Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is a highly prevalent malignant

tumor worldwide. According to GLOBOCAN 2022 data released by the

International Agency for Research on Cancer, the incidence and

mortality rates of GC rank fifth among all malignant neoplasms

globally, with an estimated 970,000 new cases and 660,000 deaths

annually (1). Because most patients

are diagnosed at advanced or metastatic stages, thereby forfeiting

the opportunity for curative surgical intervention, there is an

urgent need to develop more effective and less toxic

chemotherapeutic agents for GC management (2,3).

Cisplatin, a first-line chemotherapeutic agent,

plays a crucial role in treating GC by inducing DNA cross-linking

damage and generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) (4,5).

However, its clinical application is often associated with

pronounced nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity, which substantially

constrain its prolonged use and optimal dosing (6-8).

In recent years, the combination of small-molecule compounds with

cisplatin has attracted considerable attention because of their

synergistic and toxicity-reducing properties. This approach can

lower the required dose of cisplatin while enhancing tumor cell

sensitivity to chemotherapy (9-11).

Therefore, identifying small-molecule compounds capable of

eliciting synergistic effects at low concentrations represents a

promising approach to enhancing cisplatin-based therapeutic

regimens in patients with GC. Hesperadin is a small-molecule kinase

inhibitor identified through high-throughput screening (12-14).

It has been demonstrated that Hesperadin possesses dual functions:

Antitumor and cardioprotective properties. First, by targeting and

inhibiting Aurora B kinase, which regulates mitosis and mediates

antitumor activity, as well as calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein

kinase II-δ (CaMKII-δ), which is involved in the oxidative stress

response, Hesperadin has exhibited significant antiproliferative

and proapoptotic effects in various tumor models. Second, the

inhibition of CaMKII-δ can mitigate the damage caused by

chemotherapeutic drugs to cardiac tissues (15). These properties, along with their

ability to reduce toxicity, offer unique advantages for clinical

application. Hesperadin exerts its antitumor activity through dual

inhibition of Aurora B and CaMKII-δ kinases, and its remarkable

potency is reflected in its exceptionally low

IC50values. Consistent with a previous study in

pancreatic cancer (16), the

present findings demonstrated that Hesperadin exhibits potent

antitumor effects at nanomolar concentrations in GC cells.

The dual functional properties of Hesperadin offer a

novel therapeutic avenue for combination chemotherapy. By targeting

and modulating downstream molecular activities, Hesperadin

increases tumor cell sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents while

simultaneously mitigating treatment-associated toxicity. However,

its specific role in GC and its potential synergistic interactions

with cisplatin remain incompletely understood. In the present

study, it was demonstrated that hesperadin induces NOX1-dependent

ROS generation, thereby increasing the sensitivity of GC cells to

cisplatin. These findings not only establish a connection between

Hesperadin and the efficacy of cisplatin but also suggest new

possibilities for combination chemotherapy regimens in the

treatment of advanced GC.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human GC cell lines AGS and HGC-27 were procured

from the Cell Resource Center of the Chinese Academy of Medical

Sciences in collaboration with Peking Union Medical College. The

cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10%

heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Wisent, Inc.). The cells

were maintained at 37˚C in a humidified incubator with 5%

CO2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Drugs and reagents

Hesperadin (cat. no. HY-12054; MedChemExpress) and

cisplatin (cat. no. 232120; MilliporeSigma) were dissolved in

dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and normal saline, respectively, and

stored at -20˚C in light-protected conditions. The NOX1 inhibitor

ML171 (2-acetylphenothiazine; cat. no. HY-12805; MedChemExpress)

was also dissolved in DMSO before use. The Cell Counting Kit-8

(CCK-8; cat. no. C0038), Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit

(cat. no. C1062M), ROS detection kit (cat. no. S0033S), JC-1

mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP; cat. no. C2006) assay kit

and DNA damage detection kit (cat. no. C2035S) were obtained from

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology.

Cell proliferation and cytotoxicity

assays

To evaluate cytotoxicity, AGS and HGC-27 GC cells

were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 6,000 cells per well

and exposed to Hesperadin (0-90 nM) or cisplatin (0-120 µM) for 24

h. After 48 h of treatment, CCK-8 reagent (10 µl per well) was

added and incubated at 37˚C for 2 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was

then measured using a SpectraMax iD5 microplate reader (Molecular

Devices, LLC) to determine the half-maximal inhibitory

concentration (IC50) values using statistical

software.

For the proliferation inhibition assay, cells were

seeded at the same density and treated with Hesperadin alone or in

combination with cisplatin for 48 h. The procedures for CCK-8

reagent incubation and absorbance measurement at 450 nm were

performed as described for the cytotoxicity assay.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and

bioinformatics

RNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing

were performed by Shanghai Applied Protein Technology Co., Ltd.

Briefly, total RNA was extracted from AGS cells using

TRIzol® Reagent (cat. no. R0016; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). RNA integrity was verified (RIN >8.0).

Sequencing libraries were constructed using the VAHTS Universal V6

RNA-seq Library Prep Kit for Illumina (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.)

and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform to generate 150

bp paired-end reads. Subsequent bioinformatic analysis was

conducted as follows: Raw reads were quality-filtered using Fastp.

De novo assembly was performed with Trinity. Transcripts

were annotated against NR (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/about/nonredundantproteins/),

SwissProt (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb?facets=reviewed%3Atrue),

Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/), Gene Ontology

(GO; http://geneontology.org/) and Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) databases. Coding

sequences were predicted using TransDecoder. Gene expression (FPKM)

was quantified, and differential expression analysis was performed

using DESeq2 (threshold: |log2FC|>1, padj <0.05). GO and KEGG

enrichment analyses were conducted using clusterProfiler (version

4.16.0; Bioconductor).

Identification of differentially

expressed genes (DEGs) and functional enrichment analysis

With |log2-fold change (FC)|>1 and P<0.05 as

screening criteria, DEGs from bulk sequencing were identified via

the ‘Limma’ package (version 3.64.3; Bioconductor) of R. DEGs were

illustrated via volcano maps and heatmaps, which were plotted via

the ‘ggplot2’ and ‘Pheatmap’ packages of R, respectively. In

addition, KEGG and GO analyses were performed via the

‘clusterProfiler’ R package, which aims to assess gene-related

biological processes (BP), molecular functions, cellular

components, and gene-related signaling pathways (KEGG). The

conditions for screening significantly enriched GO terms and KEGG

pathways were Min overlap=three and Min enrichment=1.5. The

enrichment significance threshold was set to an adjusted P-value

below 0.05. In addition, gene set variation analysis (GSVA) is a

non-parametric and unsupervised method for estimating changes in

specific gene sets. The activities of the hallmark pathways were

quantified with the GSVA R package according to the ‘Hallmarks

geneset’ downloaded from the MsigDB database. Finally, gene set

enrichment analysis (GSEA) was employed to identify DEG functions

on the basis of P<0.05 and a false discovery rate (FDR) value of

0.25.

Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis

and necrosis

Apoptosis was assessed using an Annexin

V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) apoptosis detection kit (cat. no.

C1062M; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Briefly, after drug

treatment, the cells were collected, washed twice with ice-cold

PBS, and resuspended in 1X binding buffer at a density of

1x106 cells/ml. Subsequently, cells were stained with

Annexin V-FITC and PI for 15 min at room temperature in the dark

according to the manufacturer's instructions. To establish

appropriate gating and compensation, unstained cells and

single-stained controls (cells stained with Annexin V-FITC only or

PI only) were included in each experiment. Flow cytometric analysis

was immediately performed on a Beckman CytoFLEX flow cytometer

(Beckman Coulter, Inc.). The data were analyzed using FlowJo

software (version 10.8.1; FlowJo LLC). The percentages of cells in

early apoptosis (Annexin V+/PI-) and late

apoptosis/necrosis (Annexin V+/PI+) were

quantified.

Detection of intracellular ROS

levels

For ROS detection, following the respective

treatments, cells were collected, washed twice with pre-warmed

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then incubated with 10 µM

CM-H2DCFDA diluted in serum-free medium at 37˚C in the dark for 25

min. After incubation, the cells were washed to remove the excess

probe and analyzed using a fluorescence microscope (MShot MF53-N,

FITC channel), and the captured images were quantified using ImageJ

software (version 1.53k; National Institutes of Health). The

fluorescence intensity was quantified via flow cytometry (FITC

channel).

MMP assay

The MMP was assessed via a JC-1 assay kit (cat. no.

C2006; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The cells were

incubated with JC-1 staining solution for 20 min at 37˚C in the

dark for 20 min. The fluorescence intensity ratios (red/green) were

subsequently analyzed via fluorescence microscopy (MShot MF53-N).

JC-1 aggregates (red fluorescence) in healthy mitochondria with

high MMP and JC-1 monomers (green fluorescence) in depolarized

mitochondria with low MMP were detected using the TRITC and FITC

channels, respectively. For quantitative analysis, the fluorescence

intensity of the red and green channels from the captured images

was measured using ImageJ software (version 1.53k; National

Institutes of Health).

DNA damage assay

The cells were fixed for 15 min and subsequently

incubated overnight at 4˚C with the γ-H2AX primary antibody (cat.

no. C2035S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). After three

gentle rinses with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the cells were

incubated for 1 h with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Nuclei were counterstained with

DAPI (10 µg/ml) for 5 min. Fluorescence images were captured via a

fluorescence microscope (MShot MF53-N). The number of γ-H2AX foci

per cell was quantified via the ‘Analyze Particles’ function in

ImageJ software (version 1.53k).

