Introduction

The population of US citizens aged 65 years and

older is projected to increase from 58 million in 2022 to 82

million by 2050(1). The increase in

aging-related comorbidities is closely linked to neurological

changes characterized by a reduction in the volume of the frontal

lobe and hippocampus (2,3), leading to progressive loss of myelin

integrity (4), calcium

dysregulation (5), mitochondrial

dysfunction and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (6). These changes likely contribute to

cognitive decline, sensorimotor impairments and increased

vulnerability to neurodegenerative disorders (7-9).

Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease are among the most

prevalent aging-related neurodegenerative diseases that lack

effective preventative treatments (10). Given the multifaceted nature of

these diseases, holistic approaches that target multiple pathways

hold promise in addressing aging-related cognitive decline.

Garlic has been used as a seasoning or condiment in

cooking and folk medicine for thousands of years across various

cultures (11). Sulfur-containing

compounds, such as allicin and S-allyl cysteine (SAC), are known to

contribute to its pungent aroma. Besides its use in cooking, garlic

has been shown to exhibit antioxidant properties, and thus, is

considered to offer various health benefits. Among various garlic

supplements, aged garlic extract (AGE) has been noted for being an

odorless and stable product resulting from prolonged extraction of

fresh garlic at room temperature, and has essential bioavailable

properties (12-14).

Previous research has further indicated that AGE and its active

components, such as SAC and N-α-(1-deoxy-D-fructos-1-yl)-L-arginine

(FruArg), could offer various systemic health benefits (15). More specifically, studies have

highlighted the role of AGE in mitigating aging-related diseases

and cardiovascular health risks by lowering cholesterol levels,

reducing calcification in coronary arteries, reducing acute phase

reactants, and exerting striking protection against systolic and

diastolic hypertension (16-20).

Animal studies have also revealed that AGE and its active

components, such as diallyl trisulfide and SAC, could offer

cardioprotective effects, including reducing myocardial damage and

supporting glyco- and lipo-metabolism (21,22).

Human trials have corroborated these findings, indicating that AGE

can improve arterial elasticity, reduce inflammation, and stabilize

the ventricular mass in patients with diabetes and cerebrovascular

disease (CVD) (23-26).

Several single-center randomized clinical trials have also revealed

that AGE could attenuate the progression of subclinical

atherosclerosis, regenerate peripheral tissue perfusion measured

post occlusive reactive hyperemia by laser speckle contrast imaging

and increase microcirculation in patients with arteriolosclerosis

(27,28). There is strong evidence indicating

the ability of AGE to slow the progression of atherosclerosis, thus

serving as a nutraceutical in the primary prevention and mitigation

of CVD and stroke. Previous studies have suggested that AGE and its

bioactive components could enhance resiliency against inflammation

whilst mitigating learning and memory deficits by modulating

neuronal glucose transport and oxidative stress (15,29,30).

These multifaceted health benefits underscore the potential of AGE

to serve as a valuable nutraceutical to enhance neuroprotection and

improve systemic resilience for brain health.

Previous studies on short-term AGE supplementation

have demonstrated improvements in spatial learning and memory in

young rats with amyloid-β pathology (9 weeks-old) (30,31).

Another study has further demonstrated the ability of the AGE

supplement to improve learning and memory deficits in mice with

accelerated brain atrophy (12 months old) (32). The proposed molecular mechanisms of

short-term AGE supplementation include antiglycation and

antioxidation (14), activation of

antioxidant enzymes (31), and

decreasing oxidative stress and inflammation by modulating the

activities of NF-κB and activator protein-1 whilst inhibiting

matrix metalloproteinases (33).

There is also evidence showing the ability of AGE to inhibit lipid

peroxidation, reduce ischemic/reperfusion damage and inhibit

oxidative modification of low-density lipoprotein (34). Molecular studies using murine BV-2

microglial cells have further demonstrated the ability of AGE to

reduce nitric oxide production, and alter the expression levels of

20 proteins enriched in the cytosol, mitochondria, plasma membrane

and cytoskeleton (15,35,36).

Based on the results of previous studies using

cultured cells and short-term animal models, it was deemed valuable

to investigate the chronic effects of AGE supplementation on

different behavioral paradigms, including the assessment of

cognitive decline, sensorimotor deficits, memory impairments and

anxiety-like behaviors. In the present study, 43-week-old mice were

fed a diet supplemented with AGE for 40 weeks, and the chronic

effect on their neurological behavior, as well as brain proteomes

and molecular pathways, was examined. The results of the present

study revealed the long-term benefits of AGE supplementation during

the natural aging process.

Materials and methods

Animal husbandry

A total of 48 male C57BL/6J mice (RRID:

IMSR_JAX:000664) aged 42 weeks (±3 days) were obtained from The

Jackson Laboratory. In the present study, 42-week-old mice were

selected because this age is equivalent to middle-age in humans

(37,38). On the day of arrival, the mice were

randomly placed in a cage, with two mice per cage. Placing two mice

per cage has been shown previously to provide an essential

environment for social interaction and tracking food consumption

(39,40). Mice were housed in an AAALAC

accredited animal facility under standard conditions: The ambient

temperature 68-79˚F, relative humidity 30-70%, 10-15 air changes

per h, and a 12/12-h light/dark cycle.

After 1 week of habituation, the 43-week-old mice

(body weight 33.9±0.6 g) were administered either the AGE

supplement or the control diet for 40 weeks (~10 months). Control

mice were fed the nutritionally complete diet AIN93G (cat. no.

F3156-Rodent Diet; AIN-93G Bio-Serv®), and the AGE mice

were fed the AIN diet supplemented with AGE (cat. no. F10217 Rodent

Diet; AIN-93G-Modified; AGE-CSA-Missouri; Bio-Serv®).

AGE (40%; w/w aqueous solution) was provided by Wakunaga

Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. The AGE diet was prepared using the AIN93G

base diet from Bio-Serv. AGE solution (2 kg) in 26 kg of the base

diet (25.2 kg base diet powder and 2 kg AGE solution) was used to

prepare 26 kg of the AGE diet. Because 2 kg of AGE solution

contains 0.8 kg dry weight and 1.2 kg of water, the diet was dried

at 120˚F in order to bring the moisture down to 5% after pelleting

for microbial stability. For the control diet, 8% water was added

to the dry mix as a pelleting aid. Mice were given the specific

diets along with ad libitum access to water. Food intake was

determined every week and body weights were measured every 2 weeks.

To avoid additional stress, body weight was measured after behavior

tests.

After feeding the mice the respective diets for 40

weeks, mice were subjected to behavior assessments. Prior to

behavior tests, mice were housed in a reverse 12/12-h light/dark

cycle environment for 2 weeks. All animal protocols were approved

by the University of Missouri Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC)

(approval no. 25120; Columbia, USA).

The present study strictly adhered to the guidelines

set forth by the University of Missouri and the National Institutes

of Health for conducting animal studies and followed an approved

method of euthanasia (The American Veterinary Medical

Association-approved method). Mice should be euthanized before they

experience significant pain or distress. The general appearance of

the mice was checked by monitoring signs such as dehydration,

severe weight loss, persistent abnormal posture or hypothermia,

behavioral changes (such as inability to reach food or water, or

lethargy) and clinical signs (such as labored breathing). The mice

were euthanized with ~5% isoflurane and it was confirmed that there

was no response to a firm toe pinch, and no signs of breathing and

heartbeats, and the mice were continued to be exposed to ~5%

isoflurane for ≥1 min to ensure euthanasia. Subsequently, the mice

were perfused with saline through a cannula inserted into the left

ventricle of the heart to wash out the blood. Removing blood from

the brain results in cleaner tissue samples, which can enhance the

accuracy and reliability of results. The mice were decapitated, and

brain tissues were collected for future studies.

Assessment of multi-domain behavior

functions

The aim of the battery of neurobehavioral tests was

to assess the impact of dietary AGE supplementation on multiple

behavioral domains associated with natural aging in mice (Fig. S1). All behavior tests were carried

out in the dark phase (resting phase; with red lights in the

testing room). Prior to the behavior tests, mice were placed in the

testing room for ≥1 h for acclimation, and tests were conducted

from 9:00 am to 3:30 pm. A battery of comprehensive behavior tests

was established to evaluate different phenotypes under functional

and cognitive behavioral domains, including sensorimotor function,

exploratory behavior, anxiety/neophobia, memory and learning. To

test sensorimotor functions, a simple neuro-assessment of

asymmetric impairment (SNAP) test and an inverted screen test were

performed. For anxiety/neophobia responses, the light-dark

transition test, emergence test, open-field test, elevated-plus

maze and zero maze were used. To assess memory and learning, the

novel object recognition (NOR), three-chamber sociability and

Barnes maze tests were performed.

SNAP

The SNAP test was used to measure common

neurological function domains including sensorimotor responses. The

eight test phenotypes consist of interaction, cage grasp, visual

placing, pacing/circling, gait/posture, head tilt, visual field and

baton, as described previously (41). The SNAP test provides a relatively

sensitive, reliable and time-efficient means of assessing

neurological deficits in mice. Each individual test has a scoring

range of 0-5 based on the established guidelines for atypical

neurologic behavior (42).

Inverted screen test

The inverted screen test was used to measure motor

function, coordination and muscle strength under the functional

behavior domain. It is a quick but insensitive gross screening test

that provides a measure of muscular strength. This test was

performed as previously described by Deacon with modifications

(43). Untrained mice were

individually placed on top of a square (7.5x7.5 cm) wire screen

which is mounted horizontally on a metal rod. Within 2 sec, the

wire screen was rotated to an inverted position (180˚), displacing

the mouse to the bottom of the screens. The mouse was kept in this

position for 1 min (checking with a stopwatch). This position

causes the mouse to fall. Normally, the mouse can hold the screen

within a period of time and climb up the incline. The following

parameters were measured: i) latency to fall off the screen, ii)

could not climb up the screen, and iii) able to climb up the screen

within 1-min testing session.

Light-dark transition test

The light-dark box is a behavioral test that

measures novelty-seeking and anxiety-like behaviors in mice under

the cognitive domain. The test, performed according to the authors'

previous studies (44,45), has the same area as the open-field

test, except that half of the area is closed, and a small opening

(7.5 cm high and 5 cm wide) could be found in the middle. Briefly,

animals were placed in the light side of the box and were allowed

to explore the box for 5 min. Their movements were tracked and

analyzed using the ANY-maze software (RRID: SCR_014289; V7.16,

Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL; Windows XP OS). A total of 3

measurements were calculated for each mouse: i) latency to first

entry into the dark area, ii) number of entries to the dark area,

and iii) time spent in the light area.

