Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second leading cause of

cancer-associated mortalities worldwide and the most commonly

diagnosed cancer among men in 2025(1). Despite its high prevalence,

prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing remains the most widely

used screening method due to its cost-effectiveness and

practicality (2). However, numerous

studies demonstrate that PSA levels can be influenced by various

non-cancer-associated factors, including benign prostatic

hyperplasia (3), prostatitis

(4), antibiotic use (5) and body mass index (BMI) (6). These confounding factors can lead to

diagnostic inaccuracies, increasing the risk of a false-positive or

-negative diagnosis, which may result in unnecessary or

inappropriate treatment (7).

Therefore, relying solely on PSA levels for the screening of PCa

presents notable challenges that warrant further investigation and

improvement (8).

Growing evidence suggests that immune inflammation

and nutritional status serve critical roles in the development and

progression of PCa (9,10). A previous study reveals a potential

association between abnormal immune-inflammatory responses,

nutritional imbalances and elevated serum PSA levels in men

(11). C-reactive protein (CRP), an

acute-phase reactant with levels that increase in response to acute

inflammation, infection or tissue damage, is linked to poor

clinical outcomes in patients with PCa (12). For example, a previous meta-analysis

demonstrates that increased CRP levels are notably associated with

a reduced overall survival (OS), cancer-specific survival and

progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with PCa (13). The systemic immune-inflammation

index (SII), which is calculated as: (Platelets x

neutrophils)/lymphocytes, serves as a simple yet effective

prognostic biomarker. Elevated pre-treatment SII values are

associated with reduced OS and PFS outcomes in patients with PCa

(14). Compared with normal

tissues, the levels of tumor necrosis factor are increased in

various tumors and are associated with inflammatory cell

infiltration and increased vascularization within the tumor

microenvironment (15). Other

inflammatory markers, such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

(NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), may also help

differentiate benign prostatic hyperplasia from PCa and serve as

potential diagnostic tools (16-18).

Serum albumin, a readily available and cost-effective indicator of

nutritional status, is also linked to PSA levels. It is reported

that lower serum albumin levels in middle-aged men are associated

with higher PSA concentrations (19). However, a cross-sectional analysis

reveals that a dietary protein intake of >181.8 g/day is

positively associated with elevated PSA levels (20).

Previous studies report associations between

individual inflammatory or nutritional markers (such as CRP,

albumin and NLR) and the PSA levels or prognosis of PCa (21-24).

However, to the best of our knowledge, the CRP-albumin-lymphocyte

(CALLY) index, a composite score integrating inflammation (such as

the CRP levels), nutritional status (such as the albumin levels)

and immunity (such as the lymphocyte count), is yet to be evaluated

in association with the PSA levels in a general population without

PCa (25). Previous retrospective

studies demonstrate that the CALLY index is an independent

prognostic factor of OS and PFS in various types of cancer,

including gastric (26),

non-small-cell lung (27),

colorectal cancer (28) and

hepatocellular carcinoma (29).

However, previous research on the association between the CALLY

index and PCa is limited. Accurate interpretation of PSA values,

accounting for potential confounding effects from subclinical

inflammation and nutritional status, is essential to increase the

reliability of the screening for PCa.

Therefore, using data from the 2003-2010 national

health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) cycles, the

present study investigated the association between the CALLY index

and the PSA levels in a population of American men aged ≥40 years

without known prostate conditions.

Subjects and methods

Study description and population

A NHANES (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/) is a cross-sectional

study designed to assess the health and nutritional status of

adults and children in the United States of America and is

stipulated by a Code of Federal Regulations (45 CFR 46.101). It is

conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), a

part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

(30). All NHANES protocols were

approved by the NCHS research ethics review board, and written

informed consent was obtained from all participants. The present

study received an exemption of ethics approval from the Huai'an No.

1 People's Hospital institutional review board. The present study

involved a secondary analysis of NHANES data and adhered to the

reporting guidelines outlined in the strengthening the reporting of

observational studies in epidemiology statement for cross-sectional

studies.

The present study used data from four NHANES cycles

between 2003-2010 (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/default.aspx?BeginYear=2003;

https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/default.aspx?BeginYear=2005;

https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/default.aspx?BeginYear=2007;

https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/default.aspx?BeginYear=2009),

as these were the only cycles that included comprehensive PSA

information. Participants were included if there was complete data

for PSA and all components of the CALLY index. The following

exclusion criteria were applied: i) Age, <40 years; ii) missing

data for PSA, CRP, albumin or lymphocyte counts; iii) missing

information regarding BMI, comorbidities, lifestyle factors or

education level; iv) conditions or treatments known to affect PSA

levels, including the use of 5-α reductase inhibitors, diagnosis of

benign prostatic hyperplasia or prostatitis, prostate biopsy within

the past week, urological surgery within the past month, or the

diagnosis of PCa.

Definitions of PSA and the CALLY

index

Serum samples were stored at 2-8˚C and analyzed by

Collaborative Laboratory Services LLC. Total PSA concentrations

were measured using the Hybritech method (31) and validated using a chemiluminescent

immunoassay platform with the Beckman Access®

Immunoassay System (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Testing was carried out

according to standardized NHANES protocols (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about/erb.html).

Each sample was analyzed once without replication. Rigorous quality

control procedures, including internal calibration and commercial

controls (bench quality controls; https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/public/2009/labmethods/PSA_F_met_complex.pdf),

were carried out to ensure measurement accuracy. PSA concentrations

were reported in ng/ml. A total of 5,320 serum samples from men

aged ≥40 years were included in the final analysis.

The CALLY index was calculated using the following

formula: CALLY index=[albumin concentration (g/l) x lymphocyte

count (109/l)]/[CRP concentration (mg/l) x 10]. CRP

concentrations were quantified using latex-enhanced nephelometry on

a Behring Nephelometer (Siemens Healthineers). Lymphocyte counts

were analyzed using the Beckman Coulter MAXM Instrument. Serum

albumin levels were measured using the Beckman Synchron LX20 and

Beckman UniCel DxC800 Synchron systems. Due to the skewed

distribution of the CALLY index, a logarithmic transformation was

applied prior to statistical analyses.

