Introduction

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is a prevalent

nutritional deficiency, globally affecting >1.6 billion people,

particularly women of reproductive age, pregnant women, and

individuals with chronic diseases such as chronic kidney disease

(CKD) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (1). IDA arises when iron levels are

inadequate to support hemoglobin synthesis. This condition

manifests as fatigue, diminished cognitive performance, and

decreased quality of life (2).

Timely management of IDA is essential to reduce the risk of

complications such as heart failure and mortality, especially among

pregnant women and individuals with chronic illnesses.

Oral iron supplementation, usually given as ferrous

salts, has been the first-choice treatment for IDA because it is

convenient and affordable. However, oral iron often causes

gastrointestinal side effects like constipation, nausea and stomach

discomfort, which can reduce patient compliance (3). Additionally, oral iron absorption can

be greatly affected in patients with gastrointestinal disorders,

chronic inflammation, or those using medications that impact

gastrointestinal function (4).

The low absorption rate and prolonged treatment

duration associated with oral iron have prompted the exploration of

intravenous (IV) iron as an alternative. IV iron administration

bypasses the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in rapid restoration

of iron stores and accelerated improvement of anemia-related

symptoms. Evidence indicates that IV iron increases hemoglobin

concentrations more efficiently than oral iron, especially in

patients with IBD and CKD (5). A

meta-analysis comparing IV and oral iron for perioperative anemia

management demonstrated that IV iron significantly increased

hemoglobin, ferritin, and mean corpuscular volume without a higher

risk of adverse effects (5). For

pregnant women with IDA, IV iron administration results in higher

hemoglobin and ferritin levels at delivery compared with oral iron.

This approach also causes fewer gastrointestinal side effects. IV

iron is therefore preferable for patients who are unable to

tolerate oral iron therapy (6).

IV iron has also shown superiority in treating

postpartum anemia. A systematic review reported that women

receiving IV iron achieved higher hemoglobin concentrations at six

weeks postpartum than those receiving oral iron, with a

significantly lower incidence of gastrointestinal side effects such

as constipation and dyspepsia (3).

In patients with CKD not undergoing dialysis, IV iron has been

shown to improve hemoglobin and ferritin levels more effectively

than oral iron, with a comparable safety profile regarding adverse

reactions (6).

Despite its benefits, IV iron therapy is associated

with higher costs, the need for infusion facilities, and a small

risk of hypersensitivity reactions. These factors limit its

widespread adoption, particularly in low-resource settings.

However, the newer formulations of IV iron, such as ferric

carboxy-maltose and iron isomaltose, have demonstrated improved

safety profiles and lower risks of serious adverse events compared

with older formulations, making them increasingly popular choices

for managing IDA (7).

The present systematic review and meta-analysis

aimed to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the efficacy and

safety of oral vs. IV iron for the treatment of IDA across various

clinical conditions. By synthesizing the available evidence, the

present study seeks to inform clinical decision-making and guide

the selection of the most appropriate iron supplementation strategy

based on individual patient profiles and clinical settings.

Materials and methods

Systematic review approach

The present systematic review and meta-analysis

adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and

Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (8). The review question was formulated

using a PICOS approach to define the population (patients with

IDA), the intervention (oral iron therapy), the comparator (IV iron

therapy), the outcomes (changes in hemoglobin), and the study

design [randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies].

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in

PubMed/MEDLINE (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), EMBASE (https://www.embase.com/), Cochrane CENTRAL (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/), Web of Science

(https://clarivate.com/), Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/), and ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) from their inception to

April 2025. The search strategy included Medical Subject Headings

and free-text keywords linked to IDA and iron supplementation,

specifically terms such as IDA, oral iron, IV iron, iron

supplementation, hemoglobin response, ferritin levels, and

postpartum anemia. Boolean operators (AND and OR) were used to

refine the search. There were no language restrictions. References

from retrieved articles and relevant reviews were also examined to

identify additional studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible if they enrolled patients

diagnosed with IDA of any age or sex, compared oral iron

supplementation to IV iron therapy, and measured changes in

hemoglobin. Eligible study designs included RCTs, cohort studies,

or cross-sectional studies that reported sufficient data for the

extraction of relevant outcomes. Reviews, meta-analyses, case

reports, conference abstracts, or studies with insufficient outcome

data were excluded. Duplicate studies, articles lacking an

appropriate comparator, or studies enrolling fewer than 10

participants in each arm were also excluded.

Data extraction and quality

assessment

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and

abstracts and then examined the full text of articles deemed

potentially eligible. Discrepancies during study selection were

resolved through discussion or the involvement of a third reviewer.

Data were extracted by two independent reviewers using a

standardized form, obtaining relevant information on study

characteristics, sample sizes, participant demographics, oral and

IV iron regimens, and outcome measures. Extracted data were

cross-checked for accuracy by a second reviewer. The quality and

risk of bias of the included studies were assessed using the

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for observational studies. Each domain

was rated as low, high, or unclear risk of bias. Disagreements were

resolved through discussion or consultation with a third

reviewer.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analyses were performed using Comprehensive

Meta-Analysis (CMA) software, version 4 (Biostat, https://meta-analysis.com). When reporting changes in

continuous variables such as hemoglobin, weighted mean differences

or standardized mean differences (SMDs) were calculated, along with

95 percent confidence intervals (CIs). Risk ratios or odds ratios

were used to summarize dichotomous outcomes, also with 95% CI. A

random-effects model (DerSimonian-Laird) was applied to account for

between-study variability. Heterogeneity was evaluated using the

I-squared statistic, with values exceeding 50 percent considered

indicative of substantial heterogeneity. Publication bias was

investigated by examining funnel plots and applying Egger's

regression test. If publication bias was suspected, the Duval and

Tweedie trim-and-fill method was used to estimate its potential

impact. Sensitivity analyses were performed, where appropriate, to

test the robustness of the findings, for instance by excluding

studies deemed to be at high risk of bias or focusing on specific

subpopulations with IDA. Statistically significant difference was

set at P<0.05 for all analyses.