Open field test

As described previously, the open-field test was

performed to measure locomotion, exploratory activity and

anxiety-like behaviors (44,46,47).

The open-field activity box is 40x40 cm and located on a white

platform. Animals were placed into the center of the square arena

for 10 min. After each trial, the box was cleaned with 10% ethanol

solution and air-dried. The animals' movements were tracked and

analyzed using the ANY-maze software. A series of 10x10-cm blocks

were identified to track mouse activity, with 4 blocks defined as

the center zone and the surrounding 12 blocks as the peripheral

zone. Phenotypic parameters such as total distance traveled and

time spent in different zones (that is, center vs. periphery) were

recorded as indicators of anxiety.

NOR test

The NOR test in the open-field platform evaluates

non-spatial learning and recognition memory under the cognition

behavioral domain, as previously described (48), with a few modifications. First, the

animal was allowed to become familiarized with an object for 5 min.

After a 20~30 min interval, the object was placed in a different

location in the same arena. Mice were allowed to explore the

familiar object in the different location for 5 min. After 24 h, a

new (novel) object was placed in the platform together with the

familiar object. Normally, the color or shape of the novel object

was changed, and the mouse was allowed to explore the object for 5

min. The entire test was recorded and measured using the ANY-maze

software. In the aforementioned test, the following parameters were

measured: i) Discrimination Index (DI) and ii) percentage of total

investigating time. The DI was calculated by taking the difference

between time investigating the novel object and the time

investigating the familiar object, divided by the total time

investigating both objects. The percentage of total investigating

time was calculated by dividing the time investigating the novel

object by the total time investigating both objects.

Emergence test

The emergence test is widely used to assess

neophobia and exploratory behavior in rodents (49,50).

The apparatus is an adaptation of the open-field test and intended

to evaluate novelty-based anxiety. Naturally, rodents have an

innate explorative drive as well as an aversion to brightly lit

open spaces. The task involves observation of the time taken for

the subject to exit the holding container (shelter) and explore the

arena. Mice with high levels of anxiety tend to spend more time in

shelter than in the open spaces.

Briefly, a large open field arena surrounded by high

walls was used for this test. A cylindrical shaped tube

(13.2x4.4x4.4 cm) that serves as the holding container or shelter,

was used to restrain the mouse before placing in the arena. The

shelter was equipped with lids and secured in place to prevent it

from rolling in the center of the arena. While carrying the mouse

in the tube, it was ensured not to close the lid tightly to

maintain proper ventilation. After placing the tube in the center,

the lid was removed. The number and time the subject spent in the

shelter (tube), number of pokes into the shelter (tube) door, and

time spent in the lit arena, were recorded and measured using the

ANY-maze software.

Elevated plus maze test

The elevated plus maze test was used to evaluate the

anxiety and fear domains. The test is based on the concept that

rodent's natural behavior is to stay in the enclosed areas and

display unconditional fear in open spaces and elevated heights.

Anxious animals tend to spend more time in the closed arms than

less anxious animals. The elevated plus maze was built according to

the description of Lister (51).

This maze was made of Plexiglas and consisted of a central square

(5x5 cm) from which radiated four arms (5x45 cm). Two of the arms

had walls (15 cm high) along the edge (closed arms), whereas the

other two arms did not have walls (open arms). A white line was

drawn halfway (22.5 cm) along each of the four arms to measure

motor activity. The maze was elevated 45 cm above the floor on a

plus-shaped plywood stand. The mouse was placed at the junction of

the four arms of the maze, facing a closed arm. They were allowed

to explore the apparatus for 5 min while an observer, a video

camera, and the automated tracking system recorded their actions.

Time spent in the open/closed arms and the duration of time in the

center were tracked by ANY-maze software and used those for scoring

various cognitive behavior parameters including: i) Number of

entries in the open or closed arms, ii) time spent in the open or

closed arms, iii) time spent in the center, and iv) percentage of

time spent in the open/closed arms.

Zero maze

The zero maze was used to test anxiety- and

exploratory-related behaviors in mice. It is an elevated,

ring-shaped runway, with the same amount of area devoted to the

adjacent open and closed quadrants. Mice were placed in one of the

closed quadrants at the start of each trial and were allowed to

explore the apparatus for 5 min. The ANY-maze software was used for

scoring cognitive behavior parameters including: i) Number of

entries in the open or closed segments, ii) time spent in the open

or closed segments, iii) time spent in the center, and iv)

percentage of time spent in the open/closed segments.

Three-chamber sociability test

A three-chamber social interaction test was

performed to assess sociability and social preference as described

previously (52). Mice were

habituated in the middle compartment for five min before testing.

The ‘strange’ animal (same age and strain) was placed in the wire

cage of either the left or right compartment. The strange mouse's

location represented stranger zone 1 while the other wire cage

remained empty (that is, empty zone). Mice were left to socialize

for 10 min. The time spent in the stranger zone 1 (interaction with

the new mouse) relative to the time spent in the empty zone was

measured.

The social preference test was conducted for another

10 min after termination of the sociability test. A second strange

mouse was introduced to the wire cage in place of the empty zone

and was considered stranger zone 2. The animal's preference for

interacting with a familiar animal (stranger zone 1) or an

unfamiliar animal (stranger zone 2) was determined by measuring the

same parameters. The indices of sociability and social preference

were computed, as previously described (53).

Barnes maze

Spatial learning and memory were tested using the

Barnes maze as described (44,54).

The maze consists of a circular platform (75 cm diameter) with 20

holes (5 cm diameter) evenly spaced around the platform's perimeter

and is elevated 56.5 cm above the floor by a stand. One hole was

designated as the escape hole for each mouse, and an escape box was

placed underneath the hole. For each mouse, the location of the

escape box remained the same throughout all test runs. To create an

aversive environment, three 72-watt lights were suspended above the

platform, encouraging the mice to flee from the highly lit

environment into the darkened environment of the box. Four shapes

(+, ∎, ∆, •) served as visual cues and each shape respectively was

placed on each side of the black background curtains to aid spatial

navigation. Behavioral testing consisted of 2 habituation trials on

the first day, and 8 evaluation trials (2 trials/day) over the next

4 days. Reversal training consisted of 2 trials per day for 3 days,

with an inter-trial interval of 20-30 min. This phase began 24 h

after the final acquisition trial. Prior to the start of reversal

training, each mouse was assigned a new escape hole, positioned

opposite the previously assigned location. Latency (that is, the

time mice found the escape box) and total errors (that is,

nose-pokes into non-escape holes) were recorded and analyzed by

ANY-maze software.

Data and statistical analysis for

behavior tests

The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Results

were analyzed by one-way or two-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism

Software (RRID:SCR_002798; V10.0; Dotmatics). Tukey's post hoc test

was applied for multiple comparisons. Differences were considered

statistically significant at P<0.05 for all analyses. An

unpaired t-test was applied for individual comparisons between two

groups.

Tissue collection for analysis of

global proteomes from brain cortex and hippocampus

A total of 10 mice, AGE (n=5) and control diet

(n=5), were euthanized at 88 weeks-old (following 11 months of AGE

supplementation) for label-free global proteomic quantitation by

tandem mass spectrometry (MS2) analysis. The sample

preparation for quantitative proteomic analysis has been described

previously (55). Briefly, the left

cortex and hippocampi from both hemispheres were dissected and

processed. Tissues were lysed with sample buffer containing 2%

sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 0.5 M tetraethylammonium bicarbonate

(TEAB), pH 8.5, protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100), and

phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (1:100). Specimens were homogenized

by Glas-Col stringer 099C K43 (Glas-Col LLC, IN) and centrifuged at

17,000 x g for 20 min at 4˚C. The protein pellets (insoluble

fraction) were collected and further precipitated with 4X (w/v)

acetone and incubated at -20˚C overnight. Prior to MS2

analysis, protein pellets were washed two more times with

acetone.

Sample processing for MS2

analysis

Proteins in samples were denatured with 6 M urea, 2

M thiourea and 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, and then reduced with

10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 1 h at room temperature (RT) and

alkylated at RT in the dark with 30 mM iodoacetamide. Alkylation

was halted with 10 mM DTT for 15 min at RT. Protein concentration

was determined using Pierce 660 nm Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Proteins from each sample were digested with trypsin (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) in a sequential digestion. Trypsin was added at a

1:100 enzyme to protein mass ratio. The first digest was incubated

at 37˚C for 5 h, and the second digest was incubated overnight. The

digested peptides were terminated with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)

0.5%. For total protein quantification, 5-µg of peptide from each

sample was combined for spectral library using the method for

data-dependent acquisition with parallel accumulation-serial

fragmentation (DDA-PASEF). Subsequently, 500 ng peptides from each

sample were loaded to the liquid chromatography-MS and analyzed

using the method for data-independent acquisition (DIA-PASEF).

To create a comprehensive spectral library, digested

peptides were combined from each sample and fractionated using a

high pH reversed-phase peptide fractionation kit according to the

manufacturer's protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A total

of eight fractions were collected, lyophilized and resuspended with

0.1% formic acid in deionized water.

For proteome analyses, an EvoSep One liquid

chromatography system was used as described previously (56) and the peptides were analyzed by

eluting with a 44 min gradient or EvoSep One 30 samples per day

(SPD) program. The system used a 15 cm x 150 µm ID column with 1.5

µm C18 beads (Bruker PepSep) and a 20 µm ID zero dead volume

electrospray emitter (Bruker Daltonics). Mobile phases A and B were

0.1% formic acid in water and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile,

respectively. EvoSep One was coupled online to a modified trapped

ion mobility spectrometry quadrupole time-of-flight mass

spectrometer (timsTOF Pro 2, Bruker Daltonics) via a nano

electrospray ion source (Captivespray, Bruker Daltonics). To

generate a spectral library, eight high-pH reversed-phase

fractionated samples were analyzed by timsTOF Pro 2 in the

DDA-PASEF mode. PASEF and TIMS were set to ‘on’. One MS and ten

PASEF frames were acquired per cycle of 1.17 sec (~1 MS and 120

MS2). Target intensity for MS was set at 10,000

counts/sec with a minimum threshold of 2,500 counts/sec. Duty cycle

was locked to 100%. Ion mobility coefficient (1/K0) value was set

from 0.6 to1.6 V.s/cm2, collision energy was set from 20-59 eV. MS

data were collected over m/z range of 100 to 1,700. If the

precursor (within mass width error of 0.015 m/z) had >4X signal

intensity in subsequent scans, a second MS2 spectrum was

collected. Exclusion was active after 0.4 min. Isolation width was

set to 2 for m/z <700 m/z or 3 m/z for m/z >700.

