Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a significant

global health threat, driving morbidity and mortality worldwide

(1,2). The emergence and spread of

multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria, particularly

carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, Acinetobacter

baumannii (A. baumannii) and Pseudomonas

aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), are of critical concern,

severely limiting therapeutic options for serious infections

(1-4).

The overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics, including carbapenems,

has contributed significantly to this challenge.

In response to this urgent need, new antimicrobial

agents have been developed. Cefiderocol is a novel siderophore

cephalosporin designed to overcome several common resistance

mechanisms in Gram-negative bacteria (3). Its unique mechanism of action,

utilizing bacterial iron transport systems for cell entry, allows

it activity against numerous difficult-to-treat resistant (DTR)

pathogens, including those producing carbapenemases (5,6).

While pivotal clinical trials such as CREDIBLE-CR

(7), APEKS-NP (8) and APEKS-cUTI (9) have provided essential data on

cefiderocol's efficacy and safety in specific patient populations,

understanding its performance in routine clinical practice is

crucial. Real-world settings often involve patients with complex

comorbidities, polymicrobial infections, and prior treatment

failures who may not have been fully represented in trial cohorts

(3).

Therefore, the primary aim of the present study was

to evaluate the real-life efficacy and safety of cefiderocol in

treating patients hospitalized at the University Hospital ‘Gaetano

Martino’ in Messina, Italy. The present study specifically focused

on patients with proven mono- or poly-microbial infections caused

by MDR/DTR Gram-negative bacteria, for whom cefiderocol was

prescribed due to the failure of previous therapeutic lines or the

absence of other suitable antibiotic options. The present

retrospective observational study examines clinical outcomes and

tolerability in this challenging patient population.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

A monocentric, retrospective observational study was

conducted at the University Hospital ‘Gaetano Martino’ in Messina,

Italy, from July 2021 to April 2022. The present study was approved

by the Provincial Ethics Committee of Catania (approval no.

101/CECT2; Catania, Italy), with authorization from the local

institution. All participants provided written informed consent to

participate in the study.

Study objectives

The primary objectives were assessment of

in-hospital mortality and evaluating clinical and/or laboratory

resolution of infection following cefiderocol treatment. The

secondary objectives included: Evaluation of adverse drug reactions

related to cefiderocol, description of hospital epidemiology of MDR

organisms, and analysis of associations between MDR colonization at

admission and subsequent development of healthcare-associated

infections.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Adult patients (≥18 years) who: i) Were hospitalized

at the study center during the observation period; ii) received

cefiderocol for ≥48 h for any suspected or microbiologically

confirmed infection; and iii) had complete medical records and

microbiological data available. Pregnant women, patients who

received cefiderocol for <48 h and patients in whom cefiderocol

was prescribed but not administered were excluded.

Antimicrobial stewardship and

indication for cefiderocol

Cefiderocol use was restricted to the Infectious

Diseases Unit as part of the hospital's antimicrobial stewardship

protocol. It was prescribed in accordance with the drug's technical

sheet and local stewardship guidelines in the following cases:

Confirmed infection by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative organisms

based on antibiogram; and severe infection with strong clinical

suspicion of carbapenem resistance, in the presence of: i)

documented failure of prior carbapenem-based treatment; ii) known

rectal colonization by carbapenem-resistant organisms; and iii)

known endemicity of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in

the treating ward.

Data collection and definitions

Patient data (including demographics, comorbidities,

microbiological results, treatment regimens and outcomes) were

extracted from electronic medical records and Infectious Diseases

consultation logs using a structured Excel database.

Microbiological diagnoses were established via FilmArray PCR panels

and/or standard cultures of relevant biological specimens (for

example, blood, urine and bronchoalveolar lavage). Organisms were

classified as MDR, extensively drug-resistant (XDR), or

pan-drug-resistant (PDR) based on the criteria of Magiorakos et

al (10).

Cefiderocol was administered at 2 g every 8 h

(adjusted in renal impairment), in accordance with the drug's

prescribing information. Clinical success was defined as the

complete resolution or significant improvement of signs, symptoms

and laboratory parameters of infection (for example, normalization

of white blood cell count and C-reactive protein) at the end of

cefiderocol therapy. Clinical failure was defined as death

attributable to the infection, persistence or worsening of

infection-related signs and symptoms, or the need to discontinue

cefiderocol due to a lack of efficacy.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM

SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0 (IBM Corp.). Categorical

variables were summarized as absolute frequencies and percentages,

while continuous variables were assessed for normality using the

Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were expressed as

the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and non-normally distributed

variables were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR).

Group comparisons were conducted using the Chi-square test or

Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, and the unpaired

Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables,

as appropriate.

