Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the most prevalent

gynecological cancer worldwide, posing a significant threat to

women's health (1). Globally, the

primary factors contributing to OC-associated mortality include

delayed diagnosis, chemotherapy resistance, high metastasis rates

and heterogeneity (2). Despite the

ongoing development of novel targeted therapies and

chemotherapeutic drugs, the prognosis for OC remains unfavorable

due to resistance and recurrence (2). Therefore, it is imperative to explore

the pathogenic mechanisms of OC and to develop early diagnostic

indicators.

Kinesins are a class of evolutionarily conserved

motor proteins that generate motive force by hydrolyzing ATP and

binding to microtubules, thus serving an important role in various

aspects of intracellular transport and widely participating in

various physiological processes, including embryonic development,

axon transport and cell division (3). Previous studies have shown that most

kinesins are expressed at higher levels in tumors compared with

those in normal tissues (4–12). Kinesins consist of the kinesin heavy

chain and the kinesin light chain (KLC), with KLCs generally

considered to participate in cargo binding and regulation of motor

protein activity. There are four subtypes of KLCs: KLC1, KLC2, KLC3

and KLC4 (13). In lung cancer, it

has been demonstrated that KLC1, KLC2 and KLC4 are associated with

drug resistance and poor prognosis (5–7). In

OC, multiple members of the kinesin family are considered to

promote OC proliferation and migration, while being associated with

poor prognosis (8–12). However, there have been limited

reports on the pathways involved and the precise mechanisms related

to KLC3 in OC occurrence.

PI3K/AKT is an important intracellular signaling

pathway, which is involved in cell cycle regulation, proliferation,

glycation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), cancer

development, tumor recurrence and drug resistance (14). The development and application of

small molecule inhibitors targeting this pathway have shown

promising clinical efficacy (15).

Publicly available data have indicated that ~70% of patients with

OC exhibit activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway. In addition, there

is strong preclinical and clinical evidence for potent PI3K/AKT

pathway inhibitors in OC; however, there are currently no Food and

Drug Administration-approved inhibitors for the treatment of OC

(15,16).

The aim of the current study was to investigate the

expression of KLC3 in OC tissue and its role in the proliferation

and migration of OC cells.

Materials and methods

Analysis of KLC3 expression and

prognosis using online databases

The Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis

(GEPIA; http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) and Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) databases were

utilized to assess the mRNA expression levels of KLC3 in OC. The

Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) TCGA-OV data (https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga)

and the Genotype-Tissue Expression normal ovarian tissue data

(https://commonfund.nih.gov/genotype-tissue-expression-gtex)

were obtained from the GEPIA, and the GSE12470 (17) and GSE18520 (18) datasets were obtained from the GEO.

Tumor samples in all databases were not matched to normal samples,

the normal samples were from healthy individuals. Additionally, the

Kaplan-Meier plotter (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) was employed to

investigate the association between KLC3 expression and the

prognosis of patients with OC.

Clinical specimens and cell lines

Five patients with OC who underwent surgery at The

First Hospital of Lanzhou University (Lanzhou, China) between June

2022 and November 2022, along with five normal ovarian samples

(healthy controls), were collected for western blot analysis. The

average age of the healthy control group for western blotting and

IHC was 60 years old, including women aged between 55 and 62 years

old. Ovarian samples were obtained following hysterectomy for

benign gynecological diseases, such as abnormal uterine bleeding,

adenomyosis, uterine fibroids and uterine abscess. Furthermore, 48

OC tissues and 10 normal tissues collected from healthy controls

were obtained between January 2020 and January 2023 were used for

immunohistochemistry (IHC). Table I

provides the basic features of the patients, and International

Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging was used in all

patients (19). All patients were

diagnosed with OC through pathological examination and their

clinical data were recorded. None of the patients had received

targeted therapy, chemotherapy or radiotherapy prior to surgery.

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First

Hospital of Lanzhou University (approval no. LDYYLL-2019-279), and

all tissues involved in the present study were stored in the

Biobank of The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, where all

samples were stored with the consent of patients. The medical

records were available for the participants, and all participants

provided written informed consent and their samples were

anonymized. The current study was conducted in compliance with the

International Conference on Harmonization guidelines for Good

Clinical Practice (20) and the

2013 Declaration of Helsinki. The SKOV3 and A2780 human OC cell

lines used in the present study were sourced from the Cell Resource

Center, Institute of Basic Medicine, Chinese Academy of Medical

Sciences. All cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mg/ml streptomycin,

10,000 U/ml penicillin and 25 µg/ml amphotericin B (all from Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C and 5% CO2.

| Table I.Basic characteristics of

patients. |

Table I.

Basic characteristics of

patients.

| Characteristic | Number (n=48) |

|---|

| Age, years | 50.3±8.6 |

| FIGO stage |

|

|

I–II | 21 (43.7%) |

|

III–IV | 27 (56.3%) |

| Lymph node

invasion |

|

|

Yes | 16 (33.3%) |

| No | 32 (66.7%) |

| Histological

grade |

|

| G1 | 4 (8.3%) |

| G2 | 7 (14.6%) |

| G3 | 37 (77.1%) |

Cell transduction and

transfection

The lentivirus design and packaging were provided by

Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. The experimental group was divided into

two groups: The knockdown group and the overexpression group. The

knockdown groups included the short hairpin (sh)RNA negative

control (NC), shKLC3-64#, shKLC3-65# and shKLC3-66# groups, and the

overexpression groups included the Vector (empty vector) and KLC3

groups. All SKOV3 and A2780 cells were cultured in a constant

temperature incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. According to

the transduction instructions, KLC3 knockdown plasmids with a pPLK

GFP+Puro plasmid backbone were provided by Shanghai GeneChem Co.,

Ltd. The 2nd generation system was used for plasmid packaging. A

total of 1.5 µg knockdown plasmids, 1 µg pCMV–VSV-G and 0.5 µg

pCAG-dR8.9 (both from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) were

transfected into 293T cells (The Cell Bank of Type Culture

Collection of The Chinese Academy of Sciences) in 6-well plates

using Lipofectamine® 3000 transfection reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions at 37°C. Lentiviral particles were

harvested 48 h post-transfection, followed by infection of SKOV3 OC

cells for 24 h. Cells (30% confluence) were seeded in cell culture

dishes and were infected with lentiviral plasmids at multiplicity

of infection (MOI) of 10. At 37°C and screening of the cells for 7

days with medium containing 2 µg/ml puromycin (Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology). The target sequences of the knockdown lentiviral

plasmids were as follows: shNC, 5′-TGTCGCGGTAAGTGCCTCATA-3′;

shKLC3-64#, 5′-CAACAACTTGGCTGTCCTCTA-3′, shKLC3-65#,

5′-GACCCTGCATAACCTCGTGAT-3′ and shKLC3-66#,

5′-GCCACAGACCTTCTCCATGAT-3′.

In order to construct a plasmid for overexpressing

KLC3, full-length human KLC3 cDNA was first cloned into a p-Enter

plasmid (Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd.). The p-Enter-KLC3 construct

was then recombined into a Lenti-CMV expression vector to generate

the final Lenti-CMV-KLC3 plasmid for lentiviral packaging.

Lentiviral particles were produced by co-transfecting the

Lenti-CMV-KLC3 or Lenti-CMV-vector (negative control) plasmids with

the packaging plasmid pSPAX2 and the envelope plasmid pMD2.G into

293T cells (~70% confluence in 6-well plates) using Lipofectamine

3000 at 37°C, according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 6 h

of transfection, the medium was replaced with fresh complete

medium. For lentiviral transfection, the ratio of lentiviral

plasmid to packaging and envelope plasmids was

Lenti-CMV-KLC3/Lenti-CMV-vector: pSPAX2 (packaging plasmid): pMD2G

(envelope plasmid)=1:1:0.5 µg. After 36 h of culture, the virus was

harvested from the supernatant and concentrated with

lenti-X-concentrator (Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd.), and then added

to A2780 cells along with 5 µg/ml polybrene (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Cells (30% confluence) were seeded in cell culture

dishes and were infected with lentiviral plasmids at a MOI of 15 at

37°C. The cells were initially selected with medium containing 2.0

µg/ml puromycin (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 48 h. The

medium was then replaced with medium containing 5.0 µg/ml

puromycin, which was used for maintenance over a 7-day period to

establish stable cell lines. Western blotting was employed to

verify the infection efficiency, with the Lenti-CMV-vector serving

as the control.

For COL3A1 overexpression, SKOV3 cells were

transfected with a pcDNA3.1 plasmid (2 µg) encoding COL3A1 cDNA,

whereas empty vectors served as the NC group. All plasmids were

synthesized by Beijing Sino Technology Co. Ltd. The SKOV3 cells

were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1×106/well

were transfected with the aforementioned plasmids (10 µg) using

Lipofectamine 2000 for 48 h at 37°C according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The cells were collected for subsequent experiments

48 h post-transfection. In addition, in the cells with both KLC3

knockdown and COL3A1 overexpression, SKOV3 cells were transfected

for 48 h with the COL3A1 plasmid after infection with shKLC3. In

addition, western blotting was used to verify the transfection

efficiency.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to extract total RNA from SKOV3

and A2780 cells, A NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer was used to

measure the RNA concentration, and cDNA was synthesized by RT of 1

µg total RNA according to the manufacturer's protocol of the RT kit

(cat. no. R233-01; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). A qPCR machine was

used to amplify cDNA using the SYBR Green qPCR Mix (cat. no.

Q711-02; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). The thermocycling conditions

for amplification were as follows: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40

cycles at 95°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 30 sec and a final step at 95°C

for 15 sec, 60°C for 60 sec and 95°C for 15 sec. GAPDH was used as

an internal control. Subsequently, the 2−ΔΔCq method was

used to analyze the gene expression data (21). β-actin was used as an internal

control. The primer sequences were as follows: β-actin, forward

5′-GCGTGACATTAAGGAGAAGC-3′, reverse 5′-CCACGTCACACTTCATGATGG-3′;

KLC3, forward 5′-CTCAACATCCTGGCGCTGGT-3′, reverse

5′-TCCCGGTAACGCCCACGCTTC-3; CXCL12, forward

5′-TGCCCTTCAGATTGTAGCCC-3′, reverse 5′-CTGTAAGGGTTCCTCAGGCG-3′;

IGFL3, forward 5′-TGCTGTCCCGAGTCTTTTGG-3′, reverse

5′-GTGCCTCCTGTTCCTGGTA-3′; COL3A1, forward

5′-TAAAGGCGAAATGGGTCCCG-3′, reverse 5′-GGCACCATTCTTACCAGGCT-3′;

COL1A2, forward 5′-GAGGAGAGCCTGGCAACATT-3′, reverse

5′TCCACCTTGAACACCCTGTG-3′; TENM2, forward

5′-CAAAGAGTGTCGCTACACAAGC-3′, reverse 5′-TCCTGCTGTCATGGTCATAGG-3′;

CREB3L1, forward 5′-TGGAGAATGCCAACAGGACC-3′, reverse

5′-CCAGCACCAGAACAAAGCAC-3′; MMP13, forward

5′-CAGTTTGCAGAGCGCTACCT-3′, reverse 5′-TTCTCGGAGCCTCTCAGTCA-3′;

IGFBP5, forward 5′-ACAAGAGAAAGCAGTGCAAACC-3′, reverse

5′-CGTCAACGTACTCCATGCCT-3′; SLC14A1, forward

5′-AGCCAGCTAGAGTGGTCTTT-3′, reverse 5′-TCCAAACAGGACCATGACGG-3′;

SPARC, forward 5′-TTCGGCATCAAGCAGAAGGAT-3′, reverse

5′-TTAGCACCTTGTCTCCAGGC-3′.

