Introduction

The American Academy of Pediatrics (1) and the World Health Organization (WHO)

(2) recommend exclusive

breast-feeding for infants until the age of 6 months. A US national

survey conducted in 2001 reported that 33% of infants were

breast-fed and 17% were exclusively breast-fed until 6 months of

age (3). Breast-feeding is the

ideal feeding mode for both infants and mothers. Breast-feeding has

beneficial effects in infants and mothers, and it plays a crucial

role in public health (1). Human

milk is species-specific and contains optimal nutrients, growth

factors and the immunological components required for infants

(4). Breast-feeding has short-term

benefits such as the prevention of infectious diseases in infants,

including diarrhea (5–8), respiratory tract infection (9–12)

and otitis media (13,14). The long-term health benefits of

breast-feeding in infants include a lower risk of developing

diseases such as obesity (15,16),

hypertension (17,18) and type 1 diabetes mellitus

(19,20) in adulthood. Gluckman and Hanson

(21) proposed the concept of

developmental origins of health and disease, which states that

unbalanced nutrition in utero and in infancy leads to subsequent

disorders.

Body weight is an important index of infant growth

and development. Neonates lose weight because of the physiologic

extracellular fluid diuresis following their transition from

intrauterine to extrauterine life (22). The normal maximal weight loss is

5.5–6.6% of birth weight in optimally exclusively breast-fed

infants and occurs between the second and third day of life

(23,24). According to the WHO Multicentre

Growth Reference Study, a male infant gains 1,200 g/month and a

female infant gains 1,000 g/month under optimal conditions. Weight

gain in the first month of life in exclusively breast-fed infants

is reported to be 18–35 g (25,26).

Although studies indicate sufficient evidence regarding

breast-feeding, there is no universal agreement among healthcare

providers regarding weight gain in breast-fed and formula-fed

infants. When weight gain occurs gradually, appropriate support

should be provided after determining whether the infant is

demonstrating delayed weight gain or a failure to thrive (27–29).

This retrospective study aimed to clarify whether

differences in feeding modes influence neonatal weight gain in the

first month of life.

Materials and methods

Study population

This retrospective study involved the review of

pregnancy charts of 422 women who delivered at a birthing center in

Aomori Prefecture, Japan. The study complied with the principles of

the Declaration of Helsinki (Seoul 2008) and the ethical guidelines

for epidemiological research issued by the Ministry of Education,

Culture, Sports, Science and Technology as well as the Ministry of

Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan (2008). All study data were

obtained from the medical records of the subjects and were coded to

avoid disclosure of the their identity. We gathered the medical

records of 579 women who had a singleton pregnancy and delivered a

live infant from August 1998 to September 2007. The inclusion

criteria were low-risk, full-term pregnancy (duration, 37–42

weeks), spontaneous vaginal delivery, <500 ml intrapartum blood

loss and a healthy infant (1 min Apgar score of ≥8) who underwent a

health check-up at 1 month postpartum. Mothers with chronic

diseases (e.g., diabetes, hypertension and hyperthyroidism),

gestational diabetes, and pregnancy-induced hypertension were

excluded from the study. Records with unknown or missing obstetric

data were not included. A total of 422 records were finally

available for analysis.

Perinatal parameters

The perinatal parameters extracted from the

pregnancy charts were maternal age, parity, smoking status,

self-reported prepregnancy weight, prepregnancy body mass index

(BMI), gestational weight gain, chronic diseases, delivery mode,

duration of pregnancy, infant gender, infant size at birth (weight,

height, head circumference and chest circumference), 1 min Apgar

score, admission to hospital, and data from the first month health

check-up (mother’s weight, feeding mode and infant size).