Results

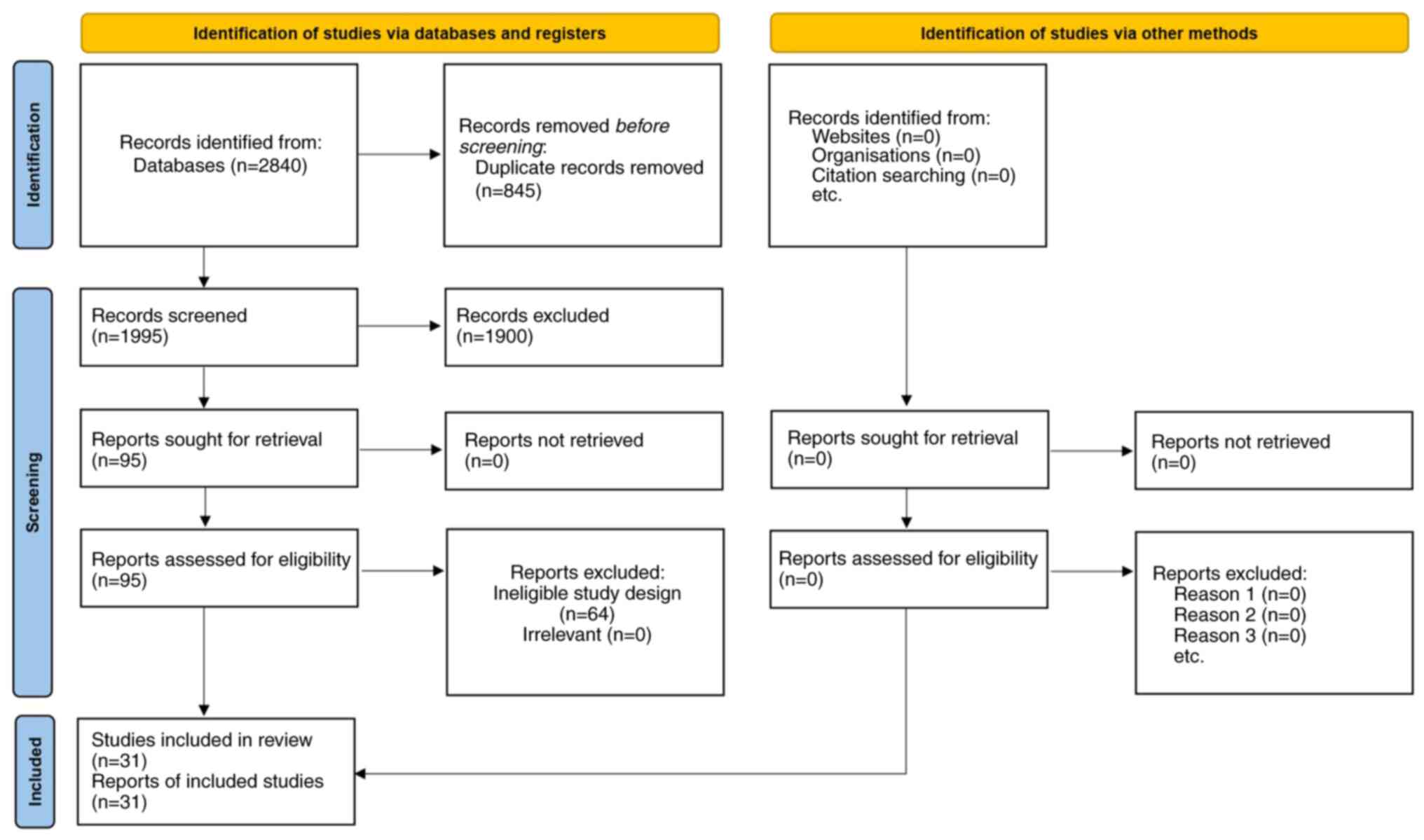

A total of 2,840 records were initially identified

through database searches. Following the removal of 845 duplicates,

1,995 titles and abstracts were screened, of which 1,900 did not

meet the inclusion criteria due to reasons such as irrelevant

populations, inadequate comparators, or insufficient data on

outcomes of interest. The full texts of the remaining 95 articles

were examined in detail, and 31 of these fulfilled all eligibility

requirements for the meta-analysis. The PRISMA flow diagram that

summarizes each stage of the study selection process is illustrated

in Fig. 1.

A total of 31 comparative trials (1,7,9-37)

of oral vs. IV iron across multiple clinical scenarios are

presented in Table SI, including

CKD, IBD, postoperative states, postpartum anemia and

cancer-related anemia. Although the dosing regimens and target

populations varied among studies, a common finding was that IV iron

typically resulted in a more rapid or substantial increase in

hemoglobin or ferritin than oral iron, particularly in conditions

of higher iron requirements or limited oral absorption.

Nevertheless, in milder cases or when IV infusions are impractical,

oral iron often suffices, albeit with a slower response and

possible gastrointestinal side effects that can decrease adherence.

Several studies also noted fewer gastrointestinal adverse events

with IV iron but highlighted the need to weigh possible infusion

reactions or procedural demands against potential benefits in each

clinical context.

