Introduction

In China, congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most

prevalent type of birth defect, accounting for ~30% of all

congenital birth defects in 2023(1). It affects 17-32‰ perinatal births

(1). The incidence of prenatal CHD

is also increasing. CHD incidence in 2020 was 4.3 times that in

2010(1). CHD is divided into

non-syndromic and syndromic phenotypes. Approximately 1/3 cases

have definite genetic or chromosomal abnormalities, of which ~23%

of CHD cases have chromosomal aneuploidy or copy number variation,

and ~10% have new mutations or genetic mutations inherited from

their parents (2,3). The pathogenesis is unclear in most

cases, especially in non-syndromic phenotypes. It is well accepted

that CHD is attributed to the co-effects of genetics, epigenetics

and environment (2-5).

Nutritional imbalances, drinking, smoking, drugs, hypoxia and other

environmental factors can increase the incidence of CHD (4,5).

Prenatal diagnosis of CHD mainly relies on ultrasonography. Hence,

it cannot be discovered until the defect develops to a stage that

can be measured using ultrasound (6). Therefore, additional molecular markers

are required for early screening.

Metabolites are the end products of all processes

occurring in cells. Metabolomics provides methods for identifying

changes in metabolite profiles to support early biomarker

discovery, disease diagnosis and treatment. Metabolomics, which is

performed on a high-throughput platform, refers to the screening,

identification, quantification and characterization of biochemicals

that are <1,800 Da and are involved in various biological

pathways (7). Metabolomics

represents a bridge between the genome and phenotype and serves a

connecting role in the transmission of biological information. The

disease or physiological state can be better reflected in the

metabolomic profile than in the transcriptome or proteome profile

(8). Effective small changes in

gene and protein expression can be amplified by metabolites, making

detection easier. Metabolomics has a simple metabolite information

base, which is less complex than others (genomics, transcriptomics

and proteomics). Several metabolomics studies have focused on fetal

CHD, using maternal serum and urine and amniotic fluid samples

(7-9).

To the best of our knowledge, amniotic fluid cells have not been

used for metabonomic screening of CHD. The present study used

cultured amniotic fluid cells from patients carrying fetuses with

CHD for untargeted metabolomics screening to discover the potential

pathogenesis and screen new molecular markers.

Materials and methods

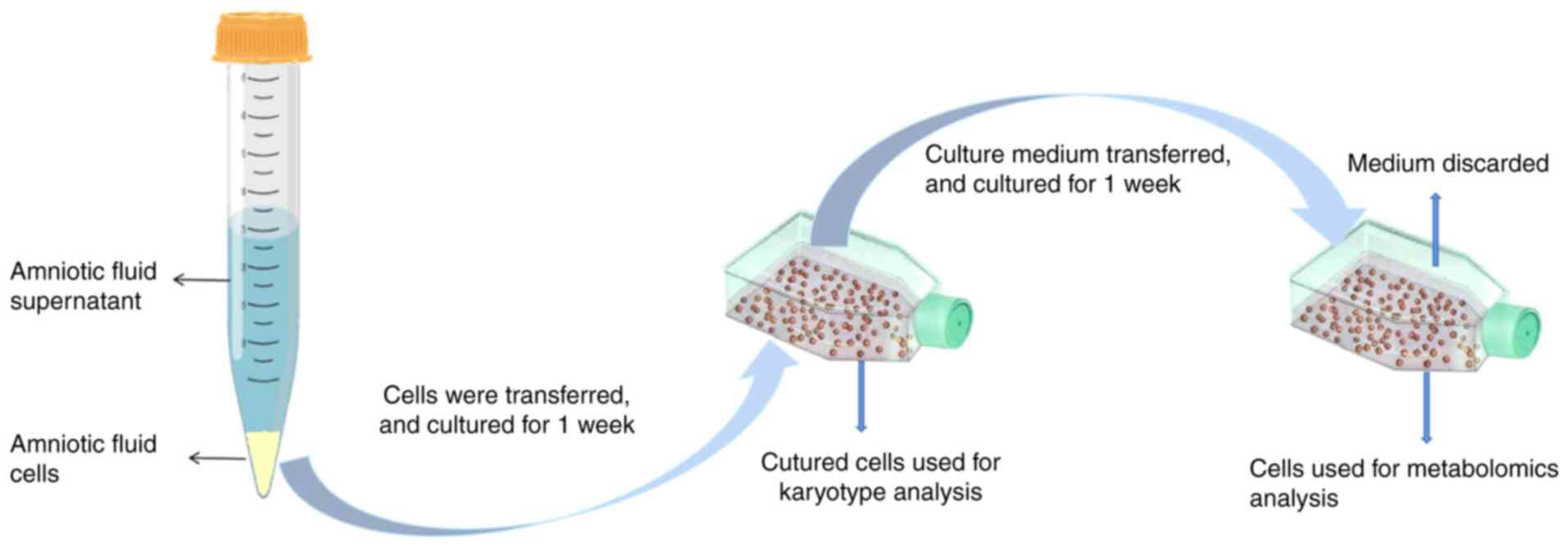

Sample collection and preparation

The cultured amniotic fluid cells [healthy controls

(no chromosomal or other disease), n=24; CHD cases (fetus with

ventricular septal defects), n=24] were obtained from singleton

pregnant patients who underwent amniocentesis during gestational

weeks 20.0-26.3. The patients were aged from 22 to 43 years old.

Inclusion criteria: Patients were willing to have amniocentesis. In

CHD group, the fetus was diagnosed as CHD by ultrasound. The

indication for amniocentesis in the control group was either older

than 35 years, a high risk in serum Down's screening or a high risk

of non-invasive prenatal screening. Exclusion criteria: The fetus

was affected with abnormalities chromosomes or abnormal copy number

variation. The samples were collected in Shengjing Hospital of

China Medical University (Shenyang, China) from April 2022 to

December 2022. All participants provided written informed consent,

and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shengjing

Hospital of China Medical University (approval no. 2022PS307K). The

sample collection and experimental procedures conformed to the

Declaration of Helsinki. All patients were non-smokers and

non-alcoholics. The samples were matched for maternal and

gestational age and sex of the fetus (Table I). The amniotic fluid cells were

cultured with amniotic fluid medium (FUJIFILM Biosciences; cat. no.

99473210805) for 2 weeks in 5% CO2 at 37˚C (Fig. 1).

| Table IClinical information for amniotic

fluid cells. |

Table I

Clinical information for amniotic

fluid cells.

| Group | n | Mean maternal age,

years | Mean gestational

age, weeks | Fetus sex

(male/female) |

|---|

| Control | 24 | 31.6±5.45 | 22.4±1.88 | 11/13 |

| CHD | 24 | 30.9±4.65 | 25.0±1.35 | 12/12 |

The metabolites were extracted from the cell residue

with 1 ml precooled methanol/acetonitrile/water (v/v, 2:2:1) under

sonication every 10 min for 1 h in ice baths. The mixture was

incubated at -20˚C for 1 h, followed by centrifugation at 14,000 x

g at 4˚C for 20 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a

sampling vial. To ensure data quality for metabolic profiling,

quality control (QC) samples were prepared by pooling aliquots

representative of all samples for data normalization. The

supernatant was evaporated using a high-speed vacuum-concentration

centrifuge, 14,000 x g and 4˚C about for 1 h. Dried extracts were

redissolved in 50% acetonitrile. Each sample was centrifuged at

14,000 x g and 4˚C for 20 min, and the supernatant was used for

analysis.