To explore factors independently associated with

in-hospital mortality, a multivariate logistic regression analysis

was performed, including variables that showed a P<0.10 in

univariate analysis. Results were reported as odds ratios (ORs)

with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Missing data were handled

through case-wise deletion. A two-tailed P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient characteristics

During the study period, cefiderocol was prescribed

to 65 patients. A total of 10 patients were excluded: 8 received

treatment for <48 h, and 2 were not administered the drug.

Therefore, 55 patients were included in the final analysis. A total

of 2 patients received cefiderocol twice (one in separate hospital

admissions, the other during a single admission).

The median age was 65.0 years (IQR 49.0-73.5), and

67.3% were male (n=37). Most patients had severe illness: 43

(78.2%) required intensive care unit (ICU) admission-15 (34.9%)

directly and 28 (65.1%) following transfer from other hospital

wards. Mechanical ventilation was needed in 32 patients (58.2%): 8

(14.6%) received non-invasive and 24 (43.6%) invasive

ventilation.

Infection types

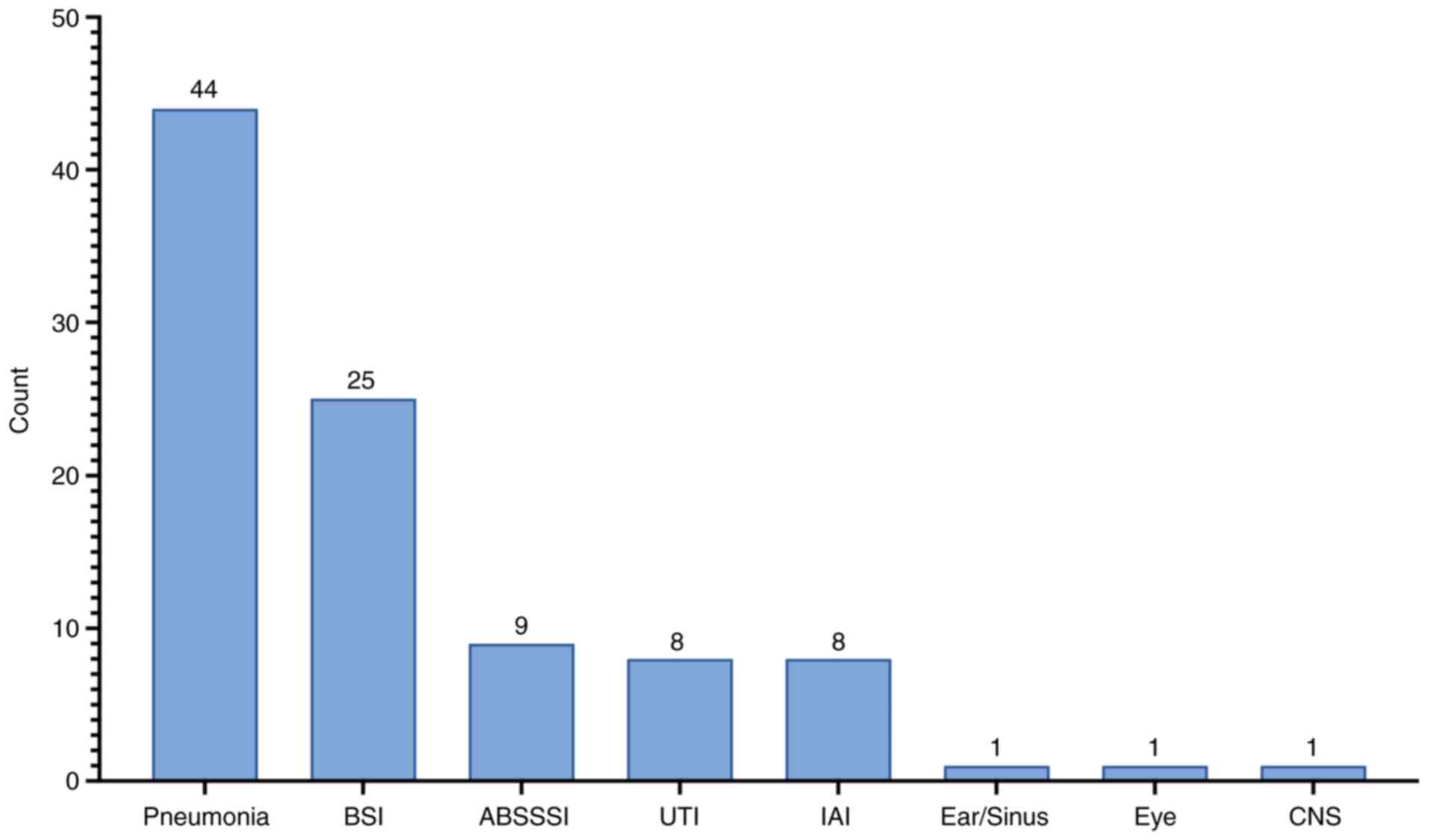

The most common infection treated was pneumonia

(80.0%, n=44), followed by bloodstream infections (BSI; 45.5%,

n=25), acute bacterial skin and soft tissue infections (16.4%,

n=9), intra-abdominal infections (IAI; 14.5%, n=8) and urinary

tract infections (UTI; 14.5%, n=8) (Fig. 1). One patient experienced cystic

fibrosis reactivation.

