Introduction

Tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC), the most

common oral cancer, demonstrates a strong tendency for cervical

lymph node metastasis, even in the early stages (1). According to current National

Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines (Version 1.2026), standard

treatment for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, including

TSCC, primarily involves surgical resection, with adjuvant

radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for high-risk pathological

features (2). In recent years,

immune checkpoint inhibitors have been incorporated into the

management of very advanced disease (unresectable, recurrent, or

metastatic). Although therapeutic advances have been made, outcomes

remain poor, particularly in patients with advanced or recurrent

disease.

Suramin, a polysulfonated naphthylurea first

developed in 1916 for African trypanosomiasis (3,4), has

been repurposed for oncology due to its ability to block diverse

signaling pathways (TGF-β, bFGF, PDGF, EGF, and VEGF) and cell

cycle regulators (cyclins A2, B1, D1, and E). In addition, it

interferes with the RNA-binding protein HuR, which stabilizes

oncogenic transcripts (5-7).

These pleiotropic actions have renewed the interest

in suramin and its use in hormone-refractory prostate cancer (HRPC)

(8). At low doses, suramin can

function as a chemosensitizer (4),

and nanoparticle formulations combining suramin with doxorubicin

have demonstrated strong efficacy without systemic toxicity in

breast cancer models (9). In TSCC,

suramin suppresses tumor proliferation, migration, and invasion

(7). However, clinical evidence

remains limited, and the mechanisms underlying TSCC remain unclear.

We investigated the effects of suramin on global gene expression in

HSC-3 cells using next-generation sequencing (NGS) and evaluated

its in vivo activity in a luciferase-labeled orthotopic

mouse model to elucidate its therapeutic potential.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, cell culture, suramin

treatment

The human tongue squamous cell carcinoma cell line

HSC-3 (RIKEN, Tsukuba, Japan) and luciferase-expressing HSC-3 cells

(HSC-3-Luc; JCRB Cell Bank, Osaka, Japan) were used. The cells were

maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)

supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were incubated

for 24 h in serum-free DMEM containing 100 µM suramin (FUJIFILM

Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan). Control cells

received an equivalent volume of UltraPure™ distilled water

(Invitrogen; NY, USA), the solvent for suramin. The use of 100 µM

suramin for 24 h was based on our previous report (7), in which this concentration effectively

suppressed HuR-regulated genes, including CCNB1 and

CCNA2, at both the mRNA and protein levels while remaining

non-cytotoxic in HSC-3 cells (IC50=732 µM).

RNA extraction and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit

(Qiagen; Hilden, Germany), and 1 µg of total RNA was used for

downstream processing. The mRNA was enriched with oligo (dT) beads,

fragmented, and reverse-transcribed to generate cDNA. Library

construction and sequencing were performed by Novogene (Beijing,

China) using an Illumina platform.

Bioinformatics analysis

Raw reads were qualitatively checked and aligned to

the human reference genome. Gene expression was quantified using

HTSeq (v0.6.1, union mode) and normalized to fragments per kilobase

of transcript per million mapped reads to enable comparisons

between samples.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were

identified using DEGseq (10) with

TMM normalization under a Poisson distribution model, and defined

as those with |log2 (fold change)| >1 and q<0.005

(Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate). Gene Ontology (GO) and

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses

were performed using g:Profiler (version e113_eg59_p19_f6a03c19;

database updated May 23, 2025). In GO analysis, terms with a size

>1,500 were excluded, and categories with an intersection size

≥3 were retained; for KEGG, terms with a size <300 and an

intersection size ≥3 were applied. Protein-protein interaction

(PPI) networks were generated using STRING (version 12.0) with a

high-confidence interaction threshold (combined score >0.700),

and hub genes were identified by degree centrality. The DEGs were

annotated using AnimalTFDB v4.0, and only sequence-specific

transcription factors (TFs) were retained, excluding chromatin

regulators and cofactors. Candidate transcription factors were

further validated by confirming the binding motifs in JASPAR 2024

and by cross-referencing the binding activity with the ENCODE

ChIP-seq datasets.

Biological replicates were not included, and this

single-sample design limited statistical robustness; therefore,

conservative DEG thresholds were applied to reduce false-positive

findings.

Orthotopic tongue cancer mouse model and

treatments. HSC-3-Luc cells (1x105) suspended in 30

µl of sterile HBSS (without calcium, magnesium, and phenol red;

Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were

orthotopically injected into the left lateral tongue of 8-week-old

male BALB/cAJcl-nu/nu mice using a 27-gauge needle. Day 0 was

defined as the day of tumor implantation. Mice were anesthetized by

intraperitoneal injection with a combination of medetomidine (Orion

Pharma, Espoo, Finland), midazolam (Astellas Pharma, Tokyo, Japan),

and butorphanol (Meiji Seika Pharma, Tokyo, Japan) (MMB) at doses

of 0.6, 3.2, and 4.0 mg/kg, respectively. Because a previously

reported intraperitoneal regimen of 0.75/4/5 mg/kg (11) resulted in deep anesthesia in

preliminary experiments, an 80% reduced dose was employed in the

present study. Because the procedure involved only intralingual

injection, surgical-level deep anesthesia was not required, and

adequate anesthesia was confirmed by the absence of body movement

or facial response to gentle pinching with forceps or needle

puncture of the tongue. The mice were randomized into three groups:

vehicle (n=4), suramin 20 mg/kg (n=5), and suramin 60 mg/kg (n=4),

which were administered intraperitoneally twice weekly.

Tumor

growth was monitored by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) using an IVIS

Spectrum (PerkinElmer) on days 1, 8, 15, 22, 25, and 29 after

intraperitoneal injection of VivoGlo™ Luciferin (150 mg/kg, 200 µl;

Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Tumor growth was assessed on predefined

imaging days (days 1, 8, 15, 22, and 29). An additional imaging

session on day 25 was performed to assess tumor status because

euthanasia was required at that time point. In this orthotopic

tongue cancer model, anesthesia is associated with a risk of upper

airway compromise due to posterior tongue displacement.

Accordingly, in vivo bioluminescence imaging was performed

at the minimum necessary frequency to reduce anesthesia-related

risk. For IVIS imaging, anesthesia was induced and maintained with

2.0% isoflurane. Photon flux was quantified using fixed ROIs under

standardized settings. Longitudinal analysis was restricted to days

1-15, when all mice were alive, and the signals remained within the

linear range, to minimize signal saturation and attrition bias.

Tumor presence was not assessed by any method other than IVIS

during the experimental period because reliable palpation of mouse

tongue tumors was not feasible. Tumor presence was confirmed only

at the final necropsy, as confirmation of tumor mass formation

required dissection. Mice were monitored daily for general health

status and euthanized if body weight loss exceeded 20% or if severe

debilitation occurred. Euthanasia was performed by cervical

dislocation under isoflurane anesthesia on day 29 or earlier, if

the humane endpoints were met, immediately after the final IVIS

imaging while the mice remained anesthetized, and death was

confirmed by the sustained absence of respiration and heartbeat.

