Introduction

Mediastinitis, which is an inflammation of the chest

region between the lungs, develops mostly due to a deep wound

infection of the sternum, pneumonia, perforation of the esophagus,

or descending necrotizing mediastinitis resulting from

ear-nose-throat infections (1).

Very rarely, mediastinitis can occur from hematogenous spread, and

is usually a complication of the health care received (2).

Microorganisms frequently implicated in mediastinal

infections include anaerobes, Streptococcus species,

Corynebacterium species and members of the family

Enterobacteriaceae (3).

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) continues

to emerge as a causative agent of serious infections, mostly skin

and soft tissue infections (4,5). MRSA

is more frequently related to mediastinal infections following

cardiothoracic surgery, intravenous drug use and retropharyngeal

abscesses (3).

Few cases of MRSA mediastinitis have been described.

Herein, the rare case of MRSA mediastinitis accompanied by

pulmonary consolidation, pleural effusion and sternal osteomyelitis

following facial skin infection in, an otherwise healthy,

41-year-old man is reported.

Case report

A 41-year-old male non-smoking patient presented to

Sismanogleio Hospital with fever and anterior thoracic pain over

the previous 7 days. He had a medical history of gastroesophageal

reflux, and was not receiving any medication. The patient had no

history of diabetes mellitus, intravenous drug abuse, chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease or other comorbidities, and no

history of hospitalization and antibiotic intake in the previous 90

days.

