1. Introduction

Degenerative joint diseases include osteoarthritis

(OA), intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration (IVDD) and rheumatoid

arthritis (RA). The gradual structural and functional deterioration

of articular cartilage, subchondral bone and surrounding joint

tissues are common features, which lead to joint pain, stiffness

and functional impairment (1-3).

It is reported that degenerative joint diseases affect >250

million individuals worldwide (4).

In OA, progressive degradation of the cartilage matrix occurs, with

notable reductions in the main components of the extracellular

matrix (ECM), such as type II collagen and proteoglycans; in later

stages, osteophytes (which are outgrowths of bone at joint margins

that develop in response to cartilage loss) often form, and joint

deformities may develop (2,5). In IVDD, the nucleus pulposus (NP)

cells and annulus fibrosus cells progressively lose their viability

and function; over time, the intervertebral discs become

dehydrated, collapse and deform, causing various clinical issues

such as lower back pain (6).

Furthermore, in RA, an autoimmune disease, chronic inflammation and

synovial hyperplasia erode the articular cartilage and subchondral

bone, typically manifesting as marked joint swelling, morning

stiffness and cartilage destruction (7,8).

Regardless of the specific form, inflammation and oxidative stress

both serve roles in the pathogenesis of these diseases.

Oxidative stress is the excessive accumulation of

reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species that

surpass the scavenging capacity of endogenous antioxidant systems

(such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase and

peroxiredoxins). Oxidative stress causes cellular damage and can

lead to apoptosis or necrosis (9,10). In

tissues such as articular cartilage and intervertebral discs,

oxidative stress induces the expression of matrix-degrading enzymes

[such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs; MMP-1, -3 and -13) and

aggrecanases (such as a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with

thrombospondin motifs-4 and -5)], which accelerates the degradation

of the ECM (2,11,12).

Moreover, oxidative stress can activate associated signaling

pathways (such as the NLRP3 inflammasome), exacerbating local

inflammation (13,14). With aging or disease progression,

the capacity of joint cells to defend against free radical damage

declines. This results in an increased likelihood that oxidative

damage will accumulate, which further exacerbates joint or disc

degeneration (2,15).

Mitochondria, the organelles responsible for

oxidative phosphorylation and energy supply in cells, are the

primary sites of endogenous ROS production (1,16).

During oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondrial electron

transport chain, superoxide anions (O2-) are

generated and then converted to H2O2, OH·,

singlet oxygen and peroxynitrite by antioxidant systems such as

superoxide dismutases (SODs; such as SOD2) (17). If the levels of the

O2- exceeds this regulatory capacity, damage

on the mitochondrial proteins, membrane lipids and DNA may occur

(16). Previous studies reveal that

mitochondrial dysfunction and excess mitochondrial ROS production

are involved in numerous degenerative diseases, including OA, RA

and IVDD (5,8,18).

Therefore, protecting mitochondria and improving redox homeostasis

is a notable research focus and may be a strategy in the prevention

and treatment of degenerative joint diseases.

Mitochondrial oxidative stress results in tissue

damage in degenerative joint diseases; however, therapeutic

strategies aimed at restoring the mitochondrial redox balance are

scarce. Although conventional antioxidants (such as vitamin C,

vitamin E and N-acetylcysteine) and anti-inflammatory drugs (for

example, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen

and indomethacin, or corticosteroids such as prednisone) can

transiently alleviate symptoms, they cannot mitigate the

mitochondria-derived ROS at the source (2). Despite growing evidence that aberrant

mitochondrial ROS contribute to cartilage degradation, NP cell

senescence and synovial inflammation, only a small number of

therapeutic strategies target mitochondrial oxidative stress. At

present, the existing antioxidant approaches rely on

non-mitochondria-specific compounds, such as vitamin C, vitamin E,

N-acetylcysteine, glutathione and polyphenols (for example,

resveratrol), and clinical translation is limited (2). Therefore, an evaluation of the

mitochondria-targeted antioxidants and quality-control mechanisms

was needed in order to assess this translational gap and highlight

the novel disease-modifying treatments for OA, IVDD and RA.

2. Methods

Literature search strategy

A systematic search of PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Web of Science

(https://www.webofscience.com/) and the

Cochrane Library (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/) was carried out for

articles published between 2000 and June 2025. Search terms

included combinations of ‘osteoarthritis’ OR ‘intervertebral disc

degeneration’ OR ‘rheumatoid arthritis’ with ‘mitochondria’,

‘oxidative stress’, ‘mitophagy’, ‘MitoQ’, ‘SS-31’ and

‘mitochondrial antioxidant’. Boolean operators and Medical Subject

Headings were used as appropriate. Reference lists of relevant

reviews and clinical guidelines were also reviewed to identify

additional studies.

The inclusion criteria used were as follows: i)

Primary research or review articles written in English; ii) in

vitro, in vivo or ex vivo models of OA, IVDD or

RA; iii) interventions that directly targeted mitochondrial

function or oxidative stress; and iv) quantifiable outcomes

regarding the levels of ROS, cell survival, ECM integrity or

functional scores.

The exclusion criteria used were as follows: i)

Publications not written in English; ii) conference abstracts or

editorials; iii) duplicate reports; or iv) studies with

insufficient methodological detail.

