Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) is one of the most prevalent

malignancies globally, with an estimated 613,791 new cases reported

in 2022 according to GLOBOCAN 2022(1). Clinically, BC is categorized into

three main subtypes, namely non-muscle-invasive (NMI), MIB and

metastatic BC (2). While NMIBC

accounts for ~80% of initial BC diagnoses and is associated with a

favorable 5-year survival rate >90% (3), it has a 1-year recurrence rate of

15-61%, and a 5-year recurrence rate of 31-78% (4). Its high recurrence rate imposes

substantial healthcare burdens (5-9).

By contrast, MIBC and metastatic BC, accounting for ~25% of all

diagnoses, are associated with aggressive progression and poorer

prognosis (10). Disparities in BC

outcomes are associated with ethnicity, sex and socioeconomic

factors (11-16).

Management strategies for NMIBC and MIBC include transurethral

resection combined with intravesical therapies, such as mitomycin C

and Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (17-21),

and platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical

cystectomy, respectively (10,22).

However, chemotherapy resistance and toxicity underscore the need

for more safe and effective therapeutic agents (22).

Pueraria spp. (Leguminosae), notably P.

lobata and P. thomsonii, are medicinal plants that are

widely distributed in East Asia. The 2020 edition of the Chinese

Pharmacopoeia recognizes the dried roots (radix) of Pueraria

as a source of bioactive compounds, particularly isoflavonoids such

as puerarin, which are the primary active components of

Puerariae radix flavones (PRF) (23-43).

Previous studies demonstrated that PRF exhibit multifaceted

pharmacological properties, such as anti-cancer effects, in colon

(HT-29 cells), cervical (HeLa cells), liver (SMMC-7721 cells) and

breast cancer (HS578T, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells), acute

promyelocytic leukemia (NB4 cells), neuroblastoma (SHSY5Y cells),

pancreatic carcinoma (BxPC-3 cells) and lung cancer (A549 cells)

(44-48).

Despite these findings, the anti-tumor activity of PRF against BC

remains unexplored.

T24 cells serve as the preferred model for research

on invasion, metastasis and drug resistance mechanisms in BC. Their

intrinsic cisplatin resistance (49) makes T24 cells a classical system for

exploring drug mechanisms of action (50) that are widely used in fundamental BC

research (51,52). Moreover, in natural compound

anticancer mechanism studies, most researchers employ single-cell

models to investigate mechanisms of action (47,50).

Therefore, the present study investigates the effects of PRF on

human bladder cancer T24 cells and its underlying molecular

mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Drug preparation and cell culture

PRF (Taobao; purity ≥80%) was dissolved in anhydrous

ethanol to prepare an 8,000 µg/ml stock solution, which was stored

at 4˚C. T24 cells (Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.)

were authenticated by STR profiling (Mayo Clinic Cytogenetics Core)

and confirmed to be free of mycoplasma contamination. Cells were

cultured in RPMI-1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (Shanghai VivaCell Biosciences, Ltd.)

at 37˚C in a humified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cells were

maintained at a density of <1x106 cells/ml and used

within three passages.

MTT assay

Cells (5x10³/well) in 200 µl medium were treated

with 0, 25, 50, 100 and 200 µg/ml PRF at 37˚C for 24 or 48 h.

Following treatment with MTT reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA),

cells were incubated at 37˚C for an additional 4 h. Finally, the

absorbance at 490 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

Acridine orange/ethidium bromide

(AO/EB) fluorescence staining

Following treatment with 0-200 µg/ml PRF at 37˚C for

24 or 48 h, T24 cells were stained with AO/EB (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck

KGaA) in the dark at room temperature for 5 min. Images were

captured under a fluorescence microscope (magnification, x200).

DNA ladder assay

Following incubation with PRF (0, 50, 100 and 200

µg/ml) at 37˚C for 24 or 48 h, 1x106 T24 cells were

collected. Subsequently, genomic DNA was extracted from untreated

and PRF-treated cells using the Apoptosis DNA Ladder Extraction kit

(cat. no. #C0007; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to

the manufacturer's instructions. Finally, 5 µl DNA (containing 1 µg

DNA) was mixed with 6X Loading Buffer and loaded onto a 1% agarose

gel prepared in TBE buffer containing 0.5 µg/ml ethidium bromide

(EB; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Electrophoresis was performed

at a constant voltage of 100 V for 30 min. DNA bands were

visualized under UV irradiation (302 nm) using a gel imaging

system. Caution: Ethidium bromide is a mutagenic agent. All

procedures were conducted with nitrile gloves, and waste was

disposed as hazardous material.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q)PCR

Following the manufacturer's protocols, total RNA

was extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using

the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (cat. no.

#4897030001; Roche Diagnostics). cDNA amplification was performed

in triplicate with the FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (ROX)

kit (cat. no. #4913850001; Roche Diagnostics) on an ABI Prism 7500

system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The primer sequences for

BCL2, BAX, FAS receptor (FAS), FAS ligand (FASL), tumor necrosis

factor receptor 1 (TNFR1), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α),

cysteinyl aspartate-specific protease-3 (CASP3), NF-κB and GAPDH

are listed in Table I. The primers

were designed and synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.

| Table IPrimer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I

Primer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene | Primer sequence,

5'→3' | Product length,

bp |

|---|

| GAPDH |

F:GCATCCTGGGCTACACTG | 103 |

| |

R:TGGTCGTTGAGGGCAAT | |

| BAX |

F:CGGAACTGATCAGAACCATCA | 97 |

| |

R:AGGAGTCTCACCCAACCA | |

| BCL2 |

F:GTGGATGACTGAGTACCTGAAC | 125 |

| |

R:GAGACAGCCAGGAGAAATCAA | |

| CASP3 |

F:CTCCACAGCACCTGGTTATT | 106 |

| |

R:AAATTCAAGCTTGTCGGCATAC | |

| NF-kB |

F:GGTGCGGCTCATGTTTACAG | 85 |

| |

R:GATGGCGTCTGATACCACGG | |

| TNFR1 |

F:CTCCAAATGCCGAAAGGAAATG | 100 |

| |

R:ATAATGCCGGTACTGGTTCTTC | |

| TNFα |

F:CCAGGGACCTCTCTCTAATCA | 106 |

| |

R:TCAGCTTGAGGGTTTGCTAC | |

| FAS |

F:GTGATGAAGGACATGGCTTAGA | 115 |

| |

R:GGGTCACAGTGTTCACATACA | |

| FASL |

F:CATTTAACAGGCAAGTCCAACTC | 105 |

| |

R:CACAAGGCCACCCTTCTTAT | |

The thermocycling conditions were as follows:

Initial denaturation at 50˚C for 2 min and 95˚C for 10 min,

followed by 45 cycles of 95˚C for 15 sec and 60˚C for 1 min. The

relative mRNA expression levels were calculated using the

2-ΔΔCq method (53).

