Introduction

Meningiomas are the most common primary intracranial

tumors, originating from arachnoid cap cells (1) and classified into WHO Grades 1, 2 and

3, based on various histological and anaplastic features, number of

mitotic figures, invasive growth patterns and genetic

characteristics (2). While most

cases are benign Grade 1 tumors (80.5%), Grades 2 and 3 comprise

17.7 and 1.7%, respectively, and exhibit more aggressive behavior

(3). Distant metastasis occurs in

only 0.18% of cases, typically to the lungs, bones, spinal cord and

liver, and is associated after the primary tumor has been diagnosed

(93%). However, ~6% of metastatic meningiomas are found

simultaneously with the primary tumor at the time of diagnosis.

Metastatic meningiomas are associated with male sex, large tumor

size and WHO Grade 3(4). The

first-line treatment for all meningiomas is surgical resection

(5); however, surgery is not

entirely effective, as recurrences are reported more frequently in

patients with higher-grade tumors, even after extensive surgical

resection (6). Consequently, these

tumors are more likely to grow steadily and recur. Therefore,

treatments for high-grade meningiomas are still limited and are

being developed to better manage the morbidity and mortality of

patients with meningiomas (7).

One emerging area of interest in understanding the

aggressive behavior of such tumors is the study of sialylation, a

post-translational modification known to influence cancer

progression. Sialylation, the addition of sialic acids to proteins

and lipids, is a critical post-translational modification that

influences cell signaling, recognition and immune responses.

Sialylation occurs via three prominent linkages: α2,3, α2,6 and

α2,8, which are catalyzed by a group of sialyl-transferases (STs).

This process plays a crucial role in various biological functions

and cellular activities, such as cell-cell communication, cellular

recognition and cell adhesion, and affects the circulating

half-lives of numerous glycoproteins (8). Aberrant sialylation resulting from

altered expression of ST genes has been implicated in cancer

progression and development (9).

Alterations in this process can lead to changes in protein

structure or impair their function, thereby promoting oncogenic

activities, such as increased cell proliferation and survival. In

particular, aberrant sialylation, increased tumor growth, and

metastasis have been widely described (10). For instance, the addition of

α2,6-linked sialic acid to β1 integrin increases its affinity for

collagen I, thereby enhancing tumor cell migration and invasion

(11). Similarly, α2,3-sialylation

of CD44 enhances its interaction with hyaluronic acid (12), which in turn promote further cancer

cell migration and metastasis. While the role of sialylation in the

progression of various cancers has been extensively studied, its

specific impact on the progression and aggressiveness of

meningiomas remains poorly understood.

The presence of sialylated tumor-associated

carbohydrate antigens, such as sialyl Tn (STn), is frequently

linked to poor clinical outcomes due to their role in promoting

tumor invasiveness (13).

Additionally, a previous study by the authors found that patients

with meningiomas exhibit altered expression of glycosyl-transferase

enzymes (14). The present study

aims to investigate the expression patterns of STs specifically

β-galactoside α2,3 and α2,6 ST family members in different grades

of meningiomas and examine how altering sialylation affects the

migratory and invasive capabilities of meningioma cells.

Materials and methods

Gene expression analysis by Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets

The gene expression levels of β-galactoside α2,3 and

α2,6 ST family members in meningiomas were retrieved from GEO

database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), including entries

GSE16581, GSE74385, GSE136661 and GSE43290. Information on each GEO

entry is presented in Table I.

GEO2R is an interactive web tool that enables users to compare two

or more groups of Samples in a GEO series to identify genes that

are differentially expressed across experimental conditions. Thus,

all expression data from each GEO entry were used in GEO2R to

identify genes that were differentially expressed among the WHO

Grade 1, 2 and 3 meningiomas. All expression data were transformed

to log2 for analysis. The differential expression of ST genes

across WHO grades 1, 2 and 3 meningiomas was analyzed using

GraphPad Prism® (version 8.0; GraphPad Software, Inc.;

Dotmatics). Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

| Table IGEO entries used in the present

study. |

Table I

GEO entries used in the present

study.

Cell culture and 3Fax treatment

The human HKBMM cell line (Meningioma WHO grade 3)

was provided by Associate Professor Norie Araki (Kumamoto

University, Kumamoto, Japan). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's

Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; cat. no. 121000-046; MilliporeSigma)

supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS;

cat. no. A5256701; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. 15140-122; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The cells were cultured in a humidified

incubator at 37˚C under 5% CO2. For 3Fax treatments, the

HKBMM cell line, at a cell density of 2x104 cells, was

seeded into a 24-well plate and cultured overnight in DMEM

containing 10% FBS. After overnight seeding, the culture

supernatant was replaced with a new medium containing 500 µM

3Fax-peracetyl-Neu5Ac (3Fax; cat. no. 566224; Merck KGaA) or DMSO

(cat. no. 04707516001; DMSO; Carlo Erba™) as a control, and the

cells were incubated for five days. The expression of sialic acids

using Maackia amurensis lectin II (MAL II) and Sambucus

nigra lectin (SNA; cat. no. PK-4000; Vector Laboratories Inc.)

staining was performed on both treated and control cells, and the

results were analyzed using an AttuneTM NxT Acoustic

Focusing Cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). FACS data were

analyzed using Flowing software version 2.5.1 (Turku Bioscience).

Sialic acid expression was measured before subsequent experiments.

The experiment was performed in three replicates.

Lectin staining and flow cytometry

analysis

3Fax-treated cells and control cells were

trypsinized using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (cat. no. 25200-072; Gibco;

Thermo fisher Scientific, Inc.) and centrifuged at 400 x g for 3

min at 4˚C. The cell pellets were washed by resuspending in 1X PBS.

The cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde in 1X PBS for 15 min

at room temperature. The fixed cells were then blocked for

non-specific binding with 2% BSA (HIMedia Laboratories, LLC) in 1X

PBS for 30 min on ice. Next, the cells were stained with SNA and

MAL II biotinylated lectin for 1 h on ice. After staining, the

stained cells were incubated with streptavidin-Alexa Fluor™ 488

conjugate (cat. no. S11223; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 30

min on ice. The cells were then resuspended in 2% FACS buffer and

analyzed using an AttuneTM NxT Acoustic Focusing

Cytometer. Forward and side scatter were used to select the

population. The BL1 channel was used to detect the expression of

SNA and MAL II positivity, and a histogram represented the positive

expression. The FACS data were analyzed using the Flowing software

version 2.5.1 (Turku Bioscience). The experiment was performed in

three replicates.

Cell proliferation by WST-8 viability

assay

3Fax-treated cells and control cells were

trypsinized, seeded at a density of 1,000 cells per well in a

96-well plate and incubated overnight. Cell proliferation was

measured daily using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (WST-8; cat. no.

ab228554; Abcam) at 10 µl per well for 7 days. Briefly, the cells

were incubated with the WST-8 solution for 3 h at 37˚C under 5%

CO2, and cell viability was assessed by measuring the

absorbance at 460 nm using a TECAN Infinite 200 Pro microplate

reader (Tecan Group, Ltd.). The experiment was performed in three

replicates.