3. Biological basis of mitochondria-targeted

antioxidant strategies in degenerative joint diseases

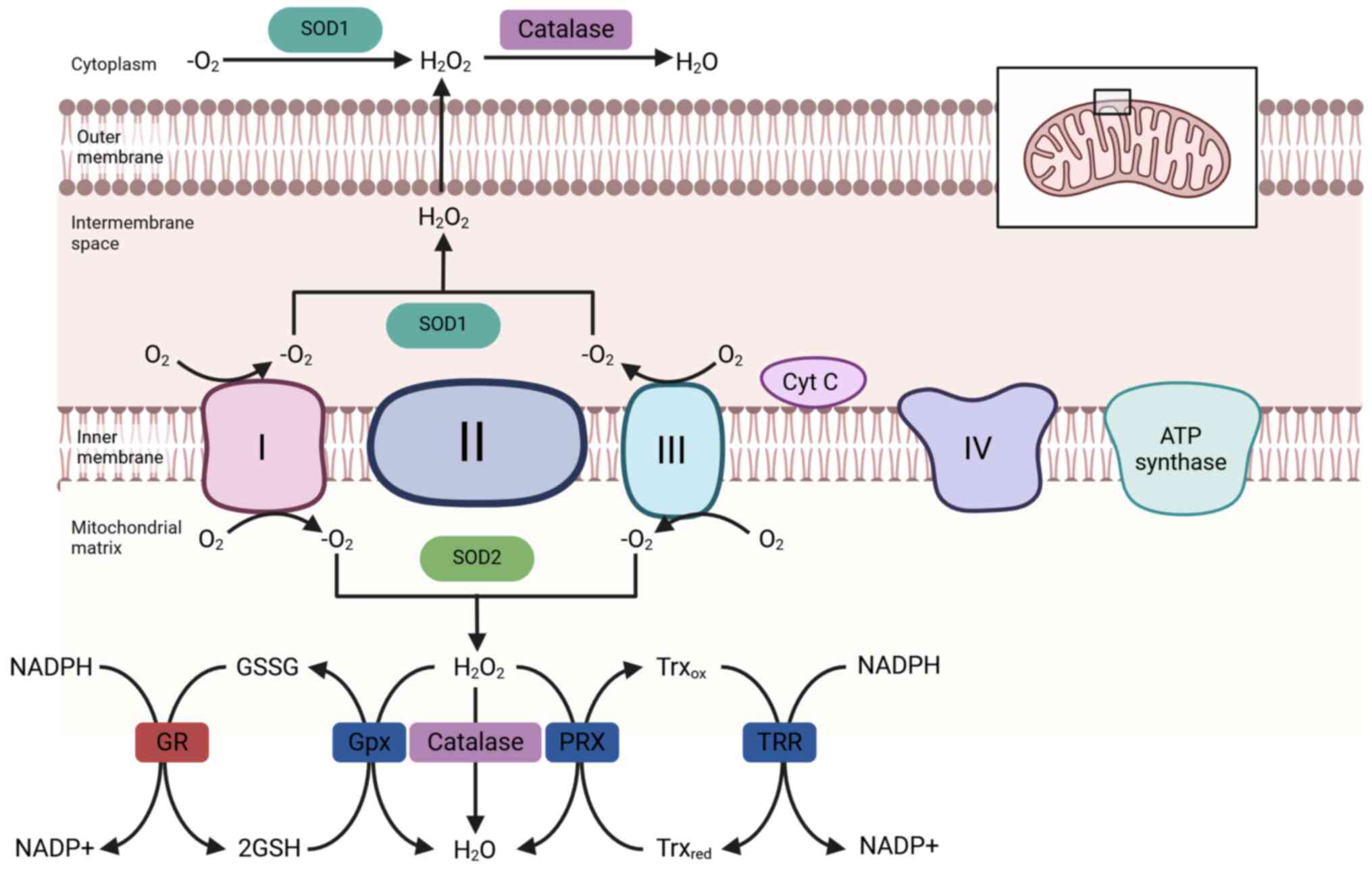

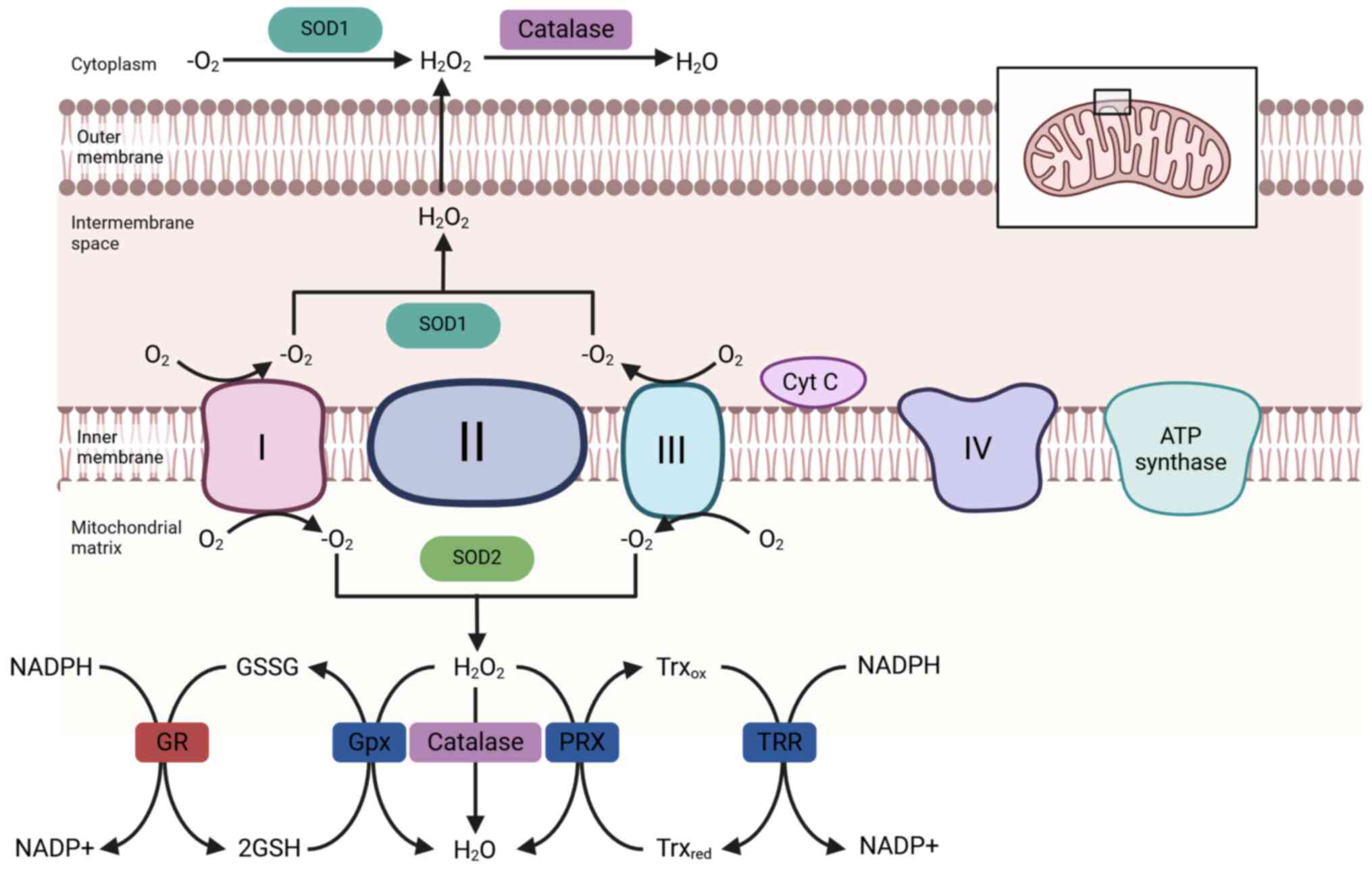

Production and scavenging of

mitochondrial ROS

Within mitochondria, 1-5% of the oxygen taken in by

the cell may ‘leak’ in the form of ROS during the activity of the

electron transport chain (19,20).

Under normal conditions, SODs located in the mitochondria (such as

SOD2, which is primarily located in the mitochondrial matrix),

peroxiredoxins and glutathione peroxidases convert or remove these

ROS, which keeps the levels of the ROS within a reasonable range

(typically at nM to low µM concentrations, such as superoxide in

the 10-100 nM range and hydrogen peroxide in the 1-10 µM range,

which act as signaling molecules) and allows them to function in

cell signal transduction and normal metabolic processes, such as

MAPK (ERK, JNK and p38), NF-κB, PI3K-Akt, hypoxia-inducible

factor-1α and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways (2,21)

(Fig. 1). However, when

mitochondrial function is impaired (due to exogenous harmful

stimuli, aging or gene mutations that inactivate complexes involved

in the electron transport chain) excessive levels of ROS can

accumulate, resulting in lipid peroxidation, oxidative protein

modifications and breaks in the DNA (16,22).

| Figure 1Schematic illustration of

mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation and the

antioxidant defense systems. During mitochondrial respiration,

electron leakage from the electron transport chain leads to the

formation of superoxide anions, which are subsequently converted to

hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals through enzymatic and

non-enzymatic reactions. To counteract oxidative stress,

mitochondria utilize several antioxidant mechanisms, such as SOD

that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide into

H2O2, which is further detoxified by Gpx and

PRX. The glutathione system, composed of reduced GSH, oxidized GSSG

and GR, maintains redox homeostasis. In parallel, the Trx/TRR

system reduces oxidized proteins and supports peroxiredoxin

activity. Cyt C is also a key electron carrier and its release into

the cytosol can trigger apoptotic signaling. Gpx, glutathione

peroxidase; PRX, peroxiredoxin; SOD, superoxide dismutase; Cyt C,

cytochrome c; GR, glutathione reductase; GSSG, glutathione

disulfide; GSH, glutathione; TRR, thioredoxin reductase; Trx,

thioredoxin; ox, oxidized; red, reduced. |

Mechanisms linking mitochondrial

dysfunction with degenerative changes in joints

Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with

degenerative changes in joint tissues by promoting apoptosis,

pyroptosis and inflammatory responses, as well as undermining

cartilage matrix integrity and normal cellular functions (23,24).

The excessive generation of mitochondrial ROS and the loss of the

mitochondrial membrane potential can cause a release of cytochrome

c. This can lead to the subsequent activation of the caspase

cascade, which induces apoptosis (13,25).

Furthermore, elevated ROS levels can promote the assembly of the

NLRP3 inflammasome, triggering pyroptosis and increasing the

inflammatory damage within joint tissues (13,26).

In addition to the aforementioned direct mechanisms

of cell death, oxidative stress activates inflammatory pathways

such as NF-κB and MAPK. These inflammatory pathways increase the

production of proinflammatory factors (such as IL-1β and TNF-α) and

MMPs, which together accelerate cartilage matrix degradation

(7,27).

As mitochondrial damage worsens, cells face an

energy deficit. An overabundance of ROS further impairs

proteoglycans and collagen, increasing the breakdown of the ECM in

the cartilage (15,28). For example, in RA, mitochondrial

dysfunction in fibroblast-like synoviocytes increases both local

inflammation and synovial hyperplasia (7). Moreover, the accumulation of ROS may

lead to cell cycle arrest, reduced chondrocyte proliferation and

the emergence of cellular senescence phenotypes (such as increased

p16 and p21 expression levels), which are observed in conditions

such as osteoporosis, OA and IVDD (29-31).

4. Research progress on

mitochondria-targeted antioxidants in degenerative joint

diseases

Mitoquinone (MitoQ)

MitoQ is a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant formed

by conjugating a ubiquinone analog with triphenylphosphonium (TPP)

through an alkyl chain. It demonstrates certain protective effects

in models of both OA and IVDD (2,32)

(Table I).

| Table IComparison of mitochondria-targeted

antioxidants in degenerative joint diseases. |

Table I

Comparison of mitochondria-targeted

antioxidants in degenerative joint diseases.

| Antioxidant | Structure and

targeting | Mechanism of

action | Evidence in OA | Evidence in

IVDD | Evidence in RA |

|---|

| MitoQ | Ubiquinone and

TPP+ | Scavenges mtROS,

stabilizes the mitochondrial membrane and downregulates

NF-κB/NLRP3 | Reduces cartilage

damage and inflammation (demonstrated in in vitro studies

and models of mice with OA) (25,32) | Reduces NP cell

apoptosis and increases ECM stability (demonstrated in rat models)

(8,40) | Limited |

| MitoTEMPO | TEMPO and

TPP+ | Removes

mitochondrial superoxide, inhibits the expression of JNK/AP-1 and

NF-κB, and promotes mitophagy | Reduces MMPs

expression levels and cartilage degeneration (demonstrated in mice

with OA) | Reduces

caspase-induced pyroptosis and increases PINK1/Parkin-induced

mitophagy (demonstrated in NP cell models) | Reduces synovial

inflammation and ROS (demonstrated in vitro) |

| SkQ1 | Plastoquinone and

TPP+ | Induces apoptosis

in neutrophils, and reduces synovial oxidative stress | Not reported | Not reported | Reduces joint

damage and the levels of cytokines (demonstrated in a rat model of

RA) |

| SS-31

(Elamipretide) | Peptide binding to

cardiolipin | Stabilizes the ETC,

reduces lipid peroxidation and preserves mitochondrial

dynamics | Increases the

synthesis of the ECM by chondrocytes and reduces senescence

(demonstrated in in vitro cellular models) | Reduces NP

apoptosis and increases mitochondrial stability (demonstrated in

in vitro LPS- and oxidative stress-induced cellular

models) | Limited |

Research in OA

In vitro studies, using chondrocyte models

induced with oxidative stress, demonstrate that MitoQ mitigates

mitochondrial damage and ECM degradation, while enhancing the

expression of anti-inflammatory genes, such as IL-10 and

TGF-β, as well as antioxidant genes including SOD2,

catalase, glutathione peroxidase 1 and

NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (2,31).

