Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) has become a leading

cause of morbidity and mortality in India and worldwide (1,2). In India,

CAD affects younger people (aged <45 years) with a higher

severity resulting in a 4-fold higher incidence compared to the

western population. The present day preventive strategies mainly

depend on the conventional risk factors, such as diabetes,

hypertension, obesity and levels of lipids [including total

cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and

low-density lipoprotein (LDL)]. However, a number of supposedly

healthy people without the majority of these risk factors develop

the disease (3,4). This high prevalence of CAD in Asian

Indians accentuates the requirement for identification of

biomarkers for an improved risk stratification (5,6).

Serum γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels, a

traditional marker of hepatobiliary dysfunction, are positively

associated with atherosclerosis and have prognostic importance. An

increase of 1 U/l of GGT (on a log scale) was found to increase the

risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) by 20%, stroke by 54% and the

combined risk of stroke and CHD by 34% (7). Furthermore, correlation of GGT has been

found with cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension,

stroke, diabetes, dyslipidemia and metabolic syndrome (8). The presence of catalytically active GGT

molecules in the atheromatous plaque also reinforce the association

of GGT with atherosclerosis (9).

However, the association of GGT to premature CAD in Asian Indians

has not yet been evaluated. The present study was undertaken to

investigate the association of plasma GGT levels with CAD in young

Asian Indians and its interaction with other biomarkers for

potential use in an improved risk stratification.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A total of 2,318 subjects were enrolled in the

phase-I of the Indian Atherosclerosis Research Study (IARS)

(10) between 2004–2006, which is a

prospective study designed according to the principles and the

guidelines of World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and

the Indian Council of Medical Research and approved by Thrombosis

Research Institute Ethics committee. Signed informed consent was

obtained from all the participants who were enrolled, and 240 age-

and gender-matched subjects (120 unaffected and 120 affected) were

selected for this study. All the subjects were ≤45 years of age for

males and ≤50 years for females at the onset of the disease. The

individuals with an abnormal electrocardiogram (ECG), positive

angiogram showing >70% stenosis in any one of the coronary

arteries or >50% in two or more arteries and individuals posted

for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery or percutaneous

coronary intervention were considered as CAD subjects. The

unaffected subjects were all healthy volunteers without clinical

signs of CAD, as confirmed by ECG. None of the participants

enrolled in the study had inflammatory disorders, concomitant

infections or any other major illness such as cancer, liver or

renal disease.

Telephonic assessment of cardiac

health status

Periodic telephonic follow-up of all the study

participants was undertaken to obtain an update on the cardiac

health status, and five rounds of follow-up for an average time of

18 months were completed. Endpoints included non-fatal events

(re-do percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty/repeat

CABG/heart attack or stroke) and fatal events (fatal heart

attack/fatal stroke/sudden death or cardiac arrest). This

information was verified through either paper trail or hospital

records, wherever available.

Assessment of risk factors

All the participants were assessed for the presence

of the risk factors by personal interviews, which included

demographics (age, gender, occupation and socio-economic status),

lifestyle, health characteristics (diet, waist circumference,

smoking status and use of alcohol), and medical history

[hypertension and diabetes, systolic and diastolic blood pressure,

LDL and HDL-cholesterol (HDL-c), and triglycerides].

Assessment of lipids

Venous blood samples (20 ml) were collected after

overnight fasting (12 h). The samples were centrifuged at 2,000 × g

for 20 min at 25°C, following which 1 ml aliquots of serum and

plasma were stored at −80°C. Total cholesterol and triglycerides

were measured using reagents and standards from Randox Laboratories

(Antrim, UK) in a Cobas-Fara II Clinical Chemistry auto-analyzer

(Hoffman La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland). For the estimation of

HDL-c, the non-HDL fractions were precipitated with a mixture of

2.4 mmol/l phosphotungstic acid and 39 mmol/l magnesium chloride

(Bayer Diagnostics, Baroda, Gujarat, India) prior to estimation.

The LDL concentration was calculated using the Friedewald formula.

