Osteoporosis (OP) is a systemic metabolic bone

disease characterized by degradation of bone microstructure, bone

fragility, and increased fracture risk (1). OP affects 10.2% of adults >50 years

of age and is expected to increase to 13.6% by 2030(2). Annually, >150 million individuals

suffer from OP, and the disease poses a great threat to the quality

of life for >50% of postmenopausal women, with the most severe

risk being osteoporotic fractures (3). OP is influenced by the process of bone

loss, and its therapeutic goal is to halt bone mass reduction and

rectify the imbalance in bone remodeling. Currently, certain drugs

are effective in mitigating bone loss or increasing bone calcium

content. The commonly employed drugs for OP treatment include

bisphosphonates, estrogens, norepinephrine, and teriparatide

acetate. However, the prolonged and high-dose administration of

these agents may cause adverse effects such as hypercalcemia,

gastrointestinal reactions, and an increased risk of breast cancer

and heart disease (4,5). With the in-depth study into the

pathogenesis of OP, the relationship between intestinal

microecology and bone metabolism (BM) has become a worldwide

research hotspot. Studies indicate that the gut microbiota (GM) is

associated with the reduction of bone mass and the development of

OP in humans (6-8).

The intestinal microecosystem is the largest

ecosystem within the human body, harboring >1014

orders of magnitude of bacteria, with the total number of genes in

the gut microbiome genome being ~150-fold that of the human genome

(9). The GM is mainly dominated by

Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, which together account

for over 90% of the relative abundance, followed by

Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and

Fusobacteria (10). The GM

exhibits variabilities between individuals and dynamic changes

throughout the lifetime of an individual and is influenced by a

variety of factors, including diet, age, lifestyle, medications,

and disease states. The GM plays a regulatory role in multiple

physiological functions, encompassing the enteric nervous system,

enteroendocrine system, immune system, and intestinal permeability

(11,12). Specific GM can modulate immunity,

improve defense function, promote skeletal health, and inhibit bone

calcium loss. Additionally, it can improve intestinal permeability,

reduce inflammatory responses, and facilitate nutrient absorption

(13). Imbalance of intestinal

flora affects calcium absorption, subsequently triggering

inflammatory and autoimmune changes, leading to bone loss and

reduced bone formation (14-18).

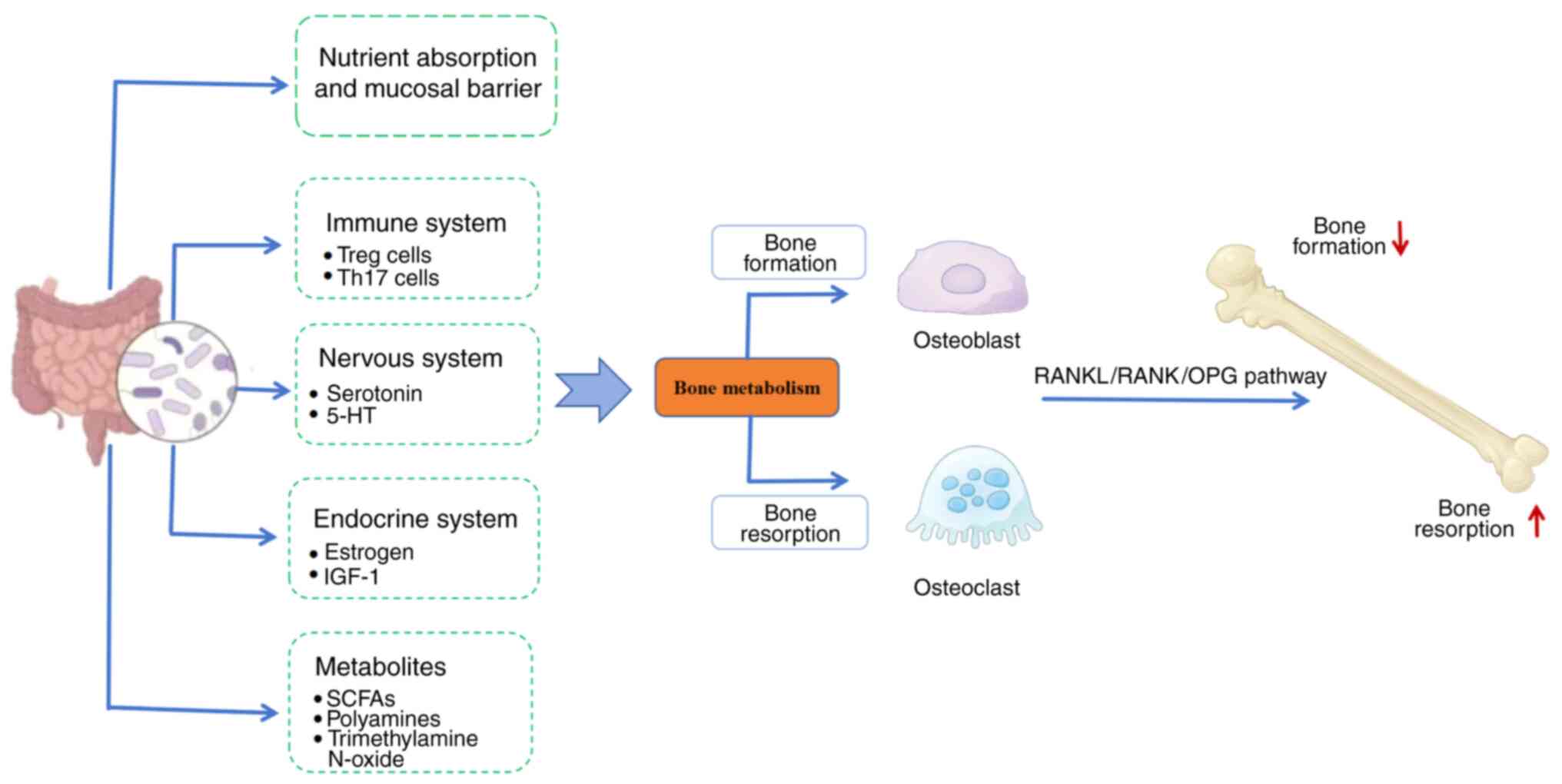

Therefore, GM is closely associated with the occurrence of OP, and

the restoration of GM imbalance has become a key approach to

treating OP, as revealed in Fig. 1.

In the present review, the latest advancements in the association

between GM and OP are examined, elucidating the role of GM in the

pathogenesis and treatment of OP. The aim of the review is to

explore novel therapeutic strategies and research directions for OP

and related diseases.

Articles on the treatment of OP with traditional

Chinese medicine (TCM) through regulation of GM were collected

using the keywords ‘osteoporosis’, ‘gut microbiota’, and

‘traditional Chinese medicine’ by searching in PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and Web of

Science (https://www.clarivate.com.cn/). The search period was

from the inception of each database up to August, 2025. To ensure

the quality of literature and accuracy of data extraction, the

search was limited to articles published in English.

Intestinal microflora can affect the energy

homeostasis of the host organism and serve as a source of energy

for the differentiation and formation of osteoblasts (OBs) and

osteoclasts (OCs). In cases of aberrant energy metabolism, the OB

precursors will shift to adipose differentiation (19). The composition of bacterial

structures, characterized by varying quantities and ratios of

different bacterial genera, forms diverse GM structures, which in

turn have differential effects on BM (13,20).

Reduced bone mass in the lumbar vertebrae and femoral neck is

associated with excessive growth of gut bacteria, suggesting that

overgrowth of the GM may constitute a significant risk factor for

OP (21). Another study further

validated this finding (22). The

administration of antibiotics in the diet was shown to modulate the

GM, thereby promoting growth and skeletal development (11). The increase in bone mass in

germ-free mice (GFM) was associated with a decrease in the number

of OCs (12). Bone marrow cultures

revealed that the number of OCs was reduced in GFM, accompanied by

a significant reduction in the formation of

CD11b+/Gr1- and CD4+ T cells in

the precursor OC population (13).

Microbial transplantation of GFM led to an increase in the number

of bone marrow CD4+ T cells and OC precursors, along

with a decrease in bone mass, suggesting the key regulatory role of

the GM in the process of BM. Additionally, studies have identified

associations between GM and both postmenopausal (PM)OP and senile

OP (23,24). Elevated levels of trimethylamine

N-oxide (TMAO), a metabolite of GM, have been shown to have a

strong negative correlation with the degree of bone mineral density

(BMD) in OP. TMAO has been demonstrated to regulate the cell

function of BMSCs by activating the NF-κB signaling pathway, which

affects the balance of BM, leading to acceleration of bone loss and

further progression of OP (25).

Furthermore, estrogen-deficient GFM exhibited reduced bone mass,

while probiotic interventions effectively prevented loss of bone

mass (26). 5-Hydroxytryptamine

(5-HT) levels were increased after the introduction of specific

Escherichia coli in GFM (27). Lactobacillus reuteri not only

reduced the level of bone resorption markers and inhibited OC

formation, but also suppressed the expression of tumor necrosis

factor-α (TNF-α) and modulated the level of Wnt10b RNA in OBs

cultured in vitro (28,29).

