Introduction

Ameloblastoma is an odontogenic epithelial neoplasm

that may originate from the enamel organ, remnants of the dental

lamina, epithelium of dentigerous cysts, or possibly from the basal

cells of the oral mucosa epithelium (1). Although the lesion is histologically

benign, this neoplasm behaves as a slow-growing invasive tumor.

Usually the tumor remains asymptomatic until it reaches a large

enough size to provoke expansion and perforation of the adjacent

soft tissue, at which point the patient may perceive its existence

(2).

Ameloblastomas account for ∼1% of all jaw tumors and

cysts (3). They appear between

30–40 years of age, except in the unicystic variety which usually

appear prior to the age of 30 (4).

In >80% of cases ameloblastomas present as an intraosseous

neoformation in the mandible, particularly in the molar area or the

ascending ramus (5). Since 1992

the World Health Organization has accepted three subtypes of benign

ameloblastomas: solid/multicystic, unicystic and

extraosseous/peripheral (6). The

most common subtype is multicystic, representing >80% of cases

including the follicular, plexiform, acanthomatous and granular

types. Since 2005, two new subtypes have been added to the

classification: desmoplastic and mixed (with areas of desmoplastic

and solid pattern). The unicystic type also comprises mural,

luminal and intraluminal ameloblastoma arising in dentigerous

cysts. Diagnosis is based on imaging examinations (panoramic

radiography, CT and MRI) and histopathological studies by means of

a biopsy. Radiographically, multicystic ameloblastomas usually

present as multilocular radiolucent images in ‘soap bubbles’

(7). In more than half of cases

associated with impacted teeth, unicystic ameloblastomas appear as

well-defined radiolucent images, with a scalloped or lobed edge.

Therefore the tumors are visualized around the tooth crown, similar

to that observed in dentigerous cysts (6).

Treatment of these neoplasms remains a matter of

debate due to their locally aggressive behavior and high rate of

recurrence following treatment (8). The therapeutic challenge is to

achieve a complete lesion excision with the least possible

morbidity. For this purpose the surgeon is required to assess the

location, size and subtype of the ameloblastoma, as well as age of

the patient. A number of different treatment strategies have been

previously reported including local techniques (curettage,

enucleation or marsupialization) or radical treatments (marginal or

en-bloc segmental resection with safety margins and reconstruction

of bone defect) (2,4,8,9–11).

Solid/multicystic ameloblastomas have been identified as the most

aggressive subtype, with a high recurrence rate following local

excision. By contrast, unicystic ameloblastomas are described to

have a lower rate of recurrence and enucleation, with curettage

potentially being sufficient for their management. Local treatment

has an increased risk of recurrence, therefore it may be

complemented with further application of Carnoy's solution,

cryotherapy or diathermy in order to reduce the recurrence rate

(12). Peripheral ameloblastomas

occur in the gingiva or alveolar mucosa and usually respond well to

local treatment. The purpose of this study was to analyze the

therapeutic results obtained from a series of patients with

mandibular ameloblastomas and to specifically focus attention on

evaluating the surgical management of recurrent ameloblastoma.

Materials and methods

A retrospective study was performed on 31 patients

with mandibular ameloblastomas, treated at the Department of Oral

and Maxillofacial Surgery, ‘Virgen del Rocío’ University Hospital

of Seville, Spain, between 2000 and 2010. The patients included 17

men and 14 women, aged between 13–82 years at the time of the

initial diagnosis (mean age 43.1 years). Patients with at least one

positive ameloblastoma biopsy and who were undergoing surgery were

included in the present study. Therapeutic modalities were divided

into enucleation, curettage, marginal mandibulectomy, segmental

mandibulectomy and mandibulectomy with reconstruction. Enucleation

(with or without curettage) involves tumoral removal and avoidance

of neoplasm spillage. Marginal mandibulectomy consists of an ‘en

bloc’ resection of the tumor with a safety margin of 1 cm of the

adjacent bone, and sometimes the adjacent periosteum may be invaded

by the tumor. Segmental resection suggests a discontinuity defect

of the mandible. Reconstructive surgery of the mandible may be

performed with a bone graft or a free flap with or without

subsequent placement of dental implants. Initial surgical treatment

consisted of enucleation and curettage (26 patients), marginal

mandibulectomy (4 patients) and segmental mandibulectomy (1

patient).