Xenograft model

A total of 12 4-week-old female BALB/c nude mice

(weight, 15–16 g) were purchased from Beijing Vital River

Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. The mice were housed in the

animal facility under standard conditions, with a controlled

temperature of 25±2°C and humidity of 55±5%, under a 12-h

light/dark cycle, with free access to water and food. Each mouse

received a subcutaneous injection of 100 µl (5×106) cell

suspension into the right flank with shNC-infected SKOV3 cells,

shKLC3-infected SKOV3 cells, Vector-infected A2780 cells or

KLC3-overexpressing A2780 cells. The study was terminated based on

tumor volume (~1,500 mm3) as the humane endpoint. Mice

injected with shNC-infected SKOV3 cells and shKLC3-infected SKOV3

cells were sacrificed on day 24, whereas mice injected with

Vector-infected A2780 cells and KLC3-overexpressing A2780 cells

were sacrificed on day 21. Notably, no mice succumbed before

reaching the humane endpoint criteria. Tumor volume was measured

twice per week using electronic calipers and the animals were

weighed five times per week. At the end of the study, mice were

euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation (30% vol/min) followed by

cervical dislocation as noted in the IACUC-approved protocol, and

the tumors were excised, weighed and cut in half. No analgesics

were administered during the study since flank tumor studies are

considered painless. Animal experiments were approved by the Animal

Experimental Ethics Committee of The First Hospital of Lanzhou

University (approval no. LDYYLL-2023-495).

IHC

Samples were fixed in 10% neutral formalin fixative

solution (BBI Solutions) embedded in paraffin at room temperature

overnight, and divided into 3-µm sections, which were

deparaffinized with xylene and then rehydrated with a succession of

decreasing alcohol concentrations (100, 95, 85, 70 and 50%

ethanol). Tissue sections were then placed in antigen retrieval

buffer (pH 9.0; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) in a

microwave oven on medium power for 8 min until boiling, then cooled

for 8 min and switched to medium-low power for 7 min. After natural

cooling, the slides were placed in PBS (pH 7.4; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.) and washed three times on a destaining

shaker. Subsequently, 3% hydrogen peroxide solution was added to

the sample at room temperature for 25 min to block endogenous

peroxidase, followed by blocking with 3% BSA (Sangon Biotech Co.,

Ltd.) at room temperature for 30 min. The histological sections

were then incubated at 4°C overnight with rabbit anti-KLC3 antibody

(1:200; cat. no. ab180523; Abcam) and anti-PCNA antibody (1:200;

cat. no. 10205-2-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), and with a

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary

antibody (1:200; cat. no. SA00001-2; Proteintech Group, Inc.) at

37°C for 30 min. Sections were then counterstained with 0.1%

hematoxylin (Boster Biological Technology) at room temperature for

2 min and were stained with the chromogen DAB (Boster Biological

Technology). With an objective magnification of ×200 or ×400,

histological images were captured using a light microscope (cat.

no. AE2000; Motic Incorporation, Ltd.). A total of 10 normal

ovarian tissue samples and 48 OC tissue samples, as well as mouse

tumor tissues were selected for assessing expression levels. The

IHC scores were independently evaluated by two pathologists.

Staining intensity was categorized as 0, no staining; 1, weak

staining; 2, moderate staining; and 3, strong staining. Based on

the extent of brown staining, the stained area was divided into

percentages ranging from 1 to 99%. Finally, the staining intensity

and stained area were each multiplied by 100. The patients were

divided into two groups, high and low expression, according to the

median value.

Cell Counting Kit (CCK)-8 assay

For the CCK-8 assay, wild-type and infected cells

were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated with CCK-8 Reagent

(Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 2 h over 5

consecutive days. The CCK-8 reagent was added for a 2-h incubation

period. Absorbance at 450 nm was subsequently measured using a

microplate reader.

Colony formation assay

Wild-type and infected/transfected cells were seeded

at a density of 500 cells/well in 6-well plates. After 14 days, the

cells were stained with 10% Giemsa (Beijing Biotopped Technology

Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 10 min after being fixed with

methanol at room temperature for 30 min. To assess the colony

formation capacity of the cells, visible colonies were counted. A

dense conglomerate of cells was regarded as a colony when the

number of cells exceeded 50. ImageJ software [Fiji (https://imagej.net/software/fiji/downloads) (National

Institutes of Health)] was used to count the number of colonies.

This experiment was repeated three times.

Comet assay

Cells were cultured in 6-well plates until they

reached ~30% confluence. The transduced cells were subsequently

trypsinized and collected by centrifugation at 1,200 × g for 5 min

at 4°C, forming a compact pellet. After washing, the cells were

resuspended in 200 µl ice-cold 1X PBS. Subsequently, the cell

suspension was carefully mixed at a ratio of 1:10 with low melting

point agarose maintained at 42°C and was promptly pipetted onto the

designated CometSlide™ area (Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.). Slides were incubated in the dark at 4°C for 30 min,

followed by immersion in chilled lysis solution (Trevigen, Inc.;

Bio-Techne) at 4°C for 30 min. The slides were then incubated in

alkaline unwinding buffer (0.3 N NaOH, 1 mM EDTA) at room

temperature for 30 min. The slides were then transferred to a

horizontal electrophoresis chamber and subjected to electrophoresis

using buffer (0.3 N NaOH, 1 mM EDTA) at an electric field strength

of 1 V·cm−1 for 20 min. Following electrophoresis, the

samples were dried and stained with ethidium bromide. The comet

tails were visualized under a DM 2500 fluorescence microscope

(Leica Microsystems GmbH) and were quantified using Komet 5.5

software (Andor Technology Ltd.). A minimum of 50 cells were

analyzed per treatment condition. All experiments were conducted

independently at least three times.

Wound healing assay

Infected/transfected cells were cultured to ~90%

confluence in 12-well plates and a wound was introduced using a

sterile 200-µl pipette tip. After washing twice with PBS, cells

were cultured in DMEM/F12 without FBS for 48 h. Cell images were

obtained using fluorescence microscopy (IX73; Olympus Corporation).

Wound sizes were measured with ImageJ 1.5.2a software and were

calculated as a percentage (from 0 to 24 h).

Transwell migration assay

Transwell migration assays were conducted using

24-well plates fitted with membranes containing 8-µm pores

(Corning, Inc.). Cells were seeded on the upper chamber without

serum at a density of 2×104 cells/well, whereas complete

medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mg/ml streptomycin, 10,000

U/ml penicillin and 25 µg/ml amphotericin B was added to the lower

chamber. After a 24-h incubation period at 37°C, the cells were

removed from the upper chamber using a cotton swab followed by

fixation with 4% formaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min and

staining with Giemsa solution at room temperature for 15 min. The

assessment of migration involved counting cell numbers in 10 random

fields under a light microscope (Leica Microsystems, Inc.); this

process was repeated three times for accuracy and consistency.

Apoptosis assay

For the apoptosis assay, the cells were harvested,

washed with PBS, suspended in binding buffer and sequentially

stained with the Annexin V-FITC Detection Kit (Roche Applied

Science) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Subsequently,

apoptotic cells were detected using a FacsCalibur flow cytometer

(BD Biosciences), and the results were analyzed using CellQuest

version 3.3 software (BD Biosciences). Each experiment was

performed in triplicate.

Western blotting

Total proteins were extracted from cells and tissues

using RIPA lysis buffer and PMSF at a ratio of 1:100 (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). Phosphorylated proteins were extracted

separately with the addition of phosphatase inhibitors (Biosharp

Life Sciences). The protein levels were quantified using a BCA

assay kit. Subsequently, an equal volume of protein mixture (30 µg)

was pipetted into the wells of the gel matrix (containing 30%

acrylamide), and the electrical potential was fixed at 120 volts

for the purpose of conducting gel electrophoresis. After a 30-min

transfer, the PVDF membrane was immersed in a solution of 5%

non-fat milk powder and blocked for 2 h at 25°C. Subsequently,

membranes were washed three times with TBS-0.1% Tween 20 (TBST),

followed by incubation with the primary antibodies overnight at

4°C, three further washes with TBST and incubation with a

HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (anti-rabbit IgG; 1:5,000; cat.

no. GTX213110; GeneTex, Inc.) for 2 h at 25°C. Chemiluminescent

solution was then added for 10 sec for visualization. The following

primary antibodies were used: KLC3 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab180523),

E-cadherin (1:10,000; cat. no. ab40772), N-cadherin (1:10,000; cat.

no. ab76011), Vimentin (1:5,000; cat. no. ab92547), Snail (1:1,000;

cat. no. ab216347), GAPDH (1:5,000; cat. no. ab8245) and α-tubulin

(1:10,000; cat. no. ab7291) (all from Abcam); PALB2 (1:2,000; cat.

no. 14340-1-AP), XRCC1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 21468-1-AP), XRCC2

(1:20,000; cat. no. 20285-1-AP) and COL3A1 (1:1,000; cat. no.

22734-1-AP) (all from Proteintech Group, Inc.); AKT (1:1,000; cat.

no. 9272), PI3K (1:1,000; cat. no. 4292), phosphorylated (p-)AKT

(1:1,000; cat. no. 4060) and p85α (also known as p-PI3K; 1:1,000;

cat. no. 4228) (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). Protein

visualization was achieved using a highly sensitive ECL substrate

kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). All results were

normalized to the internal reference proteins GAPDH and tubulin.

Densitometric analysis was carried out using ImageJ 1.5.2a

software.

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq)

Total RNA was extracted from SKOV3 cells infected

with shKLC3 and shNC using a RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc.), and

RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.). Samples with RNA integrity number >7.0 were

used for library preparation. A total of 4 µg DNase-treated RNA

from each sample was used to construct cDNA libraries using the

TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit (cat. no. 20020597;

Illumina, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was

fragmented and subjected to two rounds of cDNA synthesis and

adapter ligation. Libraries were quantified using qPCR

(concentration >2 nM) and qualified using an Agilent 2100

Bioanalyzer. Paired-end 100 bp reads were generated on the Illumina

NovaSeq 6000 and HiSeq X Ten platforms (NovaSeq 6000 S1 Reagent

Kit, 300 cycles; cat. no. 20012863-1; Illumina, Inc.). High-quality

reads were obtained by trimming adapters and filtering low-quality

reads. Read alignment and differential gene expression analysis

were performed using the DESeq2 package (v1.26.0; http://github.com/thelovelab/DESeq2),

and genes with a false discovery rate-adjusted P-value (q-value)

<0.05 were considered significantly differentially

expressed.

