Introduction

Seminoma, comprising 55% of all testicular

malignancies, is the most common subtype of testicular cancer

(1). The widely accepted hypothesis

for the origin of testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT) is that they

derive from primordial germ cell or gonocytes whose maturation is

disturbed. Seminoma usually occurs in patients ranging from 15 to

44 years of age (2). It is reported

that epidemiological risk factors of TGCT include previous TGCT in

the contralateral testis, cryptorchidism, hypospadias, male

infertility and exposure to environment factors, such as

organochlorines, polychlorinated biphenyls, polyvinyl chloride,

phthalates, cannabis and tobacco (3). A primary abdominal seminoma harboring

KIT mutation was reported, which was misdiagnosed as

gastrointestinal stromal tumor via biopsy pathology, revealing the

diagnostic pitfalls caused by atypical pathological features,

insufficient immunohistochemical data and inadequate understanding

of the KIT mutation-associated disease spectrum.

Case presentation

A 53-year-old male patient was admitted to a local

hospital due to fatigue in March 2024, with no previous medical

history. The 53-year-old male patient was found to have a huge

abdominal mass with a maximum diameter of 16 cm, via computed

tomography (CT). Ultrasound-guided needle biopsy was performed to

establish a definitive histopathological diagnosis prior to

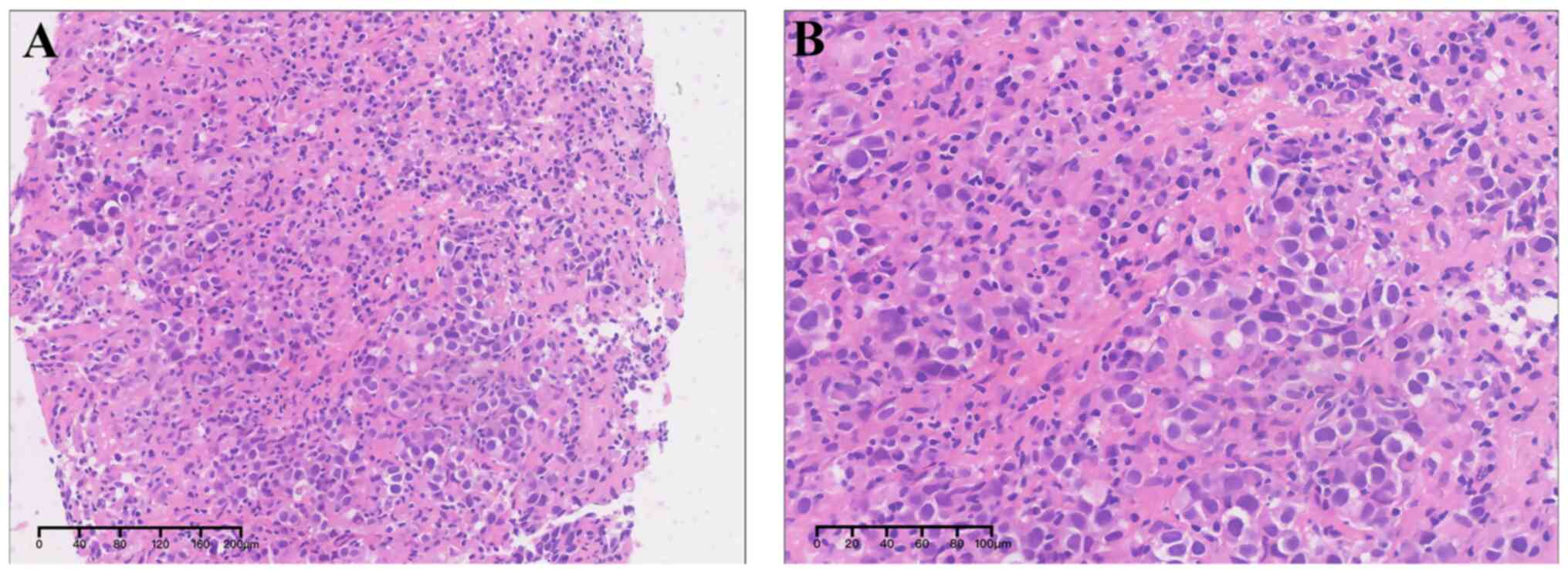

multidisciplinary therapeutic planning. Histologically,

significantly atypical cells, characterized by nuclei pleomorphism,

increased nucleoplasmic ratio, prominent nucleoli, granular

chromatin and visible mitotic figures, were observed to be

diffusely distributed, with scattered infiltration of inflammatory

cells, small vessel formation, and fibrous tissue hyperplasia

(Fig. 1). Immunohistochemical

staining for CD117, DOG-1, CD34, Des, and S100 was performed using

the DAKO immunohistochemical automatic staining machine (DAKO

Omnis/GI100) following Envision 2-step protocol. The primary

antibodies used were CD117 rabbit anti-human (clone 104D2; 1:100

dilution), Des rabbit anti-human (clone D33; 1:100 dilution), and

S100 rabbit anti-human (clone A5109; 1:500 dilution) purchased from

Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc., DOG-1 rabbit anti-human (clone

