Introduction

Cancer is a major public health problem worldwide.

Epidemiologic and animal studies have demonstrated an association

with the inclusion of vegetables and fruits containing

chemopreventive compounds in the diet and a reduced risk of cancer

development (1,2). Our laboratory has spent over 20 years

screening vegetables and fruits for natural phytochem-ical products

that inhibit DNA metabolic enzymes, primarily mammalian DNA

polymerases (Pols) and human DNA topoi-somerases (Topos).

Pols (DNA-dependent DNA polymerase, EC 2.7.7.7)

catalyze the addition of deoxyribonucleotides to the 3′-hydroxyl

terminus of primed double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) molecules (3). The human genome encodes at least 15

Pols that function in cellular DNA synthesis (4,5).

Eukaryotic cells contain three replicative Pols (α, δ and ɛ), a

single mitochon-drial Pol (γ), and at least 11 non-replicative Pols

[β, ζ, η, θ, ι, κ, λ, μ, ν, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase

(TdT), and REV1] (6,7). Pol structure is highly conserved, and

the catalytic subunit shows little variance among species. Sequence

homology classifies eukaryotic Pols into four main families: A, B,

X and Y (6). Family A includes

mitochondrial Pol γ as well as Pols θ and ν; family B includes the

three replicative Pols α, δ and ɛ and also Pol ζ; family X

comprises Pols β, λ and μ, as well as TdT; and family Y includes

Pols η, ι and κ, in addition to REV1 (7).

Topos are nuclear enzymes that alter DNA topology

and are required for the replication, transcription, recombination

and segregation of daughter chromosomes (8). Eukaryotic cells have two types of

Topos, I and II. Topo I catalyzes the passage of a DNA strand

through a transient single-strand break in the absence of any

high-energy cofactor. In contrast, Topo II catalyzes the passage of

dsDNA through a transient double-strand break in the presence of

ATP.

Selective inhibitors of Pols and Topos can suppress

the proliferation of normal and cancerous human cells or exhibit

cytotoxic effects (9–11). These inhibitors are potentially

useful as anticancer, antiviral, antiparasitic or antipregnancy

agents. In screening for these enzyme inhibitors in the ethanol

extracts of various food materials, we found that the extract of

mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) from various parts of

the fruit, such as the fruit, pericarp, leaves and rind, strongly

inhibited the activities of mammalian Pols. We purified major

components and identified eight xanthones by NMR and mass spectra

analysis.

The mangosteen tree has been cultivated for

centuries in tropical areas of the world. The tree is presumed to

have originated in Southeast Asia or Indonesia and has largely

remained indigenous to Malay Peninsula, Myanmar, Thailand,

Cambodia, Vietnam and the Moluccas (12). The white, inner pulp of the

mangosteen fruit is highly praised as one of the best tasting of

all tropical fruits. This fruit has been dubbed the ‘queen of

fruit’ in its native Thailand. The mangosteen rind, leaves and bark

have been used as folk medicine for thousands of years (13). The thick mangosteen rind has been

and is used for treating catarrh, cystitis, diarrhea, dysentery,

eczema, fever, intestinal ailments, pruritis and other skin

ailments. The mangosteen leaves are also used by some natives in

teas and for diarrhea, dysentery, fever and thrush. Concentrates of

mangosteen bark are used for genito-urinary afflictions and

stomatosis.

Over 200 xanthones are currently known to exist in

nature and ~50 of them are found in the mangosteen. The xanthones

from mangosteen are gaining more interest because of their

remarkable pharmacological effects, including not only anticancer

activities (14,15), but also analgesic (16), antioxidant (17), anti-inflammatory (18), anti-allergy (19), antibacterial (20), anti-tuberculosis (21), antifungal (22), antiviral (23), cardioprotective (24), neuroprotective (25) and immunomodulation (26) effects. However, the underlying

molecular mechanisms of these compounds and their effects on the

activities of DNA metabolic enzymes have not been reported.

Therefore, the present study focused on the isolated

eight xanthones from mangosteen and investigated these compounds

for their inhibitory effects in vitro on mammalian Pol and

human Topo activities.

Materials and methods

Materials

A chemically synthesized DNA template, poly(dA), and

calf thymus DNA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. and a

customized oligo(dT)18 DNA primer was produced by

Sigma-Aldrich Japan K.K. (Hokkaido, Japan). Radioactive nucleotide

[3H]-labeled 2′-deoxythymidine-5′-triphosphate (dTTP; 43

Ci/mmol) was obtained from Moravek Biochemicals Inc. (Brea, CA,

USA). Supercoiled pHOT-1 DNA was obtained from TopoGEN Inc. (Port

Orange, FL, USA). All other reagents were analytical grade from

Nacalai Tesque Inc. (Kyoto, Japan).

