Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) predicts that

lung cancer will become the leading cause of death not only among

cancers, but also all diseases by 2060 (1). The most common type of epithelial lung

cancer is non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), including lung

adenocarcinoma (LADC), which accounts for ~85% of all lung cancer

diagnoses (2). Although our

understanding of the epidemiology of lung cancer and the

development of strategies for its prevention have advanced in the

past 10 years, it is still the primary cause of cancer-related

death regardless of sex and age (3). The diagnosis of lung cancer in its

early stages continues to be a challenge because numerous

techniques and methodologies currently in use, such as low-dose CT,

X-rays, sputum examinations, bronchoscopy and lung tissue biopsies,

are often only effective at detecting cancer in its advanced stage

(4).

NSCLC exhibits a complex genomic landscape, with

various genetic and epigenetic mechanisms being implicated in its

development, and it has diverse genomic alterations (5). Tumor protein p53 and LDL receptor

related protein 1B mutations are prevalent across all subtypes of

NSCLC. However, LADC shows higher rates of somatic mutations in

genes, such as Kirsten rat sarcoma (RAS) viral oncogene homolog,

EGFR, Kelch-like ECH associated protein 1, serine/threonine kinase

11, mesenchymal epithelial transition factor receptor, V-Raf murine

sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, human

EGFR2, Ret proto-oncogene and Ros proto-oncogene 1, receptor

tyrosine kinase. These mutations primarily affect the RAS-MAPK

kinase-ERK, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase

catalytic subunit alpha-mTOR and MAPK pathways (6–10).

Epigenetic changes, including DNA methylation, are

present in all human cancers and contribute not only to the

initiation, but also the progression of diseases, particularly

cancer (11). Hypermethylation

silences critical tumor suppressor genes or regulatory regions

within the genome. This silencing may lead to the dysregulation of

cell proliferation or modify responses to cancer therapy (12).

The hypermethylation of numerous genes has been

reported in numerous cases of lung cancer, with the majority being

detected in promoter sequences (13,14).

Genes such as cyclin-dependent kinase-2, adenomatous polyposis

coli, cadherin-13, p16 (also known as cyclin-dependent kinase

inhibitor 2A) and Ras-association domain family protein1 isoform A

are hypermethylated, and this methylation has been linked to a

higher likelihood of relapse after the surgical resection of stage

I NSCLC (15,16). Previous studies by our group

revealed that the hypermethylation of the glutamate decarboxylase 1

and dipeptidyl protease-like 6 genes was associated with poor

outcomes in patients with LADC (17,18).

Therefore, DNA methylation may contribute to the development of

biomarkers to detect cancer in the early stages and predict patient

outcomes.

In a previous study by our group, the paired

tumorous and non-tumorous tissues of 12 LADC samples were subjected

to genome-wide screening for aberrantly methylated CpG islands

(CGIs), and the top 10 significantly methylated genes were listed,

including zinc finger protein (ZNF)577 (19). Individual gene studies were then

performed to examine the methylation and expression of ZNF577 and

their relationships with the clinical characteristics of patients.

However, only a small number of studies have examined ZNF577,

particularly in lung cancer (13),

and therefore, further research is needed.

ZNF577 belongs to the Krüppel-associated box (KRAB)

C2H2-type ZNF family (20). ZNFs have a crucial role in the

regulation of gene transcription (21,22).

While the specific function of ZNF577 remains unclear and requires

further investigation, other individual ZNFs are frequently

subjected to hypermethylation and subsequent silencing in various

types of tumors. These findings indicate that the disrupted

epigenetic pathway involving ZNFs is a common occurrence in cancer

progression (22).

Numerous studies have recognized specific ZNFs as

potential tumor suppressors that are responsible for controlling

cellular proliferation through the inhibition of MAPK signaling and

the repression of various oncogenes (23). Oxidative stress is a potential

mechanism contributing to the hypermethylation of ZNFs during

malignant transformation because it disrupts the interaction

between CCCTC-binding factor and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1,

consequently leading to increases in DNA methylation (24).

To assess the potential of ZNF577 as a

prognostic marker for LADC, the present study set out to

investigate its DNA methylation, gene expression and tissue

expression in resected LADC tissues.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue samples

The present study was conducted using a

retrospective, observational design. A total of 149 LADC tumor

samples and 27 paired tumor-matched normal lung tissue samples were

acquired from patients surgically treated at Tokushima University

Hospital (Tokushima, Japan) between April 1999 and November 2013.

Tissue samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored

at −80°C for the later extraction of DNA and RNA. All samples were

subjected to an IHC analysis to detect tissue expression of ZNF577.

Of the 149 samples, 73 tumor and 27 paired tumor-matched samples

were examined by methylation analysis and reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q)PCR. The 7th edition of the

tumor-nodes-metastasis classification for lung cancer was used to

grade the stages of tumors in samples (25). Tumors were also categorized

according to the predominant histological subtype proposed by the

2015 WHO classification (26). A

total of 162 patients with LADC were followed up for a mean

duration of 48 months (range, 0.6–147 months). Recurrence was

detected in 45 patients (27.8%) and there were 34 deaths (21.0%).

The patients' age ranged from 43 to 84 years, with a median age of

66 years.

The present study was approved by The Ethics

Committee of the University of Tokushima (Tokushima University

Hospital, Tokushima, Japan; approval no. 4071-1) and procedures

were performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of

Helsinki. Written informed consent, which included the key elements

of a research study and what their participation will involve, was

obtained from all patients.

Global methylation analysis

In a previous study by our group to detect

aberrantly methylated CGIs in a genome-wide manner (18), 12 paired tumorous/non-tumorous LADC