Ultra-high performance liquid

chromatography (UHPLC)-tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS)

analysis

Metabolomic profiling was performed on UPLC-MS/MS

system (1290 Infinity LC, Agilent Technologies, Inc.) and TripleTOF

5600 (SCIEX). Then, 5 µl Samples were separated with a 2.1x100.0 mm

ACQUIY UPLC BEH 1.7 µM column (Waters China Ltd.). The flow rate

was 0.5 ml/min and the mobile phase contained A (25 mM each

ammonium acetate and ammonium hydroxide in water) and B

(acetonitrile). The gradient was 95% B for 0.5 min and was linearly

reduced to 65% in 6.5 min, 40% in 2.0 min (maintained for 1.0 min)

and increased to 95% for 1.1 min, employing a 5-min

re-equilibration period. Both electrospray ionization (ESI)

positive and negative modes were applied for MS data acquisition.

The ESI source conditions were as follows: Ion source gas 1 and 2,

60; curtain gas, 30; source temperature, 600˚C; ion spray voltage

floating, ±5,500 V. In MS acquisition, the instrument was set to

acquire data over the m/z range of 60-1,200 Da, and the

accumulation time for MS scanning was 0.15 sec/spectra. In the auto

MS/MS acquisition, the instrument was set to acquire data over the

m/z range of 25-1,200 Da, and the accumulation time for the

production scan was 0.03 sec/spectra. Blank (50% acetonitrile in

water) and QC samples were injected every 12 samples during

acquisition. All the samples were run in one batch for the positive

and negative ion mode. Each sample was detected and analyzed using

UPLC-MS/MS, and two original files (positive and negative ion mode)

were obtained. MS total ion chromatogram (TIC) flow diagram was

generated.

Data preprocessing and filtering

Data processing and analysis were as previously

described with minor amendments (10). Raw MS data were converted to MzXML

files using ProteoWizard MS Convert and processed using XCMS for

feature detection, retention time correction and alignment. The

metabolites were identified by accurate MS (<25 ppm) and MS/MS

data, which were matched with a standard database (BaseDeepBP,

Shanghai Bioprofile Technology, Human Metabolome Database

(hmdb.ca/, MassBank, https://massbank.eu/MassBank/, MetaboBASE, http://metabase.com/, Global Natural Product Social

Molecular Networking, https://gnps.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/static/gnps-splash-old.jsp).

In the extracted-ion features, only the variables with >50% of

the non-zero measurement values in ≥1 group were retained.

Multivariate statistical analyses

All multivariate data analyses and modeling were

conducted using the SIMCAP software (Version 14.0, Umetrics;

Sartorius AG). After mean-centering the data using Pareto scaling,

models were developed using principal component analysis (PCA),

orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA)

and PLS-DA. All models were evaluated for overfitting using

permutation tests. Descriptive performance was assessed using

cumulative R2X [ideal model: R2X (cumulative)=1 and R2Y (ideal

model: R2Y (cumulative)=1] values, while prediction performance was

measured using cumulative Q2 [ideal model: Q2 (cumulative)=1)] and

a permutation test. In the permuted model, R2 and Q2 values at the

Y-axis intercept should be lower than those of the non-permuted

model. OPLS-DA was used to identify discriminating metabolites

using variable importance on projection (VIP) scores, which

indicate a variable contribution to class discrimination. VIP

scores were calculated as the weighted sum of squares of the PLS

weights, with values >1 considered statistically significant.

High VIP scores indicate strong discriminatory ability and help in

selecting biomarkers. Discriminating metabolites were obtained

using a statistically significant threshold of VIP values from the

OPLS-DA model and two-tailed Student's t-test (P-value) on

normalized raw data. Metabolites with VIP values >1 and

P<0.05 were considered statistically significant. The

fold-change was calculated as the ratio of the average mass area of

the CHD group to that of the control group. Identified differential

metabolites were used for cluster analyses using the R package (R

package version 1.0.12, CRAN.R-project.org/package=pheatmap). Hierarchical

clustering for each group was performed for heatmap.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis

To identify perturbed biological pathways,

differential metabolite data were subjected to KEGG pathway

analysis using the KEGG database (kegg.jp/). KEGG

enrichment analyses were performed using the Fisher's exact test

and false discovery rate correction for multiple testing was also

performed.

Animals and arginine/lysine

administration

A total of 18 Female C57BL/6J mice (age, 8-10 weeks,

Shenyang Lan Pudas technology co., ltd) were used (mean weight,

22.2±0.81 g; range, 20.8-23.6 g). The mice were kept in standard

cages under a 12/12-h light/dark cycle, ad libitum food and

water, temperature was 20-26˚C and humidity was 40-70%. To obtain

pregnant mice, female mice mated with male mice (n=6, 8-10 weeks

age, 23.2-25.6 g weight, Shenyang Lan Pudas Technology co., ltd)

and underwent testing every morning. Females with a vaginal plug

were immediately separated from the males and indicated as

embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). Pregnant mice were randomly assigned to

treatment (either arginine or lysine, Sigma) and control group

(both n=6). The treatment group received a single intraperitoneal

injection of 1.5 mg/g body weight/day arginine/lysine from E7.5 to

E14.5. The control group received an equivalent volume of saline.

Doses of arginine or lysine administration were determined as

previously described (11-13).

In addition to the routine feeding, mouse health and behavior were

checked every 12 h. The humane endpoints were cessation of eating

and movement and listlessness or lack of response when people

approached. No animals reached these endpoints. Pregnant mice at

E15.5 were anaesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane for 2-3 min. The

anesthetized mice had even heartbeat and breathing, relaxed muscles

and no limb activity or pedal reflex. A total of 100 µl peripheral

blood was collected from the inner canthus by capillary tube. Then,

mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. Death was confirmed

when heartbeat and respiration stopped and the pupils dilated for

>5 min. Maternal plasma arginine concentration was determined by

LC-MS/MS. All experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of

Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University (approval no.

2024PS202K).

Hematoxylin-eosin staining of

embryonic heart

The embryonic trunk was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde

solution at 4˚C for ≥48 h. The samples were dehydrated in 75, 85,

95 and 100% ethanol for 1 h. Following xylene treatment at room

temperature, 100% paraffin was used for tissue embedding. Then,

continuous slices of the embryonic heart (4 µm) were cut from the

top of the aortic arch to the apex of the heart and stained with

hematoxylin and eosin at room temperature for 1 min using automatic

stainer (Leica GmbH) and images were captured under a light

microscope.