SP31, 1:100 dilution) purchased from Abcam, and CD34 mouse

anti-human (clone QBEnd/10, 1:100 dilution) purchased from Shanghai

Long Island Antibody Diagnostic Inc. In brief, the tissue sections

were subjected to dewaxing and heat-induced antigen retrieval at

95˚C. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 0.3% hydrogen

peroxide at 37˚C for 30 min. Antigen retrieval was performed in

citrate buffer (10 mmol/l, pH 6.0) at 100°C for 30 min, followed by

three 5-minute washes in PBS. The sections were then blocked with

10% normal goat serum [Biorigin (Beijing) Inc.] for 30 min.

Subsequently, diluted primary antibodies were applied and incubated

overnight at 4˚C. After incubation, Dako Envision kit HRP (cat. no.

K4006; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) was added as a secondary

antibody and incubated at 37˚C for 20 min, followed by three PBS

washes. Color development was carried out using DAB, and

counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin for 30 sec to 1 min.

Finally, the sections underwent gradient dehydration, clearing, and

mounting with neutral balsam. An Olympus BX43F microscope was used

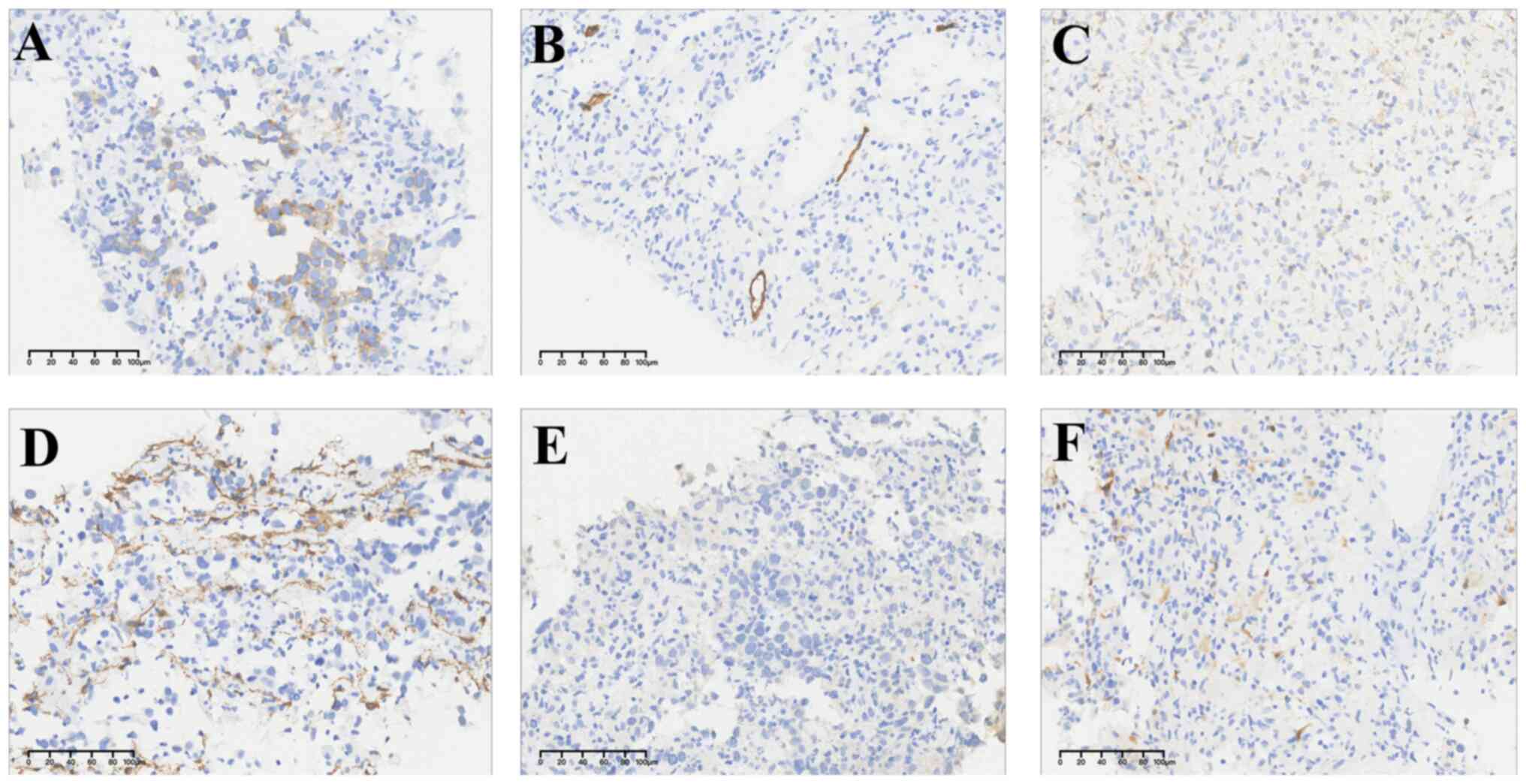

to interpret results. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were

