Introduction

Bone remodeling is an ongoing and intricate

physiological process essential for preserving bone integrity and

functionality. It depends on the balance between

osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and osteoblast-driven bone

formation (1). Osteoporosis is

defined by a disruption in the equilibrium between bone resorption

and formation, resulting in diminished bone density and a

heightened susceptibility to fractures (2). The compromised ability of bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) to undergo osteogenic

differentiation is a critical factor underlying the reduced

capacity for bone formation (3).

BMSCs are pivotal in bone formation during remodeling and repair.

Research into conditions such as bone defects and osteoporosis

focuses on guiding bone remodeling toward formation by modulating

BMSCs (4). In the field of oral

regenerative repair, BMSCs have demonstrated tremendous potential

in promoting alveolar bone repair and regeneration. Numerous

studies have shown that BMSCs significantly enhance the

regeneration of alveolar bone defects whether used alone or in

combination with materials such as fibrin glue or scaffolds

(5,6). The use of BMSCs in periodontal bone

tissue regeneration and repair has significant potential to enhance

the scope of tooth movement and extend the applicability to

orthodontic and dental interventions, ultimately delivering safer

and more effective treatment alternatives for patients.

Autophagy plays an essential role in osteogenesis

and periodontal bone tissue regeneration. Autophagy is a cellular

self-degradation and recycling process in which damaged or excess

organelles, proteins, and other macromolecules are enclosed in

autophagosomes and eventually degraded within lysosomes (7). This mechanism supports cellular

homeostasis and allows cells to manage stress conditions such as

nutrient deprivation or oxidative stress, significantly impacting

numerous physiological and pathological processes (8). Autophagy is integral to the

development and progression of human diseases, with numerous

studies highlighting its close association with various conditions

(9); it suppresses early

tumorigenesis but promotes survival in advanced cancer (10), contributes to neurodegeneration (for

example Parkinson s disease) via defective protein/organelle

clearance (11), modulates

cardiovascular injury outcomes (12), exacerbates metabolic disorders such

as type 2 diabetes when impaired (13), and participates in host defense

against pathogens (14). Research

on cellular autophagy is crucial for understanding cell biology and

disease mechanisms, potentially leading to novel therapeutic

discoveries. Studies have shown that autophagy levels increase in a

time-dependent manner during the osteogenic differentiation of

BMSCs, highlighting its essential role in promoting osteogenesis

(15,16). Specifically, autophagy activation

promotes the differentiation of BMSCs into osteoblasts. Moreover,

under conditions of nutrient deprivation or oxidative stress,

autophagy can sustain osteoblast activity by clearing damaged

mitochondria and proteins (17).

Research has shown that hypoxic conditions in the local periodontal

microenvironment caused by orthodontic treatments can induce

autophagy, thereby affecting the remodeling of periodontal bone

tissue (18). Therefore,

understanding the mechanisms underlying autophagy in BMSCs holds

substantial clinical and research value.

Autophagy progresses from initiation to

autophagosome-lysosome fusion and the eventual degradation of

cellular contents (19). The

mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is a central regulator

of cellular autophagy, orchestrating the autophagy process through

diverse molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways. mTOR responds

to various signals such as cellular nutritional status, energy

levels, and growth factors to adjust the metabolism and growth of

the cell (20). mTOR affects

autophagy through downstream proteins such as neural precursor

cell-expressed developmentally down-regulated protein 4 (NEDD4).

NEDD4 consists of an N-terminal C2 domain, a C-terminal HECT

domain, and two to four WW domains (21). Studies have shown that NEDD4 is

essential for the survival of cranial neural crest cells and the

development of craniofacial bones (22). Mice with Nedd4 gene deletion

were shown to exhibit notable craniofacial defects (23). Furthermore, osteoprogenitor cells

lacking NEDD4 exhibited impaired osteogenic differentiation

(24). Our preliminary research has

also shown that NEDD4 knockout promotes osteogenic differentiation

in BMSCs (25). Notably, the role

that NEDD4 plays in autophagy has also attracted attention. NEDD4,

an E3 ubiquitin ligase, facilitates protein degradation through

ubiquitination. NEDD4 influences the stability and function of

autophagy-related proteins, including light chain 3 (LC3) and

Beclin-1, via direct or indirect ubiquitination. These proteins are

recognized autophagy markers and exhibit increased expression

levels during autophagic activity (26-29).

Tumor cell research has shown that NEDD4 promotes autophagy and is

associated with the mTOR signaling pathway (30). Meanwhile, our preliminary research

revealed that NEDD4 knockout increased the expression of

mTORC1(25). mTORC1, a key element

of the mTOR signaling pathway, was essential for autophagy

regulation.

Based on these observations, it was hypothesized

that NEDD4 expression in BMSCs promotes autophagy via the mTOR

pathway. To test this hypothesis, autophagy was induced in BMSCs

under starvation conditions and NEDD4 expression was modulated by

lentiviral knockdown. The changes were then examined in autophagy

(LC3 and Beclin-1 levels) and mTOR pathway activity in response to

NEDD4 knockdown. Through this experimental design, the effect of

NEDD4 on starvation-induced autophagy in BMSCs via mTOR was sought

to be elucidated, and the potential of NEDD4 as a novel therapeutic

target for conditions such as periodontal bone defects and

osteoporosis was aimed to be determined.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male, 4-week-old Sprague-Dawley rats (n=8; body

weight, 80-100 g) were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center

of Southwest Medical University (Luzhou, China). The animals were

housed under standard laboratory conditions with a controlled

temperature of 20-26˚C, a relative humidity of 40-70%, a 12-h

light/dark cycle, and ad libitum access to standard rodent

chow and sterile drinking water. After euthanasia by carbon dioxide

asphyxiation, femurs were dissected for BMSC extraction. For

euthanasia, carbon dioxide (CO2) was introduced into an

uncharged chamber at a displacement rate of 30-70% of the chamber

volume per minute, in accordance with the 2020 AVMA Guidelines.

Death was confirmed by cessation of respiration and heartbeat, lack

of corneal reflexes, and a secondary physical method (cervical

dislocation). Ethical approval for the animal experiments was

granted by the Ethics Committee of Southwest Medical University in

Luzhou, Sichuan, China (approval no. 20221206-005).

Cell culture and identification

The rat femurs were dissected and rinsed with

sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; cat. no. 1001002; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. 3), and the soft tissues attached to

the femurs were removed in a sterile biosafety cabinet. α-Minimum

essential medium (α-MEM; cat no. 12561056; Gibco, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat. no.

10099141; Gibco;Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used for cell

culture.

The BMSC cell suspension was centrifuged at 1,000 x

g at 4˚C for 5 min and then resuspended in α-MEM supplemented with

10% FBS, 100 µg/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (cat. no.

15140122; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and incubated in

a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37˚C. After

48 h, the medium was replaced with fresh medium to remove

non-adherent cells. When cell confluency reached 80%, the cells

were passaged, and the passaged cells were designated as passage 1

(P1). Subsequent experiments were performed using third-passage

cells (P3).

Flow cytometry was performed to detect the surface

markers of P1 BMSCs (CD29, CD90, CD45, and CD34). The following

primary antibodies were used to label the corresponding markers:

FITC-conjugated anti-rat CD29 antibody (cat. no. 102206, dilution,

1:100; BioLegend, Inc.), PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-rat CD90 antibody

(cat. no. 202517; dilution, 1:100; BioLegend, Inc.), PE-conjugated

anti-rat CD34 antibody (cat no. 551387; dilution, 1:100; BD

Pharmingen; BD Biosciences), and AF647-conjugated anti-rat CD45

antibody (cat. no. 160303; dilution, 1:100; BioLegend, Inc.). All

primary antibodies were directly conjugated with fluorochromes

(FITC, PE-Cy7, PE, and AF647 as reporter moieties); therefore, no

secondary antibodies were required. Detection was performed using a

direct immunofluorescence assay with a flow cytometer, and the

fluorochrome-conjugated primary antibodies were excited at their

respective optimal wavelengths to detect fluorescence signals.

After incubation for 30 min at 4˚C in the dark, the cells were

analyzed using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACSCalibur;

BD Biosciences). Data acquisition and analysis were performed using

FlowJo software (version 10.8.1; FlowJo LLC). The protocol for

isolating and identifying BMSCs was consistent with previously

described methods (31).

Multilineage differentiation induction

and starvation-induced autophagy

P3 BMSCs were cultured in 6-well plates until cell

confluence exceeded 80%, after which the medium was switched to

either adipogenic or osteogenic induction medium, with the medium

changed every three days. The adipogenic induction medium consisted

of α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 µM dexamethasone (cat. no.

D8040), 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX; cat. no.

II00101), 10 µg/ml insulin (cat. no. I8040), and 100 µM

indomethacin (cat. no. II0100; all from Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.). The osteogenic induction medium

consisted of α-MEM with 10% FBS, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (cat. no.

G9140), 50 µg/ml L-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate sesquimagnesium salt

hydrate (cat. no. A8960-5G; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), and 100 nM

dexamethasone (cat. no. D8040; all from Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.). Cells were washed three times with PBS

and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature on

the 14th day of adipogenic induction and the 21st day of osteogenic

induction. Alizarin Red S (cat. no. G1452) and Oil Red O (cat. no.

G1262; both from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) were used to stain osteogenically and adipogenically induced

cells, respectively, according to the manufacturer s

instructions.

Autophagy was induced by nutrient starvation.

Nutrient deprivation using Earle s balanced salt solution

(EBSS; cat. no. H2045) is a standard approach to trigger autophagy

by acutely limiting amino acids and growth factors; this method is

widely used to assess upstream regulators of autophagy. EBSS was

therefore selected to induce autophagy in BMSCs (32,33).