Detection of amino acids in maternal

peripheral blood

Maternal peripheral blood (96 controls and 69 CHD

cases; gestational age, weeks 18.0-30.0, aged from 20 to 44 years

old, collected in Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University

from April 2022 to December 2022, the same Inclusion/exclusion

criteria as amniotic fluid cells collection) were collected to

detect the change of amino acids using a non-derivatized amino

acids detection kit (Neobase 2, Revvity, Inc.) on LC-MS/MS (QSight

210MD, PerkinElmer). The sample was detected with multiple reaction

monitoring mode scanning in positive ion mode. The ionization

conditions were as follows: Drying gas, 120 l/min; electrospray

voltage, 4,900 V; source temperature, 150˚C; nebulizer gas, 220

l/min; hot surface-induced desolvation temperature, 250˚C. The

injection volume was 10 µl. Chromatographic mobile phase A

(included in the detection kit) and the chromatographic gradient

elution procedure was as follows: 0.00-0.15 min, flow rate, 0.16

ml/min; 0.15-0.90 min, flow rate, 0.03 ml/min; 0.90-1.00 min, flow

rate, 0.7 ml/min and 1.0-1.15 min, flow rate, 0.16 ml/min. The

parameters of amino acid detection MS are listed in Table SI.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. At least three independent experimental repeats. The

analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS, Inc.).

Student's unpaired two-tailed t test, one-way ANOVA followed by

least significant difference post hoc test and χ2 test

were used for statistical analysis. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

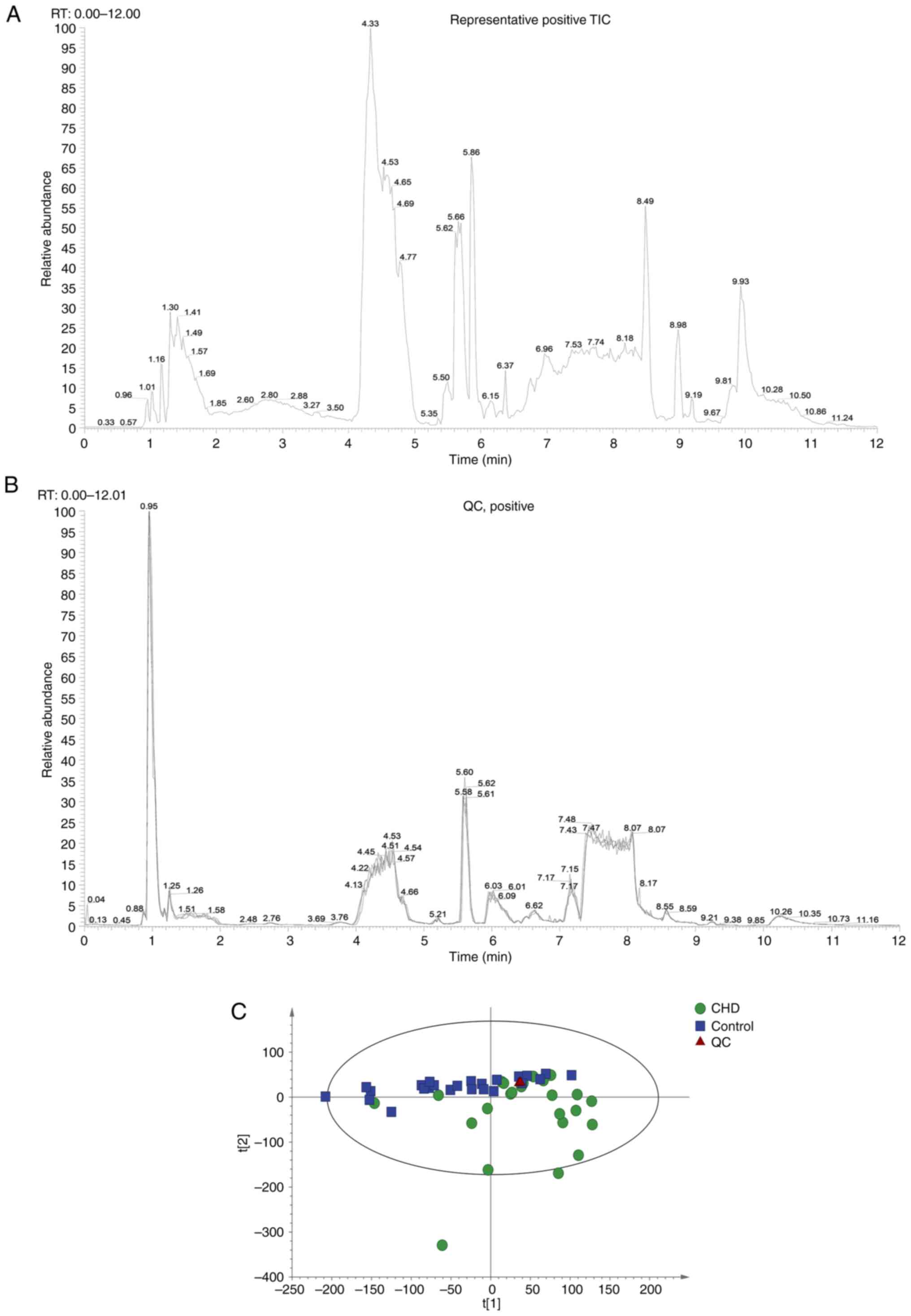

Experimental quality evaluation

Metabonomics analysis was performed on 48 samples

(24 controls and 24 CHD cases). Each sample was detected and

analyzed using UPLC-MS/MS, and two original files (positive and

negative ion mode) were obtained. Representative images are shown

in Fig. 2A. A total of 883

metabolites were identified (data not shown). The system stability

was evaluated using two strategies: MS total ion chromatogram (TIC)

flow diagram comparison of QC samples and PCA statistical analysis

of overall samples. A total of four QC TIC diagrams were overlaid

(Fig. 2B). The results suggested

that the response intensity and retention time of each color

spectrum peak overlapped, indicating that the variation caused by

instrument error was small and the data quality was reliable. The

ion peaks of metabolites extracted from all experimental and QC

samples were subjected to PCA. Samples were closely gathered

together, indicating that the experiment had good repeatability

(Fig. 2C). Thus, the instrument

analysis system had good stability, and the experimental data were

reliable. The metabolic spectrum difference reflected the

biological differences between the samples.