sample sets from freshly frozen specimens were screened using the

Illumina HumanMethylation450 K Bead Chip (Illumina, Inc.). The

findings obtained revealed 17 differentially hypermethylated CGI

sites in the ZNF577 gene. The false discovery rate was

<0.05 and the β difference (tumor vs. non-tumorous tissue) was

>0.22. CGI sites in ZNF577 ranked 3rd amongst

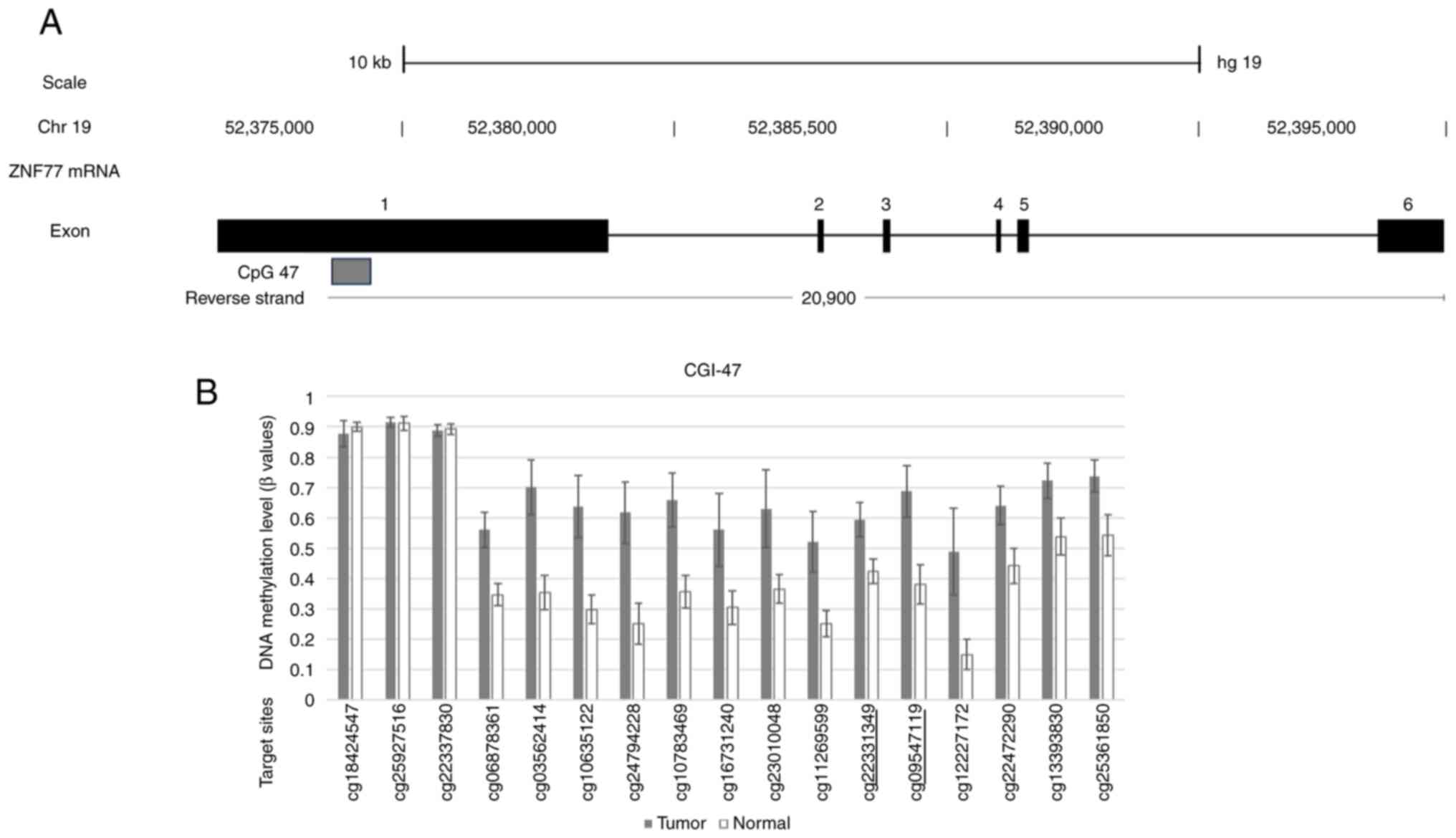

differentially methylated CGIs with a low P-value. Fig. 1A shows a schematic of the mRNA

structure of ZNF577. Among the 6 (4 coding and 2 non-coding)

exons of ZNF577 mRNA, CGIs were located around exon 1. The

array-based methylation status of each CpG site within

ZNF577 is shown in Fig. 1B.

Two DNA methylation sites in CpG47 of the ZNF577 gene,

cg09547119 and cg22331349, which were underlined, were subsequently

analyzed.

Nucleic acid isolation

The QIAamp DNA Mini Kitand RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen

GmbH) were used to isolate DNA and RNA from frozen tissue,

respectively, using the protocols described by the

manufacturer.

Bisulfite conversion and

pyrosequencing

The EpiTect Bisulfite Kit 48 (Qiagen GmbH) was used

to convert genomic DNA to bisulfite according to the manufacturer's

protocols. Prior to pyrosequencing, the PyroMark PCR-Kit 200

(Qiagen GmbH) was used according to the manufacturer's protocols to

amplify the transformed DNA by PCR using the following primers:

Forward, 5′-GGGAAGTTTGTTGGGAGTAGTTAT-3′ and reverse,

(Biotin)-5′-ATATTACAAAACCAAAATCTAACAATTCAC-3′ (target sequence

before bisulfite treatment: Forward,

5′-CCTACTGCCGTAGAGCAGGCGGAGTCCCTCTTTTCGCGCCTTAGACAGGTTCTG A-3′ and

reverse,

3′-CCTACTACTGCCGTAGAGCAGGCGGAGTCCCTCTTTTCGCGCCTTAAGACAGGTAGGTTCTGA-5′).

The ZNF577 PyroMark Custom Assay Design 2.0 (Qiagen

GmbH) was employed to develop the following sequencing primer

according to the manufacturer's intstructuions:

5′-GTTGGGAGTAGTTATTTTTAAT-3′.

In order to assess the mean methylation rate of CpG

sites, pyrosequencing was conducted using PSQ 96MA (Qiagen GmbH)

according to the manufacturer's protocols. PyroQ-CpG 1.0.9 was used

to calculate the methylation rate at each CpG.

RT-qPCR

iScript™ Reverse Transcription Supermix

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) was used for RT. Real-time PCR was

conducted with SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR® Green

Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and the PrimePCR™

SYBR® Green Assay (cat. no. 10025716; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.) for ZNF577 and GAPDH (cat. no. 10025637;

Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The internal control gene was

GAPDH. All the reagents were used and reactions were

performed according to the manufacturer's protocols. The

quantification of qPCR data was performed according the

2−ΔΔCq method (27).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC staining was performed on paraffin-embedded

sections using anti-ZNF577 rabbit polyclonal antibodies (cat. no.

HPA046761; 1:50 dilution; Atlas Antibodies) overnight at 4°C. The

tissue samples were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with

EnVision + Dual Link System-HRP secondary antibody (cat. no. K4063;

Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Antigen retrieval was conducted

by heating dewaxed and dehydrated sections in Dako Real Target

Retrieval Solution (Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.), pH 9 at 98°C

for 30 min. A total of 149 tumor samples were analyzed, excluding

positive control and normal tissues. IHC images were evaluated and

grouped as follows: Negative (intensity: Not stained or weakly

stained in a small area) or positive (intensity: Moderate to strong

with ≥30% area).

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between paired samples, when data were

and were not normally distributed, were performed using the paired

t-test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, respectively. The

relationships between methylation and mRNA expression levels and

clinical characteristics, including tumor stage, histological

patterns, smoking history, blood vessel invasion, lymph vessel

invasion, pleural invasion and lymph node metastasis, were

investigated using the unpaired t-test for normally distributed

data and the Mann-Whitney U-test for data that were not normally

distributed. One-way analysis of variance was employed for

multiple-group comparisons and was followed by Tukey's

multiple-comparisons test for normally distributed data and the

Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple-comparisons test

for non-normally distributed data. Overall survival (OS) and

disease-free survival (DFS) rates were compared between high/low

methylation, high/low mRNA expression and ZNF577 negative/positive

expression using Kaplan-Meier analysis with the log-rank

(Mantel-Cox) test. Cut-off values were selected from receiver

operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Multivariate survival

analyses were performed using the likelihood ratio test of the

stratified Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. GraphPad

Prism version 5.00 (GraphPad; Dotmatics) and SPSS (version 24.0;

IBM Corp.) were used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

Table I shows the

clinical characteristics of the 73 patients with LADC examined by

PCR and methylation analysis, including survival data, and their

basic characteristics, such as sex (male, 52%; female, 47.9%), age

at diagnosis (66.3±9.7 years; range, 43–84 years). The clinical

characteristics of the 149 patients with LADC evaluated by IHC,

including survival data, and their basic characteristics, such as

sex (male, 45%; female, 55%), age at diagnosis (66.9±9.1 years;

range, 43–84 years) are provided in Table SI.

| Table I.Patient characteristics (n=73). |

Table I.