Isolation of xanthones from

mangosteen

Some xanthone compounds were isolated from the

leaves of mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.), which were

collected in Vietnam and provided by Dr Duy Hoang Le (Kobe

Pharmaceutical University). The chemical structures were determined

by spectroscopic analyses and comparison with reported data

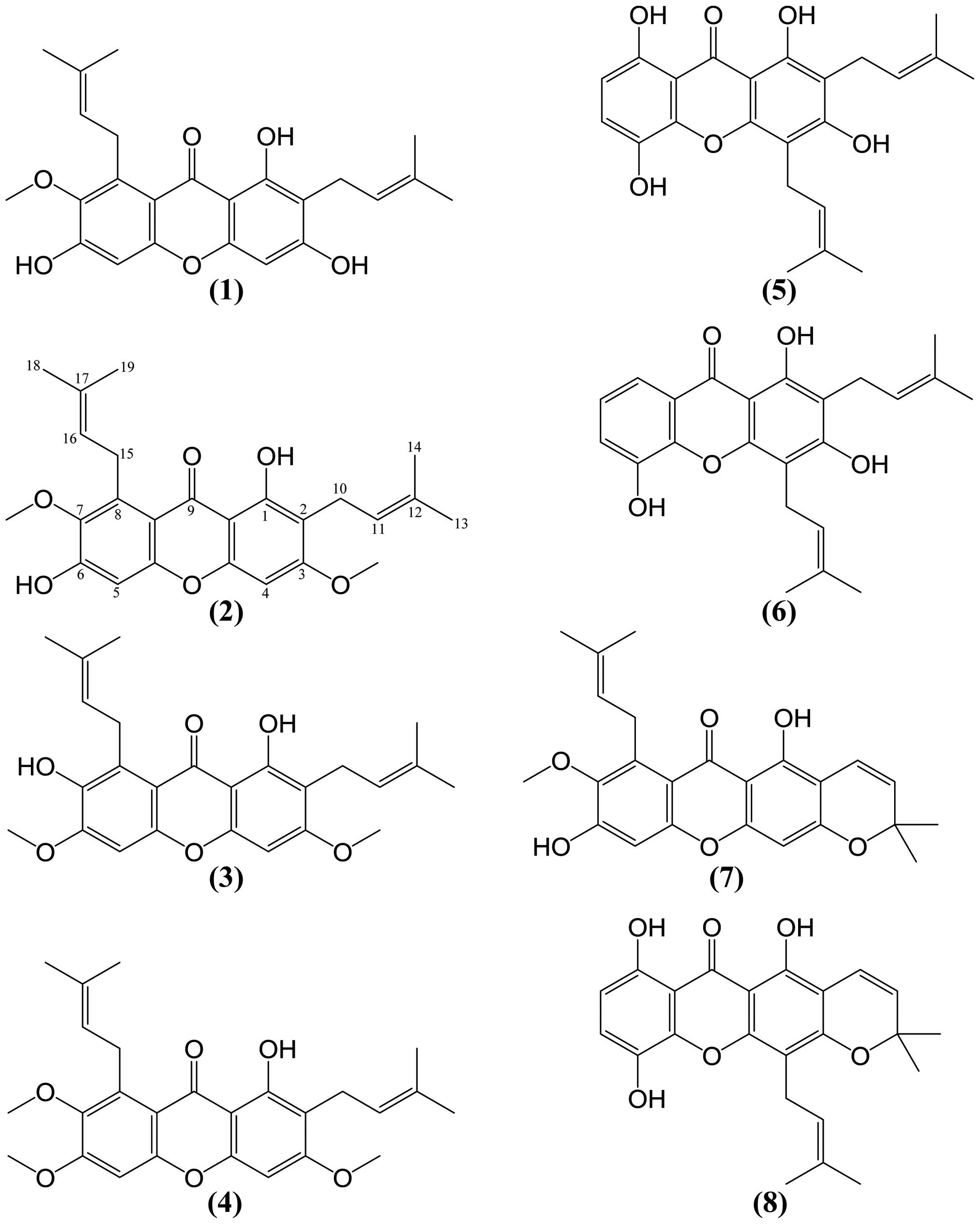

(27–30). The identified eight compounds are

α-mangostin (1), β-mangostin (2),

3,6-di-O-methyl-γ-mangostin (3), fuscax-anthone C

(4), gartanin (5), 8-deoxygartanin (6),

mangostanin (7) and morusignin I (8) (Fig. 1).

Enzymes

Pol α was purified from calf thymus by

immunoaffinity column chromatography, as described by Tamai et

al (31). Recombinant rat Pol

β was purified from Escherichia coli JMpβ5, as described by

Date et al (32). The human

Pol γ catalytic gene was cloned into pFastBac, with the

histidine-tagged enzyme expressed using the BAC-TO-BAC HT

Baculovirus Expression System according to the supplier's

instructions (Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA), and

purified using ProBound resin (Invitrogen Japan K.K, Tokyo, Japan)

(33). Human Pols δ and ɛ were

purified by nuclear fractionation of human peripheral blood cancer

cells (Molt-4) using the second subunit of Pols δ and ɛ-conjugated

affinity column chromatography, respectively (34). A truncated form of human Pol η

(residues 1–511) tagged with His6 at the C-terminus was

expressed in E. coli and purified as described by Kusumoto

et al (35). Recombinant

mouse Pol ι tagged with His6 at the C-terminus was

expressed and purified by Ni-NTA column chromatography (36). A truncated form of Pol κ (residues

1–560) with a His6-tag at the C-terminus was expressed

in E. coli and purified as described by Ohashi et al

(37). Recombinant human His-Pol λ

was expressed and purified according to a method described by

Shimazaki et al (38). Calf

TdT, T7 RNA polymerase and T4 polynucleotide kinase were purchased

from Takara Bio Inc. (Kyoto, Japan). Purified human placenta Topos

I and II were purchased from TopoGEN Inc. Bovine pancreas

deoxyribonuclease I was obtained from Stratagene Cloning Systems

(La Jolla, CA, USA).

Measurement of Pol activity

The reaction mixtures for calf Pol α and rat Pol β

have been described (39,40). Those for human Pol γ and for human

Pols δ and ɛ were as described by Umeda et al (33) and Ogawa et al (41), respectively. The reaction mixtures

for mammalian Pols η, ι and κ were the same as that for calf Pol α,

and the reaction mixture for human Pol λ was the same as for rat

Pol β. For Pols, poly(dA)/oligo(dT)18 (A/T=2/1) and

tritium-labeled 2′-deoxythymidine 5′-triphos-phate

([3H]-dTTP) were used as the DNA template-primer and

nucleotide [i.e., 2′-deoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphate (dNTP)]

substrates, respectively. For the TdT reactions,

oligo(dT)18 (3′-OH) and dTTP were used as the DNA primer

substrate and nucleotide substrate, respectively.

The eight isolated xanthone compounds were dissolved

in distilled dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at various concentrations

and sonicated for 30 sec. Aliquots of 4 μl of sonicated samples

were mixed with 16 μl of each enzyme (final amount, 0.05 units) in

50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), containing 1 mM dithiothreitol, 50%

glycerol and 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and

kept at 0ºC for 10 min. These inhibitor-enzyme mixtures (8 μl) were

added to 16 μl of each of the enzyme standard reaction mixtures and

incubation carried out at 37ºC for 60 min. Activity without the

inhibitor was considered 100% and the remaining activity at each

inhibitor concentration was determined relative to this value. One

unit of Pol activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that

catalyzed incorporation of 1 nmol dNTP [measured using

[3H]-dTTP] into synthetic DNA template-primers in 60 min

at 37ºC under the normal reaction conditions for each enzyme

(39,40).

Measurement of Topo activity

Purified human placental Topos I and II were

purchased from TopoGen Inc. The catalytic activity of Topo I was

determined by detecting supercoiled plasmid DNA (Form I) in its

nicked form (Form II) (42). The

Topo I reaction was performed in a 20-μl reaction mixture that

contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), pHOT-1 DNA (250 ng), 1 mM EDTA,

150 mM NaCl, 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.l mM spermidine, 5%

glycerol, 2 μl of one of the eight isolated xanthone compounds

dissolved in DMSO, and 2 units of Topo I. Topo II catalytic

activity was analyzed in the same manner, except the reaction

mixture contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 120 mM KCl, 10 mM

MgCl2, 0.5 mM ATP, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, supercoiled

pHOT-1 DNA (250 ng), and 2 units of Topo II (42). Reaction mixtures were incubated at

37ºC for 30 min, followed by digestion with 1% sodium dodecyl

sulfate (SDS) and 1 mg/ml proteinase K. After digestion, 2 μl

loading buffer (5% sarkosyl, 0.0025% bromophenol blue and 25%

glycerol) was added. The same procedure was followed for mobility

shift assay assessment of enzyme DNA binding, except SDS

denaturation and proteinase K digestion were omitted. Reaction

mixtures were subjected to 1% agarose gel electrophoresis in

Tris/borate/EDTA buffer. Agarose gels were stained with ethidium

bromide (EtBr) and DNA band shifts from Form I to Form II were

detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system

(Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Zero-D scan

(Version 1.0, M & S Instruments Trading Inc., Osaka, Japan) was

used for densitometric quantitation.

Other enzyme assays

The activities of T7 RNA polymerase, T4

polynucleotide kinase and bovine deoxyribonuclease I were measured

using standard assays according to the manufacturer's

specifications as described by Nakayama and Saneyoshi (43), Soltis and Uhlenbeck (44) and Lu and Sakaguchi (45), respectively.

Thermal transition of DNA

Thermal transition profiles of dsDNA to

single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) with or without α-mangostin were

obtained with a spectrophotometer (UV-2500; Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto,

Japan) equipped with a thermoelectric cell holder was used as

previously described (46). Calf

thymus DNA (6 μg/ml) was dissolved in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer

(pH 7.0) containing 1% DMSO. The solution temperature was

equilibrated at 75ºC for 10 min, and then increased by 1ºC at 2-min

intervals for each measurement point. Any change in the absorbance

(260 nm) of the test compound itself at each temperature point was

automatically subtracted from that of DNA plus the compound in the

spectrophotometer.

Cell culture and measurement of cancer

cell viability

The human cervical cancer cell line HeLa was

obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas,

VA, USA). HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's

medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml

penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were cultured at 37ºC

in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2/95% air. For

assessment of cell growth, cells were plated at 2×103

cells/well in 96-well microplates, cultured for 12 h and various

concentrations of the eight isolated xanthone compounds added. The

compounds were dissolved in DMSO to produce 10-mM stock solutions,

which were further diluted to appropriate final concentrations with

growth medium containing 0.5% DMSO immediately prior to use. Cell

viability was determined by the WST-1 assay following 24-h

incubation (47).