In vivo, MitoQ alleviates cartilage degeneration and reduces

the levels of inflammatory cytokines, which slows the progression

of OA (32,33).

Research in IVDD. Studies indicate that under

mechanical overload or inflammatory stimulation, intervertebral

disc tissue exhibits notable accumulation of ROS, elevated

apoptosis and impaired ECM synthesis (34,35).

MitoQ inhibits the activation of inflammatory signaling pathways

such as the NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB, and prevents the

excessive secretion of key cytokines, such as IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6

(30,32,36).

In a rat IVDD model, MitoQ administration maintains disc height and

hydration; therefore, delaying degenerative changes (6,30,36).

These findings suggest that MitoQ confers protective

effects on both articular cartilage and intervertebral discs,

potentially due to its ability to reduce mitochondrial oxidative

damage and stabilize energy metabolism.

MitoTEMPO

MitoTEMPO is a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant

formed by coupling the superoxide scavenger TEMPO with the

TPP+ cationic group, which removes mitochondrial

superoxide radicals (37,38). Multiple in vivo and in

vitro studies highlight its beneficial role in counteracting

oxidative stress and apoptosis in joint cells (27,37).

Research in OA

Under high-glucose conditions or inflammatory

stimulation, ROS levels in chondrocytes increase. Previous studies

report that MitoTEMPO blocks the JNK/activator protein-1 and NF-κB

pathways that are activated by ROS, leading to a reduction in the

expression of MMPs compared with the expression of MMPs without

MitoTEMPO treatment (27,37). Furthermore, intra-articular

injection of MitoTEMPO in mice with cholesterol-induced OA reduces

MMP-13 gene expression levels compared with vehicle-treated OA

controls. Additionally, this intervention alleviates cartilage

lesions and leads to a notable reduction in cartilage degeneration

(2).

Research in IVDD. MitoTEMPO also demonstrates

protective effects in IVDD. In NP cells with IL-1β exposure or

endplate chondrocytes with H2O2 exposure,

MitoTEMPO notably reduces the pathological increase in

mitochondrial ROS compared with the stressor-only groups without

MitoTEMPO treatment. This suppresses the activation of the caspase

cascade and pyroptosis (25,39).

When mitochondrial ROS are suppressed, PTEN-induced kinase 1

(PINK1)/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is maintained, reducing the

accumulation of damaged mitochondria in cells (25,39).

This process improves the function of NP cells and the homeostasis

of the ECM, exerting an interventional effect on IVDD.

Research in RA. Although the research on

MitoTEMPO in RA is limited, studies in synovial cell models suggest

that exogenous mitochondrial ROS scavenging can attenuate the

inflammatory cascade and ROS bursts (7,40).

Therefore, MitoTEMPO exhibits broad-spectrum antioxidant protection

by targeting mitochondria in various degenerative joint

diseases.

Plastoquinonyl-decyl-triphenylphosphonium (SkQ1)

SkQ1 is a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant derived

from plastoquinone linked to TPP (8). In a RA model, low doses of SkQ1 (on

the nM scale) suppresses the progression of arthritis and reduces

the pathological damage to cartilage and the synovium (8). Its mechanism is associated with

inducing neutrophil apoptosis, alleviating oxidative stress and

improving the joint microenvironment. Although direct evidence in

OA and IVDD is scarce, the robust mitochondrial antioxidant

properties of SkQ1 and its efficacy in autoimmune arthritis models

suggest it may hold potential value for degenerative joint diseases

as well.

Szeto-Schiller-31 (SS-31)

SS-31 (also known as Elamipretide) is a

mitochondria-targeting short peptide that binds to cardiolipin on

the inner mitochondrial membrane. This helps to stabilize the

electron transport chain and reduce the generation of ROS (41). Studies demonstrate that SS-31

improves the mitochondrial membrane potential, inhibits

inflammation and promotes the synthesis of the ECM in both

intervertebral disc cells and chondrocytes (6,42).

Additionally, SS-31 reduces mitochondrial lipid

peroxidation, a key factor in oxidative damage, and partially

reverses stress-induced cellular senescence phenotypes (43). Its ability to ameliorate

mitochondrial function also contributes to mitigating inflammatory

signaling and promoting the stability of the ECM, which is critical

for preventing tissue degeneration (44).