The inter-assay coefficient of variation for commercial controls

and normal human pooled serum/plasma (NHP) was 4.9–7.0% for total

cholesterol, 6.1–7.7% for triglycerides, and 7.1–12.2% for

HDL-c.

Biomarker evaluation

All the plasma or serum biomarkers were measured by

ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) or the

immunoturbidometric method. Plasma GGT and high-sensitivity

C-reactive protein (hsCRP) concentrations were measured using a

Flex reagent cartridge in Dimension XpandPlus Integrated Chemistry

system (Siemens, Germany). Lipoprotein (a) [lp(a)] (Randox

Laboratories) was measured in the Cobas-Fara II Clinical Chemistry

auto-analyzer. Plasma levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6), cystatin C

(R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), neopterin (IBL

International, Atlanta, GA, USA), myeloperoxidase (MPO) (Mercodia,

Uppasala, Sweden) and tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of

apoptosis (TWEAK) (eBiosciences, Vienna, Austria) were measured

using ELISA kits. The secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) was

measured by a sandwich immunometric assay (Cayman Corporation, Ann

Arbor, MI, USA). The inter-assay coefficient of variation of

in-house controls (NHP) was 4.40% for GGT, 5.2% for lp(a), 4.3% for

IL-6, 5.37% for sPLA2, 7.85% for hsCRP, 5.99 to 11.8% for

neopterin, 11.8% for cystatin C, 9.3% for myeloperoxidase, and 7%

for TWEAK.

Statistical analysis

The variations in the baseline characteristics

between the unaffected and affected subjects were studied using the

Student's t-test and univariate analysis of variance for

quantitative variables. The quantitative parameters were adjusted

for age, gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and smoking.

χ2 test was used to assess the association of discrete

outcomes with premature CAD. Results are represented as mean ±

standard error for quantitative variables, whereas the discrete

outcomes were represented as frequencies. The Shapiro-Wilk and

Kolmogorove-Smirnov test were used to assess the normality of the

data. The data with skewed distribution were natural

log-transformed. The association of GGT with lipids, inflammatory

and oxidative stress markers was evaluated by Pearson's correlation

for quantitative variables and partial correlation was used for

conventional risk factors (CRFs; which were age, gender,

hypertension diabetes mellitus and smoking) adjusted analysis. The

association of GGT with discrete outcomes was evaluated using

χ2 test.

In order to review the association between higher

levels of GGT and incidence of premature CAD, GGT levels were

categorized in to tertiles. The odds ratios (OR) with 95%

confidence interval (CI) were obtained by comparing top tertiles,

considering the first tertile as the reference category using

logistic regression analysis. The logistic regression analysis was

also used to build different models with multiple markers having

GGT in common. The discriminative ability of a significant model

with the highest OR was evaluated using receiver operating

characteristic analysis. The significance of improvement in the

area under the curve (AUC) between CRF and GGT + CRF models was

assessed using DeLong's test. A two-tailed P-value <0.05% was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. All

the above statistical analyses were carried out using statistical

package for social sciences (SPSS) version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc.,

Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics of

unaffected subjects and premature CAD patients

The clinical characteristics of the 240 age- and

gender-matched study subjects (120 affected and 120 unaffected) are

provided in Table I. The CAD-affected

subjects showed a high frequency of hypertension and diabetes, and

low levels of HDL-c compared to the unaffected subjects. The

frequency of smokers was also significantly higher in the

CAD-affected group. The affected subjects showed a lower level of

LDL compared to the unaffected, possibly due to statin usage in

this group. Six out of 9 protein markers assayed in the present

study were significantly different between the affected and

unaffected subjects. As shown in Table

I, the mean GGT levels were significantly higher in

CAD-affected subjects in comparison with the unaffected subjects

(34.48±1.00 vs. 30.94±0.90 U/l; P=0.009) and similar results were

also obtained for lp(a) (27.20±2.34 vs. 18.70±1.55 mg/dl;

P=0.019).

| Table I.Baseline characteristics of the study

population. |

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the study

population.

