Introduction

The pathogeneses of osteoporosis and sarcopenia, the

two most common diseases encountered in older adults, are closely

related to age (1). Osteoporosis

refers to the deterioration of bone density and microarchitecture

(2), whereas sarcopenia refers to

defects in muscle quantity, quality and function (3). Numerous studies have demonstrated that

muscles and bones are spatially and metabolically connected

(4). Furthermore, individuals with

sarcopenia are five times more likely to develop osteoporosis than

healthy individuals and vice versa (5). Therefore, some studies have termed the

coexistence of osteoporosis and sarcopenia as osteosarcopenia

(6,7). The presence of OS leads to more

fractures, frailty, hospitalization, disability and mortality than

osteoporosis or sarcopenia alone (6).

Muscle and bone share a common origin of mesenchymal

precursors (8). Furthermore,

several molecular mechanisms regulate both muscles and bones

(9). Thus, finding the common

molecule that affects the progress of osteogenesis and myogenesis

could help determine the pathogenesis of osteosarcopenia. Bone

marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSC) are pluripotent stem cells

with trilineage differentiation abilities, which include

osteogenesis, lipogenesis and chondrogenesis (10,11).

L6 is a myoblast strain isolated from the skeletal muscle of rats

that be used to study myogenesis. Secreted frizzled-related protein

1 (SFRP1) is an antagonist of the Wnt signaling pathway that binds

to Wnt proteins and prevents it from interacting with their cell

surface receptors. This helps regulate the balance between cell

proliferation and differentiation, which is essential for normal

development and tissue homeostasis. Dysregulation of SFRP1 has been

implicated in various human diseases, including cancer, fibrosis

and degenerative disorders.

SFRP1, which modulates the Wnt signaling pathway,

plays a significant role in bone and muscle development,

homeostasis and regeneration. SFRP1 plays a role in the regulation

of osteoblast differentiation by inhibiting the Wnt signaling

pathway. Thus, a decrease in SFRP1 expression can increase bone

formation and reduce bone resorption, whereas an increase in SFRP1

expression can decrease bone mass and increase susceptibility to

fractures. SFRP1 also plays a role in myogenesis, the process of

muscle tissue formation and post-injury muscle regeneration. SFRP1

promotes the activation and differentiation of muscle satellite

cells, which are responsible for muscle repair and growth.

Additionally, SFRP1 inhibition may have a role in preventing muscle

atrophy, which is the loss of muscle mass due to various factors

such as aging or diseases. Thus, SFRP1 may be a potential

therapeutic target to prevent muscle atrophy.

Although these findings suggested that SFRP1 may be

an essential molecule in osteosarcopenia, its upstream regulator

remains unknown. microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are small non-coding RNA

molecules that play a crucial role in regulating gene expression at

the post-transcriptional level. They can modulate the stability and

translation of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to control protein

synthesis and cellular functions.

By binding to the 3'UTR of target mRNA, they enable

degradation or inhibition of translation. Additionally, they

participate in complex life processes such as cell proliferation,

differentiation, apoptosis and carcinogenesis, which are closely

related to the occurrence, development, prognosis, diagnosis and

treatment of several diseases (12,13).

miRNAs are involved in the proliferation and differentiation of

bones or muscles (14-16).

For example, miR-34a-5p promotes osteogenic differentiation by

targeting HDAC1(17), miR-29a-3p

promotes proliferation and inhibits osteogenic differentiation by

targeting FOXO3(18), miR-130b

inhibits proliferation and promotes myoblast differentiation by

targeting Sp1(19) and miR-452

promotes proliferation and inhibits myoblast differentiation by

targeting ANGPT1(20). However,

only a few studies have evaluated miRNAs that regulate both bone

and muscle actions through a single pathway.

Muscle and bone share a common origin and are

regulated by several molecular mechanisms (9). Osteoblasts and myoblasts originate

from the same mesenchymal stem cells (8). Among these, bone marrow mesenchymal

stem cells (BMSC)s are currently being studied (10). In osteoporosis, the osteogenic

capacity of BMSC is diminished, which decreases bone formation

(11).

The present study extracted bone marrow stem cells

from osteoporotic and control rats for transcriptome sequencing to

identify the differential gene SFRP1. The results indicated that

miR-206-3p might target SFRP1. miR-1, miR-133 and miR-206 are known

muscle-specific miRNAs that play an important role in muscle growth

and development (21). Therefore,

the regulatory roles of miR-206-3p was assessed in BMSC and

myogenic cells. The results demonstrated that miR-206-3p targets

SFRP1 through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which in turn

affects muscle and bone differentiation.

Materials and methods

Animals

The experimental animal study protocol was approved

by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Kunming Medical

University, Kunming, China (approval no. kmmu20230916). All animal

experiments and handling were performed in accordance with the

Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the

National Institutes of Health [NIH Publication No. 8523, revised

1985(22)]. A total of

six-week-old, healthy, female Sprague-Dawley rats, each weighing

250-300 g, free of specific pathogens, were purchased from the

Department of Laboratory Animal Science, Kunming Medical

University. All animals were maintained under a standard 12-h

light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. Environmental

conditions were maintained with relative humidity ranging from

30-60% and a temperature of 23±2˚C. After adaptive feeding, the

rats were ovariectomized (OVX group) or subjected to a sham surgery

(sham group; n=3 per group). Subsequently, the rats were fed for 3

months and euthanized. Subsequently, the rats were fed for 3 months

and sacrificed. Sacrifice was by intraperitoneal injection of

excessive sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg).

Ovariectomization

Rats were anesthetized intraperitoneally with 3%

sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/kg) and ovariectomy (OVX) was performed

under anesthesia. After making incisions on both sides of the

abdominal midline, the proximal end of each fallopian tube was

ligated and the ovaries were isolated. After bilateral ovaries were

excised with scissors, the wound was sutured.

Microcomputed tomography scanning

After the rats were euthanized, the femurs were

isolated and scanned using micro-computed tomography (CT). The

distal femur was scanned to determine the trabecular bone

volume/tissue volume ratio (BV/TV), bone mineral density (BMD) and

trabecular thickness (TbTh).

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

The rat femurs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

for 24 h. Thereafter, the specimens were soaked in 70% ethanol for

3 days at 4˚C and the liquid was changed every day. Subsequently,

the specimens were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-µm sections.

Finally, the sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and stained

with hematoxylin and eosin. The sections were stained 10 min at

room temperature and observed using a light microscope

(magnification, x20).

Von Kossa staining

The rat femurs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

for 24 h then immersed in 70% ethanol with daily solution changes

for 3 days and stored at 4˚C. All subsequent procedures were

performed at 4˚C whenever possible. Thereafter, embedding and

sectioning were performed to obtain 5 µm thick hard tissue

sections. The sections were stained using Von Kossa solution

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) following the

manufacturer's instructions: Von Kossa silver solution was added

dripwise to the sections which were then irradiated with strong

light for 15-60 min at room temperature before being washed with

distilled water for 1 min at room temperature. After sealing, the

sections were observed under a light microscope (magnification,

x20).

Toluidine blue O solution

After being fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h,

the rat femurs were soaked in 70% ethanol for 3 days at 4˚C. The

ethanol was changed every day. Thereafter, the femur was sectioned

at 5 µm and stained with toluidine blue solution (Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The sections were stained with

1% toluidine blue O solution for 10 min at room temperature and

observed using a light microscope (magnification x20).

Tartrate-resistant acidic phosphatase

staining

After being fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h,

the rats femurs were soaked in 70% ethanol for 3 days at 4˚C. The

ethanol was changed every day. Thereafter, the femur was sectioned

at 5 µm and stained using tartrate-resistant acidic phosphatase

(TRAP; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). The sections were

reacted with tartrate-resistant acidic phosphatase working solution

for 20 min at 37˚C in the dark and observed using a light

microscope (magnification x20).

BMSC isolation and culture

BMSCs were isolated from the bone marrow aspirate of

the rat femurs. In the OVX group, the BMSCs were isolated 3 months

after OVX. After being euthanized, the rats femurs were dissected

out aseptically and the external soft tissue was discarded. A

20-gauge needle was used to prepare the cell suspension by

repeatedly flushing the bone marrow lumen with minimum essential

medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing 1%

penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The cells were inoculated into cell culture flasks and subsequently

inoculated in an α-minimal essential medium supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37˚C in a humidified atmosphere of 5%

CO2.

Flow cytometry identification of

BMSC

Third-generation BMSCs were digested with TrypLE

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and the cells were

resuspended in a complete medium to produce single-cell suspensions

containing 5x105-1x106 cells/ml. Thereafter,

the cells were washed twice with PBS containing 1% bovine serum

albumin (1% BSA/PBS; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.). Thereafter, the cells were resuspended in 1% BSA/PBS before

being transplanted into Eppendorf tubes. CD29 (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. 2282645), CD44 (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. 2252597), CD45

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. 2265339) and

CD90 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. 2227596)

cells and the antibody compensation beads were added to the

Eppendorf tubes according to the manufacturer's instructions. The

tubes were incubated at 4˚C for 60 min. Thereafter, the cells were

washed with 1%BSA/PBS twice at 4˚C before being resuspended.

Finally, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (BD

FACSCelesta™), and analyzed using FlowJov10.6.2 (FlowJo LLC).

Trilineage differentiation and

staining of BMSCs

BMSCs were placed in osteogenic, lipogenic and

chondrogenic induction media to induce differentiation. The

osteogenic, lipogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of BMSCs was

determined by staining with alizarin red, oil red O and Alcian

blue, respectively. For osteogenic differentiation, alizarin red

staining working solution stained cells for 6 min at room

temperature. For adipogenic differentiation, oil red O staining

working solution was used to stain cells for 30 min at room

temperature. For chondrogenic differentiation, Alcian blue staining

working solution was stained at 37˚C for 1 h.

