Scaffold attachment factor A (SAF-A), or

heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein U (hnRNP U), belonging to the hnRNP

subfamily, is an abundant component of nuclear matrix and hnRNP

particles (1).

Since human SAF-A (Uniprot code: Q00839) contains

825 amino acids, its predicted molecular weight is ~90 kDa. But,

due to modifications such as phosphorylation, SAF-A is usually

observed to be ~120 kDa. SAF-A is widely expressed in various

organs or tissues, such as bone marrow, lymphoid tissues, brain,

heart, lung and kidney (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000153187-HNRNPU).

Due to its functional domains, SAF-A binds to both DNA (such as

scaffold-attached region DNA) and RNA (such as chromatin-associated

RNAs) and plays essential roles in several cellular processes such

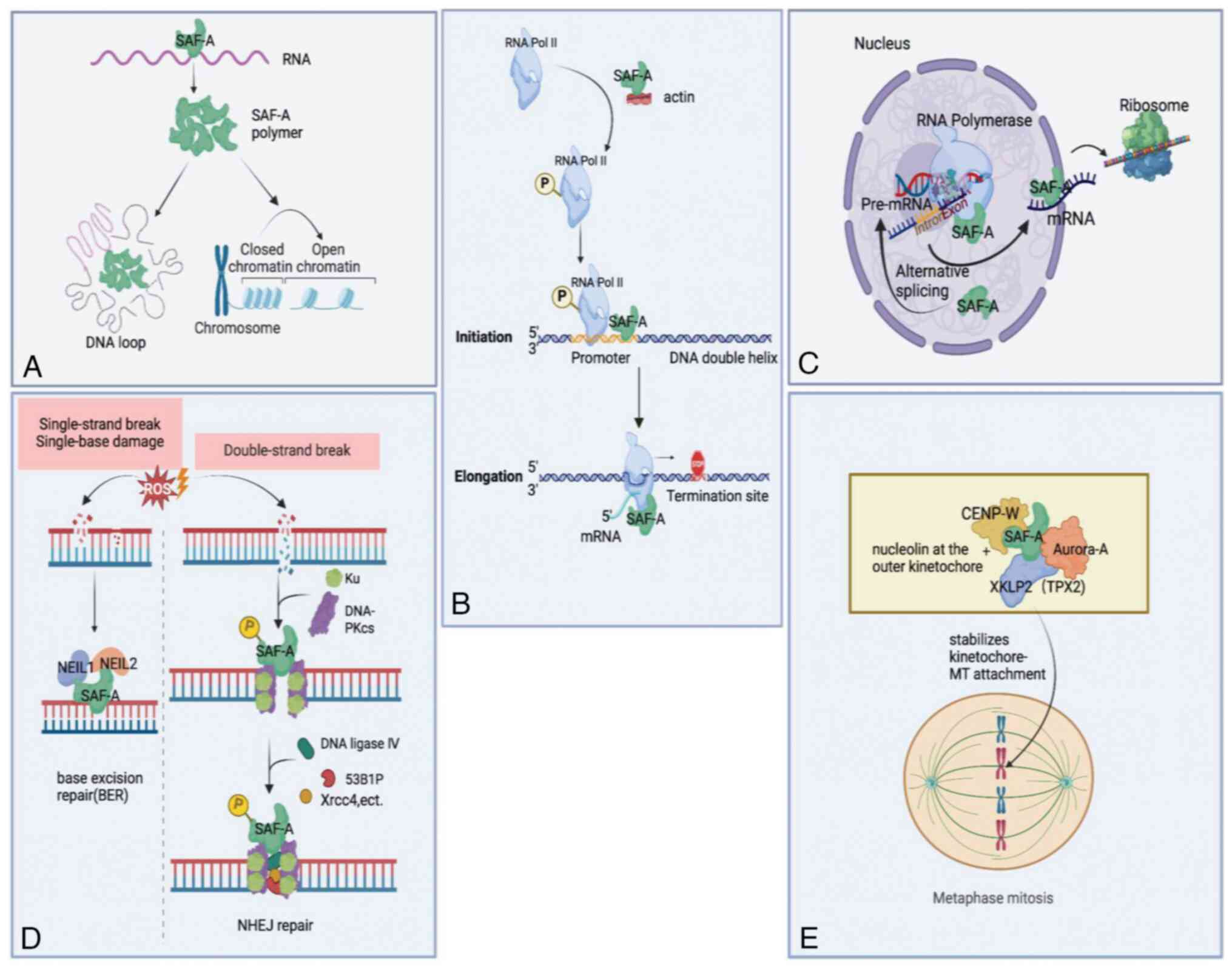

as chromatin structure regulation (3), transcription (4) and mitosis (5). The present review summarized the

structure, multiple functions and clinical significance of

SAF-A.

SAF-A contains three domains: N-terminal

DNA-binding, C-terminal RNA binding and middle domain (6-8)

(Fig. 1). Notably, the DNA-binding

domain SAF/Acinus/PIAS (SAP) is important for interaction with

matrix association region (MAR) in chromatin (6). Containing a cluster of

arginine/glycine-rich (RGG) repeats, the C-terminus of SAF-A is

necessary for binding to inactive X chromosome regions and

chromatin-associated RNAs (8). The

middle domain of SAF-A, including an SPla and RYanodine receptor

and a nucleotide triphosphate hydrolase region (9,10),

mediates its interaction with different proteins, such as forkhead

box N3(11), Wilms' tumor

suppressor gene 1(9) and severe

fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus nucleocapsid protein

(12).

