Introduction

In 2023, the term used to replace non-alcoholic

fatty liver disease was metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic

liver disease (MASLD) (1). A new

category, outside pure MASLD, termed metabolic and alcohol

related/associated liver disease (MetALD), was selected to describe

those with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver

disease. This included patients who consume greater amounts of

alcohol per week (140-350 g/week and 210-420 g/week for women and

men, respectively). Within the MetALD group, there is a continuum

across which the contribution of MASLD and alcohol-associated

(alcohol-related) liver disease (ALD) varies. Part of the renaming

of steatotic liver disease (SLD) is intended to define MetALD as a

specific disease; however, there are no drugs for the treatment of

MetALD as a separate disease (2).

Furthermore, metabolic risk factors and alcohol often coexist in

the same individual, and a synergistic effect of the interaction

markedly increasing the risk of liver disease has been elucidated

in recent years (3). Subsequent

studies investigated the prevalence of MetALD, which ranges from

1.7-17% in the total cohort (3). A

few cohort studies have also assessed the prognosis of this patient

population, with preliminary data suggesting that MetALD has an

intermediate risk of liver fibrosis, decompensation and mortality

among the SLD subtypes (3). MASLD

and alcohol consumption are independent risk factors for recurrence

after endoscopic treatment of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

(4). The therapeutic significance

of diagnosing MetALD separately from MASLD and ALD remains

unclear.

In patients with MASLD, 7 to 10% weight loss occurs

at the beginning of the lifestyle improvement algorithm (5). The next step in the algorithm is to

increase physical activity; at least 150 min/week of

moderate-intensity physical activity or 75 min/week of

vigorous-intensity physical activity is recommended (5). Alcohol consumption is discouraged, or

abstinence is recommended in cases of advanced fibrosis or

cirrhosis (5). MetALD is an

overlapping disease of MASLD and ALD, and lifestyle changes are

required (2,3). However, the relationship among reduced

alcohol consumption, additional exercise, and weight loss in

patients with MetALD in terms of treatment efficacy remains

unclear.

In adults with MASLD, non-invasive scores based on

combinations of blood tests or combinations of blood tests with

imaging techniques measuring mechanical properties and/or hepatic

fat content should be used for the detection of fibrosis since their

diagnostic accuracy is higher than standard liver enzyme testing

[alanine (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST)] (5). With the vibration-controlled transient

elastography, liver stiffness (LS) measurement and controlled

attenuation parameter (CAP) values are determined, which allow for

a relatively reliable estimation of the degree of fibrosis and

steatosis, respectively (5). Mac-2

binding protein glycosylation isomer (M2BPGi) has favorable

diagnostic performance for significant and extensive fibrosis in

patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and is an

effective, non-invasive and convenient marker (6). In the present study, lifestyle changes

(weight loss, additional exercise and abstinence from alcohol) were

introduced in patients with MASLD and MetALD, and changes in liver

fibrosis were assessed after 6 months using M2BPGi and LS as

noninvasive tests (NIT).

Materials and methods

Patients

The present study included 100 patients with MASLD

and MetALD who had visited liver disease outpatient clinic in

Nagasaki Harber Medical center between June 2017 and January 2024

for the first time (Table IA). Of

the 100 patients, 70 were women and 30 men. The median age of the

patients was 63 years (range: 83-18 years). These patients did not

include any cases that were anti-HCV antibody positive or HBs

antigen positive. Diagnostic criteria for MASLD and MetALD were

established as previously described (1). A total of 67 patients with MASLD and

33 patients with MetALD were retrospectively evaluated after six

months of lifestyle changes (weight loss, abstinence, and exercise)

(Table IB). The medical records of

100 patients were retrospectively reviewed. All laboratory

measurements were obtained from medical records. Hypertensive

patients (HT) were defined as those who had been taking

antihypertensive medication for at least six months prior to their

visit to our department. Patients with hyperlipidemia (HL) were

defined as those with a fasting low-density lipoprotein (LDL)

cholesterol level of 140 mg/dl or higher or a TG level of 150 mg/dl

or higher. Patients receiving statin therapy were included in the

HL group; however, those receiving fibrate therapy were excluded.

The diabetes group (diabetes mellitus; DM) consisted of patients

with fasting serum glucose ≥100 mg/dl or HbA1c ≥5.7%, or with a

diagnosis of type 2 diabetes or being treated for type 2 diabetes.

The DM group did not include patients treated with sodium-glucose

cotransporter 2 inhibitors, incretin preparations containing

glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists, or metformin.

| Table IClinical characteristics. |

Table I

Clinical characteristics.

| A, Base line |

|---|

| | MASLD | MetALD | P-value |

|---|

| Sex | | | |

|

Female | 55 (82.1) | 15 (45.5) | 0.00017 |

|

Male | 12 (17.9) | 18 (54.5) | |

| Age, years | | | |

|

N | 67 | 33 | 0.38905 |

|

Me

(Q1~Q3) | 62.8

(51.6~71.6) | 65.1

(55.3~70.9) | |

| ALDG | | | |

|

0 | 62 (92.5) | 0 (0.0) | <0.00001 |

|

Alcoholic

consumption | 5 (7.5) | 33 (100.0) | |

| BMIG | | | |

|

Normal | 3 (4.5) | 5 (15.2) | 0.11092 |

|

Obesity | 64 (95.5) | 28 (84.8) | |

| BMI | | | |

|

N | 67 | 33 | 0.22226 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | 27.2 (25.8,

30.1) | 27.3 (24.1,

29.8) | |

| AST | | | |

|

N | 67 | 33 | 0.68677 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | 56.0 (36.0,

84.5) | 56.0 (30.0,

78.5) | |

| ALT | | | |

|

N | 67 | 33 | 0.13190 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | 71.0 (43.5,

112.8) | 61.0 (38.5,

81.0) | |

| PLT | | | |

|

N | 67 | 33 | 0.03602 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | 22.0 (19.1,

25.38) | 18.0 (14.58,

24.30) | |

| FIB-4 | | | |

|

N | 67 | 33 | 0.02465 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | 1.658 (1.20,

2.639) | 2.279 (1.807,

3.459) | |

| LS | | | |

|

N | 66 | 32 | 0.02615 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | 6.50 (5.00,

8.70) | 7.90 (6.35,

12.55) | |

| CAP | | | |

|

N | 66 | 32 | 0.06396 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | 318.5 (290,

341) | 288.5 (270,

340) | |

| M2BPGi | | | |

|

N | 66 | 33 | 0.01600 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | 0.880 (0.620,

1.210) | 1.110 (0.835,

2.538) | |

| HT | | | |

|

HT | 24 (35.8) | 17 (51.5) | 0.13350 |

|

none | 43 (64.2) | 16 (48.5) | |

| HT | | | |

|

HL | 25 (37.3) | 10 (30.3) | 0.48950 |

|

None | 42 (62.7) | 23 (69.7) | |

| DM | | | |

|

None | 50 (74.6) | 24 (72.7) | 0.83864 |

|

DM | 17 (25.4) | 9 (27.3) | |

| B, Change of

lifestyle |

| | MASLD | MetALD | P-value |

| Exercise | | | |

|

N | 67 | 33 | 0.77342 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | 0.5 (0.0, 1.0) | 0.5 (0.0, 1.0) | |

| Exercise G | | | |

|

Ex | 47 (70.1) | 23 (69.7) | 0.96299 |

|

None | 20 (29.9) | 10 (30.3) | |

| Nutritional

Guidance | | | |

|

Done | 38 (56.7) | 10 (30.3) | 0.01292 |

| Abstinence | | | |

|

Abstinence | 1 (20.0) | 11 (33.3) | 1.00000 |

|

None | 4 (80.0) | 22 (66.7) | |

| dBW% | | | |

|

N | 67 | 33 | 0.18334 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | -3.52 (-6.24,

