Introduction

Giant congenital melanocytic nevi (GCMN) are rare

pigmented skin lesions present at birth, often enlarging to 20 cm

in adulthood (1,2). Their development results from an

abnormal migration and proliferation of neural crest-derived

melanoblasts, which may involve not only the skin but also deeper

structures such as leptomeninges (1). Individuals with GCMN face a higher

lifetime risk of malignant melanoma and neurocutaneous melanosis

(1,2). Modern surveillance combines clinical

examination with total body mapping and artificial intelligence

(AI)-assisted dermoscopy. These technologies allow sensitive

detection of morphological changes and objective comparison over

time, thus facilitating early recognition of malignant

transformation (3,4). Alongside imaging, genetic

predisposition strongly influences melanoma risk. The melanocortin

1 receptor (MC1R) gene is central in regulating pigmentation, and

its high-risk variants are well documented as low- to

moderate-penetrance melanoma susceptibility alleles. Identifying

such variants may explain individual nevus burden and guide

tailored follow-up. The aim of the present case report was to

present a patient with a bathing-trunk-type GCMN who underwent

integrative follow-up with AI-enhanced dermoscopy, histopathology,

and germline genetic analysis. The case illustrates how combining

clinical and molecular tools supports personalized surveillance in

high-risk patients (5,6).

Case report

Patient

A 55-year-old woman was referred for dermatologic

evaluation due to a bathing-trunk type GCMN and multiple additional

nevi distributed over the trunk and extremities. The present study

was approved (approval no.755/19.12.2023) by the Ethics Commission

of the Medical University-Pleven, (Pleven Bulgaria). Written

informed consent for participation and publication was obtained

from the patient in the present study.

Dermatological еvaluation

Cutaneous examination was performed with total body

mapping using an AI-assisted dermoscopy system (MoleAnalyzer Pro

version 3.5.6.0; FotoFinder Systems GmbH). The software applies

convolutional neural networks trained on large annotated image

datasets to identify and score melanocytic lesions according to

asymmetry, border, color, and structure. Sequential imaging allows

objective detection of new or evolving lesions.

Germline pathogenic variant

detection

After informed consent, peripheral blood was

collected in EDTA tubes. DNA extraction was performed with the

MagCore® Genomic DNA Whole Blood Kit (cat. no.

MGB400-04; RBC Bioscience Corp.). Genomic DNA integrity was

assessed using an Agilent 2200 TapeStation system with Genomic DNA

ScreenTape (Agilent Technologies, Inc.), following the

manufacturer's instructions. Concentration and purity were

evaluated using the Qubit 4 Fluorometer and NanoDrop One

spectrophotometer (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Genetic analysis was performed with massive parallel

next-generation sequencing (NGS). Library preparation was carried

out using the TruSight One Expanded Panel (6699 genes; Illumina,

Inc.), followed by paired-end sequencing (2x150 bp) on the Illumina

NextSeq 550 High Output Kit v2.5 (300 cycles; cat. no. 20024907;

Illumina Inc.). Bioinformatic processing included alignment to hg19

and generation of gVCF files. The mean sequencing depth across all

targeted regions was 256. Coverage analysis demonstrated that ≥99%

of target regions were covered at ≥20x. Variants were filtered

using custom thresholds: Minimum depth ≥20x, variant allele

frequency (VAF) ≥0.20, exclusion of synonymous variants, and

prioritization of nonsynonymous, splicing, and frameshift changes.

Variant annotation used ClinVar, dbSNP, and Ensembl databases.

Classification followed the ACMG five-tier framework (7).

Histopathology

Excised lesions were fixed in 10% neutral buffered

formalin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 12-24 h at room

temperature, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 3-4 µm. Sections

were stained with hematoxylin and eosin following standard

histopathological procedures. Hematoxylin staining was performed at

room temperature for 4-6 min, followed by eosin staining at room

temperature for 1-2 min. Hematoxylin (Mayer's hematoxylin; Merck

KGaA) and eosin (Eosin Y; Merck KGaA) were used according to the

manufacturer's protocols. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue

sections (4 µm) were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through a

descending ethanol series, and subjected to heat-induced antigen

retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95-98˚C for 20 min.

Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched using 3% hydrogen

peroxide for 10 min, followed by blocking with 5% normal goat serum

(Vector Laboratories, Inc.) for 20 min at room temperature. Primary

antibodies were applied under the following conditions: S100

(1:400; overnight at 4˚C; cat. no. IR504; Dako; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.); SOX10 (1:200; overnight at 4˚C; cat. no.

A-1028, Cell Marque/Merck KGaA); Melan-A (1:100; 1 h at room

temperature; code no. M7196; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.)

Sections were incubated with the EnVision+ System HRP secondary

antibody (cat. no. K4001; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) for 30

min at room temperature, and chromogenic detection was performed

using DAB+ (code no. K3468; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Slides were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin (Merck KGaA) at

room temperature (20-25˚C) for 1-2 min, dehydrated through graded

alcohols, cleared in xylene, and mounted. Immunoreactivity was

evaluated using a bright-field microscope (Olympus BX43; Olympus

Corporation) at a magnification of x100-x400.

Clinical presentation and

histopathological findings

The female patient presented with a large

bathing-trunk-type GCMN, accompanied by over 30 satellite nevi

(0.5-7 cm) across the trunk and limbs. Neurological examinations,

performed due to prior seizure episodes, revealed no structural

abnormalities. In 2023 (at the age of 54 years), three pigmented

tumors (total diameter 28 cm) in the lumbar region were surgically

excised. Histology revealed a multinodular plexiform melanocytic

schwannoma composed of spindle-shaped melanocytes, extending into

subcutaneous tissue, with low mitotic activity.

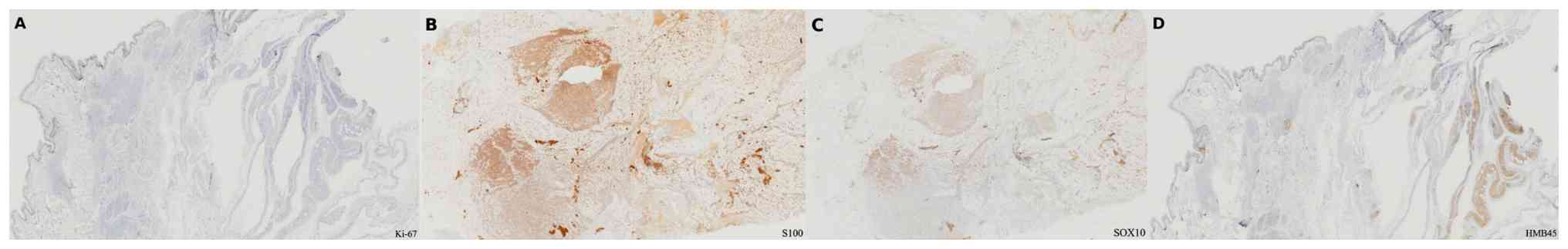

Immunohistochemistry showed diffuse S100 and SOX10 positivity,

focal Melan A expression, and a low Ki-67 index. These markers

supported schwannoma with melanocytic differentiation rather than

malignant melanoma.