Cell cycle analysis

Cellular DNA content for cell cycle analysis was

determined as follows: aliquots of 3×105 HeLa cells were

added to a 35-mm dish and incubated with the medium that contained

the test compound for 0 to 24 h. Cells were then washed with

ice-cold PBS three times, fixed with 70% (v/v) ethanol, and stored

at −20ºC. DNA was stained with a PI

(3,8-diamino-5-[3-(diethylmethylammonio)propyl]-6-phenyl-phenanthridinium

diiodide) staining solution for at least 10 min at room temperature

in the dark. Fluorescence intensity was measured using a BD

FACSCalibur flow cytometer in combination with CellQuest software

(Becton-Dickinson Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Measurement of caspase-3 activity

The enzymatic activity of caspase-3 was measured

using EnzChek Caspase-3 Assay Kit #2 (Life Technologies Japan Co.,

Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), according to the instruction manual. HeLa

cells (1×106) after inducing apoptosis with test

compound were washed with PBS and lysed. Then, the caspase-3

activity in the extracts was determined with a fluorometric assay.

The fluorescent product of the substrate Z-DEVD-Rhodamine 110

generated by caspase-3 in the cell extract was detected in a

fluorescent microplate reader (SH-9000 Lab; Hitachi

High-Technologies Corp., Tokyo, Japan) using an excitation of 496

nm and emission of 520 nm. To determine the background fluorescence

of the substrate, test compound without the Z-DEVD-R110 substrate

for negative controls, and mixture of activity buffer and

Z-DEVD-R110 substrate for only substrate controls were also

executed.

4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)

staining

Aliquots of 2.5×104 HeLa cells were

plated in each well of an 8-well chamber slide (Thermo Fisher

Scientific K.K., Tokyo, Japan). Then, the cells were incubated with

or without the test compound (27.2 and 54.4 μM) for 12 and 24 h at

37ºC with 5% CO2. After washed with PBS twice, the cells

were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) for 15 min. Then, the

cells were stained with DAPI for 1 min, and the percentage of

apoptotic cells was counted under a fluorescence microscope

(Olympus IX70; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as the mean value ± the

standard deviation (SD) of the mean of at least three independent

determinations for each experiment. Statistical significance

between each experimental group was analyzed using Student's

t-test, and a probability level of 0.01 and 0.05 was used as the

criterion of significance.

Results

Effect of the isolated xanthone compounds

1-8 on the activities of mammalian Pols

Selective inhibitors of mammalian Pols have been

investigated with the goal to develop chemothera-peutic drugs for

anticancer, antivirus and anti-inflammation treatments (48). In our ongoing screening for natural

inhibitors of mammalian Pols, we found that the extract of

mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) had inhibitory activity

against mammalian Pols. The isolated xanthone compounds 1-8

(Fig. 1) were selected and

prepared for this study.

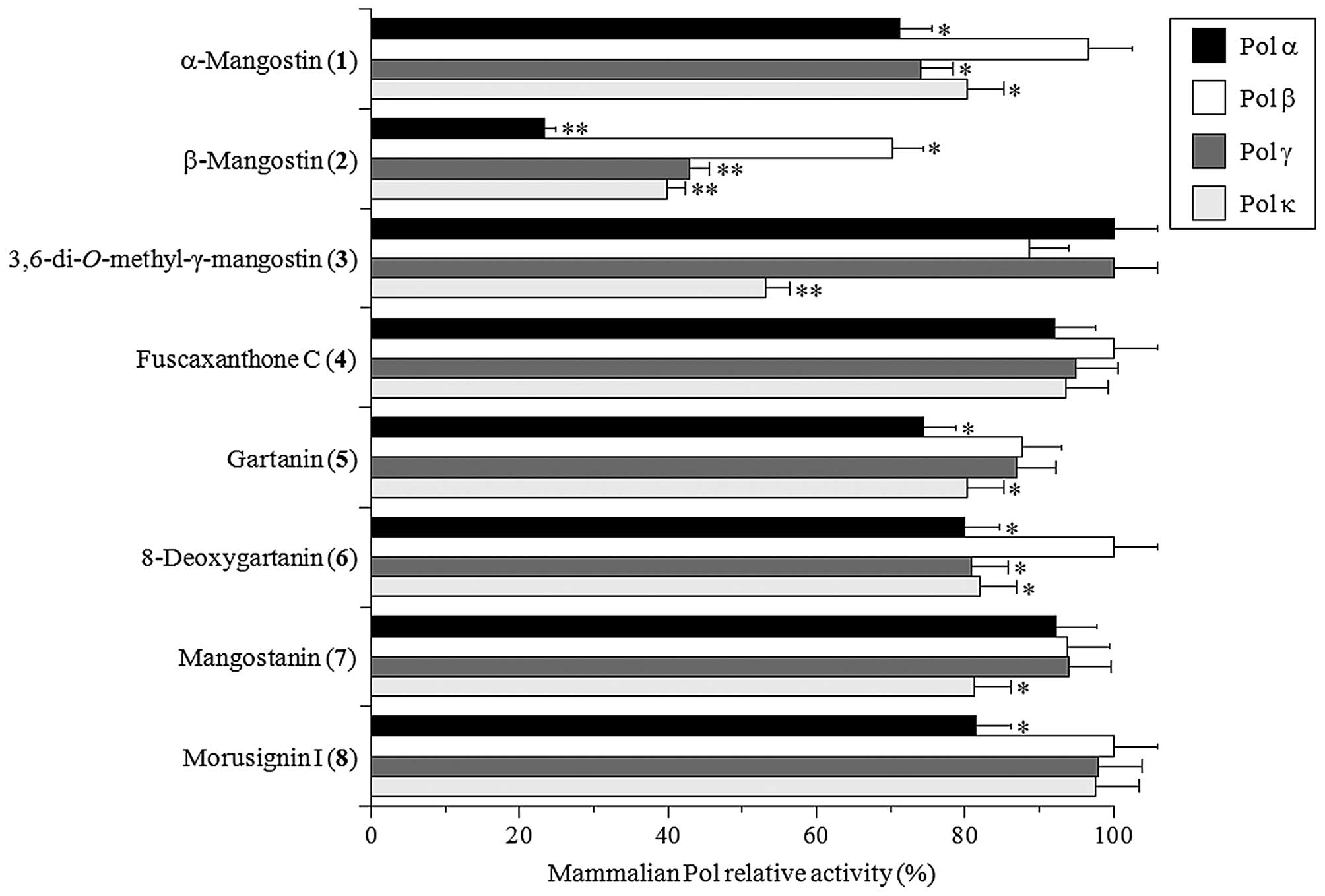

The inhibitory activity of each compound toward

mammalian Pols was investigated using calf Pol α, rat Pol β, and

human Pols γ and κ. For mammalian Pols, Pols α, β, γ and κ were

used as the representatives of Pol families B, X, A and Y,

respectively (6,7). Assessment of the relative activity of

each Pol at a set concentration (10 μM) of the eight test compounds

showed that β-mangostin (2) was the strongest inhibitor of

these Pol species among the compounds tested (Fig. 2). In particular, this compound

showed the strongest inhibitory activity against Pol α among the

four mammalian Pols. α-Mangostin (1) and

3,6-di-O-methyl-γ-mangostin (3) slightly inhibited

Pols α, γ, and κ activities and Pol κ activity, respectively. These

results suggested that the common backbone structure with prenyl

groups at C-2 and C-8 of compounds 1-3 might be important

for Pol inhibition, and both the hydroxyl group at C-6 and the

methoxy group at C-3, which are present in β-mangostin (2),

must be much more important for Pol inhibitory activity.