Patient characteristics (n=73).

| Item | Value |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

Male | 38 (52.0) |

|

Female | 35 (47.9) |

| Age, years | 66.3±9.7 (43–84) |

| Smoking status |

|

|

Non-smoker | 36 (49.3) |

|

Smoker | 37 (50.6) |

| Brinkman

indexa | 381.3±501.8 |

| Pathology |

|

|

Lepidic | 26 (35.6) |

|

Papillary | 26 (35.6) |

|

Solid | 3 (4.1) |

|

Acinar | 5 (6.8) |

| Mixed

or others | 13 (17.8) |

| Surgery |

|

|

Pneumonectomy | 1 (1.36) |

|

Lobectomy | 68 (93.1) |

|

Segmentectomy | 1 (1.36) |

|

Lobectomy + segmentectomy | 3 (4.1) |

|

Complete resection | 73 (100) |

| Preoperative

chemotherapy | 1 (1.4) |

| Postoperative

chemotherapy | 20 (27.4) |

|

Cisplatin-based | 6 |

|

UFT | 13 |

|

Other | 1 |

| Pathological

stageb |

|

| IA | 38 (52.1) |

| IB | 20 (27.4) |

|

IIA | 9 (12.3) |

|

IIB | 4 (5.5) |

|

III | 2 (2.7) |

| pN factor |

|

| 0 | 65 (89.0) |

| 1 | 6 (8.2) |

| 2 | 2 (2.7) |

| Pl

factor-positive | 14 (19.1) |

| V factor-positive

(n=72) | 12 (16.6) |

| Ly

factor-positive | 12 (16.4) |

| EGFR mutation

(n=25) | 11 (44) |

ZNF577 methylation and mRNA expression

levels in LADC tissues and paired normal tissues

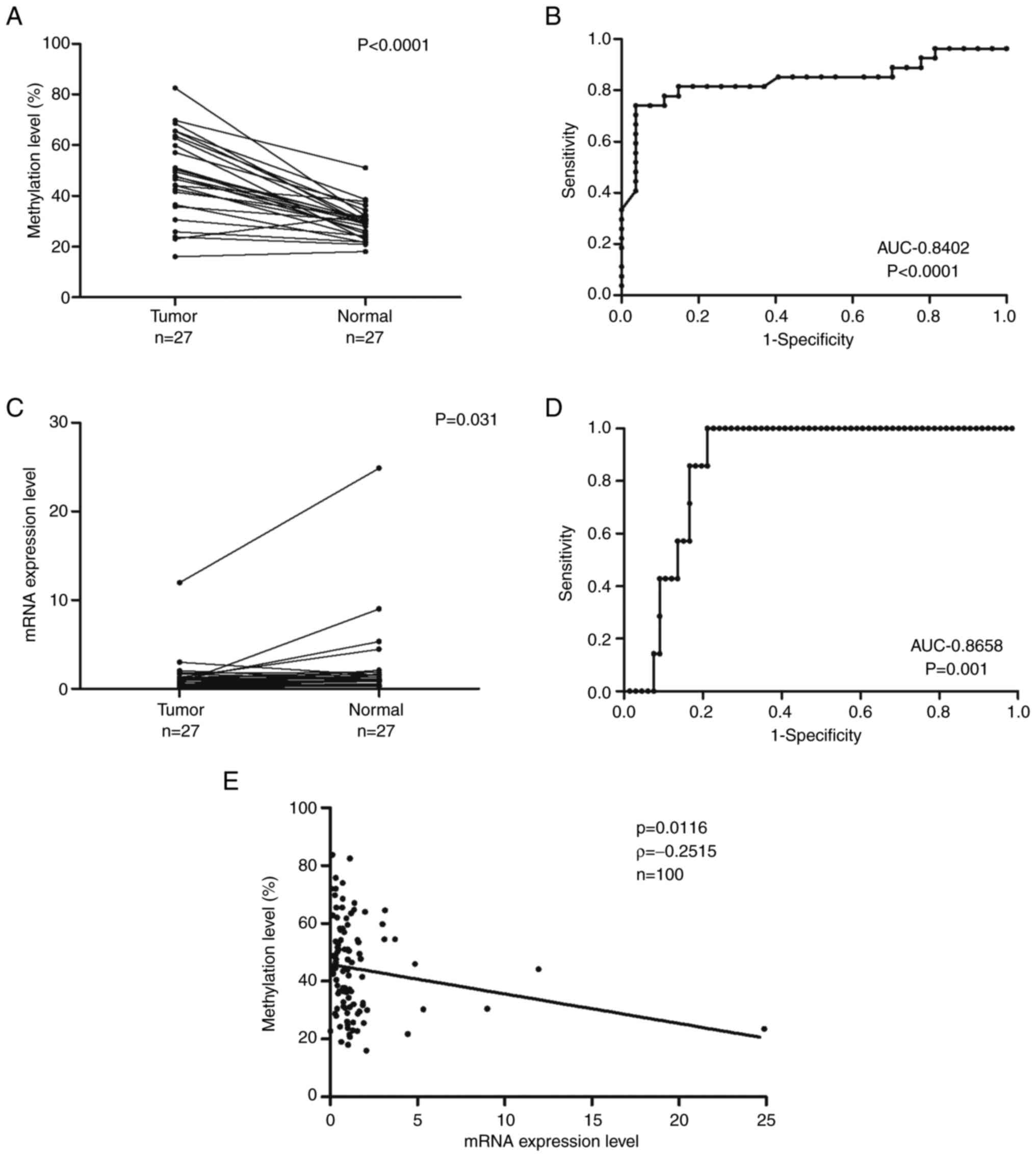

ZNF577 methylation and mRNA expression levels

in LADC tissues were assessed in comparison with 27 matched

samples. ZNF577 methylation levels in LADC and normal lung

tissues are presented in Fig. 2A.

Tumor samples had significantly higher DNA methylation levels than

normal samples (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P<0.0001). ROC curves

were used to evaluate the ability of ZNF577 methylation levels and

mRNA expression levels to discriminate tumor tissue from non-tumor

tissue. Fig. 2B presents the ROC

for methylation levels between tumor and normal samples with an

area under the curve (AUC) of 0.8402. ZNF577 mRNA expression

levels in LADC and normal lung tissues are shown in Fig. 2C. Tumor samples had significantly

lower mRNA expression levels than normal samples (Wilcoxon

signed-rank test, P<0.031). Fig.

2D shows the ROC for ZNF577 mRNA expression levels in

tumor and normal samples with an AUC of 0.8658.

Spearman's rank correlation analysis was used to

investigate the relationship between ZNF577 DNA methylation

and mRNA expression levels in 100 samples (73 tumors and 27 normal

tissues) (Fig. 2E). The results

obtained showed that methylation levels were inversely correlated

with mRNA expression levels (P=0.0116, ρ=−0.2515).