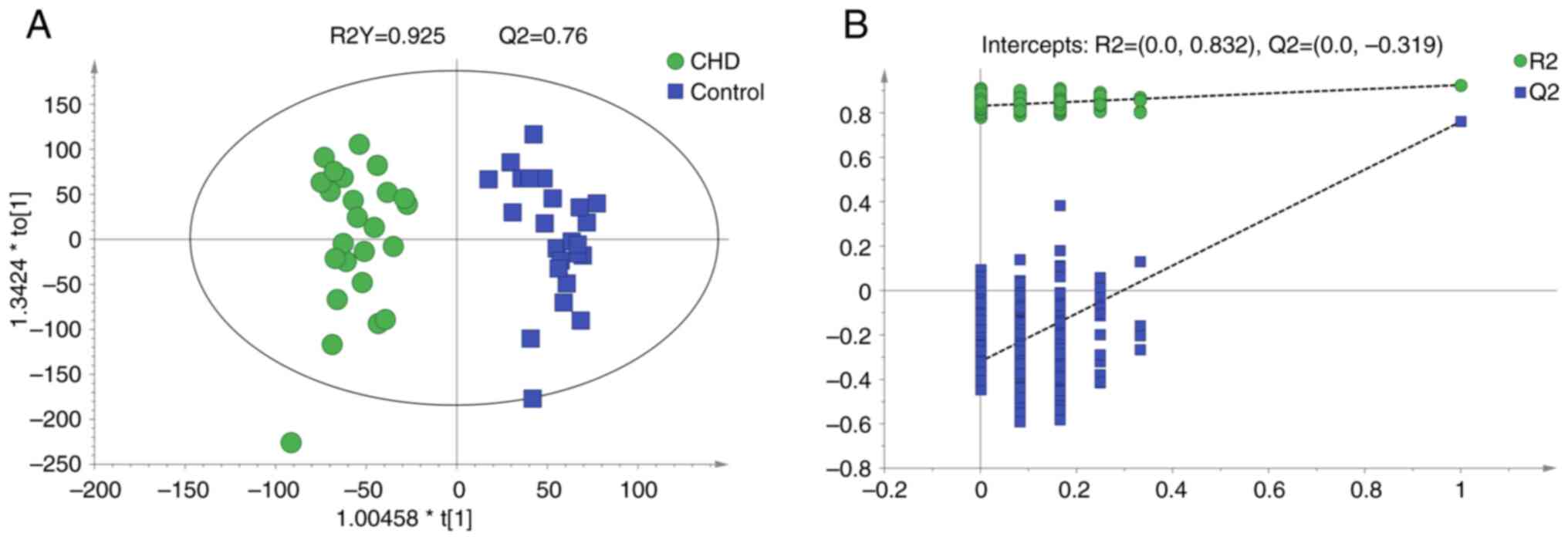

OPLS-DA

An OPLS-DA model was established to compare

metabolite profiles between the two groups. The model evaluation

parameters and score diagram are shown in Fig. 3. The OPLS-DA model distinguished the

two sample groups. The parameters (R2Y=0.925 and Q2=0.76) in the

OPLS-DA model suggested that the experimental data were stable and

reliable. The intercept of Q2 was -0.319, indicating there was no

overfitting in the OPLS-DA model established using the experimental

data. The OPLS-DA model showed separation in the metabolic profiles

between the CHD and control groups. A total of 292 different

metabolites (VIP>1 and P<0.05) were identified, of which 172

metabolites were up- and 120 metabolites were downregulated in the

CHD compared with the control group (supplementary data). The two

most changed metabolites were lysine

(L-lysine/lysine/N-methyllysine) and arginine

(homoarginine/L-arginine; Table

II).

| Table IIDifferential metabolites in

congenital heart disease compared with controls. |

Table II

Differential metabolites in

congenital heart disease compared with controls.

| Metabolite | ESI mode | RT, min | m/z | VIP | Fold-change | P-value |

|---|

| L-lysine | Negative | 9.954 | 145.097 | 1.67 | 1,848.38 | 0.0005 |

| Lysine | Positive | 10.013 | 147.112 | 1.41 | 629.88 | 0.0042 |

| N-methyllysine | Negative | 9.886 | 159.112 | 1.76 | 50.56 | 0.0002 |

| Homoarginine | Negative | 9.853 | 187.119 | 1.74 | 766.51 | 0.0003 |

| L-arginine | Positive | 10.086 | 175.119 | 1.58 | 38.19 | 0.0015 |

| D-aspartate | Negative | 8.672 | 132.029 | 1.27 | 25.97 | 0.0034 |

| L-asparagine | Negative | 8.445 | 131.045 | 1.24 | 7.26 | 0.0049 |

| Proline | Positive | 10.139 | 116.071 | 1.51 | 22.71 | 0.0023 |

| L-ornithine | Negative | 10.061 | 131.081 | 1.49 | 11.66 | 0.0016 |

| Glutamine | Negative | 8.200 | 145.061 | 1.33 | 11.28 | 0.0038 |

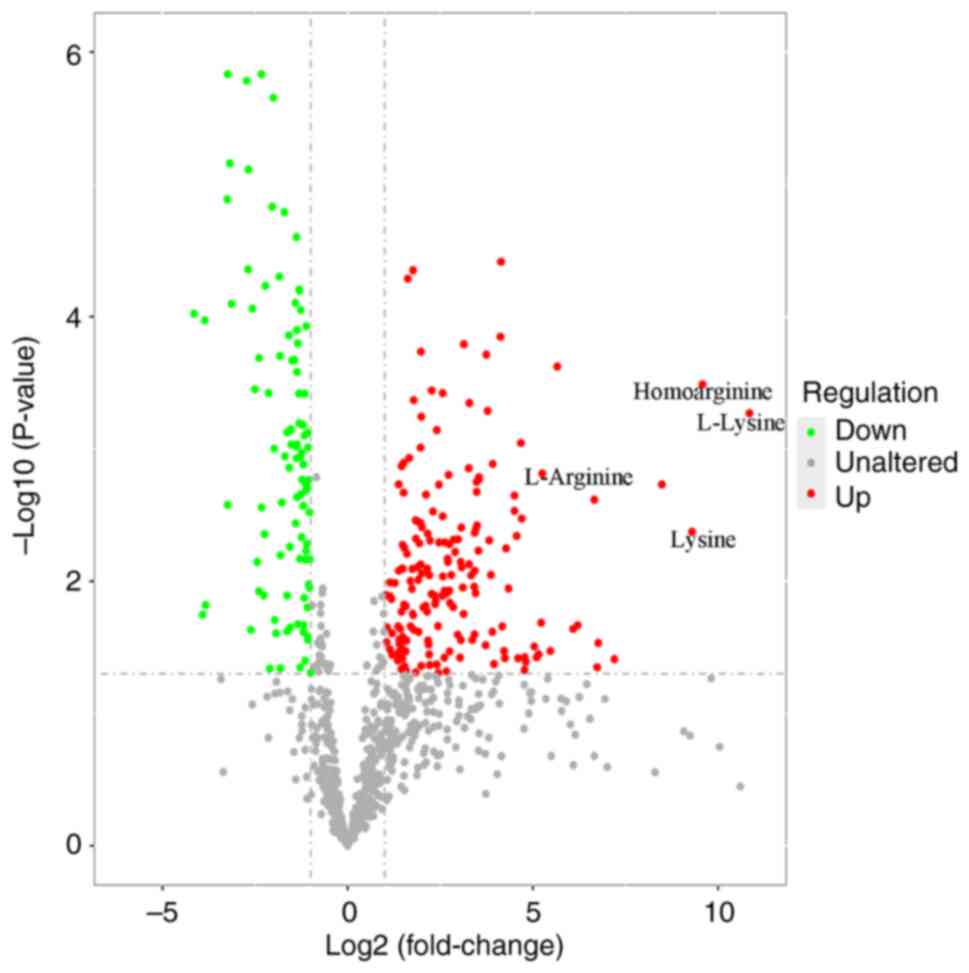

Univariate statistical analyses

To identify potential marker metabolites, univariate

analysis was performed (FC<0.5 or >2.0). Lysine and arginine

were the two most changed metabolites (Fig. 4). The fold-changes of L-lysine,

lysine, homoarginine and L-arginine were 1848.4, 629.9, 766.5 and

38.2, respectively.

