Introduction

Respiratory infections caused by various viruses,

such as influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza,

rhinovirus and human coronavirus (including severe acute

respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), pose significant public health

challenges (1). Currently,

specific antiviral treatments for a number of these viruses are

lacking, often leaving symptomatic therapy as the primary approach

for managing viral respiratory infections. Furthermore, the ongoing

threat of potential pandemics underscores the need to explore novel

approaches to combat pulmonary viral infections. Because epithelial

cells in the respiratory tract are vulnerable to various viral

pathogens, a detailed understanding of the immune system in the

airway epithelium is essential for developing new therapeutic

strategies.

The innate immune system is a frontline defense

against invading microbes, orchestrating subsequent adaptive immune

responses (2). Recognition of

pathogen-associated molecular patterns by pattern-recognition

receptors triggers the initiation of innate immune responses. Among

these receptors, Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) serves as a key

receptor for virus-derived double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) (3), and is prominently expressed in airway

epithelial cells. Activation of TLR3 by dsRNA leads to the

activation of NF-κB and interferon regulatory factor 3, resulting

in the production of cytokines and chemokines that are pivotal in

orchestrating immune and inflammatory responses (4–6).

Central to this antiviral defense mechanism is the induction of

type I interferons (IFNs) by TLR3 signaling, with IFN-β emerging as

a principal type I IFN in bronchial epithelial cells (7). Following IFN-β production, hundreds

of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) are upregulated, forming a complex

network that modulates both innate and adaptive immune responses

(8). For example, IFN-β induces

the expression of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), a

chemokine that promotes lymphocyte chemotaxis (9), and melanoma

differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5), a dsRNA receptor and

signaling molecule (10).

Furthermore, ISG56 and ISG60 have also been speculated to

contribute to antiviral immunity alongside other ISGs (11).

Despite extensive studies (12,13)

on the molecular mechanisms underlying inflammatory responses and

innate antiviral immunity in airway epithelial cells, the specific

roles of ISGs remain incompletely understood. ISG56, also known as

IFN-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 (IFIT1),

encodes a protein with a helix-turn-helix four-repeat motif that

mediates various antiviral responses (11). A previous study has shown that

ISG56 mediates CXCL10 expression in BEAS-2B bronchial epithelial

cells during TLR3 signaling (14).

ISG60 is another IFIT protein, also known as retinoic

acid-inducible gene G (15) and

IFIT3 (16), which induces IFN-β

signaling and suppresses adenovirus early gene expression in

alveolar adenocarcinoma cell-derived 293FT cells, A549 cells and

immortalized normal human diploid fibroblasts (17). These studies suggest that ISG60 may

have a crucial role in host defense against adenovirus infection;

however, the mechanisms by which ISG60 exerts its antiviral

function via TLR3 signaling in airway epithelial cells remain

unknown. The present study aimed to investigate the function and

expression of ISG60 in BEAS-2B cells primed with a TLR3 ligand,

polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly IC).

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Noncancerous bronchial epithelial cell-derived

BEAS-2B cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured at

37°C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (Biowest), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin B and

250 ng/ml Amphotericin B (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) as previously

described (14). Poly IC (cat. no.

P9582; MilliporeSigma) was added to the cell culture medium for

treatment at 37°C. To examine the concentration-dependent effect of

poly IC, the cells were treated with 3, 5, 10, 30 and 50 µg/ml poly

IC for 16 h (for mRNA expression analysis) or 24 h (for protein

expression analysis). In time course experiments, the cells were

treated with 30 µg/ml poly IC for 2, 4, 8, 16 and 24 h. For RNA

interference, cells at 50–70% density cultured for 24 h in

antibiotic-free medium were transfected at 37°C with either

negative control small interfering RNA (siRNA) (cat. no. 1027281;

Qiagen GmbH), or siRNAs against IFN-β (custom synthesized by

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) (18), ISG56 (cat. no. SI02660777; Qiagen

GmbH) or ISG60 (cat. no. SI04197788 as ISG60 si-1; cat. no.

SI03152737 as ISG60 si-2; Qiagen GmbH) at a concentration of 10

pmol/ml using Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After 4 h of transfection, the medium was

changed, and the cells were subjected to subsequent experiments 48

h after transfection. The siRNA sequences for IFN-β, ISG56 and

ISG60 were as follows. IFN-β siRNA, sense

5′-CCAUGAGCUACAACUUGCUUGGAUU-3′, antisense

5′-AAUCCAAGCAAGUUGUAGUCUAUGG-3′; ISG56 siRNA, sense

5′-GGAUCAGAUUGAAUUCCUATT-3′, antisense 5′-UAGGAAUUCAAUCUGAUCCAA-3′;

ISG60 siRNA-1, sense 5′-AGAUGAUUGAAGCACUAAATT-3′, antisense

UUUAGUGCUUCAAUCAUCUCT-3′; ISG60 siRNA-2, sense

5′-GUCAUGGACUAUUCGAAUATT-3′ and antisense

5′-UAUUCGAAUAGUCCAUAGCAT-3′. The cells were also treated with

recombinant human [r(h)]IFN-β (ProSpec-Tany TechnoGene Ltd.) at

37°C for 16 h.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

RNA was extracted from the cultured cells using an

Illustra RNAspin kit (GE Healthcare). To denature RNA, the RNA

solution was heated at 70°C for 5 min and was then cooled

immediately on ice. Subsequently, RT was performed at 37°C for 1 h

using oligo(dT)18 primer (FASMAC), M-MLV reverse

transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and dNTP mix (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), followed by inactivation of the enzyme at

70°C for 10 min. The cDNA for 18S, CXCL10, IFN-β, ISG56, ISG60 and

MDA5 were amplified using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) with a qPCR system (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). The thermocycling conditions were as follows:

Pre-denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec; followed by 40 cycles at 95°C

for 10 sec, 60°C for 10 sec and 72°C for 20 sec; and final

extension at 72°C for 5 min. 18S ribosomal RNA was utilized as an

internal control. The 2−ΔΔCq method (19) was used for quantification. CXCL10

and IFN-β mRNA expression levels are presented in arbitrary units,

as these genes were not detectable in the cells not stimulated with

poly IC. The mRNA expression levels of the other genes are

expressed as a fold increase compared with unstimulated cells. The

following primers (custom composites purchased from FASMAC) were

used: 18S (NR_146146.1), forward (F) 5′-ACTCAACACGGGAAACCTCA-3′,

reverse (R) 5′-AACCAGACAAATCGCTCCAC-3′; CXCL10 (NM_001565.4), F

5′-TTCAAGGAGTACCTCTCTCTAG-3′, R 5′-CTGGATTCAGACATCTCTTCTC-3′; IFN-β

(NM_002176.4), F 5′-CCTGTGGCAATTGAATGGGAGGC-3′, R

5′-CCAGGCACAGTGACTGTACTCCTT-3′; ISG56 (NM_001270930.2), F

5′-TAGCCAACATGTCCTCACAGAC-3′, R 5′-TCTTCTACCACTGGTTTCATGC-3′; ISG60

(NM_001031683.4), F: 5′-GAACATGCTGACCAAGCAGA-3′, R

5′-CAGTTGTGTCCACCCTTCCT-3′; MDA5 (XM_047445407.1), F

5′-GTTGAAAAGGCTGGCTGAAAAC-3′, R 5′-TCGATAACTCCTGAACCACTG-3′.