positive for CD117, but negative for DOG-1, CD34, SMA, Des and S100

(Fig. 2). Amplicon-based targeted

next-generation sequencing (NGS) in the affiliated hospital of

Jiangnan University detected molecular alternations, revealing the

mutation in exon 17 of KIT gene (p.Y823D). A diagnosis of malignant

epithelioid GIST was made. Given the massive lesion exceeding 16 cm

in maximal diameter, surgical evaluation deemed the tumor

unresectable for radical resection at the external institution,

prompting attempted targeted therapy to assess potential tumor

downsizing for further surgical intervention. Then the patient

received daily oral imatinib 400 mg. However, 3 months after

targeted therapy in another hospital, CT revealed tumor

enlargement. Although sunitinib, regorafenib and remipatinib were

applied in turn, tumor progression appeared. Given the poor

efficacy, the patient was admitted to the multidisciplinary team

clinic of Zhongshan Hospital for pathology consultation in July

2024. Questioning the original diagnostic results due to the

morphology and the clinical response to treatment, a series of

immunohistochemical markers were applied to establish the

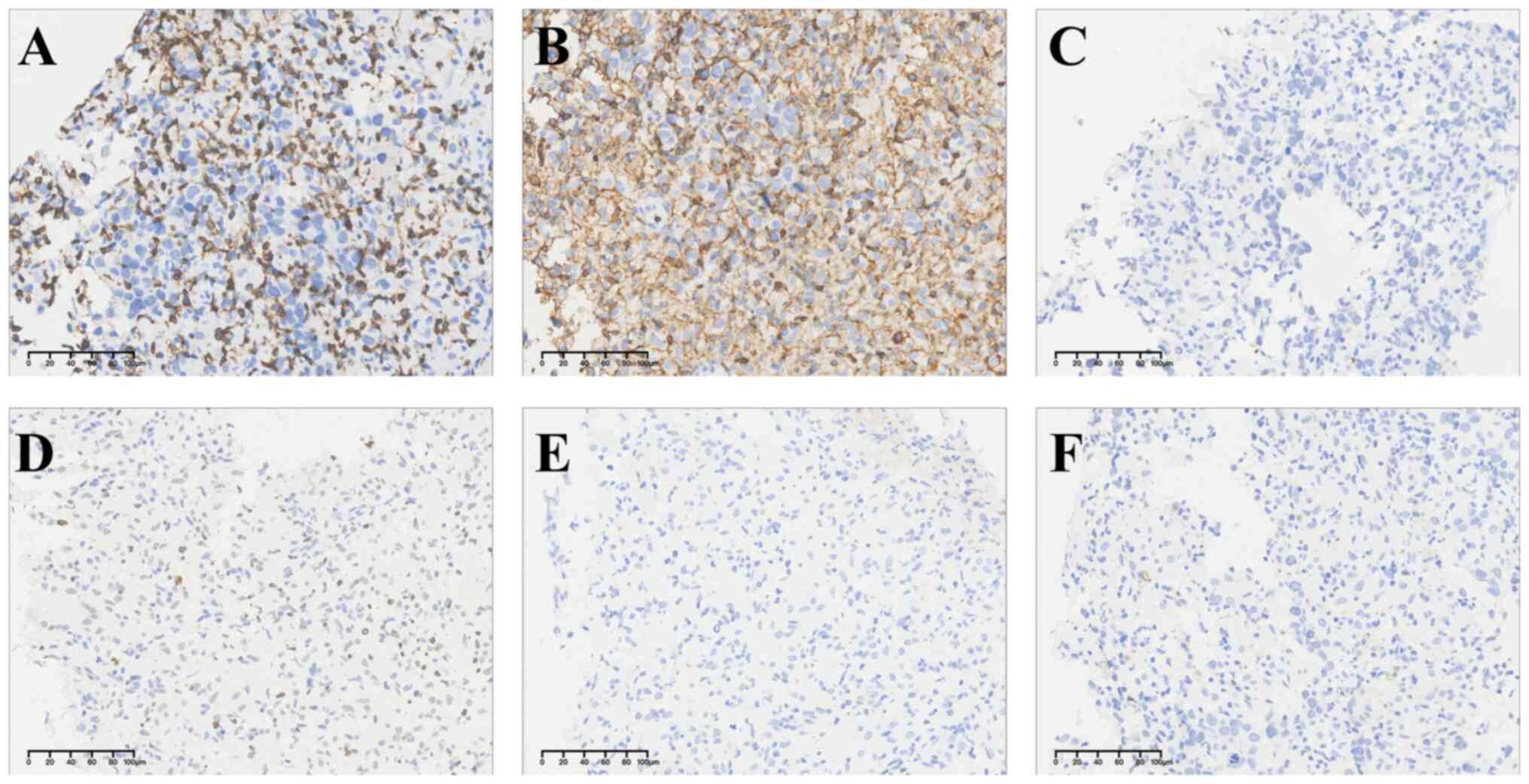

diagnosis. Immunohistochemistry exhibited that LCA and CD3 merely

