Introduction

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are synthetic

chlorinated compounds that were historically used in a numerous

industrial and commercial applications due to their chemical

stability, and insulating properties. Although the manufacture and

use of PCBs have been banned or severely restricted in many

countries, PCBs persist in the environment and continue to raise

significant public health concerns due to their bioaccumulative

nature and long biological half-life (1,2). Human

exposure occurs primarily through the consumption of contaminated

food, particularly animal fats, as well as through inhalation and

dermal contact (1,3). Among the various PCB congeners, PCB153

is one of the most abundant and persistent in human tissues

(2). Its strong lipophilicity and

resistance to metabolic degradation facilitate its accumulation in

the food chain, especially in lipid-rich food sources such as fish

and animal meat (4). The intestinal

epithelium, as the first site of dietary exposure and absorption,

represents a critical yet understudied target for PCB153

toxicity.

The intestinal epithelium plays a central role in

maintaining mucosal homeostasis, acting as both a physical barrier

and an active regulator of immune and metabolic processes.

Disruption of intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) function by

environmental toxicants has been linked to impaired barrier

integrity, chronic inflammation, metabolic dysregulation (5,6).

Previous studies have begun to elucidate the impact of PCB153 on

gut health. For example, Choi et al (7) demonstrated that PCBs disrupt

intestinal barrier function by inducing oxidative stress via NADPH

oxidase activation, which alters tight junction protein expression

and compromises epithelial integrity. Additionally, Phillips et

al (8) reported that intestinal

exposure to PCB153 activates the ATM/NEMO pathway, triggering

inflammation and epithelial injury. Together, these findings raise

important concerns about the impact of PCB153 on intestinal

homeostasis and underscore the need for deeper mechanistic studies

into how environmental toxicants drive intestinal dysfunction.

Significant knowledge gaps remain regarding the

broader transcriptional and cellular consequences of PCB153

exposure in normal human IECs. Prior studies have relied on colon

cancer cell lines or murine exposure models (7,8), while

may not accurately reflect the normal epithelial physiology.

To bridge these gaps, we utilized the

non-tumorigenic human IEC line NCM460D (9) to evaluate the dose-dependent effects

of PCB153 exposure on the profiling of whole transcriptome of IECs.

By integrating viability assays with RNA sequencing, we

systematically characterized how low and high concentrations of

PCB153 alter transcriptional programs and key biological pathways.

Our data reveal broad transcriptomic shifts involving inflammation,

cellular stress, metabolic disruption, impaired regenerative

signaling, and altered gut-brain communication. Notably, we found

the suppression of Wnt signaling and proliferation-associated

genes, suggesting mechanistic insights into how PCB153 compromises

epithelial renewal and barrier maintenance.

This study presents the first comprehensive,

dose-dependent transcriptomic analysis of PCB153 exposure in normal

human IECs, offering new perspectives on the molecular mechanisms

through which PCB153 compromises intestinal health.

Materials and methods

In vitro experiments

NCM460D cell line was purchased from INCELL

Corporation (San Antonio, TX). NCM460D is a non-transformed human

colonic epithelial cell line originally derived from normal colon

tissue of a 68-year-old male donor. The cells were selected for

stable in vitro growth and were not infected, immortalized,

or genetically modified, preserving a normal genotype.

Phenotypically, NCM460D cells express key intestinal epithelial

markers, including cytokeratins, villin, colonic epithelial

antigens, and a subset of cells exhibit mucin production,

consistent with differentiated epithelial features (9). NCM460D cells are non-tumorigenic and

grown in INCELL's enriched M3:10™ medium (INCELL Corp.)

to maintain their physiological phenotype, supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA),

100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Gibco), at 37˚C in

a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

PCB153 (2,2',4,4',5,5'-hexachlorobiphenyl) was

purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and dissolved in

dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to generate a 10 mM stock solution.

Working concentrations were freshly prepared by diluting the stock

in M3:10™ complete medium, ensuring the final DMSO

concentration did not exceed 0.1% (v/v) in any treatment. Cells

were seeded at 2x104 cells/well in 96-well plates for

viability assays or 2x105 cells/well in 6-well plates

for RNA extraction. For the cell viability assay, cells were

treated with 0.5, 5, 50, or 200 µM PCB153, or an equivalent volume

of DMSO (vehicle control), for 6, 24, or 48 h. For transcriptomic

analysis and RT-qPCR validation, cells were exposed to PCB153 (0,

5, or 50 µM) or DMSO for 24 h under identical culture conditions in

a 37˚C humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

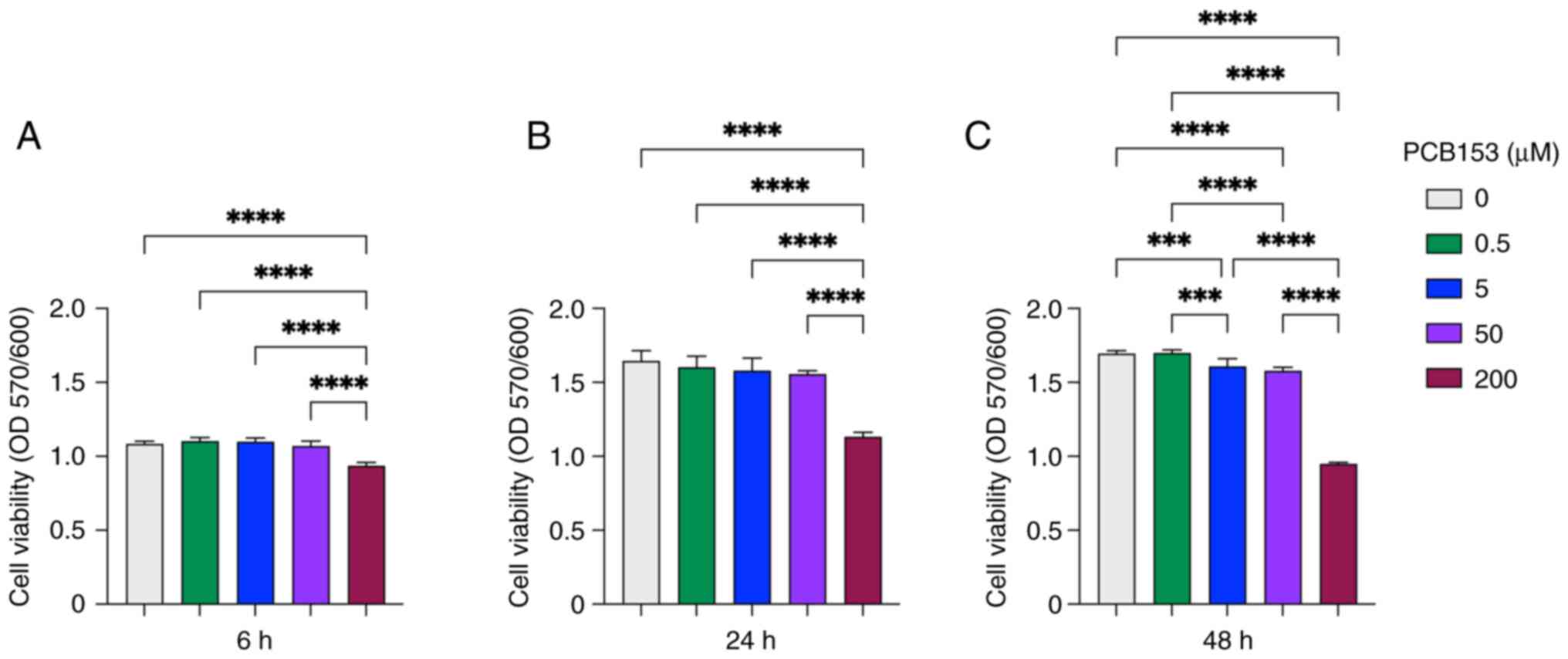

Cell viability assay

The genotoxicity of PCB153 on intestinal epithelial

cells was determined by PrestoBlueTM HS Reagent

(Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Briefly,

NCM460D cells (2x104 cells/well) were seeded into a

96-well plate and treated with PCB153 at final concentrations of 0,

0.5, 5, 50 and 200 µM, with DMSO serving as the vehicle control.

Treatments were performed for 6, 24, and 48 h. After treatment,

PrestoBlue reagent was added directly to the culture medium as

1/10th of the total well volume and incubated for 1 h in a cell

culture incubator at 37˚C, protected from direct light. Absorbance

was measured at 570 nm, using 600 nm as a reference wavelength.

