Introduction

The diagnosis of central nervous system (CNS)

tumours has evolved significantly over the past decade, moving

beyond traditional clinical and histopathological assessments to an

integrated, multi-dimensional approach that incorporates molecular

diagnostics (1). The 2021 WHO

classification of CNS tumours introduced a paradigm shift by

emphasizing the need for a molecularly informed diagnosis that

combines histopathological findings with specific genetic,

epigenetic, and protein expression profiles (2,3). This

integrated diagnosis framework allows for more accurate tumour

classification, as numerous CNS tumours exhibit overlapping

histological features but distinct molecular signatures that

directly impact prognosis and therapeutic decisions.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) remains a cornerstone for

initial tumour characterization, providing insights into cellular

lineage and differentiation. However, it often falls short in cases

with ambiguous morphology or treatment-induced changes.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, such as targeted

gene panels, whole-exome sequencing, and methylation profiling, are

increasingly essential to identify diagnostic, prognostic, and

therapeutic markers. For example, the detection of specific

mutations (such as IDH1/2 in gliomas, BRAF V600E in gangliogliomas

or pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas), chromosomal alterations (such

as 1p/19q co-deletion in oligodendrogliomas), or methylation

patterns [such as O6-methylguanine-DNA

methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation or genome-wide

methylation classifiers] is now pivotal in classifying CNS tumours

(2). This molecular classification

not only refines diagnostic accuracy but also provides critical

information on tumour behaviour, treatment response, and patient

outcomes, underscoring the necessity for a comprehensive,

integrated diagnostic approach in modern neuropathology (4).

The accurate diagnosis of CNS tumours is the most

challenging for cases that have been previously treated. Tumours

subjected to pre-treatment modalities such as radiation or

chemotherapy frequently undergo morphological and molecular changes

that can obscure their histopathological features. This phenomenon,

known as treatment-related distortion, complicates subsequent

diagnostic efforts, making it difficult to discern between tumour

recurrence, radiation-induced changes, or an entirely new entity

(5). For instance, gliomas, such as

high-grade gliomas, often exhibit post-radiation changes including

nuclear and cytoplasmic enlargement, which may also mimic

pseudo-malignant radiation-associated changes (6). Similarly, meningiomas post-irradiation

may exhibit increased cellular atypia, loss of classic whorl

patterns, and elevated Ki-67 indices reflecting either

radiation-induced proliferation or cell death (7). These changes can mimic features of

higher-grade malignancies, leading to diagnostic uncertainty when

relying solely on histopathology and IHC.

Post-treatment CNS tumours, especially those

subjected to high-dose radiation, pose a significant diagnostic

dilemma due to treatment-related changes. Recurrent CNS tumours

exhibit histopathological features altered by prior therapies,

complicating differentiation between tumour recurrence,

treatment-induced necrosis, or secondary malignancies (8-10)

For instance, a 2023 study by Wood et al (5) highlighted that paediatric high-grade

astrocytoma post-treatment showed increased tumour mutation burden

and morphological ambiguity in a subset of recurrences,

underscoring the prevalence of diagnostic challenges (5). Similarly, radiation-induced changes,

such as fibrosis, vascular alterations, and cellular atypia, can

mimic aggressive tumour features, leading to misclassification

rates as high as 20% when relying solely on histopathology and IHC

(11). IHC, while valuable for

initial tumour characterization, often yields inconclusive or

conflicting results in these cases due to altered protein

expression profiles induced by therapy.

Recent advances in epigenomic profiling, such as

whole genome methylation profiling, have emerged as potent tools

for resolving such diagnostic dilemmas (12,13).

Unlike protein expression or histopathological features, which are

highly susceptible to treatment-induced alterations, DNA

methylation patterns exhibit high stability, even in the presence

of morphological distortions. This stability arises because DNA

methylation, an epigenetic modification, is regulated by DNA

methyltransferases and remains relatively unaffected by the

cellular stress or protein turnover induced by therapies such as

radiation, whereas downstream protein expression is disrupted by

changes in transcription, translation, or protein degradation

pathways (14). For example,

radiation may upregulate stress-response genes or silence tumour

suppressor genes via histone modifications, altering IHC-detectable

proteins such as p53 or mucin 1, cell surface associated (EMA),

while the underlying CpG methylation patterns at promoter regions

remain conserved (15). This

phenomenon has been reported in brain malignancies; a study on

recurrent glioblastomas demonstrated that methylation profiles of

MGMT were preserved despite chemoradiation (16). This was likely because promoter

methylation is relatively stable, and does not require active

maintenance of methylation status by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs)

(17).

Methylation profiling leverages this conserved

epigenetic signature to provide robust molecular classification,

offering a distinct advantage over existing methodologies.

Methylation profiling can provide a rigorous molecular

classification that remains largely unaffected by histopathological

distortions. In the present study, a case of a patient with a

heavily irradiated CNS tumour that exhibited perplexing

histological features, making definitive diagnosis difficult, is

reported. Despite extensive immunohistochemical analysis, the

tumour remained unclassifiable. To address this diagnostic impasse,

low-coverage whole genome methylation profiling, a technique that

has shown promise in accurately predicting the molecular subtype of

various cancers, even in the presence of histological ambiguity,

was employed.