Feeding modes

Subjects were divided into three groups on the basis

of self-reported feeding mode used by mothers in the first

postpartum month: an exclusive breast-feeding group, a

mixed-feeding (breast-feeding and formula-feeding) group, and an

exclusive formula-feeding group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS

software, version 16.0 (SPSS Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) for

Windows. Descriptive statistics are indicated as arithmetic mean ±

standard deviation. A two-sample t-test, one-way analysis of

variance, and Tukey’s honestly significant difference test were

performed to determine differences across the three groups. The

χ2 statistic was used to analyze categorical variables.

Univariate analysis was performed using Pearson’s correlation

coefficient. A P-value of <0.05 was determined to be indicative

of a statistically significant result.

Results

Summary of the study population

The maternal parameters of the study population are

summarized in Table I. The mean

maternal age was 26.6±4.5 years (range, 17–38 years); 38.6%

subjects were primiparas and 17.8% were smokers. The mean duration

of pregnancy was 39.5±1.2 weeks. The infant parameters of the study

population are summarized in Table

II. The mean infant birth weight and height were 3,209±370.4 g

and 49.6±1.8 cm, respectively; 49.8% infants were male. The mean

infant weight and height at 1 month were 4,513.2±451 g and 54.9±1.6

cm, respectively; the mean total weight gain was 1,303.5±325.0 kg,

and the weight gain/day was 39.5±9.4 g. The study population was

classified into the following three groups on the basis of the

feeding mode: breast-feeding (28.9%), mixed-feeding (55.9%) and

formula-feeding (15.2%) groups. The overall maternal smoking rate

was 17.8%, the smoking rates for the exclusive breast-feeding,

mixed feeding, and exclusive formula-feeding groups were 7.4, 20.3

and 28.1%, respectively. The smoking rate was significantly lower

in the exclusive breast-feeding group than in the other groups.

Except for maternal smoking status, none of the other maternal and

infant parameters significantly differed among the three feeding

modes.

| Table ISummary and comparison of maternal

parameters classified on the basis of feeding modes. |

Table I

Summary and comparison of maternal

parameters classified on the basis of feeding modes.

| | Feeding mode group

|

|---|

| Parameters | Total population

(n=422) | Breast-fed

(n=122) | Mixed-fed

(n=236) | Formula-fed

(n=64) |

|---|

| Age (years)a | 26.6±4.5 | 26.8±4.0 | 26.6±4.7 | 26.3±4.9 |

| Duration of pregnancy

(weeks)a | 39.5±1.2 | 39.5±1.1 | 39.6±1.2 | 39.2±1.1b |

| Primiparousc | 163 (38.6) | 44 (36.1) | 96 (40.7) | 23 (35.9) |

| Smokersc | 75 (17.8) | 9 (7.4) | 48 (20.3) | 18 (28.1)d |

| Prepregnancy weight

(kg)a | 53.3±8.4 | 52.4±6.8 | 53.7±9.3 | 54.0±7.5 |

| Prepregnancy

BMIa | 21.2±3.2 | 20.8±2.4 | 21.4±3.5 | 21.4±3.1 |

| Delivery weight | 65.2±8.7 | 64.2±7.4 | 65.7±9.2 | 65.3±8.9 |

| Gestational weight

gain (kg)a | 11.8±4.0 | 11.7±3.4 | 12.0±4.3 | 11.3±3.9 |

| Weight at 1 month

postpartum (kg)a | 57.9±8.3 | 57.0±7.2 | 58.4±8.9 | 57.6±8.1 |

| Postpartum weight

loss (kg)a | 7.3±2.3 | 7.2±2.1 | 7.3±2.3 | 7.7±2.6 |

| Table IISummary and comparison of infant

parameters classified on the basis of feeding modes. |

Table II

Summary and comparison of infant

parameters classified on the basis of feeding modes.