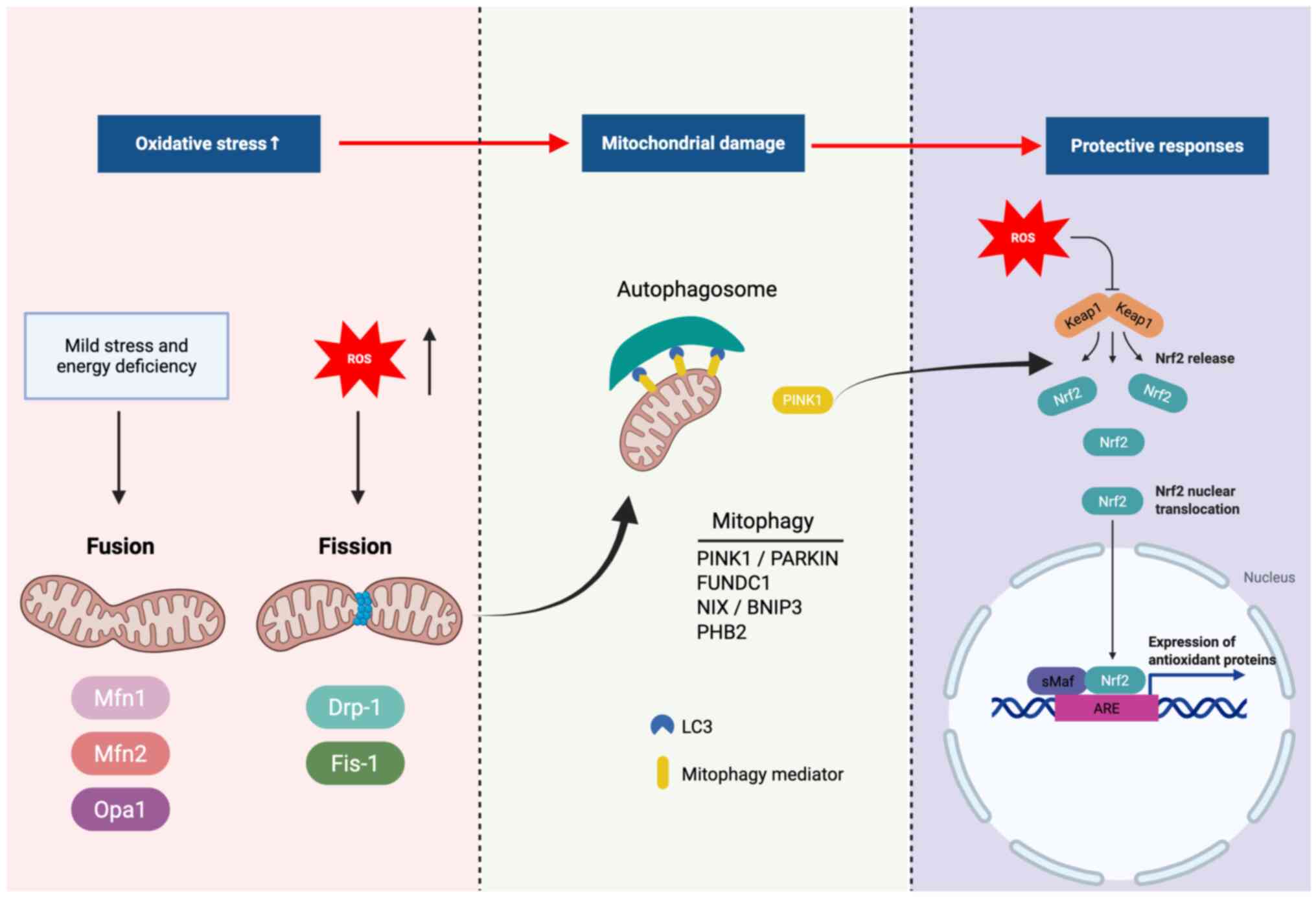

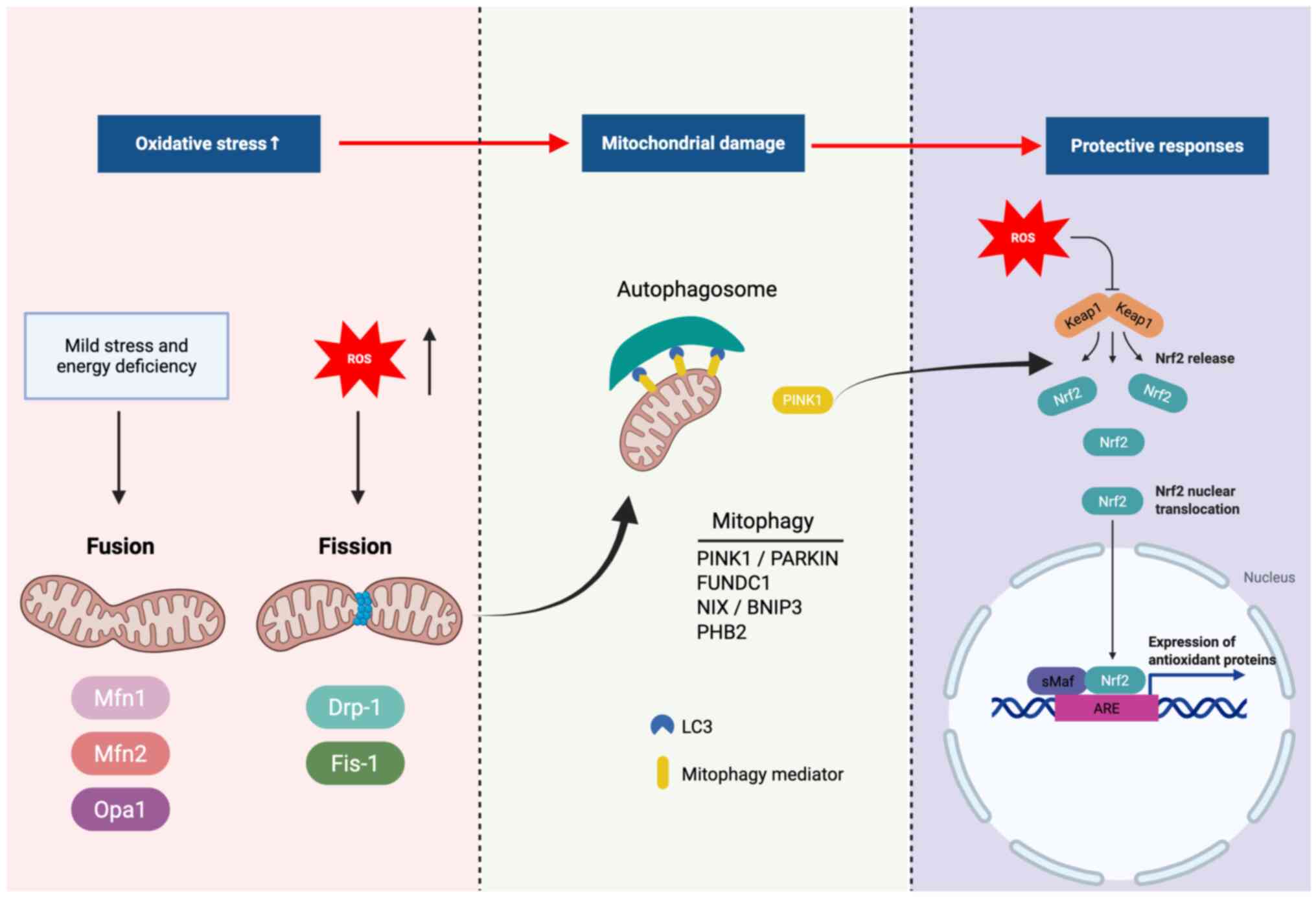

5. Other strategies targeting mitochondrial

regulatory molecules in degenerative joint diseases

Apart from the direct use of mitochondria-targeted

antioxidants, recent studies increasingly focus on mitochondrial

dynamics, mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis as indirect

methods for reducing mitochondrial ROS accumulation, which may

offer a therapeutic potential in degenerative joint diseases

(Fig. 2) (45,46).

| Figure 2Mitochondrial stress responses

following ROS-induced damage and the protective signaling pathways

that maintain mitochondrial quality. ROS overproduction disrupts

mitochondrial dynamics, leading to altered fusion (mediated by Mfn1

and 2, and Opa1) and fission (promoted by Drp1 and Fis1). Damaged

mitochondria activate mitophagy, in which PINK1 accumulates on the

outer mitochondrial membrane to recruit PARKIN, an E3 ubiquitin

ligase, facilitating ubiquitination of outer membrane proteins.

Receptors such as FUNDC1, NIX and BNIP3 interact with LC3 to

promote autophagosome formation, while PHB2 functions as an inner

membrane mitophagy receptor. Additionally, the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE

signaling axis provides antioxidant defense, with sMaf proteins

serving as transcriptional partners of Nrf2 in activating

antioxidant response elements. These pathways together coordinate

mitochondrial turnover and cytoprotective responses. ROS, reactive

oxygen species; Mfn1, mitofusin 1; Mfn2, mitofusin 2; Opa1, optic

atrophy 1; Drp1, dynamin-related protein 1; Fis1, fission protein

1; PINK1, PTEN-induced kinase 1; PARKIN, E3 ubiquitin ligase

involved in mitophagy; FUNDC1, FUN14 domain-containing protein 1;

NIX, BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3-like;

BNIP3, BCL-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3;

LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; Nrf2, nuclear

factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; sMaf, small musculoaponeurotic

fibrosarcoma oncogene homologs that dimerize with Nrf2; Keap1,

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; ARE, antioxidant response

element; PHB2, prohibitin 2. |

Regulation of PINK1/Parkin-mediated

mitophagy

The PINK1/Parkin pathway is an essential cellular

mechanism for clearing damaged mitochondria. When the mitochondrial

membrane potential decreases, PINK1 accumulates on the outer

mitochondrial membrane, recruiting Parkin to the mitochondrial

surface. Parkin then ubiquitinates several outer mitochondrial

membrane substrates, including mitofusins 1/2, voltage-dependent

anion channel 1 and translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20,

which facilitates the recognition and clearance of damaged

mitochondria through autophagy. Enhancing PINK1/Parkin-mediated

mitophagy can reduce the release of mitochondrial ROS, which

protects cells from damage (47).

Previous studies demonstrate that inhibition of leucine-rich repeat

kinase 2 can restore Parkin-mediated mitophagy and alleviate IVDD

(48,49). Taurine, a naturally occurring amino

acid derivative, promotes mitophagy by activating the PINK1/Parkin

pathway, which ameliorates IVDD (50). Additionally, knocking down the

expression of early growth response protein 1 activates

PINK1-Parkin-dependent mitophagy, which suppresses NP cell

senescence and mitochondrial damage, and slows disc degeneration

(51). Furthermore, a recent study

reveals that cellular repressor of E1A-stimulated genes 1 can

alleviate NP cell pyroptosis through the PINK1/Parkin-associated

mitophagy pathway, which improves IVDD (52).

Maintenance of mitochondrial dynamics

balance (fission and fusion)

An imbalance in mitochondrial fission and fusion

also leads to the excessive generation of ROS (36). Under pathological stimuli such as

mechanical compression, excessive mitochondrial fission (mediated

by dynamin-related protein 1) separates damaged mitochondrial

segments; however, impaired fusion processes (mediated by mitofusin

1/2 and optic atrophy 1) result in the accumulation of fragmented

and dysfunctional mitochondria, causing a persistent elevation of

ROS (36). Antioxidants such as

MitoQ not only reduce ROS levels but also attenuate excessive

fission and promote fusion of functionally intact mitochondria

(36,53). Therefore, the modulation of proteins

involved in mitochondrial dynamics or the combined use with

mitochondrial antioxidants may be a future therapeutic direction

for joint degeneration.

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor 2 (Nrf2)-Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)

antioxidant signaling pathway and mitochondria

Nrf2, a central transcription factor for cellular

antioxidant responses, induces the expression of antioxidant genes

including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone

dehydrogenase 1 and SOD2(32).

When mitochondrial ROS levels increase, oxidative modification of

Keap1 leads to the stabilization and nuclear translocation of Nrf2,

which then activates antioxidant gene expression to alleviate

oxidative stress and maintain cellular homeostasis (54). A recent study demonstrates that both

pharmacological and genetic activation of the Nrf2 pathway serves a

crucial role in mitigating inflammatory responses and apoptosis in

joint cartilage and IVD tissues (49). For example, Kartogenin-loaded

hydrogel promotes IVD repair by protecting mesenchymal stem cells

from oxidative stress via the Nrf2/Thioredoxin-interacting

protein/NLRP3 axis, which reduces inflammation and cellular

apoptosis (55). Additionally,

astaxanthin activates the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, which suppresses

oxidative stress and prevents cartilage endplate degeneration by

inhibiting apoptosis and the degradation of the ECM (56).