Briefly, P3 BMSCs in a logarithmic growth condition were switched

to EBSS once confluence reached ~70%, marking time point 0 as the

start of induction.

Lentiviral infection

Lentiviruses expressing short hairpin RNA (shRNA)

targeting NEDD4 (sh-NEDD4) and a non-targeting control shRNA

(sh-NC) were constructed using the GV493 lentiviral vector

(hU6-MCS-CBh-gcGFP-IRES-puromycin; Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd.).

Lentiviral packaging was performed using 293T cells (cat. no.

SNL-015; Wuhan SunnCell Biotech Co., Ltd.) as the packaging cell

line. For each 6-well plate transfection, 4 µg of lentiviral

plasmids (sh-NEDD4 or sh-NC) were utilized, with lentiviral,

packaging (psPAX2) and envelope (pMD2.G) plasmids mixed at a strict

mass ratio of 4:3:1. The transfection was carried out in at 37˚C

incubator supplemented with 5% CO2 for 48 h

consecutively. Culture supernatants harboring lentiviral particles

were harvested at 48 and 72 h post-transfection, subjected to

centrifugation at 1,000 x g for 20 min at 4˚C and filtration

through a 0.45-µm filter membrane to eliminate cell debris, thus

obtaining purified lentiviral particles. Following lentiviral

transduction of BMSCs, the cells were cultured for an additional 72

h to ensure sufficient viral integration prior to initiating

subsequent nutrient deprivation experiments. Puromycin (cat. no.

P8230; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) was

utilized for positive selection of stably transduced cell clones,

with a selection concentration of 3.5 µg/ml and a maintenance

concentration of 1.5 µg/ml during long-term subsequent culture. The

specific target sequences of the shRNAs are detailed in Table I. For the transduction procedure,

passage 3 (P3) BMSCs in the logarithmic growth phase were detached

with trypsin and adjusted to a cell density of 5x104

cells/ml. Each well of a 6-well plate was seeded with 1 ml of the

cell suspension, after which the cells were co-incubated with

lentivirus in the presence of HitransG P transduction enhancer for

16 h at 37˚C. Fresh growth medium was replenished at 24 h

post-transduction. The multiplicity of infection (MOI) was

determined using the formula: (virus titer x volume of virus

added)/number of cells, and an optimal MOI of 50 was selected and

applied in all experiments of this study.

| Table IshRNA target sequences used in this

study. |

Table I

shRNA target sequences used in this

study.

| shRNA ID | Accession | Target sequence

(5 →3 ) |

|---|

| sh-NC | NM_012986 |

TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT |

| sh1 | NM_012986 |

AGCCACAAATCAAGAGTTAAA |

| sh2 | NM_012986 |

TTGGAAGGACCTACTACGTAA |

| sh3 | NM_012986 |

CTGGATTGAGTTTGATGGTGA |

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells using the TRIzol

reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, inc.) according to

the manufacturer s instructions. cDNA synthesis was carried

out with the PrimeScript Reverse Transcription Kit (Takara Bio,

Inc.). RT-qPCR with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara Bio, Inc.) was used

to quantify the gene expression levels of NEDD4, LC3, and Beclin-1

(Becn1) with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

(GAPDH) as the reference gene. The thermocycling conditions were as

follows: Initial denaturation at 95˚C for 30 sec, followed by 40

cycles at 95˚C for 5 sec and 60˚C for 30 sec; a melt-curve analysis

was performed to confirm specificity. Relative expression was

calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq method (34). Primer sequences are provided in

Table II.

| Table IIPrimer sequences of the measured

genes. |

Table II

Primer sequences of the measured

genes.

| Genes | Sequence of primers

(5 →3 ) |

|---|

| GAPDH | R:

TAGCCCAGGATGCCCTTTAGT |

| | F:

CCCCCAATGTATCCGTTGTG |

| LC3B | R:

GCCGAAGGTTTCTTGGGAGG |

| | F:

TTGGTCAAGATCATCCGGCG |

|

Beclin-1 | R:

AATTGTCCGCTGTGCCAGATATG |

| | F:

GCTCAAGAGTGTAGAGAACCAGA |

| NEDD4 | R:

GCCAGACCTATGCCAGCTAT |

| | F:

GCTTTCGGAGGACGAGGTAT |

Western blotting

Cellular protein was extracted with RIPA lysis

buffer containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer s

instructions. The protein concentration was measured using a BCA

assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Western blotting

was performed according to standard protocols (35). Specifically, equal amounts of total

protein (20-30 µg per lane) were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and

transferred to PVDF membranes (0.45 µm). Membranes were blocked

with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; cat. no. SW3015; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) in TBST containing

0.1% Tween-20 for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated overnight

at 4˚C with primary antibodies: GAPDH [cat. no. 2118;

1:3,000-1:5,000; Cell Signaling Technology (CST)], LC3B (cat. no.

ab192890; 1:1,000; Abcam), Beclin-1 (cat. no. 3495; 1:1,000; CST),

NEDD4 (cat. no. 2740; 1:1,000; CST), total mTOR (cat. no. 2983;

1:1,000; CST), and phospho-mTOR (Ser2448; cat. no. 5536; 1:1,000;

CST). After washing, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated

secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit IgG, cat. no. 7074; anti-mouse

IgG, 7076; each at 1:5,000; CST) for 1 h at room temperature. Bands

were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescent substrate

(SuperSignal West Pico PLUS; cat. no. 34580; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and imaged on a digital chemiluminescence system.

Within each composite figure panel, proteins were probed on the

same membrane (using membrane cutting or strip-and-reprobe) unless

otherwise indicated. Densitometric analysis of the blots was

performed using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0_172; National

Institutes of Health).

Immunofluorescence

Cells were seeded into 24-well plates at a density

of 1x104 cells per well. After adherence, cells were

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature,

permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room

temperature, and blocked with 5% BSA for 60 min at room

temperature. Cells were then incubated overnight at 4˚C with an

anti-LC3 primary antibody (cat. no. ab192890; 1:1,000; Abcam). The

following day, cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated

for 1 h at room temperature with an Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit secondary antibody (cat. no. 31460; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at a dilution of 1:1,000 in 5% BSA/PBS for 1 h at

room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with

4 ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; cat. no. C0065; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at a dilution of

1:5,000 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. After washing with

PBS, the cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope

(Olympus Corporation). These immunocytochemical procedures followed

previously published protocols (35).

Transmission electron microscopy

(TEM)

Autophagic vesicles (AVs) were visualized using TEM.

Cells were collected by gentle scraping and initially fixed in 3%

glutaraldehyde (cat. no. G5882; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in 0.1 M

phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 4˚C for 2 h, followed by post-fixation

with 1% osmium tetroxide (cat. no. 201030; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) at 4˚C for 30 min. Cells were dehydrated through a graded

ethanol series, embedded in Epon resin (cat. no. 45345;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), and ultrathin sections with a thickness

of 50 nm were prepared. The sections were stained with 2% uranyl

acetate (cat. no. S9062-5; RuiTaibio) at room temperature for 15

min, followed by lead citrate (cat. no. 17800; Electron Microscopy

Sciences) at room temperature for 10 min. Subcellular structures

were examined using a JEM-2000EX transmission electron microscope

(JEOL, Ltd.).

Statistical analysis

Data processing and visualization were performed

using GraphPad Prism (version 9.0; GraphPad Software; Dotmatics).

All experiments were conducted in triplicate (n=3). Results are

presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way ANOVA was

used to evaluate group differences. Following one-way ANOVA,

Tukey s multiple-comparison post hoc test was applied for

pairwise comparisons. A two-sided α value of 0.05 was considered

the threshold for statistical significance; P-values <0.05 were

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Culture and identification of