Bioinformatics analyses

Multivariate and principal component analyses were

performed using the ClustVis online tool (https://github.com/fw1121/ClustVis). Functional

enrichment analysis was performed using Metascape (https://metascape.org/gp/index.html#/main/step1)

(22). Metascape pathway enrichment

analysis uses Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/kegg_ja.html), Reactome

(https://reactome.org/) and MSigDB (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb). Statistical

significance of gene overrepresentation was assessed using a

hypergeometric test (Fisher's exact test), followed by Bonferroni

correction for multiple comparisons. Heatmaps and volcano plots

were generated using TBtools (v 1.055; http://github.com/CJ-Chen/TBtools/releases).

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP)

Cells were lysed with 250 µl NP-40 lysis buffer

(cat. no. P0013F; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 30 min

on ice and then centrifuged at 16.2 × g and 4°C for 10 min to

remove cell fragments. The protein lysate (200 µl), bound to 25 µl

magnetic beads (cat. no. 88802; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

with anti-KLC3 (1:50; cat. no. ab180523; Abcam), anti- COL3A1

(1:50; cat. no. 22734-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) or IgG (1:200;

cat. no. 10284-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) antibodies, was

incubated overnight at 4°C. The next day, the magnetic beads were

adsorbed using a magnetic grate and washed with lysis buffer

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The lysis buffer was transferred

to the newly washed column and incubated at 4°C for 2 h. After

incubation, the supernatant was discarded and washed five times

with 500 µl IP-specific lysis buffer (cat. no. 26149; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Finally, KLC3 and COL3A1 levels were analyzed by

western blotting using anti-KLC3 (1:200; cat. no. ab180523; Abcam)

and anti-COL3A1 (1:200; cat. no. 22734-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 20.0

software (IBM Corp.) and GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 (Dotmatics).

Each experiment was performed in triplicate and continuous data are

presented as the mean ± standard deviation. The differences between

experimental groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by

Bonferroni's post hoc test or unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test.

Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and

log-rank test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

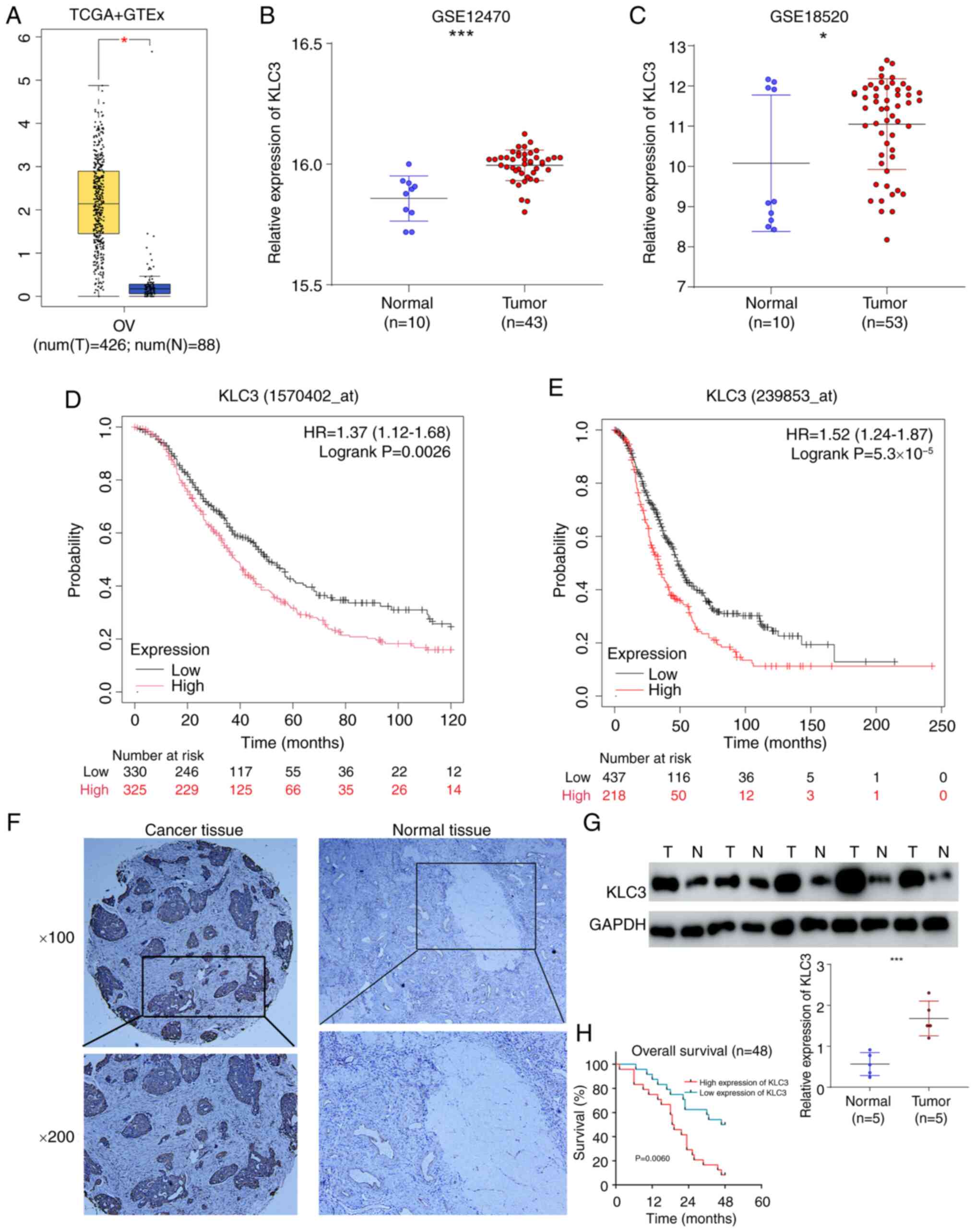

KLC3 expression and survival analysis

in OC

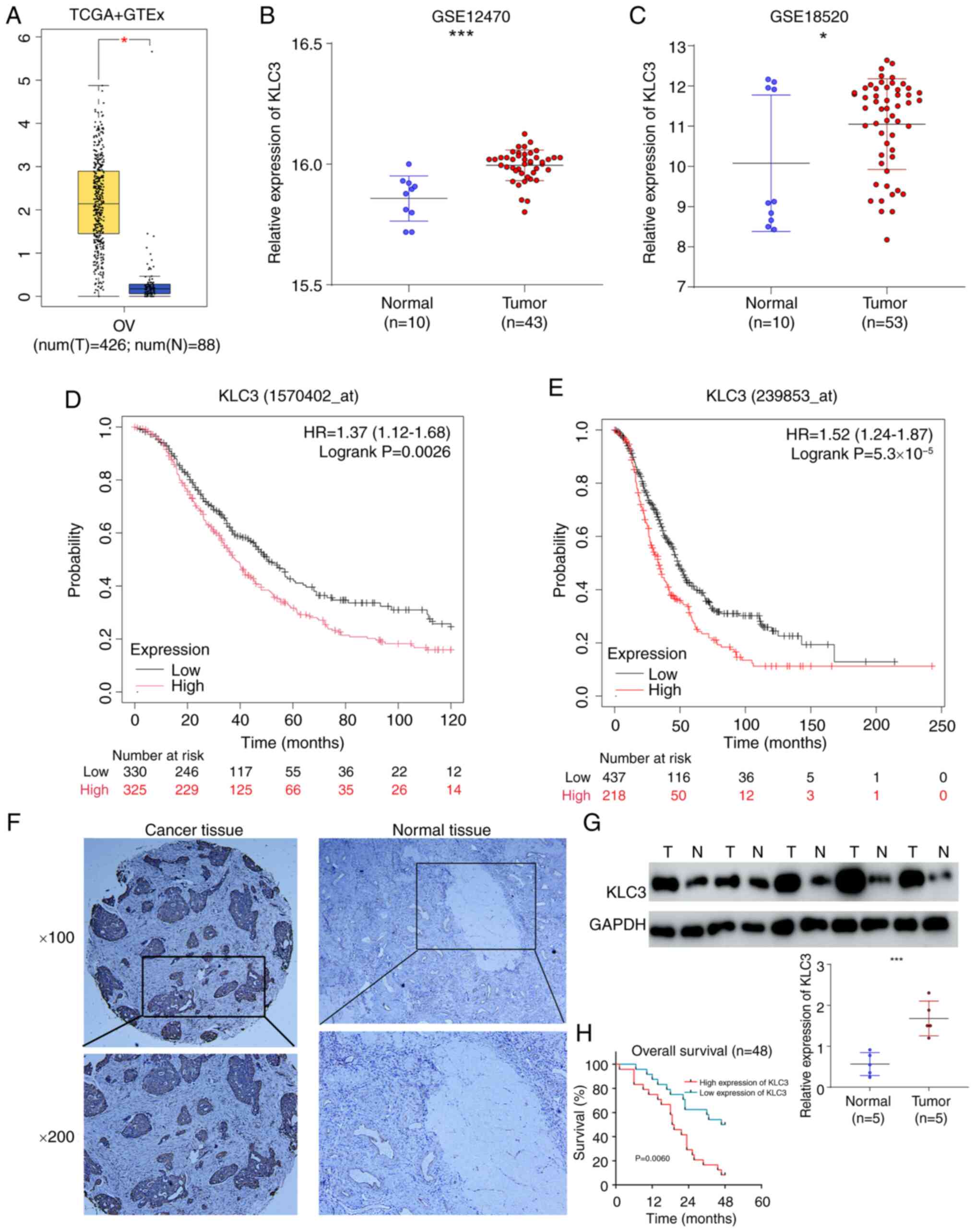

To assess the relationship between KLC3 and OC, the

present study initially examined the expression of KLC3 in the

GEPIA database, which revealed high mRNA levels of KLC3 in OC

compared with normal tissue (Fig.

1A). Subsequently, the present study investigated the

expression of KLC3 in the GSE12470 and GSE18520 datasets, and its

expression was also significantly elevated in OC tissues compared

with in tissues from healthy controls in these datasets (Fig. 1B and C). The Kaplan-Meier curve

analysis demonstrated that patients with OC and low KLC3 expression

had a better prognosis in different probesets: 1570402_at (HR=1.39,

95% CI 1.13–1.7) and 239853_at (HR=1.52, 95% CI 1.24–1.87)

(Fig. 1D and E). Additionally, the

results of IHC indicated that the expression of KLC3 was higher in

OC tissues than that in normal tissues (Fig. 1F). Western blot analysis of five OC

samples and five normal samples also revealed an elevated

expression of KLC3 in OC (Fig. 1G).

Finally, based on the expression levels of KLC3 in OC, 48 patients

were categorized into high and low expression groups. The results

revealed that patients with OC and high KLC3 expression had a

poorer overall survival rate (Fig.

1H). Based on these findings, it could be hypothesized that

KLC3 serves a notable role in the development and progression of

OC, warranting further investigation into its function.

| Figure 1.Bioinformatics analysis shows that

KLC3 is highly expressed in OC tissues and is associated with poor

prognosis. (A) KLC3 mRNA expression levels were determined by Gene

Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis. Boxplot analysis shows

the expression levels in log2 (TPM + 1). KLC3 mRNA levels in OC

tissues and N ovarian tissues in the (B) GSE12470 and (C) GSE18520

datasets. Kaplan-Meier plotter database was used to assess the

overall survival in different probes: (D) 1570402_at (HR=1.39, 95%

CI 1.13–1.7, P=0.0017) and (E) 239853_at (HR=1.52, 95% CI

1.24–1.87, P=5.3×10−5). (F) Representative

immunohistochemical staining of KLC3 protein expression in OC and N

ovarian tissues. (G) Western blot analysis of the protein levels of

KLC3 in five OC tissues and five ovarian tissue. (H) Overall

survival of all patients in relation to KLC3 expression.

