Introduction

Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) is a molecular

diagnostic tool, based on next-generation sequencing (NGS)

technology, used in the field of cancer research and treatment. CGP

identifies various genetic alterations and mutations within the

tumor (1). Results from CGP guide

oncologists to make decisions about treatment options and select

targeted therapies tailored to the specific genetic alterations

present within the tumor. CGP examines a broad panel of genes,

detecting a wide range of genomic alterations. This includes point

mutations (such as PIK3CA p.E453Q and c.1357G>C),

insertions/deletions (indels; such as BRCA2 p.E1571Gfs*3 and

c.4712_4713delAG), copy number variations (CNVs; such as

ERBB2 amplification, copy number:4) and gene fusions (such

as TBL1XR1/PIK3CA fusion). It can detect multiple genetic

alterations in a single test, reducing the need for multiple

individual tests. CGP is an application of NGS that specifically

focuses on a detailed analysis of the genetic profile of patients,

and can provide a broad overview of the genomic alterations in a

tumor. Consequently, precision, efficiency and therapeutic guidance

are potential advantages of CGP, which has been advocated for

advanced-stage cancers (2-5).

A large-sized panel can provide more opportunities for matching

patients to targeted therapies or for increased mutation detection

in clinical trials, while the use of CGP is limited by its high

cost, data complexity and increased turnaround time.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a specific

subtype of breast cancer characterized by the absence of three

deterministic receptors commonly found in other breast cancers:

Estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human

epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). TNBC cells lack the

expression of these three receptors and do not rely on them for

growth. TNBC accounts for 10-20% of all breast cancer cases world

(6), and is more commonly diagnosed

in younger (#x003C;40 years old) women, African-American women and

those with a family history of breast cancer (7). TNBC is known for its aggressive

behavior and tends to grow and spread quickly, while it is also

associated with a higher risk of recurrence and metastasis

(8), and ~40% of people with stage

I to stage III TNBC will exhibit tumor recurrence after standard

treatment (9). Treatment options

for TNBC often involve chemotherapy, as endocrine therapies and

anti-HER2 therapies that target ER, PR or HER2 are not effective

due to the absence of these receptors (8). The prognosis for TNBC varies depending

on factors such as the diagnosed stage and response to treatment

(10). Due to its aggressiveness,

there is an unmet need to identify actionable targets such as

AKT1, BRCA1/2, PALB2, ERBB2,

PIK3CA and PTEN, for patients with TNBC (11,12).

Research focusing on developing targeted therapies

for TNBC continues to improve treatment outcomes and broaden

therapeutic options (13,14). For example, biomarker-driven

therapies are being applied with the advent of immune checkpoint

inhibitors, poly-adenosine-diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP)

inhibitors, selective PI3K and AKT inhibitors, as well as

antibody-drug conjugates, which target immune-enriched, DNA

repair-deficient, PI3K/AKT/mTOR-activated and surface

antigen-overexpressed TNBC, respectively. However, most umbrella

trials for advanced breast cancer are not TNBC-specific, while a

recent review highlighted that large-sized panels could identify

novel markers, emphasizing the potential of CGP to uncover

actionable targets in TNBC (3).

Commercialized CGP assays may be beneficial;

however, the size of the panel to be employed to deliver the most

optimal coverage of actionable genes for TNBC remains to be

explored. Some studies comparing distinct CGP platforms and

resulting biomarkers have been conducted for gastric, head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, ovarian and

prostate cancer, but rarely for TNBC (15,16).

In the present study, a subgroup of patients with TNBC from the

Veterans General Hospital TAipei-Yung-Ling foundation sinO-canceR

(VGH-TAYLOR) study was used (17).

TNBC samples were initially assayed using a medium-sized CGP panel,

and the remaining specimens of nucleic acid were re-sequenced with

a large-sized GCP panel. The aim of the present study was to

investigate whether a larger CGP panel offers clinically

significant advantages in detecting actionable variants for TNBC

management compared with a medium-sized panel.

Materials and methods

Study overview

The present study was conducted in two phases: The

first phase involved prospective and retrospective tissue

collection as part of the VGH-TAYLOR study (medium-sized panel).

The second phase involved the reuse of biobanked samples from the

VGH-TAYLOR study (large-sized panel). The study was approved by the

Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital

(approval nos. 2021-01-007B and 2023-08-002B; Taipei, Taiwan).

Participants provided written informed consent for both phases of

the study.

The VGH-TAYLOR study was designed to examine the

genetic profiling of different subtypes of breast cancer in Taiwan

(17). The prospective study

comprised diverse clinical scenarios of breast cancer: i) Group 1,

planned to receive first-line surgery followed by adjuvant therapy

(1A) or exhibited early relapse within 3 years of diagnosis (1B);

ii) group 2, planned to receive first-line neoadjuvant therapy

followed by surgery; and iii) group 3, exhibited de novo

stage IV (3-I) or recurrence beyond 3 years of diagnosis

(3-II).

In addition, a retrospective cohort with biobanked

samples from recurrent/metastatic breast cancers or patients with

non-pathological complete response following neoadjuvant therapy

was also included (18-21).

Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of TNBC from the

VGH-TAYLOR study, availability of sufficient biobanked nucleic acid

and willingness to sign informed consent. Patients without residual

samples and those unwilling to participate in the retesting program

were excluded. A total of 120 female patients were screened, with

108 cases included for comprehensive genomic profiling. The age

range was 27 to 84 years, with a mean ± SD age of 56.1±12.8 years.

All enrolled subjects were treated according to contemporary

guidelines and underwent regular follow-up (22,23).

Regarding immunohistochemistry (IHC) testing, ER and PR were scored

by percentage of nuclear labeling (0-100%). HER2 expression was

scored using a 0 to 3+ membrane staining intensity score (24). Hormone receptor positivity was

defined by either ER or PR with ≥1% of tumor cells exhibiting

nuclear staining while HR-negative breast cancer was defined by the

absence of ER and PR on the cancer cells. HER2 overexpression was

indicated by either a 3+ (positive) or 2+ (equivocal) IHC score

with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) amplification

(25). For patients with equivocal

IHC scoring of HER2, a negative FISH result was a prerequisite. All

patients of the VGH-TAYLOR study were enrolled between November

2018 and December 2021 from the Comprehensive Breast Health Center,

Taipei Veterans General Hospital, a tertiary referral medical

center at Taipei, Taiwan.

Samples and nucleic acid

preparation

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples were

collected after obtaining informed consent. For consistent results,

a fixation time of 6-48 h in 10% neutral buffer formalin at room

temperature for breast cancer biomarker testing was performed. At

least seven unstained tumor sections with 10 µm in thickness were

retrieved, with one used for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining and six used for nucleic acid extraction. Hematoxylin (3.5

min at room temperature) was used for nuclear staining, and eosin

(60 sec at room temperature) was used for cytoplasmic staining,

allowing for differentiation of cellular components.

H&E-stained slides were reviewed to ascertain the presence of

adequate breast cancer cells (>70% of cancer composition).

Paraffin was removed by xylene and ethanol serial

washes. Nucleic acid was extracted from 5-µm sections with the

QIAmp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (cat. no. 56404; Qiagen, Inc.) or AllPrep

DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (cat. no. 80234; Qiagen, Inc.), while quality

control and concentration were checked and determined using the

Qubit fluorimeter (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

Qubit dsDNA HS and Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kits (cat. nos. Q32851 and

Q32850; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). In the current study,

treatment-naïve cancerous tissue was used for NGS. Targeted

sequencing for the TruSight Oncology 500 (TSO500) panel was

conducted on residual specimens from the VGH-TAYLOR study.

The storage conditions for the remaining nucleic

acids after CGP aimed at maintaining their integrity for potential

future use. Therefore, nuclear acid was stored at -80˚C in

Tris-EDTA buffer or nuclease-free water. Repeated freeze-thaw

cycles were avoided. A total of 120 pairs of DNA/RNA were tested

for integrity and 108 passed quality control (QC) matrices for NGS

experiments: QC parameters for TSO500 included DNA integrity number

>7 and RNA integrity number >7, size distribution of 200-500

bp for library construction and >90% on-target enrichment with

uniform coverage. Under optimal storage conditions with minimal

nucleic acid degradation, a ~90% success rate (108 out of 120

paired DNA/RNA samples) in sequencing with quality metrics was

reported.

Oncomine comprehensive panel

The Ion Torrent Oncomine Comprehensive Assay Panel

v3 (OCP; cat. no. A35805; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used

as the default CGP for the VGH-TAYLOR study, which enabled the

detection of 161 cancer-related genes and the identification of

single nucleotide variants (SNVs), CNVs, gene fusions and indels. A

total of 10 ng of DNA and RNA sample input was required. Libraries

were generated according to the standard protocols, which was

constructed with the Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit Plus (cat. no.