Transcriptome sequencing of BMSCs

The BMSCs obtained from the OVX and Sham groups were

cultured up to P3 generation and four samples containing 5 million

cells each were obtained from each group. To extract the total RNA

from the cells, 1 ml of TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) was added to each sample and the concentration

and purity of the extracted RNA were detected using NanoDrop 2000

(NanoDrop Technologies; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After the

RNA quality control had reached the standard, the ribosomal RNA was

removed and fragmented into small segments of approximately 200 bp.

Reverse transcription is then performed to generate cDNA. The

double-stranded cDNA structure has sticky ends, which are converted

to blunt ends by adding an End Repair Mix. Subsequently, a single A

base is added to the 3' end to facilitate the ligation of a

Y-shaped adapter, forming the adapter-ligated product. The product

is then purified and subjected to size selection. The selected

fragments are amplified by PCR, and the final library is purified.

The library is sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform

(Illumina, Inc.).

L6 cell culture and myogenic

differentiation

L6 cells were obtained from the Fan Wenxing Research

Group of the First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical

University. The L6 cells were inoculated in a high-glucose

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin. These were then incubated in a

constant-temperature cell incubator at 37˚C and 5% CO2.

When the L6 cells had reached 60% confluence, the growth medium was

aspirated and the cells were washed twice with PBS. Thereafter, a

medium that induced myogenic differentiation [DMEM supplemented

with 2% horse serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)] was

added. The differentiation medium was replaced daily.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q) PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells (1x106

cells/ml) using TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

following the manufacturer's protocol. RNA (1 µg per sample) was

then reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a reverse transcription

kit (RR036A, Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). qPCR was performed

with the TB Green Premix Ex Taq II kit (RR820A, Takara

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) on a QuantStudio3 Real-Time PCR System

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). All

procedures were performed according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The PCR amplification conditions were 95˚C for 30 sec

(initial denaturation), next 40 cycles of 95˚C for 5 sec, and 60˚C

for 34 sec, then 95˚C for 5 sec and 60˚C for 60 sec (dissociation),

then cooled to 37˚C. Relative gene expression was determined using

the 2−ΔΔCq (23) method

and normalized to GAPDH mRNA expression. All mRNA primers (Table I) were synthesized by Sangon Biotech

Co., Ltd. To detect miRNA expression, total miRNA was extracted

from the cells using RNAiso for small RNA (9753A, Takara

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The miRNAs were reverse transcribed using

the Mir-X miRNA First-Strand Synthesis kit (638313, Takara

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). RT-qPCR was performed using the miRNA

tailing reaction. The relative transcription levels of miRNA were

normalized to that of U6 RNA. All miRNA primers (Table I) were synthesized by Sangon Biotech

Co., Ltd.

| Table IPrimers. |

Table I

Primers.

| Gene symbol | Forward | Reverse |

|---|

| SFRP1 |

TACTGGCCCGAGATGCTCAA |

TACTGGCCCGAGATGCTCAA |

| GAPDH |

CAGGTTGTCTCCTGTGACTT |

TTATGGGGTCTGGGATGGAA |

| U6 |

TGGAACGCTTCACGAATTTGCG |

GGAACGATACAGAGAAGATTAGC |

| miR-206-3p |

CGTGGAATGTAAGGAAGTGTGTGG | |

Western blotting

RIPA lysate (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) was used to lyse the cells and extract the

proteins. A total of 20 µg (as measured by the BCA protein assay

kit) of the protein sample was electrophoresed on a 10% sodium

dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. The isolated proteins were

transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane by wet

transfer. The PVDF membranes were blocked at room temperature in 5%

skimmed milk for 2 h and incubated overnight with the primary

antibody at 4˚C. Subsequently, the PVDF membranes were incubated

with horseradish peroxide-coupled secondary antibodies for 2 h at

25˚C. The results were visualized using an enhanced

chemiluminescence solution (MilliporeSigma) after washing the

membranes. The protein bands were quantified using ImageJ v1.8.0

(National Institutes of Health). The antibody and dilution ratios

were as follows: GAPDH, 1:50,000, Proteintech Group, Inc., cat. no.

10494-1-AP; osteopontin (OPN), 1:4,000, Proteintech Group, Inc.,

cat. no. 22952-1-AP; osteocalcin (OCN), 1:1,000, Proteintech Group,

Inc., cat. no. 23418-1-AP; SFRP1, 1:1,000, Bioss, bs-1303R; lycogen

synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β), 1:5,000, Proteintech Group, Inc.,

cat. no. 82061-1-RR; α-tubulin, 1:5,000, Proteintech Group, Inc.,

cat. no. 11224-1-AP; HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit lgG(H+L),

1:10,000, Proteintech Group, Inc., cat. no. SA 00001-2; and

HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG(H+L), 1:10,000, Proteintech

Group, Inc., cat. no. SA 00001-1. GAPDH was used as an internal

reference protein in Fig. 5, while

α-tubulin was used in Fig. 2,

Fig. 3 and Fig. 4.