Cell viability was calculated as the ratio of OD570/600.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

NCM460D cells (2 x 105 cells/well in

6-well plate) were treated with PCB153 (0, 5, or 50 µM) for 24 h,

with DMSO serving as the vehicle control. Total RNA was extracted

from the cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufactory protocol. RNA

purity and concentration were assessed using the NanoDrop

spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Total 1

µg of RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using high-capacity cDNA

reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Waltham, MA). Reverse transcription was performed at

25˚C for 10 min, followed by 37˚C for 120 min, 85˚C for 5 min, and

then held at 4˚C. Quantitative PCR was performed with SYBR Green

master mix (Applied Biosystems) on a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR

System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The thermocycling program

consisted of an initial denaturation at 95˚C for 10 min, followed

by 40 cycles of 95˚C for 15 sec and 60˚C for 60 sec. The relative

expression of target gene was analyzed by the

2-ΔΔCq method (10), normalizing each target to

GAPDH and expressing data as fold-change relative to the

solvent control. Primer sequences of MT1G, MT2A,

LGR5, DACT1, LEF1 and GAPDH are

provided in Table SI.

RNA sequencing

NCM460D cells (2x105 cells/well in 6-well

plate) were treated with PCB153 (5, or 50 µM) for 24 h, with DMSO

serving as the vehicle control. Total RNA was extracted from the

cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Waltham, MA) as previously described and purified by RNA Clean

& Concentrator kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) according to the

manufactory protocol. RNA integrity and quantity were further

assessed using Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa

Clara, CA) before the library construction for RNA sequencing.

Total RNA was processed for Poly(A) mRNA isolation and preparation

of cDNA libraries using NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit (New

England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and barcoded with NEBNext Multiplex

Oligos for Illumina (NEB), all according to the manufacturer's

manuals. Library concentration was measured by Agilent Bioanalyzer

(Agilent Technologies) and 2.6x10-10 moles desired

loading of final library were subjected to 100 bp pair-end

sequenced (PE100) on the Illumina NovaSeqX platform at the

University of Chicago Genomics Core Facility (Chicago, IL). RNA-Seq

raw data has been uploaded to the database at the National Center

for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/) under

BioProject accession number PRJNA1285092.

RNA sequencing data analysis

For transcriptomic analysis, we performed two

independent biological experiments, each containing duplicate

cultures per treatment condition (0, 5, and 50 µM PCB153). To

minimize technical variation and maximize consistency across

experiments, the duplicate cultures within each treatment group

were pooled prior to RNA extraction, resulting in two biological

replicates per treatment group used for RNA-seq. The output FASTQ

sequences were aligned to reference human genome annotation

(GENCODE version 48) using STAR software (version 2.7) (11). The aligned sequences were further

sorted with Samtools (version 1.18) (12). Counting reads in features with

htseq-count (version 2.0.2) (13).

The count matrix was then normalized and differentially expressed

were identified (adjusted P-value <0.05) with the DESeq2 package

(version 1.46) (14) in R software

(version 4.4). Gene Ontology (GO) was identified by clusterProfiler

(version 4.14) (15) to discover

the functional enrichment of pathways comparing experimental

groups. ShinyGO 0.82 was used to visualize the pathway networks

(16).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using

GraphPad Prism (version 10.5). For cell viability assays (n=6) and

RT-qPCR (n=3) experiments, differences among treatment groups were

analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test for

multiple comparisons. Data are presented as mean ± standard

deviation (SD). A P-value of P<0.05 was considered statistically

significant. Significance levels are indicated as

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001.

Results

Establishing RNA-seq compatible PCB153

exposure conditions

To evaluate the cellular consequences of PCB153

exposure in a physiologically relevant intestinal model, we first

established an in vitro system using the non-tumorigenic

human intestinal epithelial cell line NCM460D. This line is derived

from normal colonic mucosa and retains key features of

differentiated intestinal epithelial cells, including expression of

cytokeratins, villin, and other colonic epithelial markers, without

exogenous genetic modifications (9). Due to these characteristics, NCM460D

cells provide an appropriate model for examining transcriptomic

disruptions in normal IECs.

To determine suitable exposure conditions for

transcriptomic profiling, we next assessed the effects of PCB153 on

NCM460D cell viability across a range of concentrations (0.5, 5,

50, and 200 µM) and exposure times (6, 24, and 48 h) (Fig. 1). This analysis was conducted to

identify non-cytotoxic conditions appropriate for detection of

meaningful alterations by RNA-seq, rather than to define a full

cytotoxicity curve. At 6 h, cells exposed to 0.5-50 µM PCB153

showed little change in viability, indicating that this short

exposure primarily captures immediate early-response genes and is

not ideal for broader transcriptional profiling (Fig. 1A). In contrast, 200 µM PCB153 caused

acute viability loss at this early time point, making it unsuitable

for mechanistic studies (Fig. 1A).

Cells were maintained >90% viability when exposed with both 5

and 50 µM PCB153 at 24 h, providing sufficient time for primary

transcriptomic responses to develop while avoiding overt

cytotoxicity (Fig. 1B). By

comparison, 0.5 µM PCB153 produced minimal biological impact on

NCM460D cells and was unlikely to yield detectable transcriptional

changes (Fig. 1A-C). However,

subtle but statistically significant reductions in cell viability

emerged at 48 h, even at 5 and 50 µM intermediate doses, indicating

that longer exposures may introduce nonspecific cytotoxic effects

(Fig. 1C). Together, these findings

identify 5 and 50 µM PCB153 for 24 h as optimal exposure conditions

that balance IEC cellular integrity with meaningful transcriptional

alterations while minimizing confounding cytotoxic effects and thus

were selected for subsequent RNA-seq experiments.