The cervical lymph nodes and lungs were harvested at necropsy,

immersed in luciferin, and subjected to ex vivo BLI to

detect metastases.

Tissues showing detectable ex vivo BLI

signals were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in

paraffin, and histologically examined to confirm the presence of

metastatic SCC. Lymph nodes and lungs without detectable ex

vivo BLI signals were not systematically examined. Because

necropsies were performed at different time points owing to

attrition, ex vivo metastasis measurements could not be

temporally matched across animals. Metastasis was defined as a

radiance value ≥3.0-fold above the background in the same animal,

together with a discrete focal bioluminescence signal exhibiting a

smooth intensity gradient.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD with individual

values. Enrichment analyses were considered significant at adjusted

q<0.05 (Benjamini-Hochberg correction). A two-way mixed-effects

model (REML with Geisser-Greenhouse correction) was used to

evaluate the group, time, and interaction effects. Effect sizes

were quantified as partial eta squared (partial η2), and

statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. All analyses

were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.

Results

Suramin-induced transcriptomic

alterations revealed by RNA-sequencing

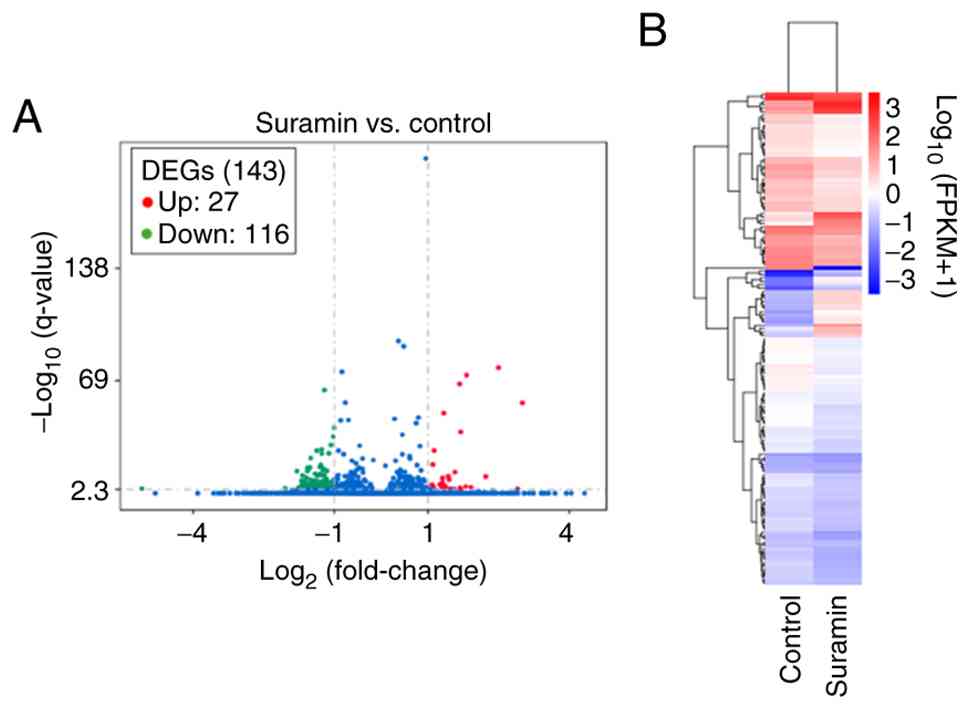

RNA-sequencing detected 60,448 genes, of which

12,114 were commonly expressed in both groups. Differential

expression analysis identified 116 downregulated and 27 upregulated

genes in suramin-treated cells (Fig.

1A), and cluster analysis showed distinct expression patterns

(Fig. 1B). Downregulated genes were

dominated by regulators of the G2/M transition and

mitotic progression (e.g., CCNB1, CDC20,

AURKA), kinetochore and spindle assembly (e.g.,

CENPF, TPX, TUBB), DNA metabolism (RRM2

and TK1), chromatin regulation (DNMT1), cytokinesis

(ANLN), chromosome segregation (MKI67 and

TOP2A), nuclear envelope integrity (LMNB1/2), DNA

damage response (HMGB1/2 and PCNA), and metabolic

regulators (LDHA and PSAT1) were broadly suppressed

(Table I).

| Table ITop 30 downregulated genes identified

by mRNA-sequencing in suramin-treated HSC-3 cells. |

Table I

Top 30 downregulated genes identified

by mRNA-sequencing in suramin-treated HSC-3 cells.

| Rank | Gene symbol | Known function | Fold change | q-value |

|---|

| 1 | TUBB | Microtubule

component | 0.43 |

4.61x10-64 |

| 2 | LDHA | Glycolysis, lactate

production, Warburg effect | 0.50 |

5.32x10-41 |

| 3 | EIF5A | Translation

elongation, mRNA turnover | 0.49 |

1.85x10-35 |

| 4 | HMGB1 | Chromatin

remodeling, DAMPs | 0.48 |

2.30x10-30 |

| 5 | TUBB4B | Microtubule

assembly | 0.42 |

1.42x10-27 |

| 6 | LMNB2 | Nuclear lamina

component | 0.39 |

7.51x10-27 |

| 7 | TOP2A | DNA topology,

mitotic chromosome condensation | 0.46 |

3.31x10-25 |

| 8 | MKI67 | Chromatin

organization, cell proliferation | 0.42 |

4.51x10-25 |

| 9 | UBE2S | Ubiquitination,

mitotic progression | 0.35 |

2.29x10-22 |

| 10 | TUBA1C | Microtubule

assembly | 0.41 |

3.88x10-18 |

| 11 | KPNA2 | Nuclear import | 0.40 |

6.47x10-17 |

| 12 | CCNB1 | G2/M

transition | 0.35 |

1.43x10-16 |

| 13 | CDC20 | Anaphase-promoting

complex activator | 0.34 |

2.30x10-16 |

| 14 | HMGB2 | Chromatin

remodeling, | 0.42 |

6.15x10-16 |

| 15 | RRM2 | dNTP synthesis, DNA

replication | 0.34 |

1.59x10-15 |

| 16 | RANBP1 | Nucleocytoplasmic

transport | 0.42 |

5.75x10-15 |

| 17 | DNMT1 | DNA methylation

maintenance | 0.45 |

1.43x10-14 |

| 18 | TK1 | dTTP synthesis, DNA

replication | 0.34 |

1.96x10-14 |

| 19 | TUBA1B | Microtubule

assembly | 0.29 |

2.16x10-14 |

| 20 | ANLN | Cytokinesis, actin

cytoskeleton regulation | 0.38 |

1.03x10-12 |

| 21 | TCOF1 | rRNA

processing | 0.40 |

1.32x10-12 |

| 22 | LMNB1 | Nuclear lamina

structure | 0.40 |

6.85x10-12 |

| 23 | CENPF | Kinetochore

function, chromosome segregation | 0.43 |

6.95x10-12 |

| 24 | TPX2 | Spindle assembly,

microtubule nucleation | 0.42 |

8.74x10-12 |

| 25 | PSAT1 | Serine

biosynthesis | 0.31 |

1.19x10-11 |

| 26 | CKS1B | CDK regulation,

cell cycle | 0.39 |

1.96x10-11 |

| 27 | AURKA | Mitotic spindle,

centrosome maturation | 0.33 |

3.28x10-10 |

| 28 | PCNA | DNA replication and

repair | 0.45 |

1.65x10-9 |

| 29 | HNRNPAB | Pre-mRNA

processing, mRNA transport | 0.49 |

6.15x10-9 |

| 30 | CKS2 | CDK regulation,

cell cycle progression | 0.35 |

6.31x10-9 |

In contrast, the upregulated genes encoded several

matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) with their inhibitor TIMP3,

stress-response genes (TXNIP and TP53INP1),

pro-apoptotic ligand TNFSF10 (TRAIL), and immune-related

regulators such as PIK3IP1 and FYB (Table II).