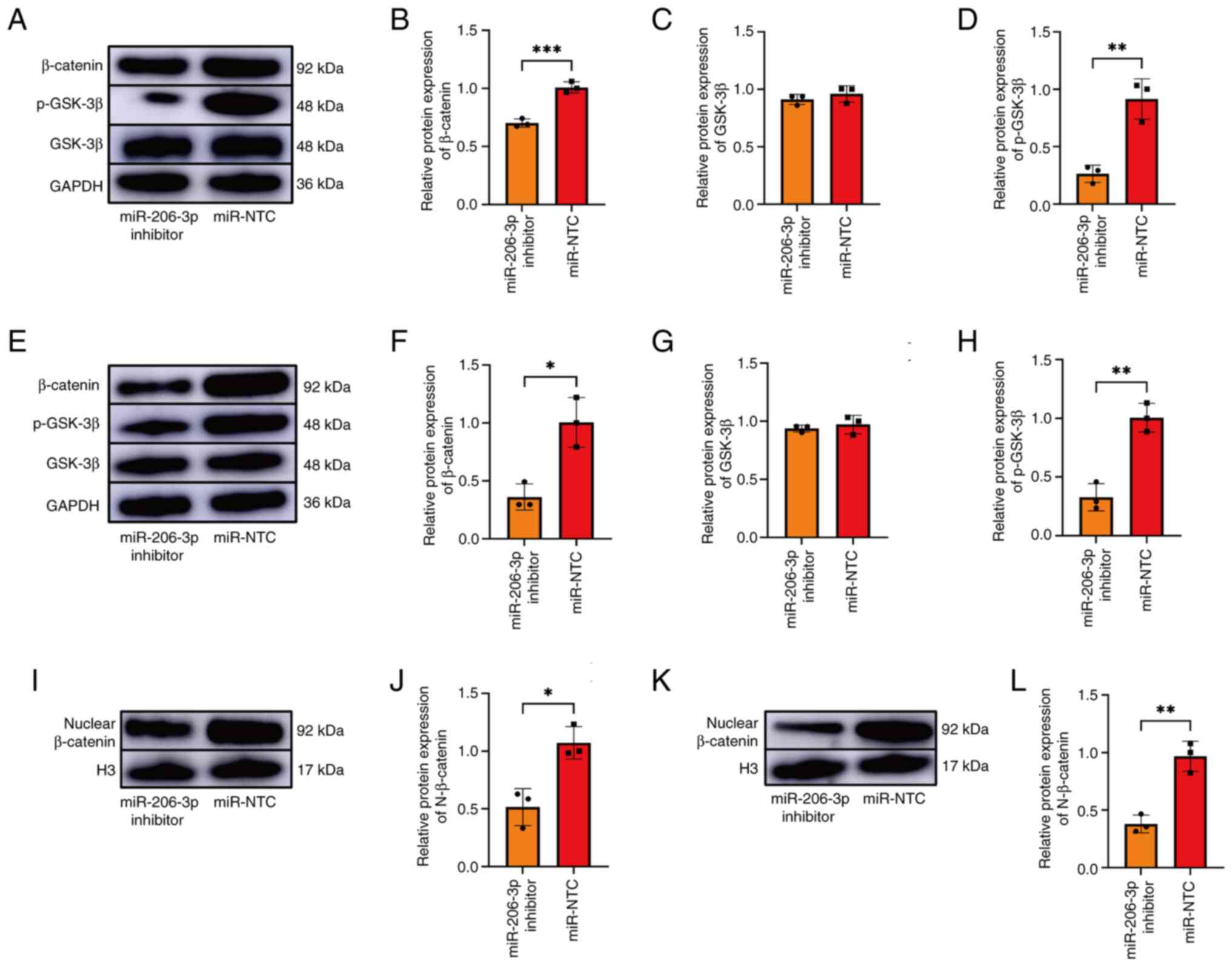

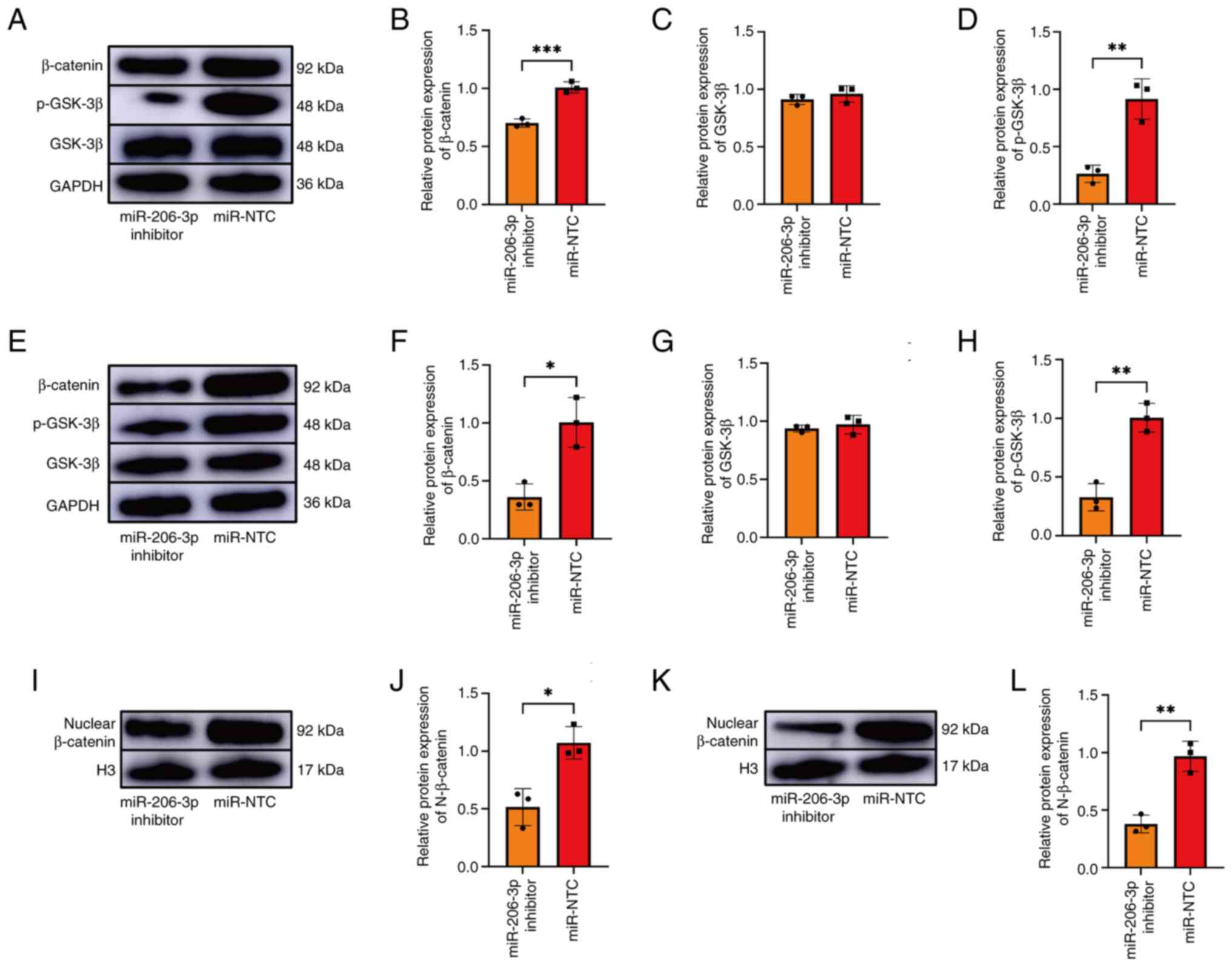

| Figure 5Expression of GSK-3β, p-GSK-3β,

β-catenin and nuclear β-catenin in the transfected BMSCs and L6

cells. (A-D) The expression of GSK-3β, p-GSK-3β, β-catenin, SFRP1

were detected by western blotting in the transfected group of BMSC.

(E-H) The expression of GSK-3β, p-GSK-3β, β-catenin and SFRP1 in

the transfected L6 cells was detected by western blotting. (I and

J) The expression of nuclear β-catenin in the transfected BMSCs. (K

and L) The expression of nuclear β-catenin in the transfected L6

cells. The presented gel blots have been cropped from different

parts of the gel and are separated with black lines. Data were

analyzed using Student's t-test (n=3). *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. GSK, glycogen

synthase kinase; p-, phosphorylated; BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal

stem cells; SFRP1, secreted frizzled-related protein 1; NTC,

negative control. |

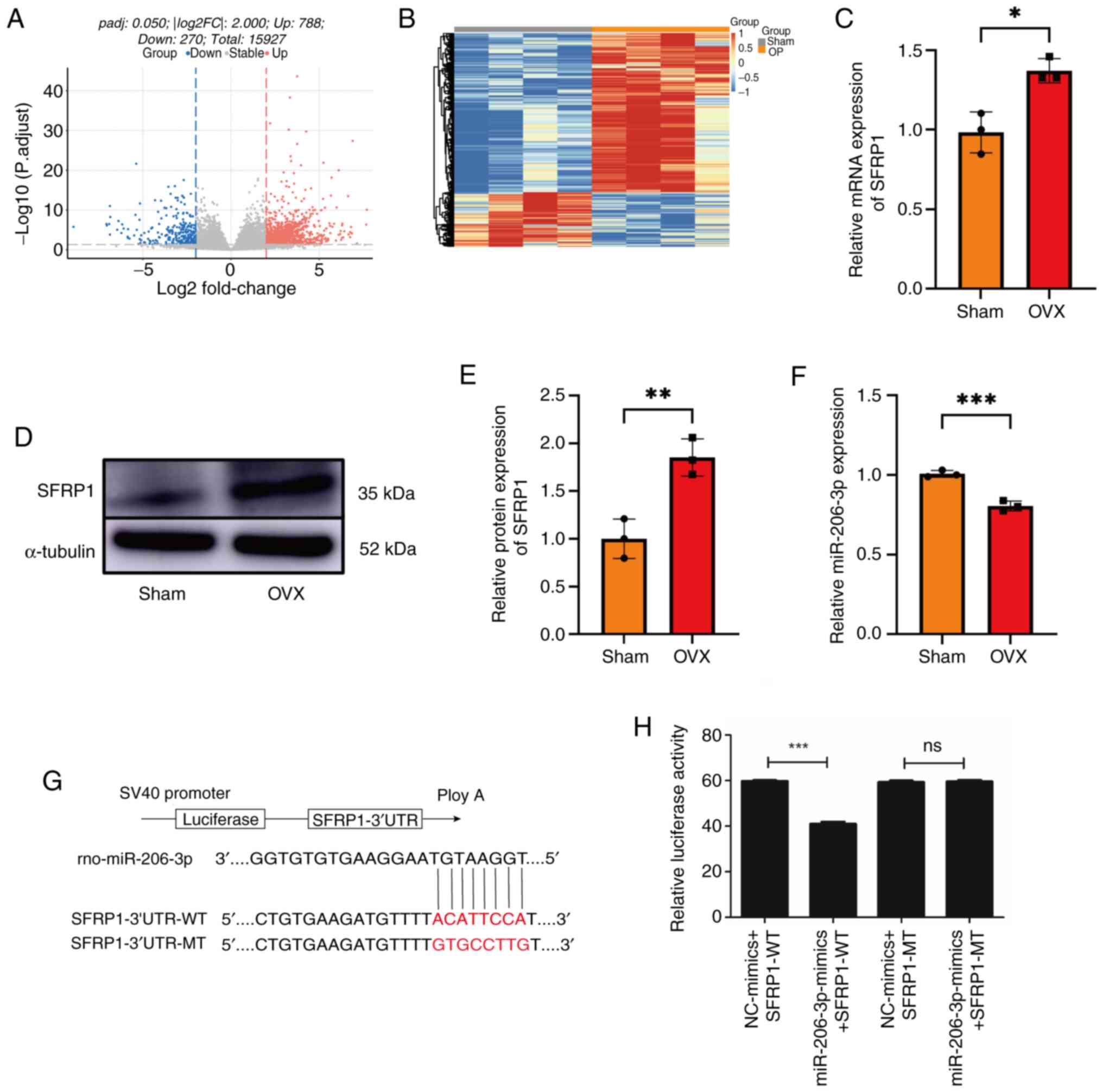

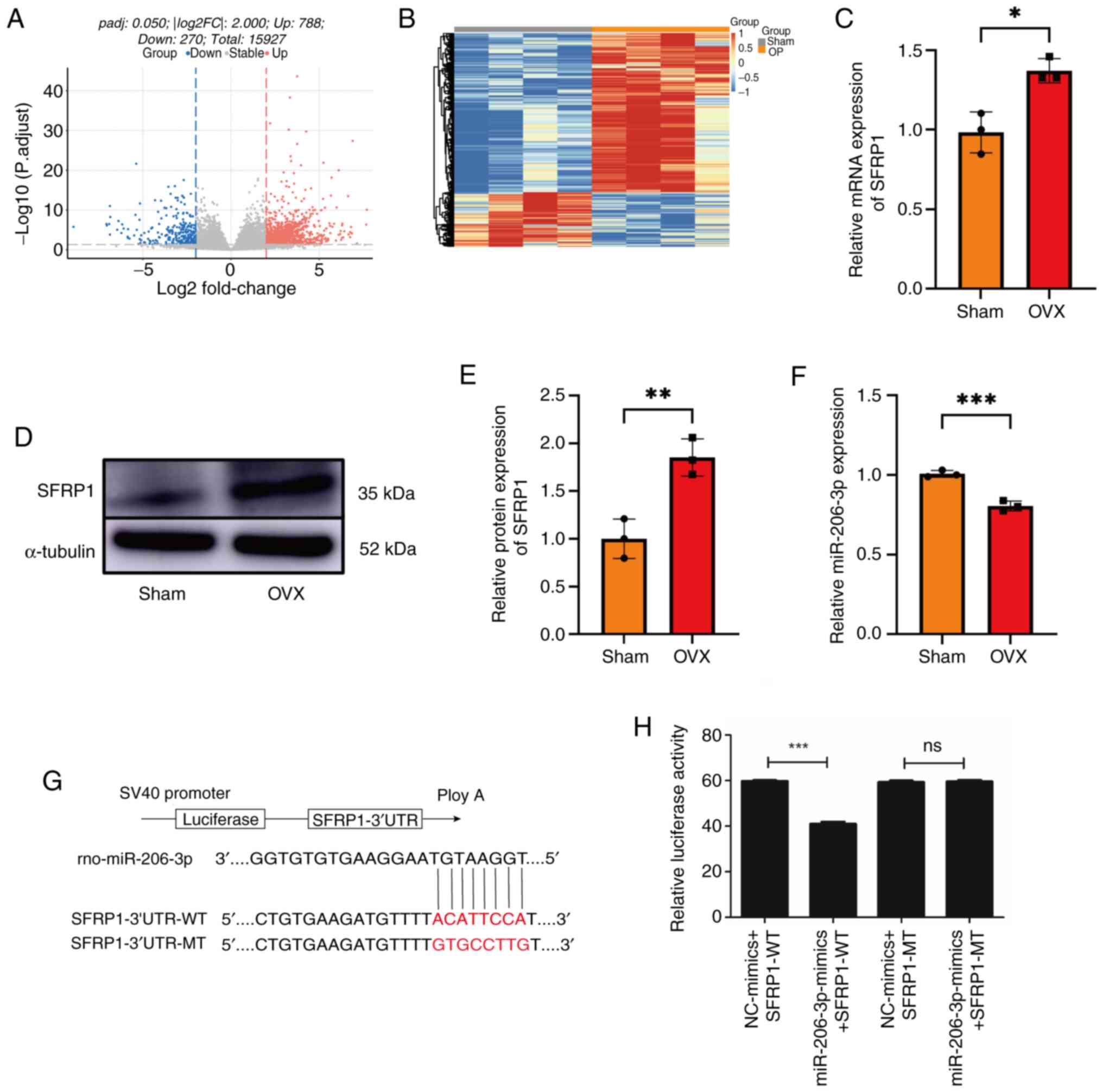

| Figure 2SFRP1 and miR-206-3p are expressed in

the BMSCs of the OVX and Sham groups. mRNA differential analysis in

the form a (A) volcano plot and (B) clustering heatmap. (C)

quantitative PCR revealed in BMSCs that compared with the Sham

group, the OVX group demonstrated an increase in the expression of

SFRP1. GAPDH was used as an internal reference in the PCR

experiments. (D) Western blotting results and (E) quantification in

BMSCs. Compared with the Sham group, the OVX group demonstrated an

increase in the expression of SFRP1. Gel blots cropped from

different parts of the gel and separated by black lines are

presented. α-tubulin was used as an internal reference in this

experiment. (F) PCR revealed that compared with the Sham group, the

OVX group demonstrated an increase in the expression of miR-206-3p.

U6 was used as an internal reference in the PCR experiments. (G,H)

Dual-luciferase reporter assay demonstrated that miR-206-3p could

bind to SFRP1. Data were analyzed using Student's t-test (n=3).

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. SFRP1, secreted frizzled-related protein