In clinical research, changes have been observed in

the abundance and diversity of the GM, as well as in their

associated metabolites, in patients with OP (30). Distinct differences exist in the GM

between patients with OP and healthy populations (31). A previous meta-analysis encompassing

12 studies included fecal data from 2,033 subjects (604 patients

with OP and 1,429 healthy controls). It observed increased relative

abundances of Lactobacillus and Ruminococcus in the

OP group, along with a higher proportion of Bacteroides

(32). With an expanded sample

size, research has identified that an increase in

Bacteroidetes and a decrease in Firmicutes may be

important factors in the GM imbalance triggering OP (33). In a previous study,

Klebsiella, Escherichia-Shigella, and

Akkermansia were identified as biomarkers in patients with

OP. Among them, the abundance of Akkermansia was negatively

correlated with lumbar BMD, while Klebsiella and

Escherichia-Shigella were negatively correlated with femoral

neck and hip BMD (34). In another

study, an increase in the abundance of Actinomyces,

Eggerthella, Clostridium Cluster XlVa and

Lactobacillus was noted in the OP group, suggesting that

alterations in GM abundance may serve as an independent risk factor

for bone mass loss in the elderly (35). Research has indicated a positive

correlation between the relative abundance of

Actinobacillus, Blautia, Oscillospira,

Bacteroides, Phascolarctobacterium and OP, while a

negative correlation was identified with other Veillonellaceae,

Collinsella, and other Ruminococcaceae (36). Another study evaluated the causal

relationship between GM and bone development by determining

specific causal bacterial taxa using Mendelian randomization (MR).

The study revealed that Clostridiales and Lachnospiriaceae

regulate bone mass variation, indicating a causal relationship

between GM and bone development (37). Previous research revealed that

increased abundances of the family Pasteurellaceae, order

Pasteurellales, and genus Ruminococcaceae UCG004 were linked

to an increased risk of OP. Conversely, the family

Oxalobacteraceae, unknown family (ID.1000006161), the genus

Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, an unknown genus

(ID.1000006162), and order NB1n were associated with a

reduced risk of OP (38).

Additionally, other research found that changes in the GM,

including the Lactobacillus genus, are associated with

osteoporosis (39).

Other studies further demonstrated the association

between GM and PMOP, while also exploring the phenomenon of GM

regulating BM (30). Notably,

healthy postmenopausal women exhibited higher abundances of

Clostridia and Methanobacteraceae within their GM, whereas

women with osteopenic/osteoporotic conditions showed a greater

richness of Bacteroidetes in their fecal microbiota.

Therefore, alterations in GM composition are considered closely

associated with OP (40). The

abundance of Fusicatenibacter, Lachnoclostridium, and

Megamonas species was significantly higher in PMOP women

compared to women with osteopenia (41). Researchers have proposed GM as a

potential new target for the treatment of PMOP, highlighting that

GM can influence BM through various mechanisms, such as regulating

the host's immune system, particularly affecting inflammation and

autoimmune responses. For example, GM can promote the production of

regulatory T cells (Tregs) by producing short-chain fatty acids

(SCFAs) such as butyrate and propionate, thereby exerting

anti-inflammatory effects (42).

Reduced α-diversity in GM has been shown to be associated with PMOP

(43). Previous research has

revealed that GM has an essential role to perform as a target for

TCM intervention in bone disease treatment (44). Certain TCMs with natural prebiotic

properties may help combat OP by facilitating the development of

healthy probiotics. Hence, the gut-bone axis may provide an

explanation for the multi-target regulation of TCM in treating OP

(45).

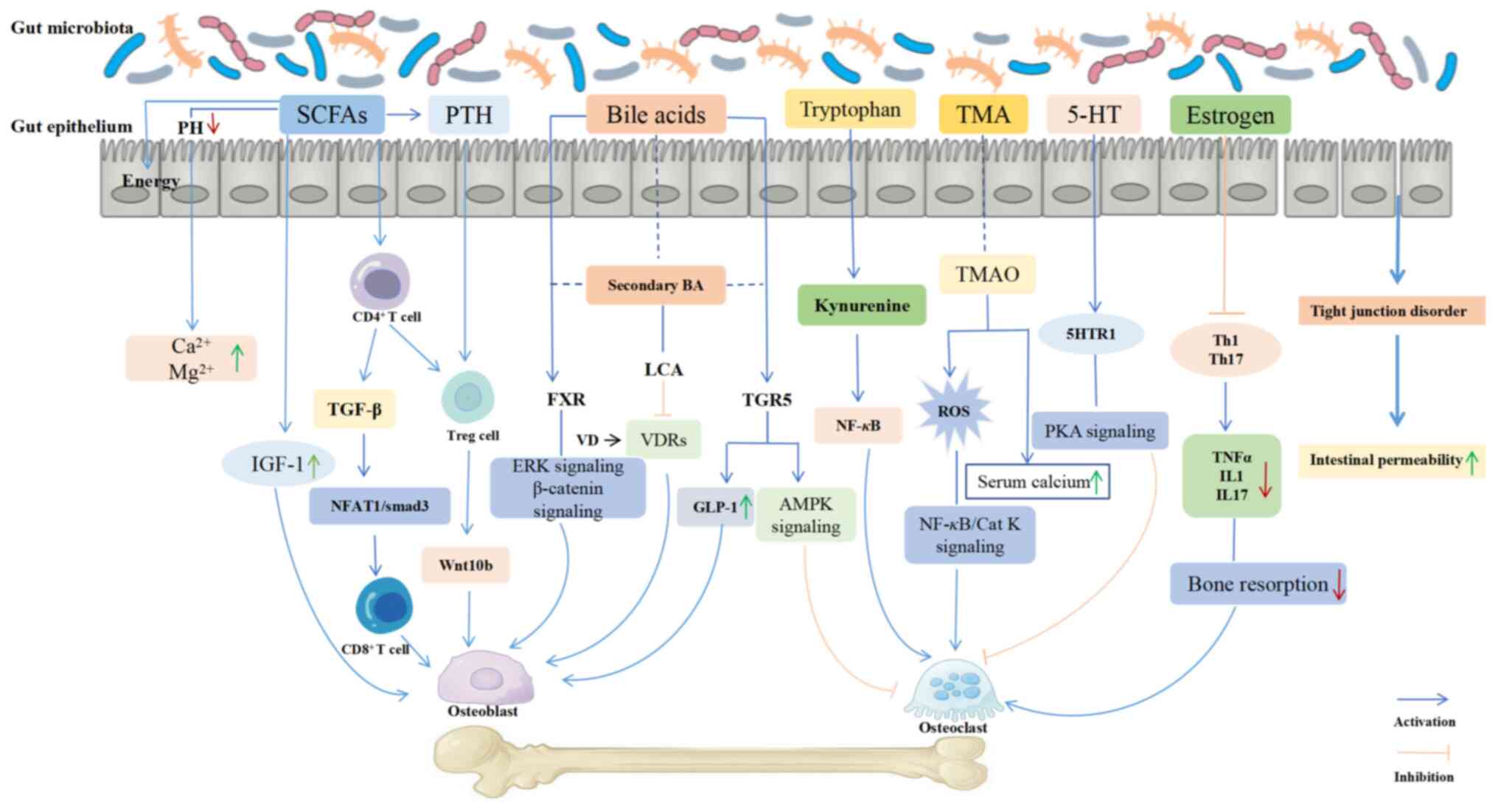

In recent years, the association between GM and OP

has increasingly become a research hotspot. The mechanisms by which

GM influences OP are highly complex. The pivotal role of GM in bone

regulation is elaborated in this section through a multifaceted

approach, including nutrient absorption, intestinal mucosal barrier

permeability, the immune, endocrine, and nervous systems, as well

as metabolites of GM, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Calcium, the major mineral element in human skeletal

tissue, plays an important role in bone formation and is absorbed

in the form of calcium ions. Only 30% of dietary calcium intake is

absorbed by the bones in healthy individuals (46), underscoring the importance of

enhancing calcium absorption to promote bone production. The GM

facilitates the formation of bone calcium and reduces bone loss,

thereby promoting BM (13). The

impact of calcium intake on bone health is closely related to the

quantity and type of flora. Calcium supplements or a high-calcium

diet can increase the population of beneficial bacteria and

maintain the integrity of the GM ecosystem (47). Calcium absorption is associated with

a lower pH in the cecum (20), and

alterations in the microbiota can decrease intestinal pH, impede

the intestinal calcium-acid complexes, enhance calcium solubility,

and increase the amount of calcium available for absorption

(48). The expression of calcium

transporter proteins has been shown to be upregulated, enhancing

calcium absorption and mitigating the downstream effects of bone

resorption on bone (49). Vitamin D

is one of the important substances maintaining bone homeostasis

(50). When insufficient calcium

intake occurs, the GM can produce active vitamin D, promoting

calcium absorption in the gut (51). In addition, intestinal

microorganisms are considered one of the primary sources of

vitamins B and K, both of which play important roles in bone

homeostasis (52).

