Introduction

Liver cirrhosis is a global health challenge,

responsible for ~1.47 million deaths (2.4% of all deaths) in 2019,

with the greatest burden occurring in Southeast Asia and the

Western Pacific regions (1).

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, affecting an estimated

296 million people worldwide, remains the leading cause of

cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, accounting for ~331,000

cirrhosis-related deaths in 2019 and contributing to more than half

of hepatocellular carcinoma cases in endemic areas (2). The most recent WHO estimates further

indicate that HBV caused ~1.1 million deaths in 2022, mainly

attributable to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (3). Pathologically, HBV-associated

cirrhosis is characterized by progressive fibrosis, distortion of

hepatic architecture and sustained infiltration of diverse immune

cell populations, including neutrophils, hepatic macrophages, T and

B lymphocytes and natural killer cells, accompanied by a

pro-inflammatory cytokine milieu rich in IL-1, IL-6, IL-17, IL-22,

IL-35, TGF-β and TNF-α (4,5). Persistent hepatic inflammation

promotes stellate cell activation and extracellular matrix

deposition, perpetuating fibrogenesis and facilitating the

transition to decompensated disease (6).

Gut-derived microbiota and their metabolites,

together with nutrients and other signals, reach the liver via the

portal vein, a process referred to as the gut-liver axis (7,8).

Inflammatory cytokines and immune responses mediated by

infiltrating cells are key contributors to the initiation and

progression of liver fibrosis (9).

In recent years, growing attention (10-12)

has been directed toward the gut microbiota as a key regulator of

liver physiology, particularly via the gut-liver axis. These

complex microbial communities regulate both physiological and

immunological functions of the host, influencing not only local

intestinal processes but also systemic responses. Numerous

microbiome-wide association studies have demonstrated a link

between gut microbial dysbiosis and chronic diseases, including

metabolic syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease and liver

pathologies (13,14). Microbiota-derived metabolites and

pathogen-associated molecular patterns directly influence hepatic

immune responses and metabolic processes. In liver diseases such as

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), alcoholic liver disease

and cirrhosis, consistent shifts in microbial composition have been

documented (15,16). Notably, in cirrhosis, enrichment of

taxa such as Fusobacterium, Veillonella and members

of the Enterobacteriaceae family is associated with

heightened systemic inflammation and greater disease severity, with

several studies also indicating that these changes are more

pronounced in decompensated patients (17,18).

Mechanistic studies have begun to clarify how

microbial alterations influence liver health (7,19). The

gut microbiota produces a broad repertoire of bioactive

metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs),

lipopolysaccharides (LPS), bile acids, choline derivatives, indole

compounds, vitamins, lipids and niacin, which that regulate hepatic

immune signaling and metabolic balance (19,20).

Among these, SCFAs such as butyrate, acetate and propionate are

particularly notable for their ability to strengthen epithelial

tight junctions, enhance mucosal barrier integrity, suppress

intestinal inflammation and limit overgrowth of pathogenic

bacteria, in part via activation of free FA receptors 2 and

3(20). In experimental NAFLD

models, enrichment of SCFA-producing taxa is associated with

reduced hepatic lipid accumulation and attenuation of inflammatory

responses (21,22). Other microbial products such as bile

acids, tryptophan metabolites and LPS further modulate macrophage

polarization, antimicrobial peptide production and fibrotic

remodeling through receptors such as farnesoid X Receptor),

TGR5(Takeda G-protein coupled receptor 5) and AhR(Aryl Hydrocarbon

receptor), thereby linking gut dysbiosis to the pathophysiology of

both cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (8,23,24).

In parallel with these metabolic and

immunomodulatory functions, the gut microbiota is key for

preserving intestinal homeostasis. It achieves this by maintaining

the integrity of the mucus layer, sustaining the expression and

spatial organization of tight junction proteins and coordinating

mucosal immune responses. In cirrhosis, this equilibrium is

disrupted, characterized by diminished tight junction protein

expression, increased intestinal permeability and translocation of

bacterial products, which collectively exacerbate hepatic

inflammation, accelerate fibrogenesis and foster conditions that

facilitate pathogenic biofilm formation, aberrant immune activation

and chronic inflammation (25-27).

Histopathological analyses of cirrhotic livers typically

demonstrate dense infiltration by neutrophils, macrophages, T and B

lymphocytes and dendritic cells, indicative of a sustained

pro-inflammatory microenvironment (28,29).

Within this immune landscape, CD4+ T helper (Th) cell

subsets, including Th1, Th2 and Th17, and regulatory T cells serve

a central role in orchestrating immune responses: They regulate

CD8+ T cell expansion, promote B cell activation and

modulate multiple immune effectors throughout disease progression

(30,31). Although evidence links gut microbial

dysbiosis to immune activation in cirrhosis, most studies are

observational, and the precise mechanistic interplay between

microbiota alterations, systemic inflammation and barrier

dysfunction, particularly in HBV-associated cirrhosis, remains to

be elucidated (32-34).

The present study aimed to systematically

characterize the composition, diversity and predicted functions of

the gut microbiota in patients with HBV-associated liver cirrhosis.

By integrating microbial profiling with histological assessment of

immune infiltration and intestinal barrier integrity, the present

study aimed to elucidate the mechanistic underpinnings of the

gut-liver axis in cirrhosis progression and provide a basis for

microbiome-based diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Materials and methods

Study population and sample

collection

A total of 31 individuals with HBV-associated liver

cirrhosis (21 male, 10 female; median age, 48 years; age range,

28-65 years) were enrolled between April 2023 and April 2024,

before receiving any therapeutic intervention. Inclusion criteria

were as follows: age between 18 and 70 years; a confirmed diagnosis

of liver cirrhosis based on histology or imaging as described

above; chronic HBV infection; no prior receipt of antiviral therapy

for HBV. Exclusion criteria included: hepatocellular carcinoma;

human immunodeficiency virus infection; pregnancy or severe

cardiac; pulmonary; renal diseases. Cirrhosis was diagnosed by

liver biopsy or by concordant findings from at least two imaging

modalities (ultrasound, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance

imaging). Disease severity was assessed using the Child-Pugh

classification (35), which

evaluates serum total bilirubin and albumin, prothrombin time,

ascites and hepatic encephalopathy, categorizing patients as class

A (5-6 points), B (7-9 points) or C (≥10 points). The control group

included 15 healthy volunteers (8 male, 7 female; median age, 46

years; age range, 30-58 years) with no history of physical or

psychological disorder, confirmed through annual comprehensive

health evaluations including blood, urine and fecal analyses, liver

function and biochemical tests, hepatitis virus markers, chest

radiography and abdominal ultrasound. All participants were

recruited from the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen

University (Guangzhou, China).

Fecal sample collection was performed using a

TinyGene fecal collection box according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Boxes were placed on ice and stored at -80˚C before

further analysis.

A total of six normal liver tissue sections were

from para-hemangioma sites of patients with hepatic hemangioma

without hepatitis (three male, three female; median age, 45 years;

age range, 32-60 years). Paired samples of liver cirrhosis were

obtained from six separate patients with HBV-infected liver

cirrhosis during operations (four male, 2 female; median age, 48

years; age range, 30-65 years) before any therapeutic intervention.

Colonic mucosal specimens of 10 patients with untreated liver

cirrhosis (6 male, 4 female; median age, 47 years; age range, 27-63

years) and 10 healthy volunteers (5 male, 5 female; median age, 45

years; age range, 27-57 years) were obtained from the Endoscopic

Center of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University.

All tissues were verified by histopathology. The acquisition of

these tissues was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics

Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen

University (approval no. RG2023-033-01).

