Introduction

Cervical cancer remains a significant global health

concern, ranking as the fourth most common cancer among women

worldwide. In 2020, ~604,000 new cases and 342,000 associated

deaths were reported, with a disproportionate burden in low- and

middle-income countries (1). The

management of locally advanced cervical cancer (LACC), typically

defined as International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

(FIGO) stages IB2 to IIB (2),

presents a particular therapeutic challenge.

Concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) is the

internationally accepted standard for FIGO IB2-IIB, resulting in

superior overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS)

compared with surgery alone or radiotherapy alone (e.g., higher

response and survival rates; CCRT outperforms neoadjuvant therapy

plus surgery in studies such as EORTC-55994) (3). However, the role of neoadjuvant

chemotherapy (NACT) followed by radical surgery (RS) as an

alternative treatment strategy has been a subject of ongoing

debate. NACT involves administering chemotherapy before the primary

treatment modality, such as RS in this case. The rationale behind

this approach includes reducing tumor size to facilitate surgical

resection, eradicating micrometastatic disease early and

potentially improving surgical outcomes by decreasing the extent of

disease (4).

Several studies have explored the efficacy and

safety of NACT followed by RS compared with RS alone in patients

with LACC (5-8).

A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Zhao et

al (9) evaluated the outcomes

of NACT combined with RS vs. RS alone in patients with cervical

cancer at all stages. The analysis included 13 studies with a total

of 2,158 participants. The findings indicated that, with regard to

OS, disease-free survival (DFS), PFS, local and distant recurrence,

and parametrial infiltration, neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radical

surgery was similar to radical surgery alone (9). Nevertheless, a review by Gadducci and

Cosio (4) assessed the impact of

NACT followed by radical hysterectomy in patients with LACC. The

study reported that this combined approach resulted in higher PFS

and OS times compared with primary radical hysterectomy. These

benefits were observed regardless of the total cisplatin dose,

chemotherapy cycle length or tumor stage (4).

Despite these promising results, the integration of

NACT into standard treatment protocols for LACC is not universally

accepted. Concerns have been raised regarding potential delays in

definitive treatment, the risk of disease progression during

chemotherapy, and the added toxicity associated with additional

treatment modalities. Moreover, the heterogeneity of chemotherapy

regimens and variations in surgical expertise across different

centers contribute to the ongoing debate (1). Recent guidelines from the European

Society of Gynecological Oncology (ESGO) highlight that while NACT

followed by RS is a treatment option, it should not replace the

standard CCRT approach. The guidelines emphasize the need for

individualized treatment planning, considering factors such as

tumor characteristics, patient comorbidities and resource

availability (1,10).

Given the ongoing debate and the potential

implications for patient care, a comprehensive systematic review

and meta-analysis are warranted to critically evaluate the efficacy

and safety of NACT followed by RS vs. RS alone in LACC. The present

analysis aimed to provide clarity on the optimal treatment

approach, thereby informing clinical practice and guiding future

research endeavors.

Materials and methods

Study design

The present systematic review and meta-analysis were

conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of NACT followed by

RS vs. RS alone in patients with LACC. The methodology adhered to

the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and

Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (11).

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed

across multiple databases, including PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), EMBASE (https://www.embase.com/), the Cochrane Central

Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/about-central)

and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/about-cdsr). The

search encompassed studies published from database inception up to

March 2025, without language restrictions. The following medical

subject headings (MeSH) terms and keywords were used: ‘Cervical

cancer’, ‘neoadjuvant chemotherapy’, ‘radical surgery’, ‘radical

hysterectomy’ and ‘locally advanced’. The search had the following

format in PubMed: [‘Cervical Cancer’(MeSH) OR ‘Cervical

Neoplasms’(Title/Abstract) OR ‘cervical carcinoma’

(Title/Abstract)] AND [‘Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy’(MeSH) OR

‘neoadjuvant chemotherapy’(Title/Abstract) OR ‘preoperative

chemotherapy’(Title/Abstract)] AND [‘Radical Surgery’ (MeSH) OR

‘radical hysterectomy’(Title/Abstract) OR ‘surgical

resection’(Title/Abstract)] AND [‘Locally Advanced’(Title/Abstract)

OR ‘FIGO stage IB2’(Title/Abstract) OR ‘FIGO stage

IIB’(Title/Abstract)]. Similar strategies were applied to EMBASE,

CENTRAL and the Cochrane database. Additionally, the reference

lists of relevant articles (9) were

manually screened to identify further pertinent studies. Although

no language restrictions were applied during the database search,

only articles published in English were ultimately included.

Non-English studies were excluded if full translations were not

available or if data extraction was not feasible due to language

barriers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were considered eligible if they met the

following criteria: i) Population: Women diagnosed with LACC,

specifically FIGO stages IB2 to IIB. ii) Intervention: NACT

followed by RS. iii) Comparison: RS alone. iv) Outcomes: Reported

at least one of the following, namely, OS, PFS and DFS times,

recurrence rate, lymph node metastasis or parametrial infiltration.

v) Study design: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective

non-RCTs or retrospective cohort studies.

Exclusion criteria included studies focusing on

early-stage (FIGO stage IA to IB1) or metastatic cervical cancer,

those lacking a comparison between the specified interventions and

studies with insufficient data for extraction (1,9,12).

Data extraction and quality

assessment

Two independent reviewers screened titles and

abstracts for relevance, followed by full-text assessments to

confirm eligibility. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion

or consultation with a third reviewer. Data extracted included

study characteristics (author, year, study design and sample size),

patient demographics, treatment protocols and reported outcomes.

Risk of bias was assessed using different tools depending on study

design. For observational studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)

(13) was applied. For randomized

controlled trials, the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) 2.0 tool

(https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/resources/rob-2-revised-cochrane-risk-bias-tool-randomized-trials)

was used to assess the randomization process, allocation

concealment, blinding, outcome measurement and completeness of

data. The NOS scale assesses three aspects: i) Selection of the

study groups (maximum of 4 stars); ii) comparability of groups

(maximum of 2 stars), indicating appropriate matching or analysis

to control for confounders; and iii) outcome/exposure (maximum of 3

stars), reflecting the adequacy of outcome measurement,

length/adequacy of follow-up and attrition. A total of up to 9

stars can be awarded. Higher scores suggest a lower risk of

bias.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using

comprehensive meta-analysis software, version 2 (Biostat

International, Inc.). A random-effects model was employed to

account for potential heterogeneity among studies, and odds ratios

(ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were

calculated for dichotomous outcomes. Survival outcomes (OS and DFS)

were summarized using ORs, as hazard ratios (HRs) were not

consistently reported or extractable across the included studies.

To distinguish between outcome-specific treatment effects, separate

meta-analyses were performed for OS and DFS as distinct subgroups,

rather than stratifying by study design or patient characteristics.

This approach allowed the assessment of whether the treatment

benefit varied according to the type of survival outcome. A number

of studies provided dichotomized survival data (e.g., 5-year

survival rates or recurrence status at follow-up) without

time-to-event estimates or Kaplan-Meier curves suitable for HR

reconstruction. Therefore, ORs were used to enable a consistent

pooled analysis, while acknowledging that ORs are less informative

than HRs for time-to-event outcomes and that they may overestimate

effect sizes when event rates are high. To assess the robustness of

the results, sensitivity analyses were performed by systematically

excluding each study to evaluate its impact on the overall

findings.

Heterogeneity was assessed using precision interval

analysis, which offers an alternative to the traditional I²

statistic by focusing on the accuracy of the combined effect size

estimate. Publication bias was evaluated through visual inspection

of funnel plots, along with Begg and Mazumdar's rank correlation

test (Kendall's τ values closer to zero indicate less serious

publication bias) and Egger's regression test (if the intercept

term is equal to or close to zero this indicates less serious

publication bias). Furthermore, the fail-safe N test was used to

determine how many missing studies would be needed to nullify the

observed effect, and the Duval and Tweedie's trim-and-fill method

was applied to adjust for potential publication bias by estimating

and adding hypothetical missing studies. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference for all

analyses.