| Variables | Unaffected,

n=120 | Affected, n=120 | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 41.78±0.40 | 41.79±0.40 | 0.988 |

| Age at onset,

years | – | 39.50±0.43 | – |

| Waist circumference,

cm | 89.57±0.85 | 88.41±0.87 | 0.341 |

| Gender, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

Males | 93 (77.5) | 93 (77.5) | 1.00 |

|

Females | 27 (22.5) | 27 (22.5) |

|

| Smoking, n (%) | 30 (25.0) | 55 (45.8) | 0.001 |

| Alcohol habit, n

(%) | 24 (20.0) | 16 (13.3) | 0.053 |

| Hypertension, n

(%) | 19 (15.8) | 45 (37.5) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 16 (13.3) | 32 (26.7) | 0.007 |

| Total cholesterol,

mg/dl | 181.83±3.94 | 154.00±3.45 | <0.001 |

| Triglyceride,

mg/dl | 150.20±8.30 | 163.17±6.26 | 0.152 |

| High-density

lipoprotein, mg/dl | 39.00±0.88 | 35.97±0.76 | 0.010 |

| Low-density

lipoprotein, mg/dl | 112.78±3.36 | 85.35±3.14 | <0.001 |

| γ-glutamyl

transferase, U/l | 30.94±0.90 | 34.48±1.00 | 0.009 |

| Secretory

phospholipase A2, pg/ml | 2,518.02±130.67 | 2,720.00±130.15 | 0.027 |

| Lipoprotein (a),

mg/dl | 18.70±1.55 | 27.20±2.34 | 0.019 |

| Myeloperoxidase,

µg/l | 304.61±14.73 | 356.51±19.89 | 0.037 |

| Neopterin,

nmol/l | 7.65±0.32 | 8.50±0.34 | 0.034 |

| Interleukin-6,

pg/ml | 2.98±0.15 | 3.66±0.19 | 0.006 |

| Cystatin C,

ng/ml | 1,053.61±30.43 | 1,058.03±32.74 | 0.899 |

| High-sensitivity

C-reactive protein, mg/dl | 2.35±0.18 | 2.32±0.19 | 0.599 |

| Tumor necrosis

factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis, pg/ml | 355.94±30.95 | 347.00±17.99 | 0.802 |

| Statins, n (%) | 5 (4.2) | 82 (68.3) | <0.001 |

Correlation of GGT levels with

inflammatory and lipid markers

The GGT levels showed a significant

moderate-positive correlation with the oxidative stress marker

neopterin, and remained borderline significant following adjustment

for the age, gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and smoking

(Table II). GGT was also positively

correlated to triglyceride levels and waist circumference, and

remained significant following adjustment with age, gender,

hypertension, diabetes mellitus and smoking (all the significant

correlation coefficients were <0.3).

| Table II.Correlation of γ-glutamyl transferase

(GGT) levels with oxidative stress, inflammatory markers and lipid

markers. |

Table II.

Correlation of γ-glutamyl transferase

(GGT) levels with oxidative stress, inflammatory markers and lipid

markers.

|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristics | Correlation | P-value | Correlation | P-value |

|---|

| Lipoprotein (a),

mg/dl | 0.050 | 0.465 | 0.050 | 0.480 |

| Secretory

phospholipase A2, pg/ml | 0.036 | 0.584 | 0.092 | 0.165 |

| Interleukin-6,

pg/ml | 0.090 | 0.164 | 0.093 | 0.161 |

| Myeloperoxidase,

µg/l | 0.106 | 0.102 | 0.068 | 0.310 |

| Neopterin,

nmol/l | 0.172 | 0.008 | 0.127 | 0.050 |

| Total cholesterol,

mg/dl | 0.110 | 0.090 | 0.136 | 0.041 |

| High-density

lipoprotein, mg/dl | −0.035 | 0.587 | 0.012 | 0.862 |

| Low-density

lipoprotein, mg/dl | 0.001 | 0.993 | 0.043 | 0.519 |

| Triglyceride,

mg/dl | 0.292 | <0.001 | 0.168 | 0.011 |

| Waist circumference,

cm | 0.252 | <0.001 | 0.251 | <0.001 |

Cross-sectional correlation was carried out to

understand the association between GGT and binary outcomes. The

present analysis did not observe any association of hypertension,

diabetes and alcohol habit with GGT levels (Table III). The number of smokers in the

second and third tertile of GGT was higher in comparison to the

first, and there was a positive association between GGT levels and

smoking.

| Table III.Cross-sectional correlation of binary

outcomes with γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT). |

Table III.