BMSCs

Cells were extracted from rat femurs using whole

bone marrow adherent culture techniques. After passaging, the cells

exhibited a uniform fibroblast-like morphology and were arranged in

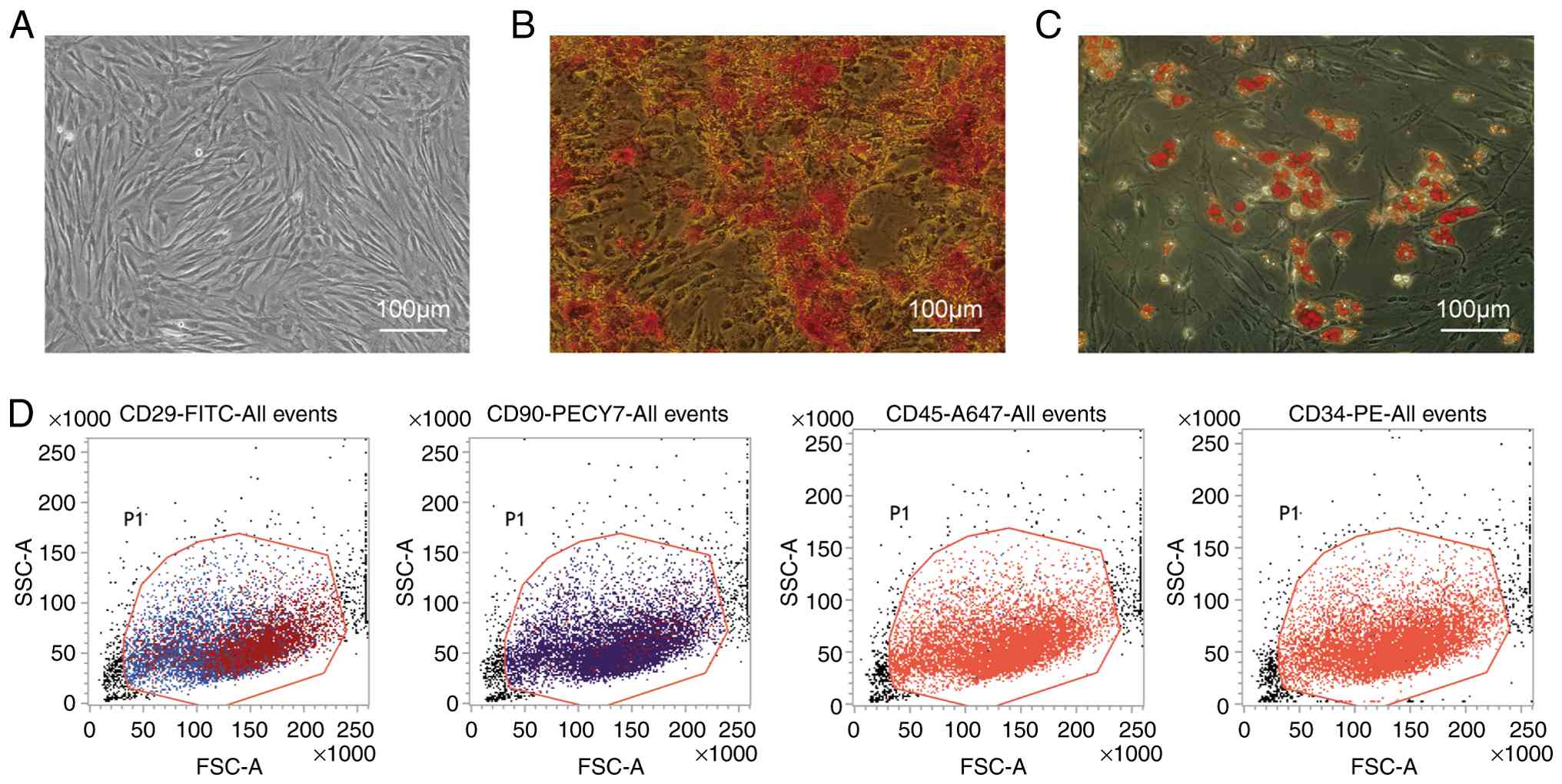

a vortex pattern (Fig. 1A).

Multilineage differentiation potential was observed. On day 21 of

osteogenic induction, Alizarin Red S staining revealed numerous

orange-red calcium nodules (Fig.

1B). Oil Red O staining after 14 days of adipogenic induction

showed the presence of red lipid droplets, demonstrating the

adipogenic potential of the cultured cells (Fig. 1C). Flow cytometric analysis

indicated high expression of mesenchymal stem cell markers CD90

(98.73%) and CD29 (95.99%), whereas hematopoietic stem cell markers

CD34 and CD45 were minimally expressed (0.3 and 0.05%,

respectively), consistent with mesenchymal stem cell

characteristics (Fig. 1D). These

findings verify the successful isolation and culture of rat

BMSCs.