Results

Study selection

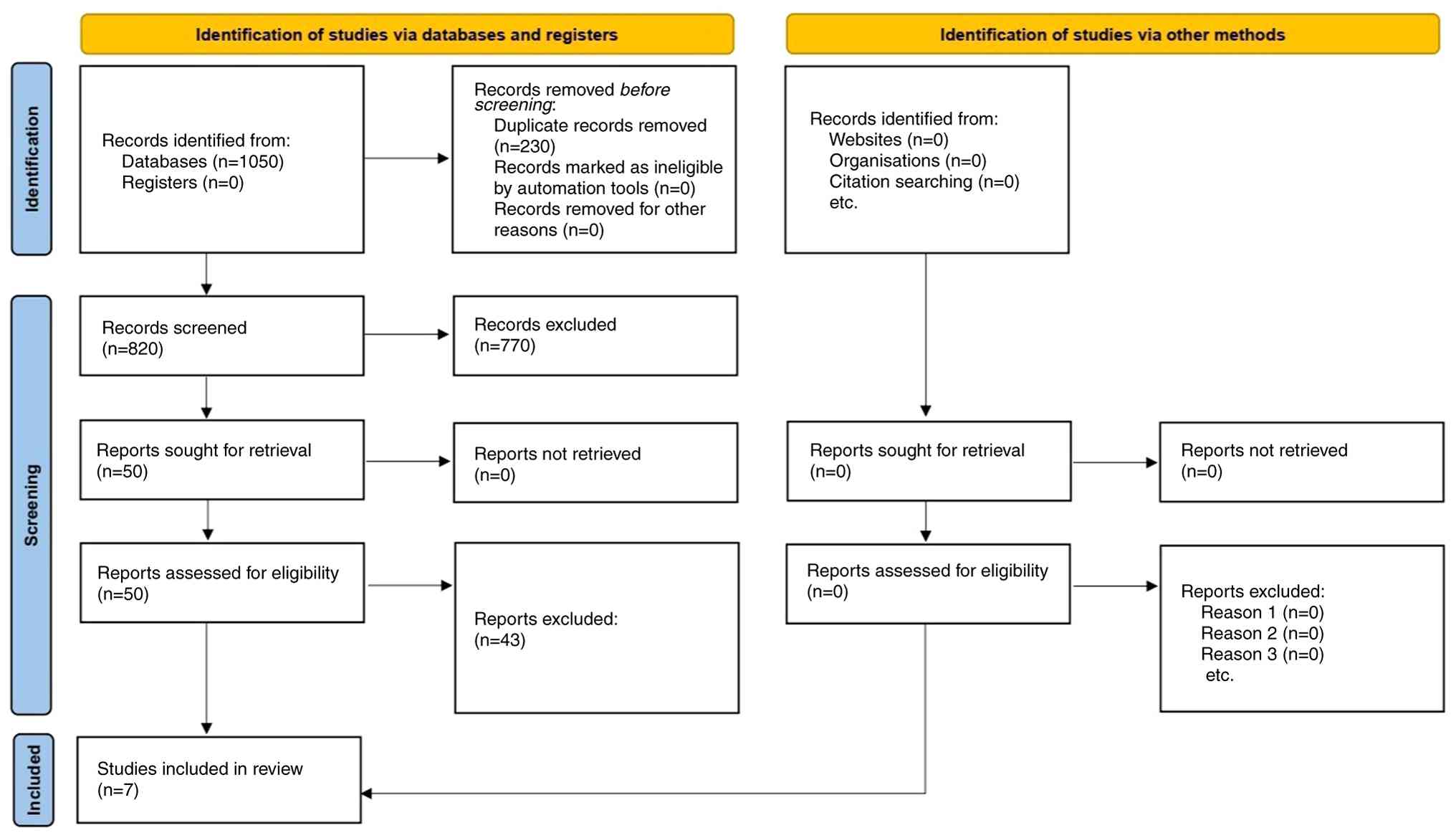

The initial database search yielded 1,050 records.

After removing duplicates, 820 unique records remained. Following

title and abstract screening, 50 articles were selected for

full-text review. Of these, 43 were excluded for the following

reasons: Early-stage or metastatic cervical cancer populations

(n=13), absence of a comparator group matching the inclusion

criteria (n=10), insufficient outcome data (n=9), duplicate or

overlapping cohorts (n=6) and non-English publications without

accessible translations (n=5), resulting in 7 studies being

included in the final analysis (5-8,14-16).

A PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process is

provided in Fig. 1. Among the 7

included studies, 3 were RCTs (6,8,15), and

4 were observational cohort studies (5,7,14,16).

Table I provides a comprehensive

summary of the general characteristics and demographics of the

included studies comparing NACT followed by RS vs. RS alone in

LACC. The table presents key data on study sample sizes, patient

demographics, FIGO staging, histological subtypes, treatment

groups, lymph node metastasis rates, survival outcomes, and NACT

chemotherapy regimens and doses. The total sample size of the

included patients in this meta-analysis is 2,231.

| Table IGeneral characteristics and

demographics of included studies. |

Table I

General characteristics and

demographics of included studies.

| First author,

year | Sample size, n | Mean age (range),

years | FIGO stages | Histological

types | Treatment groups | Lymph node

metastasis, % | Survival outcome | NAC regimen and

doses | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Behtash et al,

2006 | 182 | 48 (26-75) | IB2-IIA | Squamous (majority),

adenocarcinoma | NACT + RS (n=22) vs.

RS alone (n=160) | 36 RS; 47.1 NACT | OS not significantly

different (P=0.06) | 50 mg/m² cisplatin +

1 mg/m² vincristine (every 10 days for 3 cycles) | (5) |

| Chen et al,

2008 | 142 | 44 (25-74) | IB2-IIB | Squamous,

adenocarcinoma | NACT + RS (n=72) vs.

RS alone (n=70) | 16.0 NACT responders;

45.5 non-responders | NACT responders ha

better DFS and lower recurrence (P<0.001) | 100 mg/m² cisplatin

(day 1) + 4 mg/ m² mitomycin C (IM, days 1-5) + 24 mg/kg/day 5-FU

(IV, days 1-5) | (6) |

| Gong et al,

2016 | 800 | Not specified | IB2-IIB | Squamous,

adenocarcinoma | NACT + RS (n=411) vs.

RS alone (n=389) | Not specified | 5-year PFS 80.3%

(NACT) vs. 81.0% (RS) | Carboplatin +

cisplatin, Carboplatin + cisplatin, xpingyangmycin, ifosfamide,

5-FU, paclitaxel, vincristine (1-3 cycles) | (7) |

| Katsumata et

al, 2013 | 134 | Not specified | IB2-IIB | Squamous cell

carcinoma | NACT + RS (n=67) vs.

RS alone (n=67) | Not specified | 5-year OS: 70.0%

(NACT) vs. 74.4% (RS) (P=0.85) | 7 mg Bleomycin

(days 1-5) + 0.7 mg/m² vincristine (day 5) + 7 mg/m² mitomycin (day

5) + 14 mg/m² cisplatin (days 1-5) | (8) |

| Kim et al,

2011 | 524 | 50.6±11.5 | IB1-IIA | Squamous

(majority), non-squamous | NACT + RS (n=73)

vs. RS alone (n=451) | 23.9 RS; 23.3

NACT | Not specified | 5-FU/cisplatin or

paclitaxel/carboplatin (median, 3 cycles) | (16) |

| Yang et al,

2016 | 219 | 47 (23-66) | IB2-IIB | Squamous,

adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous | NACT + RS (n=109)

vs. RS alone (n=110) | Not specified | No significant

difference in DFS/OS between groups | 60 mg/m² irinotecan

(IV, days 1, 8 and 15) + 70 mg/m² cisplatin (IV, day 1) or 175

mg/m² paclitaxel (IV, day 1) + 70 mg/m² cisplatin (IV, day 1) (1-2

cycles) | (15) |

| Namkoong et

al, 1995 | 230 | 48 (30-58) | IB-IIB | Squamous

(majority), adenocarcinoma | NACT + RS (n=92)

