Introduction

Orchids belong to the family Orchidaceae, one of

largest families of flowering plant and the most diverse family

with >25,000 species in ~880 genera (1). Several orchids have been used for a

variety of purposes, including ornamental plants, sources of

natural antioxidants and bioactive compounds and for cosmeceutical

use (2). Dendrobium spp. is

a large genus with >1,000 species that can grow in a variety of

environments and as epiphytes in tropical and subtropical Asia and

eastern Australia (3). Several

Dendrobium species have been used in traditional medicine

due to the high number of bioactive compounds, such as polyphenols,

flavonoids, alkaloids and polysaccharides (3,4). These

compounds have key biological activities. For example, phenolics

and flavonoids exhibit antioxidant capacity, which could promote

human health and prevent chronic and degenerative diseases,

including cancer, caused by free radicals (5). D. crepidatum contains bibenzyl

derivatives, polyphenols and flavonoids that have antioxidant and

cytotoxic effects on cancer cells (6). D. denneanum and D.

nobile contain bioactive polysaccharides and exhibit

antioxidant properties (7,8).

Skin cancer is one of the most frequent malignancies

worldwide and can be classified into melanoma skin cancer (MSC) and

non-MSC (9). According to global

data from 2000 to 2024, MSC ranks 17th in prevalence and 23rd as a

leading cause of cancer-related death, with the highest incidence

and mortality rate reported in Europe. While Asia has the lowest

incidence rate of MSC, it records the second-highest mortality rate

(9). In humans, malignant melanoma

cells consist of activating mutations of B-RAF oncogene, resulting

in abnormal cell proliferation (10). The SK-MEL-28 cell line is a type of

human malignant melanoma cell and the most aggressive form of skin

cancer. The migration and invasion of melanoma cells are involved

with proteolytic enzymes such as serine and cysteine proteases and

matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) in remodeling dermal extracellular

matrix (ECM) (11). The ECM

comprises a large variety of macromolecules, including

fibrous-forming proteins (collagen and elastin) and carbohydrate

strings (proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans and glycoproteins), and

enzymes (proteinases and MMPs). Collagens are predominant and the

main targets for MMPs, especially collagenases, in ECM remodeling

(11,12). Also, the accumulation of hyaluronan

(HA), a polysaccharide subfamily of glycosaminoglycans, is

attributed to the progression and metastasis of cancer cells

(13). D. draconis, D.

falconeri, D. findlayanum and D. loddigesii have

been reported for their ability to inhibit the proliferation of

numerous types of cancer cell (14), including colon cancer (15) and leukemia (16). Most cancer cells are inhibited by

many pathways, including autophagy and apoptosis (both intrinsic

and extrinsic). Secondary metabolites, such as bibenzyl compounds

from D. loddigesii, induce apoptosis in melanoma cells

(17). In addition, the crude

extract and certain compounds isolated from Dendrobium have

been found to regulate the changes of expression of genes and

proteins involved in apoptosis, especially in the intrinsic pathway

(18-23).

The bcl-2 gene family is a key factor in the regulation of

cell apoptosis, including anti-apoptotic genes (bcl-2 and

bcl-XL) and pro-apoptotic genes (bax and bid)

(18). Some traditional Chinese

medicine anticancer drugs have been found to induce cell apoptosis

through targeting the proteins of the bcl-2 family and increasing

the ratio of bax to bcl-2 (19). D. officinale extracts

increase the protein levels of Bax and caspase-3 and decreased

Bcl-2 in extract-fed rats with gastric cancer (20). D. officinale extract

primarily contains polysaccharides, including mannose, which

exhibit anti-tumor activity and induce apoptosis in osteosarcoma

cells via caspase upregulation (21). Moreover, Nudol, a phenanthrene

derivative from D. nobile, notably enhances the mRNA

expression levels of cytc and caspases in

osteosarcoma cells (22).

Quercetin, a flavonoid compound commonly found in plant extracts,

exerts anti-cancer activity by inducing nuclear fragmentation and

intrinsic apoptosis via an increase in p53 expression

(23).

Our previous study investigated orchid hybrids that

were primarily created for horticultural purposes and found that

the propanolic extract from Dendrobium Pearl Vera [a

Dendrobium hybrid; DH-P] exhibited antioxidant activity and

could reduce melanin production and viability of melanoma SK-MEL-28

cells treated with phenolic contents at 15 µg/ml (24). To the best of our knowledge,

however, there are no published reports on the bioactive compounds

in such Dendrobium hybrids. Swainson et al (24) identified certain annotated bioactive

compounds using high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) coupled

with the Orbitrap (ion trap-based mass analyzer) using an

untargeted approach. Quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) is one of the

most popular mass analyzers used in analytical screening of

targeted and non-targeted substances due to its robustness, high

sensitivity and specificity. The present study aimed to identify

other bioactive compounds in the DH plant using QTOF and determine

the effects of DH-P on free radicals, enzyme activity involved in

ECM, cell migration and the mechanism of SK-MEL-28 cell death at

the gene level.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

The standards used for the HR-MS experiment were

quercetin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA; cat. no. Q4951), dendrobine

(Chengdu Biopurify Phytochemicals, Ltd.; cat. no. BP0479) and

gigantol (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA; cat. no. Sml2036). The human

melanoma cell line was SK-MEL-28 (American Type Culture Collection;

cat. no. HTB-72). Other chemicals, reagents and media used were

HPLC, analytical or molecular biology grade, as appropriate.

Preparation of DH-P

DH plants (a hybrid between Dendrobium Topaz

Dream and D. bigibbum; CordyBiotech Co., Ltd.) were cultured

in vitro for 3-4 months in Murashige and Skoog medium

(PhytoTech Labs; cat. no. M524) containing 6.8 g/l agar and 17 g/l

sucrose, at 25±2˚C under 300 lux light for 16 h/day. Whole plants

of DH were harvested and ground using liquid nitrogen. The ground

sample was extracted using 2-propanol with a ratio of 1:5 (w/v).

Samples were macerated at room temperature for 24 h. The filtrate

was collected through filter papers (Whatman plc; Cytiva; cat. no.

1001-090) and samples from three extractions were pooled. The

filtrate was concentrated using a rotary evaporator and

lyophilized. The extraction was performed twice independently. DH-P

was redissolved in 95% ethanol for further use.

Screening of secondary metabolites

using thin-layer chromatography (TLC)

DH-P was prepared to a final concentration of 10

mg/ml in 95% ethanol. Then, extract samples were subjected to TLC

analysis for the presence of phenolics and flavonoids as previously

described (25). Quercetin was used

as a reference for detection. A total of ~5 drops/sample were

applied on a 10x5 cm silica gel plate (Merck KGaA) and separated in

a mobile phase consisting of a ratio of ethyl acetate-to-acetic

acid-to-water of 8:1:1 (v/v/v). The gel plate was sprayed with 0.1%

2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate solution to visualize phenolics and

flavonoids using ultraviolet viewing cabinets (Spectronics

Corporation) at 366 nm.

Measurement of total phenolic

content

The total phenolic content in DH-P was determined in

a microwell plate as previously described with modification

(26). In total, 20 µl standard or

DH-P were added, followed by 100 µl 10% v/v Folin-Ciocalteu

solution in 96-well plates at room temperature for 3 min; then, 80

µl 1 M sodium carbonate was added at room temperature for 20 min.

The absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a microplate reader

(Tecan Group, Ltd.; cat. no. M200). Gallic acid (GA) was used as a

standard. Each sample was performed in triplicate. The total

phenolic content was reported as µg GA equivalent (E)/g tissue.

Measurement of total flavonoid

content

Total flavonoid content in DH-P was determined in a

microwell plate as previously described with a slight modification

(27). Distilled water (104 µl) was

mixed with 60 µl methanol in each well. Then, 20 µl standard or

DH-P and 8 µl 0.5 M potassium acetate solution were added, followed

by 8 µl 5% (w/v) aluminum chloride solution. The mixture was shaken

in an orbital shaker (Edmund Bühler GmbH) for 5 min and incubated

in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance was

measured at 415 nm. Quercetin was used as a standard. Each sample

was performed in triplicate. The total flavonoid content was

reported as µg quercetin equivalent (QE)/g tissue.

Measurement of total alkaloid

content

The total alkaloid content in DH-P was determined as

previously reported (28). A sample

(1 ml) of standard or DH-P was transferred to a separating funnel

and mixed with 5 ml each bromocresol green solution and phosphate

buffer (pH 4.7). The complex was extracted with 10 ml chloroform

using sequential addition of 1, 2, 3 and 4 ml. The extracted

complex was collected from each addition, pooled and measured for

absorbance at 470 nm. Atropine was used as a standard. Each sample

was performed in triplicate. The total alkaloid content was

reported as µg atropine equivalent (AE)/g tissue.