Autophagy induction and expression of

autophagy-related genes

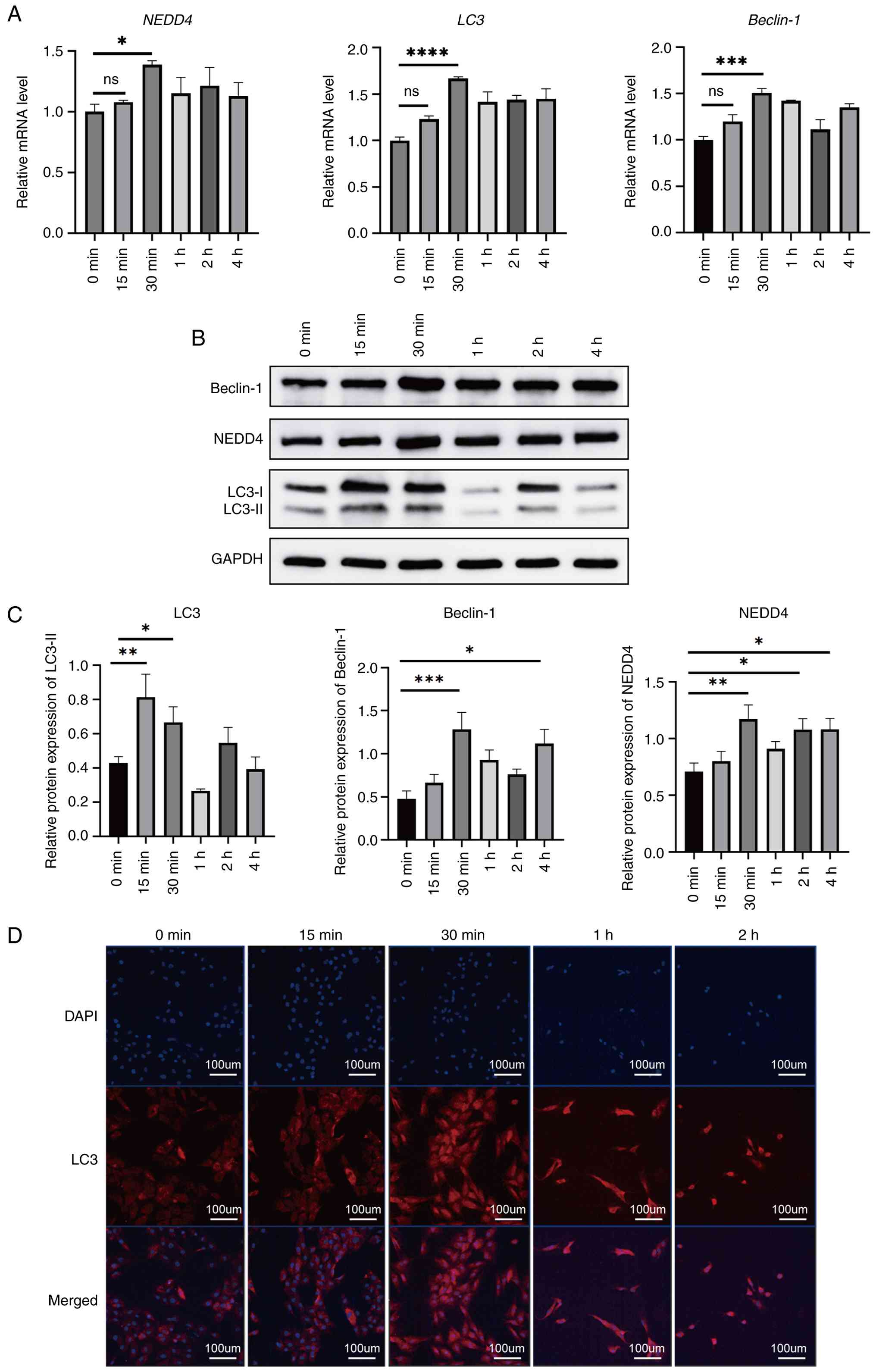

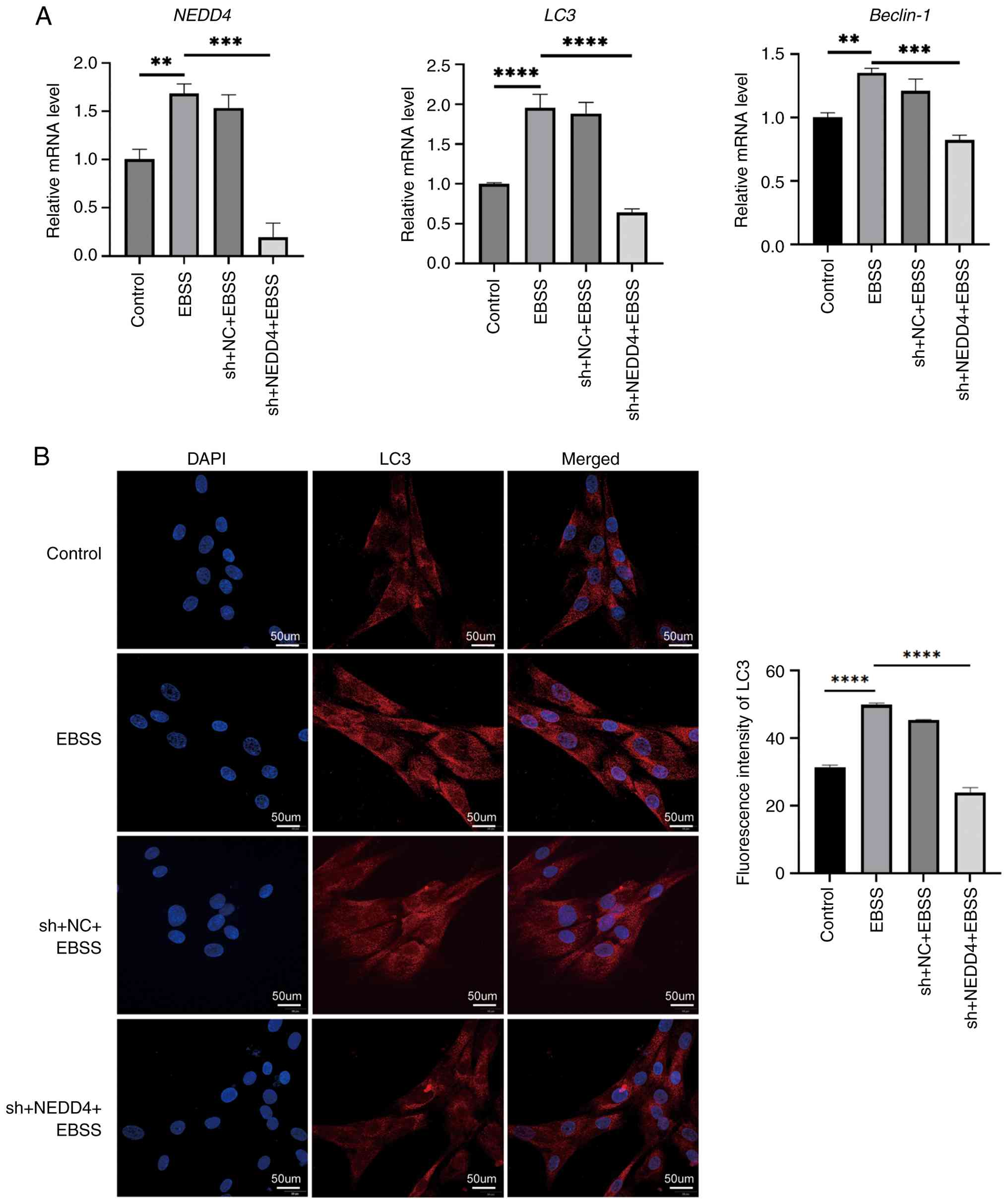

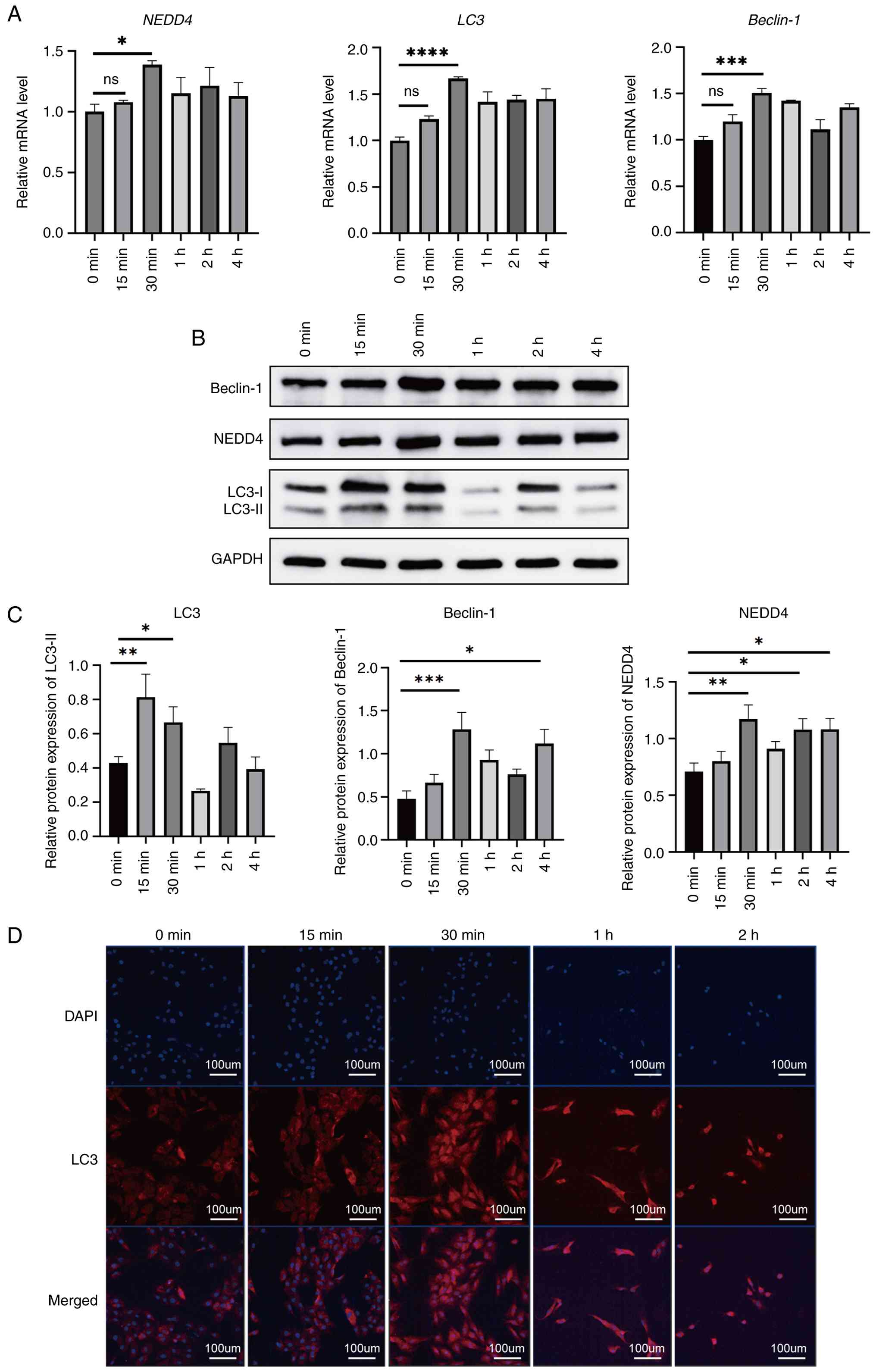

Autophagy in BMSCs was induced by EBSS starvation,

and cells were collected at specific time points. RT-qPCR analysis

showed that the mRNA expression of NEDD4 and autophagy-related

genes LC3 and Beclin-1 gradually increased, peaking at 30 min

post-induction, and then decreased by 1 h (Fig. 2A). Western blot analysis showed that

NEDD4 protein levels, along with autophagy markers LC3-II and

Beclin-1, were elevated in BMSCs following EBSS starvation (with a

maximum expression at ~30 min; Fig.

2B and C). Immunofluorescent

staining further confirmed autophagy induction in BMSCs (Fig. 2D). LC3 was mainly expressed in the

cytoplasm, and the fluorescence intensity of LC3 increased during

the first 30 min of starvation. After 1 and 2 h, LC3 fluorescence

remained strong, but the number of cells in the field of view

decreased significantly and cell morphology changed. By 2 h,

numerous cells exhibited pronounced shrinkage.

| Figure 2Time-course of autophagy induction in

BMSCs following EBSS starvation. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of NEDD4,

LC3, and Beclin-1 mRNA levels at 0, 15, 30 min, and 1, 2, 4 h

post-starvation. (B and C) A representative western blot image and

quantification of autophagy-related proteins NEDD4, LC3-I and -II,

and Beclin-1 over time. (D) Representative immunofluorescent images

showing LC3 (red) localization in the cytoplasm of BMSCs after

starvation. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar,

100 µm. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3).

*P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001 and

****P≤0.0001. BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells;

EBSS, Earle s balanced salt solution; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; NEDD4, neural

precursor cell-expressed developmentally down-regulated protein 4;

LC3, light chain 3; DAPI, 4 ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; ns,

not significant. |

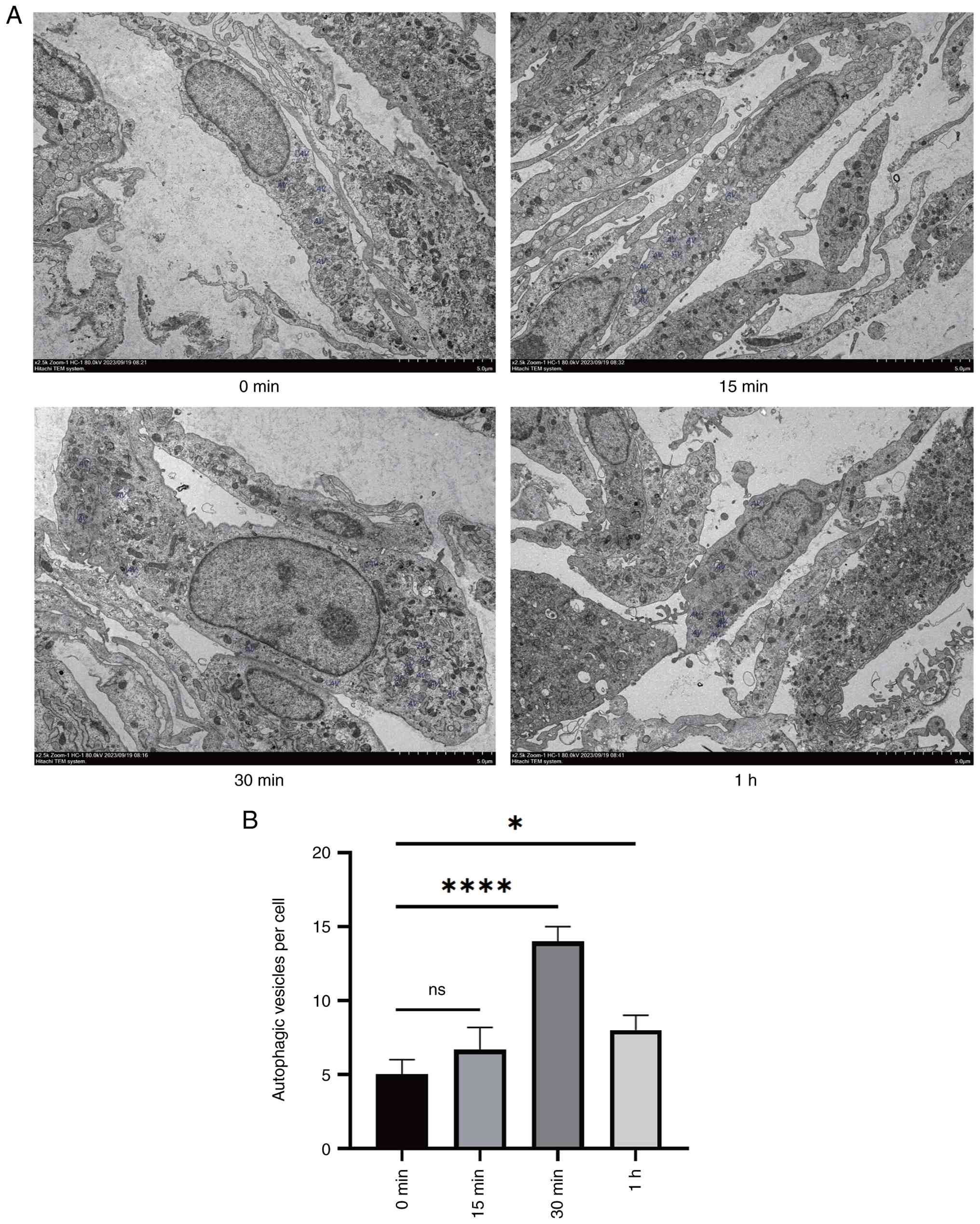

TEM was employed to evaluate the formation of AVs

among different groups. The results showed that there was a

tendency for AV accumulation after starvation induction, reflecting

autophagy induction, and the 30-min starvation group exhibited

significant accumulation (Fig. 3).