The intestinal mucosal barrier constitutes the

interface between the human body and the external environment, and

its integrity is critically important for preventing the invasion

of harmful substances, such as toxins and bacteria, into the body

(53).

The intestinal barrier is composed of a mucus layer,

GM, immune cells, and a monolayer of intestinal epithelial cells

(54). Lipopolysaccharides (LPS),

the main component of the bacterial cell wall of GM, induce chronic

inflammatory responses, leading to bone loss. Additionally, LPS

promotes the formation and activation of OCs, thereby further

contributing to bone loss (55).

Conversely, muramyl dipeptide functions to reduce bone resorption

and increase bone mass by downregulating the ratio of the receptor

activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL)/osteoprotegerin (OPG), thereby

indirectly suppressing OC differentiation (56). Barrier damage is universally

observed in all types of OP models, mainly manifesting as

disruption of tight junction proteins, alteration in intestinal

villus morphology, and increased intestinal permeability (57,58).

This compromised intestinal barrier facilitates the translocation

of microbes or potential antigens to subepithelial mucosa, thereby

activating immune cells and triggering aberrant intestinal and

systemic immune responses, ultimately resulting in bone loss

(26). GM affects BM by influencing

mucosal barrier function, with increased membrane levels of

Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on the membrane observed in primary

cells treated with RANKL or LPS. TNF-α is secreted via the

endotoxin/TLR4 signaling pathway and modulates RANKL-induced

osteoclastogenesis (59). The

integrity of the GM prevents bacterial LPS from contacting

macrophage TLR-4 in the lamina propria and prevents OP (60). The impact of GM on the intestinal

mucosal barrier is involved in glucocorticoid-induced OP (61).

OP is characterized as a systemic disease with

chronic low-grade inflammation. Changes in GM can elicit systemic

or localized immune responses, which are closely implicated in the

development of OP (62). The

immunological impact on bone conversion is often manifested by B-

and T-cell activation, along with an increase in osteoclastogenic

factors such as interleukin (IL)-17, IL-6, RANKL, and TNF-α. These

factors enhance the activity of OCs while simultaneously inhibiting

the formation and function of OBs, ultimately exacerbating the

imbalance in BM (63). GM maintains

contact with dendritic cells and immune cells at the vascular

endothelial boundary, stimulating the immune system to release

inflammatory factors. These factors subsequently influence the

immune cell population within bone tissue, thereby modulating the

bone remodeling process (64).

Hematopoietic stem cells in bone tissue have the potential to

differentiate into OCs and immune cells. GM regulates the BM

microenvironment by promoting the maturation of the host immune

system (65). The harmful flora in

GM can produce endotoxins. These endotoxins initiate inflammatory

responses by binding to the TLRs on the surface of host immune

cells, subsequently resulting in bone mass reduction (18). Type helper 17 (Th17) cells, an

integral subset of the CD4+ T-cell OC population, can be

generated and differentiated under GM dysregulation, and secrete

IL-17a, IL-1, IL-6, along with low levels of interferon-γ and TNF.

These cytokines contribute to the release of RANKL and the

formation of OCs (66). Regulatory

T cells are capable of stimulating bone marrow CD8+ T

cells to produce the osteogenic Wnt signaling pathway ligand

Wnt10b, thus promoting osteogenic differentiation (67). It has been found that the expression

of inflammatory factors such as TNF-α and IL-6 is reduced in mice

that maintain a balanced composition of GM. In addition, the number

of T cells in the body is reduced, accompanied by a decrease in the

number of OCs and an improvement in bone quality (12,68).

Endocrine hormones act on various organs within the

body, playing a role in the progression of a variety of

musculoskeletal disorders, including OP. Beneficial bacteria in the

GM can stimulate the secretion of incretins from intestinal cells

(17). Incretins, a group of

gastrointestinal hormones secreted by the intestine that exert

glucose concentration-dependent insulinotropic effects, include

glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and

glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) (69). GIP can bind to surface receptors on

OBs, enhancing the expression of type I collagen genes, promoting

the maturation and mineralization of collagen matrix, increasing

alkaline phosphatase activity, and promoting TGF-β secretion, all

of which contribute to bone formation. GIP interacts with receptors

on pro-OCs to suppress the generation and activity of OCs, thereby

reducing bone resorption. Furthermore, GLP-1 facilitates insulin

secretion from pancreatic β-cells, which in turn promotes bone

formation; GLP-1 also promotes calcitonin secretion from thyroid

C-cells, suppressing bone resorption (70). Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1),

as a growth-promoting endocrine hormone, plays a key role in cell

proliferation, differentiation, and the cell cycle, exerting its

regulatory function through endocrine and paracrine/autocrine

mechanisms. IGF-1 was the first identified substance mediating the

association between GM and OP. Furthermore, it was the earliest

confirmed molecule involved in the interaction between intestinal

flora and OP (71). Research has

demonstrated that IGF-1 promotes the proliferation and

differentiation of OBs, as well as the mineralization of the bone

matrix. It has been shown to play an important role in the

maturation of the growth plate and the formation of the secondary

ossification center (72).

Estrogen, a steroid hormone secreted mainly by the

ovaries, promotes the generation of OCs, while also exerting

regulatory effects on the BM. Under normal physiological

conditions, estrogen, as a product of enterohepatic circulation,

needs to undergo enzymatic hydrolysis by the GM before re-entering

the internal circulation. When the GM is imbalanced, the

enterohepatic circulation is weakened, and the reabsorption

capacity of estrogen decreases, accelerating the loss of bone mass

and the course of OP (73,74). In a previous study it was found that

in GFM or mice subjected to prolonged antibiotic treatment, the

absence of estrogen did not lead to significant bone loss (26). By contrast, in normal animals, the

deficiency of estrogen led to increased intestinal permeability,

allowing a large number of pathogenic bacteria to invade the

intestine, which in turn triggered OP (75). Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG

ameliorated estrogen deficiency-induced osteoporosis by regulating

the gut microbiome and intestinal barrier and stimulating Th17/Treg

balance in the gut and bone (76).

Estrogen has been demonstrated to play a crucial role in

maintaining bone health by reducing bone resorption through the

maintenance of systemic and bone marrow T-cell homeostasis and also

to directly regulate the formation of OB and OC (76-78).

The central nervous system and GM mediate the

transmission of information between the brain and the gut by

chemical signals (such as acetylcholine, γ-aminobutyric acid, and

5-HT), a pathway known as the ‘brain-gut axis’ (79). GM can communicate directly with the

brain through various signaling molecules or indirectly through the

brain-gut axis. Similarly, the brain's regulation of GM can be

achieved either directly or indirectly by altering the intestinal

environment (80). The nervous

system regulates the secretion of gastric acid, mucus, bicarbonate,

intestinal peptides, and antimicrobial peptides through intestinal

cuprocytes, and influences the thickness and quality of the

intestinal mucus layer (81). In

addition, physiological changes in the gut can alter the microbial

habitat, thus regulating the composition and activity of the

microbial community (82). It has

also been found that Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium are positively correlated with serum leptin,

while Clostridium, Prevotella and Bacteroides

are negatively correlated with leptin levels (83). ObRb, as a receptor in the brainstem

nervous system, inhibits the release of 5-HT and the expression of

5-HT receptor 2C in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus upon

binding to leptin. Activation of the β2-adrenergic receptor on OBs

promotes bone resorption (84).

Conversely, when leptin concentrations decrease, the release of

5-HT is diminished, leading to a reduction in sympathetic activity,

which affects the homeostasis of BM. 5-HT, as a neurotransmitter,

has been confirmed to regulate BM function through the

gastrointestinal system (85).

Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 has been identified as the enzyme

catalyzing serotonin synthesis, and its inhibitors hold potential

therapeutic utility in the treatment of low bone mass (86). It has been revealed through

knockdown of the serotonin receptor gene in OBs that a variety of

serotonin receptors can be expressed in these cells (87,88). A

correlation between serotonin levels and BM in women has been

observed, in which increased serotonin levels were accompanied by

decreased bone formation and increased bone turnover (89).

During the metabolic process of an organism, the GM

can produce numerous active substances, such as SCFAs,

hypocholestatic acid, TMAO, indole derivatives, and polyamines.