Identification of compounds using

ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC)-electrospray

ionization-QTOF-tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-QTOF-MS/MS)

DH-P at a concentration of 1 mg/ml in 95% ethanol

was filtered through a 0.2 µm nylon filter. The composition was

separated using UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS. A pure compound (dendrobine,

gigantol and quercetin) was used as a reference. These compounds

have been reported to accumulate in Dendrobium species and

exhibit antioxidant and anticancer properties (4,23). The

standard was prepared at a final concentration of 20 µg/ml in

methanol. All samples were analyzed by the Scientific Equipment

Center (Kasetsart University, Thailand). The chromatographic

separation and parameters were set up for the detection of

dendrobine, gigantol and quercetin as previously described

(29-31).

An ExionLC™ AD system (AB Sciex LLC) equipped with a C18

column (100.0x4.6 mm; internal diameter, 2.6 µm; Phenomenex, Inc.)

was used for separation. Metabolite analysis of the matrix was

performed on a SCIEX X500R QTOF system with Turbo V™

source (AB Sciex LLC) using the ESI probe operated in either

positive or negative ion mode. Information-dependent acquisition

was also performed on the X500R QTOF system. The TOF MS (scan

range, 100-500 Da) parameters were as follows: declustering

potential (DP), 50 V; collision energy (CE), 10 V and accumulation

time, 0.25 sec for positive mode and DP, -60 V; CE, -10 V and

accumulation time, 0.25 sec for negative mode. The TOF MS/MS (scan

range 50-500 Da) parameters were DP, 50 V; CE, 35 V; CE spread

(CES), 0 V and accumulation time, 0.1 sec for the positive mode,

but DP, -60 V; CE, -35 V; CES, 0 V; accumulation time, 0.1 sec for

the negative mode. MS/MS fragmentation patterns of compounds

detected in the crude extract were compared with those in the

National Institute of Standards and Technology research library

(version 2017; https://chemdata.nist.gov/). Compounds with a mass

error within ±5 ppm were selected as putative metabolites present

in DH-P.

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH)

radical scavenging capacity

DPPH assay was performed in a microplate as

previously described, with minor modification (32). A sample (25 µl) of the control or

DH-P was added in each well with 160 µl 150 µM DPPH radical

solution (Sigma Aldrich; cat. no. D9132). The mixture was incubated

in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The scavenging activity

of the samples against DPPH radicals was detected at 517 nm. Each

sample was run in triplicate. Ethanol was used as a background

control. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control and standard.

Scavenging activity was calculated based on the absorbance (A) as

follows: % Radical scavenging=(1-Asample/A

control) x100. Antioxidant activity was expressed as

vitamin C equivalent antioxidant capacity (VCEAC) in µg/ml.

2,2'-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS)

radical scavenging capacity

ABTS assay was performed in a microplate as

previously described, with minor modification (33). The working solution was prepared by

mixing 0.5 ml ABTS+ (Applichem; cat. no. A1088) with 30

ml methanol at a ratio of 1:60 v/v. The absorbance at 734 nm was

determined to be 1.1±0.02 AU before use in the experiment. The

reaction was performed by mixing 10 µl control or DH-P with 190 µl

ABTS+ working solution at room temperature for 2 h. The

scavenging activity was detected at 734 nm. Each sample was run in

triplicate. Ethanol was used as a background control. Ascorbic acid

was used as a positive control and standard. ABTS scavenging

activity was calculated as for DPPH.

Ferric reducing antioxidant power

(FRAP)

FRAP assay was performed in a microplate as

previously described with a minor modification (34). A total of 10 µl control or DH-P was

added with 140 µl FRAP solution in the dark at 37˚C for 30 min. The

absorbance of the mixture was read at 593 nm. Each sample was run

in triplicate. Ethanol was used as a background control. A standard

curve was generated using ascorbic acid (0-1,000 µM) and used for

calculation of the antioxidant activity. Reducing power was

reported as the FRAP value/mg extract.

Inhibition of collagenase

activity

Collagenase inhibition assay was performed using

Collagenase Activity Colorimetric Assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA; cat. no. MAK293) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The mixture was prepared by adding collagenase assay

buffer and DH-P sample or inhibitor control (1 M

1,10-phenanthroline). Ethanol was used as a background control. The

mixture was added with 5 µl 0.35 U/ml collagenase enzyme at room

temperature for 10 min. A total of 20 µl 1 mM

N-[3-(2-furyl)acryloyl]-L-leucyl-glycyl-L-prolyl-L-alanine

substrate and 30 µl collagenase buffer were added. The reaction was

immediately measured in the kinetic mode at absorbance of 345 nm

and 37˚C for 5-15 min. Each sample was performed in triplicate.

Collagenase inhibition was calculated according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

Inhibition of hyaluronidase

activity

Hyaluronidase inhibition assay was performed as

previously described (35). A

reaction was performed by mixing 35 µl 1% dimethyl sulfoxide

(DMSO), 5 µl DH-P or inhibitor control (1 mg/ml oleanolic acid) and

5 µl 1.5 U/ml hyaluronidase. Ethanol was used as a control. After

the mixture had been incubated at 37˚C for 10 min, 5 µl 0.03% (w/v)

hyaluronic acid in 300 mM sodium phosphate (pH 5.35) was added and

further incubated at 37˚C for 45 min. Then, 5 µl acid albumin

substrate [0.1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich; cat. no. 12659) in 24 mM sodium

acetate and 79 mM acetic acid (pH 3.75)] was added. The absorbance

was determined at 600 nm and measured immediately following the

addition of the substrate and continuously for 10 min at room

temperature. Each sample was run in triplicate. The hyaluronidase

inhibition was calculated as follows: % Hyaluronidase

inhibition=(1-Asample/Acontrol) x100.

Cell culture and cytotoxicity

Human melanoma SK-MEL-28 cells (passage 14) were

cultured at a seeding density of ~20,000 cells/cm2 in 75

cm2 flask in Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM;

ATCC; cat. no. 30-2003) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(FBS) (Gibco; cat. no. 10270-106) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

SK-MEL-28 cells (passage 15-22) were seeded in 96-well plates at a

density of 5,000 cells/well and cultured for 24 h in EMEM. DH-P at

final concentrations of 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 80 or 100 µg/ml

in 3.17% ethanol was added to each well. DMSO at a final

concentration of 5% was used as an inhibitor control. Wells

containing 3.17% ethanol at a final concentration served as

controls. Cell cultures were maintained at 37˚C with 5%

CO2 throughout the treatment period. The experiments

were performed twice independently with three replicates for each

treatment. Following treatment for 96 h, 40 µl MTT solution was

added and incubated at 37˚C for 3 h. After removing the

supernatant, 50 µl 100% DMSO was added. The absorbance was measured

at 570 nm. The cell viability was calculated as follows: % Cell

viability=Asample/Acontrol x100. The

half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was

determined from a dose response curve (GraphPad Software Version

10.3.1, Inc.; Dotmatics).

Wound healing assay

SK-MEL-28 cells were cultured in serum-free EMEM in

24-well plates at a density of 1x105 cells/well (~80%

confluency) at 37 ˚C for 24 h. After removing media, a gap in the

middle of each well was created by scratching with a sterile 100-µl

pipette tip. Loosely attached cells were removed using PBS (pH

7.4). Cells were treated with the DH-P at 20 µg/ml for 0, 24, 48,

and 96 h. DMSO (5%) was used as an inhibitor control. A drug-free

plate with 3.17% ethanol served as a control. Cell cultures were

maintained at 37˚C with 5% CO2 throughout the treatment

period. The cell migration was photographed under a light

microscope at 0, 24, 48 and 96 h after treatment. Gap distances

were measured using ImageJ software Version 1.53v (National

Institutes of Health). The experiment was performed twice

independently with three replicates for each treatment.

Cell migration assay

Cell migration was assessed using the EZCell Cell

Invasion Assay kit (Abcam; cat. no. ab287890) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, diluted human fibronectin

solution at a 1:5 ratio was coated on the top chamber at 25˚C for 3

h. A total of ~5x104 cells in FBS-free EMEM were seeded

in the top chamber with DH-P at 0.5 (10 µg/ml), 2/3 IC50

(13.3 µg/ml), and IC50 (20 µg/ml). Cells exposed to

3.17% ethanol served as controls. Then, 200 µl FBS-containing EMEM

was added to the bottom chamber. The chamber was incubated at 37˚C

in a humidified CO2 incubator for 72 h according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Cells that had migrated to the bottom

chamber were stained with dissociation/dye solution at 37˚C with 5%

CO2 for 1 h. Each treatment was run in four replicates.

The absorbance of the invaded cells was read at excitation/emission

wavelengths of 535/587 nm using a fluorescence microplate reader

(Tecan Group, Ltd.). The percentage of invasive cell numbers was

calculated from a standard curve.

Analysis of nuclear morphology by

Hoechst 33342 staining

SK-MEL-28 cells were seeded at a density of

3x105 cells/well in a 35x10 mm dish chamber (SPL Life

Sciences) for 24 h. Cells were treated with DH-P at 20 µg/ml for 0,

48 and 96 h. Dishes containing 3.17% ethanol and 5% DMSO were used

as controls and inhibitor controls, respectively. Cells were

incubated at 37˚C with 5% CO2 during treatment. Cells

were observed for DNA damage at 0, 48 and 96 h after treatment.