In the eukaryotic cell nucleus, chromatin forms 3-D

structures at multiple levels, including domains, loops, A and B

compartments (relating to active and inactive chromatin,

respectively), topologically associating domains (TADs) and

territories (13-16).

Further studies demonstrated that SAF-A regulates

chromatin structure via RNA. Jiao et al (19) found that SAF-A binds to histone

acetyltransferases p300 in cancer cells (19). Facilitated by heparanase (HPSE)

enhancer RNA, the SAF-A-p300 complex is enriched on the

super-enhancer, consequently leading to chromatin looping between

the HPSE promoter and the super-enhancer. Consistently

interacting with chromatin-associated RNAs, SAF-A forms

oligomerization that induces de-compaction of large-scale human

interphase chromatin structure (8)

(Fig. 2A). In this way, SAF-A

maintains genomic stability (8).

When human monocyte THP-1 cells are infected by vesicular

stomatitis virus (VSV), SAF-A interacts with viral

infection-induced RNAs, mediating the openness and activation of

antiviral immune genes (20).

Puvvula and Moon (10) treated

cancer cells with cell-penetrating peptides derived from SAF-A, and

found that the SAP-derived peptide rather than the RGG-derived one

promotes chromatin compaction in HCT116 (colorectal), T47D (breast)

and UMUC3 (bladder) cancer cells. Based on these observations, RNA

is proposed to be essential for SAF-A-induced chromatin

de-compaction.

Besides RNA, DNA was also reported to be necessary

for SAF-A to regulate chromatin structure. In the study of Kolpa

et al (21), similar to the

C280 SAF-A deletion mutant (only containing RGG domain), the

expression of ∆RGG (containing DNA-binding domain) and G29A mutants

(in lack of DNA-binding ability) was able to release C0T-1 RNA from

chromatin, resulting in chromatin condensation. Despite this, their

regulatory mechanism is different. ∆RGG SAF-A mutant mainly

replaced endogenous SAF-A from chromatin, while the G29A mutant

still combined with C0T-1 RNA and could not bind to chromatin

(21). Therefore, to some degree,

SAF-A may play a role in bridging C0T-1 RNA and chromatin to

regulate chromatin architecture. Depending on the SAP domain, SAF-A

was also found to combine with MARs and the pericentromere tandem

repeats in chromocenters (6,22).

Therefore, it was hypothesized that SAF-A tethers MARs to the

chromocenter to organize nuclear architecture (1).

In eukaryotic cells, transcription of protein-coding

genes, including initiation, elongation and termination phases,

contains numerous regulatory proteins affecting either the RNA

polymerase II (Pol II) machinery or chromatin structure (23-26).

Previous studies have indicated that SAF-A is

involved in initial transcriptional regulation. Actin in the

nucleus regulates transcription by remodeling chromatin, regulating

transcription factor (TF) location, or binding to RNA polymerase

(27-30).

Through extracellular vesicles derived from embryonic stem cells,

SAF-A is transferred into human coronary artery endothelial cells

to combine with actin. The SAF-A-actin complex leads to enhanced

RNA Pol II phosphorylation and its level on vascular endothelial

growth factor (VEGF) promoter, upregulating VEGF expression

(4) (Fig. 2B). When the SAF-A-actin complex is

disrupted by H19 [a long non-coding (lnc) RNA], the phosphorylation

of the Pol II C-terminal domain (CTD) is inhibited, and

consequently, Pol II-mediated transcription is prohibited (31). Additionally, SAF-A was found to

associate with elements within the promoter regions. In Sertoli

cells, SAF-A has been identified to bind directly to the promoter

regions of Sox8 and Sox9, thereby enhancing their

expression (32) (Fig. 2B). Similarly, IL21-anti-sense RNA 1

interacting with SAF-A binds to the IL21 promoter, which is

essential for regulating IL21 transcription (33). Research on embryonic stem cells also

revealed that not only does SAF-A bind to the Oct4 proximal

promoter, but it also interacts with endogenous Pol II. And

depletion of SAF-A impairs Oct4 expression (34).

In previous studies, SAF-A appeared to have two-way

adjusting effects on transcription elongation mediated by Pol II.

According to the study of Obrdlik et al (35), SAF-A, actin and p300/CBP-associated

factor (PCAF) were associated with the phosphorylated Pol II CTD;

and the actin-SAF-A interaction assisted Pol II transcription

elongation depending on PCAF (Fig.

2B). On the contrary, in another study, SAF-A inhibited Pol II

elongation. Through the middle domain, SAF-A was sufficient to

combine with Pol II and repressed TF IIH-mediated Pol II CTD

phosphorylation, which inhibited Pol II elongation (36) (Fig.

2B).

SAF-A has also been implicated in various aspects of

RNA metabolism, including normal and alternative pre-mRNA splicing

and RNA transporting (Fig. 2C).

