Introduction

In recent years, the use of Traditional Chinese

medicine to improve metabolic diseases has gradually become a

research focus. Among numerous natural hypoglycemic active

ingredients, investigators have paid increasing attention to

resveratrol (RSV), which is a polyphenolic plant antitoxin

belonging to the stilbene family, widely found in grapes and other

plants, and has hypoglycemic activity (1). The mechanism of RSV in reducing

insulin resistance (IR) involves the regulation of multiple signal

transduction pathways, such as silent mating type information

regulation 2 homolog-1/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

coactivator-1α, inhibitor of κB kinase/nuclear factor κВ

inhibitor/nuclear factor κВ, adenosine phosphate kinase (AMPK) and

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B

(AKT)/endothelial nitric oxide synthase pathways (2). The in-depth study of these signaling

pathways has clarified some molecular mechanisms of the effects of

RSV (2). In insulin target tissues,

skeletal muscle accounts for 70-80% of the total glucose intake

stimulated by insulin, thus playing a crucial role in regulating

systemic glucose homeostasis (3).

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a

serine/threonine protein kinase with highly conserved structure and

function belonging to the PI3K family. mTOR-mediated signaling

pathways play crucial roles in metabolism, immunity, growth,

development, aging as well as other physiological processes

(4). Research has shown that mTOR

signaling is also involved in the occurrence and development of

numerous metabolic diseases, such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia and

osteoporosis (4). A previous study

found that mTOR functions as a nutrient receptor, and that the mTOR

signal was activated in various tissues of a high-fat diet (HFD) or

obese rodents (5), and was closely

related to the occurrence and development of IR (6,7).

Skeletal muscle anabolism is driven by numerous stimuli such as

growth factors, nutrients (including amino acids and glucose), and

mechanical stress. These stimuli are integrated by the mechanistic

target of mTOR signal transduction cascade (8).

The DNA-damage-inducible transcript factor 4 (DDIT4)

plays a role in insulin signal transduction, DNA damage repair,

nutritional deprivation, oxidative metabolism, endoplasmic

reticulum stress and the hypoxia response (9-14).

Some studies have found that DDIT4 is involved in nutritional

metabolism, and is crucial to insulin-mediated activation of AKT

and mTOR (15-17).

However, at present, there are few reports regarding the actions of

DDIT4 involving the mTOR pathway during IR. Notably, changes in

DDIT4 mRNA and protein have been observed in skeletal muscle under

various physiological conditions (such as nutrient consumption and

resistance exercise) and pathological conditions (including sepsis,

alcoholism, diabetes and obesity) suggesting a role for DDIT4 in

regulating mTOR-dependent skeletal muscle protein metabolism

(18).

In the present study, RSV was administered to

C57BL/6J mice with IR induced by an HFD to observe the effect of

RSV on insulin and mTOR signaling pathways as well as DDIT4, and to

explore the mechanism of the RSV-mediated reduction of IR, to

further understand the specific functions of RSV in glucose and

lipid metabolism.

Materials and methods

Animal experiments

A total of 33 healthy 6-week-old male C57BL/6J mice

weighing ~22 g were purchased from the Hebei Invivo Biotechnology

Co., Ltd. (license no. SCXK 2023-002) and raised in the barrier

system of the animal room at the Clinical Research Center of Hebei

General Hospital (Shijiazhuang, China). The humidity was controlled

at 40-60% with a room temperature at 20-25˚C with a standard 12-h

light-dark cycle. A week after adaptive feeding, mice were randomly

divided into the following two groups: Control group (CON, n=11)

and HFD group (n=22). The CON group was given an ordinary diet

(D12450J: 70% carbohydrate, 20% protein, 10% fat, 3.85 kcal/g), and

the HFD group was given an HFD (D12492J: 20% carbohydrate, 20%

protein, 60% fat, 5.24 kcal/g) (19). All feeds were purchased from Beijing

Huafukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. After 8 weeks of an HFD, mice

were fasted overnight (12 h) and then underwent an intraperitoneal

glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) (19). The tail tip blood glucose was

measured at point 0 using Roche rapid glucose meter test strips,

followed by intraperitoneal injection of 50% glucose injection at 2

g/kg (20-22).

Then, the tail tip blood glucose values were measured at 15, 30, 60

and 120 min using Roche rapid glucose meter test strips after

glucose treatment. The amount of blood used for measuring blood

glucose with a blood glucose meter was approximately 20 µl per

mouse at each time point (20-22).

The area under the glucose curve (AUC) was calculated (23); IPGTT-AUC=0.125 x BG0 + 0.25 x BG15 +

0.375 x BG30 + 0.75 x BG60 + 0.5 x BG120 (BGx=blood glucose values

at different time points) (23).

Eleven mice were randomly selected from the HFD group to form the

high-fat feeding with RSV intervention group (HFD + RSV group), and

were administered 100 mg/kg body weight RSV by gavage for 6 weeks

(24), while other mice in the HFD

group and the CON group were admnistered 0.9% sodium chloride

solution containing 0.1% DMSO by gavage.

After 6 weeks of treatment, IPGTT was performed

again to detect the blood glucose value of each mouse at each time

point, and then the calculated AUC was used to evaluate the degree

of IR. All three groups of mice were intraperitoneally injected

with 1.5 units of insulin (Merck KGaA)/40 g body weight, and then

anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 2% pentobarbital

sodium at a dose of 40 mg/kg. After 20 min, blood samples collected

by cardiac puncture were centrifuged at 1,500 x g for 10 min at

4˚C. The serum was collected and stored at -80˚C for the subsequent

determination of serological indicators. Cervical dislocation

caused rapid unconsciousness and death with minimal distress to the

mice, and was a humane way to euthanize the mice. Then, skeletal

muscle samples were quickly removed and stored in liquid nitrogen

for subsequent research. The present study was approved (approval

no. 2023-LW-055) by the Ethics Committee of Hebei General Hospital

(Shijiazhuang, China).

Serological indicators

Detection kits for total cholesterol (TC; cat. no.

A111-1-1), triglyceride (TG; cat. no. A110-1-1), low-density

lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C; cat. no. A113-1-1) and high-density

lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C; cat. no. A112-1-1) were acquired

from the Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute in accordance

with the manufacturer's instructions. Insulin concentrations were

obtained using an ELISA kit from ALPCO (cat. no. 80-INSMSU-E01) in

accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The Qualitative

Insulin Sensitivity Check Index (QUICKI) was determined according

to the equation: QUICKI=1/[log(I0) + log(G0)] (25), with I0=fasting insulin and

G0=fasting glucose.

Histological assessment of skeletal

muscle tissue

The skeletal muscle tissues of mice were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde at 4˚C for 6 h. Then, the samples were dehydrated

using a conventional alcohol gradient, clarified using xylene,

embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-µm slices. The sections were

then stained with an H&E Stain Kit (cat. no. G1005; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) using hematoxylin and eosin

solutions for 5 min staining each at room temperature. A Modified

Oil Red O Stain Kit (cat. no. G1261; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co. Ltd.) was used to detect lipid droplets in skeletal

muscle sections, which were stained with Modified Oil Red O Stain

Solution (included in the aforementioned kit) for 10 min at 25˚C,

and then stained with Mayer's Hematoxylin Solution (included in the

aforementioned kit) for 1 min at 25˚C. The staining of sections was

completed according to the manufacturer's protocol, and stained

sections were examined under a light microscope (magnification,

x400).

C2C12 cell culture

The C2C12 mouse myoblast cell line (cat. no.

CL-0044; Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) was

cultured in culture medium (cat. no. CM-0044 Procell Life Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) until the cells reached 70-80%

confluence. The differentiation medium (cat. no. PM150210A; Procell

Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and 2% horse serum (cat.

no. 164215; Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) were

used to induce differentiation of C2C12 cells. Mycoplasma

contamination was not detected in the cells. Differentiated C2C12

cells were then incubated with 0.5 mM palmitic acid (PA; cat. no.

800508; Merck KGaA) for 24 h, designated the PA group. RSV (cat.

no. R817263-5g; Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co. Ltd.)

was added to the medium at concentrations of 30 µM at room

temperature to form the PA + RSV group. Some of the PA + RSV group

cells were again divided into two groups: The PA + RSV + MHY1485

group C2C12 cells were treated with 10 µM MHY1485 (cat. no.

HY-B0795; MedChemExpress) to activate mTOR, and the PA + RSV +

DDIT4-siRNA group C2C12 cells were transfected with a small

interfering (si)RNA against DDIT4 (DDIT4-siRNA; Shanghai Genechem

Co. Ltd.), all incubated at 37˚C for 24 h. The cells were collected

for western blotting and cellular TG content determination.

Transfection with siRNAs

Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd. provided three

DDIT4-siRNAs (DDIT4-siRNA-1: Sense strand,

5'-GGGAAGGAAGUGUUCUCCAGGAAGU-3' and antisense strand,

5'-ACUUCCUGGAGAACACUUCCUUCCC-3'; DDIT4-siRNA-2: Sense strand,

5'-GCAGCUGCUCAUUGAAGAGUGUUGA-3' and antisense strand,

5'-UCAACACUCUUCAAUGAGCAGCUGC-3'; DDIT4-siRNA-3: Sense strand,

5'-GGUGCCCAUGUACUGGAGGAUUCAA-3' and antisense strand,

5'-UUGAAUCCUCCAGUACAUGGGCACC-3'), along with a negative control

siRNA (sense strand, 5'-GGUCUUACGUCAGUCACAAUAUCUG-3' and antisense

strand, 5'-CAGAUAUUGUGACUGACGUAAGACC-3'). To prepare the RNA

oligonucleotide stock solution, 20 pmol of siRNA was mixed with 50

µl of Opti-MEM I reduced serum medium (cat. no. 31985-062; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and stored at -20˚C. Additionally, 1 µl of

Lipofectamine® 2000 (cat. no. 11668019; Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was diluted in 50 µl of Opti-MEM I

medium. For experiments, the RNA oligonucleotide stock solution and

the diluted Lipofectamine 2000 solution were mixed to prepare

transfection complexes at room temperature. Cells were seeded into

24-well plates once they reached ~40% confluence at 37˚C.

Transfection was performed when the cells reached ~60% confluence,

with 100 µl siRNA transfection complexes at a concentration of 50

nM added to each well and incubated at 37˚C for 24 h. Western

blotting was performed 24 h after transfection to assess the

efficiency of the different siRNAs and determine the most effective

one for future experiments. The optimal siRNA was determined to be

DDIT4-siRNA-1.

TG assay

Cellular TG content was measured using a TG

detection kit (cat. no. ab65336; Abcam Plc) according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

Glucose content in culture medium

The glucose oxidase assay kit (cat. no. E1010-500;

Beijing Applygen Gene Technology Co., Ltd.) was used to measure the

remaining glucose content in culture medium as per the

manufacturer's instructions.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA from mouse skeletal muscle tissues was

extracted using Trizol reagent [ref. no. DP424; Tiangen Biotech

(Beijing) Co. Ltd.] and was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a

Fastking RT Kit [ref. no. KR116; Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co.

Ltd.] for qPCR. RNA was tested for purity and concentration using

NanoDrop® 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Amplification was performed using the SuperReal PreMix Plus (SYBR

Green) [ref. no. GFP205; Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co. Ltd.] in an

Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The cycling conditions were as follows: 3 min of

pre-denaturation at 95˚C, then 5 sec at 95˚C, and 32 sec at 60˚C,

with 41 cycles in total. The melting point curve was established at

60-95˚C. The expression levels of PI3K, insulin receptor substrate

(IRS)-1, AKT, glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4), mTOR, p70

ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K/S6K1) and DDIT4 mRNA in

skeletal muscle tissue were evaluated. β-actin was used as the

internal reference control for genes. Relative gene expression

levels were quantified by the 2-ΔΔCq method (26). The specific primers involved in the

study are listed in Table I.

| Table IPrimers used for real-time

quantitative polymerase chain reaction. |

Table I

Primers used for real-time

quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

| Gene | Primer | Sequence

(5'-3') |

|---|

| PI3K | Forward |

5'-CCCATGGGACAACATTCCAA-3' |

| | Reverse |

5'-CATGGCGACAAGCTCGGTA-3' |

| AKT | Forward |

5'-TCAGGATGTGGATCAGCGAGA-3' |

| | Reverse |

5'-CTGCAGGCAGCGGATGATAA-3' |

| IRS-1 | Forward |

5'-GCACCTGGTGGCTCTCTACAC-3' |

| | Reverse |

5'-TCGCTATCCGCGGCAAT-3' |

| GLUT4 | Forward |

5'-GTGACTGGAACACTGGTCCTA-3' |

| | Reverse |

5'-CCAGCCACGTTGCATTGTAG-3' |

| DDIT4 | Forward |

5'-TACTGCCCACCTTTCAGTTG-3' |

| | Reverse |

5'-GTCAGGGACTGGCTGTAACC-3' |

| mTOR | Forward |

5'-GCGGCCTGGAAATGCGGAAGTGG-3' |

| | Reverse |

5'-AAAGCCCCAAGGAGCCCCAACA-3' |

| p70S6K | Forward |

5'-CACTCAGGCCCCCCTACACT-3' |

| | Reverse |

5'-GCCGTCACTGAAAACCAAGTTC-3' |

| β-actin | Forward |

5'-GGTGGGAATGGGTCAGAAGG-3' |

| | Reverse |

5'-AGGTCTCAAACATGATCTGGGT-3' |

Western blotting

Skeletal muscle samples were added to 0.5 ml of

pre-cooled lysate at 4˚C, and then homogenized and stored at 4˚C

overnight. Subsequently, the tissue homogenate was centrifuged at

16,200 x g at 4˚C for 15 min and the supernatants were collected.

