Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory

skin disease characterized by keratinocyte hyperproliferation and

infiltration of inflammatory cells, including CD4+ T and

mast cells, into the skin (1).

Although the precise molecular mechanisms underlying psoriasis

pathogenesis are not completely understood, accumulating evidence

highlights a key role for T helper 17 (Th17) cells as the primary

source of IL-17, a key cytokine in psoriasis development (2,3). Th17

cells differentiate from naïve CD4+ T cells primarily in

response to IL-23 through activation of the JAK2/STAT3 signaling

pathway (4,5). Thus, the IL-23/IL-17 axis is key to

the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis (4). During disease onset, proinflammatory

cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-1β promote

abnormal keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation (6). These cytokines suppress keratin 10

expression while upregulating involucrin and keratins 6, 16 and 17,

which serve as molecular markers of psoriatic lesions (7). This dysregulation reflects

keratinocyte activation and contributes to hallmark

histopathological features of psoriasis, including epidermal

hyperplasia, parakeratosis and acanthosis (8).

Although various therapeutic agents for psoriasis

such as methotrexate, cyclosporine, retinoic acid, vitamin D3

analogs and biological agents such as alefacept are widely used, a

definitive cure remains elusive (2,3).

Moreover, long-term use of certain agents, including cyclosporine

and retinoic acid, is associated with significant adverse effects

(9). As a result, alternative

strategies, including combination therapies involving conventional

and biological agents, have been explored. However, these

approaches are limited by cumulative toxicity and safety concerns

(10). Therefore, the development

of novel, safe and effective therapeutic options for psoriasis

remains a clinical need.

Marine algae are regarded as the ‘plant-based

therapy of the future’ due to their abundance of health-promoting

compounds with activity against various diseases and disorders

(11). One of the most notable

components of seaweeds is their high content of sulfated

polysaccharides (SPs). SPs derived from seaweeds exhibit a broad

spectrum of biological activities, including anti-inflammatory,

immunomodulatory, antioxidant and antiviral effects, making them

promising candidates for pharmaceutical and nutraceutical

applications (12). Gracilaria

fisheri, a species commonly found in Thailand, is rich in

sulfated galactan (SG), a type of SP known for its diverse

biological properties, especially its anti-inflammatory and

immunomodulatory effects (13).

Determining molecular characteristics such as molecular weight is

key for enhancing the biological activity of SPs (14). Our previous study prepared low

molecular weight SG (LSG) from G. fisheri and demonstrated

its superior antioxidant activity compared with SG (15). Oligosaccharides derived from G.

fisheri modulate immune responses by inhibiting proinflammatory

cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, which are key mediators in

psoriasis pathogenesis (13).

Moreover, SG has been shown to interfere with signaling pathways

such as NF-κB and JAK/STAT, which serve central roles in the

regulation of inflammatory gene expression (16,17).

Given these properties, LSG derived from G.

fisheri presents a promising candidate for the development of

novel anti-psoriatic agents. The present study employed an

imiquimod (IMQ)-induced psoriasis-like mouse model to evaluate the

therapeutic potential of LSG from G. fisheri.

Materials and methods

LSG

LSG was prepared using a previously established

method (18). SG was isolated from

the red seaweed G. fisheri using a cold-water extraction

method as described by Wongprasert et al (19). SG was stirred in 0.1 M HCl (RCI

Labscan Ltd.; ratio 10:1) for 6 h at room temperature. The mixture

was neutralized to pH 8 and precipitated with 95% ethanol

(RCILabscan). The resulting pellet was collected, re-suspended in

distilled water and dialyzed against distilled water in a dialysis

bag for 24 h. LSG was obtained by freeze-drying overnight at -60˚C.

The chemical structure and molecular weight of LSG were confirmed

by fourier transform infrared (FTIR), nuclear magnetic resonance

(NMR) and gel permeation chromatography (GPC) analyses. LSG (2 mg)

was analyzed using FTIR spectroscopy with an IRAffinity-1S (IR) and

MIRacle 10 (ATR; Shimadzu). The compound was transferred to a film

and analyzed. Spectral baselines were corrected to the 400-4,000

cm-¹ range. For NMR analysis, LSG (10 mg) was dissolved

in deuterium oxide (D2O, 99.9%; 0.5 ml) in 5 mm NMR

tubes and analyzed using a Varian Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer. For

GPC, LSG was dissolved in deionized water (1:1 w/v), and 20 µl of

the solution was analyzed using a Shimadzu LC-20AD system with an

LC-20A oven column and a RID-10A detector, equipped with a TSKgel

Guard PWH Size Exclusion Guard column. The column temperature was

maintained at 60.0±0.1˚C.

Animal model

Male BALB/c mice (n=48; age, 6-8 weeks; average

weight, 23.96±1.34 grams) were purchased from Nomura International

Siam (Bangkok, Thailand). All animals were housed under SPF

conditions with controlled humidity (50-70%), temperature (25±2˚C)

and a 12/12-h light/dark cycle. Mice had free access to a standard

pellet diet and water ad libitum throughout the experiment.

All experimental procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee

of the University of Phayao, Phayao, Thailand (approval no.

1-024-65).

IMQ-induced psoriasis and experimental

design

The dorsal hair of BALB/c mice was removed 1 day

before starting the experiment. IMQ cream (5% IMQ; Aldara™, Ensign

Laboratories Pty Ltd.) was applied daily at a topical dose of 62.5

mg for 7 consecutive days to establish an IMQ-induced psoriasis

mouse model characterized by moderate-to-severe psoriasis-like skin

lesions, including pronounced erythema, scale formation, epidermal

thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration, corresponding to

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores of 2-3 for each

parameter (20,21). MTX was used as a positive control

because it is commonly used as a first-line treatment for

moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (22). The concentration of 5.0 mg/kg LSG

was selected based on previous studies (23,24).

The mice were randomly divided into six groups (n=8/group) as

follows: i) Normal control (NC), mice were intraperitoneally

injected with 200 µl normal saline, followed by the topical

application of petroleum cream (Chemipan Corporation Co., Ltd.);

ii) methotrexate (MTX) control, mice were intraperitoneally

injected with 200 µl 1.0 mg/kg MTX, followed by the topical

application of petroleum cream; iii) LSG control, mice were

intraperitoneally injected with 200 µl 5.0 mg/kg LSG, followed by

the topical application of petroleum cream; iv) IMQ, mice were

intraperitoneally injected with 200 µl normal saline, followed by

the topical application of IMQ cream; v) MTX + IMQ, mice were

intraperitoneally injected with 200 µl 1.0 mg/kg MTX, followed by

the topical application of IMQ cream; and vi) LSG + IMQ, mice were

intraperitoneally injected with 200 µl 5.0 mg/kg LSG, followed by

the topical application of IMQ cream (Fig. S1). After 7 days of treatment, all

mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane in oxygen and maintained

at 1.5-3%, followed by cervical dislocation. The thoracic cavity

was opened, and blood was collected via cardiac puncture. Skin

lesions, lymph nodes, spleen, kidney and liver were harvested for

further analysis.

Assessment of PASI

The severity of skin lesions was assessed using a

modified human scoring system based on PASI (21,25).

Mice were evaluated daily for erythema, scaling and thickening.

Each parameter was scored independently on a scale from 0 to 4 (0,

none; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, marked; 4, obvious; Table I) (21). The cumulative score was used to

evaluate the overall severity of skin inflammation.

| Table IDescriptive Psoriasis Area and

Severity Index scores in a mouse model following imiquimod

induction. |

Table I

Descriptive Psoriasis Area and

Severity Index scores in a mouse model following imiquimod

induction.

| | Score |

|---|

| Sign | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|

| Erythema

(redness) | Normal flesh tone

(faint cuts may be visible but not prominent) | Slight redness over

the skin surface | Noticeable uniform

redness | Pronounced redness

with scattered dark red areas | Intense, dark red

coloration |

| Thickness | No thickening, skin

remains soft and flexible | Mild puckering with

no measurable increase in thickness (~1 mm) | Thickness of 1-2 mm

upon pinching, with ridges visible in some regions | Thickness >2 mm

upon pinching, with ridges easily noticeable | Thickness >2 mm

without pinching; ridges appear tight and distinct |

| Scaling

(desquamation) | No evidence of

flaking | Small, localized

dry spots without peeling | Dry patches

covering most of the surface, with flaking in creases | Moderate flaking

affecting a large portion of the surface | Extensive and

severe flaking over a wide surface area, particularly pronounced

involvement in certain regions |

Body and lymphatic organ weight

Body weight was recorded on days 1, 3, 5 and 7 of

administration. On day 8, the mice were euthanized, and right

axillary lymph nodes and spleens were removed, cleaned and weighed.

The weights of the right axillary lymph nodes and spleens were

normalized to body weight to calculate the organ index.

Histopathological analysis

Skin lesions were collected, fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde for 48 h at 4˚C and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin

blocks were sectioned at 4 µm thickness using a rotary microtome.

Tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated

through a descending graded ethanol series. Sections were stained

with Mayer's hematoxylin (cat. no. 05-06002/L) and Eosin Y

alcoholic solution (cat. no. 05-11007/L; both Bio Optica Milano

SpA). Sections were dehydrated, cleared, mounted and cover slipped

for histopathological observation under a light microscope.

Epidermal and dermal thickness were measured in four randomly

selected areas of view/section at 10X magnification using ImageJ

software version 1.32j (National Institutes of Health). To

visualize blood vessels in the skin lesions, Periodic Acid-Schiff

(PAS) staining was performed using a PAS staining kit (cat. no.

1.01646.0001, Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) according to the

manufacturer's protocol (26).