Western blotting

After cultivation, the cells were washed twice using

phosphate-buffered saline, scraped from the dish and Laemmli sample

buffer (Cell Signaling Technologies, Inc.) was used for protein

extraction. The BCA protein assay kit (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical

Corporation) was used for protein quantification. Proteins (20

mg/lane) in the lysates were resolved using SDS-PAGE on 5–20% gels

(ATTO Corporation) and were transferred to polyvinylidene

difluoride membranes (Merck KGaA). The membranes were blocked with

Tris-buffered saline containing 5% nonfat dry milk at 25°C for 2 h,

and were then incubated with the following primary antibodies:

Rabbit anti-ISG56 (1:3,000; cat. no. GTX118713; GeneTex, Inc.),

rabbit anti-ISG60 (1:5,000; cat. no. GTX112442; GeneTex, Inc.),

rabbit anti-signal transducer and activator transcription 1 (STAT1)

(1:10,000; cat. no. sc-592; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse

anti-phosphorylated (P)-STAT1 (1:5,000; cat. no. sc-136229; Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and rabbit anti-actin IgG (1:5,000; cat.

no. A5060; MilliporeSigma) at 4°C overnight. After washing, the

membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled

secondary anti-mouse (1:10,000; cat. no. A28177; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) or anti-rabbit (1:10,000; cat. no. 458; Medical

& Biological Laboratories Co., Ltd.) IgG at 25°C for 1 h. The

Luminata Crescendo Western HRP Substrate (Merck KGaA) was utilized

for detection.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA)

After incubation, the conditioned medium was

recovered and centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. IFN-β

and CXCL10 protein concentrations in the collected supernatant were

assessed using commercial sandwich ELISA kits from PBL Assay

Science (cat. no. 41435-1) and R&D Systems, Inc. (cat. no.

DIP100), respectively. The assays were performed according to the

manufacturers' protocols.

Statistical analysis

The results of RT-qPCR and ELISA are shown using box

plots, which are presented as the median (center of the box), 25th

percentile (bottom of the box), 75th percentile (top of the box)

and range (minimum and maximum), or as the mean ± standard

deviation. The Mann-Whitney U-test, or one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's

post hoc test were utilized for statistical analyses using EZR

software version 1.65 (20)

(Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

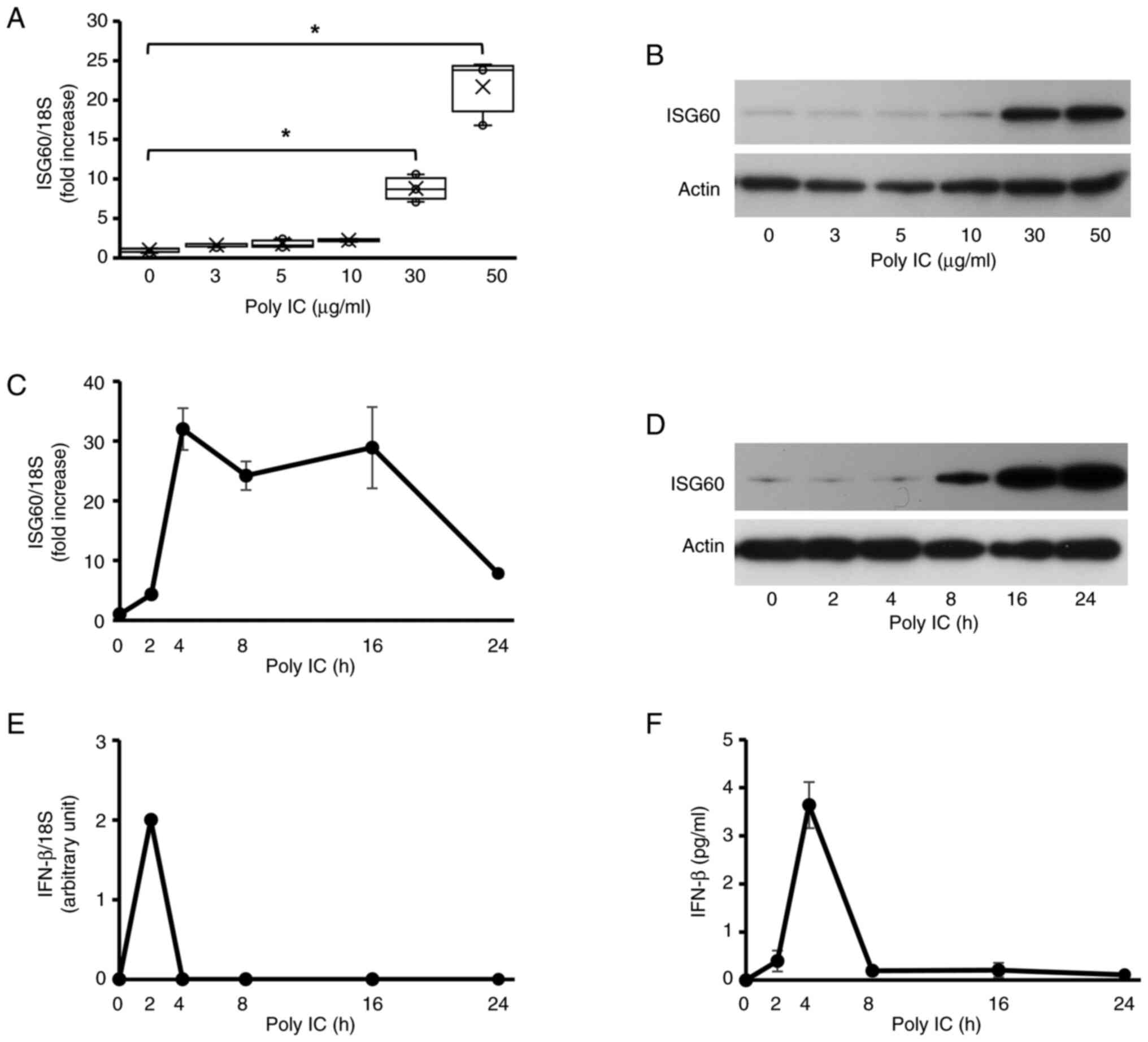

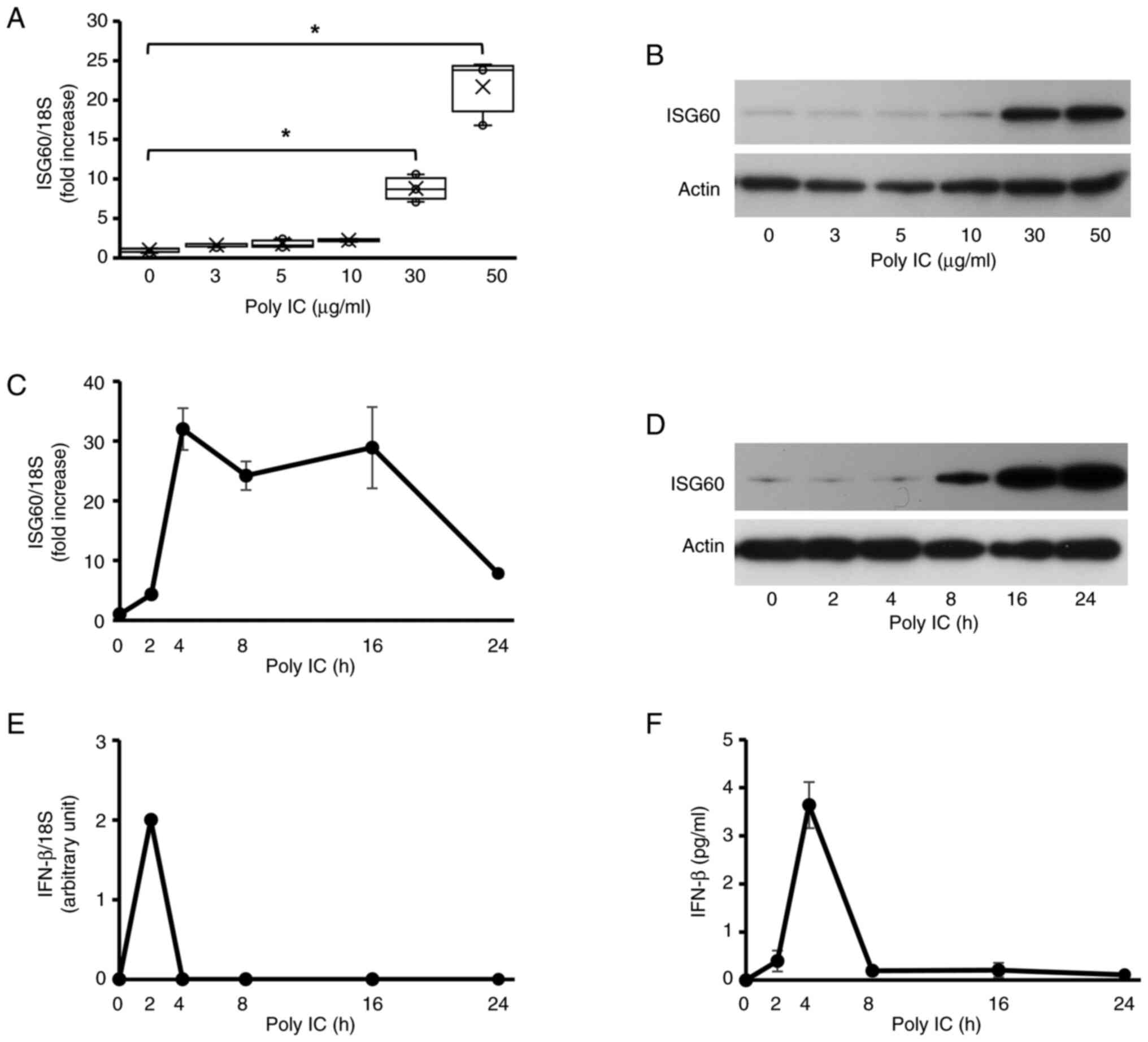

Expression of ISG60 in BEAS-2B cells

treated with poly IC

In unstimulated BEAS-2B cells, only small amounts of

ISG60 protein and mRNA were expressed. The protein and mRNA

expression levels of ISG60 increased in cells supplemented with

poly IC. At ≤10 µg/ml, poly IC did not affect the protein and mRNA

expression levels of ISG60, whereas ISG60 expression was markedly

upregulated in response to 30–50 µg/ml poly IC (Fig. 1A and B). Therefore, the cells were

supplemented with 30 µg/ml poly IC in subsequent experiments. The

mRNA expression levels of ISG60 were markedly increased at 4–16 h

and declined at 24 h in cells treated with poly IC (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, IFN-β mRNA was not

detected in unstimulated cells. Increased expression levels of

ISG60 protein were observed in cells treated with poly IC at 8 h,

which progressively increased until 24 h (Fig. 1D). Transient expression of IFN-β

mRNA was detected 2 h after poly IC treatment (Fig. 1E). IFN-β protein levels were

transiently detected in the conditioned medium from cells treated

with poly IC; they peaked at 4 h and quickly decreased thereafter

(Fig. 1F).

| Figure 1.Poly IC induces the expression of

ISG60 in BEAS-2B bronchial epithelial cells. (A and B) BEAS-2B

cells were cultured and stimulated with different concentrations of

the Toll-like receptor 3 agonist poly IC. (A) After 16 h, RNA was

extracted from the cells, and RT-qPCR analysis of ISG60 mRNA was

performed. Data are presented as box plots showing the median

(center of the box), 25th percentile (bottom of the box), 75th

percentile (top of the box) and range (minimum and maximum), and

were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's test, n=3.

*P<0.05. (B) Cellular proteins were extracted after 24 h, and

western blotting was performed for ISG60 and actin. (C-F) Cells

were stimulated with 30 µg/ml poly IC for up to 24 h. (C) ISG60

mRNA expression levels were detected using RT-qPCR analysis. (D)

ISG60 protein expression levels in cell lysates were detected using

western blotting. (E) IFN-b mRNA expression was examined using

RT-qPCR analysis. (F) IFN-β protein concentration in the

conditioned medium was measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent

assay. (C, E and F) Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3).