vs. RS alone (n=138) | 18.5 NACT; 34.0

RS | 4-Year tumor-free

survival: 81.5% (NACT) vs. 66.7% (RS) (P=0.0067) | 4 mg/m² vinblastine

(days 1-2), 15 mg/m² bleomycin (days 1, 7 and 14), 60 mg/m²

cisplatin (day 1); every 3 weeks | (14) |

Outcomes and synthesis of results

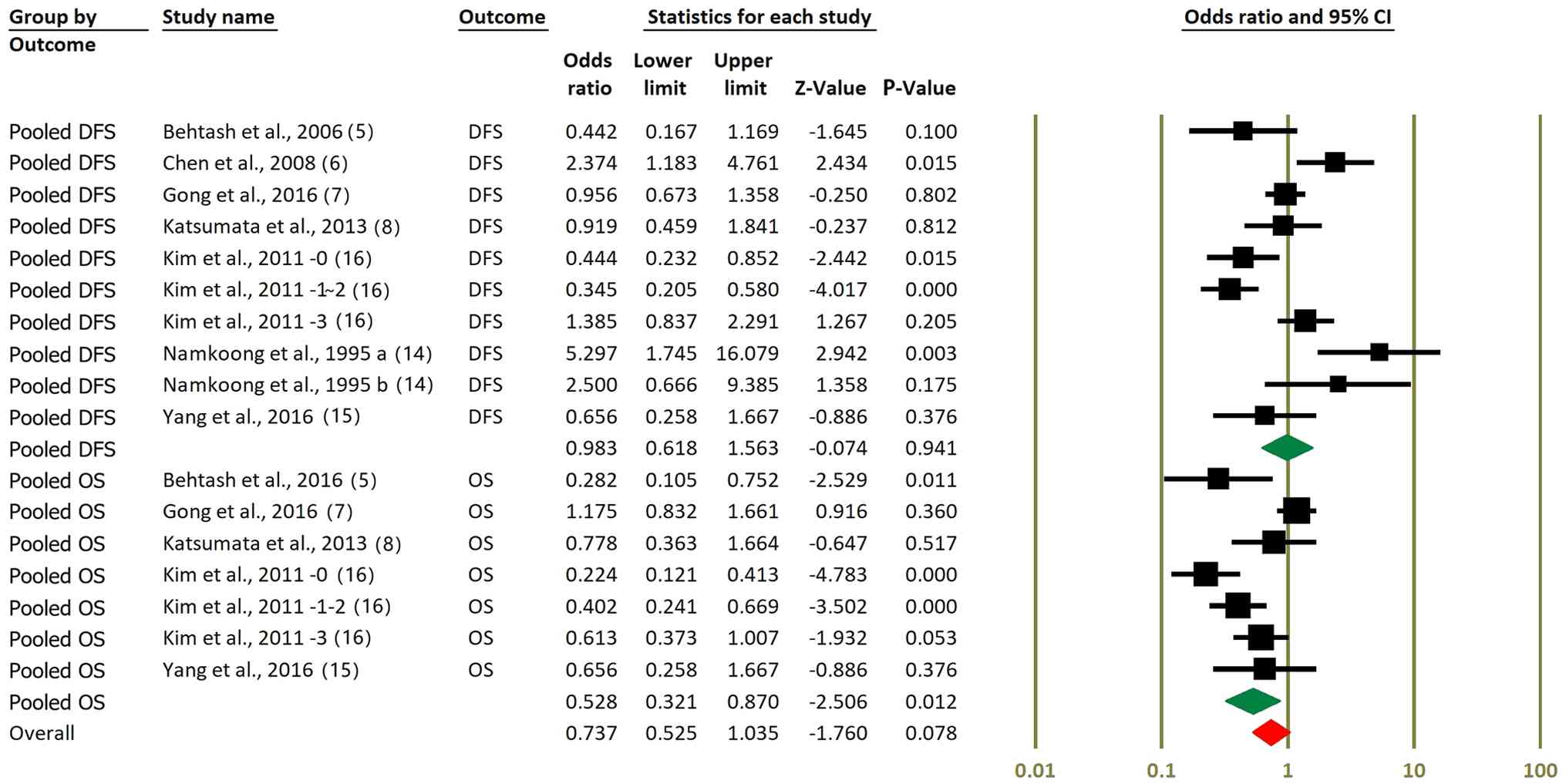

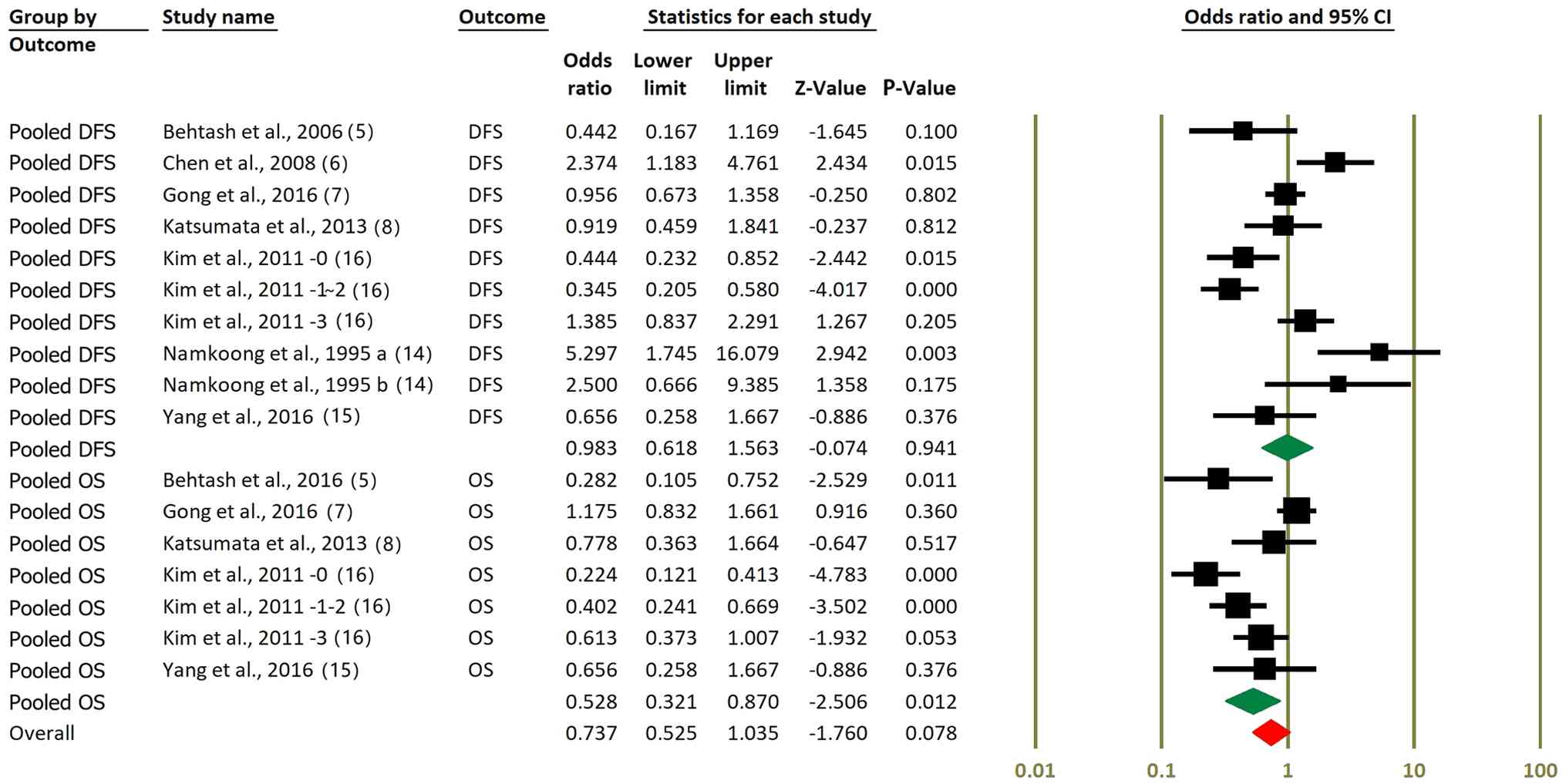

A subgroup-specific meta-analyses was performed

based on survival outcome type (OS vs. DFS). Fig. 2 presents the survival

outcome-specific meta-analyses for DFS and OS. For DFS, the pooled

OR was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.62-1.56; P=0.941), indicating no significant

benefit of NACT followed by RS compared with surgery alone.

Although several individual studies reported improvements in DFS,

these effects did not translate into a significant pooled estimate.

By contrast, the pooled analysis of OS data showed a more favorable

effect. When restricted to OS outcomes only, the pooled OR was 0.53

(95% CI: 0.32-0.87; P=0.012), suggesting a statistically

significant survival benefit associated with NACT. However, when

all studies contributing OS and DFS data are combined, the overall

effect estimate becomes more modest and borderline significant (OR,

0.74; 95% CI, 0.53-1.04; P=0.078). These findings highlight a

potential outcome-specific benefit of NACT for OS but not for

DFS.

| Figure 2Forest plots comparing DFS and OS in

NACT + RS vs. RS alone. Pooled ORs and 95% CIs for DFS are

presented, showing no significant difference between NACT + RS and

RS alone (OR, 0.98; P=0.941). Pooled OS data are presented, with a

significant benefit shown in subgroup analysis (OR, 0.53; P=0.012);

however, when all OS and DFS data were combined, the advantage

approached but did not reach statistical significance (OR, 0.74;

P=0.078). Kim et al (16)