Cell proliferation and survival by

colony formation assay

3Fax-treated cells and control cells were

trypsinized, seeded at a density of 500 cells in a 100-mm culture

dish and incubated overnight. The cells were cultured in complete

DMEM containing 10% FBS and incubated at 37˚C under 5%

CO2 for 14 days. The cells were then washed with 1X PBS,

fixed with absolute methanol for 30 min at -4˚C, and stained with

5% crystal violet for 30 min at room temperature (RT).

Subsequently, the stained cells were washed with tap water, and

images of colony formation were captured under a stereomicroscope.

Only colonies with >50 cells were included in the count. The

experiment was performed in three replicates.

Wound healing assay

The cells were seeded at a density of

2x104 cells in a 24-well plate and cultured overnight in

DMEM containing 10% FBS. After seeding for 24 h, the culture

supernatant was replaced with a new medium containing 500 µM of

3Fax or DMSO and incubated for 5 days to reach 90% confluence. The

3Fax-treated and control cells were scratched using 200-µl pipette

tips to create a cell-free area. The medium was then replaced with

serum-free medium. The cells were further incubated, and wound

closure in the cell-free area was assessed at 18 and 24 h. The

cell-free area was captured using an inverted light microscope, and

the images were analyzed using ImageJ software (version 1.54 g;

National Institutes of Health). Wound closure was calculated using

the following formula: (area of original wound-area of wound during

healing)/area of original wound. The experiment was performed in

three replicates.

Transwell migration and invasion

assay

The Transwell migration assay utilized 6.5 mm

inserts with 8.0-µM polycarbonate membranes (cat. no. 3422; Costar®

Transwell®; Corning Inc.) in 24-well plates. In the Transwell

invasion assay, Matrigel (cat. no. 354234; Corning Inc.) was

thawed, and 100 µl of a 6 mg/ml Matrigel matrix was added to 6.5-mm

inserts with 8.0-µM polycarbonate membranes. Matrigel was spread

evenly using a pipette tip and incubated at 37˚C for 2 h to allow

Matrigel to solidify. Subsequently, 3Fax-treated and control cells

at a density of 3x104 cells were suspended in 200 µl of

serum-free medium and seeded into the upper chamber. Meanwhile, 600

µl of DMEM containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. The

cells were then incubated for 18 and 24 h. The cells that had

crossed the membrane were fixed with 10% trichloroacetic acid at

4˚C overnight and stained using the Sulforhodamine B colorimetric

assay according to a previous study (15) for visualization. Images were

captured using an inverted light microscope at x10 magnification.

The number of migratory cells was counted and analyzed using ImageJ

software (version 1.54 g; National Institutes of Health). The

experiment was performed in three replicates.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

3Fax-treated and control cells were extracted from

total RNA using TRIzol reagent (cat. no. 15596026; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The

quantity and purity of RNA were measured using a NanoDrop 2000

spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RNA purity was

indicated via the A260/A280 nm ratio >1.8. RNA quality was

assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis. Total RNA was then

reverse transcribed into cDNA using the SensiFAST cDNA Synthesis

Kit (cat. no. 65054; Meridian Bioscience) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was performed on the generated cDNA

to evaluate the expression levels of epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT)-related transcription factors (TFs) and

EMT-related proteins using iTag Universal SYBR Green Supermix (cat.

no. 1725121; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The thermocycling

conditions were performed by initial denaturation at 95˚C for 5

min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95˚C for 10 sec,

annealing at 55-63˚C for 10 sec and a final extension at 72˚C for

10 sec. The primers used and annealing temperatures for all

investigated genes in this experiment are shown in Table II. The beta-actin gene was used as

an internal control to normalize gene expression, and the relative

mRNA expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq

method (16). The experiment was

performed in three replicates.

| Table IIPrimer sequences used in expression

of EMT markers. |

Table II

Primer sequences used in expression

of EMT markers.

| Assay | Gene name | Primer sequence

(5'-3') | Annealing

temperature (˚C) |

|---|

| EMT-related

transcription factors | Slug | F: GCC TCC AAA AAG

CCA AAC TAC | 62 |

| | | R: GAG GAT CTC TGG

TTG TGG TAT GAC | |

| | ZEB1 | F: ACC TCT TCA CAG

GTT GCT CCT | 62 |

| | | R: AGT GCA GGA GCT

GAG AGT CA | |

| | Snail | F: TTC TCA CTG CCA

TGG AAT TCC | 62 |

| | | R: GCA GAG GAC ACA

GAA CCA GAA | |

| EMT-related

proteins | CDH1 | F: TAC GCC TGG GAC

TCC ACC TA | 62 |

| | | R: CCA GAA ACG GAG

GCC TGA T | |

| | CDH2 | F: ATC CTG CTT ATC

CTT GTG CTG | 60 |

| | | R: GTC CTG GTC TTC

TTC TCC TCC | |

| | MMP2 | F: CGT CTG TCC CAG

GAT GAC ATC | 63 |

| | | R: ATG TCA GGA GAG

GCC CCA TA | |

| | MMP7 | F:

CAGATGTGGAGTGCCAGATG | 60 |

| | | R:

TGTCAGCAGTTCCCCATACA | |

| | MMP9 | F: TTC CAG TAC CGA

GAG AAA GCC TAT | 62 |

| | | R: GGT CAC GTA GCC

CAC TTG GT | |

| Internal

control | ACTB | F: GAT CAG CAA GCA

GGA GTA TGA CG | 55-63 |

| | | R: AAG GGT GTA ACG

CAA CTA AGT CAT AG | |

SDS-PAGE and western blot

analysis

3Fax-treated cells and control cells were collected

for preparation of whole-cell lysate using protein lysis buffer

containing 10% TritonX, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche

Diagnostics GmbH) and Tris-lysis buffer pH 7.5. The protein

concentrations of all samples were determined using the Pierce BCA

Protein Assay Kit (cat. no. 2322, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Total proteins (50 µg) were subjected to 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (cat.

no. 1060003; MilliporeSigma). Non-specific binding was blocked

using 5% BSA at RT for 1 h. The membrane was probed with a specific

primary antibody overnight at 18˚C. The primary antibodies used

were matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP 9; cat. no. 3852),

Snail (cat. no. 3879), Akt (cat. no. 4685), phosphorylated

(p-)Akt (cat. no. 4060), Erk (cat. no. 4695) and p-Erk (cat. no.

9101); all antibodies were diluted at 1:1,000 and purchased from

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Simultaneously, β-actin (cat. no.

sc-47778) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. After

incubation, secondary antibodies were added at a dilution of

1:2,000 and incubated for 1 h at RT. Anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked

antibody (cat. no. 7074) and anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked antibody

(cat. no. 7076) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.