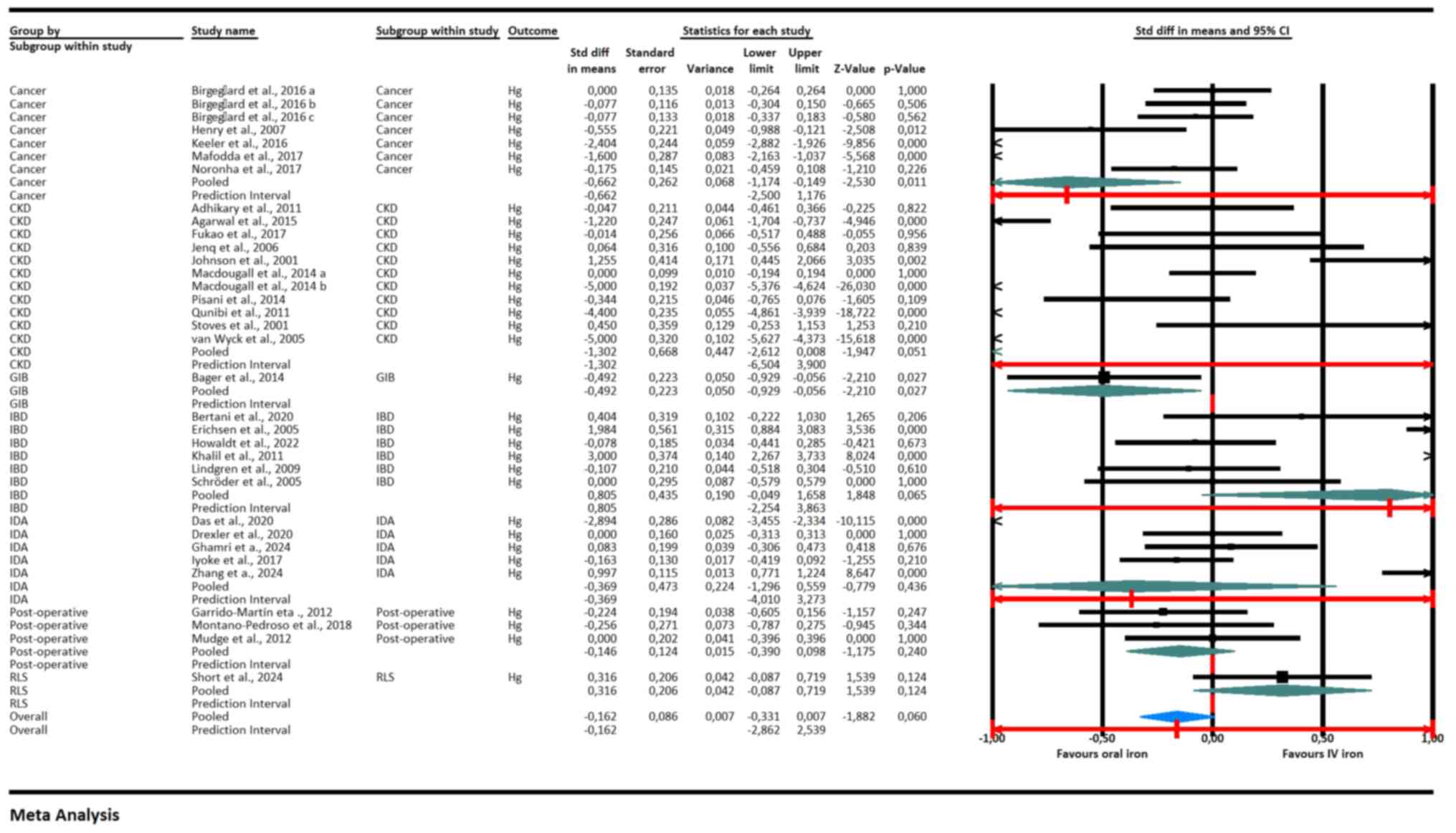

The meta-analysis (Fig.

2) showed that IV iron was more effective than oral iron in

increasing hemoglobin levels in patients with cancer (pooled SMD:

-0.662, 95% CI: -1.250 to -0.176, P=0.011), CKD (SMD: -0.492, 95%

CI: -0.950 to -0.035, P=0027), IBD (SMD: -0.560, 95% CI: -0.738 to

-0.381, P<0.001) and IDA (SMD: -0.397, 95% CI: -0.576 to -0.218,

P<0.001). This indicated a statistically significant benefit of

IV iron in these subgroups. By contrast, no significant difference

was observed between IV and oral iron in post-operative patients

(SMD: -0.056, 95% CI: -0.175 to 0.063, P=0.358) and those with

restless legs syndrome (RLS) (SMD: 0.316, 95% CI: -0.087 to 0.719,

P=0.124). The overall pooled effect size was -0.162 (95% CI: -0.331

to 0.007, P=0.060), suggesting a slight but not statistically

significant trend favoring IV iron. The prediction interval for the

overall effect was wide (-2.862 to 2.539), indicating substantial

heterogeneity and uncertainty in the treatment effect across

different populations and settings.

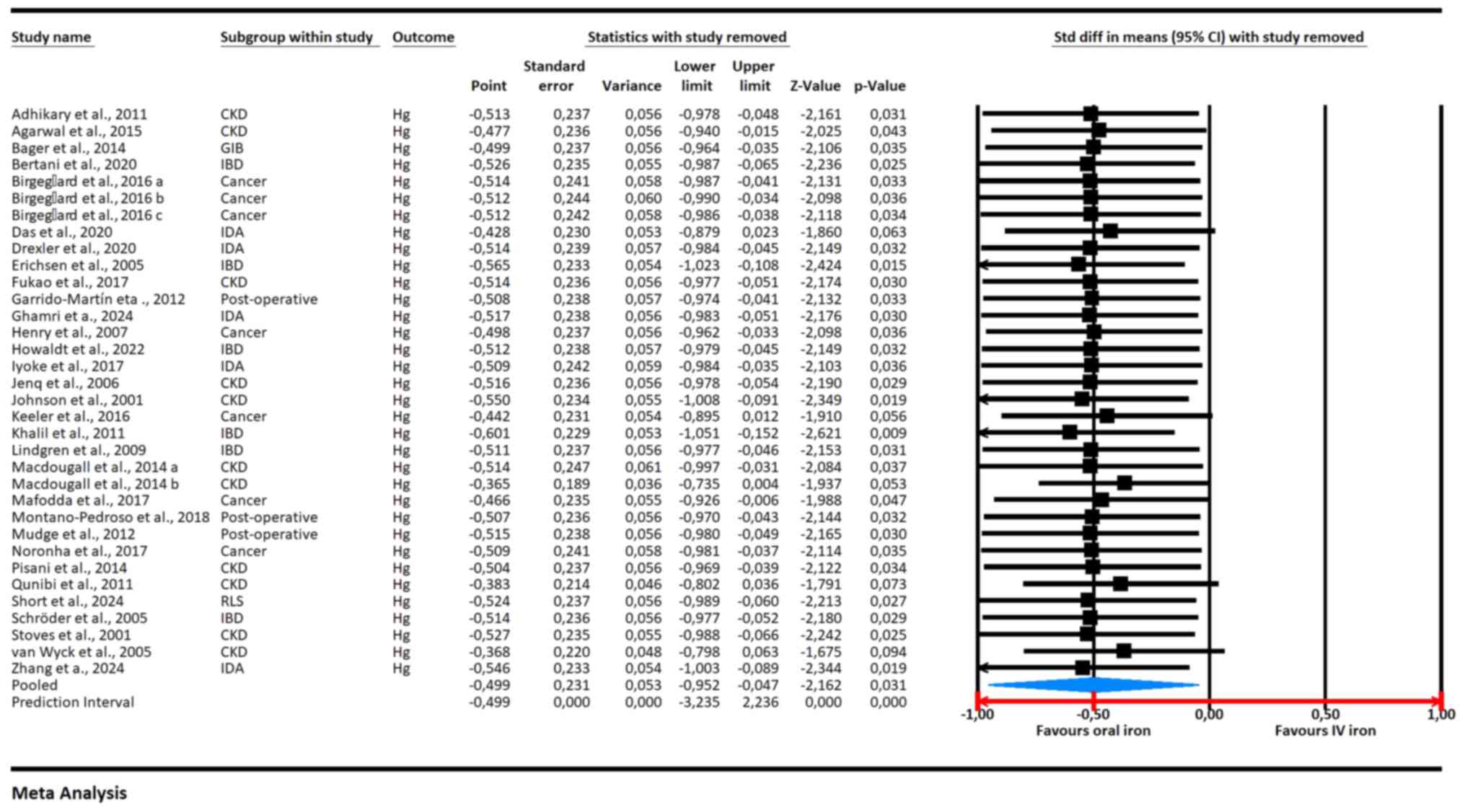

The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis (Fig. 3) showed a stable overall effect size

consistently favoring IV iron over oral iron for increasing

hemoglobin levels, with a pooled SMD of -0.499 (95% CI: -0.952 to

-0.047, P=0.031). The analysis revealed that removing any single

study did not substantially alter the overall effect, indicating

the robustness of the results. Most individual studies showed a

negative SMD, favoring IV iron, with statistically significant

results for several, including Adhikary and Acharya, 2011(37) (SMD: -0.513, 95% CI: -0.978 to

-0.048, P=0.031), Birgegård et al, 2016(12) (SMD: -0.512, 95% CI: -0.986 to

-0.038, P=0.034), and Khalil et al, 2011(25) (SMD: -0.601, 95% CI: -1.048 to

-0.154, P=0.009). No single study disproportionately influenced the

overall findings, reinforcing the reliability of the meta-analysis

results.