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cultured AGS and HGC-27

cells using an RNA extraction kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Inc.). cDNA was

synthesized from 1 µg RNA using the SweScript RT SuperMix (Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). with the following thermal

protocol: 25˚C for 5 min, 42˚C for 15-30 min, and 85˚C for 5 sec.

qPCR was performed on a QuantStudio 5 system (Applied Biosystems;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) using Servicebio SYBR Green Master

Mix. The thermocycling protocol was as follows: 95˚C for 10 min; 40

cycles of 95˚C for 15 sec and 60˚C for 1 min. The relative

expression of NOX1 was normalized to GAPDH and calculated using the

2-ΔΔCq method (17). The

sequences of primers used were as follows: NOX1 forward,

5'-TCTGGTTGTTTGGTTAGGGCT-3' and reverse, 5'-CGGCTGCAAAACCCAAGGA-3';

and GAPDH forward, 5'-CGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGTAT-3' and reverse,

5'-AGCCTTCTCCATGGTGGTGAAGAC-3'.

Colony formation assay

The GC cell lines were seeded into culture plates.

After adhering, the cells were treated with the designated

concentrations for 10 days, followed by staining with 0.1% crystal

violet for 30 min. The plates were rinsed with ultrapure water,

air-dried, and scanned. Colonies containing more than 50 cells were

automatically quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.53k;

National Institutes of Health).

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (cat. no. P0013B;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) supplemented with 1% PMSF. The

protein concentration was determined using a BCA Protein Assay Kit

(cat. no. P0010; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). In total,

~20-30 µg of total protein per lane was separated on 12.5% SDS-PAGE

gels (Epizyme, Inc.) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride

(PVDF) membranes (MilliporeSigma). The membranes were blocked with

5% non-fat milk in TBST (0.1% Tween-20) for 2 h at room temperature

and then incubated overnight at 4˚C with the following primary

antibodies: anti-BCL-2 (1:2,000; cat. no. 12789-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), anti-BAX (1:20,000; cat. no. 50599-2-Ig; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), anti-caspase-3/cleaved caspase-3 (1:1,000; cat. no.

19677-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-NOX1 (1:1,000; cat. no.

671300; Chengdu Zhengneng Biotechnology, Co., Ltd.), anti-β-ACTIN

(1:50,000; cat. no. 66009-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and

anti-GAPDH (1:20,000; cat. no. 10494-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.). After washing, the membranes were incubated with

HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-2;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) or HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG

(1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-1; Proteintech Group, Inc.) secondary

antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were

visualized using an Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) Substrate

(cat. no. WBKLS0500; MilliporeSigma) and captured digitally. The

band intensities were quantified by densitometry using ImageJ

software (version 1.53k; National Institutes of Health).

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

transfection

For siRNA transfection, cells were cultured in

6-well plates until they reached ~70-90% confluence. Specific

siRNAs were then transfected via Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (cat.

no. 11668-027; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A final

concentration of 20 µM of siRNA was used for each transfection. The

transfection was carried out in serum-free Opti-MEM medium and

incubated with the cells at 37˚C for 4 h, after which the medium

was replaced with complete growth medium. The efficiency of

siRNA-mediated interference was verified 48 h post-transfection via

western blotting to ensure effective knockdown of the target genes.

All siRNAs, including the non-targeting negative control (si-NC),

were designed and synthesized by Anhui General Biotech Co., Ltd.

The siRNA sequences utilized in the present study were as follows:

siNOX1#1 (homo-ID27035 siRNA-318) forward,

5'-AUGAGAAGGCCGACAAAUATT-3' and reverse,

5'-AUUUGCGCAGGCUCUUUGCTT-3'; siNOX1#2 (homo-ID27035 siRNA-1315)

forward, 5'-CAUAAGGGCUUUCGAACAATT-3' and reverse,

5'-UUGUUCGAAAGCCCUUAUGTT-3'; and si-NC forward,

5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3' and reverse,

5'-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3'.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± SDs of three

independent biological replicates. Statistical comparisons between

two groups were performed using an unpaired Student's t test. For

comparisons among more than two groups, one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA) was employed, followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. All statistical analyses were performed via GraphPad

Prism software (version 9.5.1; Dotmatics).