Dermatological status

Cutaneous examination revealed extensive pigmentary

changes involving the face, trunk, and both upper and lower

extremities. The findings included a symmetrically distributed

bathing-trunk-type GCMN, accompanied by multiple satellite nevi

ranging from 0.5 to 7 cm in diameter. In the sacral region, a

linear, cross-shaped atrophic scar was noted, consistent with the

site of prior surgical excision. The scar was surrounded by

numerous dark brown to black colored macules. (Fig. 1A-C) The dermatological examination

with a Total body mapping and AI dermoscopy device (MoleAnalyzer

Pro) did not identify melanoma-like evolution. Histopathological

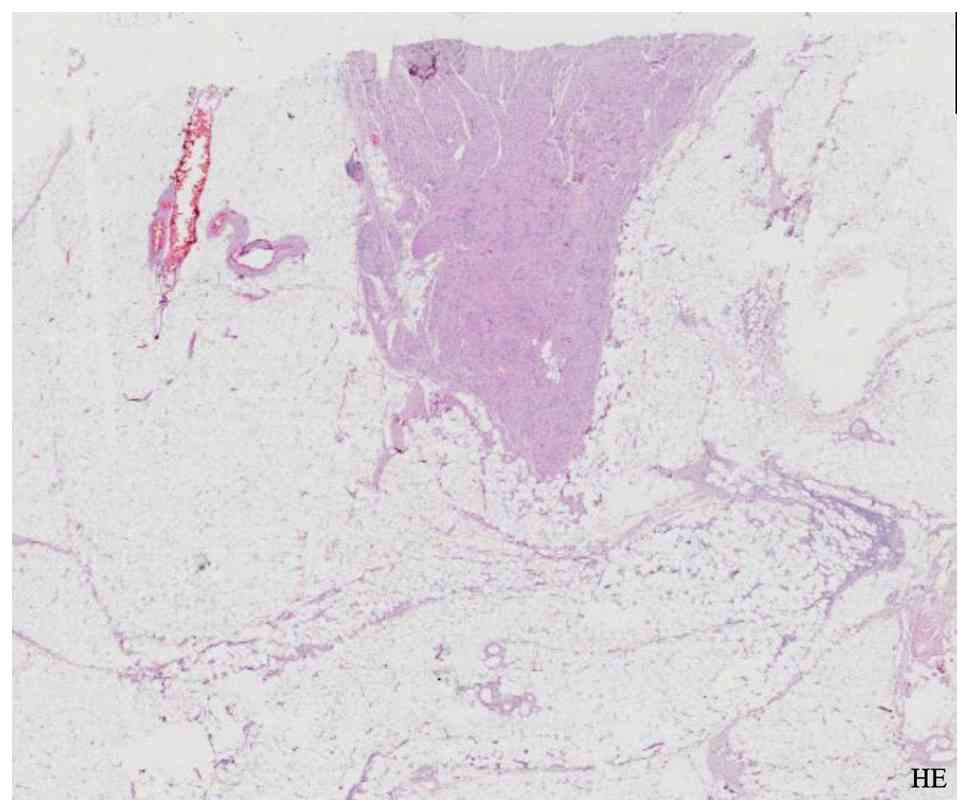

analysis of the excised multinodular, plexiform, non-encapsulated

lesion demonstrated a proliferation of oval and spindle-shaped

cells extending from the epidermis through the dermis and into the

deep subcutaneous adipose tissue, as visualized with hematoxylin

and eosin staining (Fig. 2).

Immunohistochemistry showed diffuse S100 and SOX10 positivity,

focal Melan A expression, and a low Ki-67 index (Fig. 3A-D). These markers supported