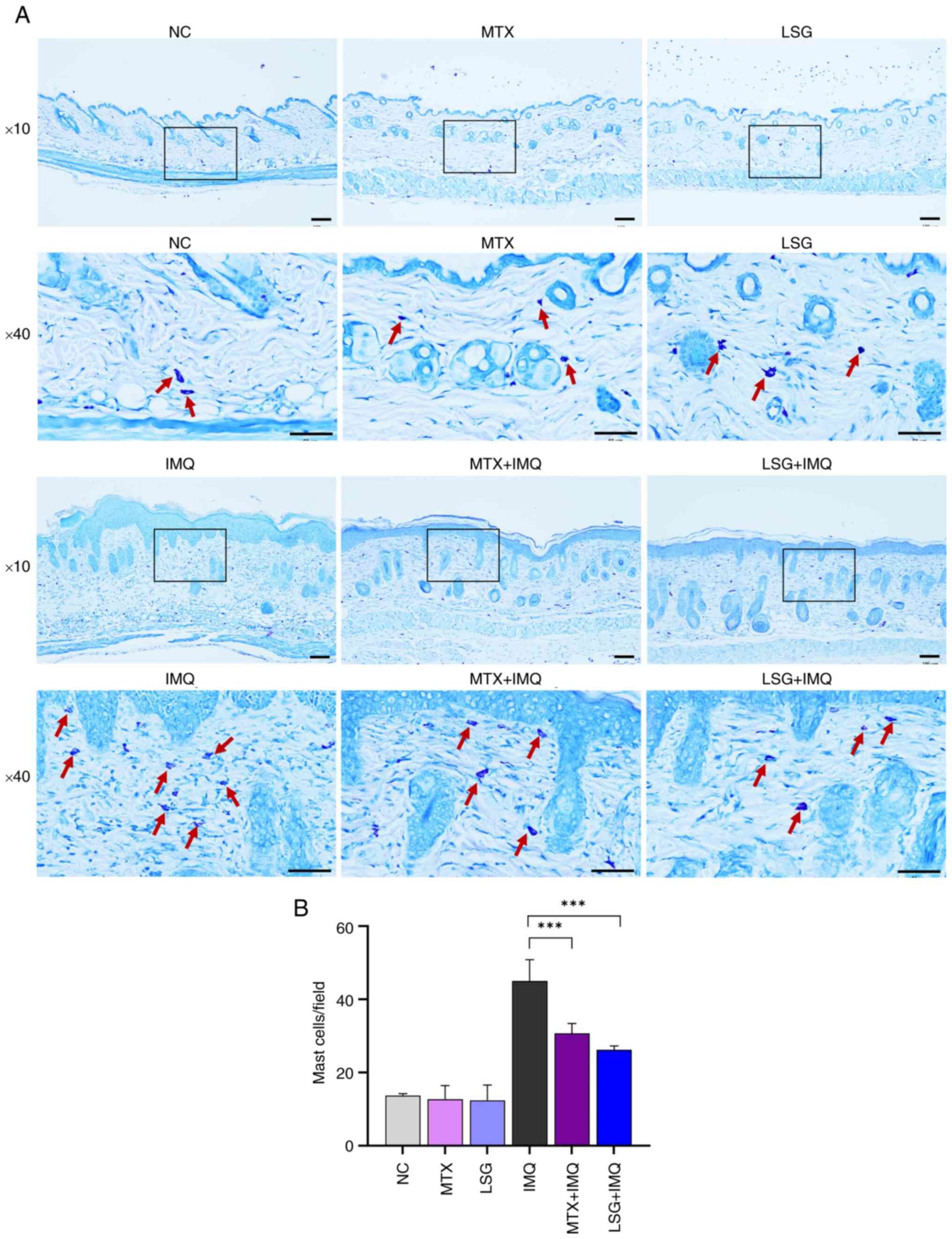

Additionally, Giemsa staining was performed using Giemsa solution

(cat. no. RA-002-05, Biotechnical Co., Ltd.), following the method

described by Pudgerd et al (27). Stained sections were observed and

photographed under a light microscope. Mast cells were counted

manually in four randomly selected fields of view/section at 10X

magnification.

Immunohistochemistry analysis

Skin lesions were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for

48 h at 4˚C and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin blocks were

sectioned at 4 µm thickness. Tissue sections were deparaffinized

with xylene and rehydrated through a descending graded ethanol

series. Tissue sections were incubated in 3%

H2O2 for 15 min to block endogenous

peroxidase activity, followed by antigen retrieval using Tris-EDTA

buffer (pH 9.0) at 100˚C for 20 min, and washed with 1X PBS-T

(0.05% Tween 20). Tissue sections were incubated with protein

blocking solution (0.5% BSA, 0.5% casein in PBS; cat. no. AB64226,

Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were incubated with

primary antibodies against CD4+ (rabbit monoclonal

anti-CD4+, cat. no. ab183685, Abcam; 1:50) and Ki67

(rabbit polyclonal anti-Ki67, cat. no. ab15580, Abcam; 1:100) for 3

h at room temperature. Following washing with 1X PBS-T, sections

were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody

(AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L, cat. no. 111-035-003,

Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.; 1:500) for 1 h at room

temperature. Positive signals were developed using NOVA Red

substrate (cat. no. SK-4800, Vector Laboratories, Inc.; Maravai

LifeSciences) and counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin for 20

sec at room temperature. For quantitative analysis, slides were

imaged at 10X magnification under a light microscope.

CD4+ and Ki67-positive cells were counted manually in

four randomly selected areas of view/section.

Cytokine ELISA

Skin tissue and blood serum samples were collected

to assess cytokine levels using ELISA kits. Dorsal skin was excised

and any attached connective tissue was removed. A 0.1

cm2 section of tissue was homogenized in 1 ml normal

saline using a tissue homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged

at 2,500 x g for 15 min at 4˚C. The supernatant was collected and

stored at -20˚C until analysis. For blood serum, samples were

allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min, followed by

centrifugation at 2,500 x g for 15 min at 4˚C. The serum was

separated and stored at -20˚C until use (27). Cytokine concentrations including

IL-1β (ELISA MAX™ Deluxe Set Mouse IL-1β kit, cat. no. 432604),

TNF-α (cat. no. 430904), IL-17A (cat. no. 432504), and IL-23 (cat.

no. 433704), were measured using commercial ELISA kits, according

to the manufacturer's protocols (all BioLegend, Inc.). Absorbance

was measured at 450 nm using a VersaMax™ microplate reader and data

were analyzed with SoftMax Pro software version 6 (Molecular

Devices, LLC).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q)PCR

Total RNA was extracted from skin tissue using TRI

Reagent® (Molecular Research Center, Inc., cat. no.

TR118) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of 1

µg total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the iScript™

Reverse Transcription Supermix for RT-qPCR (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.; cat. no. 1708840). All RT-qPCR assays were conducted using

the QIAquant Real-Time PCR Thermal Cycler (Qiagen, Inc.) with the

SensiFAST™ SYBR® No-ROX Kit (Bioline, cat. no.

BIO-98050), according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at

95˚C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95˚C for 5 sec, 60˚C for

10 sec of annealing, and 72˚C for 20 sec of extension. Relative

gene expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, keratin 6, 16 and 17, involucrin,

JAK1, 2 and 3, STAT1, 2 and 3, BCL2 and CCND1 was normalized to

β-actin and calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq method (28). Primer sequences for all target genes

are listed in Table II.

| Table IIPrimer sequences. |

Table II

Primer sequences.

| Gene | Primer | Sequence,

5'→3' | Accession no. | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Keratin 6 | Forward |

GTGGCCTCAGCTCTTCTACC | BC080820.1 | (27) |

| | Reverse |

TCTGAGCACGGGATTCTGC | | |

| Keratin 16 | Forward |

TGGATGGCGAGAATATCCACAG | AF064006.1 | (27) |

| | Reverse |

GCTCCTTGAGGATGGACCG | | |

| Keratin 17 | Forward |

GCCCACCTGACTCAGTACAA | BC032161.2 | (27) |

| | Reverse |

GGAGCTGAGTCCTTAACGGG | | |

| Involucrin | Forward |

ATGTCCCATCAACACACACTG | NM_008412.3 | (27) |

| | Reverse |

TGGAGTTGGTTGCTTTGCTTG | | |

| JAK1 | Forward |

CTCCGAACCGAATCATCACT | NM_146145.2 | (55) |

| | Reverse |

GCCGTTTTTCTGCTTCTTTG | | |

| JAK2 | Forward |

TTGTGGTATTACGCCTGTGTATC | L16956.1 | (56) |

| | Reverse |

ATGCCTGGTTGACTCGTCTAT | | |

| JAK3 | Forward |

CCATCACGTTAGACTTTGCCA | L40172.1 | (56) |

| | Reverse |

GGCGGAGAATATAGGTGCCTG | | |

| STAT1 | Forward |

TCACAGTGGTTCGAGCTTCAG | NM_001205313.1 | (56) |

| | Reverse |

GCAAACGAGACATCATAGGCA | | |

| STAT2 | Forward |

TCCTGCCAATGGACGTTCG | NM_019963.2 | (56) |

| | Reverse |

GTCCCACTGGTTCAGTTGGT | | |

| STAT3 | Forward |

AGCAGAATCTCAACTTCAGACC | NM_213660.4 | (57) |

| | Reverse |

TTCGTGGTAAACTGGACACC | | |

| BCL2 | Forward |

AGGAGCAGGTGCCTACAAGA | AH001858.2 | (55) |

| | Reverse |

GCATTTTCCCACCACTGTCT | | |

| CCND1 | Forward |

GCGTACCCTGACACCAATCT | NM_007631.3 | (55) |

| | Reverse |

ATCTCCTTCTGCACGCACTT | | |

| β-actin | Forward |

GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG | NM_007393.5 | (27) |

| | Reverse |

CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT | | |

Western blot analysis

Total protein from skin tissue was extracted using

lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCL, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 100X protease inhibitor solution.

Protein concentration was determined with a NanoDrop 2000

spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A total of 50

µg protein/lane was separated on a 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and

transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked

with 2% BSA (cat. no. 112018, Merck KGaA) in TBS-T (100 mM

Tris-base, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) for 2 h at room temperature

and incubated overnight at 4˚C with primary antibodies (1:1,000)

against mouse anti-Ki67 (cat. no. 14569982, Invitrogen, Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), rabbit anti-TNF-α (cat. no. 3707S), mouse

anti-IL-6 (cat. no. 12019S), rabbit anti-IL-10 (cat. no. 12163S;

all Cell Signaling Technology Inc.) and rabbit anti-β-actin (cat.

no. 4970S, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). After three washes

with TBS-T for 10 min each, the membranes were incubated with

HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000; cat. nos. 31460 and

626520; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1 h at room

temperature. Membranes were washed with TBS-T and immunoreactivity

was visualized using the Clarity™ Western ECL substrate kit

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Protein bands were detected using the

Amersham™ ImageQuant™ 800 biomolecular imager (Cytiva). Relative

protein expression was quantified using ImageJ software version

1.32j (National Institutes of Health), with band intensities

normalized to β-actin.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SD of triplicate

experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA

followed by Tukey's post hoc multiple comparison test. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism

software, version 10.3.1.509 (Dotmatics).

Results

Effect of LSG on psoriatic skin

lesions in IMQ-induced mouse model of psoriasis

LSG had a molecular weight of 7.87 kDa and consisted

of complex structures with alternating 3-linked β-D-galactopyranose

and 4-linked 3,6-anhydro-α-L-galactopyranose or

α-L-galactopyranose-6- sulfate units (Fig. S2) (18).