-0, -1~2 and -3 represent the number of metastatic lymph nodes;

this study statistically analyzed OS and DFS after grouping based

on the number of lymph node metastases. Namkoong et al

(14) 1995 a and b represent

squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, respectively. DFS,

disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; NACT, neoadjuvant

chemotherapy; RS, radical surgery; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence

interval. |

Sensitivity analysis

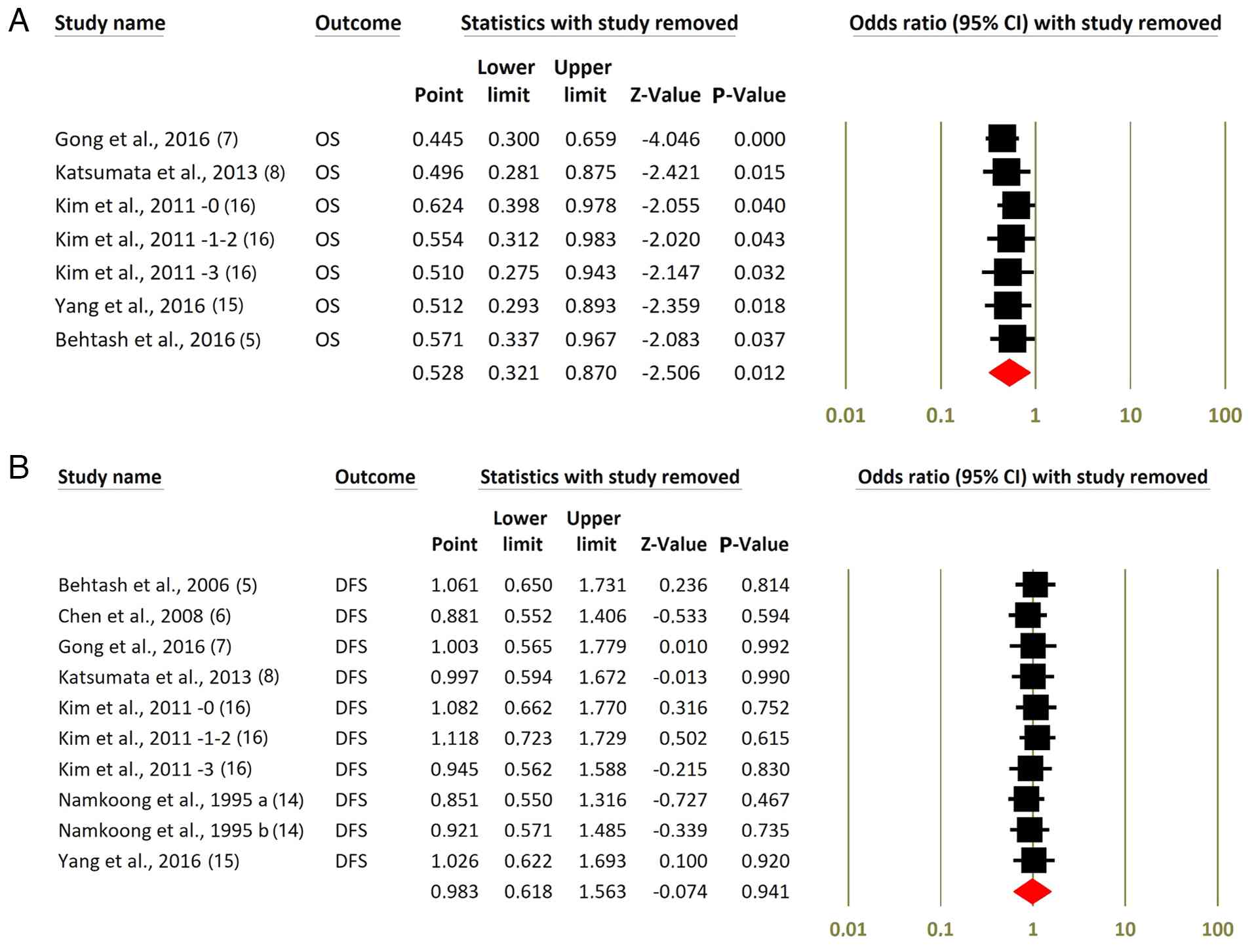

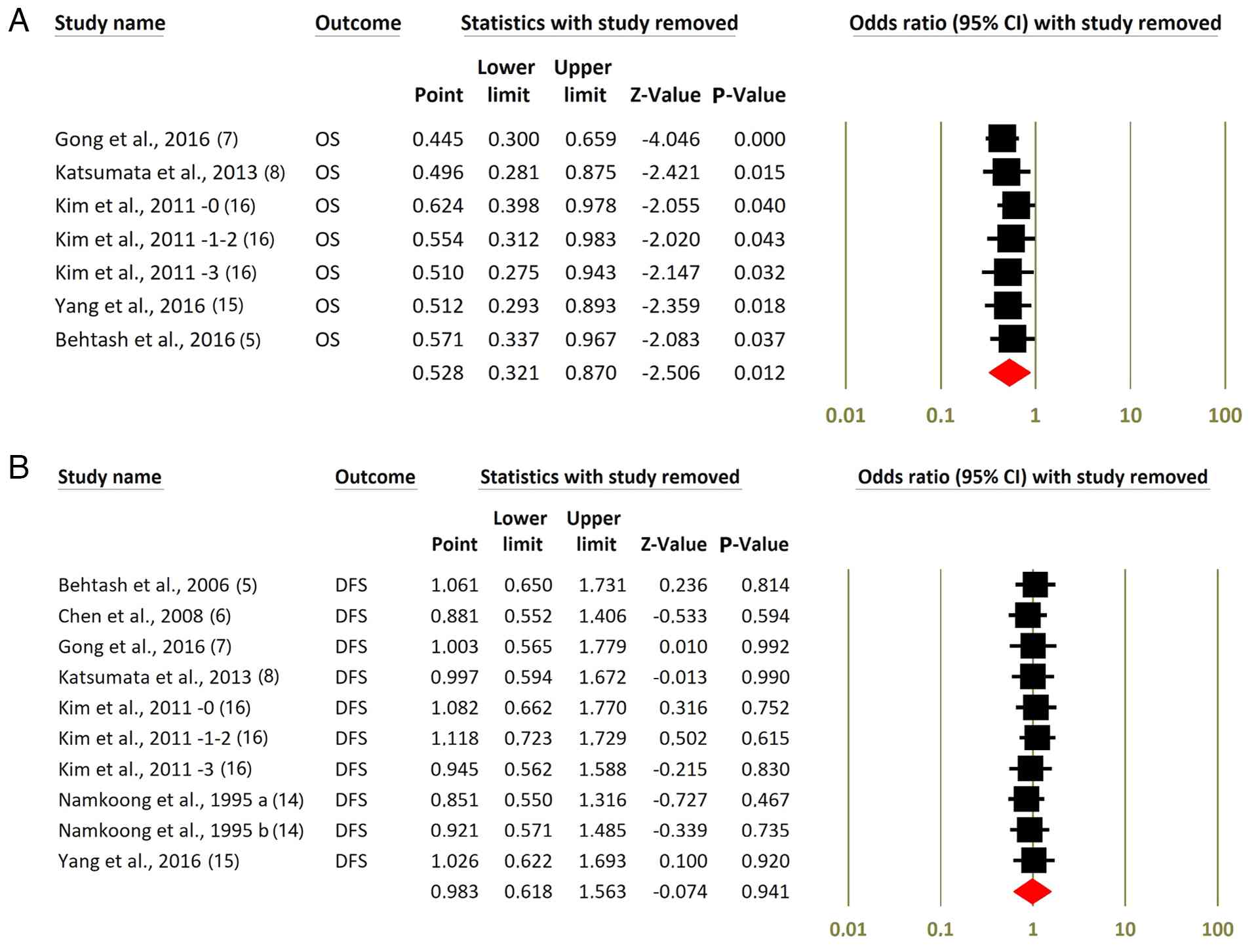

In the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for OS

(Fig. 3A), removing each study one

at a time resulted in ORs ranging from 0.45 to 0.62, all with

statistically significant P-values of <0.05. The combined

estimate remains significant (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.32-0.87,