16S rRNA sequencing

The 16S rRNA gene was amplified using primers

as follows: Forward, 5'-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3' and reverse,

5'-CCGTCAATTCMTTTGAGTTT-3' targeting the V5-V6 hyper-variable

regions (M were degenerate bases, representing A or C) and

sequenced using the Illumina, Inc. platform following the

manufacturer's protocols. The library was constructed by using the

two-step PCR amplification method with the following thermocycling

conditions: Initial preamplification stage at 94˚C for 2 min and

then 22 cycles at 94˚C for 30 sec, 55˚C for 30 sec, and 72˚C for 30

sec. The second step preamplification stage at 94˚C for 2 min and

then 8 cycles at 94˚C for 30 sec, 55˚C for 30 sec, and 72˚C for 30

sec. QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (51604, QIAGEN) and

Phusion™ High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (M0530L, New

England Biolabs were used. The quality and integrity of the

extracted DNA were verified using agarose gel electrophoresis and a

Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies). Sequencing libraries were

quantified using a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and

the final loading concentration was adjusted to 4 nM. Paired-end

sequencing (2x300 bp) was performed on an Illumina MiSeq platform

using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600-cycl, MS-102-300, Illumin). Raw

reads were processed using Trimmomatic v0.39 (usadellab.org/cms/?page=trimmomatic),

FLASH v1.2.11 (ccb.jhu.edu/software/FLASH/), and Mothur v1.39.5

(mothur.org/). After demultiplexing, dereplication, and

filtering, operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were clustered at 97%

similarity using UCLUST v1.2.22q (drive5.com/usearch/) against the SILVA v128

(arb-silva.de/) and Greengenes v13_8 databases

(greengenes.secondgenome.com).

α-diversity (Chao1, ACE, Shannon, Simpson) was calculated using

Mothur v1.39.5 and QIIME v1.9.1 (qiime.org/),

while β-diversity (Jaccard, unweighted UniFrac, weighted UniFrac)

was assessed and visualized by PCoA with FastTree v2.1.3

(microbesonline.org/fasttree/).

Differentially abundant taxa were identified using MetaStats

(metastats.cbcb.umd.edu/), and LEfSe

(huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/lefse/) was used to detect

taxa differing significantly between groups. β-diversity clustering

was evaluated by analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) and correlations

between distance matrices were examined with the Mantel test.

Functional metagenome prediction

The USEARCH v9.2.64 global alignment command

(drive5.com/usearch/) was used to capture

OTU representative sequences from the Greengenes database v13_8

(greengenes.secondgenome.com).

Functional metagenome reconstruction was then performed using

PICRUSt v1.1.4 (picrust.github.io/picrust/). The predicted metagenome

functions were annotated against the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes

and Genomes (KEGG) orthology (kegg.jp/).

Histological staining

Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E), Sirius red,

immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence staining were performed

as previously described (36-38).

The cell index was determined by dividing the number of

histological staining signal-positive cells by the total number of

cells in ≥20 randomly selected fields of view (magnification,

x200). The antibodies were as follows: Anti-myeloperoxidase (MPO;

cat. no. A1374, Abclonal), -CD4 (cat. no. sc-19641), -CD19 (cat.

no. sc-19650; both Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), -CD68 (cat. no.

ab31630), -α-smooth muscle actin (cat. no. ab5694; both Abcam),

-claudin-1 (cat. no. 13255S), -zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1; cat. no.

8193T) and -E-cadherin (cat. no. 14472S; all Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.).

ELISA

DAO and endotoxin levels from peripheral superficial

vein blood were examined with ELISA kits (cat. nos. JL-T0829 and

JL52002D, respectively; both J&L Biological) to estimate

intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation according to

the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using R software (version 3.4.1)

and GraphPad Prism 6 (Dotmatics) software, including richness

estimators, the Ace, Chao and Shannon index, a diversity estimator

and rank dissimilarity and abundance distribution. Microbiome

compositional dissimilarity was represented by PCoA plots, and

quantified by unweighted or weighted UniFrac distance values. The

significant separation of the microbiome composition was determined

by ANOSIM and the significance differences in α and β diversity and

taxonomy between groups were analyzed using Wilcox test. Continuous

data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of ≥3 independent experimental

repeats and analyzed by Student's two-tailed paired t-test or one-

or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction as described

previously (39). P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Gut microbiota profile differs between

healthy volunteers and patients with liver cirrhosis

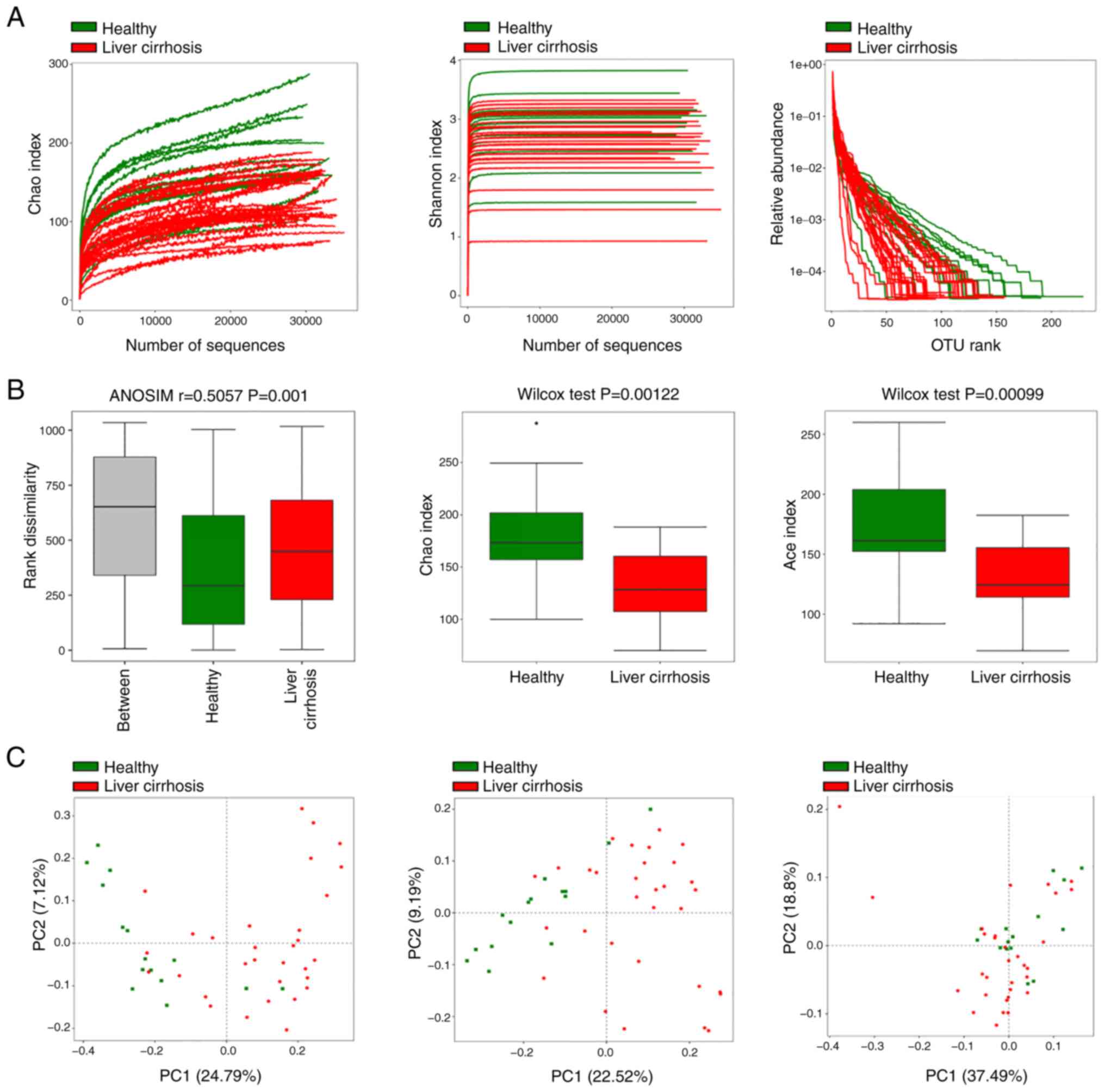

The present study compared the gut microbiota of

healthy volunteers with that of patients with liver cirrhosis using

Illumina MiSeq high-throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA

gene. In total, ~1,466,285 sequence reads of 16S rRNA genes,

with an average length of ~410 bp, and 432 OTUs were obtained after

sequencing and quality filtering (Fig.

1A). On average, healthy volunteers had more OTUs than patients

with liver cirrhosis (371 vs. 362 OTUs, respectively; 301 core OTUs

were shared). The average number of reads was not significantly

different between healthy and cirrhosis group (31,643 vs. 31,988

reads, respectively).

To evaluate the alterations in the microbiota

structure between healthy volunteers and patients with liver

cirrhosis, α diversity was measured. Patients with liver cirrhosis

had notably decreased microbial species richness and evenness in

comparison with volunteers, based on the Chao and Shannon index and

OTU rank abundance analysis (Fig.

