Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) has been reported as the

third most common cancer type and the fourth most common cause of

cancer-associated death worldwide, affecting ~1.2 individuals and

leading to 600,000 deaths per year (1,2). The

mortality of patients with CRC has decreased in a number of

countries over the last decade, which is thought to be attributed

to increased CRC screening and decreased prevalence of risk

factors, as well as the development and implementation of novel

treatments (3). However, 50% of

patients still develop metastasis and eventually succumb to their

disease, and most of them develop psychological conditions at

varying degrees, including anxiety and depression, and present with

poor quality of life (QoL) due to the psychological burden

associated with cancer diagnosis, the pain and the side effects of

therapy (4,5). For patients with CRC, chemotherapy is

able to decrease the recurrence risk and prolong survival to a

certain extent, but most patients experience complications

including pain and diarrhea; furthermore, CRC may be associated

with a significant economic burden. Hence, the emotional state and

social life of the patients (and their family) is frequently

negatively affected, thereby leading to the occurrence of anxiety

and depression (6,7). Previous studies have estimated the

occurrence of post-surgical anxiety and depression in patients with

CRC to be 8–23 and 16–39%, respectively (5,8–10). Therefore, it is necessary to explore

strategies to decrease anxiety/depression and improve or maintain

good QoL in patients with CRC.

Care intervention has been considered a common and

efficacious method to ameliorate the adverse effects of carcinoma

and its treatment, and is usually designed to promote improvements

in physical and mental health (11).

A large number of studies have confirmed the favorable effect of

care intervention, including patients' health education, dietary

patterns and physical activity on the functional outcomes in

patients with CRC; however, most of them focus on the functional

outcomes in these patients, while the effect of care intervention

on the prognosis of patients with CRC remains to be determined,

particularly regarding psychosocial problems and QoL (12,13).

Although parts of Chinese clinical trials have revealed the

efficacy of intervention care in improving mental health issues

including anxiety and depression in CRC patients, the role of the

care intervention in patients with CRC receiving adjuvant

chemotherapy remains elusive (14,15). In

addition, most of these previous studies have been performed on

relatively small cohorts, and additional studies with a larger

sample size for validation are urgently required. Considering the

aforementioned points, an incremental patient care program (IPCP)

was designed, consisting of patient health education, physical

exercise, telephone counselling, regular examination as well as

care activities, and the purpose of the present study was to assess

the effects of IPCP on anxiety, depression and QoL in patients with

CRC receiving adjuvant chemotherapy.

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 298 consecutive patients with CRC who

underwent surgery at the 2nd Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical

University (Harbin, China) between January 2014 and December 2016

were recruited for the present randomized, controlled study. The

inclusion criteria were as follows: a) Diagnosis of primary CRC

confirmed by clinicopathologic examinations; b) age of 18–80 years;

c) tumor-nodes-metastasis (TNM) stage, II or III; d) scheduled for

CRC resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy; e) prognosis of

survival for at least 12 months; and f) ability to complete the

anxiety, depression and QoL assessments. The exclusion criteria

were as follows: a) Neoadjuvant therapies; b) intake of

anti-depressant or anti-anxiety medication within the past 3

months; c) a comorbidity of severe primary mental disorder, or

severe liver or renal disease; d) history of other malignant tumor

types or hematological malignancy; e) no availability for regular

follow-up; f) pregnancy or lactation; g) refusal to provide written

informed consent. The reasons for the collection of data over a

long period (from January 2014 to December 2016) were as follows:

First, at our hospital, numerous patients were diagnosed at the

early stage and did not require adjuvant chemotherapy, and certain

patients at the advanced stage received neoadjuvant therapy; thus,

a considerable proportion of patients were not eligible for the

present study. Furthermore, 300 patients were required to reach

sufficient statistical power, and it took this long until the

number of eligible consecutive patients collected reached this

number. In addition, at the preliminary stage, a total of 625

patients were invited to participate in the present study, but a

considerable amount were excluded due to not satisfying the

inclusion or exclusion criteria. There were 5 patients with severe

depressive disorder and 11 patients with severe anxiety disorder

who were excluded, and these patients received psychotherapy, but

no anti-depressant or anti-anxiety medicines.

Randomization

In the present randomized, controlled study, a

blocked randomization method was adopted, and a randomization code

was generated using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) 9.3 software

(SAS Institute, Carey, NC, USA). The randomization was performed by

an independent statistical analyst who was otherwise not involved

in the study, and the documents were deposited at the medical and

statistical service company Shanghai Qeejen Biotech Co. (Shanghai,

China). When a patient was eligible for the study, a call was made

to Qeejen Biotech Co. and a unique subject identification number

was provided from the randomizing module.

Adjuvant chemotherapy

At 2–6 weeks following CRC resection, all patients

received adjuvant chemotherapy based on their disease condition.

For patients with TNM stage II, according to risk stratification

and T stage, one of the following adjuvant chemotherapy regimens

was selected: i) Capecitabine 1,250 mg/m2 twice daily on

days 1–14, repeated every 3 weeks for a total of 24 weeks; ii)

leucovorin (LV) 400 mg/m2 over 2 h on day 1, followed by

a 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) bolus 400 mg/m2 and then 1,200

mg/m2/day for 2 days (a total continuous infusion of

2,400 mg/m2 over 46–48 h), repeated every 2 weeks for a

total of 24 weeks; iii) oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2

intravenously (IV) over 2 h on day 1 and capecitabine 1,000

mg/m2 twice daily on days 1–14, repeated every 3 weeks

for a total of 24 weeks; iv) oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 IV

over 2 h on day 1, LV 400 mg/m2 IV over 2 h on day 1,

5-FU 400 mg/m2 IV bolus on day 1 and then 1,200

mg/m2/day for 2 days (total 2,400 mg/m2 over

46–48 h) continuous infusion, repeated every 2 weeks for a total of

24 weeks. For patients with TNM stage III, one of following

adjuvant chemotherapy regimens was selected: i) Oxaliplatin 130

mg/m2 IV over 2 h, day 1, capecitabine 1,000

mg/m2 twice daily on days 1–14, repeated every 3 weeks

for a total of 24 weeks; ii) oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 IV

over 2 h on day 1, LV 400 mg/m2 IV over 2 h on day 1,

5-FU 400 mg/m2 IV bolus on day 1, then 1,200

mg/m2/day for 2 days (a total continuous infusion of

2,400 mg/m2 over 46–48 h) repeated every 2 weeks for a

total of 24 weeks.