Transcriptome changes in IECs exposed

to PCB153

Although recent studies have identified various

adverse effects of PCB153 exposure, significant knowledge gaps

remain regarding its impact and underlying mechanisms of

cytotoxicity in normal intestinal epithelial cells. In addition, no

studies have systematically investigated the dose-dependent effects

of PCB153 exposure on normal IECs. To address these gaps, this

study aimed to characterize the transcriptional responses and

signaling pathways affected by PCB153 in human normal IECs using

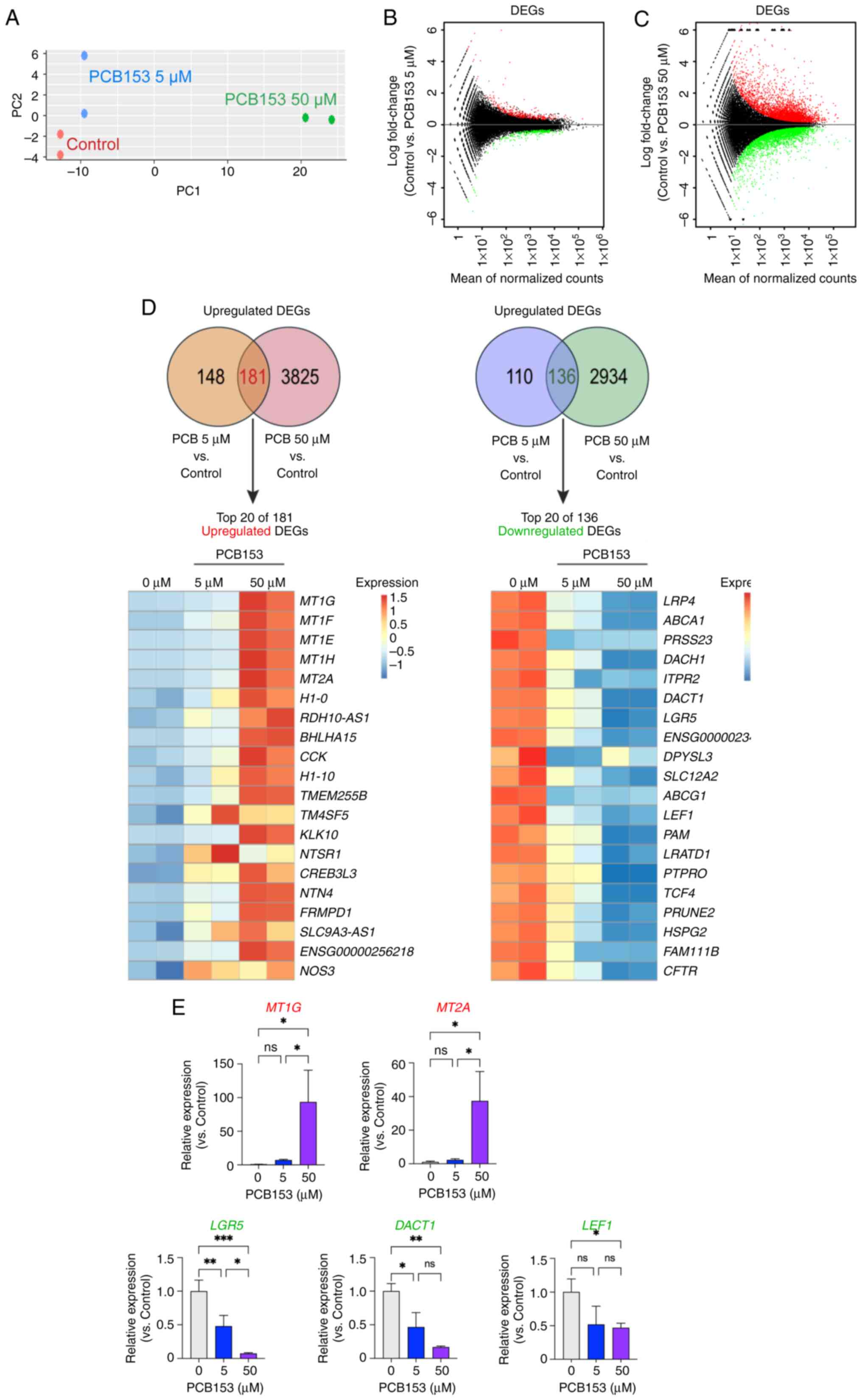

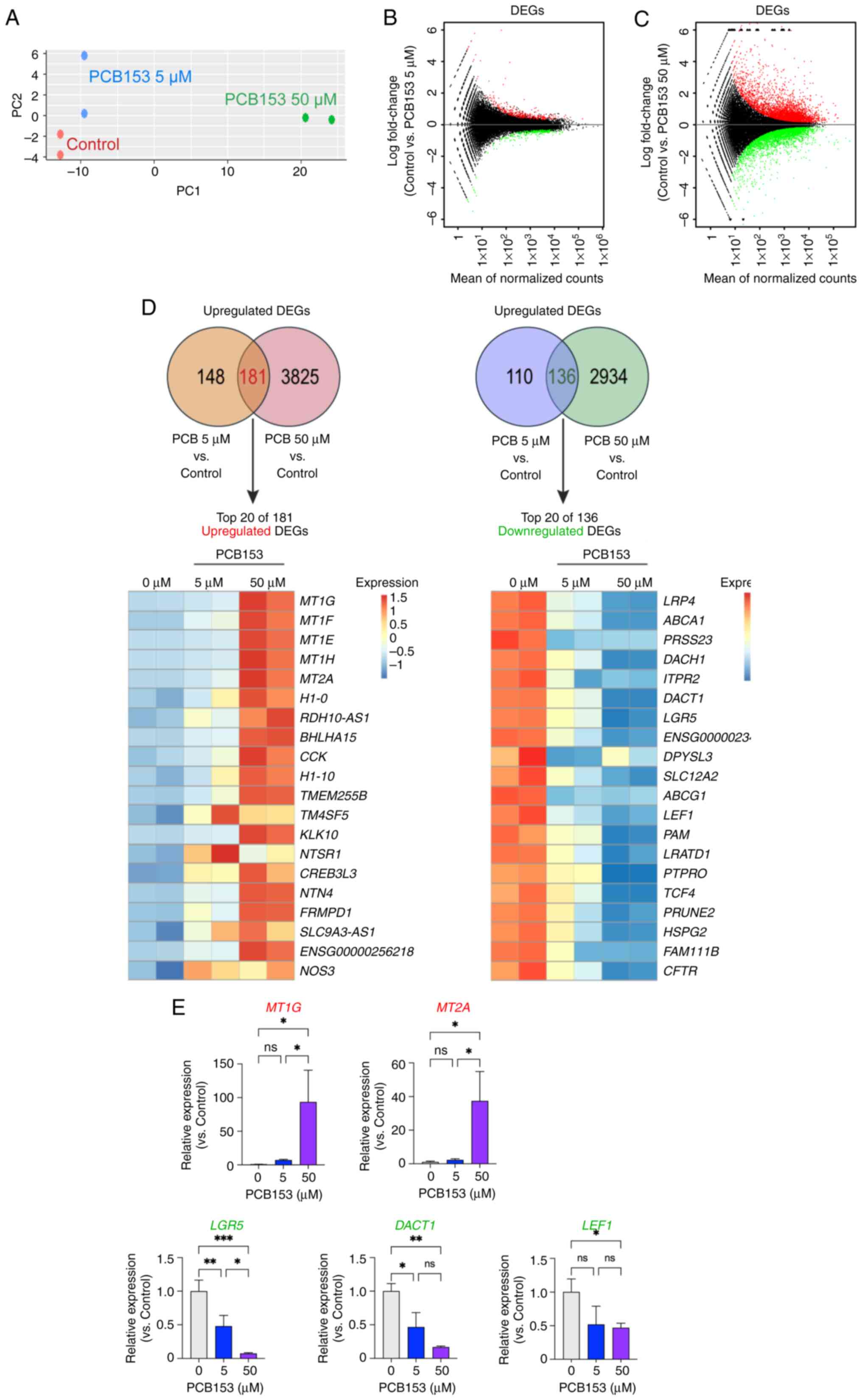

RNA-seq analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed a

significant transcriptomic shift between control and PCB153-treated

cells. More importantly, the transcriptomic changes followed a

dose-dependent pattern in IECs exposed to PCB153 (Fig. 2A). Further analysis of

differentially expressed genes (DEGs), using an adjusted P-value

cutoff of <0.05, identified 329 upregulated and 246

downregulated genes in IECs treated with 5 µM of PCB153 compared to

controls (Fig. 2B). Moreover,

exposure to 50 µM of PCB153 resulted in 4,006 upregulated and 3,070

downregulated genes (Fig. 2C).

Among these significantly differentially expressed genes, 136 were

commonly downregulated, and 181 were commonly upregulated in both

the 5 and 50 µM PCB153 treatment groups compared to controls

(Fig. 2D). These results suggest

that acute PCB153 exposure significantly alters the transcriptome

of IECs, with higher doses exerting more pronounced effects than

lower doses. The higher PCB153 exposure resulted in thousands of

gene expression changes, indicating a dose-dependent impact on the

IEC transcriptome. To validate the RNA-seq results, RT-qPCR was

performed for several representative differentially expressed

genes, including MT1G, MT2A, LGR5,

DACT1, and LEF1. The RT-qPCR results confirmed a

strong induction of MT1G and MT2A, and a marked

suppression of LGR5, DACT1, and LEF1 following

PCB153 exposure, consistent with the RNA-seq data (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these findings

suggest that PCB153 exposure may profoundly influence IEC cellular

functions and biological processes.

| Figure 2Dose-dependent transcriptomic

alterations in human IECs following PCB153 exposure. (A) PC

analysis of RNA-seq data showing distinct clustering of control and

PCB153-treated IECs, with a clear dose-dependent separation between

the 5 and 50 µM exposure groups. (B) MA plot of DEGs in IECs

treated with 5 µM PCB153 compared with the control group,

highlighting 329 upregulated and 246 downregulated genes (adjusted

P<0.05). (C) MA plot of DEGs in IECs treated with 50 µM PCB153

compared with the control group, showing 4,006 upregulated and

3,070 downregulated genes (adjusted P<0.05). (D) Venn diagram

illustrating the overlap of DEGs between the 5 and 50 µM PCB153

treatment groups, identifying 181 commonly upregulated and 136

commonly downregulated genes, with the top 20 DEGs (ranked by

P-value) visualized in a heatmap. RNA-seq data from two independent

biological experiments, each performed in duplicate are presented.

(E) Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR validation of selected

representative DEGs (MT1G, MT2A, LGR5,

DACT1 and LEF1) confirming induction of

metallothionein genes and suppression of Wnt-related targets,

consistent with RNA-seq results. n=3 for each group. Statistical

significance was determined using one-way ANOVA.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. DEG, differentially expressed gene; IEC,