It has been identified that SAF-A is responsible for

transporting and stabilizing mRNA via directly binding to it. Zhao

et al (41) found that SAF-A

binds to tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-6 and

IL-1β mRNAs and that downregulation of SAF-A expression in

macrophages induces the decreased half-life of these cytokine

mRNAs. Besides, Toll-like receptor signaling in macrophages leads

to SAF-A translocation from nuclear to cytoplasm (41). During this translocation, SAF-A is

proposed to stabilize pro-inflammatory cytokine mRNAs (41). In agreement with the aforementioned

study, SAF-A was found to bind to the 3' untranslated region of

TNF α mRNA to stabilize it and specifically enhance TNF α

expression (42). However, other

studies suggested that SAF-A stabilizes mRNA depending on other

molecules. Pan et al (43)

found that interaction between LIM domains-containing 1 antisense

RNA 1 (LIMD1-AS1) and SAF-A is essential for stabilizing

LIMD1 mRNA in non-small cell lung cancer. Furthermore, Lu

et al (44) reported that

following lipopolysaccharide stimulation in human intestinal

epithelial cells, functional intergenic repeating RNA element

cooperating with SAF-A may regulate the stabilization of vascular

cell adhesion protein 1 and IL12p40 mRNAs through targeting

the AU-rich elements of these mRNAs.

In cells, ionizing radiation (IR) and reactive

oxygen species may result in clustered oxidized bases and DSBs that

are also induced by V(D)J recombination (45-47).

Oxidized base lesions in the human genome are repaired via DNA

glycosylase (DG) repair, also known as base excision repair (BER).

Repair enzymes, including Nei endonuclease VIII-like (NEIL) and

certain non-repair proteins, such as SAF-A, initiate this process

(48,49). In previous studies, SAF-A was

demonstrated to interact directly with NEIL1 and stimulate

NEIL1-mediated repair of oxidative base damage (48,49).

In addition to NEIL1, SAF-A combines with NEIL2, enhancing

NEIL2-initiated transcribed gene-specific repair of oxidized bases

(50) (Fig. 2D).

However, BER of bi-stranded oxidized bases can lead

to additional DSBs, causing loss of DNA fragments. This may be

avoided if DSBs are repaired through non-homologous end joining

(NHEJ) mediated by Ku, DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic

subunit (DNA-PKcs), X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 4

(XRCC4), DNA ligase IV, and cernunnos-XRCC4-like factor complex,

preceding BER (51-53).

In response to irradiation-induced DSBs, SAF-A is rapidly recruited

to DNA damage sites (54) (Fig. 2D). Besides, DSBs cause

phosphorylated SAF-A at Ser59, which is exclusively dependent on

DNA-PK (55,56) (Fig.

2D). In NHEJ-deficient cells treated with IR or clastogenic

drugs, the extent and duration of SAF-A phosphorylation at Ser59

increase (56), which suggests that

phosphorylated SAF-A may be a biomarker for testing the capacity of

the cells to repair DSBs by NHEJ. A previous study showed that

SAF-A phosphorylation at Ser59 is related to transient NEIL1

release from chromatin and BER prevention. Then, due to

dephosphorylation, SAF-A reactivates BER by relieving DG inhibition

(57). These results suggested that

DSB repair by NHEJ or BER is partly determined by whether SAF-A is

phosphorylated. However, a recent study found that increased SAF-A

stabilizes or recruits NHEJ factors via liquid-liquid phase

separation, including Ku80, 53BP1, DNA-PKcs and the shieldin

complex at DSBs during antibody class-switch recombination

(58) (Fig. 2D). The finding supplies SAF-A may

balance between BER and NHEL through complex mechanisms.

During mitosis, kinetochore-microtubule (MT)

attachment and chromosome congression at the spindle equator is

essential to accurate chromosome segregation (59,60).

Interestingly, SAF-A binds to not only Aurora-A and targeting

protein for Xklp2 (TPX2) at spindle MTs, but also nucleolin at the

outer kinetochore, whereby SAF-A stabilizes kinetochore-MT

attachment (61) (Fig. 2E). Via non-coding RNA, SAF-A

interacts with centromere protein W (CENP-W, an inner centromere

component crucial for forming a functional kinetochore complex).

Notably, SAF-A-CENP-W interaction increases their stability, and

they co-localize at the MT-kinetochore interface during mitosis

(62) (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, SAF-A depletion in

cells leads to delayed mitosis, unsuccessful chromosome alignment,

and spindle assembly (61).

In addition, SAF-A is dynamically phosphorylated

during mitosis, and in human cells, phosphorylation at serine 2

(S2), S3, S4, S59, S66 and S270 is related to mitosis (63-65).

Douglas et al (66) found

SAF-A is phosphorylated at S59 by polo-like kinase 1 instead of

DNA-PK and is dephosphorylated by protein phosphatase 2A. Mutations

of SAF-A S59 in cells lead to aberrant mitoses, including polylobed

nuclei, delayed passage, misaligned and lagging chromosomes

(66). However, the regulatory

mechanism of phosphorylated SAF-A on mitosis remains elusive.

Further studies have demonstrated a correlation

between SAF-A and resistance to chemotherapy. Shi et al

(76) discovered that the knockout

of SAF-A in human T24 cells enhances bladder cancer susceptibility

to cisplatin via inhibition of cell proliferation and impairment of

cellular invasion and migration capabilities. In the research of

Wang et al (77), the

knockdown of SAF-A increases selinexor sensitivities of multiple

myeloma (MM) cells in vitro and in mouse models and MM

patients with relatively low SAF-A expression response to

selinexor.

