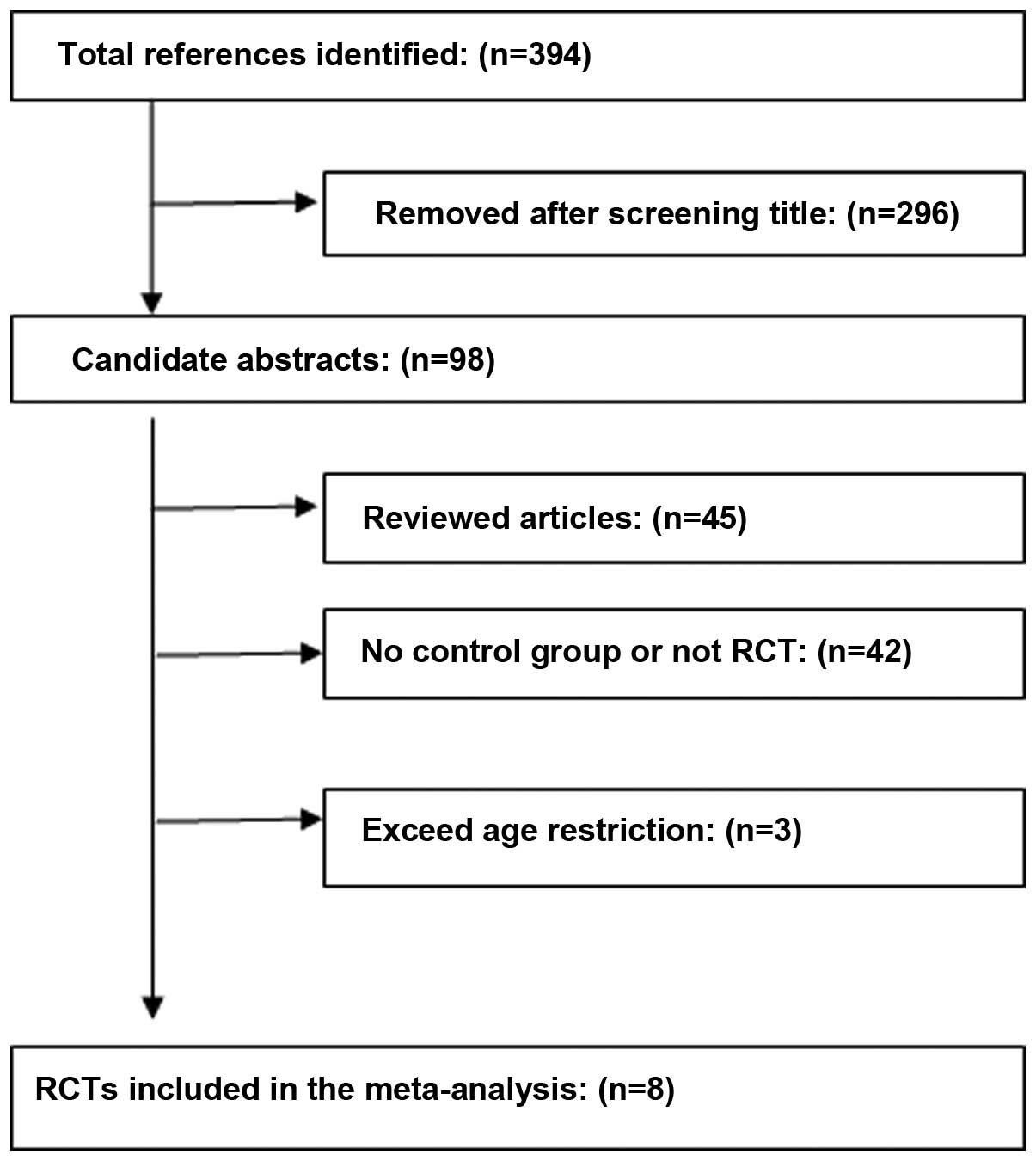

After the databases were thoroughly investigated,

394 articles were selected, then applying the inclusion and

exclusion criteria, eight RCTs composed of 621 patients were

included (Fig. 1) (11–18).