*P<0.05, ***P<0.001. GTEx, Genotype-Tissue Expression; KLC3,

kinesin light chain 3; N, normal; OC, ovarian cancer; T, tumor;

TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas. |

Effect of KLC3 alterations on OC cell

proliferation, migration, apoptosis and DNA damage repair

capacity

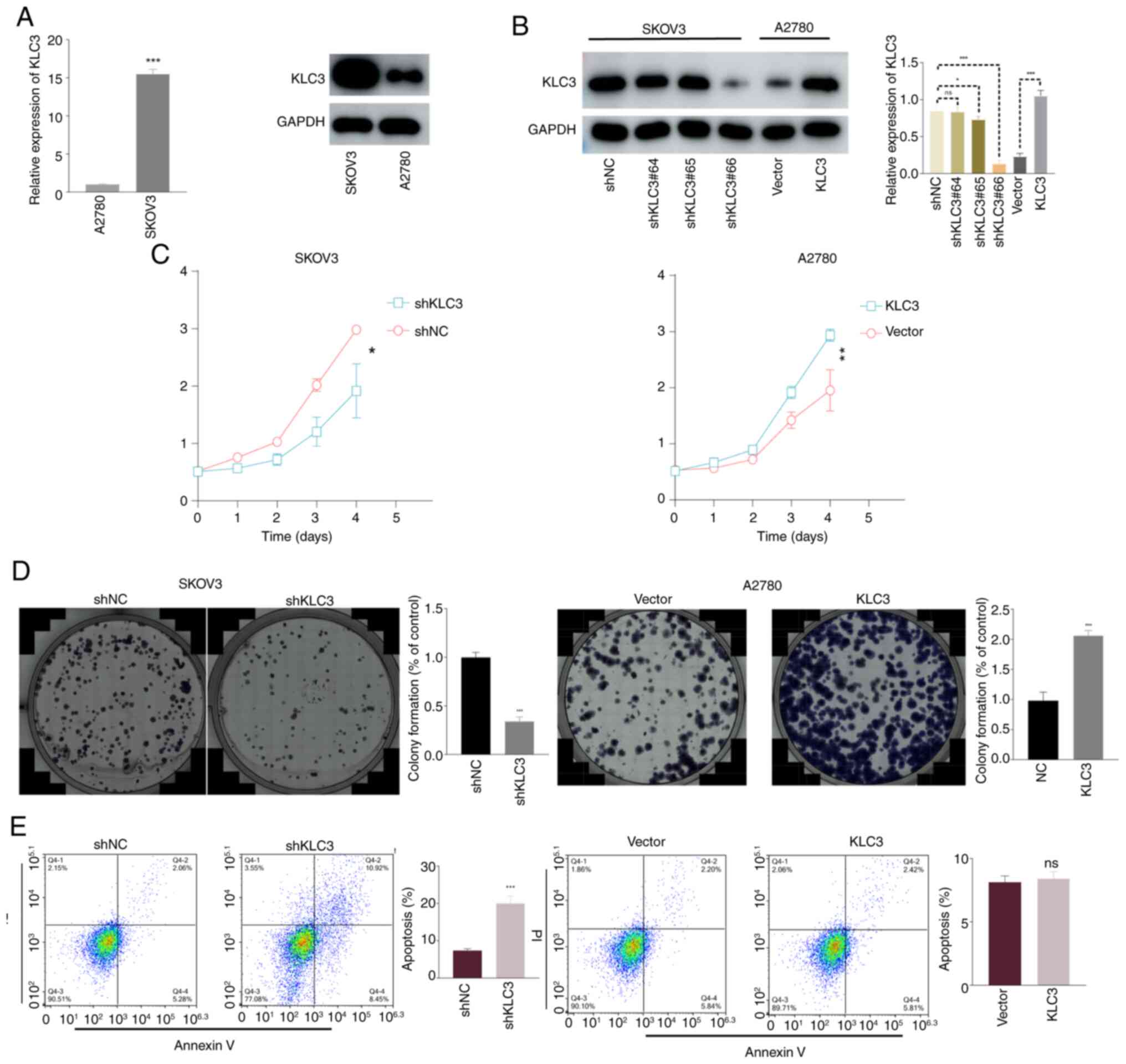

The present study examined the mRNA and protein

expression levels of KLC3 in two OC cell lines, SKOV3 and A2780. As

shown in Fig. 2A, the expression of

KLC3 was significantly higher in SKOV3 cells compared with that in

A2780 cells. To investigate the functional role of KLC3 in OC,

lentiviral knockdown of KLC3 was performed in the SKOV3 cell line

and overexpression of KLC3 was induced in the A2780 cell line.

Notably, shKLC3#66 exhibited optimal knockdown efficiency

(subsequently denoted as shKLC3), achieving a knockdown rate of

80%, and the overexpression vector met the experimental standards

for subsequent analyses (Fig.

2B).

To assess proliferation, the CCK-8 assay was

performed over 5 consecutive days. The results revealed a

significant reduction in proliferation following KLC3 knockdown,

whereas proliferation was enhanced in response to KCL3

overexpression (Fig. 2C). The

colony formation assay demonstrated diminished colony-forming

ability following KCL3 knockdown relative to the control group,

whereas this ability was enhanced post-KCL3 overexpression

(Fig. 2D).

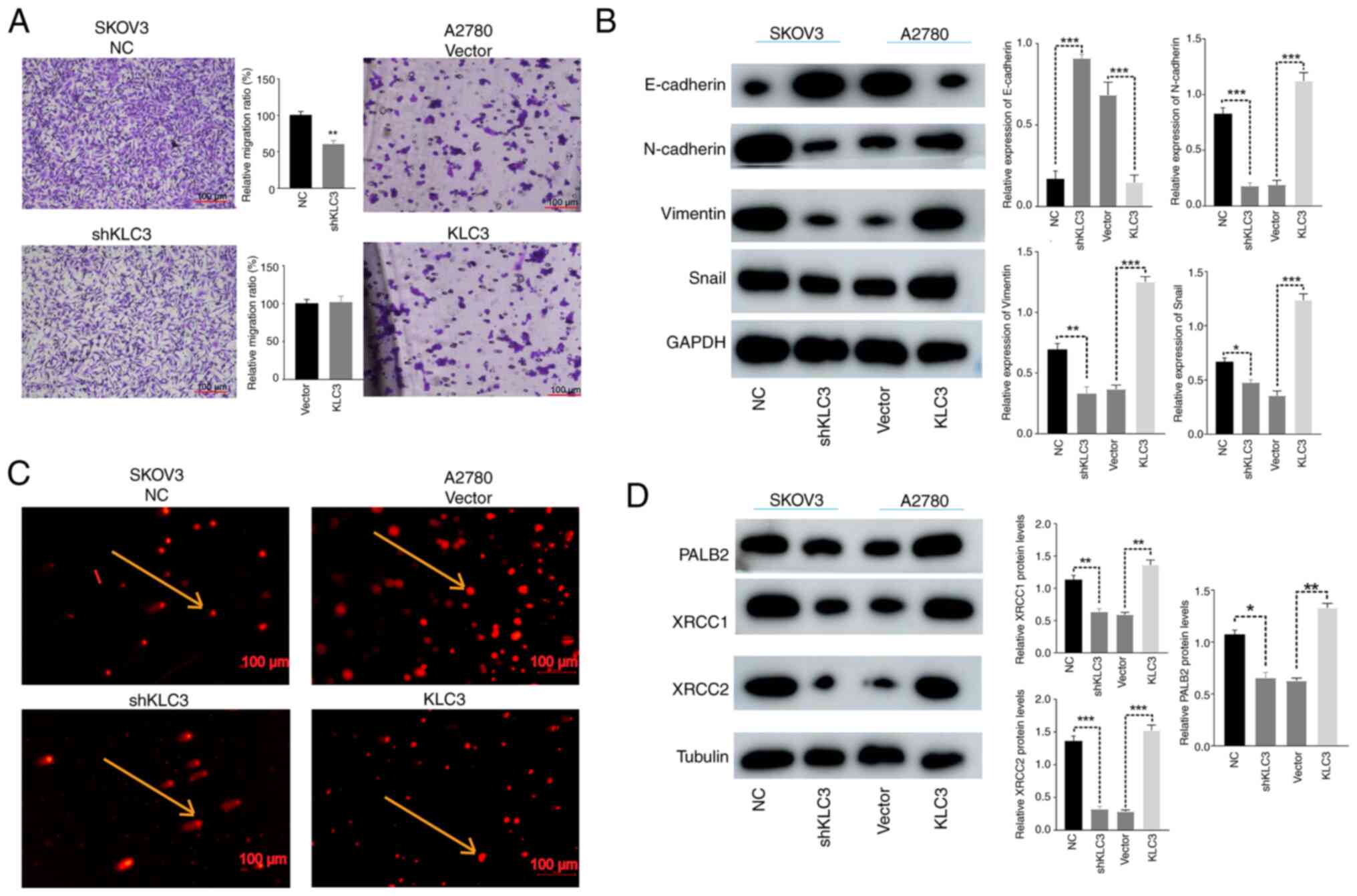

When investigating the relationship between KLC3 and

apoptosis, it was revealed that knocking down KLC3 significantly

increased the apoptosis of OC cells, whereas overexpression of KLC3

did not result in a noticeable change in apoptosis levels (Fig. 2E). Similarly, compared with in the

