Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common disease in

clinical practice. The average prevalence of OSA was 56% (1). Its prevalence may be high as 85% in

adults and elderly individuals. The prevalence of OSA may be varied

among countries with the highest prevalence in Mongolia (93%).

Untreated or unrecognized OSA may lead to several cardiovascular

diseases such as coronary artery disease or hypertension. The

prevalence of OSA in patients with these cardiovascular diseases

can be as high as 80% (2).

Additionally, OSA may result in several neuropsychological diseases

if left untreated including cognitive impairment, or depression

(3,4). Patients with OSA are at risk for

depression with odds ratio of 2.18 (95% confidence interval of

1.47, 2.88) by longitudinal studies (5).

Dizziness is a bothersome symptom and may cause by

several diseases such as hypertensive emergency (6,7). The

prevalence of dizziness in general population is ~30% (8-10).

Even though there are several causes of dizziness such as upper

respiratory tract infection, anemia, hypoglycemia, anxiety,

depression, postural hypotension, or hypertensive emergency, up to

80% of patients with dizziness are unexplained (11). One possible cause of dizziness OSA

reported by a national database from Korea (12). Patients with OSA had higher

incidence rate of dizziness than the non-OSA patients (149.86 vs.

23.88 per 10,000 individuals) with the incidence rate ratio of 6.28

(95% confidence interval of 4.89, 8.08). Even though the national

database study showed the positive correlation between OSA and

dizziness, there is limited data on risk factors of OSA in patients

with dizziness. The national database study provided only the

incidence and the correlation of both conditions. Additionally,

other causes of dizziness were not adjusted in the national

database study. A real-world study or pragmatic study can provide

the prevalence and risk factors of OSA in patients with dizziness.

Previously, two studies found that OSA was related with dizziness

(13,14). Being OSA had odds ratio of 1.69

(P=0.022) to be associated with OSA. However, both studies were

conducted by using the STOPBang questionnaire, not polysomnography.

Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the prevalence and

risk factors of OSA in patients with dizziness in real-world

clinical practice using home sleep apnea test.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted at

the outpatient department, University Hospital of Khon Kaen

University, Thailand. The inclusion criteria were adult patients

(aged ≥18 years) who had unexplained dizziness and underwent

overnight home sleep apnea test. Those who were pregnant or had

identifiable cause of dizziness such as upper respiratory tract

infection, anemia, hypoglycemia, anxiety, depression, postural

hypotension, or hypertensive emergency were excluded. These

excluded conditions were recorded from medical charts or history

taking. The study period was between November 2022 and November

2024.

Eligible patients were evaluated for OSA by baseline

characteristics, comorbidities, STOPBang score (15), and physical examination. The

overnight home sleep apnea test (Alice PDX®, Phillips

Respironics) was performed in all eligible patients. Overnight home

sleep apnea test comprised of nasal pressure transducer, pulse

oximeter, and chest belt to record chest movement body position

(16). The total sleep time for

overnight sleep apnea test was at least 4 h. Sleep tracings were

scored manually for apnea and hypopnea based on the criteria of

AASM (17). The device had

agreement with in-laboratory polysomnography of 96.4% (18). Diagnosis of OSA was made if an

apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was five or more events/h.

Sample size calculation

The previous study reported that the incidence of

OSA in patients with dizziness by the national database study was

7.78% (12). The estimated

prevalence of OSA in patients with dizziness in clinical practice

was higher at 20% as previously reported (14). Based on the power of 80% and

confidence of 95%, the required sample size was 50 subjects.

Statistical analyses

Prevalence of OSA in patients with dizziness was

calculated. Patients were categorized into two groups: With and

without OSA. Results of studied variables of both groups were

reported as the mean (SD) or median (interquartile range) for

numerical variables according to normal distribution of studied

variables. For normally distributed variables, mean ± SD was

reported, while median (interquartile range) was reported for not

normally distributed variables. Number (proportion) was shown for

categorical variables. The differences of each studied variable

between the OSA and non-OSA group were computed by inferential

statistics. For numerical variables, the student t test or Wilcoxon

rank sum test was used to compare the differences between both

groups for normally distributed variables and non-normally

distributed variables, respectively. Fisher-Exact test was used to

compare the differences between two proportions.