| | Feeding modes group

|

|---|

| Parameters | Total population

(n=422) | Breast-fed

(n=122) | Mixed-fed

(n=236) | Formula-fed

(n=64) |

|---|

| Malea | 210 (49.8) | 52 (42.6) | 126 (53.4) | 32 (50.0) |

| 1 min Apgar

scoreb | 9.8±0.4 | 9.8±0.4 | 9.8±0.4 | 9.7±0.5 |

| Birth | | | | |

| Weight (g)b | 3,209.0±370.4 | 3,203.6±319.6 | 3,222.3±402.5 | 3,170.6±337.6 |

| Height (cm)b | 49.6±1.8 | 49.6±1.6 | 49.7±2.0 | 49.5±1.7 |

| Head circumference

(cm)b | 33.4±1.3 | 33.3±1.3 | 33.5±1.3 | 33.3±1.2 |

| Chest circumference

(cm)b | 31.7±1.6 | 31.6±1.5 | 31.8±1.6 | 31.3±1.7 |

| At 1 month of

life | | | | |

| Weight (g)b | 4,513.2±451.8 | 4,504.2±447.8 | 4,525.3±470.3 | 4,485.5±390.4 |

| Height (cm)b | 54.9±1.6 | 54.8±1.5 | 55.0±1.8 | 54.8±1.3 |

| Head circumference

(cm)b | 37.1±1.1 | 37.2±1.0 | 37.2±1.1 | 37.4±1.4 |

| Chest

circumference (cm)b | 37.1±1.4 | 37.1±1.3 | 37.0±1.4 | 37.1±1.2 |

Relationship between weight gain and

maternal/neonatal parameters

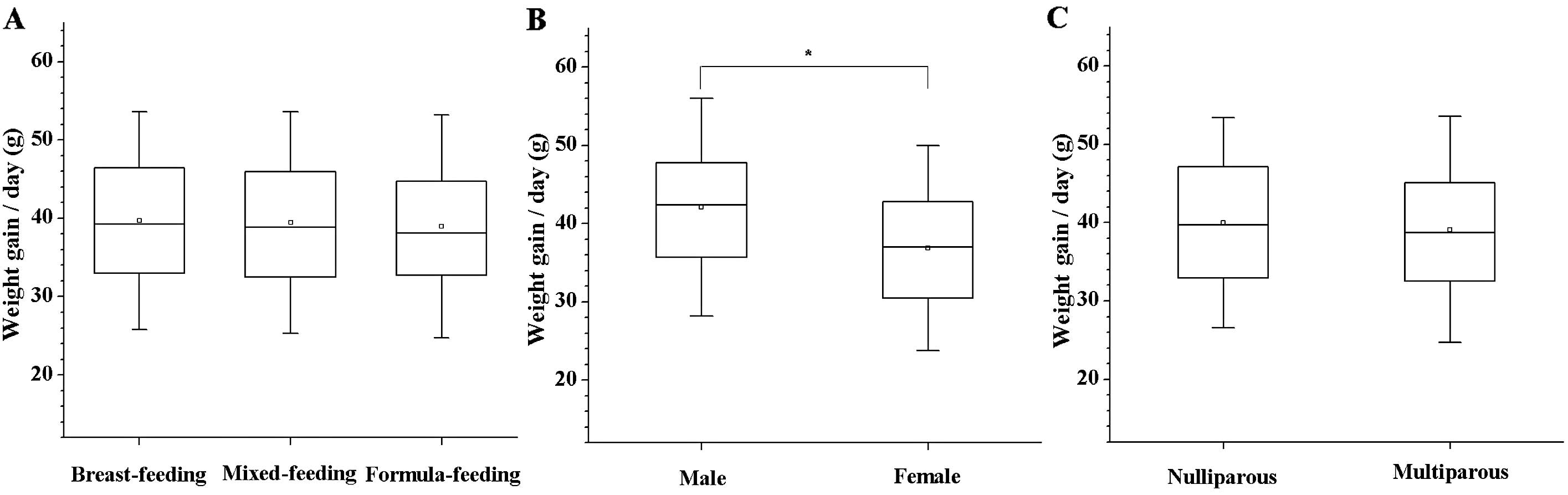

Infant weight gain/day in the first month of life

was determined for feeding modes, parity and infant gender

(Fig. 1). The daily weight gain

was 39.7±9.3 g (range, 18.5–67.4 g) in the exclusive breast-feeding

group, 39.5±9.4 g (range, 13.8–64.5 g) in the mixed-feeding group,

and 39.0±9.5 g (range, 14.4–65.3 g) in the exclusive

formula-feeding group. No significant differences in daily weight

gain were observed among the feeding modes (Fig. 1A). The daily infant weight gain was