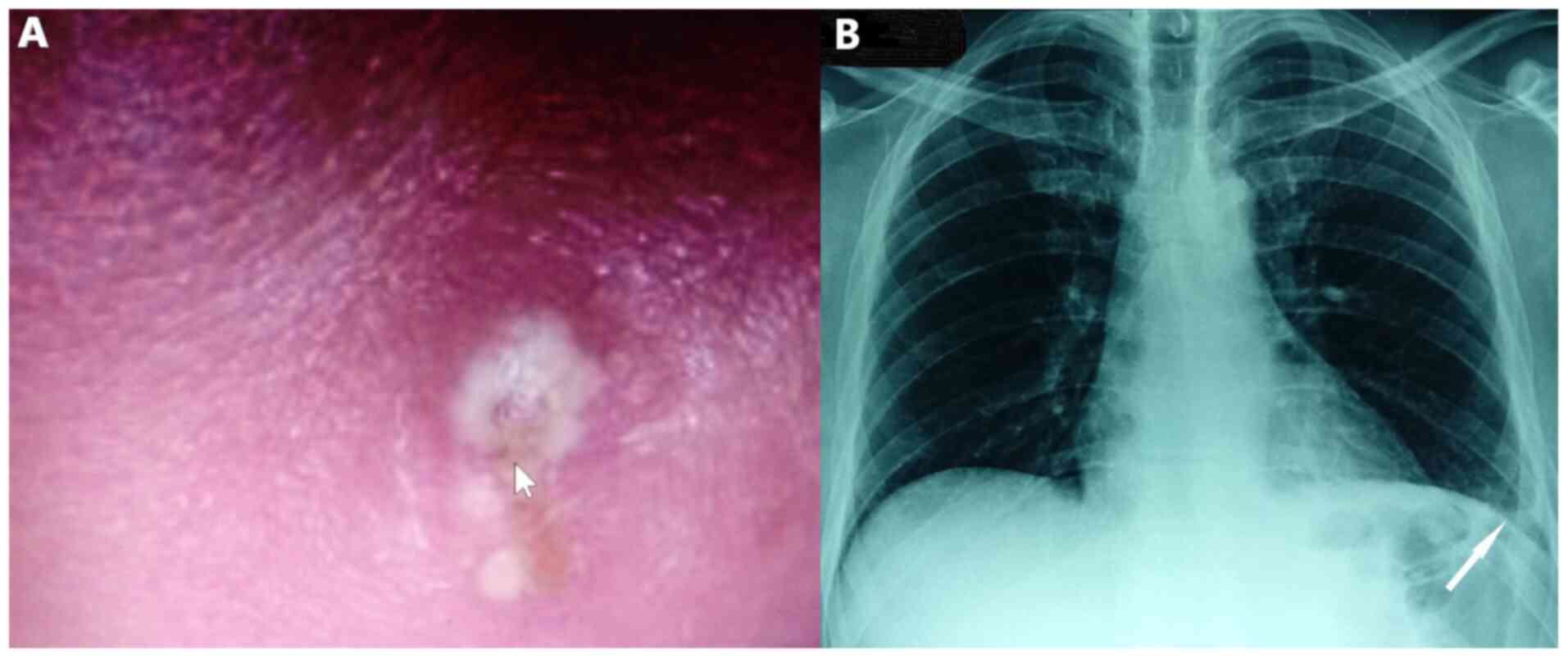

Clinical evaluation revealed a febrile patient with

dullness on percussion and crackles on auscultation at the base of

the left lung. He also had boils and carbuncles in his face, with a

pus-filled, 1 cm in greatest dimension, skin lesion on his

forehead. The skin over the infected area was red and swollen

(Fig. 1A). Physical examination of

the oropharyngeal region did not reveal abnormal findings. Clinical

examination did not also reveal neck lymph node enlargement or

obvious inflammation of neck skin and soft tissues.

Blood pressure was 150/85 mmHg, heart rate was 89

beats per minute, oxygen saturation was 96% on room air and body

temperature was 38.6˚C. Electrocardiography did not reveal abnormal

findings on admission. Chest X-ray revealed consolidation in the

left lower lobe with blunting of the left costophrenic angle

(Fig. 1B).

Laboratory investigation included complete blood

cell count, and standard biochemistry serum and urine parameters.

Laboratory findings included hemoglobin, 14.6 g/dl (normal range,

12-15 g/dl); white blood cell count, 13.37x103/µl

(normal range, 4-11x103/µl); platelet count,

167x103/µl (normal range, 150-400x103/µl);

serum glucose, 95 mg/dl (normal range, 60-100 mg/dl), C-reactive

protein (CRP), 96 mg/l (normal range, <6 mg/l) and D-dimers,

170.4 µg/l (normal range, <500 µg/l). Urinalysis and other blood

biochemistry parameters were normal.