Case report

Patient information

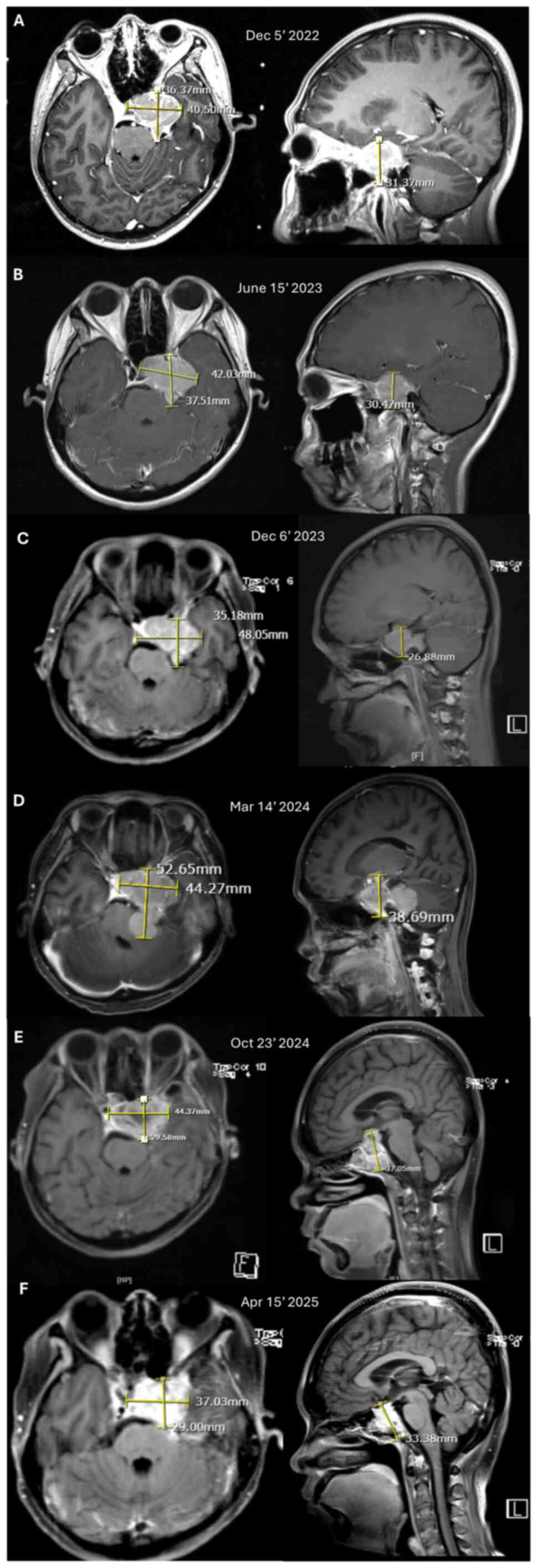

A clinical sample was obtained from a patient

48-year-old female who initially presented with a parasellar mass,

clinically resembling an extra-axial tumour. An initial MRI

performed in December 2022 revealed a 3.6x4.3x3.1 cm tumour in left

parasellar region, raising suspicion for meningioma or

craniopharyngioma (Fig. 1A). The

patient initially declined surgical intervention and was instead

treated with Gamma Knife stereotactic radiosurgery, receiving a

dose of 14 Gy in December 2022. Subsequent MRI follow-ups were

conducted every six months. The tumour remained stable in size for

up to one year post-radiation, as shown in MRI scans from June 2023

and December 2023 (Fig. 1B and

C, respectively). After ~1 year and

3 months post-radiation treatment, a brain MRI performed in March

2024 revealed a progressive tumour at the same location extending

to the left cerebellopontine angle and abutting the brainstem

(Fig. 1D). Surgery was offered and

the patient agreed. A subtotal resection was performed in March

2024; however the surgeon was unable to achieve gross total

resection due to the tumour encasing the cavernous sinus. At the

follow-up 6 months after the surgery, the patient did not exhibit

any significant symptoms, and an MRI scan performed in October

2024, revealed stable disease (Fig.

1E). An MRI was performed again 6 months later in April 2025

and revealed a slight reduction of tumour size (Fig. 1F). Since there was no progression of

disease, no further intervention was undertaken.

A tissue sample was obtained during craniotomy

performed in in March 2024 from the left retroclival region.

Histopathological analysis and further immunohistochemical

assessment performed in April 2024 were both inconclusive;

therefore, further molecular examination was performed. Ethical

clearance was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of

Medicine, University of Indonesia (Jakarta, Indonesia) in

accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, for the collection and

molecular testing of biological specimens from rare and recurrent

tumours at any site. Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient prior to molecular testing, ensuring full disclosure of the

purpose, procedures and potential use of biological specimens for

research in the present study. The specimen was retrieved from the

Department of Pathology of Cipto Mangunkusumo National General

Hospital (Jakarta, Indonesia) in the form of formalin-fixed

paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue. DNA extraction was performed on

the FFPE tissue sample, followed by NGS sequencing using a third

generation sequencing platform, and the methylation profile was

analysed. The DNA extraction and NGS were performed in August 2024.

The molecular information was then matched with available clinical,

imaging, histopathology and immunohistochemcial results.

Tissue processing and IHC

The tumour tissue sample was initially fixed in 10%

neutral buffered formalin for 24 at 4˚C to preserve cellular

structure and protein antigenicity, followed by dehydration and

embedding in paraffin wax. Once embedded, the tissue was sectioned

into thin slices with a thickness of 4-5 µm using a microtome, and

was then mounted onto positively charged glass slides to ensure

optimal adherence. The slides were baked at 60˚C to solidify tissue

attachment before further processing. The next step was

deparaffinization and rehydration. Tissue sections were

deparaffinized by immersing them in xylene, followed by rehydration

through a graded series of ethanol solutions of decreasing

concentrations (100, 95 and 70%) and finally in distilled water. To

expose the antigenic sites, antigen retrieval was performed using a

heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) technique in an EDTA buffer

(pH 9.0). This step resulted in unmasking the target epitopes and

enhancing antibody binding.

Following antigen retrieval, non-specific binding

was minimized by incubating the slides with a blocking solution,

10% bovine serum albumin (cat. no. 37520; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) for 30 min at room temperature. After blocking, primary

antibodies (Table I) specific to

each target protein marker were applied at their optimized

dilutions following each antibody kit manufacturer guideline. The

slides were then incubated in a humid chamber for 2 h at room

temperature. This step enabled the primary antibodies to bind

specifically to their corresponding antigens in the tissue

sections. The detection of bound primary antibodies was carried out

using an appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to a biotin

enzyme, horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (mouse anti-human IgG4 Fc,

secondary antibody, HRP; 1:1,000; cat. no. A-10654; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. A chromogenic

substrate, 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB), was used to develop a brown

colour, indicating the presence of the target antigen.

Counterstaining with hematoxylin was performed for 5 min at room

temperature to provide contrast by staining cell nuclei blue,

aiding in the morphological assessment of the tissue.

| Table IAntibodies for immunohistochemical

staining. |

Table I

Antibodies for immunohistochemical

staining.

| Immunohistochemical

marker | Supplier | Cat. no. | Dilution |

|---|

| Vimentin | Leica

Biosystems | PA0640 | RTU |

| AE1/3 | Leica

Biosystems | PA0909 | RTU |

| EMA | Leica

Biosystems | NCL-L-EMA | 1:400 |

| p63 | Biocare Medical,

LLC | CM163C | 1:50 |

| S100 | Biocare Medical,

LLC | ACR3237C | 1:200 |

| Synaptophysin | Biocare Medical,

LLC | CM371C | 1:200 |

| Chromogranin | Cell Marque; Merck

KGaA | 238M-96 | 1:500 |

| PR | Roche

Diagnostics | 5277990001 | RTU |

| CD34 | BioSB, Inc. | BSB5230 | 1:100 |

| Ki-67 | Roche

Diagnostics | 5278384001 | RTU |

| p40 | BioSB, Inc. | BSB2075 | 1:200 |

| CK7 | BioSB, Inc. | BSB5412 | 1:600 |

| CK8 | BioSB, Inc. | BSB6665 | 1:100 |

| CK19 | Biocare Medical,

LLC | CM242C | 1:100 |

| HMWCK | BioSB, Inc. | BSB5398 | 1:50 |

| Cam5.2 | Cell Marque; Merck

KGaA | 452M-96 | 1:100 |

| CK20 | Biocare Medical,

LLC | CM062C | 1:200 |

| ER | Roche

Diagnostics | 5278406001 | RTU |

| STAT6 | Biocare Medical,

LLC | ACI3244C | 1:100 |

| TTF-1 | Leica

Biosystems | PA0364 | RTU |

| BRAF V600E | BioSB, Inc. | BSB2824 | 1:250 |

| Beta catenin | Biocare Medical,

LLC | CM406C | 1:200 |

| TLE-1 | Cell Marque; Merck

KGaA | 401M-16 | 1:100 |

| BCL2 | Leica

Biosystems | PA0117 | RTU |

| CD99 | Cell Marque; Merck

KGaA | 199R-16 | 1:100 |

| CD56 | Leica

Biosystems | NCL-L-CD56-504 | 1:100 |

After staining, the slides underwent a series of

dehydration steps using graded alcohols, followed by clearing in

xylene, and were finally mounted with a permanent mounting medium.