1; miR, microRNA; BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; OVX,

ovariectomized. |

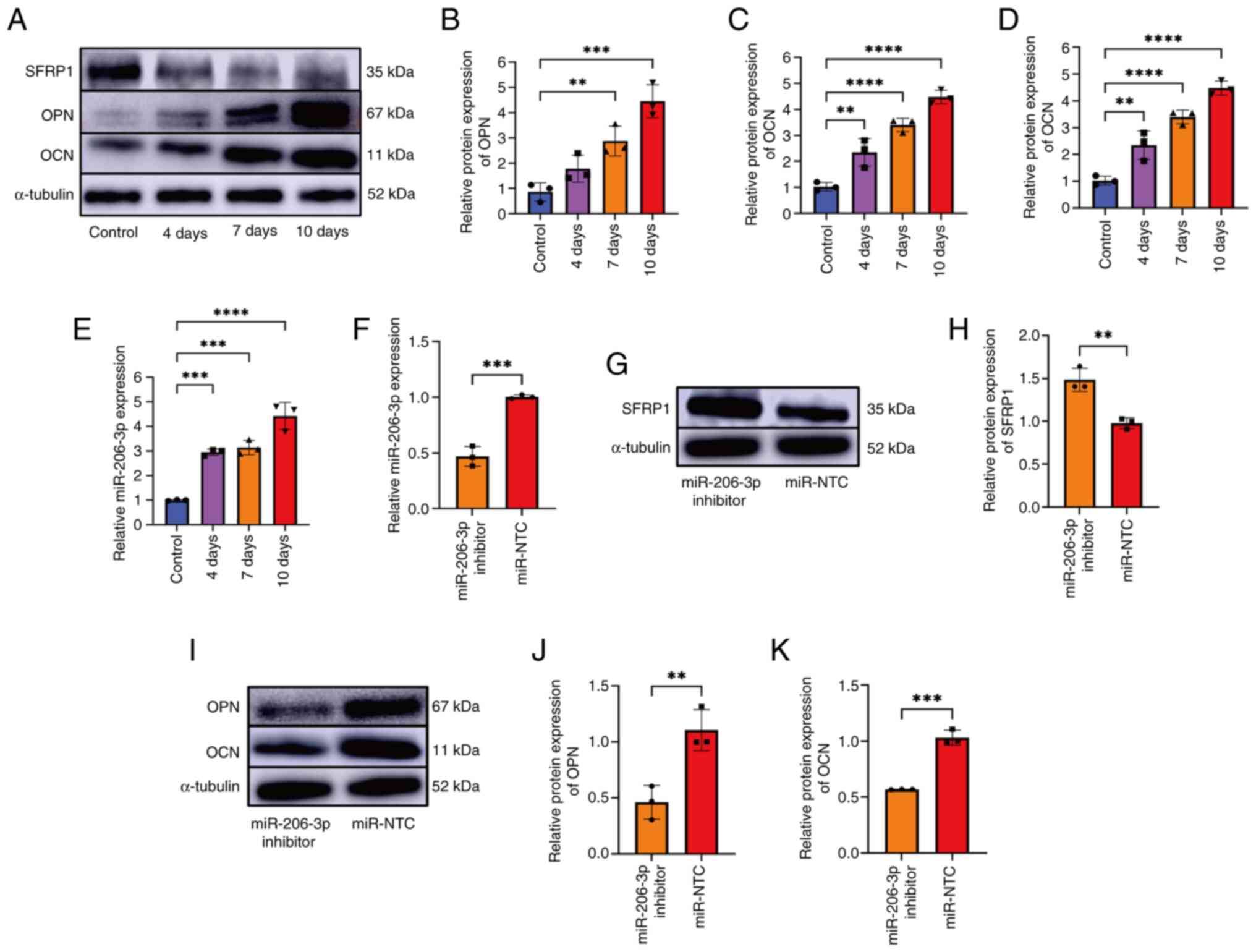

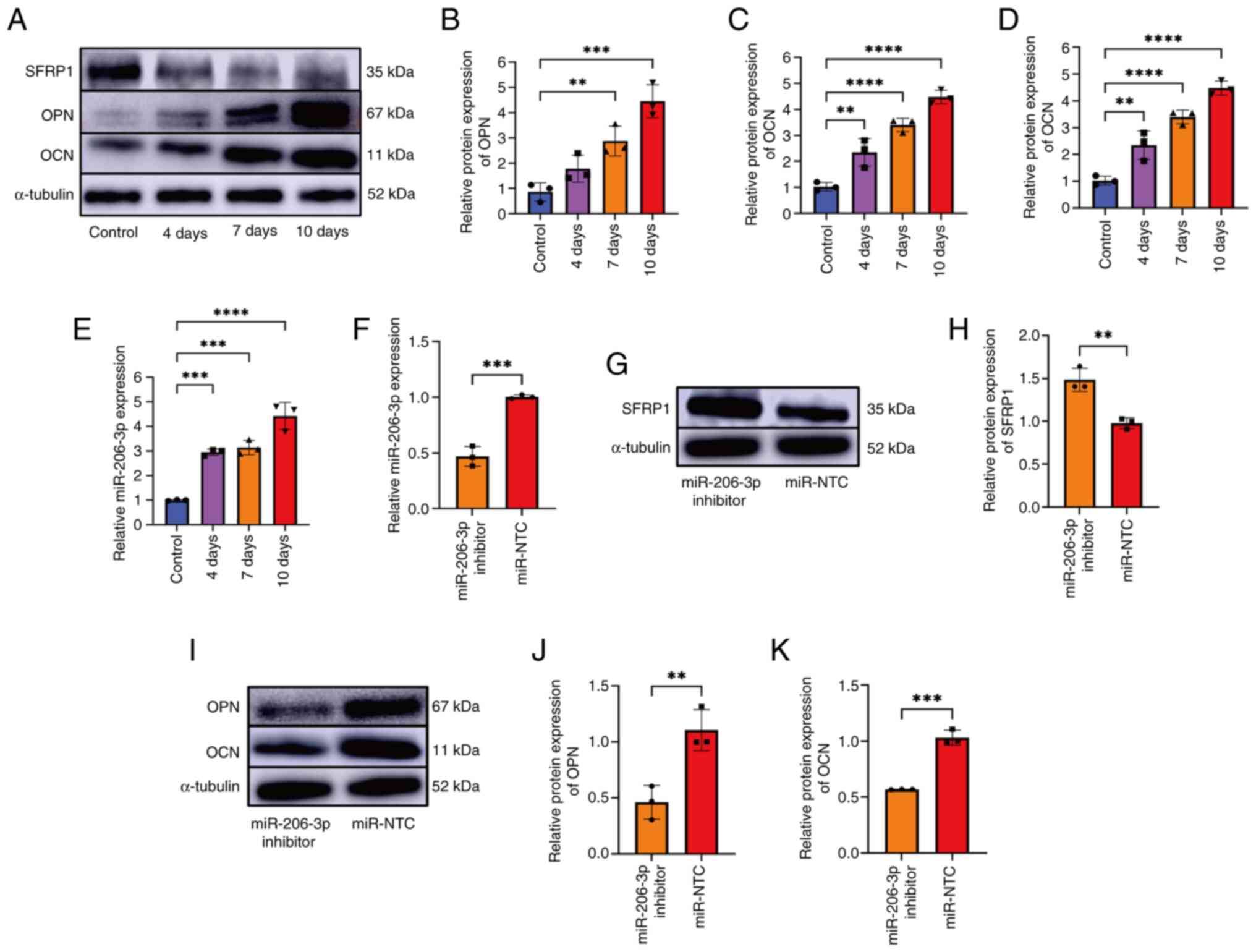

| Figure 3Detection of the osteogenic ability

of miR-206-3p inhibitor-transfected BMSCs. (A-D) Expression levels

of SFRP1, OPN and OCN at 0, 4, 7 and 10 days during osteogenic

differentiation. (E) PCR revealed that the expression of miR-206-3p

was upregulated at 0, 4, 7 and 10 days, respectively. (F) PCR

revealed that compared with the miR-NTC group, the miR-206-3p

inhibitor group demonstrated a reduction in the expression of

miR-206-3p. U6 was used as an internal reference in PCR. (G and H)

The expression level of SFRP1 increased following the silencing of

miR-206-3p. (I-K) The expression of OPN and OCN were detected using

western blotting. The presented gel blots have been cropped from

different parts of the gel and are separated with black lines. Data

were analyzed using the Welch and Brown-Forsy versions of one-way

ANOVA (B-E) or Student's t-test (F-K) and compared using the

χ2 test. **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. miR,

microRNA; BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; SFRP1,

secreted frizzled-related protein 1; OPN, osteopontin; OCN,

osteocalcin; NTC, negative control. |

Plasmid transfection

The miR-206-3p inhibitor and its negative control

(miR-NTC) were purchased from Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. The cells

were transfected with Lipofectamine® 3000 (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The transfected nucleic acid concentration was 50 nm.

Transfection was performed for 20 min at room temperature to form

complexes and then cells were incubated at 37˚C in a 5%

CO2 incubator. The transfected cells were subjected to

follow-up experiments 24-48 h after transfection. Negative control

sequence: TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

A total of 293 cells were cultured to a density of

2x104 cells/well in 96-well culture plates. The cells

were transfected with dual-luciferase reporter (DLR) construct p1

(0.2 µg) or co-transfected with DLR construct p2 (0.2 µg) and the

internal control vector pRL-TK, pRL-SV40, or pRL-CMV (Promega

Corporation) at a ratio of 20:1 using Lipofectamine®

2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). At 5 h following

transfection, the transfection medium was removed and replenished

with a medium containing 6 µM of curcumin (MilliporeSigma)

solubilized in 100% dimethylsulfoxide (MilliporeSigma). At 48 h

following transfection, luciferase activity was measured using a

DLR assay (Promega Corporation). Renilla luciferase activity was

normalized to firefly luciferase activity in cells transfected with

the DLR construct p1 and firefly luciferase activity was normalized

to Renilla luciferase activity in cells co-transfected with DLR

construct p2 and the control vector.

TargetScan

The candidate target miRNA of SFRP1 was predicted

using TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/).