In addition, morphological changes such as nuclear shrinkage,

fragmentation, and irregular edges were observed in cells 1 h after

starvation, indicating the progression to adverse cellular

conditions or apoptosis (consistent with excessive stress).

Collectively, these results indicated that BMSCs undergo

significant autophagy after 30 min of EBSS induction, which may be

related to increased NEDD4 expression.

Knockdown of NEDD4 inhibits autophagy

in BMSCs

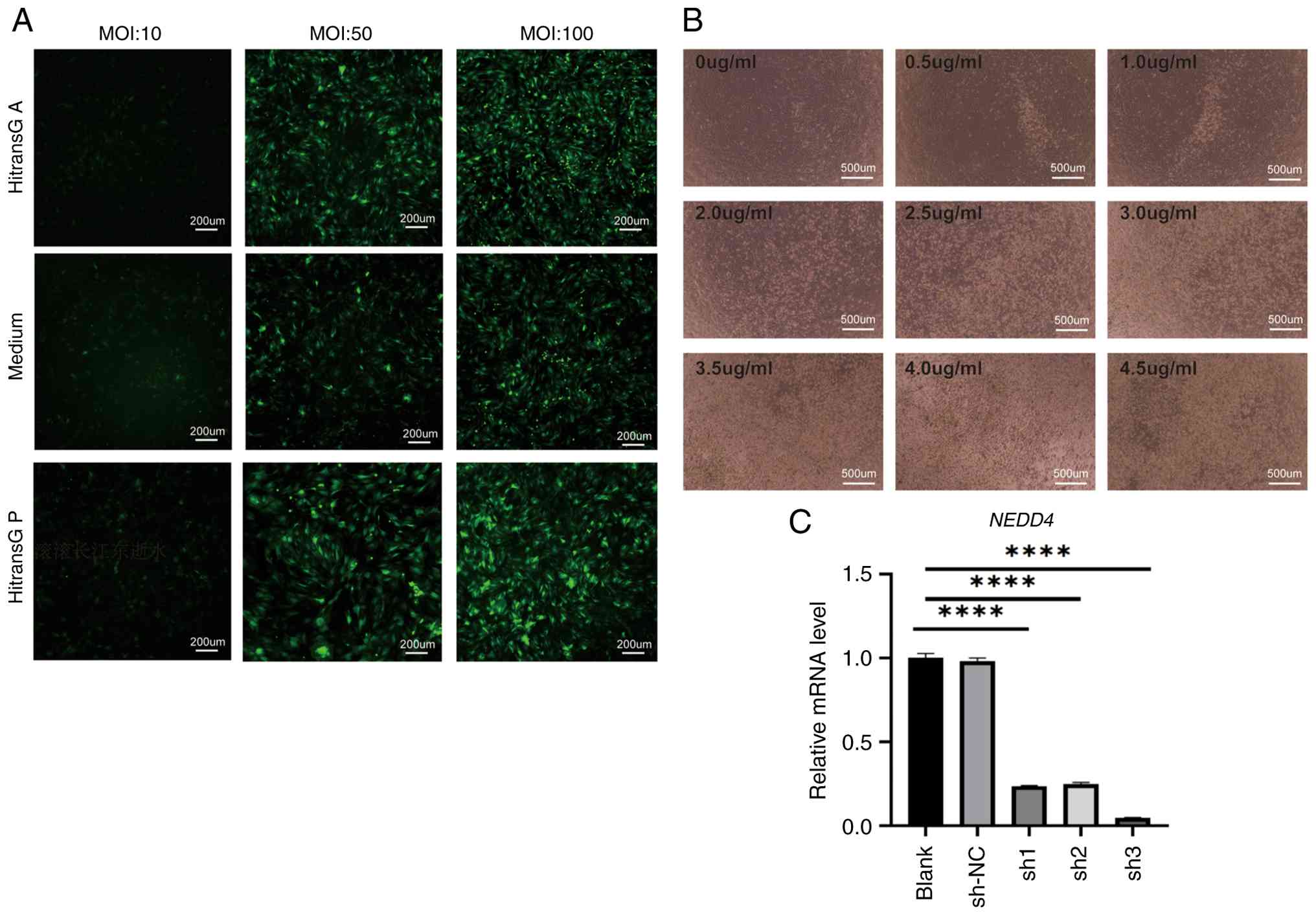

Lentivirus-mediated NEDD4 knockdown was performed in

BMSCs to investigate the role of NEDD4 in autophagy. The optimal

infection condition was achieved using HitransG P with an MOI of 50

(Fig. 4A). Successful infection was

further confirmed by puromycin selection, with optimal selection

efficiency observed at a puromycin concentration of 3.5 µg/ml

(Fig. 4B). RT-qPCR analysis

revealed that among three shRNA sequences assessed, the sh3

sequence produced the most effective silencing of the NEDD4 gene.

Therefore, the sh3 virus was selected for use in subsequent

experiments (Fig. 4C).