Interventions

After randomization, patients were randomly assigned

to the IPCP group or the control group in a 1:1 ratio. In the IPCP

group, patients received IPCP and conventional care, whereas in the

control group, patients received only conventional care, which

included instructions of post-operative medicine management,

regular examinations (every 3 months) and usual advice regarding

post-operative rehabilitation. The intervention was performed for

six months. The details of IPCP were as follows (Table I): i) Patient health education: Over

the first 2 weeks, patients were provided with general health

education materials, including information about nutrition,

physical activity and mental health care. Furthermore,

comprehensive health education was provied by a designated research

therapist, and detailed instruction was given once every two months

for six months. ii) Physical exercise: Over the first 3 months,

patients participated in low-intensity physical exercise comprised

of three components: Relaxation (30 min five times a week), body

awareness and restorative exercise (90 min once a week) and massage

(30 min twice a week). Over the subsequent 3 months, patients

participated in high-intensity physical exercise for 90 min

followed by 30 min of relaxation exercise three times a week. The

high-intensity physical exercise sessions comprised three

components: 30 min of warm-up exercises, 45 min of resistance

exercise and 15 min of cardiovascular exercise. All physical

exercise was supervised by trained specialist nurses. Details on

low- and high-intensity physical exercise are provided in Table SI. iii) Telephone counseling: Each

participant was assigned a nurse for the 6-month study period.

Counseling sessions were performed weekly during the first three

weeks, every other week for one month thereafter and then monthly.

Each telephone session had a duration of 15–30 min and served to

provide social support and enhance self-efficacy (encourage

patients to actively perform activities to promote their health).

During each telephone call, the nurse worked with the patient to

monitor progress, explore strategies for overcoming barriers and

asked relevant questions about rehabilitation. iv) Regular

examination: Patients were instructed to regularly undergo the

scheduled examinations, including imaging, blood analysis and

colonoscopy, once every two months for six months to manage any

abnormalities. v) Care activities: Patients and family members as

the primary caregivers were invited to the join the monthly

workshop and the nurse communicated with them to resolve issues

that they encountered in the interim period and provided detailed

advice on points including how to maintain a healthy diet, control

body weight and keep a positive mood. In addition, during the care

activities, caregivers were provided with lessons regarding how to

help patients complete their daily physical exercise.

| Table I.Contents of the incremental patient

care program. |

Table I.

Contents of the incremental patient

care program.

| Item | Frequency and

duration | Core content |

|---|

| Patient health

education | Once every 2 months

for 6 months | Training for

knowledge of disease and self-care |

| Physical

exercise | Low-intensity

physical exercise for 3 months, followed by high-intensity physical

exercise for 3 months | Recovery of physical

function |

| Telephone

counselling | Weekly for 3 weeks,

every other week for 1 month and monthly for 4 months | Emotional

support |

| Regular

examination | Once every 2 months

for 6 months | Surveillance for

disease |

| Care activities | Monthly for 6

months | Close communication

with patients to help them to solve problems |

Information collection

After enrolment in the present study, baseline

information was collected from all patients, which included the

following: a) Demographic characteristics: Age, gender and highest

education; and b) Clinical and pathological characteristics:

Smoking and drinking status, hypertension, hyperlipidemia,

diabetes, pathological grade, tumor size and TNM stage (according

to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer

Staging Manual) (16). In the

present study, the personal information of the patients, including

the demographic and clinicopathological characteristics, were

collected from the patients' medical records, and the Hospital

Anxiety and Depression Scale-anxiety (HADS-A; Table SII), HADS-depression (HADS-D;

Table SII) as well as QoL score

(Table SIII) were from

questionaires completed at the clinic.

Evaluation of anxiety and

depression

Anxiety refers to an emotion that is featured by an

unpleasant state of inner turmoil and is often accompanied by

nervous behavior, including pacing back and forth, somatic

complaints and rumination, or unpleasant feelings of dread over

anticipated events (17). Depression

refers to a state of low mood and aversion to activity, which may

affect a person's thoughts, behavior (sucha as total loss of

interest in enjoyable activities or socializing), feelings (such as

feelings of loneliness, sadness, guilt or worthlessness) and sense

of well-being (18). HADS-A scores

and HADS-D scores were determined to assess anxiety and depression

among the patients. These were assessed at baseline [month 0 (M0)],

M1, M3 and M6. The HADS-A and HADS-D subscales consisted of seven

questions that are scored individually from 0 to 3 points,

resulting in subscale scores ranging from 0 to 21 points, with the

following grade classification: 0–7, no anxiety/depression; 8–10,

light anxiety/depression; 11–14, moderate anxiety/depression;

15–21, severe anxiety/depression (19).

Evaluation of QoL

QoL refers to the satisfaction of patients,

outlining negative and positive features of life. (20). The European Organization for Research

and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC

QLQ-C30 Scale) was used to assess the QoL of patients. The EORTC

QLQ-C30 Scale consists of 30 items, including five functions,

symptoms and financial implications subscales. The first 28 items

of the questionnaire used a 4-point Likert-type response scale

ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Items 29 and 30,

which assess global health status/QoL, use a response scale ranging

from 1 (very poor) to 7 (excellent). All raw data were transformed

to a 0–100-point scale. Higher mean scores for the functional

scales and the global health status/QoL scales indicate better

functioning and overall QoL, whereas a high score for the symptom

scale/single-item scale represents a high level of symptom distress

(21).