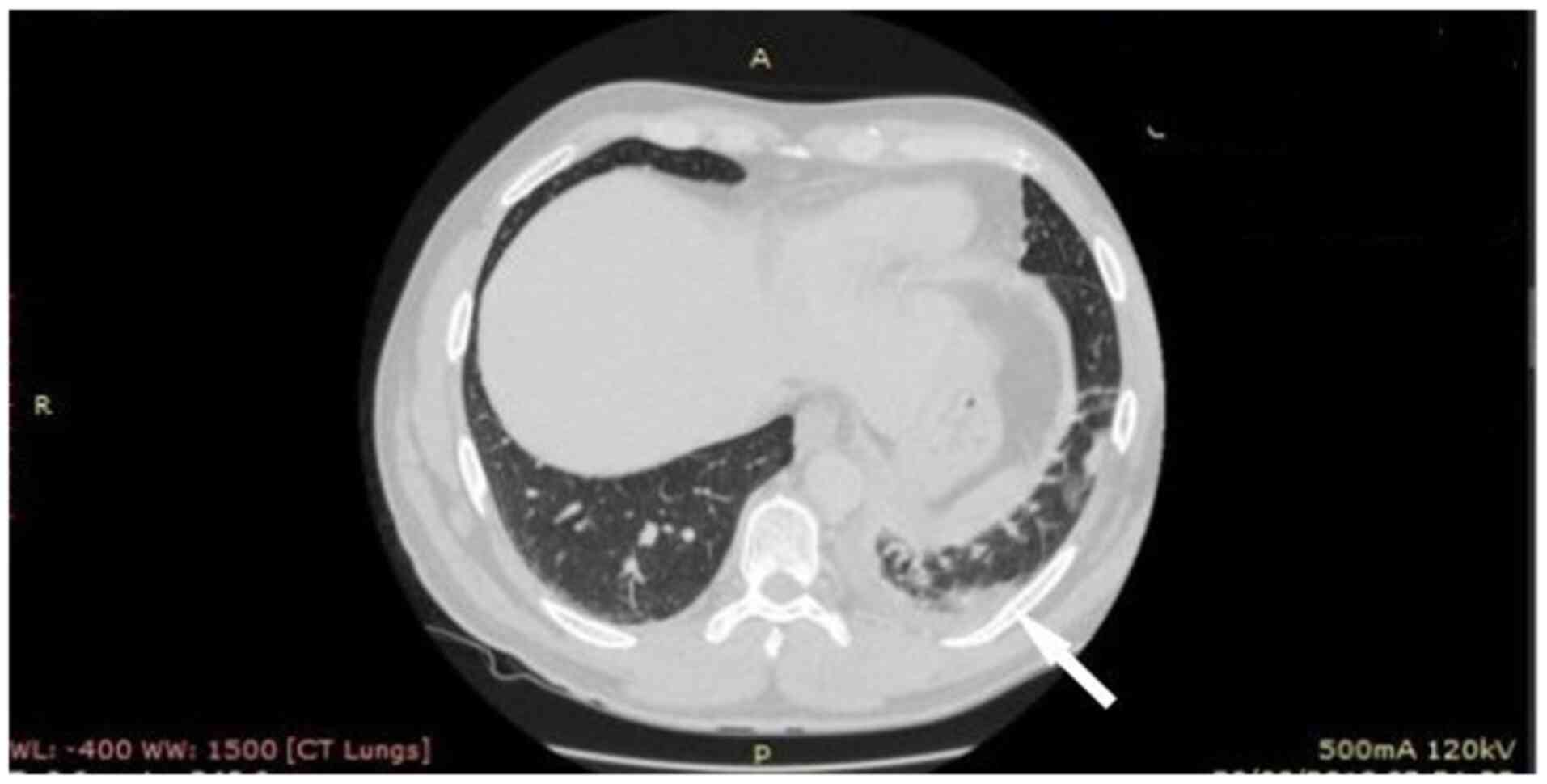

The patient underwent computed tomography (CT) of

the chest showing consolidation in the left lower lobe with left

pleural effusion, edema of the soft tissue adjacent to the first

sternocostal joint and heterogeneity, and invasion of the

retrosternal fat (Figs. 2 and

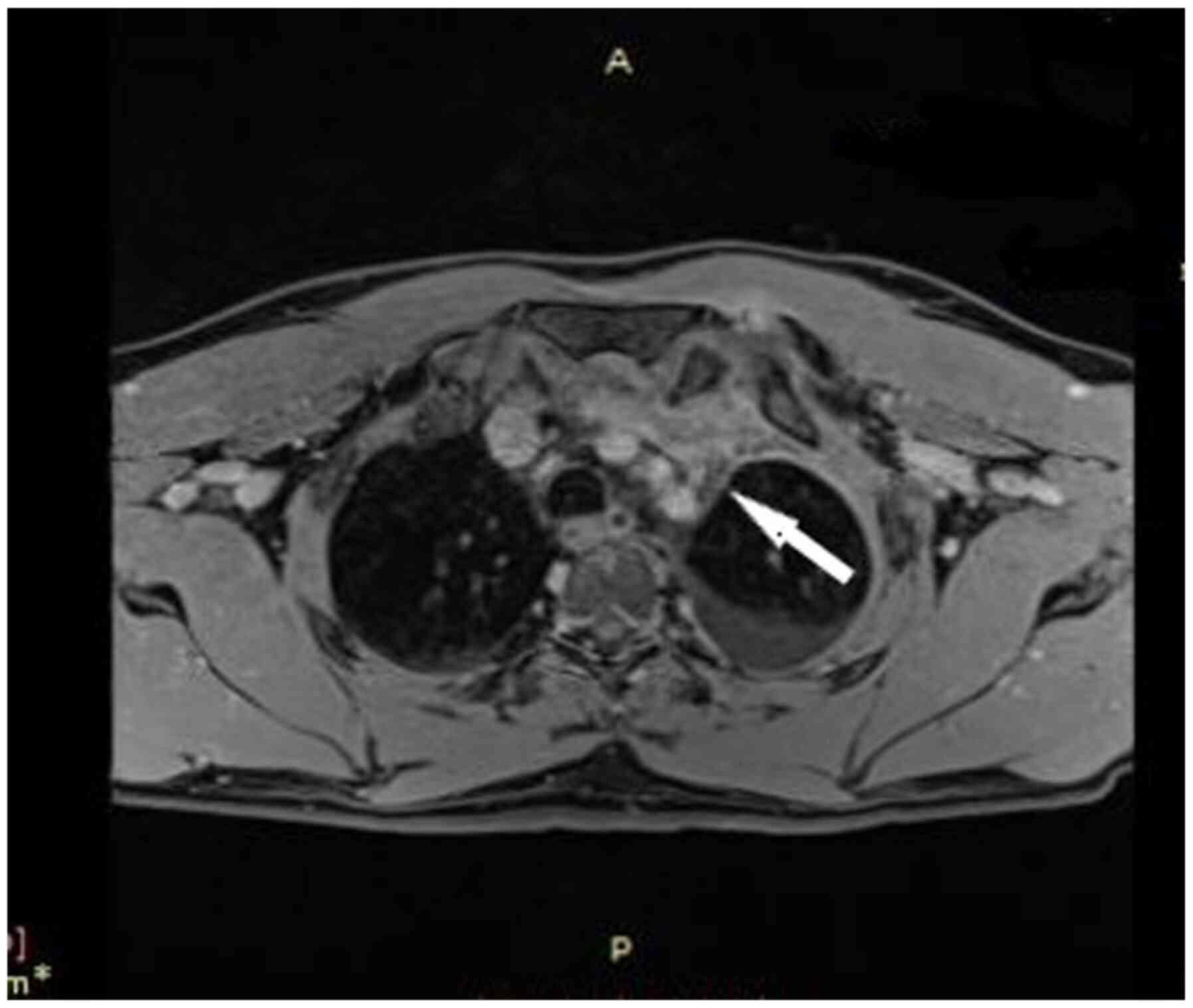

3). In addition, the patient

underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest, to obtain

detailed information regarding the pleura and mediastinum, that

revealed abnormal soft tissue with dimensions at transverse level

7.0x1.3 cm, containing cystic lesions, adjacent to the first

sternocostal joint, indicating inflammation in sternocostal

cartilage. MRI also revealed contrast enhancement of the

ipsilateral mediastinal pleura, imaging compatible with

mediastinitis (Fig. 4).

Three blood cultures and culture of the pus from the

area of facial infection were obtained before administration of

antibiotics. The pleural effusion was assessed with pleural

ultrasound and was not tapped due to its small size. The patient

was treated with intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g single daily dose)

and intravenous vancomycin (1 g twice daily) for pneumonia and skin

infection, and metronidazole (500 mg three times daily) for

anaerobic coverage regarding the suspected pleural infection

empirically. MRSA, with susceptibility to ciprofloxacin,

trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, vancomycin and linezolid, and

resistance to clindamycin, was isolated both from blood cultures

and from pus culture. MRSA was considered the causative agent for

the mediastinal and lung lesions. A CT-guided aspiration of the

cystic lesions for culture and susceptibility testing was

performed, and this culture also revealed MRSA.

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed with

normal ejection fraction and valve function. The patient was

evaluated with an immunologic workup, with no immunodeficiency

being identified. Immunoglobulin panel and T cell subpopulations

were normal. Dihydrorhodamine testing for chronic granulomatous

disease was also performed in order to exclude another rare

etiology of severe MRSA infection. Human immunodeficiency virus

testing was also negative.

