Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the global

pandemic of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), first identified

in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, has led to unprecedented

challenges in public health, clinical management and medical

research. This coronavirus primarily targets human cells from

several tissues by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme II

(ACE2) receptor (1). The virus

predominantly spreads through respiratory droplets that are

released during activities such as coughing, sneezing or even

talking, explaining the high transmissibility and infectious nature

of the virus (2-4).

The clinical spectrum of COVID-19 is remarkably

diverse, ranging from asymptomatic or mild flu-like symptoms in

~70% of patients, to severe respiratory distress and multi-organ

failure in more critical cases (2).

Commonly reported symptoms include fever, malaise, dry cough and

sore throat. However, the pandemic has unveiled a myriad of

atypical presentations that deviate from the classical respiratory

symptoms, thereby complicating the diagnostic process (5). These atypical manifestations include,

but are not limited to, ocular symptoms, cardiac complications such

as myocarditis, dermatological signs, gastrointestinal and hepatic

disturbances, cerebrovascular incidents and various neurological

symptoms (6).

The recognition of these unusual presentations is

pivotal in ensuring timely diagnosis and appropriate management of

COVID-19. Such awareness also aids in implementing effective

isolation measures to curtail the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Among these

atypical manifestations, oral symptoms have garnered attention,

ranging from simple taste disturbances to more complex conditions

such as mucosal lesions and salivary gland infections (7).

The impact of SARS-CoV-2 on children, although

initially perceived as minor, has evolved into a subject of major

concern. In paediatric patients, the virus often manifests in forms

markedly different from adults (from asymptomatic diseases, which

represent the most common form, to multisystem inflammatory

syndrome), which can lead to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis. This

is particularly crucial as children, being active social agents in

schools and family units, can be key vectors in the transmission of

the virus. Furthermore, the emergence of multisystem inflammatory

syndrome in children associated with COVID-19 underscores the

unpredictable nature of the virus in the younger population

(8). Atypical manifestations in

children can be more cumbersome than those involving adults,

resulting in differential diagnosis and clinical management that

may pose challenges for clinicians (9).

As such, expanding our knowledge on the diverse

clinical presentations of COVID-19 in children, such as the case of

SARS-CoV-2 induced parotitis presented in the present case, is not

only pivotal for the paediatric care but also for the broader

public health strategy. This case report aims to shed light on the

less explored aspects of COVID-19 in paediatrics, illustrating how

even non-respiratory symptoms can herald the presence of the virus

in this demographic, thus necessitating a broader clinical

vigilance among healthcare providers.

The present case report contributed to this growing

body of literature by reporting SARS-CoV-2 infection presenting

primarily with unilateral parotitis and sialadenitis in a

12-year-old girl, further expanding our understanding of the

virus's clinical heterogeneity.

Case report

In November 2023, a 12-year-old female patient

visited our clinic (Polyclinic University Hospital ‘G. Rodolico’,

Catania, Italy) due to the sudden onset of right-sided unilateral

parotitis, accompanied by sialadenitis, hyperaemia of the skin and

pain upon touch. She was up-to-date on her immunizations, including

the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine. The patient had not previously

been vaccinated for SARS-CoV-2. The parents of the patient reported

no history of taking medications such as propylthiouracil,

phenothiazines, iodides or phenylbutazone. The patient had no

chronic diseases. Upon admission, her temperature was 36.3˚C, heart

rate was 78 beats per minute, blood pressure was 110/69 mmHg and

oxygen saturation in room air was 99%. The parents of the patient

reported intermittent fevers (up to 38˚C) for 3 days prior to

admission without respiratory symptoms or facial swelling. Fever

was treated with paracetamol.

Clinical examination was normal for the age and sex

of the patient. Blood tests revealed in range haemoglobin and

platelet counts. The total white count was 8,440 cells/ml, with

neutrophils at 6,380 cells/ml (75.6%) and lymphocytes at 1,588

cells/ml (18.8%). C-reactive protein levels were raised (15 mg/dl;

normal range, 0-0.5 mg/dl) as well as erythrocyte sedimentation

rate (47 mm/h; normal range, <10 mm/h), ferritin and lactate

dehydrogenase levels were within the normal range.