The prepared slides were then examined under a light microscope by

a senior neuropathologist to evaluate the expression patterns of

the specific markers. The staining intensity and proportion of

positive cells were recorded for each marker. The

immunohistochemical markers examined were Vimentin, AE1/3, EMA,

p63, S100, PR, CD34, Ki-67, p40, CK7, CK8, HMWCK, Cam5.2, CK20, ER,

STAT6, TTF-1, BRAF V600E, β-catenin, TLE-1, BCL2, CD99, and

CD56.

DNA extraction

The DNA extraction of the FFPE tissue was carried

out using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (cat. no. 56404; QIAGEN)

which involved several key steps. Initially, the FFPE tissue sample

was deparaffinized using a xylene and ethanol wash to remove any

residual paraffin. Then the tissue was prepared for next process,

lysis. This lysis step involved breakdown of the cross-linked

proteins in the FFPE samples. The sample underwent incubation with

a lysis buffer and proteinase K (both included in the

aforementioned kit) to digest the tissue and release the DNA into

the solution.

Once lysis was completed, the sample was treated

with a heat incubation step up to 90˚C to reverse formalin-induced

crosslinking, which helped to ensure optimal DNA recovery and

purity. The lysate was then mixed with ethanol and passed through a

QIAamp MinElute column, which selectively bonded the DNA. Following

several washes to remove contaminants, the purified DNA was eluted

in a low-salt buffer, ready for downstream sequencing applications.

The authors adhered strictly to the manufacturer-recommended

protocol for extracting FFPE tissue. The complete and detailed

protocol was available publicly in the corresponding kit

documentation online. The extracted DNA was measured for purity

using Nanodrop Spectrophotometer and the quantity was measured

using Qubit Fluorometers (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.).

NGS sequencing

The extracted DNA was sequenced using a third

generation sequencer from (Oxford Nanopore Technologies plc). A

ligation-based protocol was used to prepare the library DNA

[Ligation sequencing DNA V14 (SQK-LSK114); Oxford Nanopore

Technologies plc]. There was no PCR step involved to preserve the

native methylation information within the DNA. The type of

sequencing was direct DNA sequencing with modified bases for

methylation detection. The DNA was sequenced using PromethION flow

cell (cat. no. FLO-PRO114M; Oxford Nanopore Technologies plc) with

chemistry version R 10.4.1. The library loading concentration was

20 fmol and the software used for analysis (basecalling and

alignment) was MinKNOW Version 25.02 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies

plc). The detailed library preparation and sequencing steps were

carried out according to the publicly available Nanopore protocol

on the Nanopore Community webpage. The present study aimed to

obtain low coverage whole genome sequencing, and thus the

sequencing was carried out for 3 h until the raw data in POD5

format reached ~50 GB. The sequencing was then interrupted and

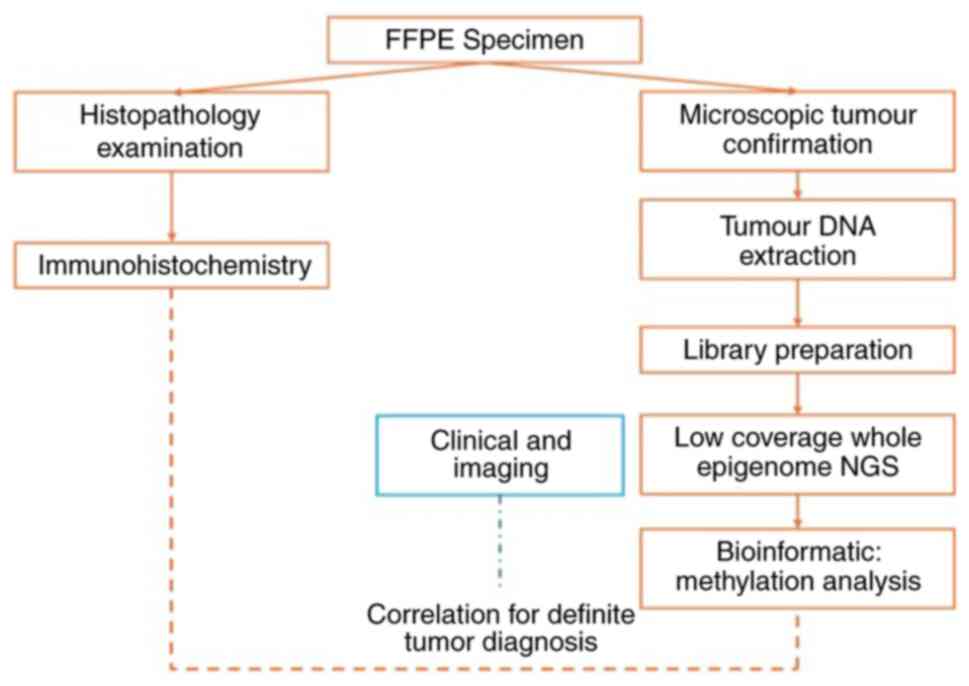

stopped. The overview process for molecular testing, from IHC and

methylation testing to correlation with clinical and imaging data,

is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Methylation analysis

After sequencing was completed, post-run basecalling

was performed using the dna_r10.4.1_e8.2_400bps_sup@v5.0.0

model, which included 5mCG and 5hmCG base modification calling with

Dorado (18). The methylation

analysis was then carried out using NanoDx pipeline, which is

publicly available (12,19). Briefly, the basecalled sequencing

reads were aligned to the hg19 human reference genome using

Minimap2(20). Methylation

information was then extracted using Modkit version 0.4.0

(https://github.com/nanoporetech/modkit), which

provides single-base resolution of methylation data. The

methylation matrix was then constructed representing all CpG sites.

Furthermore, dimensionality reduction using t-SNE was applied to

visualise and analyse the high-dimensional methylation data. The

methylation data was classified using the public Heidelberg brain

tumour classifier v11b4 reference set (21).