Effect of the isolated xanthone compounds

1-8 on the activities of human Topos I and II

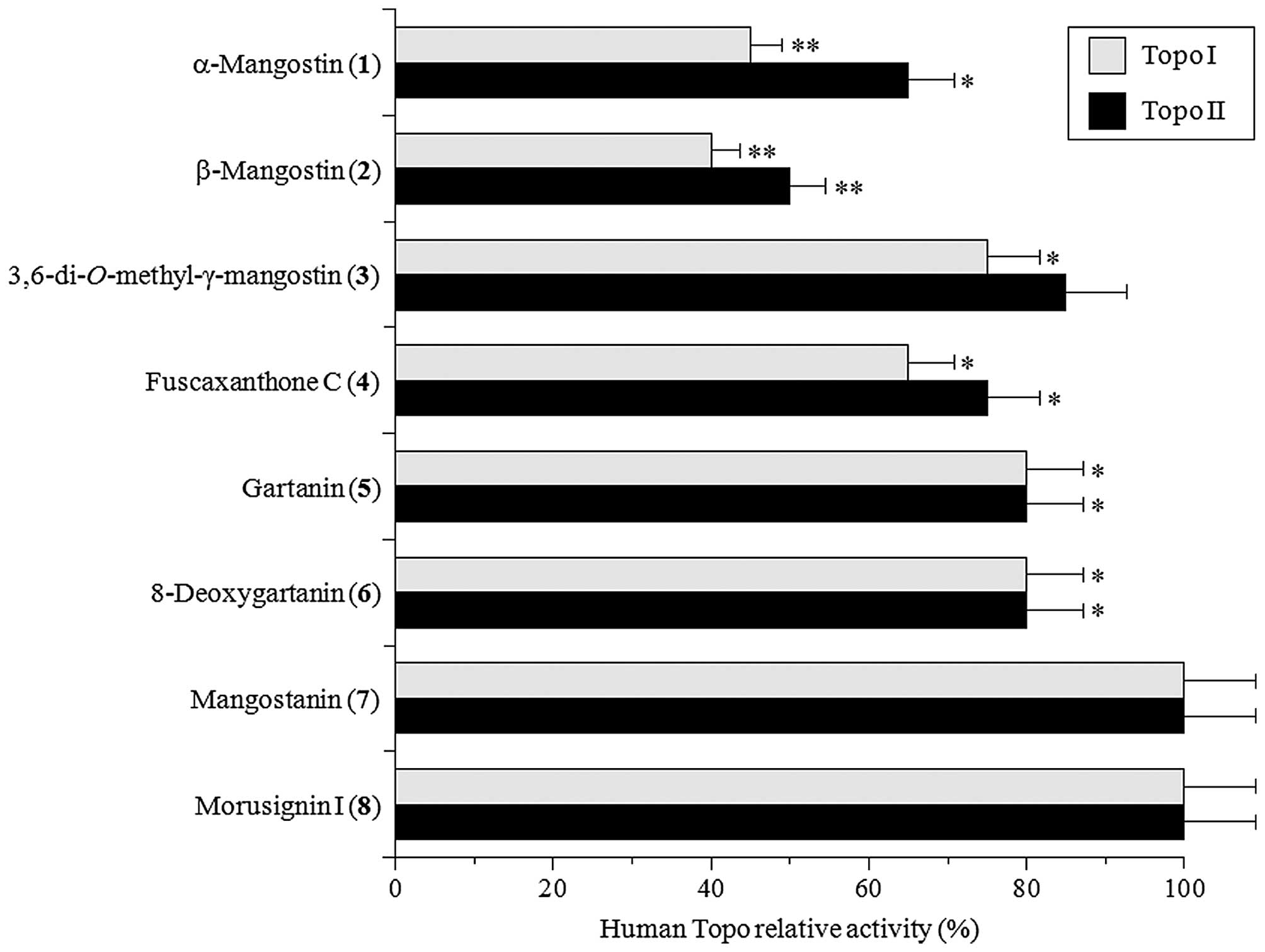

Next, the inhibitory effects of the eight isolated

xanthones (10 μM each) were examined against human Topos I and II,

which have ssDNA and dsDNA nicking activity, respectively (8). β-Mangostin (2) was the

strongest inhibitor of both Topos I and II, and the inhibitory

effect of this compound on Topo II was more potent than that on

Topo I (Fig. 3). In contrast,

mangostanin (7) and morusignin I (8) did not

influence the activities of these Topos. Topo inhibition could be

ranked as β-mangostin (2) >α-mangostin (1)

>3,6-di-O-methyl-γ-mangostin (3) = fuscaxanthone C

(4) = gartanin (5) = 8-deoxygartanin (6)

>mangostanin (7) = morusignin I (8). Since

β-mangostin (2) showed the strongest inhibitory activities

on both mammalian Pols and human Topos, we focused on this compound

in the subsequent study.

Effects of β-mangostin on the activities

of various mammalian Pols and other DNA metabolic enzymes

Evaluation of the inhibition of DNA metabolic enzyme

activities in vitro by β-mangostin revealed that this

compound inhibited the activities of all eleven mammalian Pols

tested from all four families. Calf Pol α and calf TdT were the

strongest and weakest inhibited, respectively, with 50% inhibitory

concentration (IC50) values of 6.4 and 39.6 μM,

respectively (Table I). The

inhibition by β-mangostin against mammalian Pol families could be

ranked as B-family Pols >A-family Pol >Y-family Pols >

X-family Pols. By comparison, the IC50 values of

aphidicolin, a known eukaryotic DNA replicative Pols α, δ and ɛ

inhibitor, were 20, 13 and 16 μM, respectively (49), showing that the Pol inhibitory

activity of β-mangostin was >1.5-fold higher than that of

aphidicolin. β-Mangostin inhibited the activity of human Topos I

and II with IC50 values of 10.0 and 8.5 μM,

respectively. Topotecan and doxorubicin, which are Topo I and Topo

II inhibitors, respectively, also inhibited the nicking activities

of Topos I and II with IC50 values of 45 and 60 μM,

respectively (data not shown). The data show that the inhibitory

effect on Topos I and II of β-mangostin was more potent than that

of topotecan and doxorubicin, respectively. The inhibition of human

Topos activities by β-mangostin was approximately the same order of

potency compared with that of the activities of mammalian Pols

except for X-family of Pols (Table

I).

| Table IIC50 values of β-mangostin

on the activities of mammalian Pols, human Topos and various DNA

metabolic enzymes. |

Table I

IC50 values of β-mangostin

on the activities of mammalian Pols, human Topos and various DNA

metabolic enzymes.

| Enzyme | IC50

values (μM) |

|---|

| Mammalian Pols |

| A-Family of

Pol |

| Human Pol γ | 8.6±0.51 |

| B-Family of

Pols |

| Calf Pol α | 6.4±0.38 |

| Human Pol δ | 7.4±0.44 |

| Human Pol ɛ | 8.5±0.50 |

| X-Family of

Pols |

| Rat Pol β | 34.8±2.1 |

| Human Pol λ | 28.5±1.7 |

| Human Pol μ | 38.2±2.2 |

| Calf TdT | 39.6±2.3 |

| Y-Family of

Pols |

| Human Pol η | 9.3±0.55 |

| Mouse Pol ι | 8.7±0.52 |

| Human Pol κ | 9.2±0.54 |

| Human Topos |

| Human Topo I | 10±1.0 |

| Human Topo II | 8.5±0.9 |

| Other DNA metabolic

enzymes |

| T7 RNA

polymerase | >200 |

| T4 polynucleotide

kinase | >200 |

| Bovine

deoxyribonuclease I | >200 |

In contrast, β-mangostin did not influence the

activities of other DNA metabolic enzymes, such as T7 RNA

polymerase, T4 polynucleotide kinase, and bovine deoxyribonuclease

I (Table I). These results

indicate that β-mangostin can be specifically classified as an

inhibitor of mammalian Pols and Topos.