Covariates

A range of covariates that could influence the

association between the CALLY index and PSA levels were included in

the analysis. These covariates included demographic characteristics

(such as age, ethnicity, education level, BMI, smoking status and

alcohol consumption), laboratory indices [such as the levels of

blood urea nitrogen (mmol/l), cholesterol (mg/dl), glucose (mg/dl),

serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; U/l), total bilirubin (mg/dl),

triglycerides (mmol/l), serum uric acid (mg/dl), serum creatinine

(mg/dl), aspartate aminotransferase (U/l) and alanine

aminotransferase (U/l)] and clinical history (such as the presence

or absence of chronic diseases including hypertension, diabetes,

coronary artery disease, angina pectoris and history of neoplastic

diseases).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using R

version 4.3 (https://www.r-project.org) and EmpowerStats version

2.0 (http://www.empowerstats.net/en/),

incorporating the complex sampling design of NHANES in accordance

with CDC analytical guidelines. Participants were stratified into

quartiles based on their CALLY index values: Q1, <1.91; Q2,

1.91-4.27; Q3, 4.28-9.68; and Q4, >9.68. Continuous variables

are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, while categorical

variables are presented as counts and percentages. Differences

between groups across CALLY quartiles were analyzed using one-way

analysis of variance with Tukey's honestly significant difference

post hoc test for continuous variables and Pearson's chi-square

test for categorical variables.

To investigate the association between the CALLY

index and PSA levels, both weighted univariate and multivariate

linear regression models were used, with β coefficients (β) and 95%

confidence intervals (CIs) reported. Three models were constructed:

i) Model 1 was unadjusted; ii) model 2 was adjusted for age,

ethnicity and BMI; and iii) model 3 was fully adjusted for a

comprehensive set of covariates selected based on biological

plausibility, prior literature and data availability in NHANES

(32). These variables may affect

the PSA levels and/or components of the CALLY index, including

comorbidities (such as the presence or absence of hypertension,

diabetes, coronary heart disease, angina, tumor history and BMI),

lifestyle factors (such as smoking status, alcohol intake, age,

ethnicity and level of education) and laboratory markers [such as

the levels of CRP, albumin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT),

aspartate aminotransferase (AST), cholesterol, bilirubin,

triglycerides, monocytes, neutrophils, platelets, creatinine, LDH,

uric acid and glucose]. Variables such as globulin, testosterone

and physical activity were not included due to incomplete data,

limited availability across NHANES cycles and lack of consistent

associations with PSA or CALLY components in the population without

cancer.

To investigate potential non-linear associations,

restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression was used. Additionally,

subgroup analyses were conducted to assess whether the association

between the CALLY index and PSA varied by demographic or clinical

characteristics. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics of

participants

The present study initially included 41,156

participants. However, a number of participants were excluded due

to incomplete information on key variables. Specifically,

exclusions were made due to missing data regarding PSA levels

(n=35,138), factors known to influence PSA levels (n=232), albumin

levels (n=11), CRP levels (n=1), lymphocyte counts (n=29), BMI

(n=86), chronic health conditions or tumor history (n=21),

education level (n=1) and alcohol consumption history (n=265).

After applying these criteria, a total of 5,320 eligible

participants were included in the final analysis. The mean age of

participants was 59.44±12.51 years. Participants were divided into

quartiles based on their CALLY index values (Q1-Q4, Table I). The mean total serum PSA level

was 1.82±3.20, with a statistically significant decreasing trend

observed across increasing CALLY quartiles. Compared with

participants with low CALLY index values, those with increased

values tended to be younger and had lower levels of blood glucose,

uric acid, LDH, creatinine, globulin and BMI as well as reduced

counts of monocytes, neutrophils and platelets. Additionally,

compared with participants with low CALLY index values, those with

increased values were associated with a reduced prevalence of

hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, history of cancer

and cigarette smoking. However, no significant differences were

observed in the levels of ALT, AST, alcohol consumption or

incidence of angina.

| Table IBaseline characteristics of

participants sorted by CALLY index quartiles (n=5,320). |

Table I

Baseline characteristics of

participants sorted by CALLY index quartiles (n=5,320).

| | CALLY index

quartiles | |

|---|

| Variables | Total

(n=5,320) | 1 (n=1,330) | 2 (n=1,330) | 3 (n=1,328) | 4 (n=1,332) | Statistic | P-value |

|---|

| ALTa | 28.61±20.66 | 27.63±29.14 | 29.15±18.23 | 29.40±17.38 | 28.25±14.92 | F=2.07 | 0.102 |

| ASTa | 28.02±15.39 | 28.19±19.94 | 28.03±14.49 | 27.78±12.65 | 28.10±13.42 | F=0.17 | 0.916 |

|

Cholesterola | 5.13±1.10 | 5.00±1.11 | 5.16±1.13 | 5.23±1.10 | 5.12±1.04 | F=10.13 | <0.001 |

|

Glucosea | 5.98±2.31 | 6.41±2.78 | 6.02±2.39 | 5.79±1.95 | 5.71±1.94 | F=24.86 | <0.001 |

| Lactate

dehydrogenasea | 133.87±33.42 | 139.33±45.50 | 134.20±31.79 | 132.10±26.05 | 129.84±25.73 | F=19.68 | <0.001 |

|

Bilirubina | 14.25±5.21 | 13.65±5.28 | 14.11±5.04 | 14.49±5.34 | 14.76±5.10 | F=11.61 | <0.001 |

|

Triglyceridesa | 1.95±1.49 | 1.82±1.24 | 2.06±1.57 | 2.04±1.64 | 1.87±1.47 | F=8.31 | <0.001 |

| Uric

acida | 362.14±80.04 | 378.38±91.79 | 369.99±77.30 | 356.53±72.61 | 343.72±72.57 | F=49.52 | <0.001 |

|

Creatininea | 94.10±48.59 | 101.14±65.41 | 94.58±42.21 | 90.45±34.83 | 90.22±45.77 | F=14.81 | <0.001 |

|

Globulina | 29.36±4.97 | 31.29±5.82 | 29.38±4.64 | 28.84±4.39 | 27.92±4.26 | F=116.29 | <0.001 |