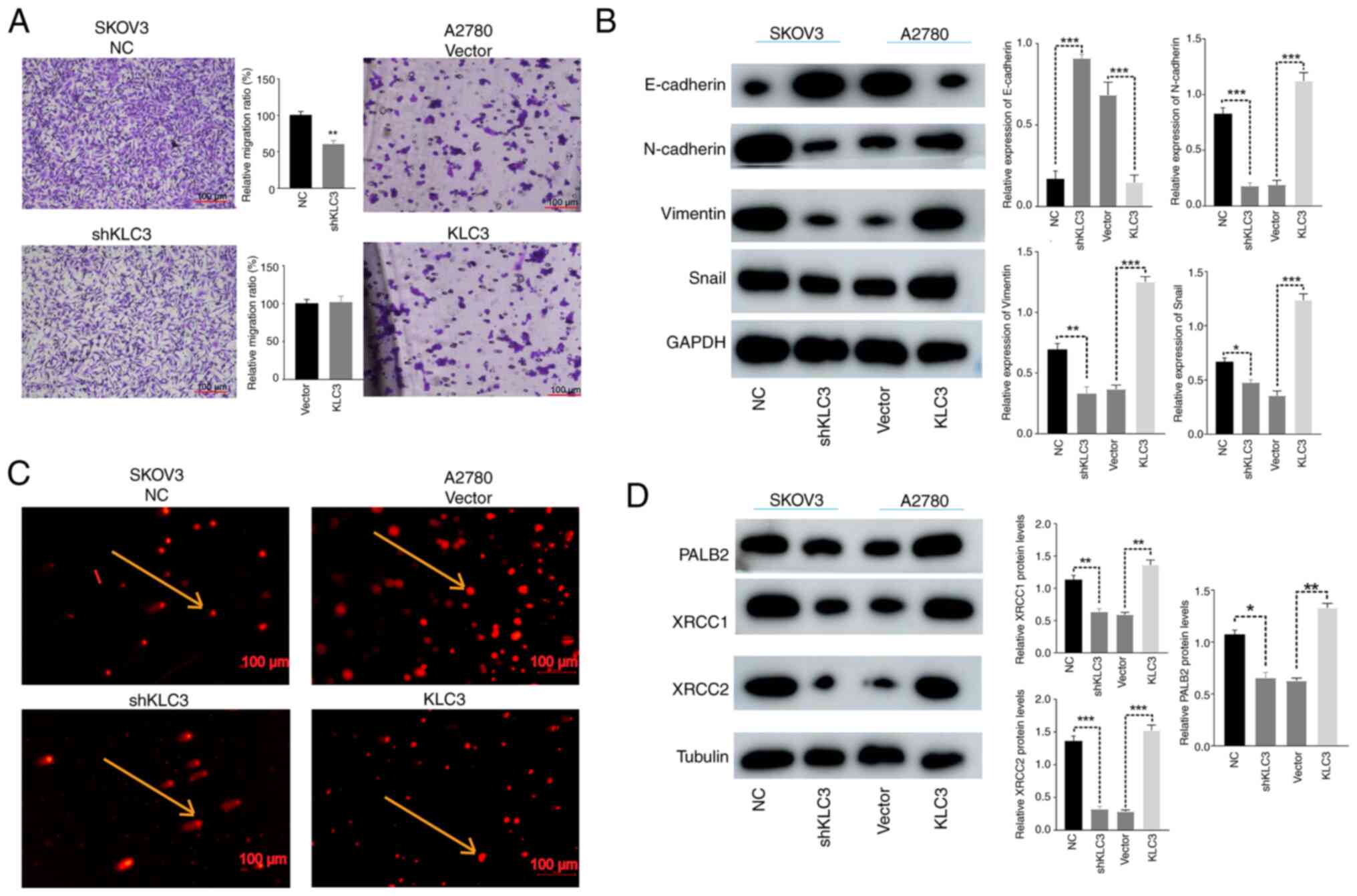

control group, knockdown of KLC3 weakened the migratory ability of

OC cells in the Transwell assay; however, overexpression of KLC3

did not lead to a significant change in the migratory ability of

A2780 cells (Fig. 3A). In order to

further investigate the underlying mechanisms, changes in

EMT-related proteins, such as E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Snail and

Vimentin, were examined through western blotting. It was observed

that when the expression of KLC3 was knocked down, there was a

corresponding decrease in the expression levels of N-cadherin,

Snail and Vimentin, whereas an increase in E-cadherin expression

was noted. Conversely, when KLC3 expression was increased, there

was a concomitant increase in the expression levels of N-cadherin,

Snail and Vimentin, with a decrease in E-cadherin expression

(Fig. 3B).

| Figure 3.Effects of KLC3 on the migration and

DNA damage of OC cells. (A) Migration of lung cancer cells was

analyzed using a Transwell assay. Scale bar, 100 µm. (B) Expression

levels of epithelial-mesenchymal transition-associated proteins in

OC cells, detected by western blotting. (C) DNA double-strand

breakage was observed using the comet assay. The cells indicated by

arrows represent intact DNA strands (SKOV3 NC and A2780 Vector) and

broken DNA strands (SKOV3 shKLC3 and A2780 KLC3). Scale bar, 100

µm. (D) Western blot analysis of XRCC1, XRCC2 and PALB2 expression.

The mean grayscale of bands was semi-quantitatively analyzed.

*P<0.05, **P<0.05, ***P<0.001. KLC3, kinesin light chain

3; NC, negative control; OC, ovarian cancer; sh, short hairpin. |

DNA damage is a known instigator in the

transformation of normal cells into tumor cells. In the context of

cancer treatment, augmenting the efficacy of radiotherapy and

chemotherapy involves impeding DNA damage repair in tumor cells

through diverse modalities. The association between KLC3 expression

and resistance to DNA damage in OC was substantiated through the

comet assay. The reduced expression of KLC3 resulted in a marked

increase in uncoiled and damaged DNA strands and fragments, whereas

overexpression of KLC3 exhibited minimal impact on DNA damage

(Fig. 3C). Examination of the DNA

damage-associated proteins XRCC1, XRCC2 and PALB2 revealed that

diminished expression of KLC3 corresponded to reduced expression

levels of XRCC1, XRCC2 and PALB2; conversely, overexpression of

KLC3 was associated with elevated levels of these proteins

(Fig. 3D). These collective

findings indicated that KLC3 may have a pivotal role in various

malignant phenotypes, as well as anti-DNA damage repair mechanisms,

within human OC cell lines.

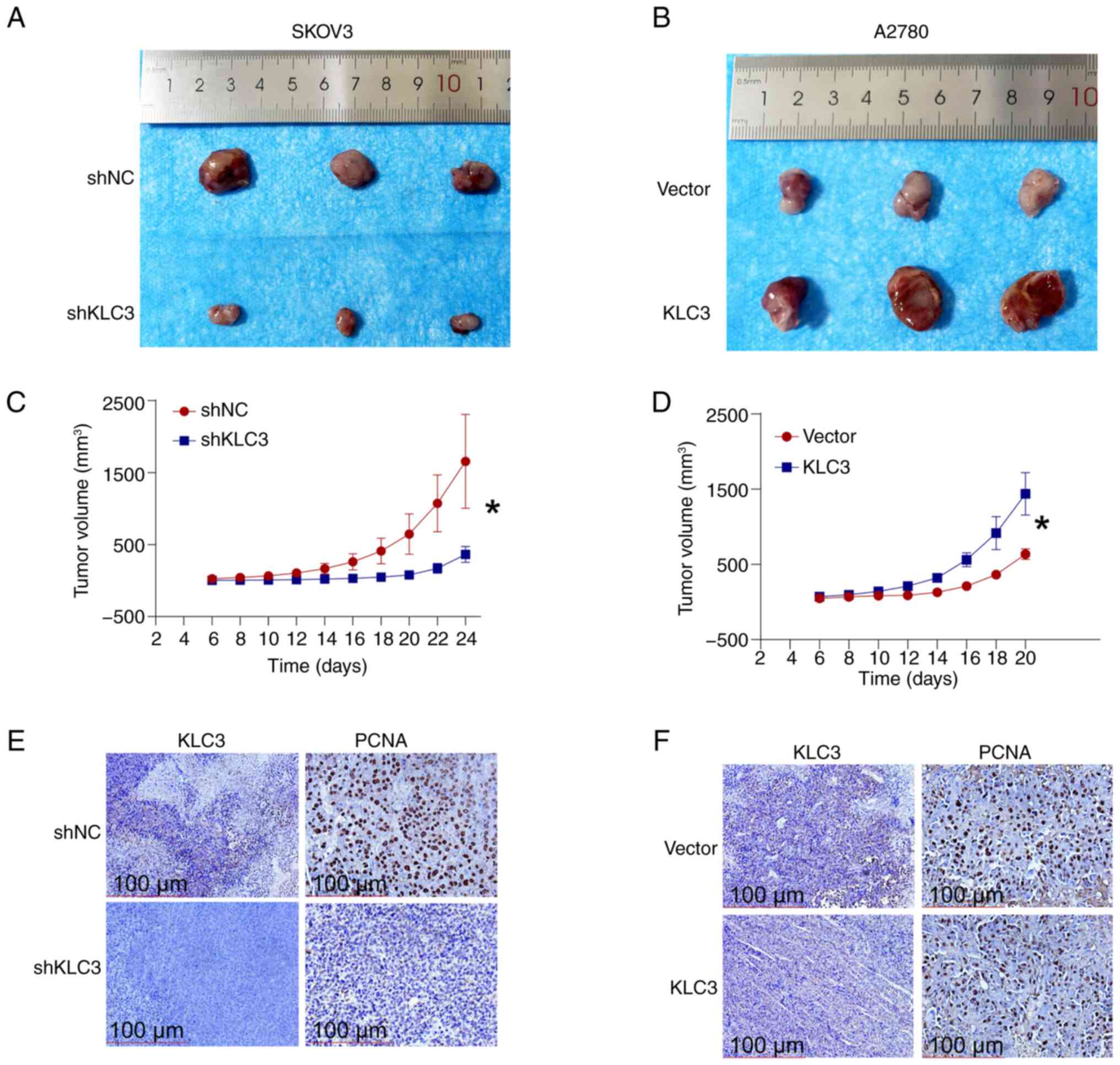

KLC3 knockdown suppresses the in vivo

growth of OC cells

The impact of KLC3 knockdown on tumor growth was

assessed using a nude mouse xenograft model. Compared with in the

control group, KLC3 knockdown impeded tumor growth (Fig. 4A), with a notably reduced growth

rate compared with that in the control group (Fig. 4C). In addition, IHC analysis

revealed decreased expression of KLC3 and its associated

proliferation marker PCNA in the knockdown group (Fig. 4E). By contrast, overexpression of

KLC3 stimulated in vivo tumor cell proliferation (Fig. 4B) and markedly increased tumor

growth rate (Fig. 4D). The results

of IHC indicated no significant difference in the expression levels

of KLC3 and PCNA between the overexpression group and the control

group (Fig. 4F). No difference in

KLC3 expression was found after tumor formation; however, the

overexpression efficiency of all cells was verified by western

blotting before injection. These findings underscore the pivotal

role of KLC3 in OC cell proliferation.