A total of 321 women were treated with GnRHa during their

chemotherapy, while 300 women underwent chemotheray without GnRHa.

The comprehensive characteristics are shown in Table I. Women in five of the trials had

breast cancer, two had lymphoma and one had ovarian malignancy. The

GnRHa used in the RCTs included triptorelin, goserelin, buserelin

and dipherelin. The standard dose was maintained and most of the

GnRHa were administered by subcutaneous or intramuscular injection,

but in one of the cases, it was given intranasally (13). In all trials, the first dose was

administered at least one week prior to chemotherapy in order to

avoid chemotherapy during the expected ovarian flare. We found that

there were certain inconsistencies in the ways POF were defined in

the trials; five (11–14,16,17)

of them were defined as amenorrhea only, while two trials had

considered its association with the follicle-stimulating hormone

(FSH), estrodiol (E2). The types of chemotherapy regimen

used and the number of cycles were also taken into account. Two

trials (11,18) had a follow-up duration less than 12

months, others had maintained follow-up for more than 12 months.

All the trials included were evaluated to have low or moderate risk

of bias according to the methodological quality assessments in the

Cochrane reviewers’ handbook (version 5.1.0) (10).

| Table I.Review of the studies in the

meta-analysis. |

Table I.

Review of the studies in the

meta-analysis.

| Authors/(Refs.)

country, year | Patient

population | Study type | GnRH, dose,

timing | Chemotherapy | Definition of

premature ovarian failure (POF) | Duration of

follow-up | Quality

assessment |

|---|

| Del Mastro et

al (15) Italy, 2011 | Breast cancer age

21–45 (premenopausal) | Parallel, randomized,

open-label trial | Triptorelin, 3.75 mg,

q.4wk, at least 1 week before 1st chemotherapy | Anthracycline-based;

anthracycline plus taxane-based; CMF-based | No menses within 12

months and post-menopausal FSH and E2 | 12 months | A |

| Munster et al

(12) USA, 2012 | Breast cancer age

21–43 | Prospective

randomized | Triptorelin, 3.75 mg,

q.28-30d, 1st injection is between 7 days to 4 weeks before

chemotherapy | AC×4; AC→T×4; FEC×6;

FAC×6 | Amenorrhea | Median follow-up

time: 18 months | A |

| Loverro et al

(14) Italy, 2007 | Hodgkin’s lymphoma

mean age 20–38 | Prospective

randomized | Triptorelin, 3.25 mg

q.mth or triptorelin 11.25 mg q.3mth | 13 patients: ABVD×6,

13 patients: ABVD×5 alternating with C(M)OPP, 3 patients: C(M)OPP

alternative ABV, then DHAP | No menses within 12

months | Mean time: 4.2±2.8

years | B |

| Waxman et al

(13) England, 1987 | Advanced Hodgkin’s

disease age 17–46 | Prospective

randomized | Buserelin 200

μg tid intranasal starting 1 week before chemotherapy | Up to 6 cycles of

MVPP | Amenorrhea | Mean (years): GnRHa,

2.3; no GnRHa, 2.0 | B |

| Elgindy et al

(16) Egypt, 2013 | Breast cancer

(hormone-insensitive) age 18–40 | Randomized

controlled | Triprelin 3.75mg

q.4wk, the 1st injection was 1 week before chemotherapy | FAC×6 | No menses within 12