stained lymphocyte, excluding lymphohematopoietic tumors. No CK7,

CK8, EMA, CgA, Syn, CD56, WT-1, or Calretinin immunoreactivity was

seen in tumor cells, which largely ruled out the possibility of

epithelial tumor, neuroendocrine neoplasm and mesothelioma

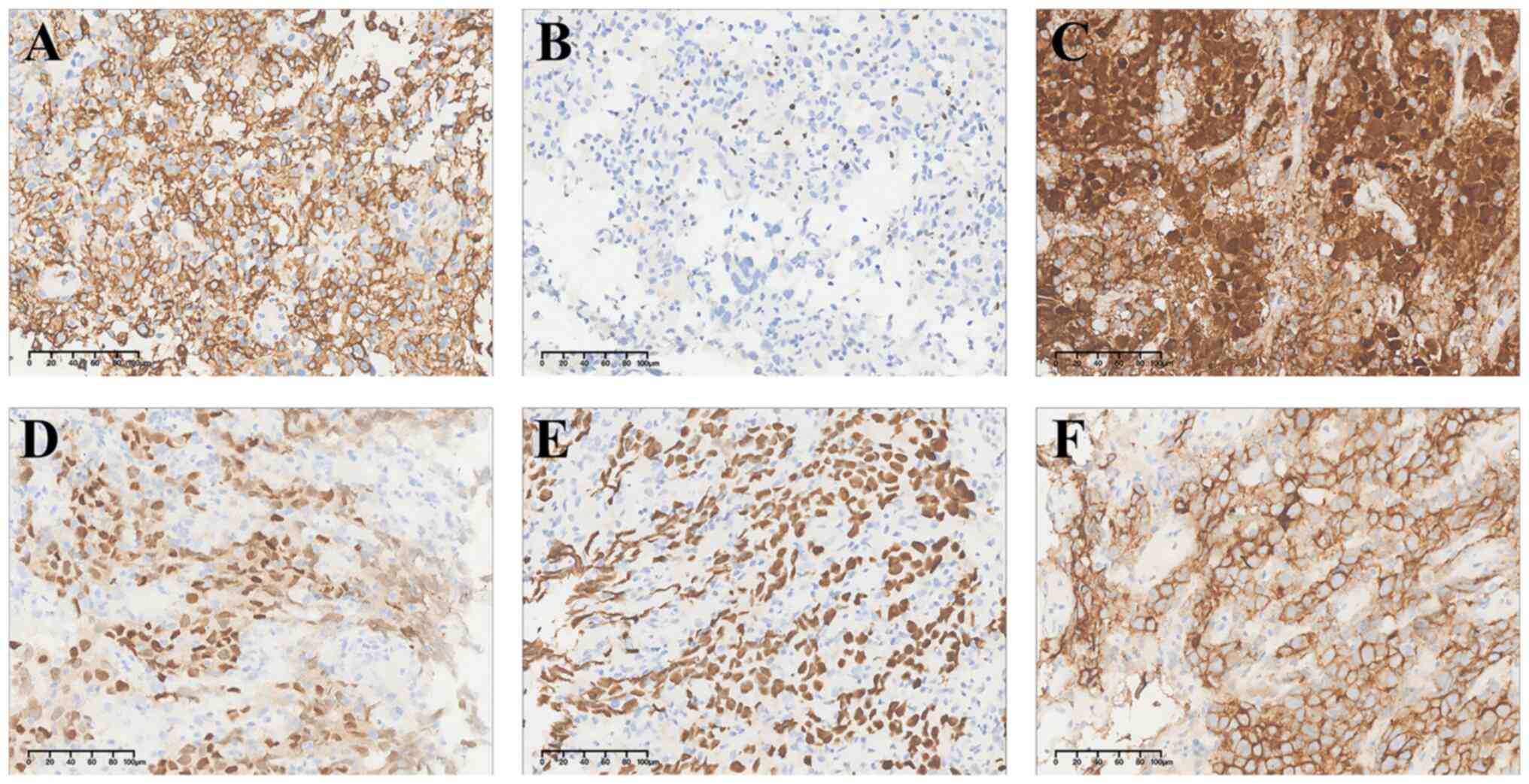

(Fig. 3). OCT4, SALL4, PLAP, SOX17

and D2-40 were strongly expressed in tumor cells, suggesting a

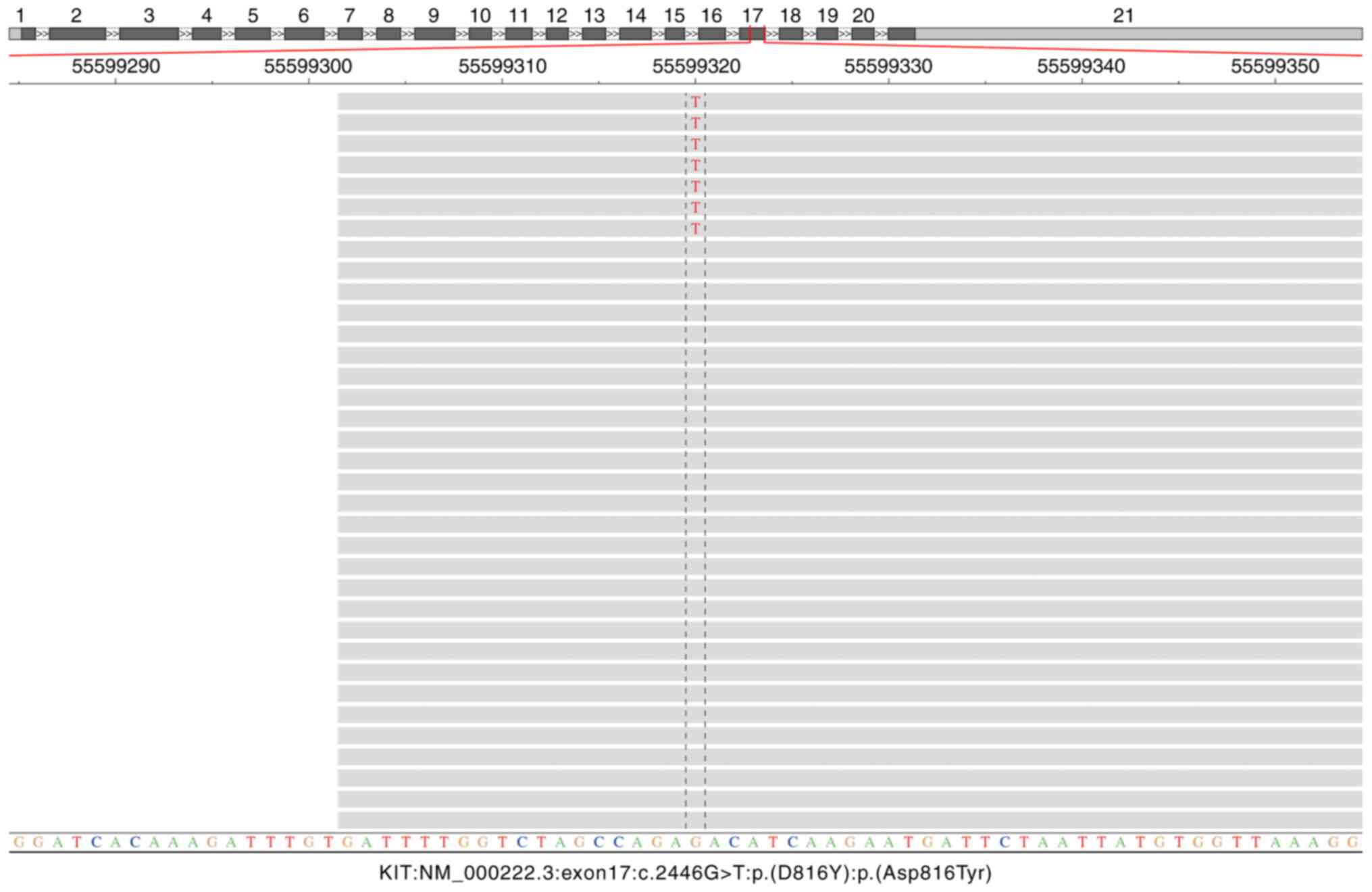

possible origin of tumor in the reproductive system (Fig. 4). Different from original unit

testing results, sanger sequencing and NGS analysis in Zhongshan

Hospital (Shanghai, China) simultaneously detected the point

mutation at codon 816 of exon 17 of KIT (p.D816Y) (Fig. 5). NGS workflow was as follows:

Nucleic acids were extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

(FFPE) tissue sections using the FFPE DNA Automated Nucleic Acid

Extraction Kit (cat. no. 8.02.0071), according to the

manufacturer's instructions. DNA concentration was measured by

Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the total

amount of DNA exacted from tissue samples should exceed 60 ng. The

extracted DNA was sheared into fragments of 200-250 bp using a

Covaris LE220 system. (Index NGS libraries were constructed through

sequential steps of end repair, A-tailing, adaptor ligation, and

PCR amplification using the NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Prep

Kit (cat. no. E7645; NEB). Targeted capture was performed using the

AmoyDx® Master Panel covering 571 genes associated with

DNA mutations. The resulting libraries were quantified by the

Quantus™ Fluorometer, showing a concentration of at least 4.5 pM,

and library fragment size distribution was assessed with the

Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Pooled libraries were sequenced on an

Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with 2x150 bp pair-end reads,

employing the Illumina Novaseq 6000 S1 Reagent kit v1.5 (300

cycles; cat. no. 20028317; Illumina, Inc.). Demultiplexing and

FASTQ file generation were carried out using bcl2fastq v2.17

software (Illumina, Inc.), which also initiated the automated

downstream analysis pipeline. Ultimately, a diagnosis of seminoma

was confirmed. The present study was performed in accordance with

the research policies approved by Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan

University [approval no. B2020-101(2)R]. Informed consent was waived from the

Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University.