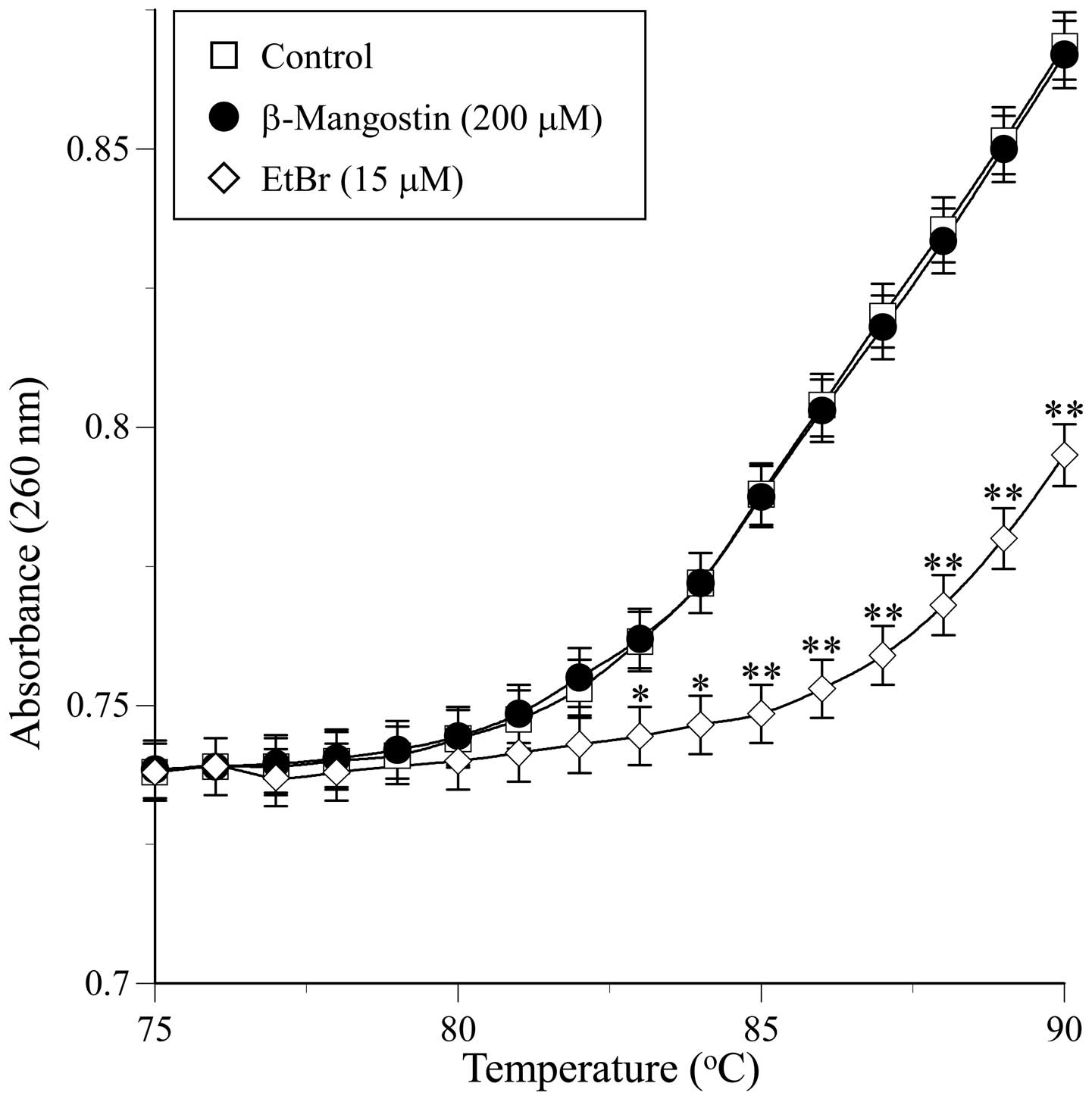

Influence of β-mangostin on the

hyperchromicity of dsDNA

Specific assays were performed to determine whether

β-mangostin-induced inhibition resulted from the ability of the

compound to bind to DNA or the enzyme. The interaction of

β-mangostin with dsDNA was investigated by studying its thermal

transition. The melting temperature (Tm) of dsDNA in the presence

of an excess of β-mangostin (200 μM) was observed using a

spectrophotometer equipped with a thermoelectric cell holder. As

shown in Fig. 4, a thermal

transition (i.e., Tm) from 75 to 90ºC was not observed within the

concentration range used in the assay, whereas when a typical

intercalating compound, such as EtBr (15 μM), was used as a

positive control, an obvious thermal transition was observed.

We then assessed whether the inhibitory effect of

β-mangostin on mammalian Pols and Topos resulted from non-specific

adhesion to the enzyme or from selective binding to specific sites.

Neither excessive nucleic acid [in the form of Poly(rC)] nor

protein (BSA) significantly influenced β-mangostin-induced both Pol

and Topo inhibition (data not shown). This suggests that

β-mangostin selectively bound to the Pol and Topo molecules. These

observations reveal that β-mangostin does not act as a DNA

intercalating agent, and rather it directly binds the enzyme to

inhibit its activity.

Collectively, these results suggested that

β-mangostin might be a potent and selective inhibitor of mammalian

Pols and Topos. We next investigated whether Pol and/or Topo

inhibition by β-mangostin resulted in decreases in human cancer

cell proliferation.