1A). Furthermore, rank dissimilarity revealed that the

between-group difference was greater than the within-group

difference (Fig. 1B), and the Chao

and Shannon indices analyzed using the Wilcoxon test showed that

patients with liver cirrhosis had significantly lower gut microbial

diversity than healthy volunteers (Fig.

1B). β diversity based on OTUs or phylogenetic analysis was

calculated using Jaccard and unweighted and weighted UniFrac

phylogenetic distance matrices; microbial composition of patients

with liver cirrhosis was different from that of healthy volunteers

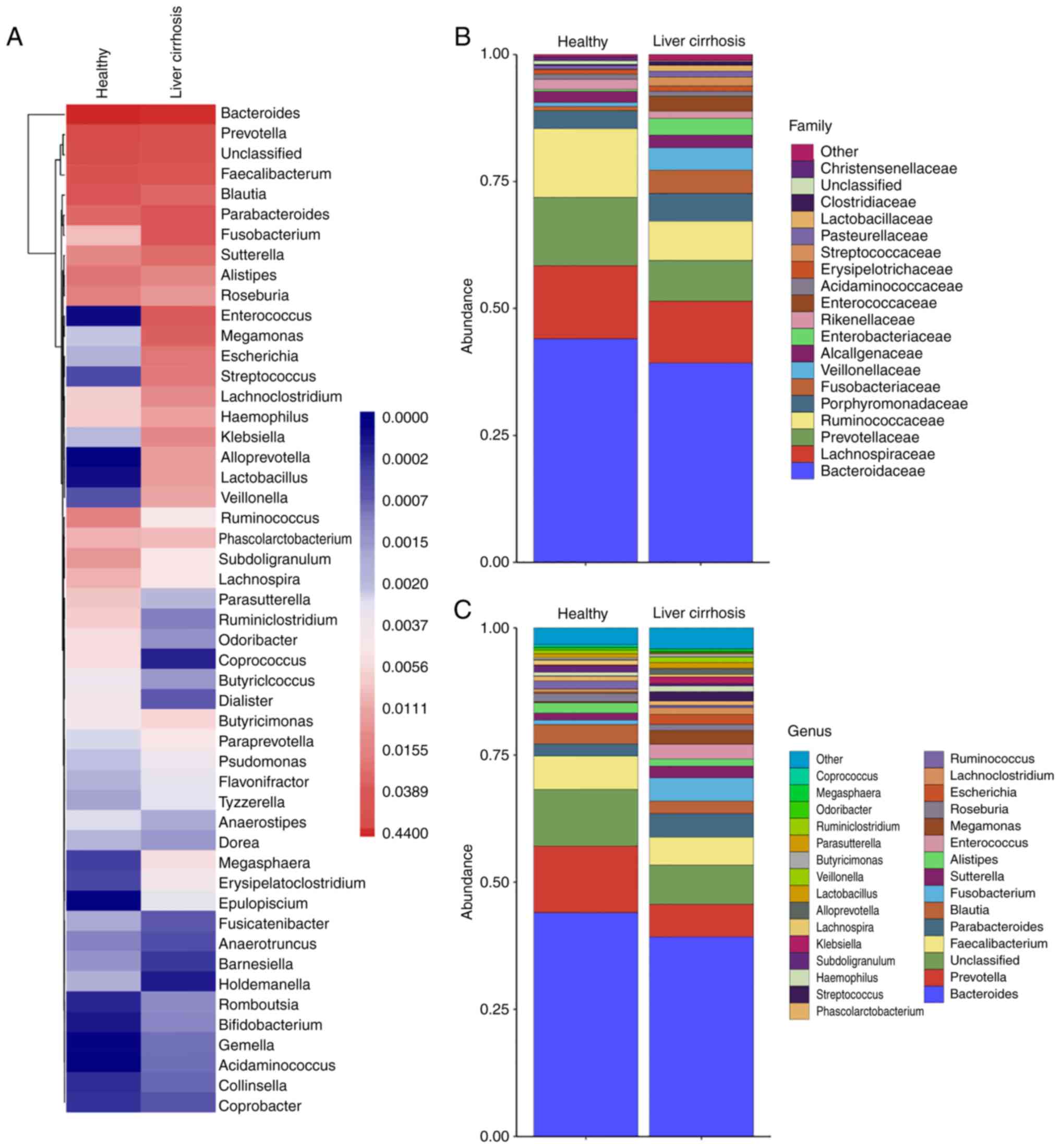

(Fig. 1C). Core bacterial genus

analysis using a heatmap demonstrated that the two groups had

similar microbiota structures or communities, but different

richness and abundance (Fig. 2A).

The relative bacterial community richness and abundance at the

family and genus levels were similar between groups (Fig. 2B and C).

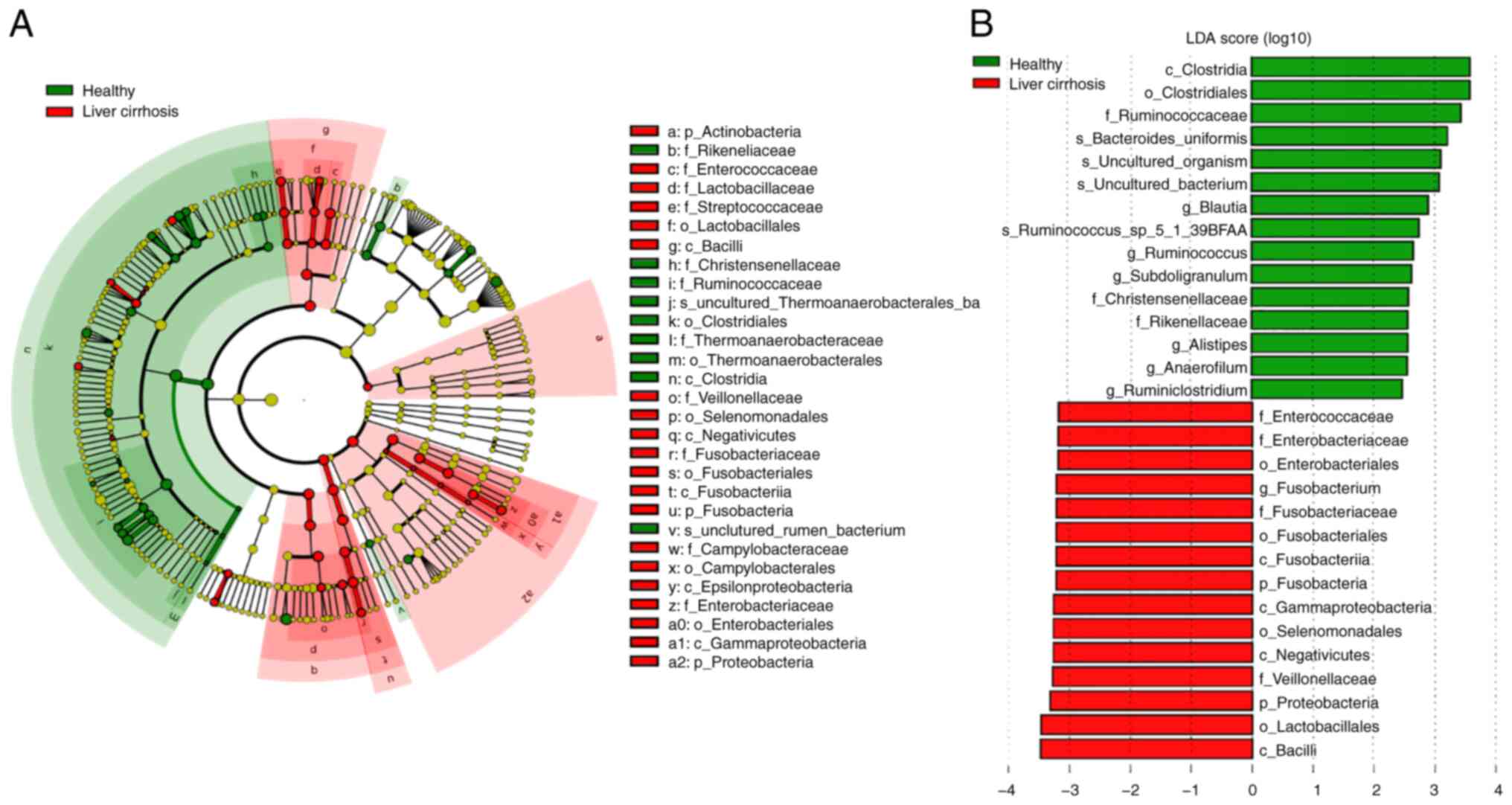

LEfSe was conducted to determine the most relevant

microbial taxa responsible for the differences between the groups

(Fig. 3A). This analysis identified

29 taxa that were differentially abundant between the two groups.