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation was based on a previous

study (6). Under the requirement of

a 90% statistical power to detect a difference of 10% in the

percentage of patients with depression at M6 between the IPCP group

and control group, assuming 25% patients in the IPCP group and 35%

patients in the control group exhibited depression at M6, with a

two-sided 5% level of significance (α), a sample size of 110

participants was required in each group. Accounting for loss to

follow-up of ~26%, 149 patients were enrolled in each group.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 software (IBM

Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), Office 2010 software (Microsoft Corp.,

Redmond, WA, USA) and GraphPad prim 6.0 (GraphPad Inc., La Jolla,

CA, USA). Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or

n (%). Comparisons between groups were performed using Student's

t-tests or Chi-square tests. Correlations were determined using

Pearson correlation analysis. In addition, the statistics were

based on an intent-to-treat analysis (22). P<0.05 was considered to indicate

statistical significance.

Results

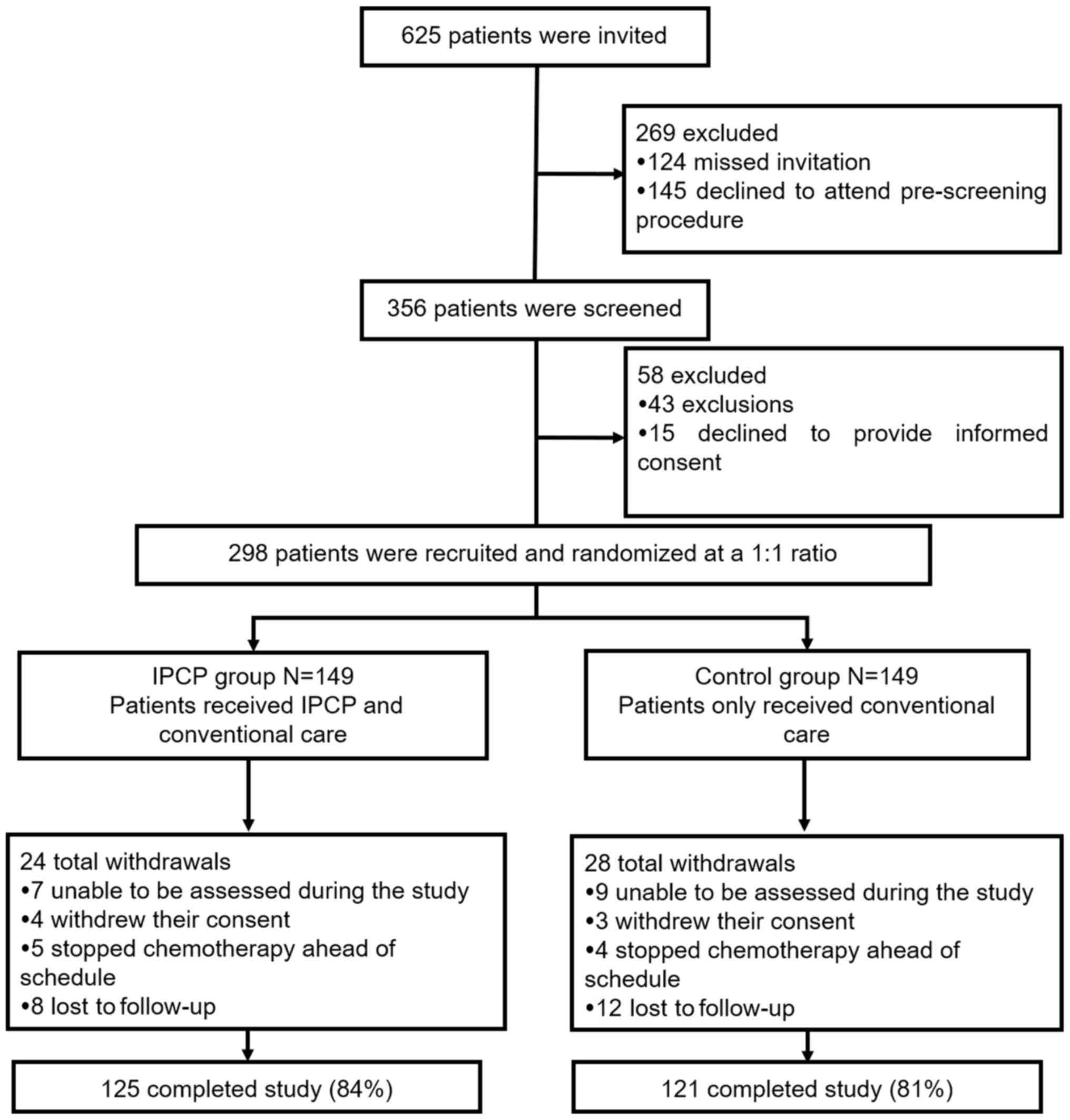

Study flow

A total of 625 patients were invited to participate

in the present study, of which while 269 patients were excluded,

including 124 who missed their invitation and 145 who declined to

attend the pre-screening. A total of 356 patients screened for

eligibility, 58 of which were excluded, including 43 who did not

meet all of the inclusion criteria and 15 who refused to provide

informed consent. The remaining 298 patients were then randomized

at a 1:1 ratio. Among these, 149 received IPCP and conventional

care (IPCP group), whereas the other 149 received only conventional

care (control group). In the IPCP group, 24 patients dropped out

during the study period, including 7 who were unable to be assessed

during the study, 4 who withdrew their consent, 5 who stopped

chemotherapy ahead of schedule and 8 who were lost to follow-up,

resulting in 125 patients (84%) who completed the entire study. In

the control group, there were a total of 28 dropouts, including 9

cases who were unable to be assessed during the study, 3 who

withdrew their consent, 4 who stopped chemotherapy ahead of

schedule and 12 who were lost to follow-up, resulting in 121

patients (81%) who ultimately completed the study (Fig. 1). In the present study, the

statistics were based on an intent-to-treat analysis (22). For patients who did not complete the

entire study, the last available values were used to represent

subsequent missing evaluation indexes.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the patients in the

control and IPCP groups are provided in Table II. No differences were observed in

demographic and clinical characteristics between the IPCP group and

the control group (all P>0.05). The mean age was 60.06±11.00

years in the IPCP group and 58.47±12.52 years in the control group.