| PSAa | 1.82±3.20 | 2.10±3.97 | 1.93±3.29 | 1.64±2.64 | 1.62±2.73 | F=7.14 | <0.001 |

|

Monocytea | 0.58±0.20 | 0.60±0.23 | 0.58±0.19 | 0.57±0.18 | 0.56±0.21 | F=13.29 | <0.001 |

|

Neutrophila | 4.30±2.14 | 4.85±2.87 | 4.37±2.31 | 4.14±1.52 | 3.83±1.38 | F=55.64 | <0.001 |

| Age,

yearsa | 59.44±12.51 | 62.37±12.54 | 59.98±12.52 | 58.20±12.29 | 57.20±12.07 | F=44.97 | <0.001 |

|

Plateleta | 238.90±63.85 | 246.41±75.68 | 238.10±58.52 | 237.64±61.65 | 233.48±57.26 | F=9.62 | <0.001 |

| BMIa | 28.87±5.68 | 30.49±7.08 | 29.69±5.35 | 28.53±4.92 | 26.77±4.29 | F=114.48 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity, N

(%) | | | | | | χ²=42.50 | <0.001 |

|

Non-Hispanic

White | 935 (17.58) | 192 (14.44) | 247 (18.57) | 255 (19.20) | 241 (18.09) | | |

|

Non-Hispanic

Black | 342 (6.43) | 67 (5.04) | 92 (6.92) | 96 (7.23) | 87 (6.53) | | |

|

Mexican

American | 2,923 (54.94) | 749 (56.32) | 724 (54.44) | 724 (54.52) | 726 (54.50) | | |

|

Other

ethnicity | 949 (17.84) | 288 (21.65) | 234 (17.59) | 207 (15.59) | 220 (16.52) | | |

|

Other

Hispanic ethnicity | 171 (3.21) | 34 (2.56) | 33 (2.48) | 46 (3.46) | 58 (4.35) | | |

| Education level, N

(%) | | | | | | χ²=46.63 | <0.001 |

|

<9th

grade | 855 (16.07) | 231 (17.37) | 224 (16.84) | 210 (15.81) | 190 (14.26) | | |

|

9-11th

grade | 767 (14.42) | 214 (16.09) | 186 (13.98) | 195 (14.68) | 172 (12.91) | | |

|

High school

grade | 1,255 (23.59) | 329 (24.74) | 324 (24.36) | 323 (24.32) | 279 (20.95) | | |

|

University

attendance or associate of arts degree | 1,307 (24.57) | 324 (24.36) | 334 (25.11) | 318 (23.95) | 331 (24.85) | | |

|

University

graduate or postgraduate education | 1,136 (21.35) | 232 (17.44) | 262 (19.70) | 282 (21.23) | 360 (27.03) | | |

| Alcohol use, N | | | | | | χ²=4.94 | 0.176 |

|

(%) | | | | | | | |

|

Yes | 4,375 (82.24) | 1,092 (82.11) | 1,070 (80.45) | 1,099 (82.76) | 1,114 (83.63) | | |

|

No | 945 (17.76) | 238 (17.89) | 260 (19.55) | 229 (17.24) | 218 (16.37) | | |

| Hypertension, N

(%) | | | | | | χ²=99.76 | <0.001 |

|

Yes | 2,352 (44.21) | 715 (53.76) | 615 (46.24) | 555 (41.79) | 467 (35.06) | | |

|

No | 2,968 (55.79) | 615 (46.24) | 715 (53.76) | 773 (58.21) | 865 (64.94) | | |

| Diabetes, N

(%) | | | | | | χ²=26.44 | <0.001 |

|

Yes | 845 (15.88) | 263 (19.77) | 202 (15.19) | 193 (14.53) | 187 (14.04) | | |

|

No | 4,344 (81.65) | 1,025 (77.07) | 1,095 (82.33) | 1,109 (83.51) | 1,115 (83.71) | | |

|

Borderline | 131 (2.46) | 42 (3.16) | 33 (2.48) | 26 (1.96) | 30 (2.25) | | |

| Coronary heart

disease, N (%) | | | | | | χ²=26.48 | <0.001 |

|

Yes | 471 (8.85) | 150 (11.28) | 138 (10.38) | 94 (7.08) | 89 (6.68) | | |

|

No | 4,849 (91.15) | 1,180 (88.72) | 1,192 (89.62) | 1,234 (92.92) | 1,243 (93.32) | | |

| Angina, N (%) | | | | | | χ²=5.98 | 0.113 |

|

Yes | 245 (4.61) | 77 (5.79) | 59 (4.44) | 56 (4.22) | 53 (3.98) | | |

|

No | 5,075 (95.39) | 1,253 (94.21) | 1,271 (95.56) | 1,272 (95.78) | 1,279 (96.02) | | |

| Tumor history, N

(%) | | | | | | χ²=16.24 | 0.001 |

|

Yes | 461 (8.67) | 151 (11.35) | 105 (7.89) | 103 (7.76) | 102 (7.66) | | |

|

No | 4,859 (91.33) | 1,179 (88.65) | 1,225 (92.11) | 1,225 (92.24) | 1,230 (92.34) | | |

| Smoking status, N

(%) | | | | | | χ²=38.25 | <0.001 |

|

Yes | 3,295 (61.94) | 903 (67.89) | 843 (63.38) | 789 (59.41) | 760 (57.06) | | |

|

No | 2,025 (38.06) | 427 (32.11) | 487 (36.62) | 539 (40.59) | 572 (42.94) | | |

Association between the CALLY index

and PSA levels

In the unadjusted model (model 1), there was a

significant inverse association between the CALLY index and serum

total PSA. Each one-unit increase in the CALLY index corresponded

to a 0.17 ng/ml decrease in the PSA levels (β=-0.17; 95% CI, -0.24

to -0.10). Sensitivity analysis using CALLY quartiles revealed that

participants in Q4 had a 48% reduced PSA level compared with those

in Q1 (β=-0.48; 95% CI, -0.73 to -0.24). In model 2, which was

adjusted for age, ethnicity and BMI, each one-unit increase in the

CALLY index corresponded to a 0.10 ng/ml decrease in the PSA levels

(β=-0.10; 95% CI, -0.17 to -0.03). In a fully adjusted model, model

3, controlling for all relevant covariates, the association

remained significant in which PSA levels decreased by 0.09 ng/ml

for each one-unit increase in the CALLY index (β=-0.09; 95% CI,

-0.16 to -0.02) (Table II).