Results

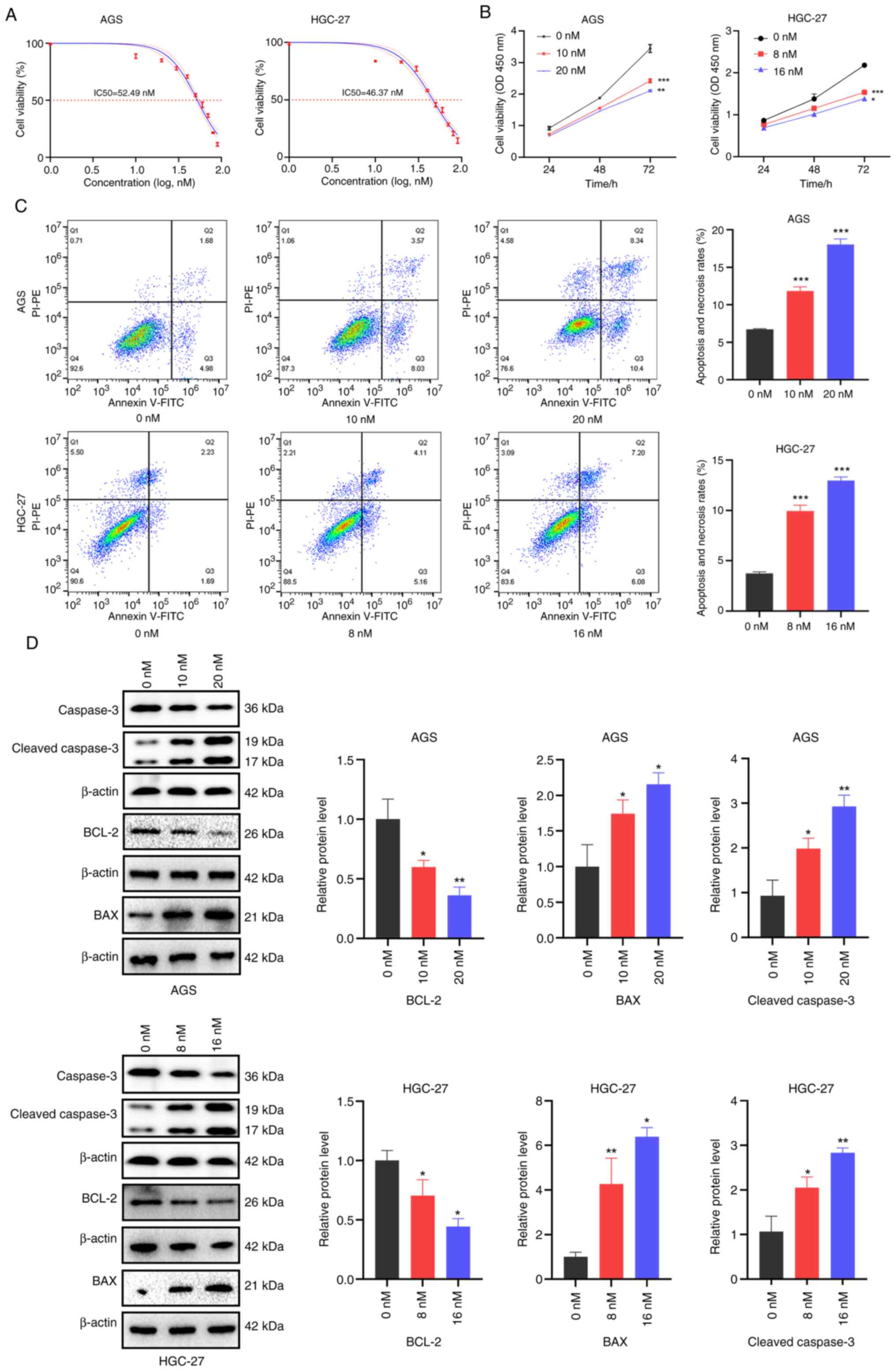

Hesperadin induces cell death and

inhibits proliferation in GC cells

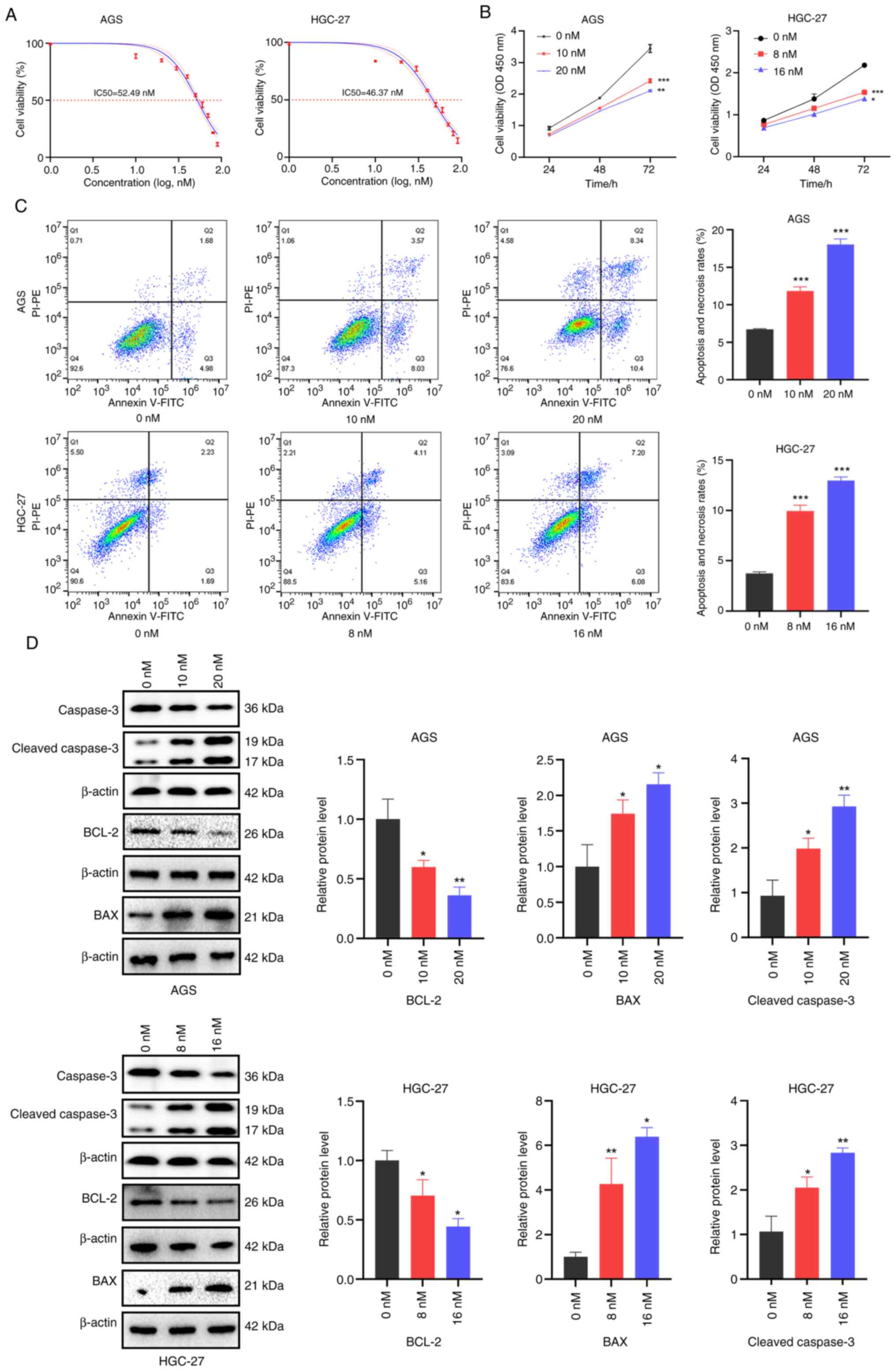

To assess the antitumor activity of Hesperadin, its

IC50 in GC cell lines was first determined. The IC50 values of

Hesperadin in AGS and HGC-27 cells were 52.49 nM and 46.37 nM,

respectively (Fig. 1A). Next,

concentrations of 10 and 20 nM were selected for AGS cells and 8

and 16 nM for HGC-27 cells, all of which are below the IC50 values

for subsequent experiments. Compared with the control, Hesperadin

significantly inhibited the proliferation of GC cells in a

concentration-dependent manner (Fig.

1B).

| Figure 1Hesperadin inhibits proliferation and

induces death in gastric cancer cells. (A) After the cells were

treated with graded concentrations of hesperadin (0, 10, 20, 30,

40, 50, 60, 70, 80 and 90 nM) for 48 h, cell viability was assessed

via the CCK-8 assay, and the IC50 was calculated. (B) A

CCK-8 assay was used to evaluate the viability of AGS and HGC-27

cells following 24, 48 and 72 h of Hesperadin treatment. (C) Flow

cytometric analysis was conducted to assess cell mortality after 48

h of Hesperadin treatment. (D) The expression levels of the

apoptosis-related proteins BCL-2, BAX and cleaved caspase-3 were

analyzed via western blotting. β-ACTIN was used as a loading

control. Compared with the control group, the high-concentration

group was compared with the low-concentration group;

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit. |

To further examine the growth-inhibitory effects of

Hesperadin on GC cells, Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining followed

by flow cytometry was performed to evaluate its effect on cell

death. Flow cytometry revealed increased cell death after 48 h of

treatment (Fig. 1C). Western blot

analysis demonstrated that hesperadin significantly downregulated

the expression of the antiapoptotic protein BCL-2 while

upregulating the expression of the proapoptotic proteins BAX and

cleaved caspase-3. These findings indicated that Hesperadin

promotes cell death through activation of the mitochondrial

apoptosis pathway (Fig. 1D). Taken

together, these results demonstrated that Hesperadin suppresses GC

cell proliferation and induces cell death in a dose-dependent

manner via activating the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway.

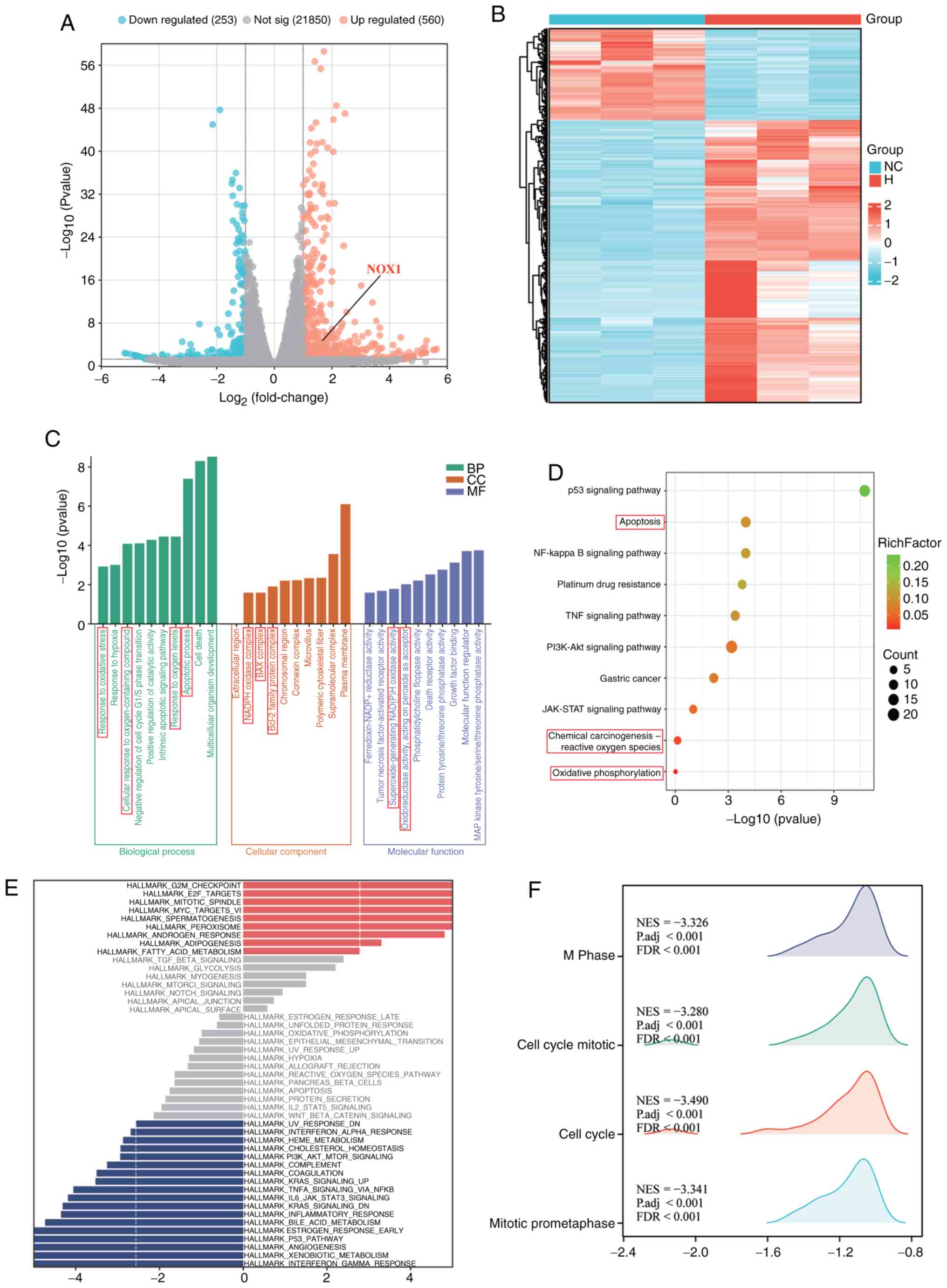

Transcriptomic analysis suggests that

Hesperadin may induce GC cell death through the apoptosis and

oxidative stress pathways

Inducing the apoptosis of tumor cells is one of the

important ways to inhibit cell proliferation (18). To elucidate the molecular mechanisms

driving Hesperadin-induced cell death in GC, RNA-seq was conducted

on AGS cells treated with 10 nM Hesperadin for 48 h. A complete

list of all DEGs is provided in Table

SII. The DEGs identified from the RNA-seq results are

illustrated in Fig. 2A and B. GO, KEGG, GSEA and GSVA enrichment

analyses revealed that the DEGs were significantly enriched in BP

such as apoptosis and the oxidative stress response (Fig. 2C-F). While the top 10 upregulated

DEGs were associated with key cancer pathways such as cell cycle

arrest (for example, CDKN1A), p53 signaling (for example, BTG2) and

cell adhesion (for example, PTPRU) (Table SI), the pronounced enrichment in

oxidative stress pathways particularly captured our attention.