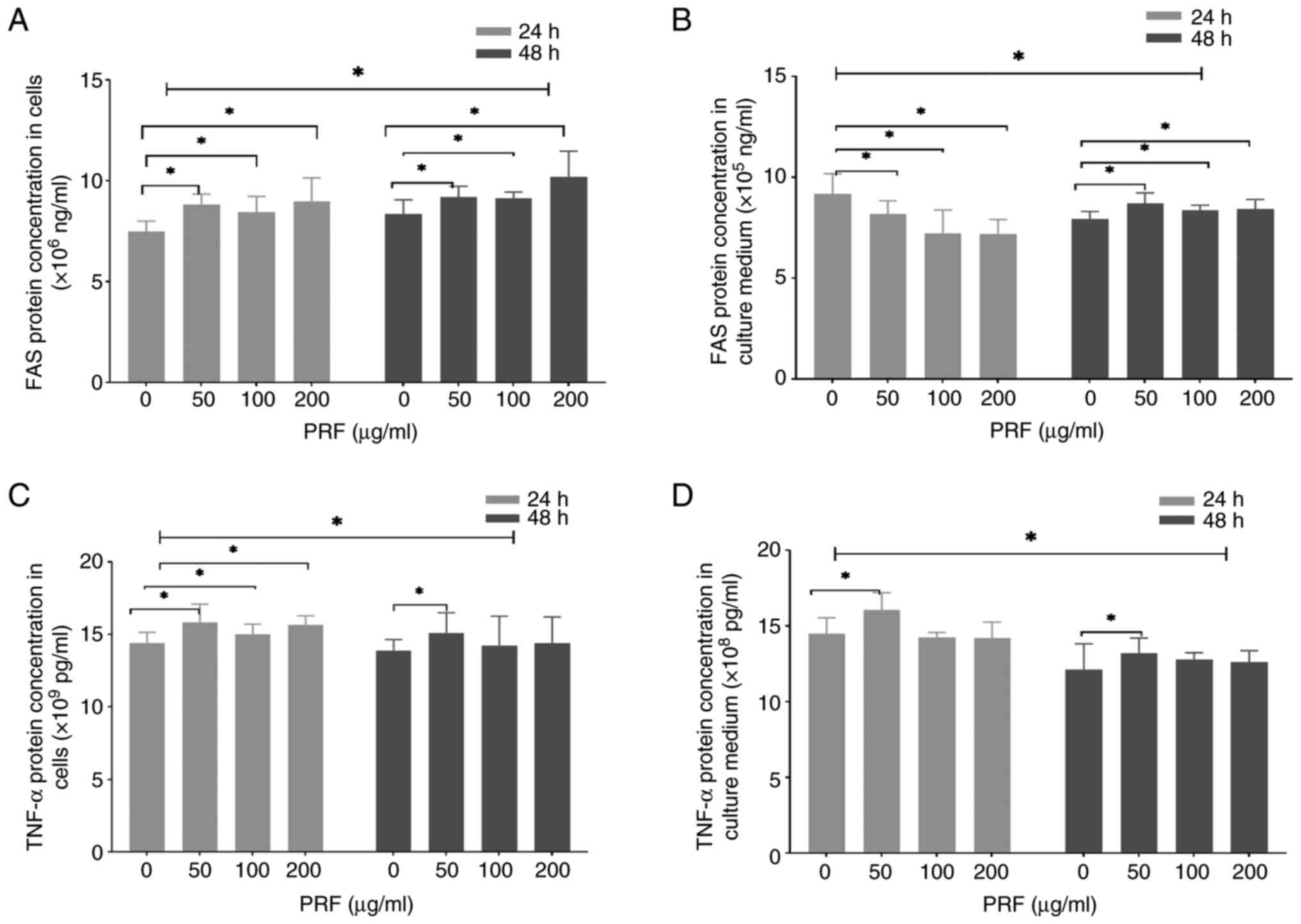

ELISA

Following incubation with PRF (0, 50, 100 and 200

µg/ml) at 37˚C for 24 or 48 h, cells and culture medium were

collected. The protein expression levels of FAS and TNF-α were

quantified in T24 cells and culture supernatant using the

corresponding ELISA kits (cat. nos. #JL14207 and #JL10208,

respectively; both Shanghai Future Industrial Co., Ltd.) according

to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics

(version 25; IBM Corporation) or GraphPad Prism (version 8.1;

GraphPad Software, Inc.; Dotmatics). Experiments were performed in

triplicate, and all data are presented as the mean ± SD. Data were

analyzed using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by

Dunnett's post hoc tests. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

PRF inhibits the viability of T24

cells

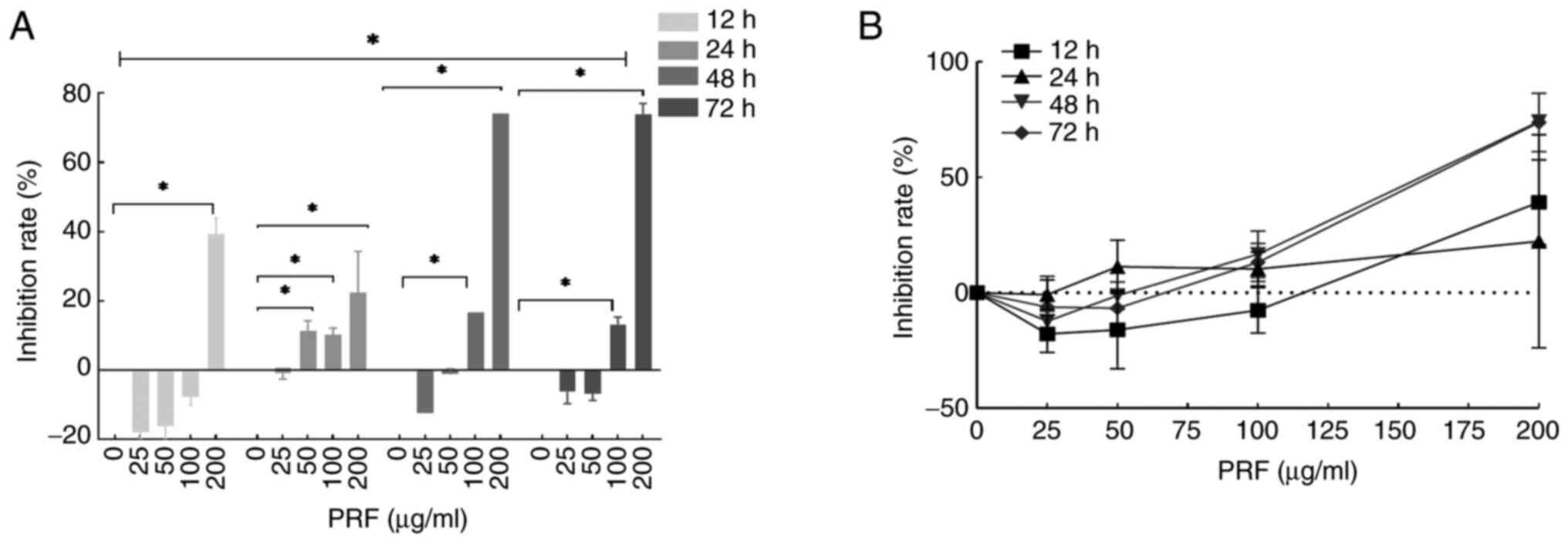

MTT assay demonstrated that PRF could significantly

inhibit the viability of T24 cells in a time- and dose-dependent

manner (Fig. 1A). The inhibition

rate in cells treated with 200 µg/ml PRF for 12 h was significantly

higher compared with that in the control group (Fig. 1A). Additionally, the inhibition

rates of cells exposed to 50, 100 and 200 µg/ml PRF for 24 h were

all increased compared with the control group. Consistently, at 48

and 72 h, the inhibition rates in the 100 and 200 µg/ml PRF-treated

groups were significantly higher compared with the control group.

PRF exhibited a clear dose- and time-dependent inhibitory effect on

cell viability, with inhibition increasing with enhanced

concentration and exposure duration (Fig. 1B). Significant differences in

inhibition rates were observed between time points (12, 24, 48 and

72 h).