Clinical findings

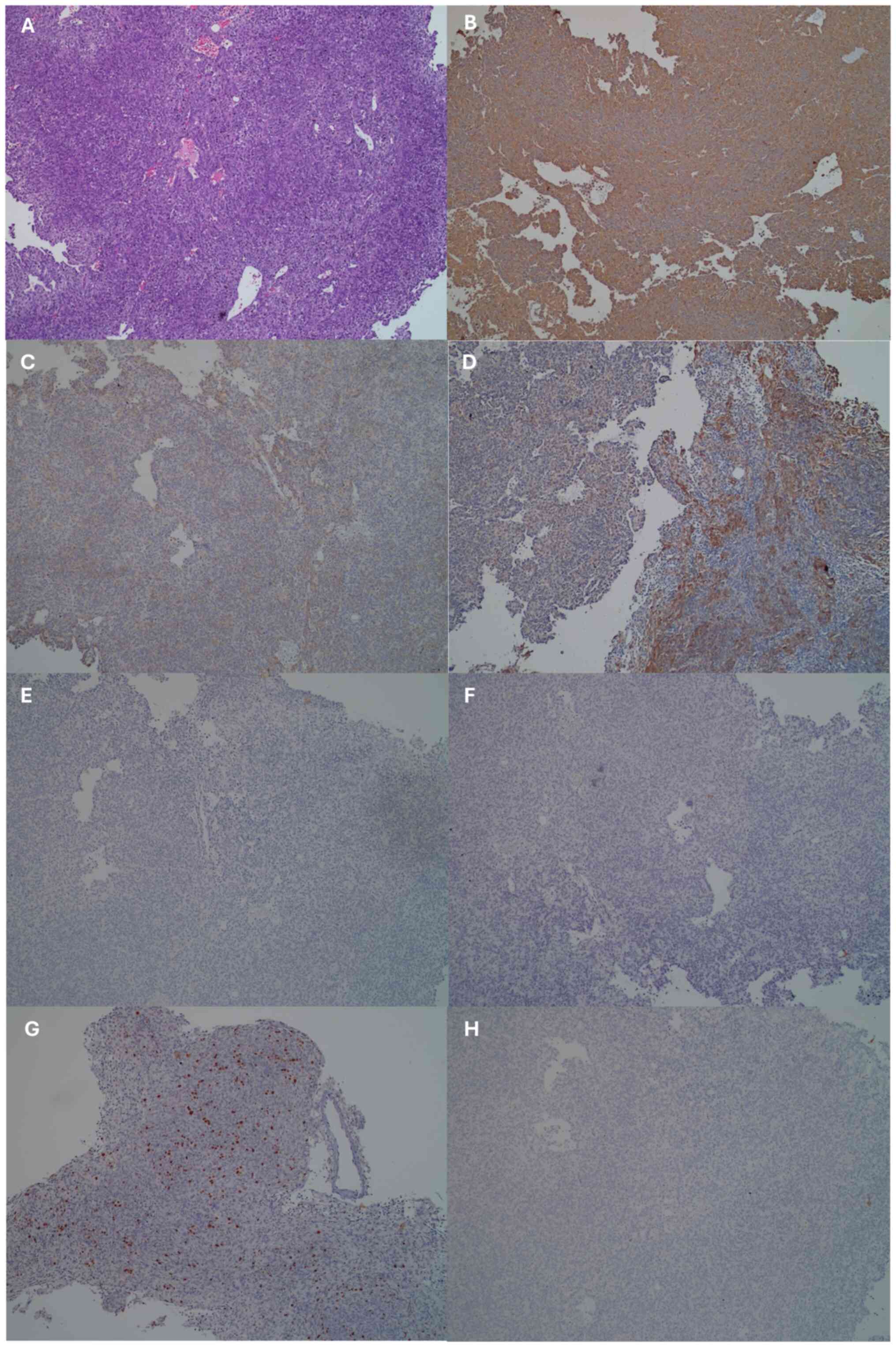

The histopathology results revealed a tumour mass

that under microscopic examination, was arranged in irregular short

lines, forming sheets, lobules and a patternless architecture

(Fig. 3A). The tumour cells

exhibited round to oval nuclei with spindle shapes, mild to

moderate pleomorphism, slightly coarse chromatin, and eosinophilic

cytoplasm. The mitotic count was 6 per 10 low-power fields. Blood

vessels appeared partially congested. There was dense infiltration

of macrophages or foamy cells around the tumour. This

histopathological feature was inconclusive, with the histology

suggesting the possibility of meningioma, solitary fibrous tumour,

pituitary adenoma or carcinoma.

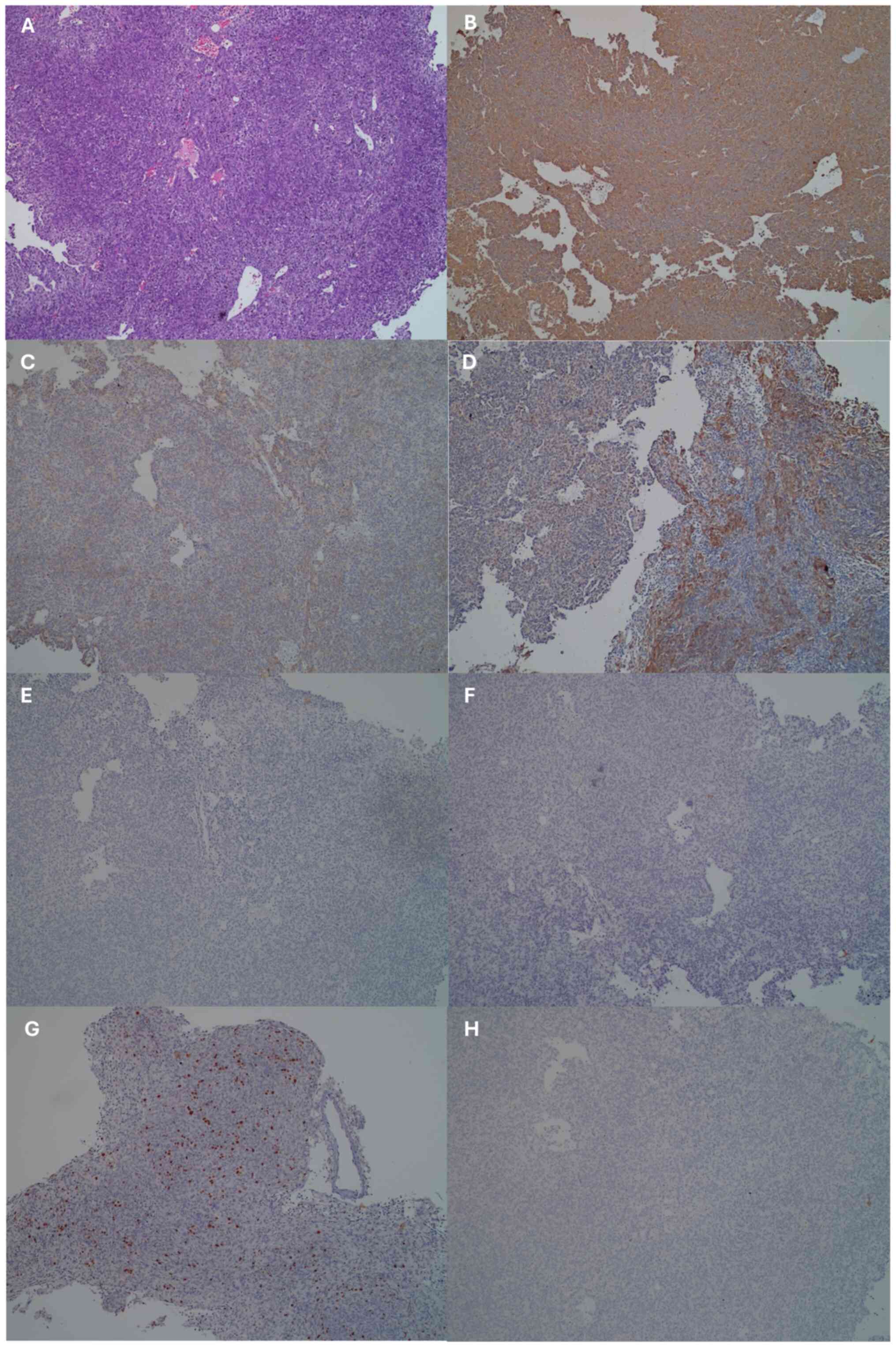

| Figure 3Histopathology and

immunohistochemical findings. (A) Haematoxylin and eosin staining.

(B-H) Immunohistochemical staining of the following markers: (B)

Vimentin, (C) EMA, (D) AE1/3, (E) S100, (F) PR, (G) Ki-67 and (H)

synaptophysin. All images were obtained at a magnification of x100.