These metabolites are relatively stable and can diffuse into the

body circulation through the intestinal tract, thereby indirectly

revealing the role of the GM on BM (90). SCFAs are saturated fatty acids with

a chain length of one to six carbon atoms, which are metabolized

from the fermentation of indigestible carbohydrates by GM,

including acetate, propionate, and butyrate (91). Additionally, the fermentation of

amino acids in GM also produces SCFAs, which were found to inhibit

the activity of histone deacetylase, induce the generation of

Tregs, and maintain the immune system. By binding to G

protein-coupled receptors (GPRs) on the cell surface, particularly

free fatty acid receptor 2, SCFAs have been shown to reduce

intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels, activate the

immune system, promote the proliferation and differentiation of

Tregs, inhibit intestinal inflammation and OC differentiation, and

regulate BM (92). SCFAs were shown

to induce the development of peripheral Tregs by acting through

GPR43 (acetate and propionate receptors). Additionally, the

precursor OCs derived from differentiated bone marrow cells express

GPR41 (propionate and butyrate receptors) and GPR109 (butyrate and

nicotinic receptors), confirming that SCFAs affect OB and OC

activity through GPR activation (93). SCFAs in tryptophan, such as

butyrate, acetate, propionate, and indole, were revealed to promote

muscle synthesis, inhibit catabolism, exhibit anti-inflammatory and

antioxidant effects, and regulate BM, thereby helping to prevent OP

(94). SCFAs can directly act on

bone cells, increasing bone density and bone strength (95). Experiments have demonstrated that

SCFAs can increase bone density and bone strength in mice. Under

pathological conditions (such as inflammation), a reduction in gut

probiotic populations in mice has been observed, leading to a

reduction in SCFAs levels, which contributes to the onset of OP

(96). SCFAs can also lower

intestinal pH, reducing the formation of inorganic salts such as

calcium phosphate that bind to calcium ions. In addition, SCFAs

have been shown to selectively increase the phosphorylation of

mitogen-activated protein kinase p38, which mediates the

phosphorylation of the downstream substrate heat shock protein 27

at Ser78 and Ser82, thereby affecting the absorption of minerals

and improving bone quality (97).

SCFAs have also been demonstrated to induce metabolic reprogramming

of OBs, resulting in enhanced glycolysis at the expense of

oxidative phosphorylation, thereby downregulating essential OC

genes to directly inhibit OC activity (98).

Bile acids, serving as metabolites of cholesterol,

are synthesized and secreted by hepatocytes. Within this process,

95% of bile acids enter the gut-liver axis. Under the influence of

GM, primary bile acids can be converted into secondary bile acids,

such as lithocholic acid, and deoxycholic acid (99). GM contributes to the processing and

metabolism of bile acids, and metabolism regulates BM mainly

through the sphincter farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and GPRs (100). LPS, a distinctive chemical

component of the outer membrane layer of Gram-negative bacteria,

can cause a chronic inflammatory response, promoting OC formation

and inducing bone loss (101).

In vitro experiments found that LPS inhibited RANKL activity

by reducing the expression of RANK and M-CSF receptor and

stimulated osteoclastogenesis in RANKL-pretreated cells via TNF-α

(102). Lactic acid significantly

reduced TNF-α and IL-6 production in LPS-stimulated macrophages,

thereby decreasing the release of RANKL from OBs and inhibiting the

differentiation of bone marrow-derived macrophages to OCs (103).

As an important stage in drug absorption, the

progression of GM is closely associated with OP and its variations

in metabolites. With deepening research, the efficacy of

traditional Chinese medicine in preventing and treating OP through

the modulation of GM, has been highlighted. Single-flavor Chinese

medicinal herbs and their active ingredients, as well as herbal

compounds, play an anti-inflammatory role, enhance the mucous

barrier, improve the immune system, and regulate metabolism

(104-134).

Specific mechanisms are detailed in Table SI.

Glycosylation in the structure of total flavonoids

of Epimedii folium affects the number and activity of GM, which in

turn increases the thickness of bone trabeculae, elevates bone

mineral density, enhances OB activity, and promotes calcium

deposition (104). Fructus

Ligustri Lucid has been shown to promote the generation of

SCFAs, and regulate calcium absorption and calcium homeostasis by

upregulating the serum levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and

vitamin D-dependent calcium transporter gene expression (128,129). Fructus Ligustri Lucidi

aqueous extract may preserve bone quality through regulation of the

calcium balance and intestinal SCFA production in ovariectomized

rats (130). Traditional herbal

formula Gushukang (GSK) was clinically applied to treat primary

osteoporosis. GSK exerted beneficial effects on trabecular bone of

ovariectomized mice by improving calcium homeostasis through

regulation of paracellular calcium absorption in the duodenum and

transcellular calcium reabsorption in the kidney (131).

Puerarin has been demonstrated to repair intestinal

mucosal integrity by regulating the species and abundance of GM,

increasing the levels of tight junction proteins (ZO-1 and occludin

and their related mRNAs), and decreasing the release of

inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, LPS and their related

mRNAs). Concurrently, it was shown to increase the content of SCFAs

in the colon, influencing host metabolic pathways with

anti-inflammatory responses, such as amino acid metabolism, lipid

metabolism and butyrate. This action was revealed to maintain

intestinal homeostasis, alleviate inflammatory responses, and exert

anti-osteoporotic effects (112).

Berberine has been shown to enhance the intestinal barrier function

by upregulating butyrate production from GM, ameliorate both

systemic and local inflammation, and prevent alveolar bone loss

associated with estrogen deficiency (115).

The aqueous extract of Epimedii folium has been

shown to increase the abundance of Candidatus Saccharimonas.

It was demonstrated to be positively correlated with the production

of T-cell cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-10 and IFN-γ) by mesenteric

lymphocytes (132). Lycium

barbarum polysaccharide has been shown to promote the

production of SCFAs by adjusting the structure of GM (110). Among them, butyric acid was

demonstrated to increase the number of Tregs in both intestine and

bone marrow, which in turn activated the Wnt signaling pathway in

OBs and stimulated osteogenesis (133). Jian Gu granule effectively

prevented bone loss and enhanced bone strength by restoring the

abundance of GM, increasing the levels of SCFAs, reducing the

permeability of colonic epithelium, increasing the proportion of

Tregs in the spleen, and altering cytokines associated with bone

immunomodulation (120).

The aqueous extract of Epimedii folium can improve

the ratio of dominant flora, such as Muribaculaceae and

Lactobacillus, and regulate the level of parathyroid hormone

in the body, which affects BM (104). Eucommia ulmoides extract

was shown to change the composition of intestinal microbiota and

enhance the production of SCFAs, thereby improving OP (106). Extracts of Sambucus

williamsii Hance, administered at a dose of 140 mg/kg,

significantly reduced the abundance of Ruminococcaceae

UGC-014, inhibited the synthesis of 5-HT, and increased bone

density (134).

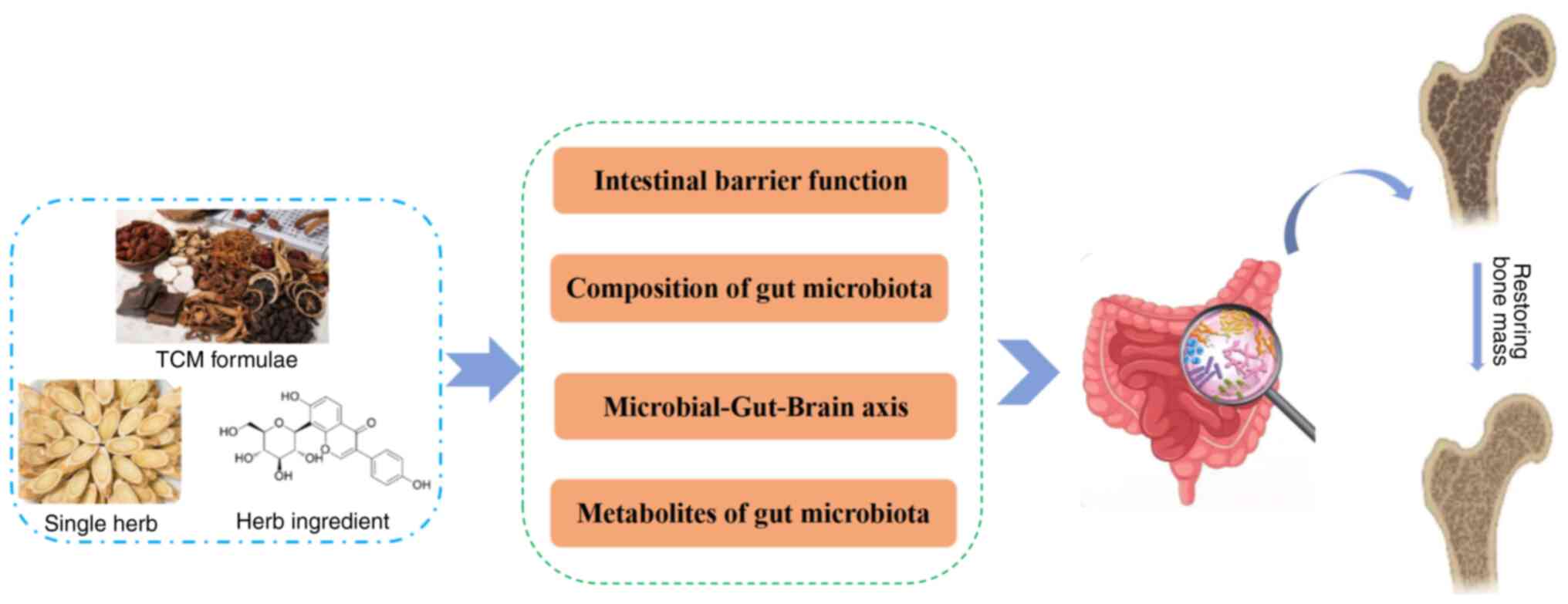

In conclusion, herbal combinations, single-flavor

herbs, their extracts, and herbal monomers regulate the intestinal

microbiota and their metabolic homeostasis, thereby exerting an

anti-OP effect, as shown in Fig. 3.