| Table IIAssociations between the CALLY index

and serum prostate-specific antigen levels across three regression

models. |

Table II

Associations between the CALLY index

and serum prostate-specific antigen levels across three regression

models.

| | Models |

|---|

| | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|

| CALLY index | β (95% CI) | P-value | β (95% CI) | P-value | β (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

|

Continuousa | -0.17

(-0.24-0.10) | <0.001 | -0.10

(-0.17-0.03) | 0.006 | -0.09

(-0.16-0.02) | 0.017 |

| Quartiles | | | | | | |

|

1 | Reference | - | Reference | - | Reference | - |

|

2 | -0.18

(-0.42-0.07) | 0.156 | -0.03

(-0.27-0.20) | 0.795 | -0.01

(-0.25-0.22) | 0.903 |

|

3 | -0.46

(-0.71-0.22) | <0.001 | -0.22

(-0.46-0.01) | 0.065 | -0.20

(-0.45-0.04) | 0.105 |

|

4 | -0.48

(-0.73-0.24) | <0.001 | -0.23

(-0.47-0.01) | 0.066 | -0.20

(-0.45-0.06) | 0.126 |

There is not a non-linear association

between CALLY index and PSA

Due to the skewed distribution of PSA and CALLY

index values, both variables were log-transformed to achieve

normality prior to modeling. The RCS regression was then performed

using the fully adjusted model (model 3) to assess potential

non-linear associations. The results indicated that there was no

significant evidence of a non-linear association between the

log-transformed CALLY index and PSA levels (Fig. 1).

Subgroup analysis

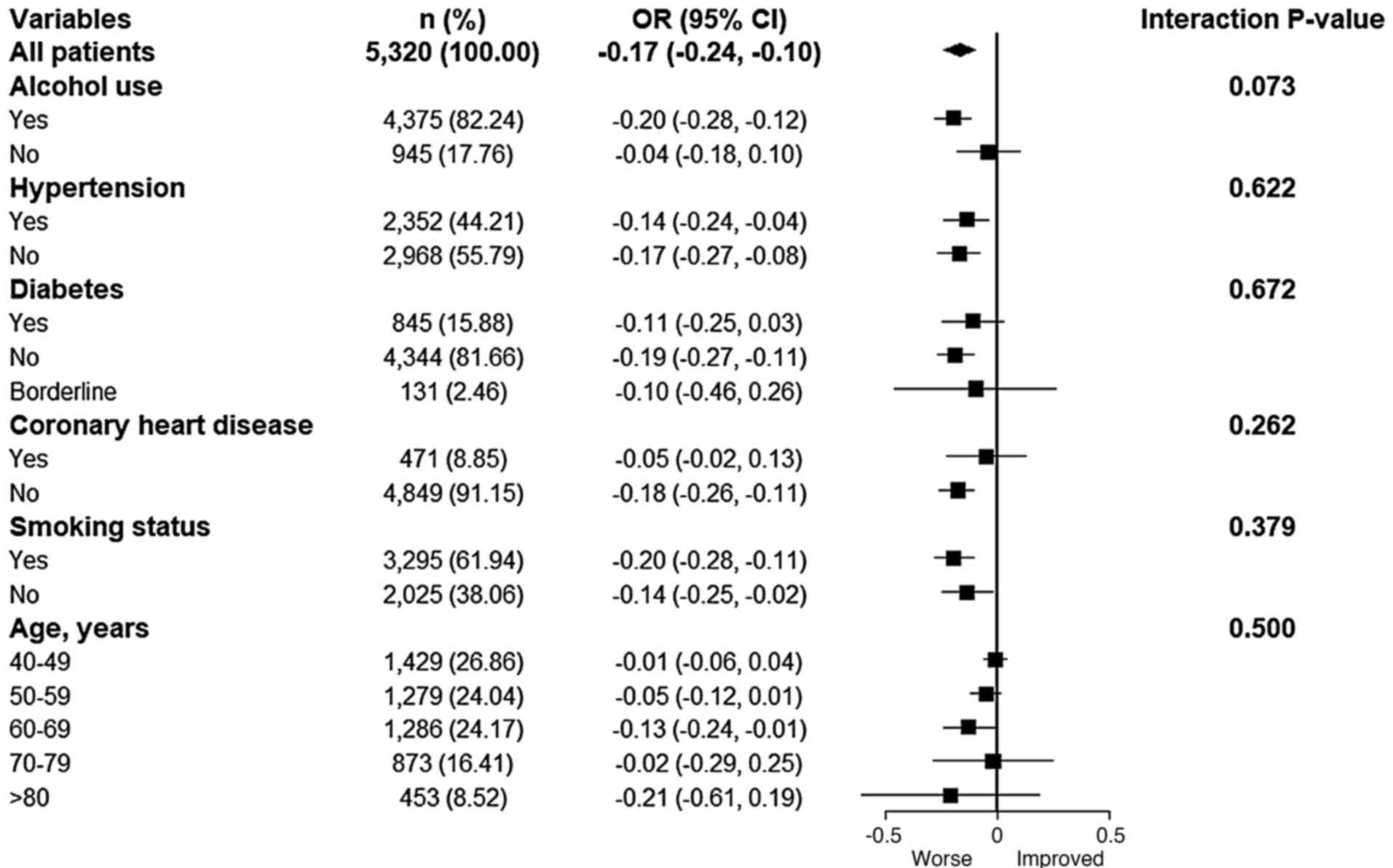

To assess the consistency of the association across

various subpopulations, subgroup analyses were carried out after

the population was stratified by age, smoking status, alcohol

consumption, and the presence or absence of hypertension, diabetes

and coronary heart disease. As shown in Fig. 2, interaction tests did not yield

statistically significant results, indicating that the inverse

association between the CALLY index and PSA levels was not

significantly modified by any of the stratified variables tested.