Specifically, GO analysis identified significant enrichment in the

‘cellular response to oxidative stress’ (GO: 0045489) (Fig. 2C) and KEGG analysis confirmed

enrichment in the ‘Oxidative phosphorylation’ pathway (hsa00190)

(Fig. 2D). This transcriptional

profile aligns with the documented mechanism of Hesperadin, which

induces mitochondrial dysfunction and a ROS surge in other cancer

models (16). Consequently, DEGs

within these oxidative stress-related pathways were prioritized for

further investigation. Among them, NADPH Oxidase 1 (NOX1) emerged

as a compelling candidate. Although its fold-change ranked outside

the top 10, NOX1 encodes a critical catalytic subunit of the NADPH

oxidase complex, a dedicated superoxide generator and a master

regulator of oxidative stress (19,20).

Its significant upregulation (log2FC >1.5, P<0.01)

following Hesperadin treatment (Fig.

2A) suggested a functionally central role in mediating the

observed oxidative stress phenotype. NOX1 was therefore selected

for subsequent functional validation.

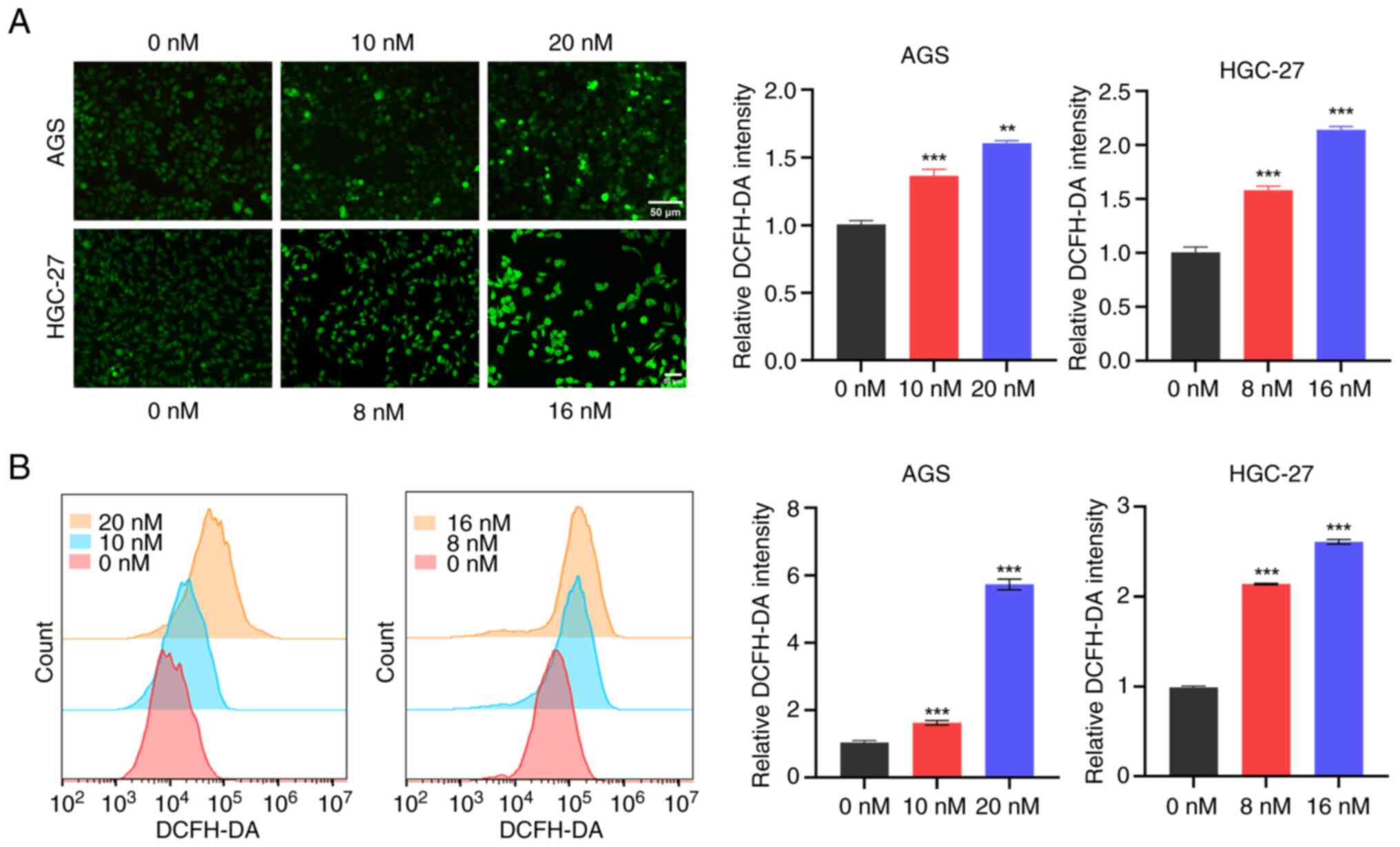

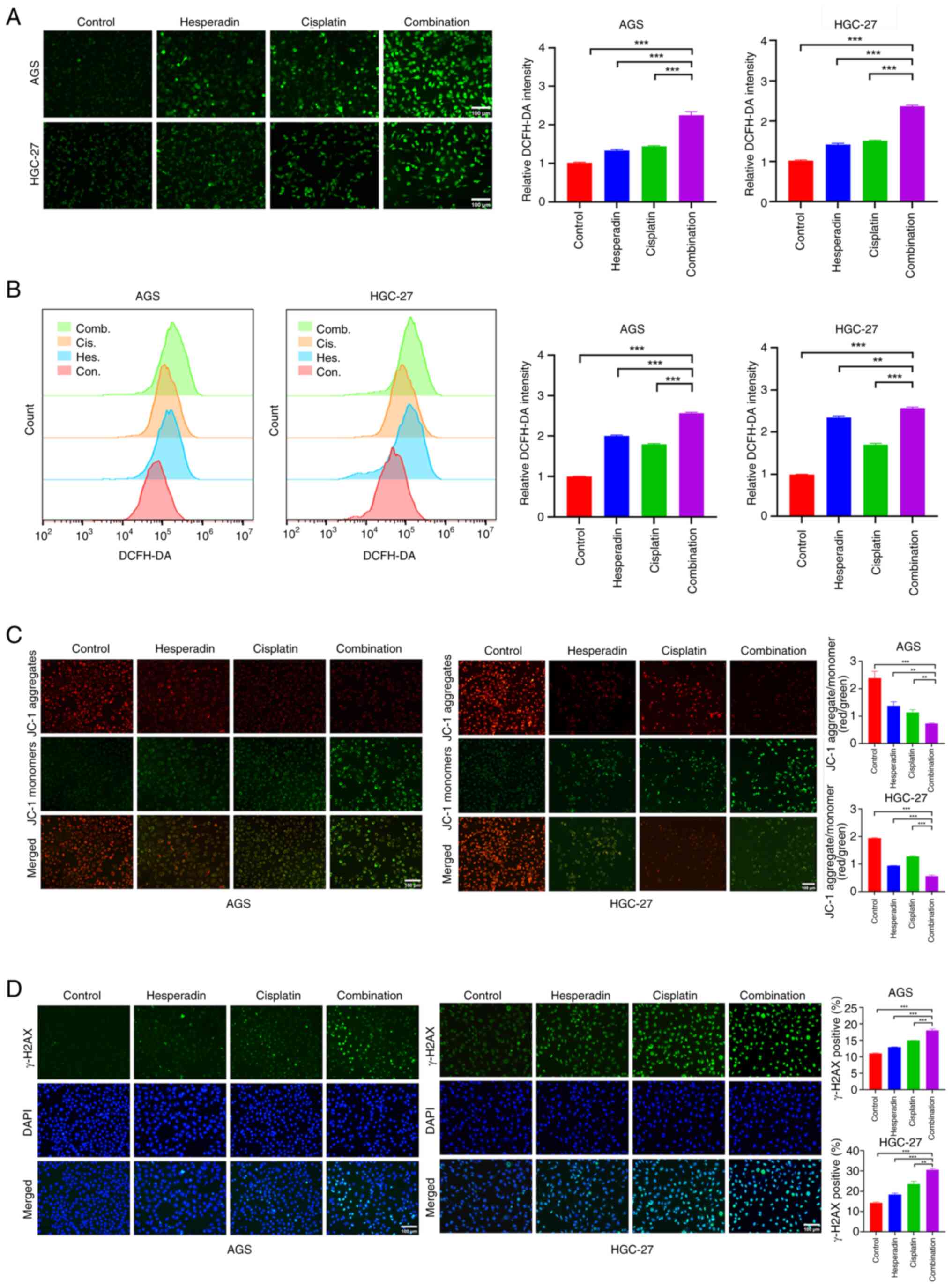

Hesperadin promotes GC cell death by

activating the oxidative stress pathway through the induction of

ROS generation

Excessive production of ROS induces oxidative stress

and mitochondrial dysfunction, ultimately leading to cell death

(18,19). To investigate the impact of

Hesperadin on ROS generation and oxidative stress pathways in GC

cells, intracellular ROS levels in AGS and HGC-27 cells were

measured following Hesperadin treatment. The results showed a

significant, concentration-dependent increase in ROS fluorescence

intensity in the Hesperadin-treated cells compared with the control

group (Fig. 3A). Further

quantitative analysis by flow cytometry revealed that Hesperadin

increased ROS levels in GC cells in a dose-dependent manner

(Fig. 3B). In summary, it can be

concluded that Hesperadin induces cell death in GCs by increasing

the generation of ROS, which leads to oxidative stress and

activates the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway.