The microbiota of patients with liver cirrhosis was enriched in

Fusobacterium (genus), Veillonellaceae (family),

Lactobacillales (family), Negativicutes (class),

Gammaproteobacteria (class), and Enterobacteriaceae

(family), whereas healthy the microbiota of healthy volunteers was

enriched in Clostridiales (order), Ruminococcaceae

(family), Bacteroides (species), Subdoligranulum

(genus) and Subdoligranulum (genus; Fig. 3A and B). Moreover, the differentially abundant

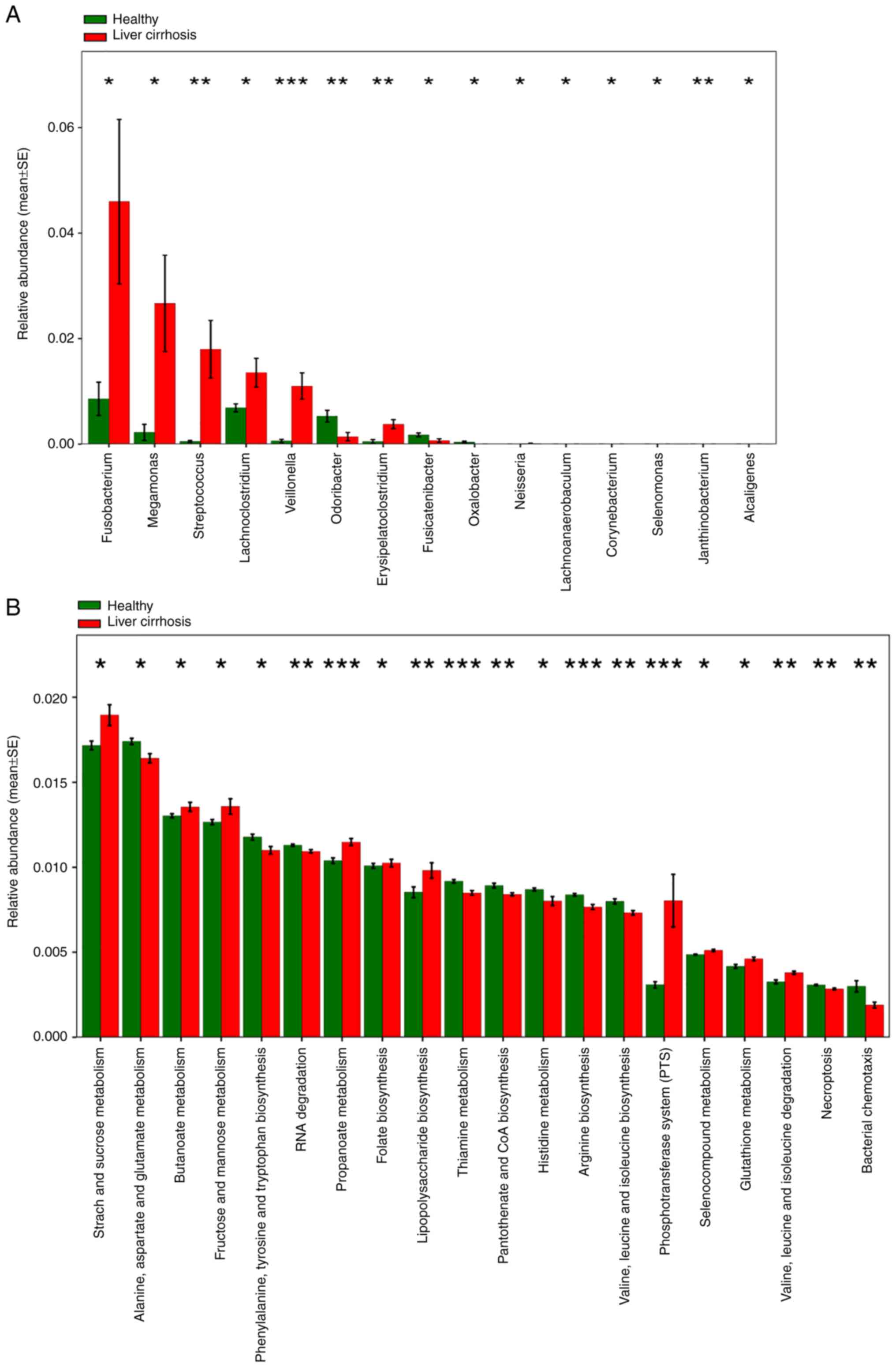

features of the microbial taxa at the genus level verified that the

abundance of Fusobacterium, Megamonas,

Streptococcus, Lachnoclostridium, Veillonella

and other bacteria was increased in the fecal samples of patients

with liver cirrhosis (Fig. 4A).