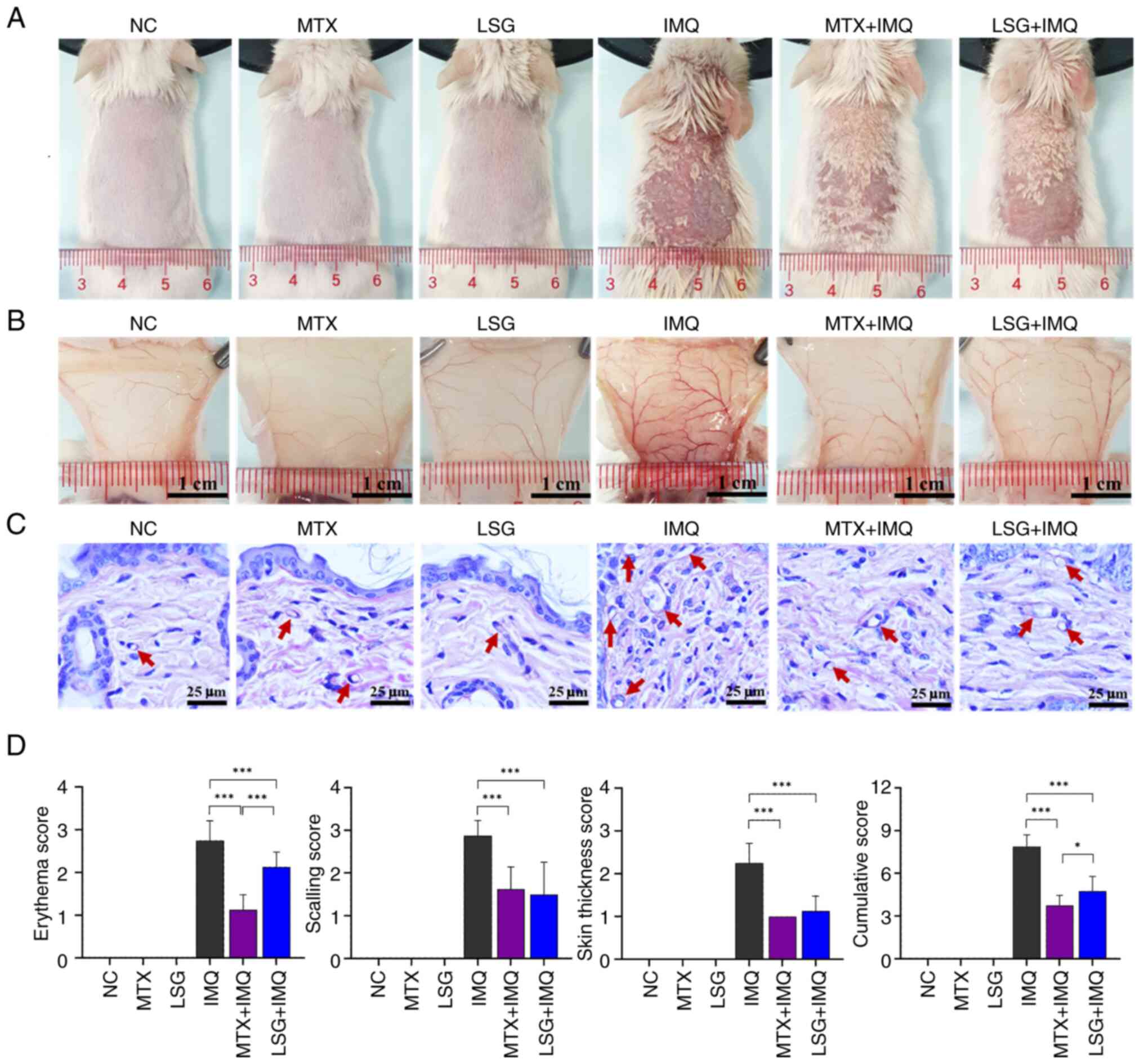

To investigate whether LSG ameliorated skin lesions

in psoriasis, IMQ was applied to induce a psoriasis-like mouse

model, with and without LSG treatment, and compared with MTX

treatment. Mice treated with IMQ exhibited rapid proliferation of

immune cells and keratinocytes, leading to increased cytokine

production. This mimics the features of human plaque psoriasis,

which is characterized by erythema, skin thickening, scaling, and

epidermal changes associated with increased inflammation and

vascular alterations (29).

Symptoms of the psoriatic condition were observed over 7 days of

continuous IMQ application in the IMQ group. However, LSG + IMQ

group showed a decrease in IMQ-induced psoriatic traits, similar to

MTX + IMQ group (Figs. 1A and

S3).

Subcutaneous vasculature in the lesional area was

visualized post-mortem to evaluate inflammatory angiogenesis. Mice

in the IMQ group displayed dense and complex vascular networks,

characterized by prominent branching and bifurcation, indicative of

increased neovascularization and vascular remodeling commonly

associated with psoriatic inflammation (8,29). By

contrast, both the MTX + IMQ and LSG + IMQ groups exhibited

decreased vascular complexity, suggesting that these treatments

effectively suppressed IMQ-induced angiogenic responses. NC, MTX

and LSG groups exhibited sparse and minimally branched vasculature,

consistent with normal skin lacking inflammatory stimulation

(Fig. 1B and C).

PASI scores were calculated to provide a qualitative

assessment of disease progression and therapeutic efficacy

(Figs. 1D and S4). Mice in the LSG + IMQ group showed

significantly lower PASI scores in all parameters compared with the

IMQ group, indicating a marked decrease in psoriatic severity.

There were significant differences between the LSG + IMQ and MTX +

IMQ groups. Collectively, the PASI data supported the protective

effect of LSG against IMQ-induced psoriatic skin inflammation.

Psoriatic mice treated with LSG

exhibit decreased keratinocyte proliferation and

differentiation

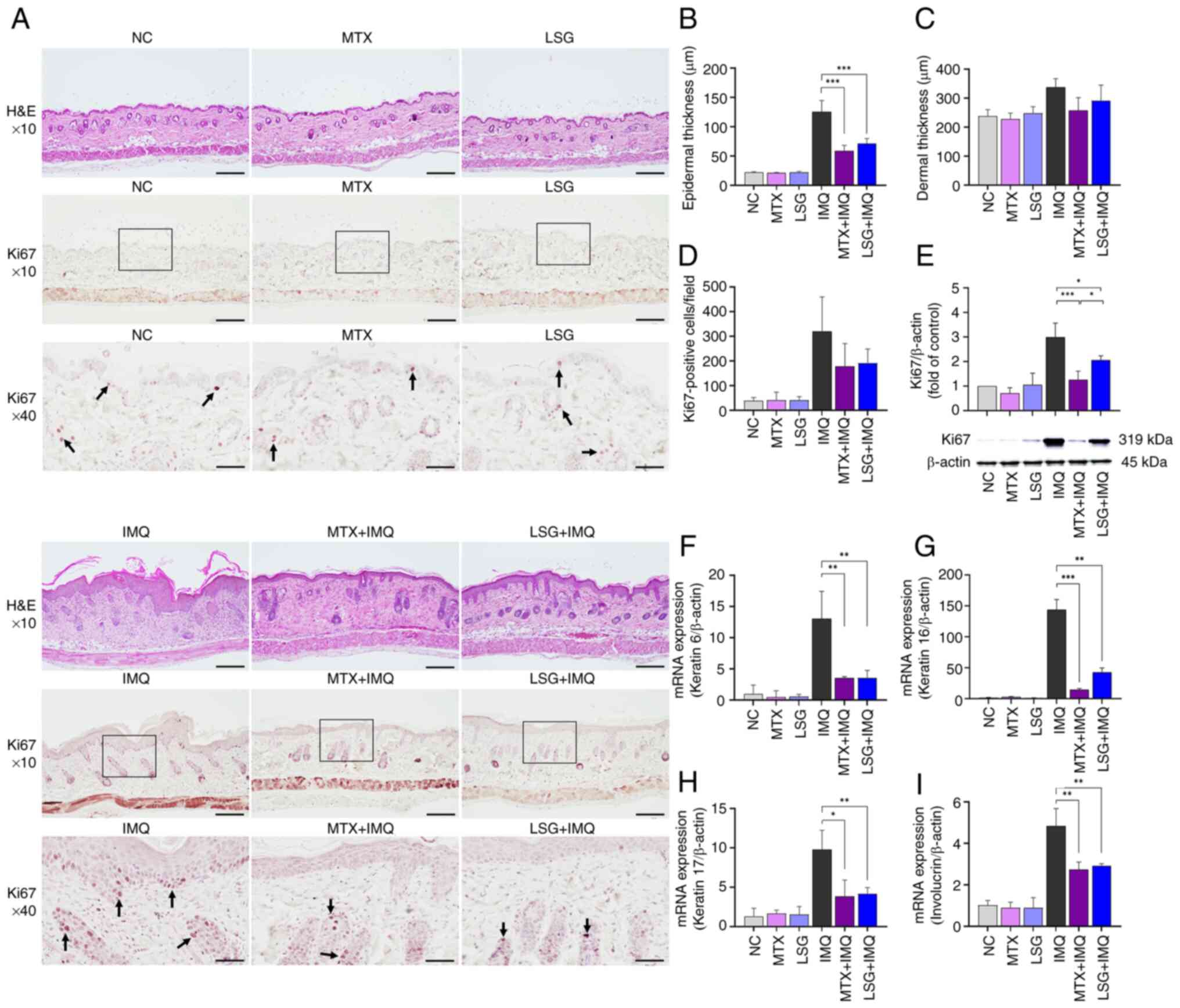

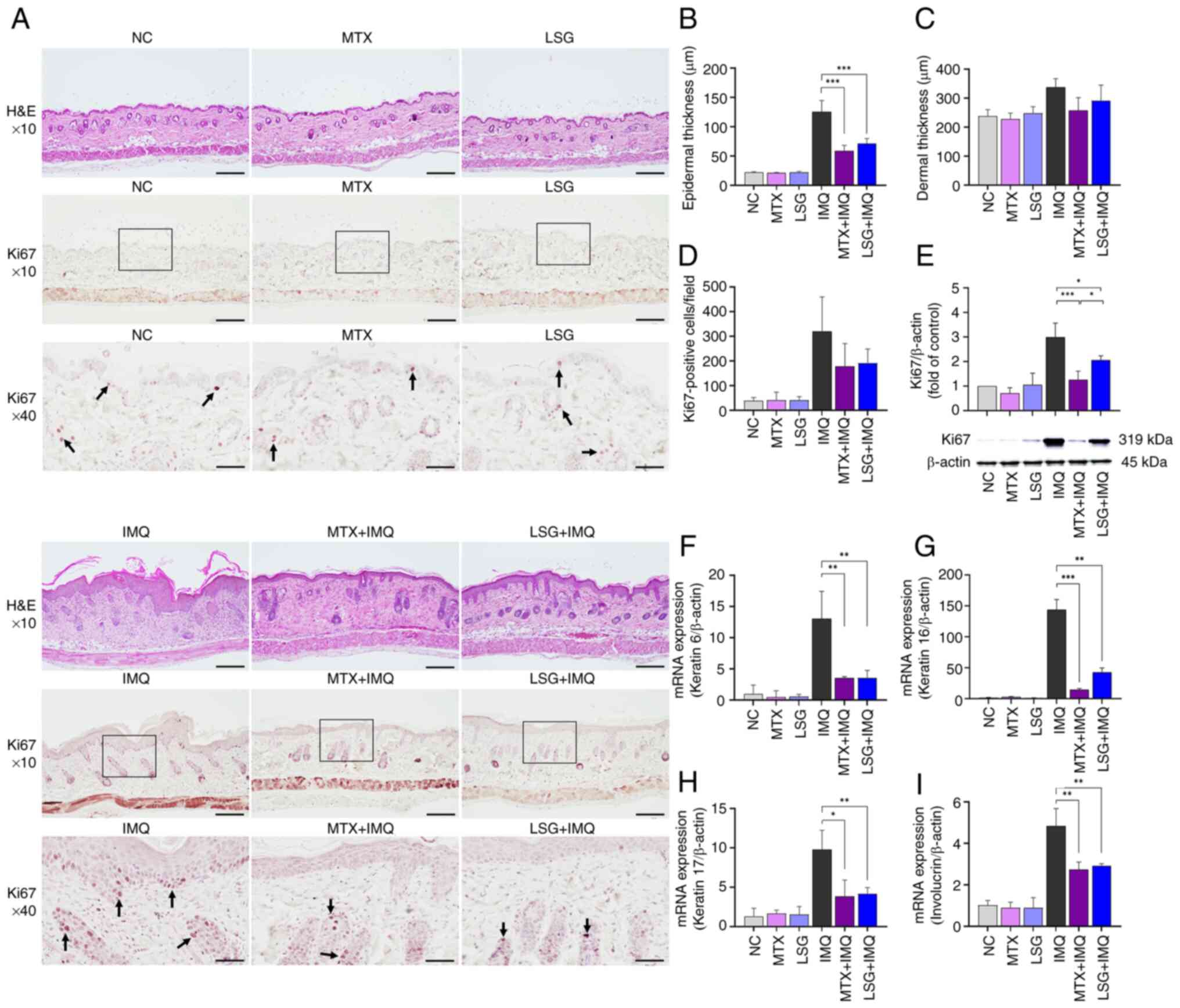

Histopathological analysis of dorsal skin was

performed to evaluate the effect of LSG in IMQ-induced psoriasis.