Other regulatory molecules or

bioactive substances. Deacetylases [such as sirtuin (SIRT)3 and

1]

SIRT family proteins serve essential roles in

mitochondrial homeostasis, redox balance and the regulation of

energy metabolism (25,28). For example, SIRT3, localized in

mitochondria, deacetylates and activates key antioxidant enzymes

such as manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2), isocitrate

dehydrogenase 2 and catalase, which enhances mitochondrial ROS

detoxification (28). Upregulation

of SIRT3 suppresses cellular senescence and inflammation in joint

cells.

A study by Guo et al (57) reveals that dysregulation of SIRT3

and its metabolic network, including downstream effectors such as

isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 and manganese SOD, serves a role in

mitochondrial oxidative stress and cartilage degradation in OA.

This suggests that restoring the activity of SIRT3 may serve as a

therapeutic approach to delay joint degeneration (57).

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α (PGC-1α)

pathway. The AMPK-PGC-1α signaling axis promotes mitochondrial

biogenesis and the expression of antioxidant enzymes. A study by

Yang et al (58)

demonstrates that exposure to advanced glycation end-products

represses the AMPKα-SIRT1-PGC-1α pathway in osteoarthritic

chondrocytes, with reductions in PGC-1α expression levels compared

with untreated control cells, resulting in impaired mitochondrial

biogenesis and antioxidant defense. However, the study by Li et

al (59) demonstrates that

adipokine omentin-1 can activate the AMPK-PGC-1α pathway, promoting

mitochondrial biogenesis in chondrocytes and slowing OA

progression. The study by Yang et al (58) demonstrates that advanced glycation

end products inhibit the AMPK-SIRT1-PGC-1α pathway, which induces

mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation in chondrocytes. This

suggests the antioxidant and anti-aging properties of the

AMPK-SIRT1-PGC-1α pathway (58).

Additionally, the study by Guo et al

(57) reveals that activation of

the AMPK-PGC-1α pathway not only restores energy metabolism but

also reduces the accumulation of ROS and the expression of

proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, in

degenerative joint diseases. This demonstrates its potential role

as a therapeutic axis (57).

Itaconate derivatives (such as 4-octyl

itaconate). A previous study indicates that exogenous itaconate

reduces inflammatory responses and inhibits the generation of

mitochondrial ROS (54). Zinc-based

metal-organic super containers, such as 4-octyl itaconate

(4-OI)@Zn-NH-pyr, demonstrates enhanced mitochondrial targeting and

ROS-scavenging activity compared with free 4-OI alone, which

alleviates proinflammatory states in arthritis models (54).

Additionally, novel mitochondria-targeted

nanomedicines such as Mn3O4/UIO-TPP nanozymes

scavenge mitochondrial ROS and restore mitochondrial function in OA

cartilage, demonstrating potential therapeutic effects in rat

models with anterior cruciate ligament transection induced OA

(60,61). These nanozymes represent a promising

material-based extension of mitochondrial antioxidant therapy and

support the feasibility of precision mitochondria-targeted

intervention (62).

Crosstalk between mitochondria and the

endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in joint degeneration

Mitochondria and the ER are functionally connected

via mitochondria-associated membranes, which coordinate calcium

signaling, lipid exchange and cellular stress responses. In

degenerative joint diseases, this interplay becomes dysregulated,

which contributes to oxidative injury and inflammation (63).

ER stress promotes the release of Ca2+

through inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors, while excessive

uptake of Ca2+ by the mitochondria via the mitochondrial

calcium uniporter leads to the overproduction of ROS, mitochondrial

dysfunction and apoptosis (14).

Furthermore, ER stress activates proapoptotic pathways (such as

protein kinase R-like ER kinase-activating transcription factor

4-CHOP) and promotes the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome

(64).

In addition, ion channels (such as transient

receptor potential cation channel, subfamily V, member 4)

participate in mechano-oxidative signaling in joint cells, and

their dysregulation may further exacerbate mitochondrial stress

(65). Targeting ER-mitochondria

interactions or associated Ca2+ channels may offer new

therapeutic avenues in OA, IVDD and RA.

6. Crosstalk in immunometabolism:

Mitochondrial oxidative stress and the immune system in

degenerative joint diseases

Mitochondrial oxidative stress not only contributes

to direct tissue damage but also serves a role in modulating immune

responses, which are involved in the pathogenesis of OA, IVDD and

RA. Both innate immune cells, such as macrophages, dendritic cells,

neutrophils and natural killer cells, and adaptive immune cells,

including T cells and B cells, respond to and are regulated by

mitochondrial metabolism and ROS signaling, forming an

interconnected immunometabolic axis (66,67).

Innate immunity and mitochondrial

ROS

Innate immune cells, such as macrophages and

neutrophils, are sensitive to mitochondrial ROS. In RA and IVDD,

macrophages polarize toward a proinflammatory (M1-like) phenotype

under oxidative stress conditions, leading to an enhanced

production of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, which further exacerbates

tissue inflammation and matrix degradation (68). Mitochondrial ROS act as secondary

messengers to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, a key inflammatory

complex that promotes caspase-1 activation and IL-1β/IL-18

maturation, which accelerates pyroptosis in disc and synovial

tissues (69).

Neutrophils also exhibit enhanced respiratory bursts

and NETosis in the presence of mitochondrial ROS, which contributes

to synovial inflammation and cartilage degradation in RA (70). Toll-like receptors (TLRs),

especially TLR2 and 4, recognize damage-associated molecular

patterns (such as mitochondrial DNA and cardiolipin) that are

released from stressed mitochondria. This activates the myeloid

differentiation primary response protein 88-dependent signaling

pathway and NF-κB-induced transcription of proinflammatory

cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 (71,72).

Adaptive immunity and oxidative

microenvironment

T cell differentiation and function are dependent on

metabolism. Under elevated ROS conditions, mitochondrial

dysfunction promotes a T helper 17 phenotype in CD4+ T

cells, promoting proinflammatory responses in RA and OA synovium

(73,74). Regulatory T cells, which rely on

oxidative phosphorylation for their function, are suppressed in

oxidative microenvironments, which further amplifies inflammation

(73).

B cells are also influenced by mitochondrial

metabolism, with mitochondrial ROS promoting autoantibody

production and immune complex deposition in RA (75). Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants

such as MitoQ and SkQ1 dampen the activation of T cells and the

secretion of cytokines, suggesting that the modulation of

mitochondrial ROS may re-establish immune homeostasis in

degenerative joint diseases (76).

Cytokines, chemokines and the

mitochondrial stress response

Cytokines, such as IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6, are not

only induced by mitochondrial ROS but also feedback to further

disrupt mitochondrial integrity and function. These cytokines

impair mitochondrial membrane potential, increase the generation of

ROS and inhibit mitophagy, forming a positive feedback loop of

oxidative inflammation (77).

However, anti-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-10) may promote

mitophagy and mitochondrial quality control by activating pathways

such as SIRT3 or AMPK-PGC-1α (78).

Chemokines, such as chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2

and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 8, recruit immune cells into

inflamed joints and are also modulated by mitochondrial oxidative

stress (70). Therefore,

therapeutic strategies targeting mitochondrial pathways may reduce

tissue damage and immune cell infiltration.

7. Clinical prospects and challenges

Limitations of animal models and

preclinical studies

Although mitochondria-targeted antioxidants such as

MitoQ, MitoTEMPO and SkQ1 reveal notable protective effects on

joints in animal models (including rodents such as mice and rats,

mid-sized models such as rabbits, and large animals such as dogs

and sheep), the pathological processes in animal models are more

acute or controlled compared with clinical populations. Therefore,

these animal models do not fully replicate the chronic, long-term

degenerative processes observed in humans (79). Additionally, there are notable

differences in pharmacokinetics and drug sensitivity in different

species (80). Therefore,

translating results from animal studies into clinical applications

necessitates further validation through extensive clinical trials

(8,18,32).

Administration methods and safety

considerations

The majority of studies on mitochondria-targeted

antioxidants rely on intra-articular injections or local

administration (79,81). Although several

mitochondria-targeted antioxidants, such as MitoQ, SkQ1 (Visomitin)

and to an extent MitoTEMPO, can be administered orally, systemic

delivery raises concerns regarding bioavailability, mitochondrial

targeting efficiency, and systemic safety profiles (2,32).

Local injections also have risks of tissue trauma and infection.

Advancements in drug delivery systems, such as hydrogels and

nanocarriers combined with mitochondria-targeting ligands, may

overcome these limitations. However, achieving efficient, sustained

and localized drug release at the joint is still challenging at

present (3,6,82).