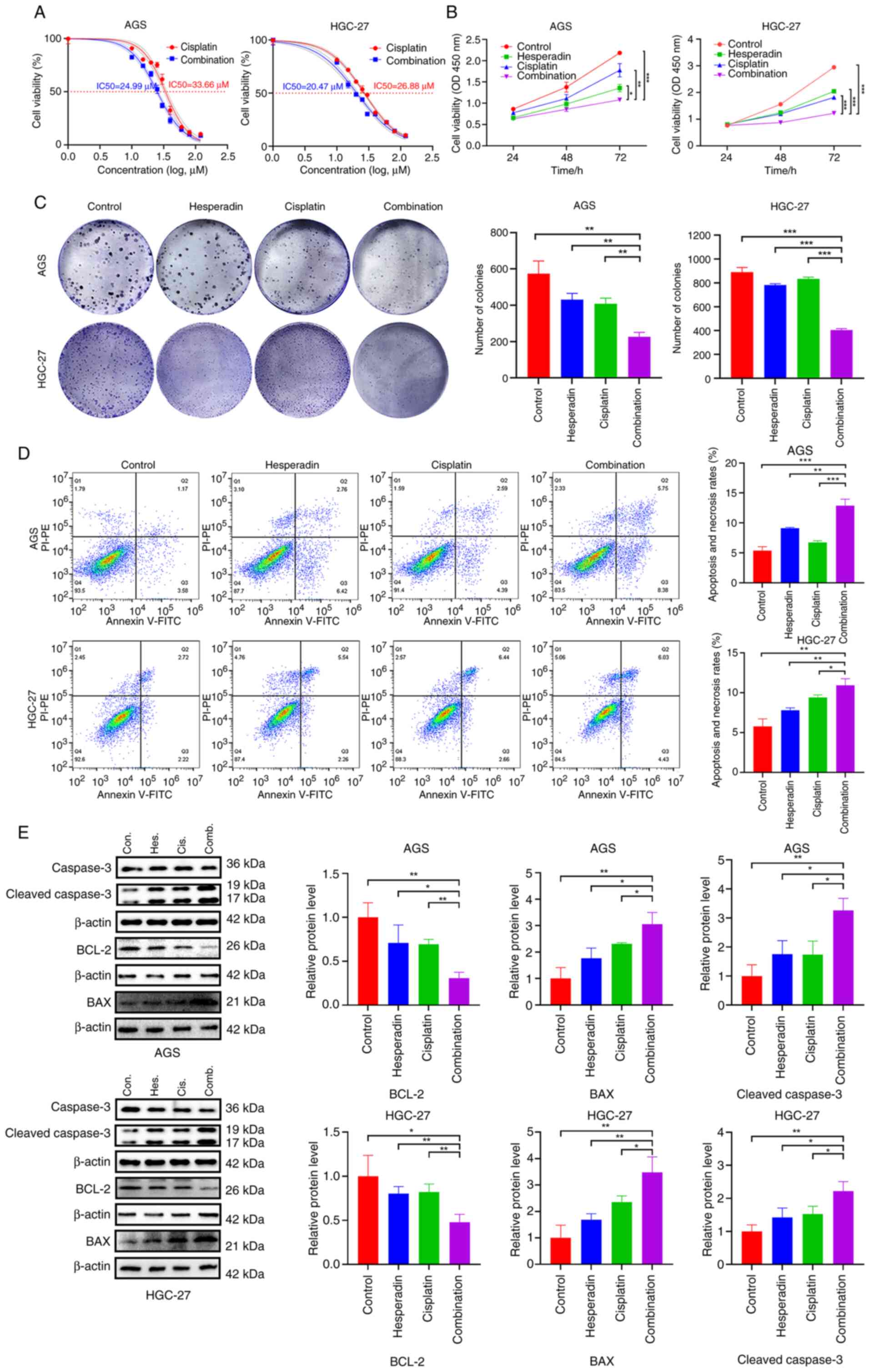

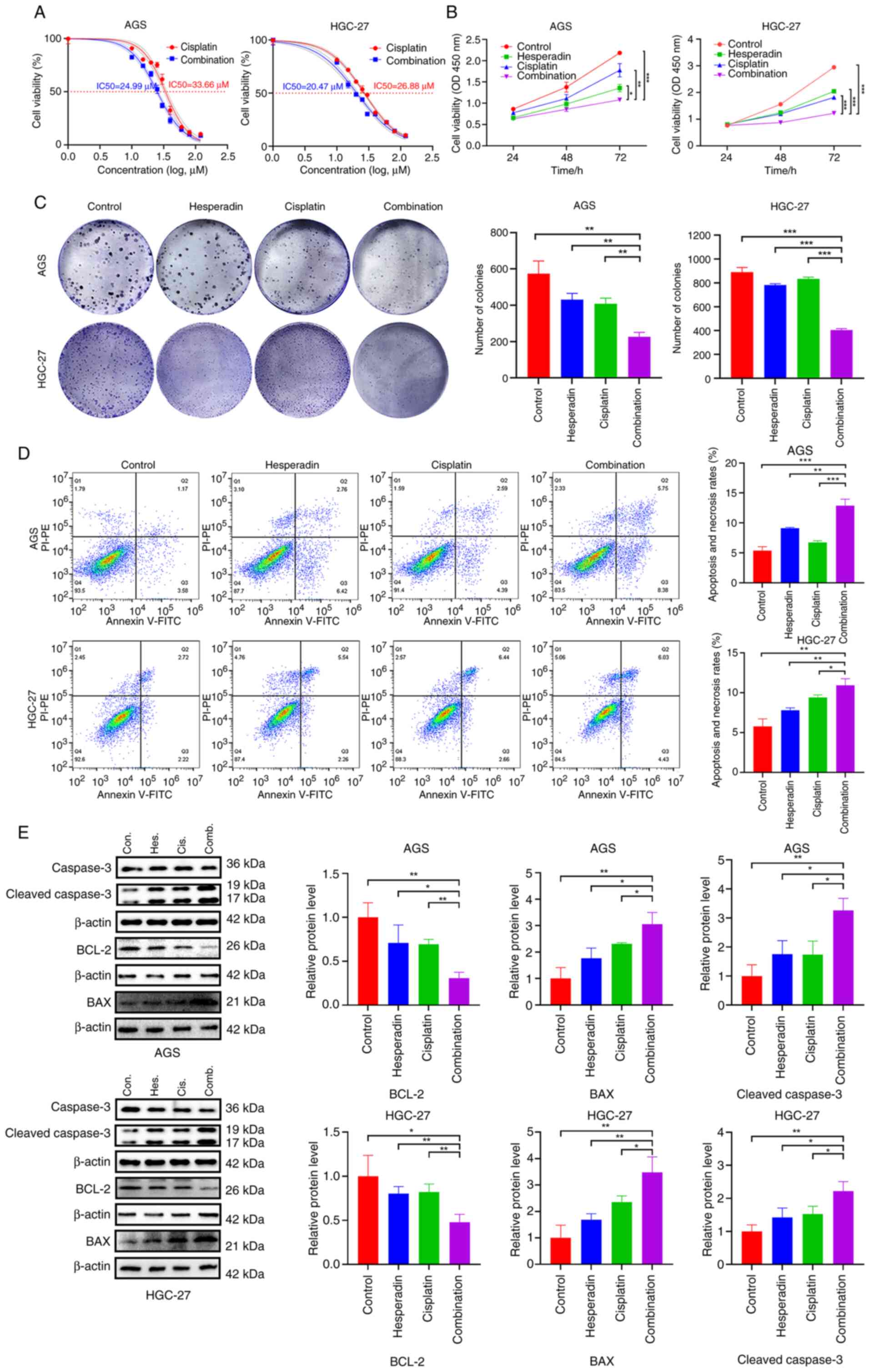

Hesperadin increases the sensitivity

of GC cells to cisplatin

Cisplatin is a key chemotherapeutic agent widely

used in the treatment of GC (21,22).

Considering the mechanistic similarities between cisplatin and

Hesperadin in modulating tumor-associated pathways, the present

study aimed to evaluate the potential therapeutic benefits of

combining both agents in GC cell models. To investigate the

potential combinatorial effect of Hesperadin and cisplatin, the

IC50 for each agent alone was first determined in AGS

and HGC-27 cells (Figs. 1A and

4A). To distinguish true synergy

from additive toxicity, sub-IC50 concentrations were

selected for all combination treatments. Based on dose-response

profiles and preliminary validation, the chosen concentrations (20

nM Hesperadin and 10 µM cisplatin for AGS cells, and 16 nM

Hesperadin and 8 µM cisplatin for HGC-27 cells) represent ~30-40%

of their respective single-agent IC50 values. These

doses induce partial biological effects (Fig. 1B and C) and moderate proliferation inhibition

without causing overwhelming cell death, thereby providing a clear

window to observe enhanced efficacy upon combination. Under these

conditions, the combinatorial effects were evaluated. The results

revealed that when AGS and HGC-27 cells were treated with a

combination of Hesperadin and cisplatin, the IC50 values

for cisplatin decreased from 33.66 and 26.88 µM to 24.99 and 20.47

µM, respectively (Fig. 4A).