intestinal epithelial cell; ns, not significant; PC, principal

component; PCB153, polychlorinated biphenyl 153; RNA-seq, RNA

sequencing; MA plot, minus-average plot. |

PCB153 exposure leads to intestinal

epithelial cell dysfunction, metabolic disruption, and tumorigenic

potential

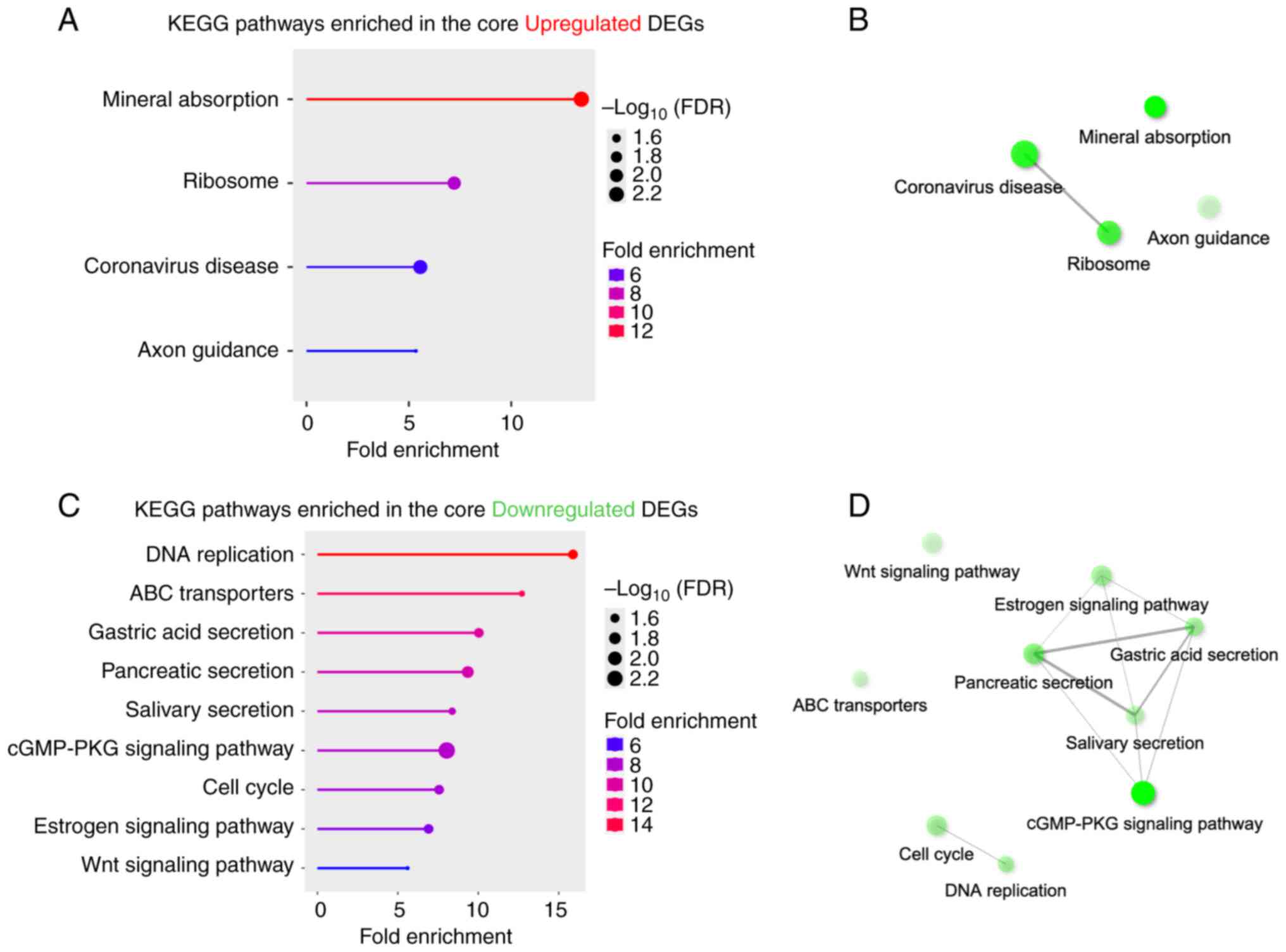

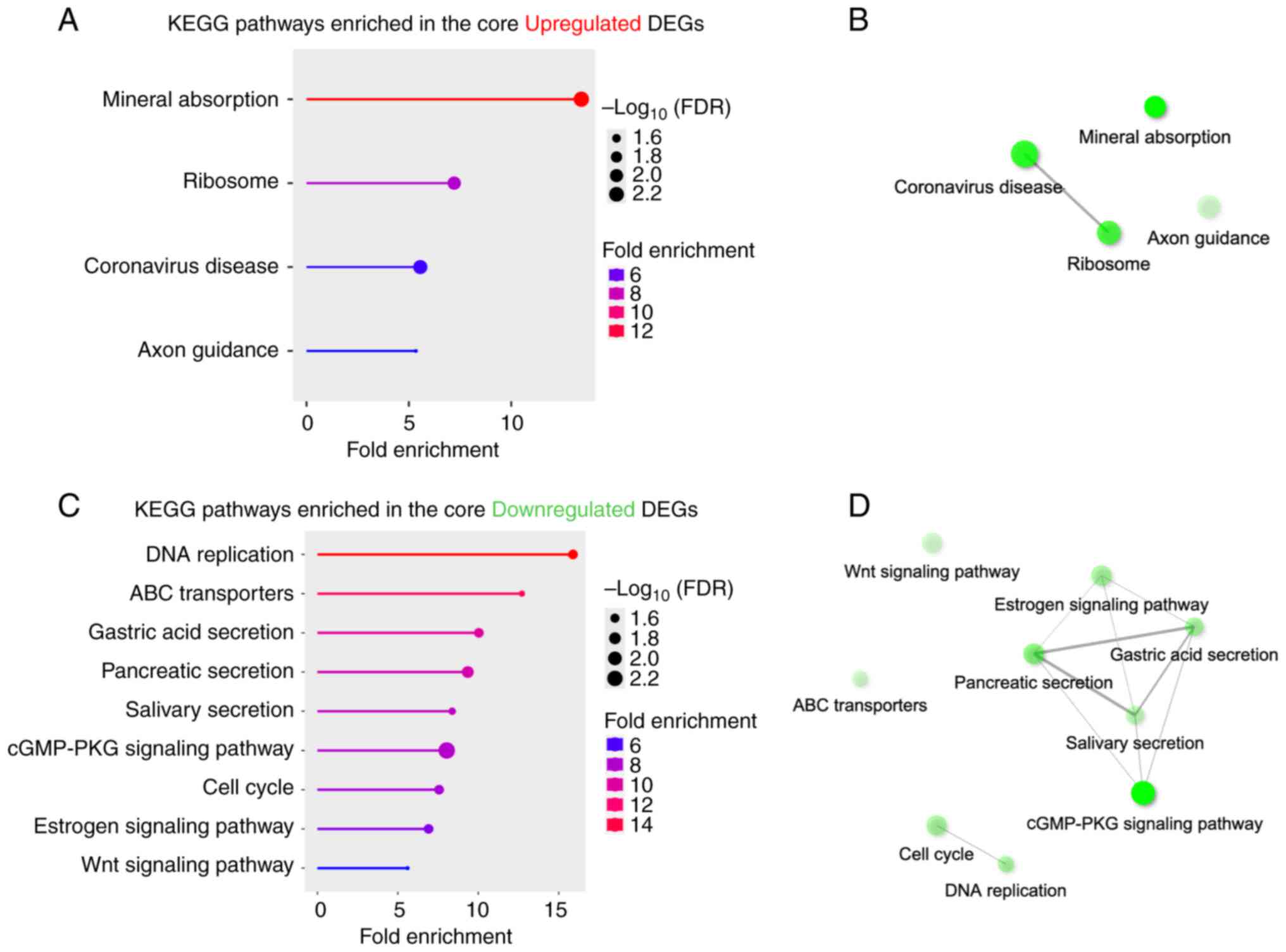

Through DEG analysis, we identified a core set of

317 genes (136 downregulated and 181 upregulated) shared between

two doses of PCB153 exposure. Pathway analysis of this core set

revealed significant alterations in several key biological

processes. GO terms analysis of the 181 upregulated genes indicated

significant enrichment in pathways related to mineral absorption,

ribosome function, coronavirus disease, and axon guidance (Fig. 3A and B). The upregulation of mineral absorption

pathways suggests that PCB153 disrupts metal homeostasis,

particularly affecting zinc (Zn) and copper (Cu) transport.

Metallothionein (MT) family genes (MT1E, MT1F,

MT1G and MT2A), regulate essential metal ions

(17,18), dramatically induced, suggesting an

adaptive response to PCB153-induced metal transporter disruption,

potentially leading to increased cellular stress due to metal

accumulation or dysregulation of Zn/Cu levels. Additionally, the

increased ribosome activity observed following PCB153 exposure

suggests enhanced protein synthesis, which may burden cellular

machinery, triggering ER stress, misfolded proteins, and conditions

favoring tumorigenesis (19,20).

The upregulation of coronavirus disease pathway (Path:hsa05171,

aggregates 232 pathway genes) likely reflects the activation of a

general ‘viral response-related pathways’ or inflammatory stress

response, suggesting PCB153 exposure alters immune responses in the

IECs, potentially increasing susceptibility to viral infections and

chronic inflammation. Taken together, network analysis further

revealed a potential connection between ribosome and coronavirus

disease pathways in response to PCB153, suggesting that ribosome

dysregulation may exacerbate gut inflammation during infections

(Fig. 3B). Interestingly, PCB153

exposure also disrupted axon guidance signaling, suggesting

potential alterations in gut-brain axis communication. Axon

guidance genes, such as NTN4 [a member of the netrin family

(21)], regulate neuronal

connectivity, and their dysregulation may impair gut-brain

signaling, potentially affecting gut motility and neurological

function.

| Figure 3Pathway enrichment analysis of

commonly dysregulated genes in IECs following PCB153 exposure. (A)

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of 181 commonly upregulated genes

revealed significant enrichment in pathways related to ‘mineral

absorption’, ‘ribosome’, ‘coronavirus disease’ and ‘axon guidance’.