C2C12 cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. C1053-100;

Applygen Technologies, Inc.) to extract total cellular proteins.

The same amounts of protein (~50 µg/lane) for different group

samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis (5% resolving gel, 10% stacking gel), and then

transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, which were

blocked in 5% skimmed milk at room temperature for 2 h. The

membranes were then incubated with the primary antibodies at 4˚C

overnight at the following concentrations: Phosphorylated (p)-IRS-1

(rabbit antibody; 1:1,000; cat. no. ab5599; Abcam Ltd.), total

(t)-IRS-1 (rabbit antibody; 1:1,000; cat. no. ab52167; Abcam Ltd.),

p-AKT (rabbit antibody; 1:1,000; cat. no. AA329; Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology), t-AKT (rabbit antibody; 1:1,000; cat. no. AA326;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), p-PI3K (rabbit antibody;

1:1,000; cat. no. AF5905; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology),

t-PI3K (rabbit antibody; 1:1,000; cat. no. 20583-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), GLUT4 (rabbit antibody; 1:3,000; cat. no. ab65267;

Abcam Ltd.), DDIT4 (rabbit antibody; 1:2,000; cat. no. AF5147;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), p-mTOR (rabbit antibody;

1:4,000; cat. no. ab109268; Abcam Ltd.), t-mTOR (rabbit antibody;

1:4,000; cat. no. ab32028; Abcam Ltd.), p-p70S6K (rabbit antibody;

1:1,000; cat. no. ab59208; Abcam Ltd.), t-p70S6K (rabbit antibody;

1:2,000; cat. no. ab32529; Abcam Ltd.), and β-actin (rabbit

antibody; 1:5,000; cat. no. 20536-1-AP; Proteintech Group Inc.).

After three washes with Tris-buffered saline, the membranes were

incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary

antibodies (anti-rabbit; 1:5,000; cat. no. S0001; Affinity

Biosciences) for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, the washed

membranes were immersed in chemiluminescence solution (cat. no.

34580; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 2 min, and images were

acquired using a Gel Imager System (GDS8000; UVP, Inc.). The Alpha

software processing system (AlphaEaseFC 4.0; ProteinSimple) was

used to measure the optical densities of the target bands.

Statistical analyses

The SPSS v22.0 (IBM, Inc.) was used for data

analysis. The results are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation (SD). Independent sample t-test was used to analyze two

normally distributed sample comparisons. One-way ANOVA was used for

statistical analysis followed by the Bonferroni's multiple

comparison test or Tamhane's multiple comparison test. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Each experiment was performed in triplicate to ensure reliability

and reproducibility of the results.

Results

Establishment of the C57BL/6J mouse

model with HFD-induced IR

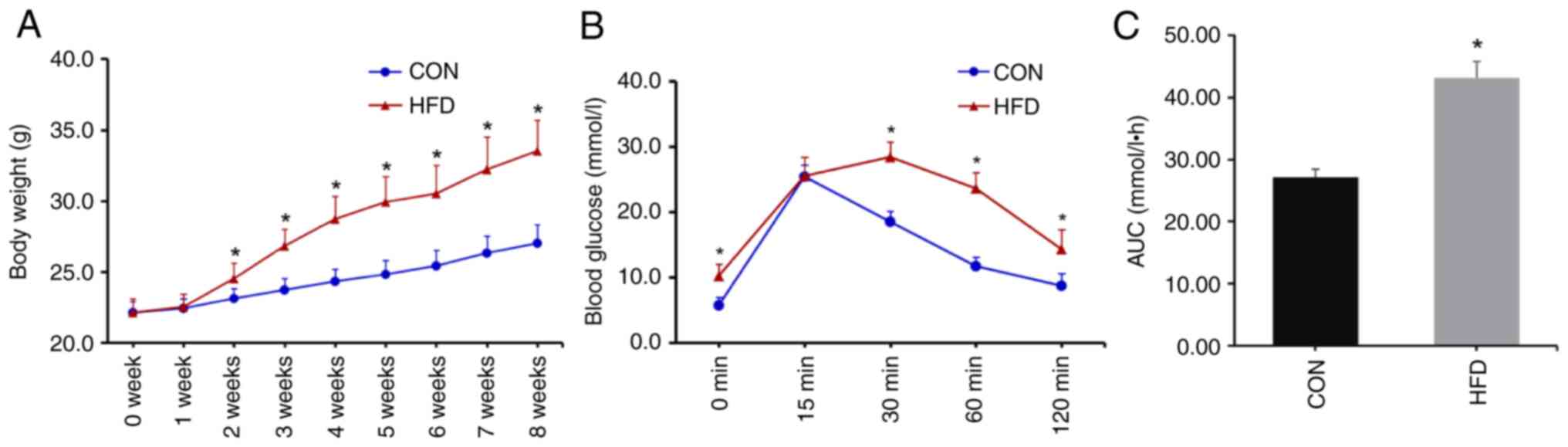

There were no differences in initial body weights

between the CON and HFD groups. From the second week of high-fat

feeding, the body weights of mice in the HFD group were

significantly higher than in the CON group (Fig. 1A). The IPGTT was performed after 8

weeks of diet consumption. After fasting for 12 h, there was no

difference in weight loss between the two groups (Table II). Blood glucose levels in the HFD

group were significantly higher at 0, 30, 60 and 120 min than

corresponding levels in the CON group (Fig. 1B). Compared with the CON group, the

AUC was significantly increased in the HFD group (Fig. 1C), indicating that the IR model was

successfully established.

| Table IIWeight loss in mice after 12 h of

fasting. |

Table II

Weight loss in mice after 12 h of

fasting.

| | First fasting for

12 h | Second fasting for

12 h |

|---|

| Groups | CON group

(n=11) | HFD group

(n=22) | CON group

(n=11) | HFD group

(n=11) | HFD + RSV group

(n=11) |

|---|

| Weight loss

(g) | 2.6±0.2 | 2.7±0.2 | 3.4±0.2 | 3.7±0.3 | 3.6±0.4 |

| t/F | 1.353 | 2.655 |

| P-value | 0.186 | 0.087 |

Effects of RSV administration on body

weight and blood glucose, insulin, as well as lipid levels in mice

with IR

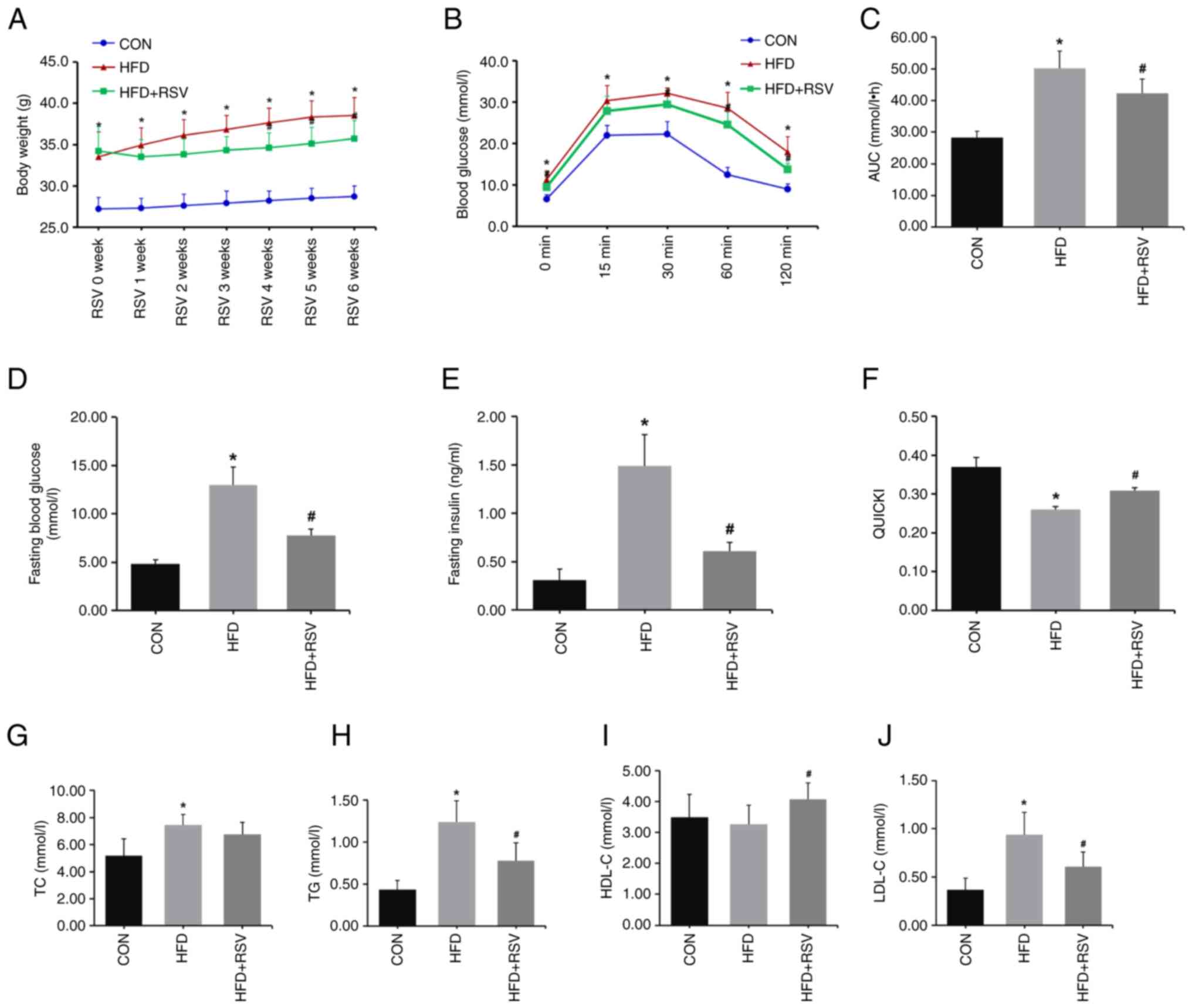

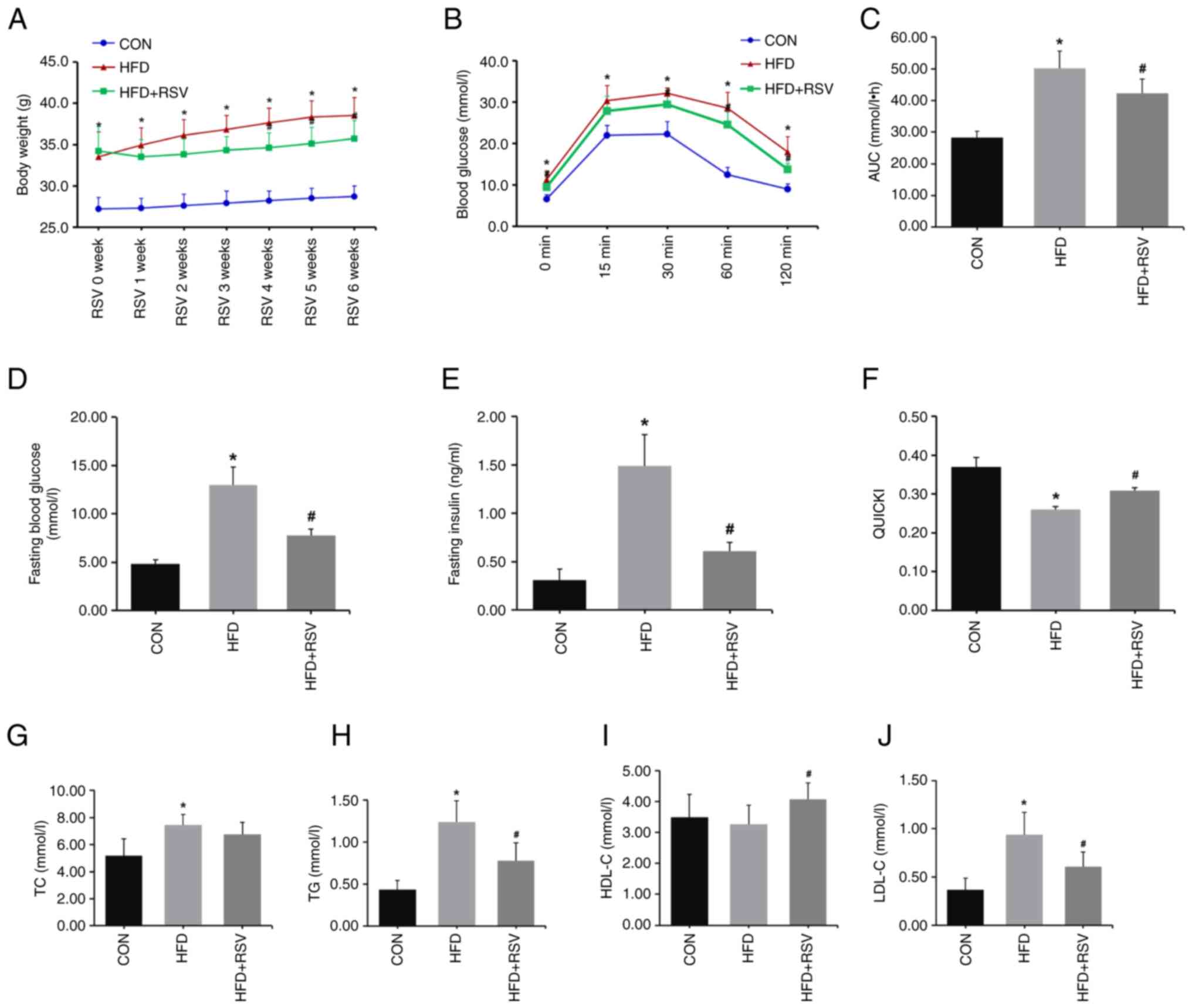

Following high-fat feeding, the body weight of the

HFD group was significantly higher than that in the CON group.