schwannoma with melanocytic differentiation rather than malignant

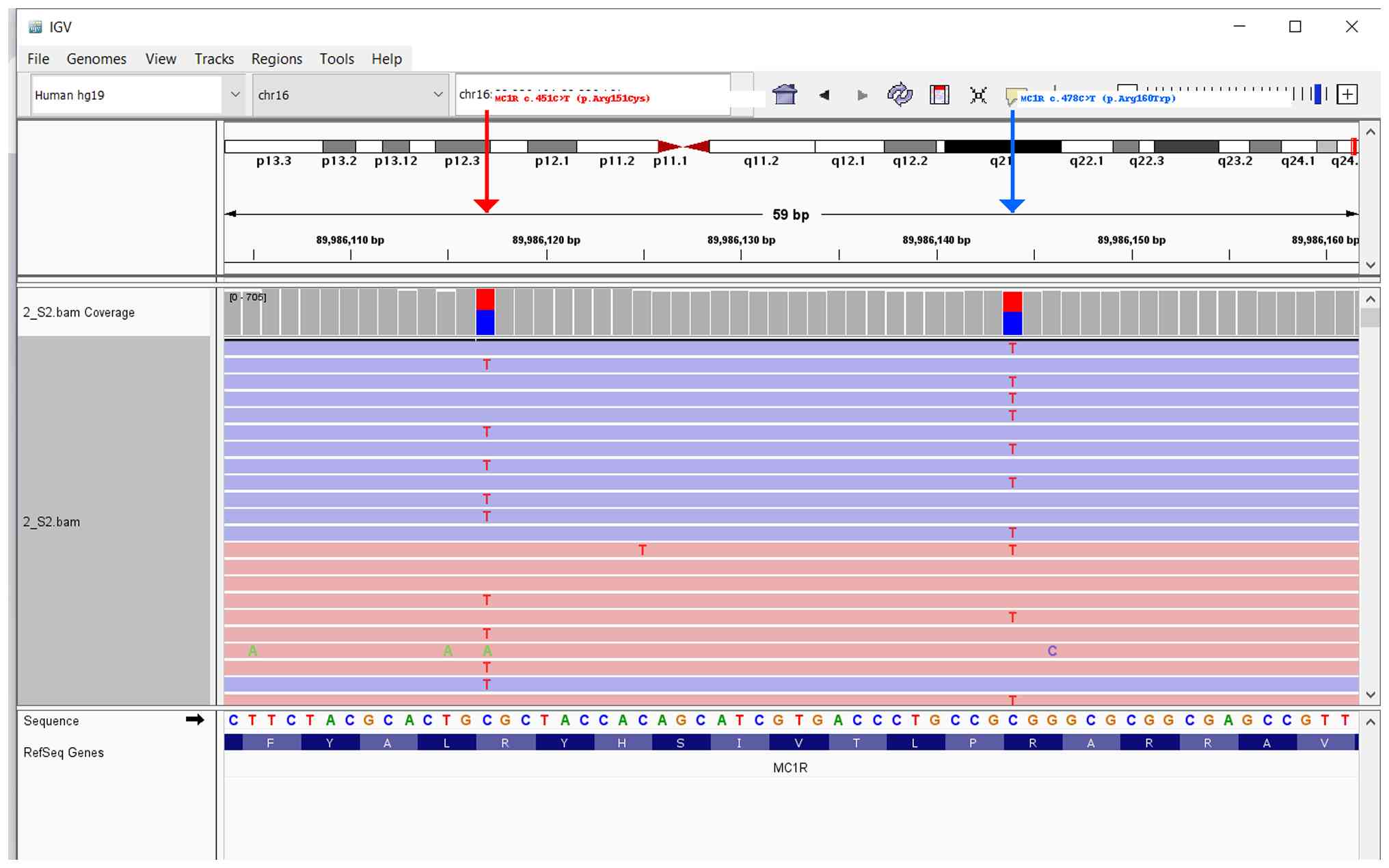

melanoma. NGS analysis identified two pathogenic MC1R variants:

c.451C>T (p.Arg151Cys) and c.478C>T (p.Arg160Trp), both in

compound heterozygous state (Fig.

4). No pathogenic variants were detected in NRAS or BRAF. No

additional high-risk variants were identified across the panel.

Discussion

GCMN represent rare developmental anomalies of

melanoblast migration and proliferation, with a reported melanoma

risk of ~5% over a lifetime (8,9). Early

recognition of malignant transformation is essential. These

developmental abnormalities are frequently linked to somatic

mutations in genes such as NRAS (particularly Q61 variants) and

BRAF (notably V600 mutations), as well as dysregulation of pathways

involving hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (10).