Although numerous studies on this subject have been conducted, the

current understanding is limited to the association between the GM

and the herbal medicines or active ingredients. Specific strains of

microorganisms, genes, or metabolic enzymes involved remain

unidentifiable. Therefore, it is still necessary to employ

multi-omics technologies to elucidate the mechanism by which

Chinese medicines act on which intestinal microorganisms to exert

their therapeutic effects, and then to elucidate the metabolic

mechanism of Chinese medicines in the intestinal tract of patients

with OP in subsequent studies.

Research focusing on targeting the GM for the

treatment of OP has emerged as a hot topic. Studies have

demonstrated that interventions such as fecal microbiota

transplantation (FMT), probiotic and prebiotic supplementation, or

dietary modification can improve the composition of the GM. These

changes not only modulate local processes, but also systemic

responses, including BM, affecting host metabolism, the immune

system, and hormone secretion (135-175),

as shown in Table SII.

Probiotics are a group of active microorganisms that

colonize the intestinal tract and reproductive system. They confer

benefits on the host, producing precise health effects and

contributing to the microecological balance of the host (151). The regulation of OP by probiotics

represents an emerging field, where the mechanisms underlying their

enhancement to BM, prevention, and treatment of OP have become a

focal point in BM research, yielding certain advancements. Research

indicates that probiotics can maintain skeletal health by

inhibiting bone resorption, promoting bone formation and

mineralization, enhancing bone density and improving bone

microstructure (152). The

specific mechanisms include: i) Increasing calcium content in bone:

Feeding hens with Bacillus subtilis significantly increased

the calcium content of the tibia in hens (153) and prevented the reduction of bone

mass in chicks caused by Salmonella enteritidis infection

(154). ii) Inhibition of OC

activity: Under estrogen deficiency, Lactobacillus reuteri

ATCC PTA 6475 exerted a protective effect by reducing bone loss,

bone resorption markers and osteoclastogenesis (28). Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC PTA

6475 inhibited bone resorption and TNF-α production, and

significantly improved bone density in male mice, suggesting that

the effect of bone regulation may be related to sex (139). iii) Inhibition of inflammatory

response to reduce bone resorption: Mice were treated with

Lactobacillus paracasei DSM13434 and the amount of cortical

bone mineral content was increased, while the serum levels of bone

resorption marker C-terminal telopeptides and the urinary

fractional excretion of calcium were reduced (137). Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG

and probiotic supplement VSL #3 have been demonstrated to reduce

intestinal permeability and inhibit intestinal inflammation,

thereby preventing estrogen deficiency-induced bone loss (26). iv) Promoting OB activity:

Lactobacillus reuteri attenuated bone loss in type 1

diabetic mice by regulating GM, preventing the decline in

osteocalcin levels and mineralization deposition rates, suggesting

a positive effect of probiotics on osteoanabolism (30). v) Bifidobacterium longum

increased the bone mineral content in rats during experimental

trials (155). Lactobacillus

rhamnosus stimulated the secretion of insulin-like growth

factor, which in turn promoted bone mineralization (140). vi) Regulation of BM pathways:

Lactobacillus rhamnosus promoted the maturation and

differentiation of OB and osteocytes by upregulating the expression

of genes associated with the mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 and

3 pathway (156). In addition,

Bifidobacterium longum increased bone mineral density by

upregulating the expression of SPARC and Bmp-2 genes (157).

Prebiotics are a class of indigestible food

ingredients, mainly non-digestible oligosaccharides, including

isomaltooligosaccharides, inulin, oligofructose, soybean

oligosaccharides, lactuloses, and pyrodextrins. They can

selectively stimulate the growth of one or more types of intestinal

flora, which can be utilized by GM, and promote the health of the

host (158). It has been found

that prebiotics can promote the absorption of mineral elements,

increase bone mineralization and enhance bone density (152). i) Promoting calcium absorption:

Galactooligosaccharides increased the population of

Bifidobacteria in the gut, which was conducive to the

utilization of calcium and magnesium, thus improving bone mass

(145). A three-week oral

administration of galactooligosaccharides to adolescent females

significantly increased the proportion of intestinal

Bifidobacteria and the rate of calcium absorption (141). Agave fructans were shown to

promote the absorption of minerals in the intestinal tract, and

improve the content of bone minerals (144). In addition, oligofructose

effectively promoted calcium absorption in rats fed a high-calcium

diet (147). ii) Influence on bone

conversion: The combination of lactulose

galactooligosaccharides/oligofructose with calcium supplementation

has been shown to elevate bone mineralization, bone mineral

density, and increase the surface area of OBs in rats (159). Calcium supplementation combined

with short-chain fructooligosaccharides has been shown to mitigate

the rate of systemic and spinal bone loss in postmenopausal women

(160). iii) Improvement of bone

strength: Galactooligosaccharides, oligofructose, and inulin have

demonstrated bone-strengthening effects in both healthy and

ovariectomized rats (161,162). iv) Enhancement of other bone

health agents: The synergistic prebiotic combination of

fructo-oligosaccharide and soy isoflavones was shown to improve the

bone strength of ovariectomized rats. The prebiotic mixture had a

more pronounced enhancement in bone strength when soy isoflavone

content was relatively low, underscoring that this prebiotic blend

can yield synergistic effects. These effects enhanced the efficacy

of prebiotics, with superior bone-strengthening outcomes compared

with the use of prebiotics alone (152). Therefore, prebiotics play an

important role in regulating GM and maintaining bone

homeostasis.

FMT is the transfer of GM from a healthy donor to

an intestinal dysbiosis recipient, aiming to restore intestinal

microbial homeostasis and ameliorate intestinal dysbiosis (163). A significant increase in bone mass

was observed 4 weeks after GFM received FMT using cecal contents

from conventionally housed mice (12). Additionally, the bones of

conventional mice chronically infused with broad-spectrum

antibiotics reproduced the phenotype of GFM (164). The transplantation of fecal

bacteria from osteoporotic mice into normal mice resulted in a

significant decrease in the bone mass of the recipient (61). Transplantation of fecal bacteria

from young rats into aged rats improved intestinal homeostasis at

the portal and familial levels, while increasing the bone volume,

trabecular volume fraction, trabecular number, and trabecular

thickness in aged rats. This phenomenon suggests the direct

influence of that GM on BM within the organism (57). The transplantation of segmented

filamentous bacteria into GFM increased the number of Th17 cells,

leading to increased levels of IL-17, TNF-α, and IL-1, and induced

the expression of RANKL, thereby promoting osteoclastogenesis

(165). The transplantation of

Clostridium clusters IV and XIVa, which were isolated from

mice, into GFM resulted in an increase in the number of systemic

and lamina propria Tregs (166).

SCFAs also induced the differentiation of Tregs, which regulated

osteoclastogenesis through the secretion of IL-4, IL-10, and TGF-β

(167). Malnutrition in infants

and young children has been shown to lead to the dysbiosis of the

GM, subsequently disrupting the maturation of the immune system and

the normal growth of the skeletal system. It was demonstrated that

the transplantation of the GM from malnourished children into

healthy mice resulted in a significant reduction in bone mass over

time (168). Animal experiments

have shown that bone mass and immune factor levels are restored to

normal through metabolites and immunomodulation when GM is

transplanted into germ-free or depleted mice (12). Certainly, the adverse effects caused

by the allochthonous enterobacteria post-transplantation, as well

as the compliance issue arising from the differences in

administration routes between the upper and lower gastrointestinal

tract, remain areas for improvement and consideration. Long-term

and effective FMT therapy may radically improve the diversity of GM

in patients and become an effective method to treat OP (169).

Dietary structure can influence the type of GM and

the function of the gut. Low dietary fibre intake may disrupt the

integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier, causing a relative

increase in the levels of Firmicutes and

Proteobacteria and a relative decrease in the levels of

Bacteroidetes in the intestines of dietary fibre-deficient

mice (170). A previous study

indicated that Tanzanian hunter-gatherers, and Malawian and

Venezuelan farmers consuming agri-foods had a greater diversity of

flora than populations from the United States (171). Higher dietary fibre consumption

may exert a positive influence on the progression of OP by altering

the structural composition of GM (172). High-fibre diets and oligofructose

may increase the number of Bifidobacterium species, optimize

the microbial composition of the GM, increase the content of SCFAs,

and lower the pH in the gut, thus promoting calcium absorption.

Dairy consumption encourages bone formation and inhibits bone

resorption (173). Studies have

also found that consumption of dairy products by adults aged 60

years and above can reduce the risk of OP. This beneficial effect

is partly attributed to the lactulose content of lactulose

derivatives. This interaction is capable of lowering serum

parathyroid hormone levels, thereby decreasing levels of bone

resorption markers (174,175).