Cross-sectional correlation of binary

outcomes with γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT).

|

| GGT tertiles |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

Characteristics | Tertile 1

(<22.59 U/l) (n=86) | Tertile 2

(22.59–32.21 U/l) (n=71) | Tertile 3 (≥32.21

U/l) (n=83) | P-value |

|---|

| Smoking, n (%) | 19 (22.1) | 26 (36.6) | 40 (48.2) | 0.002 |

| Hypertension, n

(%) | 17 (19.8) | 22 (31.0) | 25 (30.1) | 0.194 |

| Diabetes melitus, n

(%) | 14 (16.3) | 15 (21.1) | 19 (22.9) | 0.539 |

| Alcohol habits, n

(%) | 10 (11.6) | 14 (19.7) | 16 (19.3) | 0.293 |

Association of GGT tertiles with

CAD

In comparison to the low GGT level of <22.59 U/l

reference group, the high GGT levels of ≥32.21 U/l (third tertile)

showed an OR of 1.909 (95% CI, 1.036–3.517; P=0.038). Following

adjustment to the GGT-associated risk factors and CAD risk factors,

the OR increased to 2.104 (95% CI, 1.063–4.165; P=0.033), i.e., the

subjects with GGT levels of ≥32.21 U/l had a 2.11-fold higher risk

of premature CAD in comparison to <22.59 U/l. The intermediate

GGT levels (second tertile) group did not show any association with

premature CAD prior and subsequent to adjustment to the

conventional risk factors (Table

IV).

| Table IV.Risk of coronary artery disease

events based on γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) tertiles. |

Table IV.

Risk of coronary artery disease

events based on γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) tertiles.

|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| GGT tertiles | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Tertile 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Tertile 2 | 1.212

(0.647–2.289) | 0.542 | 1.057

(0.528–2.117) | 0.875 |

| Tertile 3 | 1.909

(1.036–3.517) | 0.038 | 2.104

(1.063–4.165) | 0.033 |

Risk association assessment

The logistic regression model was used to assess the

risk predictive ability of GGT alone and along with lipid,

inflammatory, oxidative stress markers and conventional risk

factors. GGT alone was found to have an OR of 4.94 (95% CI,

1.015–24.095; P=0.048), which improved to 5.208 (95% CI,

1.018–24.624; P=0.048) upon adjusting for the conventional risk

factors. The OR of this model further improved to 5.64 (95% CI,

1.004–31.642; P=0.049) upon addition of lp(a). The above

combination of GGT and lp(a) exhibited a higher odds ratio of 7.492

(95% CI, 1.221–45.979; P=0.030) (Table

V) following adjustment for CRFs.

| Table V.Association of γ-glutamyl transferase

(GGT) levels with coronary artery disease in the presence of lipid,

inflammatory and oxidative stress markers. |

Table V.

Association of γ-glutamyl transferase

(GGT) levels with coronary artery disease in the presence of lipid,

inflammatory and oxidative stress markers.

|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Model | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Lipid and

inflammatory markers |

|

|

|

|

GGT | 4.944

(1.015–24.095) | 0.048 | 5.208

(1.018–24.624) | 0.048 |

|

+Lipoprotein (a) | 5.636

(1.004–31.642) | 0.049 | 7.492

(1.221–45.979) | 0.030 |

|

+Secretory phospholipase

A2 | 4.829

(0.972–23.980) | 0.054 | 5.138

(0.952–27.742) | 0.057 |

|

+Interleukin-6 | 4.445

(0.972–22.011) | 0.068 | 4.691

(0.866–25.339) | 0.073 |

| Oxidative stress

markers |

|

+Myeloperoxidase | 3.485

(1.199–10.128) | 0.022 | 4.555

(0.849–24.443) | 0.077 |

|

+Neopterin | 3.816

(0.746–19.060) | 0.103 | 4.041

(0.741–21.923) | 0.105 |

The addition of MPO to the GGT was significant with

a reduction in the OR of GGT from 4.94 to 3.48; however, the

significance of the model was lost following adjustment with CRFs

(Table V). Other inflammatory and

oxidative stress markers did not add any significant value to the

predictive ability of the GGT.