Immunodetection using a chemiluminescent HRP substrate was

performed to visualize the target protein signals using ImageQuant™

LAS 500 (Cytiva). The density bands of each target protein were

captured using ImageJ software (version 1.54 g; National Institutes

of Health). The experiment was performed in three replicates.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism® (version

8.0; GraphPad Software, Inc.; Dotmatics). One-way ANOVA followed by

Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test was used to determine the

differential expression of ST genes across WHO Grade 1, 2 and 3

meningiomas. Differences between the two groups were further

analyzed using unpaired t-tests. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

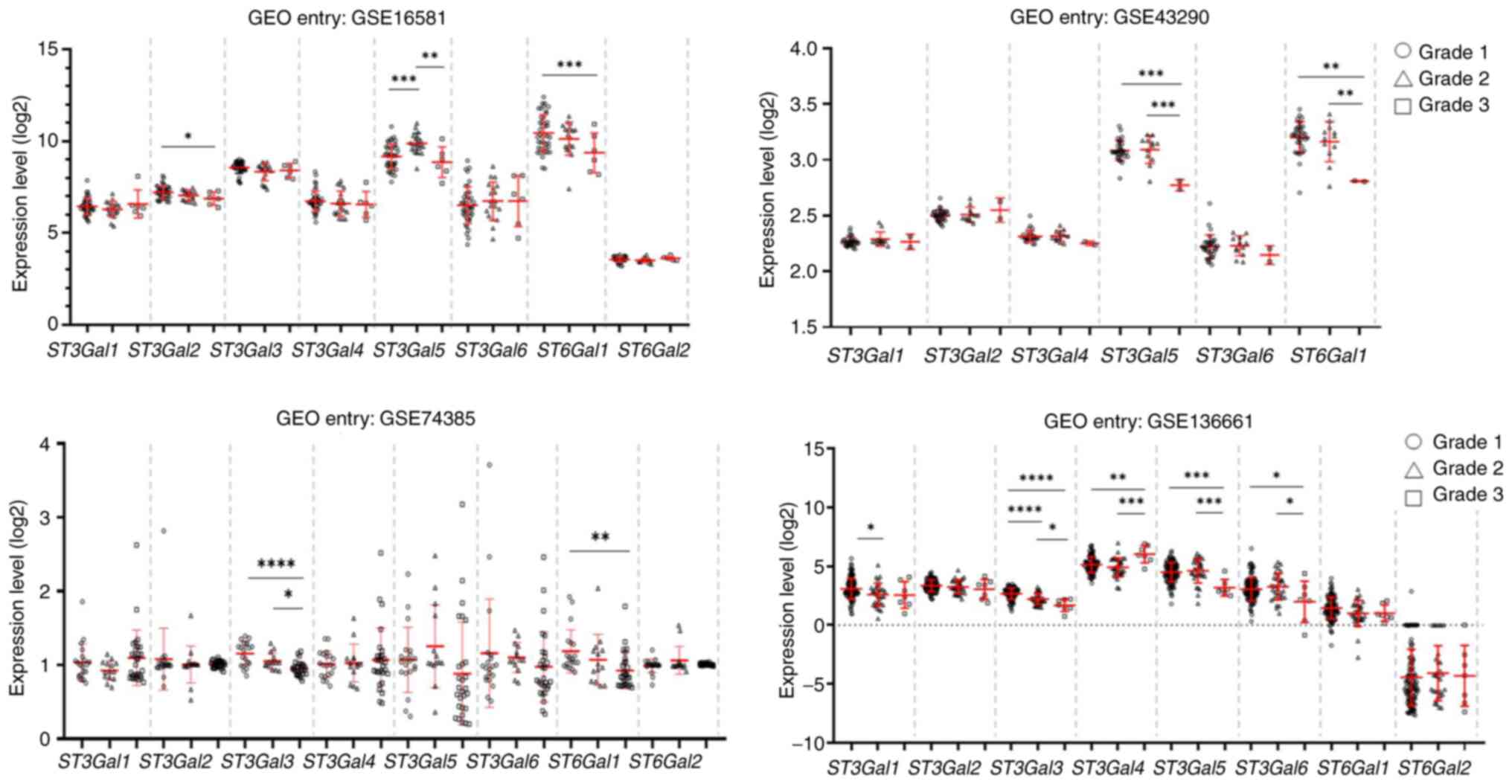

Downregulation of ST genes is

associated with the progression of meningiomas

To address the significance of ST in meningioma

development and progression, the gene expression of β-galactoside

α2,3 and α2,6 STs (ST3Gals and ST6Gals), including ST3Gal1, 2,

3, 4, and 5, and ST6Gal1 and 2, was obtained from four

GEO datasets: GSE16581, GSE43290, GSE74385 and GSE136661. The

results demonstrated that downregulation of the ST3Gal2,

ST3Gal3, ST3Gal4, ST3Gal5 and ST6Gal1 genes was observed

across four datasets and was associated with WHO Grade 3

meningiomas. Additionally, decreased expression of ST3Gal3 was

commonly observed in two datasets (GSE74385 and GSE136661), whereas

decreased expression of ST3Gal5 was observed in three

datasets, including GSE16581, GSE43290 and GSE136661. Moreover, the

expression of ST6Gal1 was significantly lower in WHO Grade 3

meningiomas than in WHO Grade 1 meningiomas in GSE16581, GSE43290

and GSE74385 (Fig. 1). These

findings suggested that the downregulation of these STs may play a

crucial role in meningioma progression.