-1.20) | -2.32 (-5.98,

0.70) | |

| dBW% G1 | | | |

|

G1 | 17 (25.4) | 9 (27.3) | 0.83864 |

|

G2-4 | 50 (74.6) | 24 (72.7) | |

| dBW% G12/34 | | | |

|

G1, 2 | 36 (53.7) | 14 (42.4) | 0.28762 |

|

G3, 4 | 31 (46.3) | 19 (57.6) | |

| dBW% G | | | |

|

G1 | 17 (25.4) | 8 (24.2) | 0.51125 |

|

G2 | 19 (28.4) | 6 (18.2) | |

|

G3 | 17 (25.4) | 8 (24.2) | |

|

G4 | 14 (20.9) | 33.3 | |

| C, Change of

clinical factors |

| | MASLD | MetALD | P-value |

| dAST | | | |

|

N | 67 | 33 | 0.82019 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | -15.0 (-36.8,

0.0) | -13.0 (-37.0,

-2.0) | |

| dALT | | | |

|

N | 67 | 33 | 0.57236 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | -24.0 (-51.8,

-4.3) | -17.0 (-43.5,

-3.0) | |

| dPLT | | | |

|

N | 67 | 33 | 0.39098 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | -0.7 (-2.8,

1.0) | -0.3 (-1.7,

1.7) | |

| dLS | | | |

|

N | 66 | 32 | 0.66030 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | -0.7 (-2.2,

0.7) | -0.8 (-2.5,

0.6) | |

| dLSG | | | |

|

Decrease | 44 (66.7) | 21 (65.6) | 0.91850 |

|

Increase | 22 (33.3) | 11 (34.4) | |

| dCAP | | | |

|

N | 66 | 32 | 0.77922 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | -21.5 (-61.0,

11.0) | -23.0 (-60.0,

-2.0) | |

| dM2BPGi | | | |

|

N | 61 | 30 | 0.40795 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | 0.0 (-0.2,

0.1) | -0.1 (-0.4,

0.2) | |

| dM2BG | | | |

|

Decrease | 27 (44.3) | 16 (53.3) | 0.41519 |

|

Increase | 34 (55.7) | 14 (46.7) | |

| dFIB-4 | | | |

|

N | 67 | 33 | 0.34621 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | -0.1 (-0.4,

0.1) | -0.3 (-0.7,

0.3) | |

| dFIBG | | | |

|

Decrease | 41 (61.2) | 21 (63.6) | 0.81297 |

|

Increase | 26 (38.8) | 12 (36.4) | |

For lifestyle modification, the patients were

instructed to lose weight, abstain from alcohol, and increase

exercise (Table IB). All patients

with MASLD and MetALD were advised to add at least 30 min of

walking daily and were instructed to increase their walking speed

as they became accustomed to walking. Exercise was defined as 100%

of 30 min of walking; if less, the self-reported walking time was

divided by 30 min and expressed as a percentage. The exercise +

(Ex+) group was able to add any degree of exercise, while the None

group did not add any exercise. Nutritional guidance was

recommended to all patients except those who did not request it.

Nutritional guidance was provided by a dietitian with the goal of a

10% reduction in weight at the time of intervention to 25 calories

per target weight (kg). All patients were instructed to abstain

from alcohol; those who stopped drinking were defined as abstinent,

and those who drank less were defined as the reduced drinking

group. The abstinence period is six months, as is the observation

period. Abstinence was recommended at the first visit, total or

partial abstinence was confirmed at two weeks later, and alcohol

consumption was checked again at the final assessment six months

later. The AbEx group comprised of an Ex+ group and an

abstinence group. Patients were weighed at least once daily,

snacking and soft drinks were stopped, and had a goal of losing 10%

of their body weight in one year. Decreased body weight (dBW%) is

calculated as follows: (BW at entry-BW at 0.5 year after)/BW at

entry. BW decrease rate groups (dBWG) were divided by quartiles of

dBW% as follows: G1, -6.1%>; G2, -6.1 to -3.1; G3, -3.1 to

-0.77; G4, -0.77< (Fig.

S1A).

Informed consent was obtained from each patient

included in the study and they were guaranteed the right to leave

the study if desired. The study protocol conformed to the 1975

Declaration of Helsinki guidelines (7) and was approved by the Human Research

Ethics Committee of Nagasaki Harbor Medical Center (approval no.

H30-031; Nagasaki, China).

Laboratory measurements

At the start of change of lifestyle and 0.5 years

later, platelet [(PLT): M, 13.1-26.2; F, 13-36.9 X

104/µl], AST (10-40 U/l), ALT (5-40 U/l) and M2BPGi

[1> cut off index (C.O.I.)] levels were evaluated. Fibrosis-4

(FIB-4) levels were calculated based on age and AST, ALT and PLT

levels (8). Overall, 98 patients

were evaluated using FibroScan. LS (kPa) was evaluated using

vibration-controlled transient elastography, and liver fat content

(dB/m) was evaluated using the controlled attenuation parameter

(CAP). ‘d’ is the difference between baseline and endpoint

(Table IC). A decrease in liver

fibrosis (a decrease in dLSM2B) was defined as a reduction in LS

(dLS) using FibroScan and M2BPGi (dM2B) during the observation

period.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using StatFlex (version 6.0;

Artech Co., Ltd.) and presented as median and 95% confidence

intervals (CI). Laboratory variables were compared using

Mann-Whitney U tests (for differences between the two groups) and

χ2 tests. The detection level was analyzed using

receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Correlations were evaluated based on Pearson's correlation

coefficient (R). A multivariate analysis was performed using

logistic regression.

Results

Difference between MASLD and

MetALD

Patients with MetALD were more likely to be men and

had higher FIB-4, LS, and M2BPGi scores than those with MASLD

(Table IA). There were no

significant differences in age, body mass index (BMI), HT, HL, or

DM. Nutritional guidance interventions were more common in patients

with MASLD; however, exercise and dBW% did not differ significantly

(Table IB). The rate of abstinence

due to MetALD was 33.3%. No differences were found between the

MASLD and MetALD groups with respect to changes in clinical factors

(Table IC).