(B) Network analysis of upregulated pathways highlighted potential

interactions between ‘ribosome’ and viral response-related pathways

(‘coronavirus disease’). (C) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of

136 commonly downregulated genes identified significant suppression

of pathways involved in ‘DNA replication’, ‘ABC transporters’,

digestive secretions (‘gastric acid secretion’, ‘pancreatic

secretion’ and ‘salivary secretion’), ‘cGMP-PKG signaling’, ‘cell

cycle’, ‘estrogen signaling’ and ‘Wnt signaling’. (D) Network

analysis of downregulated pathways showed interconnected

suppression of digestive secretion pathways and the ‘cGMP-PKG

signaling pathway’, indicating impaired intestinal epithelial

physiology. (B and D) Interactive plot shows the relationship

between enriched pathways. Two pathways (nodes) are connected if

they share ≥20% of genes. Darker nodes are more significantly

enriched gene sets. Bigger nodes represent larger gene sets.

Thicker edges represent more overlapped genes. DEG, differentially

expressed gene; FDR, false discovery rate; IEC, intestinal

epithelial cell; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes;

PCB153, polychlorinated biphenyl 153. |

On the other hand, PCB153 exposure led to the

downregulation of 136 core genes, which were significantly enriched

in pathways related to DNA replication, ABC transporters, digestive

secretions (gastric acid, pancreatic, and salivary), cGMP-PKG

signaling, cell cycle, estrogen signaling, and Wnt signaling

(Fig. 3C and D). Among these, the suppression of DNA

replication and cell cycle genes suggests reduced IEC

proliferation. Network analysis highlighted a core connection

between gastric acid secretion, pancreatic secretion, and salivary

secretion, indicating that PCB153 may significantly disrupt

digestive processes (Fig. 3D). The

downregulation of these pathways may impair protein, fat, and

carbohydrate digestion, leading to malabsorption disorders

(22). Furthermore, the cGMP-PKG

signaling pathway is also connected to the digestive secretion

function, which plays a role in intestinal motility and cellular

homeostasis (23,24), was also downregulated (Fig. 3C and D). The suppression of ABC transporters

(e.g., ABCA1, ABCG1) impairs cholesterol efflux,

leading to lipid accumulation and oxidative stress (25). Similarly, downregulation of estrogen

signaling in IECs may contribute to the disruptions in intestinal

lipid homeostasis. Since PCBs are lipophilic and accumulate in

lipid membranes, the inhibition of ABC transporters may increase

intracellular PCB retention, exacerbating cellular toxicity and

bioaccumulation. Most importantly, PCB153 exposure significantly

disrupted the Wnt signaling pathway, which is critical for

intestinal stem cell renewal and epithelial integrity (26,27)

(Fig. 3C). Notably, due to the

downregulation of WNT signaling, LGR5, a stemness-associated

molecule, was significantly downregulated (Fig. 2D), suggesting impaired intestinal

regeneration and homeostasis. Additionally, TCF4 and

LEF1, two major Wnt transcription factors essential for IEC

proliferation, ranked among the top 20 downregulated genes

(Fig. 2D). Their suppression

directly contributes the disrupts of WNT signaling linking to IECs

renewal and regeneration, highlighting the detrimental impact of

PCB153 on intestinal epithelial integrity.

Taken together, PCB153 exposure profoundly alters

multiple essential signaling pathways in normal IECs, disrupting

cell proliferation, lipid metabolism, immune responses, and

gut-brain axis communication. These findings suggest that PCB153

exposure not only impairs gut homeostasis but may also contribute

to tumorigenic potential and long-term metabolic dysfunction.