The DIA-PASEF method was optimized with py_diAID, as

described previously (57), to

cover an m/z range from 300 to 1,350 Da and an ion mobility range

of 0.65 to 1.45 V.s/cm2. The method includes two IM windows per

DIA-PASEF scan with variable isolation window widths adjusted to

the precursor densities. A total of 25 DIA-PASEF scans were

deployed at a throughput of 30 SPDs (cycle time: 2.76 sec).

MS2 statistical

analysis

Data were analyzed with Spectronaut version 17

(Biognosys AG) with the default settings, except for the

prototypicity filter, which was set to ‘only protein group

specific’. Protein quantification and statistical analysis were

performed using MSstats. The MSstat set up included protein

quantification using the top 3 features, a q-value cutoff of 0.01,

the use of unique peptides, and the removal of protein with only

one feature. No imputation was used, and the data were

log2-transfered based on MS2 peak area.

Normalization was performed using the ‘equalize medians’

method.

Quantitative MS2 analysis

and bioinformatics

AGE supplementation-induced molecular phenome

changes in SDS-insoluble protein were evaluated by computing the

expression ratio and P-value for all MS2-identified

proteins from AGE mice relative to age-matched controls. The

expression ratio threshold was set to >1.3 and <0.77 for

respective increased and decreased proteins (P<0.05). For data

visualization, expression ratios and p values were log-transformed

to produce fold-change (log2 expression ratio) and

-log10 P-value.

The differentially changed proteins in AGE mice

cortex and hippocampus were imported into Ingenuity Pathway

Analysis (IPA; Redwood City, CA; RRID:SCR_008653) for canonical

pathway analysis, machine learning-driven disease pathway analysis,

upstream regulator analysis, and neurological behavior prediction.

Additionally, comparative analysis was performed by combining

expression profiles from AGE mice cortex and hippocampus to obtain

2x2 comparisons for top pathways. The data are licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International

License (CC BY-NC 4.0).

Results

Effects of AGE supplementation on the

general health of aging mice and sensorimotor function

No significant differences in average food intake or

body weight (Figs. S2 and S3, respectively) were observed when

comparing the AGE-supplemented diet-fed mice with the control

diet-fed mice. Additionally, no changes in mortality or apparent

abnormalities in general health were found in the mice during the

40-week feeding period. Neither group exhibited any significant

decrease in body weight throughout the study. The maximum observed

body weight loss occurred at the 34th feeding-week, with a weight

loss of ~8.1% in the AGE diet-fed group and 6.0% in the control

diet-fed group compared with the 1st feeding-week.

The SNAP test was used to assess the impact of AGE

supplementation on the sensorimotor function of the aging mice. The

inverted screen grip test was performed to assess the effects of

AGE on physical strength. No statistically significant differences

in coordination, motor strength, proprioception, gait and mental

status were observed following 40-week dietary AGE supplementation

(Fig. S4).

Effects of AGE supplementation on

anxiety and neophobia

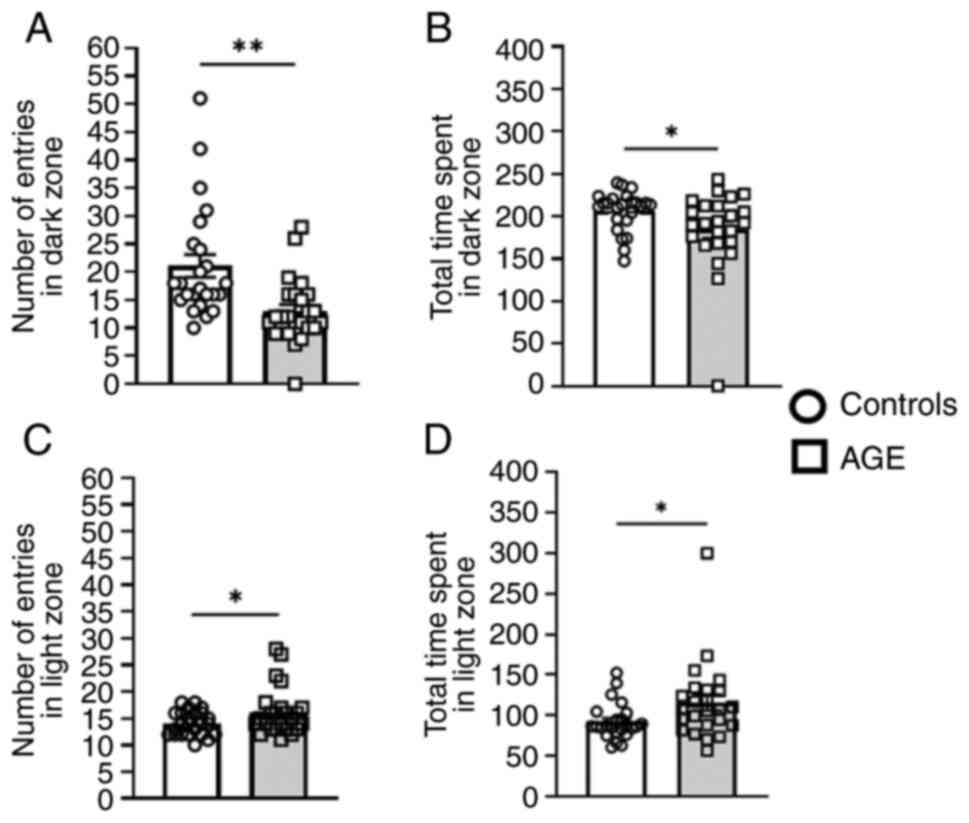

Mice fed the AGE diet exhibited less anxiety in the

light-dark transition test and reduced neophobia-like behaviors in

the emergence test. These mice exhibited a decreased number of

entries (Fig. 1A; P<0.01) and

time spent in the dark zone (Fig.

1B; P=0.046) relative to the aging controls. Furthermore, the

AGE group exhibited an increased number of entries (Fig. 1C; P<0.05) and time spent in the

light zone (Fig. 1D; P=0.034).