The amount of patients with hypertension, hyperlipidemia and

diabetes was 48 (32.2%), 35 (23.5%) and 11 (7.4%), respectively, in

the IPCP group and 58 (38.9%), 36 (24.2%) and 14 (9.4%),

respectively, in the control group. In addition, there were no

differences between groups in HADS-A scores, HADS-A grade, HADS-D

score, HADS-D grade and EORTC QLQ-C30 scale scores (all

P>0.05).

| Table II.Baseline characteristics of patients

in the IPCP group and the control group. |

Table II.

Baseline characteristics of patients

in the IPCP group and the control group.

| Item | IPCP group

(n=149) | Control group

(n=149) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | 60.06±11.00 | 58.47±12.52 | 0.245 |

| Gender

(male/female) | 98/51 | 91/58 | 0.400 |

| Highest

education |

|

| 0.362 |

| Primary

school or less | 74 (48.3) | 73 (49.0) |

|

| High

school | 42 (28.2) | 50 (33.6) |

|

|

Undergraduate | 35 (23.5) | 26 (17.4) |

|

|

Graduate or above | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| Smoking | 58 (38.9) | 68 (45.6) | 0.241 |

| Drinking | 57 (38.3) | 60 (40.3) | 0.722 |

| Hypertension | 48 (32.2) | 58 (38.9) | 0.226 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 35 (23.5) | 36 (24.2) | 0.892 |