Potential side effects of long-term

medication

While drugs such as MitoQ and SkQ1 demonstrate good

tolerability at low doses [for example, SkQ1 at 0.25-1.25

nmol/kg/day (0.13-0.70 µg/kg/day) in rat models and MitoQ at ~20

mg/day in human trials] (8),

long-term administration (defined as continuous dosing for 3-6

months or longer in preclinical and clinical studies) requires

vigilant monitoring to avoid causing redox imbalances in normal

tissues. Additionally, moderate levels of ROS serve critical

physiological roles in signaling and tissue repair in degenerative

joint diseases. Excessive clearance of ROS may disrupt essential

cellular signaling pathways (1,15).

Therefore, calibrating the dose and duration of

mitochondria-targeted antioxidants is crucial for clinical

application.

Combination therapies

Numerous studies increasingly advocate for combining

mitochondria-targeted antioxidants (such as MitoQ, SkQ1 and

MitoTEMPO) with autophagy regulators (such as apigenin and

rapamycin), inflammasome inhibitors (such as MCC950 and CTSB

inhibitors), growth factors (such as TGF-β and IGF-1) or

conventional anti-inflammatory medications (such as non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs and disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs)

in order to achieve synergistic therapeutic effects on degenerative

joint diseases (7,62). For example, combining MitoTEMPO with

autophagy activators, such as salidroside, honokiol or urolithin A,

simultaneously reduces excessive ROS and increases the clearance

rate of damaged mitochondria, which potentially inhibits apoptosis

in cartilage or intervertebral discs (83).

In addition, cellular and organelle-level strategies

enhance mitochondrial restoration. One such approach is

mitochondrial transplantation, in which healthy exogenous

mitochondria are delivered into dysfunctional cells to rescue

energy production and reduce oxidative stress (84). Recent studies demonstrate that

mitochondrial transplantation improves joint tissue homeostasis and

attenuates degeneration in in vitro chondrocyte and NP cell

models, as well as in vivo mice with destabilization of the

medial meniscus-induced OA and rat with needle puncture-induced

IVDD models (85,86). This strategy may be biologically

complementary to chemical antioxidant therapies.

Furthermore, future therapeutic paradigms may

involve mitochondrial genome editing to correct mitochondrial DNA

mutations that are associated with joint degeneration. Emerging

tools such as mitochondria-targeted zinc finger nucleases and

mitochondria-targeted transcription activator-like effector

nucleases demonstrate potential in restoring mitochondrial

integrity and function in tissues with OA (87,88).

Although these technologies are still mostly experimental, they

could potentially be used in precision mitochondrial medicine for

degenerative joint diseases in the future (87).

8. Conclusions

Mitochondrial dysfunction and an excessive

generation of ROS are central pathological mechanisms underlying

degenerative joint diseases, including OA, IVDD and RA. The present

study demonstrated the role of mitochondrial oxidative damage in

promoting disease progression, from the degradation of the

cartilage ECM in OA and NP cell death in IVDD, to chronic synovitis

and immune activation in RA. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants,

such as MitoQ, MitoTEMPO, SkQ1 and SS-31, demonstrate potential in

mitigating oxidative stress and slowing disease deterioration.

These findings provided theoretical support for a paradigm shift

from symptom-based management toward mitochondria-centered

interventions.

At present, despite promising preclinical data, the

evidence is mostly limited to in vitro and small-animal

studies, such as mice and rats, with scarce validation in human

tissues or large-scale clinical settings. Additionally, the

heterogeneity of degenerative joint diseases further complicates

the interpretation of therapeutic efficacy. In particular,

differences in mitochondrial activity, ROS levels and drug

responsiveness among OA, IVDD and RA are yet to be fully

characterized. Furthermore, the lack of multicenter randomized

clinical trials evaluating dosing, safety profiles and delivery

methods for mitochondria-targeted antioxidants is a notable

limitation. Additionally, the majority of studies overlook

long-term outcomes and potential off-target effects, especially in

elderly or comorbid populations.

Future studies should investigate the temporal and

spatial regulation of mitochondrial ROS in specific joint tissues

and immune cell subpopulations. In particular, the association

between mitochondrial dysfunction and epigenetic regulation,

cytokine signaling or metabolic reprogramming warrants further

investigation. Elucidating how mitochondrial stress interacts with

cartilage calcification, subchondral bone remodeling and synovial

hyperplasia may reveal additional therapeutic checkpoints. The use

of advanced models such as patient-derived organoids, single-cell

mitochondrial profiling and spatial transcriptomics may aid

mechanistic investigations. Additionally, mitochondrial-nuclear

crosstalk or sex-specific mitochondrial responses should also be

investigated in the future.

Clinical translation should prioritize the

development of delivery systems, including hydrogels, nanoparticles

and scaffold-based platforms that enable a localized, sustained

release of mitochondria-targeted antioxidants (such as MitoQ,

MitoTEMPO or SkQ1). Additionally, their combination with autophagy

enhancers (such as rapamycin, spermidine or resveratrol) or

regenerative factors [such as bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP)-2

and -7] or TGF-β) at degenerative sites should be investigated.

Furthermore, integrating mitochondria-targeted antioxidants with

mitophagy enhancers (such as rapamycin, urolithin A and

salidroside), immune modulators (such as IL-17A antibodies, Treg

enhancers and fumaric acid derivatives) or regenerative therapies

(such as stem cells or exosome-based systems) may also offer a

therapeutic effect. Such combination regimens may synergistically

halt or reverse disease progression. Furthermore, precision

medicine frameworks leveraging genetic, metabolic or imaging

biomarkers may allow for personalized dosing and treatment

selection, which may also enhance therapeutic outcomes.

Mitochondria-centered therapies involve

multi-disciplinary teams from orthopedics, immunology, geriatrics

and bioengineering. However, a number of controversies remain

unresolved. For example, contradictory findings regarding the role

of ROS as only deleterious vs. the role of ROS as signaling

mediators in joint homeostasis. Moreover, the possibility that

prolonged ROS suppression might impair physiological defense

mechanisms or tissue remodeling should be investigated.

Interdisciplinary dialogue and standardized methodological

approaches will likely be required to address these issues and

guide the rational design of future therapies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YH designed the study and drafted the manuscript. XY

summarized the comments from the reviewers, drafted the responses

and contributed to manuscript revision and language editing. TZ

contributed to the literature review and assisted in data

interpretation. YG revised the manuscript. JS designed the present

study, revised the manuscript and supervised the project. All

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Martin JA, Martini A, Molinari A, Morgan

W, Ramalingam W, Buckwalter JA and McKinley TO: Mitochondrial

electron transport and glycolysis are coupled in articular

cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 20:323–329. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Bolduc JA, Collins JA and Loeser RF:

Reactive oxygen species, aging and articular cartilage homeostasis.

Free Radic Biol Med. 132:73–82. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Chen Q, Qian Q, Xu H, Zhou H, Chen L, Shao

N, Zhang K, Chen T, Tian H, Zhang Z, et al: Mitochondrial-targeted

metal-phenolic nanoparticles to attenuate intervertebral disc

degeneration: alleviating oxidative stress and mitochondrial

dysfunction. ACS Nano. 18:8885–8905. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hunter DJ and Bierma-Zeinstra S:

Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 393:1745–1759. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Nasto LA, Robinson AR, Ngo K, Clauson CL,

Dong Q, St Croix C, Sowa G, Pola E, Robbins PD, Kang J, et al:

Mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a causal

role in aging-related intervertebral disc degeneration. J Orthop

Res. 31:1150–1157. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Wang Y, Deng M, Wu Y, Zheng C, Zhang F,

Guo C, Zhang B, Hu C, Kong Q and Wang Y: A multifunctional

mitochondria-protective gene delivery platform promote

intervertebral disc regeneration. Biomaterials.

317(123067)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Al-Azab M, Qaed E, Ouyang X, Elkhider A,

Walana W, Li H, Li W, Tang Y, Adlat S, Wei J, et al:

TL1A/TNFR2-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction of fibroblast-like

synoviocytes increases inflammatory response in patients with

rheumatoid arthritis via reactive oxygen species generation. FEBS

J. 287:3088–3104. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Andreev-Andrievskiy AA, Kolosova NG,

Stefanova NA, Lovat MV, Egorov MV, Manskikh VN, Zinovkin RA, Galkin

II, Prikhodko AS, Skulachev MV and Lukashev AN: Efficacy of

mitochondrial antioxidant plastoquinonyl-decyl-triphenylphosphonium

bromide (SkQ1) in the rat model of autoimmune arthritis. Oxid Med

Cell Longev. 2016(8703645)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Saeidnia S and Abdollahi M: Toxicological

and pharmacological concerns on oxidative stress and related

diseases. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 273:442–455. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Burton GJ and Jauniaux E: Oxidative

stress. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 25:287–299.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Cao G, Yang S, Cao J, Tan Z, Wu L, Dong F,

Ding W and Zhang F: the role of oxidative stress in intervertebral

disc degeneration. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2022(2166817)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Wen P, Zheng B, Zhang B, Ma T, Hao L and

Zhang Y: The role of ageing and oxidative stress in intervertebral

disc degeneration. Front Mol Biosci. 9(1052878)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Peng X, Zhang C, Zhou ZM, Wang K, Gao JW,

Qian ZY, Bao JP, Ji HY, Cabral VLF and Wu XT: A20 attenuates

pyroptosis and apoptosis in nucleus pulposus cells via promoting

mitophagy and stabilizing mitochondrial dynamics. Inflamm Res.