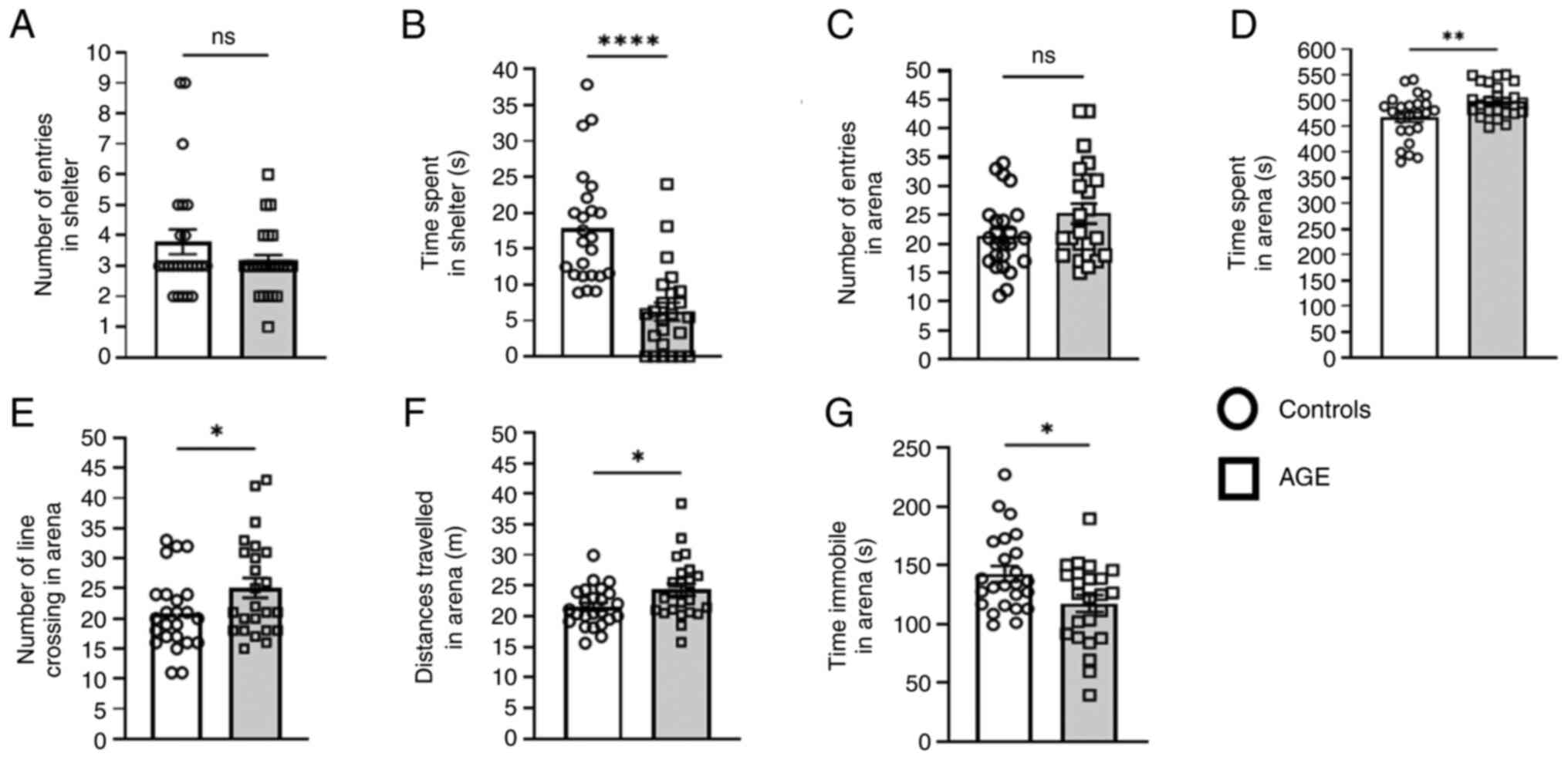

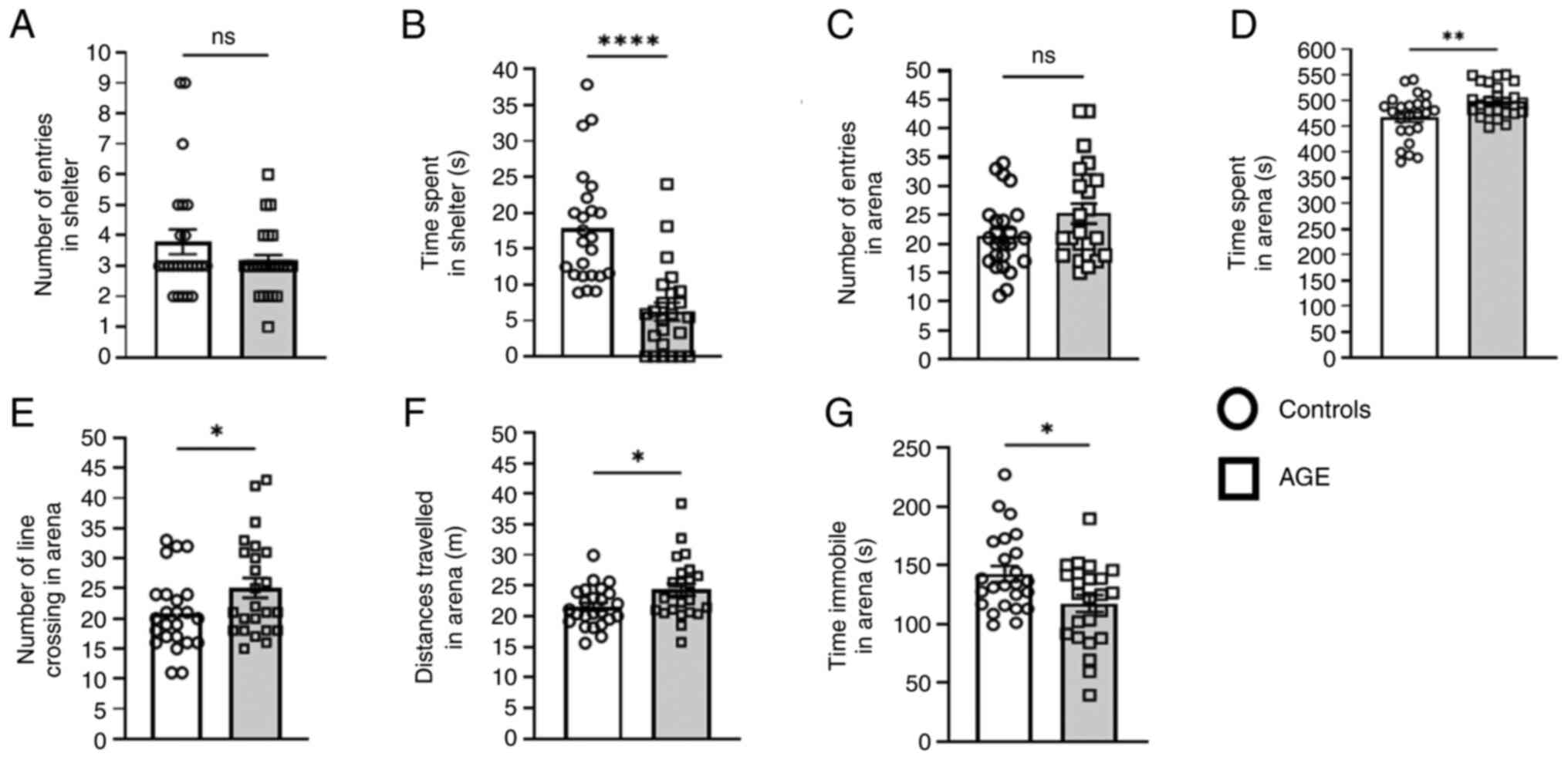

The AGE-supplemented diet-fed group also exhibited

less anxiety and neophobia and increased exploratory behavior in

the emergence test (Fig. 2A-G),

with statistically significant differences in the following

parameters: Less time spent in the shelter zone, more time spent in

the arena zone, higher number of line crossings in the arena zone,

longer distance travelled in the arena and less time immobile in

the arena zone. However, no differences were observed between the

AGE-supplemented and control diet groups in the open field test

(Fig. S5A-C), as well as the

elevated plus maze and zero maze tests (Fig. S6A-F).

| Figure 2Effects of AGE supplementation on

neophobia behaviors. The emergence test was used to measure (A)

number of entries into shelter, (B) time spent in shelter, (C)

number of entries into arena, (D) time spent in arena, (E) number

of line crossings in arena, (F) distance travelled in arena and (G)

time immobile in the arena. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

Groups: Control, n=24; AGE diet, n=24. Significantly different from

age-matched control group, *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ****P<0.0001. AGE, aged

garlic extract; ns, not significant. |

Effects of AGE supplementation on

exploratory behavior, learning and memory

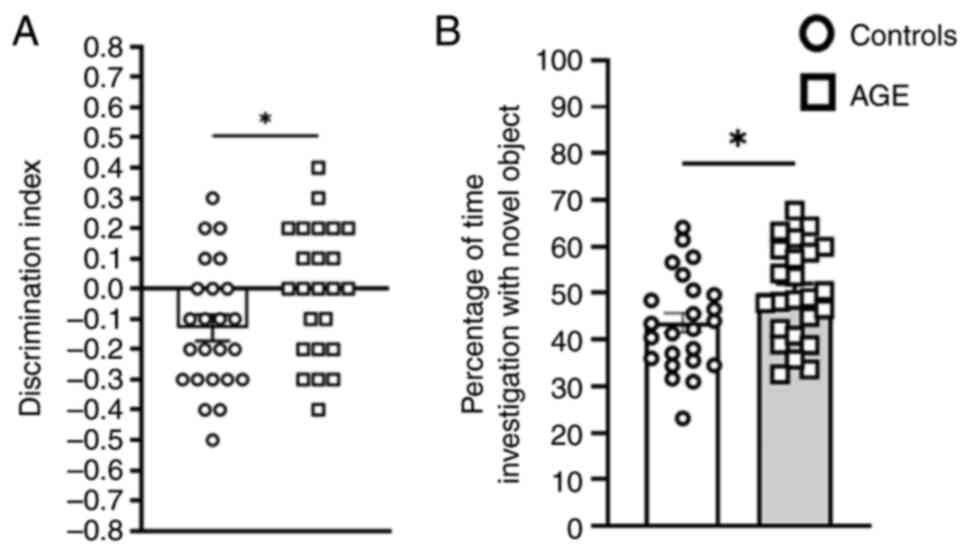

In the NOR test to evaluate ability of non-spatial

learning and recognition memory under the cognition behavioral

domain, AGE-supplemented mice displayed a greater DI (Fig. 3A; P=0.027), and increased percentage

of investigation time with the novel object location (Fig. 3B; P=0.039), indicating AGE

supplementation could improve learning levels, memory and

exploratory behaviors in aging mice.

Effects of AGE supplementation on

cognition and spatial reference learning in aging mice

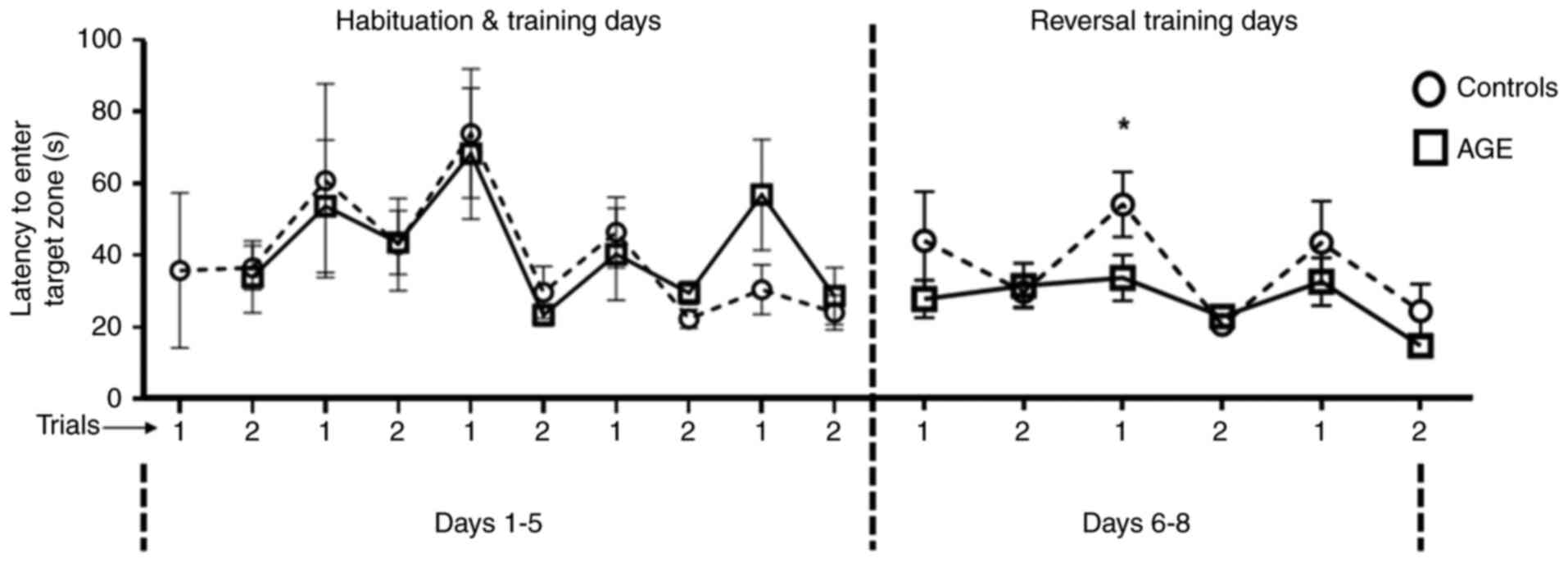

It was assessed if AGE supplementation could improve

spatial reference learning abilities in aging mice. During the

5-min Barnes maze test, a higher percentage of mice in the AGE

diet-fed group found the hiding box for acquired learning compared

with that in the control group. For those that found within the

allotted time, the latency to enter the hiding box was used to

estimate memory and learning abilities. In reversal training,

AGE-supplemented diet-fed mice displayed a shorter latency to enter

the target zone compared with mice in the control group. The

differences were most pronounced in trial 1 on day 2 of reversal

training (Fig. 4).

The present study evaluated whether AGE

supplementation could improve social recognition, sociability and

novelty preference behavior. The three-chamber social interaction

test was used for evaluating impact of AGE on the social index of

aging mice (time spent with stranger mouse 1 vs. empty cages) and

on the novelty preference index [time spent with familiar (stranger

mouse 1) vs. stranger mouse 2]. In the present study, AGE

supplementation did not improve cognitive domain parameters

(Fig. S7A and B) under the current conditions.