Mice in the IMQ group developed typical psoriasis-like changes,

including hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis and thickening of the

epidermal stratum spinosum, whereas the LSG + IMQ group showed

decreased psoriasis-like alterations (Fig. 2A). Quantitative analysis confirmed

that epidermal thickness was significantly decreased in the LSG +

IMQ group compared with the IMQ group (Fig. 2B). No significant difference in

epidermal thickness was observed between the LSG + IMQ and MTX +

IMQ groups. Although dermal thickness did not differ significantly

between the IMQ-treated groups, both the MTX + IMQ and LSG + IMQ

groups showed decreased dermal thickness compared with the IMQ

group (Fig. 2C).

| Figure 2Effect of LSG on keratinocyte

proliferation and differentiation. (A) Representative

H&E-stained sections and Ki67 immunostaining of dorsal skin.

Arrows indicate Ki67-positive cells. Magnification, x10 (scale bar,

200 µm) and x40 (scale bar, 50 µm). Quantification of (B) epidermal

and (C) dermal thickness and (D) Ki67-positive cells (n=8). (E)

Ki67 protein expression assessed by western blot and quantified

relative to β-actin (n=3). Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

analysis of keratinocyte differentiation markers keratin (F) 6, (G)

16 and (H) 17 and (I) involucrin (n=4). *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. LSG, low

molecular weight sulfated galactan; H&E, Hematoxylin and Eosin;

NC, Normal control; MTX, Methotrexate; IMQ, Imiquimod. |

Epidermal thickening in psoriasis results from

increased keratinocyte proliferation, with Ki67 serving as a

proliferation marker (30).

Immunohistochemistry showed fewer Ki67-positive cells in the

epidermis of the MTX + IMQ and LSG + IMQ groups compared with the

IMQ group (Fig. 2A and D). Ki67 protein expression was

significantly decreased in the LSG + IMQ compared with the IMQ

group (Fig. 2E). To assess

keratinocyte differentiation, the expression of keratin 6, 16 and

17 and involucrin (established biomarkers of keratinocyte

differentiation) (7) was evaluated

by RT-qPCR. Expression levels of keratin 6, 16 and 17 were

significantly decreased in the LSG + IMQ compared with the IMQ

group. No significant differences were observed between the LSG +

IMQ and MTX + IMQ groups (Fig.

2F-H). Expression of involucrin, a structural protein involved

in psoriatic plaque formation, was also decreased in the LSG + IMQ

group compared with the IMQ group (Fig.

2I). Taken together, these findings indicated that LSG

treatment reduces keratinocyte proliferation and

differentiation.

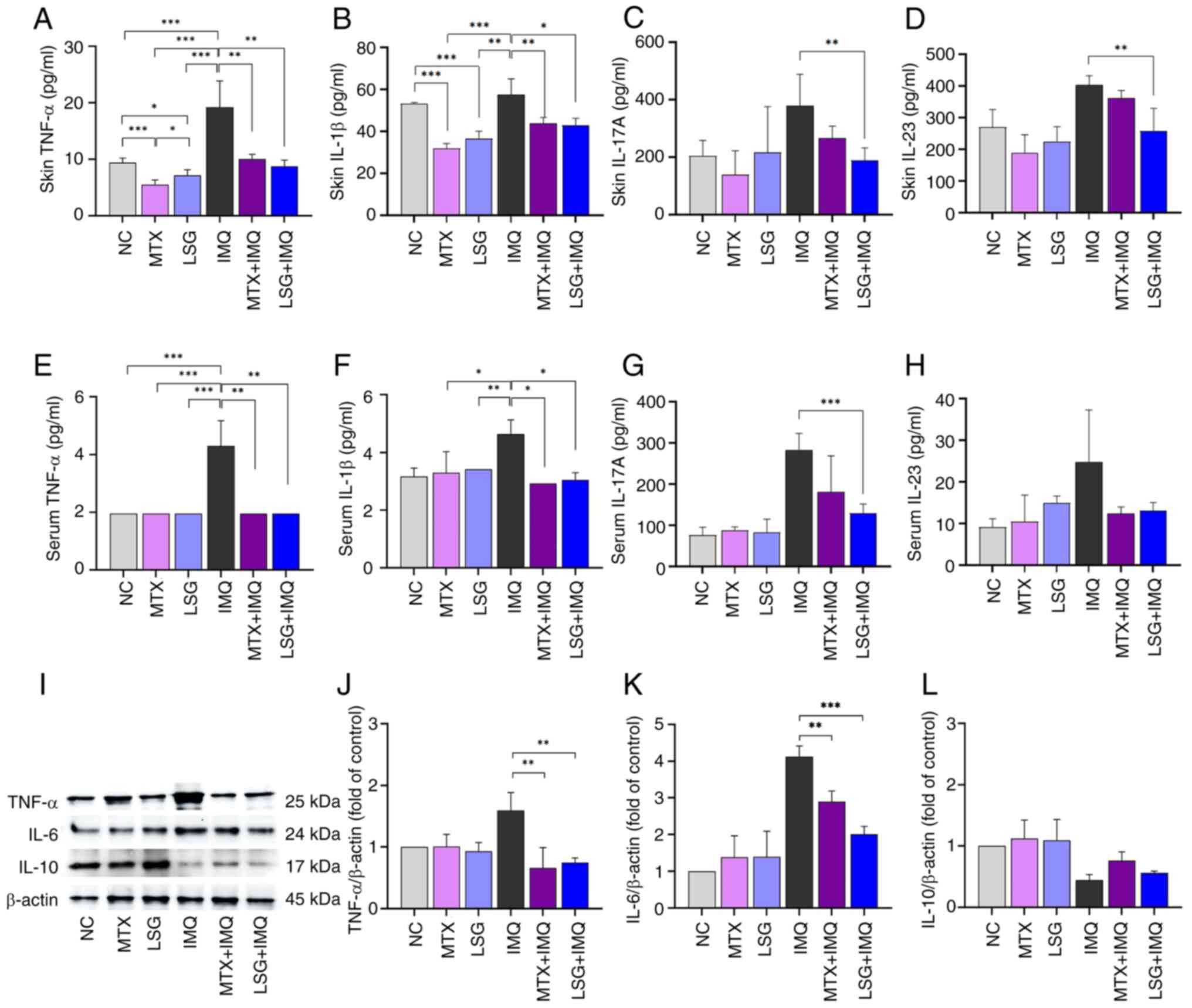

LSG decreases cutaneous inflammation

in IMQ-induced psoriatic mice

Psoriasis is a T cell-mediated autoimmune skin

disease characterized by overexpression of proinflammatory

cytokines (31). TNF-α and IL-1β

serve key roles in regulating inflammation and promoting Th17 cell

development, which is central to the pathogenesis of psoriasis

(32). In addition, IL-23 activates

CD4+ T cells and promotes the release of IL-17A, which

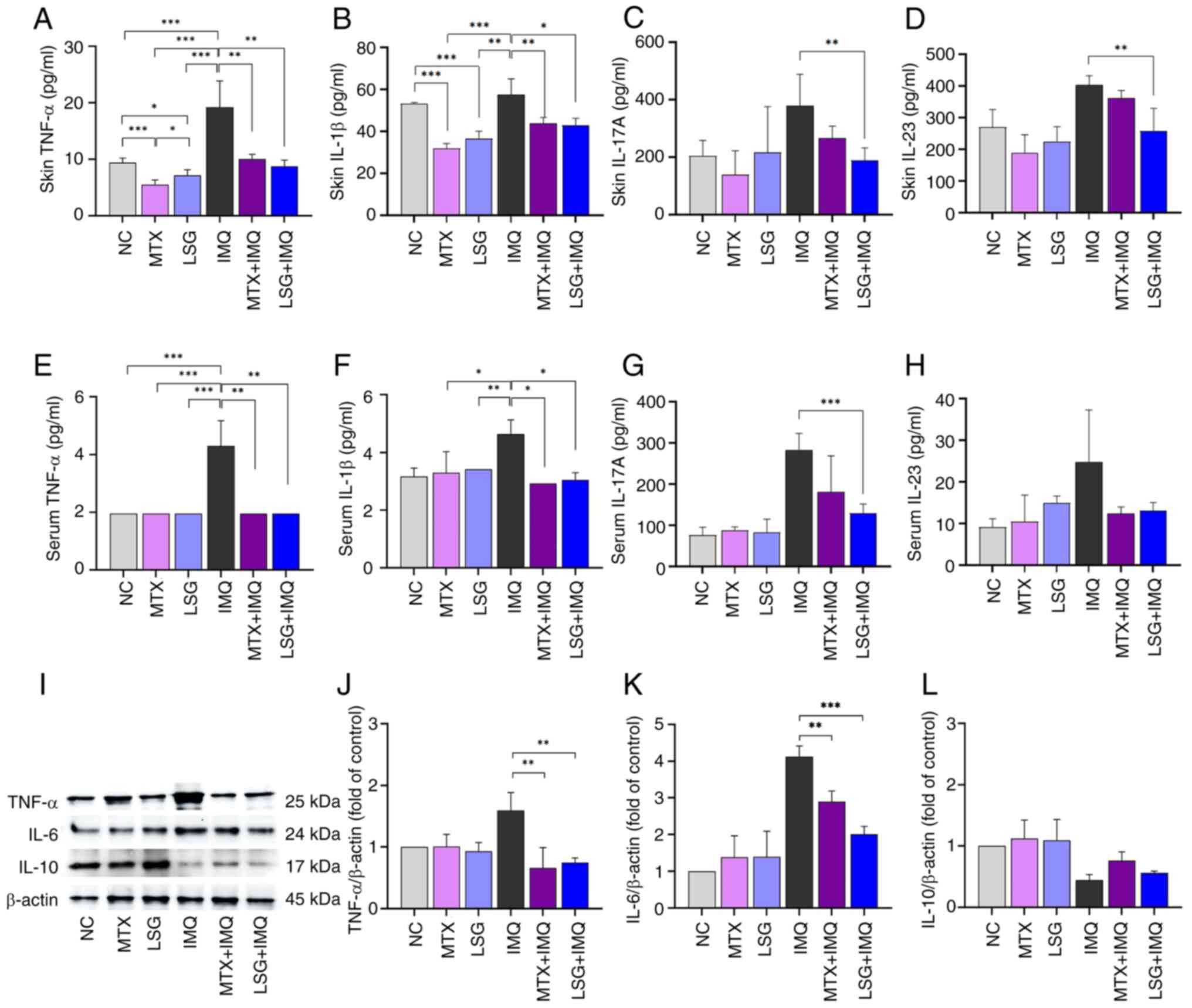

drives keratinocyte proliferation in psoriasis (4). ELISA and western blot analyses were

performed to determine whether LSG modulates inflammatory cytokine

expression during psoriasis development. ELISA showed that levels

of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-17A, and IL-23 were significantly decreased in

the skin lesions of the LSG + IMQ group compared with the IMQ

group. These effects were consistent with those observed in the MTX

+ IMQ group (Fig. 3A-H). Western

blotting further demonstrated that protein expression of TNF-α and

IL-6 proinflammatory cytokines was significantly decreased in the

LSG + IMQ compared with the IMQ group. By contrast, IL-10, an

anti-inflammatory cytokine, showed increased expression in the LSG

+ IMQ group (Fig. 3I-L). These

findings highlight the efficacy of LSG in attenuating cutaneous

inflammation in psoriatic mice.

| Figure 3Effect of LSG on cutaneous

inflammation in IMQ-induced psoriatic mice. Cytokine levels in skin

tissue and blood serum were evaluated by ELISA and western blotting

(n=5). ELISA quantification of (A) TNF-α, (B) IL-1β, (C) IL-17A and

(D) IL-23 in skin tissue. Serum levels of (E) TNF-α, (F) IL-1β, (G)