| Table IIThe 27 upregulated genes identified

by mRNA-sequencing in suramin-treated HSC-3 cells. |

Table II

The 27 upregulated genes identified

by mRNA-sequencing in suramin-treated HSC-3 cells.

| Rank | Gene symbol | Known function | Fold change | q-value |

|---|

| 1 | MMP10 | ECM

degradation | 5.63 |

1.16x10-77 |

| 2 | MMP1 | ECM degradation,

invasion | 3.52 |

3.18x10-73 |

| 3 | CLU | Apoptosis

modulation, extracellular chaperone | 3.17 |

9.02x10-68 |

| 4 | MMP13 | ECM degradation,

collagen degradation | 8.02 |

3.43x10-56 |

| 5 | TXNIP | Oxidative stress

response, redo regulation | 2.52 |

6.30x10-50 |

| 6 | CLDN1 | Tight junctions,

epithelial barrier | 3.22 |

2.25x10-38 |

| 7 | GLUL | Metabolic

adaptation, glutamine synthesis | 2.18 |

7.04x10-27 |

| 8 | MT2A | Metal ion

homeostasis, oxidative stress response | 2.14 |

2.62x10-18 |

| 9 | CYBRD1 | Iron metabolism,

ferric reductase activity | 2.96 |

9.73x10-14 |

| 10 | CCDC80 | Cell adhesion,

matrix assembly | 2.68 |

3.69x10-11 |

| 11 | MMP12 | ECM degradation,

elastin remodeling | 4.67 |

5.89x10-11 |

| 12 | TIMP3 | MMP inhibition, ECM

stabilization | 2.47 |

4.20x10-10 |

| 13 | FBXO32 | E3 ligase, protein

degradation | 2.71 |

3.74x10-9 |

| 14 | PTGES | PGE2

synthesis, inflammatory response | 2.47 |

2.96x10-7 |

| 15 | PIK3IP1 | Negative regulator

of PI3K | 2.37 |

3.38x10-6 |

| 16 | PLEKHA6 | PH

domain-containing protein | 2.12 |

5.33x10-6 |

| 17 | DHRS3 | Retinal to retinol

reduction | 2.57 |

4.47x10-5 |

| 18 | FYB | T-cell signaling

adaptor | 3.48 |

7.23x10-5 |

| 19 | TNFSF10 | Apoptosis

induction | 2.15 |

8.09x10-5 |

| 20 |

TP53INP1 | Stress-induced

apoptosis | 3.76 |

1.87x10-4 |

| 21 | KLHL24 | BCR E3 ligase

complex | 2.44 |

1.88x10-4 |

| 22 | NATD1 | Acetyltransferase

domain-containing protein | 2.58 |

2.14x10-4 |

| 23 | MMP3 | ECM

degradation | 3.19 |

3.75x10-4 |

| 24 | MT1E | Heavy metal

binding | 2.77 |

1.37x10-3 |

| 25 | TG | Substrate for

thyroid hormone synthesis | 3.22 |

1.66x10-3 |

| 26 | CTSF | Intracellular

degradation, turnover of proteins | 7.46 |

1.78x10-3 |

| 27 | ITGB8 | RGD

recognition | 2.94 |

2.32x10-3 |

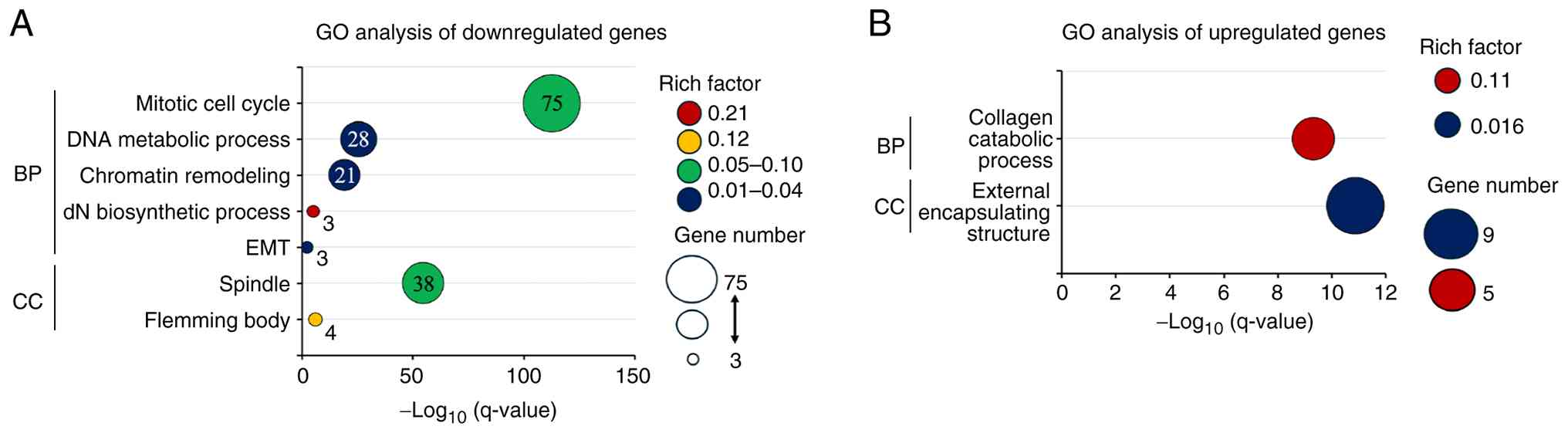

GO enrichment analysis

GO enrichment analysis of the downregulated gene set

demonstrated significant overrepresentation of mitosis-related

pathways, including the mitotic cell cycle, DNA metabolic process,

chromatin remodeling, and deoxyribonucleotide biosynthetic process,

indicating the coordinated downregulation of genes governing

G2/M progression, DNA replication/repair, and chromatin

regulation (Fig. 2A). In contrast,

the upregulated genes were enriched in extracellular matrix-related

processes, such as collagen catabolism, consistent with the

activation of ECM remodeling (Fig.

2B).