IFN-β, interferon β; ISG60, IFN-stimulated gene 60; poly IC,

polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

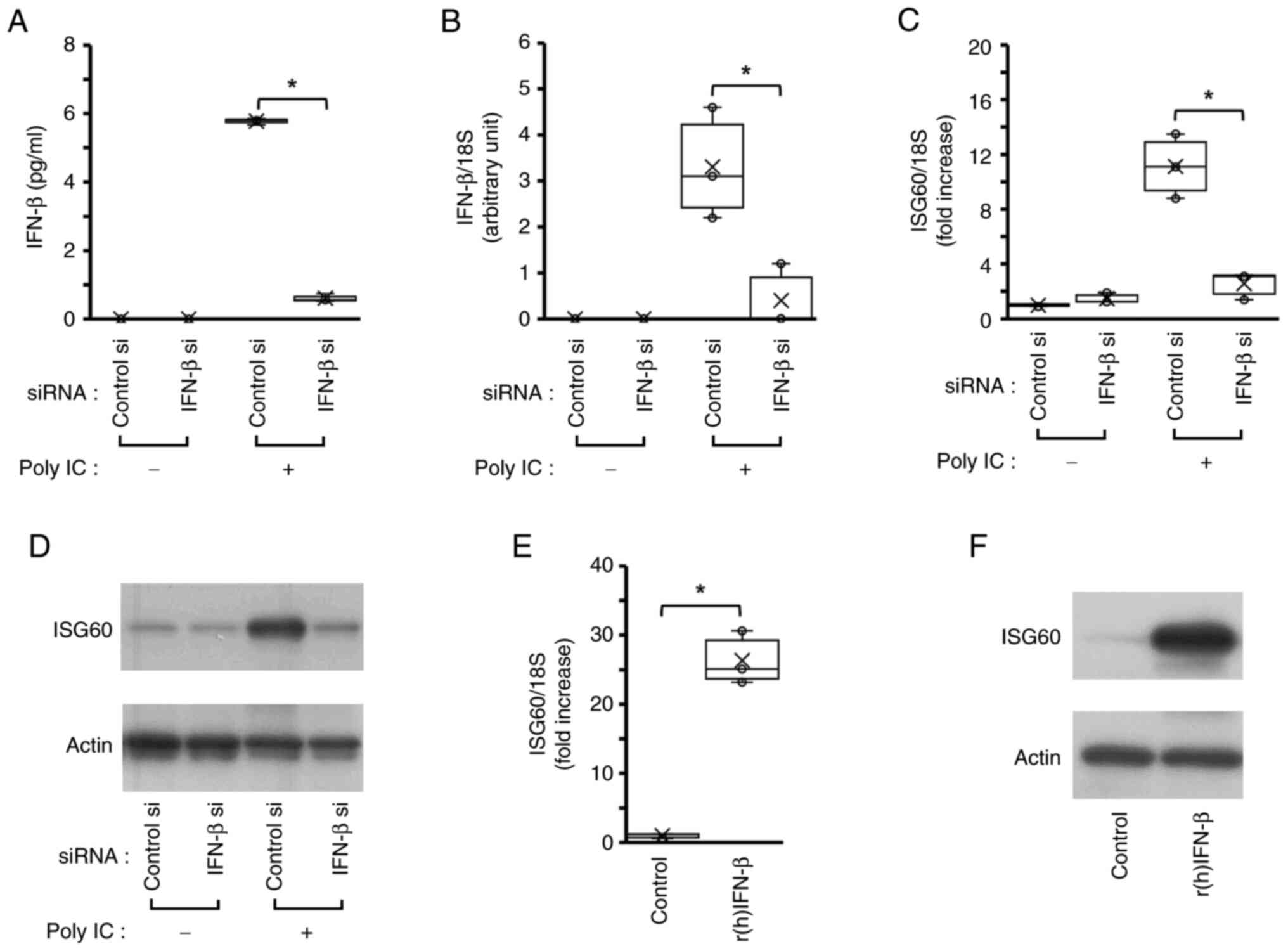

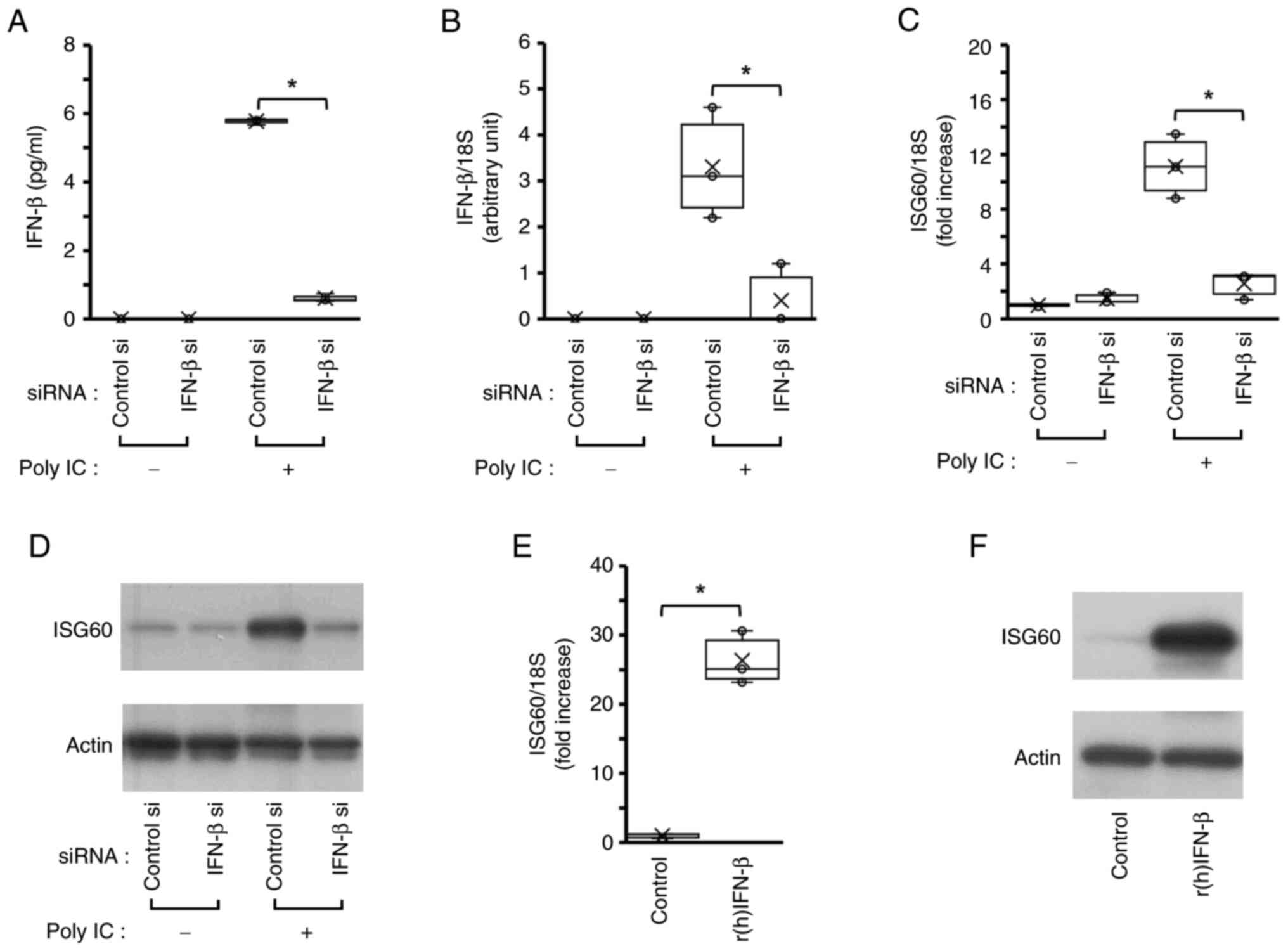

IFN-β serves a role in poly IC-induced

expression of ISG60 in BEAS-2B cells

As shown in Fig. 1E and

F, IFN-β mRNA and protein was not detected in cells without

poly IC stimulation, thus suggesting that no IFN-β mRNA and protein

are expressed in unstimulated BEAS-2B cells. In the medium

collected from cells transfected with control siRNA or IFN-β siRNA

without poly IC-stimulation, IFN-β protein was not detected

(Fig. 2A), and IFN-β mRNA

expression was also not detected in those cells (Fig. 2B). Transfection of BEAS-2B cells

with siRNA against IFN-β resulted in almost complete knockdown of

IFN-β protein and mRNA expression in poly IC-stimulated cells,

suggesting that transfection of IFN-β siRNA was successful

(Fig. 2A and B). In addition,

knockdown of IFN-β almost completely suppressed ISG60 mRNA

(Fig. 2C) and protein (Fig. 2D) expression upon poly IC

treatment. By contrast, treatment of BEAS-2B cells with 1 ng/ml

r(h)IFN-β increased the expression levels of ISG60 mRNA (Fig. 2E) and protein (Fig. 2F).

| Figure 2.IFN-β is involved in poly IC-induced

ISG60 expression. The cells were transfected with a specific siRNA

against IFN-β and were incubated for 24 h. Then, the cells were

treated with 30 µg/ml poly IC. (A) After 4 h incubation, the medium

was collected and IFN-β concentration was measured using an

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (B) After 2 h incubation, RNA

was extracted and IFN-β mRNA expression was examined using RT-qPCR.

(C) After 16 h incubation, RNA was extracted, and ISG60 mRNA

expression was examined. (D) ISG60 protein expression was analyzed

using western blotting after 24 h. The cells were treated with

r(h)IFN-β for 16 h and were subjected to (E) RT-qPCR and (F)

western blotting. *P<0.05 using Mann-Whitney U-test; n=3. IFN-β,

interferon β; ISG, IFN-stimulated gene; poly IC,

polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid; r(h), recombinant human; RT-qPCR,