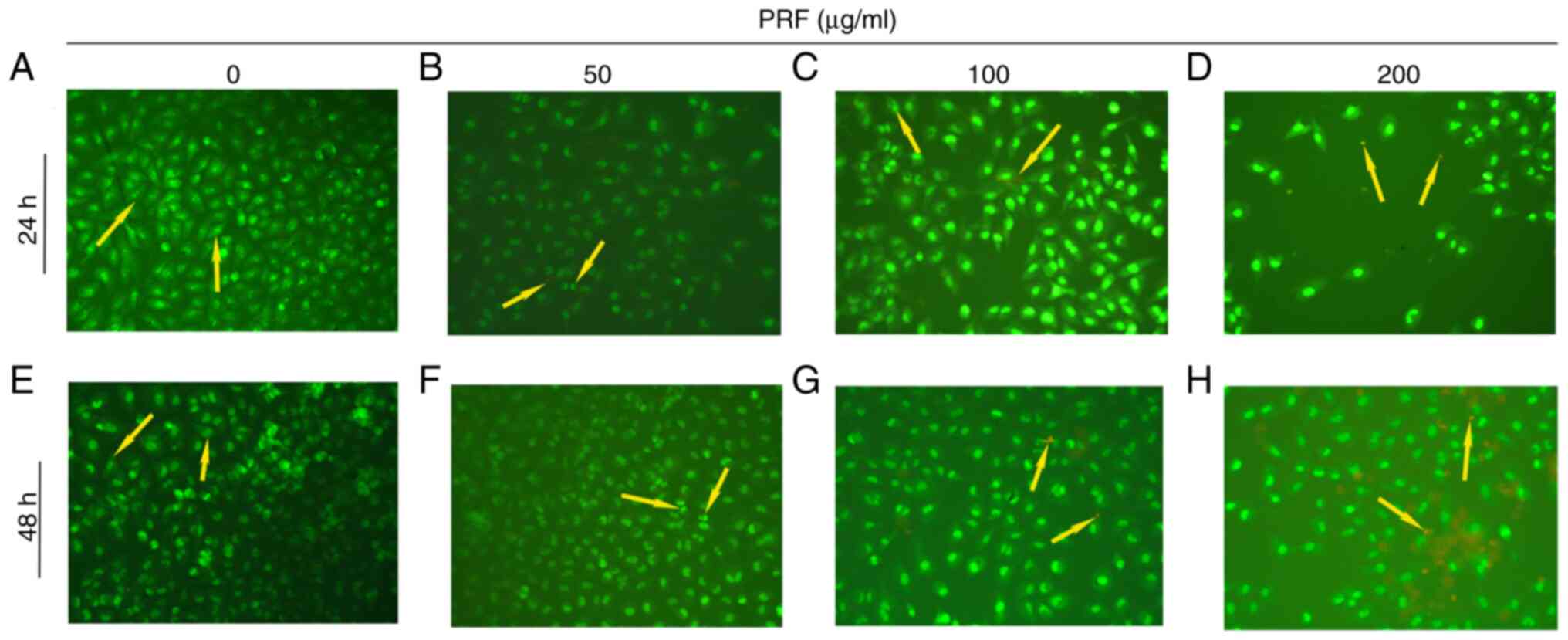

Morphological changes in T24 cells

treated with PRF

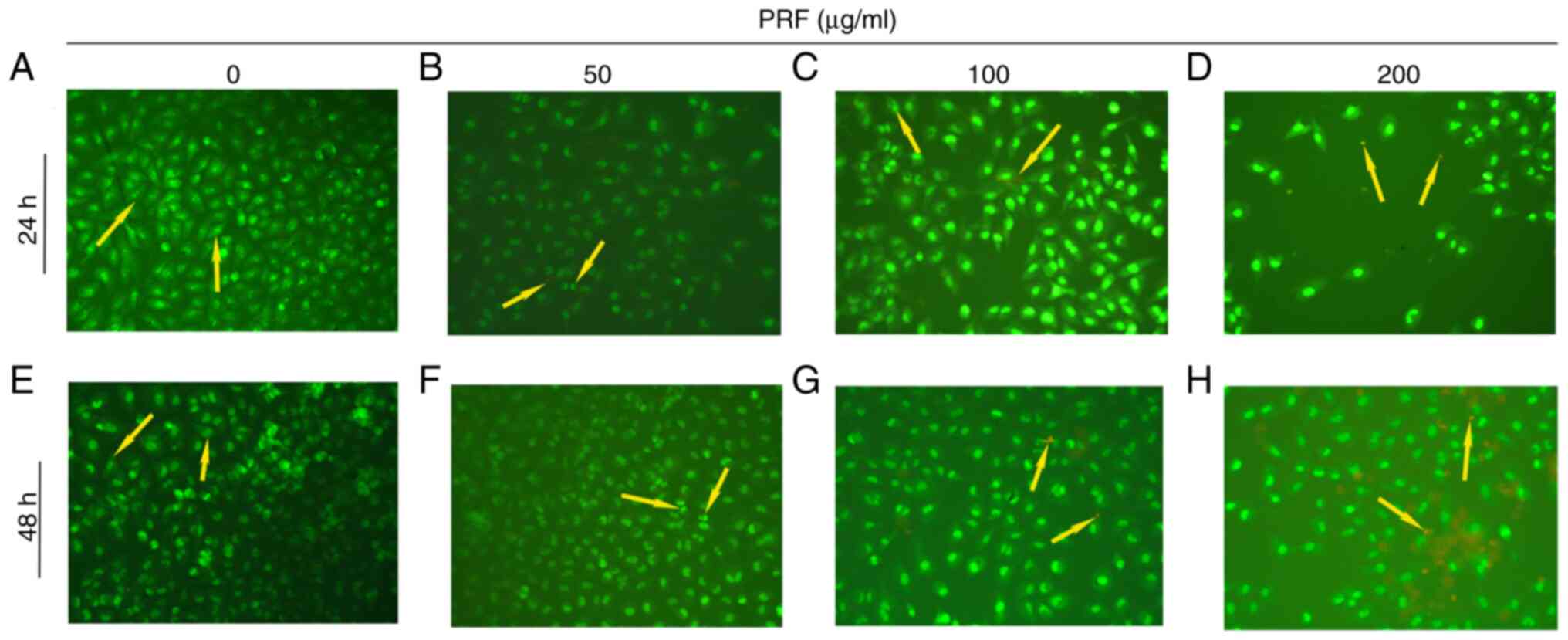

AO/EB staining revealed distinct apoptotic

progression in T24 cells (Fig. 2).

Increasing PRF concentrations induced a progressive fluorescence

shift from green to orange-red emission. Morphologically, cells

progressed from intact plasma membranes with uniform chromatin

distribution to display early apoptotic hallmarks (cellular

shrinkage, nuclear condensation, and apoptotic body formation) and

late-stage apoptosis typified by membrane rupture, chromatin

fragmentation, and nuclear dissolution. Control cells exhibited a

uniform green staining (Fig. 2A and

E). However, 50 µg/ml PRF induced

early apoptotic features, such cell shrinkage, condensed nuclei and

apoptotic bodies (Fig. 2B and

F). Additionally, higher PRF

concentrations (100-200 µg/ml) induced features of late apoptosis,

including enhanced membrane permeability, chromatin fragmentation

(orange/red staining) and nuclear disintegration (Fig. 2C, D,

G and H). Notably, 100-200 µg/ml PRF exposure for

24-48 h promoted concentration- and time-dependent morphological

alterations, characteristic of late-stage apoptosis.

| Figure 2Acridine orange/ethidium bromide

staining of T24 cells exposed PRF. (A) Control for 24 h, the yellow

arrow indicates viable T24 cells exhibiting green fluorescence with

intact plasma membranes. (B) 50 µg/ml and 24 h, yellow arrow

indicates early apoptotic cells demonstrating green fluorescence

with punctate orange-red fluorescence, along with characteristic

morphological changes including cell shrinkage, nuclear

condensation, and apoptotic body formation. (C) 100 µg/ml and 24 h,

yellow arrow indicates apoptotic cells in early and late stages,

exhibiting green fluorescence accompanied by orange-red

fluorescence. Early-stage cells show apoptotic body formation,

while late-stage cells display plasma membrane disintegration,

chromatin fragmentation, and diffuse nuclear orange-red

fluorescence. (D) 200 µg/ml and 24 h, the yellow arrow indicates

late apoptotic cells exhibiting orange-red fluorescence,

characterized by chromatin fragmentation and nuclear

disintegration. (E) Control and 48 h, the yellow arrow indicates

viable T24 cells exhibiting green fluorescence with intact plasma

membranes. (F) 50 µg/ml and 48 h, yellow arrow indicates early

apoptotic cells demonstrating green fluorescence with punctate

orange-red fluorescence, along with characteristic morphological

changes including cell shrinkage, nuclear condensation, and

apoptotic body formation. (G) 100 µg/ml and 24 h, yellow arrow

indicates apoptotic cells in early and late stages, exhibiting

green fluorescence accompanied by orange-red fluorescence.