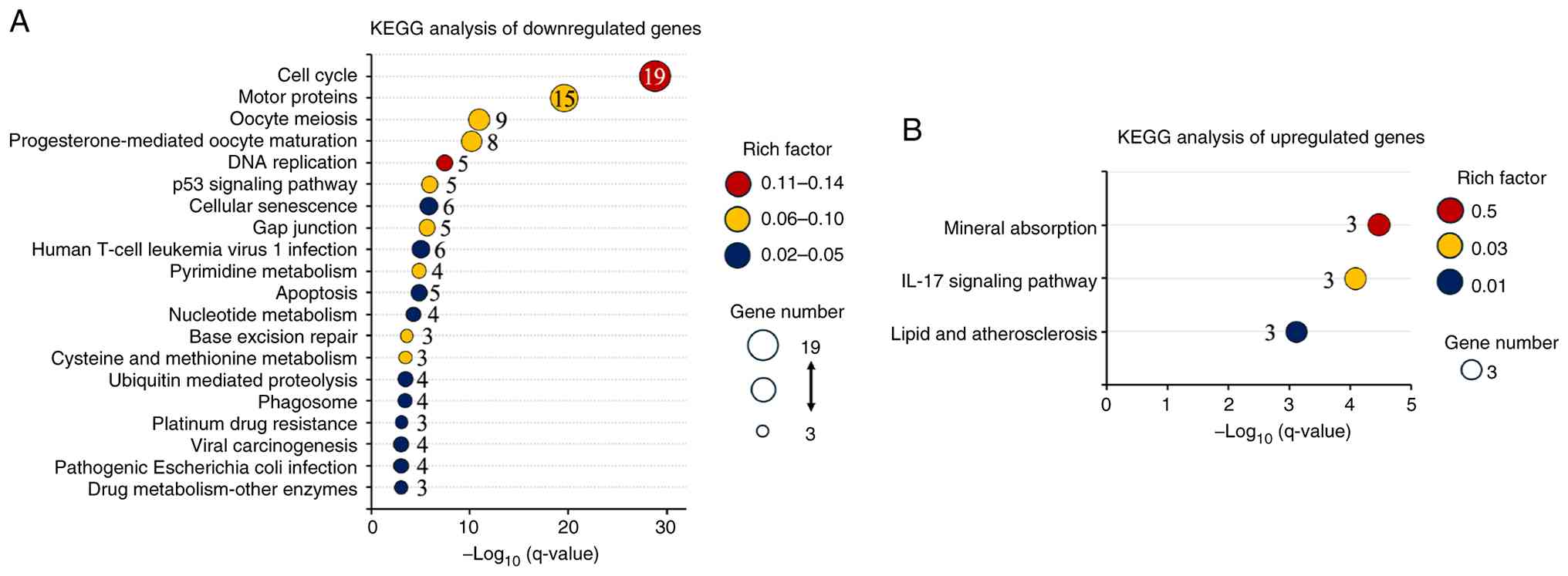

KEGG analysis of differentially

expressed genes

The KEGG pathway analysis demonstrated significant

enrichment of pathways central to cell proliferation and genome

stability in the downregulated gene set. The cell cycle was most

prominently enriched, with associated terms involving

G2/M transition, spindle assembly, and checkpoint

regulation. Additional enrichment in DNA replication, p53

signaling, and base excision repair supports the notion of impaired

genome maintenance. Enrichment of cellular senescence,

ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, and apoptosis further indicated

perturbation of protein turnover and checkpoint surveillance

(Fig. 3A). In contrast, the

upregulated genes were enriched in only three pathways, mineral

absorption, IL-17 signaling, and lipid and atherosclerosis,

suggesting adaptive changes in metal ion homeostasis, immune

modulation, and lipid metabolism (Fig.

3B).

Protein-protein interaction network

analysis

The PPI network of downregulated genes formed a

densely interconnected module dominated by cell cycle and mitotic

regulators. Hub genes included CDK1, CCNA2,

CCNB1, TOP2A, CDC20, KIF11,

KIF20A, BUB1, PLK1, AURKB, TPX2,

and CENPF, all of which are central to the G2/M

transition, spindle function, and chromosome segregation (Table III).

| Table IIITop 30 downregulated and upregulated

genes based on degree centrality in the PPI network. |

Table III

Top 30 downregulated and upregulated

genes based on degree centrality in the PPI network.

| A, Downregulated

genes |

|---|

| Rank | Gene symbol | Degree |

|---|

| 1 | CDK1 | 77 |

| 2 | CCNA2 | 71 |

| 3 | CCNB1 | 70 |

| 4 | TOP2A | 69 |

| 5 | CDC20 | 67 |

| 6 | KIF11 | 67 |

| 7 | KIF20A | 66 |

| 8 | BUB1 | 66 |

| 9 | PLK1 | 65 |

| 10 | DLGAP5 | 64 |

| 11 | AURKB | 63 |

| 12 | BUB1B | 62 |

| 13 | TPX2 | 62 |

| 14 | CCNB2 | 61 |

| 15 | BIRC5 | 61 |

| 16 | KIF2C | 61 |

| 17 | AURKA | 60 |

| 18 | KIF4A | 60 |

| 19 | CDCA8 | 60 |

| 20 | CENPF | 59 |

| 21 | UBE2C | 59 |

| 22 | ASPM | 59 |

| 23 | KIF23 | 57 |

| 24 | NUSAP1 | 57 |

| 25 | CEP55 | 56 |

| 26 | MELK | 56 |

| 27 | CENPA | 55 |

| 28 | PBK | 55 |

| 29 | NCAPG | 54 |

| 30 | RRM2 | 54 |

| B, Upregulated

genes |

| Rank | Gene symbol | Degree |

| 1 | MMP3 | 4 |

| 2 | MMP1 | 3 |

| 3 | TIMP3 | 3 |

| 4 | MMP10 | 2 |

| 5 | MMP12 | 1 |

| 6 | MMP13 | 1 |

| 7 | MT1E | 1 |

| 8 | MT2A | 1 |

In contrast, the network of upregulated genes was

sparse, but revealed coherent submodules. Notably, MMPs, together

with their inhibitor TIMP3, highlighted extracellular matrix

remodeling, whereas MT1E and MT2A played roles in

metal ion homeostasis and oxidative stress responses (Table III).

Transcription factor analysis

TFs were identified among the differentially

expressed genes FOXM1, MYBL2, and TCF19. All

three were significantly downregulated (FOXM1,

FDR=5.01x10-6, log2FC=-1.27; MYBL2,

FDR=1.58x10-5, log2FC=-1.65; TCF19,

FDR=1.71x10-5, log2FC=-1.53). Binding motifs

for FOXM1 and MYBL2 were validated in JASPAR 2024,

and their binding activity was further supported by ENCODE ChIP-seq

datasets. In contrast, TCF19 lacked motif evidence and

demonstrated only limited ChIP-seq support. Therefore, it was

regarded as putative in this context.