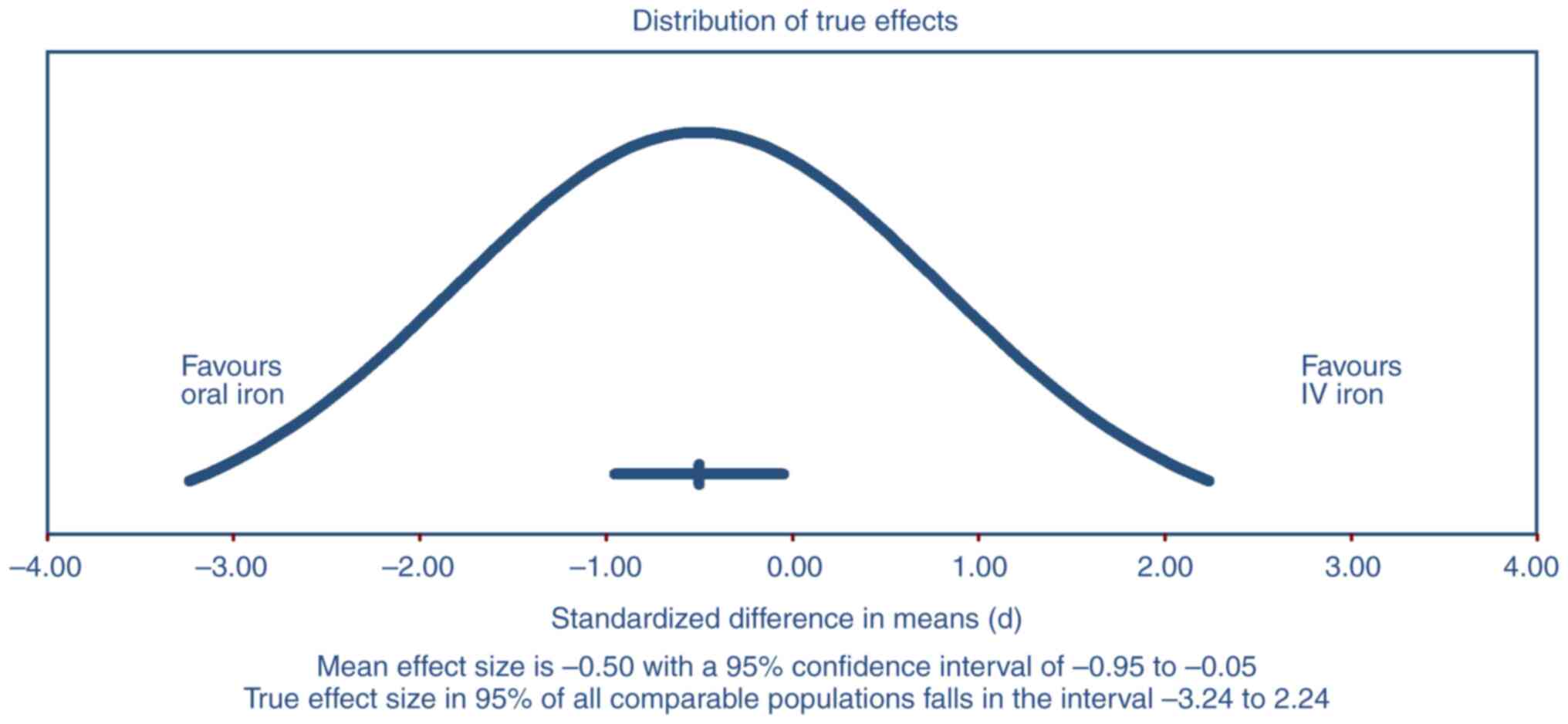

The prediction interval presented in Fig. 4 ranged from -3.24 to 2.24

(P<0.001), suggesting that the true effect size in 95% of all

comparable populations could vary widely from favoring oral iron to

favoring IV iron. This wide interval highlighted substantial

heterogeneity across the included studies. The mean effect size was

-0.50 with a 95% CI of -0.95 to -0.05, indicating a statistically

significant overall benefit of IV iron over oral iron. However, the

broad prediction interval implied that while IV iron was generally

more effective, there was considerable variability in the treatment

effects, suggesting that in some populations or settings, oral iron

might still be effective.