Discriminative ability of the

model

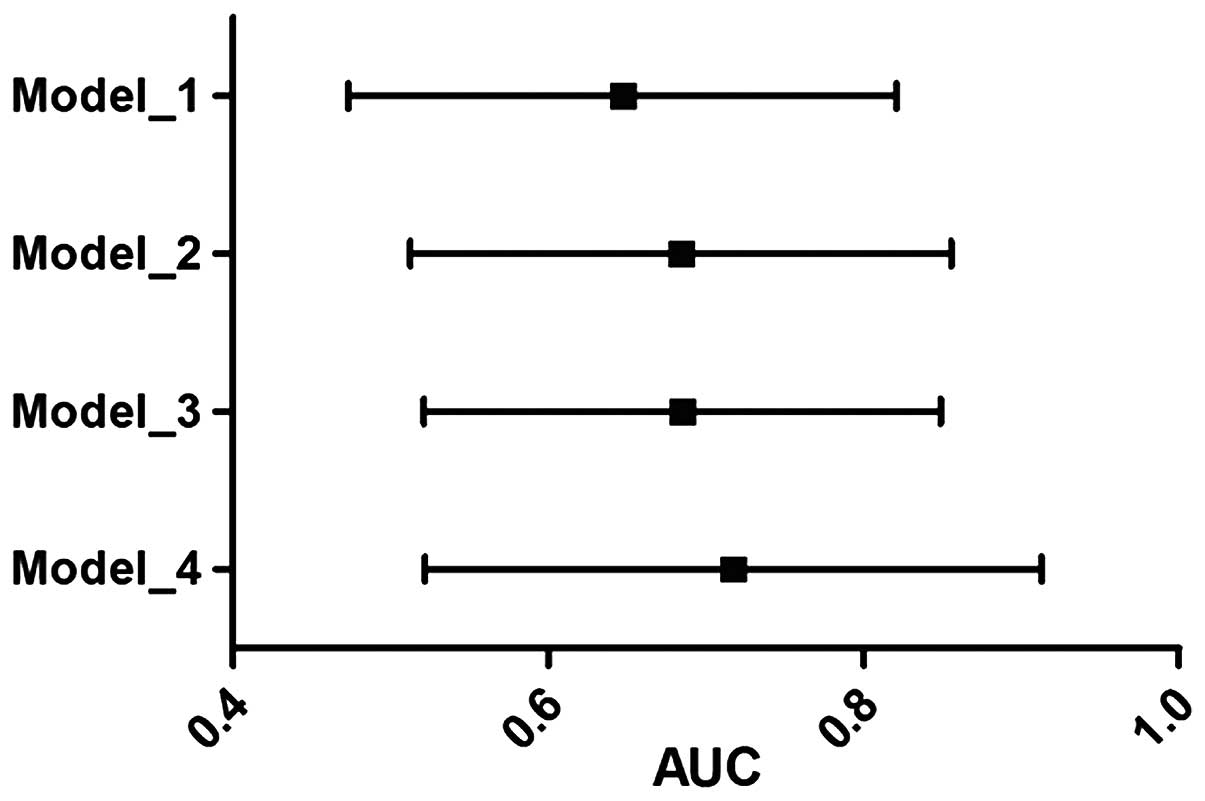

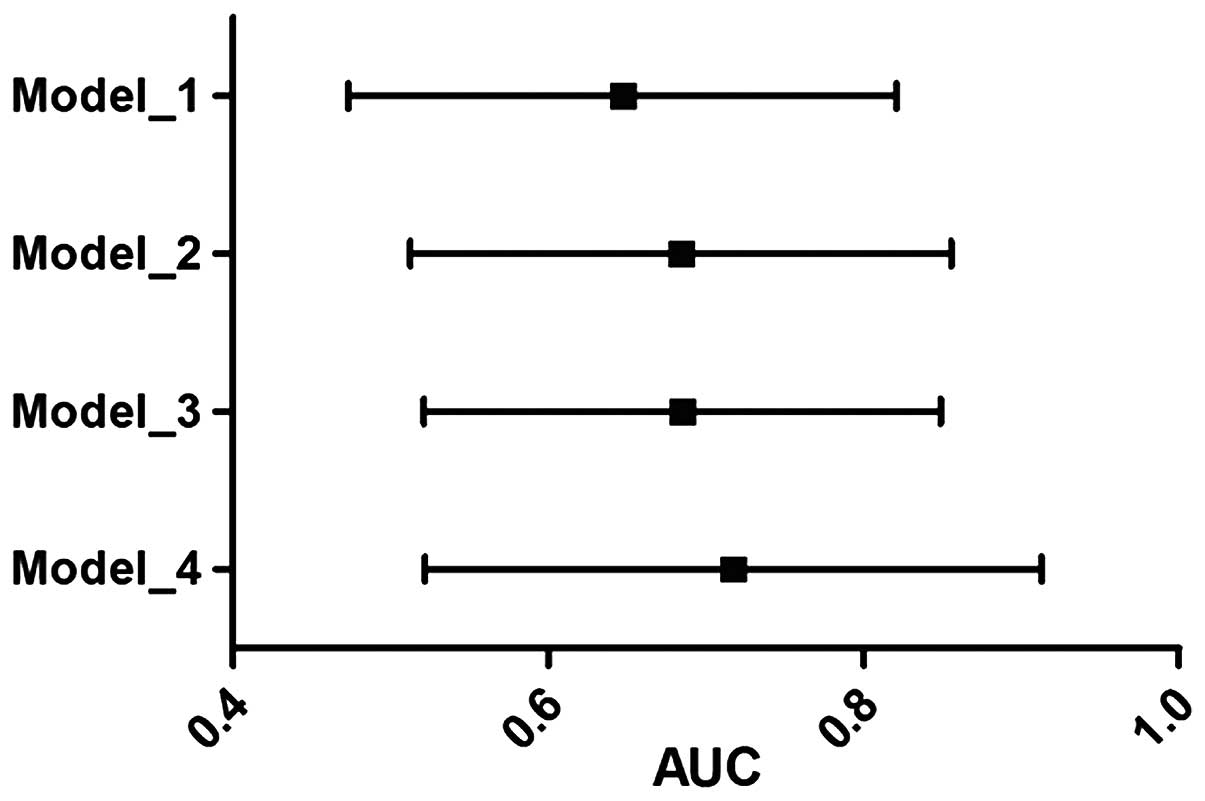

The C-statistic analysis was performed to assess the

discriminative ability of the models built using logistic

regression (Fig. 1). The

discriminative ability of GGT alone was tested and compared with

the other models. The GGT alone significantly classified the 61.5%

population correctly. However, conventional risk factors used in

the model building exhibited an AUC of 0.647 (95% CI, 0.577–0.717;

P<0.001). The GGT and lp(a) together increased the AUC to 0.654

(95% CI, 0.576–0.732; P<0.001). A combined model of GGT and

lp(a) plus conventional risk factors showed the best performance

with an AUC of 0.711 (95% CI, 0.642–0.799; P<0.001). The

DeLong's test indicated that the improvement of AUC from CRF to

biomarkers [GGT + lp(a)] adjusted to CRFs was significant

(P<0.001). All the models built were tested for best-fit using

the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

| Figure 1.AUC of four different models with

corresponding confidence intervals. Model 1, GGT alone; model 2,

conventional risk factors (age, gender, smoking, hypertension and

diabetes melitus); model 3, GGT + lp(a); model 4, GGT + lp(a) +

conventional risk factors. AUC, area under the curve; GGT,

γ-glutamyl transferase; lp(a), lipoprotein (a). |

Discussion

The key outcomes of the present study were two-fold.