After RSV administration for 4 weeks, the body weight of the HFD +

RSV group was lower than that in the HFD group (Fig. 2A).

| Figure 2Effects of RSV on body weight, and

blood glucose, as well as insulin and lipid levels in mice with

insulin resistance. (A) Body weight of mice with RSV treatment for

6 weeks. (B) The levels of blood glucose at 0, 15, 30, 60 and 120

min of the intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test after RSV

administration for 6 weeks. (C) AUC of glucose. (D) Fasting blood

glucose. (E) Fasting insulin. (F) QUICKI value. (G) TC level. (H)

TG level. (I) HDL-C level. (J) LDL-C level. Data are presented as

the mean ± SD (n=11). One-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's or

Tamhane's multiple comparison post hoc tests, were used for

statistical analysis. *P<0.05 vs. the CON group;

#P<0.05 vs. the HFD group. RSV, resveratrol; AUC,

area under the curve; QUICKI, Qualitative Insulin Sensitivity Check

Index; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; HDL-C, high-density

lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density

lipoprotein-cholesterol; CON, control; HFD, high-fat diet. |

The IPGTT test was performed on three groups of mice

after 6 weeks of treatment with RSV. After fasting for 12 h, there

was no difference in weight loss among the three groups (Table II). The experiment determined that

the maximum percentage of body weight loss that was observed in the

study was 10.6% after fasting for 12 h. Compared with the CON

group, blood glucose levels were higher at 0, 15, 30, 60 and 120

min (Fig. 2B), and the AUC was

increased in the HFD group (Fig.

2C). Compared with the HFD group, blood glucose levels were

lower at 0, 30, 60 and 120 min, with no difference at 15 min

(Fig. 2B), and the AUC was

significantly decreased in the HFD + RSV group (Fig. 2C).

Compared with the CON group, the fasting blood

glucose and insulin levels were significantly higher (Fig. 2D and E), and the QUICKI value was lower in the

HFD group (Fig. 2F). Compared with

the HFD group, fasting blood glucose and insulin levels were

significantly lower (Fig. 2D and

E), and the QUICKI value was higher

in the HFD + RSV group (Fig. 2F).

These data indicated that RSV may significantly ameliorate the IR

of HFD-fed mice.

In addition, serum concentrations of TG, TC and

LDL-C were significantly increased in the HFD group compared with

the CON group (Fig. 2G, H and J).

Compared with the HFD group, TG and LDL-C were significantly

decreased, and HDL-C was significantly higher in the HFD + RSV

group, with no statistical difference in TC levels between the two

groups (Fig. 2G-J).

Effects of RSV on histology and lipid

accumulation in skeletal muscle of mice with IR

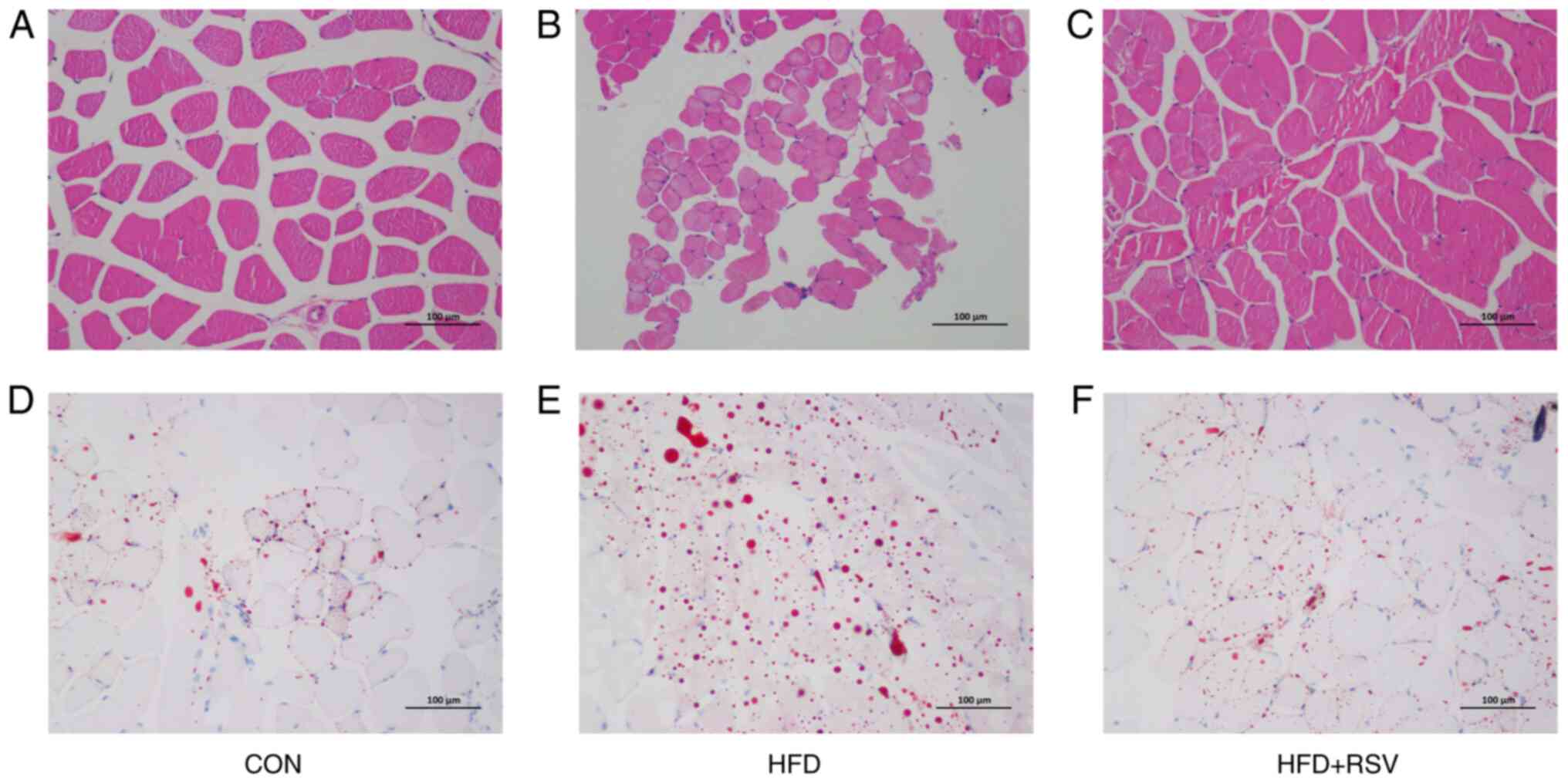

The H&E staining revealed normal histology of

skeletal muscle cells in the CON group (Fig. 3A). However, in the HDF group, the

cellular structure of skeletal muscle cells was fuzzy and

disordered, with fat drop vacuoles of different sizes in the

cytoplasm, constricting the nuclei, which were closer to the outer

cell membrane (Fig. 3B). In the HFD

+ RSV group, the morphology of skeletal muscle cells resembled

morphological features between those of the CON and HFD groups,

with lipid droplet vacuoles significantly reduced compared with

those in the HFD group (Fig. 3C).

Oil Red O staining showed larger numbers of red fat droplets in

skeletal muscle cells of the HFD group compared with the CON group

(Fig. 3D and E). The number of red fat droplets in

skeletal muscle cells of the HFD + RSV group was decreased compared

with the HFD group, and was between the numbers found in the CON

and HFD groups (Fig. 3D-F).

