Introduction

Bronchial asthma, a long-standing ailment, is a

prevalent respiratory disease that affects individuals of all ages

globally (1). Patients with chronic

persistent bronchial asthma frequently experience recurrent

episodes, significantly disrupting their daily life and work

(2). It is estimated that bronchial

asthma affects ~300 million people worldwide, a number projected to

rise to 400 million by 2025(3).

Bronchial asthma is responsible for ~500,000 hospitalizations

annually, with ~250,000 deaths attributed to the disease each year

(4). Bronchial asthma is

distinguished by varying degrees of persistent inflammation and

structural modifications in the airway (5). The most notable abnormalities include

epithelial denudation, goblet cell metaplasia, subepithelial

thickening, augmented airway smooth muscle mass, bronchial gland

enlargement, angiogenesis, and modifications in extracellular

matrix components, involving both large and small airways (6).

Alpha coronaviruses, including human coronavirus

229E (HCoV-229E) and HCoV-NL63, induce inflammation in the upper

respiratory tract and have the potential to exacerbate asthma

(7). Conversely,

bate-coronaviruses, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome-CoV-2

(SARS-CoV-2), SARS-CoV, and Middle East respiratory syndrome-CoV

(MERS-CoV), specifically target epithelial cells in both the upper

and lower airways. SARS-CoV-2 serves as the causative agent for the

disease known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (8). The COVID-19 pandemic originated in

Wuhan, China, and rapidly spread worldwide. The COVID-19 pandemic,

caused by the SARS-CoV-2, has emerged as a remarkable global health

concern (9). COVID-19 manifests in

distinct stages following a median incubation period of 5 days,

involving mild cases (80-90% of patients) characterized by upper

and lower airway responses, while severe cases (10-20%) progress to

bilateral pneumonia (10). A subset

of patients with severe COVID-19 may develop acute respiratory

distress syndrome, necessitating mechanical ventilation in an

intensive care setting (11). With

an estimated 300 million people globally affected by asthma

(12), understanding the clinical

characteristics of COVID-19-induced bronchial asthma is vital.

Notably, patients with pre-existing comorbidities, such as diabetes

and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, are more prone to

experience severe manifestations of COVID-19(13). While there exists a potential

heightened risk of severe COVID-19 in asthmatic patients, it is

uncertain whether COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial asthma has

its own unique clinical characteristics. The present study examined

the medical history and clinical features of patients with COVID-19

infection-induced bronchial asthma, as well as those with typical

bronchial asthma who were diagnosed and treated in our hospital. A

comparative analysis was conducted to identify differences between

these two groups of asthmatic patients.

Materials and methods

Patients

The clinical data of 116 patients with COVID-19

infection-induced bronchial asthma, who were diagnosed and treated

in the outpatient department of Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital

(Beijing, China) after the COVID-19 pandemic (post-March 2023),

were retrospectively analyzed. Additionally, data from 113 patients

with typical bronchial asthma (no history of COVID-19 infection),

who were diagnosed and treated before the pandemic (January 2022 to

November 2022), were included for comparable analysis.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: patients who

meet the GINA 2023 diagnostic criteria (https://ginasthma.org/2023-gina-main-report/) for

bronchial asthma and were initially diagnosed with bronchial

asthma; patients who aged between 18 and 75 years old; patients

with no obvious abnormalities on chest X-ray or computed tomography

(CT) examination.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: Patients with

other respiratory diseases, such as lung infection and

bronchiectasis; patients with severe diseases of other systems,

including autoimmune diseases, myocardial infarction, heart

failure, and malignant tumors; pregnant or lactating women.

Methods

The present study collected the medical history and

clinical characteristics of patients with bronchial asthma induced

by COVID-19 infection and patients with typical bronchial asthma

who were diagnosed and treated in our hospital. The time from the

onset of clinical manifestations of asthma to its diagnosis was

recorded. Additionally, routine blood test results, serum total IgE

levels, specific IgE levels, lung function, airway provocation test

results, fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) levels, and other

relevant information were collected. The differences between the

two groups of asthmatic patients were then compared and analyzed.

While the study concentrated on comparing clinical characteristics

and pulmonary function, the treatment methods for both outpatient

care and acute asthma control were standardized according to the

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2023 guidelines. All

patients received treatment based on these guidelines, ensuring

consistency in managing asthma symptoms. However, individualized

adjustments in therapy might occur, especially in outpatient

settings, which could introduce variability in the results. Future

studies should provide more detailed descriptions of the specific

treatment regimens used to assess their potential influence on

clinical outcomes and pulmonary function, thereby improving the

consistency and reproducibility of findings.

Pulmonary function tests

Once the acute phase of asthma attack was

controlled, pulmonary function tests were completed in both groups,

including pulmonary ventilation, pulmonary reserve function, small

airway function, diffusion function, carbon monoxide dispersion to

alveolar volume ratio, and residual volume/total lung capacity

(RV/TLC). Pulmonary ventilation tests included forced expiratory

volume in 1 sec as a percentage of the predicted value (FEV1%),

forced expiratory volume in 1 sec to forced vital capacity ratio

(FEV1/FVC), and peak expiratory flow (PEF). Maximal voluntary

ventilation (MVV) was assessed to evaluate pulmonary reserve

function. Small airway function tests included the maximal

expiratory flow rates at 75, 50 and 25% of lung capacity (MEF75,

MEF50 and MEF25) and the maximal mid-expiratory flow rate

(MMEF75/25). Diffusion function tests included the single-breath

diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO SB) and DLCO normalized

for alveolar volume (DLCO/VA).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp.) and GraphPad 9.0 (GraphPad

Software Inc.; Dotmatics) software were used to statistically

analyze the data. The measurement data of normal distribution were

expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (X ± s), and analyzed

using independent sample t-test. The measurement data of skewed

distribution were expressed as the median (quartile), and analyzed

via Mann-Whitney U test. The rates were compared using the χ² test.

The Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to identify the

factors associated with poor pulmonary function in the COVID-19

group. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Patients' clinical

characteristics

The range of age in the COVID-19 infection-induced

bronchial asthma group was 21.9-74.7 years old, with an average age

of 46.9±14.0 years. Among them, there were 69 women and 44 men,

with a female-to-male ratio of 1.57. In the general bronchial

asthma group, 7 (6.0%) cases had a history of allergy, including

inhalation, food, drugs, 51 (44.0%) cases had allergic rhinitis, 12

(10.3%) cases had eczema, and 7 (6.0%) cases had chronic Hives. The

range of age in the general bronchial asthma group was 21-77 years

old, with an average age of 44.5±14.7 years old. Among them, there

were 64 women and 30 men, with a female-to-male ratio of 2.13. In

the COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial asthma group, there were 7

(7.4%) cases with allergic history, 37 (39.4%) cases with allergic

rhinitis, 9 (9.6%) cases with Nasal polyp, 10 (10.6%) cases with

eczema, and 3 (3.2%) cases with chronic Hives (Table I).

| Table IGeneral data of the two groups. |

Table I

General data of the two groups.

| | COVID-19 asthma

(116) | Asthma (113) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 46.9±1.8 | 42.3±1.6 | >0.05 |

| Sex, female (%) | 75 (64.7) | 69 (61.1) | >0.05 |

| History of allergy

(%) | 7(6) | 4 (3.5) | >0.05 |

| Allergic Rhinitis

(%) | 51(44) | 52(46) | >0.05 |

| Nasal polyps (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | >0.05 |

| Eczema (%) | 12 (10.3) | 17(15) | >0.05 |

| Urticaria (%) | 7(6) | 4 (3.5) | >0.05 |

The duration of disease was 3.371±0.11 months in the

COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial asthma group and 3.327±0.17

months in the general bronchial asthma group, and there was no

significant difference between the two groups (P>0.05).

Patients' main clinical characteristics were cough, sputum, chest

tightness, dyspnea and wheezing. There was no significant

difference in patients' main clinical characteristics between the

two groups (P>0.05) (Table

II).

| Table IIClinical symptoms of the two

groups. |

Table II

Clinical symptoms of the two

groups.

