Introduction

Anaemia is defined as a low blood haemoglobin (Hb)

concentration and is a public health problem (1). It can occur in all stages of life,

particularly during pregnancy and childhood (2). Iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) is the

predominant cause of anaemia during pregnancy and is one of the

primary consequences of iron deficiency (ID) (3).

It is hypothesised that the occurrence of IDA in

pregnancy is >40%. IDA occurs due to an increased need for the

development of the fetoplacental unit, an increase in the mass of

erythrocytes (E), and an increase in the volume of plasma to

compensate for iron loss during childbirth. In developed countries,

the iron intake is often below nutritional needs (4).

Undiagnosed and untreated IDA can have a significant

impact on the health of both the mother and the child. In mothers,

IDA is associated with a generally poor condition, decreased

working capacity, fatigue, pallor, breathlessness, palpitations and

headaches. The risk of postpartum depression is significantly

increased compared with pregnant women without IDA. Fatigue and

depression often affect the relationship between mother and child.

During pregnancy, IDA is also associated with problems with the

placenta, intrauterine death, infections, retardation of

intrauterine growth, low birth weight, preterm delivery and

perinatal mortality. In infants, IDA is associated with poor

postnatal growth, reduced cognitive ability, and early ID (5). Iron is also necessary for the activity

of enzymes related to the development of the central nervous system

(4).

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines IDA as

anaemia accompanied by depleted iron stores and a compromised

supply of iron to the tissues (1).

IDA develops when the supply of iron is insufficient to sustain

erythropoiesis, leading to a decreased concentration of Hb

(6).

To prevent the development of IDA, the WHO has

developed a system for classifying IDA in pregnant women (1).

According to the WHO, IDA in pregnancy is present if

Hb is <110 g/l, serum ferritin <15 µg/l, and haematocrit

(HCT) <0.33 l/l (7). To

determine the presence of anaemia in pregnant women, the WHO

recommends the determination of Hb and ferritin concentrations

(8).

Laboratory determination plays a crucial role in

diagnosing IDA. For the differential diagnosis of IDA, it is

necessary to determine the complete blood count (CBC), which

includes Hb concentration and HCT, as diagnostic criteria for IDA.

In addition, ferritin concentration in the serum sample should be

determined. Ferritin is considered the gold standard for diagnosing

IDA, but it has its limitations. As an acute-phase reactant,

ferritin levels can be influenced by inflammation; therefore, it is

essential to determine C-reactive protein (CRP) levels for an

accurate diagnosis. It is recommended to determine ferritin levels

once CRP levels have returned to normal. Conversely, serum iron

(Fe) exhibits significant daily variation; therefore, determining

transferrin levels is also recommended (4). Hb concentration is not a reliable

parameter during pregnancy due to physiological changes in plasma

volume and E mass in pregnant women. Therefore, Hb is not a

sensitive or specific indicator of IDA (3). Regarding erythrocyte constants, the

mean corpuscular volume (MCV) initially rises slightly and then

falls, which can lead to drawing an incorrect conclusion. Mean

corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) and mean corpuscular haemoglobin

concentration (MCHC) are reduced only when anaemia is severe. Red

blood cell distribution width (RDW) represents a quantitative

measure of the variation in the size of E. This is a routine

parameter and part of a CBC, easily measurable, independent

indicator, and increases at least 4 weeks before MCV. RDW is an

early indicator of the change in E, which is essential for

diagnosing IDA (9). Hb and HCT

effectively provide the same data. They are roughly described by

the following formula: Hb x 3/1,000=HCT. Hb is measured directly

using spectrophotometry, while HCT is calculated as the product of

the E count and MCV (10,11).

During a normal pregnancy, Fe concentration, the

percentage of Fe saturation, and total iron binding capacity (TIBC)

have less diagnostic importance, as Fe and the percentage of Fe

saturation decrease as TIBC increases (9). It is also important to emphasise the

pre-analytical requirements for Fe determination. A pregnant woman

should not drink vitamin drinks up to 48 h before drawing blood.

Since Fe shows significant daily variation (up to 70%), blood

should be drawn before 10 AM. If a pregnant woman is taking Fe

preparations, the determination should be postponed for at least 10

days after the last oral Fe dose, 3 days after intravenous Fe

preparations, and 1 month after intramuscular Fe preparations. It

is also important not to carry out Fe determination during an acute

infection, as this can cause Fe to be trapped within the cells of

the reticuloendothelial system. Pregnant women often undergo Fe

therapy before pregnancy or begin taking Fe supplements early in

pregnancy, and this information should be considered when

interpreting laboratory results (12).

It should also be noted that reference intervals

differ between pregnant and non-pregnant women of the same age,

primarily due to the previously mentioned increase in plasma volume

during pregnancy (4).

It is essential to diagnose IDA as early as possible

to prevent complications for both the mother and the child.

Therefore, it is also important to use diagnostic parameters that

are simple, safe and cost-effective (13).

Inspired by the notion of calculated parameters with

strong diagnostic accuracy, in the present study, new parameters,

as ratios of routinely available parameters (E, Fe, HCT, MCV, and

RDW), are proposed for their diagnostic value.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic

accuracy of various parameters and define the best possible

parameter for diagnosing IDA. Simple and widely applicable

calculated ratios were assessed, including Fe/E, MCV/RDW, RDW/E,

RDW/Fe and RDW/HCT, and a scoring model was proposed. In view of

the importance of early diagnosis and the limitations of current

diagnostic parameters, the scoring model may represent a meaningful

and easy-to-use diagnostic tool, allowing for diagnosis of IDA

earlier, while making it more accessible and cost-effective,

thereby facilitating timely therapeutic intervention (14).

Materials and methods

Study plan

The present study was performed at the Clinical

Hospital Center Rijeka (Rijeka, Croatia) between August 2019 and

January 2020. A total of 623 pregnant women who had low-risk,

full-term pregnancies, including women who had received Fe

supplements, were enrolled in the study. The median age of the

pregnant women was 32 years (age range, 16-47). Blood samples were

collected either on the day of delivery or the day before when they

were admitted to the hospital.

The study was performed in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the Clinical Hospital Center Rijeka, Rijeka (approval no.

2170-29-02/1-19-2; class, 003-05/19-1/110; approval date, 15 July

2019; Rijeka, Croatia). Written informed consent was obtained from

all participants in the study.

The inclusion criteria were women who delivered

between 38 and 41 weeks of gestation, those with premature rupture

of membranes lasting no longer than 12 h, women giving birth for

the first time, and those who had multiple births (up to three

births).

The exclusion criteria were twin pregnancies, those

with gestational diabetes requiring medical treatment,

hypertension, preeclampsia, uterine anomalies, bleeding during

pregnancy, women who had had multiple births with ≥4 deliveries,

smokers and women with chronic bowel disease.

Sample collection and analysis

For blood collection, two blood tubes were used; one

tube (K3EDTA tube 3 ml, 13x75 mm; cat. no. 454217;

VACUETTE®, Greiner Bio-One Ltd.) to determine CBC and

the other tube (serum clot activator tubes with gel separator 8 ml,

16x100 mm; cat. no. 455071; VACUETTE®, Greiner Bio-One

Ltd.) for determining Fe concentration. The blood samples were sent

to the Medical Biochemical Laboratory of the Clinical Hospital

Center Rijeka (Rijeka, Croatia), and all test measurements were

performed within 3 h of collection.

The determination of CBC parameters (E, Hb, HCT, MCV

and RDW) were performed using the ADVIA 2120 Hematology Analyzer

(Siemens Healthineers) based on colourimetric, peroxidase-based

optical and laser optical methods, while the serum test (Fe) was

performed on an Olympus AU 640 Automatic Biochemical Analyzer

(Olympus Corporation), based on the spectrophotometric principle

with manufacturer-provided reagents. In addition to internal

quality control procedures, external quality control CROQALM HDMBLM

(croqalm.hdmblm.hr) and LABQUALITY EQAS

(my.labscala.fi) were also performed at the

Clinical Hospital Center Rijeka laboratory.