P=0.012), indicating that no single trial primarily drives the

benefit in OS. By contrast, for DFS (Fig. 3B), excluding individual studies

yields summary ORs consistently near 1.0, with P-values from 0.467

to 0.990, highlighting the lack of a significant overall effect on

DFS and confirming that the null finding is robust against the

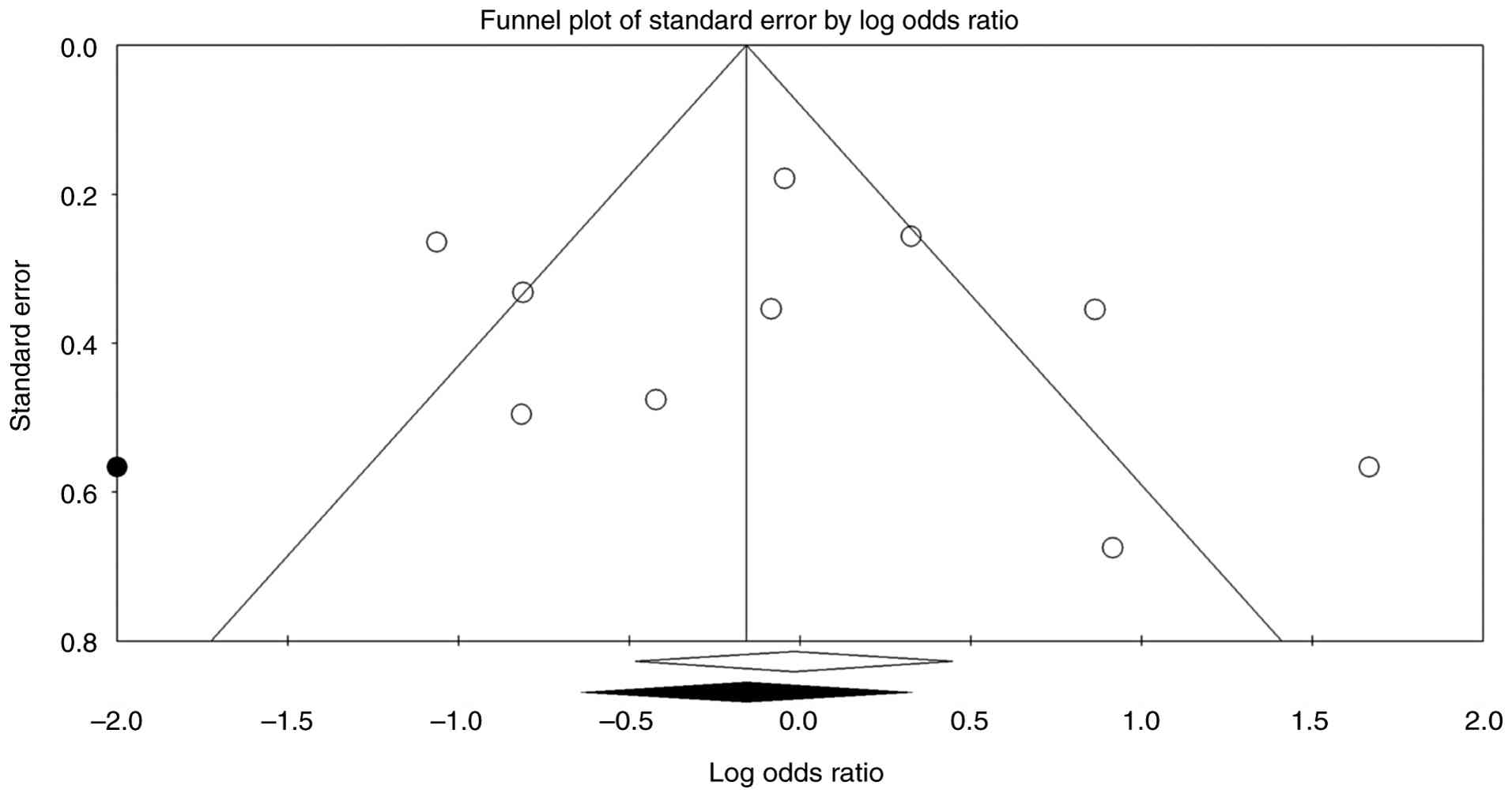

omission of any single study. The funnel plot of log ORs against

standard error appears fairly symmetrical, suggesting no major

signs of publication bias (Fig. 4).

Begg and Mazumdar's rank correlation produces Kendall's τ values

near 0.2 with non-significant P-values (two-tailed P>0.4), while

Egger's regression test also shows no evidence of small-study

effects (P>0.5). Duval and Tweedie's trim-and-fill analysis

detects no missing studies on either side of the mean, leaving the

pooled estimate unchanged. The fail-safe N similarly indicates that

no additional studies are needed to bring the meta-analysis to a

non-significant level. Overall, these findings suggest that the

observed effect estimates are not heavily influenced by publication

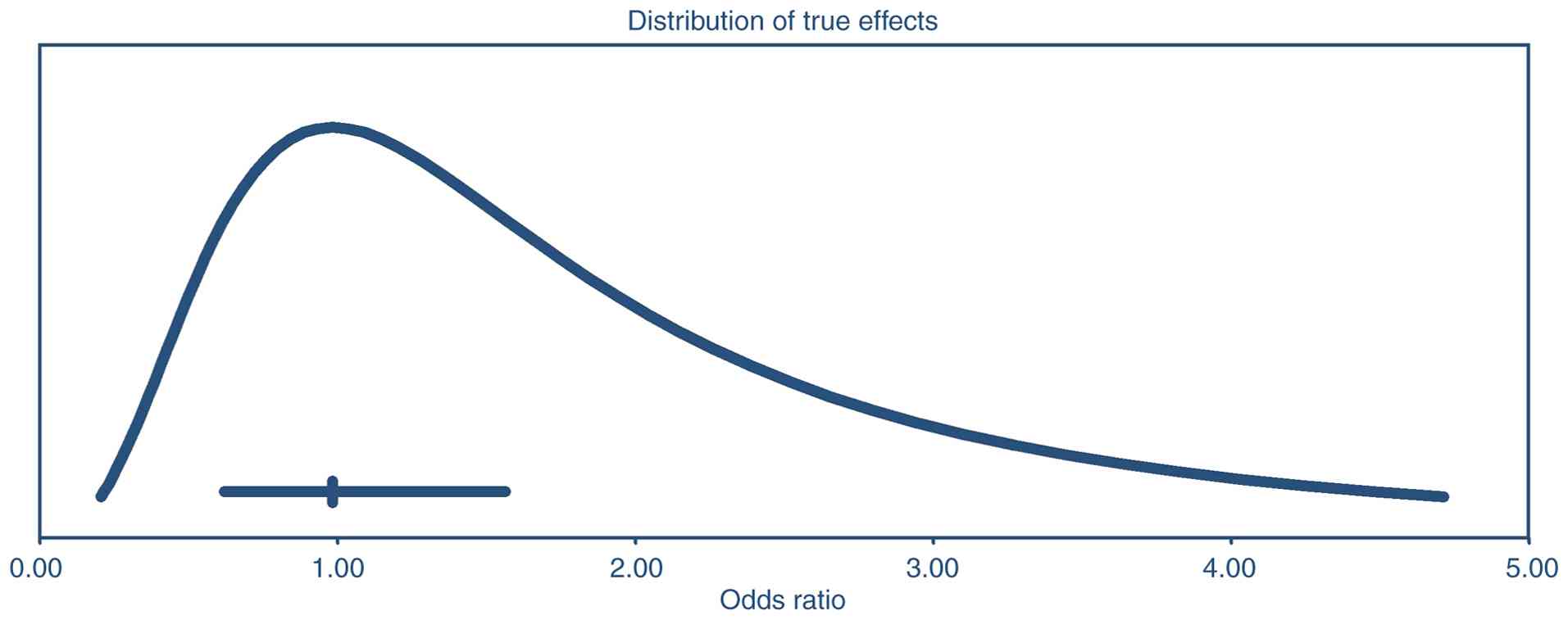

bias. The prediction-interval analysis (Fig. 5) indicates that, although the

average effect size (OR, 0.98) has a 95% CI of 0.62-1.56 implying

no clear departure from unity; the true effect across similar

populations could range widely, from about 0.21 to 4.71. Therefore,

even though the pooled estimate does not significantly differ from

no effect, there is substantial heterogeneity; some settings might

observe smaller effects (possibly null or worse), while others

could see much larger effects.

| Figure 3Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for

OS and DFS. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis presented for (A) OS

and (B) DFS in patients treated with NACT followed by RS vs. RS

alone. (A) The exclusion of individual studies yields ORs

consistently <1.0, with statistically significant P-values,

indicating a stable OS benefit for NACT + RS. (B) By contrast,

excluding individual studies does not meaningfully alter the DFS

estimate, with ORs consistently near 1.0 and non-significant

P-values, confirming the robustness of the null effect on DFS. Kim

et al (16) -0, -1~2 and -3

represent the number of metastatic lymph nodes; this study

statistically analyzed OS and DFS after grouping based on the

number of lymph node metastases. Namkoong et al (14) 1995 a and b represent squamous cell

carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, respectively. OS, overall survival;

DFS, disease-free survival; NACT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RS,

radical surgery; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. |

Quality assessment

The quality of observational studies was evaluated

using the NOS scale (Table II),

and the quality of RCTs was evaluated using the Cochrane RoB 2.0

tool (Table III). Among the

studies assessed, the study by Gong et al (7) received the highest total score (9

points), reflecting strong methodological rigor in terms of

participant selection, group comparability and outcome assessment.