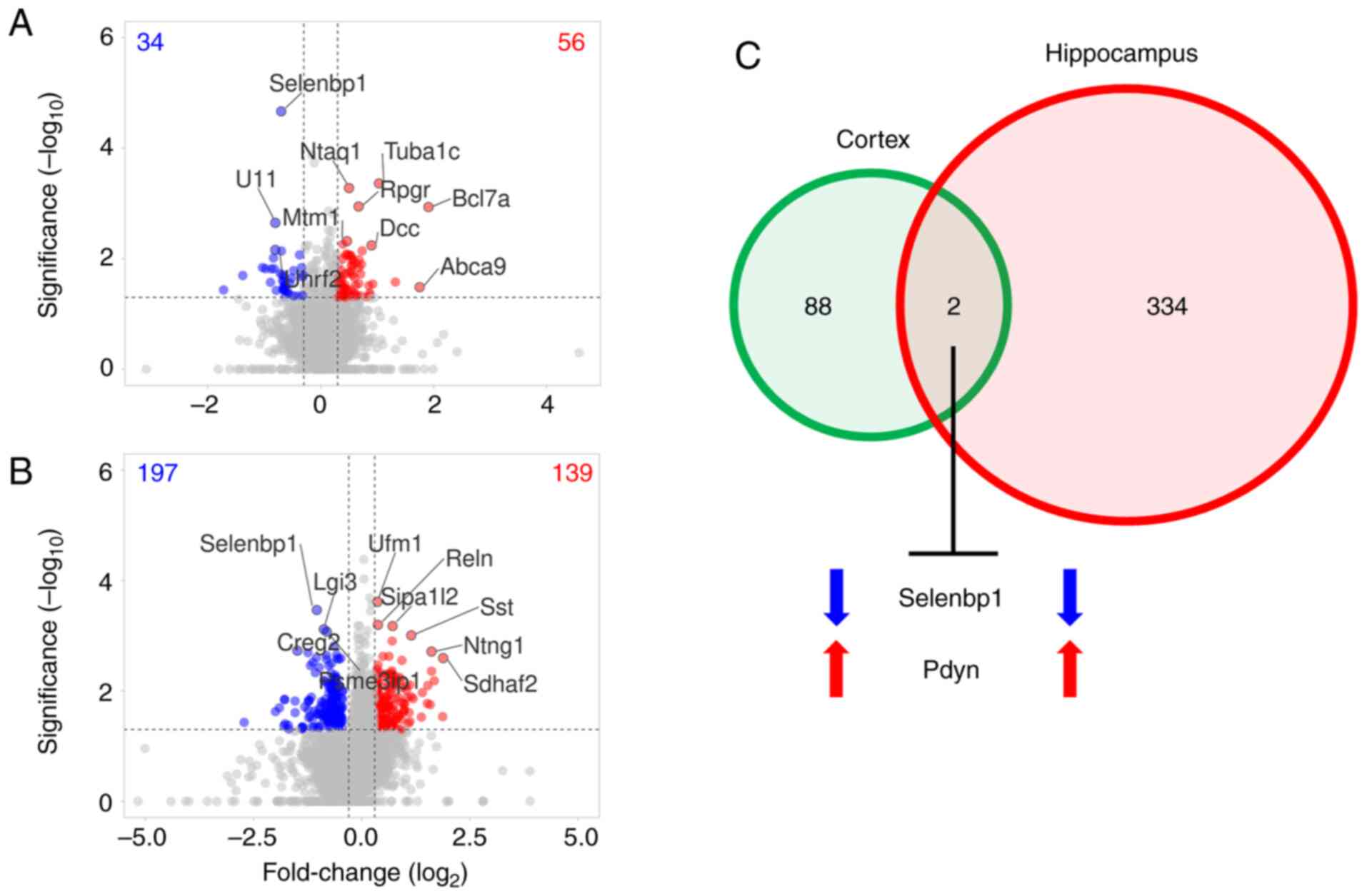

Effects of AGE supplementation on

proteomes are most pronounced in the hippocampus

The brain proteomic profiles were examined to

identify the molecular effects of AGE supplementation in aging

mice. Of 5,863 and 5,826 proteins identified using label-free

MS2, 90 and 336 proteins were significantly changed in

the AGE-supplemented mouse cortex and hippocampus, respectively

(Fig. 5A and B; Table

SI). A total of 34 and 197 proteins were decreased in the

cortex and hippocampus, respectively, whereas 139 and 56 proteins

were increased in the cortex and hippocampus, respectively.

Notably, dietary AGE supplementation decreased selenium-binding

protein 1 (Selenbp1; fold-change in the cortex, -0.700;

P=2.156x10-5; fold-change in the hippocampus, -1.039;

P=3.415x10-5) and increased prodynorphin (Pdyn;

fold-change in the cortex, 0.734; P=0.007; fold-change in the

hippocampus, 1.035; P=0.010) in both brain regions (Fig. 5C).

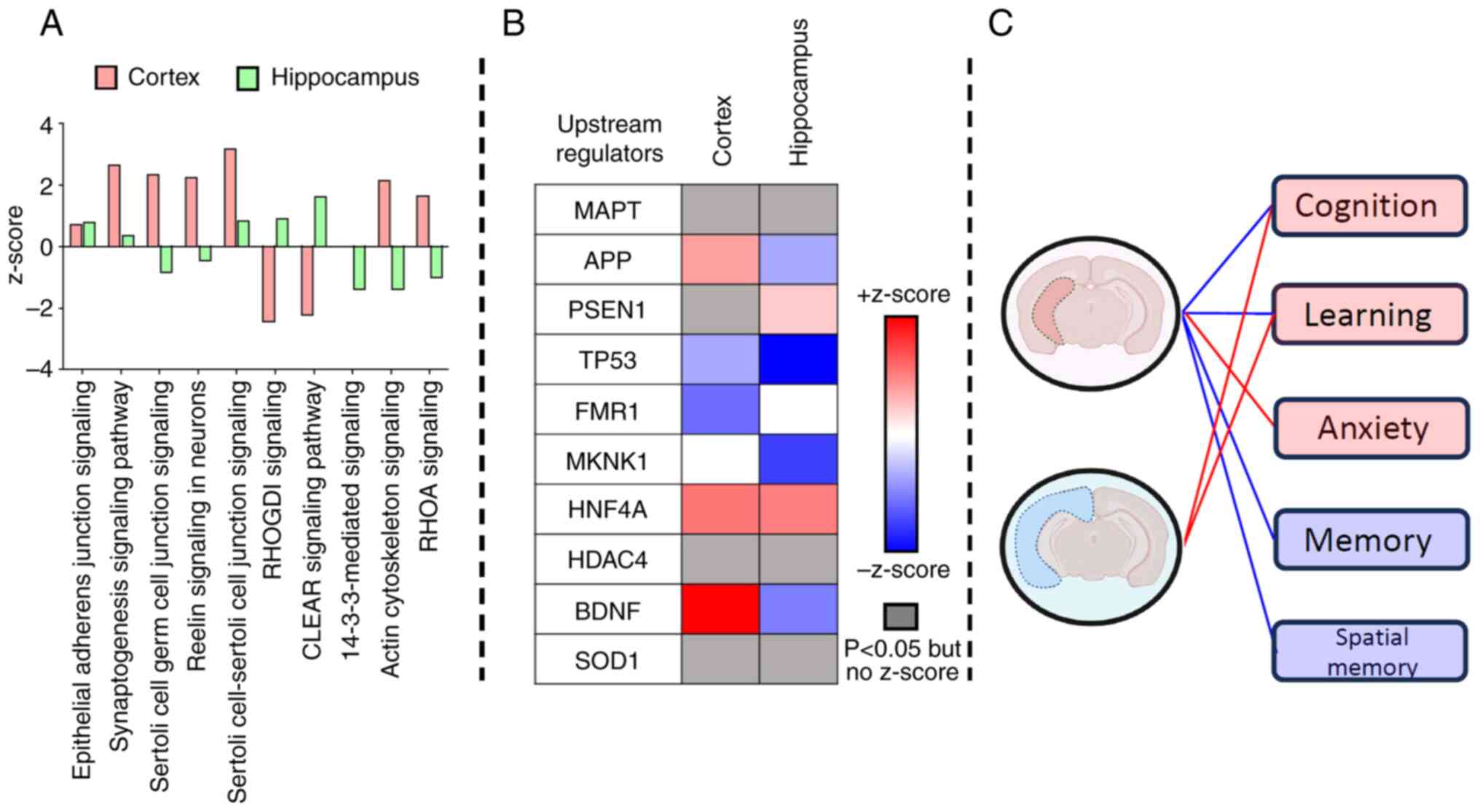

IPA predicts altered mouse phenomes in

AGE-supplemented diet-fed mice

With the bioinformatics tool to examine mouse

phenomes, which refers to a full set of observable traits (for

example, behavior, physiology and/or disease susceptibility), IPA

was able to use curated proteomic datasets to forecast changes in

phenotypic outcomes. IPA comparative analysis showed that molecular

pathways in both the cortex and hippocampal regions were similarly

impacted but with some important distinctions. The commonly

affected pathways were ‘epithelial adherens junction signaling’

(increased; P<0.05), ‘synaptogenesis signaling pathway’

(increased; P<0.05) and ‘Sertoli cell-Sertoli cell junction

signaling’ (increased; P<0.05) (Fig.

6A; Table SII, sheet:

Canonical pathways). Among the top canonical pathways,

14-3-3-mediated signaling related to apoptosis was impacted

exclusively in the AGE-supplemented hippocampus (z-score, -1.387;

P=1.362x10-5) (Fig. 6A;

Table SII, sheet: Canonical

pathways). IPA upstream regulator analysis predicted

microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) to be most impacted by

dietary AGE supplementation based on P-value ranking, and this

occurred mostly in the hippocampus (cortex P=0.007; hippocampus

P=1.212x10-14) (Fig. 6B;

Table SII, sheet: Upstream

regulators). Amyloid precursor protein (APP) and brain-derived

neurotrophic factor (BDNF) were predicted to be increased in the

cortex and reduced in the hippocampus (Fig. 6B; Table

SII, sheet: Upstream regulators). Presenilin 1 (PSEN1) was

exclusively increased in the hippocampus (z-score, 0.658;

P=1.992x10-10) (Fig. 6B;

Table SII, sheet: Upstream

regulators). The p53 cell-cycle regulator was reduced in both the

cortex (z-score, -0.442; P=0.002) and hippocampus (z-score, -1.781;

P=1.917x10-8) (Fig. 6B;

Table SII, sheet: Upstream

regulators). IPA behavior predictions suggested that differential

expression changes in the cortex and hippocampus proteomes due to

AGE supplementation could impact cognition and learning, whereas

only changes to the hippocampus proteomes could impact anxiety,

memory and spatial memory (Fig. 6C;

Table SII, sheet: Behavior

prediction).