The clinical criterion for IDA diagnosis in the

present study was defined based on the WHO threshold of Hb <110

g/l, and pregnant women were classified as anaemic and non-anaemic

based on this threshold (6).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc

software version 20.104 (MedCalc Software Ltd.). The Shapiro-Wilk

test was used to determine the normality of the distribution of

variables. E followed a normal distribution, thus data are

presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), while other

parameters did not follow a normal distribution, and are presented

as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Pearson's correlation

coefficient (r) was used for correlation analysis of normally

distributed data and Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (ρ)

was used for correlation analysis of non-normally distributed data

with a corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

The difference between anaemic and non-anaemic

groups was determined by the unpaired t-test for normal data

distribution and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normal data

distribution. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, with the

respective 95% CI of the evaluated parameters in anaemic and

non-anaemic pregnant women in diagnosing IDA, were determined.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis and the area

under the curve (AUC) were used for this purpose. The optimal

cut-off value was selected according to the Youden index.

Scoring model

For the purpose of earlier and more accurate IDA

recognition, a scoring model based on parameters routinely

determined in a medical biochemical laboratory was developed. The

model consisted of five components, each representing a ratio of

simple haematological and biochemical parameters: Fe/E, MCV/RDW,

RDW/E, RDW/Fe and RDW/HCT. Whether the measured values were higher

or lower than the limit values was considered. The limit values of

the ratios were obtained using ROC curve analysis based on data

from all 623 pregnant women (both anaemic and non-anaemic).

Concentrations higher than the limit values where the criterion was

met were scored 1, and those lower than the limit values where the

criterion was not met were scored 0. The final score was calculated

as the sum of all five components (ranging from 0-5) and reflects

the severity of anaemia, allowing for earlier diagnosis and timely

therapeutic intervention.

Results

Of the 623 pregnant women included, 51% were

primigravida, 32% had one previous birth and 17% had ≥2 previous

births (Table SI). Based on the Hb

concentration, 133 women (21%) were classified as anaemic, 209

(34%) were anaemic according to RDW/HCT and 149 (24%) according to

HCT (Table SII). These findings

suggest that RDW/HCT and HCT are more sensitive indicators of IDA

than Hb concentration.

All tested parameters in anaemic and non-anaemic

pregnant women are presented in Table

I. The values of all tested parameters Fe/E, MCV/RDW, RDW/E,

RDW/Fe, RDW/HCT, E, Fe, Hb, HCT, MCV and RDW were significantly

different between the anaemic and non-anaemic pregnant women

(P<0.001). In the anaemic group, E, Fe, HCT, MCV, Fe/E and

MCV/RDW values were statistically lower, and RDW, RDW/E, RDW/Fe and

RDW/HCT were statistically higher compared with non-anaemic

pregnant women.

| Table IAssessed parameters in the anaemic and

non-anaemic pregnant women. |

Table I

Assessed parameters in the anaemic and

non-anaemic pregnant women.

| Parameter (unit) | Anaemic, n=133 | Non-anaemic,

n=490 | P-value |

|---|

| Hb (g/lb) | 102 (97-106) | 123 (117-130) |

<0.001a |

| E

(x1012/lc) | 3.77±0.38 | 4.20±0.33 |

<0.001a |

| Fe

(µmol/lb) | 8 (6-10) | 14 (10-18) |

<0.001a |

| HCT (l/lb) | 0.31 (0.29-0.32) | 0.36 (0.34-0.38) |

<0.001a |

| MCV (flb) | 82.5 (75.4-87.3) | 87.7 (84.6-90.8) |

<0.001a |

| RDW (%b) | 15.0 (14.1-15.9) | 14.3 (13.7-15.0) |

<0.001a |

| Fe/E (µmol

x10-12b) | 2.0 (1.5-2.8) | 3.2 (2.5-4.4) |

<0.001a |

| MCV/RDW (fl

x10-2b) | 5.5 (4.8-6.1) | 6.1 (5.7-6.6) |

<0.001a |

| RDW/E

(%lx10-12b) | 4.0 (3.8-4.3) | 3.4 (3.2-3.6) |

<0.001a |

| RDW/Fe

(lx10-2/µmolb) | 2.0 (1.4-2.7) | 1.1 (0.8-1.4) |

<0.001a |

| RDW/HCT

(l/lx10-2b) | 49.3

(46.3-54.5) | 39.4

(36.8-43.0) |

<0.001a |

The correlations between Hb and all parameters are

shown in Table II. A weak

correlation (correlation coefficients from 0.250-0.500) was found

for MCV, Fe/E and MCV/RDW, likely due to their previously mentioned

limitations in diagnosing IDA. A moderate correlation (correlation

coefficients from 0.500-0.750) was found for E, Fe, RDW/E and

RDW/Fe. A strong correlation (correlation coefficients >0.750)

was found for HCT and RDW/HCT. No significant correlation

(correlation coefficient <0.250) was found for RDW.

| Table IICorrelations between Hb and all

tested parameters. |

Table II

Correlations between Hb and all

tested parameters.