Mumps serology was negative for IgM and positive for

IgG. The main viral infectious disease screenings, including

serology and a respiratory panel on a pharyngeal swab

(BioFire® Respiratory 2.1 Panel; BioFire Diagnostics,

Inc.; bioMérieux), were negative. This included tests for

Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, human immunodeficiency

virus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus types 2 and

3, influenza A and B viruses, adenovirus, coxsackie viruses,

parvovirus B19, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, human bocavirus

and paramyxovirus RNA. Overall, two sets of blood cultures were

negative. A nasopharyngeal swab tested positive for SARS-CoV-2,

which was subsequently confirmed by the BioFire®

respiratory panel. A chest radiograph showed no parenchymal lung

alterations suggestive of a pneumonic process. The patient had no

upper or lower respiratory symptoms.

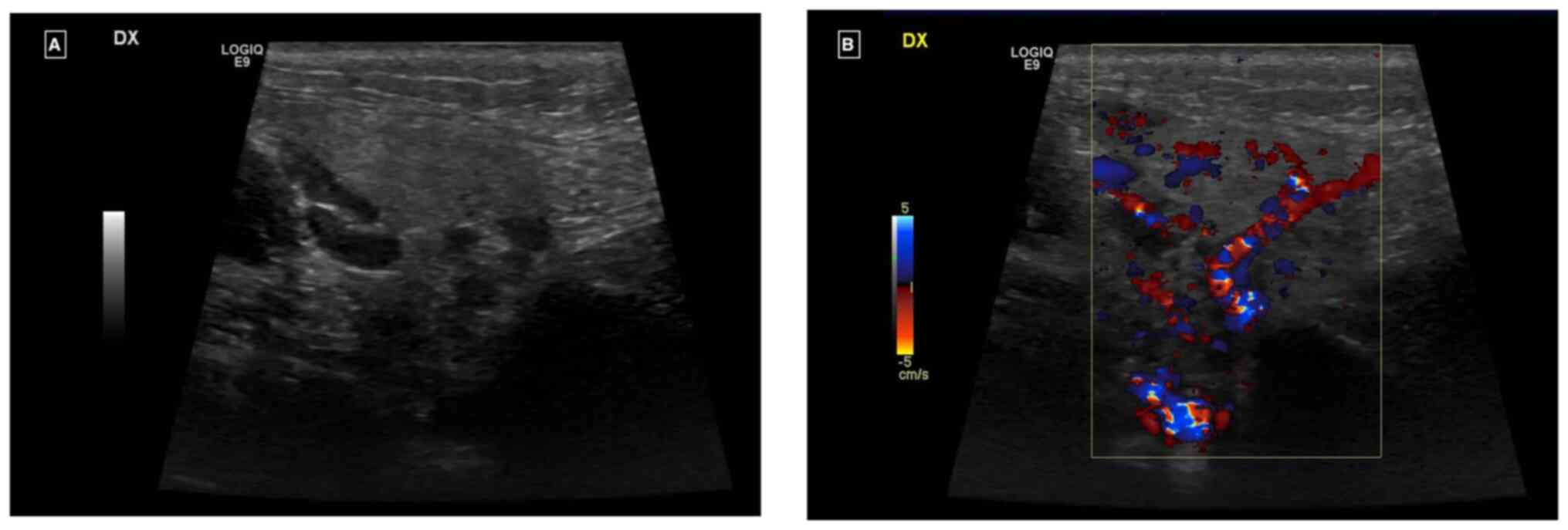

Ultrasound examination revealed an enlarged right

parotid gland and right submandibular gland, both with a

homogeneous echostructure and a diffused increase in echogenicity

of the glandular parenchyma. There was also a diffuse increase in

intraparenchymal vascularity and reactive adenitis. No fluid

collection, obstructing stones, dilatation of salivary ducts,

masses or abscesses were observed (Fig.

1A and B).