The data collected included age, gender, tumor

location, histological findings, initial treatment, number of

recurrences, year of recurrence onset, surgical treatment option,

reconstruction and follow-up. Follow-up was performed by routine

annual clinical and radiographic examination by panoramic

radiograph and CT. Recurrent ameloblastoma was defined as a relapse

after a minimum disease free period of 1 year following initial

surgery. Due to the small number of patients enrolled, no

statistical analysis was performed.

Results

In the 10-year period studied, 31 patients underwent

surgery for mandibular ameloblastomas. This included 17 men and 14

women, aged 13–82 years at the time of the initial diagnosis (mean

age 43.1 years). Sixteen of the 31 patients were under 40 years of

age at the time of diagnosis. Multicystic pattern predominated in

26 patients (83.9%), and 5 patients (16.1%) exhibited unicystic

pattern. Tumors were located in the molar region of the mandibular

body in 16 cases (51.6%), 11 cases affected the ramus and angle

(35.5%), and in 4 cases, the anterior and premolar areas were

involved (12.9%).

Initial surgical treatment involved enucleation and

curettage (26 patients), marginal mandibulectomy (4 patients) and

segmental mandibulectomy (1 patient). Nine patients (29%) presented

tumor recurrence subsequent to the first surgery. In the 31

patients, a total of 40 surgical procedures were performed,

including 26 enucleations and curettages (65%), 9 marginal

mandibulectomies (22.5%) and 5 segmental mandibulectomies (12.5%).

Primary bone reconstruction was performed in 10 cases: five

cancellous bone grafts obtained from proximal tibia, three cortical

non-vascularized iliac bone grafts, one iliac crest bone graft and

one vascularized fibula free flap were harvested. In the oldest

patient (82 years of age), the mandibular continuity defect was

reconstructed with a single titanium reconstruction plate. In cases

where a segmental resection was performed patients showed permanent

anesthesia of the lower lip.