Hierarchical cluster analysis

To evaluate the potential differential metabolites,

hierarchical clustering for each group was performed (Fig. S1). Generally, when the candidate

metabolites screened are reasonable and accurate, the same group of

samples appear in the same cluster. Metabolites in the same cluster

have similar expression patterns. Although some samples strayed

from their groups, most were concentrated in their respective

groups.

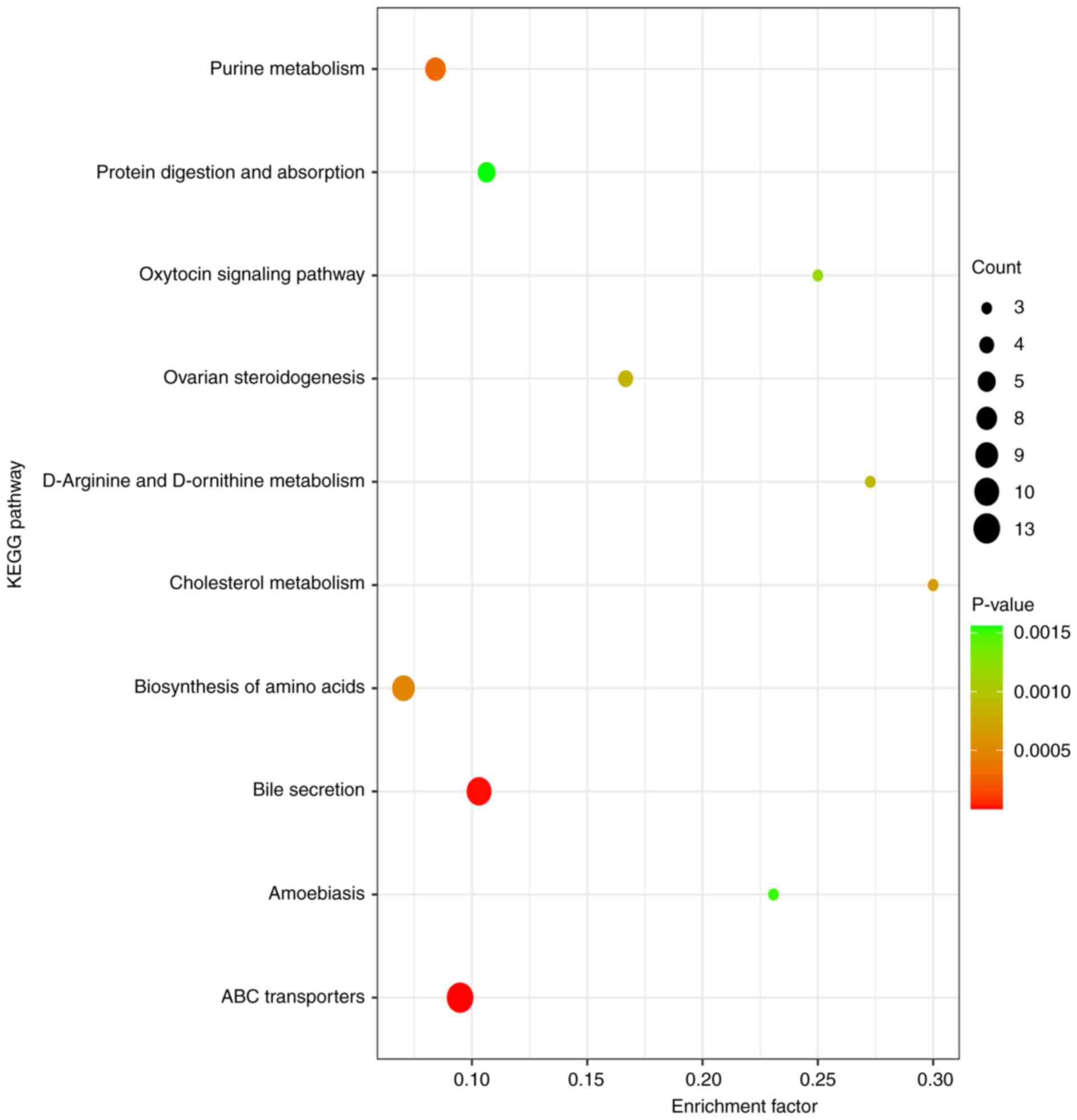

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

The differential metabolites were analyzed using

KEGG (Fig. 5; supplementary data).

The results demonstrated that amino acid metabolism (involved in

‘ABC transporters’, ‘biosynthesis of amino acids’ and ‘D-arginine

and D-ornithine metabolism’) may play an important role in CHD

development.