Early-stage cells show apoptotic body formation, while late-stage

cells display plasma membrane disintegration, chromatin

fragmentation and diffuse nuclear orange-red fluorescence. (H) 200

µg/ml and 48 h, the yellow arrow indicates late apoptotic cells

exhibiting orange-red fluorescence, characterized by chromatin

fragmentation and nuclear disintegration. Magnification, x200. PRF,

Puerariae radix flavone. |

Assessment of DNA fragmentation in T24

cells following PRF treatment

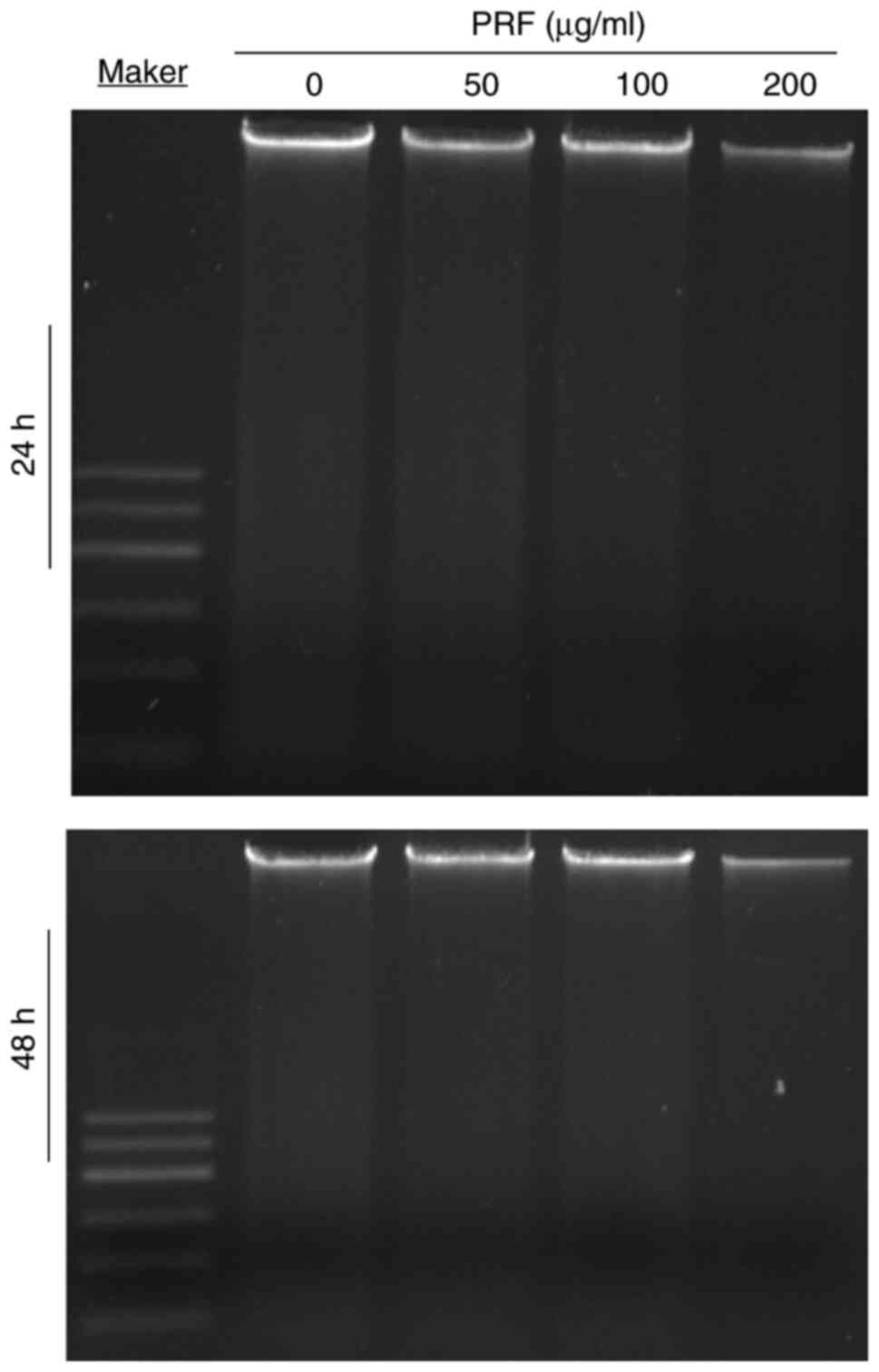

The DNA ladder assay showed no apoptotic

fragmentation in T24 cells treated with PRF (0-200 µg/ml) for 24-48

h, thus suggesting that PRF-induced apoptosis was triggered via a

DNA fragmentation-independent pathway (Fig. 3).