However, a few studies demonstrated that SAF-A might

suppress tumor cell proliferation and enhance sensitivities to

chemotherapy. Pan et al (43) reported that LIMD1 inhibits

proliferation and promotes apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer

cells, and SAF-A interacts with lncRNA LIMD1-AS1 to

stabilize LIMD1 mRNA. Puvvula and Moon (10) dealt with various tumor cells with

SAF-A RGG- or SAP-derived peptides. Depending on different

mechanisms, these peptides suppress breast, bladder, colorectal and

prostate cancer cell proliferation. The SAF-A RGG-derived peptides

mainly alter SAF-A splicing and binding targets, while the

SAP-derived regulates global epigenetic marks to induce DNA damage

reaction and cell death (10). Li

et al (78) also identified

that lncRNA SFTA1 could augment cisplatin sensitivity in

treating lung squamous cell carcinoma by upregulating SAF-A.

The contradictory effects of SAF-A on tumors may

result from different tumor types or test methods. Therefore, more

animal and clinical experiments are needed to identify its

functions further.

Previous research revealed that SAF-A plays dual

roles in antiviral response. Through the N-terminal fragment

(aa1-86), SAF-A targets the 3' long terminal repeat of human

immunodeficiency virus type 1 mRNA and blocks viral replication in

cells (79). Furtherly, in both

in vitro and in vivo animal experiments, SAF-A has

been reported to be associated with the initiation of innate

immunity against viruses, including severe fever with

thrombocytopenia syndrome virus, VSV, and herpes simplex virus type

1 by recognizing nuclear or cytoplasmic viral RNA (12,20,80).

Therefore, the diverse roles of SAF-A played in

these experiments may be due to different viruses or hosts, and

more animal experiments are needed to determine the roles of SAF-A

in antiviral immunity.

SAF-A is one of the main components of the nuclear

matrix. Capable of binding both DNA and RNA, SAF-A has crucial

functions in regulating chromatin architecture, transcription, RNA

metabolism, DNA repair and mitosis. Humans or mice with SAF-A

deficiency or mutants display embryonic death (91), lethal cardiomyopathy (37) and neurodevelopmental disorders

(38,90). Therefore, SAF-A may be a valuable

prediction factor or therapeutic target. Besides, SAF-A has been

observed to be related to anti-infection and tumor progression,

though these functions are controversial. Because of this, more

animal experiments and clinical assays are needed.

Not applicable.

Funding: The present study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81801551) and the Central

Government Funds of Guiding Local Scientific and Technological

Development for Sichuan (grant no. 2021ZYD0076).

Not applicable.

XC, ML and DZ contributed to the conception of the

study. DZ and LL performed the literature research and wrote the

manuscript. XC and ML revised the manuscript. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Podgornaya OI: Nuclear organization by

satellite DNA, SAF-A/hnRNPU and matrix attachment regions. Semin

Cell Dev Biol. 128:61–68. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Fackelmayer FO and Richter A:

hnRNP-U/SAF-A is encoded by two differentially polyadenylated mRNAs

in human cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1217:232–234. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Wavelet-Vermuse C, Odnokoz O, Xue Y, Lu X,

Cristofanilli M and Wan Y: CDC20-Mediated hnRNPU ubiquitination

regulates chromatin condensation and anti-cancer drug response.

Cancers (Basel). 14(3732)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Wang H, Liu H, Zhao X and Chen X:

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U-actin complex derived

from extracellular vesicles facilitates proliferation and migration

of human coronary artery endothelial cells by promoting RNA

polymerase II transcription. Bioengineered. 13:11469–11486.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Sharp JA, Perea-Resa C, Wang W and Blower

MD: Cell division requires RNA eviction from condensing

chromosomes. J Cell Biol. 219(e201910148)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kipp M, Gohring F, Ostendorp T, van Drunen

CM, van Driel R, Przybylski M and Fackelmayer FO: SAF-Box, a

conserved protein domain that specifically recognizes scaffold

attachment region DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 20:7480–7489. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Helbig R and Fackelmayer FO: Scaffold

attachment factor A (SAF-A) is concentrated in inactive X

chromosome territories through its RGG domain. Chromosoma.

112:173–182. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Nozawa RS, Boteva L, Soares DC, Naughton

C, Dun AR, Buckle A, Ramsahoye B, Bruton PC, Saleeb RS, Arnedo M,

et al: SAF-A Regulates Interphase Chromosome Structure through

Oligomerization with Chromatin-Associated RNAs. Cell. 169:1214–1227

e18. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Spraggon L, Dudnakova T, Slight J,

Lustig-Yariv O, Cotterell J, Hastie H and Miles C: hnRNP-U directly

interacts with WT1 and modulates WT1 transcriptional activation.

Oncogene. 26:1484–1491. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Puvvula PK and Moon AM: Novel

cell-penetrating peptides derived from scaffold-attachment-factor a

inhibits cancer cell proliferation and survival. Front Oncol.