Therefore, this suggested that the observed association was robust

across different demographic and clinical subgroups.

Discussion

The present study was, to the best of our knowledge,

the first to investigate the association between the CALLY index

and PSA levels in a population without PCa in the United States of

America. Using cross-sectional data from 5,320 participants in the

NHANES database, the present study identified a significant linear

association between the CALLY index and PSA concentrations, with

PSA levels decreasing as the CALLY index increased. Furthermore,

this inverse association was consistent across multiple subgroups,

including those stratified by age, smoking status, alcohol

consumption, hypertension, diabetes and coronary heart disease.

Specifically, each one-unit increase in the CALLY index was

associated with a 0.09 ng/ml reduction in the PSA levels. Although

the association between increased CALLY index values and reduced

PSA levels was statistically significant, the absolute effect size

was relatively small and may have limited clinical impact at the

individual level. However, in population-level screening, even

modest reductions in PSA, particularly when consistently observed,

may contribute to increased specificity and help mitigate

overdiagnosis due to subclinical inflammation. Sensitivity analyses

confirmed the robustness of this association, supporting its

reliability and validity. These findings suggest that an increased

CALLY index may serve as an independent predictor of reduced PSA

levels.

The CALLY index, calculated from levels of CRP,

serum albumin and lymphocyte counts, represents a composite

indicator of systemic inflammation, nutritional status and immune

function (33). It is used as a

prognostic biomarker in various malignancies of the digestive

system such as gastric and colorectal cancer. Previous studies

demonstrate that a reduced CALLY index score is associated with a

reduced OS in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (34), gastric cancer (35), esophageal cancer (36), breast cancer (37) and renal cell carcinoma (38). In addition, data from NHANES

indicates that, compared with reduced CALLY indices, an increased

CALLY index is associated with a reduced risk of all-cause and

cause-specific mortality in patients with cancer (39). Specifically, after comprehensive

adjustment for variables (such as sex, age, ethnicity, poverty

income ratio, smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI, total

cholesterol, ALT, serum creatinine, serum total bilirubin, types of

cancer, prevalences of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease,

chronic kidney disease and hypertension), each one-unit increase in

the natural logarithm of the CALLY index was associated with an 18%

reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality among cancer patients

(39). However, the association

between the CALLY index and PCa is yet to be elucidated.

The present study identified a negative association

between the CALLY index and PSA levels. Although, to the best of

our knowledge, this specific association has not been previously

reported, previous studies examine the individual components of the

CALLY index in association with PSA levels and PCa. For example, a

previous study reveals a non-linear association between serum

albumin and PSA levels, highlighting an inverse association when

albumin concentrations exceed 41 g/l (21). Furthermore, a previous study by Gao

et al (32) reveals that

among men >40 years of age without prostate diseases, the

albumin-globulin ratio (AGR) demonstrates a non-linear association

with PSA, with a negative association when the AGR is <1.32. Low

levels of serum albumin also act as a prognostic factor in patients

with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC)

(22). Elevated CALLY index values

are inversely associated with serum LDH levels, which is a

clinically notable finding since increased LDH activity indicates

enhanced tumor glycolysis, angiogenesis and cellular proliferation,

and is an adverse prognostic biomarker across multiple

malignancies, including PCa (40).

Inflammation serves a critical role in the

development and progression of cancer, prompting investigations

into the prognostic relevance of elevated CRP levels in various

malignancies, including PCa (41).

A prospective population-based cohort study by Stikbakke et

al demonstrates that, compared with low serum CRP levels, high

serum CRP levels are associated with an increased risk of PCa and

have a reduced prognosis (23).

Furthermore, two meta-analyses confirm that CRP is a strong

predictor of adverse outcomes in PCa, including in patients with

mCRPC (42,43). Elevated CRP is also associated with

PSA levels in populations with cancer (44). As an acute-phase protein, CRP can

suppress albumin synthesis and promote prostatic epithelial cell

apoptosis through cytokine-mediated pathways (such as the IL-6 and

TNF pathways), which may reduce the secretion of PSA (45). Inflammatory markers demonstrate

strong associations with PSA levels and PCa outcomes (46). NLR, a marker of systemic

inflammation, has prognostic value in PCa (47). Elevated NLR and total PSA levels are

notably associated with increased Gleason scores (≥7) (24). Furthermore, PLR is an independent

prognostic indicator for both PFS and OS in patients with PCa

(48) and can be used to

distinguish benign prostatic hyperplasia from PCa (49). Lymphocyte-mediated mechanisms may

also influence PSA expression levels. The secretion of interferon-γ

by infiltrating lymphocytes may suppress androgen receptor

activity, which reduces the transcription of PSA (50). Although numerous studies demonstrate

the prognostic value of systemic inflammatory markers such as NLR

and PLR in PCa, it is important to acknowledge their non-specific

nature (46-50).

These ratios may be influenced by a wide range of conditions that

are not associated with malignancy, including infections (such as

pancreatitis and pulmonary infection) (51,52),

autoimmune diseases (such as systemic lupus erythematosus)

(53), trauma (such as traumatic

brain injury) (54) and metabolic

disorders (such as diabetes) (55).

This non-specificity limits their utility as standalone indicators

for PCa screening or prognosis. The findings of the present study

suggested that the CALLY index, as a composite marker, potentially

reflected these complex interactions. One potential mechanism is

that the CALLY index captures a systemic immune state that is

characterized by a Th1/Th2 balance that is skewed toward an

anti-inflammatory profile (56).

Although, to the best of our knowledge, there are not any direct

studies on the impact of the CALLY index on the Th1/Th2 balance,

the findings of the present study suggested that CRP, albumin and

lymphocyte levels individually influenced the Th1/Th2 balance. The

Th1/Th2 balance may skew toward an anti-inflammatory (Th2-dominant)

profile due to chronic infections, allergies, immunosuppressive

cytokines (such as IL-10 and TGF-β), hormonal influences, aging,

diet or environmental factors, which may suppress the

proinflammatory Th1 responses (57). This immune milieu may inhibit the

recruitment of tumor-associated macrophages (58), which reduces the passive diffusion

of PSA from the prostate stroma into the bloodstream (59). The recruitment of tumor-associated

macrophages does not directly induce passive PSA diffusion but

creates a permissive microenvironment (via inflammation, ECM

breakdown and vascular leakiness) that enhances PSA entry into

circulation. This aligns with observations that aggressive tumors

often show higher serum PSA levels (60).