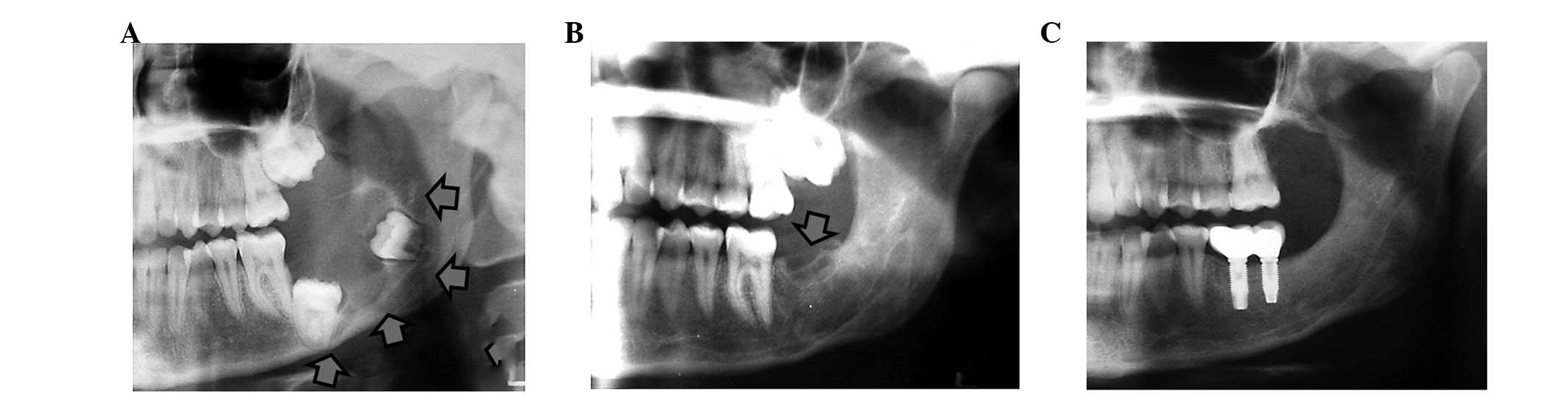

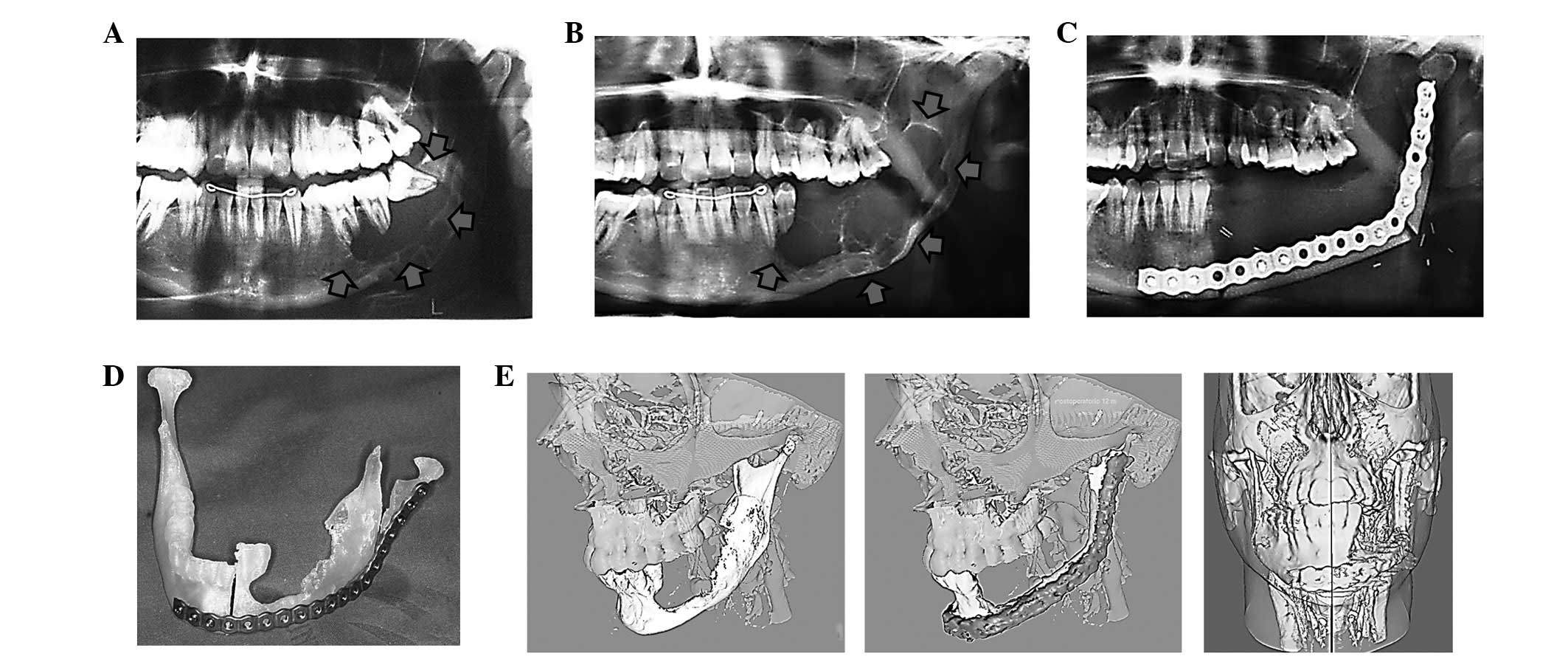

The group of patients with recurrent ameloblastomas

comprised 2 men and 7 women (mean age of 36.1 years at the time of

recurrence). Initial diagnosis was multicystic ameloblastoma in 6

cases and unicystic ameloblastoma in 3 cases. Initial procedures

consisted of curettage in 5 cases, and enucleation and curettage in

the remaining 4 cases. Recurrences were detected at 32 months on

average following initial treatment and were surgically treated by

means of marginal mandibulectomies (5 cases) and segmental

mandibulectomies (4 cases) (Figs.