GM is closely related to the occurrence and

development of OP and related metabolic diseases. Treating OP by

improving GM and its metabolites has been a hot and challenging

topic in medical research in recent years. On one hand, the GM can

directly or indirectly participate in bone mass regulation by

modulating host metabolism, calcium absorption, hormone levels, the

immune system, and the central nervous system. On the other hand,

GM-associated metabolites can also reliably and effectively reflect

the impact of GM on BM, potentially serving as novel targets for

the prevention and treatment of OP. The present review summarized

that TCM, probiotics, and prebiotics can ameliorate the composition

of GM and promote microbial-metabolite balance by regulating the

‘gut-bone axis’, thereby exerting therapeutic effects against OP.

These findings provide theoretical support and reference for

clinical treatment of OP and the development of innovative

therapeutic agents.

Currently, TCM has demonstrated potential in

treating OP by regulating GM. However, several challenges and

limitations remain in its practical applications: i) Research

primarily relies on laboratory animal studies, lacking high-quality

clinical trials to objectively reflect TCM clinical efficacy and

clarify its mechanisms of action; ii) TCM interventions in OP

studies often focus on single signaling pathways, failing to

systematically elucidate multi-pathway interactions; iii) Research

on GM profiles has primarily focused on common bacterial

communities, lacking studies on the mechanisms underlying complex

microbial interactions; and iv) The therapeutic effects of TCM on

OP currently remain confined to the levels of marker

microorganisms, microbial diversity, and differential metabolic

products, making it difficult to elucidate the biotransformation

processes of herbal active components through GM. Therefore,

further investigation is still required to elucidate how TCM

optimizes the structure and function of the host GM, how the host

GM converts the active components of TCM into metabolites that act

on target organs, and the mechanisms by which microbial metabolites

exert biological effects on the host. Moreover, research should

leverage modern molecular biology techniques, such as

macro-genomics, functional genomics and metabolomics, to elucidate

the mechanisms of TCM treatment for OP from a multi-component,

multi-target, and holistic regulatory perspective. Simultaneously,

techniques such as FMT, supplementation of deficient microbiota and

metabolites, and co-incubation of TCM with GM should be employed to

bridge the gap in understanding the ‘TCM active

components-GM-microbial metabolites’ interaction pathway.

Furthermore, it is imperative to enhance clinical trials to

substantiate the efficacy and safety of these treatments, while

methodologies such as molecular dynamic simulations should be

employed to identify critical therapeutic targets of TCM in the

treatment of OP.

As awareness of the impact of GM on health grows,

an increasing number of studies are focusing on the relationship

between gut microbial metabolism and BM. Regulating GM through

supplementation with probiotics and prebiotics to improve BM has

emerged as a new therapeutic target for OP. However, whether

moderate supplementation of prebiotics or probiotics is effective

in humans needs to be supported by large-scale multi-centre

clinical studies. In addition, it remains to be elucidated whether

the effects of different types of prebiotics or probiotics are

consistent, the differential effects of age, sex, and etiology on

the efficacy of OP as well as the optimal dosage, duration of

treatment, timing of initiation and cessation, and the specific

mechanisms underlying their actions. FMT as a treatment for

Clostridium infection has become more mature, but there are

still some unresolved problems in the treatment of OP. Therefore,

in clinical practice, the use of enterobacterial preparations

administered via capsule for transplantation can improve patient

compliance and reduce adverse reactions. Timely and long-term FMT

in patients with OP can fundamentally improve their GM composition

and intestinal barrier function, potentially emerging as an

effective therapeutic approach for OP in clinical treatment.

In summary, future research should focus on the

core area of the mechanisms by which GM and their metabolites treat

OP. By skillfully integrating cutting-edge technologies such as

artificial intelligence, genomics, and high-throughput screening,

and closely aligning with clinical practice needs, this approach

aims to lay a solid foundation for exploring and innovating anti-OP

treatment strategies.

Not applicable.

Funding: The present review was supported by the Yunnan

Provincial Science and Technology Department of the Chinese

Medicine Research Center [grant no. 2018FF001(-085)].

Not applicable.

MA and XL contributed equally to this article, and

they drafted the manuscript. CX, YL, YZ, RC reviewed the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Clynes MA, Harvey NC, Curtis EM, Fuggle

NR, Dennison EM and Cooper C: The epidemiology of osteoporosis. Br

Med Bull. 133:105–117. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Harris K, Zagar CA and Lawrence KV:

Osteoporosis: Common questions and answers. Am Fam Physician.

107:238–246. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rachner TD, Khosla S and Hofbauer LC:

Osteoporosis: Now and the future. Lancet. 377:1276–1287.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki

EM, Tanner B, Randall S and Lindsay R: National Osteoporosis

Foundation. Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of

osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 25:2359–2381. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Health Quality Ontario. Vertebral

augmentation involving vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty for

cancer-related vertebral compression fractures: A systematic

review. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 16:1–202. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Brzozowska MM, Sainsbury A, Eisman JA,

Baldock PA and Center JR: Bariatric surgery, bone loss, obesity and

possible mechanisms. Obes Rev. 14:52–67. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Goulet O: Potential role of the intestinal

microbiota in programming health and disease. Nutr Rev. 73 (Suppl

1):S32–S40. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Maynard CL, Elson CO, Hatton RD and Weaver

CT: Reciprocal interactions of the intestinal microbiota and immune

system. Nature. 489:231–241. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf

KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, et al: A

human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic

sequencing. Nature. 464:59–65. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Costea PI, Hildebrand F, Arumugam M,

Bäckhed F, Blaser MJ, Bushman FD, de Vos WM, Ehrlich SD, Fraser CM,

Hattori M, et al: Enterotypes in the landscape of gut microbial

community composition. Nat Microbiol. 3:8–16. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kau AL, Ahern PP, Griffin NW, Goodman AL

and Gordon JI: Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune

system. Nature. 474:327–336. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Sjögren K, Engdahl C, Henning P, Lerner

UH, Tremaroli V, Lagerquist MK, Bäckhed F and Ohlsson C: The gut

microbiota regulates bone mass in mice. J Bone Miner Res.

27:1357–1367. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ohlsson C and Sjögren K: Effects of the

gut microbiota on bone mass. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 26:69–74.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Espinoza JL, Elbadry MI and Nakao S: An

altered gut microbiota may trigger autoimmune-mediated acquired

bone marrow failure syndromes. Clin Immunol. 171:62–64.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Fransen F, van Beek AA, Borghuis T, Aidy

SE, Hugenholtz F, van der Gaast-de Jongh C, Savelkoul HFJ, De Jonge

MI, Boekschoten MV, Smidt H, et al: Aged gut microbiota contributes

to systemical inflammaging after transfer to germ-free mice. Front

Immunol. 8(1385)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Lerner A, Neidhöfer S and Matthias T: The

gut microbiome feelings of the brain: A perspective for

non-microbiologists. Microorganisms. 5(66)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

McCabe L, Britton RA and Parameswaran N:

Prebiotic and probiotic regulation of bone health: Role of the

intestine and its microbiome. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 13:363–371.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Villa CR, Ward WE and Comelli EM: Gut

microbiota-bone axis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 57:1664–1672.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Donohoe DR, Garge N, Zhang X, Sun W,

O'Connell TM, Bunger MK and Bultman SJ: The microbiome and butyrate

regulate energy metabolism and autophagy in the mammalian colon.

Cell Metab. 13:517–526. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Weaver CM: Diet, gut microbiome, and bone

health. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 13:125–130. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Anantharaju A and Klamut M: Small

intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A possible risk factor for

metabolic bone disease. Nutr Rev. 61:132–135. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Stotzer PO, Johansson C, Mellström D,

Lindstedt G and Kilander AF: Bone mineral density in patients with

small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Hepatogastroenterology.

50:1415–1418. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ma S, Qin J, Hao Y and Fu L: Association

of gut microbiota composition and function with an aged rat model

of senile osteoporosis using 16s rrna and metagenomic sequencing

analysis. Aging (Albany NY). 12:10795–10808. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ma S, Qin J, Hao Y, Shi Y and Fu L:

Structural and functional changes of gut microbiota in

ovariectomized rats and their correlations with altered bone mass.

Aging (Albany NY). 12:10736–10753. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Lin H, Liu T, Li X, Gao X, Wu T and Li P:

The role of gut microbiota metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide in

functional impairment of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in

osteoporosis disease. Ann Transl Med. 8(1009)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Li JY, Chassaing B, Tyagi AM, Vaccaro C,

Luo T, Adams J, Darby TM, Weitzmann MN, Mulle JG, Gewirtz AT, et

al: Sex steroid deficiency-associated bone loss is microbiota

dependent and prevented by probiotics. J Clin Invest.

126:2049–2063. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Nzakizwanayo J, Dedi C, Standen G,

Macfarlane WM, Patel BA and Jones BV: Escherichia coli nissle 1917

enhances bioavailability of serotonin in gut tissues through

modulation of synthesis and clearance. Sci Rep.