significantly higher in the male infants (42.1±9.3 g) than in the

female infants (36.9±8.8 g) (Fig.

1B), but did not differ between primiparous and multiparous

mothers (Fig. 1C).

Multiple linear regression analysis was used to

identify independent variables associated with infant weight gain

(Table III). Although the

coefficient of determination (R2) was low, infant

gender, birth weight, birth height, and maternal age were

identified as variables that could independently predict the weight

gain/day in the first month of life (R2= 0.13,

P<0.001 by ANOVA).

| Table IIIMultiple linear regression analysis

for the association between infant weight gain/day and

maternal/infant parameters. |

Table III

Multiple linear regression analysis

for the association between infant weight gain/day and

maternal/infant parameters.

| Explanatory

variable | Standardized

partial regression coefficient (β) |

|---|

| Infant gender | −0.276a |

| Birth weight | −0.378a |

| Birth height | 0.255b |

| Maternal age | −0.119c |

Discussion

In Japan, breast-feeding has been promoted since

1989 according to a joint announcement ‘The Ten Steps to Successful

Breastfeeding’ released by WHO/UNICEF. According to a national

Japanese study in 2005, 42.4% infants aged 1 month, 38.0% aged 3

months, and 34.7% aged 6 months were exclusively breast-fed

(30). However, in our

retrospective study, 28.9% infants were exclusively breast-fed at 1

month after birth, indicating that the values in our study in Japan

were below the national average. The results obtained in the

present study were possibly affected by regional characteristics,

different attitudes, and/or lack of education on breast-feeding.

Moreover, relatively higher birth weights of both male (3,235 g)

and female (3,183 g) infants were observed in our study when

compared with the average birth weight in Japan (male infants,

3,040 g; female infants, 2,960 g) (31). This finding may be attributed to

the low-risk pregnancies, young maternal age, and high rate of

multiparity and full-term deliveries in our study. Except for the

rate of maternal smoking, which was lower in the exclusive

breast-feeding group than in other groups, none of the other

maternal and infant parameters assessed in this study significantly

differed among the three groups.

According to the WHO Multicenter Growth Reference

Study, a male infant gains 1,200 g/month and a female infant gains

1,000 g/month under optimal conditions (25). In the current study, the male

infants gained 1,391.1±328.4 g/month (42 g/day) and the female

infants gained 1,216.7±297.7 g/month (36.9 g/day). WHO (32) and Dewey (33) reported that male infants gain

significantly more weight than female infants. Breast-fed infants

weighed significantly less than formula-fed infants at ages 3

months to 2 years; however, no significant differences in weight

were observed at age 2–3 months (34–36).

The weight gained in the first month after birth did not differ

with the feeding modes; this finding was consistent with that of a

previous study (24). Exclusively

breast-fed infants may gradually gain weight in the first month of

life. However, delayed weight gain cannot be disregarded as it may

be associated with less than optimal breast-feeding or illness in

the infant (e.g., congenital heart disease, neuromuscular disease,

infection, or endocrine and metabolic abnormalities). Therefore,

infant weight gain assessments must take into account potential

illnesses in addition to maternal health, the condition of breast

milk, and infant position and latching during breast-feeding.

Furthermore, some infants gain less than 20 g/day regardless of the

feeding mode. Factors affecting the mother’s and infant’s health

after childbirth include abuse, parenting anxiety, and postpartum

depression; therefore, the mother’s physical and mental state

should be assessed along with the infant’s condition. Continuous

support provided to the mother and infant soon after discharge from

the hospital is related with improved health of both the mother and

her infant.