Weight loss is associated with a

decrease in liver fibrosis in patients with MASLD, but no

association can be observed in patients with MetALD

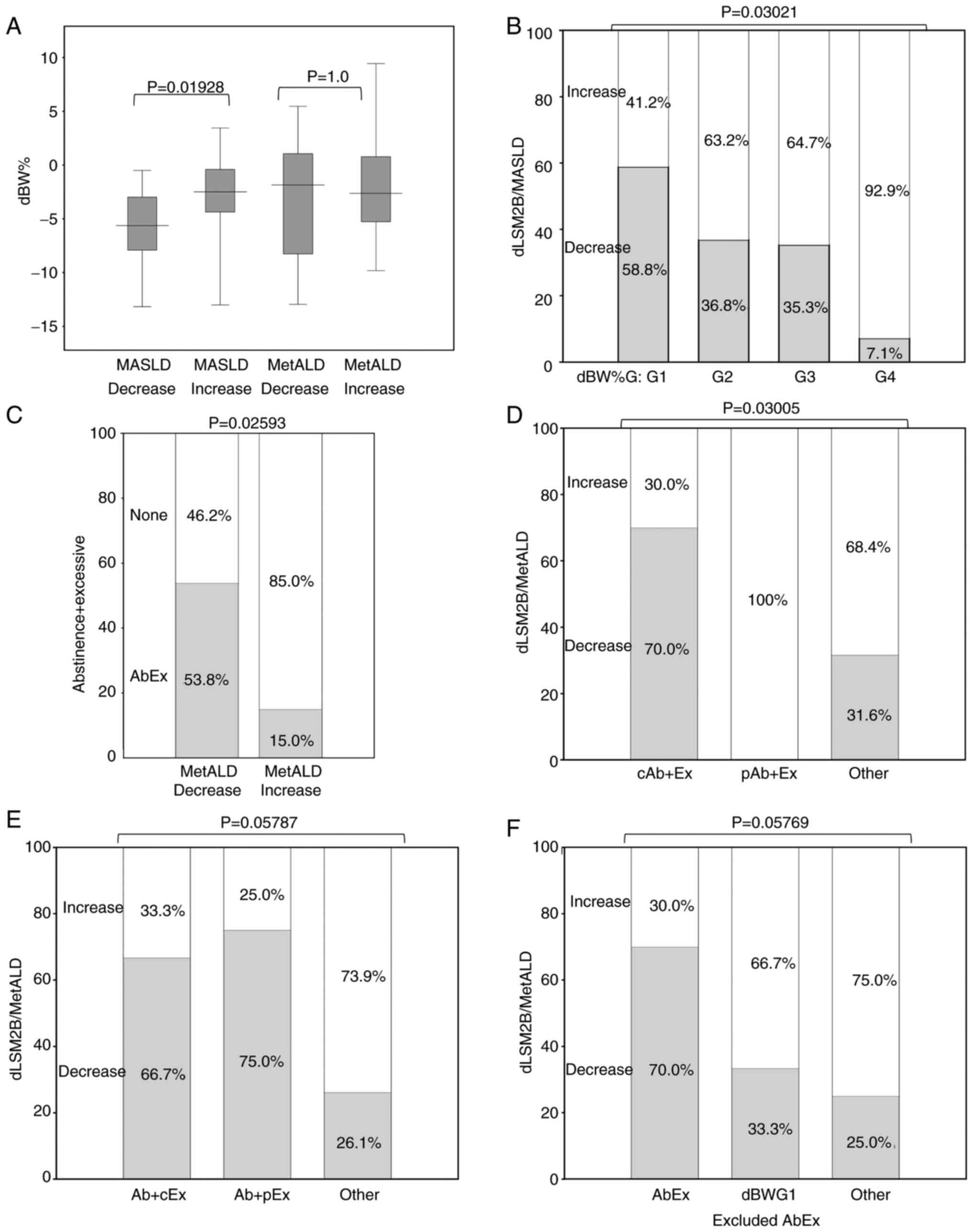

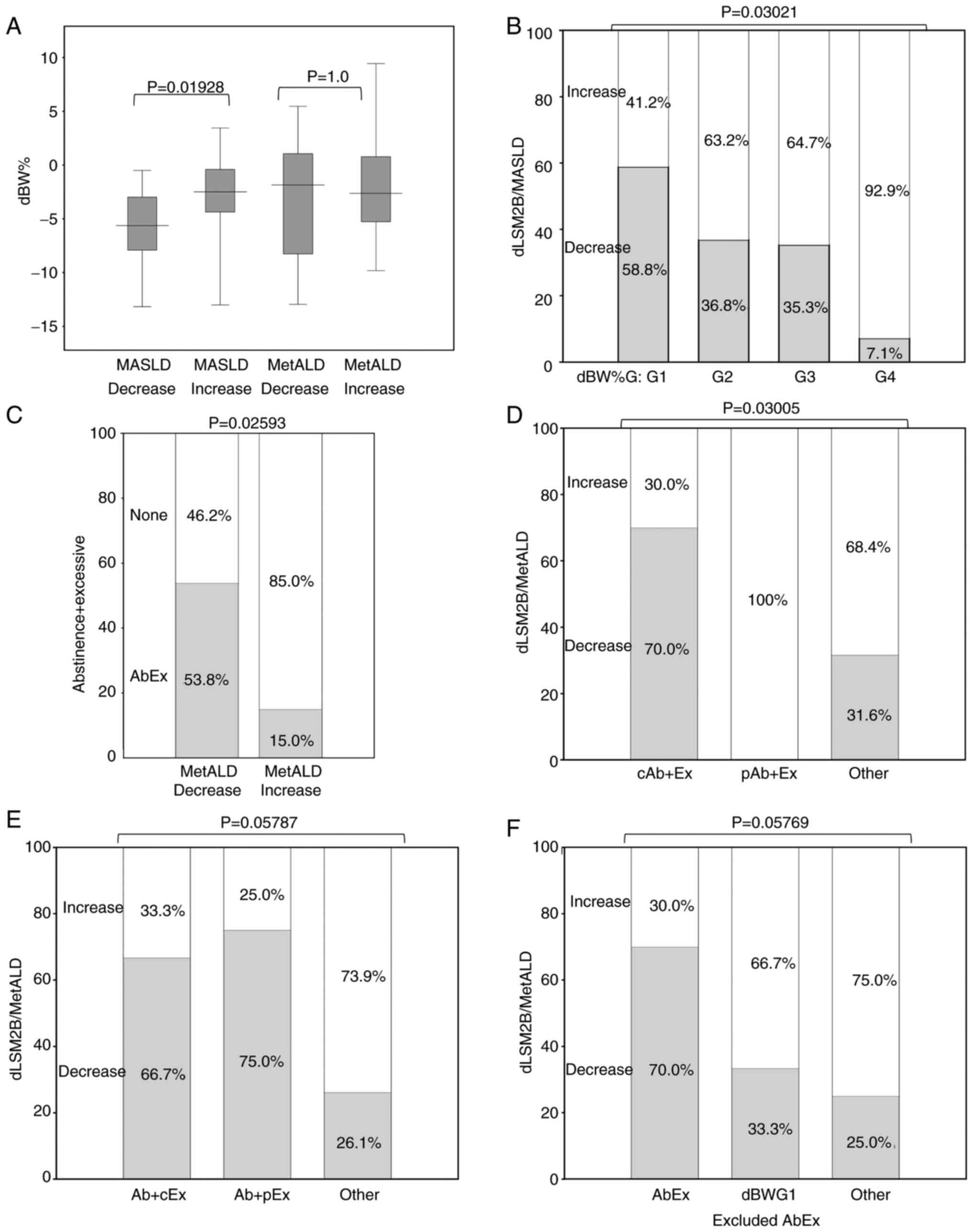

The correlation between dM2BPGi and dLS was R=0.5896

(P<0.00001) in all cases (N=87). When only one of LS and M2BPGi

was measured, fibrosis reduction was defined as a decrease in the

measured item. The rates of decrease in dLSM2B levels were 35.8 and

39.4% in MASLD and MetALD (no significance difference (Fig. S1B). Among patients with MASLD, a

decrease in the dLSM2B group was associated with weight loss

(Table II). Patients with MASLD

had greater dBW% in the decreased dLSM2B group; however, patients

with MetALD showed no significant differences (Fig. 1A). The distribution of the weight

loss rate was associated with a decrease in dLSM2B in patients with

MASLD, but not in those with MetALD (Figs. 1B and S1C).