Discussion

Patients with seminoma generally present with a

palpable mass and may experience pain. Serum levels of

alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) are elevated, but this is not a specific

marker. Patients with syncytiotrophoblasts have increased serum

human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG), usually not exceeding 1,000

mIU/ml. Imaging shows that the mass has well-defined borders and

exhibits homogeneous hypoechogenicity.

Gross examination reveals a solid tumor, which is

often lobulated, with gray-white to yellow cut surfaces,

well-defined margins and homogeneous texture. Hemorrhage or

necrosis is barely observed in seminoma; otherwise, seminoma mixed

with components from other germ cell tumors may be suggested.

Histologically, classical seminoma is characterized by uniformly

shaped germ cells arranged in a diffuse sheet-like pattern, which

is separated into small lobules, strands, or nests by fibrous

vascular septa. Tumor cells have clear boundaries and transparent

cytoplasm rich in glycogen. The nuclei are large and centrally

located, with regular shapes and clumped chromatin. One or more

prominent nucleoli are often visible, along with varying numbers of

mitotic figures. Also, the infiltration of different lymphocytes

and plasma cells can be observed in the tumor stroma. A total of

~25% of seminomas may show a granulomatous reaction and

multinucleated giant cells, which can obscure their original

characteristics. Anaplastic seminoma is noted for significant

cellular atypia, accompanying with an increased number of mitotic

figures (>3/HPF) and few interstitial lymphocytes.

Immunohistochemistry can aid in diagnosis when the morphology is

atypical. Tumor cells are positive for germ cell markers such as

SALL4, OCT3/4, D2-40, PLAP, CD117, and SOX17, while negative for

CK, CD30 and AFP (4). HCG,

cytokeratin and pregnancy associated proteins are expressed in

syncytiotrophoblasts.

The pathological diagnosis in this case contained

two critical errors. First, a seminoma was misdiagnosed as a GIST.

Second, the genetic analysis revealed a point mutation at codon 816

(p.D816Y) in exon 17 of the KIT gene, which was discordant with the

external laboratory report documenting a mutation at codon 823

(p.Y823D) within the same exon. The misdiagnosis of GIST by the

external institution may be attributed to a combination of atypical

clinical and histopathological features. The patient's presentation

with a large abdominal mass instead of a testicular lesion deviated

from the classic seminoma phenotype, while limited tissue sampling

via biopsy hindered definitive morphological assessment, with tumor

cells lacking hallmark characteristics such as clear cytoplasm and

prominent nucleoli. Furthermore, the uncritical acceptance of CD117

immunopositivity and KIT mutation detection as pathognomonic for

GIST likely contributed to diagnostic inaccuracy, reflecting

insufficient integration of morphological, immunohistochemical and

clinical data.

A critical reappraisal reveals diagnostic clues that

could have alerted pathologists to the misclassification.

Morphologically, GISTs predominantly exhibit spindle cell

morphology, with mixed or pure epithelioid subtypes accounting for

<50% of cases. Notably, such epithelioid GISTs predominantly

arise in the stomach and are typically associated with PDGFRA

mutations or SDH deficiency, rendering the coexistence of KIT

mutations with epithelioid morphology biologically incongruous

(5). Furthermore, the

immunohistochemical profile in this case, solitary CD117 expression

without DOG1 or CD34 co-expression, deviates from diagnostic

standards. As emphasized in the Clinical Practice Guidelines for

GIST Diagnosis, definitive GIST classification mandates rigorous

exclusion of other CD117-positive neoplasms. The differential

diagnosis should comprehensively encompass both epithelial

malignancies (for example, adenoid cystic carcinoma, secretory

carcinoma, basal cell adenoma, eccrine spiradenoma, renal

oncocytoma, chromophobe renal carcinoma, basal cell adenoma,

eccrine spiradenoma, renal oncocytoma, chromophobe renal cell

carcinoma, thymic carcinoma, pulmonary small cell carcinoma) and

non-epithelial tumors (for example, angiosarcoma, granulocytic

sarcoma, mast cell neoplasms, malignant melanoma and seminoma),

particularly when confronted with atypical morphological and

immunophenotypic features (6).