However, the present study had a number of

limitations. Firstly, due to the cross-sectional design, causal

associations between the CALLY index and PSA levels cannot be

established. Therefore, prospective cohort studies should be

carried out in the future in order to validate the findings of the

present study. Secondly, PSA measurements in NHANES were carried

out using the Hybritech method, which differs systematically from

the World Health Organization (WHO)-standardized methods used in a

number of clinical laboratories (61). The Hybritech PSA assay uses

proprietary monoclonal antibodies and an in-house calibration

standard, which yields values 20-30% higher compared with the

WHO-calibrated methods. The WHO methods use polyclonal antibodies

and the WHO International Standard (code, 96/670) (62). This discrepancy may introduce

variability and limit the generalizability of the present results.

Thirdly, a number of laboratory variables, such as globulin and

testosterone levels, as well as lifestyle-associated factors

including the dietary inflammatory index and physical activity,

were not included in the present analysis due to incomplete data,

limited availability across NHANES cycles and a lack of consistent

associations with PSA or CALLY components in the population without

cancer. The omission of these variables may result in an

underestimation of the true association between the CALLY index and

PSA levels.

In conclusion, PSA, the primary biomarker for PCa

screening, is criticized for its limited diagnostic specificity,

which contributes to the ongoing clinical challenges. The present

study, to the best of our knowledge, was the first to reveal a

negative association between PSA levels and the CALLY index, a

composite marker reflecting inflammation, immunity and nutritional

status. The present findings provided an insight into the potential

biological contributors of PSA variability, which may provide

guidance to future research regarding strategies for reducing false

positives in PSA screening. However, due to the cross-sectional

design of the present study, the observed association does not

imply a causal association, nor does it support the immediate

clinical use of the CALLY index as a diagnostic adjunct.

Prospective and mechanistic studies are required to validate the

findings of the present study and investigate the implications for

PCa screening strategies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JH contributed to the conception and the design of

the present study. JH, NX and MF contributed to the acquisition,

analysis and interpretation of the data. JH, NX and MF contributed

to drafting the manuscript or revising the manuscript. JH, NX and

MF read and approved the final version of the manuscript. JH, NX

and MF confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung

H and Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. 75:10–45.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Van Poppel H, Roobol MJ, Chapple CR, Catto

JWF, N'Dow J, Sønksen J, Stenzl A and Wirth M: Prostate-specific

antigen testing as part of a risk-adapted early detection strategy

for prostate cancer: European association of urology position and

recommendations for 2021. Eur Urol. 80:703–711. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Gudmundsson J, Sigurdsson JK,

Stefansdottir L, Agnarsson BA, Isaksson HJ, Stefansson OA,

Gudjonsson SA, Gudbjartsson DF, Masson G, Frigge ML, et al:

Genome-wide associations for benign prostatic hyperplasia reveal a

genetic correlation with serum levels of PSA. Nat Commun.

9(4568)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lokant MT and Naz RK: Presence of PSA

auto-antibodies in men with prostate abnormalities (prostate

cancer/benign prostatic hyperplasia/prostatitis). Andrologia.

47:328–332. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Buddingh KT, Maatje MGF, Putter H, Kropman

RF and Pelger RCM: Do antibiotics decrease prostate-specific

antigen levels and reduce the need for prostate biopsy in type IV

prostatitis? A systematic literature review. Can Urol Assoc J.

12:E25–E30. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Wang X, Lin D and Chen Z:

Relationship between body mass index and concentrations of prostate

specific antigen: A cross-sectional study. Scand J Clin Lab Invest.

80:162–167. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Tan GH, Nason G, Ajib K, Woon DTS,

Herrera-Caceres J, Alhunaidi O and Perlis N: Smarter screening for

prostate cancer. World J Urol. 37:991–999. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Misra-Hebert AD, Hu B, Klein EA,

Stephenson A, Taksler GB, Kattan MW and Rothberg MB: Prostate

cancer screening practices in a large, integrated health system:

2007-2014. BJU Int. 120:257–264. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zaffaroni M, Vincini MG, Corrao G,

Lorubbio C, Repetti I, Mastroleo F, Putzu C, Villa R, Netti S,

D'Ecclesiis O, et al: Investigating nutritional and inflammatory

status as predictive biomarkers in oligoreccurent prostate cancer-A

RADIOSA trial preliminary analysis. Nutrients.

15(4583)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Jurisic V: Multiomic analysis of cytokines

in immuno-oncology. Expert Rev Proteomics. 17:663–674.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Tang Z, Li S, Zeng M, Zeng L and Tang Z:

The association between systemic immune-inflammation index and

prostate-specific antigen: Results from NHANES 2003-2010. PLoS One.

19(e0313080)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Beer TM, Lalani AS, Lee S, Mori M, Eilers

KM, Curd JG, Henner WD, Ryan CW, Venner P, Ruether JD, et al:

C-reactive protein as a prognostic marker for men with

androgen-independent prostate cancer: results from the ASCENT

trial. Cancer. 112:2377–2383. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Liao DW, Hu X, Wang Y, Yang ZQ and Li X:

C-reactive protein is a predictor of prognosis of prostate cancer:

A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Clin Lab Sci.