Namkoong et al (14)

achieved a score of 8, demonstrating a well-balanced design with

appropriate controls for confounders and thorough outcome

evaluation. Behtash et al (5) and Kim et al (16) received scores of 6, suggesting

moderate quality due to potential limitations in comparability or

outcome assessment. These studies may have had fewer controls for

confounding factors or shorter follow-up periods compared with

others in the analysis. The three RCTs (6,8,15)

demonstrated generally low risk of bias in randomization, outcome

assessment and data completeness, although blinding was not

feasible in most surgical trials. No major threats to internal

validity were identified. Overall, the included studies were of

acceptable quality for meta-analysis, with most receiving high

scores, indicating a low risk of bias. While some studies exhibited

minor limitations in comparability or outcome assessment, the

overall methodological rigor supports the reliability of the pooled

findings.

| Table IIQuality assessment of included

studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. |

Table II

Quality assessment of included

studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

| First author,

year | Selection (score

0-4) | Comparability

(score 0-2) | Outcome/exposure

(score 0-3) | Total score (score

0-9) | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Behtash et

al, 2006 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | (5) |

| Gong et al,

2016 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | (7) |

| Kim et al,

2011 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | (16) |

| Namkoong et

al, 1995 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | (14) |

| Table IIIRisk of bias assessment for included

randomized controlled trials using Cochrane RoB 2.0

toola. |

Table III

Risk of bias assessment for included

randomized controlled trials using Cochrane RoB 2.0

toola.

| First author,

year | Bias arising from

the randomization process | Bias due to

deviations from intended interventions | Bias due to missing

outcome data | Bias in the

measurement of the outcome | Overall risk of

bias | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Chen et al,

2008 | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | (6) |

| Katsumata et

al, 2013 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | (8) |

| Yang et al,

2016 | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | (15) |

Heterogeneity analysis

Meta-regression was conducted to assess whether

study-level variables explained heterogeneity in OS estimates. The

covariates included chemotherapy regimen, proportion of FIGO stage

IIB patients, publication year, study design and sample size. None

of the included covariates showed a statistically significant

association with the treatment effect. Specifically, the proportion

of FIGO IIB patients (coefficient, -0.305; P=0.642), chemotherapy

regimen (coefficient, 2.470; P=0.551), publication year

(coefficient, 0.008; P=0.666), study design (coefficient, -5.735;

P=0.559) and sample size (coefficient, 0.016; P=0.631) were not

significant moderators. These findings suggest that the variability

in OS effect sizes could not be adequately explained by these

study-level characteristics, indicating residual unexplained

heterogeneity (Table IV). Also,

meta-regression analysis was performed to explore sources of

heterogeneity in DFS outcomes using five covariates: Chemotherapy

regimen, proportion of FIGO stage IIB patients, publication year,

study design (randomized controlled trial vs. observational) and

sample size. The proportion of FIGO IIB patients was significantly

associated with effect size (coefficient, -0.049; P=0.027),

suggesting that higher proportions of advanced-stage patients were

linked to less favorable treatment effects. None of the other

covariates, including chemotherapy regimen (coefficient, 0.098;

P=0.289), publication year (coefficient, 0.003; P=0.936), study

design (coefficient, -0.240; P=0.496) or sample size (coefficient,

0.0003; P=0.932), reached statistical significance. These results

indicate that stage distribution may partially explain the observed

heterogeneity (I²=58%), whereas other study-level characteristics

were not significant moderators (Table

V).

| Table IVMeta-regression results for OS

outcomesa. |

Table IV

Meta-regression results for OS

outcomesa.

| Covariate | Coefficient | Standard error | Z-value | P-value | 95% CI (lower) | 95% CI (upper) |

|---|

| Constant | -0.1140 | 0.1636 | -0.70 | 0.5578 | -0.8178 | 0.5897 |

| Chemotherapy

regimen | 2.4702 | 3.4722 | 0.71 | 0.5506 | -12.4694 | 17.4097 |

| FIGO IIB patients

(%) | -0.3046 | 0.5615 | -0.54 | 0.6418 | -2.7205 | 2.1112 |

| Publication

year | 0.0080 | 0.0160 | 0.50 | 0.6664 | -0.0607 | 0.0767 |

| Study design

(0=observational; 1=RCT) | -5.7345 | 8.2507 | -0.70 | 0.5589 | -41.2343 | 29.7652 |

| Sample size | -0.0156 | 0.0278 | -0.56 | 0.6307 | -0.1352 | 0.1040 |

| Table VMeta-regression results for DFS

outcomesa. |

Table V

Meta-regression results for DFS

outcomesa.

| Covariate | Coefficient | Standard error | Z-value | P-value | 95% CI (lower) | 95% CI (upper) |

|---|

| Constant | -1.8372 | 2.0150 | -0.91 | 0.3916 | -6.1210 | 2.4460 |

| Chemotherapy

regimen | 0.0975 | 0.0856 | 1.14 | 0.2888 | -0.0854 | 0.2805 |

| FIGO IIB patients

(%) | -0.0486 | 0.0211 | -2.30 | 0.0269 | -0.0917 | -0.0055 |

| Publication

year | 0.0034 | 0.0411 | 0.08 | 0.9357 | -0.0886 | 0.0954 |

| Study design

(0=observational; 1=RCT) | -0.2396 | 0.3393 | -0.71 | 0.4958 | -1.0358 | 0.5566 |

| Sample size | 0.0003 | 0.0031 | 0.09 | 0.9320 | -0.0064 | 0.0071 |

Incidence of complications, adverse

reactions, recurrence rate and distant metastasis rate

Several of the included studies evaluated the safety

profile of NACT followed by RS compared with RS alone in LACC. Gong

et al (7) found that

patients in the NACT + RS group had a lower incidence of

postoperative complications (7.30 vs. 13.62%; P=0.002) and

postoperative radiotherapy/radiochemotherapy-related adverse

effects (3.16 vs. 4.63%; P<0.001) compared with the RS-alone

group. On the other hand, Behtash et al (5) reported similar recurrence rates in

both groups, but the NACT group exhibited a slightly higher rate of

distant metastases, although this was not statistically

significant.

Operation time and intraoperative

blood loss

Patients undergoing NACT followed by surgery in the

study by Gong et al (7) had

a longer operative time (233.66 vs. 224.37 min; P=0.008) and higher

intraoperative blood loss (750.34 vs. 684.41 ml; P=0.011) compared

with the RS alone group, indicating increased complexity in

surgery. By contrast, Katsumata et al observed that surgical

morbidity rates were comparable between both groups, suggesting

that pre-surgical chemotherapy did not necessarily complicate

surgical outcomes (8).

Hematological toxicity

In the trial reported by Katsumata et al

(8), grade 3 or 4 hematological

toxicity was more frequent in the NACT group, particularly

leukopenia (41%), neutropenia (56%) and thrombocytopenia (27%).

Similarly, Yang et al (15)

reported that neutropenia and diarrhea were significantly higher in

the irinotecan-cisplatin (IP) chemotherapy group compared with that

in the paclitaxel-cisplatin (TP) group, although both regimens had

tolerable toxicities.

Postoperative radiation

requirements

Katsumata et al (8) noted lower rates of postoperative

radiation requirements in the NACT group (58 vs. 80%; P=0.015),

which translated to fewer late radiation-related adverse events.

Late adverse events such as urinary retention, lymphedema,

vesicovaginal fistula and bowel obstruction were more frequent in

the RS-alone group.

Discussion

The management of LACC has historically revolved

around two main strategies: Primary CCRT or the combination of NACT

followed by RS (1,4,17,18).

In recent years, the potential role of NACT before surgery has

garnered increasing interest, as it may offer advantages such as

downstaging the tumor, facilitating more complete resections and

potentially reducing distant metastases (5,6).