Besides, the molecular findings in this case exhibited biological

incongruity with typical GIST profiles. Although KIT mutations

constitute the most common genetic alterations in GIST, primary

tumors predominantly harbor exon 9 (10~15%) or exon 11 (60~70%)

mutations (7). Exon 13 and 17

mutations are exceptionally rare in primary GISTs (1~2%), with exon

17 variants historically containing p.A795P (1 case), p.D816F (1

case), p.D816Y (1 case), pD820A (1 case), p.D820Y (1 case), p.D820V

(1 case), p.N822K (15 cases), p.N822Y (1 case) and p.Y823D (1 case)

(8-10).

It is also demonstrated that exon 17 mutation of KIT is mainly

found as a secondary gene mutation in drug-resistance GIST after

the failure of targeted therapy, with specific codons including

N822K (43.94%), Y823D (22.73%), D816H (15.15%), D820Y (6.06%),

C809G (4.55%), N822Y (4.55%) and A829P (3.03%) (11,12).

Crucially, the mere presence of KIT mutations cannot confirm GIST

diagnosis, as such alternations are documented in 8~15% of other

CD117-positive malignancies including angiosarcoma, granulocytic

sarcoma, mast cell neoplasms, malignant melanoma and seminoma

(13). KIT gene mutations occur in

8.2~25.8% of seminomas, predominantly localized to exon 17

(14,15).

The most frequent hotspot involves codon 816

(p.D816V/H), accounting for approximately 35% of cases, followed by

codon 882 (p.N822K) with 22% frequency. Additional exon 17 variants

(e.g., p. K642E, p.N655K, p.D820Y, p.Y823C, p.Y823D, p.A829T) have

been reported at lower frequencies. Exon 11 mutations (3~6%)

predominantly affect codons 557 (p.W557S), 576 (p.L576P), and 578

(p.Y578C) (16). Critically, the

p.D816V mutation in this case strongly supports seminoma over GIST,

as exon 17 mutations are exceptionally rare (<1%) in primary

GISTs while prevalent in seminoma.

Different genotypes of KIT mutations are associated

with diversified response to specific TKIs. Imatinib, initially

developed as a BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor, was subsequently

identified to potently inhibit KIT receptor tyrosine kinase

activity and to be the first-line therapy for GISTs, particularly

in patients harboring KIT exon 11 mutation or specific exon 17

variants (for example, p.N22K and p. Y823D) (7). However, several exon 17 mutants, such

as p.D816V/H, are resistant to imatinib treatment (13). In the present study, this further

explained the disease progression in the short term after imatinib

treatment in this patient.

Patients with stage I or localized disease are

treated with radical orchiectomy followed by risk-adapted

management: Active surveillance (preferred for low-risk patients)

or adjuvant therapy based on established risk factors (tumor size

>4 cm, rete testis invasion). Stage IIA/B requires

post-orchiectomy treatment with either radiotherapy (20~30 Gy to

involved fields) or chemotherapy (BEP x 3 cycles).

Advanced/unresectable disease mandates first-line cisplatin-based

chemotherapy (BEP x 3-4 cycles), achieving 83% disease-specific

survival at 5 years (17). Notably,

targeted therapies (imatinib/sunitinib/pazopanib) demonstrate

limited efficacy with objective response rate <15%, reflecting

intrinsic resistance mechanism in germ cell malignancies (18).

There are several limitations in the present study.

First, a critical limitation of this report was the unavailability

of primary CT imaging findings essential for diagnosing

extragonadal seminoma. During pathological consultation at our

institution for diagnostic verification, only textual radiological

descriptions from an external facility were provided and original

DICOM images were unobtainable. Furthermore, no supplemental CT

imaging or therapeutic interventions were pursued at our center,

constraining comprehensive clinicopathological correlation. In

addition, another limitation was the omission of serum tumor

markers (AFP, β-HCG and LDH) during initial diagnosis of the case.

Although these biomarkers provide substantial diagnostic utility in

seminoma detection, particularly in extragonadal presentations,

their measurement was overlooked due to the original misdiagnosis

of GIST based solely on CD117 immunopositivity and reported KIT

mutation. This precluded timely diagnostic rectification through

serological correlation.

In conclusion, this diagnostic pitfall underscores

the imperative for morphology-driven, multidisciplinary evaluation

when interpreting CD117-positive tumors. Solitary CD117 expression

requires systematic exclusion of other CD117-positive malignancies

to diagnose GIST. Reliance solely on molecular findings risks

misclassification. Although KIT mutations support GIST diagnosis in

appropriate contexts, rare mutation loci more strongly align with

non-GIST neoplasms. Furthermore, interlaboratory variability in

molecular alternation necessitates validation by multiple detection

methods including sanger sequencing and NGS, and correlation with

histomorphology. Notably, rapid disease progression on multi-line

targeted therapy, despite reported KIT mutation, should prompt

immediate reassessment of diagnostic validity, including expert

histopathology review and expanded molecular profiling.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the National Nature

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 32571067).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the SRA database under accession number PRJNA1304866 or at the

following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1304866.