Effects of RSV on mRNA and protein

expression levels of insulin signaling pathway factors in skeletal

muscle tissue of mice with IR

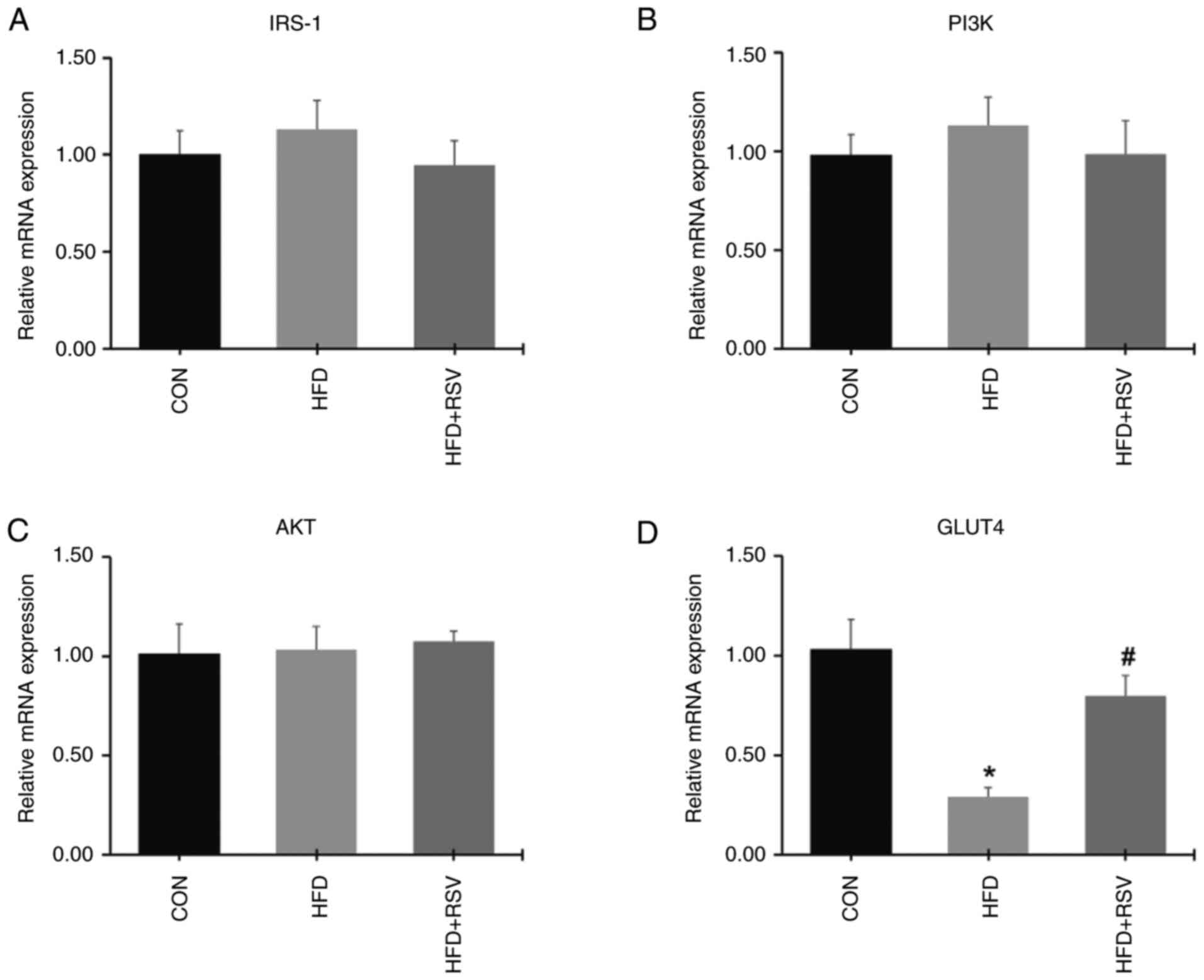

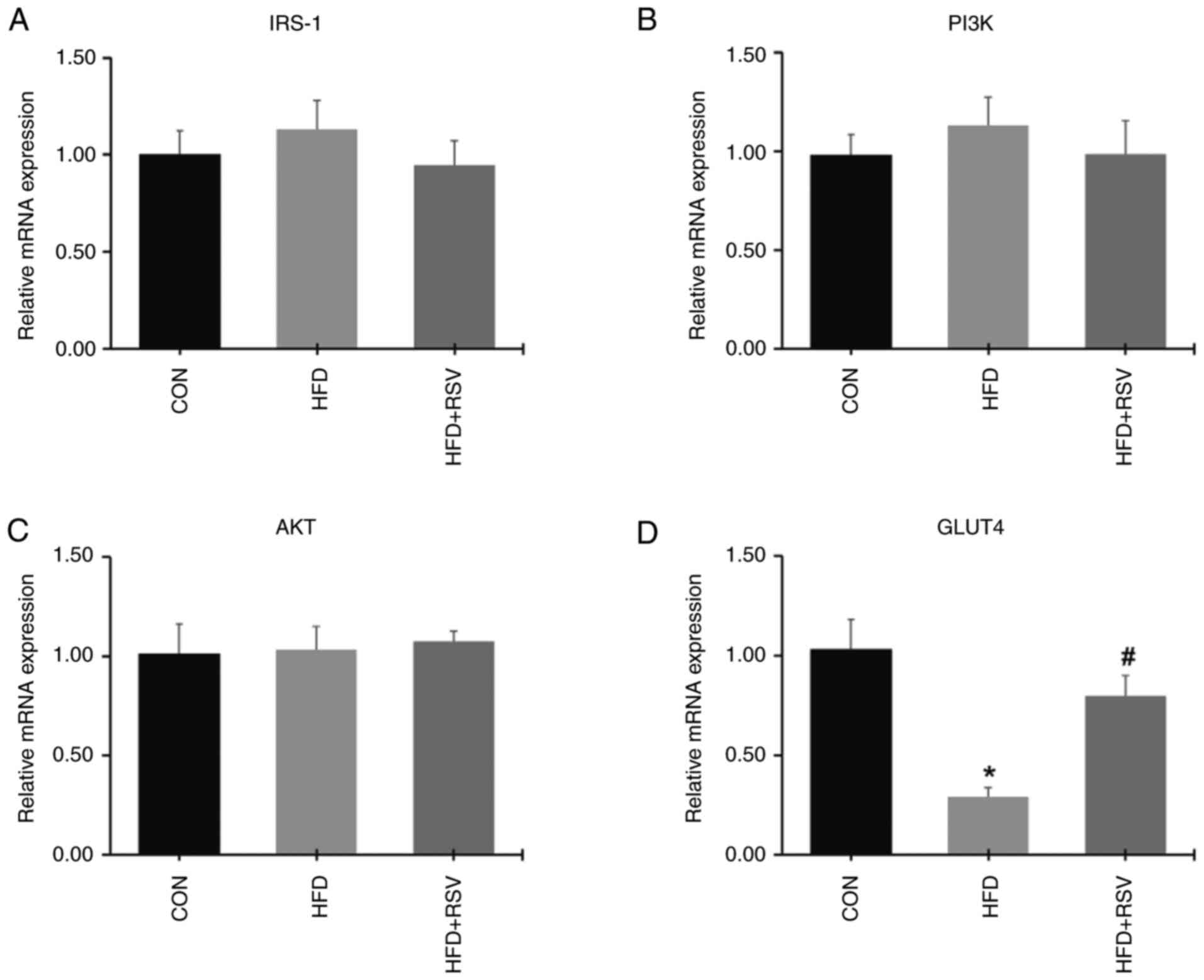

There were no differences in the mRNA expression

levels of IRS-1, PI3K and AKT in skeletal muscle from the three

groups of mice (Fig. 4A-C). In the

HFD group, the expression level of GLUT4 mRNA was significantly

decreased compared with the CON group (Fig. 4D). Compared with the HFD group, the

expression level of GLUT4 mRNA was upregulated in the HFD + RSV

group (Fig. 4D).

| Figure 4Effect of RSV on the expression

levels of IRS-1, PI3K, AKT and GLUT4 mRNA in skeletal tissue. (A)

IRS-1, (B) PI3K, (C) AKT and (D) GLUT4 mRNA levels. Data are

presented as the mean ± SD (n=11). *P<0.05 vs. the

CON group; #P<0.05 vs. the HFD group. RSV,

resveratrol; IRS-1, insulin receptor substrate-1; PI3K,

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; AKT, protein kinase B; GLUT4,

glucose transporter 4; CON, control; HFD, high-fat diet. |

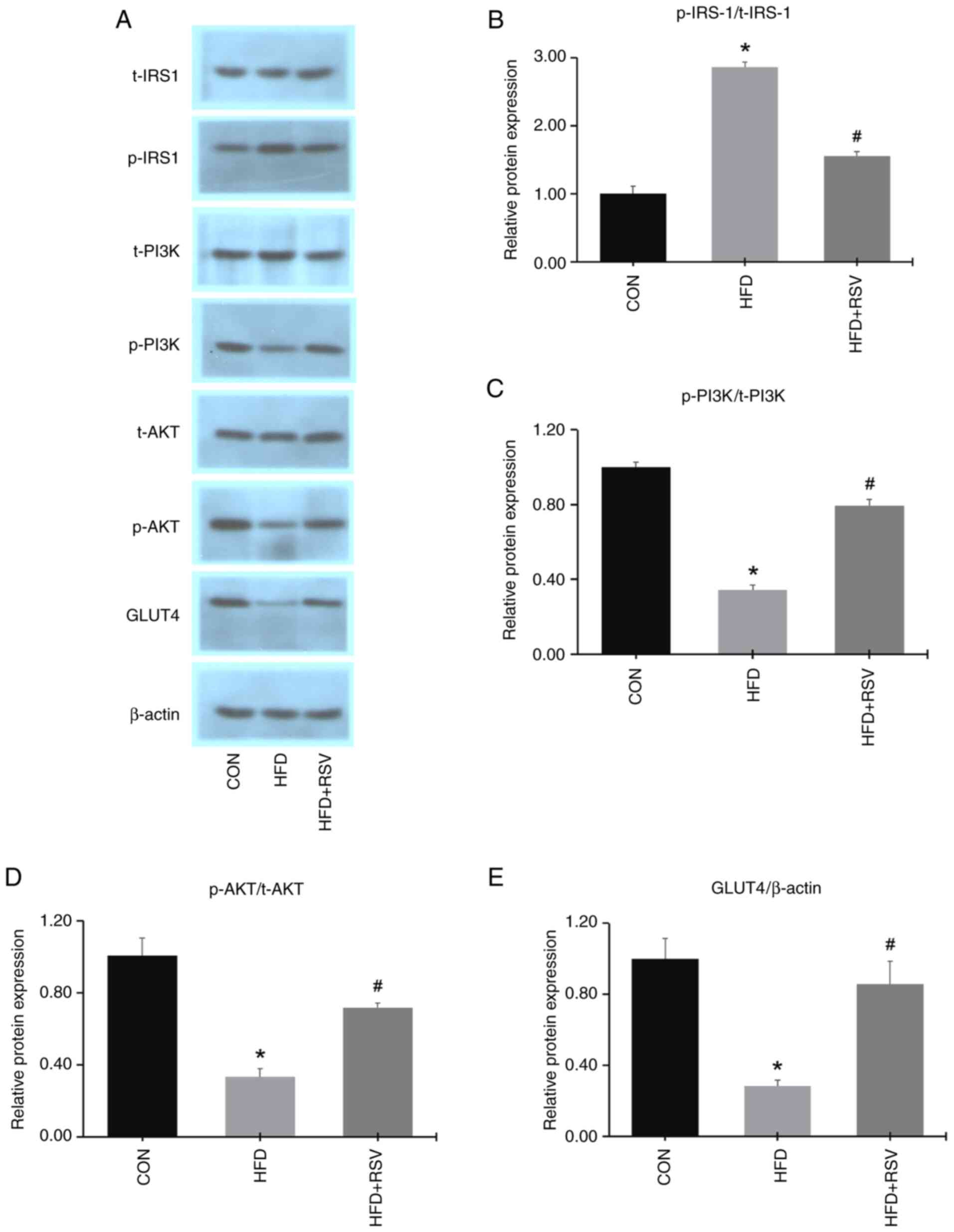

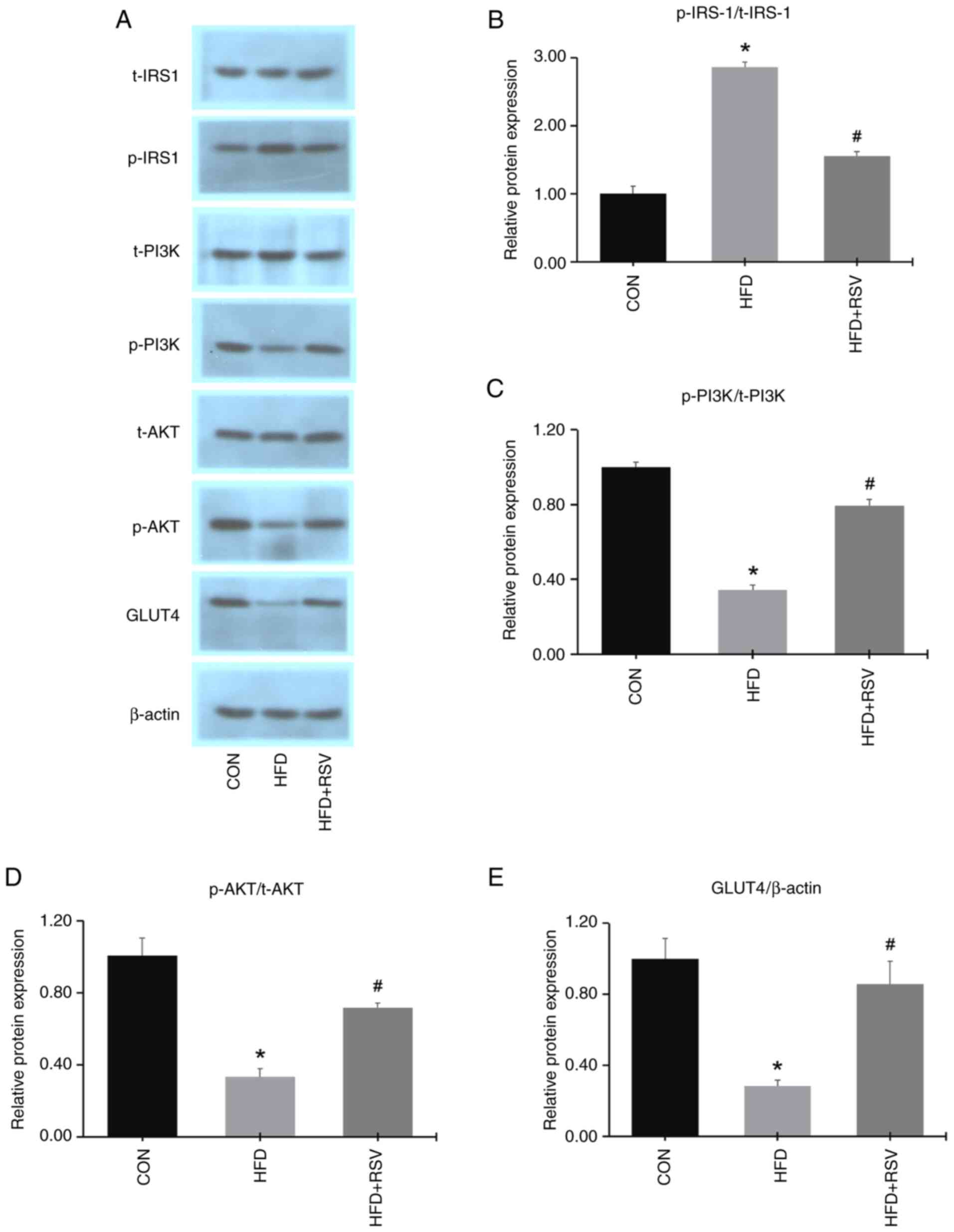

Western blotting showed that there were no

differences in the total protein expression levels of IRS-1, PI3K

and AKT in skeletal muscle from the three groups (Fig. 5A). Compared with the CON group, the

expression levels of p-PI3K, p-AKT and GLUT4 were decreased, while

the expression of p-IRS-1 was increased in the HFD group (Fig. 5A and E). Moreover, the phosphorylated

protein-to-total protein ratios for PI3K and AKT were

downregulated, while that for IRS-1 was upregulated, in the HFD vs.

the CON groups (Fig. 5B-D).