11(621825)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zhu X, Huang B, Zhao F, Lian J, He L,

Zhang Y, Ji L, Zhang J, Yan X, Zeng T, et al: p38-mediated FOXN3

phosphorylation modulates lung inflammation and injury through the

NF-κB signaling pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 51:2195–2214.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Liu BY, Yu XJ and Zhou CM: SAFA initiates

innate immunity against cytoplasmic RNA virus SFTSV infection. PLoS

Pathog. 17(e1010070)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ghirlando R and Felsenfeld G: CTCF: Making

the right connections. Genes Dev. 30:881–891. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Fritz AJ, Sehgal N, Pliss A, Xu J and

Berezney R: Chromosome territories and the global regulation of the

genome. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 58:407–426. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wang W, Chandra A, Goldman N, Yoon S,

Ferrari EK, Nguyen SC, Joyce EF and Vahedi G: TCF-1 promotes

chromatin interactions across topologically associating domains in

T cell progenitors. Nat Immunol. 23:1052–1062. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Krasikova A, Kulikova T, Rodriguez Ramos

JS and Maslova A: Assignment of the somatic A/B compartments to

chromatin domains in giant transcriptionally active lampbrush

chromosomes. Epigenetics Chromatin. 16(24)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Romig H, Fackelmayer FO, Renz A,

Ramsperger U and Richter A: Characterization of SAF-A, a novel

nuclear DNA binding protein from HeLa cells with high affinity for

nuclear matrix/scaffold attachment DNA elements. EMBO J.

11:3431–3440. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Fan H, Lv P, Huo X, Wu J, Wang Q, Cheng L,

Liu Y, Tang QQ, Zhang L, Zhang F, et al: The nuclear matrix protein

HNRNPU maintains 3D genome architecture globally in mouse

hepatocytes. Genome Res. 28:192–202. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Jiao W, Chen Y, Song H, Li D, Mei H, Yang

F, Fang E, Wang X, Huang K, Zheng L and Tong Q: HPSE enhancer RNA

promotes cancer progression through driving chromatin looping and

regulating hnRNPU/p300/EGR1/HPSE axis. Oncogene. 37:2728–2745.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Cao L, Luo Y, Guo X, Liu S, Li S, Li J,

Zhang Z, Zhao Y, Zhang Q, Gao F, et al: SAFA facilitates chromatin

opening of immune genes through interacting with anti-viral host

RNAs. PLoS Pathog. 18(e1010599)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Kolpa HJ, Creamer KM, Hall LL and Lawrence

JB: SAF-A mutants disrupt chromatin structure through dominant

negative effects on RNAs associated with chromatin. Mamm Genome.

33:366–381. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Lobov IB, Tsutsui K, Mitchell AR and

Podgornaya OI: Specificity of SAF-A and lamin B binding in vitro

correlates with the satellite DNA bending state. J Cell Biochem.

83:218–229. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Cramer P: Organization and regulation of

gene transcription. Nature. 573:45–54. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Altendorfer E, Mochalova Y and Mayer A:

BRD4: A general regulator of transcription elongation.

Transcription. 13:70–81. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Haberle V and Stark A: Eukaryotic core

promoters and the functional basis of transcription initiation. Nat

Rev Mol Cell Biol. 19:621–637. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Gibbons MD, Fang Y, Spicola AP, Linzer N,

Jones SM, Johnson BR, Li L, Xie M and Bungert J: Enhancer-mediated

formation of nuclear transcription initiation domains. Int J Mol

Sci. 23(9290)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Sokolova M, Moore HM, Prajapati B, Dopie

J, Merilainen L, Honkanen M, Matos RC, Poukkula M, Hietakangas V

and Vartiainen MK: Nuclear actin is required for transcription

during drosophila oogenesis. iScience. 9:63–70. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Knoll KR, Eustermann S, Niebauer V,

Oberbeckmann E, Stoehr G, Schall K, Tosi A, Schwarz M, Buchfellner

A, Korber P and Hopfner KP: The nuclear actin-containing Arp8

module is a linker DNA sensor driving INO80 chromatin remodeling.

Nat Struct Mol Biol. 25:823–832. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Almuzzaini B, Sarshad AA, Rahmanto AS,

Hansson ML, Von Euler A, Sangfelt O, Visa N, Farrants AK and

Percipalle P: In β-actin knockouts, epigenetic reprogramming and

rDNA transcription inactivation lead to growth and proliferation

defects. FASEB J. 30:2860–2873. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Al-Sayegh MA, Mahmood SR, Khair SBA, Xie

X, El Gindi M, Kim T, Almansoori A and Percipalle P: beta-actin

contributes to open chromatin for activation of the adipogenic

pioneer factor CEBPA during transcriptional reprograming. Mol Biol

Cell. 31:2511–2521. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Bi HS, Yang XY, Yuan JH, Yang F, Xu D, Guo

YJ, Zhang L, Zhou CC, Wang F and Sun SH: H19 inhibits RNA

polymerase II-mediated transcription by disrupting the hnRNP

U-actin complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1830:4899–4906.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wen Y, Ma X, Wang X, Wang F, Dong J, Wu Y,

Lv C, Liu K, Zhang Y, Zhang Z and Yuan S: hnRNPU in Sertoli cells

cooperates with WT1 and is essential for testicular development by

modulating transcriptional factors Sox8/9. Theranostics.