Predictors OSA in patients with dizziness were

executed by stepwise method of multivariable logistic regression

analysis. Studied variables were computed for a P-value by

univariable logistic regression analysis. Those with P<0.20 or

clinically significant were included in the stepwise, multivariable

logistic regression analysis (19,20).

The model was tested for a goodness of fit by the Hosmer-Lemeshow

method. A P-value by the Hosmer-Lemeshow Chi square of more than

0.05 indicated a goodness of fit. A numerical predictor for being

OSA was computed for appropriate diagnostic cut off point by a

receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Sensitivity and

specificity for the best cut-off point for OSA diagnosis were

reported. Studied variables with missing data of more than 50% were

not included in the analysis (21).

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA software

version 10.1 (StataCorp LP).

Results

During the study period, there were 81 patients met

the study criteria. Of those, 76 patients (93.83%) had OSA with a

median AHI of 23 events/h (IQR of 11.5-33.5), while the non-OSA

group had a median AHI of 4 events/h (IQR 3.9-4.0). Regarding

baseline characteristics, comorbidities and symptoms of OSA

(Table I), STOPBang score was

significantly different between both groups. The OSA group had

higher average of STOPBang score than the non-OSA group (3.95 vs.

2.40; P=0.026). The proportion of atrial fibrillation was

significantly higher in the non-OSA group than the OSA group (20.00

vs. 0%; P=0.005). For physical signs, the OSA group had significant

larger neck circumference than the non-OSA group: 37.63 vs. 33.25

cm (P=0.029) as shown in Table

II.

| Table IBaseline characteristics,

comorbidities, and symptoms of patients with unexplained dizziness

categorized by presence of OSA. |

Table I

Baseline characteristics,

comorbidities, and symptoms of patients with unexplained dizziness

categorized by presence of OSA.

| Factors | Non-OSA (n=5) | OSA (n=76) | P-value |

|---|

| Mean (SD) age,

years | 59.00

(52.0-61.0) | 59.00

(47.5-65.0) | 0.523 |

| Male sex | 1 (20.0) | 33 (44.0) | 0.293 |

| Comorbidities | | | |

|

Hypertension | 2 (40.0) | 42 (56.8) | 0.465 |

|

Diabetes | 0 (0.0) | 18 (25.0) | 0.200 |

|

Coronary

artery disease | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.0) | 0.646 |

|

Atrial

fibrillation | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.005 |

|

Heart

failure | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.7) | 0.710 |

|

Allergic

rhinitis | 0 (0.0) | 11 (14.8) | 0.353 |

| Symptoms | | | |

|

Snoring | 2 (40.0) | 57 (76.0) | 0.076 |

|

Stop

breathing | 0 (0.0) | 25 (33.3) | 0.119 |

|

Fatigue | 3 (60.0) | 35 (46.7) | 0.563 |

|

Dyspnea | 2 (40.0) | 13 (17.3) | 0.209 |

|

GERD | 2 (40.0) | 34 (45.3) | 0.855 |

|

Nocturia | 3 (60.0) | 56 (75.7) | 0.435 |

|

Light

sleeper | 3 (60.0) | 44 (58.7) | 0.953 |

|

Dizziness | 5 (100.0) | 100 (100.0) | 0.712 |

|

Sleepiness | 2 (40.0) | 49 (66.2) | 0.507 |

| Mean (SD)

STOPBANG | 2.40±1.52 | 3.95±1.48 | 0.026 |

| Table IIPhysical signs of patients with

unexplained dizziness categorized by presence of OSA. |

Table II

Physical signs of patients with

unexplained dizziness categorized by presence of OSA.