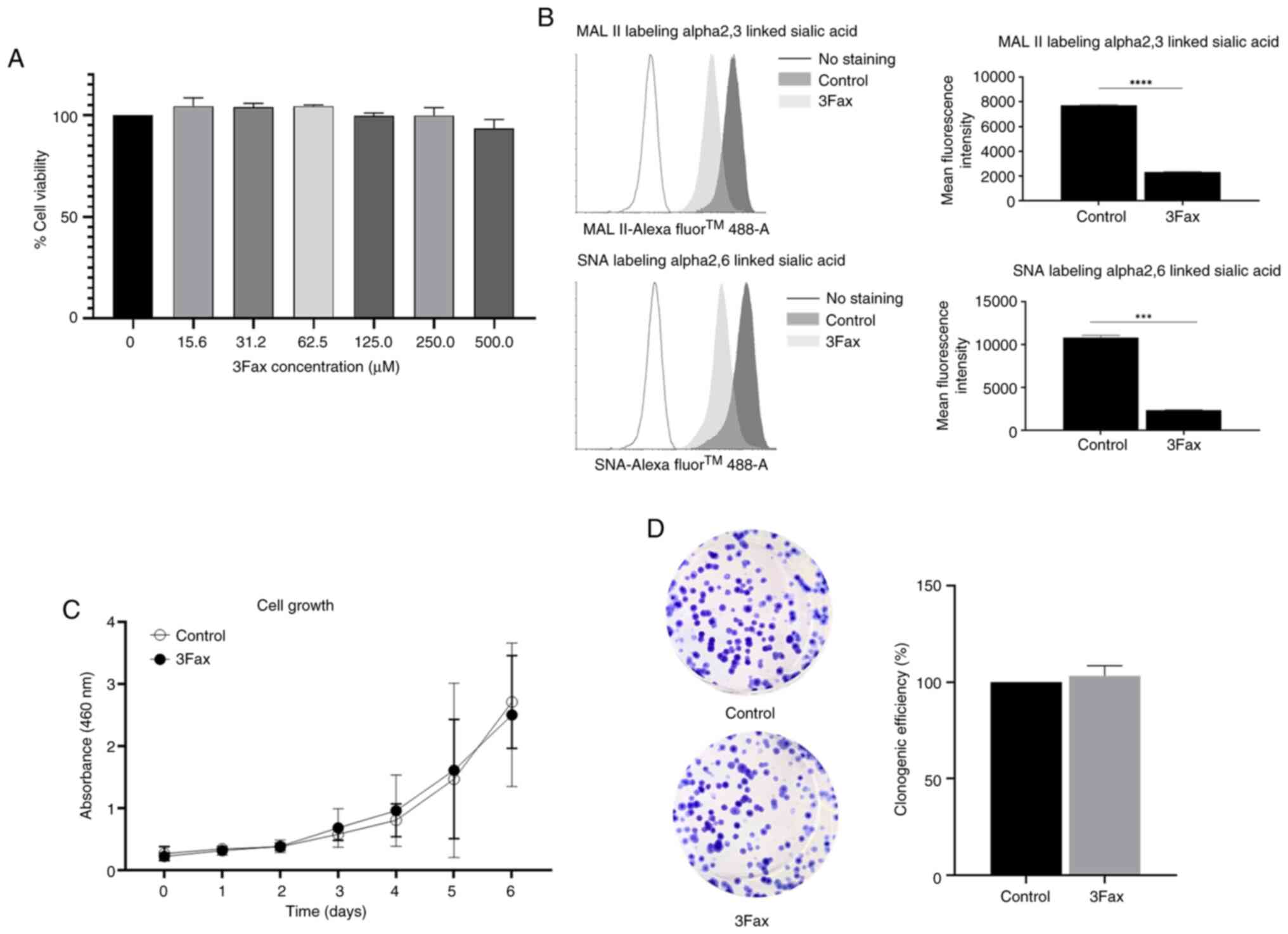

Suppression of ST activity does not

affect meningioma cell proliferation

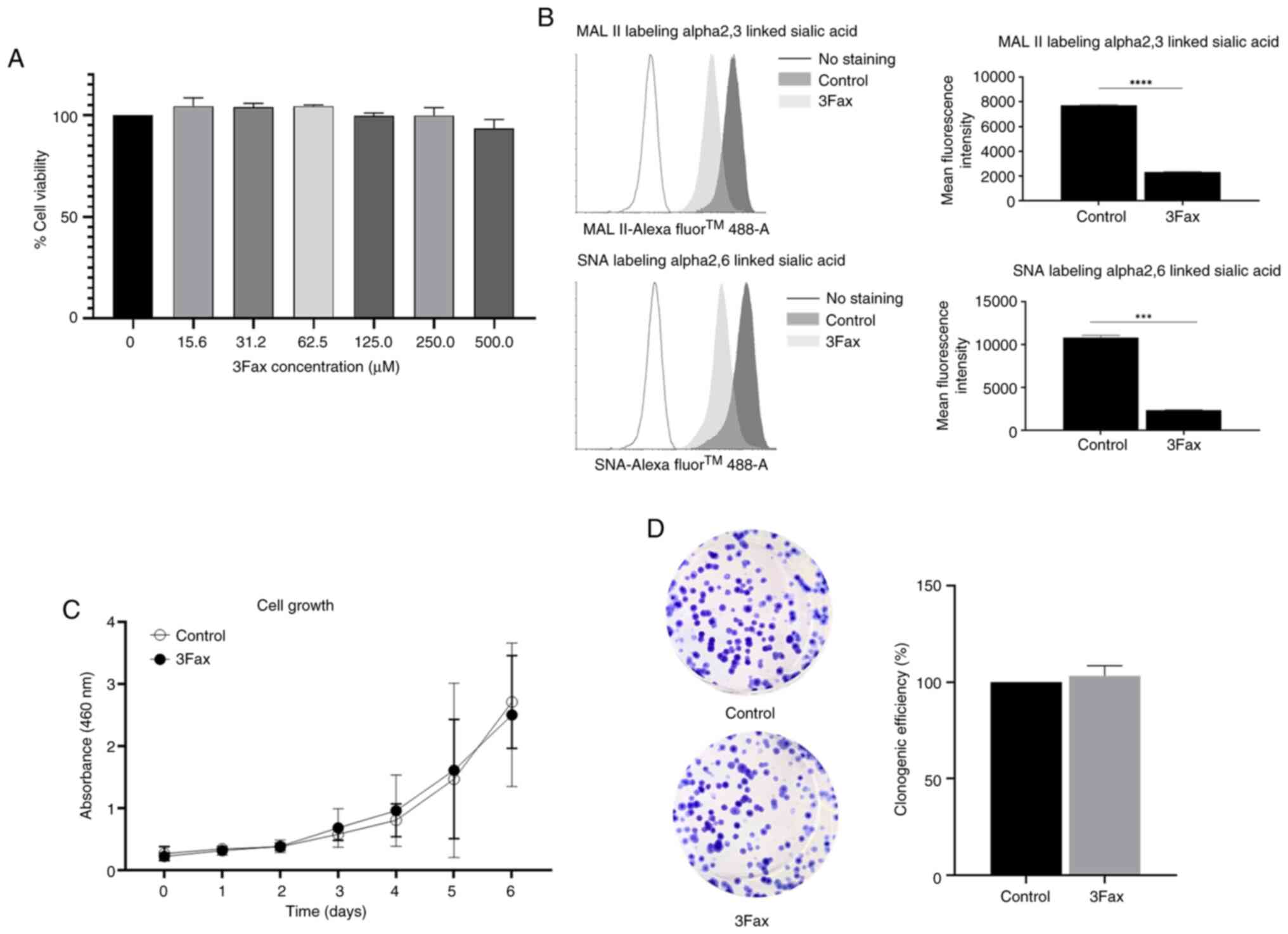

To investigate the role of ST in meningioma

development and progression, a malignant meningioma cell line,

HKBMM, was selected for functional studies. Talabnin et al

(14) demonstrated the high

expression of sialic acids and ST genes in HKBMM cells. HKBMM cells

were treated with a ST inhibitor (3Fax) or DMSO for 5 days. The

cell viability test demonstrated that 3Fax at 500 µM was not toxic

to HKBMM cells (Fig. 2A) and was

therefore selected for subsequent experiments. Surface sialic acid

expression was measured using MAL II to detect α2,3-sialylated

glycans and SNA to detect α2,6-sialylated glycans. The results

demonstrated that the staining intensities of both α2,3- and

α2,6-sialylated glycans were significantly reduced in 3Fax-treated

cells, indicating successful inhibition of sialylation (Fig. 2B). It was then investigated whether

the suppression of sialylation affects the proliferation of

meningioma cells. 3Fax-treated cells and control cells were used to

monitor cell proliferation via cell proliferation and colony

formation assays. The results showed no significant difference in

cell proliferation and survival (Fig.