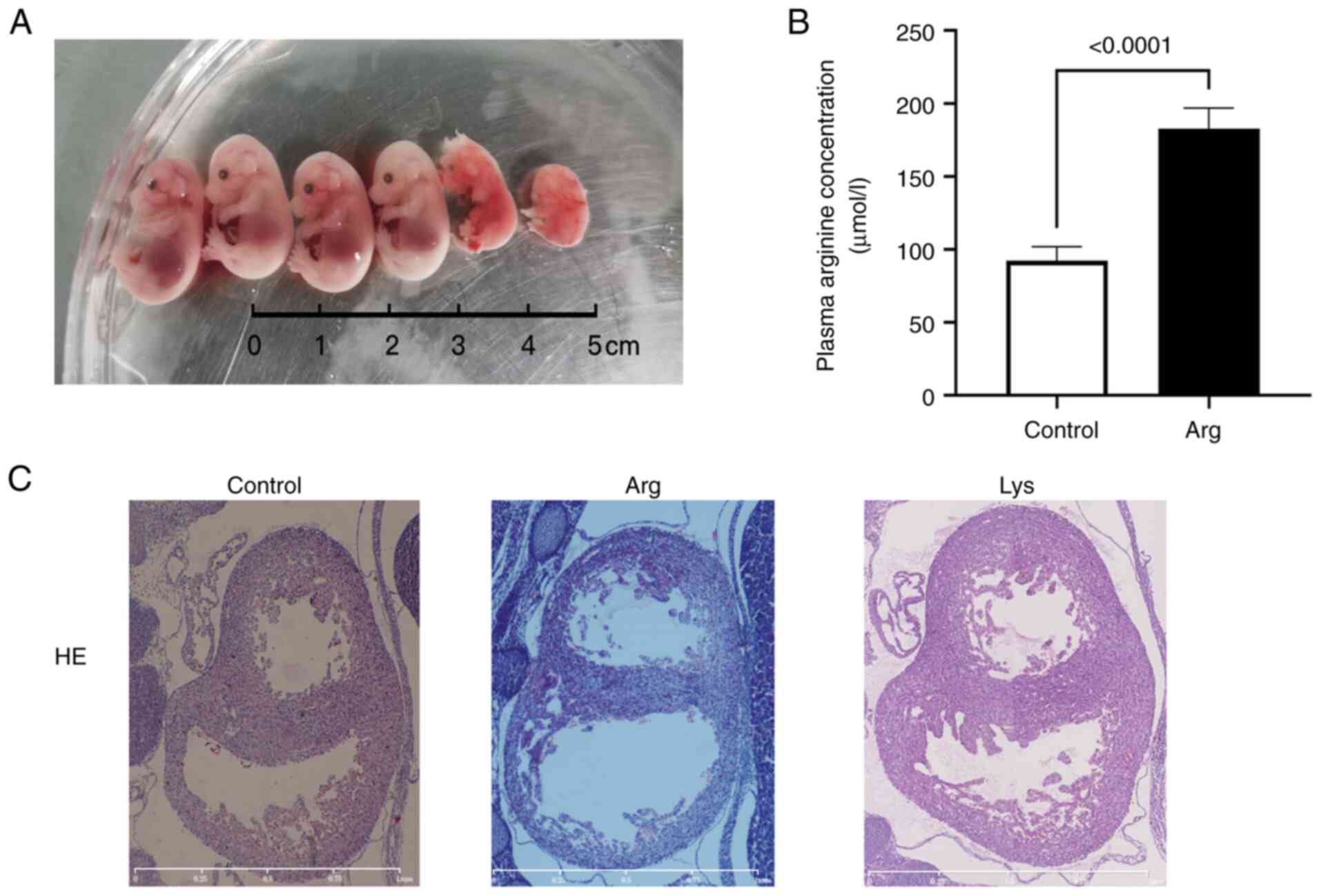

Arginine results in heart

malformation

To test whether arginine/lysine affect heart

development, arginine/lysine was intraperitoneal injected in

pregnant mice. Litter size decreased, and the naked deformity rate

increased after arginine treatment (Fig. 6A; Table III). The concentration of maternal

plasma arginine increased following arginine treatment (182.6±14.4

vs. 92.3±9.6 µmol/l, Fig. 6B). In

the arginine-treated group, the hearts of the embryos with no

notable gross abnormality demonstrated enlarged heart cavities and

thinner heart walls (Fig. 6C),

compared with the control. In the lysine-treated group, no obvious

deformity was observed.

| Table IIIEffects of arginine/lysine treatment

on mice. |

Table III

Effects of arginine/lysine treatment

on mice.

| Group | Pregnant mice,

n | Embryos, n | Mean litter

size | Deformity

ratea, % (n) |

|---|

| Control | 6 | 39 | 6.5±1.05 | 0 (0) |

| Arginine | 6 | 26 |

4.3±1.03b |

30.8(8)c |

| Lysine | 6 | 36 | 6.0±1.41 | 0 (0) |

Amino acids in maternal peripheral

blood are not significantly altered between CHD and control

group

As there were several amino acids changes in

amniotic fluid cells metabonomics, the present study investigated

whether the amino acids change in human maternal peripheral blood

between CHD and control group. Compared with control group, glycine

and glutamine were downregulated by 17.3% (503.8±147.1 vs.

608.7±266.8 µmol/l, Table IV) and

upregulated by 6.7% (381.0±70.1 vs. 357.8±77.30 µmol/l),

respectively. Therefore, these amino acids cannot be used as

non-invasive markers for CHD screening.

| Table IVMean concentration of amino acids in

maternal peripheral blood. |

Table IV

Mean concentration of amino acids in

maternal peripheral blood.

| Amino acid | Control (n=96),

µM | CHD (n=69), µM | T-value | P-value |

|---|

| Ala | 504.3±142.0 | 472.9±127.2 | 1.489 | 0.138 |

| Val | 177.7±34.7 | 176.6±33.8 | 0.217 | 0.828 |

| Gly | 608.7±266.8 | 503.8±147.1 | 3.230 | 0.002 |

| Gln | 357.8±77.3 | 381.0±70.1 | -2.011 | 0.046 |

| Glu | 159.1±48.9 | 144.7±54.6 | 1.740 | 0.084 |

| Orn | 106.5±18.9 | 105.6±17.1 | 0.314 | 0.754 |

| Leu | 181.0±40.7 | 174.1±43.9 | 1.013 | 0.313 |

| Arg | 11.8±3.9 | 12.4±4.8 | -0.75 | 0.455 |

| Met | 13.4±5.2 | 13.3±5.5 | 0.041 | 0.968 |

| Phe | 73.1±26.4 | 72.2±19.5 | 0.248 | 0.804 |

| Tyr | 57.5±12.6 | 54.7±15.7 | 1.220 | 0.225 |

| Cit | 16.8±3.2 | 17.4±4.5 | -0.913 | 0.363 |

| Pro | 145.2±37.6 | 135.9±33.0 | 1.692 | 0.093 |

| HArg | 11.4±3.1 | 11.2±2.8 | 0.518 | 0.605 |

| Lys | 49.5±9.5 | 49.9±7.8 | -0.289 | 0.773 |

Discussion

Samples from fetuses with CHD had different

metabolic profiles compared with controls. It was determined that

amino acids serve an important role in heart development. When

arginine was used to treat the pregnant mice, the embryos

demonstrated increased malformation rate. The embryonal heart

cavity became larger and the heart wall became thinner. The present

study may provide insight into the pathophysiology of CHD.

The high incidence of CHD have prompted

investigation into its pathogenesis to identify early screening

indicators (1). With the rapid

development of high-throughput sequencing technology, an increasing

number of copy number variations and gene mutations have been

identified in CHD (2,3). However, only one-third of the cases

can be explained by genetics (2,3). The

wide application of metabolomics facilitates investigation of

potential CHD pathogenesis or early screening biomarker.

There are three primary metabolomics detection

platforms, namely LC-MS, gas chromatography-MS (GC-MS) and nuclear

magnetic resonance (NMR) (14,15).

Because NMR has defects, such as relatively low sensitivity, poor

selectivity and limited metabolite coverage, MS platforms with high

sensitivity and specificity are more commonly used (14-16).

Compared with GC-MS, LC-MS has advantages: The samples are

separated at room temperature without special treatment (GC-MS

often requires derivatization). In addition, the range of the

molecular weights of the tested substances is wider. Moreover, it

has higher sensitivity and can detect more trace substances. Thus,

LC-MS has a wide range of applications (14-16).