| Factors | Non-OSA (n=5) | OSA (n=76) | P-value |

|---|

| Body mass index,

kg/m2 | 21.40

(16.80-25.65) | 26.75

(23.60-30.85) | 0.057 |

| Systolic blood

pressure, mmHg | 124.20±8.84 | 130.43±1.58 | 0.342 |

| Diastolic blood

pressure, mmHg | 73.00±4.66 | 74.32±1.21 | 0.786 |

| Neck circumference,

cm | 33.25±2.18 | 37.63±0.48 | 0.042 |

| Retrognathia | 1 (20.0) | 20 (27.4) | 0.718 |

| Torus

palatinus | 2 (40.0) | 19 (25.7) | 0.483 |

| Torus

mandibularis | 2 (40.0) | 15 (20.0) | 0.029 |

| Macroglossia | 1 (20.0) | 45 (60.8) | 0.073 |

| Friedman

classification | | | 0.059 |

|

1 | 0 (0.0) | 11 (14.9) | |

|

2 | 0 (0.0) | 14 (18.9) | |

|

3 | 4 (80.0) | 18 (24.3) | |

|

4 | 1 (20.0) | 31 (41.9) | |

|

Denture | 0 (0.0) | 12 (16.4) | 0.324 |

|

Tonsillectomy | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

|

Thyromegaly | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

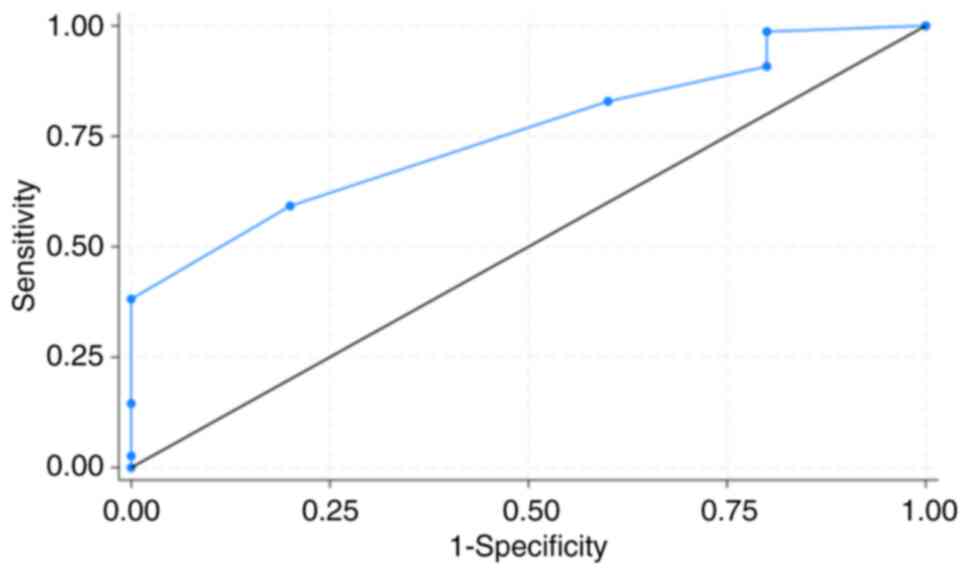

There were seven factors included in the predictive

model for OSA: Age, sex, snoring, nocturia, gastroesophageal reflux

disease, diabetes and STOPBang score. There were four factors

remaining in the model by stepwise logistic regression analysis

(Table III). Only STOPBang score

was independently associated with OSA with an adjusted odds ratio

of 2.115 (95% confidence interval of 1.048, 4.268). The

Hosmer-Lemeshow Chi square of the model was 3.24 (P=0.919)

indicating a goodness of fit of the model. The cut point of

STOPBang score of 3 or over had sensitivity of 82.89% and

specificity of 40.00% for OSA. The area under ROC curve of STOPBang

score on OSA was 75.39% (95% confidence interval of 57.50-93.29%)

as shown in Fig. 1.