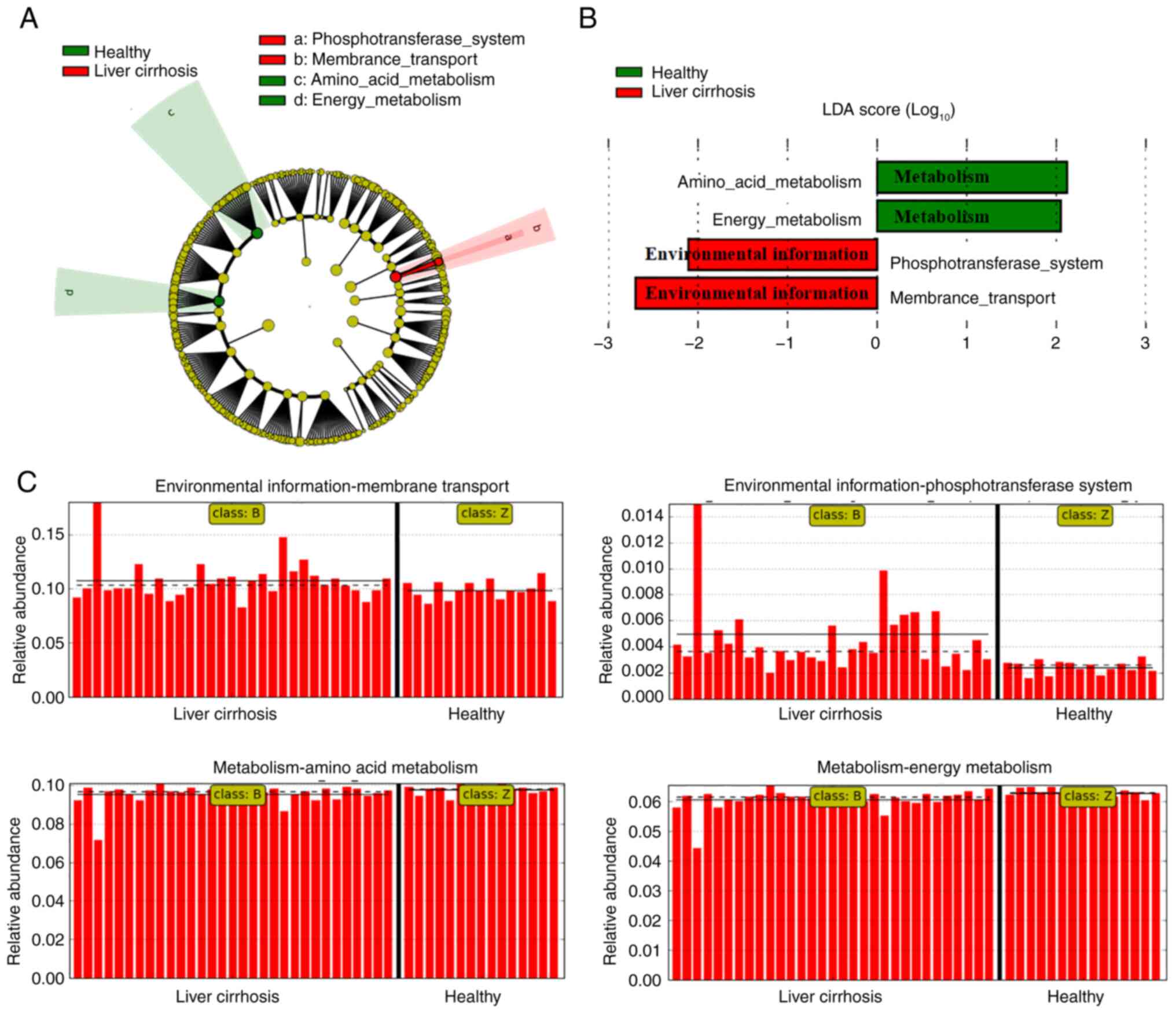

Based on the differences in community richness and

abundance, metagenome functional content based on the 16S

rRNA gene sequences was predicted using PICRUSt. Predicted KEGG

orthology pathways significantly enriched in liver cirrhosis

included ‘starch and sucrose metabolism’, ‘butanoate metabolism’,

‘fructose and mannose metabolism’, ‘propanoate metabolism’ and

‘phosphotransferase system (PTS)’, indicating that these metabolic

pathways participated in the progression of liver cirrhosis

(Fig. 4B). Moreover, to verify the

most relevant functional pathways based on the microbial

differences between healthy volunteers and patients with liver

cirrhosis, LEfSe analysis was performed. Functional composition of

the total gut microbiota in patients with liver cirrhosis was

primarily associated with ‘phosphotransferase system (PTS)’ and

‘membrane transport’ involved in environmental information

processing, in contrast to ‘amino acid metabolism’ and ‘energy

metabolism’ functions enriched in healthy volunteers (Fig. 5A-C). Collectively, these data

demonstrated the gut microbiota profile differs between healthy

volunteers and patients with liver cirrhosis, and that a specific

microbial community, diversity, and associated metagenome function

are present in those with liver cirrhosis.