| Figure 1Relationship between with dLSM2B

decrease and change of lifestyle. The dLSM2B decreased group is the

group with no increase in LS (dLS) and no increase in M2BPI (dM2B),

and the dLSM2B increased group is the group other than the

decreased group. Change of LS and M2B were difference form entry to

0.5 year after. Exercise (Ex) was defined as 100% of 30 min of

walking; if less, self-reported walking time was divided by 30 min

and expressed as a percentage. The Ex+ group is the

group that was able to add any degree of exercise, and the None

group is the group that did not add any exercise at all. The

abstinence group was the group that completely stopped drinking

alcohol by self-report. The AbEx group is an Ex+ and

abstinence group. Decreased body weight (dBW%) is calculated as

follows: (BW at entry-BW at 0.5 year after)/BW at entry. BW

decrease rate groups (dBWG) were divided by quartiles of dBW% as

follows: G1: -6.1%>; G2, -6.1 to -3.1; G3, -3.1 to -0.77; G4,

-0.77<. (A) Differences in the relationship between weight loss

and liver fibrosis improvement in MASLD and MetALD. dBW% was

compered between dLSM2B decrease and increase groups in MASLD and

MetALD. Y axis is dBW%. (B) Association between weight loss and

liver fibrosis improvement in MASLD. In MASLD, dBWG and dLSM2B

decrease group. G1, 17 patients; G2, 19 patients; G3, 17 patients;

G4, 14 patients. Y axis is dLSM2B decrease group percentile. (C)

Association between abstinence + exercise and improvement of liver

fibrosis in MetALD. Rate of AbEx in groups related to dLSM2B

decrease group. Y axis is AbEx percentile. (D) Relationship between

complete abstinence and liver fibrosis improvement in MetALD. In

MetALD, the relation between degree of abstinence and dLSM2B

decrease group. cAb is complete abstinence and pAb is partial

abstinence included decrease drink. Ex is the group that was able

to add any degree of exercise. cAb + Ex group, 10 patients; pAb +

Ex group, 4 patients; other group, 19 patients. Y axis is dLSM2B

decrease group percentile. (E) Relationship between achievement of

exercise goal and improvement of liver fibrosis in MetALD. In

MetALD, the relation between degree of exercise and dLSM2B decrease

group. cEx is 30 min of more of walking and pEx is less than 30 min

of walking. Ab is stop of drinking. Ab + cEx group, 6 patients; Ab

+ pEx, 4 patients; other, 23 patients. (F) Comparison of liver

fibrosis improvement between alcohol abstinence exercise group and

weight loss group in MetALD. In MetALD, the relation between degree

of BW and dLSM2B decrease group. AbEx is an Ex+ group

and an abstinence group. dBWG1 excluded AbEx group is dBWG1 and

non-AbEx group. AbEx group, 10 patients; dBWG1 excluded AbEx, 3

patients; other, 20 patients. MASLD, metabolic

dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; MetALD, metabolic

dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and

alcoholic-related liver disease. |

| Table IIThe relation with dLSM2B and clinical

factors. |

Table II

The relation with dLSM2B and clinical

factors.

| | MASLD | MetALD |

|---|

| | Decrease | Increase | P-value | Decrease | Increase | P-value |

|---|

| dLSM2B | | | | | | |

| dBW% | | | | | | |

|

n | 24 | 43 | 0.00152 | 13 | 20 | 0.58050 |

|

Me

(Q1~Q3) | -5.63

(-7.92~-2.98) | -2.50

(-4.37~-0.40) | | -1.84

(-8.28~1.04) | -2.63

(-5.28~0.77) | |

| dBW%G1 | | | | | | |

|

G1 | 10 (41.7) | 7 (16.3) | 0.02204 | 5 (38.5) | 3 (15.0) | 0.21338 |

|

G2-4 | 14 (58.3) | 36 (83.7) | | 8 (61.5) | 17 (85.0) | |

| Ex | | | | | | |

|

n | 24 | 43 | 0.94625 | 13 | 20 | 0.31540 |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | 0.5 (0.0, 0.9) | 0.5 (0.0, 1.0) | | 0.8 (0.2, 1.0) | 0.3 (0.0, 1.0) | |

| Ex G | | | | | | |

|

Ex+ | 17 (70.8) | 30 (69.8) | 0.92716 | 10 (76.9) | 13 (65.0) | 0.70059 |

|

None | 7 (29.2) | 13 (30.2) | | 3 (23.1) | 7 (35.0) | |

| Nutritional

guidance | | | | | | |

|

Done | 16 (66.7) | 22 (51.2) | 0.21942 | 5 (38.5) | 5 (25.0) | 0.46107 |

|

None | 8 (33.3) | 21 (48.8) | | 8 (61.5) | 15 (75.0) | |

| Abstinence | | | | | | |

|

abstinence | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 1.00000 | 7 (53.8) | 4 (20.0) | 0.06455 |

|

None | 24 (100.0) | 42 (97.7) | | 6 (46.2) | 16 (80.0) | |

| abEx | | | | | | |

|

none | 24 (100.0) | 43 (100.0) | Insufficient

number | 6 (46.2) | 17 (85.0) | 0.02593 |

|

abEx | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | | 7 (53.8) | 3 (15.0) | |

In patients with MetALD, complete

abstinence from alcohol and the addition of exercise were

associated with a decrease in liver fibrosis

In patients with MetALD, alcohol abstinence and

additional exercise, but not weight loss, were associated with a

decrease in dLSM2B (Table II and

Fig. 1C). Patients with MetALD were

more likely to show a decrease in the dLSM2B group for complete

abstinence from alcohol (with exercise) than for those with partial

abstinence (with exercise) or others (Fig. 1D). There was no significant

difference in the decrease in dLSM2B between achieving exercise

goals (with abstinence), partial exercise goals (with abstinence),

and other goals in patients with MetALD (Fig. 1E). The percentage of patients with

MetALD with reduced dLSM2B levels was 23% in the abstinence alone

or exercise alone group, 30% in other (the non-abstinence and

non-exercise) groups, and 70% in the AbEx group, with no

significant difference between the three groups; however, a trend

toward a difference was observed (Fig.

S1D). Patients with MetALD treated with AbEx did not differ

from non-AbEx patients with dBW%G1 or others in terms of the rate

of dLSM2B reduction (Fig. 1F).

Although the difference was not significant, the rate of reduction

in dLSM2B was 80% with AbEx and G1 weight loss, 60% with AbEx and

no G1 weight loss, and 33% with G1 weight loss alone (Fig. S1E). In MetALD cases, there was no

significant difference in dLSM2B between the three groups of

complete Ab, partial Ab, and no Ab (Fig. S1F), and similarly no significant

difference between the three groups of complete Ex, partial Ex, and

no Ex (Fig. S1G).