| Table IIIFactors predictive of obstructive

sleep apnea by multivariable logistic regression analysis in

patients with unexplained dizziness. |

Table III

Factors predictive of obstructive

sleep apnea by multivariable logistic regression analysis in

patients with unexplained dizziness.

| Factors | Unadjusted odds

ratio (95% confidence interval) | Adjusted odds ratio

(95% confidence interval) |

|---|

| STOPBang | 1.798 (0.982,

3.293) | 2.115 (1.048,

4.268) |

| Dyspnea | 0.314 (0.047,

2.074) | 0.127 (0.012,

1.243) |

| Nocturia | 2.074 (0.320,

13.408) | 2.609 (0.312,

21.779) |

| Torus

mandibularis | 0.375 (0.057,

2.449) | 0.383 (0.046,

3.170) |

Discussion

The present study showed that the prevalence of OSA

in patients with unexplained dizziness was notably high at 93.83%.

This prevalence was markedly higher than the previous national

study at 7.76% (12). This high

prevalence of OSA in the present study may be due to the different

study population from the previous study. The current study

enrolled only patients with unexplained dizziness, while the

national database study may enroll patients with dizziness from any

causes. These differences in study population may result in

different prevalence of OSA in patients with dizziness. A previous

study found that psychogenic dizziness or other causes of dizziness

were closely related to poor sleep (22). Both psychogenic dizziness and other

causes of dizziness had coefficients of 1.820 (P<0.05) and2.262

(P<0.01) to Pittsburg sleep quality index (PSQI), while only

other causes of dizziness were related to insomnia severity index

with a coefficient of 3.237 (P<0.05). These results showed poor

sleep quality and insomnia were found in these two types of

dizziness. Those with psychogenic and other causes of dizziness may

be similar to those with unexplained dizziness in the present

study. OSA is a condition leading to poor sleep quality and

insomnia. Patients with OSA had higher global score of PSQI than

those without OSA (8.62 vs. 5.36; P<0.001) as well as the C1

subscore of sleep quality (1.7 vs. 0.79; P<0.001) (23). Additionally, up to 50% of patients

with OSA reported symptoms of insomnia (24,25).

These data showed a close relationship between OSA and dizziness.

Even though the exact mechanisms of OSA associated with dizziness

remain unclear, there are several proposed mechanisms (13,26,27).

These mechanisms included brainstem and cerebellar damage,

imbalance of autonomic function, white matter damage, and

hippocampal degeneration in the areas associated with vestibular

function. These abnormalities were associated with intermittent

hypoxemia from OSA.

Among several studied variables, only STOPBang score

was a predictor of OSA in patients with unexplained dizziness. As

previously reported, the STOPBang score was a sensitive screening

tool for OSA in various settings across the world (15,28).

According to the adjusted odds ratio of 2.115 in the present study,

this finding may indicate moderate effect (29) of the STOPBang score as a screening

tool for OSA in patients with unexplained dizziness in clinical

setting of outpatient department. A systematic review showed that

STOPBang score of 3 or more had sensitivity of 91.4% to detect OSA

(28). Originally, the STOPBang was

used to screen for OSA in patients with perioperative setting.

Several studies showed that the STOPBang score can be used for OSA

detection in patients underwent bariatric surgery, or obese

patients (30-32).

Most studies found that the STOPBang score of 3 or more associated

with OSA as in the present study with patients with unexplained

dizziness (13,27). The original study for STOPBang score

in patients underwent surgery had sensitivity of 72%, while another

study showed the sensitivity of 87.9% in OSA detection with the

STOPBang questionnaire in obese patients. Similarly, the present

study showed the STOPBang score of 3 for OSA detection had

comparable sensitivity of 82.89% (Fig.

1). Note that low specificity of the STOPBang score of 40% may

result in false positive issue.

There are certain limitations to the present study.

First, the results may apply to only those without causes of

dizziness. Even though STOPBang was the statistically significant

factor, clinical significance was not evaluated in the present

study (33). As the outcome was the

diagnosis of OSA, not the effectiveness or efficacy of treatment

modality, clinical significance may not be able to be evaluated.