EMA, mucin 1, cell surface associated. EMA, mucin 1, cell surface

associated; AE1/3, pan-cytokeratin antibody cocktail; S100,

calcium-binding proteins; PR, progesterone receptor. |

IHC was performed and the results obtained from all

the tested markers are summarized in Table II, Fig.

3B-H, and Fig. S1. The Ki-67

index of up to 20% was indicative of moderately high proliferative

activity, suggesting a potentially aggressive tumour. Positive BRAF

V600E expression suggested the presence of this mutation in the

tumour, which was also indicative of a more aggressive tumour and

poorer prognosis. The findings of IHC indicated partial epithelial

and mesenchymal marker expression (Vimentin, AE1/3 and EMA) and

BRAF V600E positivity, along with negative markers for neural and

neuroendocrine differentiation, suggesting that the tumour may be a

type of mixed epithelial-mesenchymal tumour or a variant of glioma

or meningioma with complex differentiation. The neuropathologist

concluded that this was more likely a craniopharyngioma. The

ambiguous morphological findings on the histopathology and atypical

expression were likely due to prior high-dose stereotactic

radiotherapy to the tumour. Based on the histopathology and

immunohistochemical results alone, a definitive classification

could not be made; however, the most likely diagnosis was

craniopharyngioma.

| Table IIResults of immunohistochemical

analysis. |

Table II

Results of immunohistochemical

analysis.

| Immunohistochemical

marker | Result |

|---|

| Vimentin | Expressed in most

tumour cells |

| AE1/3 | Positive in some

tumour cells |

| EMA | Positive in some

tumour cells |

| p63 | Positive in some

tumour cells |

| S100 | Negative |

| Synaptophysin | Negative |

| Chromogranin | Negative |

| PR | Negative |

| CD34 | Only expressed in

vessel walls |

| Ki-67 | Increased,

variable, up to 20% in some areas |

| p40 | Positive in some

tumour cells |

| CK7 | Positive in some

tumour cells |

| CK8 | Positive in some

tumour cells |

| CK19 | Positive in some

tumour cells |

| HMWCK | Positive in some

tumour cells |

| Cam5.2 | Positive in some

tumour cells |

| CK20 | Negative |

| ER | Negative |

| STAT6 | Expressed in tumour

cells (cytoplasmic reactivity, rather than nucleus) |

| TTF-1 | Negative |

| BRAF V600E | Positive in most

tumour cells |

| Beta catenin | Cytoplasmic and

membranous expression in some tumour cells |

| TLE-1 | Positive in some

tumour cells with weak intensity |

| BCL2 | Expressed in some

(few) tumour cells |

| CD99 | Weak cytoplasmic

and membranous expression in some tumour cells |

| CD56 | Positive in a small

number of tumour cells |

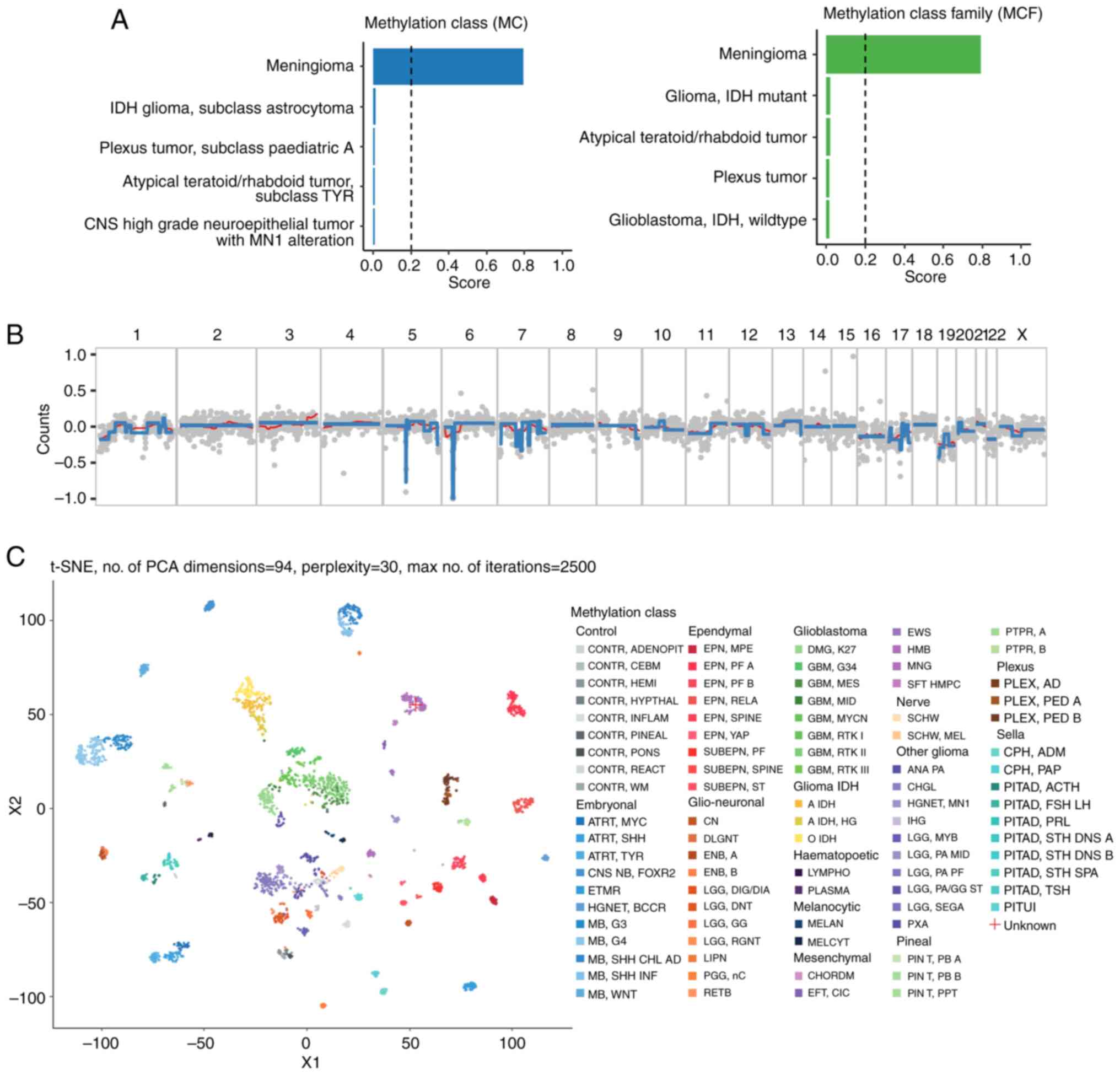

Further molecular analysis was performed using NGS

to conduct direct sequencing in order to detect random whole genome

methylation from the tumour DNA. The methylation classification

analysis of the CNS tumour sample identified the tumour as a

meningioma at both the methylation class and methylation class

family levels. The confidence score for this classification was

0.791, which was above the commonly used threshold of 0.2,

indicating a reliable prediction. The Heidelberg classifier,

validated in large cohorts, demonstrates a sensitivity of 92-95%

and specificity of 90-93% for meningioma classification in

untreated cases (22-24),

although its performance in irradiated tumours remains less well

studied. In this context, the 0.791 score suggests reliable

discrimination despite post-treatment complexity. This results

suggested that the epigenetic profile of the tumour was most

consistent with meningioma when compared to the reference profiles

of CNS tumours. Additionally, the classification was supported by

the absence of strong signals for other CNS tumour entities among

the top five categories, which included high-grade neuroepithelial

tumours, atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumours, and various gliomas

(Fig. 4A).