71:695–710. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Li W, Cao T, Luo C, Cai J, Zhou X, Xiao X

and Liu S: Crosstalk between ER stress, NLRP3 inflammasome, and

inflammation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 104:6129–6140.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Bartell SM, Kim HN, Ambrogini E, Han L,

Iyer S, Serra Ucer S, Rabinovitch P, Jilka RL, Weinstein RS, Zhao

H, et al: FoxO proteins restrain osteoclastogenesis and bone

resorption by attenuating H2O2 accumulation. Nat Commun.

5(3773)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kim J, Xu M, Xo R, Mates A, Wilson GL,

Pearsall AW IV and Grishko V: Mitochondrial DNA damage is involved

in apoptosis caused by pro-inflammatory cytokines in human OA

chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 18:424–432. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Palma FR, He C, Danes JM, Paviani V,

Coelho DR, Gantner BN and Bonini MG: Mitochondrial superoxide

dismutase: What the established, the intriguing, and the novel

reveal about a key cellular redox switch. Antioxid Redox Signal.

32:701–714. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Farnaghi S, Prasadam I, Cai G, Friis T, Du

Z, Crawford R, Mao X and Xiao Y: Protective effects of

mitochondria-targeted antioxidants and statins on

cholesterol-induced osteoarthritis. FASEB J. 31:356–367.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Liu Y, Fiskum G and Schubert D: Generation

of reactive oxygen species by the mitochondrial electron transport

chain. J Neurochem. 80:780–787. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Murphy MP: How mitochondria produce

reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 417:1–13. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Valcárcel-Ares MN, Riveiro-Naveira RR,

Vaamonde-García C, Loureiro J, Hermida-Carballo L, Blanco FJ and

López-Armada MJ: Mitochondrial dysfunction promotes and aggravates

the inflammatory response in normal human synoviocytes.

Rheumatology (Oxford). 53:1332–1343. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Cui H, Kong Y and Zhang H: Oxidative

stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. J Signal Transduct.

2012(646354)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Blanco FJ, López-Armada MJ and Maneiro E:

Mitochondrial dysfunction in osteoarthritis. Mitochondrion.

4:715–728. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Early JO, Fagan LE, Curtis AM and Kennedy

OD: Mitochondria in injury, inflammation and disease of articular

skeletal joints. Front Immunol. 12(695257)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ma Z, Tang P, Dong W, Lu Y, Tan B, Zhou N,

Hao J, Shen J and Hu Z: SIRT1 alleviates IL-1β induced nucleus

pulposus cells pyroptosis via mitophagy in intervertebral disc

degeneration. Int Immunopharmacol. 107(108671)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Hu Z, Wang Y, Gao X, Zhang Y, Liu C, Zhai

Y, Chang X, Li H, Li Y, Lou J and Li C: Optineurin-mediated

mitophagy as a potential therapeutic target for intervertebral disc

degeneration. Front Pharmacol. 13(893307)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Ansari MY, Ahmad N, Voleti S, Wase SJ,

Novak K and Haqqi TM: Mitochondrial dysfunction triggers a

catabolic response in chondrocytes via ROS-mediated activation of

the JNK/AP1 pathway. J Cell Sci. 133(jcs247353)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Song Y, Li S, Geng W, Luo R, Liu W, Tu J,

Wang K, Kang L, Yin H, Wu X, et al: Sirtuin 3-dependent

mitochondrial redox homeostasis protects against AGEs-induced

intervertebral disc degeneration. Redox Biol. 19:339–353.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wu C, Luo J, Liu Y, Fan J, Shang X, Liu R,

Ye C, Yang J and Cao H: Doxorubicin suppresses chondrocyte

differentiation by stimulating ROS production. Eur J Pharm Sci.

167(106013)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Li BL, Liu X, Gao M, Zhang F, Chen X, He

Z, Wang J, Tian W, Chen D, Zhou Z and Liu S: Programmed NP cell

death induced by mitochondrial ROS in a one-strike loading disc

degeneration organ culture model. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2021(5608133)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Shao Y, Zhang H, Guan H, Wu C, Qi W, Yang

L, Yin J, Zhang H, Liu L, Lu Y, et al: PDZK1 protects against

mechanical overload-induced chondrocyte senescence and

osteoarthritis by targeting mitochondrial function. Bone Res.

12(41)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Hou L, Wang G, Zhang X, Lu F, Xu J, Guo Z,

Lin J, Zheng Z, Liu H, Hou Y, et al: Mitoquinone alleviates

osteoarthritis progress by activating the NRF2-Parkin axis.

iScience. 26(107647)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Poudel SB, Ruff RR, Yildirim G, Miller RA,

Harrison DE, Strong R, Kirsch T and Yakar S: Development of primary

osteoarthritis during aging in genetically diverse UM-HET3 mice.

Arthritis Res Ther. 26(118)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Tisherman R, Coelho P, Phillibert D, Wang

D, Dong Q, Vo N, Kang J and Sowa G: NF-κB signaling pathway in

controlling intervertebral disk cell response to inflammatory and

mechanical stressors. Phys Ther. 96:704–711. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Wang F, Cai F, Shi R, Wang XH and Wu XT:

Aging and age related stresses: A senescence mechanism of

intervertebral disc degeneration. Osteoarthritis Cartilage.

24:398–408. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kang L, Liu S, Li J, Tian Y, Xue Y and Liu

X: The mitochondria-targeted anti-oxidant MitoQ protects against

intervertebral disc degeneration by ameliorating mitochondrial

dysfunction and redox imbalance. Cell Prolif.

53(e12779)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Laiguillon MC, Courties A, Houard X,

Auclair M, Sautet A, Capeau J, Fève B, Berenbaum F and Sellam J:

Characterization of diabetic osteoarthritic cartilage and role of

high glucose environment on chondrocyte activation: Toward

pathophysiological delineation of diabetes mellitus-related

osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 23:1513–1522.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Ansari MY, Ball HC, Wase SJ, Novak K and

Haqqi TM: Lysosomal dysfunction in osteoarthritis and aged

cartilage triggers apoptosis in chondrocytes through BAX mediated

release of Cytochrome c. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 29:100–112.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Kang L, Liu S, Li J, Tian Y, Xue Y and Liu

X: Parkin and Nrf2 prevent oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in

intervertebral endplate chondrocytes via inducing mitophagy and

anti-oxidant defenses. Life Sci. 243(117244)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

McGarry T, Biniecka M, Gao W, Cluxton D,

Canavan M, Wade S, Wade S, Gallagher L, Orr C, Veale DJ and Fearon

U: Resolution of TLR2-induced inflammation through manipulation of

metabolic pathways in Rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Rep.

7(43165)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Szeto HH, Liu S, Soong Y, Alam N, Prusky

GT and Seshan SV: Protection of mitochondria prevents high-fat

diet-induced glomerulopathy and proximal tubular injury. Kidney

Int. 90:997–1011. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Peng X, Wang K, Zhang C, Bao JP, Vlf C,

Gao JW, Zhou ZM and Wu XT: The mitochondrial antioxidant SS-31

attenuated lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis and pyroptosis of

nucleus pulposus cells via scavenging mitochondrial ROS and

maintaining the stability of mitochondrial dynamics. Free Radic

Res. 55:1080–1093. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhang X, Eliasberg CD and Rodeo SA:

Mitochondrial dysfunction and potential mitochondrial protectant

treatments in tendinopathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1490:29–41.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Siekacz K, Piotrowski WJ, Iwański MA,

Górski P and Białas AJ: The role of interaction between

mitochondria and the extracellular matrix in the development of

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2021(9932442)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

An F, Zhang J, Gao P, Xiao Z, Chang W,

Song J, Wang Y, Ma H, Zhang R, Chen Z and Yan C: New insight of the

pathogenesis in osteoarthritis: the intricate interplay of

ferroptosis and autophagy mediated by mitophagy/chaperone-mediated

autophagy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 11(1297024)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Wu J, Zhou X, Xu X and Xie J: A molecular

chemical perspective: mitochondrial dynamics is not a bystander of

cartilage diseases. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 8:1473–1497.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Xiao B, Goh JY, Xiao L, Xian H, Lim KL and

Liou YC: Reactive oxygen species trigger Parkin/PINK1

pathway-dependent mitophagy by inducing mitochondrial recruitment

of Parkin. J Biol Chem. 292:16697–16708. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Lin J, Zheng X, Zhang Z, Zhuge J, Shao Z,

Huang C, Jin J, Chen X, Chen Y, Wu Y, et al: Inhibition of LRRK2

restores parkin-mediated mitophagy and attenuates intervertebral

disc degeneration. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 29:579–591.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Zeng Z, Zhou X and Wang Y, Cao H, Guo J,

Wang P, Yang Y and Wang Y: Mitophagy-A new target of bone disease.