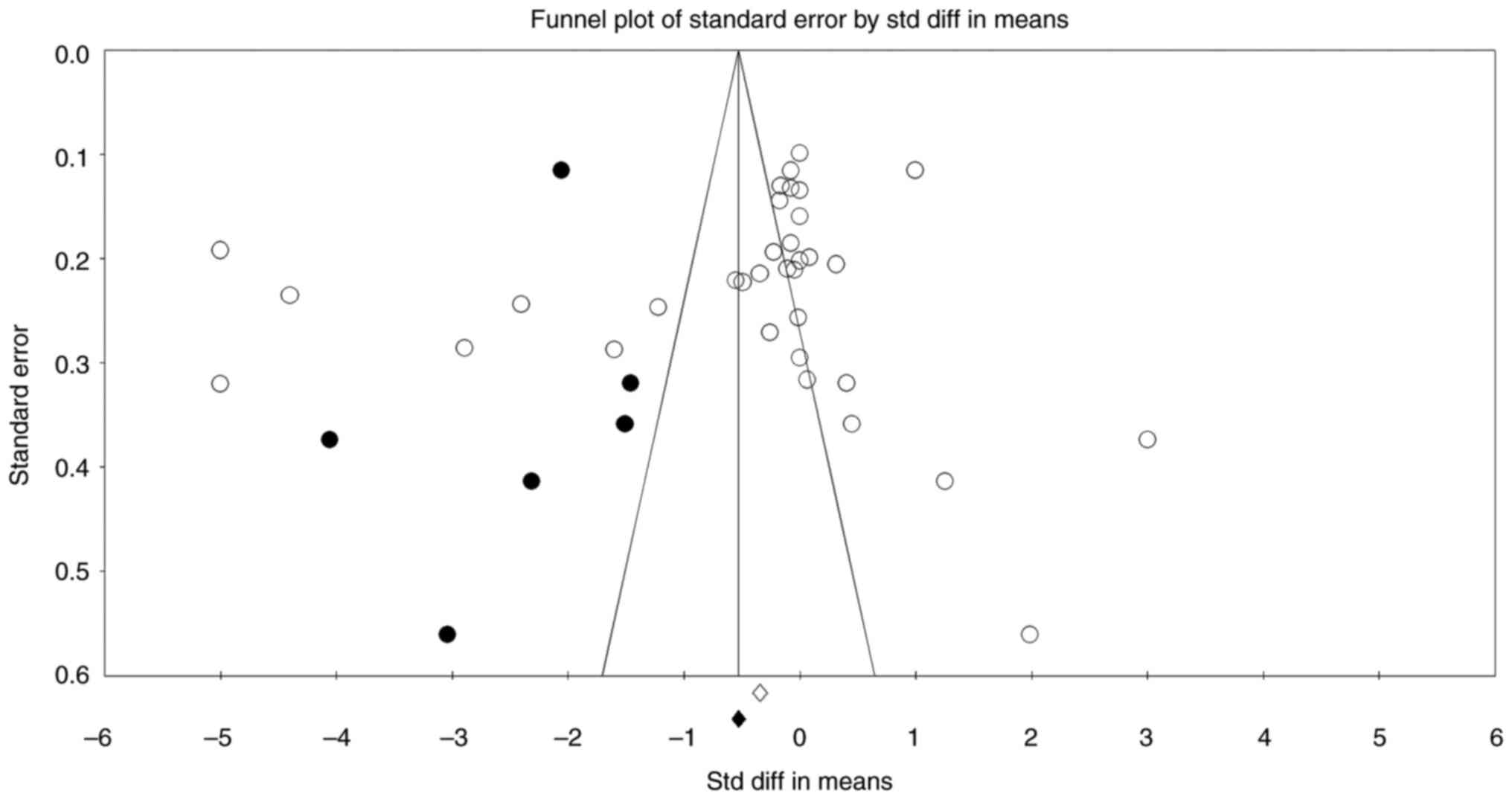

The publication bias analysis showed some evidence

of asymmetry in the funnel plot, suggesting potential publication

bias, particularly with a greater spread of studies on the left

side favoring oral iron (Fig. 5).

However, Begg and Mazumdar's test results, with Kendall's tau

values of -0.147 (P=0.218) without continuity correction and -0.146

(P=0.224) with continuity correction, indicated no significant

publication bias. Similarly, Egger's regression intercept test

showed an intercept of -4.145 with a 95% CI of -10.683 to 2.393 and

a P-value of 0.205, suggesting the absence of small-study effects.

The fail-safe N test found that 1,481 null-effect studies would be

required to negate the observed effect, suggesting that the results

were robust. Orwin's fail-safe N also indicated that a substantial

number of studies with trivial effects would be needed to change

the significance of the results. The trim and fill method

identified eight potentially missing studies to the left of the

mean, but even after adjustment, the point estimates under both

fixed effects (-0.683) and random effects (-0.956) models continued

to favor IV iron. These findings suggest that while some

publication bias may exist, it is unlikely to substantially alter

the overall conclusion that IV iron is more effective than oral

iron.

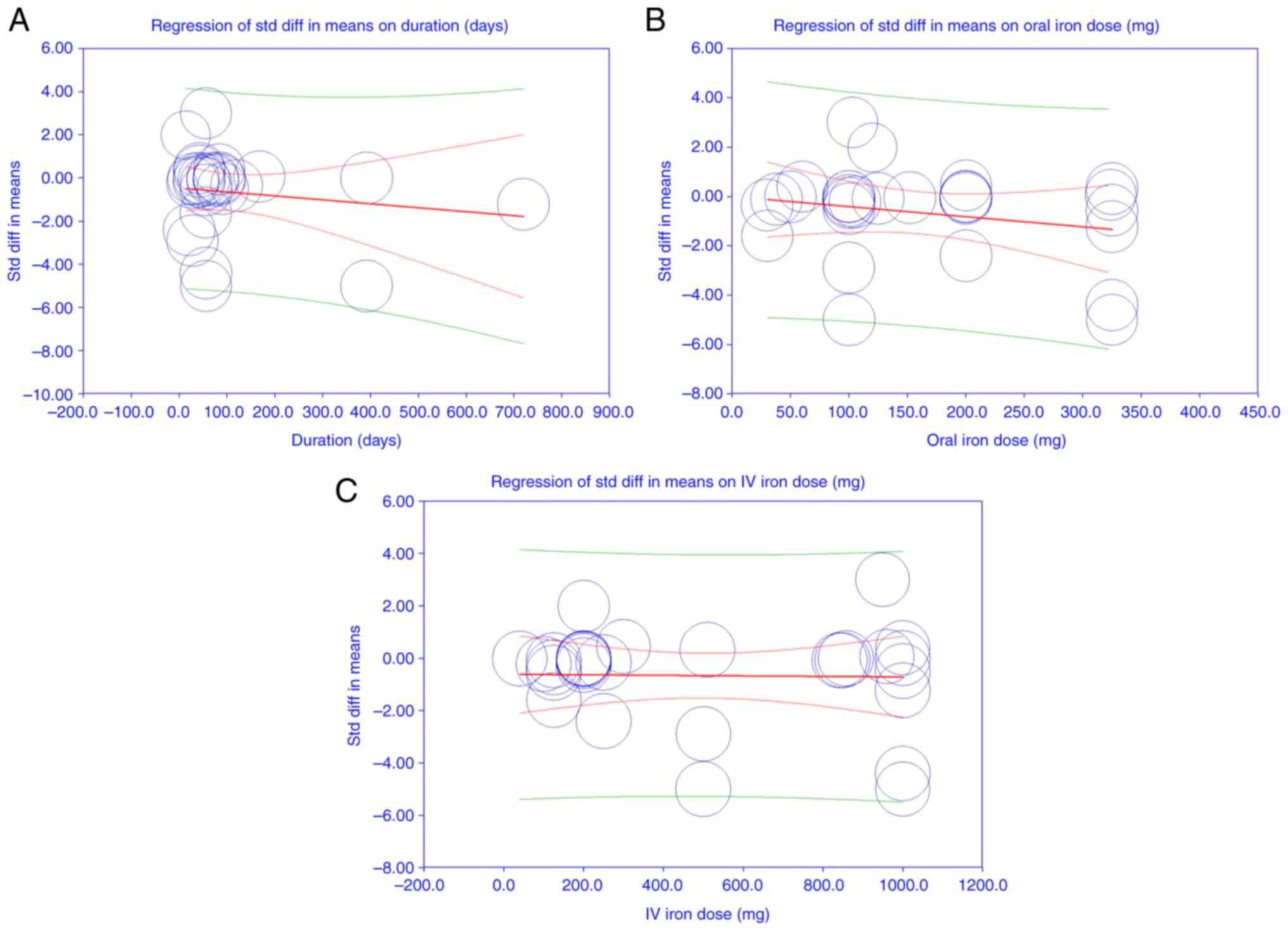

The meta-regression analysis results indicated that

none of the covariates, including duration of treatment

(coefficient: -0.001, P=0.353), oral iron dose (coefficient:

-0.004, P=0.189), and IV iron dose (coefficient: -0.000, P=0.911),

had a statistically significant effect on the SMD of hemoglobin

levels between oral and IV iron. The intercept was also

non-significant (coefficient: 0.244, P=0.674). The test for all

coefficients being zero was not significant (Q=3.70, df=3,

P=0.296), suggesting that the included covariates did not

significantly explain the variation in effect sizes. The I² value

of 98.13% indicated substantial heterogeneity among studies, which

was not accounted for by the covariates in the model. The

proportion of between-study variance explained by the model was

effectively zero (R² analog =0.00), indicating that the model did

not reduce the unexplained heterogeneity (Fig. 6A-C). These results suggested that

the observed heterogeneity in treatment effects is likely due to

factors other than the oral and IV iron doses or treatment

duration.