5(17324)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Britton RA, Irwin R, Quach D, Schaefer L,

Zhang J, Lee T, Parameswaran N and McCabe LR: Probiotic l. Reuteri

treatment prevents bone loss in a menopausal ovariectomized mouse

model. J Cell Physiol. 229:1822–1830. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zhang J, Motyl KJ, Irwin R, MacDougald OA,

Britton RA and McCabe LR: Loss of bone and wnt10b expression in

male type 1 diabetic mice is blocked by the probiotic lactobacillus

reuteri. Endocrinology. 156:3169–3182. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

He J, Xu S, Zhang B, Xiao C, Chen Z, Si F,

Fu J, Lin X, Zheng G, Yu G and Chen J: Gut microbiota and

metabolite alterations associated with reduced bone mineral density

or bone metabolic indexes in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Aging

(Albany NY). 12:8583–8604. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Wang J, Wang Y, Gao W, Wang B, Zhao H,

Zeng Y, Ji Y and Hao D: Diversity analysis of gut microbiota in

osteoporosis and osteopenia patients. PeerJ.

5(e3450)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Huang R, Liu P, Bai Y, Huang J, Pan R, Li

H, Su Y, Zhou Q, Ma R, Zong S and Zeng G: Changes in the gut

microbiota of osteoporosis patients based on 16SrRNA gene

sequencing:a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Zhejiang Univ

Sci B. 23:1002–1022. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Li C, Huang Q, Yang R, Dai Y, Zeng Y, Tao

L, Li X, Zeng J and Wang Q: Gut microbiota composition and bone

mineral loss-epidemiologic evidence from individuals in Wuhan,

China. Osteoporos Int. 30:1003–1013. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Sun M, Liu Y, Tang S, Li Y, Zhang R and

Mao L: Characterization of intestinal flora in osteoporosis

patients based on 16S rDNA sequencing. Int J Gen Med. 17:4311–4324.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Das M, Cronin O, Keohane DM, Cormac EM,

Nugent H, Nugent M, Molloy C, O'Toole PW, Shanahan F, Molloy MG and

Jeffery IB: Gut microbiota alterations associated with reduced bone

mineral density in older adults. Rheumatology (Oxford).

58:2295–2304. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Ling CW, Miao ZL, Xiao ML, Zhou H, Jiang

Z, Fu Y, Xiong F, Zuo LS, Liu YP, Wu YY, et al: The association of

gut microbiota with osteoporosis is mediated by amino acid

metabolism: multiomics in a large cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

106:e3852–e3864. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Ni JJ, Yang XL, Zhang H, Xu Q, Wei XT,

Feng GJ, Zhao M, Pei YF and Zhang L: Assessing causal relationship

from gut microbiota to heel bone mineral density. Bone.

143(115652)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Zeng HQ, Li G, Zhou KX, Li AD, Liu W and

Zhang Y: Causal link between gut microbiota and osteoporosis

analyzed via Mendelian randomization. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci.

28:542–555. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Wei M, Li C, Dai Y, Zhou H, Cui Y, Zeng Y,

Huang Q and Wang Q: High-throughput absolute quantification

sequencing revealed osteoporosis-related gut microbiota alterations

in Han Chinese elderly. Front Cell infect Microbiol.

11(630372)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Rettedal EA, Ilesanmi-Oyelere BL, Roy NC,

Coad J and Kruger MC: The gut microbiome is altered in

postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and osteopenia. JBMR Plus.

5(e10452)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Yang X, Chang T, Yuan Q, Wei W, Wang P,

Song X and Yuan H: Changes in the composition of gut and vaginal

microbiota in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Front

Immunol. 13(930244)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Xu X, Jia X, Mo L, Liu C, Zheng L, Yuan Q

and Zhou X: Intestinal microbiota: A potential target for the

treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Bone Res.

5(17046)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Kuo YJ, Chen CJ, Hussain B, Tsai HC, Hsu

GJ, Chen JS, Asif A, Fan CW and Hsu BM: Inferring associated with

osteopenia and osteoporosis in Taiwanese postmenopausal bacterial

community interactions and functionalities women. Microorganisms.

11(234)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Zhang YW, Li YJ, Lu PP, Dai GC, Chen XX

and Rui YF: The modulatory effect and implication of gut microbiota

on osteoporosis: from the perspective of ‘brain-gut-bone’ axis.

Food Funct. 12:5703–5718. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Li K, Jiang Y, Wang N, Lai L, Xu S, Xia T,

Yue X and Xin H: Traditional Chinese medicine in osteoporosis

intervention and the related regulatory mechanismof gut microbiome.

Am J Chin Med. 51:1957–1981. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Report of the dietary guidelines advisory

committee dietary guidelines for americans, 1995. Nutr Rev.

53:376–379. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Hirata Y, Egea L, Dann SM, Eckmann L and

Kagnoff MF: Gm-csf-facilitated dendritic cell recruitment and

survival govern the intestinal mucosal response to a mouse enteric

bacterial pathogen. Cell Host Microbe. 7:151–163. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Ohta A, Motohashi Y, Sakai K, Hirayama M,

Adachi T and Sakuma K: Dietary fructooligosaccharides increase

calcium absorption and levels of mucosal calbindin-d9k in the large

intestine of gastrectomized rats. Scand J Gastroenterol.

33:1062–1068. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Raveschot C, Coutte F, Frémont M,

Vaeremans M, Dugersuren J, Demberel S, Drider D, Dhulster P,

Flahaut C and Cudennec B: Probiotic lactobacillus strains from

mongolia improve calcium transport and uptake by intestinal cells

in vitro. Food Res Int. 133(109201)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Rillaerts K, Verlinden L, Doms S,

Carmeliet G and Verstuyf A: A comprehensive perspective on the role

of vitamin D signaling in maintaining bone homeostasis: Lessons

from animal models. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol.

250(106732)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Lin HR, Xu F, Chen D, Xie K, Yang Y, Hu W,

Li BY, Jiang Z, Liang Y, Tang XY, et al: The gut microbiota-bile

acid axis mediates the beneficial associations between plasma

vitamin d and metabolic syndrome in chinese adults: A prospective

study. Clin Nutr. 42:887–898. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Castaneda M, Strong JM, Alabi DA and

Hernandez CJ: The gut microbiome and bone strength. Curr Osteoporos

Rep. 18:677–683. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Schoultz I and Keita ÅV: The intestinal

barrier and current techniques for the assessment of gut

permeability. Cells. 9(1909)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Cardoso-Silva D, Delbue D, Itzlinger A,

Moerkens R, Withoff S, Branchi F and Schumann M: Intestinal barrier

function in gluten-related disorders. Nutrients.

11(2325)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Smith BJ, Lerner MR, Bu SY, Lucas EA,

Hanas JS, Lightfoot SA, Postier RG, Bronze MS and Brackett DJ:

Systemic bone loss and induction of coronary vessel disease in a

rat model of chronic inflammation. Bone. 38:378–386.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Park OJ, Kim J, Yang J, Yun CH and Han SH:

Muramyl dipeptide, a shared structural motif of peptidoglycans, is

a novel inducer of bone formation through induction of Runx2. J

Bone Miner Res. 34(975)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Ma S, Wang N, Zhang P, Wu W and Fu L:

Fecal microbiota transplantation mitigates bone loss by improving

gut microbiome composition and gut barrier function in aged rats.

PeerJ. 9(e12293)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Xiao HH, Lu L, Poon CC, Chan CO, Wang LJ,

Zhu YX, Zhou LP, Cao S, Yu WX, Wong KY, et al: The lignan-rich

fraction from sambucus williamsii hance ameliorates dyslipidemia

and insulin resistance and modulates gut microbiota composition in

ovariectomized rats. Biomed Pharmacother.

137(111372)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

AlQranei MS, Senbanjo LT, Aljohani H,

Hamza T and Chellaiah MA: Lipopolysaccharide-tlr-4 axis regulates

osteoclastogenesis independent of rankl/rank signaling. BMC

Immunol. 22(23)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Yuan S and Shen J: Bacteroides vulgatus

diminishes colonic microbiota dysbiosis ameliorating lumbar bone

loss in ovariectomized mice. Bone. 142(115710)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Schepper JD, Collins F, Rios-Arce ND, Kang

HJ, Schaefer L, Gardinier JD, Raghuvanshi R, Quinn RA, Britton R,

Parameswaran N and McCabe LR: Involvement of the gut microbiota and

barrier function in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. J Bone

Miner Res. 35:801–820. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Locantore P, Del Gatto V, Gelli S,

Paragliola RM and Pontecorvi A: The interplay between immune system

and microbiota in osteoporosis. Mediators Inflamm.

2020(3686749)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Cline-Smith A, Axelbaum A, Shashkova E,

Chakraborty M, Sanford J, Panesar P, Peterson M, Cox L, Baldan A,

Veis D and Aurora R: Ovariectomy activates chronic low-grade

inflammation mediated by memory T cells, which promotes

osteoporosis in mice. J Bone Miner Res. 35:1174–1187.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Tsukasaki M and Takayanagi H:

Osteoimmunology: Evolving concepts in bone-immune interactions in

health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 19:626–642. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Charles JF and Nakamura MC: Bone and the

innate immune system. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 12:1–8. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Hao ML, Wang GY, Zuo XQ, Qu CJ, Yao BC and

Wang DL: Gut microbiota: An overlooked factor that plays a

significant role in osteoporosis. J Int Med Res. 47:4095–4103.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Uluçkan Ö, Jimenez M, Karbach S, Jeschke

A, Graña O, Keller J, Busse B, Croxford AL, Finzel S, Koenders M,

et al: Chronic skin inflammation leads to bone loss by

il-17-mediated inhibition of wnt signaling in osteoblasts. Sci

Transl Med. 8(330ra37)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Quach D and Britton RA: Gut microbiota and

bone health. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1033:47–58. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Campbell JE and Drucker DJ: Pharmacology,

physiology, and mechanisms of incretin hormone action. Cell Metab.