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs therapy

(NSAID) with ibuprofen was started at a dosage of 200 mg every 12

h. Although clinical symptoms did not significantly improve, within

48 h clear saliva without pus was observed to discharge from the

parotid glands. The patient was discharged with a prescription for

analgesic therapy to be used as needed. SARS-CoV-2 swab tested

negative after 7 days and the patient did not develop other

symptoms or manifestations. Parents reported they administered

ibuprofen for a total of 6 days.

At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, we noted the

complete resolution of the clinical condition of the patient.

Discussion

The present case highlights the novelty of

SARS-CoV-2-associated unilateral parotitis in a 12-year-old girl, a

rare presentation within the paediatric population. Diverging from

typical respiratory symptoms of COVID-19, this instance emphasizes

the capability of the virus to cause glandular manifestations such

as parotitis. The effective management with NSAIDs, without

preceding respiratory symptoms or common viral infections,

underscores the importance of considering COVID-19 in differential

diagnoses for acute parotitis in children, expanding our

understanding of the virus's diverse clinical manifestations.

Similar cases have emerged in the literature since

the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, predominantly in adult

populations (10-12).

The clinical spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 infection typically ranges from

minimally symptomatic disease to severe pneumonia and critical

illness, with ~70% of patients either asymptomatic or exhibiting

mild flu-like symptoms, such as fever, dry cough and sore throat

(9).

The atypical presentations of SARS-CoV-2 infection

are diverse, including myocarditis, stroke, liver damage,

gastrointestinal symptoms, ocular manifestations, dermatological

lesions and a range of neurological symptoms, observed in both mild

and severe cases (13).

The parotitis seen in SARS-CoV-2 infections can be

attributed to several interacting pathological mechanisms (11,12).

Direct viral invasion is a primary suspect, where SARS-CoV-2

infiltrates the salivary gland epithelium by binding to ACE2

receptors, causing local inflammation and cellular damage (14). Concurrently, the host's immune

response, while attempting to combat the virus, may overshoot,

releasing a deluge of cytokines in a detrimental ‘cytokine storm’,

leading to further tissue inflammation and gland swelling (15,16).

Compounding this, SARS-CoV-2 affects endothelial cells, causing

dysfunction that manifests as increased vascular permeability and

oedema, which is a condition conducive to parotitis (17). The propensity of the virus to induce

a hypercoagulable state could also precipitate microthrombi within

the tiny blood vessels of the salivary glands, impairing blood flow

and oxygen delivery, exacerbating inflammation (18). Moreover, the concept of molecular

mimicry may offer insight into prolonged or recurrent gland

inflammation, as the immune system's production of antibodies

against the virus could inadvertently target structurally similar

antigens within the salivary glands (19). This complex interplay of direct

viral effects, immune response dysregulation, vascular pathology

and autoimmune phenomena not only elucidates the occurrence of

parotitis in COVID-19 but also reflects the multisystemic impact of

SARS-CoV-2, warranting a broad spectrum of considerations in the

clinical management of these patients (2,20,21).

The timeline for the development of parotitis during

SARS-CoV-2 infection is not well-defined. In several reports,

parotitis was noted 1-3 days after the onset of coronavirus

symptoms (11,22,23).

Parotitis not related to mumps has been associated with various

viruses, including enteroviruses, adenoviruses, cytomegalovirus,

influenza, parainfluenza, Epstein-Barr, herpes simplex and herpes

virus 6(24).

In the present case, the patient presented with

acute mumps-like symptoms and unilateral sialadenitis following a

3-day history of fever, without any chronic diseases, trauma and

with normal blood tests. The positive SARS-CoV-2 swab, combined

with ultrasound findings which ruled out oncological or obstructive

conditions, along with normal blood samples and physical

examination, facilitated a non-invasive approach. This approach

allowed us to reassure the parents and monitor the patient over

time, avoiding the immediate use of more invasive imaging

techniques such as CT scans, which involve ionizing radiation.

To the best of our knowledge the scientific

literature report before the present study reports only six

patients who developed a parotitis which could be ascribed to

SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table I). The

age of the patient in the present case is somewhat aligned with the

range observed in the literature, with reported cases varying from

2 months to 7 years of age (25,26).