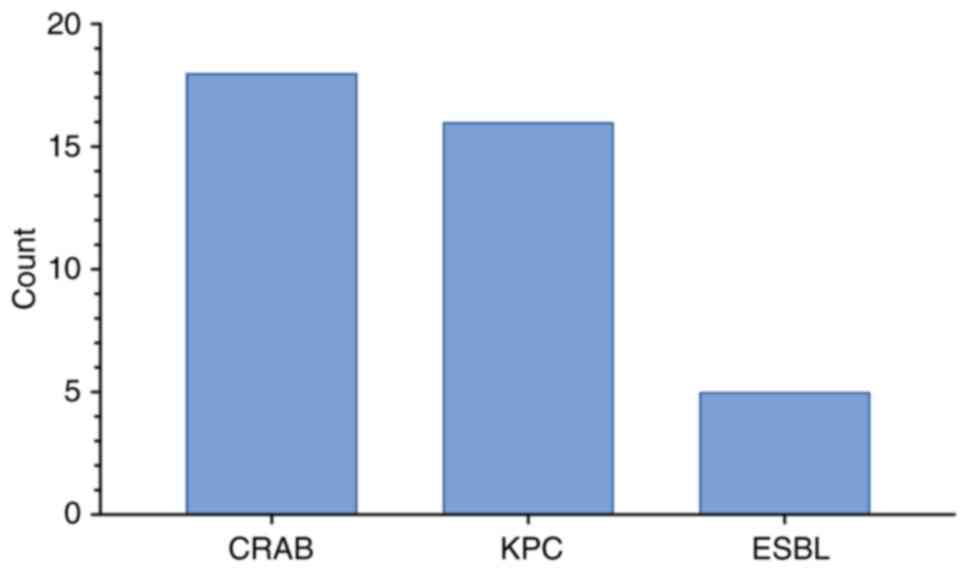

Microbiology and resistance

mechanisms

Among the 55 patients, 48 (87.3%) had confirmed

A. baumannii infection, 73.7% of which were XDR.

Additionally, 5 (10.5%) isolates were possibly PDR, 1 (2.1%) was

confirmed PDR, and 2 (4.2%) were not MDR. A total of 5 isolates

were identified via FilmArray only and not cultured.

Co-infections were frequent: 36 of the A.

baumannii cases involved at least one additional pathogen,

including P. aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae (K.

pneumoniae), Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus

aureus. The most frequently observed resistance profiles were

carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae

carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae and extended-spectrum

beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales (Fig. 2).