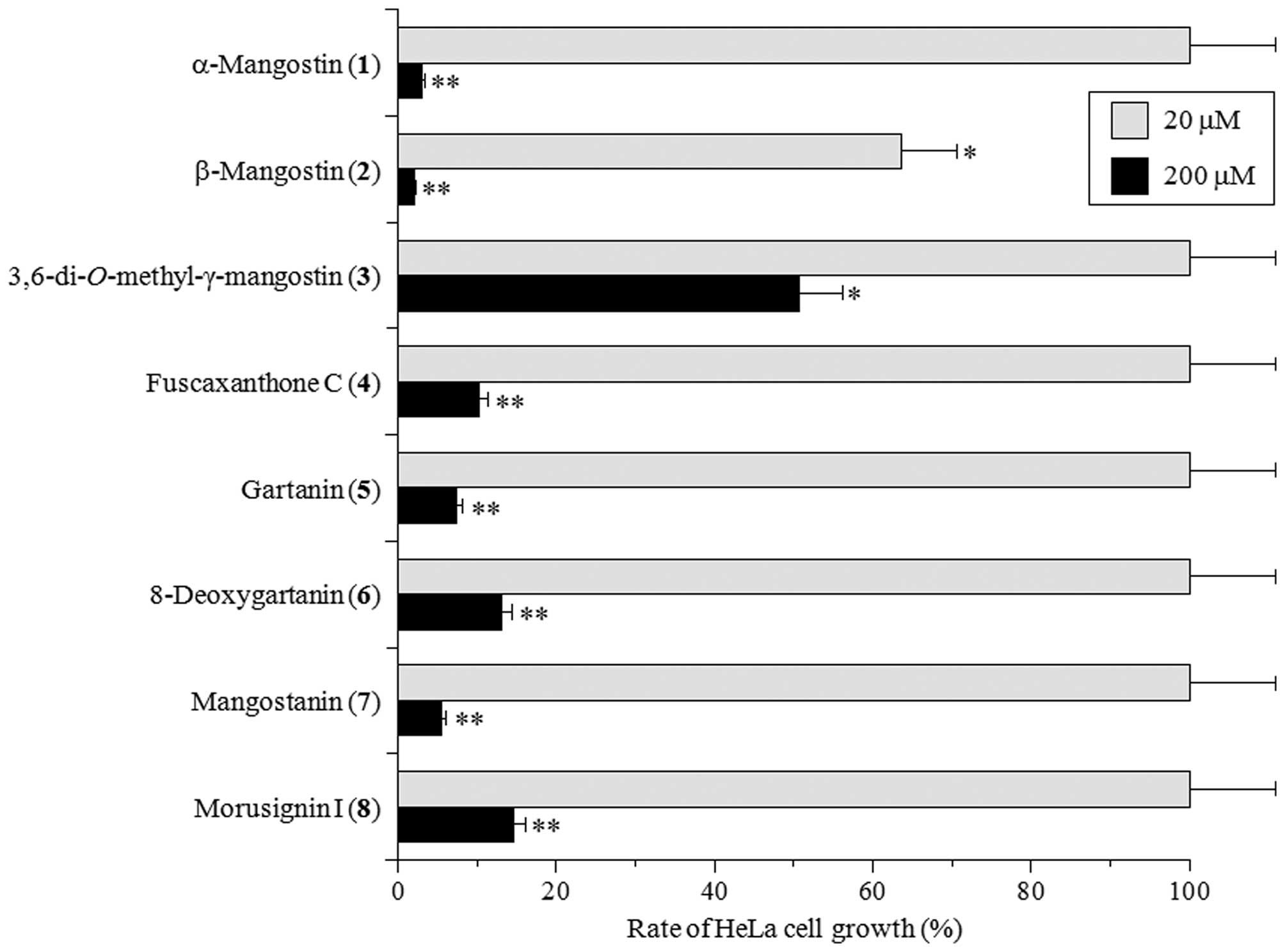

Effect of the isolated xanthone compounds

1-8 on cultured human cancer cells

Pols and Topos have recently emerged as important

cellular targets for the development of anticancer agents.

Therefore, we also investigated whether the eight isolated

xanthones had any cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells. At 100 μM, all

the compounds except for 3,6-di-O-methyl-γ-mangostin

(3) potently suppressed the rate of HeLa cell growth to

<80% that of control (Fig. 5).

At 10 μM, β-mangostin (2) could moderately suppress HeLa

cell growth, but other compounds did not influence cell

proliferation. The 50% lethal dose (LD50) of β-mangostin

(2) was 27.2 μM, which is ~2-fold higher than the

IC50 for DNA replicative Pols (X-family Pols α, δ and ɛ)

and Topos. This suggests that β-mangostin may be able to penetrate

the cell membrane and reach the nucleus, where it may then inhibit

Pols and/or Topos activities to suppress cell growth. Similar

findings for all eight xanthones were observed in the HCT116 human

colon carcinoma cell line (data not shown). These results reveal

that Pol and Topo inhibition (Figs.

2 and 3) and human cancer cell

cytotoxicity (Fig. 5) can be

induced by xanthones from mangosteen. Therefore, Pol/Topo

inhibition by β-mangostin represents a potentially useful

anticancer effect.

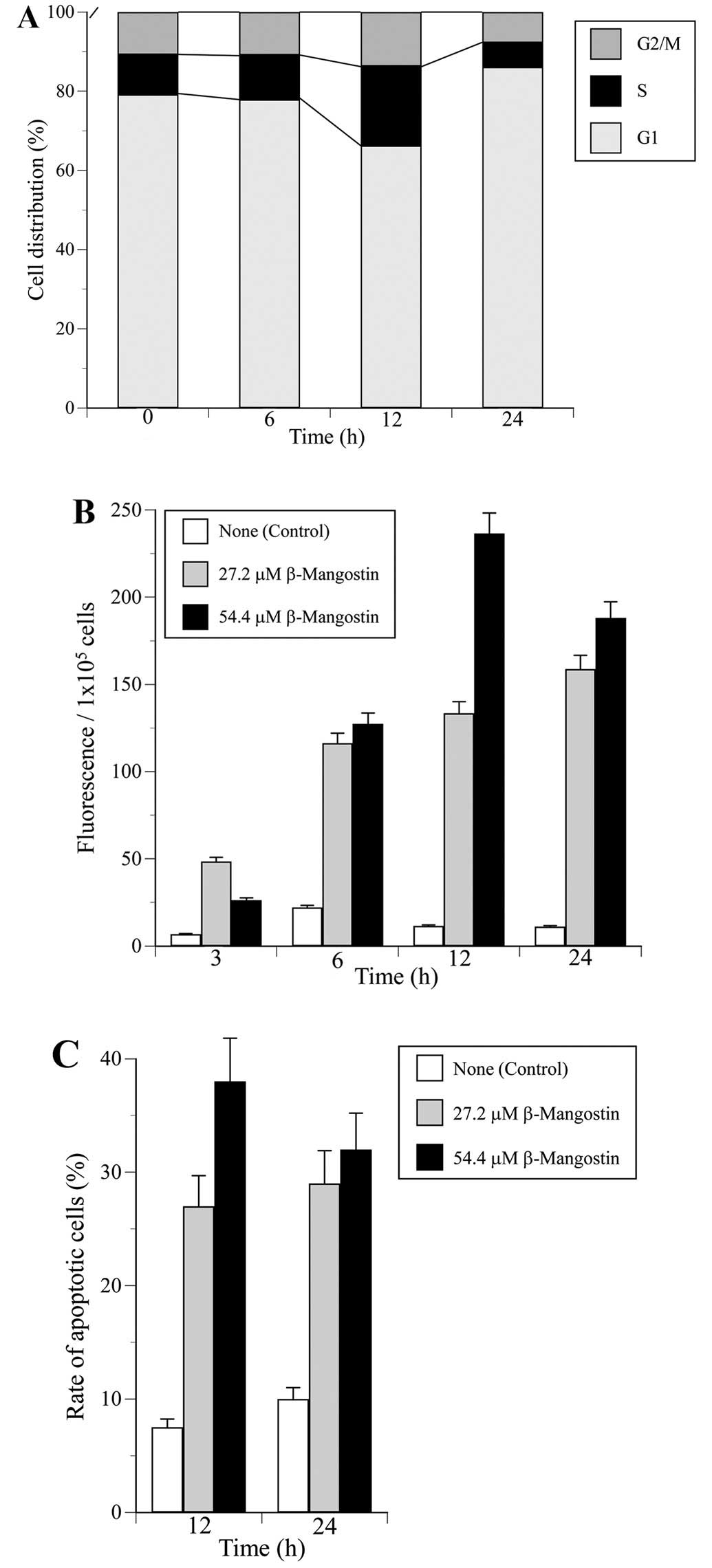

Next we analyzed whether β-mangostin could affect

the cell cycle distribution of HeLa cells. The cell cycle fraction

was recorded after 0, 6, 12 and 24 h of treatment with a

concentration of β-mangostin at 54.4 μM (the double density of

LD50). The ratio of cells in each of the three cell

cycle phases (G1, S and G2/M) is shown in Fig. 6A. Treatment with β-mangostin

significantly increased the population of cells in S and G1 phase

at 12 and 24 h, respectively, but did not influence the rate of

G2/M phase. Dehydroaltenusin, which is a mammalian Pol α specific

inhibitor, arrested the cell cycle in the G1 and S phases (50), and etoposide, which is a classical

Topo II inhibitor, arrested the cell cycle in the G2/M phase (data

not shown). These results suggest that β-mangostin may be an

effective inhibitor of DNA replicative Pols, such as Pol α, that

arrests the cell cycle at the G1 and S phases.

To examine whether the cell cycle arrest of HeLa

cells treated with β-mangostin was due to apoptosis, caspase-3

activity was analyzed using fluorescent substrate (Fig. 6B). When HeLa cells were treated

with the compound at 27.2 (=LD50 value) and 54.4 μM, the

cells maximally increased caspase-3 activity for 24 and 12 h,

respectively (Fig. 6B). In

addition, preincubation with a caspase-3 inhibitor, DEVD-CHO,

completely blocked this activity by β-mangostin (data not shown),

suggesting that the apoptosis by this compound was mediated through

caspase-3 activation.