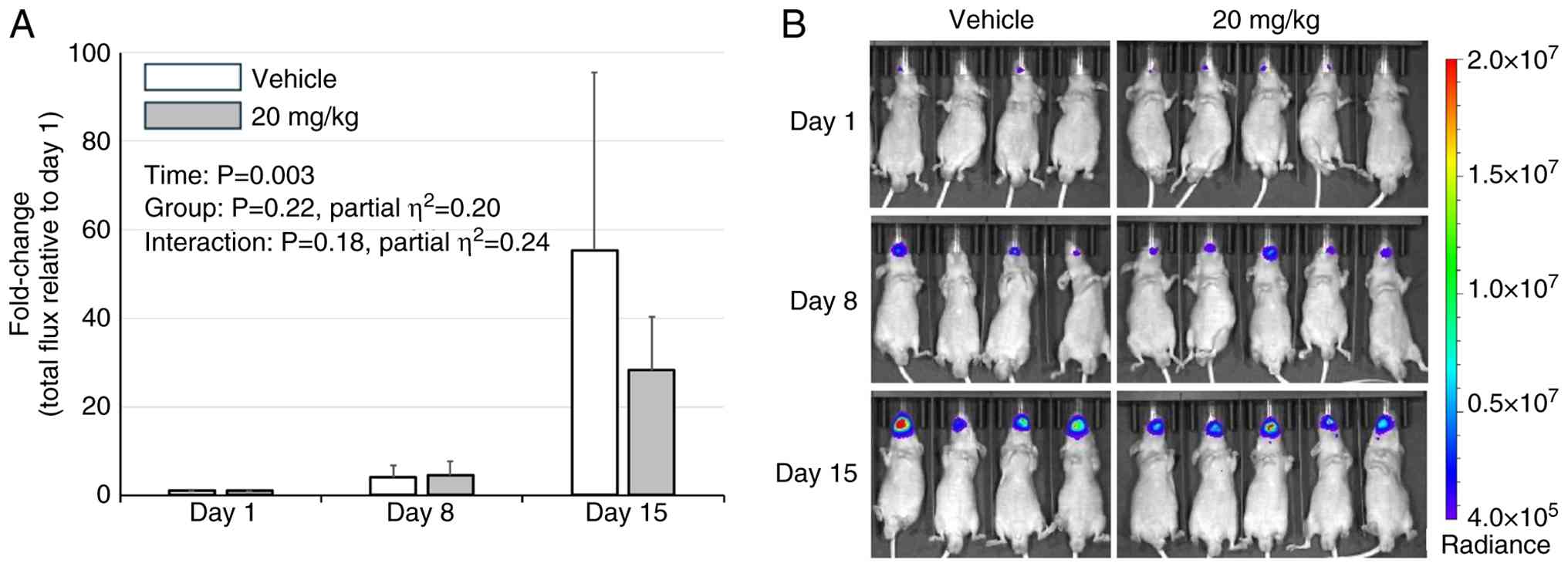

Effects of suramin treatment in an

orthotopic tongue cancer mouse model

Although five mice per group were initially

enrolled, early accidental deaths resulted in four mice in the

vehicle group and five in the 20 mg/kg group available for

longitudinal analyses. Body weights were measured during IVIS

imaging and suramin administration. Mice were regularly monitored,

and euthanasia was performed at humane endpoints (>20% body

weight loss with progressive debilitation due to tumor burden).

Accordingly, analyses were restricted to day 15, when all the mice

remained alive, and the BLI signals were within the linear

detection range. Although BLI values were lower in the suramin 20

mg/kg group than in the vehicle group at this time point, the

mixed-effects model did not detect a significant group effect

(P=0.22), or a significant time x group interaction (P=0.18).

Effect size estimates were relatively large for both the group

effect (partial η2=0.20) and the time x group

interaction (partial η2=0.24), but were insufficient to

establish a clear inhibitory effect of suramin (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast, tumor growth in the

suramin 60 mg/kg group was comparable to that in the vehicle group,

and no difference was detected (Fig.

S1A and B). Further studies

with larger cohorts are necessary to determine whether suramin

exerts a measurable influence on tumor progression. Data collected

after day 15 were excluded from the quantitative analysis owing to

signal saturation and attrition. Lymph node metastases were

detected in the 60 mg/kg (day 22), 20 mg/kg (day 25), and vehicle

groups (two cases on day 29). Pulmonary metastasis was detected in

one vehicle-treated group on day 29. Because necropsies were

performed at different time points, the timing and frequency of

metastases could not be statistically evaluated. The final

confirmation of metastasis was based on ex vivo BLI during

necropsy. The mixed-effects model up to day 22 demonstrated a

significant main effect of time (P=0.0006), whereas neither the

group effect (P=0.16) nor the time x group interaction (P=0.36) was

significant. Although statistical group differences were not

demonstrated, the 60 mg/kg group began to show a marked decline

from day 18, and one mouse died by day 21, supporting clear

systemic toxicity at a high dose (Fig.

S2). Ex vivo BLI confirmed the metastatic involvement of

the cervical lymph nodes and lungs. The corresponding radiance

values and images are provided in Table SI and Fig. S3. In the 20 mg/kg group, metastasis

was not counted in mouse #5 because the lung signal lacked a smooth

intensity gradient and was judged as background rather than a

discrete metastatic focus based on the predetermined imaging

criteria (Fig. S3).

Discussion

Transcriptomic reprogramming induced by suramin in

TSCC cells highlights a dual antitumor mechanism: suppression of

proliferative networks and modulation of the tumor

microenvironment. On the proliferative side, broad downregulation

of genes essential for the G2/M transition (e.g.,

CCNB1, CDC20, AURKA) and spindle assembly

(e.g., TPX2, TUBA1C, TUBB4B) indicates

impaired mitotic entry, chromosome segregation, and spindle

formation. This aligns with previous findings that suramin induces

G2/M arrest in breast cancer cells (12), suggesting a conserved mechanism of

cell cycle inhibition across different malignancies.

Our previous study demonstrated that suramin reduces

the HuR-mediated stabilization of CCNB1 and CCNA2

(7). Although CCNA2 was not

listed among the top 30 downregulated genes, it ranked 55th among

116 downregulated genes. In addition, other HuR-stabilized

transcripts, such as HMGB1, RRM2, and DNMT1, reported

in previous studies, were also downregulated in the present dataset

(13-15).

This concordance between known HuR-dependent transcripts and the

current RNA-seq results supports HuR inhibition as a contributing

mechanism.

In parallel, suramin reprogrammed transcriptional

pathways related to extracellular matrix remodeling. Upregulation

of several MMPs, together with TIMP3, may indicate a more

regulated ECM-associated transcriptional program, distinct from the

unchecked MMP/TIMP imbalance typical of aggressive tumors (16-18).

The co-upregulation of MMP9, MMP11, and MMP14

with TIMP3 has been regarded as a failed compensatory

response in advanced ovarian cancer (19), whereas in cartilage models, suramin

suppresses MMP13 while inducing TIMP3, exerting

protective ECM effects (20,21).

Taken together, these observations indicate that suramin is

consistent with a balanced ECM remodeling-related transcriptional

program in TSCC. However, the functional consequences of this

MMP/TIMP3 pattern were not evaluated in this exploratory

study, and this interpretation should, therefore, be regarded as

tentative.