| | COVID-19 asthma

(116) | Asthma (113) | P-value |

|---|

| Duration, months | 3.371±0.11 | 3.327±0.17 | >0.05 |

| Cough (%) | 85 (73.3) | 80 (70.8) | >0.05 |

| Sputum (%) | 13 (11.2) | 12 (10.6) | >0.05 |

| Chest tightness

(%) | 35 (27.6) | 43 (38.1) | >0.05 |

| Dyspnea (%) | 35 (30.2) | 28 (24.8) | >0.05 |

| Wheezing (%) | 3 (2.6) | 5 (4.4) | >0.05 |

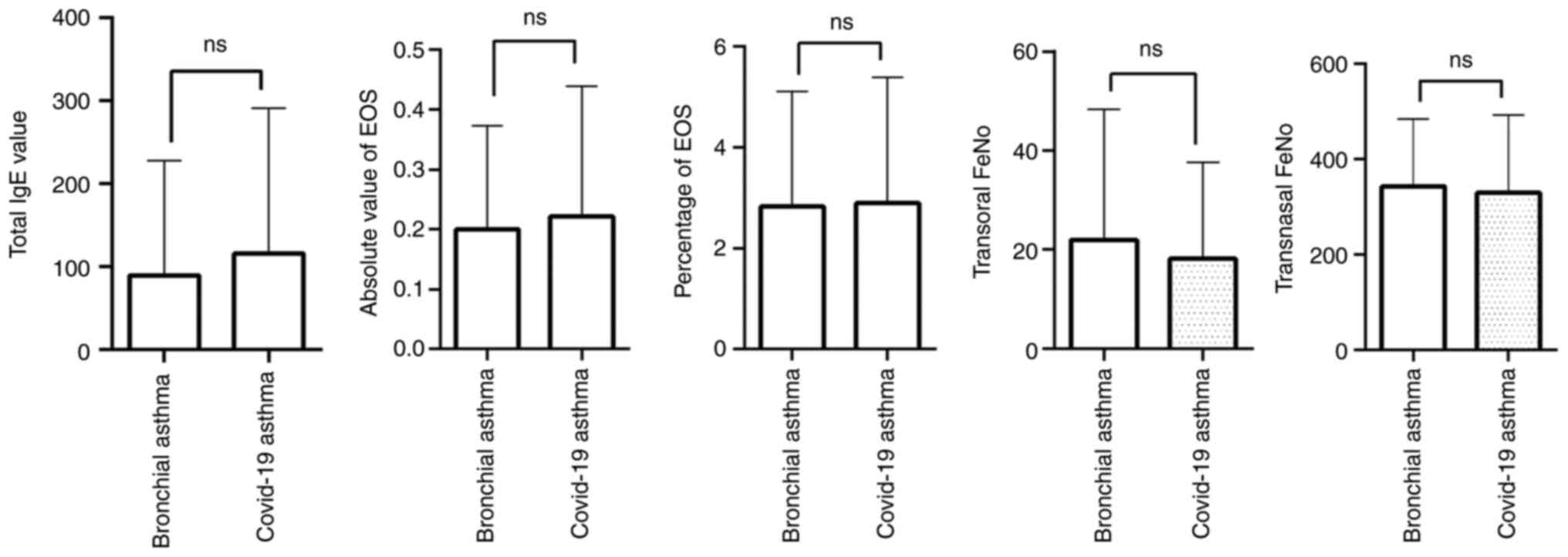

Comparison of inflammatory reaction

between the two groups

Patients with COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial

asthma and patients with common bronchial asthma all received

routine peripheral blood tests. The results indicated no

significant differences in total IgE levels, the absolute value and

percentage of eosinophils (EOS), transoral FeNO, or transnasal FeNO

in the peripheral blood between the COVID-19 infection-induced

bronchial asthma group and the normal bronchial asthma group

(P>0.05) (Table III, Fig. 1).

| Table IIIComparison of pulmonary function

indexes between COVID-19 asthma and asthma groups. |

Table III

Comparison of pulmonary function

indexes between COVID-19 asthma and asthma groups.