After removing media, nuclei were stained with 10 µg/ml Hoechst

33342 (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in PBS (pH 7.4) at room

temperature for 15 min in the dark, as previously described

(36). The morphology of nuclei was

examined using a fluorescence microscope at 40X magnification

(Olympus Corporation). Each treatment was run in triplicate.

Gene expression analysis using reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q)PCR

SK-MEL-28 cells were treated with DH-P at 20 µg/ml

for 48 h. Cells exposed to 3.17% ethanol served as controls. Cells

were incubated at 37˚C with 5% CO2 during the treatment

period. A total of ~1x106 cells/group was pooled and

used to isolate total RNA with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cDNA was synthesized using a

FIREScript RT cDNA Synthesis kit (Solis BioDyne). The cDNA samples

were used as templates in the qPCR, while total RNA was used to

screen for gDNA contamination. The qPCR reaction mixture was at a

final volume of 20 µl containing 1X HOT FIREPol EvaGreen qPCR Mix

Plus (NO-ROX; Solis BioDyne), 0.4 µM primer pair (Table I) and cDNA template (1 ng).

Thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial activation at

95˚C for 12 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95˚C for

15 sec, annealing at primer-specific temperatures (Table I) for 20 sec and extension at 72˚C

for 20 sec and final extension at 72˚C for 10 min. β-actin was used

as the internal reference, and deionized water as the negative

control. The experiments were performed independently twice, each

with three biological replicates/treatment. Each gene from every

sample was assessed in duplicate. The relative gene expression was

determined using the comparative 2-∆∆Cq method (37).

| Table IPrimer pairs used to amplify genes

involved in apoptosis via intrinsic pathway. |

Table I

Primer pairs used to amplify genes

involved in apoptosis via intrinsic pathway.

| Gene | NCBI accession

no. | Primer | Sequence,

5'à3' | Annealing

temperature, ˚C | Amplicon size,

bp |

|---|

| β-actin | HQ154074.1 | Forward |

CATCCTGCGTCTGGACCTGG | 58 | 107 |

| | | Reverse |

TAATGTCACGCACGATTTCC | | |

| bax | JX524562.1 | Forward |

TCTGACGGCAACTTCAACTG | 50.5 | 201 |

| | | Reverse |

CGTCCCAAAGTAGGAGAGG | | |

| bcl-2 | KY098799.1 | Forward |

GAGGATTGTGGCCTTCTTTG | 50.8 | 118 |

| | | Reverse |

GTGCCGGTTCAGGTACTCAG | | |

|

caspase-3 | NM_004346.4 | Forward |

TGGAATTGATGCGTGATGTT | 48.2 | 161 |

| | | Reverse |

ACTTCTACAACGATCCCCTC | | |

|

caspase-9 | AF093130.1 | Forward |

GAGGGAGTCAGGCTCTTCCT | 51.6 | 228 |

| | | Reverse |

GCTCGACATCACCAAATCCT | | |

| p53 | AB082923.1 | Forward |

GTTCCGAGAGCTGAATGAGG | 51.6 | 157 |

| | | Reverse |

TGAGTCAGGCCCTTCTGTCT | | |

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism Version

10.3.1 (GraphPad Software, Inc.; Dotmatics). All data are presented

as the mean ± SEM of ≥2 independent experimental repeats. One-way

ANOVA followed by Dunnett's or Tukey's test was used to analyze

inhibition of ECM activity and cell viability and migration,

respectively. An unpaired t-test was performed in gene expression

analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Detection and quantification of

secondary metabolites in DH-P

Dendrobium accumulates large amounts of

compounds beneficial to human health, especially polyphenols,

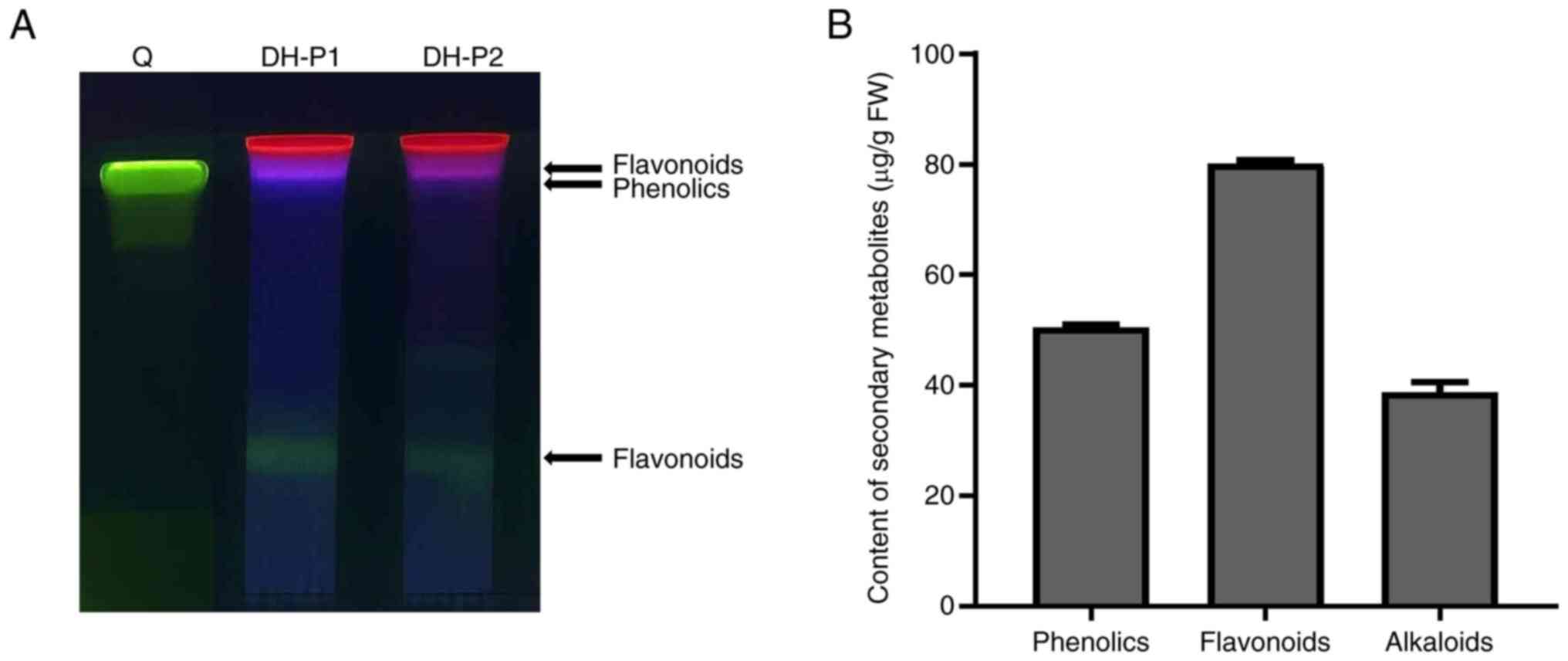

flavonoids and alkaloids. Based on the TLC analysis, the two

independent replications of DH-P had similar amounts and types of

compound (Fig. 1A). Violet and

green fluorescence were observed in DH-P, indicating the presence

of flavonoids and phenolics. However, quercetin (a common flavonol

produced in plants) was not observed. Furthermore, total phenolics,

flavonoids and alkaloids in DH-P were quantified and comprised

50.51±0.44, 80.11±0.69 and 38.75±1.77 µg/g fresh weight (FW),

respectively (Fig. 1B).