months | 12 months | A |

| Gerber et al

(17) Germany, 2011 | Breast cancer

(hormone-insensitive) age 18–45 | Randomized

open-label, controlled multicenter trial | Goserelin 3.6 mg

q.4k, 1st injection at least 2 weeks before chemotherapy |

Anthracycline/cyclophosphamide-based

chemotherapy | No regular

menses | 24 months | B |

| Badawy et al

(11) Egypt, 2009 | Breast cancer age

18–40 | Randomized, control

trial | Goserelin 3.6 mg

q.4wk, for 6 months | FAC×6 | Early cessation of

menstruation, ovulation and increased serum FSH level | 8 months | B |

| Gilani et al

(18) Iran, 2007 | Ovarian malignancy

age 12–40 (post-menarche) | Prospective,

randomized, controlled | Diphereline 3.75 mg

q.28d, 1st injection 7–10 days before chemotherapy | VAC, BEP, TC, CP, for

less than 6 months | Early, permanent

cessation of menstruation, FSH ≤20 mlu/ml | 6 months | B |

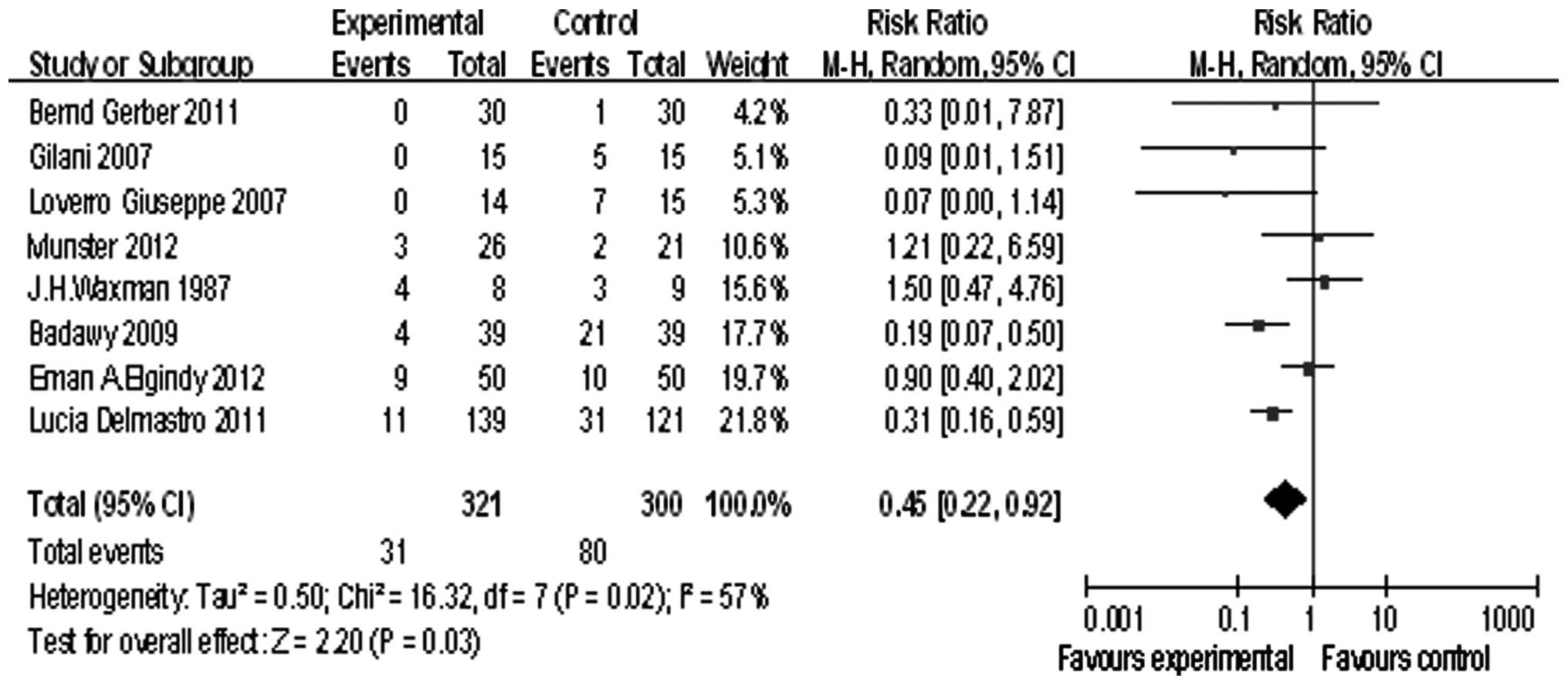

Eight studies reported POF, we tested the

heterogeneity of the RR [τ2=0. 5; χ2=16.32,

df=7 (P=0.02); I2=57%], and because of the heterogeneity

of the RR, a randomized model was used. The summary RR was 0.45,

and the 95% confidence interval was (0.22, 0.92), P=0.03 (Fig. 2). This demonstrated that GnRHa