Relationship between ZNF577

methylation and mRNA expression levels and clinical characteristics

of patients with LADC

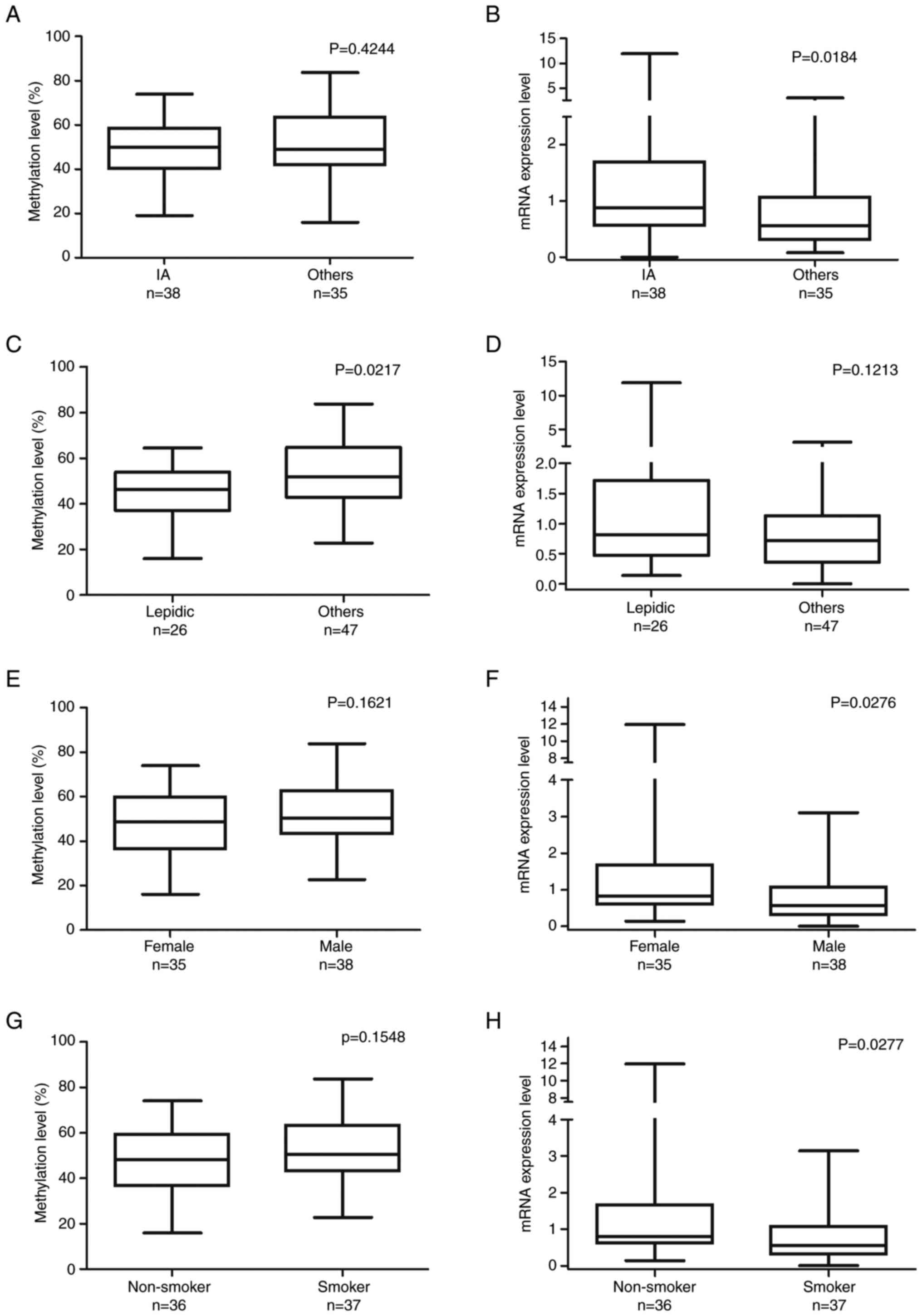

To establish whether the malignancy and progression

of LADC were affected by the hypermethylation of ZNF577, the

methylation and mRNA expression levels were measured in 73 samples

and compared with histology patterns and stage grading.

The IA group had slightly lower ZNF577

methylation levels than the other, advanced-stage groups but it was

not statistically significant. Furthermore, the IA group had

significantly higher ZNF577 mRNA expression levels

(Mann-Whitney U-test, P=0.0184; Fig. 3A

and B). Samples with the lepidic pattern had significantly

lower ZNF577 methylation levels than those with the other

patterns (unpaired t-test, P=0.0217; Fig. 3C). However, ZNF577 mRNA

expression levels did not significantly differ between samples with

the lepidic and other histological patterns (Mann-Whitney U-test;

Fig. 3D).

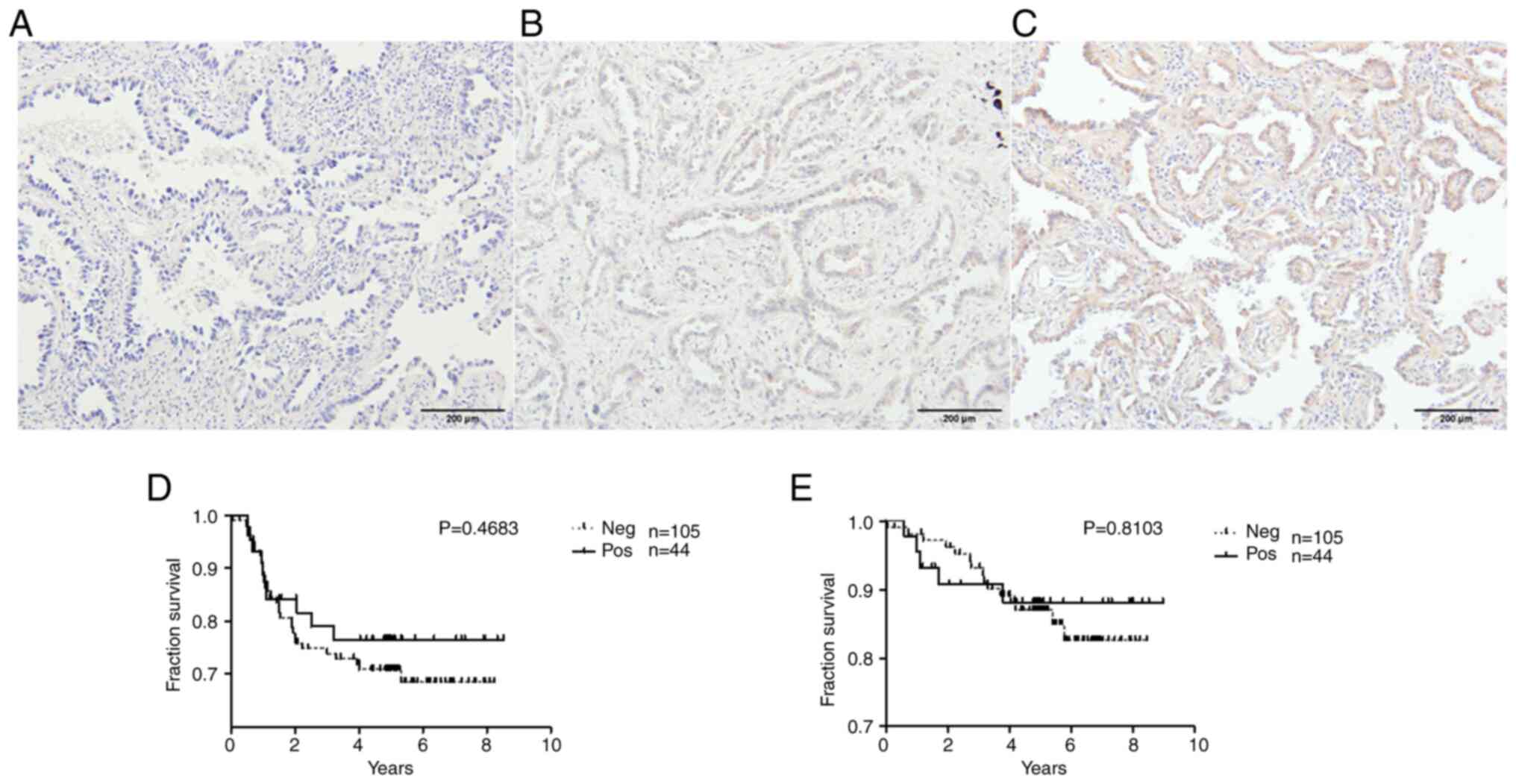

| Figure 3.Comparison of ZNF577 DNA methylation

and mRNA expression levels with patient characteristics. ZNF577

methylation and mRNA expression levels were analyzed in lung

adenocarcinoma tumor samples (n=73) using pyrosequencing and

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR, respectively. (A) ZNF577

methylation (%) and (B) mRNA expression levels in lung cancer

stages categorized by the World Health Organization histological

classification (IA, n=38; others: IB, n=21; IIA, n=9; IIB, n=4;

IIIA, n=1). (C) ZNF577 methylation (%) and (D) mRNA expression

levels in lung cancer with different histological patterns

(lepidic, n=26; others: Papillary, n=26; acinar, n=5; solid, n=3;

mixed, n=13). (E) ZNF577 methylation (%) and (F) mRNA expression

levels according to sex. (G) ZNF577 methylation (%) and (H) mRNA

expression levels according to smoking status. ZNF, zinc finger

protein. |

To examine differences in the hypermethylation and

mRNA expression levels of ZNF577 between the sexes and

individuals with different smoking statuses, methylation and mRNA

expression levels were assessed in 73 samples. ZNF577

methylation levels were slightly lower in females (unpaired t-test,

P=0.1621) and non-smokers (unpaired t-test, P=0.1548; Fig. 3E and F) but the differences were not

statistically significant. However, mRNA expression levels of

ZNF577 were significantly higher in females (Mann-Whitney

U-test, P=0.0276) and non-smokers (Mann-Whitney U-test, P=0.0277;

Fig. 3G and H).