2C and D) between the

3Fax-treated and control cells.

| Figure 2Suppression of sialylation does not

affect the proliferation of meningioma cells. HKBMM cells were

treated with various concentrations of 3Fax (0, 15.6, 31.2, 62.5,

125.0, 250.0, 500.0 µM) for 5 days. (A) Cytotoxic effect of 3Fax

was assessed using the WST-8 viability. (B) Histogram plots and

mean fluorescence intensity from lectin flow cytometry showed

decreased expression of α2,3-linked MAL II and α2,6-linked SNA

lectin sialic acids in 3Fax-treated cells (500 µM) compared with

DMSO-treated control cells. (C and D) Cell proliferation and

survival were assessed using the (C) WST-8 viability and (D) colony

formation assays. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation from three independent experiments. ***P≤0.001

and ****P≤0.0001 vs. control. MAL II, Maackia

amurensis lectin II; SNA, Sambucus nigra lectin. |

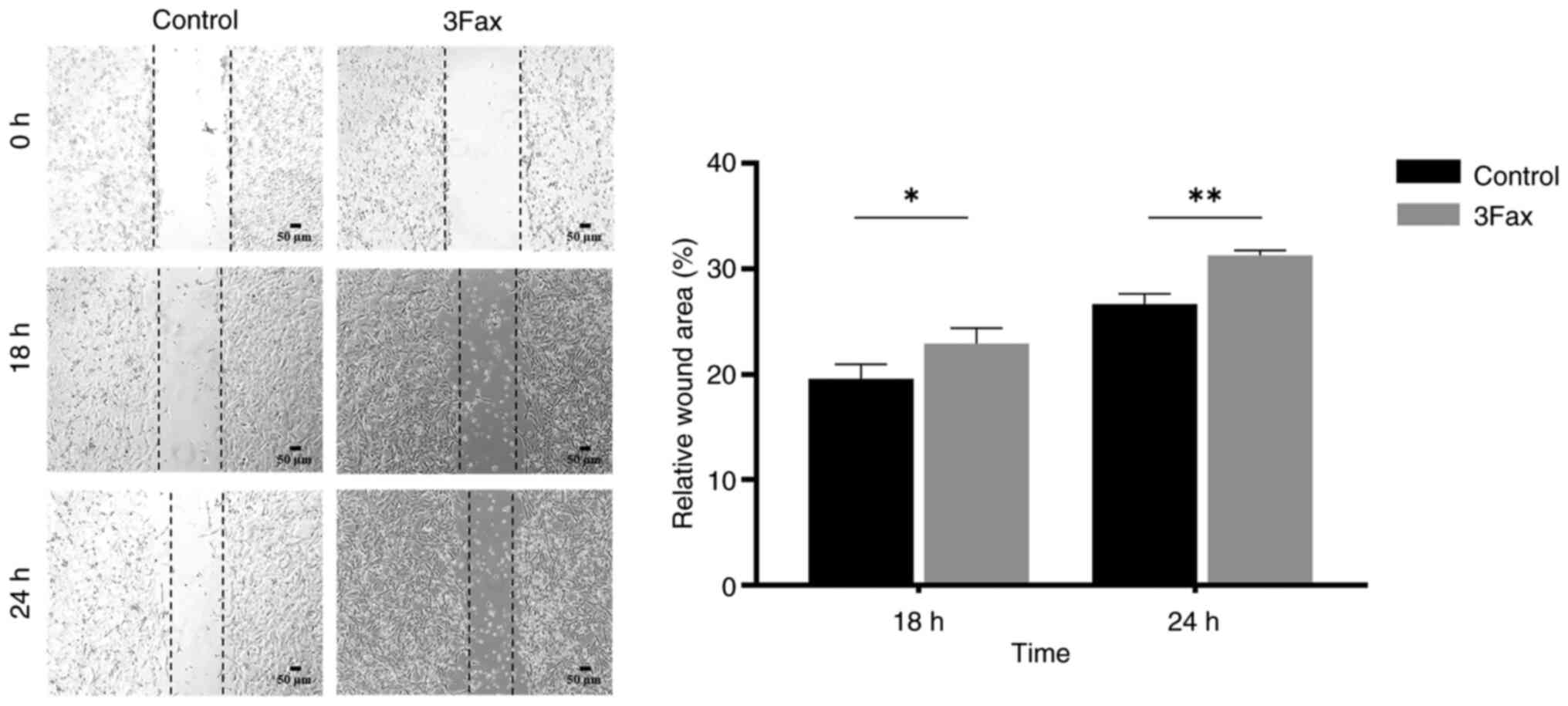

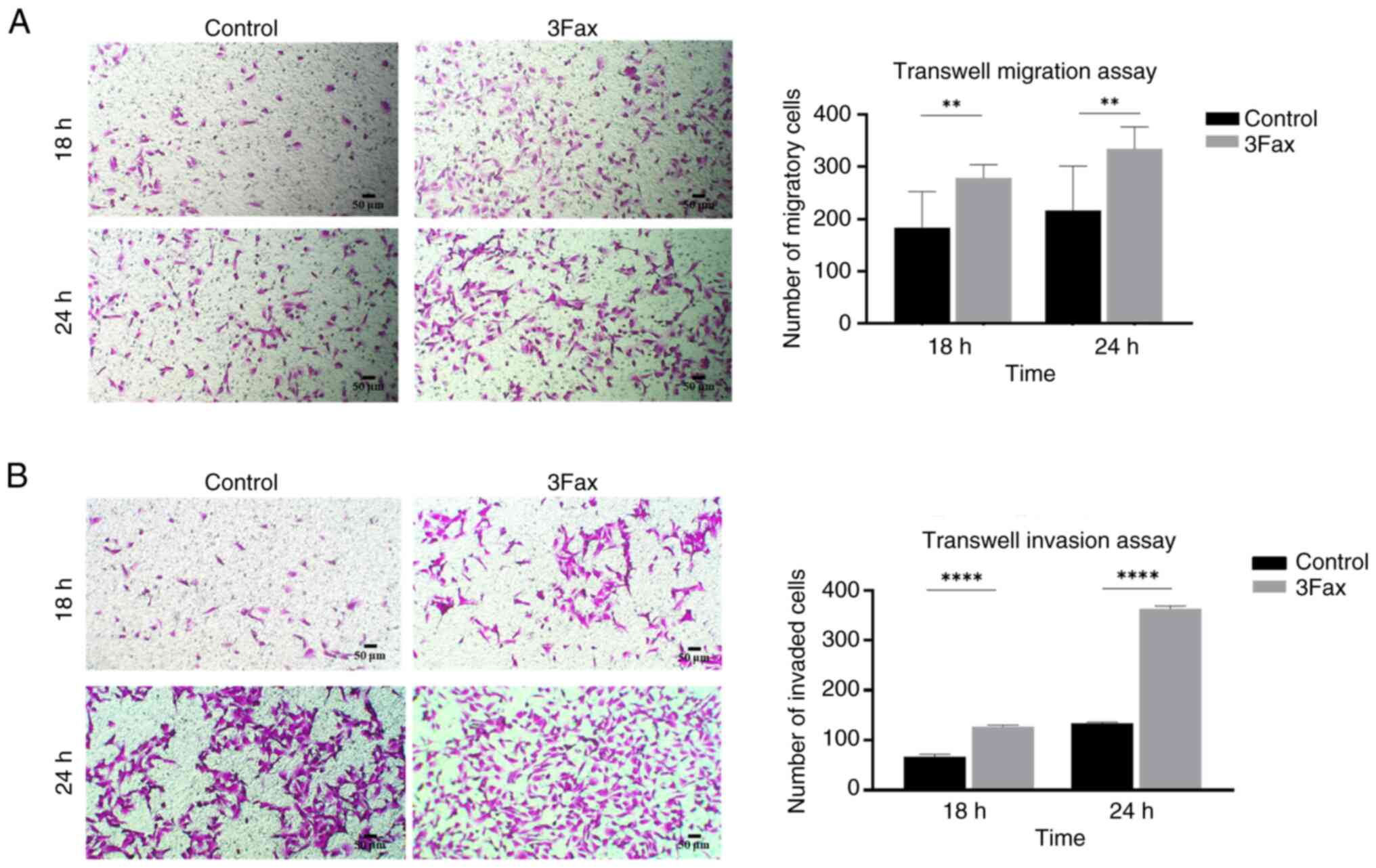

Suppression of ST activity promotes

migration and invasion abilities in the malignant meningioma

cells

To determine whether the suppression of sialylation

affects the migration and invasion of meningioma cells, wound

healing and Transwell migration or invasion assays were performed.