exerted its positive effects in preserving the ovarian function by

preventing POF.

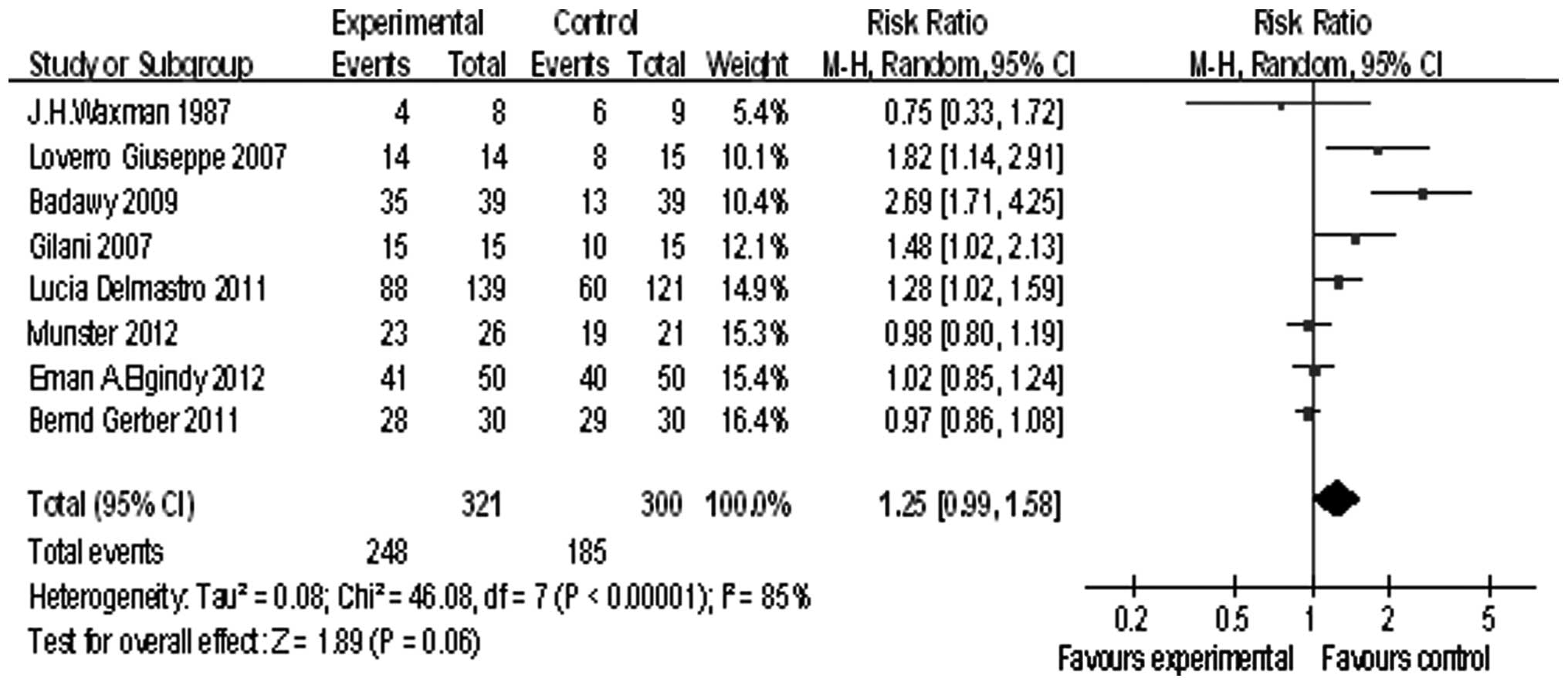

Eight studies reported the rate of menstruation

recovery, the summary RR was 1.25, and the 95% confidence interval

was (0.99, 1.58), P=0.06 (Fig. 3).