Prognostic value of mRNA expression

and methylation levels of the ZNF577 gene in LADC

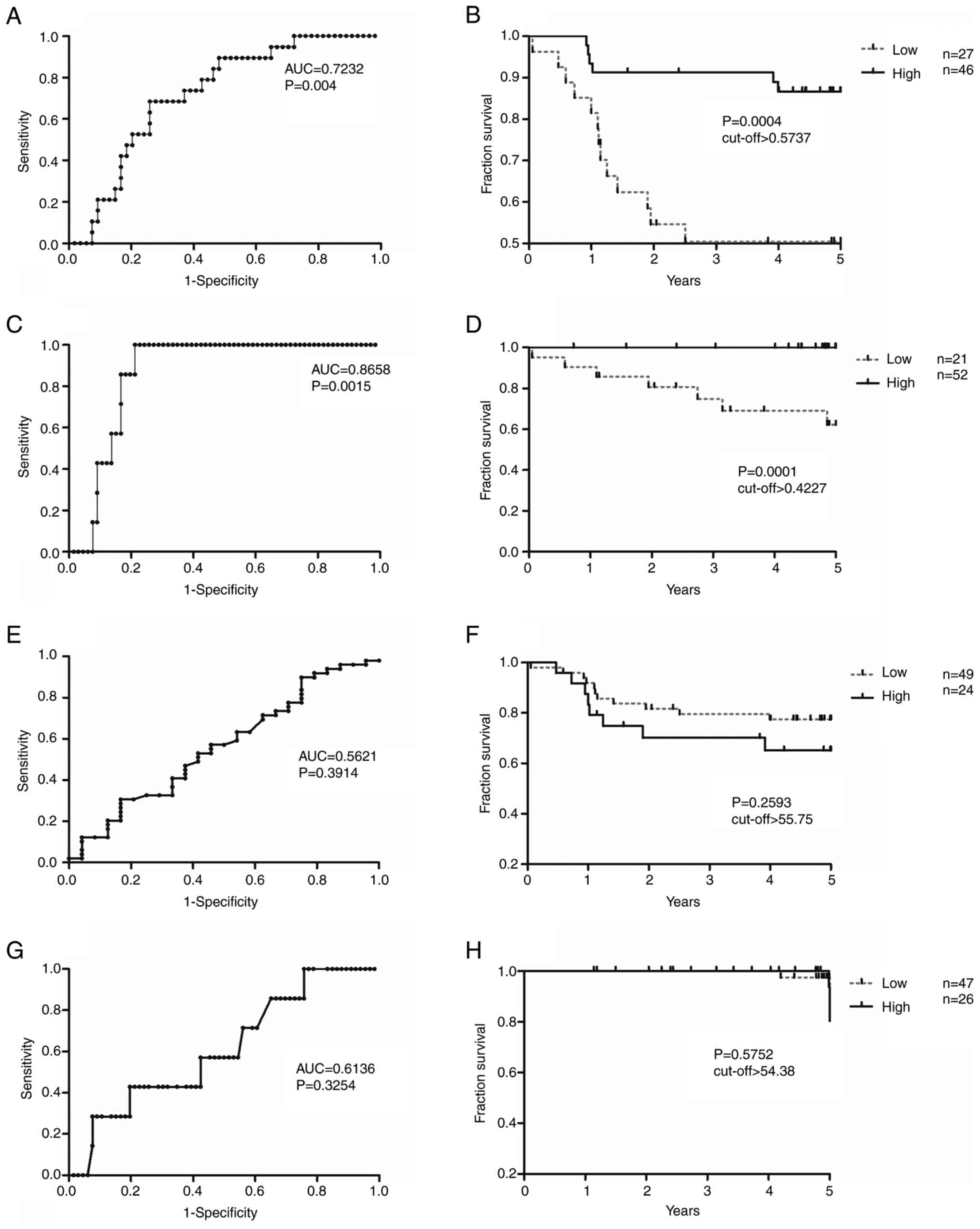

DFS and OS analyses of ZNF577 mRNA expression

and methylation levels were conducted (Fig. 4). Cut-off values obtained from ROC

curves were used to divide samples into those with high/low

expression and high/low methylation levels (Fig. 4A, C, E and G). Samples with high

ZNF577 mRNA expression levels had significantly higher DFS

and OS rates than those with low levels [DFS: Area under the ROC

curve (AUC)=0.7232; log-rank P=0.0004; cut-off value, 0.5737; and

OS: AUC=0.8658; log-rank P=0.0001; cut-off value, 0.4227; Fig. 4A-D]. However, no significant

differences were observed in DFS or OS between samples with high

and low ZNF577 methylation levels (DFS: Log-rank P=0.2593;

cut-off value, 55.75; and OS: Log-rank P=0.5752; cut-off value,

54.38) (Fig. 4E-H).

In the multivariate Cox regression analysis, ZNF577

mRNA expression levels [hazard ratio (HR): 3.917; 95% CI:

1.212–12.66; P=0.023], tumor stage (IA vs. others; HR: 0.159; 95%

CI: 0.041–0.612; P=0.007), smoking status (HR: 13.740: 95% CI:

1.778–106.1; P=0.012) and lymphovascular invasion (No vs. Yes; HR:

0.180; 95% CI: 0.037–0.888; P=0.035) were identified as independent

prognostic factors for DFS (Table

IIA). Patient age (HR: 0.022; 95% CI: 0.001–0.667; P=0.028),

tumor stage IA vs. others; HR: 0.021; 95% CI: 0.000–0.960; P=0.048)

and lymphovascular invasion (No vs. Yes; HR: 0.005; 95% CI:

0.000–0.729; P=0.037) were identified as independent prognostic

factors for OS (Table IIB).

| Table II.Cox proportional hazard regression

analysis of DFS and OS in patients with lung adenocarcinoma

(n=73). |

Table II.

Cox proportional hazard regression

analysis of DFS and OS in patients with lung adenocarcinoma

(n=73).

| A, Disease-free

survival |

|---|

|

|---|

|

| Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Factor | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Sex, female (n=35)

vs. male (n=38) | 0.264 | 0.043–1.605 | 0.148 |

| Age <67 (n=43)

vs. ≥67 (n=30) years | 0.364 | 0.106–1.253 | 0.109 |

| Smoking, smoker

(n=37) vs. non-smoker (n=36) | 13.740 | 1.778–106.1 | 0.012 |

| Stagea, IA (n=38) vs. others (n=35) | 0.159 | 0.041–0.612 | 0.007 |

| Metastasis, No

(n=65) vs. Yes (n=8) | 0.270 | 0.066–1.103 | 0.068 |

| LVI, No (n=61) vs.

Yes (n=12) | 0.180 | 0.037–0.888 | 0.035 |

| Pathology, lepidic

(n=26) vs. others (n=47) | 0.894 | 0.227–3.517 | 0.873 |

| ZNF577 mRNA

expression, Low (n=37) vs. High (n=36) | 3.917 | 1.212–12.660 | 0.023 |

| ZNF577 DNA

methylation, Low (n=36) vs. High (n=37) | 0.932 | 0.336–2.580 | 0.892 |

|

| B, OS |

|

| Sex, female (n=35)

vs. male (n=38) | 0.014 | 0.000–2.048 | 0.093 |

| Age,<67 (n=43)

vs. ≥67 (n=30) years | 0.022 | 0.001–0.667 | 0.028 |

| Smoking, smoker

(n=37) vs. smoker (n=36) | 356.2 | 0.802–158303 | 0.059 |

| Stagea, IA (n=38) vs. others (n=35) | 0.021 | 0.000–0.960 | 0.048 |

| Metastasis, No

(n=65) vs. Yes (n=8) | 11.90 | 0.248–570.8 | 0.210 |

| LVI, No (n=61) vs.