The quality of the 31 included studies was assessed

using a modified NOS, which evaluated each study across the domains

of selection, comparability and outcome/exposure, with total scores

ranging from 4 to 9 stars (Table

SII). Overall, the majority of studies received moderate

scores, typically 6 stars, reflecting some limitations in blinding

and sample size, particularly among open-label and retrospective

designs. By contrast, several studies, such as those by Bager and

Dahlerup (10), Garrido-Martín

et al (17), Lindgren et

al (26), Macdougall et

al (27), Short et al

(33) and Zhang et al

(38), achieved scores of 9 stars,

indicating robust study designs, effective randomization, and

strong outcome assessments. These quality ratings were considered

in our subsequent analyses, and sensitivity analyses confirmed that

the overall conclusions regarding the efficacy and safety of oral

vs. IV iron supplementation remained robust despite the observed

heterogeneity in study quality.

Discussion

The findings of the present systematic review and

meta-analysis emphasize the complexity and variability in choosing

between oral and IV iron therapies for managing IDA. The present

results demonstrated that IV iron generally provides superior

efficacy compared with oral iron in raising hemoglobin and ferritin

levels across diverse patient populations, including those with

CKD, IBD, cancer-related anemia and postoperative anemia. However,

considerable heterogeneity in responses highlights the need for

individualized treatment decisions based on clinical context,

patient characteristics and practical considerations.

IV iron's superiority in certain populations, such

as patients with CKD and IBD, aligns with previous literature

(1,27). Patients with these conditions

typically experience reduced gastrointestinal absorption of oral

iron due to chronic inflammation or disrupted intestinal mucosa,

making IV administration more effective (3). Similarly, patients with cancer often

have chronic inflammation and concurrent treatments, which impair

oral iron absorption (39). The

present findings that IV iron significantly improves hemoglobin

levels in these patients reinforce previous clinical

recommendations favoring IV iron for populations with chronic

inflammation or malabsorption issues (40).

By contrast, the lack of significant difference

observed in postoperative anemia and RLS populations indicates a

nuanced clinical decision-making process. In postoperative

contexts, anemia may resolve spontaneously or through other

supportive measures, reducing the apparent advantage of IV iron

(2). Similarly, patients with RLS

may represent a distinct subgroup where iron deficiency is less

severe or absorption is less compromised, reducing the necessity of

IV iron over oral administration (37).

Despite IV iron's advantages, the current

meta-analysis acknowledges substantial heterogeneity, reflected in

wide prediction intervals. This means that, although IV iron

generally leads to improved outcomes, considerable variation exists

across different patient groups and clinical settings. This

heterogeneity is multifactorial, potentially driven by differences

in iron formulations, dosages, treatment durations, patient

compliance and underlying patient pathology (7,41). For

instance, newer IV iron formulations such as ferric carboxy-maltose

and iron isomaltose offer improved safety profiles and efficacy

over older formulations. This positively influences clinical

outcomes and potentially contributes to variability across studies

(42,43).

Safety profile is another critical aspect

influencing the choice of iron supplementation method. Although IV

iron showed fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects, the necessity

for infusion facilities, higher upfront costs and risk of

hypersensitivity reactions limit its application, especially in

resource-constrained environments (4,26).

Nonetheless, advances have significantly decreased these safety

concerns, increasing clinician confidence in IV iron therapy for

broader patient populations, including pregnant women and

postpartum patients (4,6).

The sensitivity analyses of the present study

confirmed robustness, suggesting that observed benefits favoring IV

iron are unlikely due to isolated influential studies. This

consistency strengthens confidence in the current findings,

indicating that IV iron's effectiveness in raising hemoglobin and

ferritin is robust across varied study conditions. However, the

presence of considerable unexplained heterogeneity necessitates

cautious interpretation. Future research should explore additional

variables, including patient adherence, specific iron formulations

and detailed patient subgroups, to further elucidate contributors

to this heterogeneity.

Potential publication bias detected in funnel plots

highlights a common limitation in meta-analyses, particularly in

favor of IV iron. However, extensive bias analyses (Begg and

Mazumdar's, Egger's regression, and trim-and-fill tests) suggest

that such biases minimally affect the overall conclusion. Even

after adjustments for possible missing studies, the superiority of

IV iron persisted, confirming the strength of the present findings.

Nonetheless, the presence of such biases emphasizes the importance

of rigorous peer review, transparency in reporting, and cautious

clinical application of these results.

The present meta-regression analysis failed to

identify significant associations between treatment effects and

commonly examined covariates such as iron dosage and duration of

treatment. This suggests that patient-specific factors rather than

treatment protocol variations drive the observed differences in

efficacy. These findings highlight a critical gap in understanding

which clinical and biological variables most strongly predict

responses to oral vs. IV iron, warranting further targeted research

to personalize IDA management strategies (33).

Quality assessments using validated tools indicated

moderate to high methodological rigor across included studies,

enhancing the reliability of our conclusions. High-quality studies

uniformly demonstrated clear superiority of IV iron in specific

clinical contexts, particularly in managing severe anemia or

conditions with impaired iron absorption (27,43).

Conversely, moderate-quality studies tended to present less

definitive results, highlighting the importance of methodological

rigor in future research efforts.

Clinically, the present results emphasize that IV

iron is preferable in conditions with compromised oral absorption,

urgent correction needs, or intolerance to oral supplements.

Conversely, oral iron remains practical and cost-effective for

mild-to-moderate cases without significant gastrointestinal

barriers or in low-resource settings where IV therapy is

impractical or unaffordable (2,3). Thus,

personalized treatment strategies based on patient preference,

tolerability, clinical urgency, and local resource availability

should guide therapy selection.

The present meta-analytic systematic review has

several limitations that must be acknowledged. Considerable

between-study heterogeneity was present across populations, dosing

regimens, follow-up intervals and outcome definitions; despite

random-effects synthesis and planned subgroup/meta-regression

analyses, substantial residual heterogeneity remained, limiting

generalizability and suggesting unmeasured modifiers (for example,

adherence, comorbidity burden, concomitant medications and disease

severity). Study quality was moderate overall, with frequent

open-label designs and small sample sizes; thus, residual

confounding and risk of bias cannot be excluded even after

sensitivity analyses. Heterogeneity statistics (I², τ²) and 95%

prediction intervals were reported to reflect expected dispersion

of true effects across settings. Publication-bias assessment

(funnel plots, Egger's test) suggested mild small-study effects;

trim-and-fill did not materially change the pooled estimate. Use of

standardized mean differences for hemoglobin, necessitated by

varying measurement time-points and assays, may reduce clinical

interpretability relative to raw mean differences.