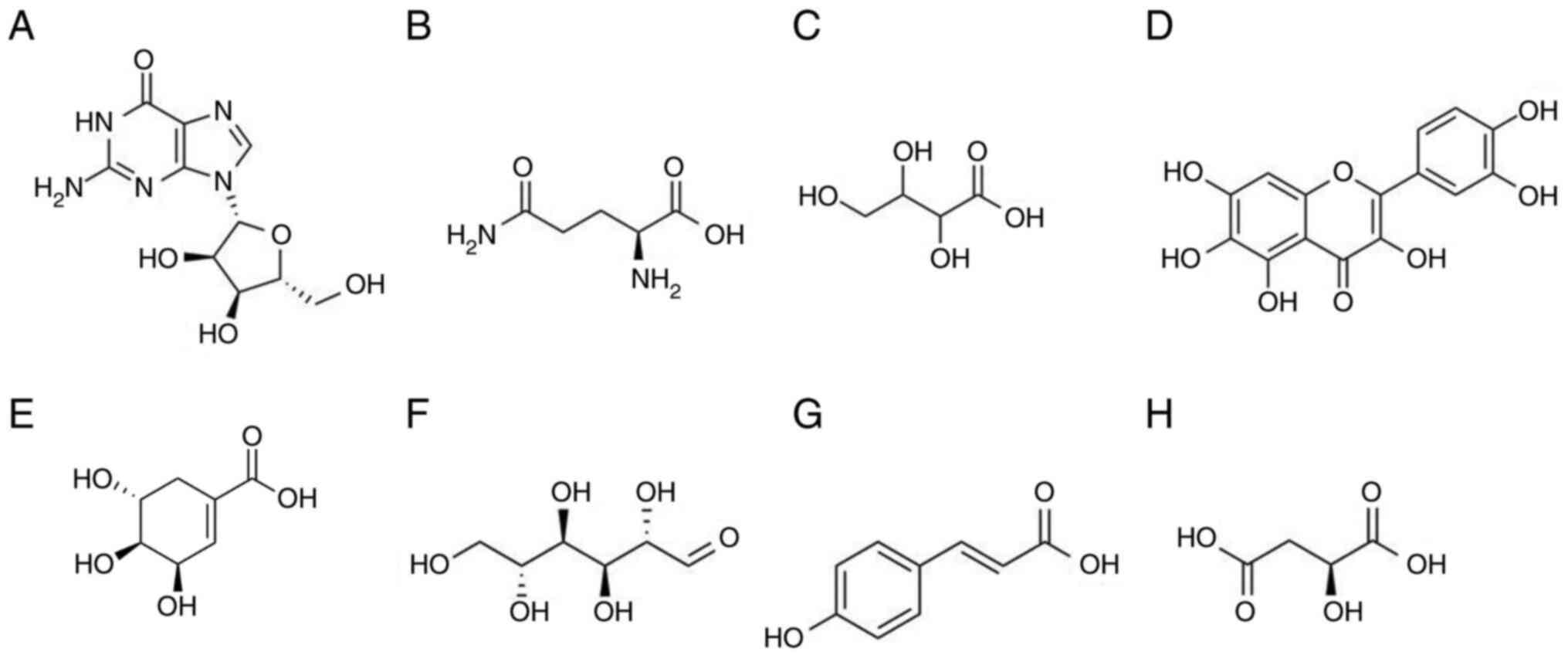

Identification of tentative compounds

in DH-P using UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS

The present study used a targeted approach based on

HR-MS (QTOF system) to investigate the chemical components in DH-P.

The chromatographic separation and parameters were set according to

separate detection methods for dendrobine (29), gigantol (30) and quercetin (31). These three targeted compounds were

not detected in DH-P. In total, 119 compounds were matched using

the MS2 spectra with the NIST Research Library v.2017. Each

compound was then manually re-evaluated for mass error and searched

for its functions. The focus was on compounds with biological

activities such as anti-oxidant, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory,

anti-aging, depigmentation and anti-microbial activity. A total of

eight tentative compounds of interest were identified using the

detection method for quercetin (analyzed in a negative mode, with

mass error <±5 ppm). The chemical formula, retention time,

observed mass and calculated mass of the precursor ions, mass error

and biological activity of compounds are summarized in Table II (38-45).

The tentative compounds were guanosine, L-glutamine, threonic acid,

quercetagetin, shikimic acid, D-(+)-mannose, p-coumaric acid

and L-malic acid (Table II;

Figs. 2 and S1).

| Table IITentative compounds in DH-P

identified using ultra-high-performance liquid

chromatography-electrospray ionization-quadrupole time-of-flight

tandem mass spectrometry and National Institute of Standards and

Technology (NIST) research library v.2017. |

Table II

Tentative compounds in DH-P

identified using ultra-high-performance liquid

chromatography-electrospray ionization-quadrupole time-of-flight

tandem mass spectrometry and National Institute of Standards and

Technology (NIST) research library v.2017.

| Tentative

Compound | Chemical

formula | Retention time,

min | Observed

[M-H]-, m/z | Calculated

[M-H]-, m/z | Mass error,

ppm | Main MS2 fragments,

m/z | Biological

activity | (Refs.) |

|---|

| L-glutamine |

C5H10N2O3 | 2.370 | 145.0622 | 145.0619 | 2.0681 | 127.0514;

84.0456 | Anti-oxidant | (38) |

| D-(+)-mannose |

C6H12O6 | 2.462 | 179.0563 | 179.0561 | 1.1170 | 71.0139;

59.0140 | Anti-cancer;

anti-bacterial | (39) |

| Threonic acid |

C4H8O5 | 2.480 | 135.0302 | 135.0299 | 2.2217 | 75.0086;

59.0142 | Stimulatory action

on vitamin C uptake | (40) |

| Guanosine |

C10H13N5O5 | 2.490 | 282.0847 | 282.0844 | 1.0635 | 150.0419; 133.0157;

108.0201 | Anti-oxidant;

anti-inflammatory | (41) |

| Shikimic acid |

C7H10O5 | 2.487 | 173.0450 | 173.0455 | -2.8894 | 93.0343; 71.0140;

65.0398 | Depigmentation | (42) |

| L-malic acid |

C4H6O5 | 2.527 | 133.0139 | 133.0142 | -2.2554 | 115.0046; 72.9932;

71.0139 | Anti-oxidant;

anti-microbial | (43) |

| Quercetagetin |

C15H10O8 | 9.437 | 317.0306 | 317.0303 | 0.9463 | 151.0037;

109.0299 | Anti-cancer | (44) |

| p-coumaric

acid |

C9H8O3 | 9.560 | 163.0406 | 163.0401 | 3.0667 | 119.0507;

91.0179 | Anti-oxidant;

anti-microbial; anti-tumor; anti-inflammatory | (42,45) |

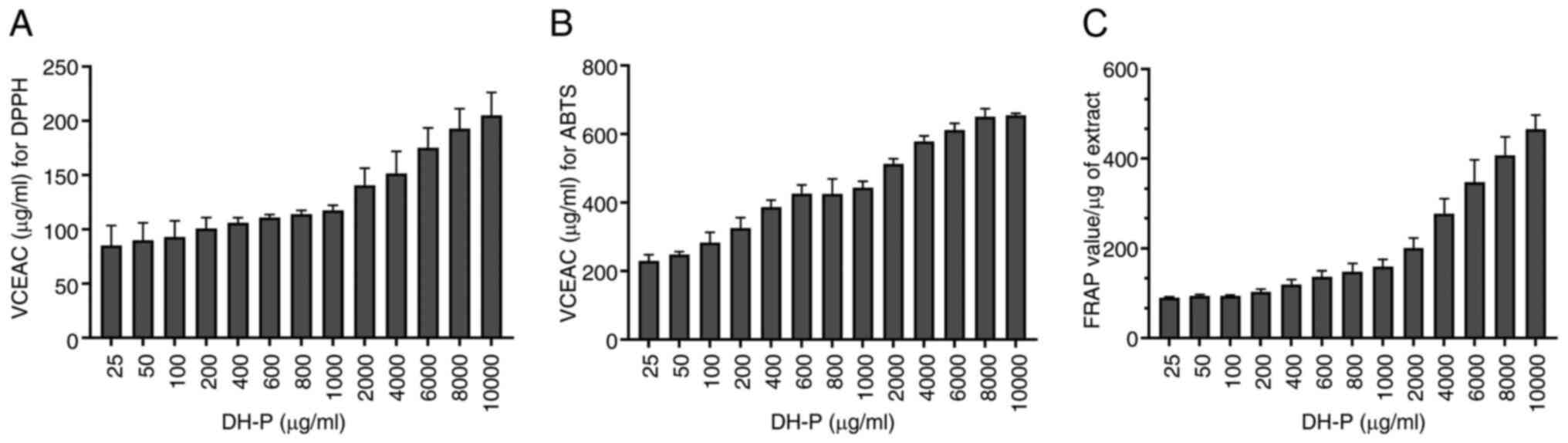

Inhibition of free radicals

The effect of DH-P (25-10,000 µg/ml) on scavenging

DPPH and ABTS radicals and reducing power for the ferric ion

(Fe3+) were investigated. Increased concentrations of

DH-P had a greater inhibitory effect on DPPH and ABTS radicals,

suggesting that the radical scavenging was concentration-dependent

(Fig. 3A and B). However, DH-P scavenged ABTS radicals

more effectively than DPPH. At the highest concentration (10,000

µg/ml), DH-P had VCEAC of 205.09±20.99 and 644.73±18.47 µg/ml for

DPPH and ABTS radicals, respectively. A similar trend of scavenging

performance was observed in the FRAP assay, suggesting that the

inhibition was concentration-dependent (Fig. 3C). The highest concentration (10,000

µg/ml) of DH-P had a reducing power for Fe3+ equivalent

to 465.83±31.37 FRAP value/µg extract. Consistent results across

three different antioxidant assays validated the strong radical

scavenging and reducing properties of DH-P.