This result showed GnRHa can improve the menstruation recovery

rate.

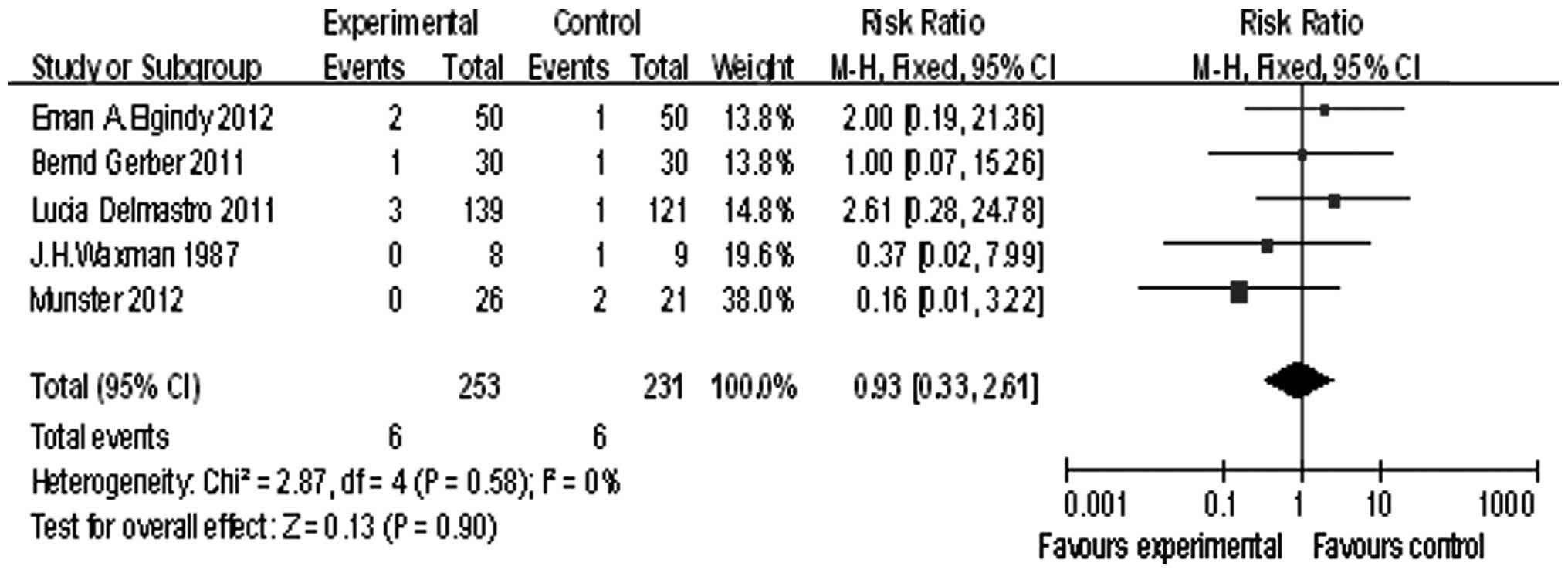

Five of the studies reported pregnancy, the summary

RR was 0.93, and the 95% confidence interval was (0.33, 2.61), P=

0.90 (Fig. 4). The pregnancy rate

showed no significant difference between the GnRHa group and the

chemotherapy alone group.