| Parameter

(unit) | Correlation

coefficient (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| E

(x1012/l) | r=0.650 (0.602 to

0.693) |

<0.001a |

| Fe (µmol/l) | ρ=0.545 (0.487 to

0.598) |

<0.001a |

| HCT (l/l) | ρ=0.941 (0.932 to

0.950) |

<0.001a |

| MCV (fl) | ρ=0.423 (0.356 to

0.485) |

<0.001a |

| RDW (%) | ρ=-0.243 (-0.316 to

-0.167) |

<0.001a |

| Fe/E (µmol

x10-12) | ρ=0.426 (0.360 to

0.489) |

<0.001a |

| MCV/RDW (fl

x10-2) | ρ=0.360 (0.289 to

0.426) |

<0.001a |

| RDW/E

(%lx10-12) | ρ=-0.743 (-0.777 to

-0.706) |

<0.001a |

| RDW/Fe

(lx10-2/µmol) | ρ=-0.552 (-0.604 to

-0.495) |

<0.001a |

| RDW/HCT

(l/lx10-2) | ρ=-0.804 (-0.830 to

-0.774) |

<0.001a |

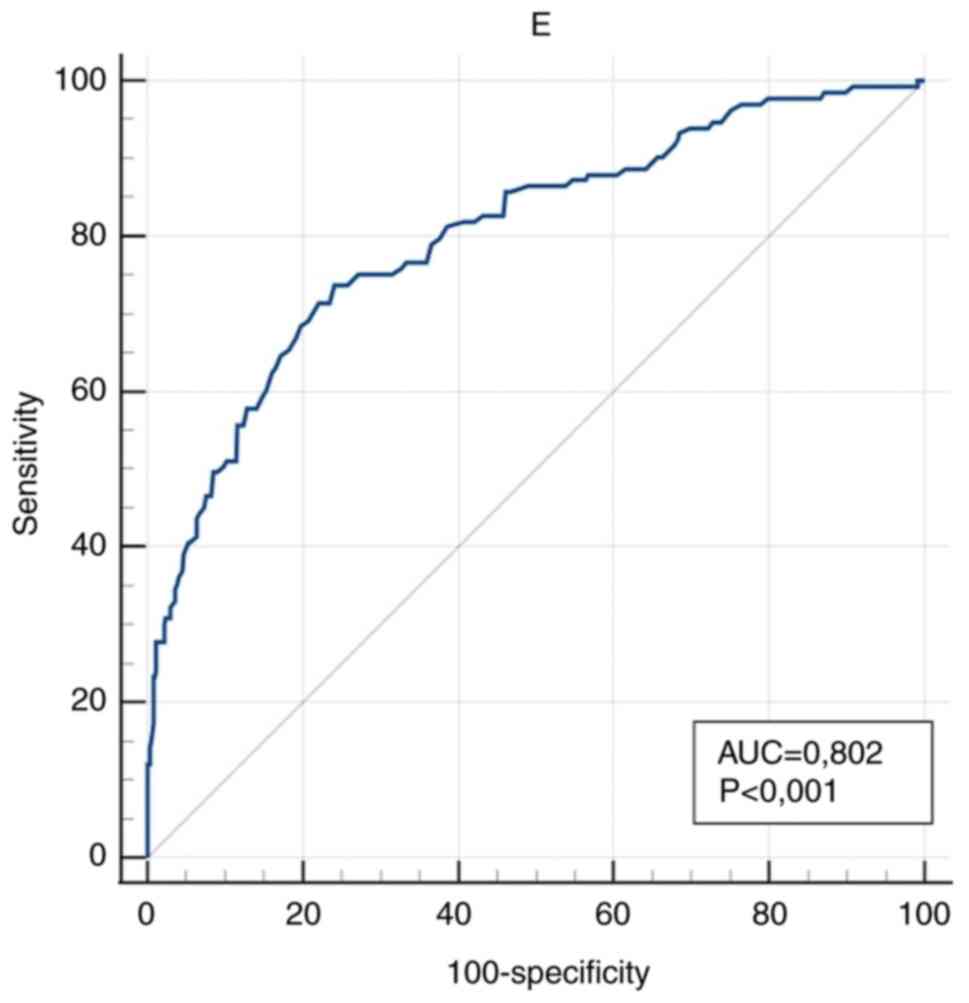