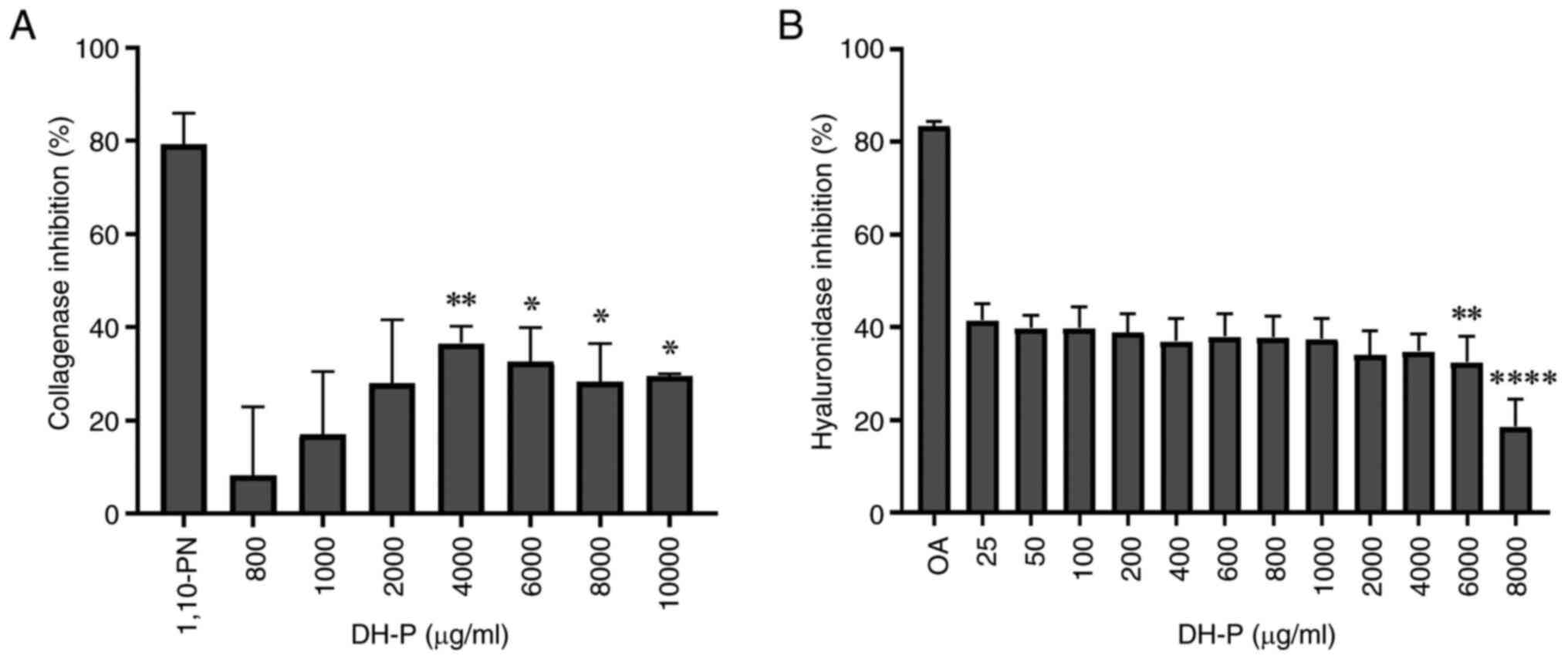

Inhibition of collagenase and

hyaluronidase activity

The present study investigated the effect of DH-P on

the inhibition of enzymes responsible for degrading ECM components,

such as collagenase and hyaluronidase (Fig. 4). DH-P inhibited the activity of

collagenase and hyaluronidase, however, its inhibitory effects were

less potent than those of the respective inhibitor controls,

1,10-PN and OA. DH-P significantly inhibited collagenase activity

at 4,000-10,000 µg/ml, with a slight decrease in inhibitory effects

as the concentration increased. DH-P at a concentration of 4,000

µg/ml exerted the maximum inhibitory activity for the collagenase

enzyme (36.57±3.62%; Fig. 4A). The

inhibitory activity of hyaluronidase was observed across DH-P

concentrations 25-4,000 µg/ml with no significant difference, with

the maximum inhibition being 41.52±3.49%; inhibition was

significantly decreased by DH-P ≥6,000 µg/ml (Fig. 4B).

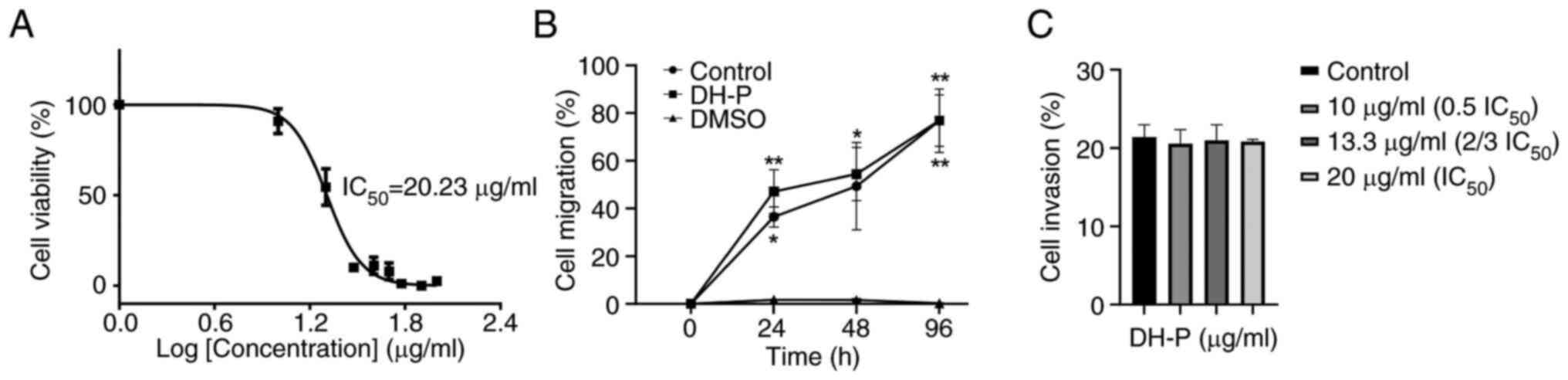

Inhibition of melanoma cell viability

and migration

The cytotoxicity was evaluated on melanoma SK-MEL-28

cells treated with DH-P (0-100 µg/ml) for 96 h. The viability of

SK-MEL-28 gradually decreased as the concentration of DH-P

increased (Figs. 5A and S2). DH-P at 20 µg/ml significantly

decreased viability of SK-MEL-28 cells. In addition, SK-MEL-28 cell

viability was significantly inhibited when cells were exposed to

DH-P ≥30 µg/ml (Fig. S2). DH-P had

an IC50 value of 20.23±1.04 µg/ml (Fig. 5A). Therefore, DH-P at 20 µg/ml was

applied for subsequent experiments.

Cells treated with 20 µg/ml DH-P migrated at a

similar rate as the control group at all time points, while 5% DMSO

(inhibitor control) inhibited cell migration (Figs. 5B and S3). In addition, there was no significant

difference in the invaded cell number between DH-P at all

concentrations and the control group, suggesting that DH-P had no

inhibitory effect on migration of SK-MEL-28 cells (Fig. 5C).