High-throughput sequencing

analysis

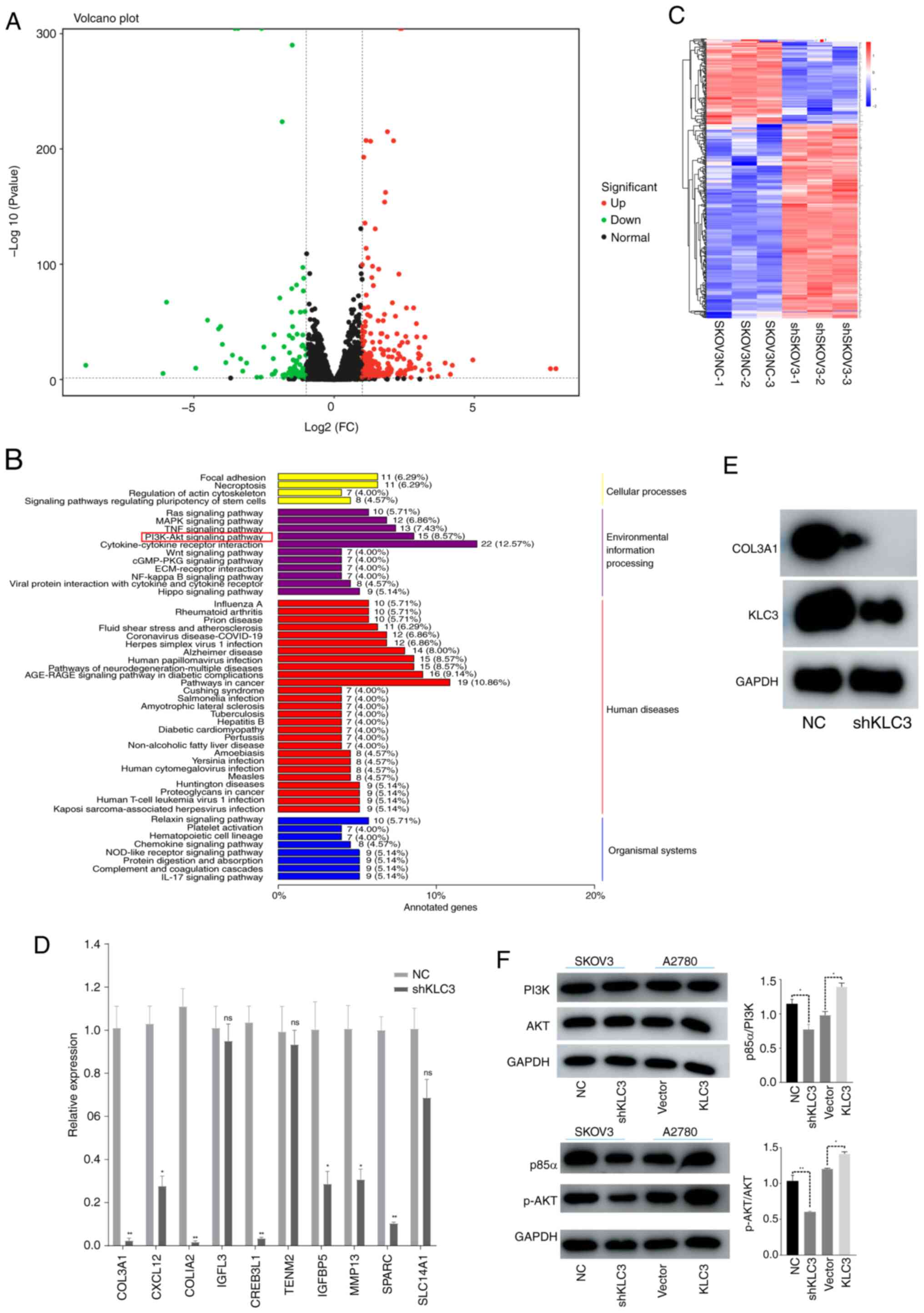

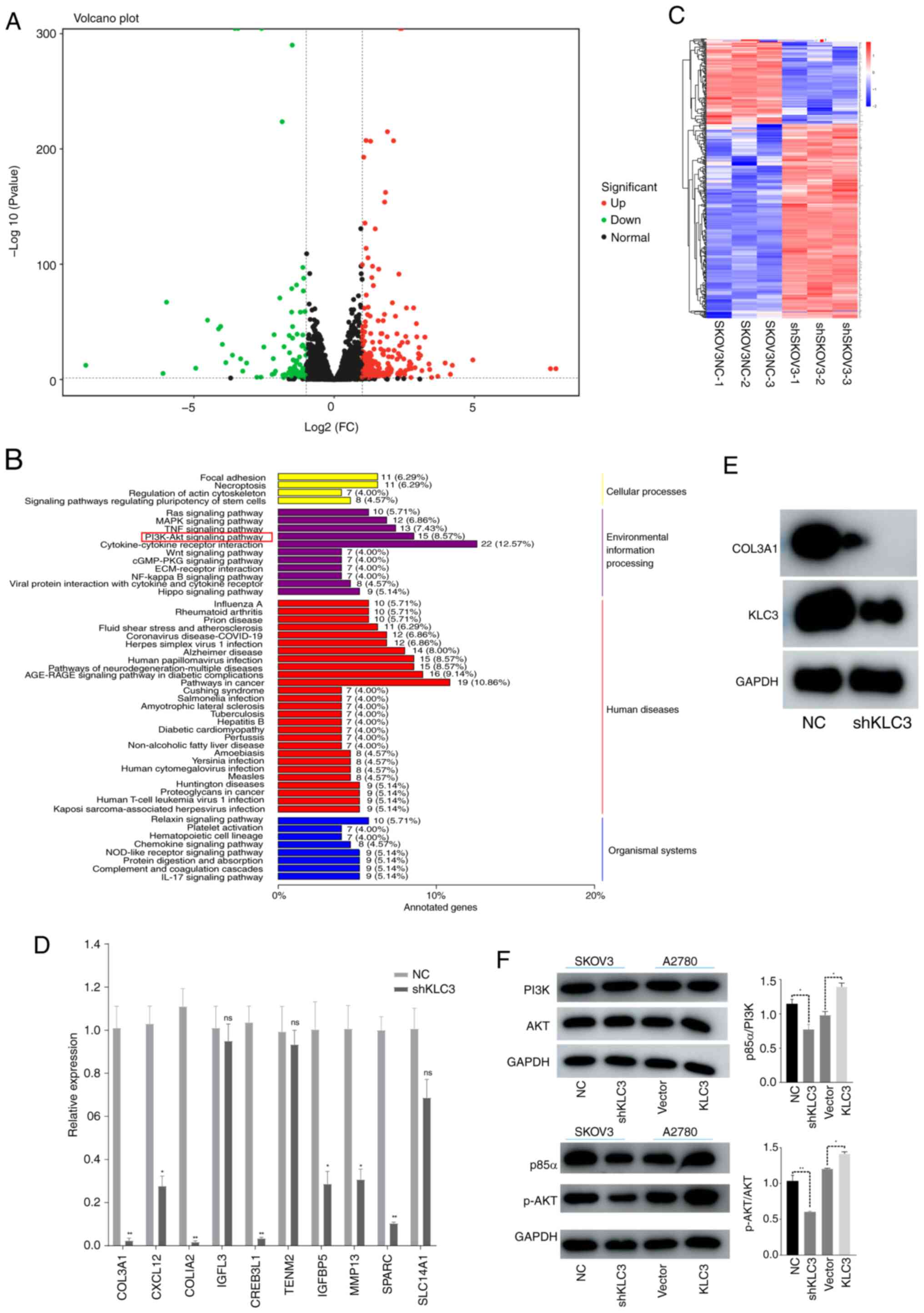

According to the high-throughput sequencing

analysis, a total of 13,516 differentially expressed genes were

identified between the SKOV3-NC and SKOV3-shKLC3 groups. The

screening criteria were set at fold change ≥2 and P<0.05,

resulting in 376 differentially expressed genes, with 261

upregulated and 115 downregulated (Fig.

5A and C). The top 10 downregulated genes were validated by

PCR, and it was revealed that seven were significantly decreased

and three showed no change between the shKLC3 and NC groups; COL3A1

exhibited the most significant difference (Fig. 5D). Western blotting results

demonstrated that KLC3 knockdown led to decreased COL3A1 levels

(Fig. 5E). Pathway enrichment

analysis revealed that the ‘PI3K-Akt signaling pathway’ was the

most enriched (8.57%), followed by the ‘TNF signaling pathway’

(7.43%) among others (Fig. 5B). The

western blot analysis results for AKT, PI3K, p-AKT and p85α

confirmed that decreased KLC3 expression did not affect the levels

of AKT and PI3K, whereas it did lead to a decrease in p-AKT and

p38a levels. Conversely, increased KLC3 expression did not impact

the levels of AKT and PI3K, but resulted in an increase in p-AKT

and p38a expression (Fig. 5F).

Therefore, these findings suggested that overexpression of KLC3 may

promote COL3A1 expression and activate the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway in OC cells.

| Figure 5.KLC3 activates the PI3K/AKT pathway

in ovarian cancer. (A) Differential mRNA volcano plot. Green dots

represent downregulated genes, while red dots represent upregulated

genes. The abscissa is the FC. (B) KEGG classification diagram of

differentially expressed genes. (C) Clustering diagram of

differentially expressed genes. The horizontal axis represents

sample names and clustering results, and the vertical axis

represents differentially expressed genes and gene clustering

results. Different columns represent different samples, and

different rows represent different genes. The color represents the

expression level of the gene in the sample. (D) Reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR was used to verify the expression of

the top 10 differentially expressed genes. (E) Western blotting was

used to detect the changes in KLC3 and COL3A1 protein expression in

SKOV3 cells. (F) Western blotting was used to investigate the

changes in PI3K/AKT pathway proteins after KLC3 expression was

altered. *P<0.05, **P<0.05 vs. NC or as indicated. COL3A1,

collagen type III α1; FC, fold change; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes; KLC3, kinesin light chain 3; NC, negative