1–3). In 6 cases, bone

reconstruction was performed primarily (3 patients with cortical

iliac crest grafts, 1 patient with cancellous iliac crest bone

graft, 1 patient with proximal tibia bone graft and 1 patient with

fibula free flap). No further recurrences were observed after the

second operation. In 3 patients dental implants were placed

posteriorly and implant-supported fixed prosthesis were

constructed. Three-dimensional reconstruction of preoperative

planning and outcome following surgical treatment was performed

using AYRA software (formerly VirSSPA, Andalusian Health Service,

Seville, Spain) (Fig. 3E).

Discussion

Mandibular ameloblastoma management remains a

subject of debate. The preferred treatment is surgical excision.

However, there is no unanimous consensus with regards to the extent

and type of surgery. While the main objective remains to achieve a

complete resection, in order to prevent tumor recurrence, the focus

of various investigations has been on how to achieve this without

performing a disproportionate surgery, for which it is necessary to

assess the location, size and type of ameloblastoma, as well as the

age of the patient. Currently, conservative local treatment appears

to be acceptable in young, growing patients, in order to minimize

the psychological impact of an aggressive resection and future

functional or growth problems, and in elderly patients to avoid

major surgical complications. It is also acceptable in unicystic

luminal ameloblastomas, if the tumor has not spread beyond the

basement membrane of the cyst, and in those lesions treated without

a previously accurate diagnosis (6). Extensive surgical treatment is

recommended in large or aggressive ameloblastomas (multicystic)

with evidence of cortical bone infiltration or soft tissue

extension (13,14).

The sample of 31 ameloblastomas used in the present

study reproduce the relatively uniform documented data previously

reported with regards to epidemiology, clinical features, treatment

and outcomes (4,15–17).

The mandibular molar region was the most common location and, in

terms of patient age, the group fell within the age ranges reported

in the literature. Surgical treatment consisted of conservative

treatment in 65% of cases and an en-bloc bone resection (marginal,

22.5% and segmental, 12.5%) in the remaining cases. In accordance

with the literature, a more conservative approach to unicyst

lesions, which could be treated with simple enucleation and/or

curettage, was preferred in young patients (18). In solid and multicystic

ameloblastomas we followed the procedure recommended most in the

literature, i.e., radical resection including a healthy bone margin

of at least 1 cm (19–21).

Recurrence after initial surgical treatment is the

result of the infiltrative growth of the ameloblastoma through the

adjacent bone, responsible for the local bone cancellous invasion

beyond the radiographically visible margins. To a large extent,

recurrence is the result of performing an inadequate initial

procedure. The recurrence rate should be assessed in a large

sample, during a prolonged postoperative period, and varies with

regard to location, tumor histology and radicality of the surgical

resection. Kim and Jang (22) and

Escande et al (2) reported

an overall recurrence rate of 21.1% and 45%, respectively. In the

present study, the overall rate of recurrence was 29%. Hong et

al (20), in a retrospective

analysis of 239 patients with ameloblastomas, reported a recurrence

rate of 4.5% after treatment by segmental resection or

maxillectomy, 11.6% after marginal resection and 29.3% after

conservative treatment (enucleation, curettage and

marsupialization), obtaining a statistically significant

correlation between method of treatment and recurrence. Attempts

have been made to use various markers to differentiate the types of

ameloblastoma and prevent recurrences, although this has not yet

yielded encouraging results (23).

At present, the prognosis of recurrence appears to be associated

with the surgical planning prior to evaluation of the histological

subtype (1,17,21).

In our study, all ameloblastomas that recurred had initially

undergone local procedures regardless of type of ameloblastoma.

Radical and aggressive surgery is the preferred

option for recurrent ameloblastoma management (4,7,21).

This method supports that the mandibular resection should be at

least 1–2 cm beyond the radiological limit to ensure that all

microlesions are removed (7). In 4

cases a radical treatment option, by means of a segmental

mandibulectomy, was selected due to aggressive features (cortical

bone perforation, tumor extension, infiltration of the dental

nerve, and multicystic type). In all other cases a marginal

mandibulectomy was selected, taking into account the preservation

of surrounding anatomical structures including dental nerve and

basal mandibular cortex.

Mandibular reconstruction is necessary following

tumor resection resulting in severe defects of mandibular arch

continuity and sacrifice of teeth. Basic reconstruction involves

the use of non-vascularized bone grafts together with restoration

of lost teeth by means of dental implants and implant-supported

prostheses (13,24,25).