Furthermore, the GC cell survival rate in the Hesperadin-cisplatin

combination treatment group was significantly lower than that in

the control and single-drug groups (Fig. 4B), whereas the clonogenic ability

was significantly reduced (Fig.

4C), and the mortality rate was significantly elevated

(Fig. 4D). Additionally, western

blot analysis revealed that the expression levels of the

proapoptotic proteins BAX and cleaved caspase-3 were increased,

whereas the expression of the antiapoptotic protein BCL-2 was

decreased in the combination treatment group (Fig. 4E). These results indicated that

Hesperadin enhances the antiproliferative effect of cisplatin,

promotes apoptosis, and thereby potentiates the cytotoxic effect of

cisplatin on GC cells.

| Figure 4Hesperadin enhances the sensitivity

of gastric cancer cells to cisplatin. (A) Changes in the

IC50 of cisplatin in AGS and HGC-27 cells after 48 h of

cotreatment with Hesperadin (10 nM) and various concentrations of

cisplatin (0, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 60, 80, or 120 nM). (B) Cell

Counting Kit-8 assay for cell viability after 24, 48 and 72 h of

cotreatment with Hesperadin and cisplatin. (C) Colony formation

assay to assess the ability of cells to form colonies after 10 days

of cotreatment. (D) Flow cytometric analysis showing cell mortality

after cotreatment with Hesperadin and cisplatin. (E) Western blot

analysis was used to evaluate the expression of apoptosis-related

proteins (BCL-2, BAX and cleaved caspase-3). β-ACTIN was used as a

loading control. Hesperadin concentrations were 20 nM for AGS cells

and 16 nM for HGC-27 cells, whereas cisplatin concentrations were

10 µM for AGS cells and 8 µM for HGC-27 cells. Compared with all

the other groups (Control, Hes. alone, Cis. alone);

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. Con., Control; Hes., Hesperadin; Cis.,

Cisplatin; Comb., Combination. |

Hesperadin enhances the sensitivity of

GC cells to cisplatin via oxidative stress

Cisplatin exerts its anticancer effect mainly by

binding to DNA to form cross-links and induce the production of

ROS, thereby leading to apoptosis (4,5). The

present study revealed that Hesperadin significantly inhibits GC

cell proliferation and induces cell death by inducing ROS

generation (Figs. 1C and 3). Therefore, it was next explored whether

Hesperadin could increase the sensitivity of GC cells to cisplatin

through oxidative stress. First, the fluorescence intensity in the

Hesperadin-cisplatin combination treatment group was significantly

greater than that in the single-drug treatment groups (Fig. 5A); the same results were obtained

through quantitative flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, it was found that

both Hesperadin alone and cisplatin significantly reduced the MMP,

whereas the combined treatment caused a further significant

reduction in the MMP (Fig. 5C).

Additionally, the fluorescence intensity of the DNA damage marker

γ-H2AX was measured. The results revealed that γ-H2AX fluorescence

intensity in the single-drug treatment groups (Hesperadin or

cisplatin) was significantly higher than in the control group,

whereas the combination treatment group demonstrated a further

significant increase in γ-H2AX fluorescence intensity (Fig. 5D), indicating more extensive DNA

damage following combination treatment. Collectively, these

findings indicated that Hesperadin enhances the sensitivity of GC

cells to cisplatin by promoting ROS generation, disrupting MMP,

exacerbating DNA damage, and thereby facilitating cell death.

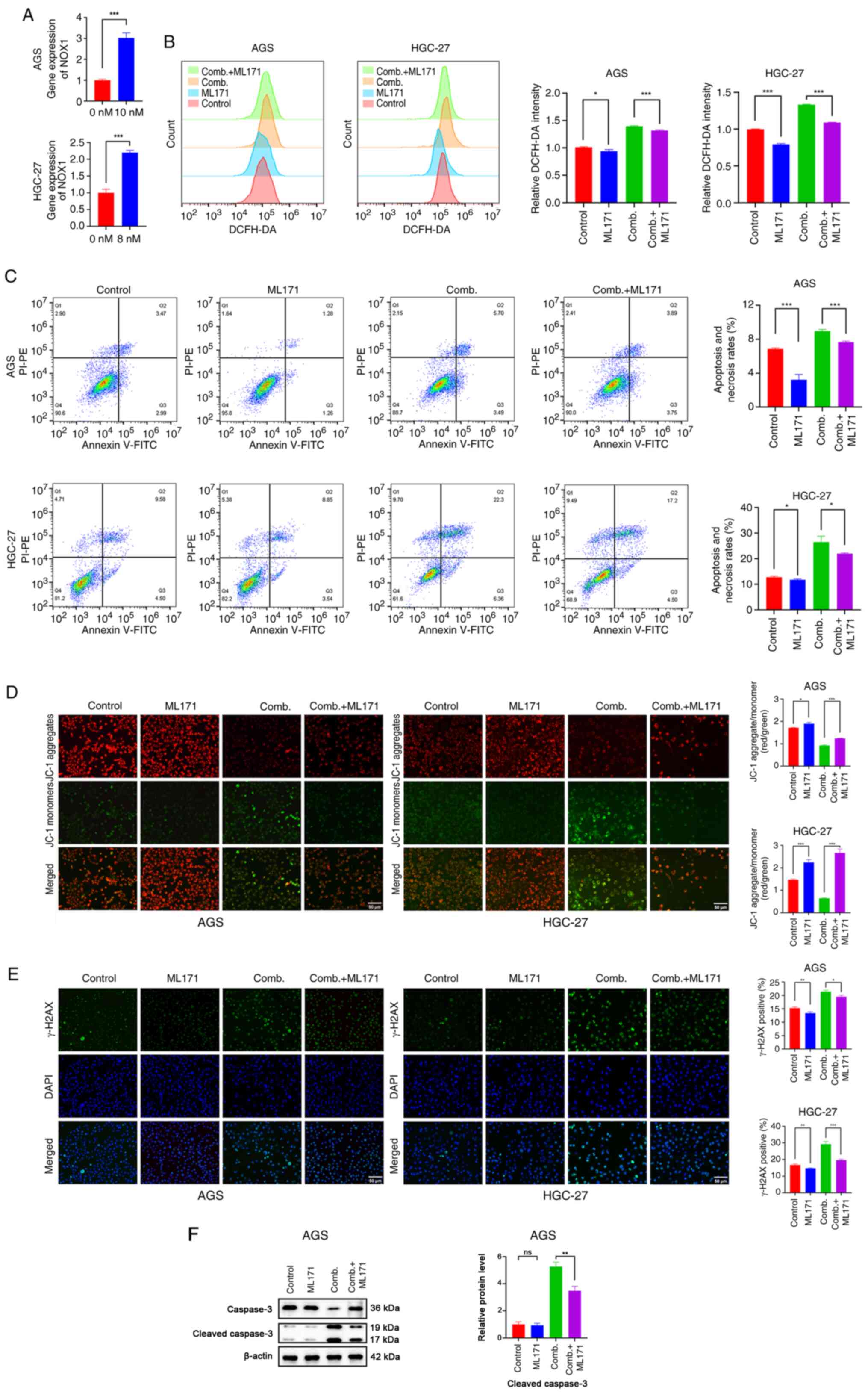

Hesperadin enhances the sensitivity of

GC cells to cisplatin by activating NOX1-induced oxidative

stress

To directly investigate whether the

chemo-sensitizing effect of Hesperadin toward cisplatin was

mediated through the NOX1/ROS axis, as suggested by our

transcriptomic data, the upregulation of NOX1 expression was first

confirmed. Through RT-qPCR analysis, it was found that NOX1

expression was significantly upregulated upon Hesperadin treatment

in GC (Fig. 6A). In addition,

western blot analysis confirmed that the Hesperadin alone,

cisplatin alone, and combination treatments significantly increased

the protein expression level of NOX1 in AGS cells. In HGC-27 cells,

the increase in NOX1 protein following cisplatin treatment did not

reach statistical significance, highlighting a cell-type-dependent

difference in response. However, the combination treatment with

Hesperadin robustly increased NOX1 levels in both cell lines

(Fig. S1C), which was consistent

with the observed transcriptional changes. To validate the

functional role of NOX1, siRNA was subsequently used to knock down

NOX1 expression in AGS and HGC-27 cells. Compared with si-NC

transfection, NOX1-specific siRNA transfection significantly

reduced NOX1 protein levels (Fig.

S1A). ML171, a highly selective NOX1 inhibitor, was

subsequently employed to evaluate the role of NOX1 in

Hesperadin-induced oxidative stress and its impact on cisplatin

sensitivity in GC cells. The results revealed that both ML171

treatment and NOX1 knockdown markedly attenuated the generation of

ROS induced by the combination of cisplatin and Hesperadin

(Figs. 6B and S1B). Furthermore, NOX1 inhibition rescued

the cell death caused by the combined treatment (Fig. 6C). MMP analysis revealed that NOX1

inhibition partially reversed the MMP reduction induced by the

combination treatment (Fig. 6D).