IECs displays a dose-dependent

toxicant response to PCB153 exposure

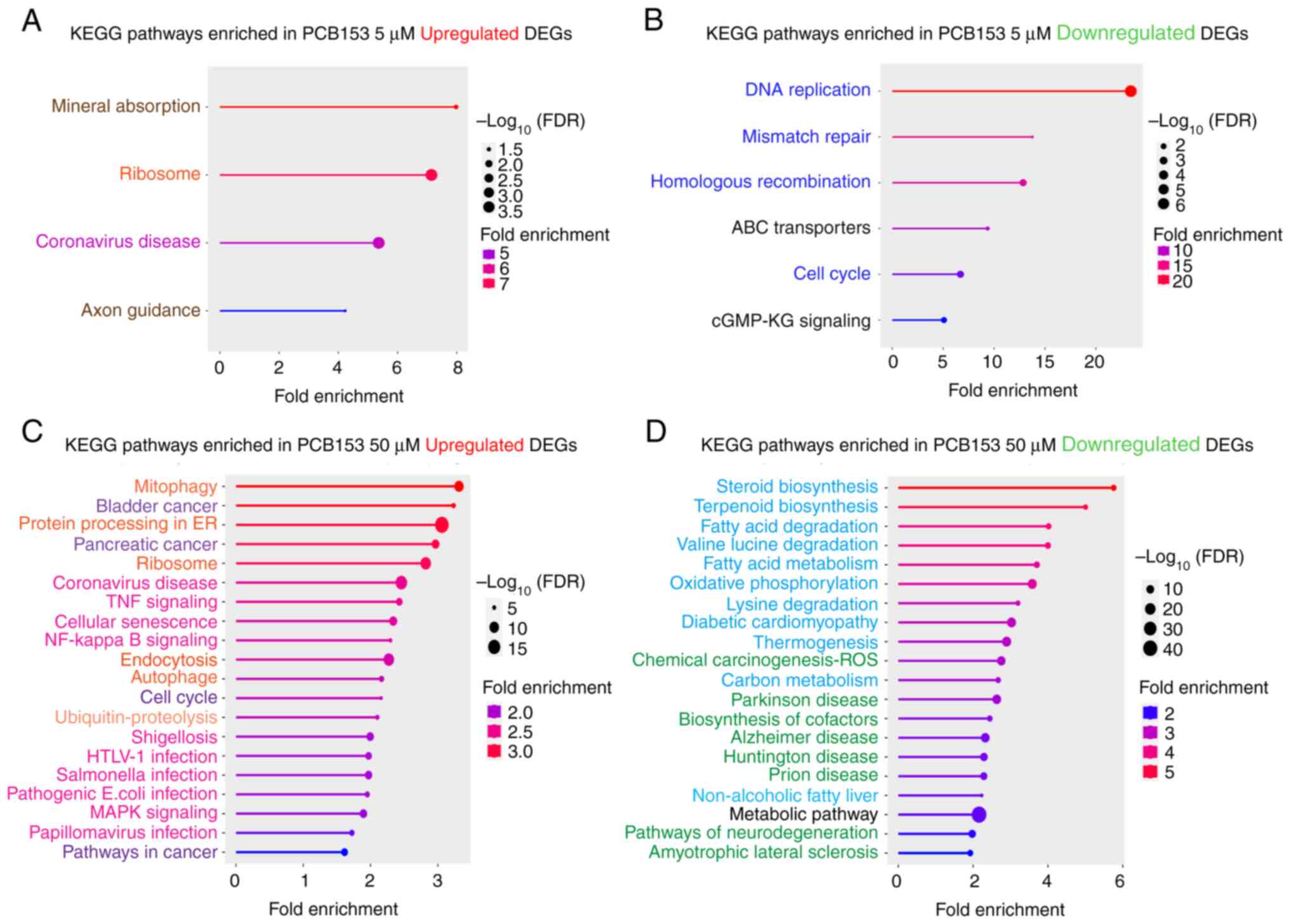

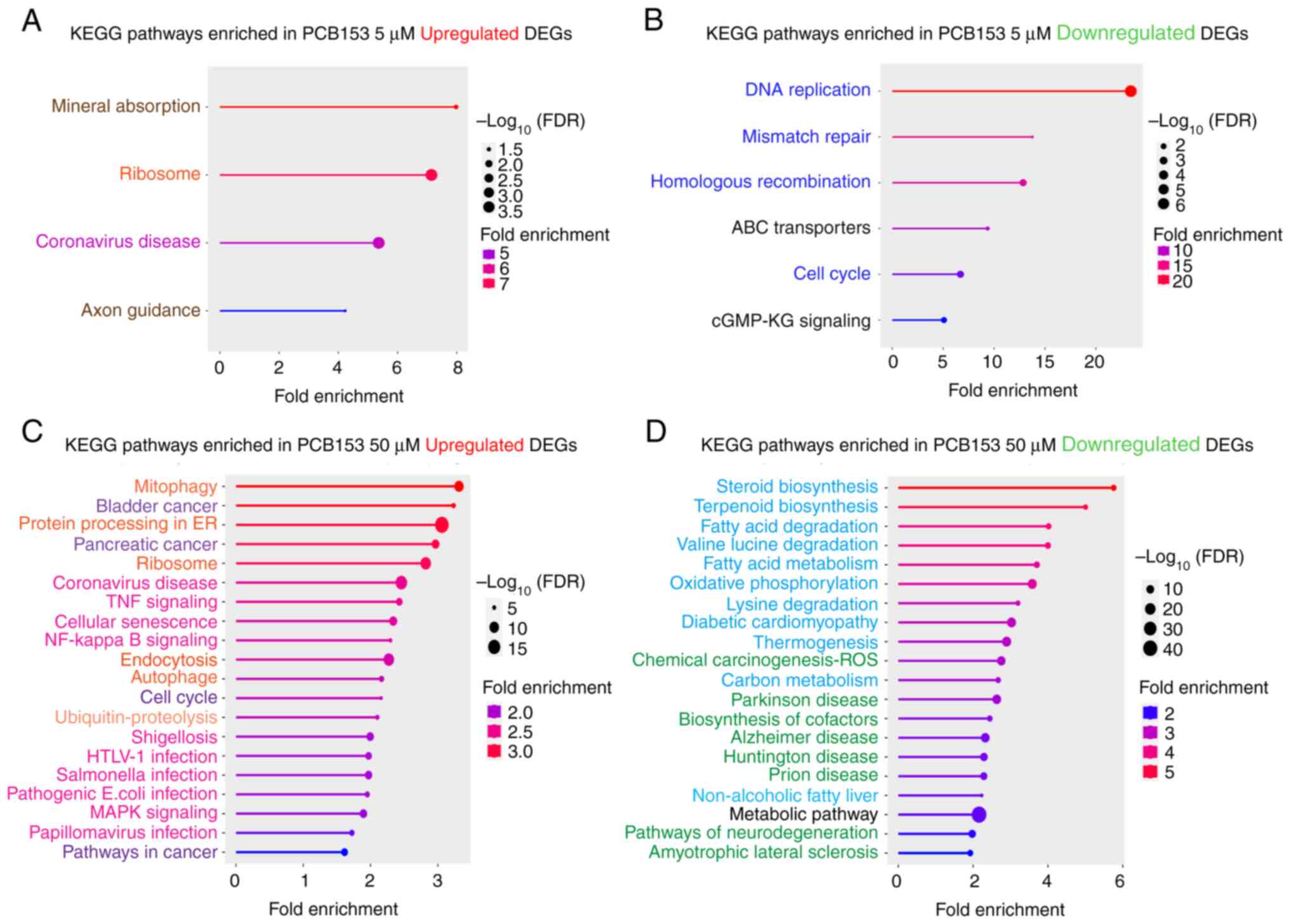

In this study, we further evaluated the

dose-dependent effects of PCB153 on cell fate and signaling in

IECs. We found that the 5 µM of PCB153 exposure resulted in the

upregulation of the same cellular pathways as identified with the

common core upregulated gene set, suggesting the lower dose of

PCB153 exposure can initiate the cellular changes of mineral

absorption, ribosome function, coronavirus disease, and axon

guidance (Fig. 4A). We found that

relatively low PCB153 exposure in IECs led to the downregulation in

DNA replication, mismatch repair, homologous recombination, ABC

transporters, cell cycle regulation, and cGMP-PKG signaling,

effects that would be predicted to result in severe gut dysfunction

(Fig. 4B). Impaired DNA repair and

cell cycle arrest increase genomic instability, raising the risk of

mutations and colorectal cancer (28,29).

Downregulated ABC transporters reduce toxin efflux, suggesting that

PCB153 exposure could augment further cellular PCB153 retention.

Additionally, weakened intestinal regeneration can impair the

barrier integrity and contribute to chronic inflammation and

disrupted homeostasis. These changes collectively are predicted to

compromise gut health, increasing susceptibility to disease,

oxidative stress, and metabolic imbalances.

| Figure 4Dose-dependent pathway alterations in

IECs following PCB153 exposure. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of

(A) upregulated genes and (B) downregulated genes in IECs treated

with 5 µM PCB compared with the control group. (C and D) The top 20

enriched pathways in IECs treated with 50 µM PCB153 were ranked by

fold enrichment and reorganized into functional modules (indicated

by the font color) to improve clarity and interpretability. (A-D)

Upregulated pathways were grouped into ‘Immune & Host-Defense’

(magenta), ‘Proteostasis & Translation’ (orange),

‘Proliferation/Oncogenic’ (violet) and ‘Others’ (brown) categories,

whereas downregulated pathways were grouped into ‘Core Energy &

Lipid Metabolism’ (light blue), ‘Genome Maintenance &

Proliferation’ (dark blue), ‘Neurodegeneration & Proteostasis

Stress’ (green) and ‘Transport/Signaling & Global’ (black)

categories. The significance of pathway enrichment is shown as

-log10(FDR), with higher values indicating stronger

statistical enrichment. DEG, differentially expressed gene; FDR,

false discovery rate; IEC, intestinal epithelial cell; KEGG, Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; PCB153, polychlorinated biphenyl

153. |

On the other hand, 50 µM of PCB153 exposure in IECs

resulted in dramatical impairments of multiple signaling pathways.

Using an FDR <0.05 as the significance cutoff, a total of 111

pathways were significantly upregulated and 68 were downregulated.

The top 20 pathways are shown in Fig.

4C and D. To enhance

interpretability, the enriched pathways were consolidated into

functional modules based on shared biological relevance.

Upregulated pathways were grouped into four major categories:

‘Immune & Host-Defense’, ‘Proteostasis & Translation’,

‘Proliferation/Oncogenic’, and ‘Others’. Downregulated pathways

were classified into ‘Core Energy & Lipid Metabolism’, ‘Genome

Maintenance & Proliferation’, ‘Neurodegeneration &

Proteostasis Stress’, and ‘Transport/Signaling & Global’

modules. This modular grouping highlights the extensive remodeling

of immune, metabolic, and stress-related processes in intestinal

epithelial cells following high-dose PCB153 exposure.

To provide deeper biological context, we next

analyzed the pathways driving these functional modules to delineate

the specific cellular processes affected by PCB153 exposure.

Exposure to 50 µM PCB153 in IECs induces significant cellular

stress, inflammation, and cancer-related responses. Upregulation of

mitophagy, autophagy, and protein processing in the ER suggests

heightened stress adaptation mechanisms, while activation of TNF

and NF-kB signaling points to chronic inflammation and immune

dysregulation (30). Increased

expression of cancer-related pathways, including bladder and

pancreatic cancer, as well as cell cycle dysregulation and

senescence, implies a potential pro-tumorigenic environment.

Additionally, pathways linked to bacterial and viral infections

(Shigellosis, Salmonella, E. coli, and

Papillomavirus) are upregulated, suggesting gut barrier

dysfunction and increased pathogen susceptibility (31). Thus, these alterations indicate that

PCB153 compromises intestinal homeostasis, promotes inflammatory

and oncogenic signaling, and weakens immune defenses, increasing

the risk of gut-related diseases and malignancies. Conversely, we

found that exposure to 50 µM of PCB153 in IECs intensively

downregulates key metabolic, mitochondrial, and detoxification

pathways, effects likely leading to impaired cellular function.

Suppression of steroid and terpenoid biosynthesis, fatty acid

metabolism, and amino acid degradation (valine, leucine, lysine)

suggests disrupted lipid and energy homeostasis, which may

contribute to metabolic disorders. Downregulation of oxidative

phosphorylation and thermogenesis points to mitochondrial

dysfunction and reduced energy production, potentially compromising

cellular survival (32). Inhibition

of chemical carcinogenesis (ROS detoxification) and carbon

metabolism indicates reduced detoxification capacity, likely

rendering PCB153-exposed cells more vulnerable to oxidative stress

and secondary toxic insults. Furthermore, repression of pathways

related to neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer's, Parkinson's,

Huntington's, and ALS) raises concerns about systemic neurotoxic

effects of PCB153 exposure. Collectively, these alterations suggest

that high dose of PCB153 disrupts cellular metabolism,

mitochondrial function, and detoxification mechanisms, potentially

contributing to epithelial cell dysfunction, metabolic disorders,

and increased disease susceptibility.