While most cases involved males, the present patient is female,

suggesting no strong sex predilection for SARS-CoV-2 associated

parotitis.

| Table ICharacteristics of SARS-CoV-2

associated parotitis in children. |

Table I

Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2

associated parotitis in children.

| Author | No. of patients | Age | Sex | Symptoms | Lab findings | SARS-CoV-2 test

performed | Respiratory

symptoms | Treatment | Duration (days) | Outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Brehm et

al | 1 | 10 weeks | M | Facial swelling,

decreased appetite | Leucocytosis, high

platelets | PCR | Rhinorrhoea,

cough |

Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 7 | Resolved | (27) |

| Likitnukul | 1 | 4 years | M | Facial swelling, low

grade fever, decreased appetite | High CRP, high

amylase | PCR | Mild cough | Analgesic (not

specified) | 3 | Resolved | (28) |

| Keles et

al | 1 | 4 years | M | Facial swelling and

pain, difficulty swallowing | High amylase | PCR | None | NSAID (not

specified) | 3 | Resolved | (26) |

| Sharma et

al | 3 | 7 years | F | Facial swelling,

partial maloc- clusion, trismus, decreased appetite | High CRP and ESR,

high amylase | PCR | Cough (4 weeks

before) | Prednisolone 1

mg/kg/day | 5 | Resolved | (25) |

| | | 3.5 years | M | Facial swelling,

fever, poor appetite | Leucocytosis, high

ESR and CRP | PCR | None | Prednisolone 1

mg/kg/day | 5 | Resolved | |

| | | 2 months | M | Facial swelling,

irritability, decreased appetite, fever | Leucocytosis, high

CRP | PCR | None | Metilpredni- solone

2 mg/kg/day | 5 | Resolved | |

Unlike other cases, the present patient had no

preceding respiratory symptoms, which is atypical given that

respiratory symptoms were present in most literature cases, albeit

mild in some (27), highlighting

the variable presentation of the disease. All patients had

undergone neck ultrasounds. The laboratory parameters in the

current case were mostly within normal ranges, contrasting with

other reports where leucocytosis and elevated acute-phase reactants

were common (28). This discrepancy

may point to a less aggressive inflammatory response in the present

patient.

Our patient was treated only with NSAID therapy,

without the need of either antibiotics (often overprescribed by

clinicians aiming to prevent bacterial superinfections) or

corticosteroid therapy.

The pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2-associated

sialadenitis is yet to be fully understood. However, SARS-CoV-2

should be considered in the differential diagnosis of

parotitis/sialadenitis, particularly if it presents unilaterally.

Prompt isolation measures are crucial to mitigate the spread of

infection (29).

The epidemiological landscape of COVID-19 in the

paediatric population presents a multifaceted challenge. Although

children account for a significant portion of total cases, their

clinical manifestations often differ from adults, leading to unique

considerations in public health strategies (30). Notably, the prevalence of COVID-19

among children varies with age, showing higher incidence in

school-aged children and adolescents compared with younger children

(31,32). Additionally, the impact of

socioeconomic factors is pronounced in this demographic, as

children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds face increased

exposure risks and potential health disparities (33). Understanding these dynamics is

crucial, not only for direct paediatric care but also for broader

community health policies, especially considering the role of

children in viral transmission within schools and households

(34). This complex epidemiological

profile underscores the need for tailored approaches in both

prevention and treatment strategies for COVID-19 among

children.

The present case underscores the importance of

including SARS-CoV-2, and coronaviruses in general, in the list of

pathogens responsible for parotitis and sialadenitis, alongside

mumps and influenza. Notably, a comprehensive respiratory panel and

serology are essential for accurate diagnosis in cases presenting

with parotitis-like symptoms.

Effective COVID-19 prevention in children hinges on

a multi-faceted approach that balances public health guidelines

with the unique needs of the paediatric population. Vaccination,

when available and approved for specific age groups, plays a

crucial role in reducing transmission and severity of the disease

among children (35).