IL-17A and (H) IL-23. (I) Protein expression of (J) TNF-α, (K) IL-6

and (L) IL-10 in skin tissue, normalized to β-actin.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. LSG, Low molecular weight sulfated

galactan; NC, Normal control; MTX, methotrexate; IMQ,

Imiquimod. |

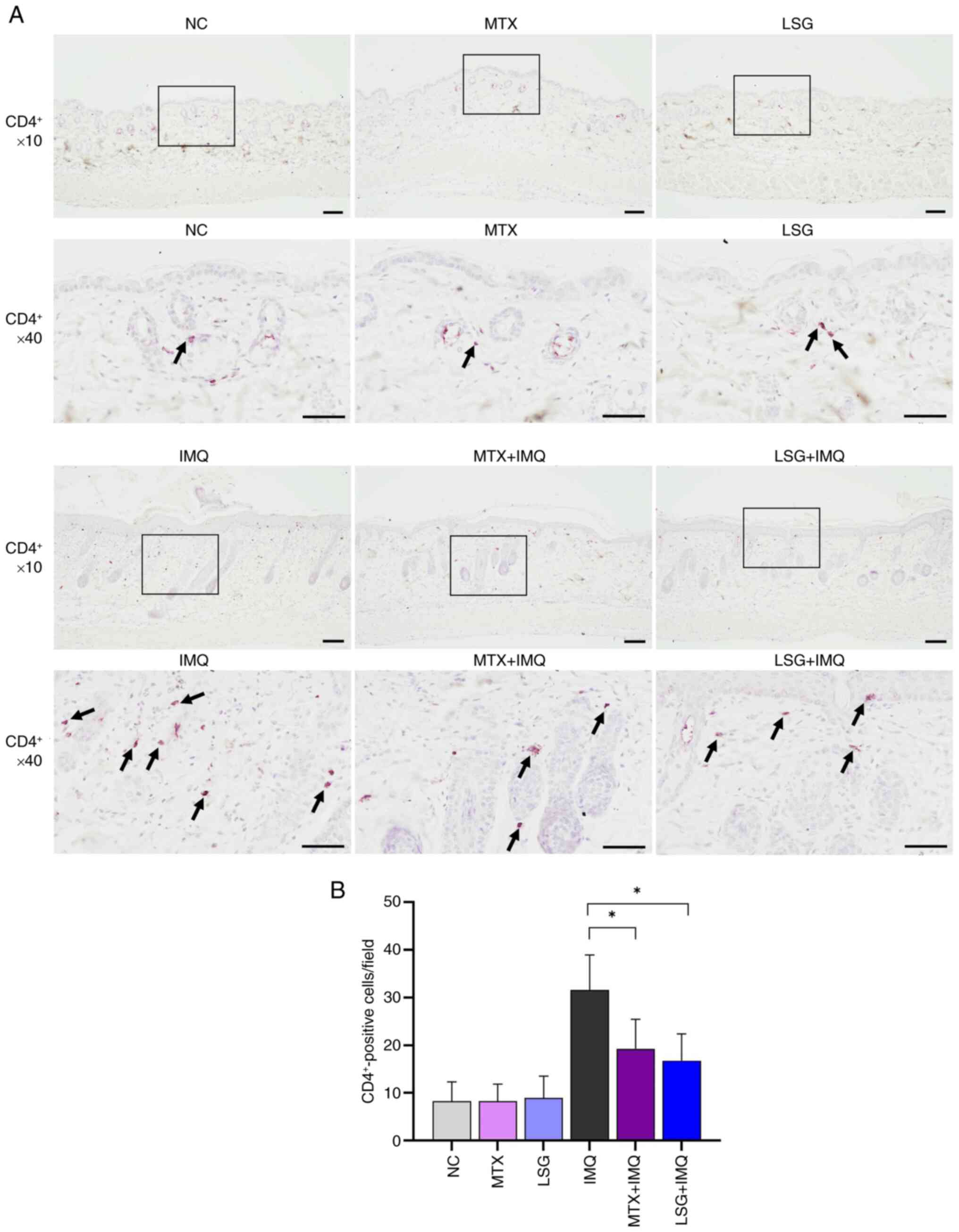

LSG decreases CD4+ and mast

cell recruitment in IMQ-induced psoriatic mice

By reducing levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17A, LSG

decreased the recruitment of inflammatory Th17 cells. To assess the

effect of LSG on inflammatory cell infiltration in psoriatic skin

lesions, immunohistochemical staining for CD4+ cells was

performed. IMQ group demonstrated accumulation of CD4+

cells in psoriatic skin lesions. By contrast, CD4+ cell

infiltration was significantly decreased in both the MTX + IMQ and

LSG + IMQ groups compared with the IMQ group (Fig. 4A and B). Giemsa staining of skin sections

revealed that mast cell infiltration was significantly lower in the

MTX + IMQ and LSG + IMQ groups compared with the IMQ group

(Fig. 5A and B). These findings suggested that LSG

reduces inflammatory cell infiltration in psoriatic skin.

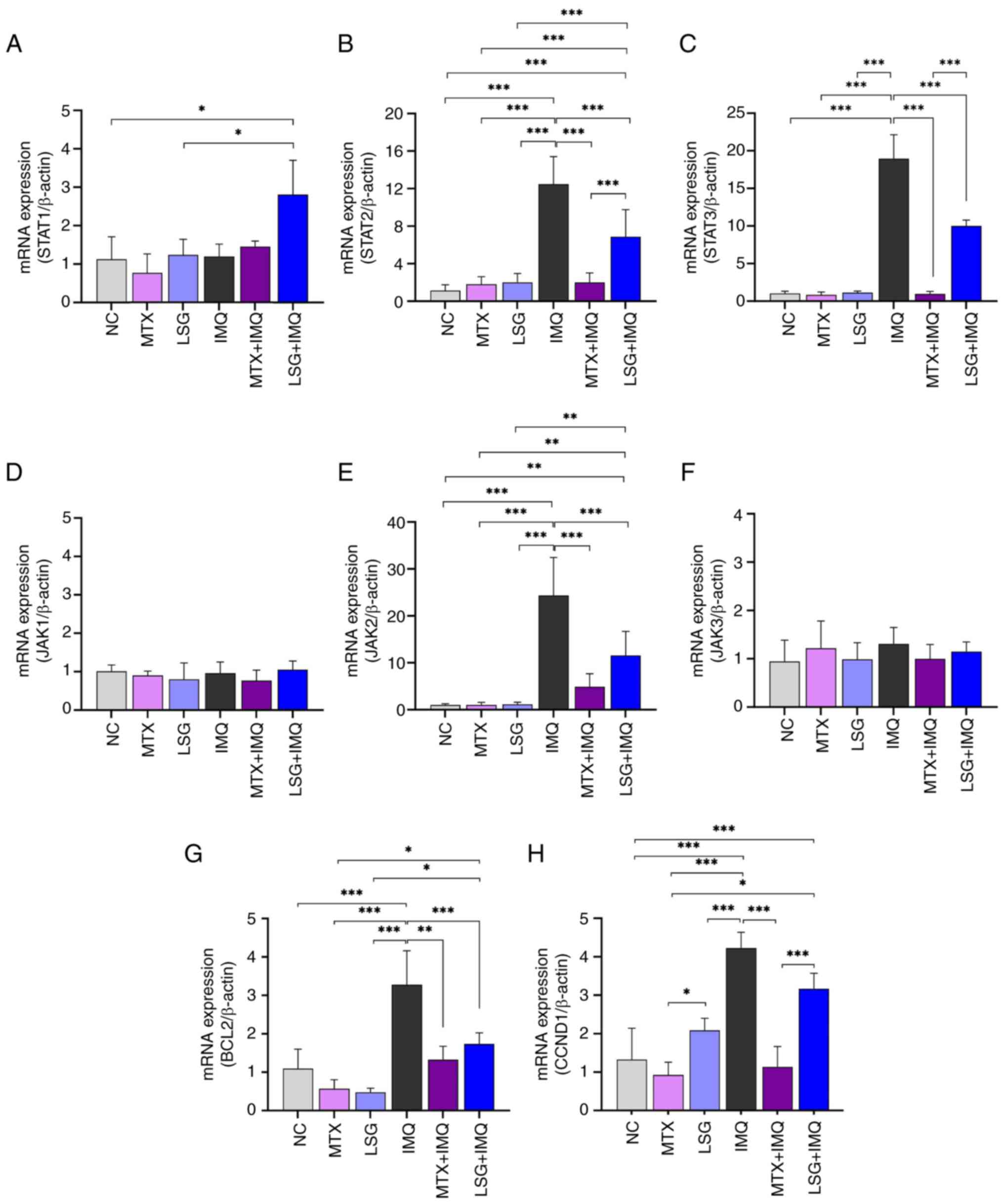

LSG alleviates inflammatory cytokine

production by inhibiting the JAK/STAT pathway in IMQ-induced

psoriatic mice

Proinflammatory cytokines are mediated by IL-17A and

IL-23 via activation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway (5). The decreased expression of IL-17A and

IL-23 in the LSG + IMQ group may affect JAK/STAT pathway

activation. To investigate this, RT-qPCR was used to analyze

mRNA expression of JAK/STAT pathway components, demonstrating

downregulation of JAK2, STAT2 and STAT3 (Fig. 6A-F). Consistent with these findings,

expression of the JAK/STAT target genes BCL2 and CCND1 was also

decreased in the LSG + IMQ group to similar levels observed in the

MTX + IMQ group, compared with the IMQ group (Fig. 6G and H).