Second, no intervention such as a continuous positive airway

pressure machine was applied to the patients. Further studies to

evaluate CPAP treatment effects on dizziness as a treatment option.

Finally, the predictive model comprised only baseline clinical

parameter; no laboratory tests were included. Further cohort

studies including patients with other causes of dizziness with

laboratory tests may advance the knowledge provided by the current

study.

In conclusion, OSA was markedly prevalent in

patients with unexplained dizziness. The STOPBang questionnaire may

be used as a screening tool to detect OSA in this setting with high

sensitivity.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

NL, SK and KS conceived and designed the study. SS

collected data and interpreted data. WB interpreted data. KS

performed statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript. NL, SK and KS confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study protocol was approved (approval no.

HE641504) by the ethics committee in human research of Khon Kaen

University (Khon Kaen, Thailand) and all methods were conducted

following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The

requirement for informed consent was waived due to the

retrospective nature of the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

de Araujo Dantas AB, Gonçalves FM, Martins

AA, Alves GÂ, Stechman-Neto J, Corrêa CC, Santos RS, Nascimento WV,

de Araujo CM and Taveira KVM: Worldwide prevalence and associated

risk factors of obstructive sleep apnea: A meta-analysis and

meta-regression. Sleep Breath. 27:2083–2109. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Yeghiazarians Y, Jneid H, Tietjens JR,

Redline S, Brown DL, El-Sherif N, Mehra R, Bozkurt B, Ndumele CE

and Somers VK: Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease:

A scientific statement from the american heart association.

Circulation. 144:e56–e67. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Chang WP, Liu ME, Chang WC, Yang AC, Ku

YC, Pai JT, Huang HL and Tsai SJ: Sleep apnea and the risk of

dementia: A population-based 5-year follow-up study in Taiwan. PLoS

One. 8(e78655)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lajoie AC, Lafontaine AL, Kimoff RJ and

Kaminska M: Obstructive sleep apnea in neurodegenerative disorders:

Current evidence in support of benefit from sleep apnea treatment.

J Clin Med. 9(297)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Edwards C, Almeida OP and Ford AH:

Obstructive sleep apnea and depression: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Maturitas. 142:45–54. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Alsharif A, Aljohani A, Ashour S, Zahim A

and Alsulimani L: Clinical outcomes of discharged patients with

high blood pressure in the emergency department. Cureus.

16(e76654)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Newman-Toker DE, Dy FJ, Stanton VA, Zee

DS, Calkins H and Robinson KA: How often is dizziness from primary

cardiovascular disease true vertigo? A systematic review. J Gen

Intern Med. 23:2087–2094. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Chan Y: Differential diagnosis of

dizziness. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 17:200–203.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Karatas M: Central vertigo and dizziness:

Epidemiology, differential diagnosis, and common causes.

Neurologist. 14:355–364. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Lasisi AO and Gureje O: Prevalence and

correlates of dizziness in the Ibadan Study of Ageing. Ear Nose

Throat J. 93:E37–E44. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

van Leeuwen RB, Schermer TR and Bienfait

HP: The relationship between dizziness and sleep: A review of the

literature. Front Neurol. 15(1443827)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Byun H, Chung JH, Jeong JH, Ryu J and Lee

SH: Incidence of peripheral vestibular disorders in individuals

with obstructive sleep apnea. J Vestib Res. 32:155–162.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kim E, Lee M and Park I: Risk of

obstructive sleep apnea, chronic dizziness, and sleep duration.

Nurs Res. 73:313–319. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Maas BDPJ, Bruintjes TD, van der

Zaag-Loonen HJ and van Leeuwen RB: The relation between dizziness

and suspected obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol.