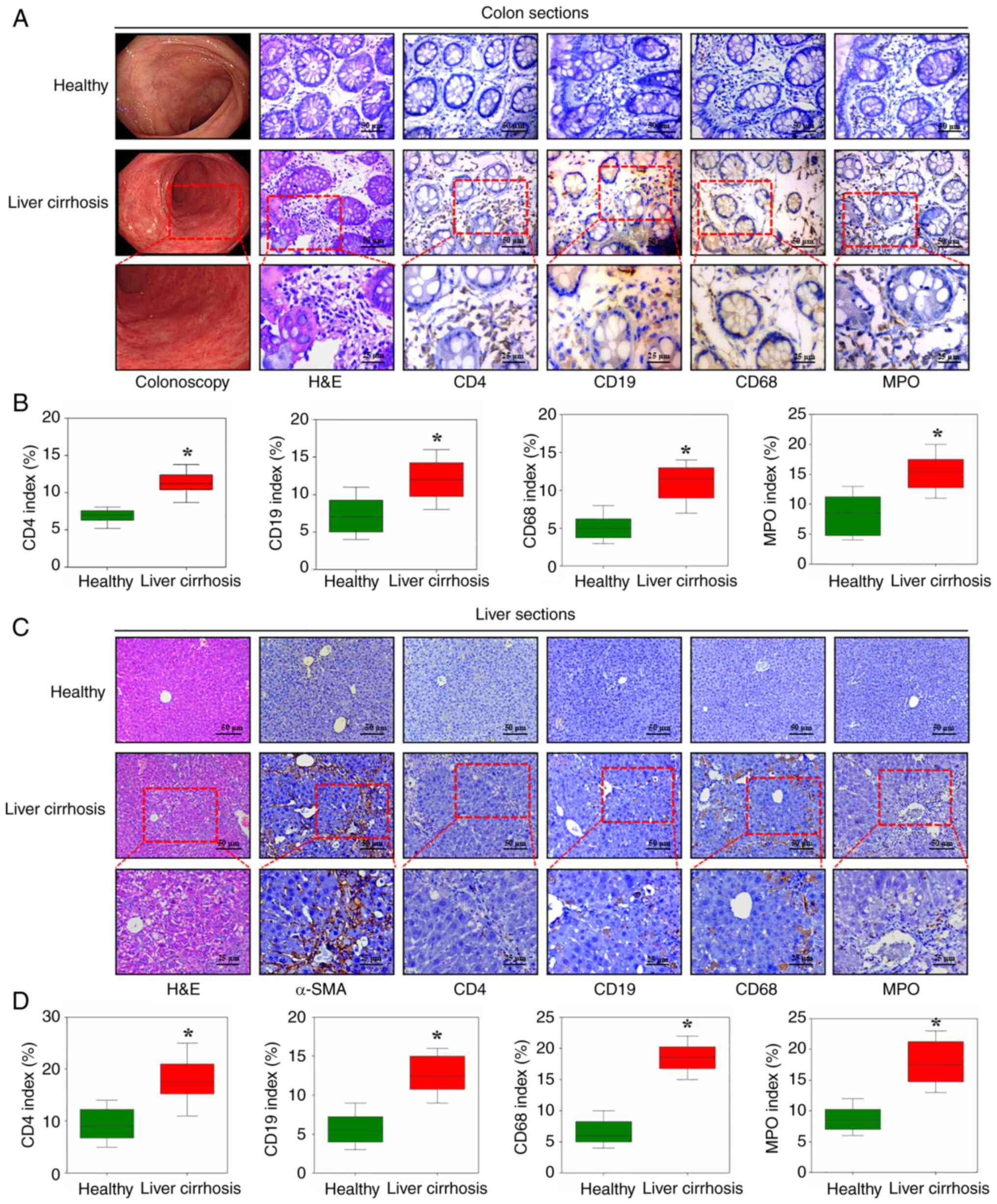

Gut microbiota of cirrhotic patients

influences the host immune response and the gut barrier

The bacterial species with increased abundance in

liver cirrhosis contribute to environmental information and

metabolic pathway components, which may instigate inflammation of

the host (17). Moreover, the gut

microbiota participates in the preservation of tolerance and

immunity of mucosal surfaces by regulating organic inflammatory

responses (40). Based on these

findings, the colonic mucosal specimens from patients with liver

cirrhosis and healthy volunteers were analyzed, which demonstrated

increased infiltration of inflammatory cells, including T

lymphocytes (CD4), B lymphocytes (CD19), macrophages (CD68) and

neutrophils (MPO), in the colonic tissues of patients with liver

cirrhosis. However, there was no notable histological architectural

alterations between the two groups based on H&E staining

(Fig. 6A and B). As expected, upregulated T and B

lymphocyte, macrophage and neutrophil infiltration, as well as

excess collagen deposition, was found in the liver tissues of

cirrhotic patients compared with those of healthy volunteers

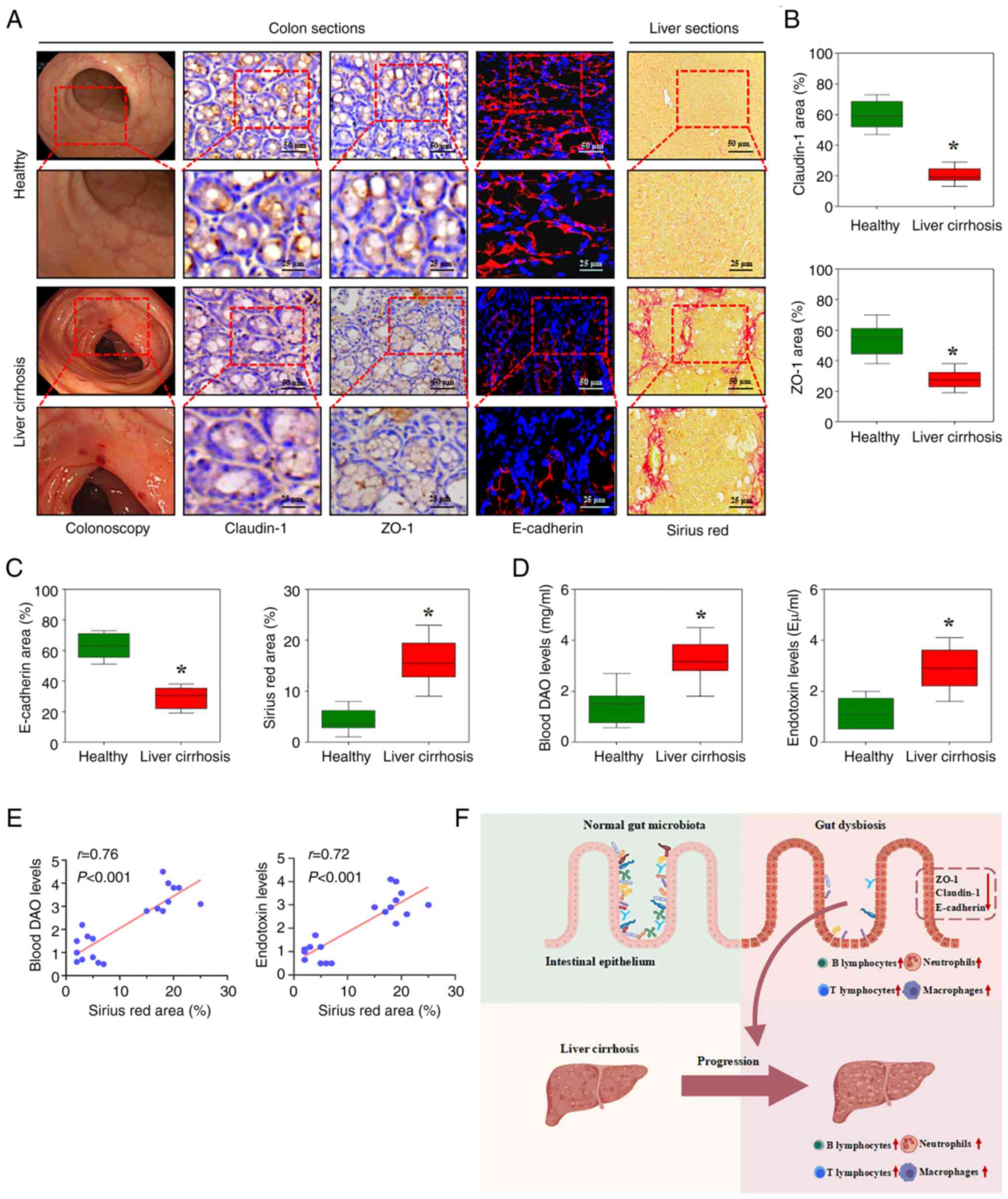

(Fig. 6C and D). On this basis, the present study

investigated how gut microbial changes relate to barrier

dysfunction and inflammatory responses in cirrhosis.

The functional composition of the total gut

microbiota in patients with liver cirrhosis primarily involved

‘phosphotransferase system (PTS)’ and ‘membrane transport’. Changes

in the gut microbiota modulate systemic microbe-derived metabolite

levels by altering intestinal permeability and the gut barrier,

especially tight junctions between epithelial cells (16). Claudin-1, ZO-1 and E-cadherin were

downregulated in colonic samples from patients with cirrhosis whose

liver tissues showed excess collagen deposition by Sirius red

staining (Fig. 7A-C). Intestinal

permeability, based on blood DAO determination, was significantly

increased, and blood endotoxin detection showed enhanced bacterial

translocation analysis in cirrhotic liver sections (Fig. 7D). In addition, the blood DAO and

endotoxin levels showed a positive correlation with collagen

deposition, as indicated by Sirius red staining of the liver tissue

(Fig. 7E). The results demonstrated

that the gut microbiota influences colonic and hepatic immune

responses, intestinal permeability and the gut barrier, which would

contribute to the progression of liver cirrhosis (Fig. 7F).

Discussion

The gut microbiome serves a key role in immune

development and function in the host, and in determining the host

metabolic state. An increasing number of studies have suggested

that the gut-derived microbiota and their components, metabolites,

nutrients and other signals can be delivered to the liver via the

portal vein circulation to serve as a bioreactor for autonomous

metabolic and immunological regulation and regulate responses

within the host environment (8,23,24).

Here, patients with HBV-associated cirrhosis exhibit distinct gut

microbial profiles compared with healthy individuals, characterized

by decreased diversity, enrichment of pro-inflammatory taxa,

functional shifts toward environmental information processing

pathways, compromised intestinal barrier function and marked

hepatic immune cell infiltration.

By comparing the gut microbiota between healthy

volunteers and patients with liver cirrhosis using high-throughput

sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene, the present study

demonstrated that patients with liver cirrhosis had decreased

microbial species richness, evenness, and diversity, although they

had similar microbial structures and communities according to core

bacterial genus analysis. This is supported by several studies

(41,42) indicating a disordered gut microbial

community and decreased diversity and species richness associated

with cirrhosis. Decreased microbial diversity is now recognized as

a feature of disease states, including inflammatory disorder,

colorectal cancer, and gastric carcinoma (43-46).

Furthermore, LEfSe analysis showed that the gut microbiota of

patients with liver cirrhosis was enriched in Fusobacterium,

Veillonellaceae, Lactobacillales,

Negativicutes, Gammaproteobacteria,

Enterobacteriaceae, whereas the proportion of phylum

Bacteroides, Clostridiales, Ruminococcaceae,

and Subdoligranulum was decreased compared with that of the

healthy volunteers. These results align with a previous study that

observed a marked loss of Bacteroides and significant

increases in Veillonella, Enterobacteriaceae and

Fusobacterium abundance in cirrhosis (47). This suggest that dysbiosis, or an

unfavorable change in the composition of the microbiome in liver

cirrhosis, is central to the pathophysiology of the onset,

progression and development of complications of liver cirrhosis.

Nonetheless, inconsistencies remain; for example, Chen et al

(47) reported decreased

Bacteroidetes and increased Proteobacteria and

Fusobacteria, whereas Sarangi et al (48) observed no significant differences in

microbial abundance. The differences in findings emphasize the need

for more research to clarify the specific roles of microbial taxa

in cirrhosis progression and treatment.

To explore functional consequences, KEGG orthology

analysis was performed on metagenomic sequencing data and found

that the total microbiota of patients with liver cirrhosis was

predominantly enriched in ‘phosphotransferase system (PTS)’ and

‘membrane transport’, pathways involved in environmental

information processing, whereas the microbiota of healthy controls

showed enrichment in ‘amino acid metabolism’ and ‘energy

metabolism’. Consistent with the present data, a previous study

also reported enhanced transport- and metabolism-associated

pathways, along with a marked loss of cell cycle-associated gene

functions, in cirrhotic patients (7,47).

Notably, the depletion of SCFA-producing taxa, such as

Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium hallii,

Ruminococcus and Agathobacter, has also been observed

in cirrhotic patients (49). These

butyrate-producing bacteria are key suppliers of energy for

colonocytes and contribute to maintaining mucosal integrity. Their

loss may compromise epithelial energy metabolism, attenuate

butyrate-mediated anti-inflammatory signaling and disrupt the

regulation of immune homeostasis. This depletion may aggravate the

decrease in tight junction proteins and the increased intestinal

permeability, thereby weakening barrier function and facilitating

microbial translocation to the liver (22,40).

These findings highlight the association between the gut microbiota

and host metabolism in liver cirrhosis, with the microbial balance

shifted toward a dysbiosis during the process of liver

cirrhosis.

The activation of inflammatory cells to produce

inflammatory cytokines and components is a key contributor to the

initiation and development of liver cirrhosis (28,29).

Increased T and B lymphocyte, macrophage and neutrophil

infiltration was detected in patients with liver cirrhosis compared

with healthy volunteers, and this was accompanied by excess

collagen deposition in liver tissue. These data indicated that

various inflammatory cells and responses are affected by

gut-derived microbiota, and their components, metabolites or

signals participate in the initiation and development of liver

fibrosis.

The dysbiotic microbial community associated with

liver cirrhosis is essential for the development and regulation of

the immune and metabolism systems of the host (7,19,20).

Changes in the gut microbiota modulate systemic microbe-derived

metabolite levels or signals by altering intestinal permeability

and the gut barrier, thus contributing to disease development

(23).