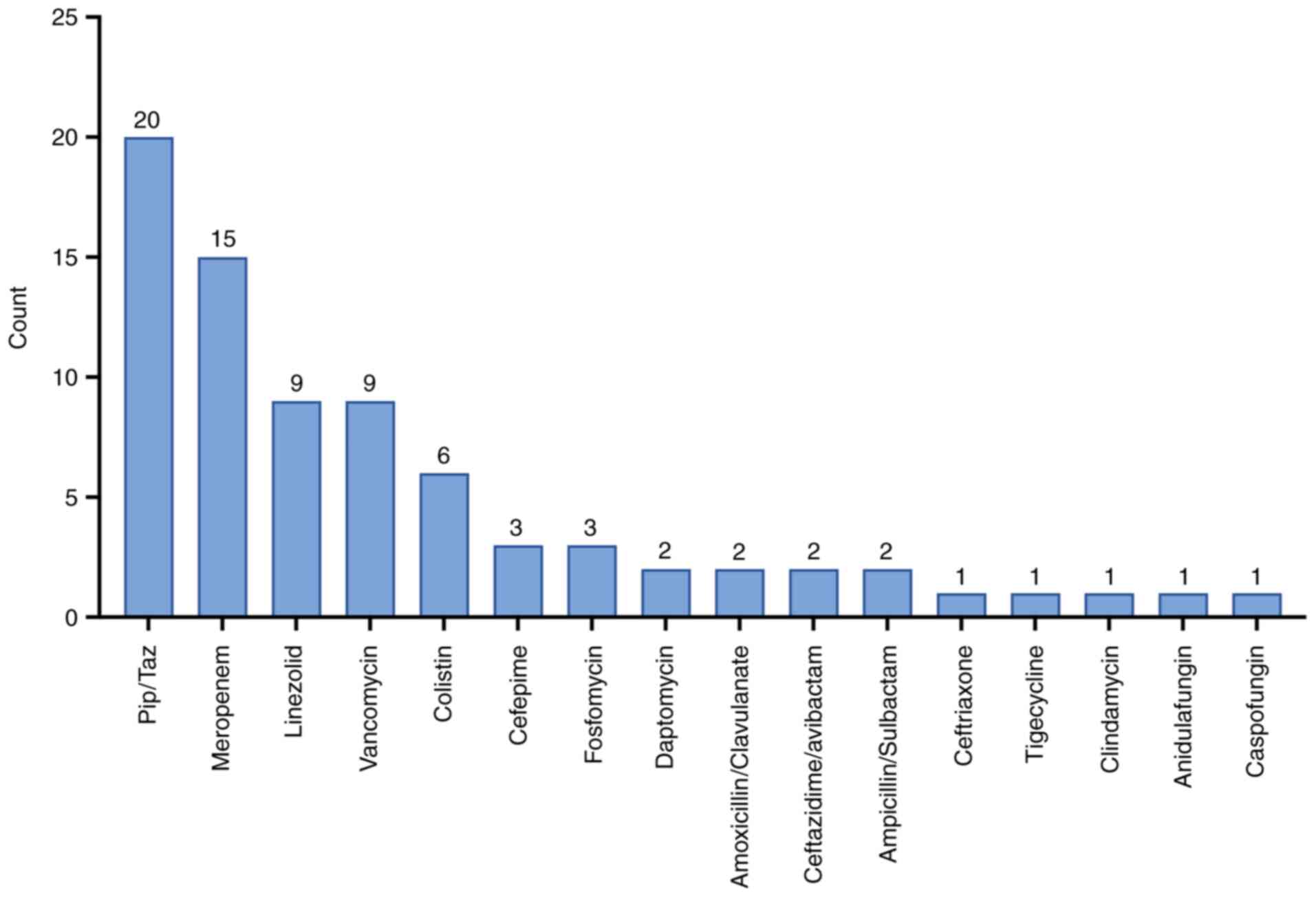

Colonization and prior

antibiotics

A total of 31 patients (57.4%) were colonized with

MDR organisms on admission, based on positive rectal swabs.

Colonization was significantly associated with increased mortality

(P=0.028). Additionally, 40 patients (72.7%) received empiric

in-hospital antibiotics prior to cefiderocol (Fig. 3).

Comorbidities and risk factors

A total of 30 patients (54.5%) had ≥2 comorbidities;

this was not significantly associated with mortality (P=0.126). The

most common comorbidities were cardiovascular disease (67.3%),

COVID-19 (52.7%), lymphopenia (47.3%), thrombocytopenia (34.5%) and

chronic kidney disease (29.1%). The median Charlson Comorbidity

Index was 4, indicating an estimated 10-year survival of 53%

(Table I).

| Table IComorbidities in the population

studied. |

Table I

Comorbidities in the population

studied.

| Comorbidities | n | Percentage % |

|---|

| Cardiovascular

disorder | 37 | 67.3 |

| COVID-19 | 29 | 52.7 |

| Lymphopenia | 26 | 47.3 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 19 | 34.5 |

| Hemodialysis | 17 | 30.9 |

| Chronic kidney

failure | 16 | 29.1 |

| Diabetes | 15 | 27.3 |

| Cancer | 5 | 9.1 |

| Chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease | 5 | 9.1 |

| Neutropenia | 4 | 7.3 |

| Hematologic

cancer | 3 | 5.5 |

| Chronic liver

failure | 2 | 3.6 |

| HIV infection | 1 | 1.8 |

Clinical outcomes

The overall in-hospital mortality was 47.3% (n=26).

Mortality was significantly associated with septic shock (P=0.001)

and MDR colonization (P=0.028), but not with age (P=0.054),

COVID-19 status (P=0.215), or number of comorbidities (P=0.126).

Septic shock occurred in 30 patients (54.5%) with a median duration

of 5 days (IQR 0-15).

Median hospital length of stay was 40 days (IQR

28.5-60.0), significantly shorter in non-survivors (31.5 vs. 57.0

days; P=0.004), likely reflecting early death. Treatment success

(defined as clinical/laboratory improvement) varied by infection

site: ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), 40%; BSI, 66.7%; UTI,

50%; skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI), 100% and IAI, 50%.