| Indicator | Asthma (113) | COVID-19 asthma

(116) | P-value |

|---|

| Vcmax | 96.7±1.40 | 100.1±1.17 | 0.068 |

| FVC | 98.1±1.40 | 101.9±1.23 | 0.071 |

| FEV1% | 93.7±1.37 | 97.6±1.10 | 0.026 |

| FEV1/FVC | 81.4±0.67 | 80.36±0.77 | 0.293 |

| PEF | 99.0±1.58 | 92.1±1.67 | 0.003 |

| MEF75 | 97.4±1.98 | 89.7±2.14 | 0.009 |

| MEF50 | 81.5±2.13 | 76.4±2.48 | 0.121 |

| MEF25 | 71.0±5.54 | 62.8±2.80 | 0.180 |

| MMEF75/25 | 75.2±2.07 | 71.1±2.45 | 0.196 |

| MVV | 83.1±1.48 | 77.8±1.65 | 0.018 |

| FEV1*30 | 78.9±0.93 | 74.8±1.33 | 0.012 |

| DLCO SB | 85.4±1.39 | 87.3±1.59 | 0.372 |

| DLCO/VA | 91.5±1.65 | 92.9±1.85 | 0.571 |

| VA | 97.4±1.53 | 96.5±1.71 | 0.691 |

| R tot | 130.9±5.23 | 132.6±4.06 | 0.794 |

| RV | 105.4±2.57 | 117.2±4.42 | 0.026 |

| TLC | 96.4±1.12 | 96.9±2.02 | 0.842 |

| RV/TLC | 38.5±0.83 | 42.5±1.45 | 0.008 |

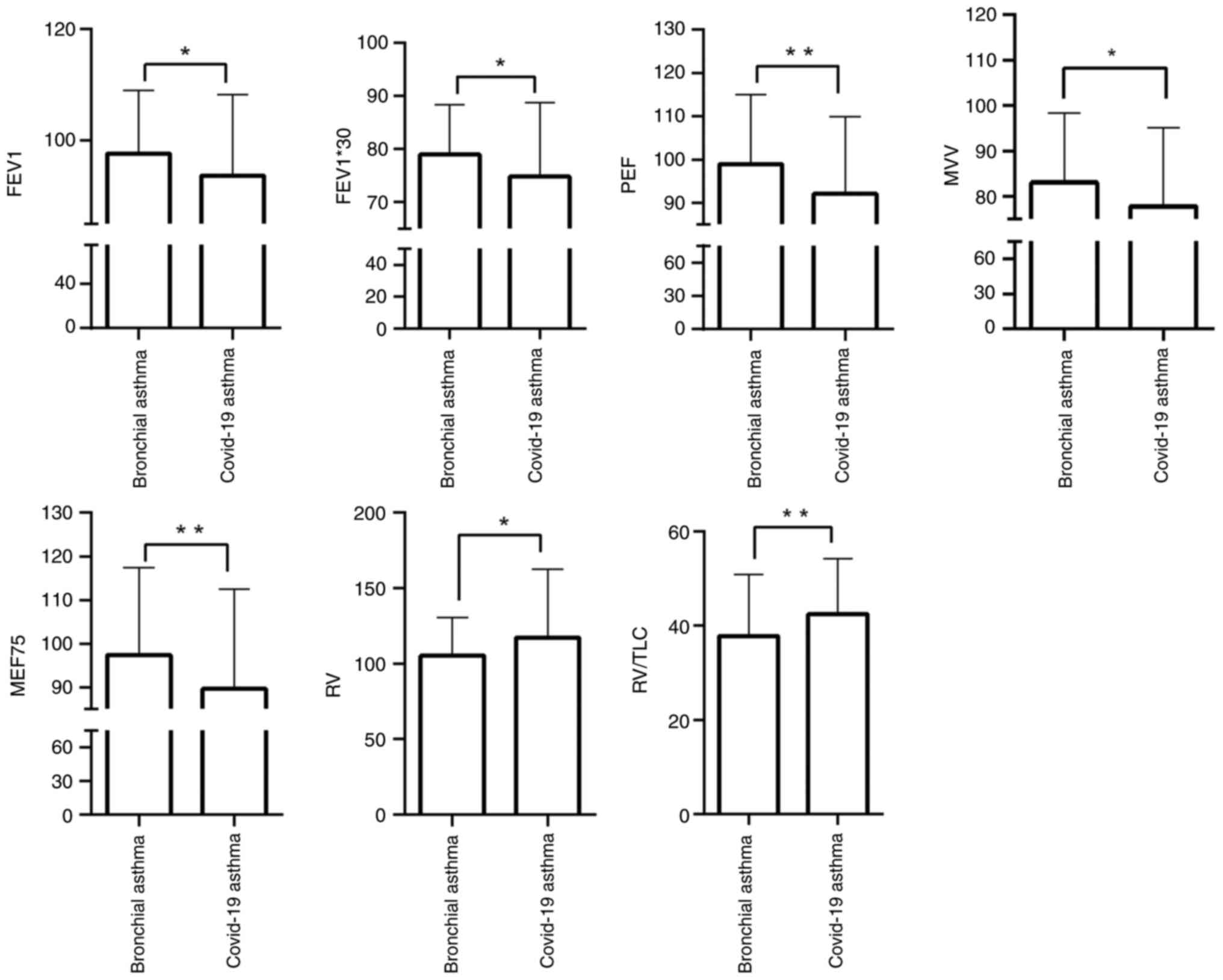

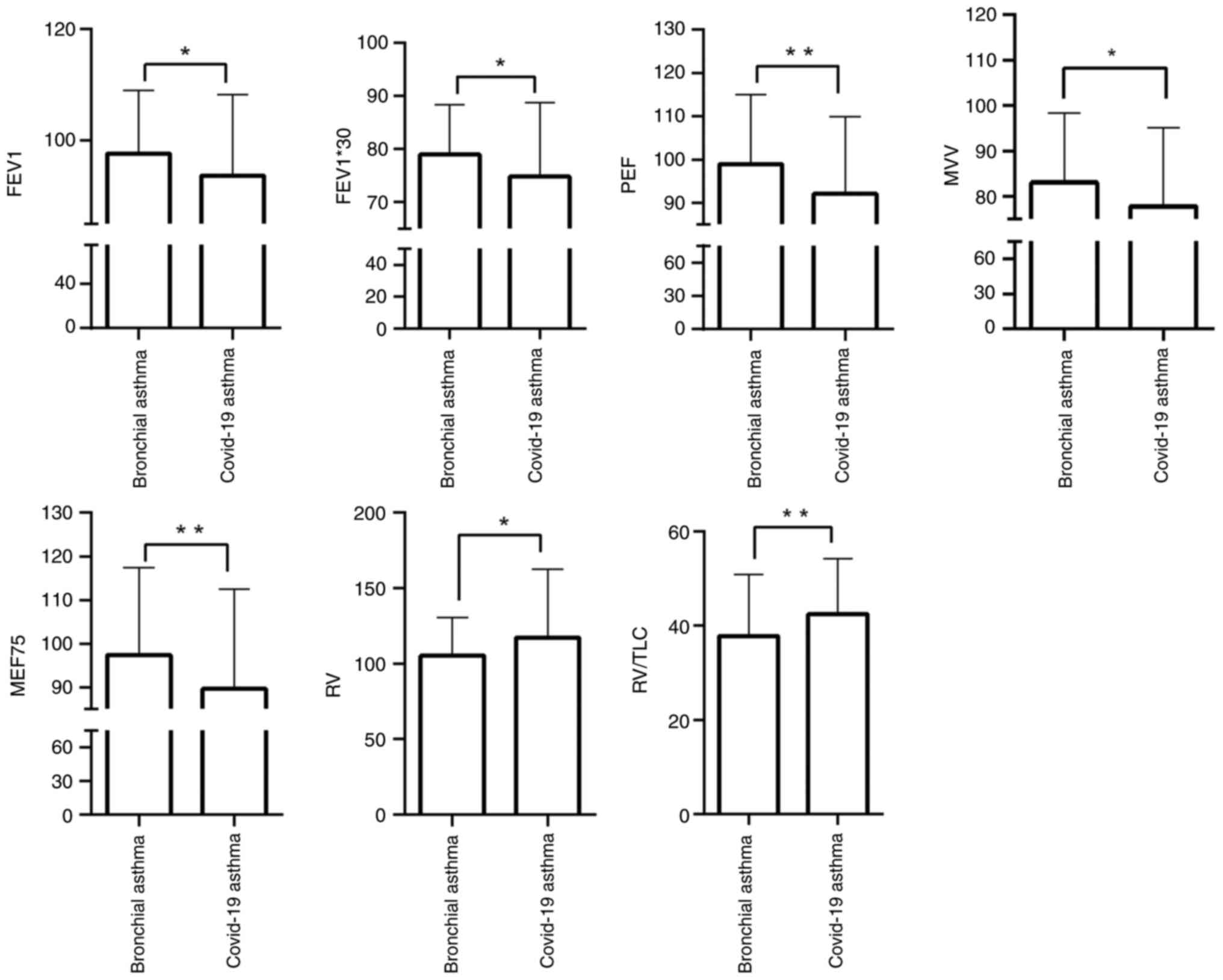

Comparison of pulmonary function

between the two groups

Pulmonary ventilation, pulmonary reserve function,

small airway function and diffusion function were evaluated between

the COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial asthma and typical

bronchial asthma groups. The pulmonary ventilation test indices,

such as FEV1%, FEV1*30, and PEF were significantly lower in the

COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial asthma group compared with the

typical bronchial asthma group (P<0.05). The MVV index was also

lower in the COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial asthma group

(P<0.05). Among the small airway function test indices, MEF75

was reduced in the COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial asthma

group (P<0.05). Additionally, RV and RV/TLC values were lower in

the COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial asthma group (P<0.05,

Table III, Fig. 2). However, no significant

differences were identified in the overall rates of impairment in

ventilation function, reserve function, small airway function,

diffusion function, airway resistance, or the ratio of residual

volume to total lung capacity (Table

IV). These findings suggested that patients with COVID-19

infection-induced bronchial asthma exhibited comparatively reduced

pulmonary function compared with those with bronchial asthma.