Decrease in dLSM2B by lifestyle

modification for patients with MASLD is predicted by a decrease in

FIB-4 and weight loss, but not for patients with MetALD

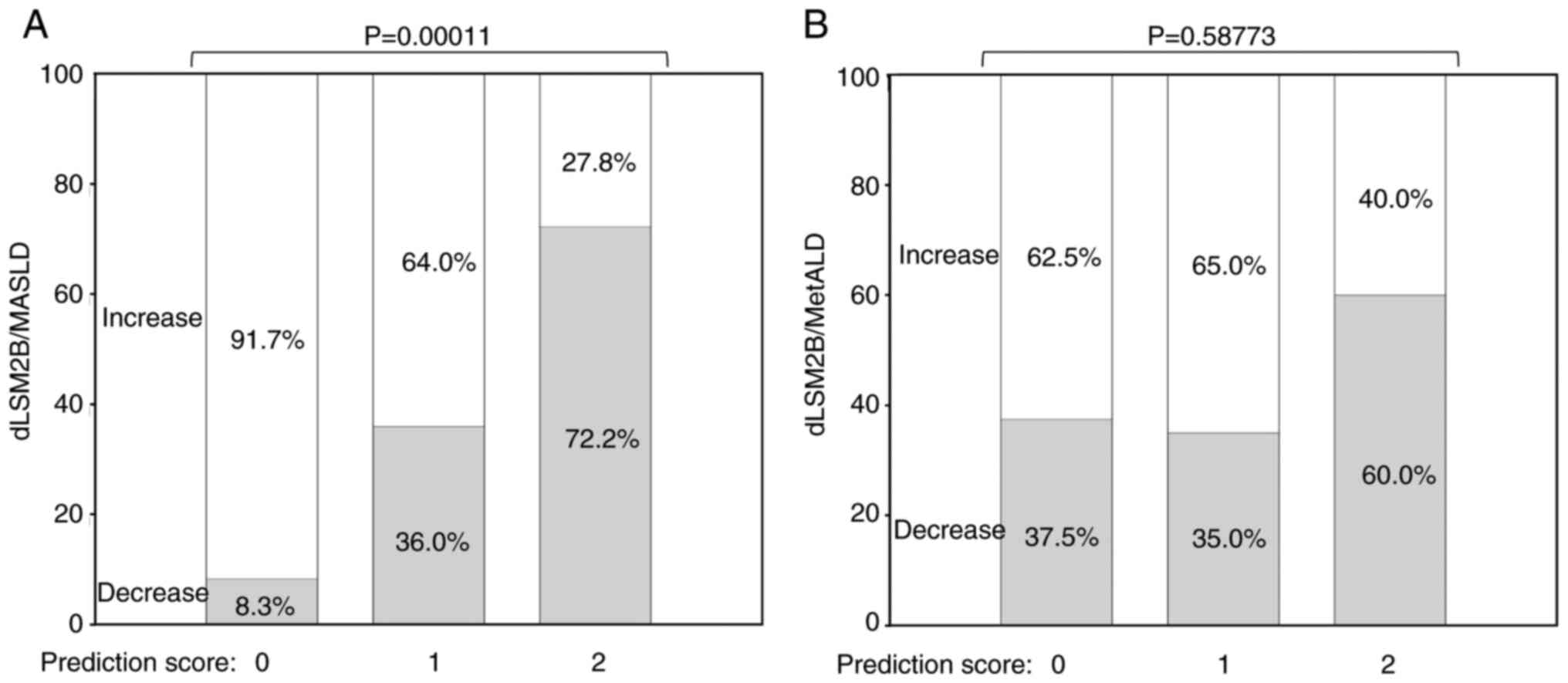

Predictive factors that could improve liver fibrosis

in patients with MASLD were searched. In patients with MASLD, no

baseline factors differed significantly between the decreased and

increased dLSM2B groups (Table

SI). However, among the factors that changed over the

observation period, there were significant differences in the AST,

ALT, CAP and FIB-4 levels between the two groups (Table SII). Using ROC analysis, the cutoff

values for the dLSM2B reduced group were calculated for five

factors (these four factors plus dBW%). No significant differences

were observed in the area under the curve (AUC) of the five factors

(Fig. S2A). Since AST and ALT were

included in FIB-4, and dBW and dCAP were significantly correlated

(Table SIII), dFIB-4 and dBW% were

selected as predictors. dBW% (-3.8% over) and dFIB-4 (-0.201 over)

were used as predictors of a decrease in the dLSM2B group. The odds

ratios (ORs) of the dBW% (-3.8% or more) and dFIB-4 (-0.201 or

more) groups contributing to a decrease in dLSM2B were assessed

using logistic analysis. The results indicated that these two

predictors contributed independently (Fig. S2B). A prediction score of 0, 1 or 2

points was developed to predict the decrease in dLSM2B, with 1

point awarded for a dBW% reduction of ≥3.8 and 1 point for a FIB-4

reduction of ≥0.201. In patients with MASLD, there was a

significant difference in the decrease in dLSM2B by 8.3% for a

prediction score of 0, 36% for 1, and 72.2% for 2 (Fig. 2A), whereas there was no significant

difference in the improvement rate for 0-2 points (Fig. 2B). In patients with MASLD, a

prediction score contributed to a decrease in dLSM2B in univariate

logistic analysis (OR, 5.224; 95% CI lower-upper: 2.231-12.232;

P=0.00014), but not in the MetALD group (OR, 1.482; 95% CI

lower-upper: 0.472-4.650; P=0.50048). In patients with MASLD,

multiple logistic analysis of the effects of a prediction score and

dBW% (-3.8% or more) on dLSM2B decrease showed that only a

prediction score was significant [Fig.

S2C; variance inflation factors (VIF); 2.667], as was the

comparison of a prediction score and dFIB-4 (-0.201 or more)

(Fig. S2D; VIF; 2.652).

Influence of alcohol consumption on

lifestyle modification in MetALD patients

The effects of alcohol consumption in patients with

MetALD were examined. The amount of alcohol consumed (ALD score)

was defined as grade 1 for 30-45 g of alcohol for men and 20-35 g

for women, and grade 2 for 45-60 g for men and 35-50 g for women.

Differences in sex and LS were observed for MetALD grade 1

(MetALD1) and MetALD2, but not significant for other pretreatment

factors (Table SIV). Particular

sex differences were observed in MASLD, MetALD1 and MetALD2

(Fig. S3A). In a comparison among

the three groups (MASLD, MetALD1, and MetALD2), differences in LS

were found between MASLD and MetALD2, whereas MASLD and MetALD1

were similar (Fig. S3B).

Considering lifestyle modification, weight loss was less frequent

in the MetALD2 group, and there were no significant differences in

abstinence from alcohol, physical activity, or frequency of

nutritional guidance (Table III).

The distribution of dBW% (dBW% G1-4) showed differences among

MASLD, MetALD1 and MetALD2, which were characterized by more G1 in

MetALD1 and G4 in MetALD2 (Fig.