Several types of biological samples (amniotic fluid, plasma, urine)

have been used for metabolomics screening (9). The present study used cells; as the

basic functional unit of life, cells directly reflect the levels of

intracellular metabolism and are more conducive to discover the

potential pathogenic mechanisms.

To explore the possibility of arginine and other

amino acids as metabolic markers, the present study detected the

concentration of amino acids in maternal peripheral blood. There

was no significant difference between CHD and control group,

indicating plasma amino acids cannot be used as non-invasive

markers for CHD screening. Although the present study demonstrated

a number of differential metabolites in amniotic fluid cell

metabonomics, there were limitations. First, the present study

could not determine whether the altered metabolites were the result

or the cause of CHD. More studies are needed to clarify this.

Second, the sample size was not sufficiently large, and the type of

CHD was only concentrated in the ventricular septal defect. A

comprehensive, large-scale multi-center study is needed.

L-lysine, an essential amino acid, was the most

notable differential metabolite identified in CHD. Humans receive

L-lysine from daily food such as meat, cereal grains or legumes

(17). L-lysine is taken up into

cells by cationic transport system y+ (18). Lysine has important functions in the

promotion of human physiological development and fatty acid

oxidation (19). It promotes brain

development and fat metabolism and prevents cell degeneration.

Shimomura et al (20) found

that dietary L-lysine exerts protective effects against vascular

calcification in uremic rats. The addition of lysine to the diet

can manage osteoporosis (21).

L-lysine also has beneficial hemodynamic effects and decreases

nitric oxide levels in endotoxemic rats (22). Lysine acetylsalicylate can recover

sepsis-induced lung tissue damage in rats (23), and L-lysine suppresses acute

pancreatitis in mice (24).

L-lysine ameliorates sepsis-induced acute lung injury in a

lipopolysaccharide-induced mouse model (25). Abnormalities in lysine degradation

are involved in the early development of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy

in pressure-overloaded rats (19).

In the present study, lysine did not cause any difference in the

litter size and deformity rate from the controls and embryonal

hearts also did not show obvious malformation (the data not shown

in this study). Although lysine has a range of functions, more

studies are needed to clarify its role in heart development.

L-arginine, homoarginine, L-ornithine, L-asparagine

and L-glutamine belong to the arginine family and participate in

the urea cycle (26). Glutamine,

glutamate and arginine can regulate nutrient intake and neonatal

development through norepinephrine, glucagon-like peptide-1,

mammalian target of rapamycin, mitogen-activated protein kinase and

autophagy (26,27). Arginine is an important nutrient

with regulatory roles in neonatal growth (28,29).

Rat studies have indicated that supplementing the maternal diet

with arginine and glutamine improves embryo implantation and

survival, enhances litter size and increases the number and birth

weight of surviving embryos (30,31).

In addition, arginine and glutamine affect gene expression to

improve antioxidant responses and DNA transcription (32,33).

Plasma homoarginine levels have been reported to show a declining

trend in patients with complex CHD compared with healthy controls

(34). Therefore, homoarginine may

be a prognostic indicator of CHD. Cedars found that plasma

concentrations of multiple amino acids differ between adult

patients with CHD and healthy controls (35). Although the numerical difference is

not large, a metabolite cluster containing amino acids and

metabolites is associated with negative clinical outcomes (35). A total of 11 amino acids (including

arginine, lysine, asparagine and glutamine) are upregulated in the

cardiac tissues of children with cyanotic CHD (36) compared with those with acyanotic

CHD. Yu et al (37) found

that glutamine and glutamate have considerable diagnostic value for

pediatric patients with CHD patients. Li et al (9) found that the concentrations of uric

acid and proline in the amniotic fluid are significantly elevated

in patients with CHD. In the present study, when pregnant mice were

treated with arginine at the dose of 1.5 mg/g body weight, the

litter size decreased and the embryo deformity rate increased. The

embryonal hearts demonstrated enlarged heart cavities and thinner

heart walls. The present study only tested the maternal plasma

arginine concentration following arginine treatment and did not

test the concentration in the placenta and heart in the embryo.

Thus, changes in amino acid levels may serve an important role in

the occurrence and development of CHD. Future studies should focus

on metabolic reprogramming to clarify the potential mechanism of

arginine-induced cardiac malformation.

In summary, differential metabolites were identified

in CHD using metabolomics. The levels of numerous types of amino

acids were significantly elevated, indicating that they may serve

an important role in heart development. Arginine treatment of

pregnant mice resulted in embryonal heart defects.

Supplementary Material

Hierarchical clustering results of the

differential metabolites. Each line represents a metabolite. The

deeper the red, the higher its content in the measured sample; the

deeper the blue, the lower its content in the measured sample. CHD,

congenital heart disease.

Amino acid detection mass spectrometry

parameters.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the People's

Livelihood Science and Technology Project of Liaoning Province

(grant nos. 2022020806-JH2/1015 and 2021JH2/10300123).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ZL collected the samples and wrote the manuscript.

CC performed animal experiments. JL analyzed the data. GL

interpreted the data, performed experiments and revised the

manuscript. CQ designed the study and revised the manuscript. ZL

and GL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University

(approval nos. 2022PS307K and 2024PS202K). All participants

provided written informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhang Y, Wang J, Zhao J, Huang G, Liu K,

Pan W, Sun L, Li J, Xu W, He C, et al: Current status and

challenges in prenatal and neonatal screening, diagnosis, and

management of congenital heart disease in China. Lancet Child

Adolesc Health. 7:479–489. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Zaidi S and Brueckner M: Genetics and

genomics of congenital heart disease. Circ Res. 120:923–940.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Jin SC, Homsy J, Zaidi S, Lu Q, Morton S,

DePalma SR, Zeng X, Qi H, Chang W, Sierant MC, et al: Contribution

of rare inherited and de novo variants in 2,871 congenital heart

disease probands. Nat Genet. 49:1593–1601. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lai T, Xiang L, Liu Z, Mu Y, Li X, Li N,

Li S, Chen X, Yang J, Tao J and Zhu J: Association of maternal

disease and medication use with the risk of congenital heart

defects in offspring: A case-control study using logistic

regression with a random-effects model. J Perinat Med. 47:455–463.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Liu X, Nie Z, Chen J, Guo X, Ou Y, Chen G,

Mai J, Gong W, Wu Y, Gao X, et al: Does maternal environmental

tobacco smoke interact with social-demographics and environmental

factors on congenital heart defects? Environ Pollut. 234:214–222.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Rocha LA, Araujo Júnior E, Nardozza LM and

Moron AF: Screening of fetal congenital heart disease: The

challenge continues. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 28:V–VII.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Menon R, Jones J, Gunst PR, Kacerovsky M,

Fortunato SJ, Saade GR and Basraon S: Amniotic fluid metabolomic

analysis in spontaneous preterm birth. Reprod Sci. 21:791–803.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Romero R, Espinoza J, Gotsch F, Kusanovic