Various classification systems exist for CMN, with

the most widely accepted being that of Kopf et al (11), which categorizes lesions by maximum

diameter: Small (<1.5 cm), medium (1.5-19.9 cm), and large or

giant CMN (>20 cm) . The overall incidence of CMN in neonates

ranges from 0.2 to 2.1%, with a slight female predominance reported

(male-to-female ratios between 1:1.17 and 1:1.4) (12). Data from the Giant Congenital

Melanocytic Nevus Registry at the Federal University of Minas

Gerais, based on patient records between 1999 and 2011, estimated

the lifetime risk of melanoma in individuals with GCMN to be ~5%

(13). Anatomical distribution

patterns showed a predominance on the trunk (68.4%), followed by

the head and neck (17.5%), and the extremities (14.1%) (13).

Total body mapping involves systematic photographic

documentation of the entire skin surface, followed by digital

dermoscopic analysis of selected melanocytic lesions. This approach

facilitates longitudinal comparison, enabling the detection of

subtle morphological changes or the emergence of new lesions over

time (14). In the present case,

total body mapping combined with AI-enhanced dermoscopy was

employed, offering a sensitive and objective method for

surveillance. Regular imaging at 6 to 12-month intervals is

especially beneficial in individuals with GCMN, where early

recognition of malignant transformation is critical.

Surgical management remains a topic of ongoing

discussion. A systematic review by Krengel et al (12), analyzing 49 reported cases of

CMN-associated melanoma, found that in 67% of patients the

malignant transformation occurred within the congenital lesion

itself . Based on such findings, prophylactic surgical excision is

sometimes advocated, particularly in large or atypical nevi. While

the impact of surgery on melanoma risk reduction remains

inconclusive, the procedure often yields aesthetic and functional

improvements, which are important considerations for both patients

and families when deciding on treatment.

The histological diagnosis of plexiform melanocytic

schwannoma required careful differentiation from melanoma. Positive

staining for S100 and SOX10 confirmed Schwann cell origin, while

focal Melan A expression reflected melanocytic differentiation.

Similar immunoprofiles have been reported in rare schwannoma

variants (15). Although an

association between MC1R and schwannomas was not established, the

findings of the present study raise the question whether

pigmentation genes may modulate tumor phenotype, a hypothesis

warranting further investigation. Ranson et al (16) described a case involving a

66-year-old man with a tumor sharing similar histological and

immunophenotypic characteristics, including co-expression of S100,

SOX10, and HMB45, consistent with the findings in the present

case.

Pigmentation traits such as red hair, fair skin,

freckling, and poor tanning capacity have long been recognized as

genetically driven risk factors for both melanoma and

non-melanocytic skin cancers particularly when combined with

environmental exposure to ultraviolet radiation (17). MC1R, a G protein-coupled receptor

expressed in cutaneous melanocytes located in the basal epidermal

layer, plays a central role in regulating pigment production

(18,19). Genetic variation within the MC1R

gene contributes substantially to interindividual differences in

skin phototype and pigmentation phenotype.

MC1R variants are typically categorized into two

groups: Low-penetrance alleles (denoted as ‘r’) and high-penetrance

alleles (‘R’) in relation to their association with red hair color

and melanoma risk (20,21). Common ‘r’ alleles include Val60Leu,

Val92Met, and Arg163Gln, while ‘R’ alleles, such as Asp84Glu,

Arg142His, Arg151Cys, Ile155Thr, Arg160Trp, and Asp294His, are more

strongly associated with phenotypic traits and increased

susceptibility to skin malignancies (20).