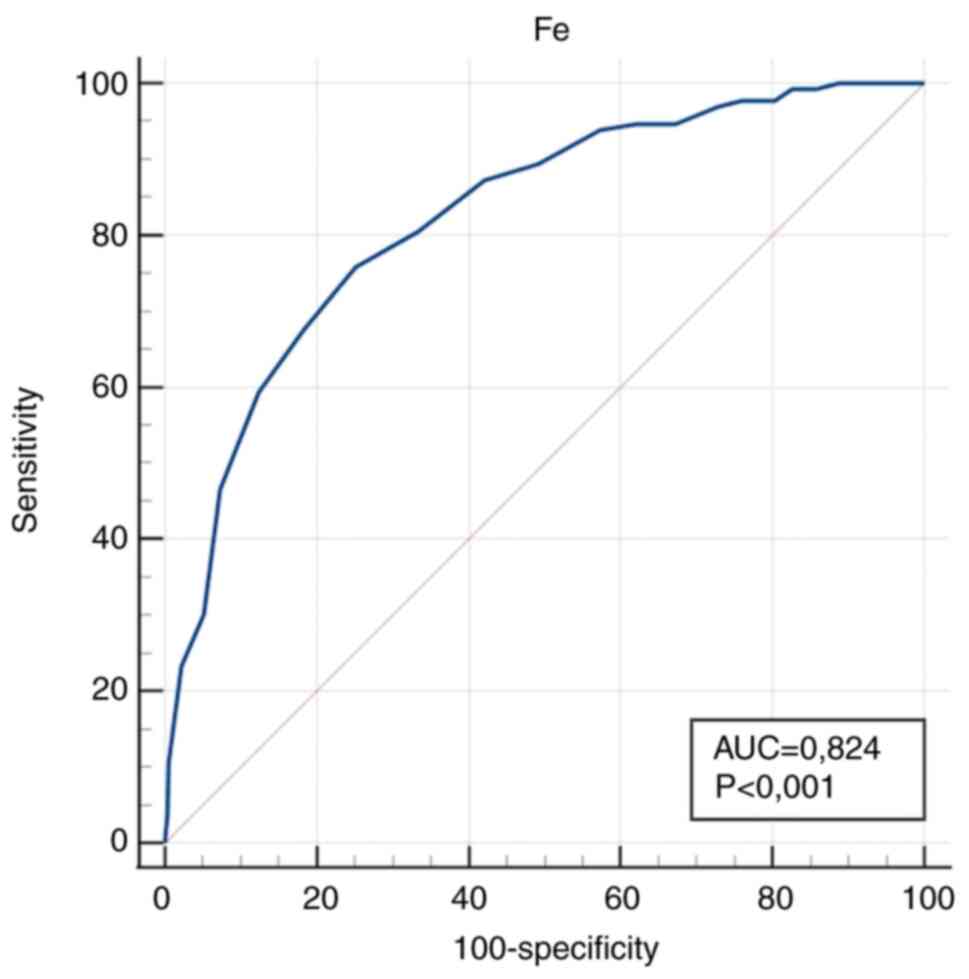

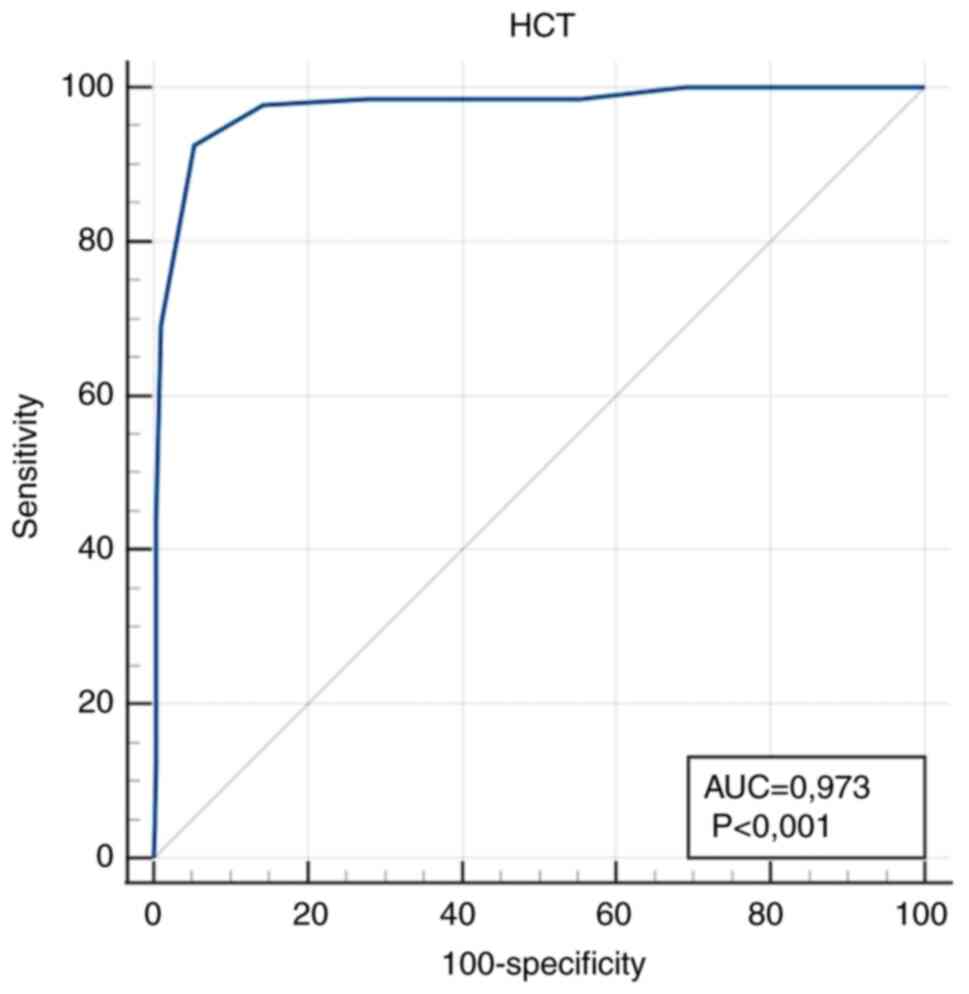

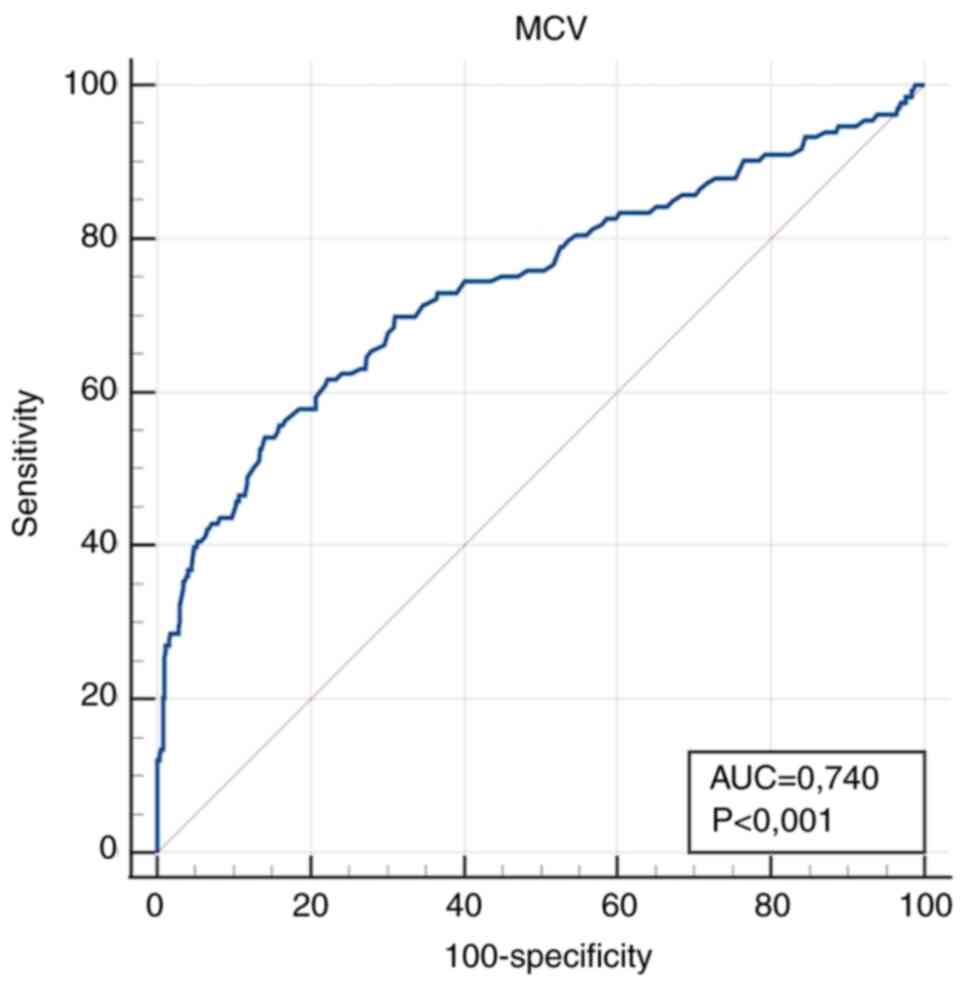

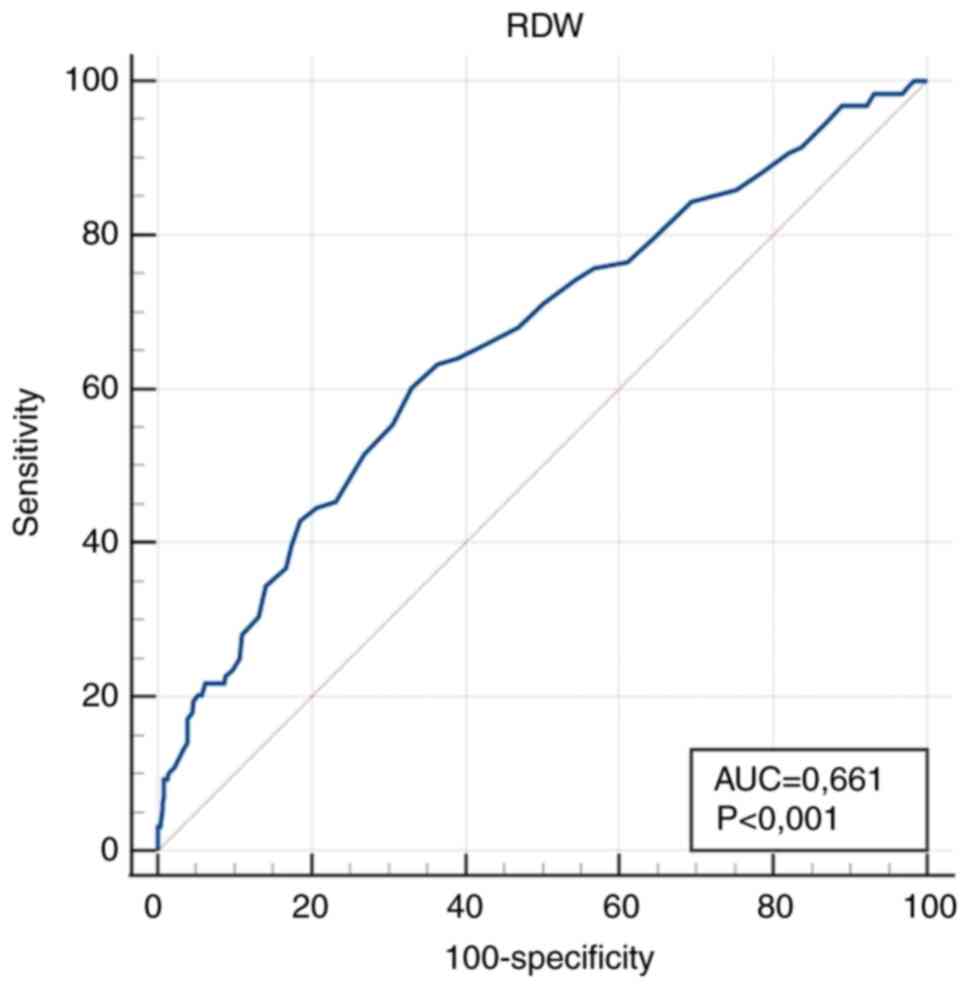

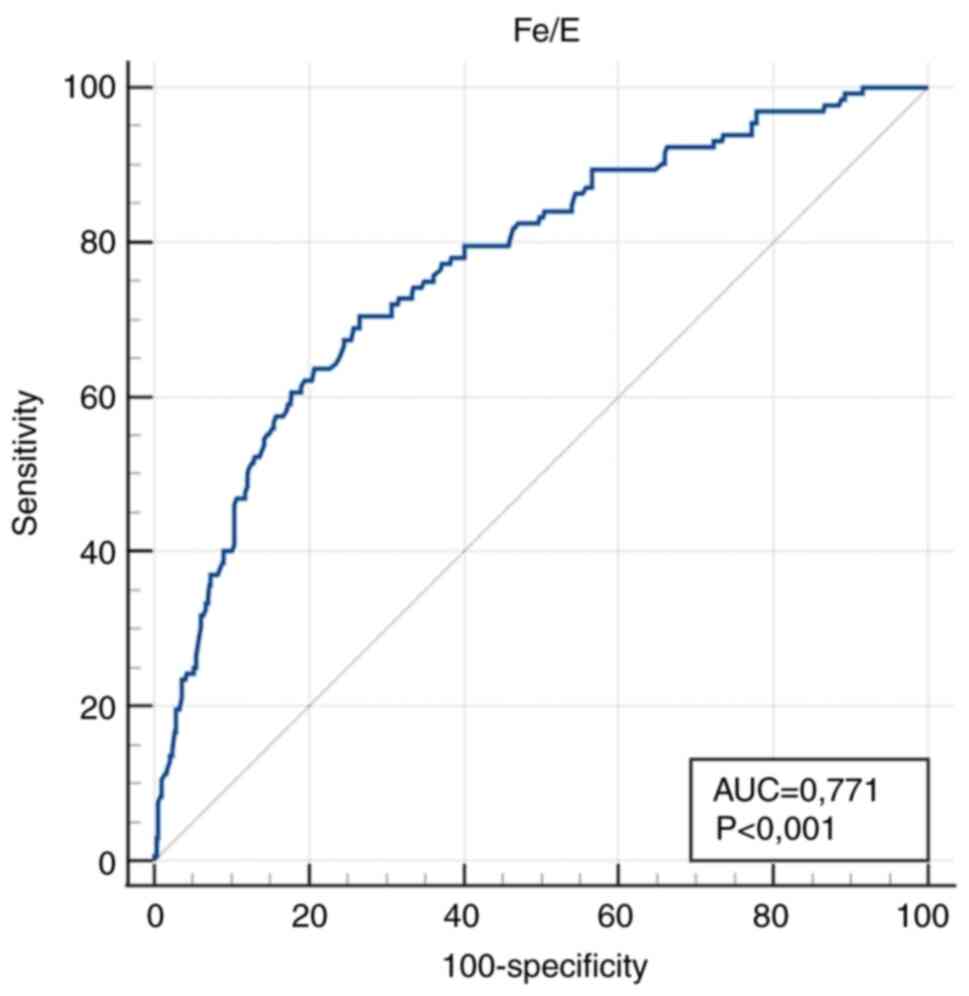

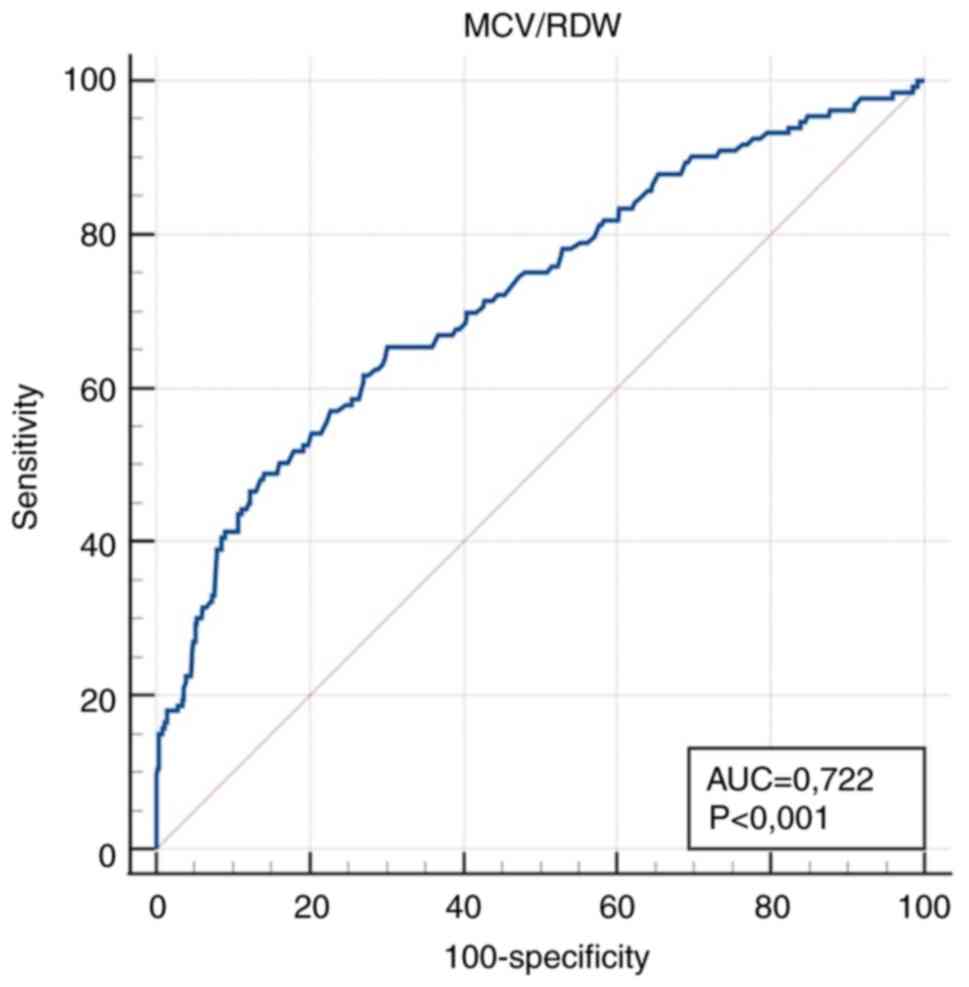

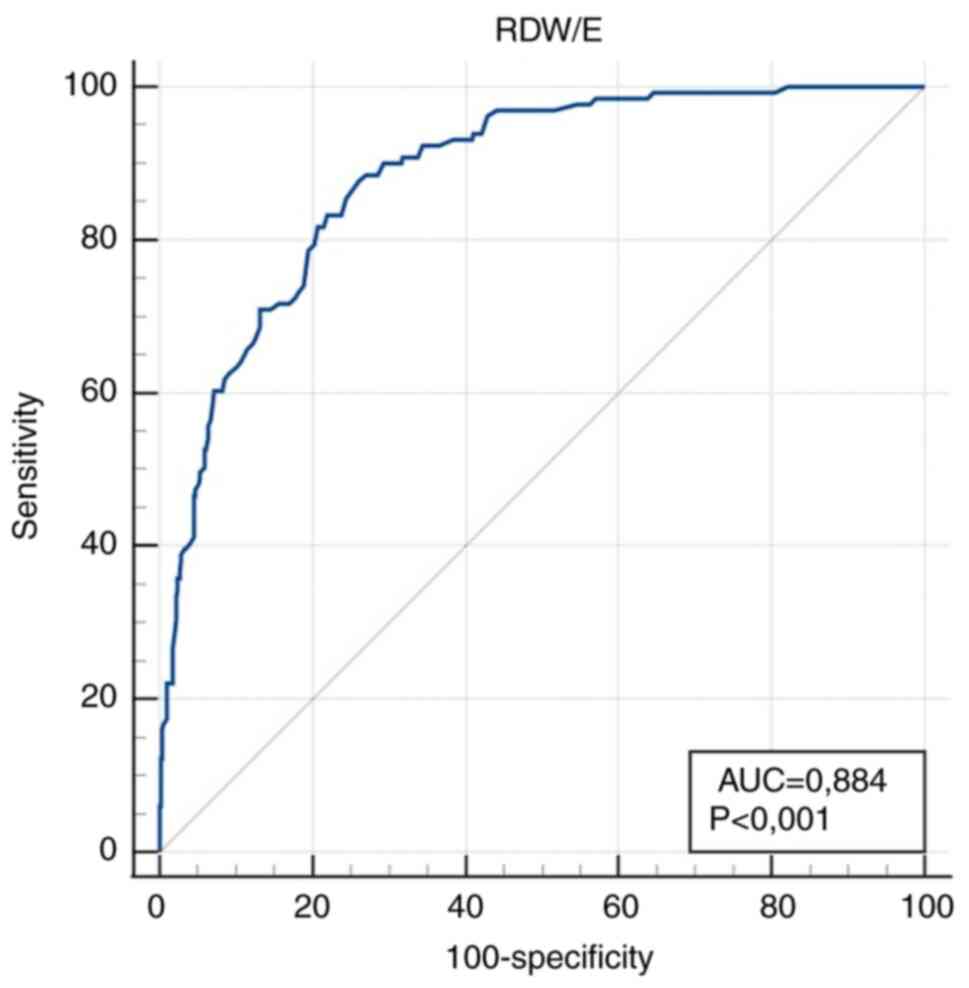

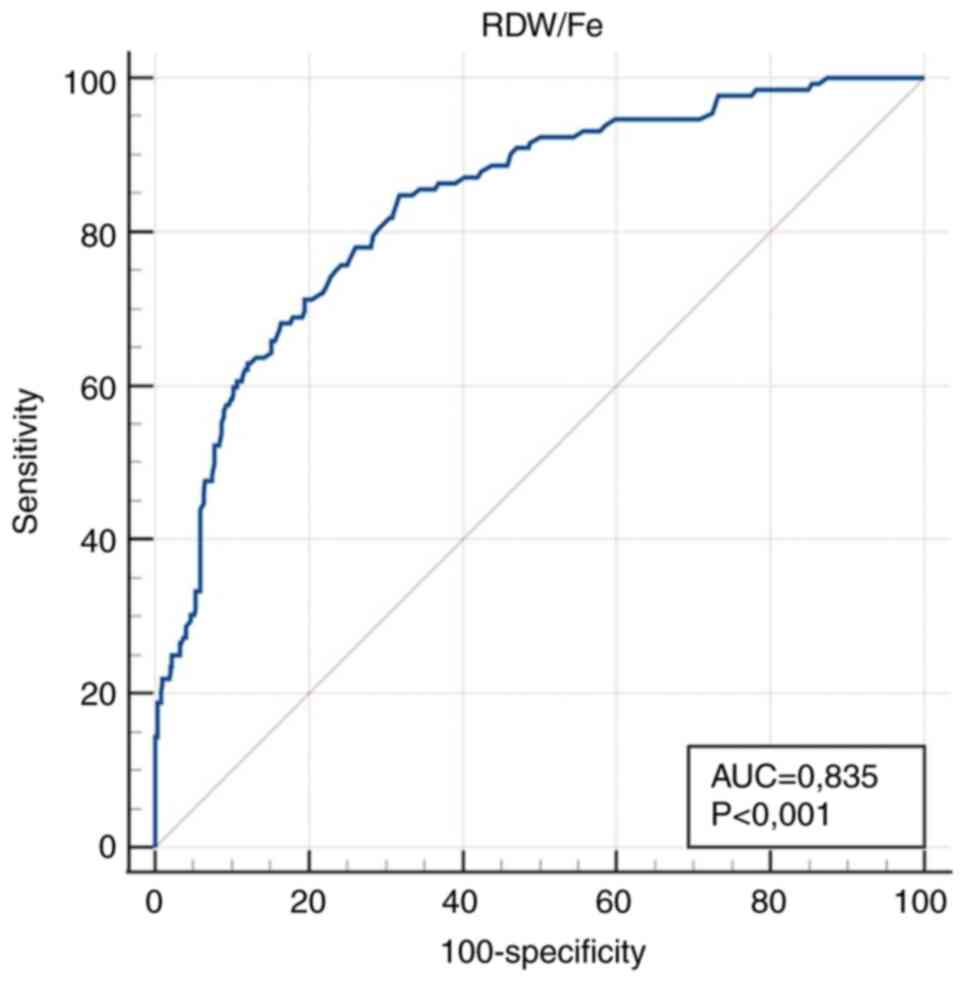

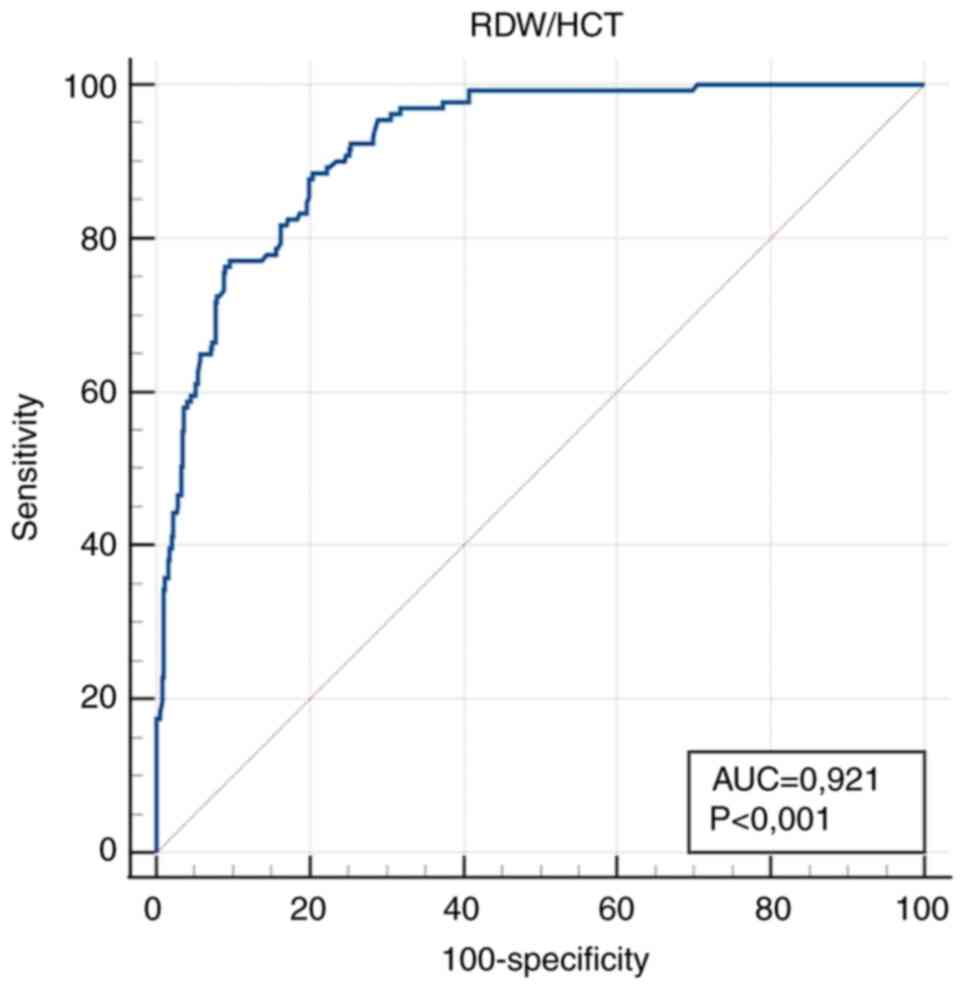

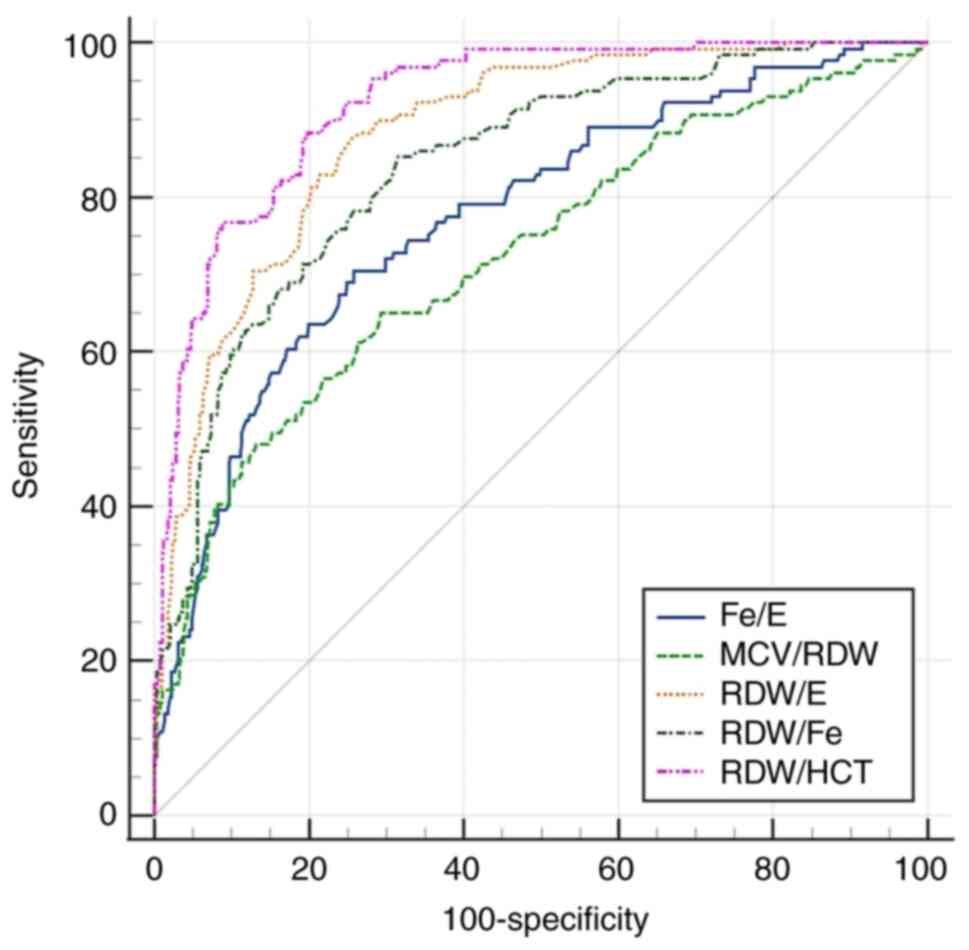

The diagnostic accuracy of the measured values

obtained from the ROC curves for the tested parameters at their

optimal diagnostic cut-off values is presented in Table III.

| Table IIIDiagnostic accuracy of tested

parameters in distinguishing anaemic (n=133) and non-anaemic

(n=490) pregnant women. |

Table III

Diagnostic accuracy of tested