S3C). The dBW% was also not significantly different between the

MASLD and MetALD1 groups; only the MetALD2 group showed a lower

rate than the MASLD and MetALD1 groups (Fig. S3D). There were no significant

differences in AST, ALT, PLT, LS, CAP, M2BPGi and FIB-4 levels

between the two groups over the treatment period (Table SV).

| Table IIILifestyle change in MetALDG1/2. |

Table III

Lifestyle change in MetALDG1/2.

| MetALD Grade

1/2 | Grade1 | 2 | P-value |

|---|

| dBW% | | | |

|

Me (Q1,

Q3) | -4.086 (-6.98,

-1.596) | 1.423 (-1.331,

3.910) | 0.00243 |

| dBW%G | | | |

|

1 | 7 (33.3) | 1 (8.3) | 0.02123 |

|

2 | 5 (23.8) | 1 (8.3) | |

|

3 | 6 (28.6) | 2 (16.7) | |

|

4 | 3 (14.3) | 8 (66.7) | |

| dBW%G4 | | | |

|

4 | 3 (14.3) | 7 (58.3) | 0.01636 |

|

1-3 | 18 (85.7) | 5 (41.7) | |

| Abstinence/no | | | |

|

Abstinence | 7 (33.3) | 4 (33.3) | 1.00000 |

|

None | 14 (66.7) | 8 (66.7) | |

| abEx | | | |

|

None | 14 (66.7) | 9 (75.0) | 0.70981 |

|

abEx | 7 (33.3) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Ex G | | | |

|

Ex | 17 (81.0) | 6 (50.0) | 0.11422 |

|

None | 4 (19.0) | 6 (50.0) | |

| Nutritional

guidance | | | |

|

Done | 7 (33.3) | 3 (25.0) | 0.70981 |

|

None | 14 (66.7) | 9 (75.0) | |

Discussion

In the present study, 67 patients with MASLD and 33

patients with MetALD were instructed to improve their lifestyle,

and changes in liver fibrosis were assessed after six months. Prior

to lifestyle modifications, the evaluation revealed more men with

advanced liver fibrosis and MetALD. As a result of lifestyle

modifications, weight loss was associated with improved liver

fibrosis in patients with MASLD, but not in those with MetALD. By

contrast, complete abstinence from alcohol and exercise was

associated with improved liver fibrosis in patients with MetALD.

The predictive score, consisting of a decrease in FIB-4 index and

body weight, was associated with improved liver fibrosis in

patients with MASLD, but not in those with MetALD. Patients with

MetALD (MetALD1) who drank less alcohol had a similar degree of

weight loss to those with MASLD, and their liver fibrosis before

lifestyle modification was milder than that of patients (MetALD2)

patients who drank more. These results indicate a difference in the

effects of weight loss between MASLD and MetALD. Complete

abstinence from alcohol and exercise are considered effective in

improving the lifestyle of patients with MetALD. Thus, MetALD1 may

be similar to MASLD and MetALD2 in ALD.

In the present study, patients with MetALD had more

worsening liver fibrosis (FIB-4, M2BPGi and LS) and a male-dominant

sex difference than those with MALSD, but age and BMI did not

differ between the groups. Although one study did not find a sex

difference (9), most studies

indicate that MetALD is more common in males than in females as

compared with MASLD (10-12).

Even after adjusting for sex differences, MetALD has a worse

prognosis for liver and cardiovascular diseases than ALD (12-14).

The prevalence of MetALD in these studies ranged from 1.7-17.0% in

a resident-based cohort (3). When

the proportion of patients with MetALD was 1.7% in the overall

cohort, it was 2.5% in the SLD group, and when it was 17% in the

overall cohort, it was 24% in the SLD group (3). In the present study, 33 patients with

MetALD represented 33% of patients with SLD. When the target SLD is

narrowed down to cases with advanced fibrosis, MASLD and MetALD are

reported to represent 2.4 and 1.5% of all cases, respectively

(9), and it is estimated that the

number of MASLD and MetALD cases will converge as fibrosis worsens.

The large number of MetALD cases in the present study was

presumably because this was a hospital-based study with more cases

of advanced liver damage than studies in the general

population.

In the present study, differences were found between

the MASLD and MetALD groups in the relationship between weight loss

and decreased fibrosis. In MASLD, 7-10% weight loss is required to

improve MASH and liver fibrosis (5,15,16).

The FIB-4 is insufficient as a primary screening tool for liver

fibrosis in the general population (17). However, in MASLD, a decrease or

normalization of ALT levels is an indicator of improvement in the

MASH score, whereas changes in FIB-4 (14,15),

is an indicator of liver fibrosis (18). FIB-4 is a first-line test in MASLD

practice (5,15) and a cost-effective screening test

for high-risk MASLD (19).

Decreased FIB-4 and weight were independent ameliorating factors

for liver fibrosis in patients with MASLD (Fig. S2B). The combination of these two

parameters is a predictor of improvement of liver fibrosis is a new

finding. However, weight loss was not associated with improved

liver fibrosis in patients with MetALD, and the predictors created

by the MASLD results were not valid for MetALD. Because MetALD is a

condition that includes MASLD and ALD, MASLD and ALD should be

treated separately (2,3). However, because MetALD is a new

condition, no studies have examined the effect of weight loss;

therefore, it is necessary to develop a lifestyle intervention for

MetALD in the future.

Weight loss was not clearly associated with liver

fibrosis in MetALD, but complete abstinence from alcohol and the

addition of exercise were associated with liver fibrosis in MetALD.

Furthermore, complete abstinence from alcohol was more effective

than partial abstinence, and there was no difference in

effectiveness between performing daily exercise as directed and

performing it less than directed but as little as possible.

Education regarding lifestyle modifications for patients with ALD

is likely to be optimized by improving physical activity (20). Patients with alcohol use disorder

(AUD) who were able to add exercise were less associated with the

development of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) than those who did not

exercise (21). Patients with MASLD

and ALD understand the importance of exercise, but lack of

confidence in exercising and fear of falling are associated with

difficulties in exercising, which can be modified with education

and are goals of exercise acceptance (22). Based on these reports, exercise

education is very important for patients with MetALD, and if

exercise is enabled, improvement in liver fibrosis can be expected.

Complete abstinence from alcohol is recommended in cases of

cirrhosis, whereas alcohol reduction is recommended in SLD other

than advanced fibrosis (13),

although some studies have indicated that abstinence from alcohol

is also required for MetALD (2,15,23).

In the present study, complete alcohol abstinence was necessary to

improve liver fibrosis, and exercise may have been effective. Even

in patients with MASLD and low alcohol intake, there is a

relationship between alcohol consumption and risk of liver fibrosis

(24). Alcohol consumption and

mortality risk both increased, and the amount of alcohol consumed

that minimized health losses was zero (25). When metabolic dysfunction and

alcohol consumption coexist, pathogenic pathways leading to liver

injury are likely to be additive and synergistic (3,26).

These results indicate that patients with MetALD but without

cirrhosis should also be educated about complete abstinence from

alcohol. Alcohol consumption is the most important factor affecting

the severity of alcohol-related SLDs (MetALD + ALD) (27). Although the success rate of drinking

in patients with MetALD has not been reported, 21% of patients who

attended Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) with alcohol-related problems

successfully abstained from alcohol for one year if they wanted to

abstain, and 10% at one year if they did not want to (28). The effectiveness of AA meetings,

cognitive-behavioral therapy, and exercise in improving abstinence

rates is expected to be effective (29). All the patients in the present study

were referred by their general practitioners, and at the time of

their first visit to our department, they had already received an

explanation of the effectiveness and necessity of abstinence from

alcohol. Therefore, it is assumed that numerous came to our clinic

to abstain from alcohol. Additionally, the benefits of abstinence

from alcohol were explained to patients with MetALD, and have

sought their understanding before promoting physical exercise,

which it is considered that has led to the current abstinence rate

(33%) in our hospital. Therefore, alcohol abstinence may eliminate

aggravating factors and improve liver fibrosis in some patients,

independent of weight loss.