Additionally, γ-H2AX immunofluorescence analysis revealed that NOX1

inhibition significantly attenuated DNA damage in the combination

treatment group (Fig. 6E). To

provide molecular substantiation for the flow cytometry results in

AGS cells, western blot analysis for Cleaved Caspase-3 was

performed using the same treatments. Consistent with the functional

data, the combination treatment significantly increased the level

of Cleaved Caspase-3, which was significantly reversed by

co-treatment with the NOX1 inhibitor ML171 (Fig. 6F). Collectively, these findings

indicated that Hesperadin promotes ROS generation through

NOX1-mediated oxidative stress in GC cells.

Discussion

Hesperadin was initially synthesized as a novel

indolinone compound during anti-proliferative screening and was

subsequently identified as a potent Aurora B kinase inhibitor that

disrupts mitosis by impairing chromosome segregation and spindle

assembly checkpoint function (23).

Its mechanisms of action not only include G2/M phase

cell cycle arrest through Aurora B inhibition but also involve the

induction of DNA damage, oxidative stress (ROS generation),

endoplasmic reticulum stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction,

ultimately promoting cancer apoptosis (16,24).

Additionally, Hesperadin has been identified as a selective

inhibitor of CaMKII-δ, suggesting potential cardioprotective

effects (15). It also acts as a

broad-spectrum anti-influenza agent effective against both

influenza A and B viruses, including oseltamivir-resistant strains

(25). However, its application and

mechanism in the treatment of GC have not yet been extensively

studied.

In the present study, it was confirmed that

Hesperadin significantly inhibits GC cell proliferation and induces

apoptosis while enhancing the chemosensitivity of GC cells to

cisplatin. To elucidate the underlying mechanism, transcriptomic

analysis and identified NOX1 was performed, a key member of the

NADPH oxidase family, as an upstream regulator of Hesperadin's

action. Combined treatment with Hesperadin and cisplatin

significantly upregulated NOX1 expression. Importantly, inhibition

of NOX1 substantially reversed the ROS generation and cytotoxic

effects induced by the combination treatment. These results

demonstrated that Hesperadin enhances cisplatin sensitivity in GC

cells primarily through NOX1-mediated ROS overproduction. Notably,

Hesperadin can modulate NOX1 expression, and cisplatin has also

been shown to do so in other models. Research by Kim et al

(26) in auditory cells showed that

cisplatin upregulates NOX1 expression by inducing the release of

pro-inflammatory cytokines (for example, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) and

activating the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. However, the specific

mechanism by which cisplatin regulates NOX1 in GC requires further

investigation. On the other hand, as a dual inhibitor of Aurora B

and CAMKII-δ, Hesperadin may influence ROS responses through

multiple pathways. Aurora B, a key mitotic regulator, is involved

in DNA damage response and cell survival under genotoxic stress.

Its inhibition may compromise DNA repair fidelity, thereby

amplifying cisplatin-induced DNA damage and ROS accumulation

(27,28). Meanwhile, CAMKII-δ is known to

participate in redox signaling and mitochondrial regulation in

various cell types (29,30). Although its role in GC remains

unclear, it was hypothesized that CAMKII-δ may similarly regulate

NOX1 activity or mitochondrial ROS generation in GC cells.

Elucidating the specific mechanisms and potential crosstalk between

Hesperadin and cisplatin in regulating NOX1 will be a focus of our

future research. However, the present study has certain

limitations. First, the present findings require further validation

in in vivo animal models to confirm the therapeutic efficacy

and safety profile of the Hesperadin and cisplatin combination.

Second, it is important to note that our mechanistic focus on NOX1

and oxidative stress was influenced by prior literature (31,32)

and the established role of ROS in Hesperadin's action in other

cancers (16). While the present

RNA-seq data supported this focus (Fig.

2C and D), this targeted

approach may have introduced a selection bias, potentially

overlooking other DEGs with higher fold changes or unknown

functions in GC (Table SI) that

could also contribute to the observed phenotype. Moreover, the

precise molecular mechanisms by which Hesperadin regulates NOX1

expression and mediates oxidative stress warrant deeper

investigation. Specifically, the upstream regulatory mechanisms

(for example, how Hesperadin activates NOX1

transcription/translation through specific signaling pathways) and

the downstream effector protein interaction network following

NOX1-mediated ROS generation remain insufficiently elucidated.

Research indicates that the regulation of NOX1 by cisplatin in

auditory cells is associated with inflammatory signaling, whereas

the mechanism by which Hesperadin modulates NOX1 in GC cells

remains unclear. Although the present RNA-seq analysis implicated

potential involvement of pathways such as p53, NF-κB and PI3K-Akt

(Fig. 2D), these preliminary

findings await future experimental validation to define their

precise roles in this regulatory axis.

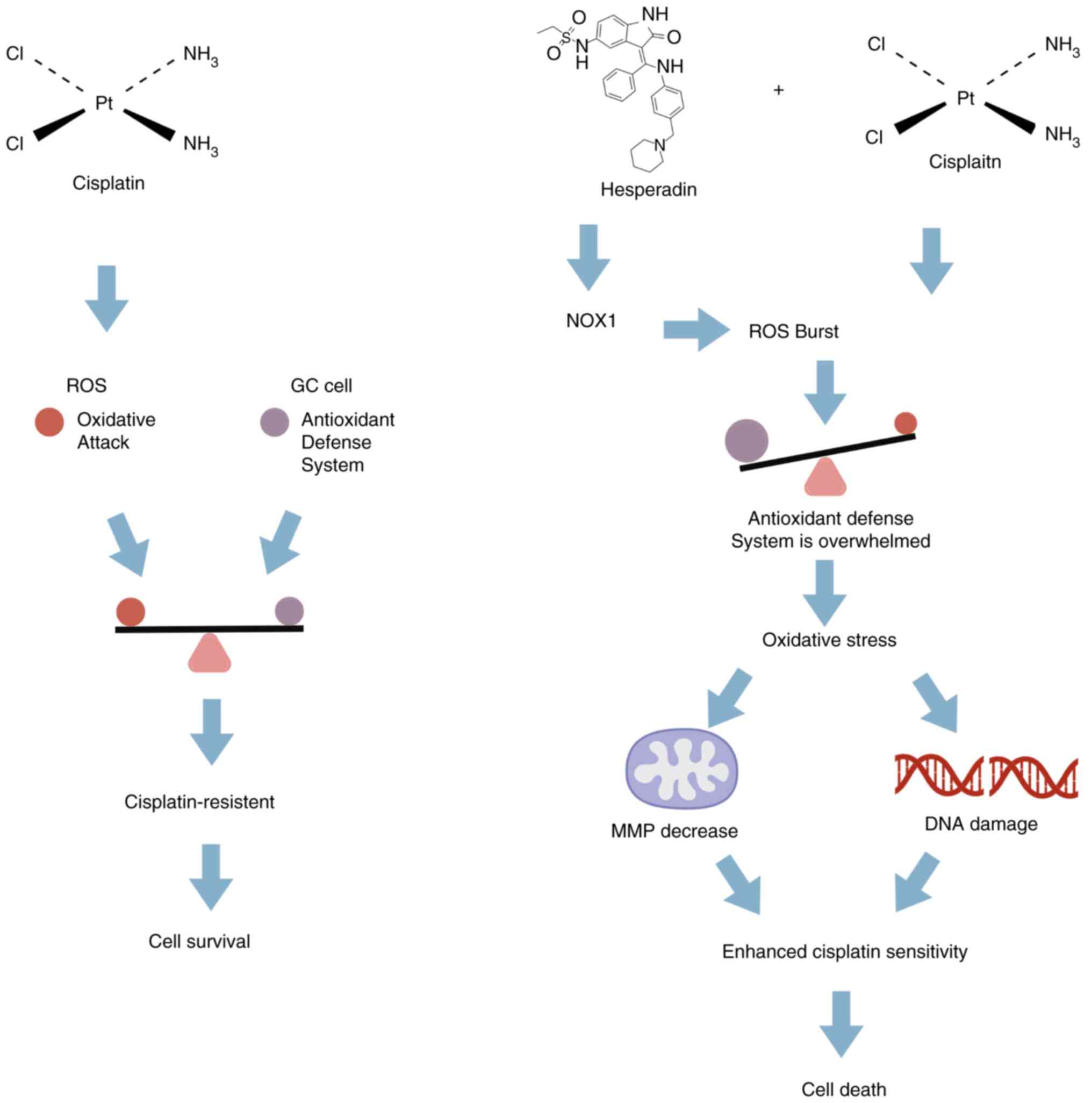

In summary, the present study demonstrated that

Hesperadin sensitizes GC cells to cisplatin by triggering

NOX1-mediated oxidative stress and mitochondrial

dysfunction-induced apoptosis (Fig.

7). Additionally, the current findings indicated that the

combination of Hesperadin and cisplatin represents a promising

therapeutic strategy for the treatment of GC.

Supplementary Material

Transcriptomic profiling and

validation of the NOX1-mediated mechanism. (A) Efficiency of NOX1

knockdown using two independent siRNAs. Western blot analysis

showing NOX1 protein expression in AGS and HGC-27 cells transfected

with si-NC or two different NOX1-specific siRNAs (si-NOX1#1 and

si-NOX1#2). GAPDH served as the loading control.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. the si-NC group. (B) Genetic

inhibition of NOX1 abrogates Hesperadin-induced ROS generation.