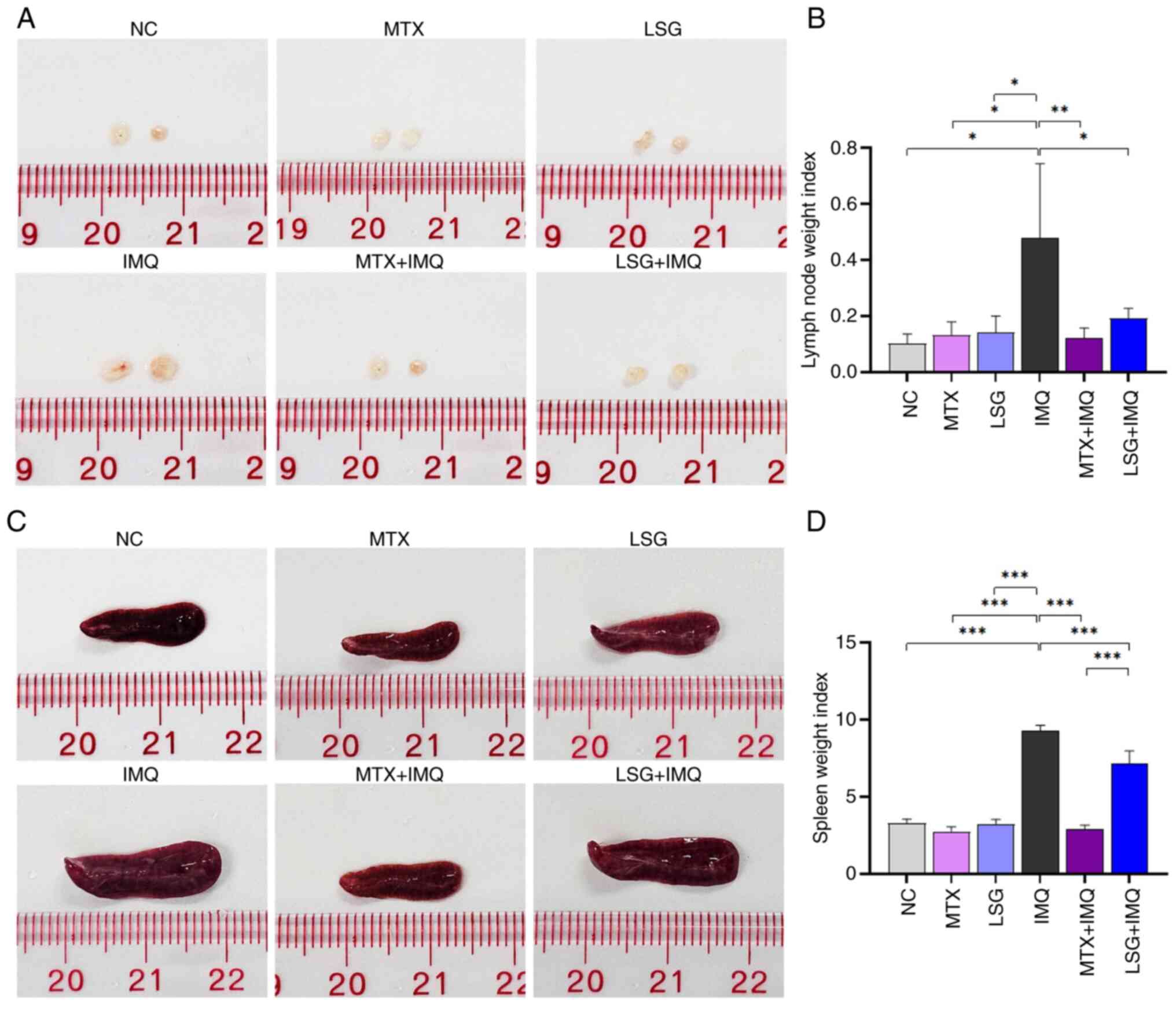

LSG suppresses IMQ-induced enlargement

of lymph node and spleen without causing toxicity to other vital

organs

Psoriasis, as an inflammatory disease, leads to

immune system activation and is associated with increased lymph

node and spleen weight (33). To

assess systemic inflammation, lymph nodes and spleens were

collected and weighed. IMQ treatment resulted in increased size and

weight of lymph nodes and spleens in the IMQ group compared with

controls (NC, MTX, and LSG; Fig.

7). By contrast, the LSG + IMQ group showed a significant

decrease in both lymph node (Fig.

7A and B) and spleen (Fig. 7C and D) size and weight compared with the IMQ

group. No significant differences were observed between the MTX +

IMQ and LSG + IMQ groups. These findings suggested LSG decreased

systemic inflammation by suppressing IMQ-induced organomegaly.

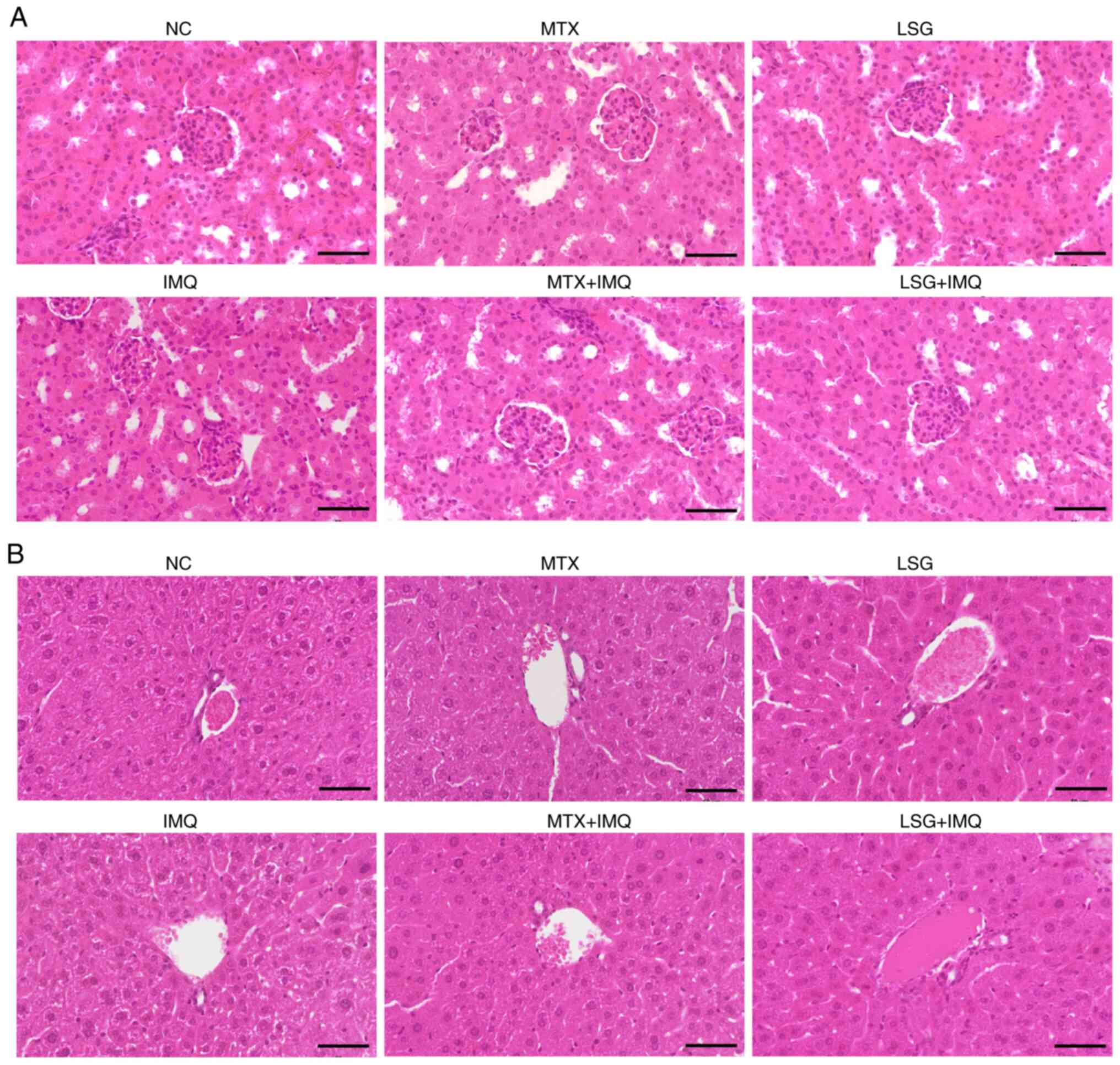

To evaluate the potential toxicity of LSG on major

internal organs, histopathological examination of the kidney and

liver was performed using H&E staining (Fig. 8). Representative micrographs of

renal (Fig. 8A) and hepatic tissue

(Fig. 8B) showed preserved normal

architecture without evidence of degeneration, necrosis,

inflammatory infiltration or vascular congestion. Renal histology

revealed intact glomeruli and renal tubules with no morphological

abnormalities across all groups, including those receiving MTX or

LSG with or without IMQ. Similarly, hepatic tissue exhibited normal

lobular architecture with well-preserved hepatocyte morphology and

no signs of hepatocellular damage. These findings suggested that

LSG at the administered dose did not induce detectable hepatic or

renal toxicity in IMQ-induced psoriatic mice, supporting its safety

for systemic use.

Discussion

There is increasing research on seaweed-derived SPs

for the treatment of numerous ailments (11,12),

particularly inflammatory conditions, due to their efficacy and

minimal side effects. Studies have shown that oligosaccharides

derived from G. fisheri modulate immune responses by

inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, key

mediators in psoriasis pathogenesis (13,34).

Furthermore, modification of SG to obtain LSG from G.

fisheri has been found to significantly enhance its biological

activity (15,18). To the best of our knowledge, the

present study is the first to provide in vivo evidence that

intraperitoneal administration of LSG exerts potent

anti-inflammatory and anti-psoriatic effects in an IMQ-induced

psoriasis-like mouse model. Administration methods include oral,

injectable and topical routes. Intraperitoneal administration

allows rapid absorption of large volumes of substances and is the

preferred injection route for non-irritant, isotonic solutions

(35). Numerous studies have

investigated the intraperitoneal injection of polysaccharides for

their anti-inflammatory and anti-psoriatic effects (23,36,37).

For example, psoriatic mice that received β-glucan

intraperitoneally show decreased psoriatic arthritis-like symptoms

(23). In another study, mice

treated with intraperitoneal acitretin-dextran nanoparticles for

six consecutive days exhibited amelioration of psoriasis-like skin

disease (36). Additionally, the

intraperitoneal injection of fucoidans at doses of 10, 50 and 250

mg/kg significantly reduced inflammation induced by sodium

carboxymethyl cellulose in mice (37).

The IMQ-induced psoriasis animal model is used as it

replicates key features of human psoriatic lesions, including

epidermal thickening, erythema, scaling, vascular proliferation and

infiltration of T and other immune cells (38). The PASI score is a standard tool for

evaluating disease severity and treatment response, with a

reduction >50% generally considered a significant improvement

(39). Administration of LSG

significantly decreased erythema, scaling and skin thickening, as

reflected by decreased PASI scores throughout the treatment period,

indicating its anti-psoriatic effect. An additional factor that may

have influenced lesion severity was hair regrowth during IMQ

application. New hair growth appeared earlier in certain treatment

groups, particularly in IMQ group, which decreased the effective

skin surface area directly exposed to IMQ. Nevertheless, the

overall amount of IMQ applied and the treated area remained

unchanged; some of the compound may have initially adhered to the

hair shafts. However, as the hair was relatively short, the drug

was still able to permeate the skin over time. This was supported

by the observation that the mice exhibited itching and scratching

in these regions, similar to the areas without hair. However, to

maintain a fully exposed dorsal skin surface for photographic

observation, mice in control groups were re-shaved mid-protocol,

whereas IMQ-treated groups were not re-shaved to avoid additional

irritation. Hair regrowth in treated groups may also indicate a

biological effect of the intervention. IMQ is associated with the

activation of Th17 cells, leading to skin inflammation (40), while at the same time Th17-mediated

mechanisms have been implicated in alopecia areata (41). The earlier reappearance of hair in

treatment groups compared with untreated controls suggests that the

treatment may have alleviated local inflammation and restored a

skin microenvironment permissive for hair growth. Although hair

regrowth was not quantitatively assessed, this supports the

hypothesis that the therapeutic regimens not only attenuate

psoriasiform inflammation but may also promote recovery of skin

homeostasis. Future studies incorporating both surface area control

and systematic monitoring of hair regrowth may clarify the dual

role of this phenomenon. Histopathological and immunohistochemical

staining (Ki67 and CD4+) supported these findings,

showing attenuated epidermal hyperplasia, normalized epidermal

architecture and decreased vascular development and infiltration of

inflammatory cells, including CD4+ T and mast cells in

the dermis (27). In psoriatic

lesions, CD4+ T cells are typically concentrated in the

upper dermis (31). Mast cells also

serve a key role in the development and progression of psoriasis,

with increased infiltration contributing to heightened inflammation

(42). The decrease in dermal

CD4+ T and mast cells following LSG treatment suggested

LSG may help inhibit disease progression.

Ki67 is a protein used as a marker of cell

proliferation, particularly to assess keratinocyte activity in skin

conditions (43). In healthy skin,

Ki67 expression is typically low but increases in conditions

involving active keratinocyte division, such as wound healing or

inflammatory skin disorders such as psoriasis (44). Previous studies have shown that Ki67

upregulation in psoriatic epidermis is decreased following

treatment with acitretin-conjugated dextran, MTX and oxymatrine

(36,45). Consistent with these findings, the

present results demonstrated that LSG significantly reduced both

the number of Ki67-positive cells and overall Ki67 expression in

IMQ-induced psoriatic mice. These effects were comparable with

those observed with MTX, a standard anti-psoriatic agent.