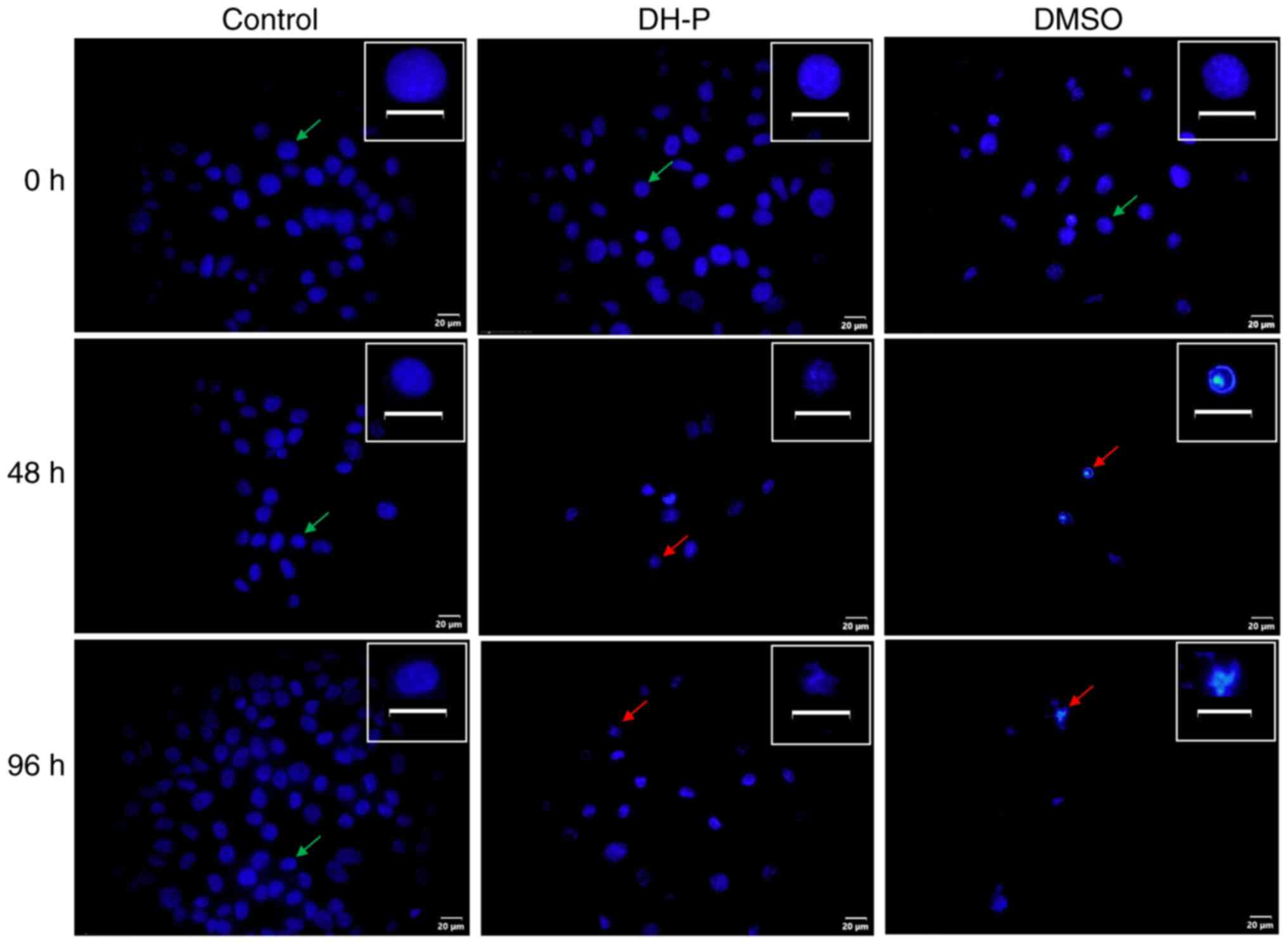

Analysis of cell apoptosis

As DH-P could inhibit viability of SK-MEL-28 cells,

cell death induced through apoptosis was investigated. Hoechst

staining was performed to observe cell and nuclear morphological

changes (Fig. 6). Following

exposure to DH-P at 20 µg/ml for 48 and 96 h, nuclei were condensed

or fragmented. In addition, the cell number decreased notably

compared with the control group. Furthermore, cells treated with 5%

DMSO (inhibitor control) were decreased in number, and the nuclei

were fragmented.

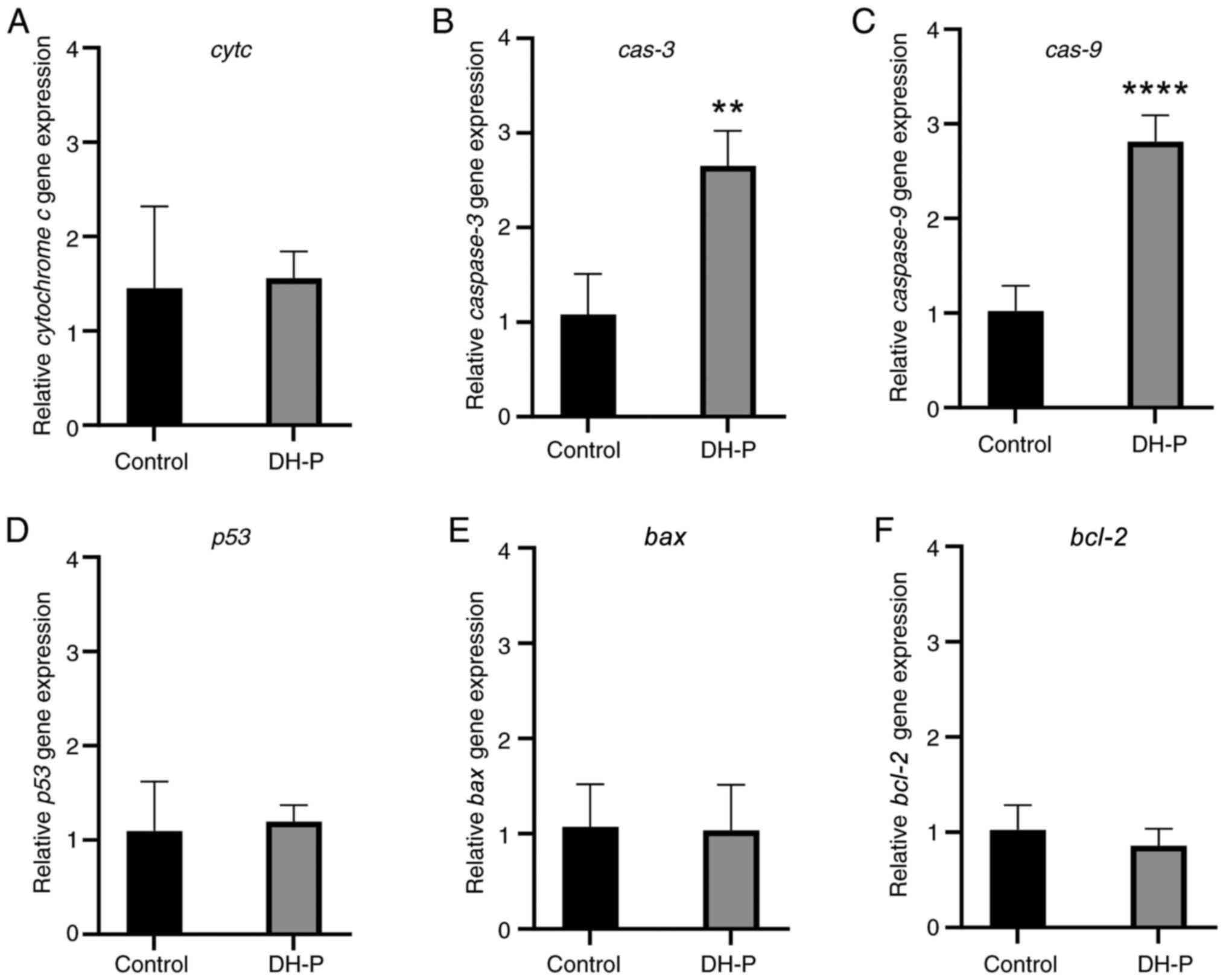

The expression of genes involved in intrinsic

apoptosis was evaluated to confirm whether cell death was induced

through apoptosis (Fig. 7). The

relative fold-changes in the expression of the apoptotic genes

bax, bcl-2, cytc, cas-3, cas-9

and p53 were 1.035, 0.858, 1.558, 2.650, 2.813 and 1.195,

respectively, compared with the control group. Only cas-3

and cas-9 were significantly upregulated by DH-P. There was

no significant change in the expression of bax,

bcl-2, cytc and p53.

Discussion

Dendrobium spp. is a large genus with

>1,000 species (3).

Dendrobium contains high amounts of bioactive compounds,

such as polyphenols, flavonoids, alkaloids and polysaccharides,

which confer biological activities beneficial for human health and

wellness (4,17,46).

Dendrobium Pearl Vera is a hybrid whose genetic material is

derived from D. bigibbum (93.75%) and D.

canaliculatum (6.25%), which are used as cosmetic ingredients

and a treatment for sores, respectively (24,46).

The present findings agreed with several reports on

Dendrobium benefits (3-8,30),

especially for skin treatment and health improvement, revealing

that Dendrobium Pearl Vera accumulates phenolics, flavonoids

and alkaloids. These bioactive compounds exert key biological

effects, such as anti-oxidant, anti-aging, and anti-cancer

properties (2,4-6).

Crude extracts from DH plant at 1 mg/ml exhibited scavenging

activity and human tyrosinase inhibition (24). In addition, DH-P at various

concentrations demonstrated inhibition of free radicals and enzyme

activity involved in ECMs degradation, as well as induction of

melanoma cell apoptosis, which may be attributed to its bioactive

compounds.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) serve a key role in

cancer growth and development. Elevated ROS levels promote

proliferation and metastasis, thereby contributing to cancer

progression (5,47). DH-P contains secondary metabolites

that may serve as free radical scavengers or metal ion chelators

(24), suggesting its bioactive

components may inhibit SK-MEL28 cell proliferation by reducing ROS

levels. In addition, dysregulation of metal homeostasis, such as

iron, may mediate the production of ROS and alter MMP activity,

causing destruction of the cell membrane leading to skin aging and

malignant cancer (47-49).

DH-P also affected the activity of collagenase and hyaluronidase.

Skin aging and cancer progression occur via decreased skin strength

and resiliency, mostly due to alteration of the ECM biomolecules

such as collagen, elastin and HA (11,13,49).

Among these, collagen fibrils, the most abundant structural protein

in the skin, are particularly degraded by collagenases and other

MMPs (12,49). Hydrophilic ECM biomolecules,

including the non-sulfated glycosaminoglycan and HA, may be present

in lower quantities under physiological conditions, but the

increase of HA significantly affects the progression and metastasis

of cancer cells (13). Phenolic and

flavonoids protect against skin destruction and hyperpigmentation

by inhibiting the enzymes involved in the degradation of EMC

biomolecules as well as inhibiting the melanin production by

melanoma cells (24,50). Dendrobium Pearl Vera

accumulates bioactive secondary metabolites; therefore, the extract

may also protect skin damage from pollutants and sunlight exposure,

which are common stimuli for the generation of free radicals and an

increase in dermal EMC-degrading enzyme activity. DH-P at 4,000

µg/ml exerted maximal collagenase activity inhibition and

maintained hyaluronidase activity, suggesting this dose may prolong

the structural integrity of ECM. It has been reported that D.

crepidatum contains bibenzyl derivatives, polyphenols and

flavonoids that exert antioxidant and cytotoxic effects on HeLa

(human cervical carcinoma) and U251 (human glioblastoma) cancer

cell lines (6). Alkaloids have

medicinal properties, especially for cancer prevention, and are

commonly found in orchids, including Dendrobium Pearl Vera,

with most alkaloids in orchids being classified either as

pyrrolizidines or dendrobines (51).