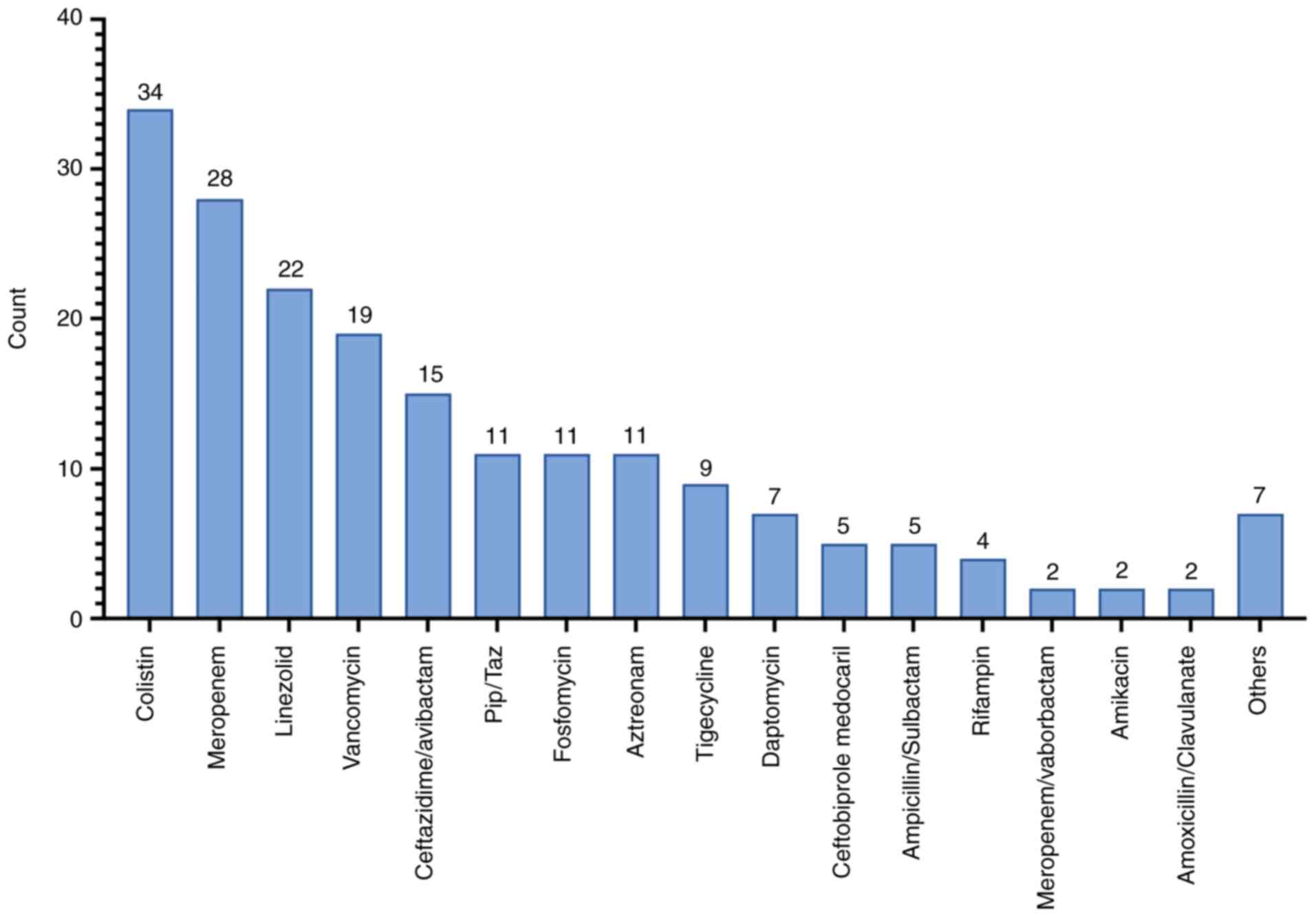

Treatment details and adverse

events

Cefiderocol was administered for a median of 14 days

(IQR 8.1-16.7). Only 2 patients (3.6%) received cefiderocol in

monotherapy. The majority received combination therapy, with

colistin used in 34 cases (61.8%) (Fig.

4). There was no significant difference in mortality between

patients treated with or without colistin (P=0.104). The median

number of antibiotics (excluding cefiderocol) used per patient was

3 (IQR 2-5). No serious cefiderocol-related adverse events were

reported. Minor adverse effects-such as rash, thrombocytopenia,

joint pain and sore throat-occurred in a few patients but did not

lead to drug discontinuation.