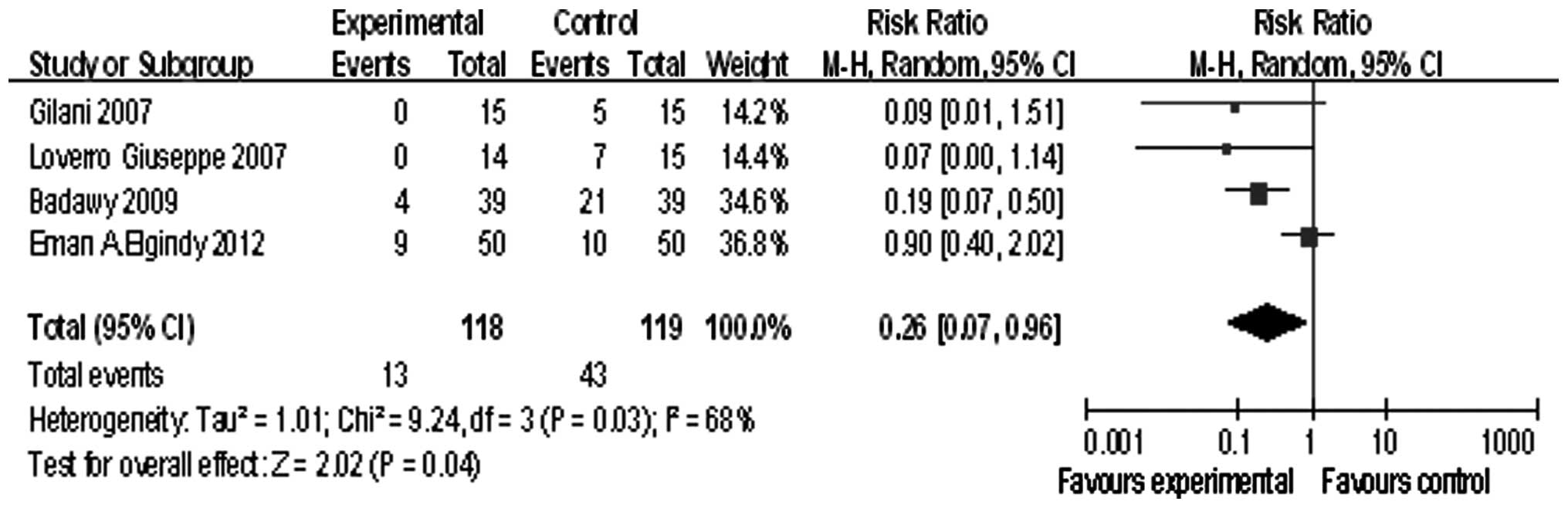

Four studies involved patients younger than 40

years, the summary RR was 0.26, and the 95% confidence interval was

(0.07, 0.96), P=0.04 (Fig. 5).

Publication bias was assessed by the use of a funnel

plot, the plot was basically symmetrical and the distribution of

most of the points was in an inverted funnel manner.

Discussion

The mechanism of action by which GnRHa preserves

ovarian function is not clear, but may include: i) the interruption

of FSH secretion and inhibition of follicles from entering the

growing stage; ii) reduction of ovarian perfusion; iii) protection

of ovarian germline stem cells directly; and iv) upregulation of

phingosine-I-phosphate (19).

Based on the meta-analysis we conducted, there was

evidence that GnRHa could preserve the ovarian function following

chemotherapy in young pre-menpausal women. POF has been referred to

as a form of hypogonadism that manifests as premature menopause or

development of amenorrhea due to cessation of ovarian function,

only two trials considered the level of the FSH, E2.

However, POF is rather an ovarian insufficiency than ovarian

failure since the women with POF have been reported to conceive

despite limited ovarian function. Ravdin et al showed that

young breast cancer patients retain their ovarian function

following chemotherapy despite the absence of menstruation

(21). However, infertility

typically proceeds to menopause by within ten years (25). Thus we consider that the former

definition has certain limitation since amenorrhea is not the best

standard for determination of fertility. The diagnosis is based on

detection of elevated FSH that is approaching menopausal level

(usually above 40 IU/l) at least two measurements conducted a few

weeks apart (20). Apart from FSH,

other hormonal indicators such as anti-mullerian hormone (AMH),

estradiol (E2), inhibin-A and B have also been

implicated with the accurate determination of ovarian functions.