However, this difference was not considered clinically

significant.

| Figure 2Comparison of pulmonary function

between patients with COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial asthma

and patients with typical bronchial asthma. FEV1 (FEV1/pred),

FEV1*30 (l/min), PEF (PEF/pred), MEF75 (MEF75/pred) and MVV

(MVV/pred) were higher in the COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial

asthma group than the typical bronchial asthma group, while RV

(RV-pred) and RV/TLC (%) were lower in the COVID-19

infection-induced bronchial asthma group than the typical bronchial

asthma group. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01.

FEV1%, forced expiratory volume in 1 sec as a percentage of the

predicted value; MEF, maximal expiratory flow rate; RV, residual

volume; MVV, maximal voluntary ventilation; TLC, total lung

capacity; PEF, peak expiratory flow. |

| Table IVComparison of pulmonary function

between COVID-19 asthma and asthma groups. |

Table IV

Comparison of pulmonary function

between COVID-19 asthma and asthma groups.

| Indicator | Asthma (113)

(%) | COVID-19 asthma

(116) (%) | P-value |

|---|

| Impairment of

ventilatory function | 27 (23.9) | 34 (29.3) | 0.41 |

| Impairment of

reserve function | | | 0.37 |

| Mildly

impaired | 36 (31.9) | 36 (31.0) | |

| Moderately

impaired | 8 (7.1) | 17 (14.7) | |

| Impairment of small

airway function | | | 0.50 |

| Mildly

impaired | 37 (32.7) | 27(23.3) | |

| Moderately/severely

impaired | 8 (7.1) | 25(21.6) | |

| Impairment of

diffusion function | 42 (37.2) | 37 (31.9) | 0.49 |

| Increased airway

resistance | 42 (37.2) | 48(41.4) | 0.57 |

| Increased ratio of

residual volume to total lung capacity | 51 (45.1) | 54 (46.6) | 0.83 |

The factors related to poor pulmonary

function in the COVID-19 group

The Pearson correlation analysis was performed to

detect the factors related to poor pulmonary function in the

COVID-19 group. Patients were divided into two groups according to

the median age of 45 years old. Pearson correlation analysis

indicated that age was negatively correlated with MVV and FEV1*30

in the COVID-19 group (P<0.05), suggesting that the decline in

pulmonary function was associated with advancing age. Moreover, sex

was correlated with pulmonary function indices, including FEV1%,

MEF75, MVV, FEV1*30, and RV/TLC in the COVID-19 group (P<0.05),

indicating that male patients' pulmonary function is comparatively

inferior to that of female patients. However, the other indices,

such as allergic rhinitis, cough, expectoration, chest, dyspnea and

stridor, exhibited no correlation with pulmonary function in the

COVID-19 group (P>0.05) (Table

V).

| Table VFactors related to poor lug functions

in COVID-19 group. |

Table V

Factors related to poor lug functions

in COVID-19 group.

| Index | FEV1% | PEF | MEF75 | MVV | FEV1*30 | RV | RV/TLC | |

|---|

| Age (median age, 45

years) | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | -0.255 | -0.301 | | | Correlation

coefficient |

| | 0.827 | 0.670 | 0.710 | 0.007a | 0.001a | 0.944 |

<0.001a | P-value |

| Sex (Male 41,

Female 75) | | | | | | | | |

| | -0.241 | | -0.263 | -0.197 | | | -0.265 | Correlation

coefficient |

| | 0.010a | 0.300 | 0.005a | 0.040a | 0.697 | 0.422 | 0.006a | P-value |

| Allergic

Rhinitis | 0.892 | 0.272 | 0.356 | 0.889 | 0.656 | 0.402 | 0.917 | P-value |

| Cough | 0.904 | 0.172 | 0.345 | 0.972 | 0.810 | 0.278 | 0.501 | P-value |

| Sputum | 0.934 | 0.266 | 0.305 | 0.509 | 0.470 | 0.339 | 0.822 | P-value |

| Chest

tightness | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.771 | 0.462 | 0.756 | 0.188 | 0.507 | P-value |

| Dyspnea | 0.200 | 0.397 | 0.238 | 0.411 | 0.981 | 0.903 | 0.178 | P-value |

| Wheezing | 0.660 | 0.280 | 0.302 | 0.676 | 0.857 | 0.624 | 0.459 | P-value |

Discussion

The present study retrospectively analyzed 116 cases

of COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial asthma and 113 cases of

typical bronchial asthma. There was no significant difference

between the two groups in terms of age, sex ratio, history of

allergy, history of allergic rhinitis, history of nasal polyp,

history of eczema, and history of chronic Hives. There was no

significant difference in IgE, EOS, EOS percentage, oral FeNO, and

nasal FeNO between the two groups. The pulmonary function of

patients with COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial asthma appeared

worse than that of patients with typical bronchial asthma.