| Diabetes | 11 (7.4) | 14 (9.4) | 0.531 |

| Pathological

grade |

|

| 0.466 |

| 1 | 14 (9.4) | 13 (8.7) |

|

| 2 | 88 (59.1) | 98 (65.8) |

|

| 3 | 47 (31.5) | 38 (25.5) |

|

| Tumor size

(cm) | 4.68±1.28 | 4.67±1.34 | 0.940 |

| TNM stage |

|

| 0.104 |

| II | 72 (48.3) | 86 (57.7) |

|

|

III | 77 (51.7) | 63 (42.3) |

|

| HADS-anxiety

score |

|

|

|

| No

anxiety (score, 0–7) | 110 (73.8) | 118 (79.2) | 0.274 |

| Anxiety

(score, 8–21) | 39 (26.2) | 31 (20.8) |

|

| HADS-anxiety

grade |

|

| 0.308 |

| Light

grade (8–10 score) | 26 (17.4) | 15 (10.1) |

|

|

Moderate grade (11–14

score) | 11 (7.5) | 13 (8.7) |

|

| Severe

grade (15–21 score) | 2 (1.3) | 3 (2.0) |

|

| HADS-depression

score |

|

|

|

| No

depression (score, 0–7) | 98 (65.8) | 103 (69.1) | 0.536 |

|

Depression (score, 8–21) | 51 (34.2) | 46 (30.9) |

|

| HADS-depression

grade |

|

|

|

| Light

(score, 8–10) | 33 (22.1) | 24 (16.1) | 0.278 |

|

Moderate (score, 11–14) | 15 (10.1) | 14 (9.4) |

|

| Severe

(score, 15–21) | 3 (2.0) | 8 (5.4) |

|

| EORTC QLQ-C30

scale |

|

|

|

| Global

Health Status score | 63.7±14.5 | 62.9±15.8 | 0.630 |

|

Functions score | 69.9±16.5 | 69.9±18.9 | 0.995 |

|

Symptoms score | 33.3±16.9 | 30.8±14.9 | 0.189 |

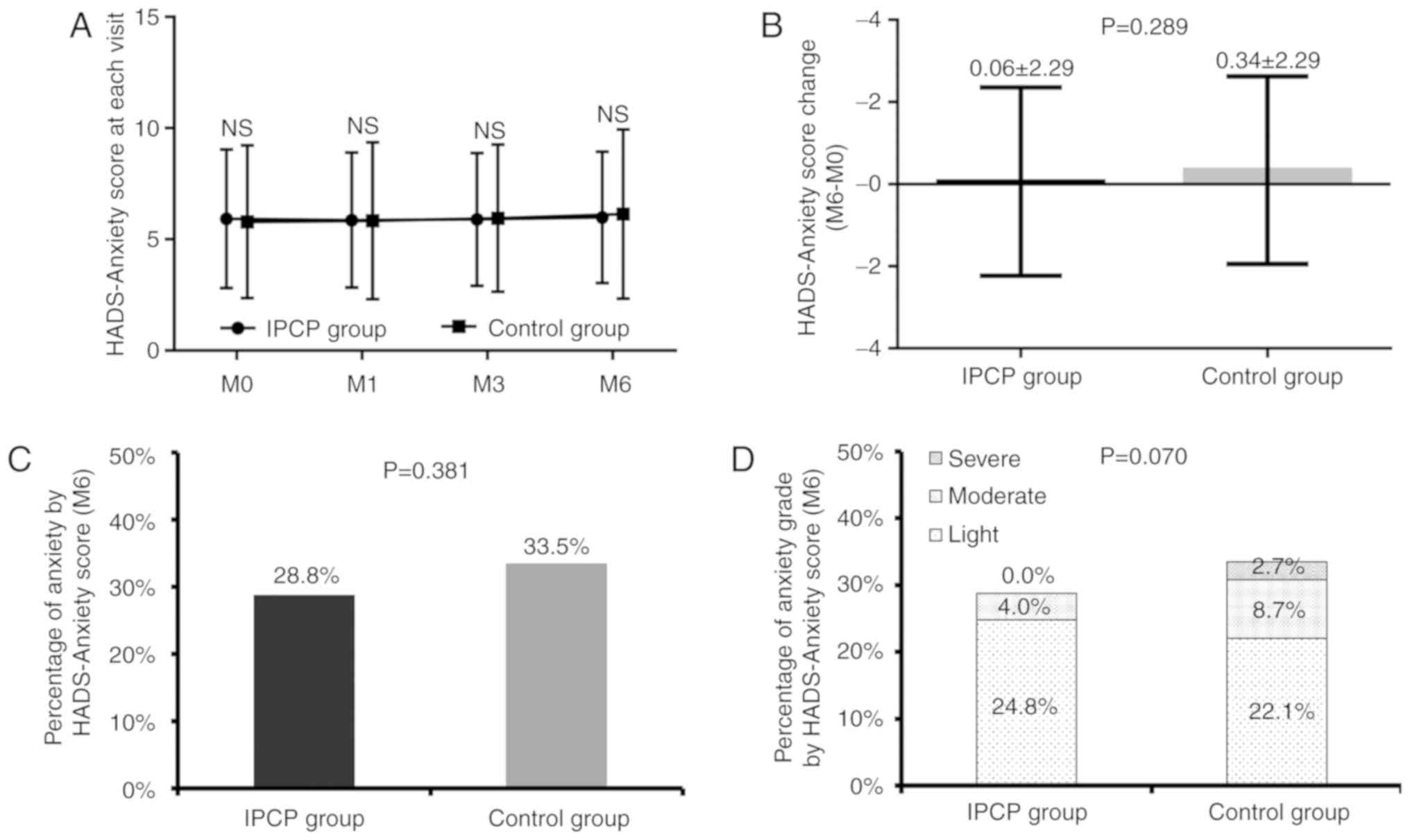

Comparison of anxiety scores between

the IPCP group and control group

There were no differences between groups in HADS-A

scores at each visit (all P>0.05; Fig. 2A), HADS-A change score from baseline

(M0) to M6 (P=0.289; Fig. 2B) or in

the percentage of patients with anxiety according to HADS-A score

at M6 (P=0.381; Fig. 2C). Compared

with that in the control group, the anxiety score at M6 in IPCP

participants appeared to have decreased but the difference was not

statistically significant (P=0.070; Fig.

2D).

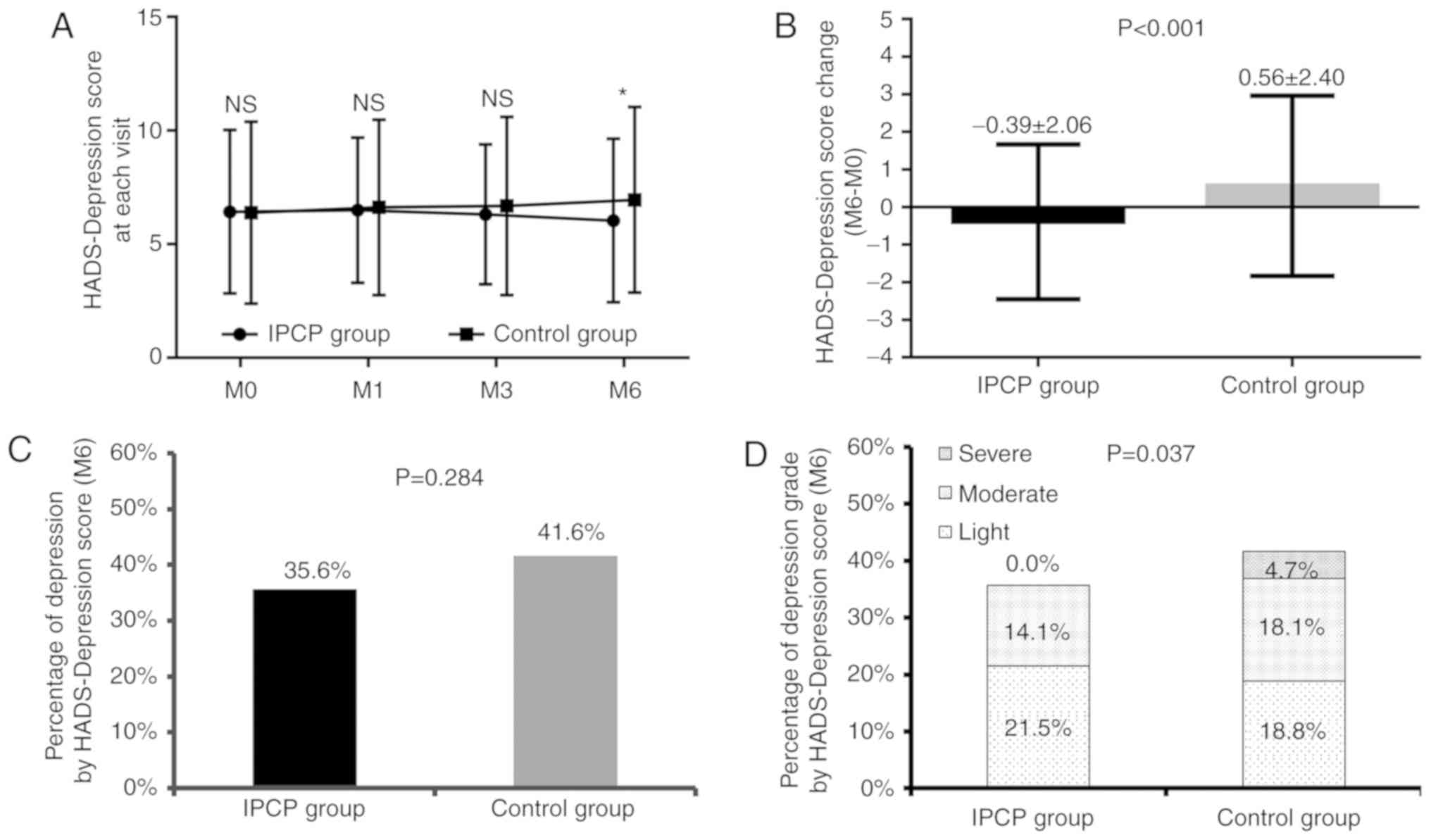

Comparison of depression scores

between the IPCP group and control group

No differences were identified in HADS-D scores at

M0, M1 or M3 between the IPCP and control groups (all P>0.05;