DCFH-DA fluorescence staining (green fluorescence represents ROS;

scale bar, 50 μm) and quantitative analysis showing ROS

levels in AGS and HGC-27 cells transfected with si-NC or si-NOX1

(#1 or #2) and treated with or without Hesperadin.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. the si-NC + Hesperadin group; ns: not

significant (P≥0.05) vs. the si-NC group. (C) Western blot analysis

of NOX1 protein expression in AGS and HGC-27 cells following

treatment with Hesperadin, cisplatin, or their combination for 48

h. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Data were compared among

all groups. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. siRNA, small interfering RNA; si-NC,

negative control siRNA; ROS, ROS, reactive oxygen species; ns, not

significant (P≥0.05).

Top 10 DEGs identified by

RNA-sequencing analysis.

DEGs in Hesperadin-treated AGS

cells.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Natural Science

Foundation of Bengbu Medical College (grant no. 2022byfy002), the

Graduate Research Innovation Program of Bengbu Medical College

(grant no. Byycx24005), the University Synergy Innovation Program

of Anhui (grant no. GXXT-2022-065) and the Natural Science Program

of Bengbu Medical University (grant no. 2023byzd030).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession numbers

SRR35296175, SRR35296174, SRR35296173, SRR35296169, SRR35296168 and

SRR35296167 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR35296175;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR35296174;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR35296173;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR35296169;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR35296168;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=SRR35296167.

The data generated in the present study may be requested from the

corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WJZ, HZW and YLZ conceptualized the study. ZLJ, QYL,

WJZ and DW analyzed and curated data. ZLJ, QYL, JYC and WJZ

conducted investigation. JYC designed and established the

experimental methodology. WJZ, ZLJ, QYL and DW wrote the original

draft. WJZ and HZW revised the manuscript. All authors wrote,

reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved

the final version of the manuscript. WJZ and HZW confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Digklia A and Wagner AD: Advanced gastric

cancer: Current treatment landscape and future perspectives. World

J Gastroenterol. 22:2403–2414. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Lei ZN, Teng QX, Tian Q, Chen W, Xie Y, Wu

K, Zeng Q, Zeng L, Pan Y, Chen ZS and He Y: Signaling pathways and

therapeutic interventions in gastric cancer. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 7(358)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Huang R and Zhou PK: DNA damage repair:

Historical perspectives, mechanistic pathways and clinical

translation for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target

Ther. 6(254)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Peña Q, Wang A, Zaremba O, Shi Y, Scheeren

HW, Metselaar JM, Kiessling F, Pallares RM, Wuttke S and Lammers T:

Metallodrugs in cancer nanomedicine. Chem Soc Rev. 51:2544–2582.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ruhlmann CH, Iversen TZ, Okera M, Muhic A,

Kristensen G, Feyer P, Hansen O and Herrstedt J: Multinational

study exploring patients' perceptions of side-effects induced by

chemo-radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 117:333–337. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Shahid M, Subhan F, Ahmad N and Sewell

RDE: The flavonoid 6-methoxyflavone allays cisplatin-induced

neuropathic allodynia and hypoalgesia. Biomed Pharmacother.

95:1725–1733. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Yu C, Dong H, Wang Q, Bai J, Li YN, Zhao

JJ and Li JZ: Danshensu attenuates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity

through activation of Nrf2 pathway and inhibition of NF-κB. Biomed

Pharmacother. 142(111995)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wang H, Zhang Z, Wei X and Dai R:

Small-molecule inhibitor of Bcl-2 (TW-37) suppresses growth and

enhances cisplatin-induced apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells. J

Ovarian Res. 8(3)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Shi S, Bai X, Ji Q, Wan H, An H, Kang X

and Guo S: Molecular mechanism of ion channel protein TMEM16A

regulated by natural product of narirutin for lung cancer adjuvant

treatment. Int J Biol Macromol. 223:1145–1157. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Bai X, Liu Y, Cao Y, Ma Z, Chen Y and Guo

S: Exploring the potential of cryptochlorogenic acid as a dietary

adjuvant for multi-target combined lung cancer treatment.

Phytomedicine. 132(155907)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Morahan BJ, Abrie C, Al-Hasani K, Batty

MB, Corey V, Cowell AN, Niemand J, Winzeler EA, Birkholtz LM,

Doerig C and Garcia-Bustos JF: Human Aurora kinase inhibitor

hesperadin reveals epistatic interaction between Plasmodium

falciparum PfArk1 and PfNek1 kinases. Commun Biol.

3(701)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wu X, Wu J, Hu W, Wang Q, Liu H, Chu Z, Lv

K and Xu Y: MST4 kinase inhibitor Hesperadin attenuates autophagy

and behavioral disorder via the MST4/AKT pathway in intracerebral

hemorrhage mice. Behav Neurol. 2020(2476861)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Chhajer R, Bhattacharyya A and Ali N: Cell

death in Leishmania donovani promastigotes in response to Mammalian

Aurora kinase B inhibitor-Hesperadin. Biomed Pharmacother.

177(116960)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zhang J, Liang R, Wang K, Zhang W, Zhang

M, Jin L, Xie P, Zheng W, Shang H, Hu Q, et al: Novel CaMKII-δ

inhibitor Hesperadin exerts dual functions to ameliorate cardiac

ischemia/reperfusion injury and inhibit tumor growth. Circulation.

145:1154–1168. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Zhang Y, Wu J, Fu Y, Yu R, Su H, Zheng Q,

Wu H, Zhou S, Wang K, Zhao J, et al: Hesperadin suppresses

pancreatic cancer through ATF4/GADD45A axis at nanomolar

concentrations. Oncogene. 41:3394–3408. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Carneiro BA and El-Deiry WS: Targeting

apoptosis in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 17:395–417.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Li J, Jia YC, Ding YX, Bai J, Cao F and Li

F: The crosstalk between ferroptosis and mitochondrial dynamic

regulatory networks. Int J Biol Sci. 19:2756–2771. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

To TL, Cuadros AM, Shah H, Hung WHW, Li Y,

Kim SH, Rubin DHF, Boe RH, Rath S, Eaton JK, et al: A compendium of

genetic modifiers of mitochondrial dysfunction reveals

intra-organelle buffering. Cell. 179:1222–1238.e17. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wagner AD, Syn NL, Moehler M, Grothe W,

Yong WP, Tai BC, Ho J and Unverzagt S: Chemotherapy for advanced

gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

8(CD004064)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Al-Batran SE, Homann N, Pauligk C, Goetze

TO, Meiler J, Kasper S, Kopp HG, Mayer F, Haag GM, Luley K, et al:

Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin,

oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus

cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric

or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): A

randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 393:1948–1957. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Hauf S, Cole RW, LaTerra S, Zimmer C,

Schnapp G, Walter R, Heckel A, van Meel J, Rieder CL and Peters JM:

The small molecule Hesperadin reveals a role for Aurora B in

correcting kinetochore-microtubule attachment and in maintaining

the spindle assembly checkpoint. J Cell Biol. 161:281–294.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ladygina NG, Latsis RV and Yen T: Effect

of the pharmacological agent hesperadin on breast and prostate

tumor cultured cells. Biomed Khim. 51:170–176. 2005.PubMed/NCBI(In Russian).

|

|

25

|

Hu Y, Zhang J, Musharrafieh R, Hau R, Ma C

and Wang J: Chemical genomics approach leads to the identification

of Hesperadin, an Aurora B kinase inhibitor, as a broad-spectrum

influenza antiviral. Int J Mol Sci. 18(1929)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kim HJ, Lee JH, Kim SJ, Oh GS, Moon HD,

Kwon KB, Park C, Park BH, Lee HK, Chung SY, et al: Roles of NADPH

oxidases in cisplatin-induced reactive oxygen species generation

and ototoxicity. J Neurosci. 30:3933–3946. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chen TM, Huang CM, Setiawan SA, Hsieh MS,

Sheen CC and Yeh CT: KDM5D histone demethylase identifies

platinum-tolerant head and neck cancer cells vulnerable to mitotic

catastrophe. Int J Mol Sci. 24(5310)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Han X, Zhang JJ, Han ZQ, Zhang HB and Wang

ZA: Let-7b attenuates cisplatin resistance and tumor growth in

gastric cancer by targeting AURKB. Cancer Gene Ther. 25:300–308.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Erickson JR, Joiner ML, Guan X, Kutschke

W, Yang J, Oddis CV, Bartlett RK, Lowe JS, O'Donnell SE,

Aykin-Burns N, et al: A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent

activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell. 133:462–474.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Anderson ME, Brown JH and Bers DM: CaMKII

in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol.

51:468–473. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zhang Z, Zhao X, Gao M, Xu L, Qi Y, Wang J

and Yin L: Dioscin alleviates myocardial infarction injury via

regulating BMP4/NOX1-mediated oxidative stress and inflammation.

Phytomedicine. 103(154222)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Drummond GR, Selemidis S, Griendling KK

and Sobey CG: Combating oxidative stress in vascular disease: NADPH

oxidases as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 10:453–471.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Jiang S, Li H, Zhang L, Mu W, Zhang Y,

Chen T, Wu J, Tang H, Zheng S, Liu Y, et al: Generic diagramming

platform (GDP): A comprehensive database of high-quality biomedical

graphics. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1):D1670–D1676. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|