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; si, small interfering. |

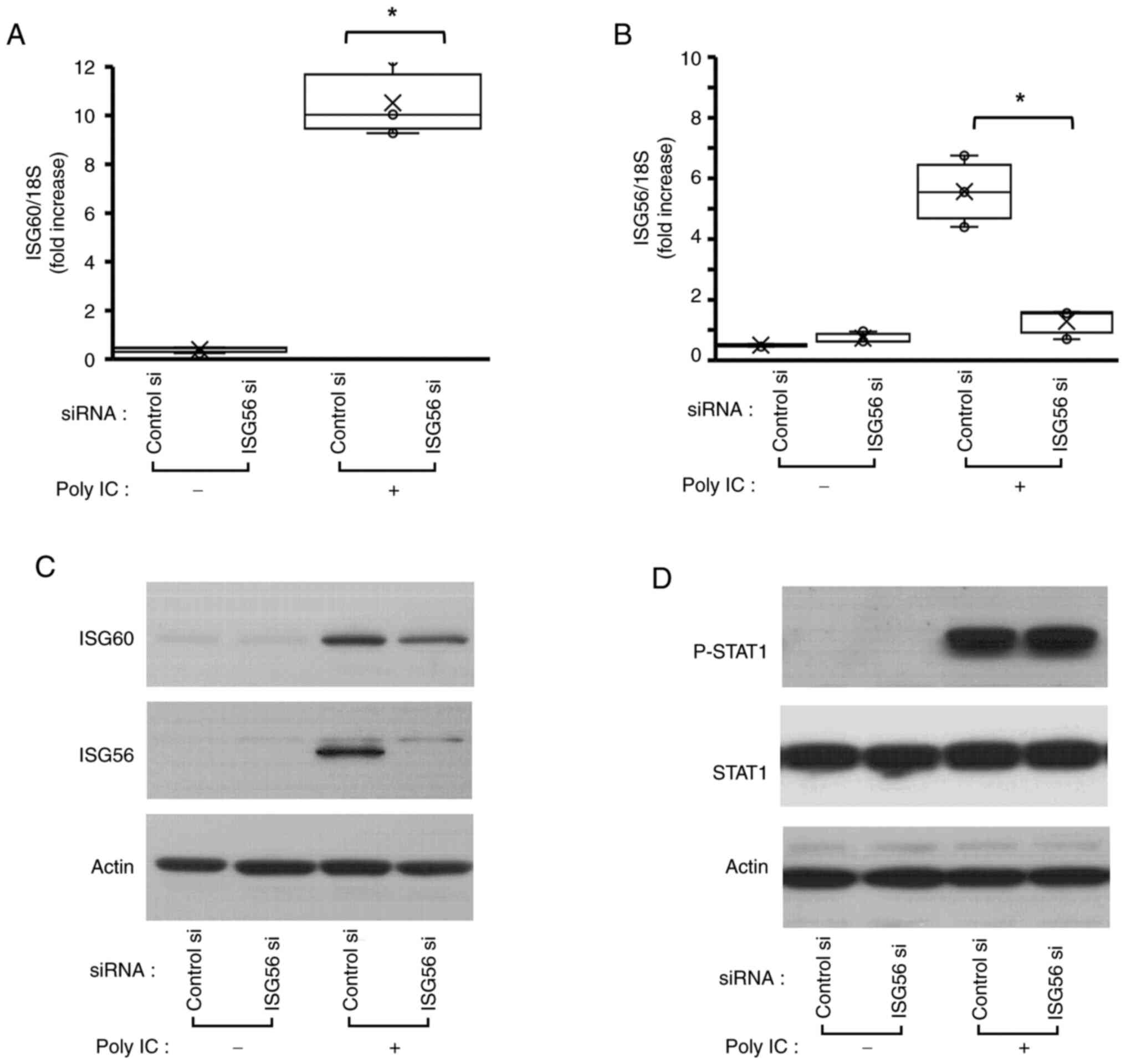

ISG56 is associated with ISG60

expression

The present study assessed the function of ISG56 on

ISG60 expression. ISG56 mRNA and protein knockdown was confirmed

using RT-qPCR (Fig. 3B) and

western blotting in poly IC-treated cells, respectively (Fig. 3C). Notably, there was no

significant difference between groups in unstimulated cells,

because ISG56 protein expression was not detectable in unstimulated

cells (Fig. 3C). ISG56 knockdown

markedly reduced poly IC-induced expression of ISG60 mRNA (Fig. 3A) and slightly reduced poly

IC-induced ISG60 protein (Fig.

3C). However, P-STAT1 expression was not affected by ISG56

knockdown (Fig. 3D).