4488990; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), and were multiplexed for

templating on the Ion OneTouch 2 System and subsequently sequenced

on the Ion GeneStudio S5 Prime System (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) using the Ion 318 Chip Kit (cat. no. 488146; Thermo Fisher

Scientific Inc.) with single-end semiconductor-based sequencing and

a read length of 200 bp, according to the manufacturer's

instructions (guide MAN0015885 Revision C of Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Sequencing data were analyzed, aligned and

annotated through Torrent Suite v5.10.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) and Ion Reporter v5.10 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

software with the default Coverage Analysis (v5.10.0.3), Sample ID

(v5.10.0.1) and Variant Caller (v5.10.0.18) plugin. Variants were

further analyzed and interpreted for clinical actionability using

the Oncomine Knowledgebase Reporter (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) database. The coverage metrics indicated that the number of

mapped reads ranged from 4 to 6 million, with a mean depth of

1,100-1,600 times.

TSO500

TSO500 (cat. no. 20032626; Illumina, Inc.) was

designed to identify known and emerging tumor biomarkers, using

both DNA and RNA from tumor samples. These pan-cancer biomarkers

aligned with key guidelines and clinical trials (22,23),

including 523 genes for assessment of DNA and RNA variant types,

plus microsatellite instability, tumor mutational burden and

homologous recombination deficiency (optional). Libraries were

prepared according to the manufacturer's guidelines from up to 80

ng DNA and 40 ng of RNA, using the TSO 500 library prep kit (cat.

no. 20028216; Illumina, Inc.). Adapter ligation with unique

molecular identifiers (UMIs) was performed with target fragments

amplified and indexed. NGS was performed with a NextSeq 2000

sequencing system optimized for a minimum read length of 2x101 bp,

operated by the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine of

the Taipei Veterans General Hospital using the NextSeq 1000/2000 P2

Reagents (300 cycles) v3 (Illumina, Inc.). Data were analyzed with

the TSO500 Local App v2.2 (Illumina, Inc.), and variant call format

files were further processed and annotated with the PierianDx

software version CGW_v6.20 (PierianDx), which offered an integrated

interpretation. The read collapsing analysis step executed an

algorithm that collapses sets of reads (known as families) with

similar genomic locations into representative sequences using UMI

tags. Median exon fragment coverage across all exon bases was

≥150.

Benchmark comparisons

The difference in sequencing technology between

amplicon-based (OCP) and hybrid capture-based (TSO500) methods has

implications for detecting genetic variants, especially in

homopolymer regions, consisting of a series of consecutive

identical bases (26).

Hybridization capture-based approaches show better uniformity,

which can be relevant for detecting variants in homopolymer

regions. Amplicon-based methods are faster and cost-effective but

prone to errors in homopolymer regions. Hybrid capture methods are

more reliable for these regions due to uniform coverage and reduced

PCR bias, but they are more resource-intensive. Final reports from

the medium- (OCP) and large-sized (TSO500) panels and accompanied

tab-separated values files were collected. Variants reported from

actionable genes were the primary endpoints in the current study.

Clinical actionability was defined by the joint consensus of the

Association for Molecular Pathology, American Society of Clinical

Oncology and College of American Pathologists, published in

2017(27). Additional annotations

for actionability and OncoPrinter (28,29)

visualization were conducted using the OncoKB database (30) and European Society for Medical

Oncology (ESMO) Scale for Clinical Actionability of molecular

Targets (ESCAT) criteria (11,12).

Clinical actionability was categorized as follows: i) Tier I,

actionability indicated an alteration-drug match associated with

improved outcome in clinical trials; ii) tier II, anti-tumor

activity was associated with the matched alteration-drug but lacked

prospective outcome data; and iii) tier III, the matched

drug-alteration led to clinical benefit in another tumor type other

than the tumor of interest. Polymorphisms were identified through

population databases, such as the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

Database (31), the Genome

Aggregation Database (32), 1000

Genomes Project and Exome Aggregation Consortium (33). Variants with minor allele frequency

>1% were excluded. Variants outside the targeted regions of the

sequencing panel were masked. Considering the sequencing depth, a

10% variant allele frequency (VAF) threshold assumed standard

sequencing depths (500-1,000 times). The limit of detection was set

to 5% for SNVs/indels and VAF #x003C;10% was considered a low-VAF

status. An average copy number ≥4 was interpreted as a gain

(amplification) and #x003C;1 as a loss (deletion). The concordance

of filtered actionable genes (AKT1, BRCA1/2,

PALB2, ERBB2, PIK3CA and PTEN) and

TP53 based on the original reports between the two panels

was calculated (concordant variants divided by the sum of both

concordant and discordant variants) and reported.

Data description and clinical

usage

ESCAT-defined actionable genes, including fusions,

amplifications, copy number gains, point mutations and indels, were

extracted for downstream analysis. Categorical variables are

presented as numbers and percentages. Official reports from the Ion

Reporter and the Oncomine Knowledgebase Reporter, as well as those

from Pierian Dx software were released to all participants when

requested. In addition, primary care physicians received the same

reports once they were available, augmenting clinical decision

making.

Results

Study population and targeted

actionable genes

A total of 108 patients with breast cancer from the

VGH-TAYLOR study with adequate remaining nucleic acid (both DNA and

RNA) were recalled. After explaining the purpose of this

re-sequencing study, all participants signed informed consent forms

and their specimens were assayed with the large-sized CGP, TSO500

panel. There were 54 patients in group 1A, 6 in group 1B, 25 in

group 2, 5 in group 3-I, 7 in group 3-II and 11

biobank/retrospective cohort breast cancer samples. Early-stage

breast cancer (groups IA and 2) constituted the majority of samples

(73.1%, n=79). Four patients initially classified as TNBC at the

time of enrollment were re-tested by FISH and found to be

HER2-positive. Due to discrepancy in the interrogated genes (523

vs. 161 genes), only actionable genes listed by the ESCAT criteria

for breast cancer were analyzed, as follows: i) Tier IA:

ERBB2 amplification, BRCA1/2 germline mutation and

PIK3CA mutation; ii) tier IC: NTRK translocation;

iii) tier IIA: PTEN loss and ESR1 mutation; iv) tier

IIB: AKT1 mutation and ERBB2 mutation; v) tier IIIA:

BRCA1/2 somatic mutation and MDM2 amplification; and

vi) Tier IIIB: ERBB3 mutation (11,12).