Suramin also enhances the stress- and

immune-adaptive pathways. Upregulation of TXNIP,

MT1E, and MT2A indicates reinforcement of oxidative

stress responses; TXNIP promotes oxidative stress and

apoptosis (22), MT2A

protects against oxidative injury (23), and MT1E, which is often

silenced in cancers such as HCC (24,25),

was re-induced, consistent with tumor-suppressive reprogramming.

Pro-apoptotic mediators (TNFSF10 and TP53INP1)

(26,27), the PI3K pathway inhibitor

PIK3IP1 (28,29), and the immune adaptor FYB

(30) were also upregulated,

suggesting broad modulation of apoptosis and immune-related

processes.

Our PPI network analysis supported this dual

reprogramming: a densely connected mitotic module was suppressed,

whereas smaller yet coherent subnetworks related to ECM remodeling

and stress responses were activated, consistent with the modular

reorganization reported in cancer systems biology (31).

Importantly, transcription factor analysis revealed

the concurrent downregulation of MYBL2, which cooperates

with the DREAM complex to initiate late S/G2 transcription, and

FOXM1, the master regulator of G2/M progression

(32). TCF19, another

repressed factor, promotes β-cell stress survival partly through

FOXM1 regulation (33) and

promotes proliferation and tumor formation in lung carcinoma by

activating the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway (34). Thus, the suramin-mediated

suppression of TCF19 may synergize with

MYBL2/FOXM1 repression, reinforcing the collapse of

mitotic transcriptional programs and contributing to anti-invasive

reprogramming. Taken together, these findings support a dual

mechanism of action: profound suppression of mitotic progression

and regulation of the tumor microenvironment (35).

Multiple studies have reported diverse suramin

dosing regimens and antitumor effects, reflecting its dual role as

a direct cytotoxic agent at high doses and as a chemosensitizer at

low exposures. In preclinical models, high-dose monotherapy (~60

mg/kg per injection) suppressed tumor growth, including in human

osteosarcoma xenografts (36). In

contrast, lower-dose schedules (5-10 mg/kg, twice weekly) are

commonly employed to enhance the efficacy of paclitaxel, docetaxel,

doxorubicin, and cisplatin with minimal added toxicity (37,38).

In our orthotopic TSCC model, suramin administered

at 20 mg/kg twice weekly reduced tumor growth, although statistical

significance (P=0.18) was not achieved because of the limited

cohort size; the effect size was relatively large (partial

η2=0.24). This dosing range was selected based on

previous reports indicating that the intraperitoneal administration

of up to 60 mg/kg in mice yielded pharmacologically active systemic

exposure, although plasma suramin levels were not measured in this

study. This finding is broadly consistent with previous reports of

in vivo activity, including significant growth inhibition of

DU145 prostate cancer xenografts with suramin monotherapy at

effective doses (39) and enhanced

inhibition of ovarian cancer xenografts when combined with

cisplatin (38). Furthermore,

previous in vitro studies, including our own report

(7), have demonstrated that suramin

suppresses the proliferation and invasion of oral squamous cell

carcinoma cells, including our own report (7), supporting the notion that suramin

exerts multifaceted antitumor effects in oral cancer. When

contextualized using body surface-area scaling (40), the 20 and 60 mg/kg doses in mice

fell within the clinically explored dosing range; however, such a

conversion provides only a theoretical estimate and does not

predict plasma exposure or toxicity. However, in our model, the 60

mg/kg regimen was associated with more pronounced adverse effects

than the 20 mg/kg regimen. This was accompanied by marked body

weight loss, indicating high toxicity at this dose. At excessively

high doses, further increases in antitumor efficacy may not

necessarily occur, and several angiogenesis- and immune-related

anticancer agents have been reported to exhibit non-linear

dose-response relationships in which the therapeutic benefit

plateaus or declines beyond an optimal window (41). Although this phenomenon has not been

established for suramin, the substantial toxicity observed at 60

mg/kg in our model raises the possibility that excessively high

exposure may limit the therapeutic benefits. The assessment of

metastasis was limited because the mouse numbers declined as early

as day 21 in the 60 mg/kg group and from day 23 in the 20 mg/kg and

vehicle groups. Because lymph node metastases typically appeared

after day 25, a reliable evaluation would require a larger number

of mice to ensure sufficient survival in the later phase of tumor

progression. Ex vivo BLI findings of lymph nodes and lungs

are presented in the supplementary data for completeness; however,

differences in necropsy timing prevent quantitative comparison of

the metastatic burden.

Suramin dosing is clinically guided by a nomogram.

Regimens targeting non-cytotoxic plasma concentrations (10-50 µM

for ≥48 h) were primarily applied in combination chemotherapy

trials, where suramin enhanced the effects of agents such as

paclitaxel and carboplatin (42).

In contrast, a large randomized Phase III trial in HRPC employed

dosing schedules designed to maintain plasma concentrations within

the range of 100-300 µg/ml together with hydrocortisone (8). This approach produced a modest

symptomatic benefit but no survival advantage, and the overall

incidence of severe adverse events, including neurotoxicity, was

relatively low owing to careful pharmacokinetic control (8). Earlier studies, however, demonstrated

that when plasma concentrations exceeded 350 µg/ml, the risk of

dose-limiting neurotoxicity increased substantially (43). A more recent clinical

pharmacokinetic study reported that a single 20 mg/kg infusion in

humans produced peak plasma concentrations close to this level

(Cmax=328 µg/ml), without exceeding the upper boundary

of the recommended therapeutic window (44). Collectively, these results suggest

that suramin is unlikely to be effective as a single agent but may

have substantial value as a chemosensitizer in rational combination

regimens. This finding warrants further validation in larger

preclinical cohorts.

Suramin also exhibits anti-inflammatory activity in

addition to its antitumor effects. In a DNCB-induced atopic

dermatitis mouse model, intraperitoneal administration at 20 mg/kg

twice weekly for 3 weeks significantly reduced serum IL-6, IL-1β,

TNF-α, and IgE, improving dermatitis scores (45). These effects are plausibly linked to

the blockade of HMGB1/HMGB2 signaling, as suramin's broad

polyanionic interactions can neutralize cationic DAMPs, such as

HMGB1 and extracellular histones, providing a mechanistic rationale

for its dual anti-inflammatory and antitumor activities.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that suramin

exerts a dual antitumor effect in TSCC by suppressing proliferative

regulators such as MYBL2, FOXM1, and TCF19,

thereby impairing the G2/M transition, while activating

pathways associated with ECM remodeling and stress responses. In

our orthotopic TSCC model, 20 mg/kg suramin reduced tumor growth

compared to controls without achieving statistical significance;

however, the relatively large effect size highlights suramin as a

promising candidate for further translational investigation.