Anderson et al came up with an effective method for

determining the residual ovarian function after chemotherapy which

involved the measurement of AMH along with ultrasound-guided antral

follicle count (22).

Among the trials in our analysis, four (11,14,16,18)

were conducted on patients younger than 40 years. Because of the

limited data, we could not estimate the precise function of GnRHa

in this patient group. This leads to a bias in our analysis since

ovarian function has a natural tendency to decline along with age.

Also there is a possibility of data contamination due to the

involvement of the environmental factors. The data analyzed have a

wide geographical variation thus we can not exclude the possibility

of a varied susceptibility of women towards POF due to the

environment they were exposed to.

Tamoxifen is a known independent risk factor which

can affect menstrual cycles. One study (23) showed that the rate of amenorrhea in

patients treated with goserelin alone was 64% compared to 93% in

patients treated with goserelin combined with tamoxifen. However,

of the five trials including patients with breast cancer, there was

a lack of control for confounding effects of tamoxifen.

Only three of the trials were followed up for more

than 2 years. For those women who recovered menstruation, there is

an additional long-term risk of POF (24). The long-term POF reports do not

exist; and one-year follow-up can not evaluate the ability of

fertility well. Thus, long-term follow-up is needed.

The first injection of the GnRHa was generally one

or two weeks before chemotherapy, only two trials (16,17)

proved ovarian suppression before chemotherapy. Ovarian suppression

was not confirmed on chemotherapy administration and ovaries could

be in ‘flare-up’ interval. In this condition, the GnRHa might not

perform well.

Some heterogeneity existed in the trials we

analyzed, which presumably creates a potential bias on the results

we obtained. For instance the heterogeneity in the chemotherapy

regimen could affect our results. Similarly the variation in the

length of follow-up duration also has certain impact in determining

the actual results. On the contrary, one of the strength of our

study was the inclusion of bilingual literatures in English and

Chinese. The study criteria were determined carefully and the

methodological quality of each trial included in this analysis was

assessed following the standard protocol in the Cochrane reviewers’

handbook.

In this meta-analysis, we have deduced the

beneficial role of GnRHa in preserving the ovarian function of the

young women undergoing chemotherapy, but the ability to preserve

fertility was not proved. However, more well-designed trials with

appropriate age limitation (<40 years old) and a more sensitive

marker of ovarian reserve are needed before it is established as a

standard therapy.

Acknowledgements

The study was conducted at Qilu

Hospital, Shandong Medical University and was supported by the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (81072121, 81372808,

JJ and 81173614, LQT) and the science and technology developing

planning (2012G0021823, JJ), (2011GSF12122, ZX) and also by science

and technology developing planning of Jinan (201303035). We would

like to acknowledge Mr Binglin Lv for his support for statistical

analysis.

References

|

1.

|

Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results

(SEER) Web site: Available online: http://www.seer.cancer.govApril2010

based on the November 2009 submission.

|

|

2.

|

Beck-Peccoz P and Persani L: Premature

ovarian failure. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 1:92006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3.

|

Sonmezer M and Oktay K: Fertility

preservation in female patients. Hum Reprod Update. 10:251–266.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4.

|

Bokser L, Szende B and Schally AV:

Protective effects of D-Trp6-luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone

microcapsules against cyclophosphamide-induced gonadotoxicity in

female rats. Br J Cancer. 61:861–865. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5.

|

Ataya K, Rao LV, Lawrence E and Kimmel R:

Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist inhibits

cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian follicular depeletion in rhesus

monkeys. Biol Reprod. 52:365–372. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6.

|

Del Mastro L, Catzeddu T, Boni L, et al:

Prevention of chemotherapy-induced menopause by temporary ovarian

suppression with goserelin in young, early breast cancer patients.