Compared with the HFD group, the protein expression levels of

p-PI3K, p-AKT and GLUT4 were increased, while the expression of

p-IRS-1 was decreased in the HFD + RSV group (Fig. 5A and E). Furthermore, the phosphorylated

protein-to-total protein ratios for PI3K and AKT were upregulated,

while that for IRS-1 was downregulated, in the HFD + RSV group

relative to the HFD group (Fig.

5B-D). These data suggested that administration of RSV in mice

with IR could activate the IRS-1/PI3K/AKT/GLUT4 signaling

pathway.

| Figure 5Effects of RSV on the protein

expression levels of insulin signaling pathway factors in skeletal

muscle. (A) Bands of various insulin signaling pathway proteins.

(B) p-IRS-1/t-IRS-1, (C) p-PI3K/t-PI3K, (D) p-AKT/t-AKT and (E)

GLUT4/β-actin protein expression levels. Data are presented as the

mean ± SD (n=11). *P<0.05 vs. the CON group;

#P<0.05 vs. the HFD group. RSV, resveratrol; p-,

phosphorylated; t-, total; IRS-1, insulin receptor substrate-1;

PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; AKT, protein kinase B; GLUT4,

glucose transporter 4; CON, control; HFD, high-fat diet. |

Effects of RSV on mRNA and protein

expression levels of DDIT4, mTOR and p70S6K in skeletal tissue of

mice with IR

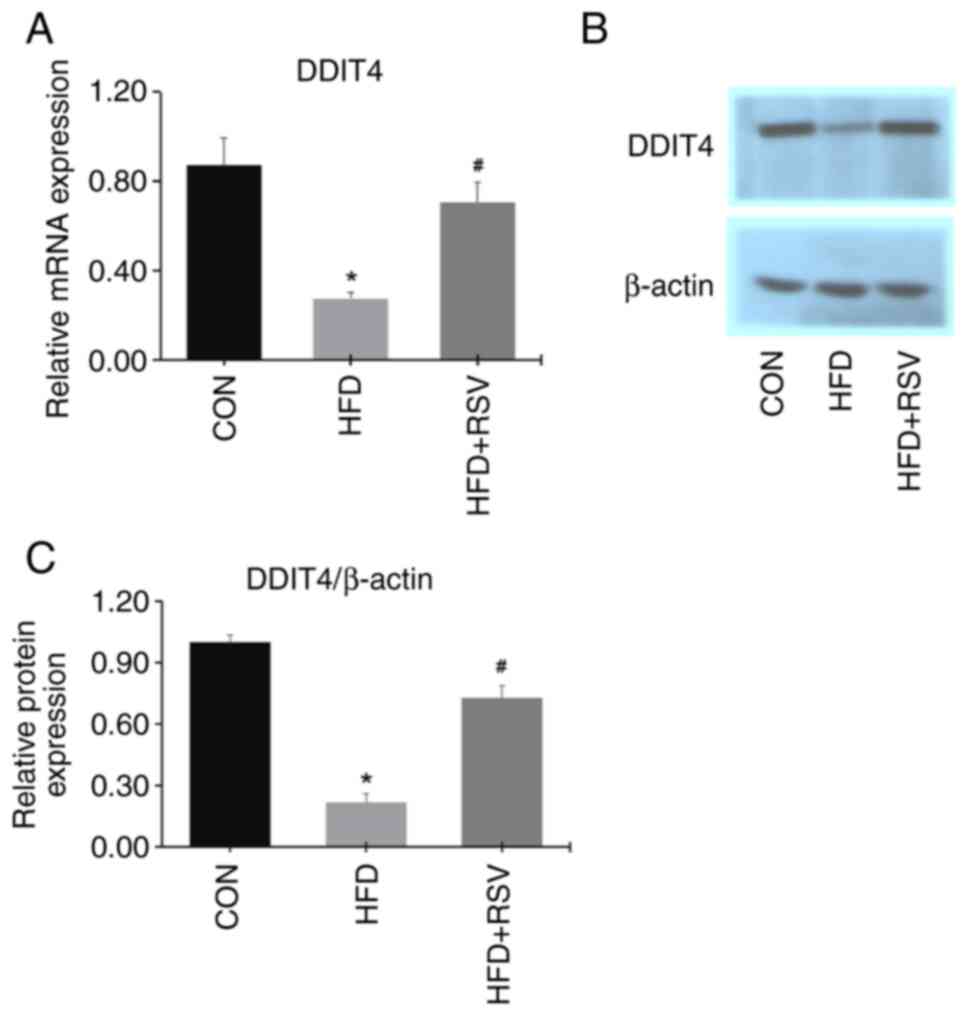

Compared with CON mice, the mRNA and protein

expression levels of DDIT4 in skeletal muscle were significantly

decreased in the HFD mice (Fig.

6A-C), indicating that the expression of DDIT4 was decreased

under the IR conditions induced by the HFD. However, the mRNA and

protein expression levels of DDIT4 in skeletal muscle were

increased in the HFD + RSV group compared with the HFD group,

indicating that RSV promotes the expression of DDIT4 in mice with

IR.

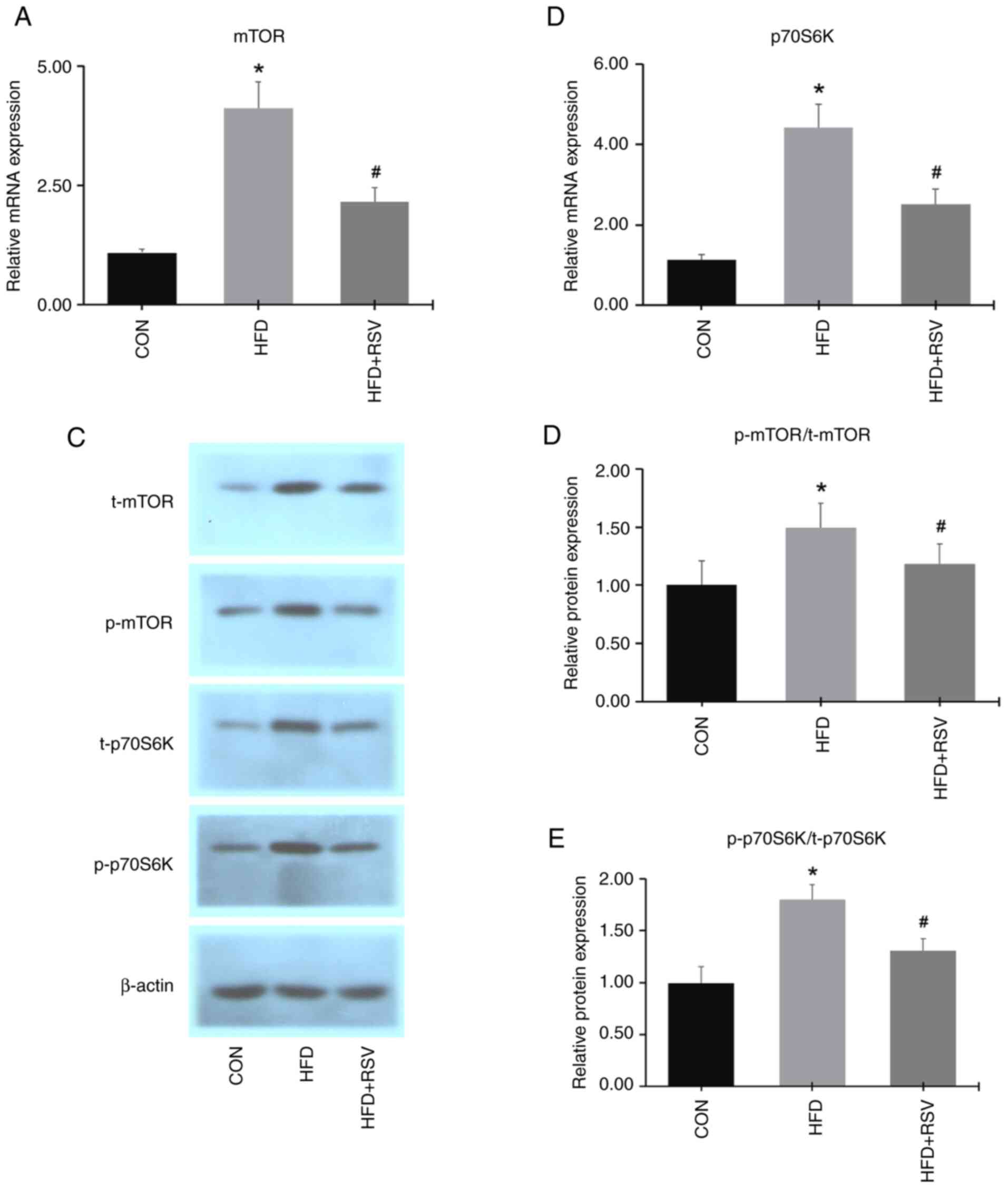

Compared with the CON group, the mRNA expression

levels of mTOR and p70S6K in skeletal muscle tissue were

significantly increased in the HFD group. However, the mRNA

expression levels of mTOR and p70S6K in skeletal muscle were

significantly decreased in the HFD + RSV group compared with the

HFD group (Fig. 7A and B).

Western blotting results showed that the expression

levels of total and phosphorylated mTOR and p70S6K proteins in

skeletal muscle tissue were increased in the HFD group compared

with the CON group (Fig. 7C). The

expression levels of total and phosphorylated mTOR and p70S6K

proteins in skeletal muscle from the HFD + RSV group were

significantly decreased compared with the HFD group (Fig. 7C and E). Furthermore, RSV reduced the increasing

trend of the phosphorylated protein-to-total protein ratios for

mTOR and p70S6K induced by the HFD (Fig. 7D and E). These findings indicated that RSV

inhibited the expression levels of mTOR and p70S6K in mice with

IR.