Mutational landscape of actionable

genes with TSO500

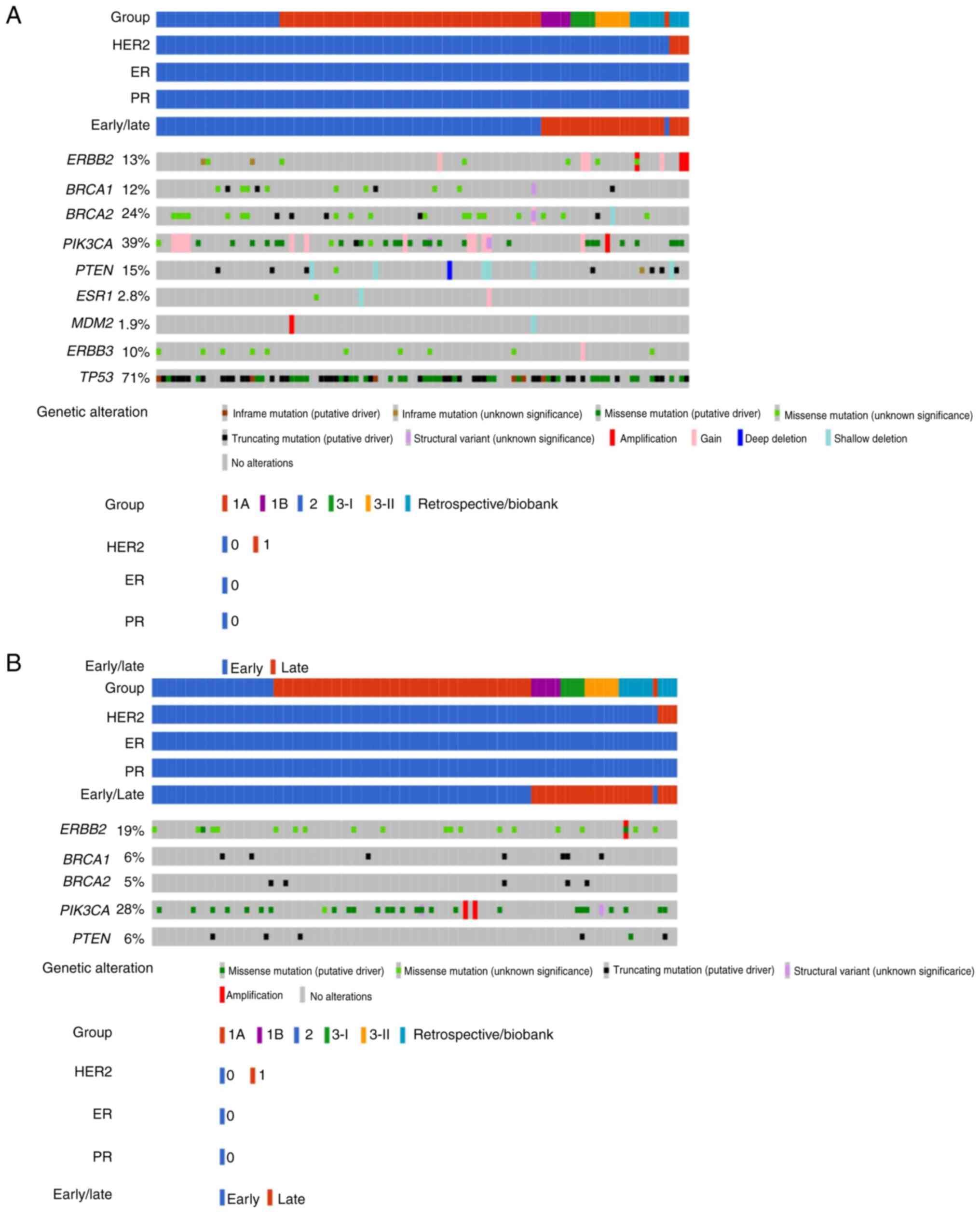

Fig. 1A shows the

mutational landscape of ESCAT-defined actionable genes among

Taiwanese patients with TNBC examined with TSO500. Among 108

Taiwanese patients with breast cancer (all samples were TNBC except

for four samples that were HER2-positive), PIK3CA was the

most common actionable gene (39%, n=42), including fusion,

amplification, copy number gain and point mutation, followed by

BRCA2, including fusion, copy number gain, heterozygous

loss, truncating and point mutation (24%, n=26). BRCA1

variants, including fusions, truncating and point mutations were

detected in 12% (n=13) of samples. ERBB2 amplification, copy

number gain, in-frame and point mutations were identified in 13%

(n=14) of the study population. Importantly, among three breast

cancer samples with HER2 amplification reported by TSO500, two

coincided with the four clinically HER2-positive (overexpression)

cases.

PTEN mutations including

heterozygous/homozygous loss and truncating/in-frame/point

mutations were reported in 15% (n=16) of breast cancer samples.

Copy number gain and point mutations in ERBB3 were

identified in 10% (n=11) of the samples, while ESR1 (2.8%,

n=3; copy number gain/heterozygous loss and point mutation) and

MDM2 variants (1.9%, n=2; amplification and heterozygous

loss) were infrequently mutated in the Taiwanese population. No

NTRK translocations were reported. Table SI presents the actionable mutations

assayed with TSO500 CGP.

Mutational landscape of actionable

genes with OCP

Fig. 1B shows the

mutational landscape of actionable genes reported by OCP. Compared

with TSO500, OCP reported a higher number of ERBB2 variants

(19 vs. 13%), most of which came from higher proportion of missense

mutations with unknown significance. Of the four clinical

HER2-positive breast cancer samples, none reported a HER2

alteration, except for another HER2-equivocal case associated with

an ERBB2 I665V missense mutation, which was a variant of

uncertain significance (VUS). Conversely, the frequencies of

BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants were lower than those

reported from TSO500 (BRCA1, 6 vs. 12%; and BRCA2, 5

vs. 24%). PIK3CA variants and PTEN mutations were

also less frequent than those with TSO500 (28 vs. 39% and 6 vs.

15%, respectively). No alterations were identified by OCP in

ESR1, MDM2 and ERBB3. Table SII details the actionable mutations

identified with OCP.

Comparisons of reported actionable

variants between OCP and TSO500

For benchmark comparisons, the four HER2-positive

samples were excluded, and the analysis was focused on tumor DNA

sequence variants from actionable genes. Amino acid change (protein

coordinate), genomic and transcript-dependent cDNA coordinates were

used to identify variants reported as least once from either

TSO500, OCP or both (Table I).

Among 272 variants, 94 (34.6%) were identified by both platforms;

therefore, the concordance rate was slightly higher than one-third

based on the original reports. To understand the mechanisms

underpinning the high discordance between TSO500 and OCP, a manual

review of conflicting variants was conducted with all binary

alignment map (BAM) files visualized through integrative genomic

viewer by an author who is expert in precision oncology and

bioinformatics (34). Fig. S1 provides such an example.

| Table IVariants of actionable genes and

TP53 (n=202) reported from both the TSO500 and OCP. |

Table I

Variants of actionable genes and

TP53 (n=202) reported from both the TSO500 and OCP.