Additional biomarkers associated with keratinocyte proliferation

and differentiation in psoriasis include keratin 6, 16 and 17 and

involucrin (7). In the present

study, IMQ-induced upregulation of keratin 6, 16 and 17 and

involucrin was significantly decreased following LSG treatment.

This aligns with previous work demonstrating that

tryptophol-containing emulgel, a topical drug delivery system that

combines the properties of an emulsion and a gel, ameliorates

IMQ-induced psoriasis in mice by reducing the expression of these

markers (27).

The pathogenesis and progression of psoriasis

involve the activation of immune cells, including T and

antigen-presenting cells. Among these, Th cells, particularly Th1

and Th17 subsets, serve a key role in driving the immunological

alterations characteristic of the disease (46). Activation of Th1 and Th17 cells

leads to the aberrant production of proinflammatory cytokines such

as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-17A, IL-23 and IL-6, all of which are key

mediators in psoriasis (6). In

IMQ-induced psoriatic mice, LSG exhibited immunomodulatory effects

by decreasing both systemic and cutaneous levels of TNF-α, IL-1β,

IL-17A, IL-23 and IL-6 (a key cytokine in psoriasis pathogenesis)

(3,8). These findings suggest that LSG

suppresses inflammatory cytokine expression under psoriatic

conditions. Mechanistically, the present findings indicated that

LSG administration interferes with key signaling pathways involved

in psoriasis. RT-qPCR revealed that LSG significantly decreased

mRNA expression of JAK2, STAT2 and STAT3, along with downregulation

of downstream targets BCL2 and CCND1 in psoriatic skin. The

decreased dermal expression of BCL2 suggests inhibition of the

JAK2/STAT3 pathway (27). The

downregulation of JAK2, STAT2 and STAT3 mRNA following LSG

administration may be a consequence of upstream cytokine

suppression, particularly IL-23 and IL-17A, which drive JAK/STAT

activation. While direct inhibition of JAK/STAT signaling by LSG

cannot be excluded, evidence suggests an indirect mechanism

mediated by decreased proinflammatory cytokine levels (47). Future mechanistic studies, including

kinase activity assays, are warranted to determine whether LSG

directly interacts with JAK/STAT components. This pathway serves a

critical role in IL-23-mediated STAT3 activation, which promotes

Th17 cell differentiation and subsequent IL-17A production,

contributing to psoriatic inflammation and keratinocyte dysfunction

(4). Although NF-κB activity was

not directly assessed in the present study, its role as a master

regulator of psoriatic inflammation is well established (4,48).

Notably, SPs from other marine sources inhibit NF-κB activation

(49), suggesting that LSG may

exert similar effects.

Psoriasis, as an inflammatory disease, leads to

immune system activation and is commonly associated with

organomegaly, manifested by increased lymph node and spleen weight,

which serves as an indicator of disease severity (33). LSG in IMQ-induced psoriatic mice

significantly decreased lymph node and spleen size and weight

compared with untreated psoriatic mice, suggesting LSG alleviated

disease progression driven by immune activation (50). Additionally, no signs of hepatic or

renal toxicity were observed in LSG-treated mice during the 7-day

treatment period, as assessed by histopathological analysis. Serum

biochemical markers for renal and hepatic function (alanine

aminotransferase, aspartate transaminase; AST, creatinine) were not

measured due to limited serum availability, as the samples were

primarily used for inflammatory cytokine analysis. Therefore,

potential subclinical organ toxicity cannot be fully excluded,

although histological analysis did not reveal any renal or hepatic

damage. However, in a previous study, intraperitoneal

administration of SP from Caulerpa cupressoides var.

lycopodium at a concentration of 9 mg/kg for 14 days

produced no signs of systemic toxicity in mice (51). Thus, short-term LSG is unlikely to

induce systemic toxicity, but longer-term studies and comprehensive

toxicological evaluations are required to confirm the absence of

cumulative or delayed adverse effects. This contrasts with

conventional treatments such as MTX and cyclosporine, which are

associated with cumulative toxicity and systemic side effects

(9).

LSG promotes wound healing by promoting fibroblast

proliferation, collagen synthesis and re-epithelialization

(52). These regenerative effects,

combined with its anti-inflammatory properties, suggest LSG may be

effective in managing inflammatory skin conditions such as

psoriasis. Additionally, LSG derived from G. fisheri

exhibits strong free radical scavenging activity and enhances

antioxidant capacity via activation of the nuclear factor erythroid

2-related factor 2/antioxidant response element signaling pathway,

indicating broader therapeutic potential beyond dermatological

applications (15). Previous

studies on G. fisheri derived SG have primarily focused on

wound-healing models (18,52). An octanoyl-esterified SG accelerates

wound closure in rats, improves collagen deposition, increases

α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) and vimentin expression and decreases

expression of TNF-α at the wound site. Likewise, our recent study

reported that a SG derivative improves histopathology and modulates

wound healing proteins such as Ki67, α-SMA, E-cadherin and vimentin

in a rat excision wound model (52). These findings highlight the

regenerative and anti-fibrotic potential of G.

fisheri-derived polysaccharides in tissue repair. To the best

of our knowledge, the present study is the first to demonstrate

that LSG from G. fisheri attenuates IMQ-induced psoriasis,

an immune-mediated dermatosis characterized by keratinocyte

hyperproliferation and Th17-driven inflammation. This extends the

therapeutic scope of G. fisheri derived SG beyond wound

repair to the modulation of immune-driven skin inflammation.

Bioactivity of Gracilaria-derived polysaccharides is

influenced by molecular weight and degree of sulfation, with lower

molecular weight fractions exhibiting anti-inflammatory effects

(53); consistent with this, the

LSG preparation used in the present study displayed potent

immunomodulatory effects in vivo. In comparison with

standard therapies such as cyclosporine and acitretin, MTX exerts

anti-proliferative and immunosuppressive effects primarily via the

inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase (54), whereas LSG acts via

immunomodulation, downregulation of inflammatory cytokines and

suppression of JAK/STAT signaling. Unlike MTX, which can cause

cumulative hepatotoxicity and bone marrow suppression with

long-term use, LSG demonstrated no detectable hepatic or renal

toxicity over the 7-day treatment period. From a pharmacological

perspective, LSG represents a class of marine-derived

polysaccharides with potent bioactivity and a favorable safety

profile, making it a promising candidate for further drug

development (12). Collectively,

these findings suggest that LSG from G. fisheri exerts

strong anti-psoriatic effects by inhibiting key inflammatory

pathways and decreasing keratinocyte hyperproliferation and

abnormal differentiation. However, the optimal delivery route,

long-term efficacy and large-scale production feasibility remain to

be further investigated.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the

efficacy of LSG derived from G. fisheri in alleviating

IMQ-induced psoriasis by decreasing psoriatic skin lesions and

attenuating inflammatory responses. These effects were evidenced by

decreased production of proinflammatory cytokines and infiltration

of inflammatory cells in both skin lesions and systemic tissue. In

addition, LSG treatment downregulated mRNA expression of key

components of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Although the precise

molecular mechanisms underlying its therapeutic effects remain to

be elucidated, the immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory

properties suggest that LSG has potential as a marine-derived

therapeutic agent for psoriasis management. Further studies are

warranted to clarify the specific signaling pathways involved and

validate its clinical applicability in human models.

Supplementary Material

Schematic diagram showing the

experimental timeline. PC, Petroleum cream; NS, Normal saline; NC,

Normal control; MTX, Methotrexate; LSG, Low molecular weight

sulfated galactan; IP, Intraperitoneal; IMQ, Imiquimod.

GPC, FTIR and NMR profiles of LSG from

Gracilaria fisheri. GPC, gel permeation chromatography;

FTIR, Fourier-transform infrared; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance;

LSG, Low molecular weight sulfated galactan.

Effect of LSG on psoriasis-like skin

in IMQ-induced psoriatic mice. Representative dorsal skin on days

1, 3, 5, and 7. LSG treatment visibly decreased the severity of

skin lesions from day 5 to 7. LSG, Low molecular weight sulfated

galactan; IMQ, Imiquimod; NC, Normal control; MTX,

Methotrexate.

Effect of LSG on IMQ-induced psoriasis

severity and body weight in mice. Daily evaluation of (A) erythema,

(B) scaling and (C) skin thickening using a modified human PASI

scoring system. (D) Cumulative PASI score. (E) Body weight. LSG,

Low molecular weight sulfated galactan; IMQ, Imiquimod; NC, Normal

control; PASI, Psoriasis area and severity index; MTX,

Methotrexate.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Laboratory

Animal Research Center, University of Phayao, for providing the

animal facility, and the School of Medical Sciences, University of

Phayao, Phayao, Thailand for access to the laboratory facility. The

authors would also to thank Dr Dylan Southard for language editing

of the manuscript via the Khon Kaen University Publication Clinic

(Khon Kaen, Thailand).

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the University of

Phayao and the Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fund

(Fundamental Fund 2024; grant no. 256/2567) and the Faculty of

Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Thailand (grant no. IN67066).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

KJ, AP and TR conceived and designed the study. KJ,

AP, LP, SJ, TC, PP and TR performed the experiments. KJ, AP, KW and

TR analyzed data. KJ, AP and TR wrote the manuscript. KJ, AP, KW,

and TR edited the manuscript. KW and TR supervised the study. KJ,

AP and TR confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethical

Committee of the University of Phayao, Phayao, Thailand in

accordance with the Ethics of Animal Experimentation guidelines

established by the National Research Council (approval no.

1-024-65).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Moon CI, Lee J, Baek YS and Lee O:

Psoriasis severity classification based on adaptive multi-scale

features for multi-severity disease. Sci Rep.

13(17331)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Rendon A and Schäkel K: Psoriasis

pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 20(1475)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE

and Barker JNWN: Psoriasis. Lancet. 397:1301–1315. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Bugaut H and Aractingi S: Major role of

the IL17/23 axis in psoriasis supports the development of new

targeted therapies. Front Immunol. 12(621956)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Xue Y, Zhang L, Chu L, Song Z, Zhang B, Su

X, Liu W and Li X: JAK2/STAT3 pathway inhibition by AG490

ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis via

regulation of Th17 cells and autophagy. Neuroscience. 552:65–75.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Dutta S, Chawla S and Kumar S: Psoriasis:

A review of existing therapies and recent advances in treatment. J

Rational Pharmacother Res. 4:12–23. 2018.

|

|

7

|

Qiao P, Zhi D, Yu C, Zhang C, Wu K, Fang

H, Shao S, Yin W, Dang E, Li K and Wang G: Activation of the C3a

anaphylatoxin receptor inhibits keratinocyte proliferation by

regulating keratin 6, keratin 16, and keratin 17 in psoriasis.

FASEB J. 36(e22322)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lowes MA, Bowcock AM and Krueger JG:

Pathogenesis and therapy of psoriasis. Nature. 445:866–873.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Balak DMW, Gerdes S, Parodi A and

Salgado-Boquete L: Long-term safety of oral systemic therapies for

psoriasis: A comprehensive review of the literature. Dermatol Ther

(Heidelb). 10:589–613. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Woo YR, Cho DH and Park HJ: Molecular

mechanisms and management of a cutaneous inflammatory disorder:

Psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 18(2684)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kumar A, Soratur A, Kumar S and Maran BAV:

A review of marine algae as a sustainable source of antiviral and

anticancer compounds. Macromol. 5(11)2025.

|

|

12

|

B J and R R: A critical review on

pharmacological properties of sulfated polysaccharides from marine

macroalgae. Carbohydr Polym. 344(122488)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Siringoringo B, Huipao N, Tipbunjong C,

Nopparat J, Wichienchot S, Hutapea AM and Khuituan P: Gracilaria

fisheri oligosaccharides ameliorate inflammation and colonic

epithelial barrier dysfunction in mice with acetic acid-induced

colitis. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 11:440–449. 2021.

|

|

14

|

Kang J, Jia X, Wang N, Xiao M, Song S, Wu

S, Li Z, Wang S, Cui SW and Guo Q: Insights into the

structure-bioactivity relationships of marine sulfated

polysaccharides: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 123(107049)2021.

|

|

15

|

Rudtanatip T, Pariwatthanakun C, Somintara

S, Sakaew W and Wongprasert K: Structural characterization,

antioxidant activity, and protective effect against hydrogen

peroxide-induced oxidative stress of chemically degraded

Gracilaria fisheri sulfated galactans. Int J Biol Macromol.