Statistical analysis

Experimental data were expressed as means ± standard

deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version

19.0; IBM Corp.). Data were analyzed using Welch and Brown-Forsythe

versions of one-way ANOVA or Student's t-test and compared using

the χ2 test. All experiments were repeated at least

three times. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

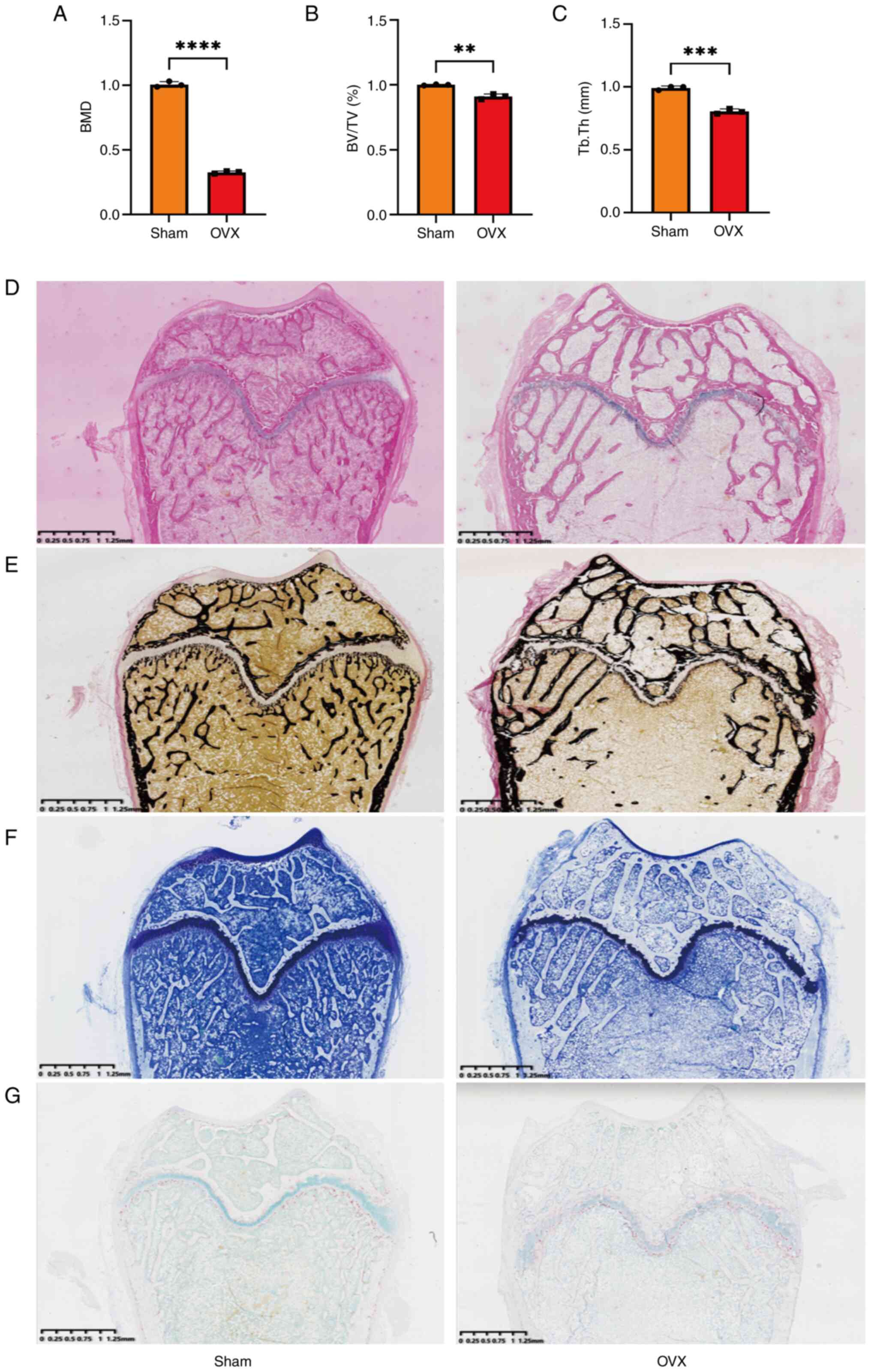

Establishment and identification of

osteoporosis model in the OVX group

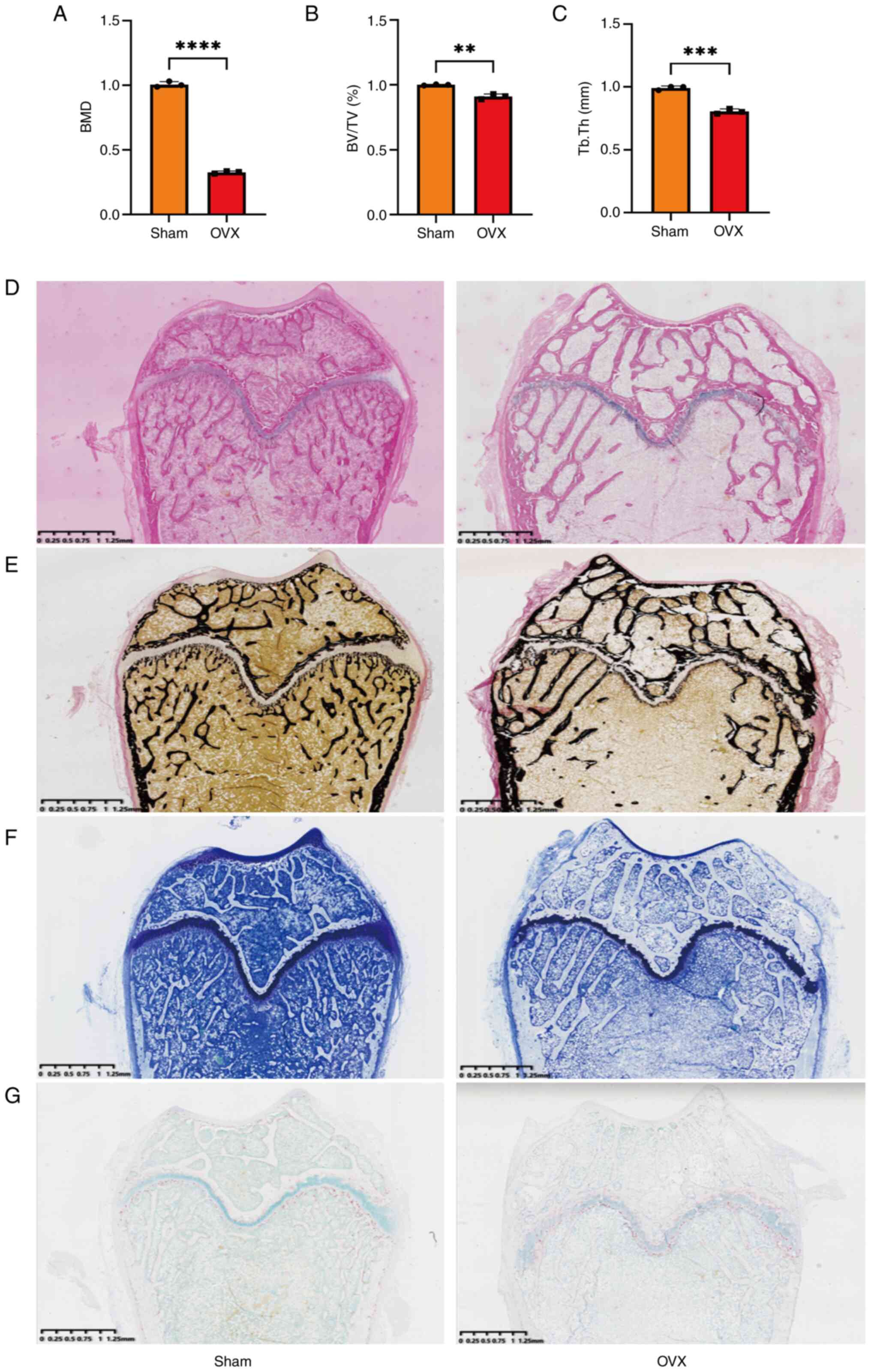

An osteoporosis rat model was established by

ovariectomy and the degree of osteoporosis was evaluated using

histological staining. Quantitative analysis of micro-CT data

demonstrated that BMD, BV/TV and TbTh were lower in the OVX group

than in the Sham group (Figs. 1A-C

and S1). Furthermore,

immunohistochemical staining of the rat femurs demonstrated an

imbalance in bone metabolism in the OVX group. The resultant

reduction in bone mineral density and damage to bone

microarchitecture confirmed the presence of osteoporosis in the OVX

group (Fig. 1D-G).

| Figure 1Quantitative analysis of micro-CT

data and histological staining results. Quantitative analysis of

(A) BMD, (B) BV/TV and (C) TbTh. Results of (D) H&E, (E) Von

Kossa, (F) toluidine blue and (G) TRAP staining. Data were analyzed

using Student's t-test (n=3). **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. CT, computed

tomography; BMD, bone mineral density; BV/TV, bone volume/tissue

volume ratio; TbTh, trabecular thickness; H&E, hematoxylin and

eosin; TRAP, tartrate-resistant acidic phosphatase. |

Isolation, culture, identification and

three-line differentiation of the BMSCs from the rat bone

marrow

The differentiation of the extracted BMSCs into

osteogenic, lipogenic and chondrogenic cells was confirmed using

alizarin red, oil red O and Alcian blue staining, respectively

(Fig. S2). Flow cytometry

demonstrated that BMSCs displaying CD29+,

CD44+, CD45- and CD90+ had a

purity of >98.6% (Fig. S3).

This indicates that the cells extracted using the method of the

present study were rat BMSCs. Western blotting demonstrated that

the expression of OPN and OCN were significantly lower in the BMSC

of the OVX group than in the BMSC of the Sham group (Fig. S4). This indicated that the

osteogenic differentiation ability of BMSCs in the OVX group was

lower than that in the Sham group.

SFRP1 increases in the OVX group's

BMSCs and decreases during osteogenesis

RNA sequencing revealed that, compared with the Sham

group, 788 mRNAs were upregulated and 270 mRNAs were downregulated

in the OVX group (Table SI).

Fig. 2A and B shows the mRNA differential analysis

volcano plot and clustering heatmap. Among the markedly upregulated

mRNA, SFRP1 negatively regulates osteoblasts and osteoblast

functions and it plays an important role in maintaining bone

stability. Therefore, SFRP1 was selected as the research object.

Results of the RT-qPCR and western blotting for the detection of

SFRP1 expression were consistent with those of RNA sequencing

(Fig. 2C-E). TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/) predicted that miR-206-3p

directly targeted the 3'UTR region of SFRP1 (Fig. S5). RT-qPCR revealed that miR-206-3p

expression was downregulated in the BMSCs of the OVX group and the

expression of miR-206-3p was negatively associated with that of

SFRP1 (Fig. 2F). DLR assay was

performed to detect the binding sites between miR-206-3p and SFRP1

(Fig. 2G and H). These findings indicated that

miR-206-3p may directly target SFRP1 mRNA.

miR-206-3p regulates the osteogenic

differentiation of BMSCs by targeting SFRP1

The expression levels of miR-206-3p during

osteogenic differentiation after transfection were measured at 4, 7

and 10 days (Fig. 3A-E). The

expression level of miR-206-3p increased markedly during osteogenic

differentiation. To explore the function of miR-206-3p during

osteogenic differentiation of the BMSCs, the BMSCs were transfected

with an miR-206-3p inhibitor or a negative control (miR-NTC).

Subsequently, RT-qPCR demonstrated that the expression of

miR-206-3p was significantly inhibited following silencing

(Fig. 3F). Furthermore, the SFRP1

expression increased after the miR-206-3p was silenced (Fig. 3G and H). After the transfected BMSCs were

induced to undergo osteogenic differentiation for 7 days,

osteoblast-specific markers (OPN and OCN) were detected by western

blotting. The results demonstrated that the osteogenic ability of

BMSC in the miR-206-3p inhibition group was weaker compared with

the control group (Fig. 3I-K).

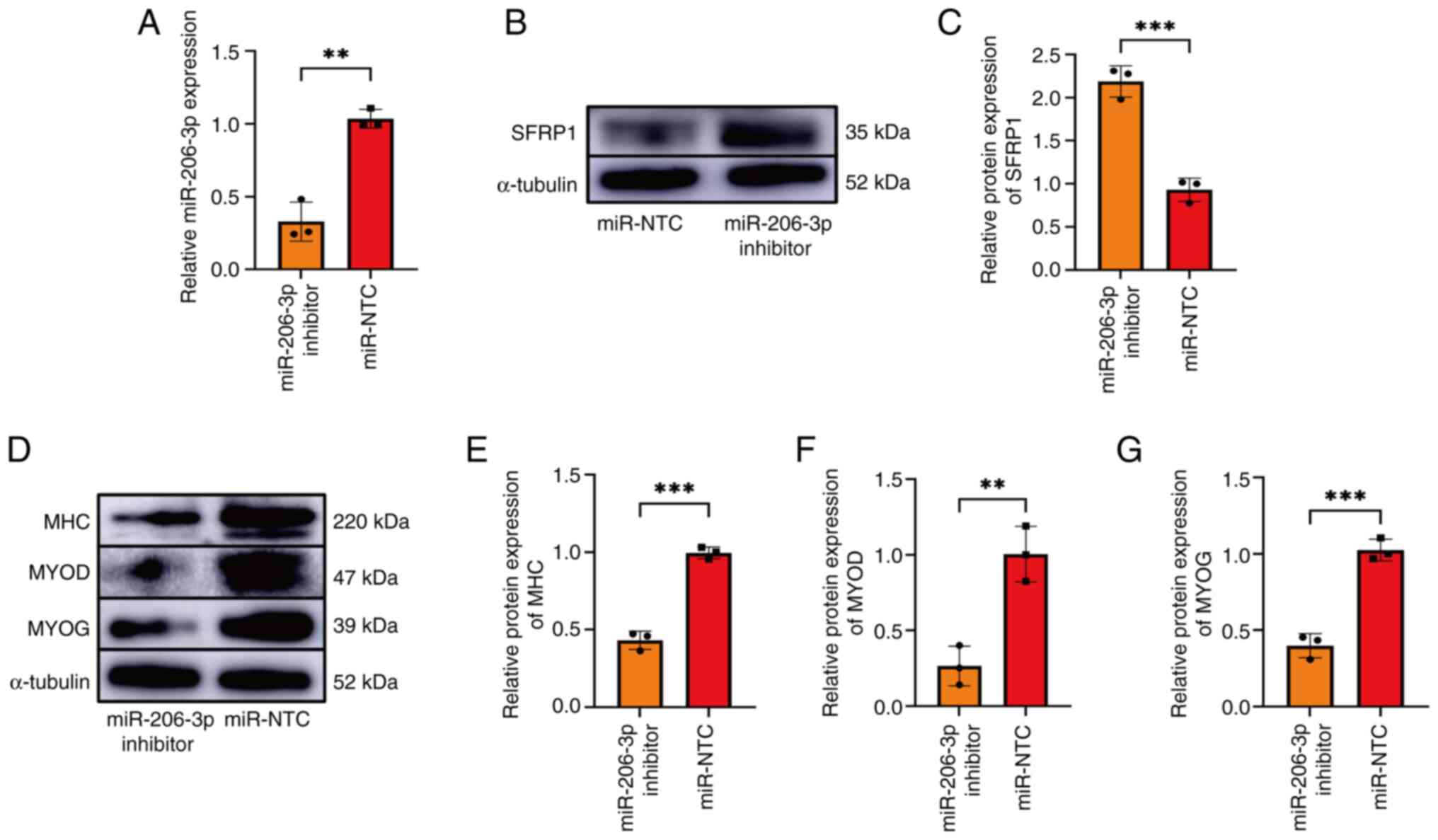

miR-206-3p regulates the myogenic

differentiation of L6 cells by targeting SFRP1

To investigate the role of miR-206-3p in myoblast

differentiation, L6 cells were transfected with an miR-206-3p

inhibitor or miR-NTC at 70% density. Thereafter, RT-qPCR revealed

that compared with the control group, miR-206-3p expression was

significantly inhibited in the miR-206-3p inhibitor group (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, an increase in SFRP1

expression in the miR-206-3p inhibition group was detected

(Fig. 4B and C). Following the induction of myogenic

differentiation in the transfected L6 cells, the expression of

myogenic differentiation 1 decreased in the miR-206-3p inhibition

group. Furthermore, the myogenin and myosin heavy chain expression

levels decreased in the miR-206-3p inhibition group (Fig. 4D-G).

miR-206-3p regulates osteogenic and

myogenic differentiation via the classical β-catenin signaling

pathway

As SFRP1 is the main antagonist of β-catenin

signaling, the expression of GSK-3β, p-GSK-3β, β-catenin and

nuclear β-catenin was detected after transfecting the BMSC and L6

cells. Compared with the control group, the protein levels of

p-GSK-3β and β-catenin were lower (Fig.