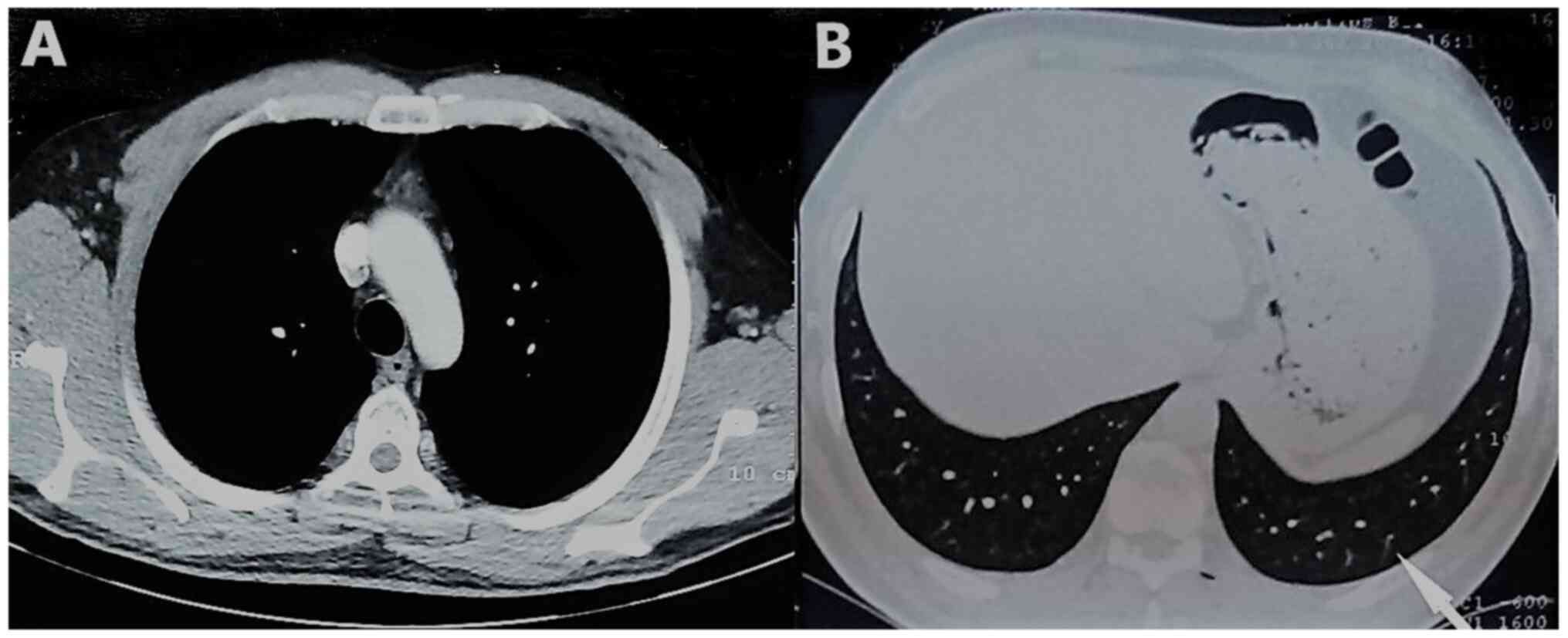

The patient presented with improvement in clinical

manifestations and blood inflammatory indices on the second day of

hospitalization, and the fever subsided on the fourth day of

hospitalization. There was no need for surgical procedure due to

the good clinical response to antibiotics. The patient received

intravenous vancomycin for 4 weeks and then there was a switch to

oral treatment with ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily for 2 weeks.

Table I shows the prescription

history and recovery flow of the patient. There was also complete

recovery observed in the imaging evaluation (Fig. 5).

| Table IPrescription history and recovery

course of the patient. |

Table I

Prescription history and recovery

course of the patient.

| Day | Recovery course |

|---|

| Days 1-4 | Administration of

intravenous Ceftriaxone, Vancomycin and Metronidazole |

| Day 2 | Improvement in

clinical manifestations and blood inflammatory indices. |

| Day 4 | Fever

subsidence. |

| Day 4 | Positive cultures

from blood, pus and cystic lesions-isolation of Methicillin

-resistant -resistant Staphylococcus aureus. |

| Day 4-28 | Administration of

intravenous Vancomycin. |

| Days 29-42 | Administration of

oral Ciprofloxacin . |

| Day 43 | Complete recovery;

inflammatory indices within normal range. |

Discussion

The present report describes the rare case of a MRSA

mediastinitis and sternal osteomyelitis infection accompanied by

pulmonary consolidation and pleural effusion following skin

infection, which was caused by a hematogenous spread in an

immunocompetent host. Risk factors for MRSA infections include

intravenous drug use, immunodeficiency, prior therapy with

antibiotics and recent hospitalization. Young age, low

socioeconomic status, and minority ethnicity have also been

identified as emerging risk factors (3).

Moreover, MRSA mediastinitis is a particularly

infrequent infection, and it has previously been known to be

associated with complications of sternotomy and retropharyngeal

abscesses (3). However, the patient

described in the present case report did not have a retropharyngeal

infection or cardiothoracic surgery, nor established

immunodeficiency.

Common findings in mediastinitis are leukocytosis

and elevations in CRP levels (6,7). In

certain cases of acute mediastinitis, high levels of CRP are

associated with a greater risk of death (6,7). In

the present case report, the patient also presented with increased

levels of CRP. This biomarker was used to detect response to

therapy, and it was within the normal range at the end of the

treatment.

Although mediastinitis, as a result of hematogenous

spread is rare, it has been described previously. Smith and

Sinzobahamvya (8) reported an

interesting case of an 11-year-old child with septic arthritis due

to Staphylococcus aureus, complicated with anterior

mediastinal abscess through hematogenous spread. Mediastinitis

usually results from a wide range of etiologies, including

esophageal perforation, lung infection, infected lymph nodes of the

neck, an infected sternotomy wound, odontogenic infection,

peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscess, trauma of the cervix,

epiglottitis, sinusitis and intravenous drug use (9). Mediastinitis as a result of

hematogenous spread was also described by Calvano et al

(3) in a case of an

immunocompromised 47-year-old female who presented with pneumonia

complicated with bacteremia and sepsis, and who developed multiple

neck and mediastinal abscesses due to Staphylococcus aureus.