To the best of our knowledge, few bioactive

compounds have been reported with antioxidant and anticancer

activity in DH-P, such as 3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxybenzaldehyde,

5-hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde, 4-guanidinobutyric acid,

L-norleucine and acetophenone (24). Notably, the present study expanded

the chemical components in DH-P to identify other chemicals, using

QTOF. A total of eight tentative compounds [guanosine, L-glutamine,

threonic acid, quercetagetin, shikimic acid, D-(+)-mannose,

p-coumaric acid, and L-malic acid] were identified with

beneficial activities for skin and medicinal use, such as

anti-oxidant, anti-aging, anti-microbial anti-cancer,

anti-inflammatory and whitening effects. The therapeutic potential

of plant-derived derivatives may be attributed to combined action

of diverse active phytochemicals with varying chemical structures

that act synergistically to enhance biological activities (44,52).

Based on the present TLC analysis, flavonoids and phenolics were

detected in varying amounts and types. Notably, different plant

species may exhibit variations in fluorescent spot coloration

(25,53). The strong inhibitory effect of DH-P

on SK-MEL-28 cell viability may result from the interactions among

its constituent compounds.

Several reports suggested that extracts from

Dendrobium spp. inhibit proliferation and metastasis on

various types of cancer cell (4,6,17); to

the best of our knowledge, however, research is limited on the

inhibitory effects of Dendrobium extract on skin cancer

cells (10,24,36).

Cytotoxic effects against cancer cells are classified as ‘very

active’, ‘active’, ‘moderately active’ or ‘no cytotoxic activity’

when the IC50 value is <10, 10-100, 101-500 or

>500 µg/ml, respectively (54).

Based on the IC50 value (20.23 µg/ml) of DH-P for

SK-MEL-28 cells, it was classified as an active inhibitor toward

human melanoma cells. By contrast, SK-MEL-28 cells that survived

treatment with 20 µg/ml DH-P could migrate and invade at the same

rate as the control group at all time points, implying the

progression and aggressiveness of escaping melanoma cells.

SK-MEL-28 is a malignant melanoma cell line and represents the most

aggressive form of skin cancer (9,10).

Malignant cell migration and invasion are the primary

manifestations of tumor biology and key components of metastasis,

which is a notable cause of death in oncology patients (55).

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death

occurring naturally and is induced in cancer cells by natural

compounds (17-22).

Bioactive compounds, such as quercetin, prevent the cell cycle

progression, inhibit cell proliferation and promote cell apoptosis

in numerous types of cancer, such as lung, colorectal, pancreatic,

breast and prostate cancer (56).

The extracts from D. draconis, D. falconeri, D.

findlayanum, D. loddigesii, as well as Dendrobium

Pearl Vera, exhibit anti-cancer activity (14). Cell apoptosis is characterized by

cell shrinkage and chromatin condensation and fragmentation that

produces compact nuclei and/or the formation of apoptotic bodies

(44). Decreased cell number and

fragmentation of nuclei were observed in SK-MEL-28 cells treated

with DH-P, suggesting cell apoptosis might have occurred (36). In addition, the mRNA expression of

apoptotic executors cas-9 and cas-3 significantly

increased in SK-MEL-28 cells treated with DH-P, demonstrating that

cell death was caused by apoptosis. The caspases are a family of

cysteine proteases and key mediators of apoptosis. Cas-8 and -9 are

determinants in the extrinsic and intrinsic pathway, respectively.

Cas-3 is key for apoptotic chromatin condensation and DNA

fragmentation (44). Although the

expression levels of bax, bcl-2, cytc and

p53 were unchanged, the significant increase of cas-9

and cas-3 expression demonstrated a hallmark of apoptosis

via the intrinsic pathway. Polysaccharides from D.

officinale induce apoptosis in Saos-2 osteosarcoma cells via

the intrinsic pathway, with no change in p53, Bax and Cas-9 protein

levels, but an increase in Cas-3 expression (21). Certain compounds in

Dendrobium, such as moscatilin and quercetin, exert

anti-cancer effects on melanoma cells and induce cell apoptosis via

the intrinsic pathway (17,23). Quercetagetin was identified in DH-P

and has been reported to induce the apoptotic process through the

intrinsic apoptotic pathway in cervical (CaSki), breast

(MDA-MB-231) and lung (SK-Lu-1) cancer cells (44).

In conclusion, based on the inhibitory effects of

DH-P on free radicals, ECM enzymes and SK-MEL-28 cell

proliferation, Dendrobium Pearl Vera is a promising natural

candidate as an anti-oxidant and for skin cancer prevention as an

anti-cancer agent.

Supplementary Material

Tandem mass spectrometry spectra

matched with the NIST research library v.2017. The MS2 spectra from

precursor ions in DH-P (blue) were matched with NIST research

library v.2017 (gray) and identified for the tentative compounds.

(A) Guanosine. (B) L-glutamine. (C) Threonic acid. (D)

Quercetagetin. (E) Shikimic acid. (F) D-(+)-mannose. (G)

p-coumaric acid. (H) L-malic acid.

Viability of SK-MEL-28 cells treated

with DH-P for 96 h. N=6. ****P<0.0001 vs. control.

ns, not significant; DH-P, propanolic extract from

Dendrobium Pearl Vera hybrid.

Migration of SK-MEL28 cells treated

with DH-P at 20 μg/ml and 5% DMSO (inhibitor control).

Magnification, x10. DH-P, propanolic extract from Dendrobium

Pearl Vera hybrid.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank CordyBiotech Co.,

Ltd. for providing plant material.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by Basic Research Fund

(grant no. BRF5/2567) and International SciKU Branding (ISB),

Faculty of Science, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

found in Figshare under accession number

10.6084/m9.figshare.30204490 at the following URL: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30204490).

Authors' contributions

RK and PM performed the experiments. RK, PM, and AA

designed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and

wrote the manuscript. PK, NPT, NMS, WP and PW conceived the study

and analyzed data. AA and PW confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Givnish TJ, Spalink D, Ames M, Lyon SP,

Hunter SJ, Zuluaga A, Iles WJD, Clements MA, Arroyo MTK,

Leebens-Mack J, et al: Orchid phylogenomics and multiple drivers of

their extraordinary diversification. Proc R Soc B.

282(20151553)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Minh TN, Khang do T, Tuyen PT, Minh LT,

Anh LH, Quan NV, Ha PT, Quan NT, Toan NP, Elzaawely AA and Xuan TD:

Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of phalaenopsis orchid

hybrids. Antioxidants (Basel). 5(31)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Moretti M, Cossignani L, Messina F,

Dominici L, Villarini M, Curini M and Marcotullio MC: Antigenotoxic

effect, composition and antioxidant activity of Dendrobium

speciosum. Food Chem. 140:660–665. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Cakova V, Bonte F and Lobstein A:

Dendrobium: Sources of active ingredients to treat

age-related pathologies. Aging Dis. 8:827–849. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Tungmunnithum D, Thongboonyou A, Pholboon

A and Yangsabai A: Flavonoids and other phenolic compounds from

medicinal plants for pharmaceutical and medical aspects: An

overview. Medicines (Basel). 5(93)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Paudel MR, Chand MB and Pant B and Pant B:

Assessment of antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of extracts of

Dendrobium crepidatum. Biomolecules. 9(478)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Luo A, He X, Zhou S, Fan Y, He T and Chun

Z: In vitro antioxidant activities of a water-soluble

polysaccharide derived from Dendrobium nobile Lindl.

extracts. Int J Biol Macromol. 45:359–363. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Luo A, Ge Z, Fan Y, Luo A, Chun Z and He

X: In vitro and in vivo antioxidant activity of a water-soluble

polysaccharide from Dendrobium denneanum. Molecules.

16:1579–1592. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Roky AH, Islam MM, Ahasan AMF, Mostaq MS,

Mahmud MZ, Amin MN and Mahmud MA: Overview of skin cancer types and

prevalence rates across continents. Cancer Pathog Ther. 3:89–100.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Daveri E, Valacchi G, Romagnoli R,

Maellaro E and Maioli E: Antiproliferative effect of rottlerin on

Sk-Mel-28 melanoma cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2015(545838)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Moro N, Mauch C and Zigrino P:

Metalloproteinases in melanoma. Eur J Cell Biol. 93:23–29.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Kessenbrock K, Plaks V and Werb Z: Matrix

metalloproteinases: Regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell.

141:52–67. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Karousou E, Parnigoni A, Moretto P, Passi

A, Viola M and Vigetti D: Hyaluronan in the cancer cells

microenvironment. Cancers (Basel). 15(798)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ghai D, Verma J, Kaur A, Thakur K, Pawar S

and Sembi J: Bioprospection of orchids and appraisal of their

therapeutic indications. In: Bioprospecting of plant biodiversity

for industrial molecules. Santosh KU and Sudhir PS (eds.) John

Wiley & Sons, West Sussex, pp464, 2021.

|

|

15

|

Zhao X, Sun P, Qian Y and Suo H: D.

candidum has in vitro anticancer effect in HCT-116 cancer cells

and exerts in vivo anti-metastratic effects in mice. Nutr Res

Pract. 8:487–493. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Prasad R and Koch B: Antitumor activity of

ethanolic extract of Dendrobium formosum in T-cell lymphoma:

An in vitro and in vivo study. Biomed Res Int.