In 3 cases presenting with <5 cm mandibular segmental defect,

reconstruction was achieved using a non-vascularized iliac crest

graft. By contrast, in cases where bone resection results in a

severe defect of continuity, reconstruction using a

micro-vascularized free flap is required (26,27).

In the present study, an 8 cm defect involving the body, angle and

ramus of the mandible was reconstructed using a fibula free flap.

Surgical planning in this particular case was performed using the

software VirSSPA AYRA based on the images from CT angiography,

which allowed creation of a preoperative stereolithographic model

to shape the titanium plate and perform the virtual surgical

simulation of bone resection. A template, made using rapid

prototyping technology, was used to carry out the fibula

osteotomies (28). In marginal

mandibulectomies bone regeneration can be expected following

preservation of the mandibular basal cortex, particularly in young

patients. In 2 patients a cancellous graft, obtained from the

proximal tibia and iliac crest respectively, was used to restore

the bone defect following a marginal mandibulectomy. In 3 cases,

restoration of missing teeth was achieved by secondary dental

implant placement in the bone grafts and by using implant-supported

prostheses. Previous studies have demonstrated the advantages of

implant placement and subsequent restoration with prostheses for

the rehabilitation of oral competence, mastication, speech and

facial contour in patients with mandibular defects (25,29,30).

In conclusion, ameloblastoma is a benign, locally

invasive odontogenic tumor with a high rate of long-term recurrence

associated with an inappropriate initial therapeutic approach. When

detecting tumor recurrence, the ideal treatment method is bone

resection with a safety margin of at least 1 cm beyond the

radiographically visible margins. This may be performed by either

marginal or segmental mandibulectomy depending on the location and

extent of recurrence. Immediate reconstruction of the bone defect

with free grafts or flaps, placement of dental implants and

rehabilitation with implant-supported prostheses in a second stage

can improve jaw function and facial harmony of the patient.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge

CIBER-BBN, an initiative funded by the VI National R&D&i

Plan 2008–2011, Iniciativa Ingenio 2010, Consolider Program, CIBER

Actions and financed by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III with

assistance from the European Regional Development Fund.

References

|

1.

|

Ghandhi D, Ayoub AF, Pogrel MA, MacDonald

G, Brocklebank LM and Moos KF: Ameloblastoma: a surgeon's dilemma.

J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 64:1010–1014. 2006.

|

|

2.

|

Escande C, Chaine A, Menard P, et al: A

treatment algorithm for adult ameloblastomas according to the

Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital experience. J Craniomaxillofac Surg.

37:363–369. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Torres-Lagares D, Infante-Cossio P,

Hernandez-Guisado JM and Gutiérrez-Pérez JL: Mandibular

ameloblastoma. A review of the literature and presentation of six

cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 10:231–238. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Fregnani ER, da Cruz Perez DE, de Almeida

OP, Kowalski LP, Soares FA and de Abreu Alves F:

Clinicopathological study and treatment outcomes of 121 cases of

ameloblastomas. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 39:145–149. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Varkhede A, Tupkari JV and Sardar M:

Odontogenic tumors: a study of 120 cases in an Indian teaching

hospital. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 16:e895–e899. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Black CC, Addante RR and Mohila CA:

Intraosseous ameloblastoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral

Radiol Endod. 110:585–592. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Becelli R, Morello R, Renzi G, Matarazzo G

and Dominici C: Treatment of recurrent mandibular ameloblastoma

with segmental resection and revascularized fibula free flap. J

Craniofac Surg. 22:1163–1165. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Junquera L, Ascani G, Vicente JC,

Garcia-Consuegra L and Roig P: Ameloblastoma revisited. Ann Otol

Rhinol Laryngol. 112:1034–1039. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Chaine A, Pitak-Arnnop P, Dhanuthai K,

Ruhin-Poncet B, Bertrand JC and Bertolus C: A treatment algorithm

for managing giant mandibular ameloblastoma: 5-year experiences in

a Paris university hospital. Eur J Surg Oncol. 35:999–1005.