The copy number variation (CNV) profile, shown in

Fig. 4B, was generated based on

low-coverage whole genome sequencing data. Due to the low coverage,

the resolution of the CNV analysis may be limited, and fine-scale

alterations could be missed. Nonetheless, it provided an overview

of the broader chromosomal changes present in the tumour specimen.

Overall, the CNV plot revealed regions with potential copy number

gains (positive log2 values represented by red bars) and losses

(negative log2 values represented by blue bars) across multiple

chromosomes. The copy number profile showed relative stability

across most chromosomes, with the majority of regions falling

within the-0.5 to 0.5 range on the y-axis, indicating no major

large-scale chromosomal gains or losses.

Chromosome 5 and 6 exhibited large segments of copy

number loss, indicating possible deletions. A slight gain was

visible on the q arm of chromosome 1, extending approximately from

the middle to the end of the chromosome. The 1q gain observed in

the copy number profile was consistent with the classification of a

meningioma, as gain of 1q is a known recurrent alteration in

certain meningioma subtypes (25).

Chromosome 22 had a noticeable deletion, which was consistent with

known chromosomal patterns in meningiomas (26,27).

Despite the lower resolution of this analysis, these broad CNV

changes provide valuable insights into the overall genomic

landscape of the tumour and could serve as a preliminary indicator

for further validation using higher-coverage sequencing

methods.

The dimensionality reduction plot further

corroborated this classification by visually clustering the sample

close to the meningioma reference group, distinct from other tumour

classes such as glioblastomas or embryonal tumours (Fig. 4C). This visualization tool, while

only qualitative, reinforces the classification outcome by showing

that the methylation pattern of the sample overlaps predominantly

with meningioma profiles. Given the relatively high number of CpG

sites used in the classification (11,653 sites), the prediction was

considered robust, as it comprehensively covered relevant loci for

distinguishing CNS tumour types. A final diagnosis was obtained

following multidisciplinary assessment of all available data, and

considered this entity to be a meningioma. Compared with IHC, which

required 5-10 days and yielded inconclusive results, methylation

profiling provided a definitive diagnosis in 4-7 days (from DNA

extraction to classification), with an estimated accuracy of

>90% based on classifier benchmarks (21,23,24).

This quantitative advantage highlights the superiority of

methylation profiling in both speed and diagnostic precision,

particularly in complex cases.

Discussion

The present case report highlights the complexities

encountered in diagnosing CNS tumours post-radiation therapy. The

patient's initial clinical presentation and radiological features

were consistent with a meningioma. However, following Gamma Knife

treatment and subsequent tumour recurrence, the histopathological

and immunohistochemical profiles suggested craniopharyngioma, a

diagnosis with a vastly different therapeutic approach. The

discordance between clinical and pathological findings was likely

attributable to radiation-induced histological alterations

(28).

The immunohistochemical result of the proliferation

marker Ki-67 showed increased expression in some areas, reaching up

to 20%, indicative of a moderate proliferative index, which

suggests an intermediate to high level of tumour aggressiveness.

The positive BRAF V600E expressed in a substantial portion of

tumour cells was extremely rare in meningioma, even in grade 3

meningioma (29). It is commonly

mutated in certain gliomas, gangliogliomas and melanomas (30). The presence of the BRAF V600E

mutation is associated with more aggressive behavior in certain

types of cancer (31). In this

case, the mutation was likely acquired secondararily following

radiation therapy. Based on the immunohistochemical profile, it was

unlikely to be a meningioma.

The discordance between clinical, imaging,

histopathology and immunohistochemical findings hindered appropiate

management of the patient. Such cases underscore the limitations of

conventional histopathology and IHC, in the context of previously

treated tumours. Radiation can induce both morphological and

molecular changes, including altered expression of key diagnostic

markers. This phenomenon poses a significant challenge in

distinguishing true recurrence from treatment-related effects.

Methylation profiling emerged as a critical

diagnostic tool in this scenario, providing a definitive

classification based on the intrinsic epigenetic landscape of the

tumour. The methylation profile has been shown to be conserved

between primary and metastatic samples (32), although the driver mutations may

differ. Evidence from ovarian cancer, which is often heavily

treated with chemotherapeutic agents and prone to recurrance, has

shown that the methylation signature is preseerved between primary

and recurrent tumours (33).

Meningioma methylation profiles typically exhibit

hypermethylation at HOX gene clusters and hypomethylation at cell

cycle regulatory genes, distinguishing them from other CNS tumours

(34,35). For comparison, glioblastomas exhibit

widespread hypomethylation of oncogenes such as EGFR and

hypermethylation of tumour suppressor genes such as MGMT, patterns

that correlate with aggressive proliferation and resistance to

therapy (16,36,37).

Craniopharyngiomas, initially suspected in this case, display

distinct WNT/β-catenin pathway activation, linked to their

epithelial differentiation and cystic growth patterns (38-40).

In this case, the absence of WNT pathway activation, evidenced by

negative β-catenin staining, aided in ruling out

craniopharyngioma.

While meningioma methylation signatures are often

correlated with the risk of recurrence (such as hypermethylation at

NF2 in aggressive subtypes) (41),

physiological associations in irradiated cases remain underexplored

due to limited post-treatment data. A definitive link between the

observed methylation patterns and specific physiological traits

such as proliferation or invasiveness could not be established, as

this would require functional studies which were beyond the scope

of the present work. However, the conserved methylation profile

observed despite prior radiation, aligns with evidence from other

cancers, such as ovarian cancer, where methylation signatures

remain stable between primary and recurrent tumours despite

treatment (33).

Moreover, the copy number profile did not show any

substantial deviations that would suggest chromosomal aberrations

typical of more aggressive gliomas or embryonal tumours, which

often present with distinct copy number alterations (36). This finding aligns with the

relatively stable genomic profile typically observed in

meningiomas, especially in non-anaplastic forms. Collectively,

these findings provide a strong molecular basis for classifying the

sample as a meningioma, with implications for the prognosis of the

patient and potential therapeutic strategies.

The identification of a meningioma-specific

methylation signature was pivotal in resolving the present case.

With a conclusive diagnosis of meningioma, it is now understood

that gross total resection should be pursued in the event of

recurrence, an approach not typically required in cases of

craniopharyngioma. This demonstrated the utility of methylation

profiling as a complementary diagnostic approach for challenging

CNS tumours. Incorporating such advanced molecular techniques into

routine diagnostics can enhance the accuracy of CNS tumour

classification, particularly for complex cases where conventional

methods fall short (42). Adopting

methylation profiling as a standard in neuro-oncology could

transform diagnostics, particularly for recurrent CNS tumours with

treatment-altered histopathology. Unlike targeted gene panels,

which focus on specific mutations (such as IDH1/2) and may miss

broader epigenetic context, or RNA sequencing, which is sensitive

to RNA degradation in FFPE samples (43), methylation profiling offers a

stable, genome-wide view of tumor biology (44). Therefore, methylation profiling can

outperform gene panels in classifying ambiguous cases and is more

robust than RNA sequencing in post-treatment settings.