A critical mechanistic link between the dysbiotic

microbial community and the immune and metabolic systems of the

host is the structural compromise of the intestinal epithelial

barrier, which relies on tight junction proteins such as claudin-1

and ZO-1 and the adherens junction protein E-cadherin. To identify

potential associations between tight junctions in colonic

epithelial cells and microbial dysbiosis, the present study

analyzed colonic sections and found that claudin-1, ZO-1 and

E-cadherin levels were suppressed in colonic samples from cirrhotic

patients; this was associated with enhanced intestinal permeability

and bacterial translocation, suggesting that the tight junctions

between colonic epithelial cells were damaged during liver

fibrogenesis. In radiation-induced enteritis, gut dysbiosis

disrupts the localization of claudin-1, occludin and ZO-1,

weakening epithelial cohesion (50). Therapeutic modulation of the

microbiota can mitigate such injury; for example, Yu-Ping-Feng-San

(a traditional Chinese medicine decoction) treatment restores ZO-1,

occludin and claudin-1 expression in LPS-induced barrier damage

while decreasing inflammatory responses (51). At the molecular level, claudin-1

expression is regulated via the Piezo1/ROCK1/2 pathway, whereby

Piezo1 activation by mechanical or inflammatory cues decreases

claudin-1 protein expression and thereby impairs junctional

integrity (52). Similarly, loss of

SLC26A3 results in downregulation of ZO-1, occludin and E-cadherin

alongside microbial imbalance, underscoring the reciprocal

association between junctional protein expression and microbiota

composition (53). In metabolic

liver diseases such as NAFLD and NASH, breakdown of tight junctions

allows endotoxin influx to the liver, promoting inflammatory and

fibrotic changes (54). These data

highlight that gut barrier impairment, mediated by altered

junctional proteins in the context of dysbiosis, is a key driver of

microbial translocation and hepatic injury in cirrhosis.

While the present findings provide insights into the

gut microbiota-immune-barrier axis in HBV-associated cirrhosis,

several limitations should be noted. First, the cross-sectional

design precludes causal inference between microbiota dysregulation

and inflammation or barrier dysfunction, and the contribution of

HBV infection cannot be excluded; interventional approaches such as

probiotics, fecal microbiota transplantation or other

microbiota-targeted strategies are needed to test whether restoring

microbial balance can ameliorate these changes. Second, the sample

size may have limited the detection of subtle associations, and

data on diet, medication and antiviral therapy, important

microbiome modulators, were incomplete; these should be collected

in future longitudinal and interventional studies. Finally,

functional predictions based on 16S rRNA sequencing lack the

resolution of shotgun metagenomics, metatranscriptomics or targeted

metabolomics, which should be integrated to define microbiota-host

interactions in HBV-related cirrhosis. To address these issues,

future studies should adopt longitudinal designs with larger and

well-characterized cohorts, integrate clinical and dietary

information with multi-omics approaches, and evaluate

interventional strategies such as probiotic or prebiotic

supplementation, dietary modulation and fecal microbiota

transplantation to determine whether restoring microbial balance

can mitigate inflammation, reinforce barrier function and slow

disease progression.

In conclusion, the gut microbiota profile in

patients with HBV-associated liver cirrhosis differs markedly from

that of healthy individuals, showing enrichment of taxa such as

Fusobacterium, Veillonella and members of the

Enterobacteriaceae family, alongside depletion of beneficial

butyrate-producing genera including Faecalibacterium,

Ruminococcus and Agathobacter. These compositional

shifts, together with decreased overall diversity and altered

functional potential, particularly enrichment in

‘phosphotransferase system (PTS)’ and ‘membrane transport’ and

depletion of ‘amino acid metabolism’ and ‘energy metabolism’, are

closely associated with impaired colonic and hepatic immune

responses, increased intestinal permeability and compromised gut

barrier integrity. Gut microbiota dysbiosis contributes to the

pathophysiology of HBV-associated cirrhosis. Understanding these

microbial alterations may provide a basis for microbiota-targeted

strategies to mitigate hepatic inflammation and preserve barrier

function in affected patients. Future longitudinal and

interventional studies are warranted to establish causality and

evaluate the therapeutic potential of microbiota-targeted

interventions in HBV-associated cirrhosis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Natural Science

Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant no. 2023A1515011204), the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82170569)

and the Science and Technology Planning Projects of Guangzhou City

(grant nos. 2024A04J6565 and 2025A03J3193).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the ScienceDB under accession number 31253.11.sciencedb.28999 or

at the following URL: doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.28999.

Authors' contributions

KX and YZ designed the methodology and analyzed

data. KX and YZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. ShT,

XO and JL designed the methodology. SiT conceived the study and

wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants

before the initiation of the study. The present study protocol was

approved by the Institute Research Ethics Committee of the Third

Affiliated Hospitals of Sun Yat-sen University (Guangzhou, China;

approval no. RG2023-033-01).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Huang DQ, Terrault NA, Tacke F, Gluud LL,

Arrese M, Bugianesi E and Loomba R: Global epidemiology of

cirrhosis-aetiology, trends and predictions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 20:388–398. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hsu YC, Huang DQ and Nguyen MH: Global

burden of hepatitis B virus: Current status, missed opportunities

and a call for action. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 20:524–537.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

World Health Organization. Hepatitis B.

Fact sheet. Geneva, 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b.

|

|

4

|

Suh YG, Kim JK, Byun JS, Yi HS, Lee YS,

Eun HS, Kim SY, Han KH, Lee KS, Duester G, et al: CD11b(+) Gr1(+)

bone marrow cells ameliorate liver fibrosis by producing

interleukin-10 in mice. Hepatology. 56:1902–1912. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Kornek M, Popov Y, Libermann TA, Afdhal NH

and Schuppan D: Human T cell microparticles circulate in blood of

hepatitis patients and induce fibrolytic activation of hepatic

stellate cells. Hepatology. 53:230–242. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Hammerich L and Tacke F: Hepatic

inflammatory responses in liver fibrosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 20:633–646. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Usami M, Miyoshi M and Yamashita H: Gut

microbiota and host metabolism in liver cirrhosis. World J

Gastroenterol. 21:11597–11608. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Levy M, Blacher E and Elinav E:

Microbiome, metabolites and host immunity. Curr Opin Microbiol.

35:8–15. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Luedde T and Schwabe RF: NF-kappaB in the

liver-linking injury, fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat

Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 8:108–118. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Pabst O, Hornef MW, Schaap FG, Cerovic V,

Clavel T and Bruns T: Gut-liver axis: Barriers and functional

circuits. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 20:447–461.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Hov JR and Karlsen TH: The microbiota and

the gut-liver axis in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Nat Rev

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 20:135–154. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Anand S and Mande SS: Host-microbiome

interactions: Gut-Liver axis and its connection with other organs.

NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 8(89)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Lynch SV and Pedersen O: The human

intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N Engl J Med.

375:2369–2379. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Lavelle A, Lennon G, Winter DC and

O'Connell PR: Colonic biogeography in health and ulcerative

colitis. Gut Microbes. 7:435–442. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Maslennikov R, Poluektova E, Zolnikova O,

Sedova A, Kurbatova A, Shulpekova Y, Dzhakhaya N, Kardasheva S,

Nadinskaia M, Bueverova E, et al: Gut microbiota and bacterial

translocation in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci.

24(16502)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Liu Y, Chen Z, Li C, Sun T, Luo X, Jiang

B, Liu M, Wang Q, Li T, Cao J, et al: Associations between changes

in the gut microbiota and liver cirrhosis: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 25(16)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kang EJ, Cha MG, Kwon GH, Han SH, Yoon SJ,

Lee SK, Ahn ME, Won SM, Ahn EH and Suk KT: Akkermansia muciniphila

improve cognitive dysfunction by regulating BDNF and serotonin

pathway in gut-liver-brain axis. Microbiome. 12(181)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Sharma SP, Gupta H, Kwon GH, Lee SY, Song

SH, Kim JS, Park JH, Kim MJ, Yang DH, Park H, et al: Gut microbiome

and metabolome signatures in liver cirrhosis-related complications.

Clin Mol Hepatol. 30:845–862. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Hackstein CP, Assmus LM, Welz M, Klein S,

Schwandt T, Schultze J, Förster I, Gondorf F, Beyer M, Kroy D, et

al: Gut microbial translocation corrupts myeloid cell function to

control bacterial infection during liver cirrhosis. Gut.