2014(753451)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Cardile V, Avola R, Graziano ACE and Russo

A: Moscatilin, a bibenzyl derivative from the orchid Dendrobium

loddigesii, induces apoptosis in melanoma cells. Chem Biol

Interact. 323(109075)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Robertson JD and Orrenius S: Molecular

mechanisms of apoptosis induced by cytotoxic chemicals. Crit Rev

Toxicol. 30:609–627. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Li Y, Zhang S, Geng JX and Hu XY: Curcumin

inhibits human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cell proliferation

through regulation of Bcl-2/Bax and cytochrome C. Asian Pac J

Cancer Prev. 14:4599–4602. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zhao Y, Liu Y, Lan XM, Xu GL, Sun YZ, Li F

and Liu HN: Effect of Dendrobium officinale extraction on

gastric carcinogenesis in rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2016(1213090)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zhang X, Duan S, Tao S, Huang J, Liu C,

Xing S, Ren Z, Lei Z, Li Y and Wei G: Polysaccharides from

Dendrobium officinale inhibit proliferation of osteosarcoma

cells and enhance cisplatin-induced apoptosis. J Funct Foods.

73(104143)2020.

|

|

22

|

Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Xin W, Liu N and Zhang

H: Nudol, a phenanthrene derivative from Dendrobium nobile,

induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis and inhibits migration in

osteosarcoma cells. Drug Des Devel Ther. 13:2591–2601.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Reyes-Farias M and Carrasco-Pozo C: The

anti-cancer effect of quercetin: Molecular implications in cancer

metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 20(3177)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Swainson NM, Pengoan T, Khonsap R,

Meksangsee P, Hagn G, Gerner C and Aramrak A: In vitro inhibitory

effects on free radicals, pigmentation, and skin cancer cell

proliferation from Dendrobium hybrid extract: A new plant

source of active compounds. Heliyon. 9(e20197)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Maliński MP, Kikowska MA, Soluch A,

Kowalczyk M, Stochmal A and Thiem B: Phytochemical screening,

phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of biomass from

Lychnis flos-cuculi L. in vitro cultures and intact plants.

Plants (Basel). 10(206)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Attard E: A rapid microtitre plate

Folin-Ciocalteu method for the assessment of polyphenols. Cent Eur

J Biol. 8:48–53. 2013.

|

|

27

|

Bhattacharyya P, Kumaria S, Diengdoh R and

Tandon P: Genetic stability and phytochemical analysis of the in

vitro regenerated plants of Dendrobium nobile Lindl., an

endangered medicinal orchid. Meta Gene. 2:489–504. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Shamsa F, Monsef H, Ghamooshi R and

Verdian-rizi M: Spectrophotometric determination of total alkaloids

in some Iranian medicinal plants. Thai J Pharm Sci. 32:17–20.

2008.

|

|

29

|

Sarsaiya S, Jain A, Fan X, Jia Q, Xu Q,

Shu F, Zhou Q, Shi J and Chen J: New insights into detection of a

dendrobine compound from a novel endophytic Trichoderma

longibrachiatum strain and its toxicity against phytopathogenic

bacteria. Front Microbiol. 11(337)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Chan CF, Wu CT, Huang WY, Lin WS, Wu HW,

Huang TK, Chang MY and Lin YS: Antioxidation and melanogenesis

inhibition of various Dendrobium tosaense extracts.

Molecules. 23(1810)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Kızıltaş H, Bingöl Z, Gören A, Alwasel SH

and Gülçin I: Anticholinergic, antidiabetic and antioxidant

activities of Ferula orientalis L. determination of its

polyphenol contents by LC-HRMS. Rec Nat Prod. 15:513–528. 2021.

|

|

32

|

Herald TJ, Gadgil P and Tilley M:

High-throughput micro plate assays for screening flavonoid content

and DPPH-scavenging activity in sorghum bran and flour. J Sci Food

Agric. 92:2326–2331. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Thaipong K, Boonprakob U, Crosby K,

Cisneros-Zevallos L and Byrne DH: Comparison of ABTS, DPPH, FRAP,

and ORAC assays for estimating antioxidant activity from guava

fruit extracts. J Food Compos Anal. 19:669–675. 2006.

|

|

34

|

Bolanos de la Torre AA, Henderson T, Nigam

PS and Owusu-Apenten RK: A universally calibrated microplate ferric

reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay for foods and applications

to Manuka honey. Food Chem. 174:119–123. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Nema NK, Maity N, Sarkar BK and Mukherjee

PK: Matrix metalloproteinase, hyaluronidase and elastase inhibitory

potential of standardized extract of Centella asiatica.

Pharm Biol. 51:1182–1187. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Wu Y, Zhang P, Yang H, Ge Y and Xin Y:

Effects of demethoxycurcumin on the viability and apoptosis of skin

cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 16:539–546. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Takaoka M, Okumura S, Seki T and Ohtani M:

Effect of amino-acid intake on physical conditions and skin state:

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J

Clin Biochem Nutr. 65:52–58. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Chen S, Wang K and Wang Q: Mannose: A

promising player in clinical and biomedical applications. Curr Drug

Deliv. 15:1435–1444. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Wang HY, Hu P and Jiang J:

Pharmacokinetics and safety of calcium L-threonate in healthy

volunteers after single and multiple oral administrations. Acta

Pharmacol Sin. 32:1555–1560. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Bettio LE, Gil-Mohapel J and Rodrigues AL:

Guanosine and its role in neuropathologies. Purinergic Signal.

12:411–426. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Chen YH, Huang L, Wen ZH, Zhang C, Liang

CH, Lai ST, Luo LZ, Wang YY and Wang GH: Skin whitening capability

of shikimic acid pathway compound. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci.

20:1214–1220. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Borah HJ, Borah A, Yadav A and Hazarika S:

Extraction of malic acid from Dillenia indica in organic

solvents and its antimicrobial activity. Sep Sci Technol.

58:314–325. 2023.

|

|

44

|

Alvarado-Sansininea JJ, Sánchez-Sánchez L,

López-Muñoz H, Escobar ML, Flores-Guzmán F, Tavera-Hernández R and

Jiménez-Estrada M: Quercetagetin and patuletin: Antiproliferative,

necrotic and apoptotic activity in tumor cell lines. Molecules.

23(2579)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Pei K, Ou J, Huang J and Ou S:

p-Coumaric acid and its conjugates: Dietary sources,

pharmacokinetic properties and biological activities. J Sci Food

Agric. 96:2952–2962. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Wang YH: Traditional uses and

pharmacologically active constituents of Dendrobium plants

for dermatological disorders: A review. Nat Prod Bioprospect.

11:465–487. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Shen T, Wang Y, Cheng L, Bode AM, Gao Y,

Zhang S, Chen X and Luo X: Oxidative complexity: The role of ROS in

the tumor environment and therapeutic implications. Bioorg Med

Chem. 127(118241)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Ying JF, Lu ZB, Fu LQ, Tong Y, Wang Z, Li

WF and Mou XZ: The role of iron homeostasis and iron-mediated ROS

in cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 11:1895–1912. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Cole MA, Quan T, Voorhees JJ and Fisher

GJ: Extracellular matrix regulation of fibroblast function:

Redefining our perspective on skin aging. J Cell Commun Signal.

12:35–43. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Kanlayavattanakul M, Lourith N and Chaikul

P: Biological activity and phytochemical profiles of

Dendrobium: A new source for specialty cosmetic materials.

Ind Crops Prod. 120:61–70. 2018.

|

|

51

|

Śliwiński T, Kowalczyk T, Sitarek P and

Kolanowska M: Orchidaceae-derived anticancer agents: A review.

Cancers (Basel). 14(754)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Pezzani R, Salehi B, Vitalini S, Iriti M,

Zuñiga FA, Sharifi-Rad J, Martorell M and Martins N: Synergistic

effects of plant derivatives and conventional chemotherapeutic

agents: An update on the cancer perspective. Medicina (Kaunas).

55(110)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Bernardi T, Bortolini O, Massi A,

Sacchetti G, Tacchini M and De Risi C: Exploring the synergy

between HPTLC and HPLC-DAD for the investigation of wine-making

by-products. Molecules. 24(3416)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Yuliet S, Nurfajar R, Sindia S, Khaerati K

and Saraswaty V: Immunomodulatory activity of Pepolo (Bischofia

javanica Blume) stem bark ethanolic extract in

Staphylococcus aureus-stimulated macrophages and anticancer

activity against MCF-7 cancer cells. J Appl Pharm Sci. 12:109–116.

2022.

|

|

55

|

Wu JS, Jiang J, Chen BJ, Wang K, Tang YL

and Liang XH: Plasticity of cancer cell invasion: Patterns and

mechanisms. Transl Oncol. 14(100899)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Tang SM, Deng XT, Zhou J, Li QP, Ge XX and

Miao L: Pharmacological basis and new insights of quercetin action

in respect to its anti-cancer effects. Biomed Pharmacother.

121(109604)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|