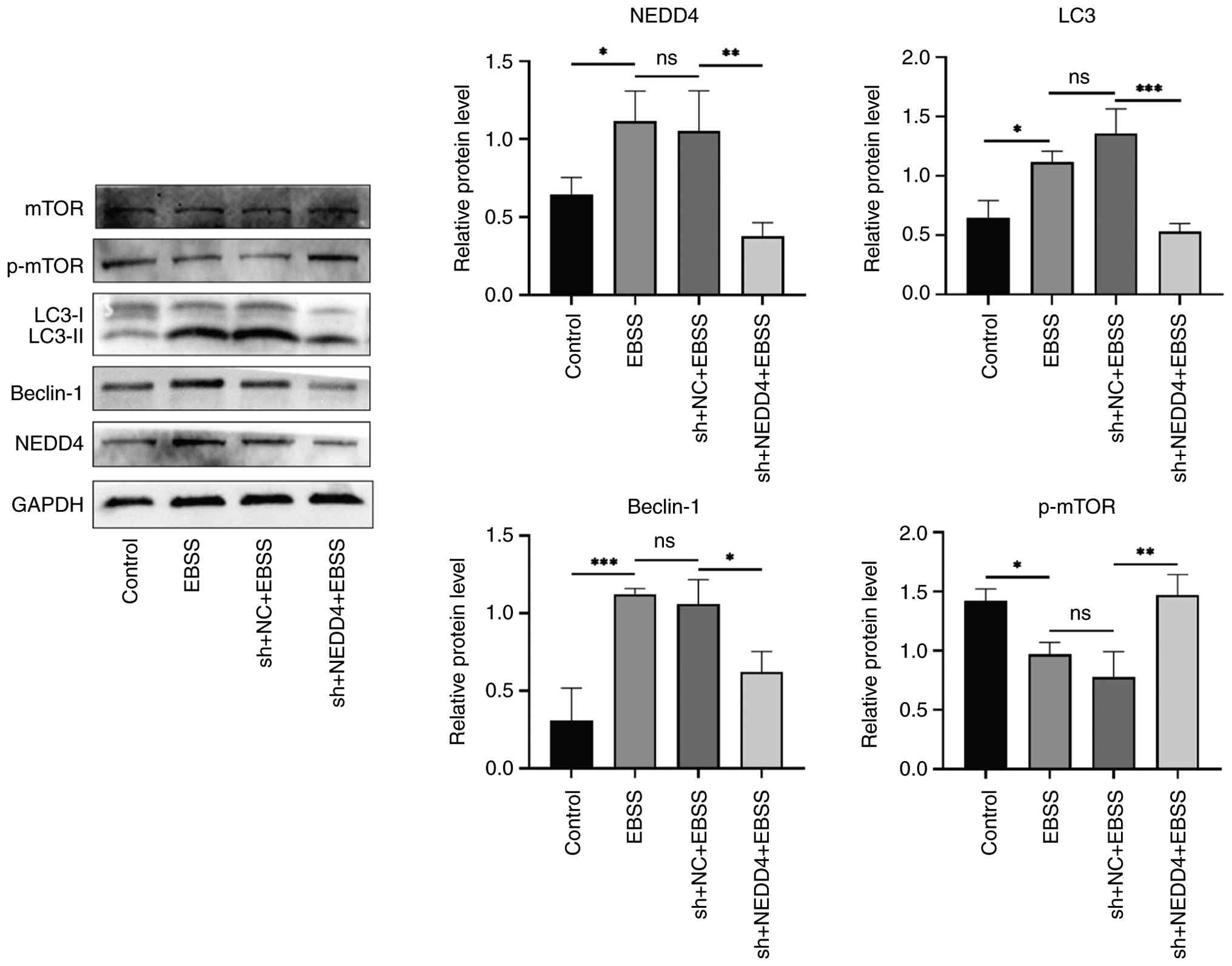

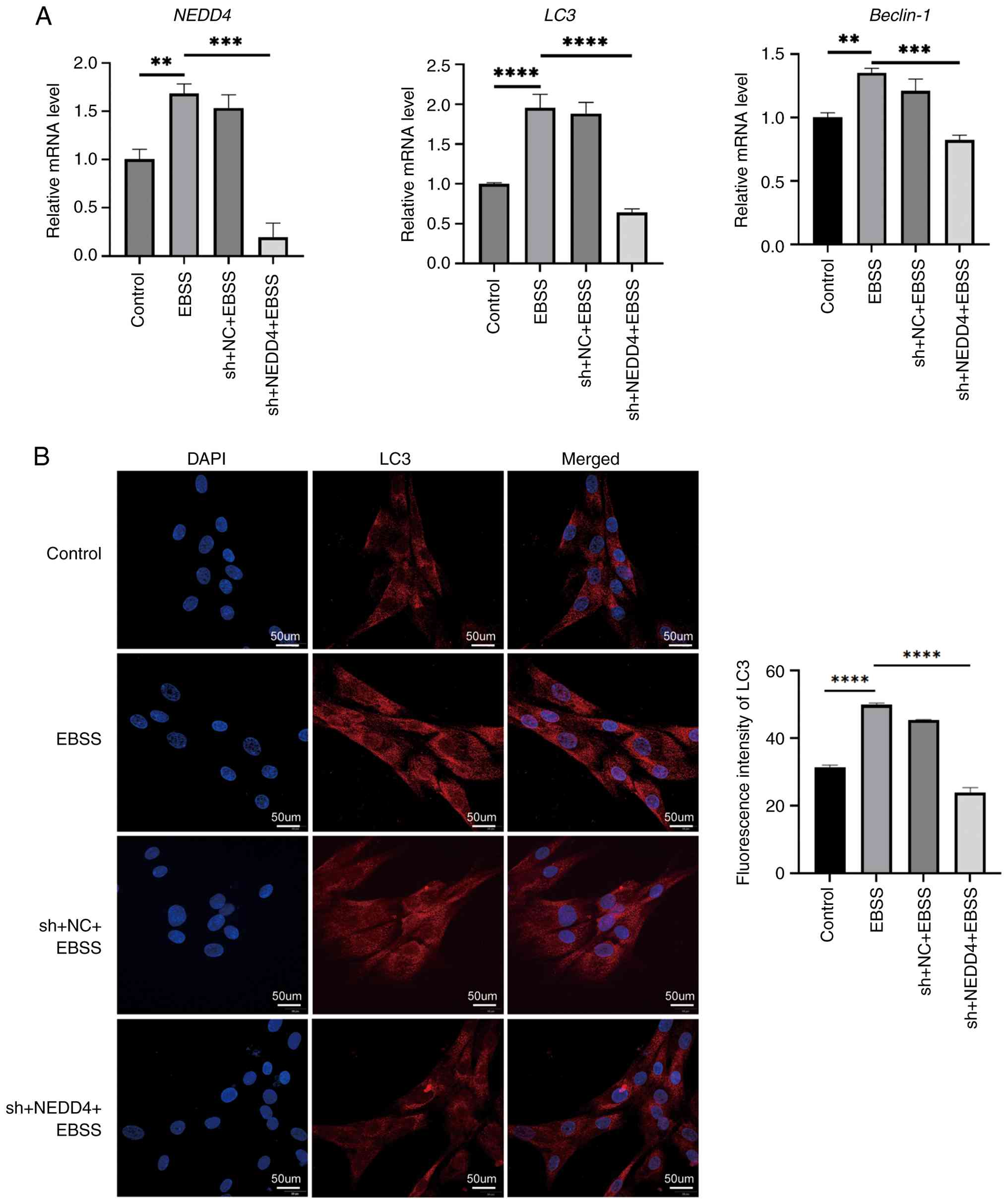

Upon EBSS starvation, NEDD4-knockdown BMSCs

exhibited a marked reduction in autophagy compared with controls.

NEDD4 knockdown significantly blunted the starvation-induced

increases in LC3 and Beclin-1 expression, keeping them below

baseline levels (Fig. 5A).

Immunofluorescent staining of LC3 (Fig.

5B) further demonstrated that autophagy was markedly suppressed

in NEDD4-deficient cells: LC3 puncta formation and intensity were

significantly lower in the sh-NEDD4 + EBSS group than in the EBSS

(starvation only) group. These results indicated that NEDD4 is

necessary for the full autophagic response in BMSCs under

starvation, suggesting that NEDD4 mediates or positively regulates

autophagy in BMSCs.

| Figure 5NEDD4 knockdown impairs

starvation-induced autophagy in BMSCs. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of

NEDD4, LC3 and Beclin-1 mRNA expression under control, EBSS, sh-NC

+ EBSS, and sh-NEDD4 + EBSS conditions. (B) Representative LC3

immunofluorescent images and quantification. LC3 puncta are

markedly reduced in the NEDD4 knockdown group. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=3). **P≤0.01,

***P≤0.005 and ****P≤0.0001. NEDD4, neural

precursor cell-expressed developmentally down-regulated protein 4;

BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; LC3, light

chain 3; EBSS, Earle s balanced salt solution; sh-, short

hairpin; NC, negative control. |

Possible association between NEDD4 and

the mTOR pathway in the regulation of autophagy

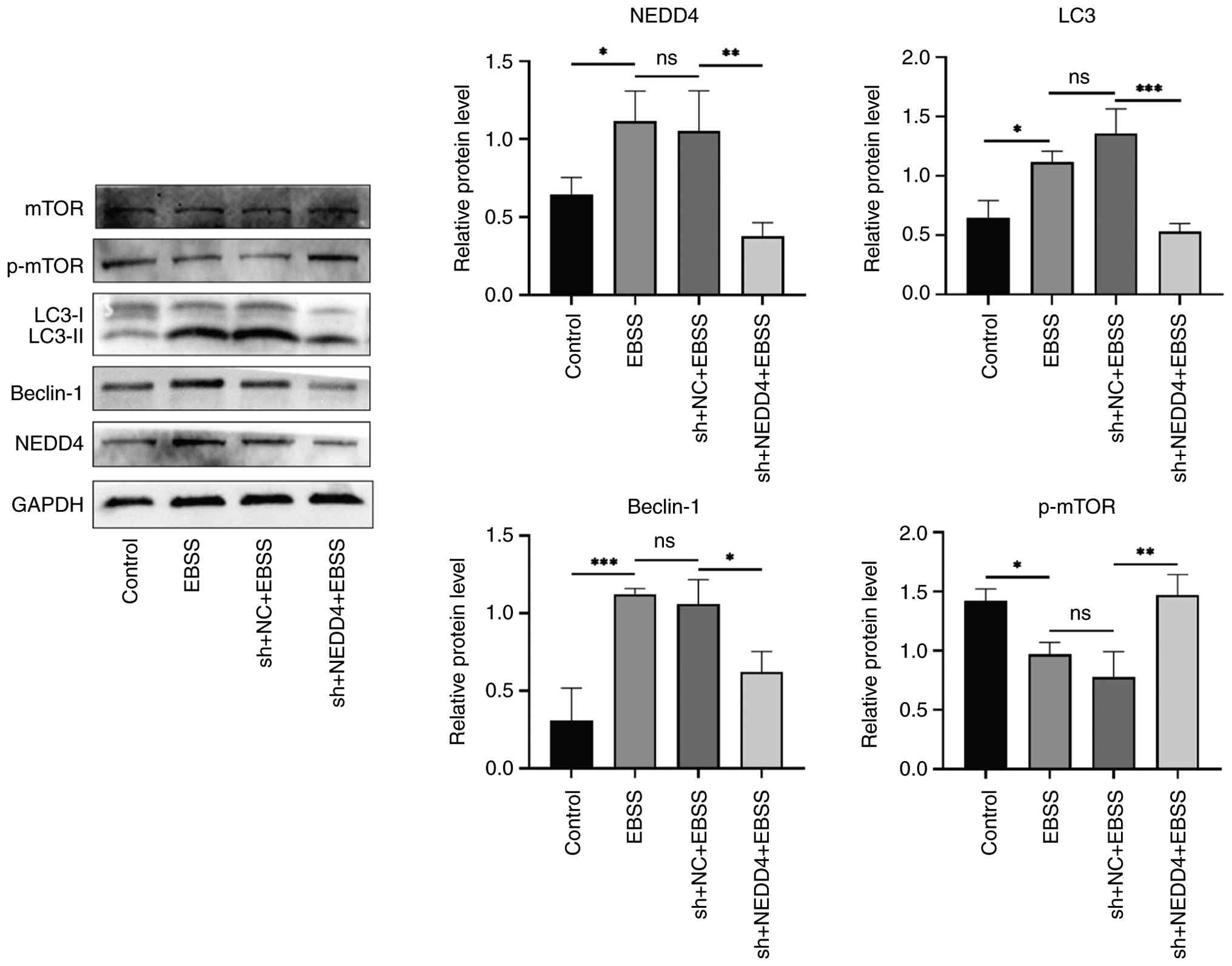

The role of NEDD4 in autophagy in BMSCs was

investigated by examining the mTOR pathway. Western blot analyses

were used to assess mTOR activation status (p-mTOR) as well as

autophagy markers, with and without NEDD4 knockdown (Fig. 6). The results showed that starvation

(EBSS) led to increased protein levels of NEDD4, LC3-II, and

Beclin-1, accompanied by a notable reduction in the level of

p-mTOR, indicating suppression of mTOR activity during autophagy

induction. When NEDD4 was knocked down, this trend was reversed.