In the current case, genetic analysis identified two

high-risk MC1R alleles (Arg151Cys and Arg160Trp), both categorized

as ‘R’ variants. Compound heterozygosity for R alleles is linked to

fair phototype, high nevus count, and increased melanoma

susceptibility. Both variants have been shown to exert

dominant-negative effects by impairing MC1R receptor trafficking

and downstream cAMP signaling (22). This genotype aligns with findings by

van der Poel et al (23),

who demonstrated a positive association between the ‘R/R’ genotype

and increased total nevus count. Consistently, the patient in the

present case had >30 nevi and a large back-located GCMN. Further

supporting this association, a more recent study involving 175

healthy carriers of MC1R variants reported that individuals with

‘R’ alleles tend to develop larger nevi, particularly on the back

and upper limbs. Moreover, their nevi often displayed dermoscopic

features such as visible vascular structures, globules, and

pigmented spots (24). These

features were also observed in the present case, reinforcing the

phenotypic impact of the compound ‘R’ genotype on nevus morphology

and distribution. The limitations of the present case report

include its basis in a single patient, the absence of functional

validation or familial segregation studies, and the analysis of

only germline DNA; somatic alterations in lesional tissue remain

unknown. Despite these limitations, the case illustrated the

integrative value of combining clinical imaging and genomic data.

In conclusion the present case emphasized that personalized

surveillance of patients with GCMN benefits from integration of

AI-assisted dermoscopy, histopathology, and germline genetics. The

compound heterozygous MC1R variants may explain the nevus burden of

the patient and justified intensified follow-up. AI technology

allowed precise, noninvasive monitoring, while histology ruled out

melanoma and guided management. An integrative, multidisciplinary

approach should be considered standard for high-risk GCMN patients,

as it enhances early detection and supports informed clinical

decisions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was financed by the European

Union-NextGenerationEU, through the National Recovery and

Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project no.

BG-RRP-2.004-0003, and supported by Project

BG16RFPR002-1.014-0002-С001, ‘Centre of Competence in Personalized

Medicine, 3D and Telemedicine, Robotic-Assisted and Minimally

Invasive Surgery,’ funded by PRIDST 2021-2027 and co-funded by the

EU.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in ClinVar under accession numbers SUB15686128 and SUB15686145.

Authors' contributions

PV recruited the patients. IY, PV, ZK and SP

collected clinical and biological data. ZK performed the molecular

analysis. PV and IY were responsible for diagnosis and treatment of

the patient. ZK analyzed the data. PV, ZK, SP and IY were involved

in the writing and revision of the manuscript. SP and IY reviewed

and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript. ZK and PV confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved (approval

no.755/19.12.2023) by the Ethics Commission of the Medical

University-Pleven, (Pleven Bulgaria). Written informed consent for

participation was obtained from the patient.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was

obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kinsler VA, O'Hare P, Bulstrode N, Calonje

JE, Chong WK, Hargrave D, Jacques T, Lomas D, Sebire NJ and Slater

O: Melanoma in congenital melanocytic naevi. Br J Dermatol.

176:1131–1143. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Krengel S, Scope A, Dusza SW, Vonthein R

and Marghoob AA: New recommendations for the categorization of

cutaneous features of congenital melanocytic nevi. J Am Acad

Dermatol. 68:441–451. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Marghoob AA, Swindle LD, Moricz CZ,

Sanchez Negron FA, Slue B, Halpern AC and Kopf AW: Instruments and

new technologies for the in vivo diagnosis of melanoma. J Am Acad

Dermatol. 49:777–799. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Haenssle HA, Fink C, Schneiderbauer R,

Toberer F, Buhl T, Blum A, Kalloo A, Hassen ABH, Thomas L, Enk A,

et al: Man against machine: Diagnostic performance of a deep

learning convolutional neural network for dermoscopic melanoma

recognition in comparison to 58 dermatologists. Ann Oncol.

29:1836–1842. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Raimondi S, Sera F, Gandini S, Iodice S,

Caini S, Maisonneuve P and Fargnoli MC: MC1R variants, melanoma and

red hair color phenotype: A meta-analysis. Int J Cancer.