This study is exploratory, relying on single-sample

transcriptomics and a small in vivo cohort. The in

vivo analysis was limited to day 15 due to signal saturation

and attrition, which precluded the evaluation of longer-term

effects. Functional validation of key findings-including

G2/M arrest, FOXM1/MYBL2 activity, and the

MMP/TIMP3 profile-was not performed. Accordingly, the

present findings should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating and

require validation in larger, adequately powered studies. In

addition, systematic toxicity scoring was not performed, limiting

quantitative evaluation of dose-related tolerability, and hub genes

identified by the PPI network were not validated at the protein

level by western blotting. Future studies using ChIP-qPCR to

directly assess FOXM1/MYBL2 binding to target gene promoters, as

well as validation in additional TSCC and HNSCC cell lines, will be

required to determine whether the observed transcriptomic changes

are not cell-line-specific.

Supplementary Material

In vivo effects of suramin on

tumor growth in an orthotopic tongue squamous cell carcinoma model.

(A) BLI signals in the vehicle-, 20 and 60 mg/kg-treated groups are

shown, but the difference was not statistically significant. (B)

In vivo bioluminescence images of orthotopic HSC-3-Luc

tumors in vehicle and suramin (20 and 60 mg/kg) groups.

Longitudinal body-weight changes

during treatment. Body weight (mean ± SD) is shown for the vehicle,

suramin 20 mg/kg, and suramin 60 mg/kg groups. Body weight was

plotted over the entire observation period, and the number of

surviving animals at each time point is shown below the graph. No

statistically significant differences in the mean body weight were

detected between the groups.

Quantitative ex vivo

bioluminescence imaging radiance of cervical lymph nodes and lungs.

The figure shows ex vivo images of dissected organs: left

and right cervical lymph nodes per mouse in the upper row, and the

whole lung specimen per mouse in the lower row (L/R-LN=left and

right cervical lymph nodes). Images from mice dissected on the same

necropsy day are grouped into a single figure. Mouse ID indicates

the individual identification number of each animal. One mouse in

the 60 mg/kg group was excluded from ex vivo imaging because

it died outside the scheduled necropsy time, and prolonged

post-mortem delay precluded reliable assessment. Background

radiance was measured in an adjacent tissue-free area within the

same dish and imaging session for each necropsy day, and was

therefore determined separately for each session. Arrows indicate

metastatic foci.

Quantitative ex vivo

bioluminescence radiance of cervical lymph nodes and lungs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Takashi Murakami

(Department of Microbiology, Saitama Medical University, Moroyama,

Japan) for kindly providing the luciferase-expressing HSC-3 cells

used in this study. This work was also supported by the

infrastructure and equipment at GI-CoRE GSQ, Hokkaido University

(Sapporo, Japan).

Funding

Funding: This work was supported by the Japan Society for the

Promotion of Science KAKENHI (grant nos. JP18K17022, JP22K09922,

and JP25K12969).

Availability of data and materials

The RNA-sequencing data generated in the present

study may be found in the NCBI BioProject database under accession

number PRJNA1347865 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA1347865.

All other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WK designed the study, performed RNA extraction,

animal experiments and bioinformatics analyses, interpreted the

data and drafted the manuscript. MM performed and analyzed the

animal experiments. NM and KH contributed to the design and

analysis of the animal experiments. KT contributed to the

acquisition of animal experimental data, including data collection.

TN, SO and KM contributed to the interpretation and discussion of

the suramin-related data. YO contributed to the analysis and

interpretation of data. WK and YO confirms the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures were approved by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee of Hokkaido University (approval no.

18-0050; Sapporo, Japan) and conducted in accordance with the

institutional guidelines for animal welfare.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools

(ChatGPT) were used to improve the readability and language of the

manuscript, and subsequently, the authors revised and edited the

content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Coropciuc R, Moreno-Rabié C, De Vos W, Van

de Casteele E, Marks L, Lenaerts V, Coppejans E, Lenssen O, Coopman

R, Walschap J, et al: Navigating the complexities and controversies

of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ): A critical

update and consensus statement. Acta Chir Belg. 124:1–11.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

(NCCN): NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Head and

Neck Cancers. Version 1.2026. NCCN, Plymouth Meeting, PA, 2026.

https://www.nccn.org. Accessed January 8,

2026.

|

|

3

|

Steverding D and Troeberg L: 100 years

since the publication of the suramin formula. Parasitol Res.

123(11)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Wiedemar N, Hauser DA and Mäser P: 100

years of suramin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 64:e01168–19.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zaragoza-Huesca D, Rodenas MC,

Peñas-Martínez J, Pardo-Sánchez I, Peña-García J, Espín S, Ricote

G, Nieto A, García-Molina F, Vicente V, et al: Suramin, a drug for

the treatment of trypanosomiasis, reduces the prothrombotic and

metastatic phenotypes of colorectal cancer cells by inhibiting

hepsin. Biomed Pharmacother. 168(115814)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Naviaux RK, Curtis B, Li K, Naviaux JC,

Bright AT, Reiner GE, Westerfield M, Goh S, Alaynick WA, Wang L, et

al: Low-dose suramin in autism spectrum disorder: A small, phase

I/II, randomized clinical trial. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 4:491–505.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Kakuguchi W, Nomura T, Kitamura T,

Otsuguro S, Matsushita K, Sakaitani M, Maenaka K and Tei K:

Suramin, screened from an approved drug library, inhibits HuR

functions and attenuates malignant phenotype of oral cancer cells.

Cancer Med. 7:6269–6280. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Small EJ, Meyer M, Marshall ME, Reyno LM,

Meyers FJ, Natale RB, Lenehan PF, Chen L, Slichenmyer WJ and

Eisenberger M: Suramin therapy for patients with symptomatic

hormone-refractory prostate cancer: Results of a randomized phase

III trial comparing suramin plus hydrocortisone to placebo plus

hydrocortisone. J Clin Oncol. 18:1440–1450. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Cheng B, Gao F, Maissy E and Xu P:

Repurposing suramin for the treatment of breast cancer lung

metastasis with glycol chitosan-based nanoparticles. Acta Biomater.

84:378–390. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wang L, Feng Z, Wang X and Zhang X:

DEGseq: An R package for identifying differentially expressed genes

from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics. 26:136–138. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Young TR, Yamamoto M, Kikuchi SS, Yoshida

AC, Abe T, Inoue K, Johansen JP, Benucci A, Yoshimura Y and

Shimogori T: Thalamocortical control of cell-type specificity

drives circuits for processing whisker-related information in mouse

barrel cortex. Nat Commun. 14(6077)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Foekens JA, Sieuwerts AM, Stuurman-Smeets

EM, Peters HA and Klijn JG: Effects of suramin on cell-cycle

kinetics of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells in vitro. Br J Cancer.

67:232–236. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Al-Kharashi LA, Al-Mohanna FH, Tulbah A

and Aboussekhra A: The DNA methyl-transferase protein DNMT1

enhances tumor-promoting properties of breast stromal fibroblasts.