| Gene | Variant | ESCAT | Both platforms | TSO500 only |

|---|

| AKT1 | E17K | II-B | 3 | |

| BRCA1 | S405* | III-A | 1 | |

| | R1203* | III-A | 1 | |

| | S1286fs | III-A | 1 | |

| | S632fs | III-A | 1 | |

| | c.5470-1G>A | III-A | 1 | |

| | G1350C | III-A | | 1 |

| | M1783L | III-A | | 2 |

| | N909S | III-A | | 1 |

| | R1583K | III-A | | 1 |

| | R762S | III-A | | 1 |

| | S1389N | III-A | | 1 |

| | V191I | III-A | | 1 |

| | c.1A>G | III-A | | 1 |

| BRCA2 | S521* | III-A | 1 | |

| | E1571fs | III-A | 1 | |

| | N2135fs | III-A | 1 | |

| | C315S | III-A | | 1 |

| | F2254Yfs*6 | III-A | | 1 |

| | G2508S | III-A | | 1 |

| | G2901D | III-A | | 1 |

| | H523R | III-A | | 1 |

| | I1929V | III-A | | 4 |

| | N72S | III-A | | 2 |

| | P3292L, V2109I | III-A | | 1 |

| | R2108C | III-A | | 5 |

| | R2842H | III-A | | 1 |

| | V2109I | III-A | | 1 |

| | V2151Ffs*17 | III-A | | 1 |

| | V783A | III-A | | 1 |

| ERBB2 | L811V, L839R | II-B | 1 | |

| | L725S | | 1 | |

| | P1140A | | | 1 |

| | V743_ | | | 1 |

| | M744insHV | | | 1 |

| | Y742_ A745dup | | | 1 |

| NTRK1 | K167R | | | 1 |

| | M530T | | | 1 |

| | R190Q | | | 1 |

| | R190W | | | 1 |

| NTRk3 | D611E | | | 2 |

| PALB2 | K353fs | | 1 | |

| | A38G | | | 1 |

| | D498Y | | | 2 |

| | R825T | | | 2 |

| PIK3CA | E542K | I-A | 3 | |

| | E542K, E726K | I-A | 1 | |

| | E542Q, H1047R | I-A | 1 | |

| | E545K | I-A | 3 | |

| | E545Q, H1047Y | I-A | 1 | |

| | E726K | | 1 | |

| | G1049R | | 1 | |

| | H1047L | I-A | 2 | |

| | H1047R | I-A | 9 | |

| | N345I | | 1 | |

| | Q546R | | 1 | |

| | D350N | | | 1a |

| | D725N | | | 1b |

| PTEN | E150* | II-A | 1 | |

| | E43fs | II-A | 1 | |

| | P38fs | II-A | 1 | |

| | R130* | II-A | 1 | |

| | Q245* | II-A | 1 | |

| | c.1026+1G>A | II-A | 1 | |

| | V290Sfs*8 | II-A | | 1 |

| | G127_ G129del,

G129E | II-A | | 1 |

| TP53 | C176R | IV-A | 1 | |

| | C242Afs | IV-A | 1 | |

| | C275Y | IV-A | 1 | |

| | E271* | IV-A | 1 | |

| | E56Kfs | IV-A | 2 | |

| | F109Sfs | IV-A | 1 | |

| | G108Vfs | IV-A | 4 | |

| | G245S | IV-A | 2 | |

| | H179R | IV-A | 2 | |

| | H179Y | IV-A | 1 | |

| | H193P | IV-A | 1 | |

| | H193R | IV-A | 1 | |

| | H193Y | IV-A | 1 | |

| | H214Qfs | IV-A | 1 | |

| | K132N | IV-A | 1 | |

| | L111Dfs, R196 | IV-A | 1 | |

| | L111Ffs | IV-A | 1 | |

| | L194H | IV-A | 1 | |

| | L252Hfs | IV-A | 1 | |

| | P151S | IV-A | 1 | |

| | Q192* | IV-A | 1 | |

| | R158Lfs | IV-A | 1 | |

| | R175H | IV-A | 2 | |

| | R196* | IV-A | 2 | |

| | R248Q | IV-A | 4 | |

| | R248W | IV-A | 1 | |

| | R273H | IV-A | 4 | |

| | R282W | IV-A | 1 | |

| | R333Vfs | IV-A | 1 | |

| | R342* | IV-A | 1 | |

| | S149Pfs | IV-A | 1 | |

| | S166* | IV-A | 1 | |

| | S241F | IV-A | 1 | |

| | T253Pfs | IV-A | 1 | |

| | V147* | IV-A | 1 | |

| | W146* | IV-A | 1 | |

| | W53* | IV-A | 1 | |

| | W91* | IV-A | 1 | |

| | Y103Afs | IV-A | 1 | |

| | Y107* | IV-A | 1 | |

| | Y205D | IV-A | 1 | |

| | c.560-2A>T | IV-A | 1 | |

| | c.993+1G>A | IV-A | 1 | |

| | c.994-2A>C | IV-A | 1 | |

| | c.993+1G>A,

526T>A | IV-A | 1 | |

| | c.920-2A>G | IV-A | 1 | |

| | c.993+1G>T | IV-A | 1 | |

| | c.560-1G>A | IV-A | 1 | |

| | c.919+1G>T | IV-A | 1 | |

| | c.993+2T>G | IV-A | 1 | |

| | c.993+1G>A | IV-A | 1 | |

| | D281_ K292del | IV-A | | 1 |

| | E271Q | IV-A | | 1 |

| | F113V | IV-A | | 1 |

| | I251L | IV-A | | 1 |

| | L265P | IV-A | | 1 |

| | N131del | IV-A | | 1 |

| | P190L | IV-A | | 1 |

| | Q333E, R213* | IV-A | | 1 |

| | R213* | IV-A | | 4 |

| | T140_ C141

delinsS | IV-A | | 1 |

| | V157_ R158insL | IV-A | | 1 |

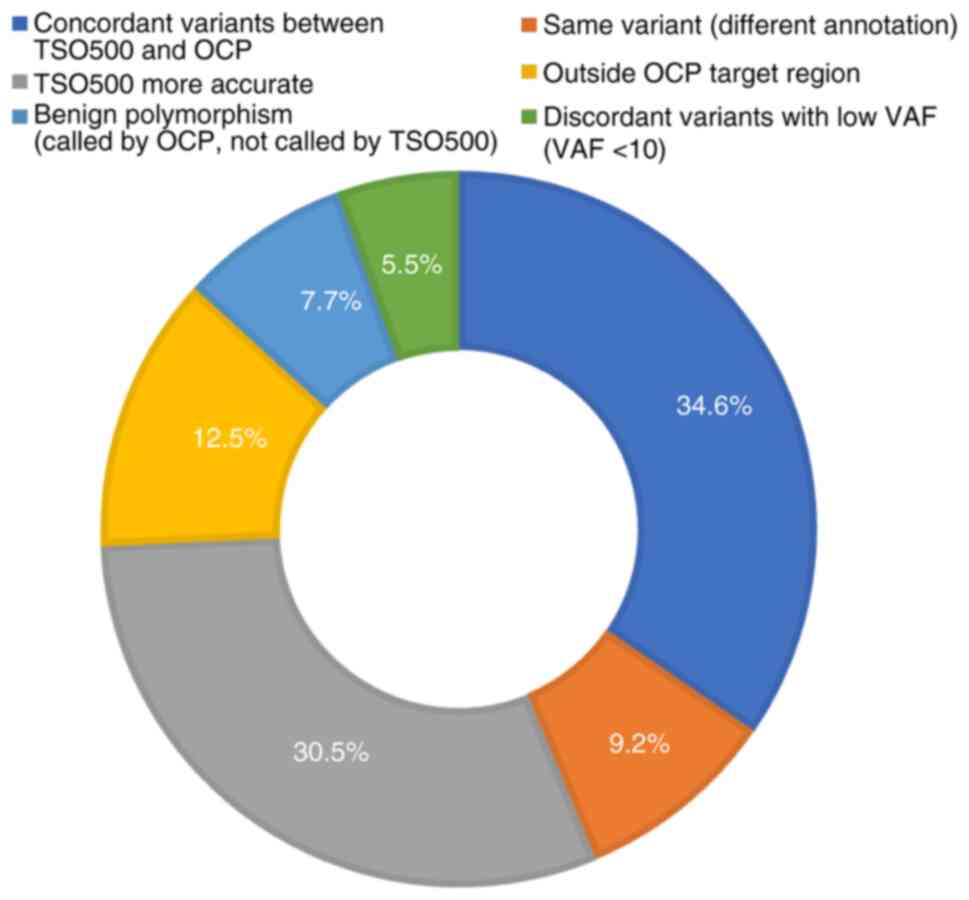

Fig. 2 shows the

interpretation categories of the comparison: A total of 25 (9.2%)

variants were the same with different annotations, 34 (12.5%) were

beyond the OCP targeted regions, 21 (7.7%) were benign

polymorphisms called by OCP but filtered out by TSO500, 15 (5.5%)

were discordant variants with low variant allele frequency

(VAF#x003C;10%) while TSO500 were more accurate in 83 cases

(30.5%). After discarding out-of-targeted region variants, benign

and low-VAF variants, the concordance rate approached 60% (119 of

202 variants, 58.9%) and the large-sized panel (TSO500) detected

more variants even for the same set of actionable genes and

TP53. It deserves notice that certain variants were called

by OCP but ignored by TSO500, which were proven to be homopolymer

regions, including variants in BRCA1 (n=2), BRCA2

(n=2), PALB2 (n=1) and TP53 (n=3), as well as a

misalignment with PTEN in one case and with TP53 in

two cases (data not shown).