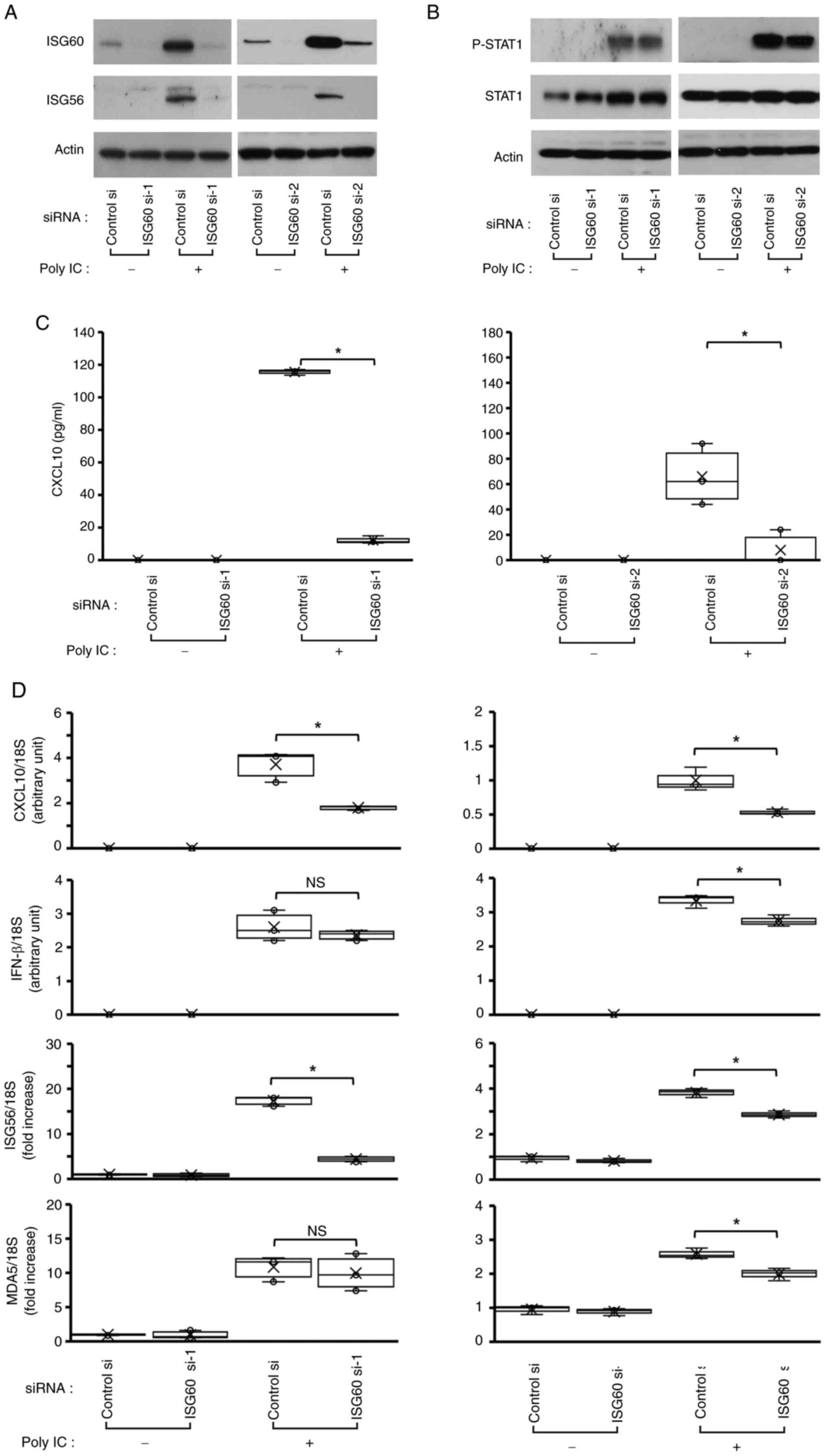

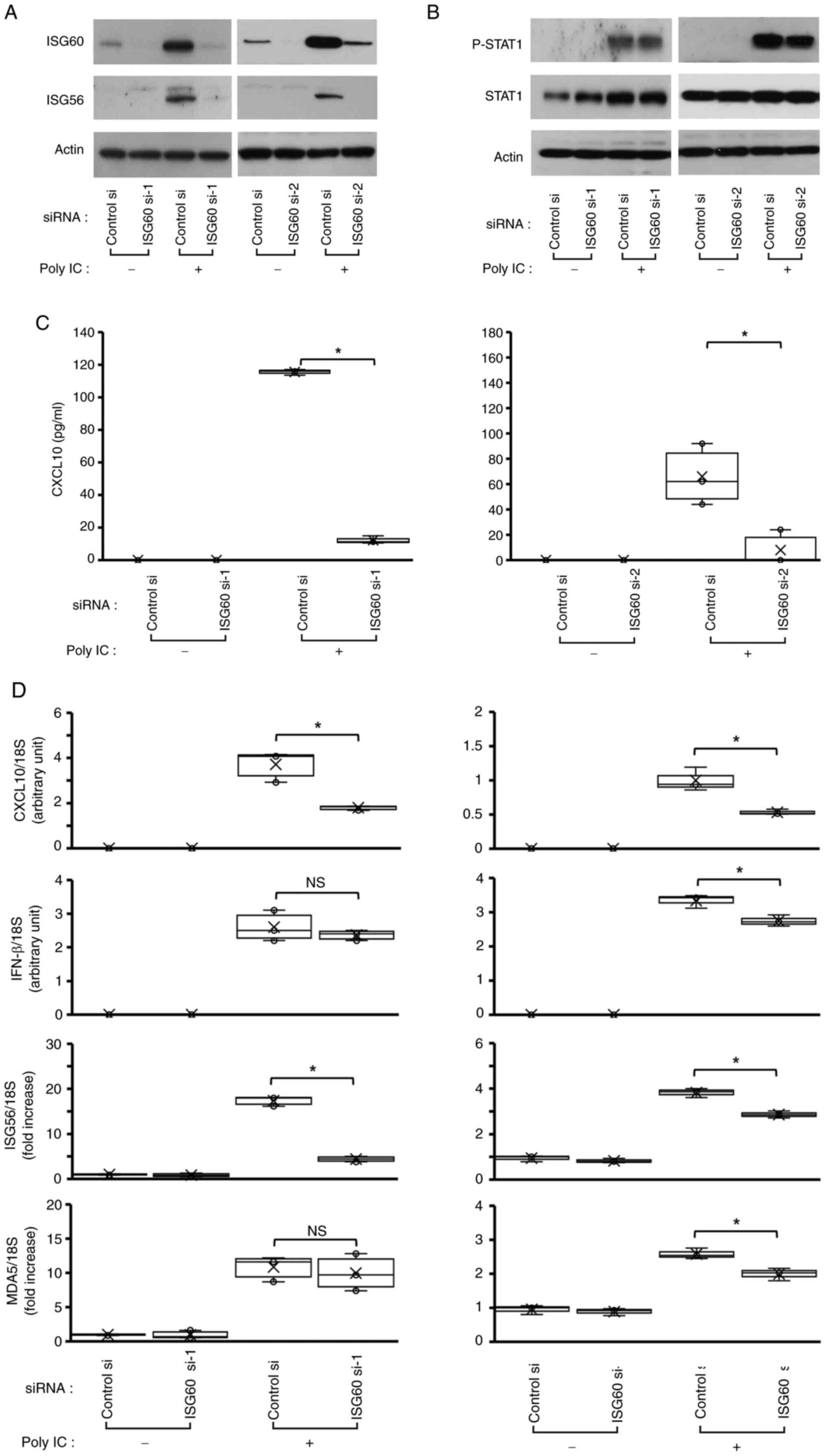

ISG60 is implicated in poly

IC-mediated expression of ISG56 and CXCL10, but does not affect

IFN-β expression and STAT1 phosphorylation

Transfection of the cells with ISG60 si-1 and ISG60

si-2, followed by western blotting, demonstrated that these two

siRNAs markedly decreased poly IC-induced ISG60 expression,

suggesting that ISG60 expression was successfully knocked down

(Fig. 4A). Furthermore, ISG60

knockdown decreased poly IC-induced protein and mRNA expression

levels of ISG56 (Fig. 4A and D),

and protein concentration and mRNA expression levels of CXCL10

(Fig. 4C and D), whereas no

notable change was observed in P-STAT1 or STAT1 protein expression

(Fig. 4B). Furthermore, knockdown

of ISG60 using ISG60 si-1 did not affect the mRNA expression levels

of IFN-β (Fig. 4D). In order to

examine whether ISG60 selectively inhibits poly IC-induced

expression of ISG56 and CXCL10, or inhibits the expression of all

ISGs, the present study next examined the effect of ISG60 knockdown

on the poly IC-induced expression of another ISG, MDA5. MDA5 was

chosen because it is one of the key ISGs in antiviral innate immune

reactions (21). The results

revealed that poly IC-induced MDA5 mRNA expression was not affected

by transfection with ISG60 si-1 (Fig.

4D). These results suggested that ISG56 and CXCL10 were

selectively regulated by ISG60. Transfection of cells with ISG60

si-2 slightly decreased the mRNA expression levels of IFN-β and

MDA5, and this may be due to weak non-specific effects.

| Figure 4.ISG60 is partially involved in poly

IC-induced expression of CXCL10 and ISG56. The cells transfected

with two different ISG60 siRNAs were treated with poly IC. (A)

After incubating for 24 h, the cells were lysed and subjected to

western blotting for ISG56, ISG60 and actin. (B) After incubating

for 6 h, the cells were lysed and subjected to western blotting for

P-STAT1, STAT1 and actin, (C) After 24 h incubation, the

cell-conditioned medium was collected, and the concentration of

CXCL10 protein was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent

assay. (D) After incubating for 2 h (for IFN-β mRNA analysis) or 16

h (for CXCL10, ISG56 and MDA5 mRNA analysis), RNA was extracted

from the cells, and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR was

performed. *P<0.05 using Mann-Whitney U-test; n=3. CXCL10, C-X-C

motif chemokine ligand 10; IFN-β, interferon β; ISG, IFN-stimulated

gene; MDA, melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5; NS, not

significant; P-, phosphorylated; poly IC,

polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid; si, small interfering; STAT1,

signal transducer and activator transcription 1. |

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that TLR3 is expressed

in various cell types, including dendritic cells (22), fibroblasts (23), intestinal epithelial cells

(24) and airway epithelial cells

(25). TLR3 serves a physiological

function in antiviral innate immunity and is involved in various

inflammatory conditions (26); for

example, TLR3-deficient mice have been reported to be susceptible

to encephalomyocarditis virus compared with wild-type mice, whereas

they were resistant to influenza virus (27). TLR3 activates the signal

transduction cascade after recognizing virus-derived dsRNA to

facilitate the transcription of type I IFNs. IFN-β is a type I IFN

mainly expressed in bronchial epithelial cells, which induces the

expression of ISGs that function in antiviral host defense

reactions.

The present study confirmed that the expression of

ISG60 in BEAS-2B cells was time- and concentration-dependent when

stimulated by poly IC. This finding is consistent with those of

previous studies showing poly IC-induced ISG60 expression in U373MG

astrocytoma cells (28) and

hCMEC/D3 human brain microvascular endothelial cells (29). These findings suggested that ISG60

may have a role in congenital antiviral immune responses in various

tissues, including bronchial epithelial cells. Because ISG60 is a

member of the ISG family, the present study investigated whether

de novo-produced IFN-β contributes to poly IC-induced ISG60

expression using RNA interference against IFN-b. As a result, IFN-β

knockdown largely suppressed poly IC-induced ISG60 expression, and

the induction of ISG60 protein and mRNA expression was observed in

BEAS-2B cells treated with r(h)IFN-β. These results indicated that

poly IC-induced ISG60 expression may be dependent on newly

synthesized IFN-β, and ISG60 was implicated in TLR3/IFN-β-mediated

antiviral reactions in BEAS-2B cells.

CXCL10, a CXC chemokine, is a robust chemoattractant

of T lymphocytes and natural killer cells, which serves various

roles in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases and infections

(30). The expression of CXCL10

must be tightly regulated to induce chemotaxis of appropriate

numbers of lymphocytes to the site of infection (31). Insufficient CXCL10 expression can

exacerbate viral infections, while excessive CXCL10 can lead to

excessive lymphocyte infiltration, resulting in tissue injury

(32). Moreover, CXCL10 protein

levels in serum and the severity of acute respiratory virus

infection have been shown to be correlated (33). Therefore, ‘fine-tuning’ CXCL10

expression is crucial for appropriate immune responses in the

airway. In the current study, ISG60 knockdown using two different

siRNAs partially decreased poly IC-induced CXCL10 mRNA expression

and protein levels. These findings indicated that ISG60 may not be

the primary regulator of CXCL10 expression, but may be implicated

in the ‘fine-tuning’ of TLR3-mediated CXCL10 expression in BEAS-2B

cells. This finding is consistent with that of a previous study in

U373 astrocytoma cells (28).

Phosphorylation of STAT1 is an important step in the

signaling pathway induced by IFN-β. In the present study, poly

IC-induced IFN-β expression and subsequent STAT1 phosphorylation

were not affected by ISG60 knockdown in BEAS-2B cells. This finding

suggested that ISG60 may be involved in a reaction downstream of

the IFN-β/STAT1 axis. However, this finding is in contrast to the

results of a previous study in U373 cells, in which ISG60

positively regulated STAT1 phosphorylation (28). Additionally, in hCMEC/D3 brain

endothelial cells, ISG60 negatively regulated TLR3-induced

signaling (29). These differences

indicated that ISG60 may function differently in various cell

types.