Cost-effectiveness is a key consideration. While the

initial setup cost for NGS platforms such as Oxford Nanopore

exceeds IHC, the improved diagnostic accuracy can reduce downstream

costs from misdiagnosis or unnecessary treatments, potentially

saving thousands of dollars per patient. Barriers to implementation

include limited access to equipment, the need for specialized

technical expertise, poor DNA quality of FFPE samples for NGS, and

challenges integrating these methods into clinical workflows,

particularly in resource-limited settings. However, declining

sequencing costs, improved NGS technology, and scalable protocols

(such as low-coverage approaches) could mitigate these challenges.

Overall, the analysis of the present study highlighted the utility

of methylation profiling in providing a precise, molecular-based

classification of CNS tumours, particularly in cases where

histopathological evaluation may be challenging. The integration of

methylation data with genomic information, as demonstrated in the

present study, is critical in the context of CNS tumours, where the

accurate classification can directly influence clinical

decision-making and patient management strategies. In conclusion,

methylation signatures can provide a robust, treatment-resistant

classification method, offering clarity in diagnostically

challenging cases and guiding appropriate therapeutic strategies.

Future research should focus on expanding the CNS methylation

classifier to include post-treatment profiles, validating its

utility across diverse tumour types, and assessing long-term

outcomes of methylation-guided management. Standardizing protocols

and addressing cost barriers will further enhance its integration

into routine diagnostics, improving patient outcomes in complex

neuro-oncology cases.

Supplementary Material

Immunohistochemical findings of

various markers. (A) p63, (B) chromogranin, (C) CD34, (D) p40, (E)

CK7, (F) CK8, (G) CK19, (H) HMWCK, (I) Cam5.2, (J) CK20, (K) ER,

(L) STAT6, (M) TTF-1, (N) BRAF V600E, (O) β-catenin, (P) TLE-1, (Q)

BCL2, (R) CD99, and (S) CD56. All images were obtained at a

magnification of x100. CD34, cluster of differentiation 34; p40,

ΔNp63 isoform of the p63 protein; CK7, cytokeratin 7; CK19,

cytokeratin 19; HMWCK, high molecular weight cytokeratin; Cam5.2,

anti-cytokeratin antibody; CK20, cytokeratin 20; ER, estrogen

receptor; STAT6, signal transducer and activator of transcription

6; TTF-1, thyroid transcription factor-1; BRAF V600E, B-Raf

proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase, with V600E mutation

(Val600Glu); TLE-1, transducin-like enhancer of split 1; BCL2,

B-cell lymphoma 2; CD99, cluster of differentiation 99; CD56,

cluster of differentiation 56.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present case report was supported by the PUTI grant

from the University of Indonesia (grant no.

NKB-412/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2023).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the SRA database under accession no. PRJNA1240044 (SRA accession

no. SRR32801446) or at the following URL: https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1240044?reviewer=hgbuness2eea3b45vlvo9bb134.

Authors' contributions

H contributed to the conceptualization, methodology,

investigation, formal analysis, and writing of the original draft.

ES contributed to acquisition of data, visualization and the

writing, review and editing of the manuscript. RA contributed to

conceptualization, resources, investigation, as well as the

writing, review and editing of the manuscript. TA contributed to

the conceptualization, investigation, as well as the writing,

review and editing of the manuscript. HW contributed to the

interpretation of data, obtaining resources, project

administration, as well as the writing, review and editing of the

manuscript. TBMP contributed to the conceptualization and funding

acquisition, as well as the writing, review and editing of the

manuscript. SAG contributed to the conceptualization, supervision,

obtaining resources, and funding acquisition, as well as the

writing, review and editing of the manuscript. H and ES confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors contributed equally

to this study, and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed in line with the

principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval (ethics

approval no. KET-289/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2024) was granted by the

Ethics Committee of the University of Indonesia (Jakarta,

Indonesia). Written informed consent was secured from the patient

prior to molecular testing, ensuring full disclosure of the study's

purpose, procedures, and potential use of biological specimens for

research.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was secured from the

patient prior to molecular testing for the use of any patient data

or associated images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kristensen BW, Priesterbach-Ackley LP,

Petersen JK and Wesseling P: Molecular pathology of tumors of the

central nervous system. Ann Oncol. 30:1265–1278. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ,

Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, Hawkins C, Ng HK, Pfister SM,

Reifenberger G, et al: The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the

central nervous system: A summary. Neuro Oncol. 23:1231–1251.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Smith HL, Wadhwani N and Horbinski C:

Major features of the 2021 WHO classification of CNS tumors.

Neurotherapeutics. 19:1691–1704. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Singer LS, Feldman AZ, Buerki RA,

Horbinski CM, Lukas RV and Stupp R: The impact of the molecular

classification of glioblastoma on the interpretation of therapeutic

clinical trial results. Chin Clin Oncol. 10(38)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Wood MD, Beadling C, Neff T, Moore S,

Harrington CA, Baird L and Corless C: Molecular profiling of pre-

and post-treatment pediatric high-grade astrocytomas reveals

acquired increased tumor mutation burden in a subset of

recurrences. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 11(143)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ng WK: Radiation-associated changes in

tissues and tumours. Curr Diagn Pathol. 9:124–136. 2003.

|

|

7

|

Umekawa M, Shinya Y, Hasegawa H, Morshed

RA, Katano A, Shinozaki-Ushiku A and Saito N: Ki-67 labeling index

predicts tumor progression patterns and survival in patients with

atypical meningiomas following stereotactic radiosurgery. J

Neurooncol. 167:51–61. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Verma N, Cowperthwaite MC, Burnett MG and

Markey MK: Differentiating tumor recurrence from treatment

necrosis: A review of neuro-oncologic imaging strategies. Neuro

Oncol. 15:515–534. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Smith EJ, Naik A, Shaffer A, Goel M, Krist

DT, Liang E, Furey CG, Miller WK, Lawton MT, Barnett DH, et al:

Differentiating radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence: A

systematic review and diagnostic meta-analysis comparing imaging

modalities. J Neurooncol. 162:15–23. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Cacciotti C, Lenzen A, Self C and

Pillay-Smiley N: Recurrence patterns and surveillance imaging in

pediatric brain tumor survivors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol.

46:e227–e232. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Lebrun L, Gilis N, Dausort M, Gillard C,

Rusu S, Slimani K, De Witte O, Escande F, Lefranc F, D'Haene N, et

al: Diagnostic impact of DNA methylation classification in adult

and pediatric CNS tumors. Sci Rep. 15(2857)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Kuschel LP, Hench J, Frank S, Hench IB,

Girard E, Blanluet M, Masliah-Planchon J, Misch M, Onken J,

Czabanka M, et al: Robust methylation-based classification of brain

tumours using nanopore sequencing. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol.

49(e12856)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Park JW, Lee K, Kim EE, Kim SI and Park

SH: Brain tumor classification by methylation profile. J Korean Med

Sci. 38(e356)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Lyko F: The DNA methyltransferase family:

A versatile toolkit for epigenetic regulation. Nat Rev Genet.