11:10030–10046. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Liu L, Hu L, Long H, Zheng M, Hu Z, He Y,

Gao X, Du P, Zhao H, Yu D, et al: LncRNA IL21-AS1 interacts with

hnRNPU protein to promote IL21 overexpression and aberrant

differentiation of Tfh cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin

Transl Med. 12(e1117)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Vizlin-Hodzic D, Johansson H, Ryme J,

Simonsson T and Simonsson S: SAF-A has a role in transcriptional

regulation of Oct4 in ES cells through promoter binding. Cell

Reprogram. 13:13–27. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Obrdlik A, Kukalev A, Louvet E, Farrants

AK, Caputo L and Percipalle P: The histone acetyltransferase PCAF

associates with actin and hnRNP U for RNA polymerase II

transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 28:6342–6357. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kim MK and Nikodem VM: hnRNP U inhibits

carboxy-terminal domain phosphorylation by TFIIH and represses RNA

polymerase II elongation. Mol Cell Biol. 19:6833–6844.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Ye J, Beetz N, O'Keeffe S, Tapia JC,

Macpherson L, Chen WV, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN and Maniatis T:

hnRNP U protein is required for normal pre-mRNA splicing and

postnatal heart development and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

112:E3020–E3029. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Sapir T, Kshirsagar A, Gorelik A, Olender

T, Porat Z, Scheffer IE, Goldstein DB, Devinsky O and Reiner O:

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U (HNRNPU) safeguards the

developing mouse cortex. Nat Commun. 13(4209)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Xiao R, Tang P, Yang B, Huang J, Zhou Y,

Shao C, Li H, Sun H, Zhang Y and Fu XD: Nuclear matrix factor hnRNP

U/SAF-A exerts a global control of alternative splicing by

regulating U2 snRNP maturation. Mol Cell. 45:656–668.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Vu NT, Park MA, Shultz JC, Goehe RW,

Hoeferlin LA, Shultz MD, Smith SA, Lynch KW and Chalfant CE: hnRNP

U enhances caspase-9 splicing and is modulated by AKT-dependent

phosphorylation of hnRNP L. J Biol Chem. 288:8575–8584.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zhao W, Wang L, Zhang M, Wang P, Qi J,

Zhang L and Gao C: Nuclear to cytoplasmic translocation of

heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U enhances TLR-induced

proinflammatory cytokine production by stabilizing mRNAs in

macrophages. J Immunol. 188:3179–3187. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Yugami M, Kabe Y, Yamaguchi Y, Wada T and

Handa H: hnRNP-U enhances the expression of specific genes by

stabilizing mRNA. FEBS Lett. 581:1–7. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Pan J, Tang Y, Liu S, Li L, Yu B, Lu Y and

Wang Y: LIMD1-AS1 suppressed non-small cell lung cancer progression

through stabilizing LIMD1 mRNA via hnRNP U. Cancer Med.

9:3829–3839. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Lu Y, Liu X, Xie M, Liu M, Ye M, Li M,

Chen XM, Li X and Zhou R: The NF-κB-Responsive Long Noncoding RNA

FIRRE Regulates Posttranscriptional Regulation of Inflammatory Gene

Expression through Interacting with hnRNPU. J Immunol.

199:3571–3582. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Bredemeyer AL, Helmink BA, Innes CL,

Calderon B, McGinnis LM, Mahowald GK, Gapud EJ, Walker LM, Collins

JB, Weaver BK, et al: DNA double-strand breaks activate a

multi-functional genetic program in developing lymphocytes. Nature.

456:819–823. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Cannan WJ, Tsang BP, Wallace SS and

Pederson DS: Nucleosomes suppress the formation of double-strand

DNA breaks during attempted base excision repair of clustered

oxidative damages. J Biol Chem. 289:19881–19893. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Nickoloff JA, Sharma N and Taylor L:

Clustered DNA Double-Strand Breaks: Biological effects and

relevance to cancer radiotherapy. Genes (Basel).

11(99)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Hegde ML, Banerjee S, Hegde PM, Bellot LJ,

Hazra TK, Boldogh I and Mitra S: Enhancement of NEIL1

protein-initiated oxidized DNA base excision repair by

heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U (hnRNP-U) via direct

interaction. J Biol Chem. 287:34202–34211. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Dutta A, Yang C, Sengupta S, Mitra S and

Hegde ML: New paradigms in the repair of oxidative damage in human

genome: Mechanisms ensuring repair of mutagenic base lesions during

replication and involvement of accessory proteins. Cell Mol Life

Sci. 72:1679–1698. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Banerjee D, Mandal SM, Das A, Hegde ML,

Das S, Bhakat KK, Boldogh I, Sarkar PS, Mitra S and Hazra TK:

Preferential repair of oxidized base damage in the transcribed

genes of mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 286:6006–6016.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Hammel M, Yu Y, Radhakrishnan SK, Chokshi

C, Tsai MS, Matsumoto Y, Kuzdovich M, Remesh SG, Fang S, Tomkinson

AE, et al: An Intrinsically Disordered APLF Links Ku, DNA-PKcs, and

XRCC4-DNA Ligase IV in an extended flexible non-homologous end

joining complex. J Biol Chem. 291:26987–27006. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Weterings E, Verkaik NS, Keijzers G,

Florea BI, Wang SY, Ortega LG, Uematsu N, Chen DJ and van Gent DC:

The Ku80 carboxy terminus stimulates joining and artemis-mediated

processing of DNA ends. Mol Cell Biol. 29:1134–1142.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Xing M and Oksenych V: Genetic interaction

between DNA repair factors PAXX, XLF, XRCC4 and DNA-PKcs in human

cells. FEBS Open Bio. 9:1315–1326. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Britton S, Dernoncourt E, Delteil C,

Froment C, Schiltz O, Salles B, Frit P and Calsou P: DNA damage

triggers SAF-A and RNA biogenesis factors exclusion from chromatin

coupled to R-loops removal. Nucleic Acids Res. 42:9047–9062.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Berglund FM and Clarke PR: hnRNP-U is a

specific DNA-dependent protein kinase substrate phosphorylated in

response to DNA double-strand breaks. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

381:59–64. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Britton S, Froment C, Frit P, Monsarrat B,

Salles B and Calsou P: Cell nonhomologous end joining capacity

controls SAF-A phosphorylation by DNA-PK in response to DNA

double-strand breaks inducers. Cell Cycle. 8:3717–3722.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Hegde ML, Dutta A, Yang C, Mantha AK,

Hegde PM, Pandey A, Sengupta S, Yu Y, Calsou P, Chen D, et al:

Scaffold attachment factor A (SAF-A) and Ku temporally regulate

repair of radiation-induced clustered genome lesions. Oncotarget.

7:54430–54444. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Refaat AM, Nakata M, Husain A, Kosako H,

Honjo T and Begum NA: HNRNPU facilitates antibody class-switch

recombination through C-NHEJ promotion and R-loop suppression. Cell

Rep. 42(112284)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Tanaka TU: Kinetochore-microtubule

interactions: Steps towards bi-orientation. EMBO J. 29:4070–4082.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Biggins S and Walczak CF: Captivating

capture: How microtubules attach to kinetochores. Curr Biol.

13:R449–R460. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Ma N, Matsunaga S, Morimoto A, Sakashita

G, Urano T, Uchiyama S and Fukui K: The nuclear scaffold protein

SAF-A is required for kinetochore-microtubule attachment and

contributes to the targeting of Aurora-A to mitotic spindles. J

Cell Sci. 124:394–404. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Chun Y, Kim R and Lee S: Centromere

Protein (CENP)-W interacts with heterogeneous nuclear

ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) U and may contribute to

kinetochore-microtubule attachment in mitotic cells. PLoS One.

11(e0149127)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Kettenbach AN, Schweppe DK, Faherty BK,

Pechenick D, Pletnev AA and Gerber SA: Quantitative

phosphoproteomics identifies substrates and functional modules of

Aurora and Polo-like kinase activities in mitotic cells. Sci

Signal. 4(rs5)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Malik R, Lenobel R, Santamaria A, Ries A,

Nigg EA and Korner R: Quantitative analysis of the human spindle

phosphoproteome at distinct mitotic stages. J Proteome Res.

8:4553–4563. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Wang Z, Udeshi ND, Slawson C, Compton PD,

Sakabe K, Cheung WD, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF and Hart GW: Extensive

crosstalk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation regulates

cytokinesis. Sci Signal. 3(ra2)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Douglas P, Ye R, Morrice N, Britton S,

Trinkle-Mulcahy L and Lees-Miller SP: Phosphorylation of

SAF-A/hnRNP-U Serine 59 by Polo-Like Kinase 1 Is Required for

Mitosis. Mol Cell Biol. 35:2699–2713. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Shi W, Wang Q, Bian Y, Fan Y, Zhou Y, Feng

T, Li Z and Cao X: Long noncoding RNA PANDA promotes esophageal

squamous carcinoma cell progress by dissociating from NF-YA but

interact with SAFA. Pathol Res Pract. 215(152604)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Liang Y, Fan Y, Liu Y and Fan H: HNRNPU

promotes the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma by enhancing

CDK2 transcription. Exp Cell Res. 409(112898)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Song H, Li D, Wang X, Fang E, Yang F, Hu

A, Wang J, Guo Y, Liu Y, Li H, et al: HNF4A-AS1/hnRNPU/CTCF axis as

a therapeutic target for aerobic glycolysis and neuroblastoma

progression. J Hematol Oncol. 13(24)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Xu CL, Chen Y, Zhu TT, Sun ZJ and Chu JH:

Clinical significance and pathogenesis analysis of heterogeneous

nuclear ribonucleoprotein U in acute myeloid leukemia. Zhonghua Xue

Ye Xue Za Zhi. 43:745–752. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Chinese).

|

|

71

|

Han BY, Liu Z, Hu X and Ling H: HNRNPU

promotes the progression of triple-negative breast cancer via RNA

transcription and alternative splicing mechanisms. Cell Death Dis.