Discussion

In the natural aging process, there is a

well-documented decline in cognition and memory function. Based on

existing literature, a strong argument can be made that AGE, along

with its bioactive components, may delay cognitive impairment, and

thereby improve the behavioral phenotype associated with aging

(30,58-61).

As reported by Song et al (35), garlic (Allium sativum),

particularly in the form of AGE, contains nutraceutical

constituents such as SAC, S-allyl-mercapto-cysteine (SAMC) and

FruArg. SAC and SAMC, prominent organosulfur compounds, exhibit

potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic activities

that are consistent with the observed downregulation of

TP53-mediated apoptotic regulators and enhancement of

BDNF-associated neurotrophic signaling. FruArg, a carbohydrate

derived from garlic via the Maillard reaction, exhibits blood-brain

barrier permeability and transcriptional regulatory potential. In

lipopolysaccharide-stimulated microglial models, AGE and FruArg

reversed 67 and 55% of transcriptomic alterations, respectively,

implicating pathways such as Toll-like receptor signaling, IL-6 and

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 pathways. These

findings strengthen the mechanistic framework linking AGE

bioactivities to both region-specific proteome shifts and the

behavioral improvements reported, highlighting the potential of

AGE-derived compounds in attenuating inflammatory activities and

enhancing brain resilience.

SAC has been shown to attenuate oxidative stress and

prevent neuronal cell death in models of neurodegeneration, while

SAMC has demonstrated the ability to modulate gene expression

related to mitochondrial function and cellular survival. Building

on these findings, the present experiments suggested that the

anxiolytic and cognitive benefits observed following AGE

supplementation may, at least in part, be mediated by the actions

of these sulfur-containing compounds and carbohydrate derivatives

on key signaling pathways involved in neuronal health and

plasticity.

Although evidence in humans is still being

developed, preclinical studies using different aging-related rodent

models have shown that AGE supplementation could improve cognition

through its neuroprotective molecular effects on antioxidant

enzymes (58-60),

resilience to amyloid-β toxicity (30,58,60,61),

and by promoting hippocampal neuroplasticity via modulation of

neurotransmitter receptor expression (30). These findings underscore the

potential for AGE to improve human health by altering the

aging-related brain pathology.

In the present study involving multi-faceted

behavioral experiments, aging mice given a diet supplemented with

AGE for >40 weeks showed improvements in age-related decline in

learning and spatial and working memory assessed in the Barnes maze

and NOR tests. These findings are in agreement with results from a

previous study using the passive avoidance test, which showed

improvements in scopolamine-induced amnesia in mice fed with crude

garlic extract (Lasuna) at 10 ml/kg body weight per os for

21 days (62). In another study

using the senescence-accelerated mouse model of aging, mice fed an

AGE diet for 8 months also showed amelioration of memory

acquisition deficits and memory retention impairments compared with

the age-matched controls without AGE supplementation (63). These data suggest that, in the

setting of natural and induced aging models, supplementation of AGE

can improve cognition and memory. AGE supplementation has also been

shown to attenuate cognitive impairment in the setting of

neurodegeneration (30,58,64,65).

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is among the first

to comprehensively assess multi-domain behavioral functions,

demonstrating that a 40-week AGE supplementation regimen could

enhance cognition and memory, and mitigate age-associated cognitive

decline.

Anxiety and related symptoms such as restlessness,

psychomotor agitation and excessive worrying are frequently

encountered in later life (66).

The current options for the treatment of aging-related anxiety

disorders encompass lifestyle modifications, behavioral and

cognitive therapies, mindfulness-based interventions, and/or

pharmacological treatment, including selective serotonin receptor

inhibitors, non-selective serotonin receptor inhibitors and

benzodiazepines (66). However,

these medications are often associated with severe side effects,

further complicating the management of age-related anxiety

(66). In the present study,

dietary supplementation of AGE could reduce anxiety-like behaviors

as manifested by reduced neophobia (fear of new things) and

increased exploratory behavior in the emergence test. These results

are consistent with a previous study demonstrating the potential of

AGE to alleviate anxiety associated with natural aging. A study by

Gilhotra and Dhingra (67)

investigated the neurochemical mechanisms underlying the anxiolytic

effects of garlic extract in mice. Their study focused on GABAergic

and nitrergic signaling pathways and employed behavioral paradigms

such as the elevated plus maze and the light-dark box test,

demonstrating that garlic extract reduced anxiety-like

behaviors.

Building on these behavior observations, the present

study leveraged machine learning-driven IPA to investigate the

molecular mechanisms underlying the anxiolytic effects of AGE.

Notably, the anti-anxiety potential of AGE may be linked to its

antioxidant properties, modulation of neurotransmitter systems and

anti-inflammatory effects. In particular, in Fig. 6 it is illustrated that several

upstream regulators, including TP53, MAPK interacting

serine/threonine kinase 1 (MKNK1) and BDNF, and their signaling

pathways relevant to neurobehavioral functions, were differentially

modulated in a region-specific manner following AGE

supplementation. In IPA, the z-score is a crucial statistic used to

infer the likely activation state (activation or inhibition) of

upstream regulators, which is based on the expression or

phosphorylation patterns of its downstream target molecules. As

shown in Fig. 6B, TP53 and MKNK1

exhibited strong negative z-scores in the hippocampus, suggesting

suppression of stress- or apoptosis-related signaling. Conversely,

BDNF was positively regulated in the cortex. These regulatory

changes may contribute to the anxiolytic effects of AGE by

modulating neuroplasticity, promoting neuroprotection or adjusting

stress-response pathways. These molecular changes with behavioral

domains are further contextualized in Fig. 6C, highlighting that the pathways

linked to anxiety were differentially impacted between the cortex

and hippocampus. More detailed mechanistic insights are presented

subsequently.

IPA analysis of AGE-induced differential protein

expression in the cortex and hippocampus predicted significant

changes in the key regulatory proteins MAPT, APP, PSEN1 and BDNF,

which likely mediate the distinct proteomic changes associated with

AGE supplementation through upstream regulation.

MAPT is normally increased in aging brains, and its

phosphorylation is associated with cognitive decline in AD

(68,69). MAPT was identified as a top upstream

regulator based on P-value ranking within the IPA framework,

reflecting significant enrichment of its downstream targets among

the differentially expressed proteins (P<0.01). While the

z-score is applied across regulators, it requires concordant

directionality between predicted effects and observed expression

changes. In the present dataset, MAPT-associated targets exhibited

mixed directional trends, resulting in a non-significant z-score

despite strong enrichment. MAPT expression itself did not differ

significantly between the cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 6B); rather, the analysis highlighted

its inferred regulatory influence. Notably, a greater number of

MAPT-related targets were differentially expressed in the

hippocampus, pointing to a region-specific sensitivity of

MAPT-regulated pathways to dietary AGE supplementation. Future

studies are needed to validate the directionality and potential

post-translational modifications of MAPT in response to AGE

treatment. Although directionality could not be assessed, MAPT

emerged as the most significant upstream regulator of molecular

changes in the hippocampus (-log10 BH-P-value=13.916),

compared with its regulatory impact in the cortex

(-log10 BH-P-value=2.143). Notably, >75% of proteins

were differentially altered due to AGE supplementation.

APP can be cleaved by β- and γ-secretases, resulting

in producing different amyloid-β variants in AD (70). Based on IPA, this protein was

predicted to be reduced in the hippocampus (z-score, -0.445;

-log10 BH-P-value=10.128) but not in the

AGE-supplemented mouse cortex (z-score, 2.714; -log10

BH-P-value=0.945). This prediction suggests a potential ability of

AGE to prevent the formation of AD plaques and possibly protect

against memory impairment.

PSEN1 or γ-secretase constitutes the catalytic

subunit of the γ-secretase complex, and its loss of function due to

mutations has been implicated in amyloid-β plaque formation and AD

pathogenesis (71). The increase in

PSEN1 in the hippocampus (z-score, 0.658; -log10

BH-P-value=9.701) due to AGE supplementation may be a protective

mechanism to counteract age-related memory loss.

BDNF is a key regulator for neuronal survival and

growth, neurotransmitter modulation and neuronal plasticity, which

are essential for learning and memory (72). Upon exogenous administration, BDNF

has been shown to participate in learning-related events, memory,

depression and cognition (73,74).

BDNF mRNA and protein levels are normally reduced in the cortex and

hippocampus of older adults relative to younger adults and infants

and are positively correlated with brain tissue volume (72,74).

In post-mortem AD brains, BDNF is globally reduced in the cortex

and hippocampus (72). In the

present study, AGE supplementation significantly increased cortical

BDNF (z-score, 2.030; -log10 BH-P-value=5.423),

suggesting that the AGE effects may preserve the cortical neurons,

thus attenuating the age-related decline in cognitive function and

short-term memory.

Comparative analysis of the commonly changed

pathways in the cortex and hippocampus revealed an increase in

synaptogenesis signaling in both brain regions, albeit mostly in

the cortex. In aged rodents and primates, loss of synaptic spines

in the hippocampus and cortex is known to reduce neural firing

rates during working memory tasks and to reduce non-synaptic bouton

density associated with learning deficits (75). A study showed that AGE

supplementation attenuates oxidative stress and amyloid pathology,

restores cortical and hippocampal synaptic proteins, such as

synaptophysin and synaptosome associated protein 25, as well as

enhanced cognition and memory (76).

In the hippocampus, AGE supplementation was found to

reduce 14-3-3 signaling pathways linked to apoptosis and

chaperone-mediated autophagy. Aberration of 14-3-3 signaling

pathways has been reported in aging, neurodegenerative diseases and

cancer (77). Aging has been shown

to disturb 14-3-3 chaperone and macroautophagic signaling activity,

which resulted in the accumulation of toxic molecular constituents,

including MAPT, amyloid-β and α-synuclein (77). Consequently, using AGE

supplementation to target 14-3-3 signaling may be a novel mechanism

to attenuate neuron cell death during the natural aging

process.

In conclusion, the present study revealed the

neuroprotective effects of dietary supplementation of AGE in

improving age-related cognitive decline and anxiety-like behaviors

in aging mice. Modulation of MAPT, APP, PSEN1 and BDNF further

suggested the ability of AGE to confer neuroprotective effects

against age-related neurodegeneration. Proteomic analysis

highlighted the increase in synaptogenesis and reduction in

apoptotic signaling, supporting the notion of AGE supplementation

as a nutraceutical to mitigate age-related cognitive decline. While

these findings provide promising insights into the molecular

changes induced by AGE, further validation is essential to

strengthen the present conclusions. To corroborate the proteomic

data, additional validation experiments using both western blotting

and immunohistochemical analyses, as well as other complementary

assays, will be performed in future studies. Understanding these

mechanisms can offer promising avenues for interventions in

age-related neurological disorders. Further research into the

translational potential of AGE-based interventions is warranted to

address the increasing disease burden of aging-associated cognitive

impairments and neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Study timeline including the AGE

feeding, behavior test duration, and tissue collection for global

proteomics are presented along with a list of the behavior tests

performed to assess AGE effects on motor function; anxiety,

neophobia and exploratory; and other cognition behavioral domains.