206:51–63. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Chen YF, Zheng JJ, Qu C, Xiao Y, Li FF,

Jin QX, Li HH, Meng FP, Jin GH and Jin D: Inonotus obliquus

polysaccharide ameliorates dextran sulphate sodium induced colitis

involving modulation of Th1/Th2 and Th17/Treg balance. Artif Cells

Nanomed Biotechnol. 47:757–766. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Pai SK, Chakraborty K, Pai AA and Dhara S:

Therapeutic promise of a sulfated (1→4) galactan from edible sea

grape Caulerpa racemosa: Modulation of cytokine expression in

lipopolysaccharide-induced CALU-1 cells. Int J Biol Macromol.

313(144117)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Rudtanatip T, Somintara S, Sakaew W,

El-Abid J, Cano ME, Jongsomchai K, Wongprasert K and Kovensky J:

Sulfated galactans from Gracilaria fisheri with

supplementation of octanoyl promote wound healing activity in vitro

and in vivo. Macromol Biosci. 22(2200172)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wongprasert K, Rudtanatip T and Praiboon

J: Immunostimulatory activity of sulfated galactans isolated from

the red seaweed Gracilaria fisheri and development of

resistance against white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) in shrimp. Fish

Shellfish Immunol. 36:52–60. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Karamani C, Antoniadou IT, Dimou A,

Andreou E, Kostakis G, Sideri A, Vitsos A, Gkavanozi A, Sfiniadakis

I, Skaltsa H, et al: Optimization of psoriasis mouse models. J

Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 108(107054)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Neu SD, Strzepa A, Martin D, Sorci-Thomas

MG, Pritchard KA Jr and Dittel BN: Myeloperoxidase inhibition

ameliorates plaque psoriasis in mice. Antioxidants (Basel).

10(1338)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wang A, Ma X, Wei F, Li Y, Liu Q and Zhang

H: Evidence on the therapeutic role of thiolutin in

imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice. Immun

Inflamm Dis. 11(e877)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Fahlquist-Hagert C, Sareila O, Rosendahl S

and Holmdahl R: Variants of beta-glucan polysaccharides

downregulate autoimmune inflammation. Commun Biol.

5(449)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

dos Santos Ferreira J, da Silva Prudêncio

R, de Sousa AK, Sousa SG, de Sousa de Lima FM, dos Santos Carvalho

A, da Costa ACC, Silva DMM, da Graça Sales Furtado M, Rocha DML, et

al: Sulfated polysaccharide extracted from the alga Gracilaria

domingensis modified with propionic anhydride negatively

modulates acute inflammation and experimental hypernociception.

Bioact Carbohydr Diet Fibre. 32(100459)2024.

|

|

25

|

van der Fits L, Mourits S, Voerman JSA,

Kant M, Boon L, Laman JD, Cornelissen F, Mus AM, Florencia E, Prens

EP and Lubberts E: Imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin

inflammation in mice is mediated via the IL-23/IL-17 axis. J

Immunol. 182:5836–5845. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Lindford A, Juteau S, Jaks V, Klaas M,

Lagus H, Vuola J and Kankuri E: Case report: Unravelling the

mysterious Lichtenberg figure skin response in a patient with a

high-voltage electrical injury. Front Med (Lausanne).

8(663807)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Pudgerd A, Jongsomchai K, Muangkaew W,

Phuapittayalert L, Jamsuwan S, Chanmanee T, Vanichviriyakit R and

Sukphopetch P: A tryptophol-containing emulgel ameliorates

imiquimod-induced mice psoriasis. Sci Rep. 15(19398)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Aratwar A, Maji I, Chilvery S, Mahajan S,

Aalhate M, Gupta U, Godugu C and Singh PK: Contemplating novel W/O

emulsion-based gel for anti-psoriatic activity of Tofacitinib in

imiquimod-induced Balb/C mice model. AAPS PharmSciTech.

26(12)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Sezer E, Böer-Auer A, Cetin E, Tokat F,

Durmaz E, Sahin S and Ince U: Diagnostic utility of Ki-67 and

Cyclin D1 immunostaining in differentiation of psoriasis vs other

psoriasiform dermatitis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 5:7–13.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zhang P, Su Y, Li S, Chen H, Wu R and Wu

H: The roles of T cells in psoriasis. Front Immunol.

14(1081256)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Li L, Lu J, Liu J, Wu J, Zhang X, Meng Y,

Wu X, Tai Z, Zhu Q and Chen Z: Immune cells in the epithelial

immune microenvironment of psoriasis: Emerging therapeutic targets.

Front Immunol. 14(1340677)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Hatem S and El-Kayal M: Novel

anti-psoriatic nanostructured lipid carriers for the cutaneous

delivery of luteolin: A comprehensive in-vitro and in-vivo

evaluation. Eur J Pharm Sci. 191(106612)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Khongthong S, Theapparat Y, Roekngam N,

Tantisuwanno C, Otto M and Piewngam P: Characterization and

immunomodulatory activity of sulfated galactan from the red seaweed

Gracilaria fisheri. Int J Biol Macromol. 189:705–714.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Lambert LJ, Muzumdar MD, Rideout WM III

and Jacks T: Chapter 15-Basic mouse methods for clinician

researchers: Harnessing the mouse for biomedical research. In:

Basic Science Methods for Clinical Researchers. Academic Press,

pp291-312, 2017.

|

|

36

|

Lan J, Li Y, Wen J, Chen Y, Yang J, Zhao

L, Xia Y, Du H, Tao J, Li Y and Zhu J: Acitretin-conjugated dextran

nanoparticles ameliorate psoriasis-like skin disease at low

dosages. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 9(816757)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Manggau M, Kasim S, Fitri N, Aulia S,

Agustiani AN, Raihan M and Nurdin WB: Antioxidant,

anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant activities of sulfate

polysaccharide isolate from brown alga Sargassum polycystum. IOP

Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 967(012029)2022.

|

|

38

|

Tripathi D, Srivastava M, Rathour K, Rai

AK, Wal P, Sahoo J, Tiwari KR and Pandey P: A promising approach of

dermal targeting of antipsoriatic drugs via engineered nanocarriers

drug delivery systems for tackling psoriasis. Drug Metab Bioanal

Lett. 16:89–104. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Dawoud ADH and Abdalbagi M: Evaluation of

anti-psoriatic activity of Aloe sinkatana extract on imiquimod

induced psoriatic-like dermatitis in mice. Pharm Biomed Res.

11:41–48. 2025.

|

|

40

|

Cho Y, Kwon J and Kim TS: Imiquimod

promotes Th1 and Th17 responses via NF-κB-driven IL-12 and IL-6

production in an in vitro co-culture model. Exp Ther Med.

30(175)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Minokawa Y, Sawada Y and Nakamura M:

Lifestyle factors involved in the pathogenesis of alopecia areata.

Int J Mol Sci. 23(1038)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Zhou XY, Chen K and Zhang JA: Mast cells

as important regulators in the development of psoriasis. Front

Immunol. 13(1022986)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Assawawongkasem N, Techangamsuwan S,

Piyaviriyakul P, Puchadapirom P and Sailasuta A: Involucrin,

cytokeratin 10 and Ki67 expression in a threedimensional cultured

canine keratinocyte cell line in comparison to canine skin and

cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and a pilot study on

custom-designed siRNA-INV transfection. Thai J Vet Med. 50:43–55.

2020.

|

|

44

|

Ramezani M, Shamshiri A, Zavattaro E,

Khazaei S, Rezaei M, Mahmoodi R and Sadeghi M: Immunohistochemical

expression of P53, Ki-67, and CD34 in psoriasis and psoriasiform

dermatitis. Biomedicine (Taipei). 9(26)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Shi HJ, Zhou H, Ma AL, Wang L, Gao Q,

Zhang N, Song HB, Bo KP and Ma W: Oxymatrine therapy inhibited

epidermal cell proliferation and apoptosis in severe plaque

psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 181:1028–1037. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Armstrong AW and Read C: Pathophysiology,

clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: A review. JAMA.

323:1945–1960. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Fu S, Bao X, Mao Z, Lv Y, Zhu B, Chen Y,

Zhou M, Tain S, Zhou F and Ding Z: Tetrastigma hemsleyanum

polysaccharide ameliorates cytokine storm syndrome via the

IFN-γ-JAK2/STAT pathway. Int J Biol Macromol.

275(133427)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Blauvelt A and Chiricozzi A: The

immunologic role of IL-17 in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis

pathogenesis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 55:379–390. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Jayawardhana HHACK, Lee HG, Liyanage NM,

Nagahawatta DP, Ryu B and Jeon YJ: Structural characterization and

anti-inflammatory potential of sulfated polysaccharides from

Scytosiphon lomentaria; attenuate inflammatory signaling pathways.

J Funct Foods. 102(105446)2023.

|

|

50

|

Takuathung MN, Wongnoppavich A, Panthong

A, Khonsung P, Chiranthanut N, Soonthornchareonnon N and

Sireeratawong S: Antipsoriatic effects of Wannachawee recipe on

imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis in BALB/c mice. Evid

Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018(7931031)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Rodrigues JAG, Vanderlei ESO, de Araújo

IWF, Quinderé ALG, Coura CO and Benevides NMB: In vivo

toxicological evaluation of crude sulfated polysaccharide from the

green seaweed Caulerpa cupressoides var. lycopodium

in Swiss mice. Acta Sci Technol. 35:603–610. 2013.

|

|

52

|

Jongsomchai K, Pudgerd A, Sakaew W,

Wongprasert K, Kovensky J and Rudtanatip T: Sulfated galactan

derivative from Gracilaria fisheri improves histopathology

and alters wound healing-related proteins in the skin of excision

rats. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 29(388)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Khandwal D, Patel S, Pandey AK and Mishra

A: A comprehensive, analytical narrative review of polysaccharides

from the red seaweed Gracilaria: Pharmaceutical applications

and mechanistic insights for human health. Nutrients.

17(744)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Johnston A, Gudjonsson JE, Sigmundsdottir

H, Ludviksson BR and Valdimarsson H: The anti-inflammatory action

of methotrexate is not mediated by lymphocyte apoptosis, but by the

suppression of activation and adhesion molecules. Clin Immunol.

114:154–163. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Chen Y, Song S, Wang Y, Zhang X, Zhang J,

Wu L, Wu J and Li X: Topical application of berberine ameliorates

imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis in BALB/c mice via

suppressing JAK1/STAT1 signaling pathway. Arab J Chem.

17(105612)2024.

|

|

56

|

Maglakelidze N, Gao T, Feehan RP and Hobbs

RP: AIRE deficiency leads to the development of alopecia

areata-like lesions in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 143:578–587.e3.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Plaza R, Vidal S, Rodriguez-Sanchez JL and

Juarez C: Implication of STAT1 and STAT3 transcription factors in

the response to superantigens. Cytokine. 25:1–10. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|