However, the evidence supporting a definitive survival benefit,

particularly when compared with the standard of care, remains

inconsistent (7,8,19). The

meta-analysis of the present study evaluated the efficacy and

safety of NACT followed by RS relative to RS alone in women with

LACC (FIGO stages IB2-IIB). These results confirm previous

observations for OS while casting doubt on earlier claims regarding

DFS improvement. In the present pooled analysis of 7 studies,

encompassing a total of 2,231 patients, a complex picture

concerning survival outcomes was observed. For DFS, the combined OR

hovered near 0.98, with a 95% CI of 0.62-1.56 and a P-value of

0.941. This result indicates that there was no statistically

significant difference in DFS between patients receiving NACT

followed by RS and those undergoing surgery alone. Particularly,

several individual studies within the meta-analysis did report

improvements in DFS, but these positive effects did not translate

into a significant advantage when pooled across all studies. By

contrast, the meta-analysis of OS demonstrated a somewhat more

favorable outcome, particularly in a subset of included data. In

that subgroup, the OR for OS was 0.53 (95% CI, 0.32-0.87; P=0.012),

indicating a statistically significant benefit of NACT plus RS over

RS alone. However, when all OS data points were combined in the

larger overall analysis, the OR shifted to 0.74 (95% CI, 0.53-1.04;

P=0.078), crossing the threshold of statistical significance and

thus suggesting only a borderline benefit. These findings suggest

that NACT could be beneficial in selected cases; however, the

evidence does not support a consistent survival advantage across

all settings. Given that CCRT is the standard of care and

consistently yields better outcomes than surgery-based approaches

alone, the modest OS advantage of NACT + RS observed against RS

should not be misinterpreted as an alternative to CCRT. Without

direct comparisons to CCRT, the clinical implications of NACT + RS

are most relevant in resource-limited settings or for patients

unable to undergo radiotherapy.

In the present study, the leave-one-out sensitivity

analyses for OS demonstrated that, upon excluding any individual

trial, the pooled estimate remained comparatively stable (OR range,

0.45-0.62), consistently showing a significant or

borderline-significant advantage for NACT plus RS. IBy contrast,

the exclusion of individual studies in the DFS analysis

consistently yielded ORs near 1.0 (P-values ranging from 0.467 to

0.990), emphasizing the lack of evidence for DFS benefit and the

robustness of this null finding. Furthermore, no strong indications

of publication bias were found based on Begg and Mazumdar's rank

correlation test, Egger's regression test, the trim-and-fill method

or the fail-safe N, all of which suggest that the conclusions about

the overall effect estimates are not likely to be confounded by

missing or selectively reported studies.

The results of the present study align in part with

the those of the meta-analysis conducted by Zhao et al

(9), which included 13 studies and

found that the combination of NACT and RS significantly improved OS

and reduced local and distant recurrence, lymph node metastasis and

parametrial infiltration in LACC. In that analysis, however, more

consistent improvements in DFS were noted, whereas the pooled data

of the present study did not show a statistically significant

benefit in disease-free intervals. One possible explanation for

this discrepancy is that Zhao et al (9) included a slightly different set of

studies and varying DFS definitions, follow-up durations and timing

of assessments, which may have influenced reported outcomes.

Gadducci and Cosio (4) similarly

identified improvements in both PFS, a surrogate closely related to

DFS, and OS with NACT followed by RS in LACC. The meta-analysis

emphasized that these benefits seemed to persist regardless of the

total cisplatin dose, cycle length or tumor stage. The results of

this study indicate that although neoadjuvant chemotherapy may

improve OS rates, when all the data are taken into account, this

advantage is not particularly clear. Such mixed results are not

unusual in the setting of relatively heterogeneous treatment

protocols; the variability in chemotherapy regimens, dosing and

timing could attenuate any potential benefit in pooled

analyses.

It is also instructive to situate the findings of

the present study against the prevailing standard of CCRT. Although

the analysis of the present study did not compare NACT plus RS

against CCRT per se, several large RCTs and meta-analyses have

established that CCRT is highly effective for LACC, leading to

robust local control and improved survival rates (10,17).

The 2023 ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines (10) recognize that NACT followed by

surgery can be an option for selected patients, but do not broadly

recommend it as a replacement for CCRT. This stance echoes the

ambivalence in the present study's findings, which do not show a

consistent or statistically robust advantage of NACT in terms of

DFS across the board, and only a borderline or context-dependent

improvement in OS.

The lack of a significant improvement in DFS,

compared with a borderline benefit in OS, raises several

hypotheses. One possibility is that, while NACT may help debulk

tumors and eradicate micrometastatic disease early, the subsequent

RS and any adjuvant treatment might be sufficient to minimize local

recurrences in both groups, thus balancing DFS outcomes over time

(12,20). Another factor could be that patients

who receive NACT but do not respond well might go on to have

surgery delayed or complicated by chemotherapy-induced side

effects, ultimately erasing some of the theoretical benefits on

DFS. Additionally, DFS in LACC can be influenced by multiple

confounders, such as tumor biology, patient comorbidities and

post-surgical treatment decisions (e.g., radiotherapy after surgery

in cases with high-risk features) (20). By contrast, the modest improvement

in OS might suggest that some patients, perhaps those with highly

chemosensitive tumors, experience eradication or substantial

downstaging of micrometastatic disease, thus improving their

overall life expectancy. It is conceivable that such a ‘response

subgroup’ benefits disproportionately from early systemic therapy,

tipping OS statistics in favor of NACT plus RS. Indeed, if a subset

of patients is particularly responsive to neoadjuvant regimens,

they might experience longer survival even if local recurrences

(the primary driver of DFS) are not markedly affected at the

population level. Additional research is needed to refine the

identification of these potential responders based on tumor

biology, molecular markers and precise imaging.

Moderate heterogeneity was noted across the included

studies in the present analysis. The prediction-interval analysis

for DFS indicated that while the summary effect size showed no

significant difference from unity (OR, 0.98), the distribution of

true effects across settings could range widely, from 0.21 to 4.71.

This wide range suggests that while some centers or specific

patient subgroups might observe a substantial benefit of NACT,

others could see minimal or no advantage. Also, in some contexts,

NACT + RS may be harmful. These findings highlight the uncertainty

of generalizing the results of the present study and suggest that

treatment decisions should be individualized and guided by

context-specific factors, such as chemotherapy regimen, surgical

expertise and patient characteristics. Factors influencing this

variability likely include differences in chemotherapy regimens

(e.g., platinum-based doublets vs. single-agent cisplatin),

treatment duration (number of cycles), dosing intensity, and

subsequent surgical technique and expertise. Further heterogeneity

stems from differences in the baseline characteristics of patient

populations: Tumor size, histological subtype (squamous vs.

adenocarcinoma) and patient performance status can all modulate

outcomes (1,4). To explore the sources of heterogeneity

in OS outcomes, a meta-regression analysis was conducted

incorporating key study-level variables, including chemotherapy

regimen, study design, publication year, proportion of FIGO stage

IIB patients and total sample size. None of these covariates

demonstrated a statistically significant moderating effect on the

observed treatment outcomes. For instance, the proportion of stage

IIB patients (coefficient, -0.305; P=0.642) and chemotherapy

regimen (coefficient, 2.470; P=0.551) showed no association with

effect size. Similarly, neither study design nor sample size

significantly explained between-study variability. These findings

indicate that the moderate heterogeneity (I²=58%) observed in the

pooled OS estimate could not be accounted for by the tested

moderators, suggesting the presence of residual clinical or

methodological variability not captured in the model. Future trials

should collect patient-level data and apply consistent reporting

standards to resolve these uncertainties.

Despite these variations, the overall methodological

quality of the included studies (as evaluated by the NOS and

Cochrane RoB tool) was acceptable to high, with most of the studies

having a score of ≥6. This finding suggests that the risk of bias

at the study design level, especially selection bias and outcome

assessment bias, was generally low. Even the studies with moderate

scores (6 points) offered reasonably robust data. Hence, the

observed inconsistencies are more likely attributable to genuine

clinical heterogeneity than to methodological flaws.

From a clinical standpoint, the findings of the

present study support the principle of individualized patient

selection for NACT. Even if the benefit in DFS is not established,

a borderline improvement in OS for certain populations indicates

that NACT plus RS may be advantageous for carefully chosen

patients. For instance, younger patients with good performance

status and bulky but resectable tumors might derive greater

benefit, particularly if their tumors are chemosensitive (5,6).

Conversely, older patients or those with significant comorbidities

may be at higher risk of toxicity from chemotherapy, without a

sufficient downstaging advantage to justify the addition of

NACT.

The safety profile of NACT followed by RS is

generally acceptable, with a lower incidence of postoperative

complications and a reduction in the occurrence of adverse

reactions related to radiotherapy (8). However, NACT is associated with

increased hematological toxicity and chemotherapy-related side

effects. Surgical complexity (operative time and blood loss) may be

slightly increased in the NACT group, though this does not appear

to impact long-term surgical morbidity. These findings suggest that

while NACT offers some advantages in reducing post-surgical

radiation complications, patient selection remains critical to

balance the risks of chemotherapy toxicity and surgical challenges

(8).

One strength of the present study is the consistent

absence of publication bias across four complementary tests. The

inclusion of both prospective and retrospective studies, while

adding heterogeneity, broadens the generalizability of the results

of the present study. A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was also

conducted, to ensure that no single study unduly influenced the

conclusions of the present study.