277:1537–1543. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chung F, Abdullah HR and Liao P: STOP-bang

questionnaire: A practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep

apnea. Chest. 149:631–638. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Tran-Thi BT, Quach-Thieu M, Le-Tran BN,

Nguyen-Duc D, Tran-Hiep N, Nguyen-Thi T, Nguyen-Ngoc YL,

Nguyen-Tuan A, Tang-Thi-Thao T, Nguyen-Van T and Duong-Quy S: Study

of the agreement of the apnea-hypopnea index measured

simultaneously by pressure transducer via respiratory polygraphy

and by thermistor via polysomnography in real time with the same

individuals. J Otorhinolaryngol Hear Balance Med. 3(4)2022.

|

|

17

|

Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo C, Harding SM,

Lloyd RM, Quan SF, Troester MT and Vaughn BV: AASM scoring manual

updates for 2017 (version 2.4). J Clin Sleep Med. 13:665–666.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Nilius G, Domanski U, Schroeder M, Franke

KJ, Hogrebe A, Margarit L, Stoica M and d'Ortho MP: A randomized

controlled trial to validate the Alice PDX ambulatory device. Nat

Sci Sleep. 9:171–180. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Mickey RM and Greenland S: The impact of

confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol.

129:125–137. 1989.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Sun GW, Shook TL and Kay GL: Inappropriate

use of bivariable analysis to screen risk factors for use in

multivariable analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 49:907–916.

1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Madley-Dowd P, Hughes R, Tilling K and

Heron J: The proportion of missing data should not be used to guide

decisions on multiple imputation. J Clin Epidemiol. 110:63–73.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Kim SK, Kim JH, Jeon SS and Hong SM:

Relationship between sleep quality and dizziness. PLoS One.

13(e0192705)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Lusic Kalcina L, Valic M, Pecotic R,

Pavlinac Dodig I and Dogas Z: Good and poor sleepers among OSA

patients: Sleep quality and overnight polysomnography findings.

Neurol Sci. 38:1299–1306. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Mendes MS and dos Santos JM: Insomnia as

an expression of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome-the effect of

treatment with nocturnal ventilatory support. Rev Port Pneumol

(2006). 21:203–208. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Wickwire EM and Collop NA: Insomnia and

sleep-related breathing disorders. Chest. 137:1449–1463.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Torabi-Nami M, Mehrabi S, Borhani-Haghighi

A and Derman S: Withstanding the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

at the expense of arousal instability, altered cerebral

autoregulation and neurocognitive decline. J Integr Neurosci.

14:169–193. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Akiyama N, Suzuki Y, Tanaka T, Ito H and

Ichibayashi R: Obstructive sleep apnea as a hidden cause of

dizziness: A report of two non-obese patients. Cureus.

17(e84779)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Pivetta B, Chen L, Nagappa M, Saripella A,

Waseem R, Englesakis M and Chung F: Use and Performance of the

STOP-Bang Questionnaire for Obstructive Sleep Apnea Screening

Across Geographic Regions: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

JAMA Netw Open. 4(e211009)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Chen H, Cohen P and Chen S: How big is a

big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in

epidemiological studies. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 39:860–864.

2010.

|

|

30

|

Matarredona-Quiles S, Carrasco-Llatas M,

Martínez-Ruíz de Apodaca P, Díez-Ares JÁ, González-Turienzo E and

Dalmau-Galofre J: Analysis of possible predictors of moderate and

severe obstructive sleep apnea in obese patients. Indian J

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 76:5126–5132. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Turbati MS, Kindel TL and Higgins RM:

Identifying the optimal STOP-Bang screening score for obstructive

sleep apnea among bariatric surgery patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis.

20:1154–1162. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Mergen H, Altındağ B, Zeren Uçar Z and

Karasu Kılıçaslan I: The predictive performance of the STOP-bang

questionnaire in obstructive sleep apnea screening of obese

population at sleep clinical setting. Cureus.

11(e6498)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Sharma H: Statistical significance or

clinical significance? A researcher's dilemma for appropriate

interpretation of research results. Saudi J Anaesth. 15:431–434.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|