ISG60, also known as IFIT3 (34), is a tetratricopeptide repeat

protein that participates in various biological processes,

including protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions within

multi-molecule complexes. These proteins regulate chaperones,

transcription, splicing, cell cycle control, protein transport, and

phosphate turnover (35). In

addition, ISG56/IFIT1 is known to be linked to innate immunity

(11). In a previous study, we

reported that ISG56 may be implicated in poly IC-induced CXCL10

expression in BEAS-2B cells (14).

ISG56 is considered a partner molecule of ISG60 (11); therefore, this relationship was

further assessed in the present study. ISG60 knockdown decreased

poly IC-induced ISG56 expression, whereas poly IC-induced

expression of MDA5, another innate immunity-related ISG, remained

unchanged upon ISG60 knockdown. These findings suggested that ISG60

may selectively regulate ISG56 expression. By contrast, ISG56

knockdown decreased ISG60 expression, whereas the P-STAT1

expression did not change. These findings indicated that ISG60 and

ISG56 are mutually regulated downstream of P-STAT1 in poly

IC-treated BEAS-2B cells.

Because IFIT proteins, including ISG60 and ISG56,

are known to have broad-spectrum antiviral functions (36), the results of the present study

suggested that ISG60 and ISG56 may serve crucial roles in antiviral

innate immune reactions in airway epithelial cells. Gene expression

is regulated by protein complexes containing transcriptional

factors, transcriptional regulators, coactivators and RNA

polymerase. In addition, other components, including non-coding

RNAs, are involved in the precise control of the gene expression.

It has been reported that IFIT proteins regulate antiviral immune

reactions by mediating a variety of protein-protein and protein-RNA

interactions (11). Therefore, it

was hypothesized that ISG60, as a component of a multiple protein

complex, may regulate the expression of ISG56 and CXCL10 via

protein-protein and/or protein-RNA interactions. However, the

present study has some limitations. First, the study did not

clarify the specific molecular mechanisms by which ISG60 regulates

the poly IC-induced expression of CXCL10, or by which ISG60 and

ISG56 regulate each other. Future studies should assess the

detailed pathways and interactions involved. Second, the present

study did not examine an experimental model with ISG60

upregulation. Third, this study only used an in vitro cell

culture system. Future studies using lentiviral transfection to

upregulate ISG60 or animal models may enhance the relevance and

applicability of the present findings.

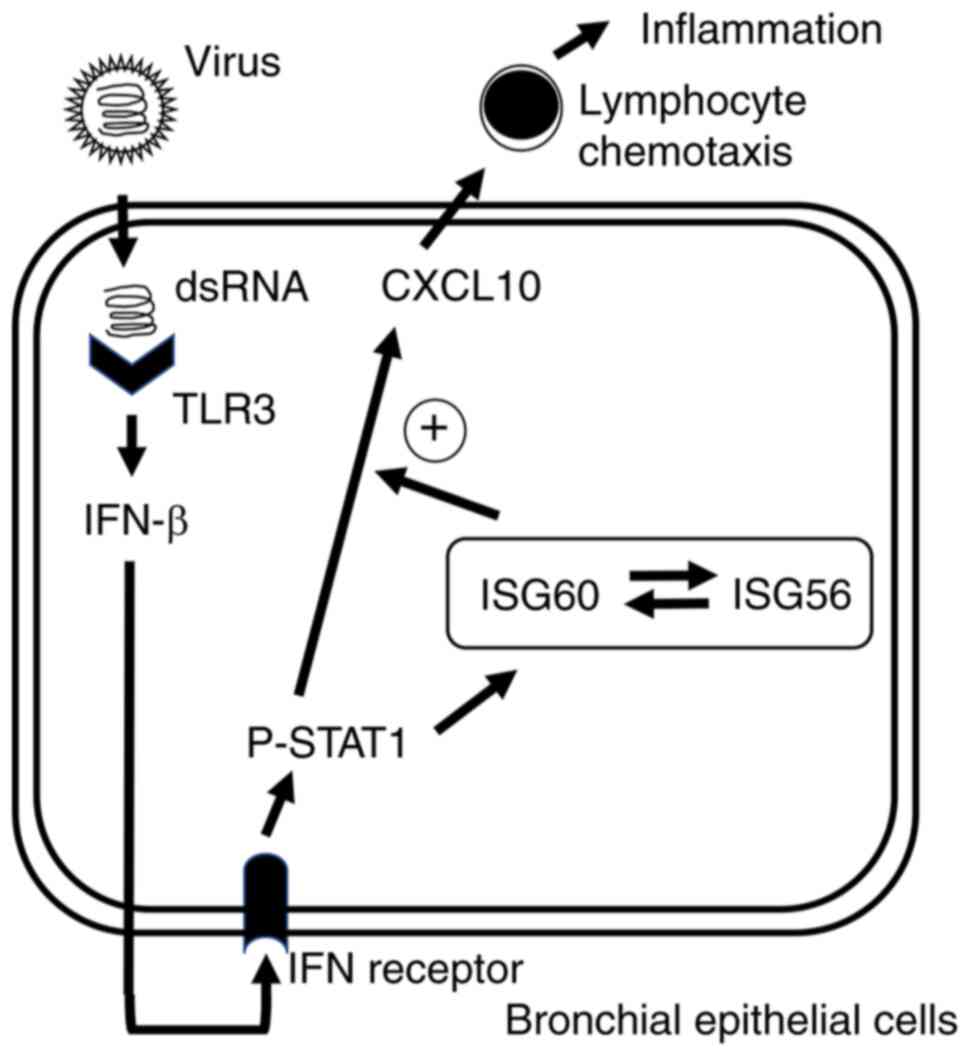

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

ISG60 was upregulated by TLR3 signaling and may have a role in the

‘fine-tuning’ of CXCL10 expression in BEAS-2B cells. The present

study reported that the TLR3/IFN-β/ISG60/CXCL10 axis (Fig. 5) may be a novel mechanism to

enhance antiviral innate immune responses in bronchial epithelial

cells. This axis may be important in antiviral immunity in the

respiratory tract and appropriate activation of this axis could

contribute to the host defense against viral infection. However,

excess or dysregulated activation of this axis may lead to excess

accumulation of lymphocytes; since excess accumulation of

lymphocytes induces the excess activation of cytokine networks

(37), dysregulated activation of

this axis may exacerbate inflammation and airway injury induced by

viral infection. Therefore, this axis may be involved in both

physiological antiviral innate immune reaction and pathological

inflammation induced by viral infection in the airways. The present

findings suggested that ISG60 may serve as a potential target for

developing new therapeutic strategies against viral respiratory

infections.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Michiko Nakata

(Department of Neuropathology, Hirosaki University Graduate School

of Medicine) for technical support.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YT and TI contributed to all experiments and

prepared the manuscript. YK performed the ELISA. MT performed the

western blotting. TS, MD and MS performed the RNA extraction and

RT-qPCR analyses. SK and KS performed the cell culturing. TI and ST

designed the study. All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript. YT and TI confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CXCL10

|

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10

|

|

dsRNA

|

double-stranded RNA

|

|

ELISA

|

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

|

|

IFN

|

interferon

|

|

IFIT1

|

IFN-induced protein with

tetratricopeptide repeats 1

|

|

ISG

|

IFN-stimulated gene

|

|

MDA5

|

melanoma differentiation-associated

gene 5

|

|

P-STAT1

|

phosphorylated-signal transducer and

activating transcription-1

|

|

poly IC

|

polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

r(h)IFN-β

|

recombinant human IFN-β

|

|

siRNA

|

small interfering RNA

|

|

TLR3

|

Toll-like receptor 3

|

References

|

1

|

Bakaletz LO: Viral-bacterial co-infections

in the respiratory tract. Curr Opin Microbiol. 35:30–35. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Medzhitov R and Janeway C Jr: Innate

immunity: Impact on the adaptive immune response. Curr Opin

Immunol. 9:4–9. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Okahira S, Nishikawa F, Nishikawa S,

Akazawa T, Seya T and Matsumoto M: Interferon-beta induction

through toll-like receptor 3 depends on double-stranded RNA

structure. DNA Cell Biol. 24:614–623. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Guillot L, Le Goffic R, Bloch S, Escriou

N, Akira S, Chignard M and Si-Tahar M: Involvement of toll-like

receptor 3 in the immune response of lung epithelial cells to

double-stranded RNA and influenza A virus. J Biol Chem.