13(940)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Dong YY, Wang MY, Jing JJ, Wu YJ, Li H,

Yuan Y and Sun LP: Alternative Splicing Factor Heterogeneous

Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein U as a promising biomarker for gastric

cancer risk and prognosis with tumor-promoting properties. Am J

Pathol. 194:13–29. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Chen T, Zheng W, Chen J, Lin S, Zou Z, Li

X and Tan Z: Systematic analysis of survival-associated alternative

splicing signatures in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Cell

Biochem. 121:4074–4084. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Zhang W, Zheng Z, Wang K, Mao W, Li X,

Wang G, Zhang Y, Huang J, Zhang N, Wu P, et al: piRNA-1742 promotes

renal cell carcinoma malignancy by regulating USP8 stability

through binding to hnRNPU and thereby inhibiting MUC12

ubiquitination. Exp Mol Med. 55:1258–1271. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Hu WM, Li M, Ning JZ, Tang YQ, Song TB, Li

LZ, Zou F, Cheng F and Yu WM: FAM171B stabilizes vimentin and

enhances CCL2-mediated TAM infiltration to promote bladder cancer

progression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 42(290)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Shi ZD, Hao L, Han XX, Wu ZX, Pang K, Dong

Y, Qin JX, Wang GY, Zhang XM, Xia T, et al: Targeting HNRNPU to

overcome cisplatin resistance in bladder cancer. Mol Cancer.

21(37)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Wang X, Xu J, Li Q, Zhang Y, Lin Z, Zhai

X, Wang F, Huang J, Gao Q, Wen J, et al: RNA-binding protein hnRNPU

regulates multiple myeloma resistance to selinexor. Cancer Lett.

580(216486)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Li L, Yin JY, He FZ, Huang MS, Zhu T, Gao

YF, Chen YX, Zhou DB, Chen X, Sun LQ, et al: Long noncoding RNA

SFTA1P promoted apoptosis and increased cisplatin chemosensitivity

via regulating the hnRNP-U-GADD45A axis in lung squamous cell

carcinoma. Oncotarget. 8:97476–97489. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Valente ST and Goff SP: Inhibition of

HIV-1 gene expression by a fragment of hnRNP U. Mol Cell.

23:597–605. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Cao L, Liu S, Li Y, Yang G, Luo Y, Li S,

Du H, Zhao Y, Wang D, Chen J, et al: The Nuclear Matrix Protein

SAFA Surveils Viral RNA and Facilitates Immunity by Activating

Antiviral Enhancers and Super-enhancers. Cell Host Microbe.

26:369–384 e8. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Gupta AK, Drazba JA and Banerjee AK:

Specific interaction of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein

particle U with the leader RNA sequence of vesicular stomatitis

virus. J Virol. 72:8532–8540. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Hu X, Wu X, Ding Z, Chen Z and Wu H:

Characterization and functional analysis of chicken dsRNA binding

protein hnRNPU. Dev Comp Immunol. 138(104521)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Zhou H, Yan Y, Gao J, Ma M, Liu Y, Shi X,

Zhang Q and Xu X: Heterogeneous Nuclear Protein U Degraded the

m(6)A Methylated TRAF3 Transcript by YTHDF2 To Promote Porcine

Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Replication. J Virol.

97(e0175122)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Caliebe A, Kroes HY, van der Smagt JJ,

Martin-Subero JI, Tonnies H, van 't Slot R, Nievelstein RA, Muhle

H, Stephani U, Alfke K, et al: Four patients with speech delay,

seizures and variable corpus callosum thickness sharing a 0.440 Mb

deletion in region 1q44 containing the HNRPU gene. Eur J Med Genet.

53:179–185. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Depienne C, Nava C, Keren B, Heide S,

Rastetter A, Passemard S, Chantot-Bastaraud S, Moutard ML, Agrawal

PB, VanNoy G, et al: Genetic and phenotypic dissection of 1q43q44

microdeletion syndrome and neurodevelopmental phenotypes associated

with mutations in ZBTB18 and HNRNPU. Hum Genet. 136:463–479.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Epi4K Consortium; Epilepsy Phenome/Genome

Project. Allen AS, Berkovic SF, Cossette P, Delanty N, Dlugos D,

Eichler EE, Epstein MP, Glauser T, et al: De novo mutations in

epileptic encephalopathies. Nature. 501:217–221. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Shimada S, Oguni H, Otani Y, Nishikawa A,

Ito S, Eto K, Nakazawa T, Yamamoto-Shimojima K, Takanashi JI,

Nagata S and Yamamoto T: An episode of acute encephalopathy with

biphasic seizures and late reduced diffusion followed by hemiplegia

and intractable epilepsy observed in a patient with a novel

frameshift mutation in HNRNPU. Brain Dev. 40:813–818.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Durkin A, Albaba S, Fry AE, Morton JE,

Douglas A, Beleza A, Williams D, Volker-Touw CML, Lynch SA, Canham

N, et al: Clinical findings of 21 previously unreported probands

with HNRNPU-related syndrome and comprehensive literature review.

Am J Med Genet A. 182:1637–1654. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Wang T, Hoekzema K, Vecchio D, Wu H,

Sulovari A, Coe BP, Gillentine MA, Wilfert AB, Perez-Jurado LA,

Kvarnung M, et al: Large-scale targeted sequencing identifies risk

genes for neurodevelopmental disorders. Nat Commun.

11(4932)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Taylor J, Spiller M, Ranguin K, Vitobello

A, Philippe C, Bruel AL, Cappuccio G, Brunetti-Pierri N, Willems M,

Isidor B, et al: Expanding the phenotype of HNRNPU-related

neurodevelopmental disorder with emphasis on seizure phenotype and

review of literature. Am J Med Genet A. 188:1497–1514.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Roshon MJ and Ruley HE: Hypomorphic

mutation in hnRNP U results in post-implantation lethality.

Transgenic Res. 14:179–192. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|