AGE, aged garlic extract; SNAP, simple neuro-assessment of

asymmetric impairment.

Effects of AGE supplementation on food

consumption. (A) Weekly food consumption and (B) bi-weekly food

consumption per body weight (grams/grams) for AGE mice (square with

solid lines) and controls (circle with dash lines). Data are

presented as the mean ± SEM. Groups: AGE, n=24; Controls, n=24.

AGE, aged garlic extract.

Effects of AGE supplementation on body

weight. Weekly gain in body weight data is presented as the mean ±

SEM. Groups: AGE, n=24; Controls, n=24. AGE, aged garlic

extract.

Effects of AGE supplementation on

gross motor function and strength. (A) Results from the simple

neuro-assessment of asymmetric impairment and (B) inverted screen

grip test. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Groups: AGE, n=24;

Controls, n=24. AGE, aged garlic extract; ns, not significant.

Effects of AGE supplementation on

locomotion-related anxiety-like behaviors. Results from the tested

open-field maze parameters showing AGE effects on (A) total time

spent in center zone, (B) total distance traveled in center zone,

and (C) distance traveled in center zone per minute. Data are

presented as the mean ± SEM. Groups: AGE, n=24; Controls, n=24.

AGE, aged garlic extract; ns, not significant.

Effects of AGE supplementation on

explorative-related anxiety-like behaviors. Results shown in (A-C)

represent the elevated plus maze and (D-F) represent the zero maze

to evaluate anxiety-like behaviors. (A and D) Time spent in open

arms/segments, (B and E) percentage of time spent in open

arms/segments, and (C and F) time spent in closed arms/segments

were measured. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Groups: AGE

(n=24) and Control (n=24). AGE, aged garlic extract; ns, not

significant.

Effects of AGE supplementation on

sociability. Results from the three-chamber social interaction test

including mice for (A) sociability and (B) novelty preferences.

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Groups: AGE, n=24; Controls,

n=24. AGE, aged garlic extract; ns, not significant.

Raw and processed global proteomics

data

Comparative analysis results (DE

groups: AGE vs Control; Comparison groups: Cor-tex vs Hippocampus)

from ingenuity pathway analysis

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Dennis K. Miller,

Associate Teaching Professor, Department of Psychology Sciences,

University of Missouri College of Arts & Science, for his

technical guidance in the setup of some neurobehavioral

assessments.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported in part by the Wakunaga

Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (grant no. 00078665) and by the University

of Missouri School of Medicine (grant no. C2654010-C8904-0595).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The data generated in the

present study may be found in the Figshare under accession number

30066604 or at the following URL: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30066604.

Authors' contributions

MT and MJ developed methodology, validated and

curated data, conducted formal analysis and investigation, and

wrote the original draft. MJ visualized data. AZ conducted formal

analysis and investigation. WY validated and curated data. TTN

conducted formal analysis and investigation. AB conducted

investigation, validated and curated data. RL conducted

investigation and validated data. GYS contributed to data

interpretation, provided constructive criticism during the revision

process, and approved the final version. JC conceptualized the

study, developed methodology, validated data, performed formal

analysis, conducted investigation and project administration, and

curated data. ZG conceptualized and supervised the study, developed

methodology, performed software and formal analysis, visualized,

validated and curated data, conducted investigation and project

administration, provided resources, wrote the original draft, and

acquired funding. MT, MJ, AZ, WY, TTN, GYS, JC and ZG wrote,

reviewed and edited the manuscript. JC and ZG confirm the

authenticity of the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experimental procedures involving mice were

conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the

University of Missouri School of Medicine and the national

guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. The study

protocol was reviewed and approved (approval no. 25120) by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the

University of Missouri School of Medicine (Columbia, USA).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Financial support was received from Wakunaga

Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., however the funding agent had no

influence on the research, results, or interpretation of the study.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

|

1

|

Bureau USC: 2023 National Population

Projections Tables: Main Series, 2023.

|

|

2

|

No authors listed. 2023 Alzheimer's

disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 19:1598–1695.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA and Evans

DA: Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010-2050) estimated

using the 2010 census. Neurology. 80:1778–1783. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Bartzokis G, Cummings JL, Sultzer D,

Henderson VW, Nuechterlein KH and Mintz J: White matter structural

integrity in healthy aging adults and patients with Alzheimer

disease: A magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Neurol.

60:393–398. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Toescu EC, Verkhratsky A and Landfield PW:

Ca2+ regulation and gene expression in normal brain aging. Trends

Neurosci. 27:614–620. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Melov S: Modeling mitochondrial function

in aging neurons. Trends Neurosci. 27:601–606. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Murman DL: The impact of age on cognition.

Semin Hear. 36:111–121. 2015.

|

|

8

|

Xia X, Jiang Q, McDermott J and Han JJ:

Aging and Alzheimer's disease: Comparison and associations from

molecular to system level. Aging Cell. 17(e12802)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Yoshimura N, Tsuda H, Aquino D, Takagi A,

Ogata Y, Koike Y and Minati L: Age-related decline of sensorimotor

integration influences resting-state functional brain connectivity.

Brain Sci. 10(966)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Heavener KS and Bradshaw EM: The aging

immune system in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Semin

Immunopathol. 44:649–657. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Yaniv Z and Bachrach U: Handbook of

Medicinal Plants. 1st Edition. Haworth Medical Press, Inc. New

York, 2005.

|

|

12

|

Amagase H: Clarifying the real bioactive

constituents of garlic. J Nutr. 136 (3 Suppl):716S–25S.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Amagase H, Petesch BL, Matsuura H, Kasuga

S and Itakura Y: Intake of garlic and its bioactive components. J

Nutr. 131 (3S):955S–962S. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Elosta A, Slevin M, Rahman K and Ahmed N:

Aged garlic has more potent antiglycation and antioxidant

properties compared to fresh garlic extract in vitro. Sci Rep.

7(39613)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Song H, Cui J, Mossine VV, Greenlief CM,

Fritsche K, Sun GY and Gu Z: Bioactive components from garlic on

brain resiliency against neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration.

Exp Ther Med. 19:1554–1559. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Das D, M K, Mitra A, Zaky MY, Pathak S and

Banerjee A: A review on the efficacy of plant-derived bio-active

compounds curcumin and aged garlic extract in modulating cancer and

age-related diseases. Curr Rev Clin Exp Pharmacol. 19:146–162.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Gadidala SK, Johny E, Thomas C, Nadella M,

Undela K and Adela R: Effect of garlic extract on markers of lipid

metabolism and inflammation in coronary artery disease (CAD)

patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytother Res.

37:2242–2254. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ried K: Garlic lowers blood pressure in

hypertensive subjects, improves arterial stiffness and gut

microbiota: A review and meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med. 19:1472–1478.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Varshney R and Budoff MJ: Garlic and heart

disease. J Nutr. 146:416S–421S. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Wlosinska M, Nilsson AC, Hlebowicz J,

Hauggaard A, Kjellin M, Fakhro M and Lindstedt S: The effect of

aged garlic extract on the atherosclerotic process-a randomized

double-blind placebo-controlled trial. BMC Complement Med Ther.

20(132)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Asdaq SMB, Challa O, Alamri AS, Alsanie

WF, Alhomrani M, Almutiri AH and Alshammari MS: Cytoprotective

potential of aged garlic extract (AGE) and its active constituent,

S-allyl-l-cysteine, in presence of carvedilol during

isoproterenol-induced myocardial disturbance and metabolic

derangements in rats. Molecules. 26(3203)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Lin KH, Ng SC, Lu SY, Lin YM, Lin SH, Su

TC, Huang CY and Kuo WW: Diallyl trisulfide (DATS) protects cardiac

cells against advanced glycation end-product-induced apoptosis by

enhancing FoxO3A-dependent upregulation of miRNA-210. J Nutr

Biochem. 125(109567)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Gruenwald J, Bongartz U, Bothe G and

Uebelhack R: Effects of aged garlic extract on arterial elasticity

in a placebo-controlled clinical trial using EndoPAT™

technology. Exp Ther Med. 19:1490–1499. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Hamal S, Cherukuri L, Birudaraju D,

Matsumoto S, Kinninger A, Chaganti BT, Flores F, Shaikh K, Roy SK

and Budoff MJ: Short-term impact of aged garlic extract on

endothelial function in diabetes: A randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial. Exp Ther Med. 19:1485–1489.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Hutchins E, Shaikh K, Kinninger A,

Cherukuri L, Birudaraju D, Mao SS, Nakanishi R, Almeida S,

Jayawardena E, Shekar C, et al: Aged garlic extract reduces left

ventricular myocardial mass in patients with diabetes: A

prospective randomized controlled double-blind study. Exp Ther Med.

19:1468–1471. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wlosinska M, Nilsson AC, Hlebowicz J,

Fakhro M, Malmsjö M and Lindstedt S: Aged garlic extract reduces

IL-6: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial in females with a low

risk of cardiovascular disease. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2021(6636875)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Budoff MJ, Ahmadi N, Gul KM, Liu ST,

Flores FR, Tiano J, Takasu J, Miller E and Tsimikas S: Aged garlic

extract supplemented with B vitamins, folic acid and L-arginine

retards the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis: A

randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 49:101–107. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Lindstedt S, Wlosinska M, Nilsson AC,

Hlebowicz J, Fakhro M and Sheikh R: Successful improved peripheral

tissue perfusion was seen in patients with atherosclerosis after 12

months of treatment with aged garlic extract. Int Wound J.

18:681–691. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Gomez CD, Aguilera P, Ortiz-Plata A, López

FN, Chánez-Cárdenas ME, Flores-Alfaro E, Ruiz-Tachiquín ME and

Espinoza-Rojo M: Aged garlic extract and S-allylcysteine increase

the GLUT3 and GCLC expression levels in cerebral ischemia. Adv Clin

Exp Med. 28:1609–1614. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Thorajak P, Pannangrong W, Welbat JU,

Chaijaroonkhanarak W, Sripanidkulchai K and Sripanidkulchai B:

Effects of aged garlic extract on cholinergic, glutamatergic and

GABAergic systems with regard to cognitive impairment in Aβ-induced

rats. Nutrients. 9(686)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Wichai T, Pannangrong W, Welbat J,

Chaichun A, Sripanidkulchai K and Sripanidkulchai B: Effects of

aged garlic extract on spatial memory and oxidative damage in the

brain of amyloid-β induced rats. Songklanakarin J Sci Technol.