Biomolecules. 12(1420)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Lin S, Li T, Zhang B and Wang P: Taurine

rescues intervertebral disc degeneration by activating mitophagy

through the PINK1/Parkin pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

739(150587)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Wu ZL, Wang KP, Chen YJ, Song W, Liu Y,

Zhou KS, Mao P, Ma Z and Zhang HH: Knocking down EGR1 inhibits

nucleus pulposus cell senescence and mitochondrial damage through

activation of PINK1-Parkin dependent mitophagy, thereby delaying

intervertebral disc degeneration. Free Radic Biol Med. 224:9–22.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Zhang Y, Xing D, Liu Y, Sha S, Xiao Y, Liu

Z, Yin Q, Gao Z and Liu W: CREG1 attenuates intervertebral disc

degeneration by alleviating nucleus pulposus cell pyroptosis via

the PINK1/Parkin-related mitophagy pathway. Int Immunopharmacol.

147(113974)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Cheung C, Tu S, Feng Y, Wan C, Ai H and

Chen Z: Mitochondrial quality control dysfunction in

osteoarthritis: Mechanisms, therapeutic strategies & future

prospects. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 125(105522)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Luchkova A, Mata A and Cadenas S: Nrf2 as

a regulator of energy metabolism and mitochondrial function. FEBS

Lett. 598:2092–2105. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Wang F, Guo K, Nan L, Wang S, Lu J, Wang

Q, Ba Z, Huang Y and Wu D: Kartogenin-loaded hydrogel promotes

intervertebral disc repair via protecting MSCs against reactive

oxygen species microenvironment by Nrf2/TXNIP/NLRP3 axis. Free

Radic Biol Med. 204:128–150. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Yang G, Liu X, Jing X, Wang J, Wang H,

Chen F, Wang W, Shao Y and Cui X: Astaxanthin suppresses oxidative

stress and calcification in vertebral cartilage endplate via

activating Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol.

119(110159)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Guo P, Alhaskawi A, Adel Abdo Moqbel S and

Pan Z: Recent development of mitochondrial metabolism and

dysfunction in osteoarthritis. Front Pharmacol.

16(1538662)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Yang Q, Shi Y, Jin T, Duan B and Wu S:

Advanced glycation end products induced mitochondrial dysfunction

of chondrocytes through repression of AMPKα-SIRT1-PGC-1α pathway.

Pharmacology. 107:298–307. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Li Z, Zhang Y, Tian F, Wang Z, Song H,

Chen H and Wu B: Omentin-1 promotes mitochondrial biogenesis via

PGC1α-AMPK pathway in chondrocytes. Arch Physiol Biochem.

129:291–297. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Zhang S, Cai J, Yao Y, Huang L, Zheng L

and Zhao J: Mitochondrial-targeting Mn3O4/UIO-TPP nanozyme scavenge

ROS to restore mitochondrial function for osteoarthritis therapy.

Regen Biomater. 10(rbad078)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Wang SH, Xu XL and Chen W: How do

organelle-targeting nanotherapeutics treat inflammatory diseases? A

comprehensive review of the literature. Int J Nanomedicine.

20:7133–7152. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Chen X, Li C, Cao X, Jia X, Chen X, Wang

Z, Xu W, Dai F and Zhang S: Mitochondria-targeted supramolecular

coordination container encapsulated with exogenous itaconate for

synergistic therapy of joint inflammation. Theranostics.

12:3251–3272. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Kan S, Duan M, Liu Y, Wang C and Xie J:

Role of mitochondria in physiology of chondrocytes and diseases of

osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Cartilage. 13

(2_suppl):1102S–1121S. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Liu X, Chen Y, Wang H, Wei Y, Yuan Y, Zhou

Q, Fang F, Shi S, Jiang X, Dong Y and Li X: Microglia-derived IL-1β

promoted neuronal apoptosis through ER stress-mediated signaling

pathway PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP upon arsenic exposure. J Hazard Mater.

417(125997)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Yan Z, He Z, Jiang H and Zhang Y, Xu Y and

Zhang Y: TRPV4-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction induces

pyroptosis and cartilage degradation in osteoarthritis via the

Drp1-HK2 axis. Int Immunopharmacol. 123(110651)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Li P, Zhou M, Wang J, Tian J, Zhang L, Wei

Y, Yang F, Xu Y and Wang G: Important role of mitochondrial

dysfunction in immune triggering and inflammatory response in

rheumatoid arthritis. J Inflamm Res. 17:11631–11657.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Hu K, Song M, Song T, Jia X and Song Y:

Osteoimmunology in osteoarthritis: Unraveling the interplay of

immunity, inflammation, and joint degeneration. J Inflamm Res.

18:4121–4142. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Dou Y, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Sun X, Liu X, Li B

and Yang Q: Role of macrophage in intervertebral disc degeneration.

Bone Res. 13(15)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Wang S, Wang H, Feng C, Li C, Li Z, He J

and Tu C: The regulatory role and therapeutic application of

pyroptosis in musculoskeletal diseases. Cell Death Discov.

8(492)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Wright HL, Lyon M, Chapman EA, Moots RJ

and Edwards SW: Rheumatoid arthritis synovial fluid neutrophils

drive inflammation through production of chemokines, reactive

oxygen species, and neutrophil extracellular traps. Front Immunol.

11(584116)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Wu B, Ni H, Li J, Zhuang X, Zhang J, Qi Z,

Chen Q, Wen Z, Shi H, Luo X and Jin B: The impact of circulating

mitochondrial DNA on cardiomyocyte apoptosis and myocardial injury

after TLR4 activation in experimental autoimmune myocarditis. Cell

Physiol Biochem. 42:713–728. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Mukherjee S, Patra R, Behzadi P, Masotti

A, Paolini A and Sarshar M: Toll-like receptor-guided therapeutic

intervention of human cancers: Molecular and immunological

perspectives. Front Immunol. 14(1244345)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Chávez MD and Tse HM: Targeting

mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species in T cell-mediated

autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 12(703972)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Masoumi M, Alesaeidi S, Khorramdelazad H,

Behzadi M, Baharlou R, Alizadeh-Fanalou S and Karami J: Role of T

cells in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis: Focus on

immunometabolism dysfunctions. Inflammation. 46:88–102.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Weyand CM, Wu B, Huang T, Hu Z and Goronzy

JJ: Mitochondria as disease-relevant organelles in rheumatoid

arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 211:208–223. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Jing W, Liu C, Su C, Liu L, Chen P, Li X,

Zhang X, Yuan B, Wang H and Du X: Role of reactive oxygen species

and mitochondrial damage in rheumatoid arthritis and targeted

drugs. Front Immunol. 14(1107670)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Michalak KP and Michalak AZ: Understanding

chronic inflammation: couplings between cytokines, ROS, NO, Cai2+,

HIF-1α, Nrf2 and autophagy. Front Immunol.

16(1558263)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Sung JY, Kim SG, Park SY, Kim JR and Choi

HC: Telomere stabilization by metformin mitigates the progression

of atherosclerosis via the AMPK-dependent p-PGC-1α pathway. Exp Mol

Med. 56:1967–1979. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Zhi ZY and Wang PC: The mitochondrial

targeting drug SkQ1 attenuates the progression of post-traumatic

osteoarthritis through suppression of mitochondrial oxidative

stress. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 17(e18761429383749)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Xiong Z, Liao Y, Zhang Z, Wan Z, Liang S

and Guo J: Molecular insights into oxidative-stress-mediated

cardiomyopathy and potential therapeutic strategies. Biomolecules.

15(670)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Wu J, Xu J, Zhang M, Zhong J, Gao W and Wu

M: Chondrocyte mitochondrial quality control: A novel insight into

osteoarthritis and cartilage regeneration. Adv Wound Care (New

Rochelle): Apr 18, 2025 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

82

|

Wang Z, Yin F, Xu J, Zhang T, Wang G, Mao

M, Wang Z, Sun W, Han J, Yang M, et al: CYT997(Lexibulin) induces

apoptosis and autophagy through the activation of mutually

reinforced ER stress and ROS in osteosarcoma. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 38(44)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Saberi M, Zhang X and Mobasheri A:

Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction with small molecules in

intervertebral disc aging and degeneration. Geroscience.

43:517–537. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

McCully JD, Levitsky S, del Nido PJ and

Cowan DB: Mitochondrial transplantation for therapeutic use. Clin

Trans Med. 5(e16)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Luo H, Lai Y, Tang W, Wang G, Shen J and

Liu H: Mitochondrial transplantation: A promising strategy for

treating degenerative joint diseases. J Transl Med.

22(941)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Lee AR, Woo JS, Lee SY, Na HS, Cho KH, Lee

YS, Lee JS, Kim SA, Park SH, Kim SJ and Cho ML: Mitochondrial

transplantation ameliorates the development and progression of

osteoarthritis. Immune Netw. 22(e14)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Zhong G, Madry H and Cucchiarini M:

Mitochondrial genome editing to treat human osteoarthritis-A

narrative review. Int J Mol Sci. 23(1467)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Yang X, Jiang J, Li Z, Liang J and Xiang

Y: Strategies for mitochondrial gene editing. Comput Struct

Biotechnol J. 19:3319–3329. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|