Authors' contributions

XZ, WY and YH contributed to the conception and the

design of the study. LR and CX contributed to the acquisition,

analysis, and interpretation of the data. XZ and YH contributed to

drafting the manuscript and revising the manuscript. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript. XZ and WY

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed in accordance with

the research policies approved by Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan

University [approval no. B2020-101(2)R]. Informed consent was waived from the

Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Marko J, Wolfman DJ, Aubin AL and

Sesterhenn IA: Testicular seminoma and its mimics: From the

radiologic pathology archives. Radiographics. 37:1085–1098.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Ghazarian AA, Trabert B, Devesa SS and

McGlynn KA: Recent trends in the incidence of testicular germ cell

tumors in the United States. Andrology. 3:13–18. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Fukawa T and Kanayama HO: Current

knowledge of risk factors for testicular germ cell tumors. Int J

Urol. 25:337–344. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lau SK, Weiss LM and Chu PG: D2-40

immunohistochemistry in the differential diagnosis of seminoma and

embryonal carcinoma: A comparative immunohistochemical study with

KIT (CD117) and CD30. Mod Pathol. 20:320–325. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Medeiros F, Corless CL, Duensing A,

Hornick JL, Oliveira AM, Heinrich MC, Fletcher JA and Fletcher CD:

KIT-negative gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Proof of concept and

therapeutic implications. Am J Surg Pathol. 28:889–894.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Casali PG, Blay JY, Abecassis N, Bajpai J,

Bauer S, Biagini R, Bielack S, Bonvalot S, Boukovinas I, Bovee

JVMG, et al: Gastrointestinal stromal tumours:

ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis,

treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 33:20–33. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ibrahim A and Montgomery EA:

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Variants and some pitfalls that

they create. Adv Anat Pathol. 31:354–363. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Pai T, Bal M, Shetty O, Gurav M, Ostwal V,

Ramaswamy A, Ramadwar M and Desai S: Unraveling the spectrum of KIT

mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: An Indian tertiary

cancer center experience. South Asian J Cancer. 6:113–117.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Calibasi G, Baskin Y, Alyuruk H, Cavas L,

Oztop I, Sagol O, Atila K, Ellidokuz H and Yilmaz U: Molecular

analysis of the KIT gene in gastrointestinal stromal tumors with

novel mutations. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 22:37–45.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Lasota J, Corless CL, Heinrich MC,

Debiec-Rychter M, Sciot R, Wardelmann E, Merkelbach-Bruse S,

Schildhaus HU, Steigen SE, Stachura J, et al: Clinicopathologic

profile of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) with primary KIT

exon 13 or exon 17 mutations: A multicenter study on 54 cases. Mod

Pathol. 21:476–484. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Serrano C, Bauer S, Gómez-Peregrina D,

Kang YK, Jones RL, Rutkowski P, Mir O, Heinrich MC, Tap WD,

Newberry K, et al: Circulating tumor DNA analysis of the phase III

VOYAGER trial: KIT mutational landscape and outcomes in patients

with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated with

avapritinib or regorafenib. Ann Oncol. 34:615–625. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Du J, Wang S, Wang R, Wang SY, Han Q, Xu

HT, Yang P and Liu Y: Identifying secondary mutations in Chinese

patients with Imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors

(GISTs) by next generation sequencing (NGS). Pathol Oncol Res.

26:91–100. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Lennartsson J and Rönnstrand L: Stem cell

factor receptor/c-Kit: From basic science to clinical implications.

Physiol Rev. 92:1619–1649. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

McIntyre A, Summersgill B, Grygalewicz B,

Gillis AJ, Stoop J, van Gurp RJ, Dennis N, Fisher C, Huddart R,

Cooper C, et al: Amplification and overexpression of the KIT gene

is associated with progression in the seminoma subtype of

testicular germ cell tumors of adolescents and adults. Cancer Res.

65:8085–8089. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Kemmer K, Corless CL, Fletcher JA,

McGreevey L, Haley A, Griffith D, Cummings OW, Wait C, Town A and

Heinrich MC: KIT mutations are common in testicular seminomas. Am J

Pathol. 164:305–313. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Nakhaei-Rad S, Soleimani Z, Vahedi S and

Gorjinia Z: Testicular germ cell tumors: Genomic alternations and

RAS-dependent signaling. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol.

183(103928)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

de Vries G, Rosas-Plaza X, van Vugt MATM,

Gietema JA and de Jong S: Testicular cancer: Determinants of

cisplatin sensitivity and novel therapeutic opportunities. Cancer

Treat Rev. 88(102054)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Galvez-Carvajal L, Sanchez-Muñoz A,

Ribelles N, Saez M, Baena J, Ruiz S, Ithurbisquy C and Alba E:

Targeted treatment approaches in refractory germ cell tumors. Crit

Rev Oncol Hematol. 143:130–138. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|