Discussion

The present retrospective observational study

evaluated the real-life use of cefiderocol in a critically ill

population infected with MDR Gram-negative bacteria, predominantly

A. baumannii. The current findings suggest that cefiderocol

may be a valuable therapeutic option in patients with limited

treatment alternatives, particularly for bloodstream and soft

tissue infections.

Clinical success was achieved in 66.7% of patients

with BSI, closely aligning with findings from the CREDIBLE-CR trial

(65.5%) (7) and the cohort study by

Falcone et al (11).

Similarly, a 100% success rate in skin and soft tissue infections

(SSTI) mirrors the strong in vitro activity of cefiderocol

against carbapenem-resistant pathogens documented in multiple

studies (12,13). Conversely, the lower efficacy

observed in VAP (40% success) reflects the ongoing challenges in

treating this condition; this high mortality rate highlights an

urgent need for optimized therapeutic strategies for VAP caused by

MDR pathogens. Future studies should investigate whether

alternative dosing regimens, such as prolonged or continuous

infusion of cefiderocol, could improve

pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic target attainment in the lung

parenchyma and lead to improved clinical outcomes (14).

A key finding was that cefiderocol was predominantly

used as part of a combination regimen (96.4%), with colistin being

the most frequent partner antibiotic. This reflects a common

clinical practice in treating severe infections caused by XDR

pathogens such as A. baumannii, where combination therapy is

often employed to achieve potential synergistic effects and

mitigate the risk of resistance development (15,16).

While the addition of colistin did not show a statistically

significant mortality benefit in our analysis (P=0.104), the choice

is often guided by the severity of illness and local resistance

patterns, despite ongoing debates regarding colistin's efficacy and

potential toxicity, particularly its limited pulmonary

penetration.

The microbiological landscape in our cohort was

dominated by A. baumannii (87.3%), a significantly higher

prevalence than in previous trials such as CREDIBLE-CR (46%)

(7), APEKS-NP (16%) (8) and Meschiari et al (5.9%)

(17). The high rate of ICU

admission and mechanical ventilation suggest these infections were

primarily nosocomial, with VAP being a major source.

Notably, over 70% of the isolates were classified as

XDR, with several cases potentially PDR. These findings emphasize

the severity of infections managed in our setting and underscore

the urgent need for effective antimicrobial options.

Septic shock was observed in 54.5% of patients and

was significantly associated with mortality (P=0.001), consistent

with global data estimating sepsis-related mortality at 30-40%

(18). Colonization with MDR

organisms at admission also associated with worse outcomes

(P=0.028), highlighting the prognostic value of routine rectal

swabs and active surveillance cultures in ICU settings.

The present study also sheds light on the

positioning of cefiderocol in clinical practice. The indications

for its use included both microbiologically confirmed infections

and cases of strong clinical suspicion based on risk factors such

as known colonization. This suggests a role for cefiderocol not

only as a targeted therapy for confirmed DTR pathogens but also as

a highly selective empiric option in critically ill patients with a

high pre-test probability of having such an infection, particularly

when prior broad-spectrum antibiotics have failed.

Cefiderocol demonstrated favorable tolerability in

our cohort, with no serious adverse effects leading to

discontinuation. Minor side effects (for example, rash,

thrombocytopenia and myalgia) were infrequent and self-limiting.

This safety profile aligns with published studies from randomized

trials and pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic studies (7,19). Our

findings are broadly consistent with prior clinical trials and

real-world studies (20-24).

Despite these encouraging observations, the present

study has important limitations. Its retrospective, single-center

nature limits external validity and introduces selection bias. The

absence of detailed molecular resistance testing (such as16S rRNA

sequencing) and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) data

restricts our ability to correlate outcomes with specific

resistance mechanisms and precise susceptibility profiles.

Additionally, the lack of a comparator arm precludes evaluation of

cefiderocol's relative efficacy. Lastly, the small sample size,

particularly within infection subgroups, limits the statistical

power of some analyses.

Furthermore, due to the retrospective data

collection, the precise timing of cefiderocol initiation relative

to hospital admission or infection onset could not be consistently

determined, although it was generally used after failure of prior

therapies. Lastly, the small sample size, particularly within

infection subgroups, limits the statistical power of some analyses.

Nevertheless, our study adds valuable real-life evidence to the

increasing body of literature supporting cefiderocol use in

critically ill patients with few alternative treatment options. In

particular, its observed efficacy in BSI and SSTI, combined with

its tolerability, support its consideration in the management of

infections caused by XDR A. baumannii and other MDR

Gram-negative bacteria (25).