p-mTOR levels were restored (reaching higher levels than in starved

control cells), while the levels of LC3-II and Beclin-1 were lower

(consistent with the inhibition of autophagy). These results

suggest that NEDD4 may activate autophagy at least in part by

inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway. In other words, NEDD4 acts

upstream to negatively regulate mTOR during autophagy. This finding

aligns with previous findings on the role of mTOR as a negative

regulator of autophagy (30). In

our prior research, it was observed that an increase in osteogenic

differentiation markers in BMSCs was associated with improved

bone-forming capability when autophagy was inhibited (25), suggesting a possible link between

autophagy and osteogenesis. The present study identified NEDD4 as

an upstream regulator of mTOR in BMSCs, offering novel insights

into the molecular mechanisms governing BMSC autophagy and its

potential impact on bone remodeling.

| Figure 6Effects of NEDD4 knockdown on

autophagy markers and mTOR signaling. A representative western blot

image and quantification of LC3-II, Beclin-1, total mTOR, and

p-mTOR in BMSCs under EBSS treatment, with and without NEDD4

knockdown. NEDD4 knockdown reverses EBSS-induced reduction in

p-mTOR, indicating mTOR reactivation. Data are shown as mean ± SD

(n=3). *P≤0.01, **P≤0.005,

***P≤0.0001. Proteins shown within the panel were

detected on the same membrane (cut by molecular weight) unless

otherwise indicated. NEDD4, neural precursor cell-expressed

developmentally down-regulated protein 4; mTOR, mammalian target of

rapamycin; p-, phosphorylated; BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells; EBSS, Earle s balanced salt solution; sh-, short

hairpin; NC, negative control. |

Discussion

The present study investigated the involvement of

NEDD4 in BMSC autophagy. Our experimental findings demonstrated

that NEDD4 is essential for the initiation and maintenance of

autophagy in BMSCs. Through culturing of rat BMSCs, autophagy

induction via starvation, and NEDD4 knockdown experiments, it was

found that NEDD4 significantly influences the expression of

autophagy-related genes and regulates this process through

interactions with the mTOR signaling pathway. The findings offer

novel insights into how NEDD4 and autophagy regulate BMSC

function.

In the present study, autophagy was induced by EBSS

starvation. RT-qPCR and western blot analyses indicated elevated

Beclin-1 and LC3 expression following starvation induction,

suggesting enhanced autophagic activity due to their essential

roles in autophagy (36). Beclin-1

and LC3 expression are typically associated with autophagic

activity. However, an increase in these proteins alone is

insufficient to confirm autophagy, as such changes may reflect the

initiation of autophagy rather than its completion. LC3, Beclin-1,

and p62 are among the most well-known core autophagy proteins

(37). To fully evaluate autophagy,

measuring p62 levels, which typically decrease when autophagic flux

increases, would be informative and p62 will be assessed in future

experiments.

RT-qPCR and western blot analyses also revealed a

marked increase in NEDD4 expression in BMSCs after 30 min of EBSS

starvation-induced autophagy. NEDD4 expression was revealed to be

positively associated with autophagy-related genes LC3 and

Beclin-1, suggesting its role as a positive regulator of autophagy

in BMSCs. NEDD4 is suggested to promote cell survival during stress

(such as nutrient deprivation) by supporting autophagy.

Regarding the starvation duration, various time

points (0-4 h) were assessed and it was found that BMSCs maintained

acceptable viability up to ~30 min of starvation. After 1 h of

starvation, cells exhibited contraction, rounding, and some cell

detachment, with reduced cell density. TEM at 1 h revealed nuclear

shrinkage, fragmentation, and irregular nuclear edges, indicating

that prolonged starvation could initiate apoptotic changes.

Starvation is known to activate autophagy as an adaptive response

to help cells maintain energy balance by degrading and recycling

intracellular components. However, prolonged starvation can trigger

apoptosis. Autophagy and apoptosis, while distinct, have complex

interrelationships that can be synergistic, mutually inhibitory, or

even interconvertible under different conditions (38,39).

Some studies suggest cells can undergo apoptosis and autophagy

simultaneously (40,41). In our experiments, after 15 min of

starvation, autophagy markers had begun to increase (as determined

by RT-qPCR and western blotting) but not to the extent observed at

30 min, indicating that 15 min may have been insufficient for

robust autophagy induction. Based on our comprehensive autophagy

assessments (molecular and ultrastructural), 30 min of EBSS

starvation was selected as the optimal induction duration for

subsequent experiments.

The experiments in the present study showed that

knocking down NEDD4 significantly reduced the expression of LC3 and

Beclin-1 in starved BMSCs. This finding aligns with that of Sun

et al (27), who

demonstrated that stable NEDD4 knockdown in A549 lung cancer cells

inhibited starvation- and rapamycin-induced autophagy, thereby

reducing LC3-II levels. In addition, NEDD4 directly interacted with

LC3. These results indicated that NEDD4 is not only a positive

regulator of autophagy but is also essential for proper execution

of the autophagic process.

A potential mechanism underlying NEDD4-mediated

autophagy, was further investigated. mTOR is a well-established

negative regulator of autophagy, suppressing autophagy under

nutrient-rich conditions (42,43).

Moreover, mTOR is a crucial regulator of osteogenic differentiation

in mesenchymal stem cells such as stem cells from apical papilla,

BMSCs, and periodontal ligament stem cells (44-47).

In the experiments of the present study, EBSS-induced autophagy led

to increased expression of NEDD4 and autophagy-related proteins

(LC3-II and Beclin-1), along with a notable reduction in p-mTOR,

indicating suppressed mTOR activity and enhanced autophagy. When

NEDD4 was knocked down, p-mTOR levels were restored (signifying

reactivation of mTOR), and autophagy (LC3-II and Beclin-1 levels)

was inhibited. This suggests that NEDD4 may activate the autophagy

program by inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway. This

interpretation is consistent with the well-known role of mTOR in

autophagy regulation (30). In our

prior research, it was observed that increased expression of

osteogenic differentiation markers in BMSCs was associated with

improved bone formation capacity (25). Other research indicates a potential

link between suppressed autophagy and enhanced osteogenesis,

although the exact mechanism remains to be explored (48). Thus, the present study identified

NEDD4 as an upstream regulator of mTOR, offering novel insights

into the molecular mechanisms connecting BMSC autophagy and bone

remodeling.

In addition, it is acknowledged that further

mechanistic validation is needed. Only nutrient starvation was

employed to induce autophagy. Using specific autophagy modulators

(such as rapamycin to inhibit mTOR or chloroquine to block

autophagy flux) could strengthen the conclusions. In future

studies, such modulators are planned to be used to further verify

the role of NEDD4. Moreover, the present study design did not

include a ‘rescue’ experiment (restoring NEDD4 expression after

knockdown) to fulfill molecular causation criteria, nor were assays

such as co-immunoprecipitation performed to test for direct

interactions (for example between NEDD4 and components of the mTOR

pathway) or ubiquitination assays conducted to confirm the E3

ligase activity of NEDD4 on autophagy-related substrates. These

experiments are beyond the scope of the present study and will be

addressed in future research. Nevertheless, by combining our

results with previous findings that NEDD4 promotes autophagy in

other cell types (27), compelling

evidence that NEDD4 acts as an upstream regulator of autophagy in

BMSCs is provided. As a further step, ALP staining and

mineralization assays (such as Alizarin Red S staining) could be

employed in future work to directly evaluate how changes in NEDD4

expression or autophagy levels affect the osteogenic

differentiation of BMSCs. These follow-up studies will help clarify

the relationship between autophagy induced by NEDD4 and

osteogenesis.

In summary, the present study revealed an important

role for NEDD4 in regulating autophagy in BMSCs. By establishing

in vitro BMSC models with NEDD4 knockdown, it was

demonstrated that NEDD4 depletion impairs autophagy. The limited

osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs is a key factor in reduced bone

formation; the results of the present study suggest that NEDD4 (via

autophagy activation through mTOR inhibition) could potentially

enhance the osteogenic capacity of BMSCs. This positions NEDD4 as a

promising therapeutic target for conditions such as osteoporosis.

Future studies will further investigate the interplay between

NEDD4-regulated autophagy and BMSC osteogenesis in vivo.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by a grant from the Luzhou

Science and Technology Plan Project (grant no. 2020-JYJ-40), the

Natural Science Foundation of Southwest Medical University (grant

no. 2021ZKMS020), the Tutor Group Capacity Improvement Project of

The Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Southwest Medical

University (grant no. 2022DS16), and the Sichuan College Students

Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (grant no.

S202210632170).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors contributions

CL and FL conceived and designed the study. CL and

XY carried out the methodology design and performed data analysis

using software. SZ and XX conducted the formal analysis. BL was

responsible for data curation and investigation. CL and XY wrote

the original draft. FL and XX reviewed and edited the manuscript.

CL and FL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval for the animal experiments was

granted by the Ethics Committee of Southwest Medical University,

Luzhou, Sichuan, China (approval no. 20221206-005). All animal

procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional

guidelines, the National Research Council s Guide for the Care

and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th ed.), and the AVMA Guidelines

for the Euthanasia of Animals (2020).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Wang L, You X, Zhang L, Zhang C and Zou W:

Mechanical regulation of bone remodeling. Bone Res.

10(16)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Zhang G, Kang Y, Dong J, Shi D, Ziang Y,

Gao H, Lin Z, Wei X, Ding R, Fan B, et al: Fluffy hybrid

nanoadjuvants for reversing the imbalance of osteoclastic and

osteogenic niches in osteoporosis. Bioact Mater. 39:354–374.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Liu F, Yuan L, Li L, Yang J, Liu J, Chen

Y, Zhang J, Lu Y, Yuan Y and Cheng J: S-sulfhydration of SIRT3

combats BMSC senescence and ameliorates osteoporosis via

stabilizing heterochromatic and mitochondrial homeostasis.