The pathophysiological changes in bronchial asthma

are mainly driven by airway smooth muscle spasms resulting from

inflammation of the airway walls. This leads to recurrent symptoms,

such as wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness and coughing

(14,15). In late 2019, COVID-19 outbreak,

caused by SARS-CoV-2, rapidly evolved into a global pandemic,

resulting in millions of fatalities (16). Patients diagnosed with bronchial

asthma are subjected to additional stressors due to the potential

development of COVID-19 and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on

societal and health-related services. Although clinical trials for

safe and efficacious antiviral agents are ongoing and vaccine

development programs have been accelerated, the long-term effects

of SARS-CoV-2 infection are becoming increasingly recognized

(17). The COVID-19 pandemic has

imposed remarkable challenges to the routine management and

diagnosis of bronchial asthma, including reduced face-to-face

consultations, limitations in conducting spirometry, and

restrictions on traditional pulmonary rehabilitation and home care

programs (18).

Eosinophil inflammation is a significant factor in

the pathogenesis of asthma. The parameters used to assess

eosinophilic inflammation include the absolute count and percentage

of EOS, total IgE level in the bloodstream, transoral FeNO, and

trans-nasal FeNO. These parameters are essential diagnostic

indicators for asthma and are also valuable for evaluating the

degree of inflammation control in asthmatic patients (19-21).

The present study found no significant differences in the absolute

count and percentage of EOS, IgE level, transoral FeNO, and

trans-nasal FeNO between the two groups, suggesting comparable

levels of eosinophilic inflammation. In allergic asthma,

eosinophilic inflammation is generally positively correlated with

the degree of pulmonary dysfunction (22,23),

demonstrating that higher levels of eosinophilic inflammation are

mainly associated with more severe pulmonary function deficits.

Pulmonary function is a fundamental measure for

evaluating asthma (24,25). The small airway, typically defined

as having a diameter of ≤2 mm, is a critical site for the early

development of several pulmonary diseases (26). In asthma, inflammation of the small

airway wall can lead to significant airway smooth muscle

contraction, resulting in recurrent symptoms, such as wheezing,

dyspnea, chest tightness and cough (27-29).

Despite the substantial cumulative cross-sectional area of small

airways, their resistance accounts for <20% of total airway

resistance (30). Traditional

pulmonary function tests mainly fail to detect abnormalities in

small airways, whereas specialized small airway function tests are

more sensitive in identifying early pathological changes (31). The emergence of COVID-19 has

presented unique challenges for patients with bronchial asthma, and

studies suggested potential interactions between the virus and

asthma pathophysiology, including small airway function and

systemic inflammation (16-18).

However, direct comparisons between COVID-19-induced bronchial

asthma and typical asthma remain scarce, particularly concerning

pulmonary dysfunction. Previous studies have highlighted the

importance of assessing small airway function as an early marker

for pulmonary diseases (26,31).

Previous research (32) has found

no significant impact of COVID-19 on asthma in children, while

studies on adult populations suggest variable outcomes, including

exacerbations and prolonged symptoms (33,34).

These findings underscore the need for further exploration of

pulmonary function in adult patients with COVID-19-induced

bronchial asthma. Eosinophilic inflammation, a hallmark of asthma

pathogenesis, has been extensively studied, and parameters, such as

total IgE, FeNO and eosinophil count served as diagnostic and

prognostic markers (19-21).

Although the findings indicated no significant differences in these

markers between the two groups, scholars (22,23)

suggested that variations in eosinophilic inflammation may

influence asthma severity, warranting further investigation in the

context of COVID-19. The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted

traditional asthma management practices, including diagnostic

procedures and treatment adherence, potentially altering disease

trajectories (17,18).

In a study by Tosca et al (32), COVID-19 was found to have no

significant impact on pulmonary function or asthma control in

children. By contrast, isolated reports in adults have described

asthma exacerbations associated with COVID-19, although such events

are not prevalent in the general population (33,34).

The current analysis suggested a potential link between COVID-19

and asthma, particularly concerning pulmonary function (35). The present study identified

significant differences in key pulmonary function parameters,

comprising FEV1, RV/TLC, PEF, MEF75, MVV, FEV1*30 and RV, between

the two groups. These results indicated that patients with COVID-19

infection-induced bronchial asthma exhibited reduced pulmonary

function compared with those with typical bronchial asthma. While

no statistically significant differences were identified in the

overall rates of ventilation function impairment, reserve function

impairment, or small airway function impairment, the findings

suggest that patients with COVID-19-induced bronchial asthma may

have subclinical lesions contributing to distinct clinical features

compared with those with non-COVID-19-induced bronchial asthma. It

is noteworthy that the present study included only non-critically

ill patients receiving outpatient treatment. As a result,

variations in the completion of diagnostic tests among patients led

to inconsistencies in the statistical analysis of certain

indicators. The Pearson correlation analysis revealed that both age

and sex were significantly associated with poorer pulmonary

function in the COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial asthma group.

However, these findings require further investigation to determine

how these factors interact with COVID-19 infection and whether they

have a more notable impact on pulmonary function over time.

Although the present study identified differences in specific

pulmonary function tests, such as FEV1%, MEF75, and MVV, between

the two groups, the lack of statistical significance across all

parameters suggests that the clinical implications of COVID-19's

impact on asthma may be more remarkable. These differences may not

indicate a substantial deviation in overall pulmonary function,

particularly in non-critically ill patients. Further exploration of

the pathophysiological mechanisms contributing to these differences

in pulmonary function is essential. Specifically, the role of

COVID-19 in exacerbating asthma symptoms may involve complex

inflammatory processes that affect airway smooth muscle function,

while the exact mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated.

Although the present study found poorer pulmonary

function in patients with COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial

asthma, the potential mechanisms underlying these differences were

not thoroughly explored. Future studies should investigate how

COVID-19-induced alterations in airway function, such as changes in

airway smooth muscle tone or inflammation beyond

eosinophil-mediated pathways, may contribute to these findings.