5A-D) and nuclear β-catenin was significantly downregulated

(Fig. 5I and J) during the differentiation process in

the miR-206-3p inhibition group. During the myogenesis of L6 cells,

the expression levels of p-GSK-3β, β-catenin (Fig. 5E-H) and nuclear β-catenin decreased

in the miR-206-3p inhibition group (Fig. 5K-L). There was no difference in the

expression of GSK-3β between the inhibition and control groups.

Discussion

miR-206-3p is expressed in a number of cells, such

as skeletal muscle cells, heart cells mesenchymal stem cells and

brown adipocytes, but not in white adipocytes (24,25). A

study in tumor cells proved the specific expression of miR-206-3p

and inhibit cell migration and invasion in various cancers

(26). Bone mineral density is

regulated by osteoclasts and osteoblasts in the bone

microenvironment within the basic multicellular unit, as well as

osteocytes, bone lining cells, osteoma cells and vascular

endothelial cells (27). For

example, miR-206-3p promotes osteogenic differentiation by

negatively regulating BMP3 expression in osteoblasts and can be

transferred to osteoclasts to inhibit osteoclast bone resorption

(28,29). Previous studies have found that a

number of miRNAs have multiple roles in bone diseases; miRNAs play

important regulatory roles in bone formation, bone healing and

osteoblastogenesis and can regulate osteoclastogenesis or enter

them to regulate cell functions (30,31).

Mechanical and chemical crosstalk exist between

muscles and bones (32).

Furthermore, some biochemical pathways, such as Dickkopf-1 and

IL-6, affect both muscle and bone (32,33).

The present study demonstrated that miR-206-3p affected muscle and

bone differentiation by targeting SFRP1 and acting via the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

The present study performed transcriptome sequencing

of the BMSCs in both groups, which revealed that SFRP1 was markedly

elevated in the osteoporosis group. The SFRP gene family has five

members (SFRP1-SFRP5) in the human and mouse genomes and it plays

an important role in the development of cancer and inflammatory

diseases (34). SFRP1 is involved

in bone metabolism and homeostasis. For example, overexpression of

SFRP1 in osteoblasts inhibits the parathyroid hormone-induced bone

formation as well as the differentiation and maturation of

osteoblasts (35). Simultaneously,

SFRP1 plays a role in muscle proliferation and differentiation. For

example, the addition of recombinant Sfrp1 to C2C12 or satellite

cells inhibits muscle duct formation (36). Therefore, identifying the regulatory

factors of the upstream and downstream pathways of SFRP1 may help

determine the therapeutic targets of osteosarcopenia.

The present study hypothesized that miR-206-3p may

bind to SFRP1 and found that SFRP1 and miR-206-3p were negatively

associated in the BMSCs of the OVX and Sham groups. Subsequently, a

DLR assay and transfection experiment indicated that miR-206-3p may

directly target SFRP1 and affect the osteogenic differentiation of

BMSC. This indicated that SFRP1 plays an important role in the

occurrence and development of osteoporosis. These findings are

consistent with a previous study in which miR-206-3p was

demonstrated as a positive regulator of muscle differentiation and

SFRP1 has inhibited myoblast differentiation (37). The present study further

demonstrated that miR-206-3p affected the Wnt pathway by negatively

regulating SFRP1, which promoted the myogenic differentiation of L6

cells.

The SFRPs family includes Wnt signaling antagonists

that play a role in various diseases by regulating Wnt signaling

(38). SFRP1 antagonizes Wnt

signaling by competitively binding to the cysteine-rich Wnt

receptor frizzled (39). The

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is closely associated with bone and

muscle (40). The Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway can regulate bone formation and absorption,

muscle fiber formation and the activation of adult muscle stem

cells (41-43).

The typical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway inhibits the expression

of GSK3β in BMSCs via the low density lipoprotein receptor-related

protein co-receptor and it can promote the nuclear translocation of

β-catenin in the cytoplasm. An increase in the β-catenin-T-cell

factor (TCF) 4/lymphoid enhancer factor-1 (LEF1) complex in the

nucleus activates the transcription of downstream osteogenic genes

(44). In skeletal muscle,

activation of Wnt signaling leads to an increase in the nuclear

translocation of β-catenin. This in turn increases the interaction

of β-catenin with TCF/LEF1 transcription factors, which promotes

the expression of myogenesis-related target genes (45). The present study found that the

protein levels of p-GSK-3β and nuclear β-catenin were significantly

decreased in BMSCs treated with the miR-206-3p inhibitor. However,

in L6 cells treated with the miR-206-3p inhibitor, the protein

levels of p-GSK-3β and nuclear β-catenin were significantly

decreased. These findings indicate that miR-206-3p promotes

β-catenin signaling by negatively regulating SFRP1, which affects

bone and muscle differentiation. This result is consistent with a

previous study (40).

The present study found that mir-206-3p and SFRP1

has indeed been reported in the literature, but it was the first

time to study and report the regulatory relationship between

mir-206-3p, SFRP1 and β-catenin in osteoporosis and sarcopenia at

the same time. The present study has several limitations. First, it

only focused on SFRP1 and its upstream target, miR-206-3p, after

obtaining multiple differential genes via transcriptome sequencing.

However, miR-206-3p may simultaneously affect other target genes

and SFRP1 may be regulated by other miRNAs. Thus, a comprehensive

study on the biological functions of miR-206-3p and SFRP may

provide a deeper understanding of the development of diseases.

Second, the present study used rat BMSCs and the verified myoblasts

L6 cells, which do not fully represent the processes of bone and

muscle formation in humans. Third, rats in the osteoporosis model

group were ovariectomized to mimic postmenopausal osteoporosis in

humans. The present study results need to be verified in studies

with larger samples of human patients with osteoporosis. Mouse

models of accelerated aging have been shown to be important animal

models for studying musculoskeletal aging and related disorders

(46,47). In the future, studies will model

animals in osteosarcopenia and continue to explore the regulatory

pathways of miR-206-3p and SFRP1 genes in osteosarcopenia.

In conclusion, miR-206-3p affects the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway by functionally targeting SFRP1. This in turn

regulates bone and muscle differentiation. Therefore, miR-206-3p

and SFRP1 may be novel targets for the treatment of

osteosarcopenia.

Supplementary Material

Micro-CT images in the (A) Sham group

and (B) OVX group. CT, computed tomography; OVX,

ovariectomized.

Differentiation of bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cells into three cell lines via osteogenesis,

lipogenesis and chondrogenesis. (A) Bone Marrow Stromal Cells. (B)

Alizarin Red staining. (C) Oil Red O staining. (D) Alixin Blue

staining. Scale bars represent (A, C and D) 200 μm and (B)

100 μm.

Flow cytometry identification of

BMSCs. BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells.

Detection of the ability of the cells

to differentiate into bone in the OVX and Sham groups. (A) The

quantitative western blotting results demonstrate that the

expression of (B) OPN and (C) OCN were significantly lower in the

OVX than in the Sham group. Data were analyzed using Student's

t-test (n=3). **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

OVX, ovariectomized; OPN, osteopontin; OCN, osteocalcin.

TargetScan website (http://www.targetscan.org/) prediction that miR-206-3p

directly targets SFRP1 3'UTR. miR, microRNA; SFRP1, secreted

frizzled-related protein 1.

Differentially expressed genes in the

normal and OVX group.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82172442), the Yunnan

Provincial Department of Science and Technology Social Development

Special Project (grant no. 202403AC100003), Major Science and

Technology Special Project of Yunnan Provincial Science and

Technology Program (grant no. 202102AA310042) and Opening Subjects

of Clinical Medical Research Center of the First People's Hospital

of Yunnan Province (grant no. 2022YJZX-GK17).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

CY and ZL jointly conceptualized this study,

designed and conducted experiments and wrote and edited the

manuscript. DY conceived this study, designed and conducted

experiments and edited the manuscript. YL wrote the manuscript and

contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. JF and

YZ designed and implemented the experiment, and wrote the

manuscript. ZP and SL made critical revisions to the manuscript. CY

and SL confirm the authenticity of all raw data. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The experimental animal study protocol was approved

by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Kunming Medical

University, Kunming, China (approval no. kmmu20230916). All animal

experiments and handling were performed in accordance with the

Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the

National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 8523, revised

1985) (22).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kirk B, Zanker J and Duque G:

Osteosarcopenia: Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment-facts and

numbers. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 11:609–618. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Li GH, Cheung CL, Tan KC, Kung AW, Kwok

TC, Lau WC, Wong JS, Hsu WWQ, Fang C and Wong IC: Development and

validation of sex-specific hip fracture prediction models using

electronic health records: a retrospective, population-based cohort

study. EClinicalMedicine. 58(101876)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Yuan S and Larsson SC: Epidemiology of

sarcopenia: Prevalence, risk factors and consequences. Metabolism.