Yes (n=12) | 0.005 | 0.000–0.729 | 0.037 |

| Pathology, lepidic

(n=26) vs. others (n=47) | 0.270 | 0.016–4.532 | 0.363 |

| ZNF577 mRNA

expression, Low (n=37) vs. High (n=36) | 3173475 | 0.000–2.658E+ | 0.949 |

| ZNF577 DNA

methylation, Low (n=36) vs. High (n=37) | 5.198 | 0.490–55.194 | 0.171 |

Tissue expression of ZNF577 in

LADC

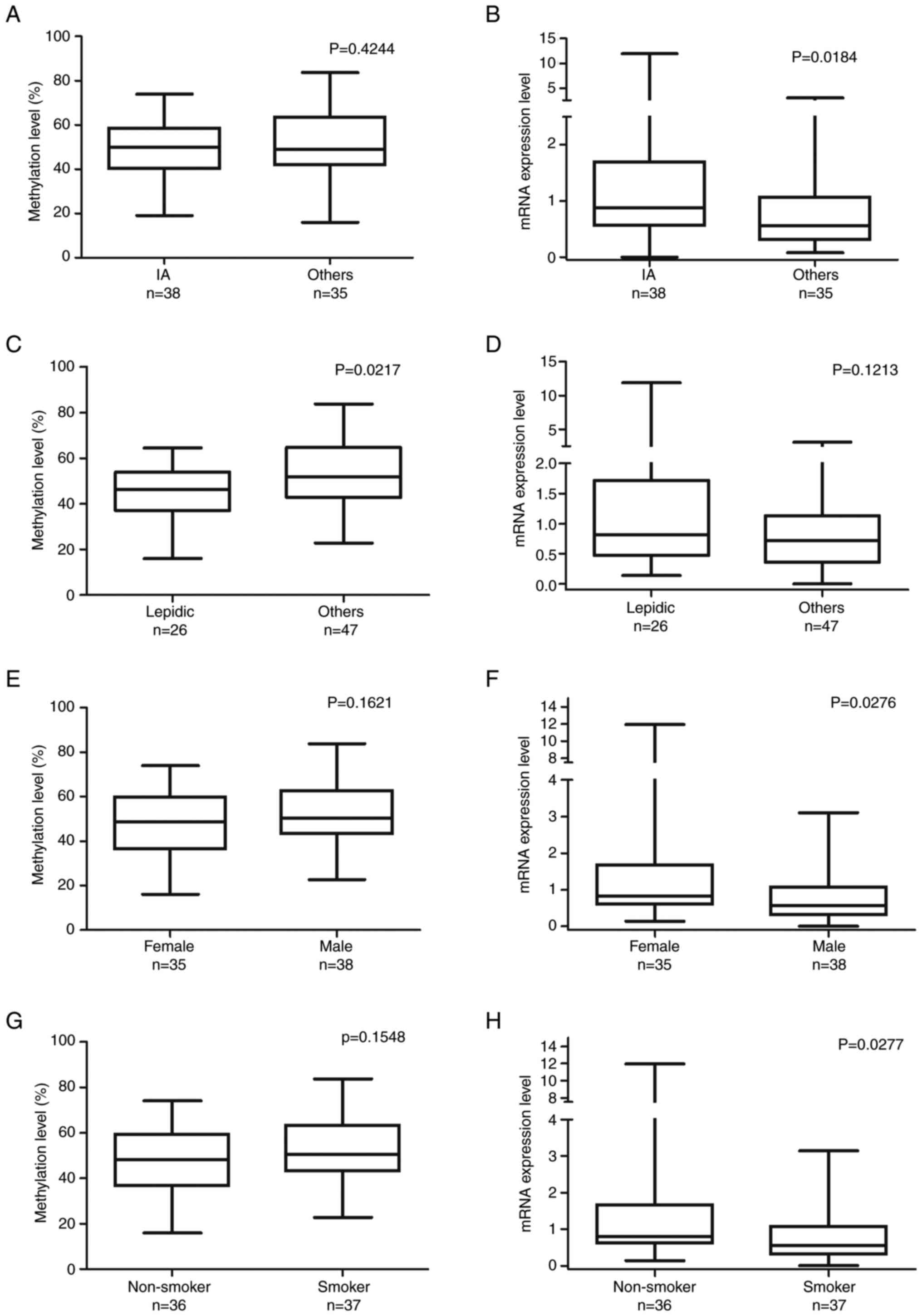

The tissue expression of ZNF577 was examined in 149

samples by IHC. In a total of 105 samples (70.5%), ZNF577 was not

expressed, while the remaining 44 (29.5%) showed positive IHC

staining. The staining indicated that the protein was located in

the cytoplasmic/membranous area. Representative images are shown in

Fig. 5A-C. In addition, the impact

of the tissue expression of ZNF577 on patient survival rates was

analyzed. Survival rates did not significantly differ (DFS:

Log-rank P=0.4683; OS: Log-rank P=0.8103) between the groups

(Fig. 5D and E).

Discussion

Methylation and gene expression analyses of the

ZNF577 gene in 73 patients with LADC were performed in the present

study. Tissue microarray was performed on 149 tumor samples to

detect ZNF577 expression in the tissue. To the best of our

knowledge, the present study was the first to report the

methylation and gene expression levels of ZNF577 and their

correlation with survival rates in patients with LADC.

In pyrosequencing and gene expression analyses,

significantly higher methylation levels and lower expression levels

of ZNF577 in tumor samples than in their matched normal tissues

were identified. The correlation analysis between the methylation

and expression of ZNF577 showed an inverse relationship, with

higher methylation levels being associated with lower expression

levels. These results confirm the property of DNA methylation that

silences or inhibits gene expression. Based on ROC curve data, the

present study revealed excellent efficiency for discriminating

between tumor and normal samples using the methylation and mRNA

levels of ZNF577. In addition, a previous study by our group

indicated that the mRNA expression level of ZNF577 was low in 10

out of 14 lung cancer cell lines. Furthermore, the demethylating

agents 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine and trichostatin effectively increased

its mRNA levels in lung cancer cell lines (19).

Rauch et al (13) identified 12 CpG islands that were

confirmed to be methylated in 85–100% of stage I lung squamous cell

carcinoma cases (n=5), including ZNF577. The group also tested

stage I LADC samples (n=8) to identify hypermethylated genes.

However, ZNF577 was not among the hypermethylated genes detected,

which may be attributed to the stage of the samples as well as the

small number of samples examined. Furthermore, certain studies

reported the hypermethylation of ZNF577 in aggressive prostate

cancer (28), breast cancer

(29,30), de-novo skin cancer (31) and polycythemia vera cases (32). On the other hand, hypomethylation

and overexpression of ZNF577 were observed in fetal alcohol

spectrum disorder (33). Based on

these studies, it may be predicted that ZNF577 is hypermethylated

in several types of tumors.

According to the present results, the mRNA

expression levels of ZNF577 were significantly higher in stage I

samples and non-smokers than in later stages and smokers. In

addition, lepidic samples had lower methylation levels of ZNF577

than advanced pathological patterns. These results clearly showed

that ZNF577 methylation and gene expression levels were affected by

sex, smoking status, cancer stage and the pathological pattern of

LADC. However, the expected (i.e., ‘high methylation-low

expression’ and ‘low methylation-high mRNA expression’) inverse

relationship between methylation and gene expression levels (i.e.,

‘high methylation-low expression’ and ‘low methylation-high mRNA

expression’), as seen in tumor vs. normal samples, was not observed

for these clinical characteristics.