The first section of the results suggest that increasing GGT levels

were associated with the CAD risk factors, such as smoking,

hyperlipidemia, waist circumference and oxidative stress marker

neopterin, indicating a possible existence of a condition such as

oxidative stress in the subjects. The second section of the results

indicates that higher levels of GGT in the blood are associated

with an increased risk of premature CAD. However, the other major

risk factors, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and

dyslipidemia, were not associated with GGT levels but were

significantly associated with the premature CAD. Therefore, we

adjusted the GGT levels with these risk factors and the association

remained significant following adjustment. This suggests that

increased GGT levels could act as an independent factor in the

process of premature CAD development in the Indian population.

Previously a number of studies have shown the

association of increased GGT levels with CAD risk factors and CAD

development (11–14); however, to best of our knowledge there

are no studies showing the association of increased GGT levels with

premature CAD in the Indian population. In the present study, a

pilot investigation was performed to show this possible association

between premature CAD and GGT levels. The findings indicate that

young subjects in the highest tertile have a 2.1-fold higher risk

with respect to reference tertile (Table

IV) and a unit increase of GGT levels (on a log scale)

increases the risk of premature CAD by 5-fold, which increased to

7-fold in the presence of higher lp(a) levels (Table V).

The results of the present study indicate the

association of GGT levels with premature CAD, which was independent

of alcohol habits. However, the correlation between GGT, smoking,

triglycerides, waist circumference and neopterin levels indicates a

potential mechanism in the development of the disease. Experimental

evidence suggests that GGT, by regulating intracellular

glutathione, acts as an antioxidant (15,16). Whereas

GGT has been shown to have a prooxidant role by producing reactive

oxygen species in the presence of transition metal ions (such as

iron) (17–19), which can lead to endothelial

dysfunction. However, this increased deposition of iron could be

due to smoking and may contribute to the endothelial dysfunction

(20). In addition, our previous study

also revealed reduced adiponectin levels in CAD subjects (21). Kozakova et al (22) reported the importance of GGT linking

fatty liver condition and atherosclerosis potentially by regulating

the adiponectin level. In accordance with these findings, the

present data suggests that in a fatty liver condition, higher GGT

levels may indicate the migration of aortic SMC into the intimal

layer, and hence, inducing the atherosclerotic condition. In

conclusion, elevated plasma GGT levels may indicate an increased

risk of developing premature CAD.

There were strengths and limitations of the present

study. The present study was carried out on a relatively small

sample size, and requires further validation on larger subjects.

However, this preliminary data revealed GGT as one of the risk

factors and biomarkers in premature CAD subjects. GGT is a low cost

and readily available assay, thus, validating in a larger cohort

and translating the findings into clinical practice would be

comparatively easy.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support of the

funding agencies: Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science

and Technology, Government of India (grant no. BT/01/CDE/08/07),

the Tata Social Welfare Trust, India (grant no.

TSWT/IG/SNB/JP/Sdm), Garfield Weston Foundation, UK, Foundation

Bay, UK and Bharati Foundation, India. The authors thank all the

investigators, staff, and administrative teams and participants of

IARS from Narayana Hrudayalaya, Bangalore and Asian Heart Centre

(Mumbai) for their contribution. The authors are grateful to the

patients and their family members for participating in the

study.

References

|

1

|

Kanjilal S, Rao VS, Mukherjee M, Natesha

BK, Renuka KS, Sibi K, Iyengar SS and Kakkar VV: Application of

cardiovascular disease risk prediction models and the relevance of

novel biomarkers to risk stratification in Asian Indians. Vasc

Health Risk Manag. 4:199–211. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mathers CD and Loncar D: Projections of

global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med.

3:e4422006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Greenland P, Knoll MD, Stamler J, Neaton

JD, Dyer AR, Garside DB and Wilson PW: Major risk factors as

antecedents of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease events.

JAMA. 290:891–897. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Khot UN, Khot MB, Bajzer CT, Sapp SK,

Ohman EM, Brener SJ, Ellis SG, Lincoff AM and Topol EJ: Prevalence

of conventional risk factors in patients with coronary heart

disease. JAMA. 290:898–904. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Goyal A and Yusuf S: The burden of

cardiovascular disease in the Indian subcontinent. Indian J Med

Res. 124:235–244. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sharma M and Ganguly NK: Premature

coronary artery disease in Indians and its associated risk factors.