Taken together, both concentrations of PCB153

disrupt IEC homeostasis. The exposure to PCB153 exhibits

dose-dependent transcriptomic shifts in IECs. The higher dose of

PCB153 (50 µM) leads to a broader range of cellular effects,

exacerbating cellular stress, metabolic disruption, and

cancer-related signaling compared to lower doses (5 µM). These

findings highlight the potential role of PCB153 in promoting

epithelial cell dysfunction, immune dysregulation, and disease

susceptibility.

Discussion

This study provides new insights into the cellular

and transcriptomic responses of normal human intestinal epithelial

cells to PCB153 exposure, advancing our understanding of how

environmental toxicants disrupt intestinal epithelial cell

homeostasis. Our data demonstrate that PCB153 exposure leads to

broad transcriptional reprogramming that impacts key biological

pathways related to epithelial renewal, detoxification, metabolism,

immune regulation, and gut homeostasis.

The non-tumorigenic NCM460D cells express key

intestinal epithelial markers with differentiated epithelial

features, which is widely regarded as a physiologically relevant

model for studying normal intestinal epithelial cell biology,

though not a model of intestinal stem cells. Therefore, the

reductions in stemness-associated transcripts (e.g., LGR5)

observed after PCB153 exposure should be interpreted as suppression

of stemness-related gene programs, rather than loss of bona

fide intestinal stem cells. Several pathways altered in this

study align with previously reported mechanisms of PCB-induced

intestinal toxicity. Choi et al (7) demonstrated that PCBs compromise

intestinal barrier integrity by inducing oxidative stress via NADPH

oxidase activation, resulting in altered expression of tight

junction proteins. While our study did not directly assess tight

junction components, we identified the downregulation of genes

involved in cell adhesion and epithelial barrier regulation,

including key metabolic and signaling pathways that support

epithelial integrity, such as cGMP-PKG signaling and Wnt signaling.

The repression of Wnt pathway components (e.g., LEF1, DACT1, and

LGR5) in particular points to impaired epithelial renewal and

homeostatic maintenance, effects predicted to contribute to barrier

dysfunction as reported in Choi's study. Our data support the

hypothesis that PCB153 compromises intestinal barrier function

through multiple molecular mechanisms, including both oxidative

stress and suppression of regenerative signaling. Similarly,

Phillips et al (8)

previously reported that PCB153 activates the ATM/NEMO inflammatory

axis leading to intestinal inflammation in mouse models. In our

transcriptomic analysis, we observed upregulation of immune-related

pathways, including TNF signaling, NF-κB signaling, and genes

associated with viral response and inflammation. These changes

suggest that PCB153 elicits an epithelial inflammatory response,

even in the absence of immune cell stimulation, which may act as a

priming signal for more robust inflammation in vivo. The

upregulation of coronavirus disease-related genes and ribosomal

genes may also reflect a heightened stress and immune surveillance

state, consistent with the immune-activating effects described by

Phillips et al (8). Thus,

our findings in human IECs support and expand upon the

inflammation-related mechanisms impaired by PCB153 exposure.

Importantly, our study also revealed novel

transcriptomic responses to PCB153 exposure, particularly in

pathways related to axon guidance, metallothionein expression, and

lipid metabolism, which have not been widely reported in the

context of intestinal toxicology. These alterations suggest that

PCB153 may affect not only local gut epithelial function but also

broader intercellular communication processes, including gut-brain

signaling and systemic metabolic regulation. In particular,

enrichment of the axon guidance pathway points to potential

modulation of neuro-epithelial communication, as several axon

guidance molecules (e.g., semaphorins, netrins) are increasingly

recognized for their roles in regulating epithelial integrity,

inflammation, and neuronal-immune interactions along the gut-brain

axis (33,34), which represents an intriguing

direction for future research. Metallothioneins, MT1G and MT2A are

regulators of intracellular divalent metal ions, with their highest

binding affinity for zinc (Zn²+) and copper

(Cu+/Cu²+). MT1 and MT2 isoforms also

participate in buffering cadmium (Cd²+), mercury

(Hg²+), and other heavy metals when present. In the

context of intestinal epithelial cells, the PCB-induced

upregulation of MT1G and MT2A most likely reflects

the dysregulation of zinc homeostasis, with potential secondary

effects on copper handling (17,18).

Additionally, the downregulation of ABC transporters and estrogen

signaling pathways points to impaired lipid handling and

detoxification, mechanisms with potential implications for both

epithelial toxicity and systemic exposure burden (25).

In this study, we performed two independent

biological experiments for the RNA-seq transcriptomic profiling.

Although this replicate number is at the lower end of standard

RNA-seq designs, several factors support that it is sufficient for

robust bioinformatic analysis and downstream DEG identification.

First, the two biological replicates showed excellent concordance,

as demonstrated by the tight clustering in the PCA plot (Fig. 2A), which indicates low within-group

variability and strong separation among treatment conditions.

Second, despite the modest replicate number, the RNA-seq dataset

yielded the coherent sets of differentially expressed genes and

enriched pathways, including metallothionein genes, Wnt signaling,

metabolism, and inflammatory pathways. Third, we independently

validated several representative DEGs (MT1G, MT2A,

LGR5, DACT1, LEF1) by RT-qPCR in a separate

experiment with biological triplicates, all of which confirmed the

direction and magnitude of RNA-seq changes.

While the findings of this study significantly

enhance our understanding of PCB153-induced transcriptomic changes

in human IECs, several limitations should be acknowledged. The aim

of the cell viability assay in our study was not to establish a

full pharmacological dose response relationship for PCB153, but

rather to identify treatment conditions that allow detectable

transcriptomic changes without inducing overt cytotoxicity. We

found the sharp viability decline observed at 200 µM compared with

0-50 µM does not imply a mechanistically meaningful PCB153 dose

response inflection point. Instead, it reflects that 200 µM PCB153

exceeds the cytotoxic threshold for the NCM460D intestinal

epithelial cells. This abrupt reduction may correlate with the

physicochemical properties of PCB153, such as its hydrophobicity

and membrane-associated toxicity. In addition, although the

concentrations used in this study (5 and 50 µM) exceed typical

human serum PCB153 levels reported in epidemiological studies

(approximately 0.01-0.1 µM) (35-38),

these exposures remain relevant for in vitro mechanistic

investigation. PCB153 exhibits strong lipophilicity and binds

extensively to serum proteins, lipids, and culture plastics,

substantially reducing the freely bioavailable fraction in cell

culture systems. Therefore, higher concentrations in cell culture

system are often required to achieve intracellular levels

comparable to chronic low-dose exposures in vivo, but does

not fully reflect the chronic, low-level exposures experienced by

most human populations. Future studies incorporating multiple time

points or repeated lower-dose exposure models will be important for

capturing more physiologically relevant outcomes. Furthermore,

although our results align with previous studies in animal models

and provide new mechanistic insights, the use of a single in

vitro cell culture system inherently limits biological

complexity and does not fully capture the multicellular complexity

of the intestinal environment, including stromal, immune, and

microbial components. In whole organisms, compensatory mechanisms

such as epithelial regeneration and systemic detoxification

processes may partially counterbalance or adapt to such cellular

perturbations, potentially attenuating the magnitude of

transcriptomic changes observed in vitro. Validation in

intestinal organoids or in vivo models will be critical to

determine the functional relevance of the pathways identified here.

In addition, while RNA-sequencing offers a powerful tool for global

transcriptomic profiling, it is limited to changes at the mRNA

level. Because transcriptional responses do not always correlate

with protein expression or cellular function, additional validation

is warranted. Future work will focus on confirming major

differentially expressed genes at the protein level, assessing key

signaling activity (i.e. Wnt/cGMP-PKG) and performing functional

assays such as transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER),

oxidative stress measurements, and inflammatory cytokine release,

to determine whether the observed molecular changes translate into

physiological effects and strengthen the mechanistic interpretation

of the RNA-seq findings. These future directions will allow us to

build upon the transcriptomic signatures identified in this study

and more fully delineate the molecular consequences of PCB153

exposure in the intestinal epithelium. Nevertheless, the findings

from this study have important implications for populations exposed

to PCB153 through dietary or environmental sources. By uncovering

specific gene networks and signaling pathways disrupted by PCB153

in normal intestinal epithelial cells, this research offers a

molecular framework that may aid in the development of early

biomarkers for exposure-related gut dysfunction. Pathways such as

Wnt signaling, ABC transporter activity, and metallothionein

regulation could serve as candidate targets for monitoring

epithelial health or assessing individual susceptibility to

PCB-related toxicity. Furthermore, understanding how even low-dose

PCB exposure can impair epithelial regeneration, metabolism, and

immune regulation supports the need for health surveillance in

exposed populations, particularly those with high dietary intake of

contaminated fish or those residing in regions with persistent PCB

contamination. In this aspect, the in vivo toxicokinetic

studies of PCB153 bioaccumulation, including absorption,

distribution, tissue persistence, and dose-time relationships in

animal models, would indeed be highly valuable for future work.