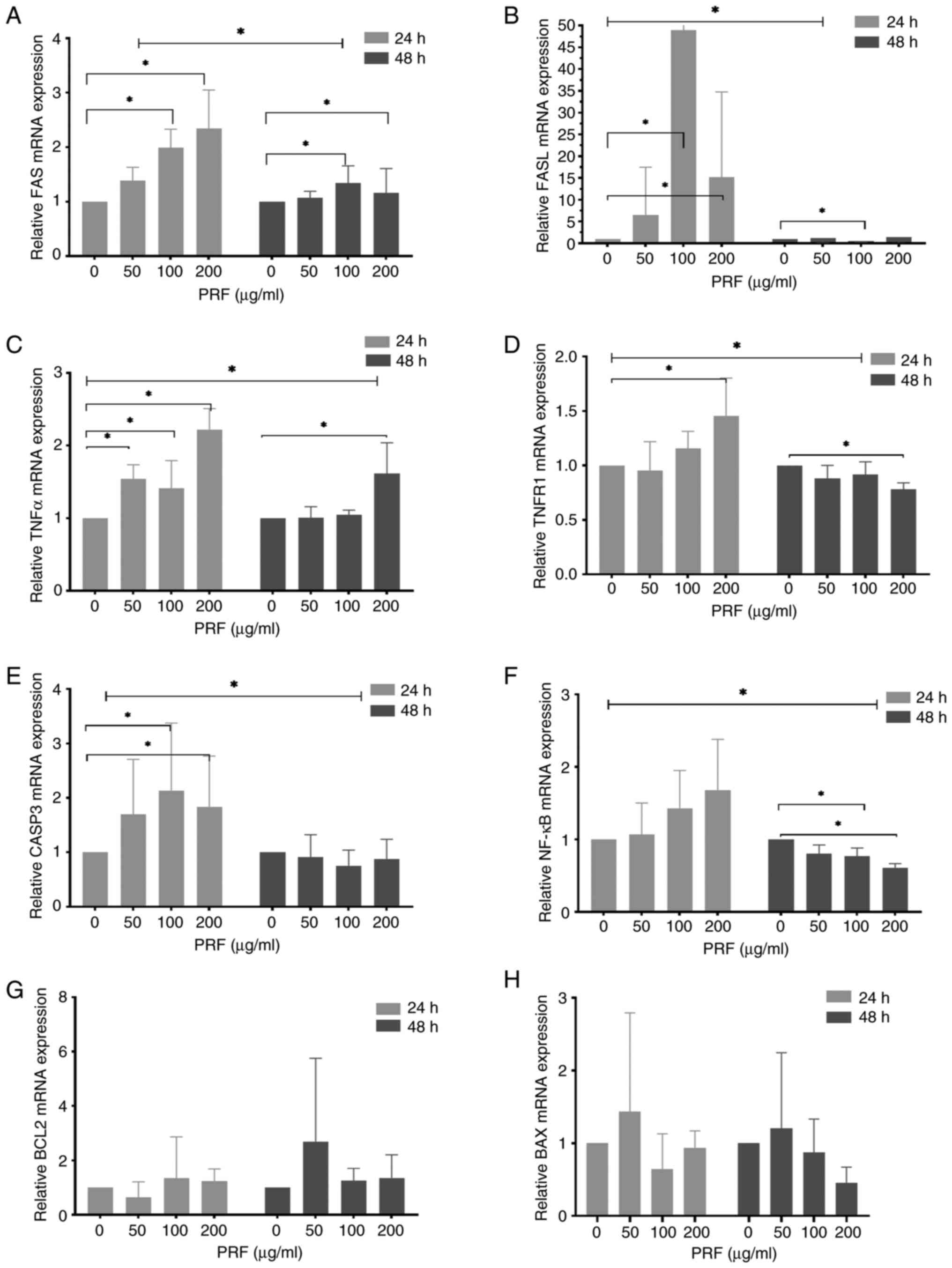

PRF modulates the expression of

apoptosis-related genes

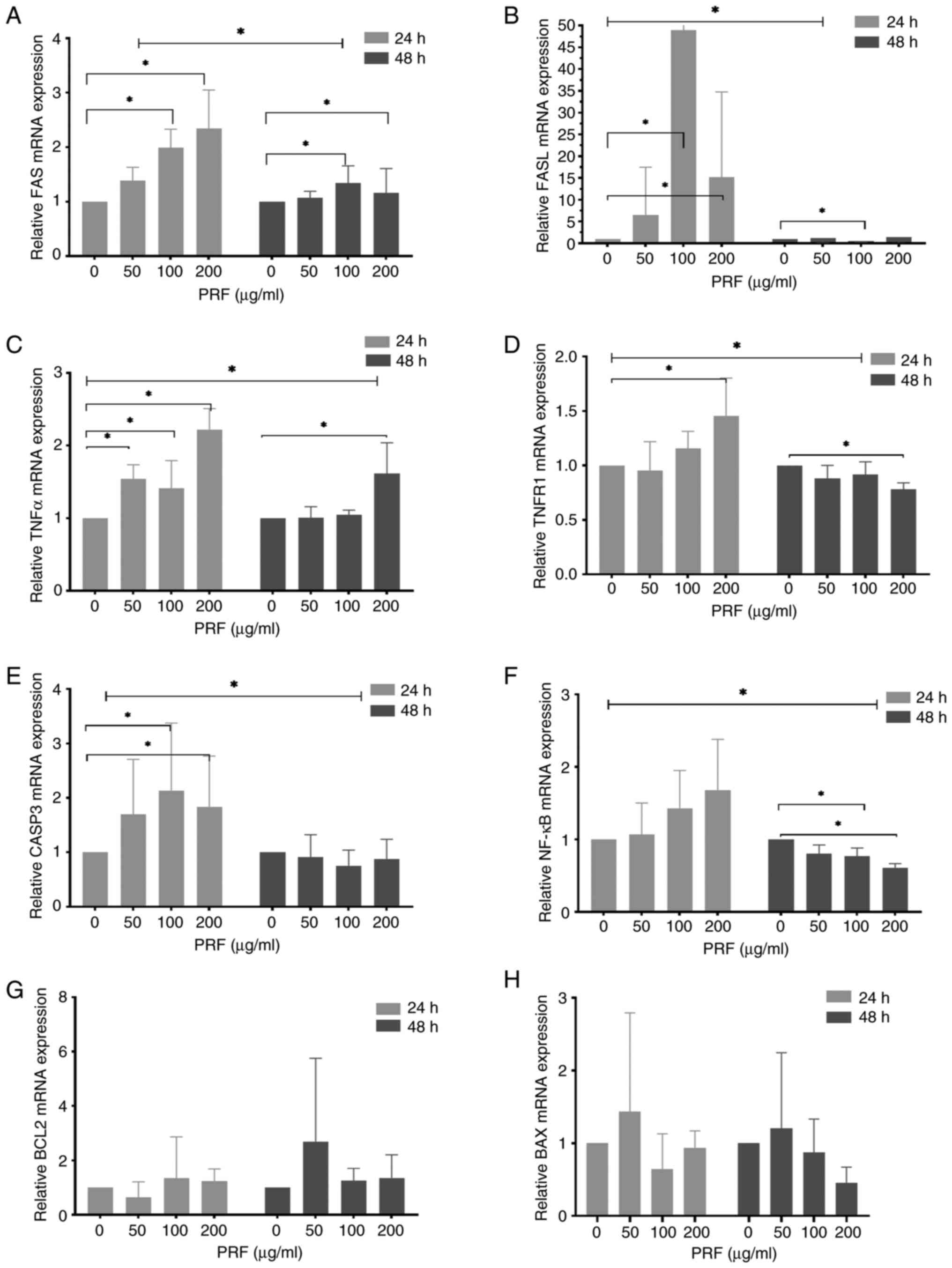

RT-qPCR demonstrated that treatment with 100 or 200

µg/ml PRF for 24 h upregulated FAS (2.0- and 2.3-fold,

respectively), FASL (48.9- and 15.2-fold, respectively), TNF-α

(1.4- and 2.2-fold, respectively) and CASP3 (2.1- and 1.8-fold,

respectively; Fig. 4A-C and

E). However, the expression of

TNFR1 only significantly increased in cells treated with 200 µg/ml

PRF (1.2-fold; Fig. 4D). No

significant changes were observed in the mRNA expression of NF-κB,

BCL-2 and BAX (Fig. 4F-H).

Additionally, treatment with PRF for 48 h slightly upregulated FAS

at 100 and 200 µg/ml (1.3- and 1.2-fold, respectively; Fig. 4A), and markedly upregulated TNF-α at

200 µg/ml (1.6-fold; Fig. 4C). By

contrast, FASL (0.5-fold at 100 µg/ml), TNFR1 (0.8-fold at 200

µg/ml), and NF-κB (0.8- and 0.6-fold at 100 and 200 µg/ml,

respectively) were significantly downregulated (Fig. 4B, D

and F). No significant alterations

were detected in the mRNA expression of CASP3, BCL-2 and BAX

(Fig. 4E, G and H).

| Figure 4Effects of PRF on the expression of

apoptosis-related genes in T24 cells. T24 cells were treated with

PRF (0, 50, 100 and 200 µg/ml) for 24 or 48 h. The mRNA levels of

(A) FAS, (B) FASL, (C) TNFα, (D) TNFR1, (E) CASP3, (F) NF-κB, (G)

BCL2 and (H) BAX were assessed by quantitative PCR (normalized to

GAPDH). *P<0.05. PRF, Puerariae radix

flavones; CASP3, cysteinyl aspartate-specific protease-3. |

PRF modulates the protein expression

of FAS and TNF-α

ELISA showed that treatment with PRF for 24 h

resulted in a dose-dependent increase of intracellular FAS and

TNF-a protein levels (50-200 µg/ml; Fig. 5A and C). By contrast, the secreted levels of FAS

were reduced in the culture supernatant (50-200 µg/ml; Fig. 5B). In addition, the secreted levels

of TNF-α were elevated only at 50 µg/ml (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, T24 cell exposure to

PRF for 48 h dose-dependently increased the intracellular and

secreted levels of FAS (50-200 µg/ml; Fig. 5A and B). However, intracellular and secreted

TNF-α levels were only significantly elevated at 50 µg/ml (Fig. 5C and D).

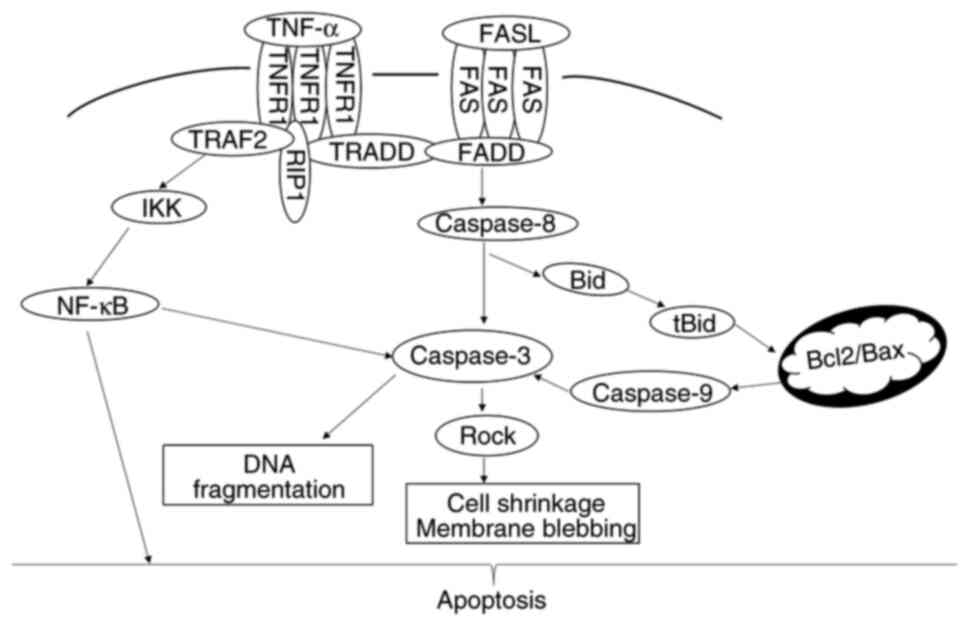

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that treatment with

PRF for 24 and 48 h significantly inhibited T24 cell viability in a

dose- and time-dependent manner, with the most pronounced effects

observed at 100 and 200 µg/ml. The ability of PRF to promote T24

cell apoptosis was shown by flow cytometry in our previous study

(54). Here, morphological

examination revealed characteristic apoptotic features, including

early-stage membrane shrinkage and late-stage apoptotic body

formation. Notably, the absence of DNA laddering suggested that PRF

induced apoptosis via a non-canonical DNA fragmentation pathway.

Although no direct evidence currently demonstrates PRF-induced

apoptosis via this mechanism in other cancer cells, it is

hypothesized that negative DNA fragmentation results may contribute

to the underreporting of such findings. Consistent with this

observation, our team previously demonstrated flavonoid compounds

extracted from Galium verum L. likewise yield negative DNA

fragmentation results when inducing apoptosis in HepG2

hepatocellular carcinoma cells (unpublished data). The hypothesis

that PRF induces apoptosis through non-classical DNA fragmentation

pathways is based on the T24 cell model. To the best of our

knowledge, the present study is the first to report a non-canonical

DNA fragmentation route during PRF-induced apoptosis in T24

cells.