Expression of DDIT4, mTOR, PI3K, AKT,

and GLUT4 in MHY1485-treated C2C12 cells

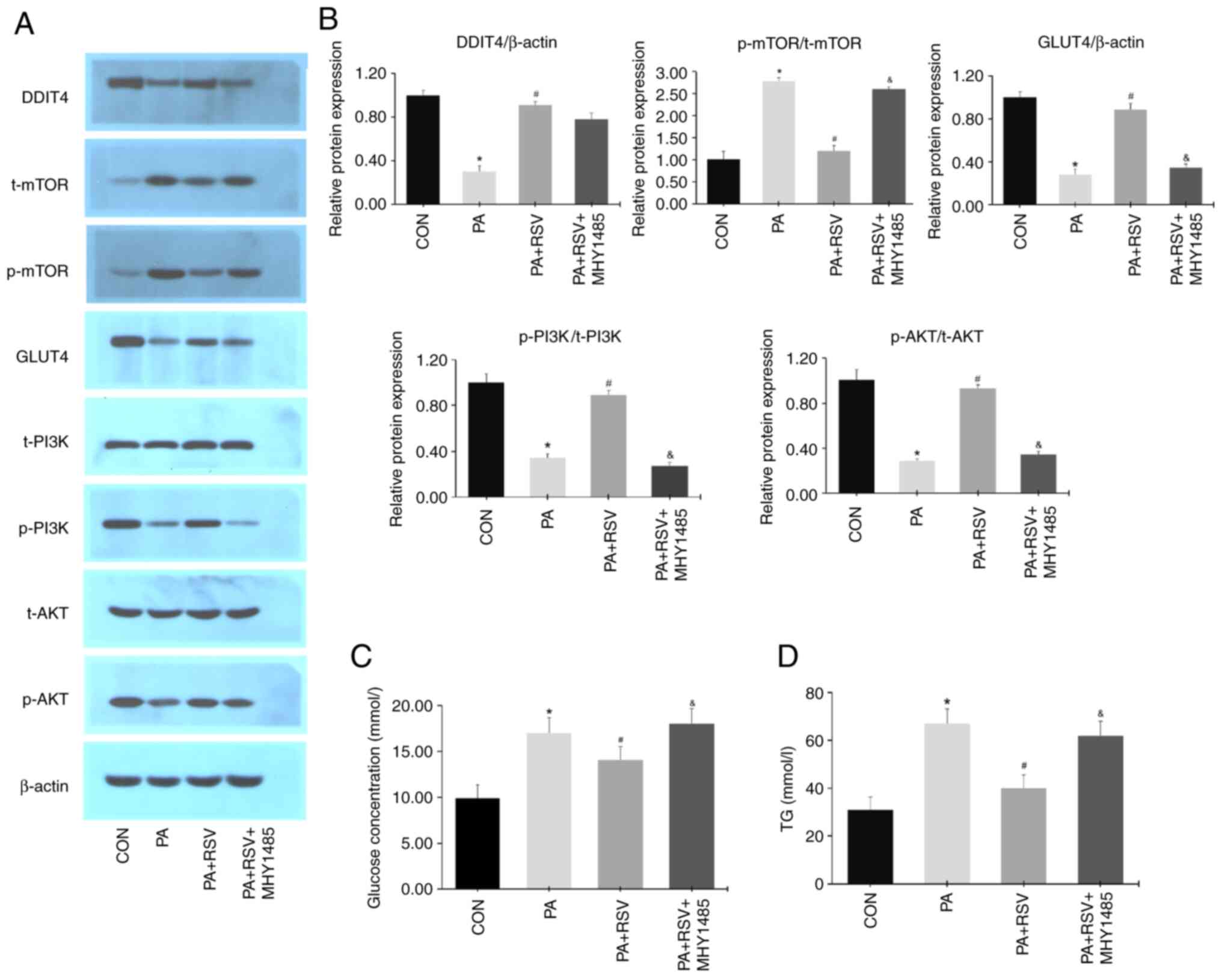

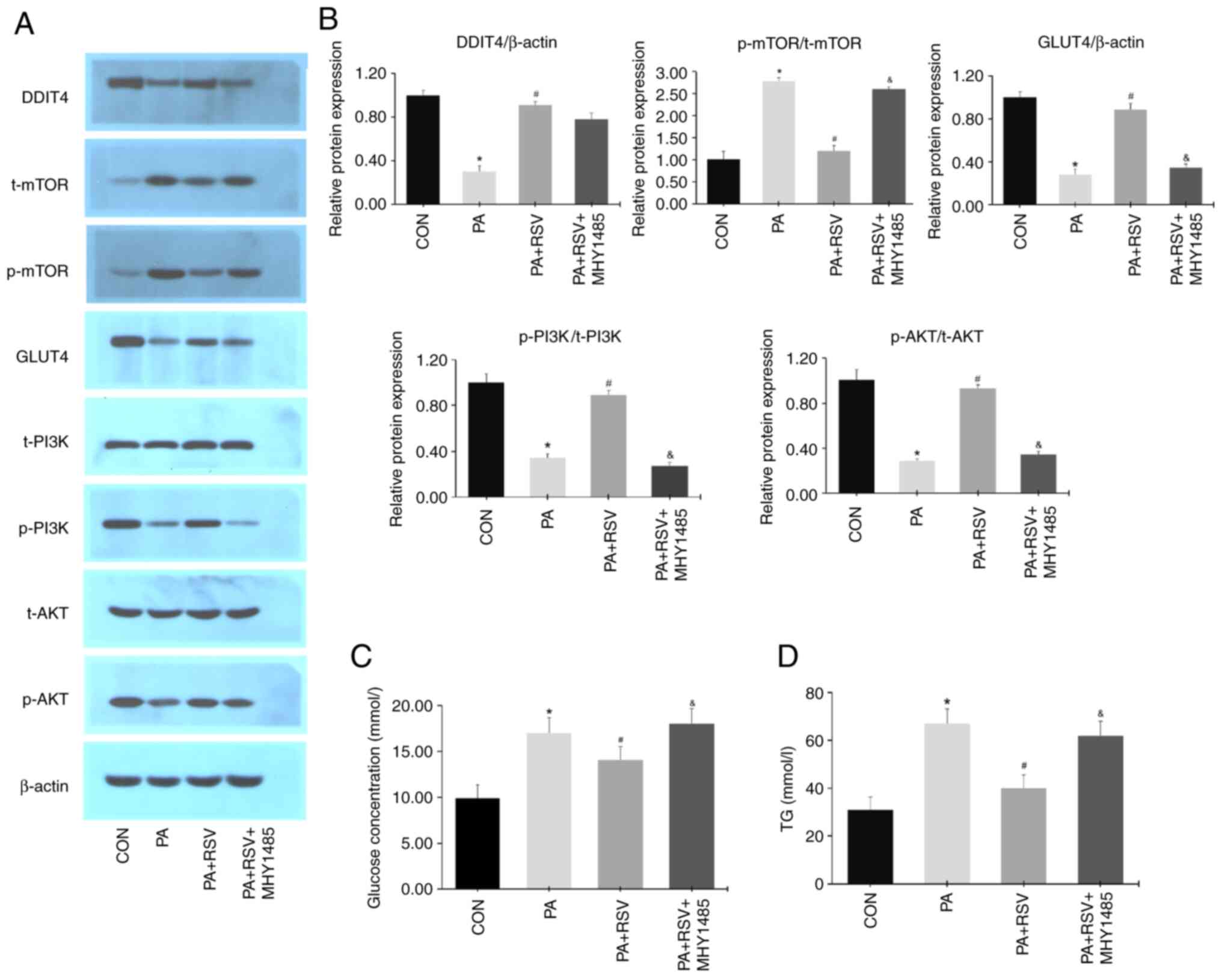

Compared with those in the PA group, the protein

expression levels of DDIT4, p-PI3K/t-PI3K, p-AKT/t-AKT and GLUT4

were increased, whereas those of p-mTOR/t-mTOR were decreased in

the PA + RSV group (Fig. 8A and

B). There were no differences in

the protein expression levels of DDIT4 between the PA + RSV group

and PA + RSV + MHY1485 group (Fig.

8A and B). Compared with the PA

+ RSV group, the protein expression levels of p-PI3K/t-PI3K,

p-AKT/t-AKT and GLUT4 were decreased, whereas those of

p-mTOR/t-mTOR were increased in the PA + RSV + MHY1485 group

(Fig. 8A and B). Compared with the PA group, the glucose

concentration was significantly decreased in the culture medium

from the PA + RSV group (Fig. 8C).

Compared with the PA + RSV group, the glucose concentration was

significantly increased in the culture medium from the PA + RSV +

MHY1485 group (Fig. 8C). The TG

content was decreased in the PA + RSV group cells compared with

those in the PA group (Fig. 8D).

The TG content was increased in the PA + RSV + MHY1485 group cells

compared with those in the PA + RSV group (Fig. 8D).

| Figure 8Expression of DDIT4, mTOR, GLUT4,

PI3K, and AKT in MHY1485-treated IR C2C12 cells. (A) Protein

expression levels of DDIT4, mTOR, GLUT4, PI3K, AKT after the

activation of mTOR. (B) Semi-quantification of p-protein/t-protein

ratios for mTOR, PI3K, AKT and protein expression levels of DDIT4,

GLUT4 after MHY1485 treatment. (C) Glucose levels in culture medium

after MHY1485 treatment. (D) Cell TG levels after MHY1485

treatment. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3).

*P<0.05 vs. the CON group; #P<0.05 vs.

the PA group; &P<0.05 vs. the PA + RSV group.

DDIT4, DNA-damage-inducible transcript 4; mTOR, mammalian target of

rapamycin; GLUT4, glucose transporter 4; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase; AKT, protein kinase B; IR, insulin resistance; p-,

phosphorylated; t-, total; TG, triglyceride; CON, control; PA,

palmitic acid; RSV, resveratrol. |

Expression of DDIT4, mTOR, PI3K, AKT,

and GLUT4 in C2C12 cells with silencing of DDIT4

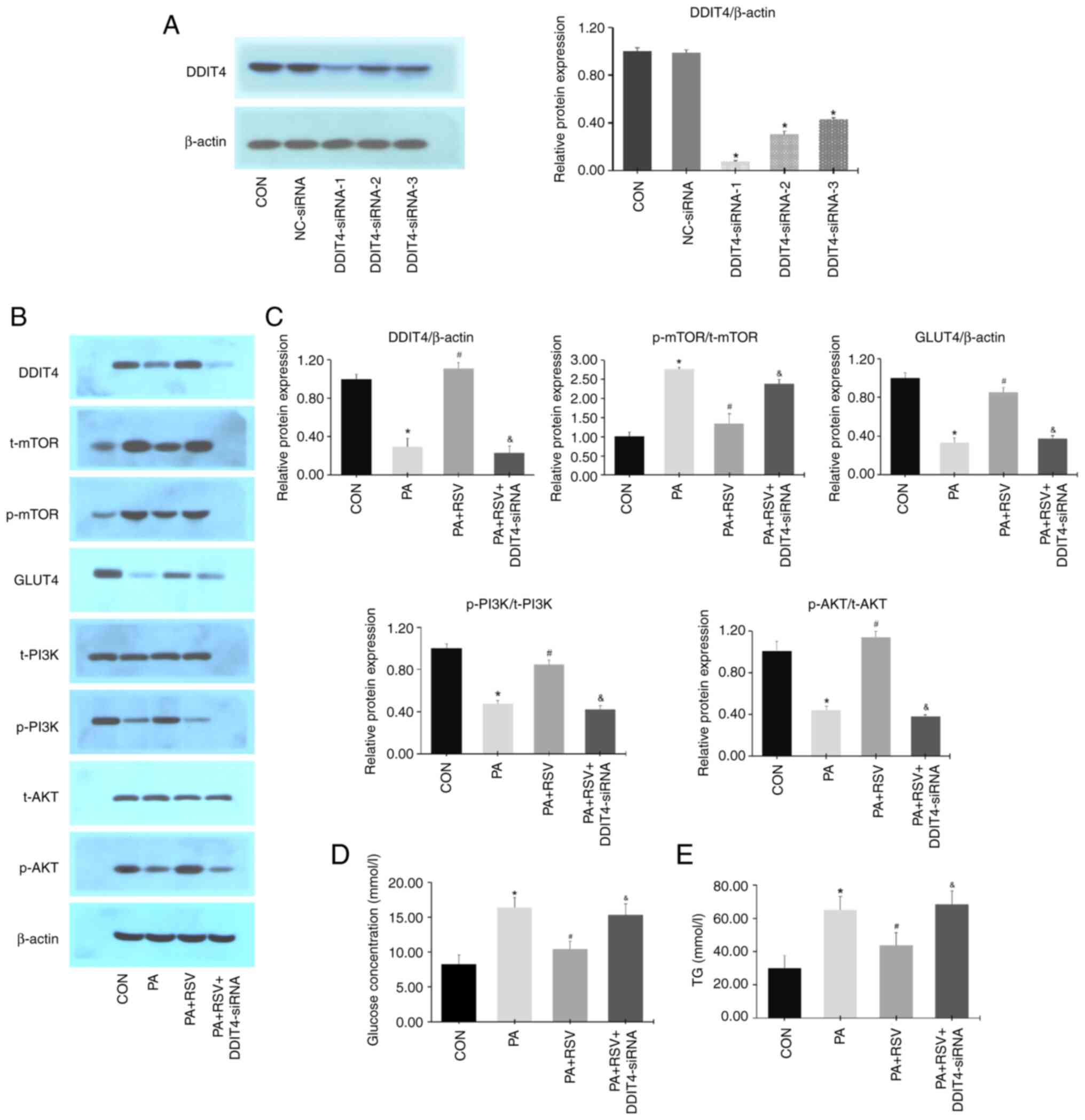

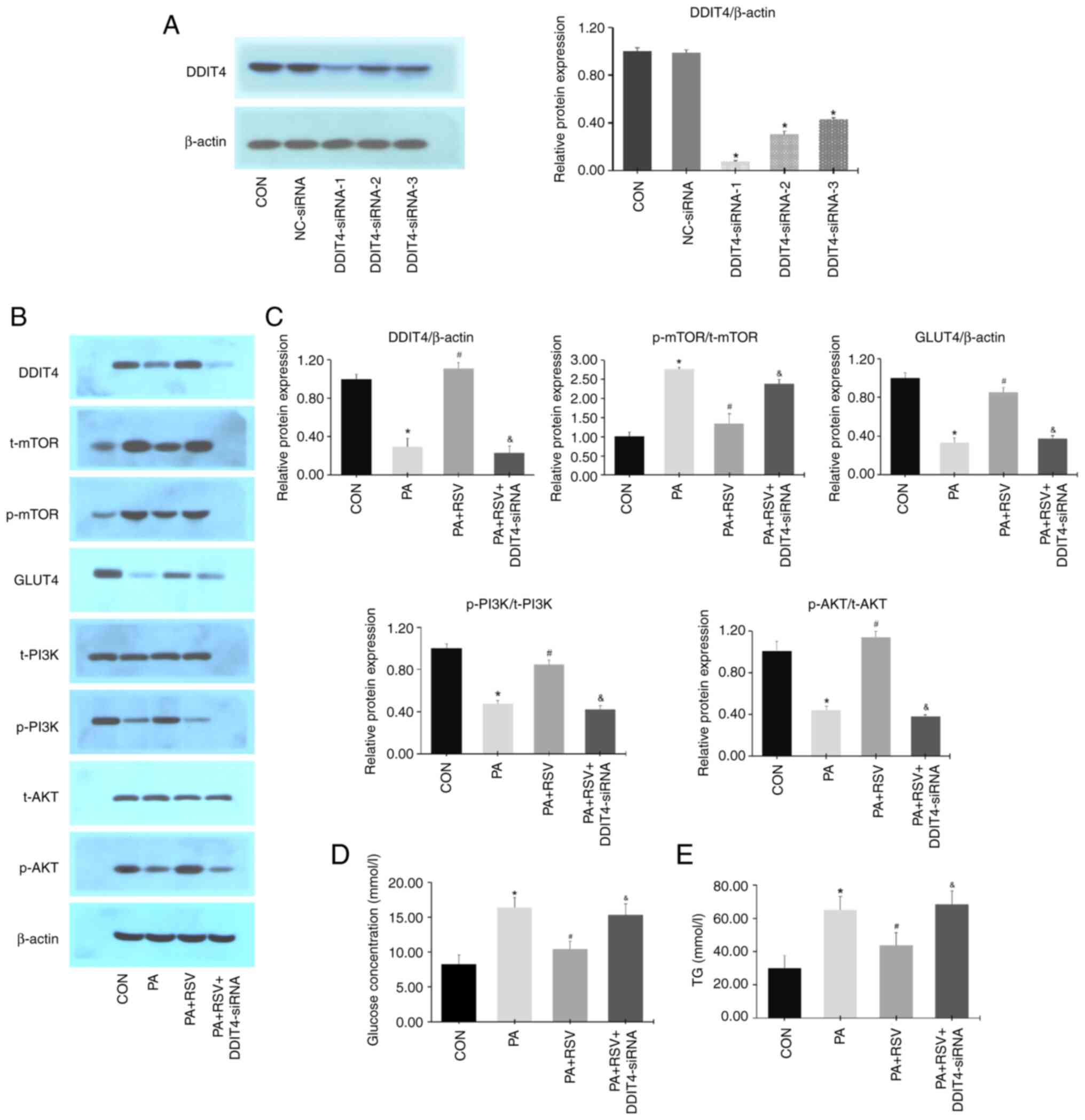

Plasmid validation experiments revealed that

DDIT4-siRNA-1 had the most significant silencing effect (Fig. 9A). The cells were then divided into