Chang et al (2) reported a

case of mediastinitis in a hemodialysis patient as a complication

of Staphylococcus bacteremia, while Er et al (10) described a case of central venous

catheter-associated mediastinitis due to Candida

species.

In addition, mediastinitis as a complication of

primary skin infections is also a rare entity. Brisset et al

(1) reported a case of

Staphylococcus aureus mediastinitis in an immunocompetent

adult following back skin abscess. To the best of our knowledge,

the present case is the second report of such a case of

mediastinitis secondary to hematogenous spread following skin

infection.

Treatment of acute mediastinitis is based on

administration of antibiotics and control of the source of

inflammation with surgical debridement (11). Mediastinitis, developing as a

postoperative complication, usually requires rapid surgical

debridement. Generally, management with multiple surgical

procedures is needed in ~30% of patients. The surgical approach

depends on the extent of the disease and structures involved

(12). The usual duration of

therapy for mediastinitis is up to 4-6 weeks depending on the

extent of surgical debridement performed (13).

In conclusion, development of mediastinitis, with

hematogenous spread following skin infection, is a rare clinical

entity. With the increase of described MRSA infectious disease

cases, clinicians should remain alert for future cases of MRSA

mediastinitis and consider mediastinitis in the differential

diagnosis when a patient presents with respiratory symptoms, such

as thoracic pain and dyspnea, as well as signs of skin

infection.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

VEG, KM and DM conceptualized the study. AGk, PP,

PD, NG, NT and XT made substantial contributions to the

acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. CD and AGa

prepared the figures. All authors contributed to manuscript

revision and approved the final manuscript. PS and SC confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication.

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Brisset J, Daix T, Tricard J, Evrard B,

Vignon P, Barraud O and François B: Spontaneous community-acquired

PVL-producing Staphylococcus aureus mediastinitis in an

immunocompetent adult - a case report. BMC Infect Dis.

20(354)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Chang CH, Huang JY, Lai PC and Yang CW:

Posterior mediastinal abscess in a hemodialysis patient - a rare

but life-threatening complication of Staphylococcus bacteremia.

Clin Nephrol. 71:92–95. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Calvano TP, Ferraro DM, Prakash V, Mende K

and Hospenthal DR: Community-associated methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus mediastinitis. J Clin Microbiol.

47:3367–3369. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Gajdács M: The continuing threat of

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics

(Basel). 8(52)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Stefani S and Goglio A:

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Related

infections and antibiotic resistance. Int J Infect Dis. 14 (Suppl

4):S19–S22. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Jabłoński S, Brocki M, Krzysztof K,

Wawrzycki M, Santorek-Strumiłło E, Łobos M and Kozakiewicz M:

Evaluation of prognostic value of selected biochemical markers in

surgically treated patients with acute mediastinitis. Med Sci

Monit. 18:CR308–CR315. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Kimura A, Miyamoto S and Yamashita T:

Clinical predictors of descending necrotizing mediastinitis after

deep neck infections. Laryngoscope. 130:E567–E572. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Smith A and Sinzobahamvya N: Anterior

mediastinal abscess complicating septic arthritis. J Pediatr Surg.

27:101–102. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Lin YY, Hsu CW, Chu SJ, Chen SC and Tsai

SH: Rapidly propagating descending necrotizing mediastinitis as a

consequence of intravenous drug use. Am J Med Sci. 334:499–502.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Er F, Nia AM, Caglayan E and Gassanov N:

Mediastinitis as a complication of central venous catheterization.

Infection. 38(509)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Abu-Omar Y, Kocher GJ, Bosco P, Barbero C,

Waller D, Gudbjartsson T, Sousa-Uva M, Licht PB, Dunning J, Schmid

RA, et al: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery expert

consensus statement on the prevention and management of

mediastinitis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 51:10–29. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Prado-Calleros HM, Jiménez-Fuentes E and

Jiménez-Escobar I: Descending necrotizing mediastinitis: Systematic

review on its treatment in the last 6 years, 75 years after its

description. Head Neck. 38 (Suppl 1):E2275–E2283. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

El Oakley RM and Wright JE: Postoperative

mediastinitis: Classification and management. Ann Thorac Surg.

61:1030–1036. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|