Fig. 3A), although they were lower

in the IPCP group than those in the control group at M6 (P<0.05;

Fig. 3A). As for HADS-D change

scores (M6-M0) between the two groups, they were decreased in the

IPCP group compared with those in the control group (P<0.001;

Fig. 3B). There was no difference

between the groups in the percentage of participants with

depression at M6 according to their HADS-D scores (P=0.284;

Fig. 3C). In addition, the

depression grade was reduced in the IPCP group compared with the

control group (P=0.037; Fig.

3D).

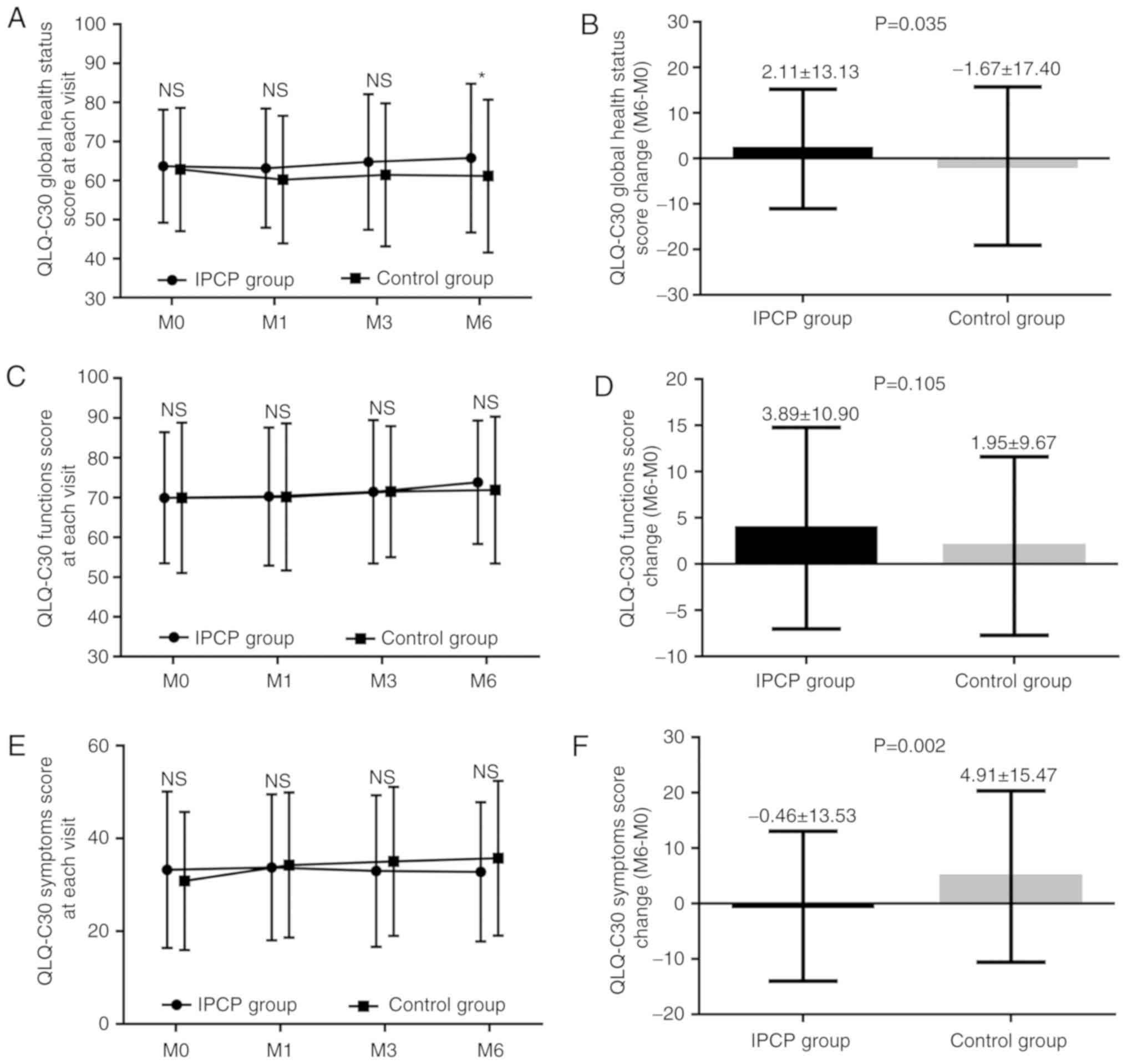

Comparison of QoL between the IPCP

group and control group

No difference in the QLQ-C30 global health status

scores was identified between the IPCP and control groups at M0, M1

or M3 (all P>0.05; Fig. 4A),

although they were higher in the IPCP group at M6 compared with

those in the control group (P<0.05; Fig. 4A). The QLQ-C30 global health status

change scores (M6-M0) exhibited a greater increase in the IPCP

group compared with that in the control group (P=0.035; Fig. 4B). Regarding the QLQ-C30 function

scores, there were no differences between the groups at each visit

(all P>0.05; Fig. 4C), and there

was also no significant difference in the change score (M0-M6)

between the two groups (P=0.105; Fig.

4D). As for the QLQ-C30 symptom scores, no differences between

the groups were present at each visit (all P>0.05), but the

QLQ-C30 symptom change scores (M6-M0) were decreased in the IPCP

group compared with those in the control group (P=0.002; Fig. 4F).