Our exercise instructions for patients with MASLD

and MetALD followed Western guidelines (4,14),

with instructions for 150 min of moderate exercise per week or 75

min of vigorous exercise per week. Specifically, they were

encouraged to exercise daily (30),

told them to work hard for an average of 30 min per day (31), and checked the amount of time they

could achieve. It has been reported that among people undergoing

health checkups, those aged 65 or older who have no exercise habits

are associated with liver fibrosis (32). Although the effect of exercise was

not related to changes in liver fibrosis in patients with MASLD,

the median value was 50%, and it is likely that the amount of

exercise was low. In the future, patients should be taught to

exercise at a minimal level (30 min of walking daily). Conversely,

excessive alcohol consumption is associated with increased dietary

intake and is related to obesity (33) and metabolic factor appearance

(27), and it is also known that

decreasing alcohol consumption results in improvement of obesity

(34). Weight loss had no clear

effect on liver fibrosis in patients with MetALD but should be

reexamined in more cases in the future. A comparison between

MetALD1 and MetALD2 showed that MetALD1 was closer to the MASLD (LS

and dBW%). In the future, classification of patients with MetALD in

terms of alcohol consumption may be necessary to predict the effect

of lifestyle modifications on liver fibrosis.

The limitation of the present study is that it was a

small, single-hospital, and retrospective study. In addition,

alcohol consumption and physical activity were patient-reported and

not quantifiable. Given the limited observation period of six

months in MetALD, it is possible that other factors may contribute

to long-term outcomes. Further follow-up and ongoing research are

therefore needed. However, the present study found that weight loss

in MASLD, alcohol abstinence, and additional exercise in MetALD

were associated with an improvement in liver fibrosis. When

teaching lifestyle modifications in SLD, it is important to first

teach weight loss for MASLD and complete abstinence and additional

exercises for MetALD. A combination of FIB-4 index reduction and

weight loss may be effective in predicting decreased liver fibrosis

in patients with MASLD. The effectiveness of weight loss in MetALD

needs to be further investigated in more cases, and the content of

exercise instruction also needs to be examined in the MASLD.

Screening for liver disease has been reported to increase

abstinence rates (35), and the

active involvement of hepatologists in MetALD (probably all

alcohol-related SLD) may increase abstinence rates. While a

multidisciplinary approach is necessary for patients with SLD

(5,15), education by hepatologists regarding

abstinence, weight loss, and exercise is also considered

necessary.

Supplementary Material

Distribution of decreased body

weights. Decreased body weight (dBW%) is calculated as follows: (BW

at entry-BW at 0.5 year after)/BW at entry. N is number. The y-axis

represents the number and the x-axis represents dBW%. Q1 and Q3

represent the first and third quartiles, respectively. (B) dLSM2B

ration in MASLD and MetALD. The dLSM2B decreased group had no

increase in LS or M2BPI, while the dLSM2B increased group was the

group other than the decreased group. The y-axis represents the

percentiles of the dLMM2B group in MASLD and MetALD. (C)

Distribution of the dBWG. Groups were divided by quartiles of dBW%

as follows: G1, -6.1%>; G2, -6.1 to -3.1; G3, -3.1 to -0.77; G4,

-0.77<. The y-axis represents the percentile of the dBWG. (D)

Relationship between the dLSM2B score group and

abstinence/exercise. The AbEx group discontinued drinking and

exercising. The Ab and Ex groups stopped drinking or exercising to

some degree. AbEx, 10 patients; Ab or Ex: 13 patients; other, 10

patients. The axis represents dLSM2B decrease percentile. (E)

Relationship between the dLSM2B decree group and the AbEx/dBWG1.

AbEx + dBWG1, 5 patients; AbEx-dBWG1, 5 patients; dBWG1-AbEx, 3

patients; other, 20 patients. (F) Relationship between the dLSM2B

decrease group and the Ab group. Complete Ab (cAb): 11 patients;

partial Ab (pAb): 10 patients; no Ab, 12 patients. (G) Relationship

between the dLSM2B decrease group and the Ex group. Complete Ex

(cEx): 13 patients; partial Ex (pEx): 10 patients; no Ex: 10

patients. MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver

disease; MetALD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver

disease and alcoholic-related liver disease.

(A) Receiver Operating characteristic

curve for the dLSM2B decrease group. The cut-off value was set to

be equal to the sensitivity and 1-specificity. P-values are for the

comparison area under the curve of factors 1 and 2. (B) Logistic

multi-factor analysis of the dLSM2B decrease group in the MASLD.

The dBW%-3.8 and dFIB-4-0.201 groups were selected based on the

results shown in Fig. S2A and

Table SIV. (C) Logistic

multi-factors analysis of the effect of a prediction score and dBW%

(-3.8% or more) on dLSM2B decrease. One point was given for a

decrease of 0.201 or more in FIB-4 and one point for a decrease of

3.8% or more in BW, and the total score was used as the predictor.

(D) Logistic multi-factors analysis of the effect of a prediction

score and dFIB-4 (-0.201 or more). AUC, area under the curve;

MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease;

CI, confidence interval; BW, body weight; Fib-4, Fibrosis-4; AST,

aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CAP,

CAP, controlled attenuation parameter.

(A) Amount of alcohol consumed (ALD

score) was defined as grade 1 for 30-45 g of alcohol for men and

20-35 g for women, and grade 2 for 45-60 g for men and 35-50 g for

women. Percentage of sex in MASLD, MetALD grade1 (MetALD1) and

MetALD grade 2 (MetALD2). Y axis is percentage. (B) Liver stiffness

at the first visit was compared with MASLD, MetALD1 and MetALD2.

The y-axis represents the LS (kPa). (C) Distribution of dBW%G

compared with that of MASLD, MetALD1 and MetALD2. The y-axis

represents the percentage of grade 1-4. (D) dBW% compared with

MASLD, MetALD1, and MetALD2. Y axis is dBW%. MASLD, metabolic

dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; MetALD, metabolic

dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and

alcoholic-related liver disease.

In the MASLD, the relationship between

the factors at entry and the dLSM2B group.

In MASLD, the relationship between

changes in clinical factors and the dLSM2B group.

In MASLD, the relation among

difference of clinical factors.

In MetALD, the relationship between

the factors at entry and alcohol grade.

Relationship between changes in

clinical factors and alcohol grade in patients with MetALD.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are not

publicly available due to containing information that could

compromise the privacy of research participants, but may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

TIc wrote the manuscript, analyzed the data and

designed the study. TIc, SM, MYa, SY, MK, YN, HY, OM, TIk, TO, NK,

MYo and HM collected the data. TIc and SM confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The protocol for this research project was approved

(approval no. H30-031) by the Ethics Committee of of Nagasaki

Harbor Medical Center (Nagasaki, Japan). Informed consent was

obtained from each patient included in the study and they were

guaranteed the right to leave the study if desired.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque

SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, Romero D, Abdelmalek MF, Anstee QM, Arab

JP, et al: A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty

liver disease nomenclature. J Hepatol. 79:1542–1556.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Marek GW and Malhi H: MetALD: Does it

require a different therapeutic option? Hepatology. 80:1424–1440.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Gratacós-Ginès J, Ariño S, Sancho-Bru P,

Bataller R and Pose E: MetALD: Clinical aspects, pathophysiology

and treatment. JHEP Rep. 7(101250)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Fukunaga S, Mukasa M, Nakane T, Nakano D,

Tsutsumi T, Chou T, Tanaka H, Hayashi D, Minami S, Ohuchi A, et al:

Impact of non-obese metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver

disease on risk factors for the recurrence of esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection: A

multicenter study. Hepatol Res. 54:201–212. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

European Association for the Study of the

Liver (EASL). Tacke F, Horn P, Wai-Sun Wong V, Ratziu V, Bugianesi

E, Francque S, Zelber-Sagi S, Valenti L, Roden M, et al:

EASL-EASD-EASO clinical practice guidelines on the management of

metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J

Hepatol. 81:492–542. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Liu X, Zhang W, Ma B, Lv C, Sun M and

Shang Q: The value of serum Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation

isomer in the diagnosis of liver fibrosis: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 15(1382293)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Shephard DA: The 1975 declaration of

Helsinki and consent. Can Med Assoc J. 115:1191–1192.