The wound healing assay demonstrated that the 3Fax-treated cells

had the ability to close the wound faster than the control cells at

both 18 h (% wound area: 19.6+1.0% vs. 22.9+1.2%, P<0.05) and 24

h (% wound area: 26.7+0.8% vs. 31.3+0.4%, P<0.01) (Fig. 3). These findings are consistent with

the results of the Transwell migration assay at 18 h (number of

migratory cells: 183+64 vs. 278+23, P<0.01) and 24 h (number of

migratory cells: 216+79 vs. 334+39, P<0.01) (Fig. 4A). Additionally, the Transwell

invasion assay showed that 3Fax-treated cells had a greater ability

to invade the extracellular matrix than control cells in a

time-dependent manner (number of invasive cells at 18 h: 66+4 vs.

127+2 and at 24 h: 134+1 vs. 363+4, P<0.0001) (Fig. 4B). These findings suggested that the

suppression of sialylation enhances the aggressive characteristics

of malignant meningioma cells.

Suppression of ST activity promotes

the progression of meningiomas via EMT and the activation of

ERK/AKT pathways

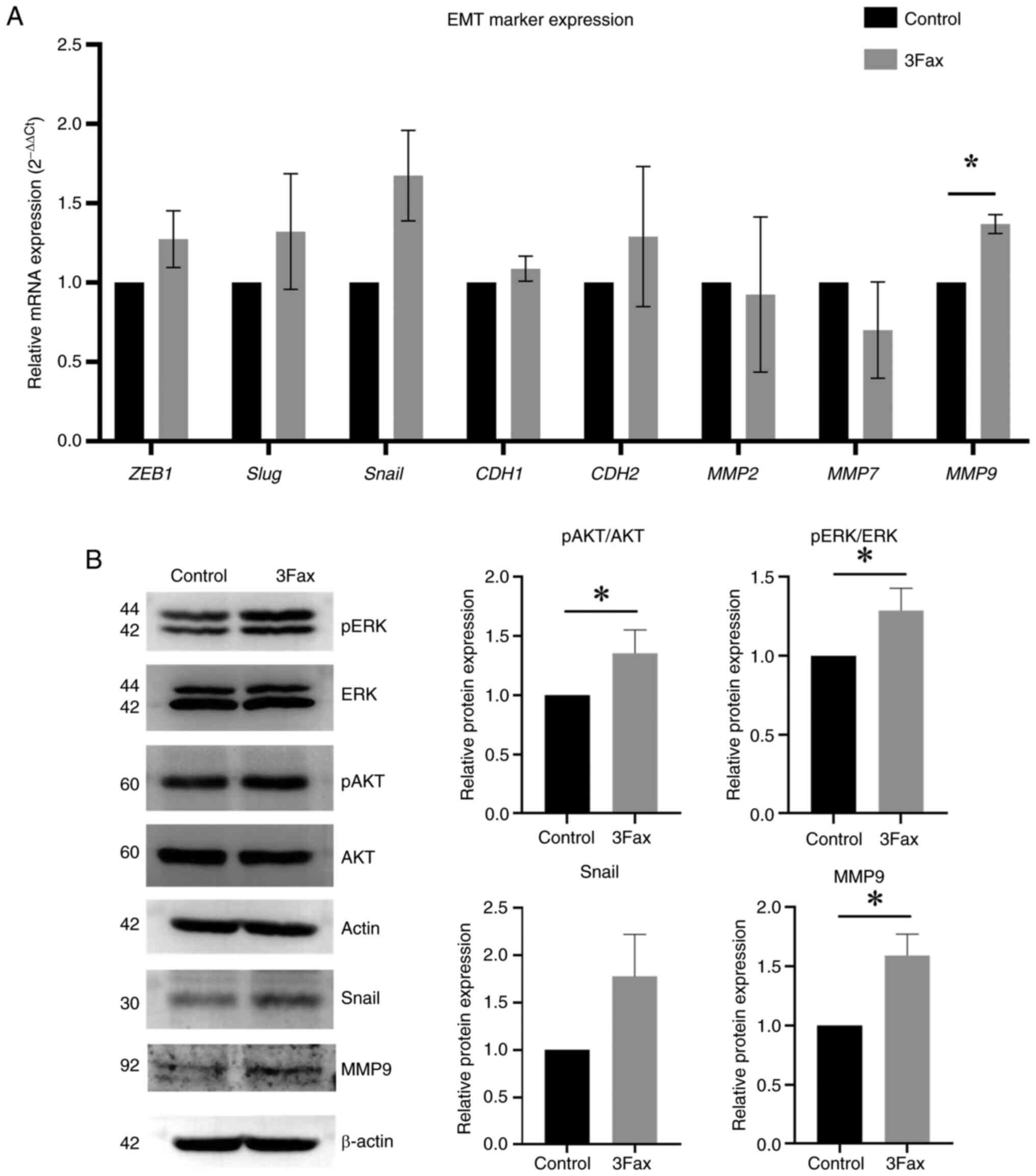

The present study aimed to investigate whether the

suppression of sialylation enhances the aggressive characteristics

of malignant meningioma cells via EMT. The expression levels of

EMT-related TFs (ZEB1, Snail and Slug) and

EMT-related proteins (N-cadherin, E-cadherin and MMP2, 7 and

9 were determined in 3Fax-treated and control cells. The

results demonstrated that the expression of EMT-related TFs

(Snail: 1.7-fold change, P<0.05) and EMT-related proteins

(MMP9, 1.4-fold change) were increased in

3Fax-treated cells compared with the control (Fig. 5A). Western blot analysis

demonstrated an increase in the expression of MMP9 (1.6-fold

change, P<0,05), Snail (1.8-fold change), phosphorylation of AKT

(1.4-fold change, P<0.05) and ERK (1.3-fold change, P<0.05)

in 3Fax-treated cells (Fig. 5B).