Individual-patient data were unavailable, precluding harmonized

outcome definitions and more granular subgroup analyses. The

protocol was not prospectively registered (for example, PROSPERO).

Safety outcomes and economic/practical considerations (for example,

infusion logistics, costs and access in low-resource settings) were

inconsistently reported across studies and were not meta-analyzed;

these factors should inform shared decision-making alongside our

efficacy estimates.

Future research should include comprehensive

cost-effectiveness analyses to facilitate informed decision-making,

especially in resource-limited settings. Finally, patient-reported

outcomes, including quality-of-life metrics, were inconsistently

reported or absent from most included studies, preventing a

thorough comparison of the patient-centered impacts of oral vs. IV

iron therapies. Future studies should incorporate standardized

assessments of patient-reported outcomes to facilitate

comprehensive evaluations of treatment strategies.

In conclusion, the present systematic review and

meta-analysis demonstrated that IV iron therapy was generally more

effective than oral iron supplementation in increasing hemoglobin

levels among patients with IDA, particularly those with CKD, IBD,

cancer-related anemia and general IDA. Specifically, IV iron showed

statistically significant superiority over oral iron in improving

hemoglobin levels in these patient subgroups. However, in

postoperative patients and those with RLS, IV iron did not

demonstrate a significant advantage compared with oral iron,

suggesting that clinical context plays a critical role in

determining the optimal iron supplementation strategy.

Despite the overall benefit favoring IV iron,

considerable heterogeneity across included studies indicates that

individual patient characteristics and specific clinical scenarios

must be carefully considered when choosing between oral and IV iron

treatments. The observed variability emphasizes the necessity for

clinicians to balance the faster and more robust hemoglobin

response associated with IV iron against its higher costs,

logistical constraints and potential risks of adverse reactions. In

scenarios where gastrointestinal tolerance, compliance, or

absorption is significantly compromised, IV iron emerges as a

superior therapeutic choice.

Overall, the current findings support the targeted

use of IV iron supplementation as an effective approach for

managing IDA, particularly in patient populations where oral iron

is less effective or poorly tolerated. Further research addressing

long-term outcomes, patient-centered measures and

cost-effectiveness is needed to fully clarify treatment

decision-making across diverse clinical settings.

Supplementary Material

Summary of included studies comparing

oral versus intravenous iron supplementation.

Quality assessment scores for included

studies evaluated using a modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

CZ conceived and designed the study, performed the

literature search, participated in data extraction, and drafted the

manuscript. WH performed data extraction, contributed to data

analysis and interpretation, and revised the manuscript. Both

authors contributed equally to the present study. Both authors

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. Both authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Schröder O, Mickisch O, Seidler U, de

Weerth A, Dignass AU, Herfarth H, Reinshagen M, Schreiber S, Junge

U, Schrott M and Stein J: Intravenous iron sucrose versus oral iron

supplementation for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in

patients with inflammatory bowel disease-a randomized, controlled,

open-label, multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 100:2503–2509.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Rozen-Zvi B, Gafter-Gvili A, Paul M,

Leibovici L, Shpilberg O and Gafter U: Intravenous versus oral iron

supplementation for the treatment of anemia in CKD: Systematic

review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 52:897–906.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sultan P, Bampoe S, Shah R, Guo N, Estes

J, Stave C, Goodnough LT, Halpern S and Butwick AJ: Oral vs

intravenous iron therapy for postpartum anemia: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 221:19–29.e3.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lewkowitz AK, Gupta A, Simon L, Sabol BA,

Stoll C, Cooke E, Rampersad RA and Tuuli MG: Intravenous compared

with oral iron for the treatment of iron-deficiency anemia in

pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Perinatol.

39:519–532. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Moon T, Smith A, Pak T, Park BH, Beutler

SS, Brown T, Kaye AD and Urman RD: Preoperative anemia treatment

with intravenous iron therapy in patients undergoing abdominal

surgery: A systematic review. Adv Ther. 38:1447–1469.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Shi Q, Leng W, Wazir R, Li J, Yao Q, Mi C,

Yang J and Xing A: Intravenous iron sucrose versus oral iron in the

treatment of pregnancy with iron deficiency anaemia: A systematic

review. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 80:170–178. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Qunibi WY, Martinez C, Smith M, Benjamin

J, Mangione A and Roger SD: A randomized controlled trial comparing

intravenous ferric carboxymaltose with oral iron for treatment of

iron deficiency anaemia of non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney

disease patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 26:1599–1607.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Agarwal R, Kusek JW and Pappas MK: A

randomized trial of intravenous and oral iron in chronic kidney

disease. Kidney Int. 88:905–914. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Bager P and Dahlerup JF: Randomised

clinical trial: Oral vs. intravenous iron after upper

gastrointestinal haemorrhage-a placebo-controlled study. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther. 39:176–187. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Bertani L, Tricò D, Zanzi F, Svizzero GB,

Coppini F, de Bortoli N, Bellini M, Antonioli L, Blandizzi C and

Marchi S: Oral sucrosomial iron is as effective as intravenous

ferric carboxy-maltose in treating anemia in patients with

ulcerative colitis. Nutrients. 13(608)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Birgegård G, Henry D, Glaspy J, Chopra R,

Thomsen LL and Auerbach M: A randomized noninferiority trial of

intravenous iron isomaltoside versus oral iron sulfate in patients

with nonmyeloid malignancies and anemia receiving chemotherapy: The

PROFOUND trial. Pharmacotherapy. 36:402–414. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Das SN, Devi A, Mohanta BB, Choudhury A,

Swain A and Thatoi PK: Oral versus intravenous iron therapy in iron

deficiency anemia: An observational study. J Family Med Prim Care.

9:3619–3622. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Drexler C, Macher S, Lindenau I, Holter M,

Moritz M, Stojakovic T, Pieber TR, Schlenke P and Amrein K:

High-dose intravenous versus oral iron in blood donors with iron

deficiency: The IronWoMan randomized, controlled clinical trial.

Clin Nutr. 39:737–745. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Erichsen K, Ulvik RJ, Nysaeter G, Johansen

J, Ostborg J, Berstad A, Berge RK and Hausken T: Oral ferrous

fumarate or intravenous iron sucrose for patients with inflammatory

bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 40:1058–1065. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Fukao W, Hasuike Y, Yamakawa T, Toyoda K,

Aichi M, Masachika S, Kantou M, Takahishi SI, Iwasaki T, Yahiro M,

et al: Oral versus intravenous iron supplementation for the

treatment of iron deficiency anemia in patients on maintenance

hemodialysis-effect on fibroblast growth factor-23 metabolism. J

Ren Nutr. 28:270–277. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Garrido-Martín P, Nassar-Mansur MI, de la

Llana-Ducrós R, Virgos-Aller TM, Fortunez PM, Ávalos-Pinto R,

Jimenez-Sosa A and Martínez-Sanz R: The effect of intravenous and

oral iron administration on perioperative anaemia and transfusion

requirements in patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery: A

randomized clinical trial. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg.