1976.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B,

Verkarre V, Nalpas A, Dhalluin-Venier V, Fontaine H and Pol S:

FIB-4: An inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV

infection. comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest. Hepatology.

46:32–36. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Oh JH, Ahn SB, Cho S, Nah EH, Yoon EL and

Jun DW: Diagnostic performance of non-invasive tests in patients

with MetALD in a health check-up cohort. J Hepatol. 81:772–780.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Männistö V, Salomaa V, Jula A, Lundqvist

A, Männistö S, Perola M and Åberg F: ALT levels, alcohol use, and

metabolic risk factors have prognostic relevance for liver-related

outcomes in the general population. JHEP Rep.

6(101172)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Díaz LA, Lazarus JV, Fuentes-López E,

Idalsoaga F, Ayares G, Desaleng H, Danpanichkul P, Cotter TG, Dunn

W, Barrera F, et al: Disparities in steatosis prevalence in the

United States by Race or Ethnicity according to the 2023 criteria.

Commun Med (Lond). 4(219)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Choe HJ, Moon JH, Kim W, Koo BK and Cho

NH: Steatotic liver disease predicts cardiovascular disease and

advanced liver fibrosis: A community-dwelling cohort study with

20-year follow-up. Metabolism. 153(155800)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Israelsen M, Francque S, Tsochatzis EA and

Krag A: Steatotic liver disease. Lancet. 404:1761–1778.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Moon JH, Jeong S, Jang H, Koo BK and Kim

W: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

increases the risk of incident cardiovascular disease: A nationwide

cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 65(102292)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA,

Siddiqui MS, Abdelmalek MF, Caldwell S, Barb D, Kleiner DE and

Loomba R: AASLD practice guidance on the clinical assessment and

management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology.

77:1797–1835. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Huttasch M, Roden M and Kahl S: Obesity

and MASLD: Is weight loss the (only) key to treat metabolic liver

disease? Metabolism 157:. 155937(155937)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ogawa Y, Tomeno W, Imamura Y, Baba M, Ueno

T, Kobayashi T, Iwaki M, Nogami A, Kessoku T, Honda Y, et al:

Distribution of Fibrosis-4 index and vibration-controlled transient

elastography-derived liver stiffness measurement for patients with

metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in health

check-up. Hepatol Res: Oct 4, 2024 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

18

|

Kaplan DE, Teerlink CC, Schwantes-An TH,

Norden-Krichmar TM, DuVall SL, Morgan TR, Tsao PS, Voight BF, Lynch

JA, Vujković M and Chang KM: Clinical and genetic risk factors for

progressive fibrosis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic

liver disease. Hepatol Commun. 8(e0487)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Younossi ZM, Paik JM, Henry L, Stepanova M

and Nader F: Pharmaco-economic assessment of screening strategies

for high-risk MASLD in primary care. Liver Int.

45(e16119)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Patel S, Kim RG, Shui AM, Magee C, Lu M,

Chen J, Tana M, Huang CY and Khalili M: Fatty liver education

promotes physical activity in vulnerable groups, including those

with unhealthy alcohol use. Gastro Hep Adv. 3:84–94.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Shay JES, Vannier A, Tsai S, Mahle R, Diaz

PML, Przybyszewski E, Challa PK, Patel SJ, Suzuki J, Schaefer E, et

al: Moderate-high intensity exercise associates with reduced

incident alcohol-associated liver disease in high-risk patients.

Alcohol Alcohol. 58:472–477. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Frith J, Day CP, Robinson L, Elliott C,

Jones DEJ and Newton JL: Potential strategies to improve uptake of

exercise interventions in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J

Hepatol. 52:112–116. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Beygi M, Ahi S, Zolghadri S and Stanek A:

Management of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease/metabolic

dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: From medication

therapy to nutritional interventions. Nutrients.

16(2220)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Marti-Aguado D, Calleja JL, Vilar-Gomez E,

Iruzubieta P, Rodríguez-Duque JC, Del Barrio M, Puchades L,

Rivera-Esteban J, Perelló C, Puente A, et al: Low-to-moderate

alcohol consumption is associated with increased fibrosis in

individuals with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver

disease. J Hepatol. 81:930–940. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Griswold MG, Fullman N, Hawley C, Arian N,

Zimsen SRM, Tymeson HD, Venkateswaran V, Tapp AD, Forouzanfar MH,

Salama JS and Abate KH: Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries

and territories, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the global

burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 392:1015–1035.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Díaz LA, Arab JP, Louvet A, Bataller R and

Arrese M: The intersection between alcohol-related liver disease

and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 20:764–783. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Arab JP, Díaz LA, Rehm J, Im G, Arrese M,

Kamath PS, Lucey MR, Mellinger J, Thiele M, Thursz M, et al:

Metabolic dysfunction and alcohol-related liver disease (MetALD):

Position statement by an expert panel on alcohol-related liver

disease. J Hepatol. 82:744–756. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Adamson SJ, Heather N, Morton V and

Raistrick D: UKATT Research Team. Initial preference for drinking

goal in the treatment of Alcohol problems: II. Treatment outcomes.

Alcohol Alcohol. 45:136–142. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Haber PS: Identification and treatment of

alcohol use disorder. N Engl J Med. 392:258–266. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Liu M, Ye Z, Zhang Y, He P, Zhou C, Yang

S, Zhang Y, Gan X and Qin X: Accelerometer-derived

moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and incident nonalcoholic

fatty liver disease. BMC Med. 22(398)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Stine JG, Schreibman IR, Faust AJ, Dahmus

J, Stern B, Soriano C, Rivas G, Hummer B, Kimball SR, Geyer NR, et

al: NASHFit: A randomized controlled trial of an exercise training

program to reduce clotting risk in patients with NASH. Hepatology.

76:172–185. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Nakano M, Kawaguchi M, Kawaguchi T and

Yoshiji H: Profiles associated with significant hepatic fibrosis

consisting of alanine aminotransferase >30 U/l, exercise habits,

and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

Hepatol Res. 54:655–666. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Kim SY and Kim HJ: Obesity risk was

associated with alcohol intake and sleep duration among Korean men:

The 2016-2020 Korea national health and nutrition examination

survey. Nutrients. 16(3950)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Miller-Matero LR, Yeh HH, Ma L, Jones RA,

Nadolsky S, Medcalf A, Foster GD and Cardel MI: Alcohol use and

antiobesity medication treatment. JAMA Netw Open.

7(e2447644)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Avitabile E, Gratacós-Ginès J,

Pérez-Guasch M, Belén Rubio A, Herms Q, Cervera M, Nadal R, Carol

M, Fabrellas N, Bruguera P, et al: Liver fibrosis screening

increases alcohol abstinence. JHEP Rep. 6(101165)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|