Pharmacol Res. 192(106788)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Trompet D, Melis S, Chagin AS and Maes C:

Skeletal stem and progenitor cells in bone development and repair.

J Bone Miner Res. 39:633–654. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Shahnaser S, Sheikhi M, Hashemibeni B,

Mousavi AS and Soltani P: Comparison of autogenous bone graft and

tissue-engineered bone graft in alveolar cleft defects in canine

animal models using digital radiography. Indian J Dent Res.

31:118–123. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Zhang L, Wang P, Mei S, Li C, Cai C and

Ding Y: In vivo alveolar bone regeneration by bone marrow stem

cells/fibrin glue composition. Arch Oral Biol. 57:238–244.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Mizushima N and Komatsu M: Autophagy:

Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 147:728–741. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Mizushima N and Levine B: Autophagy in

human diseases. N Engl J Med. 383:1564–1576. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Klionsky DJ, Petroni G, Amaravadi RK,

Baehrecke EH, Ballabio A, Boya P, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Cadwell K,

Cecconi F, Choi AMK, et al: Autophagy in major human diseases. EMBO

J. 40(e108863)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Amaravadi RK, Kimmelman AC and White E:

Recent insights into the function of autophagy in cancer. Genes

Dev. 30:1913–1930. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Menzies FM, Fleming A and Rubinsztein DC:

Compromised autophagy and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev

Neurosci. 16:345–357. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lavandero S, Chiong M, Rothermel BA and

Hill JA: Autophagy in cardiovascular biology. J Clin Invest.

125:55–64. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Jung HS, Chung KW, Won Kim J, Kim J,

Komatsu M, Tanaka K, Nguyen YH, Kang TM, Yoon KH, Kim JW, et al:

Loss of autophagy diminishes pancreatic beta cell mass and function

with resultant hyperglycemia. Cell Metab. 8:318–324.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Huang J and Brumell JH: Autophagy in

immunity against intracellular bacteria. Curr Top Microbiol

Immunol. 335:189–215. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Su Z, Chen D, Huang J, Liang Z, Ren W,

Zhang Z, Jiang Q, Luo T and Guo L: Isoliquiritin treatment of

osteoporosis by promoting osteogenic differentiation and autophagy

of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Phytother Res. 38:214–230.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Zeng C, Wang S, Chen F, Wang Z, Li J, Xie

Z, Ma M, Wang P, Shen H and Wu Y: Alpinetin alleviates osteoporosis

by promoting osteogenic differentiation in BMSCs by triggering

autophagy via PKA/mTOR/ULK1 signaling. Phytother Res. 37:252–270.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Liu Y, Lin S, Xu Z, Wu Y, Wang G, Yang G,

Cao L, Chang H, Zhou M and Jiang X: High-performance

hydrogel-encapsulated engineered exosomes for supporting

endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis and boosting diabetic bone

regeneration. Adv Sci (Weinh). 11(e2309491)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Wang M, Zhang L, Lin F, Zheng Q, Xu X and

Mei L: Dynamic study into autophagy and apoptosis during

orthodontic tooth movement. Exp Ther Med. 21(430)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Xu HM and Hu F: The role of autophagy and

mitophagy in cancers. Arch Physiol Biochem. 128:281–289.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ceccariglia S, Cargnoni A, Silini AR and

Parolini O: Autophagy: A potential key contributor to the

therapeutic action of mesenchymal stem cells. Autophagy. 16:28–37.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Ingham RJ, Gish G and Pawson T: The Nedd4

family of E3 ubiquitin ligases: Functional diversity within a

common modular architecture. Oncogene. 23:1972–1984.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wiszniak S, Harvey N and Schwarz Q: Cell

autonomous roles of Nedd4 in craniofacial bone formation. Dev Biol.

410:98–107. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Wiszniak S, Kabbara S, Lumb R, Scherer M,

Secker G, Harvey N, Kumar S and Schwarz Q: The ubiquitin ligase

Nedd4 regulates craniofacial development by promoting cranial

neural crest cell survival and stem-cell like properties. Dev Biol.

383:186–200. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Jeon SA, Lee JH, Kim DW and Cho JY:

E3-ubiquitin ligase NEDD4 enhances bone formation by removing

TGFβ1-induced pSMAD1 in immature osteoblast. Bone. 116:248–258.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Li B, Zhang S, Yun X, Liu C, Xiao R, Lu M,

Xu X and Lin F: NEDD4 s effect on osteoblastogenesis potential

of bone mesenchymal stem cells in rats concerned with PI3K/Akt

pathway. Differentiation. 141(100830)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Luo M, Ye L, Chang R, Ye Y, Zhang Z, Liu

C, Li S, Jing Y, Ruan H, Zhang G, et al: Multi-omics

characterization of autophagy-related molecular features for

therapeutic targeting of autophagy. Nat Commun.

13(6345)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Sun A, Wei J, Childress C, Shaw JH IV,

Peng K, Shao G, Yang W and Lin Q: The E3 ubiquitin ligase NEDD4 is

an LC3-interactive protein and regulates autophagy. Autophagy.

13:522–537. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Xie W, Jin S and Cui J: The NEDD4-USP13

axis facilitates autophagy via deubiquitinating PIK3C3. Autophagy.

16:1150–1151. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Xie W, Jin S, Wu Y, Xian H, Tian S, Lie

DA, Guo Z and Cui J: Auto-ubiquitination of NEDD4-1 Recruits USP13

to facilitate autophagy through deubiquitinating VPS34. Cell Rep.

30:2807–2819.e4. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Li Y, Zhang L, Zhou J, Luo S, Huang R,

Zhao C and Diao A: Nedd4 E3 ubiquitin ligase promotes cell

proliferation and autophagy. Cell Prolif. 48:338–347.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Farahzadi R, Fathi E, Mesbah-Namin SA and

Vietor I: Granulocyte differentiation of rat bone marrow resident

C-kit+ hematopoietic stem cells induced by mesenchymal

stem cells could be considered as new option in cell-based therapy.

Regen Ther. 23:94–101. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Mizushima N, Yoshimori T and Levine B:

Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 140:313–326.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Klionsky DJ, Abdel-Aziz AK, Abdelfatah S,

Abdellatif M, Abdoli A, Abel S, Abeliovich H, Abildgaard MH, Abudu

YP, Acevedo-Arozena A, et al: Guidelines for the use and

interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (4th

edition)1. Autophagy. 17:1–382. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Farahzadi R, Valipour B, Anakok OF, Fathi

E and Montazersaheb S: The effects of encapsulation on NK cell

differentiation potency of C-kit-hematopoietic stem cells via

identifying cytokine profiles. Transpl Immunol.

77(101797)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Vicente GP, Della Salda L and Strefezzi

RF: Beclin-1 and LC3B expression in canine mast cell tumours: An

immuno-ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of autophagy.

Vet Q. 44:1–15. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Su S, Wu Y, Wang D and Hai J: Inhibition

of excessive autophagy and mitophagy mediates neuroprotective

effects of URB597 against chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Cell

Death Dis. 9(733)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Biswas U, Roy R, Ghosh S and Chakrabarti

G: The interplay between autophagy and apoptosis: Its implication

in lung cancer and therapeutics. Cancer Lett.

585(216662)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Remadevi V, Jaikumar VS, Vini R,

Krishnendhu B, Azeez JM, Sundaram S and Sreeja S: Urolithin A,

induces apoptosis and autophagy crosstalk in oral squamous cell

carcinoma via mTOR/AKT/ERK1/2 pathway. Phytomedicine.

130(155721)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Zhu Y, Wang H, Wang J, Han S, Zhang Y, Ma

M, Zhu Q, Zhang K and Yin H: Zearalenone Induces apoptosis and

cytoprotective autophagy in chicken granulosa cells by

PI3K-AKT-mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways. Toxins (Basel).

13(199)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Li S, Xu B, Luo Y, Luo J, Huang S and Guo

X: Autophagy and apoptosis in rabies virus replication. Cells.

13(183)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B and Guan KL:

AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of

Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 13:132–141. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhang Y, Vasheghani F, Li YH, Blati M,

Simeone K, Fahmi H, Lussier B, Roughley P, Lagares D, Pelletier JP,

et al: Cartilage-specific deletion of mTOR upregulates autophagy

and protects mice from osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 74:1432–1440.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Chen M, Jing D, Ye R, Yi J and Zhao Z:

PPARβ/δ accelerates bone regeneration in diabetic mellitus by

enhancing AMPK/mTOR pathway-mediated autophagy. Stem Cell Res Ther.

12(566)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Tanaka Y, Sonoda S, Yamaza H, Murata S,

Nishida K, Hama S, Kyumoto-Nakamura Y, Uehara N, Nonaka K, Kukita T

and Yamaza T: Suppression of AKT-mTOR signal pathway enhances

osteogenic/dentinogenic capacity of stem cells from apical papilla.

Stem Cell Res Ther. 9(334)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Zhao X, Sun W, Guo B and Cui L: Circular

RNA BIRC6 depletion promotes osteogenic differentiation of

periodontal ligament stem cells via the miR-543/PTEN/PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway in the inflammatory microenvironment. Stem Cell

Res Ther. 13(417)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Jiang Z, Huang H, Luo L and Jiang B: The

role of autophagy on osteogenesis of dental follicle cells under

inflammatory microenvironment. Oral Dis. 31:928–940.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Zheng J, Gao Y, Lin H, Yuan C and Zhi K:

Corrigendum to ‘Enhanced autophagy suppresses inflammation-mediated

bone loss through ROCK1 signaling in bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells’ [Cells Dev 167 (2021) 203687]. Cells Dev.

176(203867)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|