The present study revealed that weight gain in the

first month of life does not significantly differ between

exclusively breast-fed infants and exclusively formula-fed infants

(Fig. 1). Poor weight gain in

infants is not only caused by poor milk intake due to incorrect

suckling or insufficient lactation but may also be associated with

illness in the infant. Breast-feeding improves the health and

development of both the mother and infant. Therefore, assessment of

feeding soon after birth is crucial with regard to infant growth

and development and prevention of diseases in adulthood. Healthcare

providers working with mothers and infants should understand the

patterns of growth and development of exclusively breast-fed

infants, correctly assess the effectiveness of breast-feeding, and

provide continuous support so that both the mother and infant

benefit from breast-feeding.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the midwives of

Fukushi Birth Center for collecting the pregnancy charts. This

study was supported by a Grant for Hirosaki University

Institutional Research (2011).

References

|

1

|

American Academy of Pediatrics:

Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 115:196–506.

2005.

|

|

2

|

WHO: Global Strategy for Infant and Young

Child Feeding 55th World Health Assembly. World Health

Organization; Geneva: 2002

|

|

3

|

Ryan AS, Wenjun Z and Acosta A:

Breastfeeding continues to increase into the new millennium.

Pediatrics. 110:1103–1109. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Prentice A: Constituents of human milk.

Food and Nutrition Bulletin. United Nations University Press; pp.

171996, http://archive.unu.edu/unupress/food/8F174e/8F174E04.htmuri.

Accessed December 27, 2011.

|

|

5

|

Howie PW, Forsyth JS, Ogston SA, Clark A

and Florey CD: Protective effect of breast feeding against

infection. BMJ. 300:11–16. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Clemens J, Rao M, Ahmed F, et al:

Breast-feeding and the risk of life-threatening rotavirus diarrhea:

prevention or postponement? Pediatrics. 92:680–685. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lopez-Alarcon M, Villalpando S and Fajardo

A: Breast-feeding lowers the frequency and duration of acute

respiratory infection and diarrhea in infants under six months of

age. J Nutr. 127:436–443. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Bhandari N, Bahl R, Mazumdar S, Martines

J, Black RE and Bhan MK; Infant Feeding Study Group: Effect of

community-based promotion of exclusive breastfeeding on diarrhoeal

illness and growth: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Lancet.

361:1418–1423. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Blaymore Bier J, Oliver T, Ferguson A and

Vohr BR: Human milk reduces outpatient upper respiratory symptoms

in premature infants during their first year of life. J Perinatol.

22:354–359. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bachrach VR, Schwarz E and Bachrach LR:

Breastfeeding and the risk of hospitalization for respiratory

disease in infancy: a meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.

157:237–243. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chantry CJ, Howard CR and Auinger P: Full

breastfeeding duration and associated decrease in respiratory tract

infection in US children. Pediatrics. 117:425–432. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Martinez FD, Morgan

WJ and Taussig LM: Breast feeding and lower respiratory tract

illness in the first year of life. Group Health Medical Associates.

BMJ. 299:946–949. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Owen MJ, Baldwin CD, Swank PR, Pannu AK,

Johnson DL and Howie VM: Relation of infant feeding practices,

cigarette smoke exposure, and group child care to the onset and

duration of otitis media with effusion in the first two years of

life. J Pediatr. 123:702–711. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Aniansson G, Alm B, Andersson B, et al: A

prospective cohort study on breast-feeding and otitis media in

Swedish infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 13:183–188. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Von Kries R, Koletzko B, Sauerwald T, et

al: Breast feeding and obesity: cross sectional study. BMJ.

319:147–150. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Owen CG, Martin RM, Whincup PH, Smith GD

and Cook DG: Effect of infant feeding on the risk of obesity across

the life course: a quantitative review of published evidence.