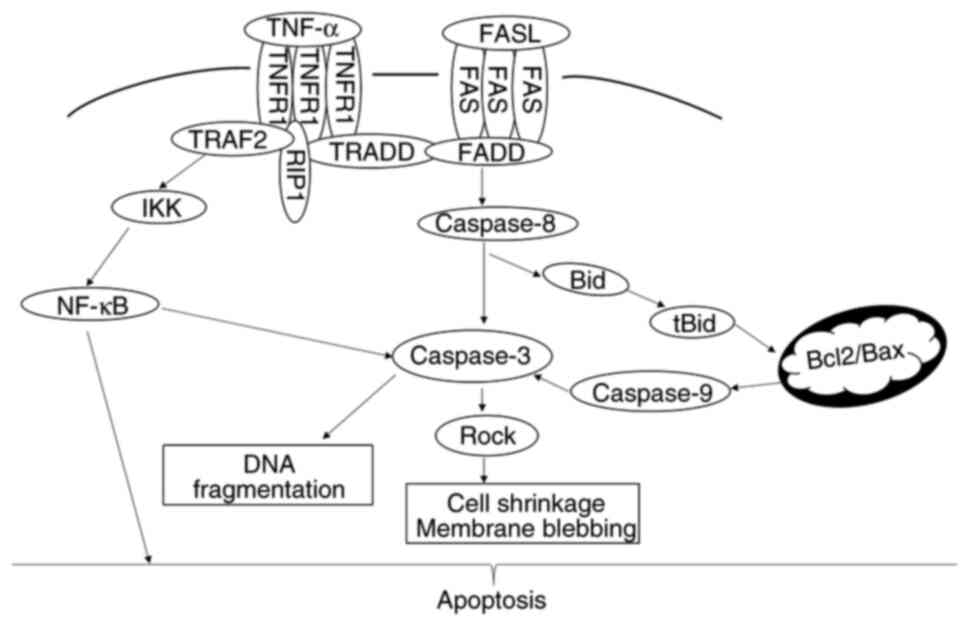

PRF treatment significantly upregulated FAS, FASL,

TNFR1, TNFα and CASP3 in T24 cells, while NF-κB was downregulated.

mRNA expression levels of both BCL2 and BAX remained unchanged,

indicating that PRF-mediated apoptosis in T24 cells may involve the

coordinated regulation of FAS, FASL, TNFR1, TNFα, CASP3 and NF-κB

expression dynamics (Fig. 6).

| Figure 6Mechanism of apoptosis. Apoptotic

signaling primarily occurs via two pathways: the extrinsic death

receptor pathway and the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway. In T24

cells, PRF induces apoptosis predominantly by activating FAS and

TNFR1, thereby initiating the death receptor pathway. This

ultimately leads to the activation of CASPASE3, resulting in

characteristic biochemical and morphological changes characteristic

of programmed cell death. Concurrently, NF-κB participates in the

regulation of this apoptotic pathway. TNFR, tumor necrosis factor

receptor; TRAF, TNFR-Associated Factor; TRADD, TNFR-associated

death domain; RIP, receptor-interacting protein; IKK, IκB kinase;

tBid, truncated Bid; PRF, Puerariae radix flavone. |

Binding of FASL to its receptor induces receptor

trimerization and activation (55,56).

Subsequently, activated FAS can recruit Fas-associated death domain

(FADD), which undergoes conformational changes that allow it to

bind and cleave procaspase-8, promoting the formation of the

death-inducing signaling complex (DISC). Within this complex,

activated caspase-8 propagates the apoptotic cascade via cleaving

and activating caspase-3 (55,56).

Here, the pronounced upregulation of FAS, FASL and CASP3,

accompanied by the increased intracellular FAS protein levels,

supported the activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway.

Protein expression levels of FAS were markedly decreased in cell

supernatant following treatment with PRF for 24 h, and

significantly elevated at 48 h. During early apoptosis, FAS

proteins may aggregate and bind to the plasma membrane, leading to

elevated intracellular FAS levels. In late apoptosis, loss of

plasma membrane integrity may facilitate the release of

membrane-bound FAS proteins into the culture medium in a soluble

form (57-59),

resulting in the observed increase in soluble FAS protein levels at

48 h.

DISC-associated caspase-8 can undergo

auto-proteolysis to activate caspase-8, which cleaves interacting

domain death agonist (Bid) into truncated (t)Bid (56,60).

tBid can translocate to mitochondria, thus perturbing the

equilibrium between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family

members (60-62).

However, the lack of alterations in the mRNA expression levels of

BCL2 and BAX indicated that the PRF-induced cell apoptosis may

occur independently of the mitochondrial pathway. Nandana et

al (50) confirmed that Brucein

D (a bioactive quassinoid compound isolated from Brucea

javanica fruit) induces apoptosis in T24 cells by regulating the

Bcl-2/Bax pathway, exhibiting the classical DNA ladder feature.

Conversely, the typical DNA laddering would not be expected in

apoptotic mechanisms independent of the Bcl-2/Bax pathway. This was

further reinforced by the absence of characteristic DNA ladder

fragmentation, supporting extrinsic apoptotic pathway

involvement.

In parallel with the FAS pathway, TNFα binding to

TNFR1 disrupts its interaction with the inhibitory protein silencer

of death domains, enabling the recruitment of TNF

receptor-associated death domain (TRADD) through the intracellular

death domain (63-67).

TRADD interacts with FADD, activating procaspase-8 to caspase-8,

which cleaves caspase-3. In the present study, the concurrent

upregulation of TNFR1, TNFα and CASP3 further supported the

involvement of this TNFα-driven apoptotic mechanism. In addition,

the significant elevation of the TNF-α protein expression

demonstrated that TNF-α may be involved in PRF-induced apoptosis in

BC cells.

TRADD recruits TNFR-associated factor 2 and

receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1, leading to

the activation of the IKK complex, which degrades IκB (63,64).

This process can promote the release of NF-κB, allowing its nuclear

translocation and the subsequent transcription of pro-survival

genes (63,64). Paradoxically, the present NF-κB

downregulation indicated that PRF may suppress this survival

signaling axis, thus shifting the cellular balance toward

apoptosis. Although this interaction may be indirect, the inverse

association between NF-κB suppression and caspase activation may

provide evidence for the pro-apoptotic effects of PRF.

NF-κB exhibits biphasic regulation (68). NF-κB upregulation promotes cellular

survival via transcription of pro-survival genes (63,64).

However, its pathological hyperactivation promotes tumor

progression and chemoresistance through the upregulation of

anti-apoptotic factors and activation of survival signaling

(69,70). By contrast, crosstalk between TNF-α

and FAS could promote the establishment of a compensatory apoptotic

axis by amplifying the activation of caspase-8 and -3, thus

counteracting NF-κB-mediated cytoprotection (71). In the present study, PRF led to a

biphasic modulation of NF-κB, which was characterized by transient

upregulation at 24 h followed by downregulation at 48 h. The

aforementioned finding was consistent with context-dependent

biphasic NF-κB regulation, implicating NF-κB in PRF-induced

apoptosis. These results indicated a dual role for NF-κB in T24

cells, acting as both a pro-survival mediator and a

stress-responsive modulator of apoptosis.

The present study had limitations. Firstly, the

antitumor effects of PRF were not validated through in vivo

animal experiments. Secondly, the findings were verified solely in

the T24 cell line without replication in other BC cell lines,

thereby restricting the generalizability of the conclusions.

Investigation of the mechanistic pathways lacked protein-level

validation by western blot analysis. Fourthly, no positive control

was included in the DNA ladder assay.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

PRF exhibited a significant inhibitory effect on the viability of

BC cells (T24 cell line). This inhibitory activity displayed a

time- and dose-dependent association, with more pronounced effects

observed at PRF concentrations of 100 and 200 µg/ml following

treatment for 24 and 48 h. Mechanistically, the results indicated

that the PRF-induced apoptosis was triggered by two mechanisms,

namely the death receptor-mediated pathways (FAS/TNFR1) in the

absence of mitochondrial pathways and the biphasic modulation of

NF-κB signaling, characterized by a switch from survival to

apoptosis. Overall, these findings highlighted the therapeutic

potential of PRF for the treatment of apoptosis-resistant BC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 82173568, 81703269,

81973097 and 82273687), the Natural Science Foundation of

Heilongjiang Province (grant no. LH2023H054), the Huoju Plan

Research Foundation of Mudanjiang Medical University (grant no.