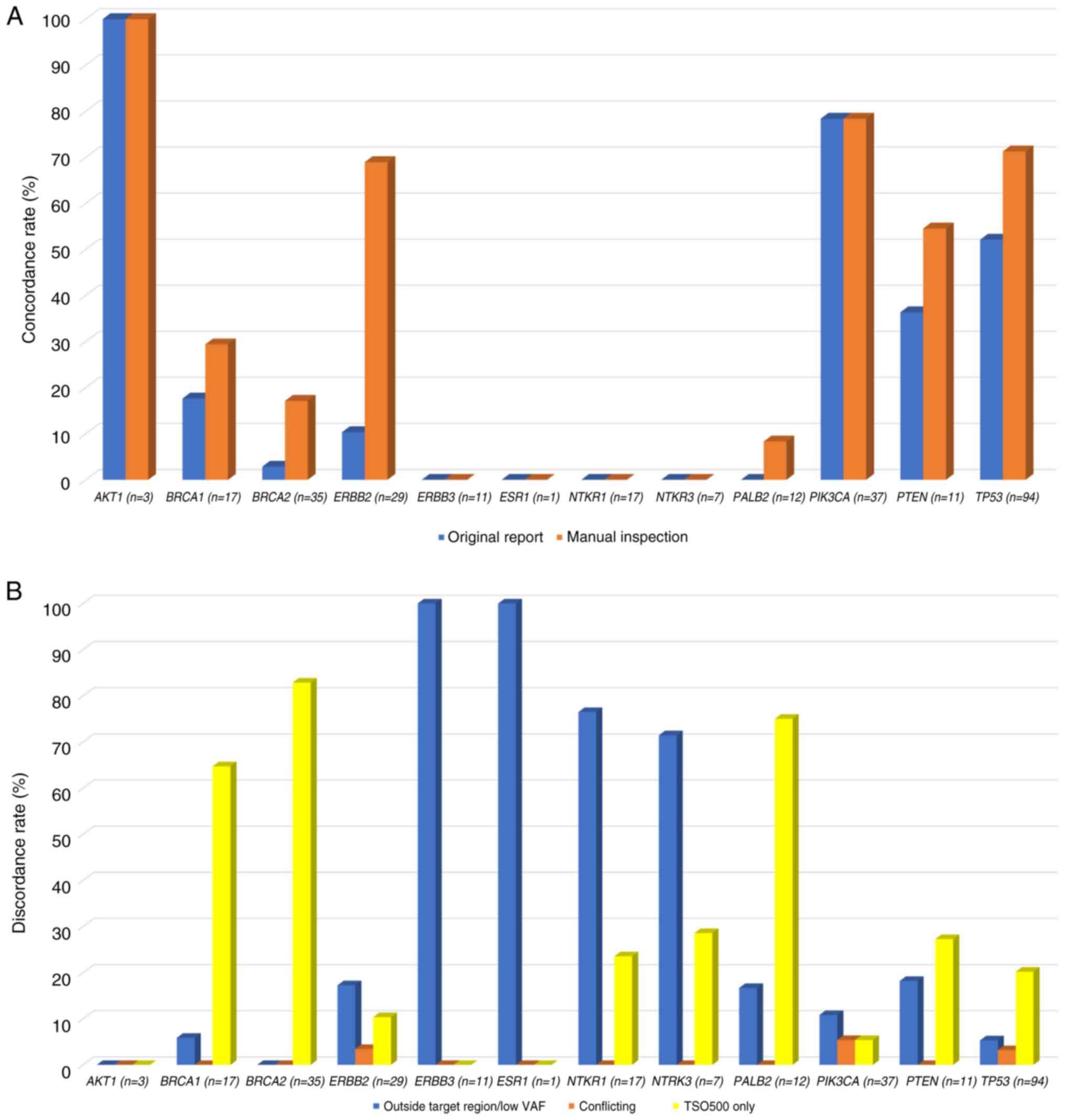

Fig. 3A and B and Table

II present concordant and discordant variants among actionable

genes between two CGP panels. AKT1 E17K exhibited a perfect

concordance (100%, n=3), followed by PIK3CA (78%, n=29) and

TP53 (52%, n=49). With manual corrections of polymorphism

and aliasing variants, the concordance of TP53 (71%, n=67),

ERBB2 (69%, n=20), PTEN (55%, n=6), BRCA1,

BRCA2 and PALB2 (29, 17 and 8%, respectively) was

enhanced substantially. Most of the discordance came from those

detected by TSO500 only, including variants in BRCA1 (65%,

n=11), BRCA2 (83%, n=29) and PALB2 (75%, n=9). Some

variants were undetectable by OCP due to out-of-target regions or

low VAF, which occurred in all ERBB3 and ESR1

variants, as well as NTRK1 and NTRK3 (76 and 71%,

respectively) variants. True conflicting calling results were rare,

including 3 TP53 (3%), 2 PIK3CA (5%) and 1

ERBB2 (3%) variants.

| Table IIDeconvolution of variants among

actionable genes and TP53 with concordant (original report

and manual inspection) and discordant (outside targeted region/low

VAF), conflicting results and TSO500-detected only results. |

Table II

Deconvolution of variants among

actionable genes and TP53 with concordant (original report

and manual inspection) and discordant (outside targeted region/low

VAF), conflicting results and TSO500-detected only results.

| | AKT1

(n=3) | BRCA1

(n=17) | BRCA2

(n=35) | ERBB2

(n=29) | ERBB3

(n=11) | ESR1

(n=1) | NTKR1

(n=17) | NTRK3

(n=7) | PALB2

(n=12) | PIK3CA

(n=37) | PTEN

(n=11) | TP53

(n=94) |

|---|

| Original

report | 100 | 18 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 78 | 36 | 52 |

| Enhanced with

manual inspection | 100 | 29 | 17 | 69 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 78 | 55 | 71 |

| Outside targeted

region/low VAF | 0 | 6 | 0 | 17 | 100 | 100 | 76 | 71 | 17 | 11 | 18 | 5 |

| Conflicting

result | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| TSO500-detected

only | 0 | 65 | 83 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 29 | 75 | 5 | 27 | 20 |

Discussion

To achieve the goal of personalized and precision

medicine, CGP has been recognized as a key tool that can

potentially transform cancer risk prediction, detection, diagnosis,

treatment and monitoring. CGP can augment clinical decision-making

in the form of either in vitro diagnostics (IVD) or

companion diagnostics. Most importantly, the continuous price

reduction across small- to large-sized CGP panels has improved

patient access (35). Consequently,

therapy assignments for newly diagnosed breast cancers and

monitoring of patients who are in treatment are expected to benefit

from CGP.

In the context of CGP, actionable genes refer to

specific genetic alterations or mutations in a patient's (tumor)

DNA that can guide therapeutic decisions or clinical interventions.

These genetic changes are considered ‘actionable’ because they

suggest potential treatments or clinical strategies that can

directly impact the patient's care. This may include targeting

specific mutations with precision medicine therapies, selecting

clinical trials based on the genomic profile, such as basket or

umbrella trials, or monitoring the patient for disease progression.

Actionable genes typically include those that are associated with

known therapies (such as targeted therapies and immunotherapies,

including PARP inhibition for pathogenic BRCA1/2 mutations),

have established clinical guidelines for intervention based on

their presence, or may offer prognostic or predictive value for

disease outcomes, guiding treatment options (1-5).

In the present study, the performance of medium- to large-sized

gene panels in a TNBC patient cohort was compared. Both OCP and

TSO500 are used worldwide, but there are few direct comparison

studies for breast cancer actionable genes in the literature

(18,19,36,37).

The four HER2-positive breast cancer cases provided

an opportunity to evaluate the association between clinical

HER2-status and NGS-based ERBB2 CNVs. None of these cases

were reported as HER2-amplified by OCP while two of three

HER2-amplified cases reported by TSO500 coincided with the four

clinically HER2-positive breast cancers. A higher number of

HER2-gained breast cancers were identified by TSO500, indicating

the potential for anti-HER2 targeting therapy. As NTRK

translocation was not listed as the targeted alteration of OCP, the

detectability of structure variants (CNV and fusion) was not

compared further.

In the present study, the genes and variants

reported from either OCP v3 or TSO500 when genomic, cDNA and

protein coordinates were used for variant sorting were detailed.

This subset represented the most actionable variants revealed by

medium- and large-sized CGP. AKT1 is an intra-cellular

kinase and is predominantly altered in breast and endometrial

cancer. The AKT1 E17K is the most common alteration across

various tumor types, including breast and gynecological cancers

(38,39). The CAPItello-291 phase III trial

demonstrated that capivasertib (AZD5363) and fulvestrant

combination therapy resulted in markedly longer progression-free

survival compared with the placebo and fulvestrant groups (40). The three AKT1 E17K-mutant

cases in the present study were identified by both panels.

There were two BRCA1 (S405* and R1203*) and

one BRCA2 (S521*) truncating mutations, and reflex germline

testing should precede if PARP inhibitor was considered for these

patients, as only germline BRCA1/2 mutations are actionable

in breast cancer (41). The

BRCA1 c.5470-1G>A SNP has been recognized as pathogenic

by both the Breast Cancer Information Core and Consortium of

Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 (42,43).

The BRCA2 S521* truncating mutation impairs nuclear

localization of BRCA2, which is essential for normal BRCA2 function

(44). Despite common truncating

and frameshift mutations (five for BRCA1 and three for

BRCA2) called by both panels, only TSO500 revealed more

suspicious variants (eight variants among 9 cases for BRCA1

and 13 variants among 21 subjects), while OCP was flawed by

spurious mutations (BRCA1: S1180fs and T1376fs; and

BRCA2: S538fs, T598fs, S973fs, E33*, T912fs, S3041fs and

S3147fs).

PALB2 K353fs is a truncating mutation in a

tumor suppressor gene and therefore is likely oncogenic. The phase

II TBCRC 048 study also indicated the predictive power of the

germline PALB2 mutation for metastatic breast cancer, as a

high response rate (82%) was observed when olaparib, a PARP

inhibitor, was used (45). In the

present study, TSO500 identified three additional variants in 5

cases while OCP reported 1 false positive case with up to four

variants (D1125fs, N368fs, S357fs and N342fs). Tumor-only

sequencing made differentiating germline from somatic

BRCA1/2 and PALB2 mutations challenging. However,

LOH-germline inference calculator and the somatic-germline-zygosity

algorithms helped distinguish these mutations, with one somatic and

eight germline BRCA1/2 mutations identified (46).

One patient harbored two mutations in ERBB2

(L811V and L839R) and another with the L725S mutation was

recognized by both platforms, none of which were among the

oncogenic mutations approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration

for the use of neratinib, a pan-HER kinase inhibitor that binds

irreversibly to the ATP-kinase domain of HER2 inhibiting the

downstream phosphorylation of AKT and MAPK (47). TSO500 identified three additional

ERBB2 mutations (P1140A, V743_M744insHV and Y742_A745dup).

It is important to note that TSO500 detected more complex mutations

(such as Y742_A745dup and V743_M744insHV, both classified as VUS)

than did OCP.

Certain PIK3CA hotspot mutations have been

identified from the SOLAR-1 trial for the usage of alpelisib, a

selective PI3K-α inhibitor, namely C420R, E542K, E545A, E545D,

E545G, E545K, Q546E, Q546R, H1047L, H1047R and H1047Y (48). Our previous study also observed

double mutations of PIK3CA among the Taiwanese population

(21). Only four cases with E726K,

G1049R, N345I and Q546R mutations were outside the hotspot region,

while two cases with D350N or D725N were co-mutant with other

hotspots, which were only reported by TSO500. Consequently, both

platforms identified the same number of PIK3CA-altered

breast cancer cases.

Conversely, selective PI3K-β inhibitors, GSK2636771

and AZD8186, are ATP competitors and have shown preclinical

antitumor response and durability for PTEN-deficient solid

tumors including TNBC (49). The

PTEN c.1026+1G>A SNP has been reported as clinically

pathogenic at least twice (Invitae Clinical Genomics Group and

ClinGen PTEN Variant Curation Expert Panel), with germline origin

(50,51). The remaining five consensual

variants (E150*, E43fs, P38fs, R130* and Q245*) were truncating

mutations; TSO500 identified two additional cases with PTEN

mutations (G127_G129del and V290Sfs*8) and OCP called one

inappropriate variant due to misalignment (c.386G>A).