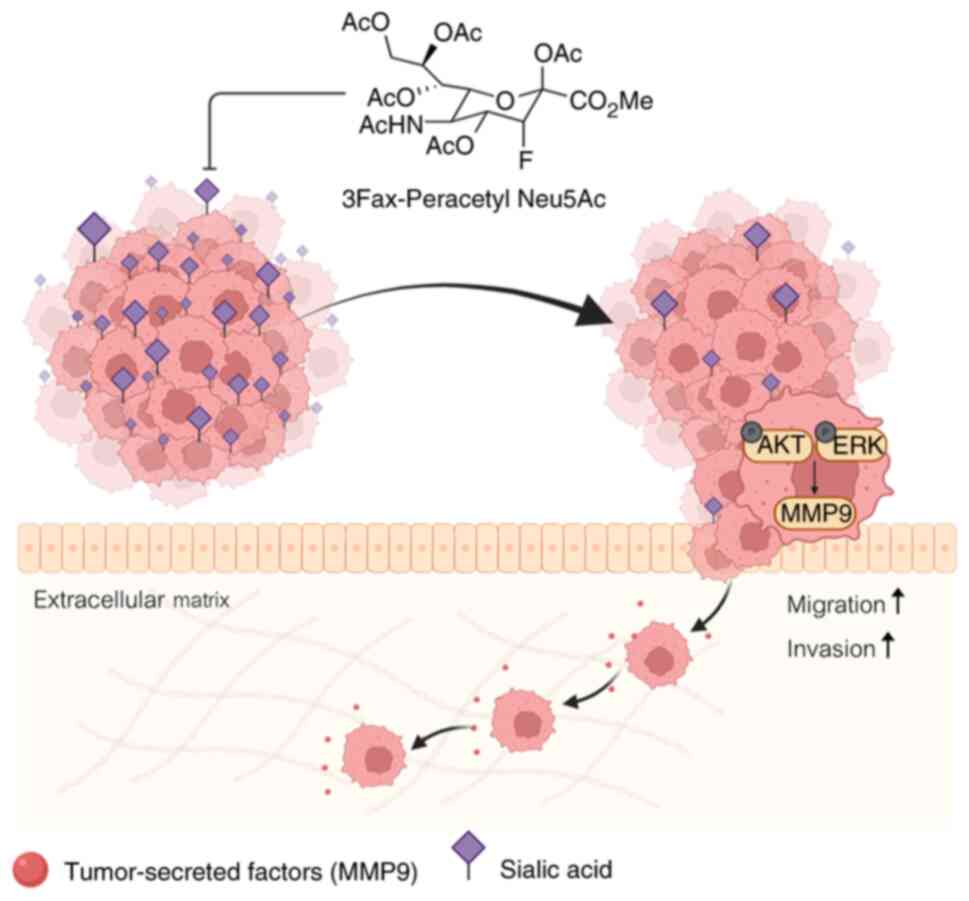

These findings suggested that the suppression of ST activity

promotes cell migration and invasion by enhancing the EMT process

and activating the AKT/ERK pathways (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Aberrant sialylation is associated with cancer

progression by promoting tumor growth and metastasis (17), facilitating immune escape (17), conferring resistance to apoptosis

(18) and enhancing tumor

angiogenesis (19). In the present

study, the differential expression of β-galactoside α2,3 and α2,6

STs (ST3Gals and ST6Gals) was demonstrated in WHO Grade 1, 2 and 3

meningiomas using four different GEO datasets. The role of

sialylation in meningioma progression was further investigated by

chemically suppressing ST activity in malignant meningioma cells.

It was found that sialylation suppression plays a crucial role in

promoting the migration and invasion of malignant meningioma

cells.

In the GEO datasets (GSE16581, GSE43290, GSE74385

and GSE136661), the downregulation of ST3Gal5 and

ST6Gal1 was commonly observed across all four datasets and

was associated with high-grade meningiomas. These results are

consistent with studies in which downregulation of ST6Gal1

is associated with metastasis in liver cancer and

cholangiocarcinoma (20,21). Nevertheless, the upregulation of STs

is commonly observed in multiple cancer types and is associated

with tumor progression (22). The

role of ST in meningioma development and progression has not yet

been reported. In the present study, suppression of ST activity by

a pan-sialylation inhibitor (3Fax-peracetyl-Neu5Ac, 3Fax) did not

affect the proliferation or survival of malignant meningioma cells.

Several studies have demonstrated that aberrant ST expression is

primarily associated with invasion, metastasis and chemoresistance

(22). In breast cancer, ST3Gal3

has been found to induce invasiveness and metastasis by regulating

the integrinB1/MMP2/9 axis, and ST6Gal1 can promote the

invasiveness of breast cancer cells through TGF-β signaling

(23,24).

By contrast, suppression of sialylation promoted

meningioma cell migration and invasion. A similar observation was

made in colon cancer, where the depletion of ST6Gal1 enhanced the

migration and invasion of colon cancer cells (25). Additionally, ST6Gal1 silencing

promoted liver metastasis in vivo by reducing the cellular

pool of the metastasis suppressor KAI1(26). Furthermore, downregulation of

ST6Gal1 decreased α2,6 sialylation on MCAM, enhanced the

interaction between MCAM and galectin-3, leading to the

dimerization of MCAM on the cell surface and subsequently promoting

liver cancer metastasis (20).

Moreover, it was demonstrated that suppression of sialylation in

meningioma cells (HKBMM) induced EMT by increasing the expression

of Snail and MMP9. The present findings suggested that

sialylation by ST serves a protective function during meningioma

progression. However, this mechanism could be considered cell

type-specific because our explorations were performed using only

HKBMM cells. Therefore, further investigation is required in other

meningioma cell lines to confirm this.

EMT mechanisms are involved, including cytoskeletal

reorganization, altered expression of adhesion molecules, and

degradation of the basement membrane through the activation of MMP2

and MMP9(27). In multiple

carcinomas, activation of EMT results in a significant increase in

cancer cell proliferation and extravasation, enabling the expansion

of metastasis (28). In addition,

MMP9 has been observed in various malignancies, and overexpression

of MMP9 is positively correlated with poor prognosis and metastasis

in patients with cancer. MMP9 can interact with and proteolyze cell

surface proteins (CD44, E-cadherin, and α/β integrins) to promote

cell migration and invasion. Various downstream pathways, including

the PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways, as well as various TFs, such as

NF-κB, SP1, AP1 and Snail, appear to play a significant role

in MMP9 expression and secretion (29,30).

In the present study, it was demonstrated that suppression of ST

activity markedly induced AKT and ERK phosphorylation. Taken

together, the current findings from in vitro experiments

suggest that the suppression of ST activity by a pan-sialylation

inhibitor (3Fax) enhances meningioma progression through the

AKT/ERK pathways. However, further in vivo studies are

required to establish the role of STs in meningioma progression.

Notably, the role of ST in meningiomas was demonstrated using a

pan-sialylation inhibitor. Therefore, further studies using

gene-specific knockdown or Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short

Palindromic Repeats techniques are required to identify which

specific ST plays a critical role in the progression of meningioma

and to investigate the underlying mechanism of the candidate ST

through the interaction with glycoprotein partners such as MCAM and

CD44.

In summary, differential expression of STs was

observed across the three grades of meningioma, suggesting

downregulation of ST gene expression in malignant meningiomas.