Such studies would help define physiologically relevant exposure

ranges in the intestine and provide quantitative context for

interpreting the transcriptomic responses observed in vitro.

While toxicokinetic modeling and in vivo bioaccumulation

analyses are beyond the scope of the present study, we believe that

integrating these approaches in future investigations would

strengthen translational interpretation and help bridge in

vitro responses with real world exposure scenarios. These

mechanistic insights may also inform future strategies to mitigate

toxicant effects, such as dietary or pharmacological interventions

that restore epithelial integrity or enhance detoxification

capacity, eventually offering a strategy toward personalized

approaches to environmental health protection.

In conclusion, our findings support and extend prior

research indicating that PCB153 exposure adversely affects

intestinal epithelial function. We demonstrate that PCB153 disrupts

multiple pathways essential for epithelial renewal, immune

regulation, and metabolic balance. These findings emphasize the gut

epithelium as a critical and sensitive target of environmental

toxicants and underscore the need for further research using

physiologically relevant exposure models and mechanistic validation

to better assess the health risks associated with PCB exposure.

Supplementary Material

Primers for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This work was supported by the Department of

Pediatrics, University of Illinois at Chicago and US National

Institutes of Health (grant no. P30ES027792).

Availability of data and materials

The RNA sequencing data generated in the present

study may be found in the National Center for Biotechnology

Information database under accession number PRJNA1285092 or at the

following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1285092.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HH and PS conceived the study, analyzed data and

wrote the manuscript. SCT analyzed data and edited the manuscript.

RMS and GSP acquired funding, interpreted data, and reviewed and

edited the manuscript. HG supervised the study, designed the

methodology, interpreted data, and wrote, reviewed and edited the

manuscript. HH and HG confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Carpenter DO: Polychlorinated biphenyls

(PCBs): Routes of exposure and effects on human health. Rev Environ

Health. 21:1–23. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

McLachlan MS, Undeman E, Zhao F and

MacLeod M: Predicting global scale exposure of humans to PCB 153

from historical emissions. Environ Sci Process Impacts. 20:747–756.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Wood SA, Armitage JM, Binnington MJ and

Wania F: Deterministic modeling of the exposure of individual

participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination

Survey (NHANES) to polychlorinated biphenyls. Environ Sci Process

Impacts. 18:1157–1168. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Desvignes V, Volatier JL, de Bels F,

Zeghnoun A, Favrot MC, Marchand P, Le Bizec B, Riviere G, Leblanc

JC and Merlo M: Study on polychlorobiphenyl serum levels in French

consumers of freshwater fish. Sci Total Environ. 505:623–632.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Chelakkot C, Ghim J and Ryu SH: Mechanisms

regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological

implications. Exp Mol Med. 50:1–9. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Peterson LW and Artis D: Intestinal

epithelial cells: Regulators of barrier function and immune

homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 14:141–153. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Choi YJ, Seelbach MJ, Pu H, Eum SY, Chen

L, Zhang B, Hennig B and Toborek M: Polychlorinated biphenyls

disrupt intestinal integrity via NADPH oxidase-induced alterations

of tight junction protein expression. Environ Health Perspect.

118:976–981. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Phillips MC, Dheer R, Santaolalla R,

Davies JM, Burgueño J, Lang JK, Toborek M and Abreu MT: Intestinal

exposure to PCB 153 induces inflammation via the ATM/NEMO pathway.

Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 339:24–33. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Moyer MP, Manzano LA, Merriman RL,

Stauffer JS and Tanzer LR: NCM460, a normal human colon mucosal

epithelial cell line. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 32:315–317.

1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow

J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M and Gingeras TR: STAR:

Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 29:15–21.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T,

Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G and Durbin R: 1000 Genome

Project Data Processing Subgroup. The sequence alignment/Map format

and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25:2078–2079. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Anders S, Pyl PT and Huber W: HTSeq-a

Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data.

Bioinformatics. 31:166–169. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Love MI, Huber W and Anders S: Moderated

estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with

DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15(550)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y and He QY:

clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among

gene clusters. OMICS. 16:284–287. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ge SX, Jung D and Yao R: ShinyGO: A

graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants.

Bioinformatics. 36:2628–2629. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Socha-Banasiak A, Sputa-Grzegrzółka P,

Grzegrzółka J, Pacześ K, Dzięgiel P, Sordyl B, Romanowicz H and

Czkwianianc E: Metallothioneins in inflammatory bowel diseases:

Importance in pathogenesis and potential therapy target. Can J

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021(6665697)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Waeytens A, De Vos M and Laukens D:

Evidence for a potential role of metallothioneins in inflammatory

bowel diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2009(729172)2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Nait Slimane S, Marcel V, Fenouil T, Catez

F, Saurin JC, Bouvet P, Diaz JJ and Mertani HC: Ribosome biogenesis

alterations in colorectal cancer. Cells. 9(2361)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Silva J, Alkan F, Ramalho S, Snieckute G,

Prekovic S, Garcia AK, Hernández-Pérez S, van der Kammen R, Barnum

D, Hoekman L, et al: Ribosome impairment regulates intestinal stem

cell identity via ZAKa activation. Nat Commun.

13(4492)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zhang H, Vreeken D, Leuning DG, Bruikman

CS, Junaid A, Stam W, de Bruin RG, Sol WMPJ, Rabelink TJ, van den

Berg BM, et al: Netrin-4 expression by human endothelial cells

inhibits endothelial inflammation and senescence. Int J Biochem

Cell Biol. 134(105960)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Sensoy I: A review on the food digestion

in the digestive tract and the used in vitro models. Curr Res Food

Sci. 4:308–319. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Fleckenstein JM and Bitoun JP: Changing

the locks on intestinal signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 29:1335–1337.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Rappaport JA and Waldman SA: The guanylate

cyclase C-cGMP signaling axis opposes intestinal epithelial injury

and neoplasia. Front Oncol. 8(299)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Dietrich CG, Geier A and Oude Elferink

RPJ: ABC of oral bioavailability: Transporters as gatekeepers in

the gut. Gut. 52:1788–1795. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Flanagan DJ, Austin CR, Vincan E and

Phesse TJ: Wnt signalling in gastrointestinal epithelial stem

cells. Genes (Basel). 9(178)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Mah AT, Yan KS and Kuo CJ: Wnt pathway

regulation of intestinal stem cells. J Physiol. 594:4837–4847.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Lazarova D and Bordonaro M: Multifactorial

causation of early onset colorectal cancer. J Cancer. 12:6825–6834.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Li J, Ma X, Chakravarti D, Shalapour S and

DePinho RA: Genetic and biological hallmarks of colorectal cancer.

Genes Dev. 35:787–820. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ullman TA and Itzkowitz SH: Intestinal

inflammation and cancer. Gastroenterology. 140:1807–1816.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Stolfi C, Maresca C, Monteleone G and

Laudisi F: Implication of intestinal barrier dysfunction in gut

dysbiosis and diseases. Biomedicines. 10(289)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Zong Y, Li H, Liao P, Chen L, Pan Y, Zheng

Y, Zhang C, Liu D, Zheng M and Gao J: Mitochondrial dysfunction:

Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

9(124)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Jacobson A, Yang D, Vella M and Chiu IM:

The intestinal neuro-immune axis: Crosstalk between neurons, immune

cells, and microbes. Mucosal Immunol. 14:555–565. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Treps L, Le Guelte A and Gavard J:

Emerging roles of Semaphorins in the regulation of epithelial and

endothelial junctions. Tissue Barriers. 1(e23272)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Agudo A, Goñi F, Etxeandia A, Vives A,

Millán E, López R, Amiano P, Ardanaz E, Barricarte A, Chirlaque MD,

et al: Polychlorinated biphenyls in Spanish adults: Determinants of

serum concentrations. Environ Res. 109:620–628. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Cerná M, Malý M, Grabic R, Batáriová A,

Smíd J and Benes B: Serum concentrations of indicator PCB congeners

in the Czech adult population. Chemosphere. 72:1124–1131.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Leong JY, Blachman-Braun R, Patel AS,

Patel P and Ramasamy R: Association between polychlorinated

biphenyl 153 exposure and serum testosterone levels: Analysis of

the national health and nutrition examination survey. Transl Androl

Urol. 8:666–672. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Longnecker MP, Wolff MS, Gladen BC, Brock

JW, Grandjean P, Jacobson JL, Korrick SA, Rogan WJ,

Weisglas-Kuperus N, Hertz-Picciotto I, et al: Comparison of

polychlorinated biphenyl levels across studies of human

neurodevelopment. Environ Health Perspect. 111:65–70.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|