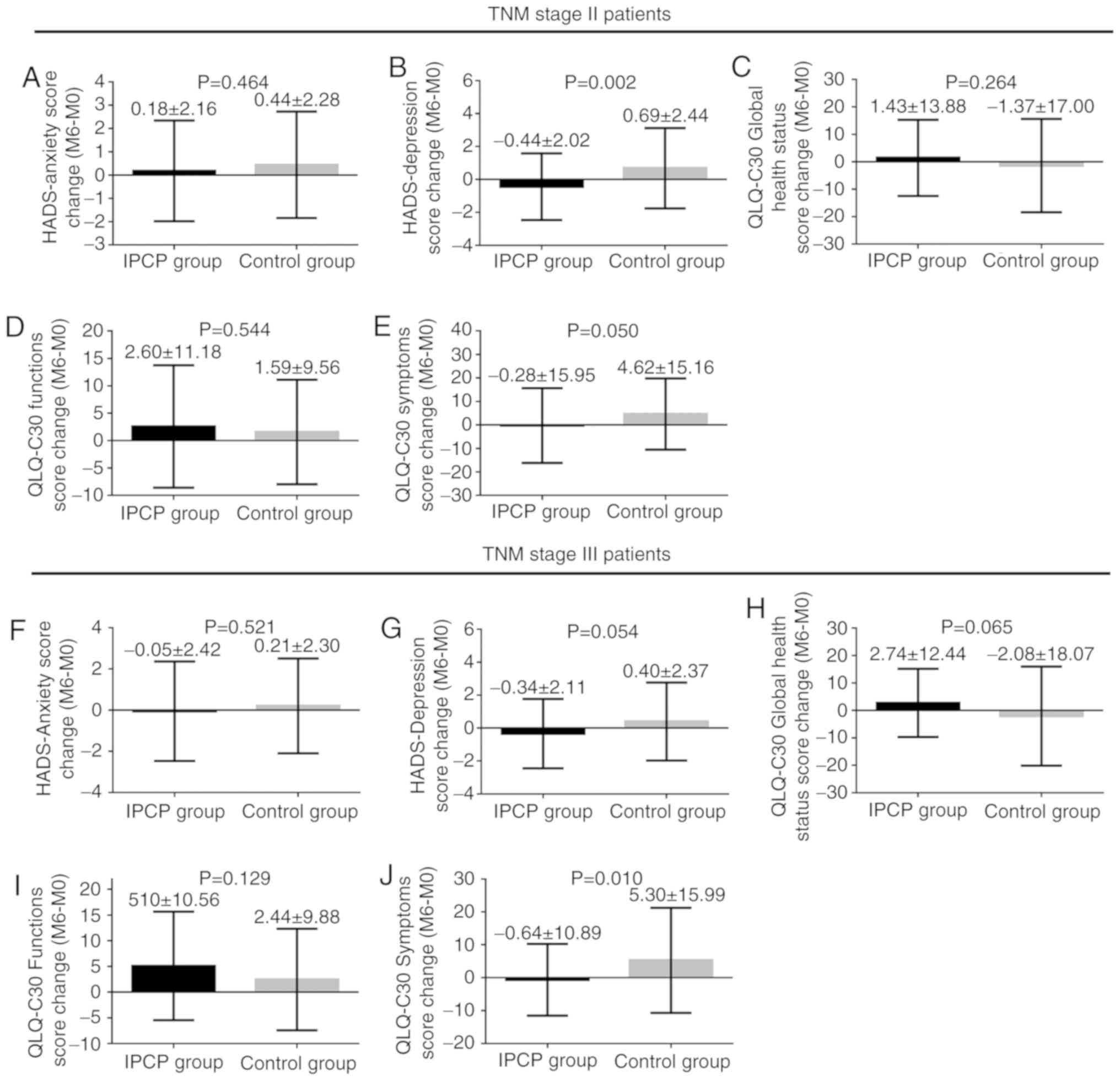

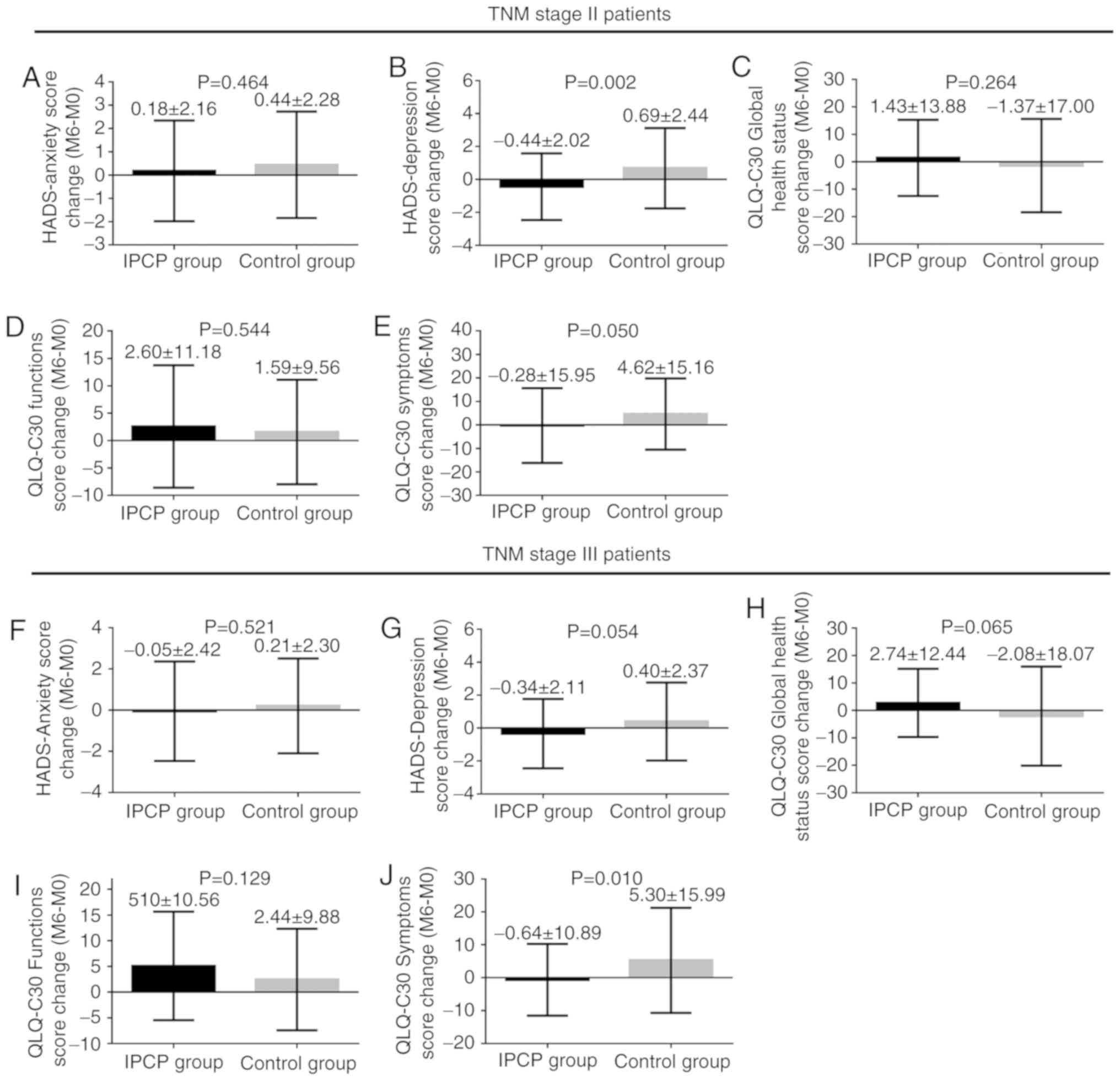

Subgroup analysis between TNM stage II

and III patients

To assess the impact of the TNM stage on the above

analysis, the patients were stratified into TNM stage II and III

groups (Fig. 5). For TNM stage II

patients, the HADS-D change scores (M6-M0) (P=0.002; Fig. 5B) and QLQ-C30 symptom change scores

(M6-M0) (P=0.050; Fig. 5E) were

decreased in the IPCP group compared with those in the control

group. However, no difference was observed in the change in HADS-A

scores (P=0.464; Fig. 5A), QLQ-C30

global health status scores (P=0.264; Fig. 5C) or QLQ-C30 function scores

(P=0.544; Fig. 5D) from baseline to

M6 between the two groups.

| Figure 5.Subgroup analysis between TNM stage II

and stage III patients. (A-E) For TNM stage II patients, no

difference was observed in the change of (A) HADS-anxiety score,

(C) QLQ-C30 global health status score and (D) QLQ-C30 function

score from baseline (M0) to M6 between groups. (B) The

HADS-depression score change (M6-M0) and (E) the QLQ-C30 symptoms

score (M6-M0) was decreased in the IPCP group compared with those

in the control group. (F-J) As for TNM stage III patients, (J) the

QLQ-C30 symptoms score (M6-M0) was decreased in the IPCP group

compared with that in the control group and (G) the HADS-depression

score change (M6-M0) was numerically decreased, while (H) the

QLQ-C30 global health status score change (M6-M0) was numerically

increased in the IPCP group compared with that in the control

group. (F and I) There was no difference in the change of

HADS-anxiety score and QLQ-C30 functions score from baseline (M0)

to M6 between groups. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation. NS, no significance; IPCP, incremental patient care

program; M, month; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale;

TNM, tumor-nodes-metastasis; QLQ-C30, European Organization for

Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire. |

For TNM stage III patients, the QLQ-C30 symptom

scores (M6-M0) exhibited a greater decrease in the IPCP group

compared with those in the control group (P=0.010; Fig. 5J), as did the HADS-depression change

scores (M6-M0) (P=0.054; Fig. 5G),

whereas the QLQ-C30 global health status scores (M6-M0) (P=0.065;