Future prospective, multicenter studies are needed to further

define optimal patient selection, combination therapy strategies,

and the potential for resistance emergence. Moreover, long-term

strategies to combat AMR will require a multifaceted approach,

including robust antimicrobial stewardship, infection control, and

the exploration of novel therapeutic paradigms beyond conventional

antibiotics.

In conclusion, in the present real-life,

retrospective study involving critically ill patients with

infections caused by MDR Gram-negative bacteria-primarily A.

baumannii-cefiderocol demonstrated promising efficacy and

favorable tolerability, particularly in bloodstream and soft tissue

infections. Despite the complexity of the cohort, which included a

high prevalence of septic shock, ICU admission and XDR pathogens,

clinical outcomes were comparable to those observed in controlled

trials and recent observational data. Colonization with MDR

organisms and septic shock were independently associated with

higher mortality, emphasizing the importance of early

identification and targeted antimicrobial therapy in high-risk

settings. Cefiderocol was well tolerated, with no serious adverse

events reported, further supporting its use in fragile and

treatment-limited populations. While the retrospective,

single-center design and lack of MIC data limit the

generalizability of the present findings, our results contribute to

the increasing body of real-world evidence supporting the role of

cefiderocol as a valuable treatment option in severe infections

caused by DTR Gram-negative bacteria. Future prospective,

multicenter studies are needed to define optimal therapeutic

strategies, including the role of combination therapy and

resistance prevention.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AM, EVR and GFP conceived the study. AM, EVR, CI and

GN designed the study. MV, CM, MC and AEC collected the data. EVR

and YR analyzed data. AM and EVR wrote the manuscript. GN and GFP

reviewed the manuscript. GFP and CI supervised the study. All

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. AM

and GN confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All participants provided written informed consent

to participate in the study. The present study was conducted in

accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the

Provincial Ethics Committee of Catania (approval no. 101/CECT2;

Catania, Italy).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Marino A, Maniaci A, Lentini M, Ronsivalle

S, Nunnari G, Cocuzza S, Parisi FM, Cacopardo B, Lavalle S and La

Via L: The Global burden of multidrug-resistant bacteria.

Epidemiologia (Basel). 6(21)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Tiseo G, Galfo V, Carbonara S, Marino A,

Di Caprio G, Carretta A, Mularoni A, Mariani MF, Maraolo AE, Scotto

R, et al: Bacteremic nosocomial pneumonia caused by Gram-negative

bacilli: Results from the nationwide ALARICO study in Italy.

Infection. 53:1041–1050. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Giacobbe DR, Labate L, Russo Artimagnella

C, Marelli C, Signori A, Di Pilato V, Aldieri C, Bandera A, Briano

F, Cacopardo B, et al: Use of cefiderocol in adult patients:

Descriptive analysis from a prospective, multicenter, cohort study.

Infect Dis Ther. 13:1929–1948. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators.

Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A

systematic analysis. Lancet. 399:629–655. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Stracquadanio S, Nicolosi A, Marino A,

Calvo M and Stefani S: Issues with cefiderocol testing: Comparing

commercial methods to broth microdilution in iron-depleted

medium-analyses of the performances, ATU, and trailing effect

according to EUCAST initial and revised interpretation criteria.

Diagnostics (Basel). 14(2318)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Stracquadanio S, Nicolosi A, Privitera GF,

Massimino M, Marino A, Bongiorno D and Stefani S: Role of

transcriptomic and genomic analyses in improving the comprehension

of cefiderocol activity in Acinetobacter baumannii. mSphere.

9(e0061723)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Bassetti M, Echols R, Matsunaga Y, Ariyasu

M, Doi Y, Ferrer R, Lodise TP, Naas T, Niki Y, Paterson DL, et al:

Efficacy and safety of cefiderocol or best available therapy for

the treatment of serious infections caused by carbapenem-resistant

Gram-negative bacteria (CREDIBLE-CR): a randomised, open-label,

multicentre, pathogen-focused, descriptive, phase 3 trial. Lancet

Infect Dis. 21:226–240. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wunderink RG, Matsunaga Y, Ariyasu M,

Clevenbergh P, Echols R, Kaye KS, Kollef M, Menon A, Pogue JM,

Shorr AF, et al: Cefiderocol versus high-dose, extended-infusion

meropenem for the treatment of Gram-negative nosocomial pneumonia

(APEKS-NP): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority

trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 21:213–225. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Portsmouth S, van Veenhuyzen D, Echols R,

Machida M, Ferreira JCA, Ariyasu M, Tenke P and Den Nagata T:

Cefiderocol versus imipenem-cilastatin for the treatment of

complicated urinary tract infections caused by Gram-negative

uropathogens: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority

trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 18:1319–1328. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB,

Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter

G, Olsson-Liljequist B, et al: Multidrug-resistant, extensively

drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international

expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired

resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 18:268–281. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Falcone M, Tiseo G, Nicastro M, Leonildi

A, Vecchione A, Casella C, Forfori F, Malacarne P, Guarracino F,

Barnini S and Menichetti F: Cefiderocol as Rescue Therapy for

Acinetobacter baumannii and Other Carbapenem-resistant

Gram-negative Infections in Intensive Care Unit Patients. Clin

Infect Dis. 72:2021–2024. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Liu PY, Ko WC, Lee WS, Lu PL, Chen YH,

Cheng SH, Lu MC, Lin CY, Wu TS, Yen MY, et al: In vitro activity of

cefiderocol, cefepime/enmetazobactam, cefepime/zidebactam,

eravacycline, omadacycline, and other comparative agents against

carbapenem-non-susceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Acinetobacter baumannii isolates associated from bloodstream

infection in Taiwan between 2018-2020. J Microbiol Immunol Infect.

55:888–895. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Bianco G, Boattini M, Comini S, Iannaccone

M, Casale R, Allizond V, Babrbui AM, Banche G, Cavallo R and Costa

C: Activity of ceftolozane-tazobactam, ceftazidime-avibactam,

meropenem-vaborbactam, cefiderocol and comparators against

Gram-negative organisms causing bloodstream infections in Northern

Italy (2019–2021): emergence of complex resistance phenotypes. J

Chemother. 34:302–310. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Jabbour JF, Sharara SL and Kanj SS:

Treatment of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative skin and soft tissue

infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 33:146–154. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Palermo G, Medaglia AA, Pipitò L, Rubino

R, Costantini M, Accomando S, Giammanco GM and Cascio A:

Cefiderocol efficacy in a real-life setting: Single-centre

retrospective study. Antibiotics (Basel). 12(746)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Clancy CJ, Cornely OA, Slover CM, Nguyen

ST, Kung FH, Verardi S, Longshaw CM, Marcella S and Cai B: P-1475.

Real-world effectiveness and safety of cefiderocol in the treatment

of patients with serious Gram-negative bacterial infections:

Results of the PROVE chart review study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 12

(Suppl 1)(ofae631.1645)2025.

|

|

17

|

Meschiari M, Volpi S, Faltoni M, Dolci G,

Orlando G, Franceschini E, Menozzi M, Sarti M, Del Fabro G,

Fumarola B, et al: Real-life experience with compassionate use of

cefiderocol for difficult-to-treat resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

(DTR-P) infections. JAC Antimicrobial Resist.

3(dlab188)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Bauer M, Gerlach H, Vogelmann T, Preissing

F, Stiefel J and Adam D: Mortality in sepsis and septic shock in

Europe, North America and Australia between 2009 and 2019- results

from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care.

24(239)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Azanza Perea JR and Sádaba Díaz de Rada B:

Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics and tolerability of cefiderocol

in the clinical setting. Rev Esp Quimioter. 35 (Suppl 2):S28–S34.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Hsueh SC, Chao CM, Wang CY, Lai CC and

Chen CH: Clinical efficacy and safety of cefiderocol in the

treatment of acute bacterial infections: A systematic review and

meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Glob Antimicrob

Resist. 24:376–382. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Theriault N, Tillotson G and Sandrock CE:

Global travel and Gram-negative bacterial resistance; implications

on clinical management. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 19:181–196.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Paterson DL, Kinoshita M, Baba T, Echols R

and Portsmouth S: Outcomes with cefiderocol treatment in patients

with Bacteraemia enrolled into prospective phase 2 and phase 3

randomised clinical studies. Infect Dis Ther. 11:853–870.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Wright H, Harris PNA, Chatfield MD, Lye D,

Henderson A, Harris-Brown T, Donaldson A and Paterson DL:

Investigator-driven randomised controlled trial of cefiderocol

versus standard therapy for healthcare-associated and

hospital-acquired Gram-negative bloodstream infection: Study

protocol (the GAME CHANGER trial): Study protocol for an

open-label, randomised controlled trial. Trials.

22(889)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Schmid H, Brown LK, Indrakumar B,

McGarrity O, Hatcher J and Bamford A: Use of cefiderocol in the

management of children with infection or colonization with

multi-drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria: A retrospective,

single-center case series. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 43:772–776.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Marino A, Augello E, Stracquadanio S,

Bellanca CM, Cosentino F, Spampinato S, Cantarella G, Bernardini R,

Stefani S, Cacopardo B and Nunnari G: Unveiling the secrets of

Acinetobacter baumannii: Resistance, current treatments, and

future innovations. Int J Mol Sci. 25(6814)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|