2022-MYHJ-014), the Special Program for Supervisor Scientific

Research of Mudanjiang Medical University (grant nos. YJSZX2022137

and YJSZX2022141), the Administration of Science & Technology

Foundation of Mudanjiang (grant nos. HT2022NS112 and HT2022NS113),

the Scientific Research Project of the Health Commission of

Heilongjiang Province (grant no. 20221212060609) and the

Fundamental Research Funds for the Universities of Heilongjiang

Province (grant no. 2022-KYYWFMY-0712).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JD designed the study, analyzed and interpreted data

and wrote and revised the manuscript. YG and HG designed the study

and analyzed data. TJ and YM analyzed data and wrote the

manuscript. SR designed the study and wrote and revised the

manuscript. JD and SR confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Tran L, Xiao JF, Agarwal N, Duex JE and

Theodorescu D: Advances in bladder cancer biology and therapy. Nat

Rev Cancer. 21:104–121. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Katims AB, Tallman J, Vertosick E, Porwal

S, Dalbagni G, Cha EK, Smith R, Benfante N and Herr HW: Response to

2 induction courses of bacillus Calmette-Guèrin therapy among

patients with high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: 5-Year

follow-up of a phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 10:522–525.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Teoh JY, Kamat AM, Black PC, Grivas P,

Shariat SF and Babjuk M: Recurrence mechanisms of

non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer-a clinical perspective. Nat Rev

Urol. 19:280–294. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Knowles MA and Hurst CD: Molecular biology

of bladder cancer: New insights into pathogenesis and clinical

diversity. Nat Rev Cancer. 15:25–41. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Babjuk M, Böhle A, Burger M, Capoun O,

Cohen D, Compérat EM, Hernández V, Kaasinen E, Palou J, Rouprêt M,

et al: EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma

of the bladder: Update 2016. Eur Urol. 71:447–461. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Berdik C: Unlocking bladder cancer.

Nature. 551:S34–S35. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

James AC and Gore JL: The costs of

non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 40:261–269.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Abdollah F, Gandaglia G, Thuret R,

Schmitges J, Tian Z, Jeldres C, Passoni NM, Briganti A, Shariat SF,

Perrotte P, et al: Incidence, survival and mortality rates of

stage-specific bladder cancer in United States: A trend analysis.

Cancer Epidemiol. 37:219–225. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Witjes JA, Bruins HM, Cathomas R, Compérat

EM, Cowan NC, Gakis G, Hernández V, Linares Espinós E, Lorch A,

Neuzillet Y, et al: European association of urology guidelines on

muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: Summary of the 2020

guidelines. Eur Urol. 79:82–104. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wang Y, Chang Q and Li Y: Racial

differences in urinary bladder cancer in the United States. Sci

Rep. 8(12521)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Schinkel JK, Shao S, Zahm SH, McGlynn KA,

Shriver CD and Zhu K: Overall and recurrence-free survival among

black and white bladder cancer patients in an equal-access health

system. Cancer Epidemiol. 42:154–158. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kaye DR, Canner JK, Kates M, Schoenberg MP

and Bivalacqua TJ: Do African American patients treated with

radical cystectomy for bladder cancer have worse overall survival?

Accounting for pathologic staging and patient demographics beyond

race makes a difference. Bladder Cancer. 2:225–234. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Casey MF, Gross T, Wisnivesky J, Stensland

KD, Oh WK and Galsky MD: The impact of regionalization of

cystectomy on racial disparities in bladder cancer care. J Urol.

194:36–41. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Dobruch J, Daneshmand S, Fisch M, Lotan Y,

Noon AP, Resnick MJ, Shariat SF, Zlotta AR and Boorjian SA: Gender

and bladder cancer: A collaborative review of etiology, biology,

and outcomes. Eur Urol. 69:300–310. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Radkiewicz C, Edgren G, Johansson ALV,

Jahnson S, Häggström C, Akre O, Lambe M and Dickman PW: Sex

Differences in urothelial bladder cancer survival. Clin Genitourin

Cancer. 18:26–34.e6. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Babjuk M, Burger M, Compérat EM, Gontero

P, Mostafid AH, Palou J, van Rhijn BWG, Rouprêt M, Shariat SF,

Sylvester R, et al: European association of urology guidelines on

non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and carcinoma in

situ)-2019 update. Eur Urol. 76:639–657. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Messing EM, Tangen CM, Lerner SP,

Sahasrabudhe DM, Koppie TM, Wood DP Jr, Mack PC, Svatek RS, Evans

CP, Hafez KS, et al: Effect of intravesical instillation of

gemcitabine vs saline immediately following resection of suspected

low-grade non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer on tumor recurrence:

SWOG S0337 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 319:1880–1888.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Monro S, Colón KL, Yin H, Roque J III,

Konda P, Gujar S, Thummel RP, Lilge L, Cameron CG and McFarland SA:

Transition metal complexes and photodynamic therapy from a

tumor-centered approach: Challenges, opportunities, and highlights

from the development of TLD1433. Chem Rev. 119:797–828.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden APM and Lamm

DL: Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin reduces the risk of

progression in patients with superficial bladder cancer: A

meta-analysis of the published results of randomized clinical

trials. J Urol. 168:1964–1970. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crissman JD,

Montie JE, Gottesman JE, Lowe BA, Sarosdy MF, Bohl RD, Grossman HB,

Beck TM, et al: Maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy

for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell

carcinoma of the bladder: A randomized southwest oncology group

study. J Urol. 163:1124–1129. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hermans TJN, Voskuilen CS, van der Heijden

MS, Schmitz-Dräger BJ, Kassouf W, Seiler R, Kamat AM, Grivas P,

Kiltie AE, Black PC and van Rhijn BWG: Neoadjuvant treatment for

muscle-invasive bladder cancer: The past, the present, and the

future. Urol Oncol. 36:413–422. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Shi W, Yuan R, Chen X, Xin Q, Wang Y,

Shang X, Cong W and Chen K: Puerarin reduces blood pressure

in spontaneously hypertensive rats by targeting eNOS. Am J Chin

Med. 47:19–38. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Shukla R, Pandey N, Banerjee S and

Tripathi Y: Effect of extract of Pueraria tuberosa on

expression of hypoxia inducible factor-1α and vascular endothelial

growth factor in kidney of diabetic rats. Biomed Pharmacother.

93:276–285. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Satpathy S, Patra A, Ahirwar B and Hussain

MD: Antioxidant and anticancer activities of green synthesized

silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of tubers of

Pueraria tuberosa. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 46 (Suppl

3):S71–S85. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Jearapong N, Chatuphonprasert W and

Jarukamjorn K: Miroestrol, a phytoestrogen from Pueraria

mirifica, improves the antioxidation state in the livers and uteri

of β-naphthoflavone-treated mice. J Nat Med. 68:173–180.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Ahmad B, Khan S, Liu Y, Xue M, Nabi G,

Kumar S, Alshwmi M and Qarluq AW: Molecular mechanisms of

anticancer activities of Puerarin. Cancer Manag Res.

12:79–90. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Lin YJ, Hou YC, Lin CH, Hsu YA, Sheu JJ,

Lai CH, Chen BH, Lee Chao PD, Wan L and Tsai FJ: Puerariae

radix isoflavones and their metabolites inhibit growth and

induce apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 378:683–688. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zhang XL, Wang BB and Mo JS:

Puerarin 6''-O-xyloside possesses significant antitumor

activities on colon cancer through inducing apoptosis. Oncol Lett.