four groups: CON, PA, PA + RSV, and PA + RSV + DDIT4 siRNA

groups.

| Figure 9Expression levels of DDIT4, mTOR,

GLUT4, PI3K, and AKT in DDIT4-siRNA-treated IR C2C12 cells. (A)

DDIT4-siRNA-1 had the most significant silencing effect. (B)

Protein expression levels of DDIT4, mTOR, GLUT4, PI3K, and AKT

after DDIT4-siRNA treatment. (C) Semi-quantification of

p-protein/t-protein ratios for mTOR, PI3K, and AKT and protein

expression levels of DDIT4 and GLUT4 after DDIT4-siRNA treatment.

(D) Glucose levels in culture medium after DDIT4-siRNA treatment.

(E) TG levels of C2C12 cells after DDIT4-siRNA treatment. Data are

presented as the mean ± SD (n=3). *P<0.05 vs. the CON

group; #P<0.05 vs. the PA group;

&P<0.05 vs. the PA + RSV group. DDIT4,

DNA-damage-inducible transcript 4; mTOR, mammalian target of

rapamycin; GLUT4, glucose transporter 4; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase; AKT, protein kinase B; siRNA, small interfering RNA; IR,

insulin resistance; p-, phosphorylated; t-, total; TG,

triglyceride; CON, control; PA, palmitic acid; RSV,

resveratrol. |

Compared with the PA + RSV group, the protein

expression levels of DDIT4, p-PI3K/t-PI3K, p-AKT/t-AKT and GLUT4

were decreased, whereas those of p-mTOR/t-mTOR were increased in

the PA + RSV + DDIT4-siRNA group (Fig.

9B and C). Compared with the PA

+ RSV group, the glucose concentration in the culture medium and TG

content of the cells were increased in the PA + RSV + DDIT4-siRNA

group (Fig. 9D and E).

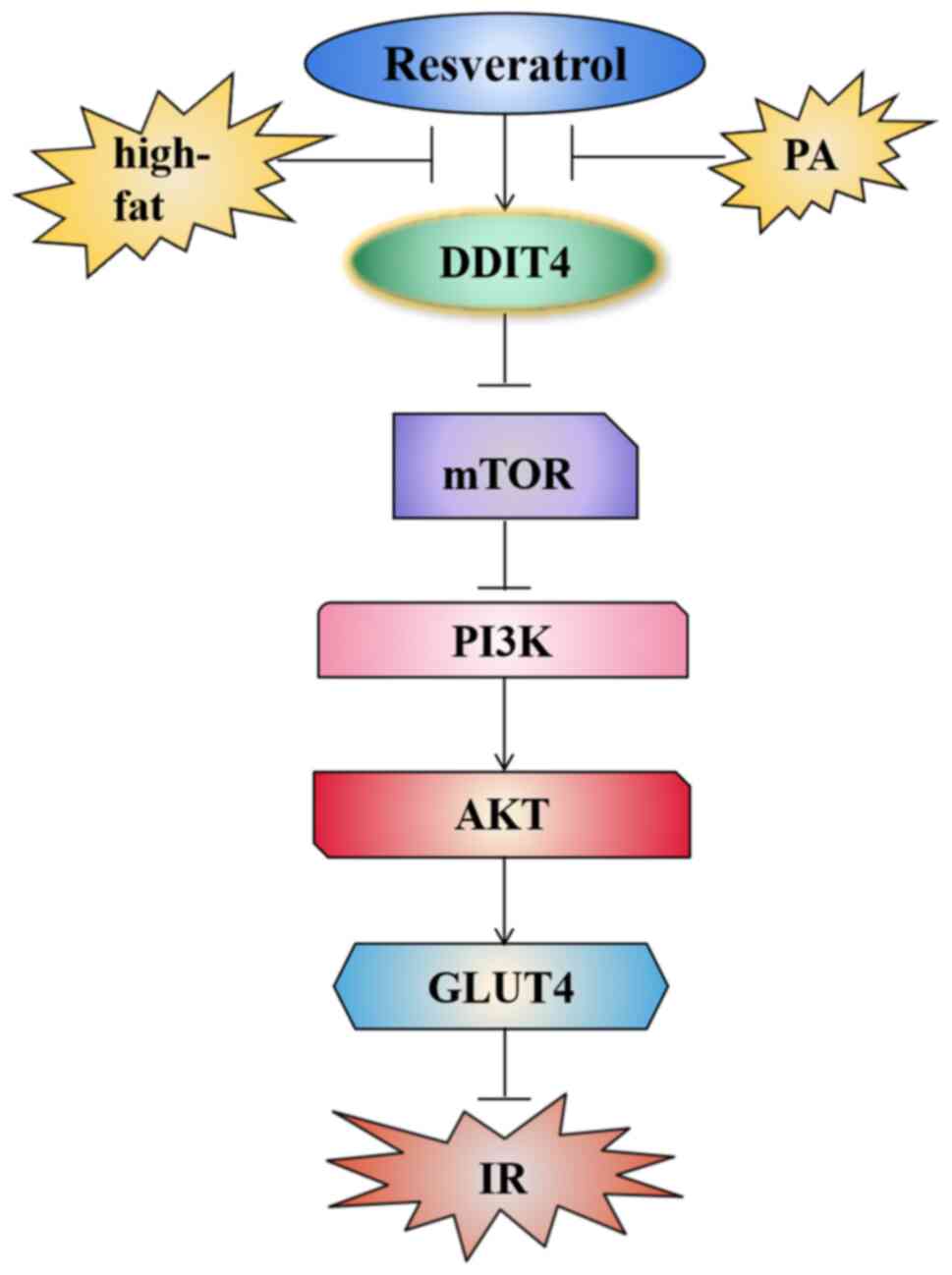

The results showed that RSV could activate DDIT4

expression, thereby inhibiting the mTOR pathway and then reducing

IR and lipid deposition in high-fat induced C2C12 cells (Fig. 10).

Discussion

In the present study, a mouse model with IR was

established by an HFD. This model closely simulated manifestations

of IR, including weight gain, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia,

impaired glucose tolerance and a low QUICKI index. In the present

study, treatment with RSV markedly reduced the concentration of

blood lipid and glucose, and decreased the AUC of IPGTT and body

weight of mice with HFD-induced IR. RSV also increased the QUICKI

index, improved the morphology and structure of skeletal muscle

tissue, and significantly reduced lipid droplet vacuoles in

skeletal muscle cells. It was determined that there was no

difference in weight loss among the groups after fasting for 12 h

with a maximum weight loss of 10.6%, which was similar to the

results found in another study (27). These results showed that RSV reduced

IR and lipid deposition in the skeletal muscle of mice fed an HFD.

Cell experiments also confirmed that PA intervention could reduce

glucose uptake and increase lipid levels in C2C12 cells. RSV could

reverse this condition, while the mTOR agonist MHY1485 or siRNA

against DDIT4 intervention further confirmed that RSV inhibited

mTOR by activating DDIT4, thereby affecting the activation of the

insulin pathway. Previous research also revealed that RSV plays a

beneficial role in glucose and lipid metabolism in animal models

and individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (28-30),

and reduced IR in various models (30,32).

To determine the molecular mechanism of the effects

of RSV, the present study examined gene and protein expression

levels of PI3K, AKT and GLUT4 in murine skeletal muscle and C2C12

cells. Biologically, insulin can combine with the insulin receptor

of peripheral target organs, such as skeletal muscle, and then

interact with IRS to activate the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway,

resulting in the downstream translocation of GLUT4 to the cell

membrane, thereby increasing glucose uptake and metabolism in

peripheral target organs (33). RSV

can increase the expression of GLUT4 in peripheral tissues by

activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, thereby increasing

tissue uptake of glucose and lowering blood glucose levels

(34,35). Similarly, the present study found

that an HFD inhibited the IRS-1/PI3K/AKT/GLUT4 insulin signaling

pathway. However, RSV partially corrected the aberrant protein

levels of PI3K, AKT and GLUT4 in mice with IR, suggesting that RSV

exerts a regulatory effect by alleviating IR in skeletal muscle

through modulation of the PI3K/AKT/GLUT4 signaling pathway.

The present study found that the mTOR pathway was

activated in mice with HFD-induced IR and in C2C12 cells with

PA-induced IR, and that the expression levels of mTOR were

increased in skeletal muscle and in C2C12 cells. The continuous

activation of the mTOR pathway has been revealed to induce lipid

deposition, leading to tissue and cell IR (36,37).

The activation of mTOR can trigger a negative feedback pathway

involving the downstream signal p70S6K, which when activated leads

to the phosphorylation of IRS-1 and promotion of the degradation of

IRS-1, thus blocking the PI3K/AKT signal transduction pathway,

leading to IR (7). The inhibition

of mTOR and p70S6K can inhibit serine phosphorylation of

IRS-1(38), restore the

insulin-mediated glucose transport of GLUT4(39), and improve insulin sensitivity and

reduce obesity in mice (40). The

present study found that RSV inhibited activation of mTOR, then

promoted the PI3K/AKT/GLUT4 insulin signaling pathway, increased

insulin sensitivity and reduced the abnormal glucose and lipid

metabolism in PA-treated C2C12 cells and mice fed an HFD.

The present study determined the expression levels

of DDIT4, which is a negative regulator of the mTOR signaling

pathway (41-43).

High expression levels of DDIT4 in rat gastrocnemius muscle cells

were demosntrated to inhibit the activity of the mTOR signaling

pathway (44). Regazzetti et

al (45) showed that silencing

DDIT4 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes induced an increase in mTOR activity,

and inhibited the insulin signaling pathway and adipogenesis in

adipocytes. Consistent with the aforementioned studies, the current

results indicated that the expression of DDIT4 was inhibited, the

expression levels of mTOR and p70S6K were increased, and the

PI3K/AKT/GLUT4 insulin pathway was inhibited in mice or C2C12 cells

with IR. Wang et al (46)

found that the expression of DDIT4 was reduced in a rat model of

diabetic nephropathy, and the administration of

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 increased DDIT4 expression and caused a

significant decrease in the phosphorylation levels of mTOR and

p70S6K, resulting in the inhibition of mesangial cell

proliferation, hypertrophy, and disordered blood glucose and lipid

metabolism (46). Notably, the

present study showed that administration of RSV to mice or cells

with IR increased the expression of DDIT4, inhibited the mTOR

pathway, activated the PI3K/AKT/GLUT4 pathway and reduced the

HFD-induced IR, and glucose and lipid metabolism disorders in

skeletal muscle and cells. Therefore, RSV may reduce IR by

regulating the DDIT4/mTOR signaling pathway.