17:819–837. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Mabilleau G: Incretins and bone: Friend or

foe? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 22:72–78. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Baker JM, Al-Nakkash L and

Herbst-Kralovetz MM: Estrogen-gut microbiome axis: Physiological

and clinical implications. Maturitas. 103:45–53. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Wang Y, Cheng Z, Elalieh HZ, Nakamura E,

Nguyen MT, Mackem S, Clemens TL, Bikle DD and Chang W: Igf-1r

signaling in chondrocytes modulates growth plate development by

interacting with the pthrp/ihh pathway. J Bone Miner Res.

26:1437–1446. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Guo X, Zhong K, Zhang J, Hui L, Zou L, Xue

H, Guo J, Zheng S, Huang D and Tan M: Gut microbiota can affect

bone quality by regulating serum estrogen levels. Am J Transl Res.

14:6043–6055. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Ren H, Sun R and Wang J: Relationship of

melatonin level, oxidative stress and inflammatory status with

osteoporosis in maintenance hemodialysis of chronic renal failure.

Exp Ther Med. 15:5183–5188. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Gilbert L, He X, Farmer P, Boden S,

Kozlowski M, Rubin J and Nanes MS: Inhibition of osteoblast

differentiation by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Endocrinology.

141:3956–3964. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Guo M, Liu H, Yu Y, Zhu X, Xie H, Wei C,

Mei C, Shi Y, Zhou N, Qin K and Li W: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG

ameliorates osteoporosis in ovariectomized rats by regulating the

Th17/Treg balance and gut microbiota structure. Gut Microbes.

15(2190304)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Yang X, Zhou F, Yuan P, Dou G, Liu X, Liu

S, Wang X, Jin R, Dong Y, Zhou J, et al: T cell-depleting

nanoparticles ameliorate bone loss by reducing activated T cells

and regulating the Treg/Th17 balance. Bioact Mater. 6:3150–3163.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Lorenzo J: From the gut to bone:

Connecting the gut microbiota with Th17 T lymphocytes and

postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Invest.

131(e146619)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Ohara TE and Hsiao EY:

Microbiota-neuroepithelial signalling across the gut-brain axis.

Nat Rev Microbiol. 23:371–384. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Mayer EA, Nance K and Chen S: The

gut-brain axis. Annu Rev Med. 73:439–453. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Hayes CL, Dong J, Galipeau HJ, Jury J,

McCarville J, Huang X, Wang XY, Naidoo A, Anbazhagan AN, Libertucci

J, et al: Commensal microbiota induces colonic barrier structure

and functions that contribute to homeostasis. Sci Rep.

8(14184)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Treangen TJ, Wagner J, Burns MP and

Villapol S: Traumatic brain injury in mice induces acute bacterial

dysbiosis within the fecal microbiome. Front Immunol.

9(2757)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Queipo-Ortuño MI, Seoane LM, Murri M,

Pardo M, Gomez-Zumaquero JM, Cardona F, Casanueva F and Tinahones

FJ: Gut microbiota composition in male rat models under different

nutritional status and physical activity and its association with

serum leptin and ghrelin levels. PLoS One. 8(e65465)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Yadav VK, Oury F, Suda N, Liu ZW, Gao XB,

Confavreux C, Klemenhagen KC, Tanaka KF, Gingrich JA, Guo XE, et

al: A serotonin-dependent mechanism explains the leptin regulation

of bone mass, appetite, and energy expenditure. Cell. 138:976–989.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Bliziotes M, Eshleman A, Burt-Pichat B,

Zhang XW, Hashimoto J, Wiren K and Chenu C: Serotonin transporter

and receptor expression in osteocytic MLO-Y4 cells. Bone.

39:1313–1321. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Yadav VK, Balaji S, Suresh PS, Liu XS, Lu

X, Li Z, Guo XE, Mann JJ, Balapure AK, Gershon MD, et al:

Pharmacological inhibition of gut-derived serotonin synthesis is a

potential bone anabolic treatment for osteoporosis. Nat Med.

16:308–312. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Chabbi-Achengli Y, Coudert AE, Callebert

J, Geoffroy V, Côté F, Collet C and de Vernejoul MC: Decreased

osteoclastogenesis in serotonin-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 109:2567–2572. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Westbroek I, van der Plas A, de Rooij KE,

Klein-Nulend J and Nijweide PJ: Expression of serotonin receptors

in bone. J Biol Chem. 276:28961–28968. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Mödder UI, Achenbach SJ, Amin S, Riggs BL,

Melton LJ III and Khosla S: Relation of serum serotonin levels to

bone density and structural parameters in women. J Bone Miner Res.

25:415–422. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Cummings JH and Macfarlane GT: The control

and consequences of bacterial fermentation in the human colon. J

Appl Bacteriol. 70:443–459. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Nagpal R, Kumar M, Yadav AK, Hemalatha R,

Yadav H, Marotta F and Yamashiro Y: Gut microbiota in health and

disease: An overview focused on metabolic inflammation. Benef

Microbes. 7:181–194. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Montalvany-Antonucci CC, Duffles LF, de

Arruda JAA, Zicker MC, de Oliveira S, Macari S, Garlet GP, Madeira

MFM, Fukada SY, Andrade I Jr, et al: Short-chain fatty acids and

FFAR2 as suppressors of bone resorption. Bone. 125:112–121.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M,

Gallini CA, Bohlooly-Y M, Glickman JN and Garrett WS: The microbial

metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell

homeostasis. Science. 341:569–573. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Feng B, Lu J, Han Y, Han Y, Qiu X and Zeng

Z: The role of short-chain fatty acids in the regulation of

osteoporosis: New perspectives from gut microbiota to bone health:

A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 103(e39471)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Charles JF, Ermann J and Aliprantis AO:

The intestinal microbiome and skeletal fitness: Connecting bugs and

bones. Clin Immunol. 159:163–169. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Lucas S, Omata Y, Hofmann J, Böttcher M,

Iljazovic A, Sarter K, Albrecht O, Schulz O, Krishnacoumar B,

Krönke G, et al: Short-chain fatty acids regulate systemic bone

mass and protect from pathological bone loss. Nat Commun.

9(55)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Yonezawa T, Kobayashi Y and Obara Y:

Short-chain fatty acids induce acute phosphorylation of the p38

mitogen-activated protein kinase/heat shock protein 27 pathway via

gpr43 in the mcf-7 human breast cancer cell line. Cell Signal.

19:185–193. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Li P, Ji B, Luo H, Sundh D, Lorentzon M

and Nielsen J: One-year supplementation with lactobacillus reuteri

atcc pta 6475 counteracts a degradation of gut microbiota in older

women with low bone mineral density. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes.

8(84)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Winston JA and Theriot CM: Diversification

of host bile acids by members of the gut microbiota. Gut Microbes.

11:158–171. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Zheng XQ, Wang DB, Jiang YR and Song CL:

Gut microbiota and microbial metabolites for osteoporosis. Gut

Microbes. 17(2437247)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Hernandez CJ, Guss JD, Luna M and Goldring

SR: Links between the microbiome and bone. J Bone Miner Res.

31:1638–1646. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Zou W and Bar-Shavit Z: Dual modulation of

osteoclast differentiation by lipopolysaccharide. J Bone Miner Res.

17:1211–1218. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Yang K, Xu J, Fan M, Tu F, Wang X, Ha T,

Williams DL and Li C: Lactate suppresses macrophage

pro-inflammatory response to LPS stimulation by inhibition of YAP

and NF-κB activation via GPR81-mediated signaling. Front Immunol.

11(587913)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Huang J, Yuan L, Wang X, Zhang TL and Wang

K: Icaritin and its glycosides enhance osteoblastic, but suppress

osteoclastic, differentiation and activity in vitro. Life Sci.

81:832–840. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Li L, Chen B, Zhu R, Tian Y, Liu C, Jia Q,

Wang L, Tang J, Zhao D, Mo F, et al: Fructus ligustri lucidi

preserves bone quality through the regulation of gut microbiota

diversity, oxidative stress, TMAO and sirt6 levels in aging mice.

Aging (Albany NY). 11:9348–9368. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

106

|

Zhao X, Wang Y, Nie Z, Han L, Zhong X, Yan

X and Gao X: Eucommia ulmoides leaf extract alters gut microbiota

composition, enhances short-chain fatty acids production, and

ameliorates osteoporosis in the senescence-accelerated mouse p6

(samp6) model. Food Sci Nutr. 8:4897–4906. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Zhao X, Ai J, Mao H and Gao X: Effects of