50:161–171. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Rajwa P, Schuettfort VM, D'Andrea D, Quhal

F, Mori K, Katayama S, Laukhtina E, Pradere B, Motlagh RS,

Mostafaei H, et al: Impact of systemic Immune-inflammation Index on

oncologic outcomes in patients treated with radical prostatectomy

for clinically nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 39:785

e19–785 e27. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Jurisic V, Terzic T, Colic S and Jurisic

M: The concentration of TNF-alpha correlate with number of

inflammatory cells and degree of vascularization in radicular

cysts. Oral Dis. 14:600–605. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Cui S, Cao S, Chen Q, He Q and Lang R:

Preoperative systemic inflammatory response index predicts the

prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after liver

transplantation. Front Immunol. 14(1118053)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Sawada R, Akiyoshi T, Kitagawa Y, Hiyoshi

Y, Mukai T, Nagasaki T, Yamaguchi T, Konishi T, Yamamoto N, Ueno M

and Fukunaga Y: Systemic inflammatory markers combined with

tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte density for the improved prediction

of response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer. Ann

Surg Oncol. 28:6189–6198. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Sun Z, Ju Y, Han F, Sun X and Wang F:

Clinical implications of pretreatment inflammatory biomarkers as

independent prognostic indicators in prostate cancer. J Clin Lab

Anal. 32(e22277)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Lin HY, Zhu X, Aucoin AJ, Fu Q, Park JY

and Tseng TS: Dietary and serum antioxidants associated with

prostate-specific antigen for middle-aged and older men. Nutrients.

15(3298)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Song J, Chen C, He S, Chen W, Su J, Yuan

D, Sun F and Zhu J: Is there a non-linear relationship between

dietary protein intake and prostate-specific antigen: Proof from

the national health and nutrition examination survey (2003-2010).

Lipids Health Dis. 19(82)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Xu K, Yan Y, Cheng C, Li S, Liao Y, Zeng

J, Chen Z and Zhou J: The relationship between serum albumin and

prostate-specific antigen: A analysis of the National Health and

Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2010. Front Public Health.

11(1078280)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Fan L, Chi C, Guo S, Wang Y, Cai W, Shao

X, Xu F, Pan J, Zhu Y, Shangguan X, et al: Serum pre-albumin

predicts the clinical outcome in metastatic castration-resistant

prostate cancer patients treated with abiraterone. J Cancer.

8:3448–3455. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Stikbakke E, Richardsen E, Knutsen T,

Wilsgaard T, Giovannucci EL, McTiernan A, Eggen AE, Haugnes HS and

Thune I: Inflammatory serum markers and risk and severity of

prostate cancer: The PROCA-life study. Int J Cancer. 147:84–92.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Rulando M, Siregar GP and Warli SM:

Correlation between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio with Gleason

score in patients with prostate cancer at Adam Malik Hospital Medan

2013-2015. Urol Ann. 13:53–55. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Müller L, Hahn F, Mähringer-Kunz A, Stoehr

F, Gairing SJ, Michel M, Foerster F, Weinmann A, Galle PR, Mittler

J, et al: Immunonutritive scoring for patients with hepatocellular

carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization: Evaluation of

the CALLY Index. Cancers (Basel). 13(5018)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Hashimoto I, Tanabe M, Onuma S, Morita J,

Nagasawa S, Maezawa Y, Kanematsu K, Aoyama T, Yamada T, Yukawa N,

et al: Clinical impact of the C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte

index in post-gastrectomy patients with gastric cancer. In Vivo.

38:911–916. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Liu XY, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Ruan GT, Liu T,

Xie HL, Ge YZ, Song MM, Deng L and Shi HP: The value of

CRP-albumin-lymphocyte index (CALLY index) as a prognostic

biomarker in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Support Care

Cancer. 31(533)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Takeda Y, Sugano H, Okamoto A, Nakano T,

Shimoyama Y, Takada N, Imaizumi Y, Ohkuma M, Kosuge M and Eto K:

Prognostic usefulness of the C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte

(CALLY) index as a novel biomarker in patients undergoing

colorectal cancer surgery. Asian J Surg. 47:3492–3498.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Iida H, Tani M, Komeda K, Nomi T,

Matsushima H, Tanaka S, Ueno M, Nakai T, Maehira H, Mori H, et al:

Superiority of CRP-albumin-lymphocyte index (CALLY index) as a

non-invasive prognostic biomarker after hepatectomy for

hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 24:101–115. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Nazzal Z, Khatib B, Al-Quqa B, Abu-Taha L

and Jaradat A: The prevalence and risk factors of urinary

incontinence among women with type 2 diabetes in the North West

Bank: A cross-sectional study. Lancet. 398 (Suppl

1)(S42)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Laffin RJ, Chan DW, Tanasijevic MJ,

Fischer GA, Markus W, Miller J, Matarrese P, Sokoll LJ, Bruzek DJ,

Eneman J, et al: Hybritech total and free prostate-specific antigen

assays developed for the Beckman Coulter access automated

chemiluminescent immunoassay system: A multicenter evaluation of

analytical performance. Clin Chem. 47:129–132. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Gao S, Li S, Wu B, Wang J, Ding S and Tang

Z: Relationship between albumin-globulin ratio and

prostate-specific antigen: A cross-sectional study based on NHANES

2003-2010. BMC Urol. 25(3)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Wang W, Gu J, Liu Y, Liu X, Jiang L, Wu C

and Liu J: Pre-treatment CRP-albumin-lymphocyte index (CALLY Index)

as a prognostic biomarker of survival in patients with epithelial

ovarian cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 14:2803–2812. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Cheng H, Ma J, Zhao F, Liu Y, Wu J, Wu T,

Li H, Zhang B, Liu H, Fu J, et al: IINS Vs CALLY index: A battle of

prognostic value in NSCLC patients following surgery. J Inflamm

Res. 18:493–503. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Zhang H, Shi J, Xie H, Liu X, Ruan G, Lin

S, Ge Y, Liu C, Chen Y, Zheng X, et al: Superiority of

CRP-albumin-lymphocyte index as a prognostic biomarker for patients

with gastric cancer. Nutrition. 116(112191)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Ma R, Okugawa Y, Shimura T, Yamashita S,

Sato Y, Yin C, Uratani R, Kitajima T, Imaoka H, Kawamura M, et al:

Clinical implications of C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte

(CALLY) index in patients with esophageal cancer. Surg Oncol.

53(102044)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Zhuang J, Wang S, Wang Y, Wu Y and Hu R:

Prognostic value of CRP-Albumin-lymphocyte (CALLY) index in

patients undergoing surgery for breast cancer. Int J Gen Med.