control; ns, not significant; p-, phosphorylated; sh, short

hairpin. |

KLC3 promotes activation of the

PI3K/AKT pathway through COL3A1

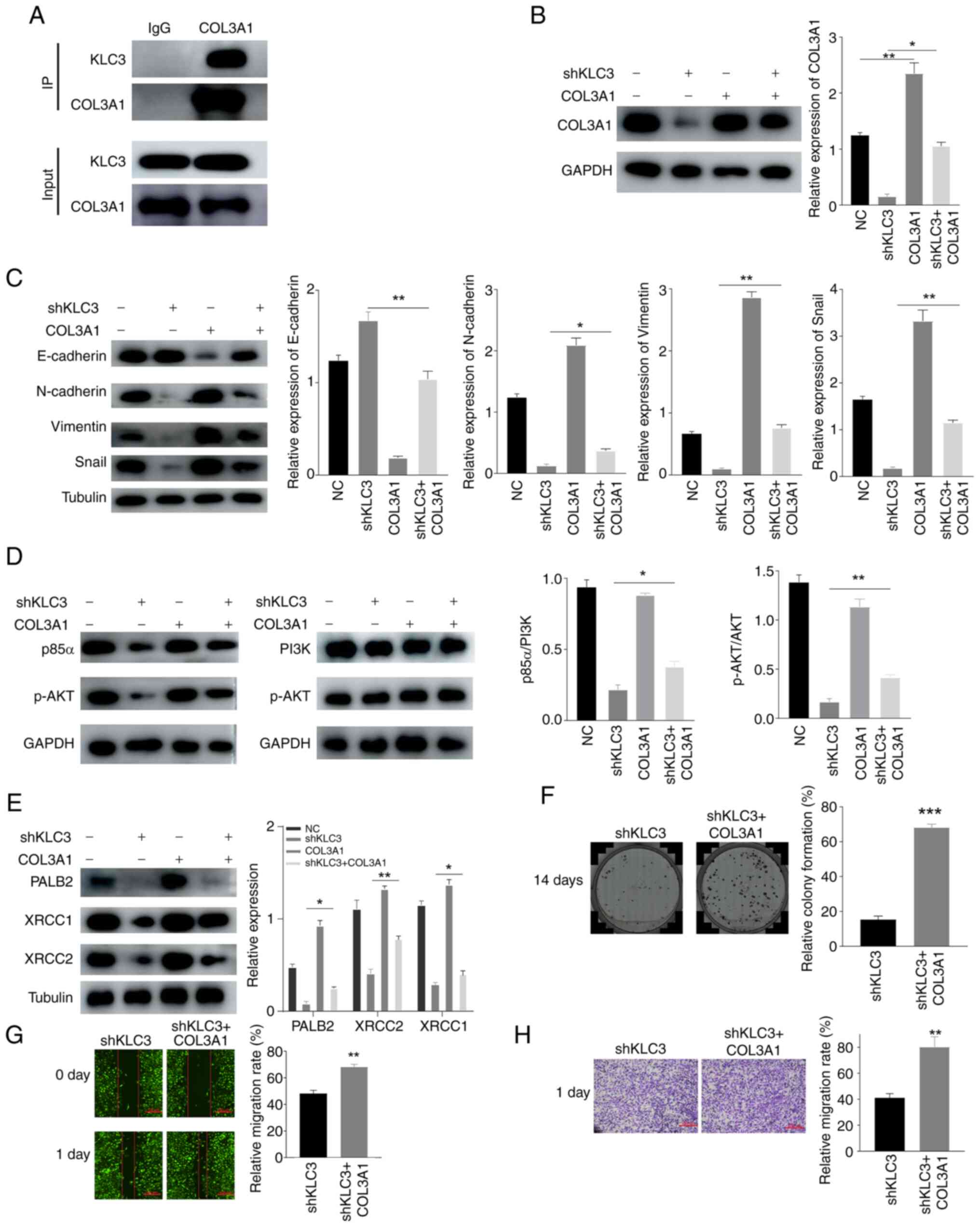

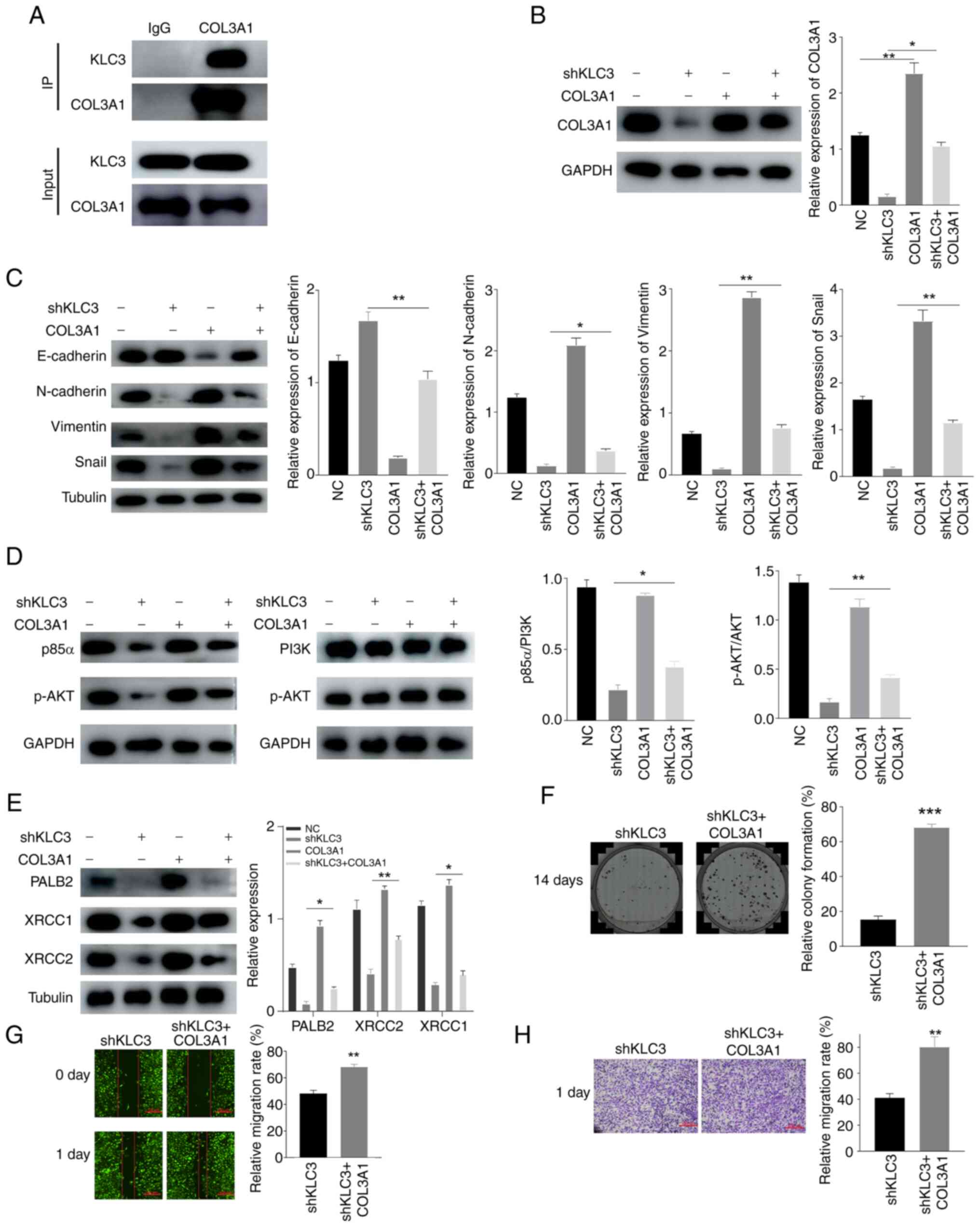

The aforementioned findings demonstrated that

alterations in KLC3 can lead to changes in COL3A1 and activation of

the PI3K/AKT pathway. To further investigate the mechanism by which

KLC3 promotes the malignant progression of OC cells, the

interaction between KLC3 and COL3A1 was examined using co-IP. The

results revealed that there was an interaction between KLC3 and

COL3A1 in SKOV3 cells (Fig. 6A).

Furthermore, overexpression of COL3A1 in SKOV3 cells and in

shKLC3-infected cells resulted in alterations in the expression of

DNA damage-related genes and EMT-related genes; the expression

levels of XRCC1, XRCC2, PALB2, N-cadherin, Snail and Vimentin were

increased, whereas E-cadherin expression was decreased compared

with in the shKLC3 group (Fig. 6B, C

and E). Following overexpression of COL3A1, similar effects

were observed when comparing it to knocking down KLC3 alone.

Similarly, the overexpression of COL3A1 stimulated activation of

the PI3K/AKT pathway, and overexpression of COL3A1 reversed the

inhibitory effects of shKLC3 (Fig.

6D). The results of clonogenic (Fig. 6F), wound healing (Fig. 6G) and Transwell (Fig. 6H) assays revealed that the migratory

and proliferative capabilities were increased in the shKLC3 +

COL3A1 group compared with those in the shKLC3 group. These

findings suggested that KLC3 may activate the PI3K/AKT pathway by

interacting with COL3A1 and could contribute to the malignant

functions of OC cells.

| Figure 6.Effects of KLC3 knockdown on OC cells

can be reversed by COL3A1 overexpression. (A) KLC3 and COL3A1 in

SKOV3 cells can be co-immunoprecipitated. (B) Western blot analysis

of COL3A1 expression. (C) Western blot analysis of

epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related proteins. (D) Western

blot analysis of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway proteins. (E) Western

blot analysis of PALB2, XRCC1 and XRCC2 expression. (F) Recovery

experiment of the changes in proliferation of OC cells after

knocking down KLC3 and overexpressing COL3A1. (G) Recovery of OC

cell migration after knockdown of KLC3 and overexpression of

COL3A1. (H) Migratory ability of OC cells was observed by Transwell

assay. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. shKLC3 or as

indicated. COL3A1, collagen type III α1; IP, immunoprecipitation;

OC, ovarian cancer; KLC3, kinesin light chain 3; NC, negative

control; ns, not significant; p-, phosphorylated; sh, short

hairpin. |

Discussion

In eukaryotic cells, the transportation of all

structures to specific locations at precise times relies on

microtubules, with kinesin proteins providing essential energy for

this process (23). Aberrant

expression of kinesin proteins has been reported to be linked to

various types of cancer, including OC, and is associated with

prognosis, proliferation, metastasis and drug resistance (24–27).

Additionally, kinesin proteins serve a pivotal role in diverse

biological processes within tumors by participating in the gene

transcription and translation, and division of tumor cells

(25). In recent years, kinesin

proteins have garnered notable attention as a novel target for

tumor therapy (5–12). However, the association between KLC3

and tumors has been relatively understudied, particularly in

relation to OC. In the present study, data from the GEPIA and GEO

databases revealed high expression levels of KLC3 in OC.

Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier plotter analysis demonstrated that higher

KLC3 expression levels were associated with a poorer prognosis in

patients with OC.

In the present study, western blot analysis was

employed to validate the expression of KLC3 in five normal ovarian

tissue samples and five OC samples. The overall expression of KLC3

was revealed to be significantly higher in OC tissues compared with

that in normal tissues. Subsequently, IHC was utilized to evaluate

the protein expression of KLC3 in OC specimens. The experimental

findings demonstrated an upregulation of KLC3 in OC tissues. Based

on the differential expression levels of KLC3 in OC tissues,

patients were stratified into high and low expression groups.

Patients with lower KLC3 expression exhibited a more favorable

prognosis, which was consistent with the results of bioinformatics

analysis. Unfortunately, owing to the limited availability of OC

samples, the present study was unable to amass a sufficient number

of samples to validate the association between KLC3 expression and

clinical characteristics. Future studies should aim to increase the

sample size to address this limitation. These collective findings

suggested that KLC3 may represent a novel oncogene in OC.

EMT has a crucial role in embryonic morphogenesis,

and confers tumor cells with motility, stemness, drug resistance

and microenvironmental adaptability during cancer progression

(28). Early dissemination is a

hallmark of OC, where metastasizing cancer cells undergo diverse

transformation patterns, such as acquiring mesenchymal

characteristics closely associated with EMT. Furthermore, the

hematogenous and lymphatic spread of advanced-stage OC cells is

intricately linked to EMT (29,30).

Previous research has indicated the involvement of certain members

of the motor protein family in EMT (9). Building on this knowledge, the current

study investigated the association between KLC3 and EMT in OC. The

findings revealed that alterations in KLC3 led to changes in the

expression levels of proteins related to EMT progression, including

N-cadherin, Snail, Vimentin and E-cadherin; thus confirming that

overexpression of KLC3 may enhance the process of EMT in OC

cells.

Enhanced radioresistance of lung cancer cells has

been demonstrated to be associated with the overexpression of KLC2

and KLC4, which is considered to be linked to anti-DNA damage

mechanisms. Additionally, KLC4 deficiency has been shown to trigger

the DNA damage response (6,7). Building on these findings, the present

study investigated the association between KLC3 and DNA damage. The

comet assay results revealed that downregulation of KLC3 led to an

increase in DNA damage in OC cells, thus indicating a notable

association between KLC3 and OC cell resistance to DNA damage.

The COL3A1 protein is predominantly present in

stromal cells and is primarily synthesized by fibroblasts,

contributing to the development of extracellular matrix, cellular

adhesion and tissue remodeling processes (31). Previous research has indicated an

upregulation of COL3A1 mRNA expression in various tumors, such as

breast cancer, lung cancer, gastric cancer, OC and esophageal

cancer (32). Elevated levels of

COL3A1 have been linked to increased proliferation, invasion,

migration and drug resistance in multiple tumor types, including OC

(33–36). RNA-seq technology has been

extensively utilized for fundamental research purposes, as well as

clinical diagnostics and pharmaceutical advancements (37). In the present study, RNA-seq

analysis was employed to identify alterations in gene expression

within the SKOV3 OC cell line following KLC3 downregulation. The

findings were subsequently validated through RT-qPCR analysis and

western blotting, alongside a literature review. Additionally,

co-IP experiments confirmed the interaction between KLC3 and

COL3A1, ultimately establishing COL3A1 as a downstream target of

KLC3. Furthermore, sequencing results highlighted significant

enrichment of the PI3K/AKT pathway. It is well-established that

activation of PI3K/AKT promotes metastasis in OC (38,39),

while also inhibiting apoptosis through DNA repair mechanisms and

promoting drug resistance (40,41).