Quite a few TP53 alterations were identified

by both OCP and TSO500. Despite not being currently druggable,

TP53 may act as an independent prognostic factor for early

and advanced-stage cancer with a wide range of mutational frequency

(52). It has been argued that all

TP53 mutations from tumor-only sequencing are somatic, and

rarely representative of the germline Li-Fraumeni syndrome

(53). TSO500 identified more

variants than OCP did, while the latter reported three cases with

V73fs in homopolymer region and one case with misaligned V73fs

mutation, both of which were spurious.

A total of 272 variants were identified among

actionable genes and TP53 from at least one panel.

Interestingly, the concordance rate from original reports was low

at slightly more than one-third (34.6%). With extensive

bioinformatics analyses and manual curation, three-fifths of

concordance (58.9%) were achieved after exclusion of unfiltered

polymorphisms, low-VAF variants and those beyond the targeted scope

of OCP. Among inconsistent variants, some were identical after

manual inspections, further indicating the necessity of analytical

abilities and domain knowledge in genomic nomenclature (54). Furthermore, an additional 62

variants were revealed by TSO500, indicating missed opportunities

by OCP, which may be explained by fundamental discrepancies in

sequencing technology. The accuracy of the amplicon-based OCP vs.

the hybrid capture-based TSO500 panel can be influenced by their

underlying methodologies. Amplicon-based methods utilize PCR

amplification with sequence-specific primers to enrich target

regions. By contrast, hybrid capture sequencing employs

hybridization-based capture to enrich for desired genomic regions.

Hybrid capture may offer a more robust and accurate approach,

especially for clinical applications (55).

In the context of TNBC research, a VAF cut-off of

#x003C;10% is used to filter out low-confidence or likely spurious

SNVs identified through NGS of tumor samples (56,57).

The threshold may be beneficial to eliminate technical, background

noise and subclonal mutations, as tumor samples can be contaminated

with normal cells, and low-level DNA damage or degradation can

introduce background noise that interferes with accurate SNV

calling. In addition, tumors are often composed of multiple

subclones with distinct genetic profiles. SNVs present in minor

subclones may have VAFs #x003C;10%, making them difficult to

distinguish from background noise (58). A VAF cut-off of 5-10% is commonly

used in various cancer genomics studies, including those focused on

TNBC. This range is considered to achieve a reasonable balance

between sensitivity (detecting true SNVs) and specificity

(excluding false positives) (59).

Despite being one of the pioneers to directly

compare two commercialized targeted panels, there were some

limitations to the present study. First, sequencing was not

conducted concurrently, and the 1-2 year delay of the TSO500

analysis following OCP may have introduced some bias from nucleic

acid degradation, despite all samples being stored under

temperature-controlled conditions. Second, variants called by each

panel were considered based on the standard or formal algorithm of

each platform (Ion Reporter/Oncomine Knowledgebase Reporter for OCP

and PierianDx for TSO500), which limited the comparability between

distinct platforms. For unbiased comparison, the same aligner,

caller and annotator should be applied. However, browser extensible

data files were unavailable from manufacturers to confirm the

jointly interrogated regions. On the other hand, all commercial CGP

solutions are under regulation as either laboratory developed tests

or IVD, and practically these pre-set algorithms should not be

modified arbitrarily to enhance reproducibility. Despite this, the

present study conducted an exhaustive bioinformatic analysis from

BAM files to dissect the conflicting results from the same samples.

Third, NTRK is not within the targeted fusion genes of OCP;

therefore, a comparison with TSO500 was not possible. Moreover,

NTRK sequence variants, amplifications or fusions are not

actionable for breast cancer. As larotrectinib and entrectinib are

approved in a number of countries, NTRK fusion as a

tumor-agnostic marker is important, and its detection should be

incorporated into CGP for breast cancer (60). Fourth, as most cases are triple

negative phenotypically, a cohort of ~100 patients with TNBC is

suitable for a comparative sequencing panel study. However, if the

goal is to perform more detailed subgroup analyses or identify rare

mutations, a larger cohort may be more appropriate. In the future,

conducting a prospective and parallel study across distinct CGP

platforms could reveal whether larger sequencing panels justify

their higher costs by improving the detection of actionable

mutations, refining novel therapeutic strategies, and

characterizing the complex genomic landscape of TNBC. Furthermore,

it would provide critical insights to optimize genomic profiling

for other breast cancer subtypes, advancing both research and

clinical care.

As an observational study, the present study could

not directly assess the impact of CGP on treatment outcomes, as no

intervention was performed. During the study period, the

compassionate use of alpelisib (a selective PI3K inhibitor)

benefited nine patients, and the out-of-pocket use of olaparib (a

PARP inhibitor) benefited two patients, demonstrating the

actionability of the testing. Since May 2024, NGS, specifically

whole-exome sequencing for BRCA1/2, has been reimbursed in

Taiwan for patients with stage II or higher TNBC. The Regulations

of Special Medical Techniques of Taiwan require that all NGS

testing results (including both whole-exome sequencing and targeted

panels) be submitted to the National Health Research Institutes

Biobank. It is anticipated that cost-effective implementation of

larger NGS panels in routine clinical practice will be possible in

the future, once sufficient data from NGS results and accompanying

clinical outcomes are available.

In conclusion, the present study comparing medium-

and large-sized sequencing panels in a cohort of patients with TNBC

may provide critical insights into the balance between actionable

gene findings, cost and complexity. TSO500, the larger panel,

detected more variants than OCP did, even from the same set of

ESCAT-defined actionable genes and TP53. Conversely, a

proportion of inconsistent variants could be manually curated and

were identical with aliasing coordinates or starting positions.

Finally, there were variants detectable only by TSO500, indicating

potential and fundamental differences in sequencing technology,

bioinformatic algorithms and variant filtering. The value of a

large-sized panel in clinical usage is ascertained, considering the

beneficiaries of PARP inhibition for the higher number of

BRCA1/2 and PALB2 mutations detected, as indicated by

the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and ESMO guidelines

(61,62). Given the experience from the present

study, the updated Oncomine Comprehensive Assay Plus with >500

genes profiled is anticipated in future studies (63). The results could guide panel

selection for precision oncology, ensuring optimal clinical

outcomes while maximizing resource efficiency. This approach would

be particularly impactful in refining strategies for TNBC

management.

Supplementary Material

Examples of discordant variants

between TSO500 and OCP visualized through integrative genomic

viewer. The upper half of each panel represents aligned reads of

TSO500, and the lower half represents aligned reads of OCP. (A)

Variants beyond the OCP targeted regions. There was a ERBB3

c.1463G>A (p.R488Q) variant detected by TSO500. In OCP, no read

was present in this region and therefore no variant was reported by

OCP. (B) Variants in homopolymer region. There was a PTEN

c.V290Sfs*8 (p.867dupA) variant clearly observed in the aligned

reads of TSO500 and OCP. TSO500 accurately reported this variant,

whereas OCP missed this variant and therefore did not report it.

(C) Likely artifactual variants in homopolymer region. In the

aligned reads of OCP, some reads showed an insertion of a single A

nucleotide, and some showed an insertion of double A nucleotides.

Due to these alterations, OCP reported that there was a BRCA2

c.2916_2917insA (p.S973fs) variant in this region. However, in the

aligned reads of TSO500, no variant can be observed. As false

indels in homopolymer repeats are a well-known weakness of the Ion

Torrent sequencing platform, which is used in OCP, BRCA2

c.2916_2917insA (p.S973fs) is likely to be an artifactual variant

in homopolymer region introduced by errors of sequencing. (D)

Inappropriately annotated variant due to misalignment. In the

aligned reads of TSO500, a three-nucleotide deletion of TP53

c.419_421delCCT (p.T140_C141delinsS) can be clearly observed. The

alignment of OCP in this region is more disorganized. Although the

three-nucleotide deletion of c.419_421delCCT still can be seen, OCP

erroneously reported this variant as TP53 c.421T>A (p.C141S).

TSO500, TruSight Oncology 500; OCP, Oncomine Comprehensive Assay

Panel v3.

Summary of actionable mutations among

108 Taiwanese patients with breast cancer assayed with the TruSight

Oncology 500.

Summary of actionable mutations among

108 Taiwanese patients with breast cancer assayed with the Oncomine

Comprehensive Assay Plus v3.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Morris Chang

(retired from the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) for

professional consultation about the technical feasibility of the

present study. The authors also appreciate the kind support with

NGS experiments from the Illumina team (Illumina, Inc.; San Diego,

CA), including Dr Mark M. Wang, Dr Vincent Hsieh, Mr. Thomas Tang,

Mrs. Jora Lin, Mr. Dr Wang and Mr. Jerry Cheng throughout the

execution of this study.

Funding

Funding: This work was supported in part by Taipei Veterans

General Hospital research fund grant nos. V110E-005-3, V111E-006-3,

V112E-004-3 and V112C-013, Melissa Lee Cancer Foundation (grant no.