19:81–92. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Lee TG, Kim SY, Kim HR, Kim H and Kim CH:

Radiation induces autophagy via histone H4 lysine 20 trimethylation

in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 40:2537–2548.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Brandes AA, Franceschi E, Paccapelo A,

Tallini G, De Biase D, Ghimenton C, Danieli D, Zunarelli E, Lanza

G, Silini EM, et al: Role of MGMT methylation status at time of

diagnosis and recurrence for patients with glioblastoma: Clinical

implications. Oncologist. 22:432–437. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Jin B and Robertson KD: DNA

methyltransferases, DNA damage repair, and cancer. Adv Exp Med

Biol. 754:3–29. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ahsan MU, Gouru A, Chan J, Zhou W and Wang

K: A signal processing and deep learning framework for methylation

detection using Oxford Nanopore sequencing. Nat Commun.

15(1448)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Euskirchen P, Bielle F, Labreche K,

Kloosterman WP, Rosenberg S, Daniau M, Schmitt C, Masliah-Planchon

J, Bourdeaut F, Dehais C, et al: Same-day genomic and epigenomic

diagnosis of brain tumors using real-time nanopore sequencing. Acta

Neuropathol. 134:691–703. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Li H: Minimap2: Pairwise alignment for

nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 34:3094–3100. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Capper D, Jones DTW, Sill M, Hovestadt V,

Schrimpf D, Sturm D, Koelsche C, Sahm F, Chavez L, Reuss DE, et al:

DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system

tumours. Nature. 555:469–474. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Maas SLN, Stichel D, Hielscher T, Sievers

P, Berghoff AS, Schrimpf D, Sill M, Euskirchen P, Blume C, Patel A,

et al: Integrated molecular-morphologic meningioma classification:

A multicenter retrospective analysis, retrospectively and

prospectively validated. J Clin Oncol. 39:3839–3852.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Santana-Santos L, Kam KL, Dittmann D, De

Vito S, McCord M, Jamshidi P, Fowler H, Wang X, Aalsburg AM, Brat

DJ, et al: Validation of whole genome methylation profiling

classifier for central nervous system tumors. J Mol Diagn.

24:924–934. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Priesterbach-Ackley LP, Boldt HB, Petersen

JK, Bervoets N, Scheie D, Ulhøi BP, Gardberg M, Brännström T, Torp

SH, Aronica E, et al: Brain tumour diagnostics using a DNA

methylation-based classifier as a diagnostic support tool.

Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 46:478–492. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ma J, Hong Y, Chen W, Li D, Tian K, Wang

K, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Song L, et al: High copy-number

variation burdens in cranial meningiomas from patients with diverse

clinical phenotypes characterized by hot genomic structure changes.

Front Oncol. 10(1382)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wang JZ, Nassiri F, Landry AP, Patil V,

Liu J, Aldape K, Gao A and Zadeh G: The multiomic landscape of

meningiomas: A review and update. J Neurooncol. 161:405–414.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

da Silveira MA, Ferreira WAS, Amorim CKN,

Brito JRN, Kayath AS, Sagica FDES and de Oliveira EHC: Meningiomas:

An overview of the landscape of copy number alterations in samples

from an admixed population. J Oncol. 2020(3821695)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Whitehouse JP, Howlett M, Federico A, Kool

M, Endersby R and Gottardo NG: Defining the molecular features of

radiation-induced glioma: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Neurooncol Adv. 3(vdab109)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Behling F, Barrantes-Freer A, Skardelly M,

Nieser M, Christians A, Stockhammer F, Rohde V, Tatagiba M,

Hartmann C, Stadelmann C and Schittenhelm J: Frequency of BRAF

V600E mutations in 969 central nervous system neoplasms. Diagn

Pathol. 11(55)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Kowalewski A, Durślewicz J, Zdrenka M,

Grzanka D and Szylberg Ł: Clinical relevance of BRAF V600E mutation

status in brain tumors with a focus on a novel management

algorithm. Target Oncol. 15:531–540. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Attia AS, Hussein M, Issa PP, Elnahla A,

Farhoud A, Magazine BM, Youssef MR, Aboueisha M, Shama M, Toraih E

and Kandil E: Association of BRAFV600E mutation with the

aggressive behavior of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: A

meta-analysis of 33 studies. Int J Mol Sci.

23(15626)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Zhang S, He S, Zhu X, Wang Y, Xie Q, Song

X, Xu C, Wang W, Xing L, Xia C, et al: DNA methylation profiling to

determine the primary sites of metastatic cancers using

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Nat Commun.

14(5686)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Gull N, Jones MR, Peng PC, Coetzee SG,

Silva TC, Plummer JT, Reyes ALP, Davis BD, Chen SS, Lawrenson K, et

al: DNA methylation and transcriptomic features are preserved

throughout disease recurrence and chemoresistance in high grade

serous ovarian cancers. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

41(232)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Huntoon K, Toland AMS and Dahiya S:

Meningioma: A review of clinicopathological and molecular aspects.

Front Oncol. 10(579599)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Hergalant S, Saurel C, Divoux M, Rech F,

Pouget C, Godfraind C, Rouyer P, Lacomme S, Battaglia-Hsu SF and

Gauchotte G: Correlation between DNA methylation and cell

proliferation identifies new candidate predictive markers in

meningioma. Cancers (Basel. 14(6227)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Chen CH, Lin YJ, Lin YY, Lin CH, Feng LY,

Chang IY, Wei KC and Huang CY: Glioblastoma primary cells retain

the most copy number alterations that predict poor survival in

glioma patients. Front Oncol. 11(621432)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Yin A, Etcheverry A, He Y, Aubry M,

Barnholtz-Sloan J, Zhang L, Mao X, Chen W, Liu B, Zhang W, et al:

Integrative analysis of novel hypomethylation and gene expression

signatures in glioblastomas. Oncotarget. 8:89607–89619.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Matsuda T, Kono T, Taki Y, Sakuma I,

Fujimoto M, Hashimoto N, Kawakami E, Fukuhara N, Nishioka H,

Inoshita N, et al: Deciphering craniopharyngioma subtypes:

Single-cell analysis of tumor microenvironment and immune networks.

iScience. 27(111068)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Zhao C, Wang Y, Liu H, Qi X, Zhou Z, Wang

X and Lin Z: Molecular biological features of cyst wall of

adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma. Sci Rep.

13(3049)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Jucá CEB, Colli LM, Martins CS, Campanini

ML, Paixão B, Jucá RV, Saggioro FP, de Oliveira RS, Moreira AC,

Machado HR, et al: Impact of the canonical wnt pathway activation

on the pathogenesis and prognosis of adamantinomatous

craniopharyngiomas. Horm Metab Res. 50:575–581. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Choudhury A, Magill ST, Eaton CD, Prager

BC, Chen WC, Cady MA, Seo K, Lucas CG, Casey-Clyde TJ, Vasudevan

HN, et al: Meningioma DNA methylation groups identify biological

drivers and therapeutic vulnerabilities. Nat Genet. 54:649–659.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Bertero L, Mangherini L, Ricci AA, Cassoni

P and Sahm F: Molecular neuropathology: An essential and evolving

toolbox for the diagnosis and clinical management of central

nervous system tumors. Virchows Arch. 484:181–194. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Lin Y, Dong ZH, Ye TY, Yang JM, Xie M, Luo

JC, Gao J and Guo AY: Optimization of FFPE preparation and

identification of gene attributes associated with RNA degradation.

NAR Genom Bioinform. 6(lqae008)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Zhang P, Lehmann BD, Shyr Y and Guo Y: The

utilization of formalin fixed-paraffin-embedded specimens in high

throughput genomic studies. Int J Genomics.

2017(1926304)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|