JP, Friel LA, Erez O, Mazaki-Tovi S, Than NG, Hassan S and Tromp G:

The use of highdimensional biology (genomics, transcriptomics,

proteomics, and metabolomics) to understand the preterm parturition

syndrome. BJOG 113 Suppl. 3:118–135. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Li Y, Sun Y, Yang L, Huang M, Zhang X,

Wang X, Guan X, Yang P, Wang Y, Meng L, et al: Analysis of

biomarkers for congenital heart disease based on maternal amniotic

fluid metabolomics. Front Cardiovasc Med. 8(671191)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Du Y, Chang W, Gao L, Deng L and Ji WK:

Tex2 is required for lysosomal functions at TMEM55-dependent ER

membrane contact sites. J Cell Biol. 222(e202205133)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ishitobi K, Kotani H, Iida Y, Taniura T,

Notsu Y, Tajima Y and Harada M: A modulatory effect of L-arginine

supplementation on anticancer effects of chemoimmunotherapy in

colon cancer-bearing aged mice. Int Immunopharmacol.

113(109423)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Siriviriyakul P, Sriko J, Somanawat K,

Chayanupatkul M, Klaikeaw N and Werawatganon D: Genistein

attenuated oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in

L-arginine induced acute pancreatitis in mice. BMC Complement Med

Ther. 22(208)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Bianchini Narde M, Belli Cassa Domingues

EL, Ribeiro Gonçalves K, Lomar Viana M, Santos Zanini M, Geraldo de

Lima W, Bahia MT and Matos Dos Santos F: L-arginine supplementation

increases cardiac collagenogenesis in mice chronically infected

with Berenice-78 trypanosoma cruzi strain. Parasitol Int.

83(102345)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Emwas AH, Roy R, McKay RT, Tenori L,

Saccenti E, Gowda GAN, Raftery D, Alahmari F, Jaremko L, Jaremko M

and Wishart DS: NMR spectroscopy for metabolomics research.

Metabolites. 9(123)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Marchev AS, Vasileva LV, Amirova KM,

Savova MS, Balcheva-Sivenova ZP and Georgiev MI: Metabolomics and

health: From nutritional crops and plant-based pharmaceuticals to

profiling of human biofluids. Cell Mol Life Sci. 78:6487–6503.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Azad RK and Shulaev V: Metabolomics

technology and bioinformatics for precision medicine. Brief

Bioinform. 20:1957–1971. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Tomé D and Bos C: Lysine requirement

through the human life cycle. J Nutr. 137(Suppl 2):1642S–1645S.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Boldt A, Gergs U, Frenker J, Simm A,

Silber RE, Klöckner U and Neumann J: Inotropic effects of L-lysine

in the mammalian heart. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol.

380:293–301. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Liu J, Hu J, Tan L, Zhou Q and Wu X:

Abnormalities in lysine degradation are involved in early

cardiomyocyte hypertrophy development in pressure-overloaded rats.

BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 21(403)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Shimomura A, Matsui I, Hamano T, Ishimoto

T, Katou Y, Takehana K, Inoue K, Kusunoki Y, Mori D, Nakano C, et

al: Dietary L-lysine prevents arterial calcification in

adenine-induced uremic rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 25:1954–1965.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Fürst P: Dietary L-lysine supplementation:

A promising nutritional tool in the prophylaxis and treatment of

osteoporosis. Nutrition. 9:71–72. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Liaudet L, Gnaegi A, Rosselet A, Markert

M, Boulat O, Perret C and Feihl F: Effect of L-lysine on nitric

oxide overproduction in endotoxic shock. Br J Pharmacol.

122:742–748. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Huang WD, Wang JZ, Lu YQ, DI YM, Jiang JK

and Zhang Q: Lysine acetylsalicylate ameliorates lung injury in

rats acutely exposed to paraquat. Chin Med J (Engl). 124:2496–2501.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Al-Malki AL: Suppression of acute

pancreatitis by L-lysine in mice. BMC Complement Altern Med.

15(193)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhang Y, Yu W, Han D, Meng J, Wang H and

Cao G: L-lysine ameliorates sepsis-induced acute lung injury in a

lipopolysaccharide-induced mouse model. Biomed Pharmacother.

118(109307)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wu G: Functional amino acids in nutrition

and health. Amino Acids. 45:407–411. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kim J, Song G, Wu G, Gao H, Johnson GA and

Bazer FW: Arginine, leucine, and glutamine stimulate proliferation

of porcine trophectoderm cells through the MTOR-RPS6K-RPS6-EIF4EBP1

signal transduction pathway. Biol Reprod. 88(113)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Wu G, Bazer FW, Dai Z, Li D, Wang J and Wu

Z: Amino acid nutrition in animals: Protein synthesis and beyond.

Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2:387–417. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Lin G, Wang X, Wu G, Feng C, Zhou H, Li D

and Wang J: Improving amino acid nutrition to prevent intrauterine

growth restriction in mammals. Amino Acids. 46:1605–1623.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Wu G, Bazer FW, Satterfield MC, Li X, Wang

X, Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Dai Z, Wang J and Wu Z: Impacts of

arginine nutrition on embryonic and fetal development in mammals.

Amino Acids. 45:241–256. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zeng X, Huang Z, Mao X, Wang J, Wu G and

Qiao S: N-carbamylglutamate enhances pregnancy outcome in rats

through activation of the PI3K/PKB/mTOR signaling pathway. PLoS

One. 7(e41192)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Jobgen W, Fu WJ, Gao H, Li P, Meininger

CJ, Smith SB, Spencer TE and Wu G: High fat feeding and dietary

L-arginine supplementation differentially regulate gene expression

in rat white adipose tissue. Amino Acids. 37:187–198.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Wang J, Chen L, Li P, Li X, Zhou H, Wang

F, Li D, Yin Y and Wu G: Gene expression is altered in piglet small

intestine by weaning and dietary glutamine supplementation. J Nutr.

138:1025–1032. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Raedle-Hurst T, Mueller M, Meinitzer A,

Maerz W and Dschietzig T: Homoarginine-A prognostic indicator in

adolescents and adults with complex congenital heart disease? PLoS

One. 12(e0184333)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Cedars A, Manlhiot C, Ko JM, Bottiglieri

T, Arning E, Weingarten A, Opotowsky A and Kutty S: Metabolomic

profiling of adults with congenital heart disease. Metabolites.

11(525)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Dong S, Wu L, Duan Y, Cui H, Chen K, Chen

X, Sun Y, Du C, Ren J, Shu S, et al: Metabolic profile of heart

tissue in cyanotic congenital heart disease. Am J Transl Res.

13:4224–4232. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yu M, Sun S, Yu J, Du F, Zhang S, Yang W,

Xiao J and Xie B: Discovery and validation of potential serum

biomarkers for pediatric patients with congenital heart diseases by

metabolomics. J Proteome Res. 17:3517–3525. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|