The findings of the present should be interpreted in

the context of certain limitations. First, the relatively small

number of included studies (n=7) imposes constraints on the

statistical power, particularly for subgroup analyses. Second, the

analysis relied on available data for DFS and OS, but there was

variation in how outcomes were defined and measured across studies.

Some studies may have reported PFS or event-free survival as

opposed to DFS, and they used different follow-up intervals. Third,

heterogeneity in chemotherapy regimens, the number of treatment

cycles and surgical expertise can all cause variations in effect

sizes. This heterogeneity is partly captured by the wide prediction

intervals, indicating that the true effect of NACT in a given

clinical setting could deviate substantially from the pooled

estimate. Additionally, one important methodological limitation of

the present meta-analysis is the use ORs instead of HRs to analyze

survival outcomes. While HRs are the preferred and statistically

appropriate metric for time-to-event data such as OS and DFS, a

number of the included studies reported survival outcomes in

dichotomous form (e.g., 3- or 5-year survival status) without

providing HRs, log-rank P-values or Kaplan-Meier curves suitable

for reconstruction. Due to this constraint, ORs were used to ensure

analytic consistency across all studies. However, it is important

to recognize that ORs may overestimate the strength of association,

particularly when event rates are high and they do not capture the

time component of survival. This issue has been acknowledged in the

statistical analysis section and it is recommended that future

meta-analyses prioritize time-to-event metrics where available to

provide more accurate estimates of treatment effects. Finally, NACT

plus RS directly was not compared with the current standard

treatment, CCRT. While such a comparison was beyond the scope of

the present analysis, future systematic reviews might aim to

include all three arms (NACT plus RS, RS alone and CCRT) to provide

a more direct elucidation of optimal management strategies. Some

studies have attempted such three-arm comparisons, albeit with

incomplete data for direct head-to-head comparisons (4,17).

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis highlights

the nuanced and, in some respects, inconclusive role of NACT

followed by RS for the treatment of LACC. While there appears to be

a borderline improvement in OS, the data do not demonstrate a

clear, statistically significant advantage for DFS when all

available studies are pooled. These findings are consistent with

broader uncertainties in the literature, where some individual

trials and meta-analyses reveal positive effects of NACT and others

show limited or no benefits compared with upfront surgery or

standard CCRT. Clinicians should interpret these results within the

broader clinical context, weighing patient factors such as tumor

bulk, performance status, comorbidities and treatment preferences.

NACT plus RS may offer a meaningful therapeutic alternative in

select populations or settings where radiotherapy resources are

limited, but it is not currently poised to replace CCRT as the

gold-standard treatment. Future well-designed randomized trials,

possibly incorporating biological or molecular markers of

chemosensitivity, may help refine patient selection and confirm or

refute the borderline OS advantage observed in the present

study.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This study was supported by the Lianyungang City Health

Technology Project (Lianyungang Municipal Health Commission; grant

no. 202407) and the Lianyungang City Cancer Prevention and

Treatment Science and Technology Development Project (Lianyungang

Anti-Cancer Association; grant no. MS202404).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

FW designed the present study, performed data

analysis and drafted the manuscript. FW collected data and

contributed to manuscript writing. RP assisted with data collection

and statistical analysis. FW and RP confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. YZ contributed to the data interpretation. YZ

provided technical support and revised the manuscript. RZ

supervised the study and reviewed the manuscript. YZ conceived the

study, provided overall supervision and finalized the manuscript.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript or

to generate images, and subsequently, the authors revised and

edited the content produced by the AI tools as necessary, taking

full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Mereu L, Pecorino B, Ferrara M, Tomaselli

V, Scibilia G and Scollo P: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radical

surgery in locally advanced cervical cancer: Retrospective

single-center study. Cancers (Basel). 15(5207)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

de Foucher T, Bendifallah S, Ouldamer L,

Bricou A, Lavoue V, Varinot J, Canlorbe G, Carcopino X, Raimond E,

Monnier L, et al: Patterns of recurrence and prognosis in locally

advanced FIGO stage IB2 to IIB cervical cancer: Retrospective

multicentre study from the FRANCOGYN group. Eur J Surg Oncol.

45:659–665. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Qiu J, Sun S, Liu Q, Fu J, Huang Y and Hua

K: A comparison of concurrent chemoradiotherapy and radical surgery

in patients with specific locally advanced cervical cancer (stage

IB3, IIA2, IIICr): Trial protocol for a randomized controlled study

(C-CRAL trial). J Gynecol Oncol. 34(e64)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Gadducci A and Cosio S: Neoadjuvant

chemotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer: Review of the

literature and perspectives of clinical research. Anticancer Res.

40:4819–4828. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Behtash N, Nazari Z, Ayatollahi H,

Modarres M, Ghaemmaghami F and Mousavi A: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

and radical surgery compared to radical surgery alone in bulky

stage IB-IIA cervical cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 32:1226–1230.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Chen H, Liang C, Zhang L, Huang S and Wu

X: Clinical efficacy of modified preoperative neoadjuvant

chemotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced (stage IB2 to

IIB) cervical cancer: Randomized study. Gynecol Oncol. 110:308–315.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Gong L, Zhang JW, Yin RT, Wang P, Liu H,

Zheng Y, Lou JY and Peng ZL: Safety and efficacy of neoadjuvant

chemotherapy followed by radical surgery versus radical surgery

alone in locally advanced cervical cancer patients. Int J Gynecol

Cancer. 26:722–728. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Katsumata N, Yoshikawa H, Kobayashi H,

Saito T, Kuzuya K, Nakanishi T, Yasugi T, Yaegashi N, Yokota H,

Kodama S, et al: Phase III randomised controlled trial of

neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radical surgery vs radical surgery

alone for stages IB2, IIA2, and IIB cervical cancer: A Japan

clinical oncology group trial (JCOG 0102). Br J Cancer.

108:1957–1963. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zhao H, He Y, Yang SL, Zhao Q and Wu YM:

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with radical surgery vs radical surgery

alone for cervical cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Onco Targets Ther. 12:1881–1891. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Cibula D, Raspollini MR, Planchamp F,

Centeno C, Chargari C, Felix A, Fischerová D, Jahnn-Kuch D, Joly F,

Kohler C, et al: ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of

patients with cervical cancer-update 2023. Int J Gynecol Cancer.

33:649–666. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Vizza E, Corrado G, Zanagnolo V, Tomaselli

T, Cutillo G, Mancini E and Maggioni A: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

followed by robotic radical hysterectomy in locally advanced

cervical cancer: A multi-institution study. Gynecol Oncol.

133:180–185. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zhang Y, Huang L, Wang D, Ren P, Hong Q

and Kang D: The ROBINS-I and the NOS had similar reliability but

differed in applicability: A random sampling observational studies

of systematic reviews/meta-analysis. J Evid Based Med. 14:112–122.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Namkoong SE, Park JS, Kim JW, Bae SN, Han

GT, Lee JM, Jung JK and Kim SJ: Comparative study of the patients

with locally advanced stages I and II cervical cancer treated by

radical surgery with and without preoperative adjuvant

chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 59:136–142. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Yang Z, Chen D, Zhang J, Yao D, Gao K,

Wang H, Liu C, Yu J and Li L: The efficacy and safety of

neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced

cervical cancer: A randomized multicenter study. Gynecol Oncol.

141:231–239. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kim HS, Kim JH, Chung HH, Kim HJ, Kim YB,

Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS and Kang SB: Significance of numbers of

metastatic and removed lymph nodes in FIGO stage IB1 to IIA

cervical cancer: Primary surgical treatment versus neoadjuvant

chemotherapy before surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 121:551–557.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ronsini C, Solazzo MC, Braca E, Andreoli

G, Vastarella MG, Cianci S, Capozzi VA, Torella M, Cobellis L and

De Franciscis P: Locally advanced cervical cancer: Neoadjuvant

treatment versus standard radio-chemotherapy-an updated

meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 16(2542)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Coutinho F, Gokhale M, Doran C, Monberg M,

Yamada KS and Chen L: Treatment patterns and outcomes among locally

advanced cervical cancer patients receiving concurrent

chemoradiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 41(e17511)2023.

|

|

19

|

Kenter GG, Greggi S, Vergote I, Katsaros

D, Kobierski J, van Doorn H, Landoni F, van der Velden J, Reed N,

Coens C, et al: Randomized phase III study comparing neoadjuvant

chemotherapy followed by surgery versus chemoradiation in stage

IB2-IIB cervical cancer: EORTC-55994. J Clin Oncol. 41:5035–5043.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Fu Y, Zhu T and Li H: Effectiveness of

cervical cancer therapy using neoadjuvant chemotherapy in

combination with radical surgery: A meta-analysis. Transl Cancer

Res. 6:228–237. 2017.

|