122:2753–2760. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Tagliabue E, Gandini S, Bellocco R,

Maisonneuve P, Newton-Bishop J, Polsky D, Lazovich D, Kanetsky PA,

Ghiorzo P, Gruis NA, et al: MC1R variants as melanoma risk factors

independent of at-risk phenotypic characteristics: a pooled

analysis from the M-SKIP project. Cancer Manag Res. 10:1143–1154.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S,

Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, et al:

Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence

variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American college

of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular

pathology. Genet Med. 17:405–424. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Viana AC, Gontijo B and Bittencourt FV:

Giant congenital melanocytic nevus. An Bras Dermatol. 88:863–878.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Arneja JS and Gosain AK: Giant congenital

melanocytic nevi of the trunk and an algorithm for treatment. J

Craniofac Surg. 16:886–893. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Meshram GG, Kaur N and Hura KS: Giant

congenital melanocytic nevi: An update and emerging therapies. Case

Rep Dermatol. 10:24–28. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kopf AW, Bart RS and Hennessey P:

Congenital nevocytic nevi and malignant melanomas. J Am Acad

Dermatol. 1:123–130. 1979.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Krengel S, Hauschild A and Schäfer T:

Melanoma risk in congenital melanocytic naevi: a systematic review.

Br J Dermatol. 155:1–8. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Viana ACL, Goulart EMA, Gontijo B and

Bittencourt FV: A prospective study of patients with large

congenital melanocytic nevi and the risk of melanoma. An Bras

Dermatol. 92:200–205. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Barcaui C, Bakos RM, Paschoal FM,

Bittencourt FV, de Sá BCS and Miot HA: Total body mapping in the

follow-up of melanocytic lesions: Recommendations of the Brazilian

society of dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 96:472–476.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Torres-Mora J, Dry S, Li X, Binder S, Amin

M and Folpe AL: Malignant melanotic schwannian tumor: a

clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and gene expression

profiling study of 40 cases, with a proposal for the

reclassification of "melanotic schwannoma". Am J Surg Pathol.

38:94–105. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ranson M, Lai J, Van Brenk B, McCalmont TH

and Walsh NM: Plexiform melanocytic schwannoma: Report of a second

case and overview of a rare entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 44:943–947.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Sturm RA: Skin colour and skin

cancer-MC1R, the genetic link. Melanoma Res. 12:405–416.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Cai M and Hruby VJ: The melanocortin

receptor system: A target for multiple degenerative diseases. Curr

Protein Pept Sci. 17:488–96. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Roberts DW, Newton RA, Beaumont KA,

Leonard JH and Sturm RA: Quantitative analysis of MC1R gene

expression in human skin cell cultures. Pigment Cell Res. 19:76–89.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Beaumont KA, Liu YY and Sturm RA: The

melanocortin-1 receptor gene polymorphism and association with

human skin cancer. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 88:85–153.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Pasquali E, García-Borrón JC, Fargnoli MC,

Gandini S, Maisonneuve P, Bagnardi V, Specchia C, Liu F, Kayser M,

Nijsten T, et al: MC1R variants increased the risk of sporadic

cutaneous melanoma in darker-pigmented Caucasians: A

pooled-analysis from the M-SKIP project. Int J Cancer. 136:618–631.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Beaumont KA, Shekar SN, Newton RA, James

MR, Stow JL, Duffy DL and Sturm RA: Receptor function, dominant

negative activity and phenotype correlations for MC1R variant

alleles. Hum Mol Genet. 16:2249–2260. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

van der Poel LAJ, Bergman W, Gruis NA and

Kukutsch NA: The role of MC1R gene variants and phenotypical

features in predicting high nevus count. Melanoma Res. 30:511–514.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Vallone MG, Tell-Marti G, Potrony M,

Rebollo-Morell A, Badenas C, Puig-Butille JA, Gimenez-Xavier P,

Carrera C, Malvehy J and Puig S: Melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R)

polymorphisms' influence on size and dermoscopic features of nevi.

Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 31:39–50. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|