The hypermethylation of ZNF577 has been associated

with obesity and post-menopause-related breast cancer (29,30).

Furthermore, higher methylation levels of ZNF577 were detected in

the leukocytes of women with breast cancer and greater adherence to

the Mediterranean diet or specific foods, such as vegetables and

fish. The present results showed that females had higher mRNA

expression levels of ZNF577 than males. However, the methylation

levels did not significantly differ between females and males. In

the present study, female patients were mostly menopausal and

post-menopausal, with ages ranging between 43 and 84 (median, 66)

years. Therefore, it was impossible to compare methylation and gene

expression levels between premenopausal and postmenopausal women in

this study. A relationship between obesity and aggressive prostate

cancer was previously reported (34). ZNF577 was hypermethylated in the

leukocytes of these patients, 49.1% of whom were obese and 36.8%

were overweight (28). Therefore, a

relationship may exist between the metabolic status and the ZNF577

methylation rate.

DNA methylation patterns are linked to a greater

likelihood of developing cancer, a worse prognosis and a lower

chance of DFS (35). A relationship

between patient survival rates and ZNF577 expression levels has not

been reported. Significantly higher OS and DFS rates in the high

ZNF577 mRNA expression group than in the low expression group were

observed. Furthermore, the prediction of both OS and DFS rates by

the high and low ZNF577 mRNA expression groups was excellent (DFS:

AUC=0.7232; log-rank P=0.0004 and OS: AUC=0.8658; log-rank

P=0.0001).

The tissue expression of ZNF577 was also assessed

and slightly higher OS and DFS rates were found in the

ZNF577-positive group than in the ZNF577-negative group. There was

no relationship between the mRNA expression level and the IHC

H-score of ZNF577 (data not shown). Numerous factors, including

post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications and

microRNAs, can influence the abundance and stability of both mRNA

and proteins. Therefore, the abundance of mRNA and the protein

level may not always correlate. This may have affected the tissue

expression of ZNF577. And another reason could be the availability

of the ZNF577 antibody. Since this gene is less studied,

particularly by IHC, immunofluorescence and western blotting, there

are only a small number of antibody options. A couple of

commercially available antibodies were tried by our group, which

generally gave relatively weak signals. Furthermore, the tissue

expression of ZNF577 was not reported in previous studies.

ZNF577 is a KRAB C2H2-type

zinc-finger protein (20). The

presence of the KRAB domain, which has a potent transcriptional

repressor property, indicates that the majority of KRAB-ZNF family

members have roles in regulating various biological processes, such

as embryonic development, cell differentiation, cell proliferation,

apoptosis, neoplastic transformation and cell cycle regulation

(36). For instance, ZNF471, ZNF382

and ZNF545 have been reported as tumor suppressor genes and are

hypermethylated in several cancer types (37–43).

ZNF577 may be regarded as a relatively new gene that

has not been reported in many studies. The hypermethylation of

ZNF577 may interfere with immune responses under conditions such as

obesity, the post-menopausal stage and all of the aforementioned

cancer cases. This may be because ZNFs have significant roles in

regulating immune responses at both the transcriptional and

post-transcriptional levels and are involved in the onset and

progression of cancer (22,44).

The present study had certain limitations that need

to be addressed. First, the sample size examined was small due to

the limited source of collected samples. Furthermore, since ZNF577

is relatively less studied, there are only a couple of commercially

available antibodies to detect ZNF577. This limits our choice to

select a suitable antibody for IHC analysis. In addition, liquid

biopsy samples of patients were not available for analysis. This

prevented us from obtaining more profound data to compare and

support the present results.

In conclusion, ZNF577 may be a candidate biomarker

for the prognosis and screening of LADC as well as a therapeutic

target. Therefore, additional studies are required to obtain a more

detailed understanding of the functional role of ZNF577,

particularly its methylation status and expression levels, in

cancer biology. ZNF577 has potential in the diagnosis and outcome

predictions of lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for

Scientific Research (grant no. 23K0829600) from the Ministry of

Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SS, KK, HTa and BM analyzed DNA methylation using

pyrosequencing and interpreted the data. SS, BM and KK analyzed

mRNA expression using RT-qPCR and interpreted the data. KK, BT, HTo

and MY performed the IHC staining and interpreted the association

between the clinical data and the immunoreactivity. KK, HTa and BM

designed and conducted the present study. KK, NK and MY performed

the histological examination of LADC tumor samples. BM, KK and BT

were major contributors in writing the manuscript. BM and KK

checked and confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed in accordance with

the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Following

the approval of all aspects of the present study by the local

Ethics Committee (Tokushima University Hospital; Tokushima, Japan;

approval no. 4071-1), formal written informed consent for the use

of their tissues and the publication of any associated data was

obtained from all patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sleeman KE, Gomes B, de Brito M, Shamieh O

and Harding R: The burden of serious health-related suffering among

cancer decedents: Global projections study to 2060. Palliat Med.

35:231–235. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Padinharayil H, Varghese J, John MC,

Rajanikant GK, Wilson CM, Al-Yozbaki M, Renu K, Dewanjee S, Sanyal

R, Dey A, et al: Non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC):

Implications on molecular pathology and advances in early

diagnostics and therapeutics. Genes Dis. 10:960–989. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bade BC and Dela Cruz CS: Lung cancer

2020: Epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med.

41:1–24. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Nooreldeen R and Bach H: Current and

future development in lung cancer diagnosis. Int J Mol Sci.

22:86612021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, .

Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature.

511:543–550. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jordan EJ, Kim HR, Arcila ME, Barron D,

Chakravarty D, Gao J, Chang MT, Ni A, Kundra R, Jonsson P, et al:

Prospective comprehensive molecular characterization of lung

adenocarcinomas for efficient patient matching to approved and

emerging therapies. Cancer Discov. 7:596–609. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER,

McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Greulich H, Muzny DM, Morgan

MB, et al: Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung

adenocarcinoma. Nature. 455:1069–1075. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Seo JS, Ju YS, Lee WC, Shin JY, Lee JK,

Bleazard T, Lee J, Jung YJ, Kim JO, Shin JY, et al: The

transcriptional landscape and mutational profile of lung

adenocarcinoma. Genome Res. 22:2109–2119. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Barbar J, Armach M, Hodroj MH, Assi S, El

Nakib C, Chamseddine N and Assi HI: Emerging genetic biomarkers in

lung adenocarcinoma. SAGE Open Med. 10:205031212211323522022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kan Z, Jaiswal BS, Stinson J, Janakiraman

V, Bhatt D, Stern HM, Yue P, Haverty PM, Bourgon R, Zheng J, et al:

Diverse somatic mutation patterns and pathway alterations in human

cancers. Nature. 466:869–873. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Jha G, Azhar S, Rashid U, Khalaf H,

Alhalabi N, Ravindran D and Ahmad R: Epigenetics: The key to future

diagnostics and therapeutics of lung cancer. Cureus.

13:e197702021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Belinsky SA, Nikula KJ, Palmisano WA,

Michels R, Saccomanno G, Gabrielson E, Baylin SB and Herman JG:

Aberrant methylation of p16(INK4a) is an early event in lung cancer

and a potential biomarker for early diagnosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 95:11891–11896. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rauch TA, Wang Z, Wu X, Kernstine KH,

Riggs AD and Pfeifer GP: DNA methylation biomarkers for lung

cancer. Tumour Biol. 33:287–296. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chao YL and Pecot CV: Targeting

epigenetics in lung cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med.