Although the observed differences in pulmonary function were not

statistically significant in terms of impairment rates across

functions, the poorer pulmonary function in patients with COVID-19

infection-induced bronchial asthma highlights the potential need

for adjusted management strategies. These may include more frequent

monitoring, early intervention, and personalized treatment plans to

better address the unique needs of this patient population.

The findings suggested that while the pulmonary

function in patients with COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial

asthma was slightly poorer than that of patients with typical

asthma, these differences might not necessitate entirely distinct

treatment protocols, while indicated the need for enhanced

monitoring and individualized management strategies, particularly

for older and male patients who exhibited poorer pulmonary

function. Given the observed reduction in key pulmonary function

indices, such as FEV1% and MEF75, in COVID-19-induced asthma,

additional interventions concentrating on maintaining airway

patency and preventing further pulmonary decline might be

especially beneficial for this subgroup of patients. Management

strategies for COVID-19-induced asthma can benefit from

incorporating early detection and treatment of airway inflammation,

as well as an elevated concentration on small airway function given

the potential subclinical changes observed in these patients.

Future studies should investigate whether the pathophysiological

mechanisms unique to COVID-19-induced asthma, such as possible

non-eosinophilic inflammatory pathways, require specific

therapeutic modifications beyond standard asthma treatments,

particularly in terms of long-term control medications and

pulmonary rehabilitation. While current treatment guidelines, such

as GINA, provide a robust framework for asthma management, the

subtle pulmonary function differences in COVID-19-induced asthma

suggest that treatment intensification or modifications may be

warranted to address specific functional impairments.

The present study has several limitations. Firstly,

the differing inclusion periods for the two groups, one group

diagnosed and treated prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the other

afterward, might introduce variability stemming from temporal

variations in environmental factors, clinical practices, or

healthcare accessibility. Secondly, the retrospective nature and

single-center setting of the study could limit the generalizability

of the findings and result in incomplete or inconsistent data for

certain variables. Thirdly, although the present study analyzed

routine inflammatory markers, such as total IgE, eosinophil count,

eosinophil percentage, and FeNO level, the retrospective design and

concentration on clinical outpatient data limited the inclusion of

more advanced biomarkers. Consequently, these parameters might not

fully capture the complexity of the inflammatory and immunological

responses in patients with COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial

asthma. Future investigations will benefit from the inclusion of

advanced inflammatory and immunological markers, such as cytokines

[for examle, interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-13, and tumor necrosis

factor-α (TNF-α)] and chemokines, to provide a more comprehensive

evaluation of the inflammatory profile in this patient population.

Lastly, while the sample size was adequate for preliminary

analysis, it might not provide sufficient statistical power to

detect more significant differences between the two groups. Future

prospective, multicenter studies are essential with standardized

methodologies to confirm and expand the findings. To enhance the

understanding of these findings' clinical significance, future

research should concentrate on conducting prospective studies with

larger, multi-center cohorts. Such studies should investigate the

long-term effects of COVID-19 on asthmatic patients, emphasizing

both the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms and their

implications for clinical practice. Particular attention should be

given to develop personalized therapeutic strategies for patients

with COVID-19-induced bronchial asthma.

In conclusion, although no significant difference

was found between the two groups in the rates of impairment in

ventilation function, reserve function, and small airway function,

significant differences were identified in various indicators,

including FEV1, RV/TLC, PEF, MEF75, MVV, FEV*30 and RV between the

two groups. The findings indicated that pulmonary function of

patients with COVID-19 infection-induced bronchial asthma was worse

than that of patients with typical asthma.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81900021), the Special

‘Sailing’ Program for Clinical Medical Development (grant no.

ZLRK202323), and the Beijing Clinical Key Specialty (grant no.

XKB2022B1002).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MQZ, JQZ and XDM contributed substantially to the

conception and design of the study and acquisition of data, as well

as analysis and interpretation of the data. MQZ, LNZ and PZ were

involved in interpretation of the data, and in drafting the

manuscript. MQZ, JQZ and XDM have participated sufficiently in the

study to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the

content and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the study in

ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any

part of the study are appropriately investigated and resolved. MQZ

and JQZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Alizadeh Z, Mortaz E, Adcock I and Moin M:

Role of epigenetics in the pathogenesis of asthma. Iran J Allergy

Asthma Immunol. 16:82–91. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Barbi E and Longo G: Chronic and recurrent

cough, sinusitis and asthma. Much ado about nothing. Pediatr

Allergy Immunol. 18 (Suppl 18):S22–S24. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE and Liu X: Asthma

prevalence, health care use, and mortality: United States,

2005-2009. Natl Health Stat Report: Jan 12, 1-14, 2011.

|

|

4

|

Vora AC: Bronchial asthma. J Assoc

Physicians India. 62 (3 Suppl):5–6. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sugita M, Kuribayashi K, Nakagomi T,

Miyata S, Matsuyama T and Kitada O: Allergic bronchial asthma:

Airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. Intern Med. 42:636–43.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Banno A, Reddy AT, Lakshmi SP and Reddy

RC: Bidirectional interaction of airway epithelial remodeling and

inflammation in asthma. Clin Sci (Lond). 134:1063–1079.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Liu D, Chen C, Chen D, Zhu A, Li F, Zhuang

Z, Mok CKP, Dai J, Li X, Jin Y, et al: Mouse models susceptible to

HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63 and cross protection from challenge with

SARS-CoV-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 120(e2202820120)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J,

Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, et al: Clinical characteristics

of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel Coronavirus-infected

pneumonia in wuhan, China. JAMA. 323:1061–1069. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Mason RJ: Pathogenesis of COVID-19 from a

cell biology perspective. Eur Respir J. 55(2000607)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu

Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, et al: Clinical features of patients

infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet.