Oncotarget. 9:2329–2343. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Zhang J, Wu Q, Xie Y, Li F, Wei H, Jiang

Y, Qiao Y, Li Y, Sun Y, Huang H, et al: Ribonucleotide reductase

small subunit M2 promotes the proliferation of esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma cells carcinoma cells via HuR-mediated mRNA

stabilization. Acta Pharm Sin B. 14:4329–4344. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wang J, Zhao L, Li Y, Feng S and Lv G: HuR

induces inflammatory responses in HUVECs and murine sepsis via

binding to HMGB1. Mol Med Rep. 17:1049–1056. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Stetler-Stevenson WG: The tumor

microenvironment: regulation by MMP-independent effects of tissue

inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 27:57–66.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Brew K and Nagase H: The tissue inhibitors

of metalloproteinases (TIMPs): An ancient family with structural

and functional diversity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1803:55–71.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Cabral-Pacheco GA, Garza-Veloz I,

Castruita-De la Rosa C, Ramirez-Acuña JM, Perez-Romero BA,

Guerrero-Rodriguez JF, Martinez-Avila N and Martinez-Fierro ML: The

roles of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in human

diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 21(9739)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Escalona RM, Kannourakis G, Findlay JK and

Ahmed N: Expression of TIMPs and MMPs in ovarian tumors, ascites,

ascites-derived cells, and cancer cell lines: Characteristic

modulatory response before and after chemotherapy treatment. Front

Oncol. 11(796588)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Guns LA, Monteagudo S, Kvasnytsia M,

Kerckhofs G, Vandooren J, Opdenakker G, Lories RJ and Cailotto F:

Suramin increases cartilage proteoglycan accumulation in vitro and

protects against joint damage triggered by papain injection in

mouse knees in vivo. RMD Open. 3(e000604)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chanalaris A, Doherty C, Marsden BD,

Bambridge G, Wren SP, Nagase H and Troeberg L: Suramin inhibits

osteoarthritic cartilage degradation by increasing extracellular

levels of chondroprotective tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases

3. Mol Pharmacol. 92:459–468. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Deng J, Pan T, Liu Z, McCarthy C, Vicencio

JM, Cao L, Alfano G, Suwaidan AA, Yin M, Beatson R and Ng T: The

role of TXNIP in cancer: A fine balance between redox, metabolic,

and immunological tumor control. Br J Cancer. 129:1877–1892.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ling XB, Wei HW, Wang J, Kong YQ, Wu YY,

Guo JL, Li TF and Li JK: Mammalian metallothionein-2a and oxidative

stress. Int J Mol Sci. 17(1483)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Si M and Lang J: The roles of

metallothioneins in carcinogenesis. J Hematol Oncol.

11(107)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Liu Q, Lu F and Chen Z: Identification of

MT1E as a novel tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Pathol Res Pract. 216(153213)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Niroshika KKH, Weerakoon K, Molagoda IMN,

Samarakoon KW, Weerakoon HT and Jayasooriya RGPT: Exploring the

dynamic role of circulating soluble tumor necrosis factor-related

apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) as a diagnostic and prognostic

marker; a review. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

751(151415)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Deng Y, Li AM, Zhao XM, Song ZJ and Liu

SD: Downregulation of tumor protein 53-inducible nuclear protein 1

expression in hepatocellular carcinoma correlates with poor

prognosis. Oncol Lett. 13:1228–1234. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

He X, Zhu Z, Johnson C, Stoops J, Eaker

AE, Bowen W and DeFrances MC: PIK3IP1, a negative regulator of

PI3K, suppresses the development of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Cancer Res. 68:5591–5598. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Uche UU, Piccirillo AR, Kataoka S,

Grebinoski SJ, D'Cruz LM and Kane LP: PIK3IP1/TrIP restricts

activation of T cells through inhibition of PI3K/Akt. J Exp Med.

215:3165–3179. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Peterson EJ, Woods ML, Dmowski SA,

Derimanov G, Jordan MS, Wu JN, Myung PS, Liu QH, Pribila JT,

Freedman BD, et al: Coupling of the TCR to integrin activation by

Slap-130/Fyb. Science. 293:2263–2265. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Chuang HY, Lee E, Liu YT, Lee D and Ideker

T: Network-based classification of breast cancer metastasis. Mol

Syst Biol. 3(140)2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Sadasivam S and DeCaprio JA: The DREAM

complex: Master coordinator of cell cycle-dependent gene

expression. Nat Rev Cancer. 13:585–595. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Krautkramer KA, Linnemann AK, Fontaine DA,

Whillock AL, Harris TW, Schleis GJ, Truchan NA, Marty-Santos L,

Lavine JA, Cleaver O, et al: Tcf19 is a novel islet factor

necessary for proliferation and survival in the INS-1 β-cell line.

Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 305:E600–E610. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Tian Y, Xin S, Wan Z, Dong H, Liu L, Fan

Z, Li T, Peng F, Xiong Y and Han Y: TCF19 promotes cell

proliferation and tumor formation in lung cancer by activating the

Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway. Transl Oncol.

45(101978)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Egeblad M and Werb Z: New functions for

the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev

Cancer. 2:161–174. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Walz TM, Abdiu A, Wingren S, Smeds S,

Larsson SE and Wasteson A: Suramin inhibits growth of human

osteosarcoma xenografts in nude mice. Cancer Res. 51:3585–3589.

1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhang Y, Song S, Yang F, Au JL and

Wientjes MG: Nontoxic doses of suramin enhance activity of

doxorubicin in prostate tumors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 299:426–433.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kikuchi Y, Hirata J, Hisano A, Tode T,

Kita T and Nagata I: Complete inhibition of human ovarian cancer

xenografts in nude mice by suramin and

cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II). Gynecol Oncol. 58:11–15.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Church D, Zhang Y, Rago R and Wilding G:

Efficacy of suramin against human prostate carcinoma DU145

xenografts in nude mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 43:198–204.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Nair AB and Jacob S: A simple practice

guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J Basic Clin

Pharm. 7:27–31. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Reynolds AR: Potential relevance of

bell-shaped and u-shaped dose-responses for the therapeutic

targeting of angiogenesis in cancer. Dose Response. 8:253–284.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Chen D, Song SH, Wientjes MG, Yeh TK, Zhao

L, Villalona-Calero M, Otterson GA, Jensen R, Grever M, Murgo AJ

and Au JL: Nontoxic suramin as a chemosensitizer in patients:

dosing nomogram development. Pharm Res. 23:1265–1274.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Chaudhry V, Eisenberger MA, Sinibaldi VJ,

Sheikh K, Griffin JW and Cornblath DR: A prospective study of

suramin-induced peripheral neuropathy. Brain. 119 (Pt 6):2039–2052.

1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Wu G, Zhou H, Lv D, Zheng R, Wu L, Yu S,

Kai J, Xu N, Gu L, Hong N and Shentu J: Phase I, single-dose study

to assess the pharmacokinetics and safety of suramin in healthy

Chinese volunteers. Drug Des Devel Ther. 17:2051–2061.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Alyoussef A: Suramin attenuated

inflammation and reversed skin tissue damage in experimentally

induced atopic dermatitis in mice. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets.

13:406–410. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|