MLCF_V114_B11404) and National Science and Technology Council

(grant no. NSTC 111-2314-B-075-063-MY3).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

found in the Sequence Read Archive database under accession number

PRJNA1256731 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA1256731.

Authors' contributions

CCH and LMT conceived the study. CCH drafted the

manuscript. YCY conducted bioinformatics analyses. YFT, YSL, TCC

and CYL collected samples and certified the NGS reports. HLH

conducted NGS experiments. CCH and YCY confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. LMT approved the final submission. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the

Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital

(approval nos. 2021-01-007B and 2023-08-002B; Taipei, Taiwan).

Participants provided written informed consent for both the

prospective/retrospective VGH-TAYLOR study (approval no.

2021-01-007B) and for the retrospective re-sequencing study

(approval no. 2023-08-002B).

Patient consent for publication

All participants agreed to the publication of the

present study, with all identifying information removed.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Huang CC, Yeh YC, Ho HL, Liu CY, Tsai YF

and Tseng LM: Comprehensive genomic profiling of Taiwanese patients

with breast cancer using a novel targeted panel: Preliminary

analyses from a prospective triple-negative cohort. J Clin Oncol.

41 (Suppl 16)(e12553)2023.

|

|

2

|

Wang L, Zhai Q, Lu Q, Lee K, Zheng Q, Hong

R and Wang S: Clinical genomic profiling to identify actionable

alterations for very early relapsed triple-negative breast cancer

patients in the Chinese population. Ann Med. 53:1358–1369.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Tierno D, Grassi G, Scomersi S, Bortul M,

Generali D, Zanconati F and Scaggiante B: Next-generation

sequencing and triple-negative breast cancer: Insights and

applications. Int J Mol Sci. 24(9688)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

O'Haire S, Degeling K, Franchini F, Tran

B, Luen SJ, Gaff C, Smith K, Fox S, Desai J and IJzerman M:

Comparing survival outcomes for advanced cancer patients who

received complex genomic profiling using a synthetic control arm.

Target Oncol. 17:539–548. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Cifuentes C, Lombana M, Vargas H, Laguado

P, Ruiz-Patiño A, Rojas L, Navarro U, Vargas C, Ricaurte L, Arrieta

O, et al: Application of comprehensive genomic profiling-based

next-generation sequencing assay to improve cancer care in a

developing country. Cancer Control.

30(10732748231175256)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Almansour NM: Triple-negative breast

cancer: A brief review about epidemiology, risk factors, signaling

pathways, treatment and role of artificial intelligence. Front Mol

Biosci. 9(836417)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM,

Kahn HK, Sawka CA, Lickley LA, Rawlinson E, Sun P and Narod SA:

Triple-negative breast cancer: Clinical features and patterns of

recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 13:4429–4434. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Foulkes WD, Smith IE and Reis-Filho JS:

Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 363:1938–1948.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Stewart RL, Updike KL, Factor RE, Henry

NL, Boucher KM, Bernard PS and Varley KE: A multigene assay

determines risk of recurrence in patients with triple-negative

breast cancer. Cancer Res. 79:3466–3478. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Jie H, Ma W and Huang C: Diagnosis,

prognosis, and treatment of triple-negative breast cancer: A

review. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 17:265–274. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Mateo J, Chakravarty D, Dienstmann R,

Jezdic S, Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N, Ng CKY, Bedard PL,

Tortora G, Douillard JY, et al: A framework to rank genomic

alterations as targets for cancer precision medicine: The ESMO

scale for clinical actionability of molecular targets (ESCAT). Ann

Oncol. 29:1895–1902. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Condorelli R, Mosele F, Verret B, Bachelot

T, Bedard PL, Cortes J, Hyman DM, Juric D, Krop I, Bieche I, et al:

Genomic alterations in breast cancer: Level of evidence for

actionability according to ESMO scale for clinical actionability of

molecular targets (ESCAT). Ann Oncol. 30:365–373. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Bianchini G, Balko JM, Mayer IA, Sanders

ME and Gianni L: Triple-negative breast cancer: Challenges and

opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

13:674–690. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Masci D, Naro C, Puxeddu M, Urbani A,

Sette C, La Regina G and Silvestri R: Recent advances in drug

discovery for triple-negative breast cancer treatment. Molecules.

28(7513)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Baden J, Zhao C, Pratt J, Kirov S, Pant A,

Seminara A, Green G, Bilke S, Deras I, Fabrizio DA and Pawlowski T:

90PD-Comparison of platforms for determining tumour mutational

burden (TMB) in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Ann Oncol. 30 (Suppl 5)(v25)2019.

|

|

16

|

Wei B, Kang J, Kibukawa M, Arreaza G,

Maguire M, Chen L, Qiu P, Lang L, Aurora-Garg D, Cristescu R and

Levitan D: Evaluation of the TruSight oncology 500 assay for

routine clinical testing of tumor mutational burden and clinical

utility for predicting response to pembrolizumab. J Mol Diagn.

24:600–608. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Liu CY, Huang CC, Tsai YF, Chao TC, Lien

PJ, Lin YS, Feng CJ, Chen JL, Chen YJ, Chiu JH, et al: VGH-TAYLOR:

Comprehensive precision medicine study protocol on the

heterogeneity of Taiwanese breast cancer patients. Future Oncol:

Oct 19, 2021 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

18

|

Huang CC, Tsai YF, Liu CY, Chao TC, Lien

PJ, Lin YS, Feng CJ, Chiu JH, Hsu CY and Tseng LM: Comprehensive

molecular profiling of Taiwanese breast cancers revealed potential

therapeutic targets: prevalence of actionable mutations among 380

targeted sequencing analyses. BMC Cancer. 21(199)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Huang CC, Tsai YF, Liu CY, Lien PJ, Lin

YS, Chao TC, Feng CJ, Chen YJ, Lai JI, Phan NN, et al: Prevalence

of tumor genomic alterations in homologous recombination repair

genes among taiwanese breast cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 29:3578–3590.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Huang CC, Tsai YF, Liu CY, Lien PJ, Lin

YS, Chao TC, Feng CJ, Chen YJ, Lai JI, Cheng HF, et al: Concordance

of targeted sequencing from circulating tumor DNA and paired tumor

tissue for early breast cancer. Cancers (Basel).

15(4475)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chao TC, Tsai YF, Liu CY, Lien PJ, Lin YS,

Feng CJ, Chen YJ, Lai JI, Hsu CY, Lynn JJ, et al: Prevalence of

PIK3CA mutations in Taiwanese patients with breast cancer: A

retrospective next-generation sequencing database analysis. Front

Oncol. 13(1192946)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J,

Abramson V, Aft R, Agnese D, Allison KH, Anderson B, Burstein HJ,

Chew H, et al: NCCN guidelines® insights: Breast cancer,

version 4.2023. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 21:594–608. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Gennari A, André F, Barrios CH, Cortés J,

de Azambuja E, DeMichele A, Dent R, Fenlon D, Gligorov J, Hurvitz

SA, et al: ESMO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis,

staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer.

Ann Oncol. 32:1475–1495. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

No authors listed. Pathologists' guideline

recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and

progesterone receptors in breast cancer. Breast Care (Basel).

5:185–187. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Wolff AC, Somerfield MR, Dowsett M,

Hammond MEH, Hayes DF, McShane LM, Saphner TJ, Spears PA and

Allison KH: Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in

breast cancer: ASCO-college of american pathologists guideline

update. J Clin Oncol. 41:3867–3872. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Schirmer M, Ijaz UZ, D'Amore R, Hall N,

Sloan WT and Quince C: Insight into biases and sequencing errors

for amplicon sequencing with the Illumina MiSeq platform. Nucleic

Acids Res. 43(e37)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Li MM, Datto M, Duncavage EJ, Kulkarni S,

Lindeman NI, Roy S, Tsimberidou AM, Vnencak-Jones CL, Wolff DJ,

Younes A and Nikiforova MN: Standards and guidelines for the

interpretation and reporting of sequence variants in cancer: A

joint consensus recommendation of the association for molecular

pathology, American society of clinical oncology, and college of

American pathologists. J Mol Diagn. 19:4–23. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G,

Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, et al:

Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical

profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 6(pl1)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE,

Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, et

al: The cBio cancer genomics portal: An open platform for exploring

multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2:401–404.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips SM, Kundra

R, Zhang H, Wang J, Rudolph JE, Yaeger R, Soumerai T, Nissan MH, et

al: OncoKB: A precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis Oncol.

2017(PO.17.00011)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Phan L, Zhang H, Wang Q, Villamarin R,

Hefferon T, Ramanathan A and Kattman B: The evolution of dbSNP: 25

Years of impact in genomic research. Nucleic Acids Res.