Limited data from a human-based study revealed that

RSV improved insulin sensitivity and fasting glucose levels in

patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and may improve inflammatory

status in human obesity (28). A

meta-analysis revealed that RSV significantly improved glucose

control and insulin sensitivity in individuals with diabetes, but

did not affect glycemic levels in nondiabetic individuals (47). A randomized controlled study

revealed that RSV treatment improved inflammation, renal function,

blood glucose parameters, inflammation, IR, and nutrient sensing

systems in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus,

indicating that RSV may be a potential therapeutic drug for the

treatment of elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

(48). Another randomized

controlled study showed that natural polyphenol, RSV, represents a

potential new treatment for management of nonalcoholic fatty liver

disease due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties

(49). There is limited research on

the mechanism of RSV on IR, as well as glucose and lipid metabolism

disorders in human studies. Therefore, in the present study, the

mechanism of RSV in improving IR, as well as glucose and lipid

metabolism through animal and cell experiments was explored, which

generated data for drug preclinical research and laid a foundation

for future clinical studies.

Treatment with RSV decreased body weight, blood

glucose and lipid levels, and reduced IR in mice. It is proposed

that RSV activated the PI3K/AKT/GLUT4 signaling pathway by

regulating the DDIT4/mTOR pathway, resulting in significant

anti-hyperglycemic and anti-hyperlipidemic activities in skeletal

muscle and C2C12 cells. Therefore, RSV can potentially be used as

an effective drug for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, as well as

a nutritional supplement for the prevention of type 2 diabetes and

cardiovascular diseases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This study was partially supported by the Scientific

Research Project of Hebei Provincial Administration of Traditional

Chinese Medicine (grant no. 2023010).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XP performed the data collection and analysis and

wrote the manuscript. GX, MZ, ZX, DL and ZD performed the sample

collection and detection. CW designed the study, performed the

primary research, and supported manuscript revision. XP and CW

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved (approval no.

2023-LW-055) by the Ethics Committee of Hebei General Hospital

(Shijiazhuang, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhu X, Wu C, Qiu S, Yuan X and Li L:

Effects of resveratrol on glucose control and insulin sensitivity

in subjects with type 2 diabetes: Systematic review and

meta-analysis. Nutr Metab (Lond). 14(60)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Duan TT, Hu XB and Cao ZH: Effect of

resveratrol in treatment of diabetes mellitus. Prog Microbiol

Immunol. 48:99–103. 2020.(In Chinese).

|

|

3

|

Vlavcheski F and Tsiani E: Attenuation of

free fatty acid-induced muscle insulin resistance by rosemary

extract. Nutrients. 10(1623)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Wang L, Gao P, Zhang M, Huang Z, Zhang D,

Deng Q, Li Y, Zhao Z, Qin X, Jin D, et al: Prevalence and ethnic

pattern of diabetes and prediabetes in China in 2013. JAMA.

317:2515–2523. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Khamzina L, Veilleux A, Bergeron S and

Marette A: Increased activation of the mammalian target of

rapamycin pathway in liver and skeletal muscle of obese rats:

Possible involvement in obesity-linked insulin resistance.

Endocrinology. 146:1473–1481. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Tremblay F and Marette A: Amino acid and

insulin signaling via the mTOR/p70 S6 kinase pathway. A negative

feedback mechanism leading to insulin resistance in skeletal muscle

cells. J Biol Chem. 276:38052–38060. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Holz MK, Ballif BA, Gygi SP and Blenis J:

mTOR and S6K1 mediate assembly of the translation preinitiation

complex through dynamic protein interchange and ordered

phosphorylation events. Cell. 123:569–580. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Tinline-Goodfellow CT, Lees MJ and Hodson

N: The skeletal muscle fiber periphery: A nexus of mTOR-related

anabolism. Sports Med Health Sci. 5:10–19. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ellisen LW, Ramsayer KD, Johannessen CM,

Yang A, Beppu H, Minda K, Oliner JD, McKeon F and Haber DA: REDD1,

a developmentally regulated transcriptional target of p63 and p53,

links p63 to regulation of reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell.

10:995–1005. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Brugarolas J, Lei K, Hurley RL, Manning

BD, Reiling JH, Hafen E, Witters LA, Ellisen LW and Kaelin WG Jr:

Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the

TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev. 18:2893–2904.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Reiling JH and Hafen E: The

hypoxia-induced paralogs Scylla and Charybdis inhibit growth by

down-regulating S6K activity upstream of TSC in Drosophila. Gene

Dev. 18:2879–2892. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Wang H, Kubica N, Ellisen LW, Jefferson LS

and Kimball SR: Dexamethasone represses signaling through the

mammalian target of rapamycin in muscle cells by enhancing

expression of REDD1. J Biol Chem. 281:39128–39134. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Jin HO, Seo SK, Woo SH, Kim ES, Lee HC,

Yoo DH, An S, Choe TB, Lee SJ, Hong SI, et al: Activating

transcription factor 4 and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-beta

negatively regulate the mammalian target of rapamycin via Redd1

expression in response to oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum

stress. Free Radical Bio Med. 46:1158–1167. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Whitney ML, Jefferson LS and Kimball SR:

ATF4 is necessary and sufficient for ER stress-induced upregulation

of REDD1 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 379:451–455.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

McGhee NK, Jefferson LS and Kimball SR:

Elevated corticosterone associated with food deprivation

upregulates expression in rat skeletal muscle of the mTORC1

repressor, REDD1. J Nutr. 139:828–834. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Dennis MD, Coleman CS, Berg A, Jefferson

LS and Kimball SR: REDD1 enhances protein phosphatase 2A-mediated

dephosphorylation of Akt to repress mTORC1 signaling. Sci Signal.

7(ra68)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Williamson DL, Li Z, Tuder RM, Feinstein

E, Kimball SR and Dungan CM: Altered nutrient response of mTORC1 as

a result of changes in REDD1 expression: Effect of obesity vs REDD1

deficiency. J Appl Physiol (1985). 117:246–256. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Gordon BS, Steiner JL, Williamson DL, Lang

CH and Kimball SR: Emerging role for regulated in development and

DNA damage 1 (REDD1) in the regulation of skeletal muscle

metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 311:E157–E174.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Zhang ZM, Liu ZH, Nie Q, Zhang XM, Yang

LQ, Wang C, Yang LL and Song GY: Metformin improves high-fat

diet-induced insulin resistance in mice by downregulating the

expression of long noncoding RNA NONMMUT031874.2. Exp Ther Med.

23(332)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ayala JE, Samuel VT, Morton GJ, Obici S,

Croniger CM, Shulman GI, Wasserman DH and McGuinness OP: NIH Mouse

Metabolic Phenotyping Center Consortium. Standard operating

procedures for describing and performing metabolic tests of glucose

homeostasis in mice. Dis Model Mech. 3:525–534. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Bowe JE, Franklin ZJ, Hauge-Evans AC, King

AJ, Persaud SJ and Jones PM: Metabolic phenotyping guidelines:

Assessing glucose homeostasis in rodent models. J Endocrinol.

222:G13–G25. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Benedé-Ubieto R, Estévez-Vázquez O,

Ramadori P, Cubero FJ and Nevzorova YA: Guidelines and

considerations for metabolic tolerance tests in mice. Diabetes

Metab Syndr Obes. 13:439–450. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Jørgensen MS, Tornqvist KS and Hvid H:

Calculation of glucose dose for intraperitoneal glucose tolerance

tests in lean and obese mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 56:95–97.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Shu L, Hou G, Zhao H, Huang W, Song G and

Ma H: Resveratrol improves high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance

in mice by downregulating the lncRNA NONMMUT008655.2. Am J Transl

Res. 12:1–18. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Katz A, Nambi SS, Mather K, Baron AD,

Follmann DA, Sullivan G and Quon MJ: Quantitative insulin

sensitivity check index: A simple, accurate method for assessing

insulin sensitivity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

85:2402–2410. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Jensen TL, Kiersgaard MK, Sørensen DB and

Mikkelsen LF: Fasting of mice: A review. Lab Anim. 47:225–240.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Barber TM, Kabisch S, Randeva HS, Pfeiffer

AFH and Weickert MO: Implications of resveratrol in obesity and

insulin resistance: A state-of-the-art review. Nutrients.

14(2870)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Luo J, Chen S, Wang L, Zhao X and Piao C:

Pharmacological effects of polydatin in the treatment of metabolic

diseases: A review. Phytomedicine. 102(154161)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ariyanto EF, Danil AS, Rohmawaty E,

Sujatmiko B and Berbudi A: Effect of resveratrol in melinjo seed

(Gnetum gnemon L.) extract on type 2 diabetes mellitus patients and

its possible mechanism: A review. Curr Diabetes Rev.

19(e280222201512)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Shahwan M, Alhumaydhi F, Ashraf GM, Hasan

PMZ and Shamsi A: Role of polyphenols in combating type 2 diabetes

and insulin resistance. Int J Biol Macromol. 206:567–579.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Zhou Q, Wang Y, Han X, Fu S, Zhu C and

Chen Q: Efficacy of resveratrol supplementation on glucose and

lipid metabolism: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Front

Physiol. 13(795980)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Chadt A and Al-Hasani H: Glucose

transporters in adipose tissue, liver, and skeletal muscle in

metabolic health and disease. Pflugers Arch. 472:1273–1298.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Vlavcheski F, Den Hartogh DJ, Giacca A and

Tsiani E: Amelioration of high-insulin-induced skeletal muscle cell

insulin resistance by resveratrol is linked to activation of AMPK

and restoration of GLUT4 translocation. Nutrients.

12(914)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kang BB and Chiang BH: A novel phenolic

formulation for treating hepatic and peripheral insulin resistance

by regulating GLUT4-mediated glucose uptake. J Tradit Complement

Med. 12:195–205. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Bar-Tana J: Type 2 diabetes-unmet need,

unresolved pathogenesis, mTORC1-centric paradigm. Rev Endocr Metab

Dis. 21:613–629. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Bodur C, Kazyken D, Huang K, Tooley AS,

Cho KW, Barnes TM, Lumeng CN, Myers MG and Fingar DC: TBK1-mTOR

signaling attenuates obesity-linked hyperglycemia and insulin

resistance. Diabetes. 71:2297–2312. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Huang SL, Xie W, Ye YL, Liu J, Qu H, Shen

Y, Xu TF, Zhao ZH, Shi Y, Shen JH and Leng Y: Coronarin A modulated

hepatic glycogen synthesis and gluconeogenesis via inhibiting

mTORC1/S6K1 signaling and ameliorated glucose homeostasis of

diabetic mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 44:596–609. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Den Hartogh DJ, Vlavcheski F, Giacca A and

Tsiani E: Attenuation of free fatty acid (FFA)-induced skeletal

muscle cell insulin resistance by resveratrol is linked to

activation of AMPK and inhibition of mTOR and p70S6K. Int J Mol

Sci. 21(4900)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Meng W, Liang X, Chen H, Luo H, Bai J, Li

G, Zhang Q, Xiao T, He S, Zhang Y, et al: Rheb inhibits beiging of

white adipose tissue via PDE4D5-dependent down regulation of the

cAMP-PKA signaling pathway. Diabetes. 66:1198–1213. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Dungan CM and Williamson DL: Regulation of

skeletal muscle insulin-stimulated signaling through the

MEK-REDD1-mTOR axis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 482:1067–1072.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Lee Y, Song MJ, Park JH, Shin MH, Kim MK,

Hwang D, Lee DH and Chung JH: Histone deacetylase 4 reverses

cellular senescence via DDIT4 in dermal fibroblasts. Aging (Albany

NY). 14:4653–4672. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhidkova EM, Lylova ES, Grigoreva DD,

Kirsanov KI, Osipova AV, Kulikov EP, Mertsalov SA, Belitsky GA,

Budunova I, Yakubovskaya MG and Lesovaya EA: Nutritional sensor

REDD1 in cancer and inflammation: Friend or foe? Int J Mol Sci.

23(9686)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Murakami T, Hasegawa K and Yoshinaga M:

Rapid induction of REDD1 expression by endurance exercise in rat

skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 405:615–619.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Regazzetti C, Dumas K, Le Marchand-Brustel

Y, Peraldi P, Tanti JF and Giorgetti-Peraldi S: Regulated in

development and DNA damage responses-1 (REDD1) protein contributes

to insulin signaling pathway in adipocytes. PLoS One.

7(e52154)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Wang H, Wang J, Qu H, Wei H, Ji B, Yang Z,

Wu J, He Q, Luo Y, Liu D, et al: In vitro and in vivo inhibition of

mTOR by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 to improve early diabetic

nephropathy via the DDIT4/TSC2/mTOR pathway. Endocrine. 54:348–359.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Delpino FM and Figueiredo LM: Resveratrol

supplementation and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 62:4465–4480.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Ma N and Zhang Y: Effects of resveratrol

therapy on glucose metabolism, insulin resistance, inflammation,

and renal function in the elderly patients with type 2 diabetes

mellitus: A randomized controlled clinical trial protocol. Medicine

(Baltimore). 101(e30049)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Karimi M, Abiri B, Guest PC and Vafa M:

Therapeutic effects of resveratrol on nonalcoholic fatty liver

disease through inflammatory, oxidative stress, metabolic, and

epigenetic modifications. Methods Mol Biol. 2343:19–35.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|