parameters in distinguishing anaemic (n=133) and non-anaemic

(n=490) pregnant women.

| Parameter

(unit) | Area under the

curve (95% CI) | P-value | Cut-off | Sensitivity (95%

CI) | Specificity (95%

CI) |

|---|

| E

(x1012/l) | 0.802

(0.768-0.833) |

<0.001a | ≤3.98 | 73.7

(65.3-80.9) | 75.9

(71.8-79.6) |

| Fe (µmol/l) | 0.824

(0.791-0.853) |

<0.001a | ≤10 | 75.9

(67.8-82.9) | 74.9

(70.8-78.6) |

| HCT (l/l) | 0.973

(0.957-0.984) |

<0.001a | ≤0.32 | 92.5

(86.6-96.3) | 94.7

(92.3-96.5) |

| MCV (fl) | 0.740

(0.704-0.774) |

<0.001a | ≤82.9 | 54.1

(45.3-62.8) | 85.9

(82.5-88.9) |

| RDW (%) | 0.661

(0.622-0.698) |

<0.001a | >14.7 | 60.2

(51.1-68.7) | 66.9

(62.6-71.1) |

| Fe/E (µmol

x10-12) | 0.771

(0.735-0.803) |

<0.001a | ≤2.53 | 70.5

(61.9-78.1) | 73.4

(69.3-77.3) |

| MCV/RDW (fl

x10-2) | 0.722

(0.685-0.756) |

<0.001a | ≤5.8 | 65.4

(56.7-73.4) | 69.9

(65.7-74.0) |

| RDW/E

(%lx10-12) | 0.884

(0.856-0.908) |

<0.001a | >3.63 | 87.8

(80.9-92.9) | 73.9

(69.8-77.8) |

| RDW/Fe

(lx10-2/µmol) | 0.835

(0.804-0.864) |

<0.001a | >1.27 | 84.9

(77.6-90.5) | 68.1

(63.8-72.2) |

| RDW/HCT

(l/lx10-2) | 0.921

(0.897-0.941) |

<0.001a | >43.64 | 88.6

(81.8-93.4) | 79.5

(75.7-83.0) |

Markedly high diagnostic accuracy (AUC value

>0.9) for IDA diagnosis was obtained for RDW/HCT >43.64

l/lx10-2 as a calculated parameter, and HCT ≤0.32 l/l as

a simple parameter. High diagnostic accuracy (0.9> AUC >0.8)

was obtained for RDW/E, RDW/Fe, E and Fe.