66:507–518. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Qin N, Yang F, Li A, Prifti E, Chen Y,

Shao L, Guo J, Le Chatelier E, Yao J, Wu L, et al: Alterations of

the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature. 513:59–64.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Shashni B, Tajika Y, Ikeda Y, Nishikawa Y

and Nagasaki Y: Self-assembling polymer-based short chain fatty

acid prodrugs ameliorate non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and liver

fibrosis. Biomaterials. 295(122047)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Mao T, Zhang C, Yang S, Bi Y, Li M and Yu

J: Semaglutide alters gut microbiota and improves NAFLD in db/db

mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 710(149882)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Spiljar M, Merkler D and Trajkovski M: The

immune system bridges the gut microbiota with systemic energy

homeostasis: Focus on TLRs, mucosal barrier, and SCFAs. Front

Immunol. 8(1353)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Acharya C and Bajaj JS: Gut microbiota and

complications of liver disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am.

46:155–169. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Jandl B, Dighe S, Baumgartner M,

Makristathis A, Gasche C and Muttenthaler M: Gastrointestinal

biofilms: Endoscopic detection, disease relevance, and therapeutic

strategies. Gastroenterology. 167:1098–1112.e5. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wang J, He M, Yang M and An X: Gut

microbiota as a key regulator of intestinal mucosal immunity. Life

Sci. 345(122612)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kuo CH, Wu LL, Chen HP, Yu J and Wu CY:

Direct effects of alcohol on gut-epithelial barrier: Unraveling the

disruption of physical and chemical barrier of the gut-epithelial

barrier that compromises the host-microbiota interface upon alcohol

exposure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 39:1247–1255. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Jung Y, Witek RP, Syn WK, Choi SS,

Omenetti A, Premont R, Guy CD and Diehl AM: Signals from dying

hepatocytes trigger growth of liver progenitors. Gut. 59:655–665.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Seki E and Schwabe RF: Hepatic

inflammation and fibrosis: Functional links and key pathways.

Hepatology. 61:1066–1079. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Du YN, Tang XF, Xu L, Chen WD, Gao PJ and

Han WQ: SGK1-FoxO1 signaling pathway mediates Th17/Treg imbalance

and target organ inflammation in angiotensin II-induced

hypertension. Front Physiol. 9(1581)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Muranski P and Restifo NP: Essentials of

Th17 cell commitment and plasticity. Blood. 121:2402–2414.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Liu R, Kang JD, Sartor RB, Sikaroodi M,

Fagan A, Gavis EA, Zhou H, Hylemon PB, Herzog JW, Li X, et al:

Neuroinflammation in murine cirrhosis is dependent on the gut

microbiome and is attenuated by fecal transplant. Hepatology.

71:611–626. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Zhao B, Jin Y, Shi M, Yu L, Li G, Cai W,

Lu Z and Wei C: Gut microbial dysbiosis is associated with

metabolism and immune factors in liver fibrosis mice. Int J Biol

Macromol. 258(129052)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Santiago A, Sanchez E, Clark A, Pozuelo M,

Calvo M, Yañez F, Sarrabayrouse G, Perea L, Vidal S, Gallardo A, et

al: Sequential changes in the mesenteric lymph node microbiome and

immune response during cirrhosis induction in rats. mSystems.

4:e00278–18. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Durand F and Valla D: Assessment of the

prognosis of cirrhosis: Child-Pugh versus MELD. J Hepatol. 42

(Suppl 1):S100–S107. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Tan S, Chen X, Xu M, Huang X, Liu H, Jiang

J, Lu Y, Peng X and Wu B: PGE2/EP4 receptor

attenuated mucosal injury via β-arrestin1/Src/EGFR-mediated

proliferation in portal hypertensive gastropathy. Br J Pharmacol.

174:848–866. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Tan S, Li L, Chen T, Chen X, Tao L, Lin X,

Tao J, Huang X, Jiang J, Liu H and Wu B: β-Arrestin-1 protects

against endoplasmic reticulum stress/p53-upregulated modulator of

apoptosis-mediated apoptosis via repressing p-p65/inducible nitric

oxide synthase in portal hypertensive gastropathy. Free Radic Biol

Med. 87:69–83. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Tan S, Lu Y, Xu M, Huang X, Liu H, Jiang J

and Wu B: β-Arrestin1 enhances liver fibrosis through

autophagy-mediated Snail signaling. FASEB J. 33:2000–2016.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Xiao Y, Liu X, Xie K, Luo J, Zhang Y,

Huang X, Luo J and Tan S: Mitochondrial dysfunction induced by

HIF-1α under hypoxia contributes to the development of gastric

mucosal lesions. Clin Transl Med. 14(e1653)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Wang R, Li B, Huang B, Li Y, Liu Q, Lyu Z,

Chen R, Qian Q, Liang X, Pu X, et al: Gut microbiota-derived

butyrate induces epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming in

myeloid-derived suppressor cells to alleviate primary biliary

cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 167:733–749.e3. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Solé C, Guilly S, Da Silva K, Llopis M,

Le-Chatelier E, Huelin P, Carol M, Moreira R, Fabrellas N, De Prada

G, et al: Alterations in gut microbiome in cirrhosis as assessed by

quantitative metagenomics: relationship with acute-on-chronic liver

failure and prognosis. Gastroenterology. 160:206–218.e13.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Shen Y, Wu SD, Chen Y, Li XY, Zhu Q,

Nakayama K, Zhang WQ, Weng CZ, Zhang J, Wang HK, et al: Alterations

in gut microbiome and metabolomics in chronic hepatitis B

infection-associated liver disease and their impact on peripheral

immune response. Gut Microbes. 15(2155018)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Hui W, Yu D, Cao Z and Zhao X: Butyrate

inhibit collagen-induced arthritis via Treg/IL-10/Th17 axis. Int

Immunopharmacol. 68:226–233. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Gevers D, Kugathasan S, Denson LA,

Vazquez-Baeza Y, Van Treuren W, Ren B, Schwager E, Knights D, Song

SJ, Yassour M, et al: The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset

Crohn's disease. Cell Host Microbe. 15:382–392. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Lepage P, Häsler R, Spehlmann ME, Rehman

A, Zvirbliene A, Begun A, Ott S, Kupcinskas L, Doré J, Raedler A

and Schreiber S: Twin study indicates loss of interaction between

microbiota and mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis.

Gastroenterology. 141:227–236. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Ahn J, Sinha R, Pei Z, Dominianni C, Wu J,

Shi J, Goedert JJ, Hayes RB and Yang L: Human gut microbiome and

risk for colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 105:1907–1911.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Chen Y, Yang F, Lu H, Wang B, Chen Y, Lei

D, Wang Y, Zhu B and Li L: Characterization of fecal microbial

communities in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology.

54:562–572. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Sarangi AN, Goel A, Singh A, Sasi A and

Aggarwal R: Faecal bacterial microbiota in patients with cirrhosis

and the effect of lactulose administration. BMC Gastroenterol.

17(125)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Qi P, Yang XX, Wang CK, Sang W, Zhang W

and Bai Y: Analysis of gut and circulating microbiota

characteristics in patients with liver cirrhosis and portal vein

thrombosis. Front Microbiol. 16(1597145)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Jian Y, Zhang D, Liu M, Wang Y and Xu ZX:

The impact of gut microbiota on radiation-induced enteritis. Front

Cell Infect Microbiol. 11(586392)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Wang Y, Wang Y, Ma J, Li Y, Cao L, Zhu T,

Hu H and Liu H: YuPingFengSan ameliorates LPS-induced acute lung

injury and gut barrier dysfunction in mice. J Ethnopharmacol.

312(116452)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Jiang Y, Song J, Xu Y, Liu C, Qian W, Bai

T and Hou X: Piezo1 regulates intestinal epithelial function by

affecting the tight junction protein claudin-1 via the ROCK

pathway. Life Sci. 275(119254)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Kumar A, Priyamvada S, Ge Y, Jayawardena

D, Singhal M, Anbazhagan AN, Chatterjee I, Dayal A, Patel M, Zadeh

K, et al: A novel role of SLC26A3 in the maintenance of intestinal

epithelial barrier integrity. Gastroenterology. 160:1240–1255.e3.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Jadhav K and Cohen TS: Can you trust your

gut? Implicating a disrupted intestinal microbiome in the

progression of NAFLD/NASH. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

11(592157)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|