Pediatrics. 115:1367–1377. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Singhal A, Cole TJ and Lucas A: Early

nutrition in preterm infants and later blood pressure: two cohorts

after randomised trials. Lancet. 357:413–419. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Horta BL, Bahl R, Martinés JC and Victora

CG: Evidence on the long-term effects of breastfeeding: Systematic

reviews and meta-analysis. World Health Organization; Geneve: pp.

522007

|

|

19

|

Virtanen SM, Räsänen L, Aro A, et al:

Infant feeding in Finnish children less than 7 yr of age with newly

diagnosed IDDM. Childhood Diabetes in Finland Study Group. Diabetes

Care. 14:415–417. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Gerstein HC: Cow’s milk exposure and type

I diabetes mellitus. A critical overview of the clinical

literature. Diabetes Care. 17:13–19. 1994.

|

|

21

|

Gluckman P and Hanson M: The conceptual

basis for the developmental origins of health and disease.

Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. Cambridge University

Press; Camdridge: pp. 33–50. 2006, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, et al:

The newborn infant. Williams Obstetrics. Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ

and Bloom S: 23rd edition. McGraw-Hill; New York: pp. 590–604.

2010

|

|

23

|

Rodríguez G, Ventura P, Samper MP, Moreno

L, Sarría A and Pérez-González JM: Changes in body composition

during the initial hours of life in breast-fed healthy term

newborns. Biol Neonate. 77:12–16. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

MacDonald PD, Ross SR, Grant L and Young

D: Neonatal weight loss in breast and formula fed infants. Arch Dis

Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 88:F472–F476. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

WHO: Evidence for the ten steps to

successful breastfeeding. World Health Organization; Geneva:

1999

|

|

26

|

UNICEF-World Health Organization:

Breastfeeding Management and Promotion in a Baby-Friendly Hospital:

an 18-hour course for maternity staff. UNICEF; New York: 1993

|

|

27

|

Mohrbancher N and Stock JMA: The

Breastfeeding Answer Book. La Leche League International; Illinois:

pp. 147–178. 2003

|

|

28

|

Lawrence RA and Lawrence RM:

Breastfeeding; A Guide for the Medical Profession. Mosby; St.

Louis: pp. 427–460. 2005

|

|

29

|

Regina E and Giugliani J: Slow weight gain

and failure to thrive. Core Curriculum for Lactation Consultant

Practice. 2nd edition. Mannel R, Martens P and Walker M: Jones and

Bartlett Publishers; Boston: pp. 727–740. 2007

|

|

30

|

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

(http://www.mhlw.go.jp/) Japan: Summary of the results of a

nutrition survey in infants in FY2005, Breast-feeding division

(updated 2006 Jun 29). Available at http://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2007/03/dl/s0314-17b-1.pdfuri

(In Japanese). Accessed December 27, 2011.

|

|

31

|

Health, Labour and Welfare Statistics

Association. Journal of Health and Welfare Statistics.

58:482011.(In Japanese).

|

|

32

|

World Health Organization: The WHO

Multicentre Growth Reference Study. http://www.who.int/childgrowth/mgrs/en/uri.

Accessed December 27, 2011.

|

|

33

|

Dewey KG: Nutrition, growth, and

complementary feeding of the breastfed infant. Pediatr Clin North

Am. 48:87–104. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Dewey KG, Heinig MJ, Nommsen LA, Peerson

JM and Lönnerdal B: Growth of breast-fed and formula-fed infants

from 0 to 18 months: the DARLING Study. Pediatrics. 89:1035–1041.

1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kramer MS, Guo T, Platt RW, Vanilovich I,

et al: The promotion of breastfeeding intervention trials study

group. Feeding effects on growth during infancy. J Pediatr.

145:600–605. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Dewey KG: Infant feeding and growth. Adv

Exp Med Biol. 639:57–66. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|