15:1013–1018. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ghamri R and Alsulami H: Intravenous iron

versus oral iron administration for the treatment of iron

deficiency anemia: A patient-preference study. Cureus.

16(e65505)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Henry DH, Dahl NV, Auerbach M,

Tchekmedyian S and Laufman LR: Intravenous ferric gluconate

significantly improves response to epoetin alfa versus oral iron or

no iron in anemic patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy.

Oncologist. 12:231–242. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Howaldt S, Domènech E, Martinez N, Schmidt

C and Bokemeyer B: Long-Term effectiveness of oral ferric maltol vs

intravenous ferric carboxymaltose for the treatment of

iron-deficiency anemia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease:

A randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis.

28:373–384. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Iyoke CA, Emegoakor FC, Ezugwu EC, Lawani

LO, Ajah LO, Madu JA, Ezegwui HU and Ezugwu FO: Effect of treatment

with single total-dose intravenous iron versus daily oral

iron(III)-hydroxide polymaltose on moderate puerperal

iron-deficiency anemia. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 13:647–653.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Jenq CC, Tian YC, Wu HH, Hsu PY, Huang JY,

Chen YC, Fang JT and Yang CW: Effectiveness of oral and intravenous

iron therapy in haemodialysis patients. Int J Clin Pract.

62:416–422. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Johnson DW: Intravenous versus oral iron

supplementation in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int. 27

(Suppl 2):S255–S260. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Keeler BD, Simpson JA, Ng O, Padmanabhan

H, Brookes MJ and Acheson AG: IVICA Trial Group. Randomized

clinical trial of preoperative oral versus intravenous iron in

anaemic patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 104:214–221.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Khalil A, Goodhand JR, Wahed M, Yeung J,

Ali FR and Rampton DS: Efficacy and tolerability of intravenous

iron dextran and oral iron in inflammatory bowel disease: A

case-matched study in clinical practice. Eur J Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 23:1029–1035. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Lindgren S, Wikman O, Befrits R, Blom H,

Eriksson A, Grännö C, Ung KA, Hjortswang H, Lindgren A and Unge P:

Intravenous iron sucrose is superior to oral iron sulphate for

correcting anaemia and restoring iron stores in IBD patients: A

randomized, controlled, evaluator-blind, multicentre study. Scand J

Gastroenterol. 44:838–845. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Macdougall IC, Bock AH, Carrera F, Eckardt

KU, Gaillard C, Van Wyck D, Roubert B, Nolen JG and Roger SD:

FIND-CKD Study Investigators. FIND-CKD: A randomized trial of

intravenous ferric carboxymaltose versus oral iron in patients with

chronic kidney disease and iron deficiency anaemia. Nephrol Dial

Transplant. 29:2075–2084. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Mafodda A, Giuffrida D, Prestifilippo A,

Azzarello D, Giannicola R, Mare M and Maisano R: Oral sucrosomial

iron versus intravenous iron in anemic cancer patients without iron

deficiency receiving darbepoetin alfa: A pilot study. Support Care

Cancer. 25:2779–2786. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Montano-Pedroso JC, Garcia EB, de Moraes

MAR, Veiga DF and Ferreira LM: Intravenous iron sucrose versus oral

iron administration for the postoperative treatment of

post-bariatric abdominoplasty anaemia: An open-label, randomised,

superiority trial in Brazil. Lancet Haematol. 5:e310–e320.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Mudge DW, Tan KS, Miles R, Johnson DW,

Badve SV, Campbell SB, Isbel NM, van Eps CL and Hawley CM: A

randomized controlled trial of intravenous or oral iron for

posttransplant anemia in kidney transplantation. Transplantation.

93:822–826. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Noronha V, Joshi A, Patil VM, Banavali SD,

Gupta S, Parikh PM, Marfatia S, Punatar S, More S, Goud S, et al:

Phase III randomized trial comparing intravenous to oral iron in

patients with cancer-related iron deficiency anemia not on

erythropoiesis stimulating agents. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol.

14:e129–e137. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Pisani A, Riccio E, Sabbatini M, Andreucci

M, Del Rio A and Visciano B: Effect of oral liposomal iron versus

intravenous iron for treatment of iron deficiency anaemia in CKD

patients: A randomized trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 30:645–652.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Short V, Allen R, Earley CJ, Bahrain H,

Rineer S, Kashi K, Gerb J and Auerbach M: A randomized double-blind

pilot study to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of

intravenous iron versus oral iron for the treatment of restless

legs syndrome in patients with iron deficiency anemia. Am J

Hematol. 99:1077–1083. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Stoves J, Inglis H and Newstead CG: A

randomized study of oral vs intravenous iron supplementation in

patients with progressive renal insufficiency treated with

erythropoietin. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 16:967–974.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Van Wyck DB, Roppolo M, Martinez CO, Mazey

RM and McMurray S: United States Iron Sucrose (Venofer) Clinical

Trials Group. A randomized, controlled trial comparing IV iron

sucrose to oral iron in anemic patients with nondialysis-dependent

CKD. Kidney Int. 68:2846–2856. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Liu LM and Wu DP: Application progress of

high-dose intravenous iron in the treatment of iron deficiency

anemia. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 43:960–963. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Chinese).

|

|

37

|

Adhikary L and Acharya S: Efficacy of IV

iron compared to oral iron for increment of haemoglobin level in

anemic chronic kidney disease patients on erythropoietin therapy.

JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 51:133–136. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhang Q, Wang H, Zhang YM, Li XL, Shen YY,

Wei N, Zou K, Su WX, Dai HP, Wu DP and Liu LM: Comparison of the

efficacy and safety between high-dose intravenous iron and oral

iron in treating iron deficiency anemia: a multicenter,

prospective, open-label, randomized controlled study. Zhonghua Xue

Ye Xue Za Zhi. 45:1113–1118. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Chinese).

|

|

39

|

Gilreath JA and Rodgers GM: How I treat

cancer-associated anemia. Blood. 136:801–813. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Richards T, Baikady RR, Clevenger B,

Butcher A, Abeysiri S, Chau M, Macdougall IC, Murphy G, Swinson R,

Collier T, et al: Preoperative intravenous iron to treat anaemia

before major abdominal surgery (PREVENTT): A randomised,

double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 396:1353–1361.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Pasricha SR, Flecknoe-Brown SC, Allen KJ,

Gibson PR, McMahon LP, Olynyk JK, Roger SD, Savoia HF, Tampi R,

Thomson AR, et al: Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency

anaemia: A clinical update. Med J Aust. 193:525–532.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Tolkien Z, Stecher L, Mander AP, Pereira

DI and Powell JJ: Ferrous sulfate supplementation causes

significant gastrointestinal side-effects in adults: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 10(e0117383)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Geisser P and Burckhardt S: The

pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of iron preparations.

Pharmaceutics. 3:12–33. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|