17:997–1005. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Hirata H, Fujii N, Oka S, Nakamura K,

Shimizu K, Kobayashi K, Hiroyoshi T, Isoyama N and Shiraishi K:

C-reactive protein-albumin-lymphocyte index as a novel biomarker

for progression in patients undergoing surgery for renal cancer.

Cancer Diagn Progn. 4:748–753. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Zhu D, Lin YD, Yao YZ, Qi XJ, Qian K and

Lin LZ: Negative association of C-reactive

protein-albumin-lymphocyte index (CALLY index) with all-cause and

cause-specific mortality in patients with cancer: Results from

NHANES 1999-2018. BMC Cancer. 24(1499)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Jurisic V, Radenkovic S and Konjevic G:

The actual role of LDH as tumor marker, biochemical and clinical

aspects. Adv Exp Med Biol. 867:115–124. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Graff JN, Beer TM, Liu B, Sonpavde G and

Taioli E: Pooled analysis of C-reactive protein levels and

mortality in prostate cancer patients. Clin Genitourin Cancer.

13:e217–e221. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Naik G, Morgan C, Rocha P, Templeton A,

Pond G and Sonpavde G: Prognostic impact of C-reactive protein

(CRP) in metastatic prostate cancer (MPC): A systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 32(43)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhou K, Li C, Chen T, Zhang X and Ma B:

C-reactive protein levels could be a prognosis predictor of

prostate cancer: A meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14(1111277)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Santotoribio JD and Jimenez-Romero ME:

Serum biomarkers of inflammation for diagnosis of prostate cancer

in patients with nonspecific elevations of serum prostate specific

antigen levels. Transl Cancer Res. 8:273–278. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Lehrer S, Diamond EJ, Mamkine B, Droller

MJ, Stone NN and Stock RG: C-reactive protein is significantly

associated with prostate-specific antigen and metastatic disease in

prostate cancer. BJU Int. 95:961–962. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Nepal SP, Nakasato T, Fukagai T, Ogawa Y,

Nakagami Y, Shichijo T, Morita J, Maeda Y, Oshinomi K, Unoki T, et

al: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios

alone or combined with prostate-specific antigen for the diagnosis

of prostate cancer and clinically significant prostate cancer.

Asian J Urol. 10:158–165. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Yin X, Xiao Y, Li F, Qi S, Yin Z and Gao

J: Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in prostate

cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine

(Baltimore). 95(e2544)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Salciccia S, Frisenda M, Bevilacqua G,

Viscuso P, Casale P, De Berardinis E, Di Pierro GB, Cattarino S,

Giorgino G, Rosati D, et al: Prognostic role of

platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in

patients with non-metastatic and metastatic prostate cancer: A

meta-analysis and systematic review. Asian J Urol. 11:191–207.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Yuksel OH, Urkmez A, Akan S, Yldirim C and

Verit A: Predictive value of the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in

diagnosis of prostate cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.

16:6407–6412. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Kwon YS, Han CS, Yu JW, Kim S, Modi P,

Davis R, Park JH, Lee P, Ha YS, Kim WJ and Kim IY: Neutrophil and

lymphocyte counts as clinical markers for stratifying low-risk

prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 14:e1–e8. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Xu MS, Xu JL, Gao X, Mo SJ, Xing JY, Liu

JH, Tian YZ and Fu XF: Clinical study of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte

ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in

hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis and acute biliary

pancreatitis with persistent organ failure. World J Gastrointest

Surg. 16:1647–1659. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Wang RH, Wen WX, Jiang ZP, Du ZP, Ma ZH,

Lu AL, Li HP, Yuan F, Wu SB, Guo JW, et al: The clinical value of

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), systemic immune-inflammation

index (SII), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and systemic

inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the occurrence

and severity of pneumonia in patients with intracerebral

hemorrhage. Front Immunol. 14(1115031)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Wu Y, Chen Y, Yang X, Chen L and Yang Y:

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte

ratio (PLR) were associated with disease activity in patients with

systemic lupus erythematosus. Int Immunopharmacol. 36:94–99.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Wang T, Yang Z, Zhou B and Chen Y:

Relationship between NLR and PLR ratios and the occurrence and

prognosis of progressive hemorrhagic injury in patients with

traumatic brain injury. J Invest Surg. 38(2470453)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Li X, Wang L, Liu M, Zhou H and Xu H:

Association between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and diabetic

kidney disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A

cross-sectional study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14(1285509)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Matia-Garcia I, Vadillo E, Pelayo R,

Muñoz-Valle JF, García-Chagollán M, Loaeza-Loaeza J,

Vences-Velázquez A, Salgado-Goytia L, García-Arellano S and

Parra-Rojas I: Th1/Th2 balance in young subjects: relationship with

cytokine levels and metabolic profile. J Inflamm Res. 14:6587–6600.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Zhu J: T helper cell differentiation,

heterogeneity, and plasticity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol.

10(a030338)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Shapouri-Moghaddam A, Mohammadian S,

Vazini H, Taghadosi M, Esmaeili SA, Mardani F, Seifi B, Mohammadi

A, Afshari JT and Sahebkar A: Macrophage plasticity, polarization,

and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol. 233:6425–6440.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

McNeel DG, Nguyen LD, Ellis WJ, Higano CS,

Lange PH and Disis ML: Naturally occurring prostate cancer

antigen-specific T cell responses of a Th1 phenotype can be

detected in patients with prostate cancer. Prostate. 47:222–229.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Guan H, Peng R, Fang F, Mao L, Chen Z,

Yang S, Dai C, Wu H, Wang C, Feng N, et al: Tumor-associated

macrophages promote prostate cancer progression via

exosome-mediated miR-95 transfer. J Cell Physiol. 235:9729–9742.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Garrido MM, Marta JC, Ribeiro RM, Pinheiro

LC, Holdenrieder S and Guimarães JT: Comparison of three assays for

total and free PSA using hybritech and WHO calibrations. In Vivo.

35:3431–3439. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Kort SA, Martens F, Vanpoucke H, van

Duijnhoven HL and Blankenstein MA: Comparison of 6 automated assays

for total and free prostate-specific antigen with special reference

to their reactivity toward the WHO 96/670 reference preparation.

Clin Chem. 52:1568–1574. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|