Building upon this foundation, the present study explored the

relationship between KLC3 and the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in OC,

and revealed that reduced KLC3 expression did not impact PI3K or

AKT levels but led to decreased p85α and p-AKT expression;

conversely overexpression of KLC4 activated this pathway.

Collectively these findings indicated the involvement of KLC4 in OC

progression with implications for EMT processes and DNA damage.

After knocking down KLC3 and overexpressing COL3A1

in SKOV3 OC cells, an increase in the expression levels of

N-cadherin, Snail and Vimentin was detected compared with in the

knockdown group, whereas E-cadherin expression was decreased.

Additionally, XRCC1, XRCC2 and PALB2 exhibited increased expression

compared with in the knockdown group. These results suggested that

the overexpression of COL3A1 could partially mitigate the weakened

malignant function of OC cells caused by reduced KLC3

expression.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study

indicated that KLC3 may facilitate the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway,

and promote the proliferation and migration of OC cells via COL3A1.

These findings suggested a novel mechanism of action for KLC3 in

the pathogenesis of OC, thus highlighting its potential as a

promising target for OC therapy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by The Gansu Province Health

Industry Scientific Research Plan Project (grant no.

GSWSHL2022_34).

Availability of data and materials

The RNA-seq data generated in the present study may

be found in the Sequence Read Archive under accession number

PRJNA1137301 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA1137301.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JY and YL designed the present study. XZ analyzed

the data and wrote the manuscript. ML, XW and XL collected the

data. RH, XL and ML analyzed the data. YL revised the manuscript.

JY and YL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The use of patient tissues was approved by the

Institutional Ethics Committee of The First Hospital of Lanzhou

University (approval no. LDYYLL-2019-279). Written informed consent

was obtained from the patients prior to sample collection. In

vivo experiments were conducted with the approval of the Animal

Experimental Ethics Committee of The First Hospital of Lanzhou

University of (approval no. LDYYLL-2023-495).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cui W, Rocconi RP, Thota R, Anderson RA,

Bruinooge SS, Comstock IA, Denduluri N, Gassman A, Gralow J, Hutt

KJ, et al: Measuring ovarian toxicity in clinical trials: An

American society of clinical oncology research statement. Lancet

Oncol. 24:e415–e423. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Godbole N, Quinn A, Carrion F, Pelosi E

and Salomon C: Extracellular vesicles as a potential delivery

platform for CRISPR-Cas based therapy in epithelial ovarian cancer.

Semin Cancer Biol. 96:64–81. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rayment I: Kinesin and myosin: Molecular

motors with similar engines. Structure. 4:501–504. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhong M, Gong L, Li N, Guan H, Gong K,

Zhong Y, Zhu E, Wang X, Jiang S, Li J, et al: Pan-cancer analysis

of kinesin family members with potential implications in prognosis

and immunological role in human cancer. Front Oncol.

13:11798972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Qiao S, Jiang Y, Li N and Zhu X: The

kinesin light chain-2, a target of mRNA stabilizing protein HuR,

inhibits p53 protein phosphorylation to promote radioresistance in

NSCLC. Thorac Cancer. 14:1440–1450. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Baek JH, Yun HS, Kim JY, Lee J, Lee YJ,

Lee CW, Song JY, Ahn J, Park JK, Kim JS, et al: Kinesin light chain

4 as a new target for lung cancer chemoresistance via targeted

inhibition of checkpoint kinases in the DNA repair network. Cell

Death Dis. 11:3982020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Baek JH, Lee J, Yun HS, Lee CW, Song JY,

Um HD, Park JK, Park IC, Kim JS, Kim EH and Hwang SG: Kinesin light

chain-4 depletion induces apoptosis of radioresistant cancer cells

by mitochondrial dysfunction via calcium ion influx. Cell Death

Dis. 9:4962018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Feng S, Luo S, Ji C and Shi J: miR-29c-3p

regulates proliferation and migration in ovarian cancer by

targeting KIF4A. World J Surg Oncol. 18:3152020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sheng N, Xu YZ, Xi QH, Jiang HY, Wang CY,

Zhang Y and Ye Q: Overexpression of KIF2A is suppressed by miR-206

and associated with poor prognosis in ovarian cancer. Cell Physiol

Biochem. 50:810–822. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Li H, Zhang W, Sun X, Chen J, Li Y, Niu C,

Xu B and Zhang Y: Overexpression of kinesin family member 20A is

associated with unfavorable clinical outcome and tumor progression

in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 10:3433–3450. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kawai Y, Shibata K, Sakata J, Suzuki S,

Utsumi F, Niimi K, Sekiya R, Senga T, Kikkawa F and Kajiyama H:

KIF20A expression as a prognostic indicator and its possible

involvement in the proliferation of ovarian clear-cell carcinoma

cells. Oncol Rep. 40:195–205. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Han X, Yang L, Tian H and Ji Y: Machine

learning developed a PI3K/Akt pathway-related signature for

predicting prognosis and drug sensitivity in ovarian cancer. Aging

(Albany NY). 15:11162–11183. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Konjikusic MJ, Gray RS and Wallingford JB:

The developmental biology of kinesins. Dev Biol. 469:26–36. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yu L, Wei J and Liu P: Attacking the

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway for targeted therapeutic treatment

in human cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 85:69–94. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li H, Zeng J and Shen K: PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway as a therapeutic target for ovarian cancer. Arch

Gynecol Obstet. 290:1067–1078. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ediriweera MK, Tennekoon KH and Samarakoon

SR: Role of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in ovarian cancer:

Biological and therapeutic significance. Semin Cancer Biol.

59:147–160. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yoshihara K, Tajima A, Komata D, Yamamoto

T, Kodama S, Fujiwara H, Suzuki M, Onishi Y, Hatae M, Sueyoshi K,

et al: Gene expression profiling of advanced-stage serous ovarian

cancers distinguishes novel subclasses and implicates ZEB2 in tumor

progression and prognosis. Cancer Sci. 100:1421–1428. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Mok SC, Bonome T, Vathipadiekal V, Bell A,

Johnson ME, Wong KK, Park DC, Hao K, Yip DK, Donninger H, et al: A

gene signature predictive for outcome in advanced ovarian cancer

identifies a survival factor: Microfibril-associated glycoprotein

2. Cancer Cell. 16:521–532. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

O'Shea AS: Clinical staging of ovarian

cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2424:3–10. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Dixon JR Jr: The International conference

on harmonization good clinical practice guideline. Qual Assur.

6:65–74. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, Chang M,

Khodabakhshi AH, Tanaseichuk O, Benner C and Chanda SK: Metascape

provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of

systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 10:15232019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Tjioe M, Shukla S, Vaidya R, Troitskaia A,

Bookwalter CS, Trybus KM, Chemla YR and Selvin PR: Multiple

kinesins induce tension for smooth cargo transport. Elife.

8:e509742019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Cong S, Fu Y, Zhao X, Guo Q, Liang T, Wu

D, Wang J and Zhang G: KIF26B and CREB3L1 derived from immunoscore

could inhibit the progression of ovarian cancer. J Immunol Res.

2024:48179242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liu X, Gong H and Huang K: Oncogenic role

of kinesin proteins and targeting kinesin therapy. Cancer Sci.

104:651–656. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li X, Huang W, Huang W, Wei T, Zhu W, Chen

G and Zhang J: Kinesin family members KIF2C/4A/10/11/14/18B/20A/23

predict poor prognosis and promote cell proliferation in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Transl Res. 12:1614–1639.

2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Liang LY and Li GS: The Roles of KIFC1 in

the development of osteosarcoma: Characterization of potential

therapeutic targets. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022:50391342022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhang G, Hou S, Li S, Wang Y and Cui W:

Role of STAT3 in cancer cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(Review). Int J Oncol. 64:482024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Śliwa A, Szczerba A, Pięta PP, Białas P,

Lorek J, Nowak-Markwitz E and Jankowska A: A recipe for successful

metastasis: Transition and migratory modes of ovarian cancer cells.

Cancers (Basel). 16:7832024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Szczerba A, Śliwa A, Pieta PP and

Jankowska A: The role of circulating tumor cells in ovarian cancer

dissemination. Cancers(Basel). 14:60302022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kuivaniemi H and Tromp G: Type III

collagen (COL3A1): Gene and protein structure, tissue distribution,

and associated diseases. Gene. 707:151–171. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhang H, Ding C, Li Y, Xing C, Wang S, Yu

Z, Chen L, Li P and Dai M: Data mining-based study of collagen type

III alpha 1 (COL3A1) prognostic value and immune exploration in

pan-cancer. Bioengineered. 12:3634–3646. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Januchowski R, Świerczewska M, Sterzyńska

K, Wojtowicz K, Nowicki M and Zabel M: Increased expression of

several collagen genes is associated with drug resistance in

ovarian cancer cell lines. J Cancer. 7:1295–1310. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Xu W, Li Z, Zhu X, Xu R and Xu Y: miR-29

family inhibits resistance to methotrexate and promotes cell

apoptosis by targeting COL3A1 and MCL1 in osteosarcoma. Med Sci

Monit. 24:8812–8821. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wang L, Sun Y, Guo Z and Liu H: COL3A1

overexpression associates with poor prognosis and cisplatin

resistance in lung cancer. Balkan Med J. 39:393–400. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Gao YF, Zhu T, Chen J, Liu L and Ouyang R:

Knockdown of collagen α-1(III) inhibits glioma cell proliferation

and migration and is regulated by miR128-3p. Oncol Lett.

16:1917–1923. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ozsolak F and Milos PM: RNA sequencing:

Advances, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Genet. 12:87–98.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Wang H, Xu YH and Guo Y: Novel prognostic

marker TGFBI affects the migration and invasion function of ovarian

cancer cells and activates the integrin αvβ3-PI3K-Akt signaling

pathway. J Ovarian Res. 17:502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Li GW, Jin YP, Qiu JP and Lu XF: ITGB2

fosters the cancerous characteristics of ovarian cancer cells

through its role in mitochondrial glycolysis transformation. Aging

(Albany NY). 16:3007–3020. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ma S, Wang J, Cui Z, Yang X, Cui X, Li X

and Zhao L: HIF-2α-dependent TGFBI promotes ovarian cancer

chemoresistance by activating PI3K/Akt pathway to inhibit apoptosis

and facilitate DNA repair process. Sci Rep. 14:38702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Li W, Zhang K, Wang W, Liu Y, Huang J,

Zheng M, Li L, Zhang X, Xu M, Chen G, et al: Combined inhibition of

HER2 and VEGFR synergistically improves therapeutic efficacy via

PI3K-AKT pathway in advanced ovarian cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

43:562024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|