144(155533)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Shimada H, Suzuki T, Doi T, Lee S,

Nakakubo S, Makino K and Arai H: Impact of osteosarcopenia on

disability and mortality among Japanese older adults. J Cachexia

Sarcopenia Muscle. 14:1107–1116. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Locquet M, Beaudart C, Reginster JY and

Bruyère O: Association between the decline in muscle health and the

decline in bone health in older individuals from the SarcoPhAge

cohort. Calcif Tissue Int. 104:273–284. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Clynes MA, Gregson CL, Bruyère O, Cooper C

and Dennison EM: Osteosarcopenia: where osteoporosis and sarcopenia

collide. Rheumatology (Oxford). 60:529–537. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Inoue T, Maeda K, Nagano A, Shimizu A,

Ueshima J, Murotani K, Sato K, Hotta K, Morishita S and Tsubaki A:

Related factors and clinical outcomes of osteosarcopenia: A

narrative review. Nutrients. 13(291)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Prockop DJ: Marrow stromal cells as stem

cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 276:71–74.

1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Loh KM, Chen A, Koh PW, Deng TZ, Sinha R,

Tsai JM, Barkal AA, Shen KY, Jain R, Morganti RM, et al: Mapping

the pairwise choices leading from pluripotency to human bone, heart

and other mesoderm cell types. Cell. 166:451–467. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Yin L, Yang Z, Wu Y, Denslin V, Yu CC, Tee

CA, Lim CT, Han J and Lee EH: Label-free separation of mesenchymal

stem cell subpopulations with distinct differentiation potencies

and paracrine effects. Biomaterials. 240(119881)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Feng Z, Jin M, Liang J, Kang J, Yang H,

Guo S and Sun X: Insight into the effect of biomaterials on

osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells: A review from

a mitochondrial perspective. Acta Biomater. 164:1–14.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Shivdasani RA: MicroRNAs: Regulators of

gene expression and cell differentiation. Blood. 108:3646–3653.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wang E: MicroRNA, the putative molecular

control for mid-life decline. Ageing Res Rev. 6:1–11.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Sun Y, Kuek V, Liu Y, Tickner J, Yuan Y,

Chen L, Zeng Z, Shao M, He W and Xu J: MiR-214 is an important

regulator of the musculoskeletal metabolism and disease. J Cell

Physiol. 234:231–245. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Fariyike B, Singleton Q, Hunter M, Hill

WD, Isales CM, Hamrick MW and Fulzele S: Role of MicroRNA-141 in

the aging musculoskeletal system: A current overview. Mech Ageing

Dev. 178:9–15. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Shang Q, Shen G, Chen G, Zhang Z, Yu X,

Zhao W, Zhang P, Chen H, Tang K, Yu F, et al: The emerging role of

miR-128 in musculoskeletal diseases. J Cell Physiol. 236:4231–4243.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Sun D, Chen Y, Liu X, Huang G, Cheng G, Yu

C and Fang J: miR-34a-5p facilitates osteogenic differentiation of

bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and modulates bone metabolism by

targeting HDAC1 and promoting ER-α transcription. Connect Tissue

Res. 64:126–138. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Wang C, Zhu M, Yang D, Hu X, Wen X and Liu

A: MiR-29a-3p inhibits proliferation and osteogenic differentiation

of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via targeting FOXO3 and

repressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling in steroid-associated

osteonecrosis. Int J Stem Cells. 15:324–333. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wang YC, Yao X, Ma M, Zhang H, Wang H,

Zhao L, Liu S, Sun C, Li P, Wu Y, et al: miR-130b inhibits

proliferation and promotes differentiation in myocytes via

targeting Sp1. J Mol Cell Biol. 13:422–432. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yang L, Qi Q, Wang J, Song C, Wang Y, Chen

X, Chen H, Zhang C, Hu L and Fang X: MiR-452 regulates C2C12

myoblast proliferation and differentiation via targeting

ANGPT1. Front Genet. 12(640807)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

van Rooij E, Liu N and Olson EN: MicroRNAs

flex their muscles. Trends Genet. 24:159–166. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

U.S. Office of Science and Technology

Policy. Laboratory animal welfare; U.S. government principles for

the utilization and care of vertebrate animals used in testing,

research and training; notice. Fed Regist. 50:20864–20865.

1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Townley-Tilson WH, Callis TE and Wang D:

MicroRNAs 1, 133 and 206: critical factors of skeletal and cardiac

muscle development, function and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol.

42:1252–1255. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Walden TB, Timmons JA, Keller P,

Nedergaard J and Cannon B: Distinct expression of muscle-specific

microRNAs (myomirs) in brown adipocytes. J Cell Physiol.

218:444–449. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wu K, Li J, Qi Y, Zhang C, Zhu D, Liu D

and Zhao S: SNHG14 confers gefitinib resistance in non-small cell

lung cancer by up-regulating ABCB1 via sponging miR-206-3p. Biomed

Pharmacother. 116(108995)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kular J, Tickner J, Chim SM and Xu J: An

overview of the regulation of bone remodelling at the cellular

level. Clin Biochem. 45:863–873. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Guo S, Gu J, Ma J, Xu R, Wu Q, Meng L, Liu

H, Li L and Xu Y: GATA4-driven miR-206-3p signatures control

orofacial bone development by regulating osteogenic and

osteoclastic activity. Theranostics. 11:8379–8395. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wang B, Yu P, Li T, Bian Y and Weng X:

MicroRNA expression in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from mice

with steroid-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Mol Med

Rep. 12:7447–7454. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Li H, Zhai Z, Qu X, Xu J, Qin A and Dai K:

MicroRNAs as potential targets for treatment of osteoclast-related

diseases. Curr Drug Targets. 19:422–431. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Li D, Liu J, Guo B, Liang C, Dang L, Lu C,

He X, Cheung HY, Xu L, Lu C, et al: Osteoclast-derived exosomal

miR-214-3p inhibits osteoblastic bone formation. Nat Commun.

7(10872)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Tagliaferri C, Wittrant Y, Davicco MJ,

Walrand S and Coxam V: Muscle and bone, two interconnected tissues.

Ageing Res Rev. 21:55–70. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Bakker AD and Jaspers RT: IL-6 and IGF-1

signaling within and between muscle and bone: How important is the

mTOR pathway for bone metabolism? Curr Osteoporos Rep. 13:131–139.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

van Loon K, Huijbers EJM and Griffioen AW:

Secreted frizzled-related protein 2: A key player in noncanonical

Wnt signaling and tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

40:191–203. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Bodine PVN, Seestaller-Wehr L, Kharode YP,

Bex FJ and Komm BS: Bone anabolic effects of parathyroid hormone

are blunted by deletion of the Wnt antagonist secreted

frizzled-related protein-1. J Cell Physiol. 210:352–357.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Descamps S, Arzouk H, Bacou F, Bernardi H,

Fedon Y, Gay S, Reyne Y, Rossano B and Levin J: Inhibition of

myoblast differentiation by Sfrp1 and Sfrp2. Cell Tissue Res.

332:299–306. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Yang Y, Sun W, Wang R, Lei C, Zhou R, Tang

Z and Li K: Wnt antagonist, secreted frizzled-related protein 1, is

involved in prenatal skeletal muscle development and is a target of

miRNA-1/206 in pigs. BMC Mol Biol. 16(4)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Jiang P, Wei K, Chang C, Zhao J, Zhang R,

Xu L, Jin Y, Xu L, Shi Y, Guo S, et al: SFRP1 negatively modulates

pyroptosis of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis:

A review. front immunol. 13(903475)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Bodine PVN and Komm BS: Wnt signaling and

osteoblastogenesis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 7:33–39.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Yang YJ and Kim DJ: An overview of the

molecular mechanisms contributing to musculoskeletal disorders in

chronic liver disease: Osteoporosis, sarcopenia and osteoporotic

sarcopenia. Int J Mol Sci. 22(2604)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Cossu G and Borello U: Wnt signaling and

the activation of myogenesis in mammals. EMBO J. 18:6867–6872.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Hoeppner LH, Secreto FJ and Westendorf JJ:

Wnt signaling as a therapeutic target for bone diseases. Expert

Opin Ther Targets. 13:485–496. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Boudin E, Fijalkowski I, Piters E and Van

Hul W: The role of extracellular modulators of canonical Wnt

signaling in bone metabolism and diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum.

43:220–240. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Law SM and Zheng JJ: Premise and peril of

Wnt signaling activation through GSK-3β inhibition. iScience.

25(104159)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Shevtsov SP, Haq S and Force T: Activation

of beta-catenin signaling pathways by classical G-protein-coupled

receptors: Mechanisms and consequences in cycling and non-cycling

cells. Cell Cycle. 5:2295–2300. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Yılmaz D, Mathavan N, Wehrle E, Kuhn GA

and Müller R: Mouse models of accelerated aging in musculoskeletal

research for assessing frailty, sarcopenia and osteoporosis-A

review. Ageing Res Rev. 93(102118)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Zhang N, Chow SKH, Leung KS, Lee HH and

Cheung WH: An animal model of co-existing sarcopenia and

osteoporotic fracture in senescence accelerated mouse prone 8

(SAMP8). Exp Gerontol. 97:1–8. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|