280:5571–5580. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yu M and Levine SJ: Toll-like receptor,

RIG-I-like receptors and the NLRP3 inflammasome: Key modulators of

innate immune responses to double-stranded RNA viruses. Cytokine

Growth Factor Rev. 22:63–72. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kawai T and Akira S: The role of

pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: Update on

Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 11:373–384. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hsu ACY, Parsons K, Barr I, Lowther S,

Middleton D, Hansbro PM and Wark PAB: Critical role of constitutive

type I interferon response in bronchial epithelial cell to

influenza infection. PLoS One. 7:e329472012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Majde JA: Viral double-stranded RNA,

cytokines, and the flu. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 20:259–272.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hamamdzic D, Phillips-Dorsett T,

Altman-Hamamdzic S, London SD and London L: Reovirus triggers cell

type-specific proinflammatory responses dependent on the autocrine

action of IFN-beta. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol.

280:L18–L29. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Imaizumi T, Aizawa-Yashiro T, Tsuruga K,

Tanaka H, Matsumiya T, Yoshida H, Tatsuta T, Xing F, Hayakari R and

Satoh K: Melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 regulates the

expression of a chemokine CXCL10 in human mesangial cells:

Implications for chronic inflammatory renal diseases. Tohoku J Exp

Med. 228:17–61. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Fensterl V and Sen GC: The ISG56/IFIT1

gene family. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 31:71–78. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Vareille M, Kieninger E, Edwards MR and

Regamey N: The airway epithelium: Soldier in the fight against

respiratory viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 24:210–219. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sanders CJ, Doherty PC and Thomas PG:

Respiratory epithelial cells in innate immunity to influenza virus

infection. Cell Tissue Res. 343:13–21. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Shiratori T, Imaizumi T, Hirono K,

Kawaguchi S, Matsumiya T, Seya K and Tasaka S: ISG56 is involved in

CXCL10 expression induced by TLR3 signaling in BEAS-2B bronchial

epithelial cells. Exp Lung Res. 46:195–202. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yu M, Tong JH, Mao M, Kan LX, Liu MM, Sun

YW, Fu G, Jing YK, Yu L, Lepaslier D, et al: Cloning of a gene

(RIG-G) associated with retinoic acid-induced differentiation of

acute promyelocytic leukemia cells and representing a new member of

a family of interferon-stimulated genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

94:7406–7411. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhou X, Michal JJ, Zhang L, Ding B, Lunney

JK, Liu B and Jiang Z: Interferon induced IFIT family genes in host

antiviral defense. Int J Biol Sci. 9:200–208. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chikhalya A, Dittmann M, Zheng Y, Sohn SC,

Rice CM and Hearing P: Human IFIT3 protein induced interferon

signaling and inhibits adenovirus immediate early gene expression.

mBio. 12:e02829212021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Imaizumi T, Tanaka H, Matsumiya T, Yoshida

H, Tanji K, Tsuruga K, Oki E, Aizawa-Yashiro T, Ito E and Satoh K:

Retinoic acid-inducible gene-I is induced by double-stranded RNA

and regulates the expression of CC chemokine ligand (CCL) 5 in

human mesangial cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 25:3534–3539. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Schmittgen TD and Livak KJ: Analyzing

real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc.

3:1101–1108. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kanda Y: Investigation of the freely

available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone

Marrow Transplant. 48:452–458. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Schoggins JW, Wilson SJ, Panis M, Murphy

MY, Jones CT, Bieniasz P and Rice CM: A diverse range of gene

products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response.

Nature. 472:481–485. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Muzio M, Bosisio D, Polentarutti N,

D'amico G, Stoppacciaro A, Mancinelli R, van't Veer C, Penton-Rol

G, Ruco LP, Allavena P and Mantovani A: Differential expression and

regulation of toll-like receptors (TLR) in human leukocytes:

Selective expression of TLR3 in dendritic cells. J Immunol.

164:5998–6004. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Matsumoto M, Kikkawa S, Kohase M, Miyake K

and Seya T: Establishment of a monoclonal antibody against human

Toll-like receptor 3 that blocks double-stranded RNA-mediated

signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 293:1364–1369. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Cario E and Podolsky DK: Differential

alteration in intestinal epithelial cell expression of toll-like

receptor 3 (TLR3) and TLR4 in inflammatory bowel disease. Infect

Immun. 68:7010–7017. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lai Y, Yi G, Chen A, Bhardwaj K, Tragesser

BJ, Valverde RA, Zlotnick A, Mukhopadhyay S, Ranjith-Kumar CT and

Kao CC: Viral double-strand RNA-binding proteins can enhance innate

immune signaling by toll-like Receptor 3. PLoS One. 6:e258372011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Matsumoto M and Seya T: TLR3: Interferon

induction by double-stranded RNA including poly(I:C). Adv Drug

Deliv Rev. 60:805–812. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhang SY, Herman M, Ciancanelli MJ, Pérez

de Diego R, Sancho-Shimizu V, Abel L and Casanova JL: TLR3 immunity

to infection inmice and humans. Curr Opin Immunol. 25:19–33. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Imaizumi T, Yoshida H, Hayakari R, Xing F,

Wang L, Matsumiya T, Tanji K, Kawaguchi S, Murakami M and Tanaka H:

Interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) 60, as well as ISG56 and ISG54,

positively regulates TLR3/IFN-β/STAT1 axis in U373MG human

astrocytoma cells. Neurosci Res. 105:35–41. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Imaizumi T, Sassa N, Kawaguchi S,

Matsumiya T, Yoshida H, Seya K, Shiratori T, Hirono K and Tanaka H:

Interferon-stimulated gene 60 (ISG60) constitutes a negative

feedback loop in the downstream of TLR3 signaling in hCMEC/D3

cells. J Neuroimmunol. 324:16–21. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Liu M, Guo S, Hibbert JM, Jain V, Singh N,

Wilson NO and Stiles JK: CXCL10/IP-10 in infectious diseases

pathogenesis and potential therapeutic implications. Cytokine

Growth Factor Rev. 22:121–130. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Dwinell MB, Lugering N, Eckmann L and

Kangnoff MF: Regulated production of interferon-inducible T-cell

chemoattractants by human intestinal epithelial cells.

Gastroenterology. 120:49–59. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Frangogiannis NG, Mendoza LH, Smith CW,

Michael LH and Entman ML: Induction of the synthesis of the C-X-C

chemokine interferon-gamma-inducible protein-10 in experimental

canine endotoxemia. Cell Tissue Res. 302:365–376. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hayney MS, Henriquez KM, Barnet JH, Ewers

T, Champion HM, Flannery S and Barrett B: Serum IFN-γ-induced

protein 10 (IP-10) as a biomarker for severity of acute respiratory

infection in healthy adults. J Clin Virol. 90:32–37. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Schmeisser H, Mejido J, Balinsky CA,

Morrow AN, Clark CR, Zhao T and Zoon KC: Identification of alpha

interferon-induced genes associated with antiviral activity in

Daudi cells and characterization of IFIT3 as a novel antiviral

gene. J Virol. 84:10671–10680. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Blatch GL and Lässle M: The

tetratricopeptide repeat: A structural motif mediating

protein-protein interactions. Bioessays. 21:932–939. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Diamond MS and Farzan M: The

broad-spectrum antiviral functions of IFIT and IFITM proteins. Nat

Rev Immunol. 13:46–57. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Tang Y, Liu J, Zhang D, Xu Z, Ji J and Wen

C: Cytokine storm in COVID-19: The current evidence and treatment

strategies. Front Immunol. 11:17082020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|