11:a0380002021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Brock MV, Hooker CM, Ota-Machida E, Han Y,

Guo M, Ames S, Glöckner S, Piantadosi S, Gabrielson E, Pridham G,

et al: DNA methylation markers and early recurrence in stage I lung

cancer. N Engl J Med. 358:1118–1128. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sterlacci W, Tzankov A, Veits L, Zelger B,

Bihl MP, Foerster A, Augustin F, Fiegl M and Savic S: A

comprehensive analysis of p16 expression, gene status, and promoter

hypermethylation in surgically resected non-small cell lung

carcinomas. J Thorac Oncol. 6:1649–1657. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Munkhjargal B, Kondo K, Soejima S, Tegshee

B, Takai C, Kawakita N, Toba H and Takizawa H: Aberrant methylation

of dipeptidyl peptidase-like 6 as a potential prognostic biomarker

for lung adenocarcinoma. Oncol Lett. 25:2062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tsuboi M, Kondo K, Masuda K, Tange S,

Kajiura K, Kohmoto T, Takizawa H, Imoto I and Tangoku A: Prognostic

significance of GAD1 overexpression in patients with resected lung

adenocarcinoma. Cancer Med. 8:4189–4199. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kajiura K, Masuda K, Naruto T, Kohmoto T,

Watabnabe M, Tsuboi M, Takizawa H, Kondo K, Tangoku A and Imoto I:

Frequent silencing of the candidate tumor suppressor TRIM58 by

promoter methylation in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma.

Oncotarget. 8:2890–2905. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cards G: ZNF577 gene-zinc finger protein

577. Weizmann Institute of Science, 2024. https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=ZNF577#domains_families

|

|

21

|

Tan W, Zheng L, Lee WH and Boyer TG:

Functional dissection of transcription factor ZBRK1 reveals zinc

fingers with dual roles in DNA-binding and BRCA1-dependent

transcriptional repression. J Biol Chem. 279:6576–6587. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Jen J and Wang YC: Zinc finger proteins in

cancer progression. J Biomed Sci. 23:532016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sobocińska J, Molenda S, Machnik M and

Oleksiewicz U: KRAB-ZFP transcriptional regulators acting as

oncogenes and tumor suppressors: An overview. Int J Mol Sci.

22:22122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Severson PL, Tokar EJ, Vrba L, Waalkes MP

and Futscher BW: Coordinate H3K9 and DNA methylation silencing of

ZNFs in toxicant-induced malignant transformation. Epigenetics.

8:1080–1088. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, Giroux

DJ, Groome PA, Rami-Porta R, Postmus PE, Rusch V and Sobin L;

International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer

International Staging Committee; Participating Institutions, : The

IASLC lung cancer staging project: Proposals for the revision of

the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the

TNM classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2:706–714.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A

and Nicholson AG: Introduction to the 2015 World Health

Organization classification of tumors of the lung, pleura, thymus,

and heart. J Thorac Oncol. 10:1240–1242. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Xu Y, Tsai CW, Chang WS, Han Y, Huang M,

Pettaway CA, Bau DT and Gu J: Epigenome-wide association study of

prostate cancer in African Americans identifies DNA methylation

biomarkers for aggressive disease. Biomolecules. 11:18262021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lorenzo PM, Izquierdo AG, Diaz-Lagares A,

Carreira MC, Macias-Gonzalez M, Sandoval J, Cueva J, Lopez-Lopez R,

Casanueva FF and Crujeiras AB: ZNF577 methylation levels in

leukocytes from women with breast cancer is modulated by adiposity,

menopausal state, and the mediterranean diet. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 11:2452020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Crujeiras AB, Diaz-Lagares A, Stefansson

OA, Macias-Gonzalez M, Sandoval J, Cueva J, Lopez-Lopez R, Moran S,

Jonasson JG, Tryggvadottir L, et al: Obesity and menopause modify

the epigenomic profile of breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer.

24:351–363. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Peters FS, Peeters AMA, Mandaviya PR, van

Meurs JBJ, Hofland LJ, van de Wetering J, Betjes MGH, Baan CC and

Boer K: Differentially methylated regions in T cells identify

kidney transplant patients at risk for de novo skin cancer. Clin

Epigenetics. 10:812018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Barrio S, Gallardo M, Albizua E, Jiménez

A, Rapado I, Ayala R, Gilsanz F, Martin-Subero JI and

Martinez-Lopez J: Epigenomic profiling in polycythaemia vera and

essential thrombocythaemia shows low levels of aberrant DNA

methylation. J Clin Pathol. 64:1010–1013. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Krzyzewska IM, Lauffer P, Mul AN, van der

Laan L, Yim AYFL, Cobben JM, Niklinski J, Chomczyk MA, Smigiel R,

Mannens MMAM and Henneman P: Expression quantitative trait

methylation analysis identifies whole blood molecular footprint in

fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). Int J Mol Sci. 24:66012023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Allott EH, Masko EM and Freedland SJ:

Obesity and prostate cancer: Weighing the evidence. Eur Urol.

63:800–809. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hill VK, Ricketts C, Bieche I, Vacher S,

Gentle D, Lewis C, Maher ER and Latif F: Genome-wide DNA

methylation profiling of CpG islands in breast cancer identifies

novel genes associated with tumorigenicity. Cancer Res.

71:2988–2999. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Lupo A, Cesaro E, Montano G, Zurlo D, Izzo

P and Costanzo P: KRAB-zinc finger proteins: A repressor family

displaying multiple biological functions. Curr Genomics.

14:268–278. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Cao L, Wang S, Zhang Y, Wong KC, Nakatsu

G, Wang X, Wong S, Ji J and Yu J: Zinc-finger protein 471

suppresses gastric cancer through transcriptionally repressing

downstream oncogenic PLS3 and TFAP2A. Oncogene. 37:3601–3616. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Sun R, Xiang T, Tang J, Peng W, Luo J, Li

L, Qiu Z, Tan Y, Ye L, Zhang M, et al: 19q13 KRAB zinc-finger

protein ZNF471 activates MAPK10/JNK3 signaling but is frequently

silenced by promoter CpG methylation in esophageal cancer.

Theranostics. 10:2243–2259. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tao C, Luo J, Tang J, Zhou D, Feng S, Qiu

Z, Putti TC, Xiang T, Tao Q, Li L and Ren G: The tumor suppressor

zinc finger protein 471 suppresses breast cancer growth and

metastasis through inhibiting AKT and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Clin

Epigenetics. 12:1732020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Bhat S, Kabekkodu SP, Adiga D, Fernandes

R, Shukla V, Bhandari P, Pandey D, Sharan K and Satyamoorthy K:

ZNF471 modulates EMT and functions as methylation regulated tumor

suppressor with diagnostic and prognostic significance in cervical

cancer. Cell Biol Toxicol. 37:731–749. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Bhat S, Kabekkodu SP, Jayaprakash C,

Radhakrishnan R, Ray S and Satyamoorthy K: Gene promoter-associated

CpG island hypermethylation in squamous cell carcinoma of the

tongue. Virchows Arch. 470:445–454. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Cheng Y, Geng H, Cheng SH, Liang P, Bai Y,

Li J, Srivastava G, Ng MH, Fukagawa T, Wu X, et al: KRAB zinc

finger protein ZNF382 is a proapoptotic tumor suppressor that

represses multiple oncogenes and is commonly silenced in multiple

carcinomas. Cancer Res. 70:6516–6526. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cheng Y, Liang P, Geng H, Wang Z, Li L,

Cheng SH, Ying J, Su X, Ng KM, Ng MH, et al: A novel 19q13

nucleolar zinc finger protein suppresses tumor cell growth through

inhibiting ribosome biogenesis and inducing apoptosis but is

frequently silenced in multiple carcinomas. Mol Cancer Res.

10:925–936. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Rakhra G and Rakhra G: Zinc finger

proteins: Insights into the transcriptional and post

transcriptional regulation of immune response. Mol Biol Rep.

48:5735–5743. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|