16:5557–5564. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Bulugonda RK, Kumar KA, Gangappa D, Beeda

H, Philip GH, Muralidhara Rao D and Faisal SM: Mangiferin from

Pueraria tuberosa reduces inflammation via inactivation of

NLRP3 inflammasome. Sci Rep. 7(42683)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Pandey N, Yadav D, Pandey V and Tripathi

VB: Anti-inflammatory effect of Pueraria tuberosa extracts

through improvement in activity of red blood cell anti-oxidant

enzymes. Ayu. 34:297–301. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Srivastava S, Pandey H, Singh SK and

Tripathi YB: Anti-oxidant, anti-apoptotic, anti-hypoxic and

anti-inflammatory conditions induced by PTY-2 against STZ-induced

stress in islets. Biosci Trends. 13:382–393. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Shukla R, Banerjee S and Tripathi YB:

Pueraria tuberosa extract inhibits iNOS and IL-6 through

suppression of PKC-α and NF-kB pathway in diabetes-induced

nephropathy. J Pharm Pharmacol. 70:1102–1112. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Jin SE, Son YK, Min BS, Jung HA and Choi

JS: Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of constituents

isolated from Pueraria lobata roots. Arch Pharm Res.

35:823–837. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kim JM, Lee YM, Lee GY, Jang DS, Bae KH

and Kim JS: Constituents of the roots of Pueraria lobata

inhibit formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Arch

Pharm Res. 29:821–825. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Sun Y, Zhang H, Cheng M, Cao S, Qiao M,

Zhang B, Ding L and Qiu F: New hepatoprotective isoflavone

glucosides from Pueraria lobata (Willd.) Ohwi. Nat Prod Res.

33:3485–3492. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Sook Kim Y, Soo Lee I and Sook Kim J:

Protective effects of Puerariae radix extract and its single

compounds on methylglyoxal-induced apoptosis in human retinal

pigment epithelial cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 152:594–598.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Sucontphunt A, De-Eknamkul W, Nimmannit U,

Dan Dimitrijevich S and Gracy RW: Protection of HT22 neuronal cells

against glutamate toxicity mediated by the antioxidant activity of

Pueraria candollei var. mirifica extracts. J Nat Med.

65:1–8. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Koirala P, Seong SH, Jung HA and Choi JS:

Comparative evaluation of the antioxidant and anti-Alzheimer's

disease potential of coumestrol and puerarol isolated from

Pueraria lobata using molecular modeling studies. Molecules.

23(785)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Anukulthanakorn K, Parhar IS, Jaroenporn

S, Kitahashi T, Watanbe G and Malaivijitnond S: Neurotherapeutic

effects of Pueraria mirifica extract in early- and

late-stage cognitive impaired rats. Phytother Res. 30:929–939.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Tiyasatkulkovit W, Malaivijitnond S,

Charoenphandhu N, Havill LM, Ford AL and VandeBerg JL:

Pueraria mirifica extract and Puerarin enhance

proliferation and expression of alkaline phosphatase and type I

collagen in primary baboon osteoblasts. Phytomedicine.

21:1498–1503. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Manonai J, Chittacharoen A, Udomsubpayakul

U, Theppisai H and Theppisai U: Effects and safety of

Pueraria mirifica on lipid profiles and biochemical markers

of bone turnover rates in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause.

15:530–535. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Wang Y, Wang WL, Xie WL, Li LZ, Sun J, Sun

WJ and Gong HY: Puerarin stimulates proliferation and

differentiation and protects against cell death in human

osteoblastic MG-63 cells via ER-dependent MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt

activation. Phytomedicine. 20:787–796. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Wang Y, Ma Y, Zheng Y, Song J, Yang X, Bi

C, Zhang D and Zhang Q: In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of

a novel Puerarin nanosuspension against colon cancer, with

high efficacy and low toxicity. Int J Pharm. 441:728–735.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Jia L, Hu Y, Yang G and Li P:

Puerarin suppresses cell growth and migration in

HPV-positive cervical cancer cells by inhibiting the PI3K/mTOR

signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med. 18:543–549. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Zhang WG, Liu XF, Meng KW and Hu SY:

Puerarin inhibits growth and induces apoptosis in SMMC-7721

hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Med Rep. 10:2752–2758.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Zhang WG, Yin XC, Liu XF, Meng KW, Tang K,

Huang FL, Xu G and Gao J: Puerarin induces hepatocellular

carcinoma cell apoptosis modulated by MAPK signaling pathways in a

dose-dependent manner. Anticancer Res. 37:4425–4431.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Hu Q, Xiang H, Shan J, Jiao Q, Lv S, Li L,

Li F, Ren D and Lou H: Two pairs of diastereoisomeric isoflavone

glucosides from the roots of Pueraria lobata. Fitoterapia.

144(104594)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Shi ZD, Hao L, Han XX, Wu ZX, Pang K, Dong

Y, Qin JX, Wang GY, Zhang XM, Xia T, et al: Targeting HNRNPU to

overcome cisplatin resistance in bladder cancer. Mol Cancer.

21(37)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Nandana PI, Rasyid H, Prihantono P,

Yustisia I, Hakim L, Bukhari A and Prasedya ES: Cytotoxicity and

apoptosis studies of brucein D against T24 bladder cancer cells.

Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 25:921–930. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Sun Y, Liu X, Tong H, Yin H, Li T, Zhu J,

Chen J, Wu L, Zhang X, Gou X and He W: SIRT1 promotes cisplatin

resistance in bladder cancer via beclin1 deacetylation-mediated

autophagy. Cancers (Basel). 16(125)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Mun JY, Baek SW, Jeong MS, Jang IH, Lee

SR, You JY, Kim JA, Yang GE, Choi YH, Kim TN, et al: Stepwise

molecular mechanisms responsible for chemoresistance in bladder

cancer cells. Cell Death Discov. 8(450)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Dong J, Guo Y, Ji T, Gao Q, Guan H, Niu Y,

Ma Y and Rong S: Effect of Puerariae radix flavones on mRNA

expression of N-myc downstream regulatory gene 1 in bladder cancer

cell line T24. J Environ Health. 41:941–943. 2024.(In Chinese).

|

|

55

|

Vanden Berghe T, Linkermann A,

Jouan-Lanhouet S, Walczak H and Vandenabeele P: Regulated necrosis:

The expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Biol. 15:135–147. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Lavrik IN and Krammer PH: Regulation of

CD95/Fas signaling at the DISC. Cell Death Differ. 19:36–41.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Peter ME and Krammer PH: The

CD95(APO-1/Fas) DISC and beyond. Cell Death Differ. 10:26–35.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Rehm M, Huber HJ, Dussmann H and Prehn JH:

Systems analysis of effector caspase activation and its control by

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein. EMBO J. 25:4338–4349.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Cheng J, Zhou T, Liu C, Shapiro JP, Brauer

MJ, Kiefer MC, Barr PJ and Mountz JD: Protection from Fas-mediated

apoptosis by a soluble form of the Fas molecule. Science.

263:1759–1762. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Kantari C and Walczak H: Caspase-8 and

bid: Caught in the act between death receptors and mitochondria.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1813:558–563. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Sartorius U, Schmitz I and Krammer PH:

Molecular mechanisms of death-receptor-mediated apoptosis.

Chembiochem. 2:20–29. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Kaufmann T, Strasser A and Jost PJ: Fas

death receptor signalling: Roles of Bid and XIAP. Cell Death

Differ. 19:42–50. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Li H and Lin X: Positive and negative

signaling components involved in TNFalpha-induced NF-kappaB

activation. Cytokine. 41:1–8. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Wajant H and Scheurich P: TNFR1-induced

activation of the classical NF-κB pathway. FEBS J. 278:862–876.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Karin M: Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer

development and progression. Nature. 441:431–436. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Luo JL, Tan W, Ricono JM, Korchynskyi O,

Zhang M, Gonias SL, Cheresh DA and Karin M: Nuclear

cytokine-activated IKKalpha controls prostate cancer metastasis by

repressing Maspin. Nature. 446:690–694. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Karin M and Lin A: NF-kappaB at the

crossroads of life and death. Nat Immunol. 3:221–227.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Ben-Neriah Y and Karin M: Inflammation

meets cancer, with NF-κB as the matchmaker. Nat Immunol.

12:715–723. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Baud V and Karin M: Is NF-kappaB a good

target for cancer therapy? Hopes and pitfalls. Nat Rev Drug Discov.

8:33–40. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Vazquez-Santillan K, Melendez-Zajgla J,

Jimenez-Hernandez L, Martínez-Ruiz G and Maldonado V: NF-κB

signaling in cancer stem cells: A promising therapeutic target?

Cell Oncol (Dordr). 38:327–339. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Cao X and Jin HM: Effects of Fas, NF-κB

and caspases on microvascular endothelial cell apoptosis induced by

TNFα. Chin J Pathophysiol. 8:15–18. 2001.(In Chinese).

|