In conclusion, the present case highlights the need

for heightened vigilance and a broader diagnostic perspective

during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding the diverse

clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2, including rare presentations

such as unilateral parotitis, is crucial for prompt diagnosis,

effective patient management and prevention of virus

transmission.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no

datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Authors' contributions

AM, GC, SS, MP, AB, EL, SC, EVR, GN and PP

contributed to the study conception and design. GC and AM

conceptualised the study. SS designed the methodology. MP, AB, EL

and SC performed the investigation. EVR and GN wrote the original

draft preparation. GN reviewed and edited the manuscript. PP

supervised the study. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. GN and PP confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent for data collection was

obtained from the parents of the subject involved in the study.

Patient consent for publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from

the parents of the subject involved in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Marino A, Munafò A, Augello E, Bellanca

CM, Bonomo C, Ceccarelli M, Musso N, Cantarella G, Cacopardo B and

Bernardini R: Sarilumab administration in COVID-19 patients:

Literature review and considerations. Infect Dis Rep. 14:360–371.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Zimmermann P and Curtis N: Coronavirus

infections in children including COVID-19: An overview of the

epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and

prevention options in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 39:355–368.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Mao R, Qiu Y, He JS, Tan JY, Li XH, Liang

J, Shen J, Zhu LR, Chen Y, Iacucci M, et al: Manifestations and

prognosis of gastrointestinal and liver involvement in patients

with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 5:667–678. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Cosentino F, Moscatt V, Marino A,

Pampaloni A, Scuderi D, Ceccarelli M, Benanti F, Gussio M, Larocca

L, Boscia V, et al: Clinical characteristics and predictors of

death among hospitalized patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in

Sicily, Italy: A retrospective observational study. Biomed Rep.

16(34)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Pagliari D, Marra A and Cosentini R:

Atypical manifestations of COVID-19: To know signs and symptoms to

recognize the whole disease in the emergency department. Intern

Emerg Med. 16:1407–1410. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Yang Z, Chen X, Huang R, Li S, Lin D, Yang

Z, Sun H, Liu G, Qiu J, Tang Y, et al: Atypical presentations of

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from onset to readmission. BMC

Infect Dis. 21(127)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Binmadi NO, Aljohani S, Alsharif MT,

Almazrooa SA and Sindi AM: Oral manifestations of COVID-19: A

cross-sectional study of their prevalence and association with

disease severity. J Clin Med. 11(4461)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zachariah P: COVID-19 in children. Infect

Dis Clin North Am. 36:1–14. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Kachru S and Kaul D: COVID-19

manifestations in children. Curr Med Res Pract. 10:186–188.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Friedrich RE, Droste TL, Angerer F, Popa

B, Koehnke R, Gosau M and Knipfer C: COVID-19-associated parotid

gland abscess. In Vivo. 36:1349–1353. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Maegawa K and Nishioka H:

COVID-19-associated parotitis and sublingual gland sialadenitis.

BMJ Case Rep. 15(e251730)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Brandini DA, Takamiya AS, Thakkar P,

Schaller S, Rahat R and Naqvi AR: Covid-19 and oral diseases:

Crosstalk, synergy or association? Rev Med Virol.

31(e2226)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Sayed MA and Abdelhakeem M: Typical and

atypical clinical presentation of COVID-19 infection in children in

the top of pandemic in el-minia governorate (two center

experience). Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis.

14(e2022002)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, Peng J, Dan H, Zeng

X, Li T and Chen Q: High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV

on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci.

12(8)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Montazersaheb S, Hosseiniyan Khatibi SM,

Hejazi MS, Tarhriz V, Farjami A, Ghasemian Sorbeni F, Farahzadi R

and Ghasemnejad T: COVID-19 infection: An overview on cytokine

storm and related interventions. Virol J. 19(92)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Campanella E, Marino A, Ceccarelli M,

Gussio M, Cosentino F, Moscatt V, Icali C, Nunnari G, Celesia BM

and Acopardo B: Pain crisis management in a patient with sickle

cell disease during SARS-CoV-2 infection: A case report and

literature review. World Acad Sci J. 4(14)2022.

|

|

17

|

Wu X, Xiang M, Jing H, Wang C, Novakovic

VA and Shi J: Damage to endothelial barriers and its contribution

to long COVID. Angiogenesis. 27:5–22. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Spampinato S, Pavone P, Cacciaguerra G,

Cocuzza S, Venanzi Rullo E, Marino S, Marino A and Nunnari G:

Coronavirus OC43 and influenza H3N2 concomitant unilateral

parotitis: The importance of laboratory tests in mumps-like

parotitis. Pathogens. 12(1309)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Nunez-Castilla J, Stebliankin V, Baral P,

Balbin CA, Sobhan M, Cickovski T, Mondal AM, Narasimhan G,

Chapagain P, Mathee K and Siltberg-Liberles J: Potential

autoimmunity resulting from molecular mimicry between SARS-CoV-2

spike and human proteins. Viruses. 14(1415)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Pavone P, Ceccarelli M, Taibi R, La Rocca

G and Nunnari G: Outbreak of COVID-19 infection in children: Fear

and serenity. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 24:4572–4575.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Pavone P, Marino S, Marino L, Cacciaguerra

G, Guarneri C, Nunnari G, Taibi R, Marletta L and Falsaperla R:

Chilblains-like lesions and SARS-CoV-2 in children: An overview in

therapeutic approach. Dermatol Ther. 34(e14502)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Rayan MA, Bader JA, Feras AA and Shaikha

JA: COVID-19 associated parotitis in pediatrics. Glob J Pediatr

Neonatal Care. 2:2020.

|

|

23

|

Riad A, Kassem I, Badrah M and Klugar M:

Acute parotitis as a presentation of COVID-19? Oral Dis. 28 (Suppl

1):S968–S969. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wilson M and Pandey S: Parotitis.

Emergency Management of Infectious Diseases: Second edition.

pp126-128, 2023.

|

|

25

|

Sharma S, Mahajan V and Gupta R:

Unilateral acute parotitis: A novel manifestation of pediatric

coronavirus disease. Indian Pediatr Case Rep. 2:200–203. 2022.

|

|

26

|

Ekemen Keles Y, Karadag Oncel E, Baysal M,

Kara Aksay A and Yılmaz Ciftdogan D: Acute parotitis in a

4-year-old in association with COVID-19. J Paediatr Child Health.

57:958–959. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Brehm R, Narayanam L and Chon G:

COVID-19-associated parotitis in a 10-week-old male. Cureus.

14(e31054)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Likitnukul S: COVID-19 associated

parotitis in a 4-year-old boy. J Paediatr Child Health.

58:1911–1912. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Erdem H, Hargreaves S, Ankarali H,

Caskurlu H, Ceviker SA, Bahar-Kacmaz A, Meric-Koc M, Altindis M,

Yildiz-Kirazaldi Y, Kizilates F, et al: Managing adult patients

with infectious diseases in emergency departments: International

ID-IRI study. J Chemother. 33:302–318. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ludvigsson JF: Systematic review of

COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than

adults. Acta Paediatr. 109:1088–1095. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Götzinger F, Santiago-García B,

Noguera-Julián A, Lanaspa M, Lancella L, Calò Carducci FI,

Gabrovska N, Velizarova S, Prunk P, Osterman V, et al: COVID-19 in

children and adolescents in Europe: A multinational, multicentre

cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 4:653–661.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Bialek S, Gierke R, Hughes M, McNamara LA,

Pilishvili T and Skoff T: Coronavirus disease 2019 in

children-United States, February 12-April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal

Wkly Rep. 69:422–426. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Zachariah P, Johnson CL, Halabi KC, Ahn D,

Sen AI, Fischer A, Banker SL, Giordano M, Manice CS, Diamond R, et

al: Epidemiology, clinical features, and disease severity in

patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a children's

hospital in New York City, New York. JAMA Pediatr.

174(e202430)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Parri N, Lenge M and Buonsenso D:

Coronavirus Infection in Pediatric Emergency Departments

(CONFIDENCE) Research Group. Children with Covid-19 in pediatric

emergency departments in Italy. N Engl J Med. 383:187–190.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Cag Y, Al Madadha ME, Ankarali H, Cag Y,

Demir Onder K, Seremet-Keskin A, Kizilates F, Čivljak R, Shehata G,

Alay H, et al: Vaccine hesitancy and refusal among parents: An

international ID-IRI survey. J Infect Dev Ctries. 16:1081–1088.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|