2009.

|

|

10.

|

Pogrel MA and Montes DM: Is there a role

for enucleation in the management of ameloblastoma? Int J Oral

Maxillofac Surg. 38:807–812. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Sammartino G, Zarrelli C, Urciuolo V, et

al: Effectiveness of a new decisional algorithm in managing

mandibular ameloblastomas: a 10-years experience. Br J Oral

Maxillofac Surg. 45:306–310. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Mendenhall WM, Werning JW, Fernandes R,

Malyapa RS and Mendenhall NP: Ameloblastoma. Am J Clin Oncol.

30:645–348. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Mareque Bueno J, Mareque Bueno S, Pamias

Romero J, Bescos Atin MS, Huguet Redecilla P and Raspall Martin G:

Mandibular ameloblastoma. Reconstruction with iliac crest graft and

implants. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 12:E73–E75.

2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Belli E, Rendine G and Mazzone N:

Ameloblastoma relapse after 50 years from resection treatment. J

Craniofac Surg. 20:1146–1149. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Eckardt AM, Kokemüller H, Flemming P and

Schultze A: Recurrent ameloblastoma following osseous

reconstruction - a review of twenty years. J Craniomaxillofac Surg.

37:36–41. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Tamme T, Soots M, Kulla A, et al:

Odontogenic tumors, a collaborative retrospective study of 75 cases

covering more than 25 years from Estonia. J Craniomaxillofac Surg.

32:161–165. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Hertog D, Bloemena E, Aartman IH and van

der Waal I: Histopathology of ameloblastoma of the jaws; some

critical observations based on a 40 years single institution

experience. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 17:e76–e82.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Carlson ER and Marx RE: The ameloblastoma:

primary, curative surgical management. J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

64:484–494. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Nakamura N, Mitsuyasu T, Higuchi Y, Sandra

F and Ohishi M: Growth characteristics of ameloblastoma involving

the inferior alveolar nerve. A clinical and histopathologic study.

Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 91:557–562. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Hong J, Yun PY, Chung IH, et al: Long-term

follow up on recurrence of 305 ameloblastoma cases. Int J Oral

Maxillofac Surg. 36:283–288. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21.

|

Hertog D, Schulten EA, Leemans CR, Winters

HA and Van der Waal I: Management of recurrent ameloblastoma of the

jaws; a 40-year single institution experience. Oral Oncol.

47:145–146. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22.

|

Kim SG and Jang HS: Ameloblastoma: a

clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic analysis of 71 cases.

Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 91:649–653. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Coleman H, Altini M, Ali H, Doglioni C,

Favia G and Maiorano E: Use of calretinin in the differential

diagnosis of unicystic ameloblastomas. Histopathology. 38:312–317.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Nakamura N, Higuchi Y, Mitsuyasu T, Sandra

F and Ohishi M: Comparison of long-term results between different

approaches to ameloblastoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral

Radiol Endod. 93:13–20. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25.

|

Chiapasco M, Colletti G, Romeo E, Zaniboni

M and Brusati R: Long-term results of mandibular reconstruction

with autogenous bone grafts and oral implants after tumor

resection. Clin Oral Implants Res. 19:1074–1080. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Chana JS, Chang YM, Wei FC, et al:

Segmental mandibulectomy and immediate free fibula

osteoseptocutaneous flap reconstruction with endosteal implants: an

ideal treatment method for mandibular ameloblastoma. Plast Reconstr

Surg. 113:80–87. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27.

|

Zemann W, Feichtinger M, Kowatsch E and

Kärcher H: Extensive ameloblastoma of the jaws: surgical management

and immediate reconstruction using microvascular flaps. Oral Surg

Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 103:190–196. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28.

|

Infante-Cossio P, Gacto-Sanchez P,

Gomez-Cia T and Gomez-Ciriza G: Stereolithographic cutting guide

for fibula osteotomy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol.

113:712–713. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29.

|

Chiapasco M, Abati S, Ramundo G, Rossi A,

Romeo E and Vogel G: Behaviour of implants in bone grafts or free

flaps after tumor resection. Clin Oral Implants Res. 11:66–75.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30.

|

Tözüm TF, Sönmez E, Askin SB, Tulunoglu I

and Safak T: Implant stability and peri-implant parameters in free

vascularized iliac graft transplantation patients: report of three

ameloblastoma cases. J Periodontol. 82:329–335. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|