The ROC curves for all parameters, both simple and

calculated are shown in Fig. 1,

Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig.

4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig.

7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9 and Fig. 10, and the comparison of all the ROC

curves of all calculated parameters is presented in Fig. 11.

According to the cut-off values of other calculated

and simple parameters, the following numbers and percentages of

anaemic pregnant women were obtained: 223 (36%) for Fe/E, 234 (38%)

for MCV/RDW, 242 (39%) for RDW/E, 267 (43%) for RDW/Fe, 216 (35%)

for E, 224 (36%) for Fe, 141 (23%) for MCV, and 237 (38%) for RDW

(Table SIII).

The components and criteria of our scoring model are

shown in Table IV. According to

the of the scoring model, the following numbers and percentages of

133 anaemic pregnant women were obtained: 0, 0/133 (0%); 1, 3/133

(2%); 2, 14/133 (11%); 3, 20/133 (15%); 4, 34/133 (26%), and 5,

62/133 (47%). For the 490 non-anaemic pregnant women, the numbers

and percentages were as follows: 0, 217/490 (44%); 1, 80/490 (16%);

2, 76/490 (16%); 3, 60/490 (12%); 4, 33/490 (7%), and 5, 24/490

(5%) (Table SIV).

| Table IVComponents and criteria of the

scoring model. |

Table IV

Components and criteria of the

scoring model.

| Component | Criterion | No/Yes |

|---|

| Fe/E (µmol

x10-12) | ≤2.53 | 0/1 |

| MCV/RDW (fl

x10-2) | ≤5.8 | 0/1 |

| RDW/E

(%lx10-12) | >3.63 | 0/1 |

| RDW/Fe

(lx10-2/µmol) | >1.27 | 0/1 |

| RDW/HCT

(l/lx10-2) | >43.64 | 0/1 |

| All | | 0-5 |

Discussion

During pregnancy, women are prone to developing IDA.

Routine laboratory parameters are only effective in detecting

already visible and manifested anaemia (3). Despite the availability of clinical

and laboratory indicators, adverse events may sometimes go

unrecognised in a timely manner, increasing the risk of

complications in both mother and child. The introduction of a

novel, simple and accessible laboratory indicator, either as a

standalone or as part of a summary model, allows timely recognition

and treatment of IDA (14). In the

present study, several calculated parameters were evaluated with

the aim of finding the one with the highest diagnostic accuracy. In

addition to introducing new combined parameters, a scoring model

based on the sum of these parameters was developed, and this model

may facilitate the timely recognition of IDA and help in making

clinical decisions.

The goal of the present study was to develop novel

combined parameters for IDA that demonstrate high diagnostic

accuracy, using simple, routine procedures performed in a standard

medical-biochemical laboratory. Additionally, another goal was to

establish a model that can be successfully applied at different

stages of pregnancy, thereby enabling timely diagnosis and

effective follow-up. The study subjects were pregnant women whose

blood samples were collected either the day before or on the day of

delivery, upon admission to the hospital. This is also a

limitation, as early recognition of IDA is crucial for reducing

complications and improving outcomes. The model that is proposed

requires validation, as the values obtained from the present study

would otherwise be applicable only to our specific sample of 623

pregnant women. When the original sample was divided into training

and validation subsets, the two groups produced statistical results

similar to those of the full sample. Although slight differences

were observed in the validation group during statistical analysis,

it is important to note that the same parameters demonstrated the

highest diagnostic accuracy. It is suggested that the model be

validated using a larger, entirely new cohort of pregnant women,

assessed at various stages of gestational age. The absence of such

validation is also acknowledged as a limitation of our study. The

scoring model presented in Table

IV should also be tested on an entirely independent cohort to

confirm its performance across various stages of the gestational

period, as this remains another limitation of the present

study.

It is hypothesised that the novel indicators are

superior for diagnostic purposes and may have potential for

prediction when applied in early pregnancy or at the initial

stages. The scoring model may be useful for predicting IDA in the

early stages of pregnancy. This will serve as a topic for further

research.

In the present study, RDW/HCT was revealed to be the

most effective parameter with high diagnostic sensitivity and

specificity. Among the simple parameters, HCT exhibited the best

performance. Both parameters showed the strongest correlation with

Hb. The RDW/HCT ratio was influenced by HCT, but compared with RDW

alone, RDW/HCT demonstrated superior diagnostic performance in

terms of greater sensitivity and specificity, as well as stronger

correlation with Hb. The ratio adjusts RDW in relation to the

overall red blood cell mass, highlighting subtle cases in which the

HCT may remain at the lower end of the normal range, while RDW is

disproportionately elevated. This increases sensitivity by

capturing both early anisocytosis and relative reductions in red

cell mass. In this way, a more independent indicator was obtained,

superior to HCT in terms of independence and to RDW in terms of

diagnostic accuracy. According to the available literature, there

were no similar studies with which to compare the findings obtained

in the present study.

While RDW/HCT and HCT were identified as the most

effective parameters, several other combined and simple parameters

also demonstrated good diagnostic performance. As aforementioned,

parameters that exhibited slightly lower AUC with good sensitivity

and specificity were Fe/E, RDW/E, RDW/Fe, E, and Fe. According to

the available literature, there were no studies with which to

compare these results. All combined and simple parameters exhibited

high AUC values, with the exception of RDW.

The values of all tested calculated parameters were

statistically significantly different between the anaemic and

non-anaemic pregnant women, indicating that these parameters were

good indicators of IDA. However, caution should be exercised when

interpreting the results, taking into account the pre-analytical

requirements of certain parameters. It should also be emphasised

that several factors must be considered when making a diagnosis;

laboratory findings are only one part of the process. The patient's

medical history and clinical manifestations, together with

laboratory results, contribute to the overall diagnostic picture.

In the present study, some patients with borderline anaemia were

asymptomatic, exhibiting no signs typically associated with

anaemia. By contrast, other patients presented with symptoms that

correlated with the severity of their anaemia. The patients

reported symptoms such as shortness of breath, rapid heartbeat,

increased fatigue, weakness, headache, dizziness, and poor

concentration (5). Although some of

these complaints may also be attributed to typical pregnancy

symptoms, particularly in the third trimester, laboratory analyses

confirmed anaemia in these patients. Conversely, pregnant women in

the control group who did not have anaemia did not report such

complaints, apart from fatigue and headaches (5), which were sporadic and only mildly

pronounced. It should be emphasised that exclusion criteria were

carefully designed, ensuring that pregnant women with conditions or

illnesses that could contribute to such symptoms were not included

in the study.

According to the reviewed literature, no studies

similar to the present one were identified. Most studies were

conducted during the first, second or third trimesters of pregnancy

(1,3,9,11,15,16,17).

As noted in the introduction, parameters from basic blood count

measurements were combined to determine IDA.

A low Hb concentration is an accepted and

recommended indicator of IDA. Unlike ferritin, Hb reflects

functional Fe but does not provide information regarding Fe stores.

This could explain its reduced ability to distinguish ID,

especially during the early stages. However, Hb, along with the

number of red blood cells and Fe, remains a good late indicator of

ID (18). Red blood cell counts and

Hb concentrations in pregnant women were useful but not entirely

reliable indicators of anaemia, due to physiological changes in

plasma volume and red blood cell mass as well as serum Fe

concentration, which is subject to diurnal variations (12).

The first laboratory indicator of ID is an increase

in RDW, which reflects the variation in the size of E and is a good

marker of anisocytosis. This occurs before anaemia becomes visible.

Often, RDW is elevated while MCV remains within the normal range,

and only with disease progression does MCV decrease (19). In the present study, RDW did not

prove to be a strong enough parameter, but calculated parameters

that included RDW showed notably improved diagnostic accuracy.

Earlier studies have shown that MCV can be used as

an indicator of ID and IDA (3,19).

This aligns with the position of the WHO, that MCV and MCH are the

most sensitive indicators of ID among standard CBC parameters

(19). However, in the present

study, MCV did not exhibit sufficient sensitivity.

As for HCT, it has been shown to have low

distinguishing power for ID but high distinguishing power for IDA.