Ann Oncol. 17:74–78. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Clowse ME, Behera MA, Anders CK, Copland

S, et al: Ovarian preservation by GnRH agonists during

chemotherapy: A meta-analysis. J Women’s Health. 18:311–319.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Yang B, Shi W, Yang J, Liu H, Zhao H, et

al: Concurrent treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone

agonists for chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage in premenopausal

women with breast cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled

trials. Breast. 22:150–157. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9.

|

Turner NH, Partridge A, Sanna G, Di Leo A

and Biganzoli L: Utility of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists

forfertility preservation in young breast cancer patients: the

benefit remains uncertain. Ann Oncol. 24:2224–2235. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Higgins JPT and Green S: Cochrane Handbook

for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cohran

Collaboration (updated March 2011).

|

|

11.

|

Badawy A, Elnashar A, El-Ashry M and

Shahat M: Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists for prevention of

chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage: prospective randomized study.

Fertil Steril. 91:694–697. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Munster PN, Moore AP, et al: Randomized

trial using gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist triptorelin for

the preservation of ovarian function during (neo)adjuvant

chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 30:533–538. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13.

|

Waxman JH, Ahmed R, Smith D, Wrigley PEM,

et al: Failure to preserve fertility in patients with Hodgkin’s

disease. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 19:159–162. 1987.

|

|

14.

|

Loverro G, Guarini A, Di Naro E, et al:

Ovarian function after cancer treatment in young women affected by

Hodgkin disease (HD). Hematology. 12:141–147. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Del Mastro L, Boni L, Michelotti A,

Gamucci T, Olmeo N, et al: Effect of the gonadotropin-releasing

hormone analogue triptorelin on the occurrence of

chemotherapy-induced early menopause in premenopausal women with

breast cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 306:269–276. 2011.

|

|

16.

|

Elgindy EA, El-Haieg DO, Khorshid OM, et

al: Gonadatrophin suppression to prevent chemotherapy-induced

ovarian damage: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol.

121:78–86. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Gerber B, von Minlkwitz G, Stehle H,

Reimer T, et al: Effect of luteining hormone-releasing hormone

agonist on ovarian function after modern adjuvant breast cancer

therapy: The GBG 37 ZORO study. J Clin Oncol. 29:2334–2341. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Gilani MM, Hasanzadeh M, Ghaemmaghami F,

et al: Ovarian preservation with gonadotrop in releasing hormone

analog during chemotherapy. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 3:79–83. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19.

|

Blumenfeld Z: How to preserve fertility in

young women exposed to chemotherapy? The role of GnRH agonist

cotreatment in addition to cryopreservation of embryo, oocytes, or

ovaries. Oncologist. 12:1044–1054. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Goswami D and Conway GS: Premature ovarian

failure. Hum Reprod Update. 11:391–410. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21.

|

Ravdin PM, Fritz NF, Tormey DC and Jordan

VC: Endocrine status of premenopausal node-positive breast cancer

patients following adjuvant chemotherapy and long-term tamoxifen.

Cancer Res. 48:1026–1029. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22.

|

Anderson RA, Themmen AP, Al-Qahtani A,

Groome NP and Cameron DA: The effects of chemotherapy and long-term

gonadotropin suppression on the ovarian reserve in premenopausal

women with breast cancer. Hum Reprod. 21:2583–2592. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Sverrisdottir A, Nystedt M, Johansson H

and Fornander T: Adjuvant goserelin and ovarian preservation in

chemotherapytreated patients with early breast cancer: results from

a randomized trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 117:561–567. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Partridge A, Gelber S, Gerber RD and

Castiglione-Certsch M: Age of menopause among women who remain

premenopausal following treatment for early breast cancer:

long-term results from International Breast Cancer Study Group

Trials V and VI. Eur J Cancer. 43:1646–1653. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25.

|

Te Velde ER and Pearson PL: The

variability of female reproductive ageing. Hum Reprod Upadate.

8:141–154. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|