395:497–506. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wu Z and McGoogan JM: Characteristics of

and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the

Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA.

323:1239–1242. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Peters MC, Sajuthi S, Deford P,

Christenson S, Rios CL, Montgomery MT, Woodruff PG, Mauger DT,

Erzurum SC, Johansson MW, et al: COVID-19-related genes in sputum

cells in asthma relationship to demographic features and

corticosteroids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 202:83–90.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zhu Z, Hasegawa K, Ma B, Fujiogi M,

Camargo CA Jr and Liang L: Association of asthma and its genetic

predisposition with the risk of severe COVID-19. J Allergy Clin

Immunol. 146:327–329.e4. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G, Gershon AS,

Bateman ED, Cruz AA and Boule LP: Global asthma prevalence in

adults: Findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC

Public Health. 12(204)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Liccardi G, Salzillo A, Sofia M, D'Amato M

and D'Amato G: Bronchial asthma. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 25:30–37.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kannan S, Shaik Syed Ali P, Sheeza A and

Hemalatha K: COVID-19 (Novel Coronavirus 2019)-recent trends. Eur

Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 24:2006–2011. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wang F, Kream RM and Stefano GB: An

evidence based perspective on mRNA-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development.

Med Sci Monit. 26(e924700)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Mahase E: Covid-19: Increased demand for

steroid inhalers causes ‘distressing’ shortages. BMJ.

369(m1393)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Badar A, Salem AM, Bamosa AO, Qutub HO,

Gupta RK and Siddiqui IA: Association between FeNO, total blood

IgE, peripheral blood eosinophil and inflammatory cytokines in

partly controlled asthma. J Asthma Allergy. 13:533–543.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Hoshino Y, Soma T, Uchida Y, Shiko Y,

Nakagome K and Nagata M: Treatment resistance in severe asthma

patients with a combination of high fraction of exhaled nitric

oxide and low blood eosinophil counts. Front Pharmacol.

13(836635)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Yin SS, Liu H and Gao X: Elevated

fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) is a clinical indicator of

uncontrolled asthma in children receiving inhaled corticosteroids.

Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 55:66–77. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Bafadhel M, Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, Singh D,

Darken P, Jenkins M, Aurivillius M, Patel M and Dorinsky P:

Benefits of Budesonide/Glycopyrronium/Formoterol fumarate dihydrate

on COPD exacerbations, lung function, symptoms, and quality of life

across blood eosinophil ranges: A Post-hoc analysis of data from

ETHOS. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 17:3061–3073.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Pham DD, Lee JH, Kim JY, An J, Song WJ,

Kwon HS, Cho YS and Kim TB: Different impacts of blood and sputum

eosinophil counts on lung function and clinical outcomes in asthma:

Findings from the COREA cohort. Lung. 200:697–706. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Kaminsky DA and Irvin CG: What long-term

changes in lung function can tell us about asthma control. Curr

Allergy Asthma Rep. 15(505)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Koefoed HJL, Zwitserloot AM, Vonk JM and

Koppelman GH: Asthma, bronchial hyperresponsiveness, allergy and

lung function development until early adulthood: A systematic

literature review. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 32:1238–1254.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

van der Wiel E, ten Hacken NH, Postma DS

and van den Berge M: Small-airways dysfunction associates with

respiratory symptoms and clinical features of asthma: A systematic

review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 131:646–657. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Tyler SR and Bunyavanich S:

Leveraging-omics for asthma endotyping. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

144:13–23. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Milanese M, Miraglia Del Giudice E and

Peroni DG: Asthma, exercise and metabolic dysregulation in

paediatrics. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 47:289–294.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Mitchell PD and O'Byrne PM: Biologics and

the lung: TSLP and other epithelial cell-derived cytokines in

asthma. Pharmacol Ther. 169:104–112. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Du K, Zheng M, Zhao Y, Xu W, Hao Y, Wang

Y, Zhao J, Zhang N, Wang X, Zhang L and Bachert C: Impaired small

airway function in non-asthmatic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal

polyps. Clin Exp Allergy. 50:1362–1371. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Yuan H, Liu X, Li L, Wang G, Liu C, Zeng

Y, Mao R, Du C and Chen Z: Clinical and pulmonary function changes

in cough variant asthma with small airway disease. Allergy Asthma

Clin Immunol. 15(41)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Tosca MA, Crocco M, Girosi D, Olcese R,

Schiavetti I and Ciprandi G: Unaffected asthma control in children

with mild asthma after COVID-19. Pediatr Pulmonol. 56:3068–3070.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Ono Y, Obayashi S, Horio Y, Niimi K,

Hayama N, Ito Y, Oguma T and Asano K: Asthma exacerbation

associated with COVID-19 pneumonia. Allergol Int. 70:129–130.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Codispoti CD, Bandi S, Patel P and

Mahdavinia M: Clinical course of asthma in 4 cases of coronavirus

disease 2019 infection. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 125:208–210.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Garcia-Pachon E, Ruiz-Alcaraz S,

Baeza-Martinez C, Zamora-Molina L, Soler-Sempere MJ, Padilla-Navas

I and Grau-Delgado J: Symptoms in patients with asthma infected by

SARS-CoV-2. Respir Med. 185(106495)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|