A possible explanation is the similarity between Hb and HCT in

representing the oxygen-carrying capacity of E. Additionally, HCT

is often included as a parameter in point-of-care testing devices,

allowing for quick determination and reducing the time required for

sample transport to the laboratory (19). In the present study, HCT proved to

be an excellent indicator with high sensitivity and

specificity.

In the present study, a novel scoring model was

developed that was shown to offer an improved tool for identifying

IDA in the cohort, with each component contributing individually.

The criteria for a scoring model and the threshold values for each

component were established. The calculated parameters included in

the score demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity and are

considered superior indicators than the individual parameters

alone. These novel parameters make the score unique for detecting

IDA and have not been previously reported. Furthermore, as the

score increases, so does the probability of IDA. As aforementioned,

each component in the scoring model contributes individually. While

an individual calculated parameter may fall within a reference

range, the sum of the scores may still reflect the presence and

severity of IDA, which is the strength of the scoring model. The

prediction score proposed in the present study showed potential for

routine clinical use in the early detection of IDA.

In a published study by Sultana et al

(3), haematological parameters

(RDW, Hb, MCV, MCH and MCHC) were compared in pregnant women within

the first 20 weeks of pregnancy. The study concluded that RDW

(sensitivity 82.3%, specificity 97.4%) demonstrated the highest

diagnostic value for detecting IDA and was a reliable and useful

parameter. Conversely, in the present study, RDW showed a

sensitivity of 60.2% and a specificity of 66.9%, which may be

attributed to the different gestational ages of the pregnant women

included in the study.

In another study by the same authors (9), RDW, Hb and MCV were compared in all

pregnant women who visited their hospital during pregnancy. Once

again, RDW proved to be the most reliable parameter for determining

IDA. However, in the present study, RDW did not exhibit sufficient

sensitivity and specificity (Table

III).

Rabindrakumar et al (17) evaluated the role of red cell indices

as a screening tool for the early detection of ID in pregnant

women. They concluded that ID could be predicted in the early

stages using Hb and red cell indices, which are much less

expensive. The results of the present study support the conclusions

of the study by Rabindrakumar et al (17).

Bencaiova and Breymann (20) investigated the relationship between

Hb, Fe status and pregnancy outcome during the second trimester.

They concluded that mild anaemia and depleted Fe stores, when

detected early during pregnancy, were not associated with adverse

maternal and perinatal outcomes in women receiving Fe

supplementation. The present study also included pregnant women who

received Fe supplements, and similarly, there was no significant

association between Fe supplementation and adverse maternal

outcomes (21).

In conclusion, it was found that RDW/HCT and HCT had

the highest diagnostic accuracy and can be used in routine practice

for diagnosing IDA. These parameters, alongside the scoring model,

may be used in the clinic to predict maternal IDA based on

parameters obtained from routine blood tests. This would enable

clinicians to diagnose IDA more accurately in pregnant women and

initiate treatment promptly to ensure the best perinatal

outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Distribution of pregnant women by

gravidity.

Classification of anaemic pregnant

women by Hb, HCT and RDW/HCT: Number and percentage.

Classification of anaemic pregnant

women by calculated and simple parameters: Number and

percentage.

Classification of anaemic and

non-anaemic pregnant women by the scoring model: Number and

percentage.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DŽ, AV and TŠ conceived and designed the study. AV,

TŠ and DŽ collected the material and data. DŽ, AV, TB, GJ and LH

performed the data analysis. DŽ wrote the first draft of the

manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript. DŽ, AV and TŠ

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was performed in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the

Clinical Hospital Center Rijeka (Rijeka, Croatia; approval no.

2170-29-02/1-19-2; class, 003-05/19-1/110; approval date, 15 July

2019). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants

for participation in the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Surekha MV, Srinivas M, Balakrishna N and

Kumar PU: Haemoglobin distribution width in predicting iron

deficiency anaemia among healthy pregnant women in third trimester

of pregnancy. IJIRAS. 4:390–395. 2017.

|

|

2

|

Navya KT, Prasad K and Singh BMK: Analysis

of red blood cells from peripheral blood smear images for anemia

detection: A methodological review. Med Biol Eng Comput.

60:2445–2462. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sultana GS, Haque SA, Sultana T, Rahman Q

and Ahmed ANN: Role of red cell distribution width (RDW) in the

detection of iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy within the first

20 weeks of gestation. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 37:102–105.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Garzon S, Cacciato PM, Certelli C,

Salvaggio C, Magliarditi M and Rizzo G: Iron deficiency anemia in

pregnancy: Novel approaches for an old problem. Oman Med J.

35(e166)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Ma M, Zhu M, Zhuo B, Li L, Chen H, Xu L,

Wu Z, Cheng F, Xu L and Yan J: Use of complete blood count for

predicting preterm birth in asymptomatic pregnant women: A

propensity score-matched analysis. J Clin Lab Anal. 34(e23313):

1–8. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Obianeli C, Afifi K, Stanworth S and

Churchill D: . Iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy: A narrative

review from a clinical perspective. Diagnostics.

14(2306)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Breymann C and Huch R: Anemia in pregnancy

and the puerperium. 3rd edition. UNI-MED: Bremen, p46, 2008.

|

|

8

|

Malczewska-Lenczowska J, Orysiak J,

Szczepańska B, Turowski D, Burkhard-Jagodzińska K and Gajewski J:

Reticulocyte and erythrocyte hypochromia markers in detection of

iron deficiency in adolescent female athletes. Biol Sport.

34:111–118. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Sultana GS, Haque SA, Mishu FA, Muttalib

MA and Rahman Q: Prediction of iron deficiency by red cell

distribution width, mean corpuscular volume and haemoglobin

concentration in pregnant women. BIRDEM Med J. 9:111–116. 2019.

|

|

10

|

Celkan TT: What does a hemogram say to us?

Turk Pediatri Ars. 55:103–116. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Vora SM, Messina G and Pavord S: Utility

of erythrocyte indices in identifying iron depletion in pregnancy.

Obstetric Med. 14:23–25. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Guder WG, Narayanan S, Wisser H and Zawta

B: Samples: From the Patient to the Laboratory: The impact of

preanalytical variables on the quality of laboratory results. 3rd

edition. Wiley-VCH GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, 2003.

|

|

13

|

Kumar U, Chandra H, Gupta AK, Singh N and

Chaturvedi J: Role of reticulocyte parameters in anemia of first

trimester pregnancy: A single center observational study. J Lab

Physicians. 12:15–19. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Mayer L, Langer S, Gaće M, Hrabač P,

Šoštarić M, Fijan I, Špacir Prskalo Z, Cvetko A, Periša J,

Štefančić L, et al: Prediction score for complications after

colorectal cancer surgery based on neutrophils/lymphocytes ratio,

percentage of immature granulocytes, IG and IT ratios. Croat J of

Oncology. 47:1–5. 2019.

|

|

15

|

Resseguier AS, Guiguet-Auclair C,

Debost-Legrand A, Serre-Sapin AF, Gerbaud L, Vendittelli F and

Ruivard M: Prediction of iron deficiency anemia in third trimester

of pregnancy based on data in the first trimester: A prospective

cohort study in a high-income country. Nutrients.

14(4091)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Tolunay HE and Elci E: Importance of

haemogram parameters for prediction of the time of birth in women

diagnosed with threatened preterm labour. J Int Med Res. 48:1–8.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Rabindrakumar MSK, Wickramasinghe VP,

Gooneratne L, Arambepola C, Senanayake H and Thoradeniya T: The

role of haematological indices in predicting early iron deficiency

among pregnant women in an urban area of Sri Lanka. BMC Hematol.

18:1–7. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Örgül G, Hakh DA, Özten G, Fadiloğlu E,

Tanacan A and Beksaç MS: First trimester complete blood cell

indices in early and late onset preeclampsia. Turk J Obstet

Gynecol. 16:112–117. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Rivera AKB, Latorre AAE, Nakamura K and

Seino K: Using complete blood count parameters in the diagnosis of

iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in Filipino women. J

Rural Med. 18:79–86. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Bencaiova G and Breymann C: Mild anemia

and pregnancy outcome in a Swiss collective. J Pregnancy 2014: Nov

13, 2014 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

21

|

Shao J, Richards B, Kaciroti N, Zhu B,

Clark KM and Lozoff B: Contribution of iron status at birth to

infant iron status at 9 months: Data from a prospective

maternal-infant birth cohort in China. Eur J Clin Nutr. 75:364–372.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|