53:D925–D931. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Chen S, Francioli LC, Goodrich JK, Collins

RL, Kanai M, Wang Q, Alföldi J, Watts NA, Vittal C, Gauthier LD, et

al: A genomic mutational constraint map using variation in 76,156

human genomes. Nature. 625:92–100. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Karczewski KJ, Weisburd B, Thomas B,

Solomonson M, Ruderfer DM, Kavanagh D, Hamamsy T, Lek M, Samocha

KE, Cummings BB, et al: The ExAC browser: Displaying reference data

information from over 60 000 exomes. Nucleic Acids Res.

45:D840–D845. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Turner D

and Mesirov JP: igv.js: An embeddable JavaScript implementation of

the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV). Bioinformatics.

39(btac830)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Wolff L and Kiesewetter B: Applicability

of ESMO-MCBS and ESCAT for molecular tumor boards. Memo.

15:190–195. 2022.

|

|

36

|

Huang CC, Yeh YC, Cheng HF, Chen BF, Liu

CY, Tsai YF, Ho HL and Tseng LM: Comprehensive genomic profiling of

Taiwanese triple-negative breast cancer with a large targeted

sequencing panel. J Chin Med Assoc: Jun 20, 2025 (Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

37

|

Loderer D, Hornáková A, Tobiášová K,

Lešková K, Halašová E, Danková Z, Biringer K, Kúdela E, Rokos T,

Dzian A, et al: Comparison of next-generation sequencing quality

metrics and concordance in the detection of cancer-specific

molecular alterations between formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded and

fresh-frozen samples in comprehensive genomic profiling with the

Illumina® TruSight oncology 500 assay. Exp Ther Med.

29(64)2025.

|

|

38

|

Carpten JD, Faber AL, Horn C, Donoho GP,

Briggs SL, Robbins CM, Hostetter G, Boguslawski S, Moses TY, Savage

S, et al: A transforming mutation in the pleckstrin homology domain

of AKT1 in cancer. Nature. 448:439–444. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Kalinsky K, Hong F, McCourt CK, Sachdev

JC, Mitchell EP, Zwiebel JA, Doyle LA, McShane LM, Li S, Gray RJ,

et al: Effect of capivasertib in patients with an AKT1 E17K-mutated

tumor: NCI-MATCH subprotocol EAY131-Y nonrandomized trial. JAMA

Oncol. 7:271–278. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Turner NC, Oliveira M, Howell SJ, Dalenc

F, Cortes J, Gomez Moreno HL, Hu X, Jhaveri K, Krivorotko P, Loibl

S, et al: Capivasertib in hormone receptor-positive advanced breast

cancer. N Engl J Med. 388:2058–2070. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Daly GR, AlRawashdeh MM, McGrath J,

Dowling GP, Cox L, Naidoo S, Vareslija D, Hill ADK and Young L:

PARP inhibitors in breast cancer: A short communication. Curr Oncol

Rep. 26:103–113. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Szabo C, Masiello A, Ryan JF and Brody LC:

The breast cancer information core: Database design, structure, and

scope. Hum Mutat. 16:123–131. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Chenevix-Trench G, Milne RL, Antoniou AC,

Couch FJ, Easton DF and Goldgar DE: CIMBA. An international

initiative to identify genetic modifiers of cancer risk in BRCA1

and BRCA2 mutation carriers: The consortium of investigators of

modifiers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 (CIMBA). Breast Cancer Res.

9(104)2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Spain BH, Larson CJ, Shihabuddin LS, Gage

FH and Verma IM: Truncated BRCA2 is cytoplasmic: Implications for

cancer-linked mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 96:13920–13925.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Tung NM, Robson ME, Ventz S, Santa-Maria

CA, Nanda R, Marcom PK, Shah PD, Ballinger TJ, Yang ES, Vinayak S,

et al: TBCRC 048: Phase II study of olaparib for metastatic breast

cancer and mutations in homologous recombination-related genes. J

Clin Oncol. 38:4274–4282. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Cheng HF, Tsai YF, Liu CY, Hsu CY, Lien

PJ, Lin YS, Chao TC, Lai JI, Feng CJ, Chen YJ, et al: Prevalence of

BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2 genomic alterations among 924 Taiwanese

breast cancer assays with tumor-only targeted sequencing: Extended

data analysis from the VGH-TAYLOR study. Breast Cancer Res.

25(152)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Hyman DM, Piha-Paul SA, Won H, Rodon J,

Saura C, Shapiro GI, Juric D, Quinn DI, Moreno V, Doger B, et al:

HER kinase inhibition in patients with HER2- and HER3-mutant

cancers. Nature. 554:189–194. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

André F, Ciruelos EM, Juric D, Loibl S,

Campone M, Mayer IA, Rubovszky G, Yamashita T, Kaufman B, Lu YS, et

al: Alpelisib plus fulvestrant for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone

receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor

receptor-2-negative advanced breast cancer: Final overall survival

results from SOLAR-1. Ann Oncol. 32:208–217. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Choudhury AD, Higano CS, de Bono JS, Cook

N, Rathkopf DE, Wisinski KB, Martin-Liberal J, Linch M, Heath EI,

Baird RD, et al: A phase I study investigating AZD8186, a potent

and selective inhibitor of PI3Kβ/δ, in patients with advanced solid

tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 28:2257–2269. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Chen HJ, Romigh T, Sesock K and Eng C:

Characterization of cryptic splicing in germline PTEN intronic

variants in Cowden syndrome. Hum Mutat. 38:1372–1377.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Mester JL, Ghosh R, Pesaran T, Huether R,

Karam R, Hruska KS, Costa HA, Lachlan K, Ngeow J, Barnholtz-Sloan

J, et al: Gene-specific criteria for PTEN variant curation:

Recommendations from the ClinGen PTEN expert panel. Hum Mutat.

39:1581–1592. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Nykamp K, Anderson M, Powers M, Garcia J,

Herrera B, Ho YY, Kobayashi Y, Patil N, Thusberg J, Westbrook M, et

al: Sherloc: A comprehensive refinement of the ACMG-AMP variant

classification criteria. Genet Med. 19:1105–1117. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Garrido-Navas MC, García-Díaz A,

Molina-Vallejo MP, González-Martínez C, Alcaide Lucena M,

Cañas-García I, Bayarri C, Delgado JR, González E, Lorente JA and

Serrano MJ: The polemic diagnostic role of TP53 mutations in liquid

biopsies from breast, colon and lung cancers. Cancers (Basel).

12(3343)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Zhou W, Chen T, Chong Z, Rohrdanz MA,

Melott JM, Wakefield C, Zeng J, Weinstein JN, Meric-Bernstam F,

Mills GB and Chen K: TransVar: A multilevel variant annotator for

precision genomics. Nat Methods. 12:1002–1003. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Mosteiro M, Azuara D, Villatoro S, Alay A,

Gausachs M, Varela M, Baixeras N, Pijuan L, Ajenjo-Bauza M,

Lopez-Doriga A, et al: Molecular profiling and feasibility using a

comprehensive hybrid capture panel on a consecutive series of

non-small-cell lung cancer patients from a single centre. ESMO

Open. 8(102197)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Fox EJ, Reid-Bayliss KS, Emond MJ and Loeb

LA: Accuracy of Next generation sequencing platforms. Next Gener

Seq Appl. 1(1000106)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Song P, Chen SX, Yan YH, Pinto A, Cheng

LY, Dai P, Patel AA and Zhang DY: Selective multiplexed enrichment

for the detection and quantitation of low-fraction DNA variants via

low-depth sequencing. Nat Biomed Eng. 5:690–701. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Apostoli AJ and Ailles L: Clonal evolution

and tumor-initiating cells: New dimensions in cancer patient

treatment. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 53:40–51. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Edsjö A, Gisselsson D, Staaf J, Holmquist

L, Fioretos T, Cavelier L and Rosenquist R: Current and emerging

sequencing-based tools for precision cancer medicine. Mol Aspects

Med. 96(101250)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Cocco E, Scaltriti M and Drilon A: NTRK

fusion-positive cancers and TRK inhibitor therapy. Nat Rev Clin

Oncol. 15:731–747. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Mosele MF, Westphalen CB, Stenzinger A,

Barlesi F, Bayle A, Bièche I, Bonastre J, Castro E, Dienstmann R,

Krämer A, et al: Recommendations for the use of next-generation

sequencing (NGS) for patients with advanced cancer in 2024: A

report from the ESMO precision medicine working group. Ann Oncol.

35:588–606. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J,

Abramson V, Aft R, Agnese D, Allison KH, Anderson B, Bailey J,

Burstein HJ, et al: Breast cancer, version 3.2024, NCCN clinical

practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

22:331–357. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Kang J, Na K, Kang H, Cho U, Kwon SY,

Hwang S and Lee A: Prediction of homologous recombination

deficiency from oncomine comprehensive assay plus correlating with

SOPHiA DDM HRD solution. PLoS One. 19(e0298128)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|