Fig. 6C and D shows

the extent of apoptotic cells by DAPI staining. The percentage of

HeLa apoptotic cells after treatment with 27.2 and 54.4 μM of

β-mangostin was markedly high for 24 and 12 h, respectively

(Fig. 6C). These findings suggest

that the human cancer cytotoxic effect of β-mangostin must involve

a combination of cell proliferation arrest and apoptotic cell

death.

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the inhibitory

effects of xanthones isolated from mangosteen (G. mangostana

L.) (i.e., compounds 1-8 in Fig. 1) on the activities of mammalian Pol

species. β-Mangostin was the strongest inhibitor of mammalian Pols

α, β, γ and κ as the representatives of Pol families B, X, A and Y,

respectively (Fig. 2), and human

Topos I and II (Fig. 3) among the

compounds investigated. Its human cancer cytotoxicity (Fig. 5) was realized through the

inhibition of the DNA metabolic enzymes Pols and Topos, which are

essential for DNA replication, repair and recombination as well as

cell division.

Topo inhibitors, such as adriamycin, amsacrine,

ellipticine, saintopin, streptonigrin and terpentecin, are

intercalating agents that are thought to bind directly to the DNA

molecule and subsequently indirectly inhibit both types of Topo

activity (51). These chemicals

inhibit the DNA chain rejoining reactions catalyzed by Topos by

stabilizing a tight Topo protein-DNA complex termed the ‘cleavable

complex’ (52,53). The possible binding of β-mangostin

to DNA was examined by measuring the Tm of dsDNA, and no

β-mangostin was found to bind to dsDNA (Fig. 4). Topo inhibitors are categorized

into two classes, ‘suppressors’, which are believed to interact

directly with the enzyme, and ‘poisons’, which stimulate DNA

cleavage and intercalation (54,55).

β-Mangostin may be considered a suppressor of Topo functions rather

than a conventional poison as this compound does not appear to

stabilize Topo protein-DNA covalent complexes, as do the

above-mentioned agents. Therefore, β-mangostin could be a new type

of Topo inhibitor.

The fifteen Pols encoded by mammalian genomes are

specialized for different functions, including DNA replication, DNA

repair, recombination and translesion synthesis (6). Some Pol inhibitors, such as cytosine

arabinoside (AraC), are anti-cancer drugs, because these compounds

inhibit the activities of DNA replicative Pols α, δ and ɛ, suppress

DNA synthesis, arrest cells at S phase, and induce apoptosis in

cancer cells that have higher cellular Pol activity than normal

cells (56). β-Mangostin

suppressed proliferation of HeLa cell growth (Fig. 5) and arrested the cell cycle at S

phase (Fig. 6A). These effects

occur via the inhibition of Pols, especially DNA replicative

B-family Pol species (Fig. 2 and

Table I), suggesting that this

compound affects the cellular DNA synthesis of cancer cells.

Together this suggests that foods containing β-mangostin have

potential positive effects in the prevention of cancer and

promotion of health.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported in part by the

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology

(MEXT), Japan, and the Japan-Supported Program for the Strategic

Research Foundation at Private Universities, 2012–2016. T.T.

acknowledges Kobe Pharmaceutical University Collaboration Fund.

Abbreviations:

|

Pol

|

DNA polymerase (E.C.2.7.7.7)

|

|

Topo

|

DNA topoisomerase

|

|

dsDNA

|

double-stranded DNA

|

|

TdT

|

terminal deoxynucleotidyl

transferase

|

|

dTTP

|

2′-deoxythymidine-5′-tripho-sphate

|

|

dNTP

|

2′-deoxynucleoside 5′-triphosphate

|

|

DMSO

|

dimethyl sulfoxide

|

|

EDTA

|

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

|

|

BSA

|

bovine serum albumin

|

|

SDS

|

sodium dodecyl sulfate

|

|

EtBr

|

ethidium bromide

|

|

ssDNA

|

single-stranded DNA

|

|

DAPI

|

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

|

|

SD

|

standard deviation

|

|

IC50

|

50% inhibitory concentration

|

|

Tm

|

melting temperature

|

|

LD50

|

50% lethal dose

|

References

|

1

|

Liu RH: Potential synergy of

phytochemicals in cancer prevention: Mechanism of action. J Nutr.

134(Suppl): 3479S–3485S. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Surh YJ: Cancer chemoprevention with

dietary phytochemicals. Nat Rev Cancer. 3:768–780. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kornberg A and Baker TA: DNA replication.

2nd edition. W.D. Freeman and Co; New York: pp. 197–225. 1992

|

|

4

|

Hubscher U, Maga G and Spadari S:

Eukaryotic DNA polymerases. Annu Rev Biochem. 71:133–163. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bebenek K and Kunkel TA: DNA repair and

replication. Advances in Protein Chemistry. Yang W: Elsevier; San

Diego: pp. 137–165. 2004, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Lange SS, Takata K and Wood RD: DNA

polymerases and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 11:96–110. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Loeb LA and Monnat RJ Jr: DNA polymerases

and human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 9:594–604. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wang JC: DNA topoisomerases. Annu Rev

Biochem. 65:635–692. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Liu LF: DNA topoisomerase poisons as

antitumor drugs. Annu Rev Biochem. 58:351–375. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sakaguchi K, Sugawara F and Mizushina Y:

Inhibitors of eukaryotic DNA polymerases. Seikagaku. 74:244–251.

2002.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Berdis AJ: DNA polymerases as therapeutic

targets. Biochemistry. 47:8253–8260. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ji X, Avula B and Khan IA: Quantitative

and qualitative determination of six xanthones in Garcinia

mangostana L. by LC-PDA and LC-ESI-MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal.

43:1270–1276. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wexler B: Mangosteen. Woodland Publishing;

Utah: 2007

|

|

14

|

Akao Y, Nakagawa Y, Iinuma M and Nozawa Y:

Anti-cancer effects of xanthones from pericarps of mangosteen. Int

J Mol Sci. 9:355–370. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Yoo JH, Kang K, Jho EH, Chin YW, Kim J and

Nho CW: α- and γ-Mangostin inhibit the proliferation of colon

cancer cells via β-catenin gene regulation in Wnt/cGMP signalling.

Food Chem. 129:1559–1566. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Cui J, Hu W, Cai Z, Liu Y, Li S, Tao W and

Xiang H: New medicinal properties of mangostins: Analgesic activity

and pharmacological characterization of active ingredients from the

fruit hull of Garcinia mangostana L. Pharmacol Biochem Behav.

95:166–172. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jung HA, Su BN, Keller WJ, Mehta RG and

Kinghorn AD: Antioxidant xanthones from the pericarp of Garcinia

mangostana (Mangosteen). J Agric Food Chem. 54:2077–2082. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Chen LG, Yang LL and Wang CC:

Anti-inflammatory activity of mangostins from Garcinia mangostana.

Food Chem Toxicol. 46:688–693. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Nakatani K, Atsumi M, Arakawa T, Oosawa K,

Shimura S, Nakahata N and Ohizumi Y: Inhibitions of histamine

release and prostaglandin E2 synthesis by mangosteen, a Thai

medicinal plant. Biol Pharm Bull. 25:1137–1141. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sakagami Y, Iinuma M, Piyasena KG and

Dharmaratne HR: Antibacterial activity of α-mangostin against

vancomycin resistant Enterococci (VRE) and synergism with

antibiotics. Phytomedicine. 12:203–208. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Suksamrarn S, Suwannapoch N, Phakhodee W,

Thanuhiranlert J, Ratananukul P, Chimnoi N and Suksamrarn A:

Antimycobacterial activity of prenylated xanthones from the fruits

of Garcinia mangostana. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 51:857–859. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Kaomongkolgit R, Jamdee K and Chaisomboon

N: Antifungal activity of alpha-mangostin against Candida albicans.

J Oral Sci. 51:401–406. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chen SX, Wan M and Loh BN: Active

constituents against HIV-1 protease from Garcinia mangostana.