Additionally, suppression of sialylation using a ST inhibitor

significantly enhanced meningioma cell migration and invasion by

inducing the EMT process. These findings suggest that sialylation

plays an important role in meningioma progression. Therefore, the

sialylation status of meningioma tissues, as determined by MAL II

and SNA staining, could be a promising biomarker for assessing

meningioma progression.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr Bryan Roderick

Hamman (Publication Clinic, Research Affairs, Faculty of Medicine,

Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand) for assistance

with the English language editing of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by Suranaree University

of Technology, Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI),

National Science, Research, and Innovation Fund (NSRF) (grant no.

195616) and National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) (grant no.

N41A670301).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

CT and KT acquired funding, designed the study and

revised the manuscript. PJ and CT performed the biological

experiments and analyzed the data. PJ and CT confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. KT, PA and PK analyzed and

interpretated the data. PJ drafted the manuscript. All authors read

and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Marosi C, Hassler M, Roessler K, Reni M,

Sant M, Mazza E and Vecht C: Meningioma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol.

67:153–171. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von

Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD,

Kleihues P and Ellison DW: The 2016 World Health Organization

classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary.

Acta Neuropathol. 131:803–820. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Ogasawara C, Philbrick BD and Adamson DC:

Meningioma: A review of epidemiology, pathology, diagnosis,

treatment, and future directions. Biomedicines.

9(319)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Vuong HG, Ngo TNM and Dunn IF: Incidence,

risk factors, and prognosis of meningiomas with distant metastases

at presentation. Neurooncol Adv. 3(vdab084)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Yamamoto J, Takahashi M, Idei M, Nakano Y,

Soejima Y, Akiba D, Kitagawa T, Ueta K, Miyaoka R and Nishizawa S:

Clinical features and surgical management of intracranial

meningiomas in the elderly. Oncol Lett. 14:909–917. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Yang CC, Tsai CC, Chen SJ, Chiang MF, Lin

JF, Hu CK, Chan YK, Lin HY and Cheng SY: Factors associated with

recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical resection: A

retrospective single-center study. Int Journal of Gerontol.

12:57–61. 2018.

|

|

7

|

Hwang WL, Marciscano AE, Niemierko A, Kim

DW, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Curry WT, Barker FG II, Martuza RL,

Loeffler JS, Oh KS, et al: Imaging and extent of surgical resection

predict risk of meningioma recurrence better than WHO

histopathological grade. Neuro Oncol. 18:863–872. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Varki A: Biological roles of glycans.

Glycobiology. 27:3–49. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Dobie C and Skropeta D: Insights into the

role of sialylation in cancer progression and metastasis. Br J

Cancer. 124:76–90. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhou X, Yang G and Guan F: Biological

functions and analytical strategies of sialic acids in tumor.

Cells. 9(273)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Christie DR, Shaikh FM, Lucas JA IV, Lucas

JA III and Bellis SL: ST6Gal-I expression in ovarian cancer cells

promotes an invasive phenotype by altering integrin glycosylation

and function. J Ovarian Res. 1(3)2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhang X, Dou P, Akhtar ML, Liu F, Hu X,

Yang L, Yang D, Zhang X, Li Y, Qiao S, et al: NEU4 inhibits

motility of HCC cells by cleaving sialic acids on CD44. Oncogene.

40:5427–5440. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Cazet A, Julien S, Bobowski M,

Krzewinski-Recchi MA, Harduin-Lepers A, Groux-Degroote S and

Delannoy P: Consequences of the expression of sialylated antigens

in breast cancer. Carbohydr Res. 345:1377–1383. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Talabnin C, Trasaktaweesakul T,

Jaturutthaweechot P, Asavaritikrai P, Kongnawakun D, Silsirivanit

A, Araki N and Talabnin K: Altered O-linked glycosylation in benign

and malignant meningiomas. PeerJ. 12(e16785)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Naradun N, Talabnin K, Ayuttha KIN and

Talabnin C: Piperlongumine and bortezomib synergically inhibit

cholangiocarcinoma via ER stress-induced cell death. Naunyn

Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 396:109–120. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Macauley MS, Crocker PR and Paulson JC:

Siglec-mediated regulation of immune cell function in disease. Nat

Rev Immunol. 14:653–666. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Swindall AF and Bellis SL: Sialylation of

the Fas death receptor by ST6Gal-I provides protection against

Fas-mediated apoptosis in colon carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem.

286:22982–22990. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Chiodelli P, Urbinati C, Paiardi G, Monti

E and Rusnati M: Sialic acid as a target for the development of

novel antiangiogenic strategies. Future Med Chem. 10:2835–2854.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zou X, Lu J, Deng Y, Liu Q, Yan X, Cui Y,

Xiao X, Fang M, Yang F, Sawaki H, et al: ST6GAL1 inhibits

metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via modulating sialylation

of MCAM on cell surface. Oncogene. 42:516–529. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Park DD, Xu G, Park SS, Haigh NE, Phoomak

C, Wongkham S, Maverakis E and Lebrilla CB: Combined analysis of

secreted proteins and glycosylation identifies prognostic features

in cholangiocarcinoma. J Cell Physiol. 239(e31147)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Al Saoud R, Hamrouni A, Idris A, Mousa WK

and Abu Izneid T: Recent advances in the development of

sialyltransferase inhibitors to control cancer metastasis: A

comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother.

165(115091)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Cui HX, Wang H, Wang Y, Song J, Tian H,

Xia C and Shen Y: ST3Gal III modulates breast cancer cell adhesion

and invasion by altering the expression of invasion-related

molecules. Oncol Rep. 36:3317–3324. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Lu J, Isaji T, Im S, Fukuda T, Hashii N,

Takakura D, Kawasaki N and Gu J: β-Galactoside α2,

6-sialyltranferase 1 promotes transforming growth factor-β-mediated

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 289:34627–34641.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhou L, Zhang S, Zou X, Lu J, Yang X, Xu

Z, Shan A, Jia W, Liu F, Yan X, et al: The β-galactoside

α2,6-sialyltranferase 1 (ST6GAL1) inhibits the colorectal cancer

metastasis by stabilizing intercellular adhesion molecule-1 via

sialylation. Cancer Manag Res. 11:6185–6199. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Jung YR, Park JJ, Jin YB, Cao YJ, Park MJ,

Kim EJ and Lee M: Silencing of ST6Gal I enhances colorectal cancer

metastasis by downregulating KAI1 via exosome-mediated exportation

and thereby rescues integrin signaling. Carcinogenesis.

37:1089–1097. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wick W, Platten M and Weller M: Glioma

cell invasion: Regulation of metalloproteinase activity by

TGF-beta. J Neurooncol. 53:177–185. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Shibue T, Brooks MW and Weinberg RA: An

integrin-linked machinery of cytoskeletal regulation that enables

experimental tumor initiation and metastatic colonization. Cancer

Cell. 24:481–498. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Augoff K, Hryniewicz-Jankowska A, Tabola R

and Stach K: MMP9: A tough target for targeted therapy for cancer.

Cancers (Basel). 14(1847)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Hou S, Wang J, Li W, Hao X and Hang Q:

Roles of integrins in gastrointestinal cancer metastasis. Front Mol

Biosci. 8(708779)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|