41:311–318. 2019.

|

|

32

|

Moriguchi T, Saito H and Nishiyama N:

Anti-ageing effect of aged garlic extract in the inbred brain

atrophy mouse model. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 24:235–242.

1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Kim SR, Jung YR, An HJ, Kim DH, Jang EJ,

Choi YJ, Moon KM, Park MH, Park CH, Chung KW, et al: Anti-wrinkle

and anti-inflammatory effects of active garlic components and the

inhibition of MMPs via NF-κB signaling. PLoS One.

8(e73877)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Borek C: Antioxidant health effects of

aged garlic extract. J Nutr. 131 (3S):1010S–1015S. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Song H, Lu Y, Qu Z, Mossine VV, Martin MB,

Hou J, Cui J, Peculis BA, Mawhinney TP, Cheng J, et al: Effects of

aged garlic extract and FruArg on gene expression and signaling

pathways in lipopolysaccharide-activated microglial cells. Sci Rep.

6(35323)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Zhou H, Qu Z, Mossine VV, Nknolise DL, Li

J, Chen Z, Cheng J, Greenlief CM, Mawhinney TP, Brown PN, et al:

Proteomic analysis of the effects of aged garlic extract and its

FruArg component on lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammatory

response in microglial cells. PLoS One. 9(e113531)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Flurkey K, Currer JM and Harrison DE:

Chapter 20-Mouse models in aging research. In: The Mouse in

Biomedical Research (Second Edition). Fox JG, Davisson MT, Quimby

FW, Barthold SW, Newcomer CE and Smith AL (eds). Academic Press,

Burlington, pp637-672, 2007.

|

|

38

|

Laboratory TJ: When are mice considered

‘old’? The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, 2017. https://www.jax.org/news-and-insights/jax-blog/2017/november/when-are-mice-considered-old.

|

|

39

|

Hohlbaum K, Frahm S, Rex A, Palme R,

Thöne-Reineke C and Ullmann K: Social enrichment by separated pair

housing of male C57BL/6JRj mice. Sci Rep. 10(11165)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Hennessy MB, Kaiser S and Sachser N:

Social buffering of the stress response: Diversity, mechanisms, and

functions. Front Neuroendocrinol. 30:470–482. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Chen M, Song H, Cui J, Johnson CE, Hubler

GK, DePalma RG, Gu Z and Xia W: Proteomic profiling of mouse brains

exposed to blast-induced mild traumatic brain injury reveals

changes in axonal proteins and phosphorylated tau. J Alzheimers

Dis. 66:751–773. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Shelton SB, Pettigrew DB, Hermann AD, Zhou

W, Sullivan PM, Crutcher KA and Strauss KI: A simple, efficient

tool for assessment of mice after unilateral cortex injury. J

Neurosci Methods. 168:431–442. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Deacon RM: Measuring the strength of mice.

J Vis Exp: 2610, 2013.

|

|

44

|

Song H, Konan LM, Cui J, Johnson CE,

Langenderfer M, Grant D, Ndam T, Simonyi A, White T, Demirci U, et

al: Ultrastructural brain abnormalities and associated behavioral

changes in mice after low-intensity blast exposure. Behav Brain

Res. 347:148–157. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Walker JM, Klakotskaia D, Ajit D, Weisman

GA, Wood WG, Sun GY, Serfozo P, Simonyi A and Schachtman TR:

Beneficial effects of dietary EGCG and voluntary exercise on

behavior in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. J Alzheimers Dis.

44:561–572. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Siedhoff HR, Chen S, Balderrama A, Sun GY,

Koopmans B, DePalma RG, Cui J and Gu Z: Long-term effects of

low-intensity blast non-inertial brain injury on anxiety-like

behaviors in mice: Home-cage monitoring assessments. Neurotrauma

Rep. 3:27–38. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Long JB, Bentley TL, Wessner KA, Cerone C,

Sweeney S and Bauman RA: Blast overpressure in rats: Recreating a

battlefield injury in the laboratory. J Neurotrauma. 26:827–840.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Huang TN and Hsueh YP: Novel object

recognition for studying memory in mice. Bio Protoc.

4(e1249)2014.

|

|

49

|

Leibrock C, Ackermann TF, Hierlmeier M,

Lang F, Borgwardt S and Lang UE: Akt2 deficiency is associated with

anxiety and depressive behavior in mice. Cell Physiol Biochem.

32:766–777. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Lalonde R and Strazielle C: The relation

between open-field and emergence tests in a hyperactive mouse

model. Neuropharmacology. 57:722–724. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Lister RG: The use of a plus-maze to

measure anxiety in the mouse. Psychopharmacology (Berl).

92:180–185. 1987.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Kordás K, Kis-Varga Á, Varga A, Eldering

H, Bulthuis R, Lendvai B, Lévay G and Román V: Measuring

sociability of mice using a novel three-chamber apparatus and

algorithm of the LABORAS™ system. J Neurosci Methods.

343(108841)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Kim JW, Seung H, Kwon KJ, Ko MJ, Lee EJ,

Oh HA, Choi CS, Kim KC, Gonzales EL, You JS, et al: Subchronic

treatment of donepezil rescues impaired social, hyperactive, and

stereotypic behavior in valproic acid-induced animal model of

autism. PLoS One. 9(e104927)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Walker JM, Fowler SW, Miller DK, Sun AY,

Weisman GA, Wood WG, Sun GY, Simonyi A and Schachtman TR: Spatial

learning and memory impairment and increased locomotion in a

transgenic amyloid precursor protein mouse model of Alzheimer's

disease. Behav Brain Res. 222:169–175. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Jackson M, Chen S, Nguyen TT, Siedhoff HR,

Balderrama A, Zuckerman A, Li R, Greenlief CM, Cole G, Frautschy

SA, et al: The chronic effects of a single low-intensity blast

exposure on phosphoproteome networks and cognitive function

influenced by mutant tau overexpression. Int J Mol Sci.

25(3338)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Bache N, Geyer PE, Bekker-Jensen DB,

Hoerning O, Falkenby L, Treit PV, Doll S, Paron I, Müller JB, Meier

F, et al: A novel LC system embeds analytes in pre-formed gradients

for rapid, ultra-robust proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics.

17:2284–2296. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Skowronek P, Thielert M, Voytik E, Tanzer

MC, Hansen FM, Willems S, Karayel O, Brunner AD, Meier F and Mann

M: Rapid and in-depth coverage of the (phospho-)proteome with deep

libraries and optimal window design for dia-PASEF. Mol Cell

Proteomics. 21(100279)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Nillert N, Pannangrong W, Welbat JU,

Chaijaroonkhanarak W, Sripanidkulchai K and Sripanidkulchai B:

Neuroprotective Effects of aged garlic extract on cognitive

dysfunction and neuroinflammation induced by β-amyloid in rats.

Nutrients. 9(24)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Li F and Kim MR: Effect of aged garlic

ethyl acetate extract on oxidative stress and cholinergic function

of scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment in mice. Prev Nutr Food

Sci. 24:165–170. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Pannangrong W, Welbat JU, Chaichun A and

Sripanidkulchai B: Effect of combined extracts of aged garlic,

ginger, and chili peppers on cognitive performance and brain

antioxidant markers in Aβ-induced rats. Exp Anim. 69:269–278.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Jeong JH, Jeong HR, Jo YN, Kim HJ, Shin JH

and Heo HJ: Ameliorating effects of aged garlic extracts against

Aβ-induced neurotoxicity and cognitive impairment. BMC Complement

Altern Med. 13(268)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Mukherjee D and Banerjee S: Learning and

memory promoting effects of crude garlic extract. Indian J Exp

Biol. 51:1094–1100. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Nishiyama N, Moriguchi T and Saito H:

Beneficial effects of aged garlic extract on learning and memory

impairment in the senescence-accelerated mouse. Exp Gerontol.

32:149–160. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Chauhan NB and Sandoval J: Amelioration of

early cognitive deficits by aged garlic extract in Alzheimer's

transgenic mice. Phytother Res. 21:629–640. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Sripanidkulchai B: Benefits of aged garlic

extract on Alzheimer's disease: Possible mechanisms of action. Exp

Ther Med. 19:1560–1564. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Subramanyam AA, Kedare J, Singh OP and

Pinto C: Clinical practice guidelines for geriatric anxiety

disorders. Indian J Psychiatry. 60 (Suppl 3):S371–S382.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Gilhotra N and Dhingra D: GABAergic and

nitriergic influence in antianxiety-like activity of garlic in

mice. J Appl Pharm Sci. 6:077–085. 2016.

|

|

68

|

Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, Bouras

C, Braak H, Cairns NJ, Castellani RJ, Crain BJ, Davies P, Del

Tredici K, et al: Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic

changes with cognitive status: A review of the literature. J

Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 71:362–381. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Ziontz J, Bilgel M, Shafer AT, Moghekar A,

Elkins W, Helphrey J, Gomez G, June D, McDonald MA, Dannals RF, et

al: Tau pathology in cognitively normal older adults. Alzheimers

Dement (Amst). 11:637–645. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Chow VW, Mattson MP, Wong PC and

Gleichmann M: An overview of APP processing enzymes and products.

Neuromolecular Med. 12:1–12. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Lanoiselée HM, Nicolas G, Wallon D,

Rovelet-Lecrux A, Lacour M, Rousseau S, Richard AC, Pasquier F,

Rollin-Sillaire A, Martinaud O, et al: APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2

mutations in early-onset Alzheimer disease: A genetic screening

study of familial and sporadic cases. PLoS Med.

14(e1002270)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Tapia-Arancibia L, Aliaga E, Silhol M and

Arancibia S: New insights into brain BDNF function in normal aging

and Alzheimer disease. Brain Res Rev. 59:201–220. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Croll SD, Ip NY, Lindsay RM and Wiegand

SJ: Expression of BDNF and trkB as a function of age and cognitive

performance. Brain Res. 812:200–208. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Erickson KI, Miller DL and Roecklein KA:

The aging hippocampus: Interactions between exercise, depression,

and BDNF. Neuroscientist. 18:82–97. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Morrison JH and Baxter MG: The ageing

cortical synapse: hallmarks and implications for cognitive decline.

Nat Rev Neurosci. 13:240–250. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Ray B, Chauhan NB and Lahiri DK: Oxidative