Planta Med. 62:381–382. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Devi Sampath P and Vijayaraghavan K:

Cardioprotective effect of alpha-mangostin, a xanthone derivative

from mangosteen on tissue defense system against

isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rats. J Biochem Mol

Toxicol. 21:336–339. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Weecharangsan W, Opanasopit P, Sukma M,

Ngawhirunpat T, Sotanaphun U and Siripong P: Antioxidative and

neuroprotective activities of extracts from the fruit hull of

mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana Linn.). Med Princ Pract.

15:281–287. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Tang YP, Li PG, Kondo M, Ji HP, Kou Y and

Ou B: Effect of a mangosteen dietary supplement on human immune

function: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J

Med Food. 12:755–763. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ryu HW, Curtis-Long MJ, Jung S, Jin YM,

Cho JK, Ryu YB, Lee WS and Park KH: Xanthones with neuraminidase

inhibitory activity from the seedcases of Garcinia mangostana.

Bioorg Med Chem. 18:6258–6264. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ito C, Itoigawa M, Takakura T, Ruangrungsi

N, Enjo F, Tokuda H, Nishino H and Furukawa H: Chemical

constituents of Garcinia fusca: Structure elucidation of eight new

xanthones and their cancer chemopreventive activity. J Nat Prod.

66:200–205. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hano Y, Okamoto T, Suzuki K, Negishi M and

Nomura T: Constituents of the Moraceae plants. 17 Components of the

root bark of Morus insignis Bur 3 Structures of three new

isopre-nylated xanthones morusignins I, J, and K and an

isoprenylated flavone morusignin L. Heterocycles. 36:1359–1366.

1993. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Bennett GJ, Lee HH and Das NP:

Biosynthesis of mangostin. Part 1 The origin of the xanthone

skeleton. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1(10): 2671–2676. 1990.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Tamai K, Kojima K, Hanaichi T, Masaki S,

Suzuki M, Umekawa H and Yoshida S: Structural study of

immunoaffinity-purified DNA polymerase α-DNA primase complex from

calf thymus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 950:263–273. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Date T, Yamaguchi M, Hirose F, Nishimoto

Y, Tanihara K and Matsukage A: Expression of active rat DNA

polymerase β in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 27:2983–2990. 1988.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Umeda S, Muta T, Ohsato T, Takamatsu C,

Hamasaki N and Kang D: The D-loop structure of human mtDNA is

destabilized directly by 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion

(MPP+), a parkinsonism-causing toxin. Eur J Biochem.

267:200–206. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Oshige M, Takeuchi R, Ruike T, Kuroda K

and Sakaguchi K: Subunit protein-affinity isolation of Drosophila

DNA polymerase catalytic subunit. Protein Expr Purif. 35:248–256.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kusumoto R, Masutani C, Shimmyo S, Iwai S

and Hanaoka F: DNA binding properties of human DNA polymerase et

al: Implications for fidelity and polymerase switching of

translesion synthesis. Genes Cells. 9:1139–1150. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Biertümpfel C, Zhao Y, Kondo Y,

Ramón-Maiques S, Gregory M, Lee JY, Masutani C, Lehmann AR, Hanaoka

F and Yang W: Structure and mechanism of human DNA polymerase eta.

Nature. 465:1044–1048. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ohashi E, Murakumo Y, Kanjo N, Akagi J,

Masutani C, Hanaoka F and Ohmori H: Interaction of hREV1 with three

human Y-family DNA polymerases. Genes Cells. 9:523–531. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Shimazaki N, Yoshida K, Kobayashi T, Toji

S, Tamai K and Koiwai O: Over-expression of human DNA polymerase

lambda in E. coli and characterization of the recombinant enzyme.

Genes Cells. 7:639–651. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Mizushina Y, Tanaka N, Yagi H, Kurosawa T,

Onoue M, Seto H, Horie T, Aoyagi N, Yamaoka M, Matsukage A, et al:

Fatty acids selectively inhibit eukaryotic DNA polymerase

activities in vitro. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1308:256–262. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Mizushina Y, Yoshida S, Matsukage A and

Sakaguchi K: The inhibitory action of fatty acids on DNA polymerase

β. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1336:509–521. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ogawa A, Murate T, Suzuki M, Nimura Y and

Yoshida S: Lithocholic acid, a putative tumor promoter, inhibits

mammalian DNA polymerase β. Jpn J Cancer Res. 89:1154–1159. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Yonezawa Y, Tsuzuki T, Eitsuka T, Miyazawa

T, Hada T, Uryu K, Murakami-Nakai C, Ikawa H, Kuriyama I, Takemura

M, et al: Inhibitory effect of conjugated eicosapentaenoic acid on

human DNA topoisomerases I and II. Arch Biochem Biophys.

435:197–206. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Nakayama C and Saneyoshi M: Inhibitory

effects of 9-β-D-xylofuranosyladenine 5′-triphosphate on

DNA-dependent RNA polymerase I and II from cherry salmon

(Oncorhynchus masou). J Biochem. 97:1385–1389. 1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Soltis DA and Uhlenbeck OC: Isolation and

characterization of two mutant forms of T4 polynucleotide kinase. J

Biol Chem. 257:11332–11339. 1982.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Lu BC and Sakaguchi K: An endo-exonuclease

from meiotic tissues of the basidiomycete Coprinus cinereus. Its

purification and characterization. J Biol Chem. 266:21060–21066.

1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Mizushina Y, Murakami C, Ohta K, Takikawa

H, Mori K, Yoshida H, Sugawara F and Sakaguchi K: Selective

inhibition of the activities of both eukaryotic DNA polymerases and

DNA topoisomerases by elenic acid. Biochem Pharmacol. 63:399–407.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Ishiyama M, Tominaga H, Shiga M, Sasamoto

K, Ohkura Y and Ueno K: A combined assay of cell viability and in

vitro cytotoxicity with a highly water-soluble tetrazolium salt,

neutral red and crystal violet. Biol Pharm Bull. 19:1518–1520.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Mizushina Y: Specific inhibitors of

mammalian DNA polymerase species. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem.

73:1239–1251. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Mizushina Y, Kamisuki S, Mizuno T,

Takemura M, Asahara H, Linn S, Yamaguchi T, Matsukage A, Hanaoka F,

Yoshida S, et al: Dehydroaltenusin, a mammalian DNA polymerase α

inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 275:33957–33961. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Murakami-Nakai C, Maeda N, Yonezawa Y,

Kuriyama I, Kamisuki S, Takahashi S, Sugawara F, Yoshida H,

Sakaguchi K and Mizushina Y: The effects of dehydroaltenusin, a

novel mammalian DNA polymerase α inhibitor, on cell proliferation

and cell cycle progression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1674:193–199.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Gatto B, Capranico G and Palumbo M: Drugs

acting on DNA topoisomerases: Recent advances and future

perspectives. Curr Pharm Des. 5:195–215. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Larsen AK, Escargueil AE and Skladanowski

A: Catalytic topoisomerase II inhibitors in cancer therapy.

Pharmacol Ther. 99:167–181. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Teicher BA: Next generation topoisomerase

I inhibitors: Rationale and biomarker strategies. Biochem

Pharmacol. 75:1262–1271. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Bailly C: Topoisomerase I poisons and

suppressors as anticancer drugs. Curr Med Chem. 7:39–58. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Pommier Y, Leo E, Zhang H and Marchand C:

DNA topoisomerases and their poisoning by anticancer and

antibacterial drugs. Chem Biol. 17:421–433. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Park JK, Lee JS, Lee HH, Choi IS and Park

SD: Accumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-induced single

strand breaks is attributed to slower rejoining processes by DNA

polymerase inhibitor, cytosine arabinoside in CHO-K1 cells. Life

Sci. 48:1255–1261. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|