Vasc Health Risk Manag. 1:217–225. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Atar AI, Yilmaz OC, Akin K, Selcoki Y, Er

O and Eryonucu B: Association between gamma-glutamyltransferase and

coronary artery calcification. Int J Cardiol. 167:1264–1267. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Poelzl G, Eberl C, Achrainer H, Doerler J,

Pachinger O, Frick M and Ulmer H: Prevalence and prognostic

significance of elevated gamma-glutamyltransferase in chronic heart

failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2:294–302. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Paolicchi A, Emdin M, Ghliozeni E, Ciancia

E, Passino C, Popoff G and Pompella A: Images in cardiovascular

medicine. Human atherosclerotic plaques contain gamma-glutamyl

transpeptidase enzyme activity. Circulation. 109:14402004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Shanker J, Maitra A, Rao VS, Mundkur L,

Dhanalakshmi B, Hebbagodi S and Kakkar VV: Rationale, design &

preliminary findings of the Indian atherosclerosis research study.

Indian Heart J. 62:286–295. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Dhingra R, Gona P, Wang TJ, Fox CS,

D'Agostino RB Sr and Vasan RS: Serum gamma-glutamyl transferase and

risk of heart failure in the community. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc

Biol. 30:1855–1860. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Emdin M, Passino C, Michelassi C, Donato

L, Pompella A and Paolicchi A: Additive prognostic value of

gamma-glutamyltransferase in coronary artery disease. Int J

Cardiol. 136:80–85. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ruttmann E, Brant LJ, Concin H, Diem G,

Rapp K and Ulmer H: Vorarlberg Health Monitoring and Promotion

Program Study Group: Gamma-glutamyltransferase as a risk factor for

cardiovascular disease mortality: An epidemiological investigation

in a cohort of 163,944 Austrian adults. Circulation. 112:2130–2137.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wannamethee G, Ebrahim S and Shaper AG:

Gamma-glutamyltransferase: Determinants and association with

mortality from ischemic heart disease and all causes. Am J

Epidemiol. 142:699–708. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Karp DR, Shimooku K and Lipsky PE:

Expression of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase protects ramos B cells

from oxidation-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 276:3798–3804.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Takahashi Y, Oakes SM, Williams MC,

Takahashi S, Miura T and Joyce-Brady M: Nitrogen dioxide exposure

activates gamma-glutamyl transferase gene expression in rat lung.

Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 143:388–396. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Paolicchi A, Tongiani R, Tonarelli P,

Comporti M and Pompella A: gamma-Glutamyl transpeptidase-dependent

lipid peroxidation in isolated hepatocytes and HepG2 hepatoma

cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 22:853–860. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Stark AA: Oxidative metabolism of

glutathione by gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and peroxisome

proliferation: The relevance to hepatocarcinogenesis. A hypothesis.

Mutagenesis. 6:241–245. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Stark AA, Russell JJ, Langenbach R, Pagano

DA, Zeiger E and Huberman E: Localization of oxidative damage by a

glutathione-gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase system in preneoplastic

lesions in sections of livers from carcinogen-treated rats.

Carcinogenesis. 15:343–348. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fukami K, Yamagishi S, Iida S, Matsuoka H

and Okuda S: Involvement of iron-evoked oxidative stress in

smoking-related endothelial dysfunction in healthy young men. PLoS

One. 9:e894332014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Shanker J, Rao VS, Ravindran V,

Dhanalakshmi B, Hebbagodi S and Kakkar VV: Relationship of

adiponectin and leptin to coronary artery disease, classical

cardiovascular risk factors and atherothrombotic biomarkers in the

IARS cohort. Thromb Haemost. 108:769–780. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kozakova M, Palombo C, Eng MP, Dekker J,

Flyvbjerg A, Mitrakou A, Gastaldelli A and Ferrannini E: RISC

Investigators: Fatty liver index, gamma-glutamyltransferase and

early carotid plaques. Hepatology. 55:1406–1415. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|