Fig. 5H) exhibited a greater

increase in the IPCP group compared with those in the control

group. There was no difference in the change of HADS-A scores or

QLQ-C30 function scores from baseline to M6 between the groups

(P=0.129; Fig. 5F and I). The effect

of IPCP intervention on anxiety, depression and QoL scores and

their rate is also provided in Tables

SIV and SV. In addition,

changes in anxiety, depression and QoL score in the subgroups are

also presented in Table SVI.

Furthermore, correlations between HADS-A score, HADS-D score and

QLQ-C30 scores at M0 and M6 are displayed in Table SVII; however, no significant

differences were identified in control group at baseline and at 6

months. There was a significant negative correlation between HADS-A

and QLQ-C30 function scores at baseline in the IPCP group

(P=0.024), but not at 6 months.

Discussion

The major results of the present study were as

follows: i) The IPCP group experienced an insignificant decrease in

anxiety, as assessed by the HADS-A scores, and significantly

reduced depression, as assessed by the HADS-D scores; ii)

participants receiving IPCP experienced improved QoL, as assessed

by the QLQ-C30.

Recently, the survival of CRC patients has been

reported to be increased, while affected patients are at high risk

of experiencing psychosocial problems (such as depression and

anxiety), which has a negative impact on their health-associated

QoL (23,24). A previous clinical study illustrates

that CRC patients exhibited an obviously higher prevalence of

depression (19.0% vs. 12.8%) and anxiety (20.9% vs. 11.8%) compared

with cancer-free age- and sex-matched individuals (23). Another study revealed a negative

association between the patients' emotional functioning score and

HADS-A score, as well as HADS-D score, and the correlation between

HADS-D and QoL dimensions was significantly higher compared with

the correlation between QoL and HADS-A (24). These previous clinical studies

indicate that psychosocial disorders (including anxiety and

depression) are conditions that negatively influence the QoL of CRC

patients.

Based on several previous studies, HADS-A score,

HADS-D score and the EORTC QLQ-C30 scale are reliable measurement

tools for evaluating anxiety, depression and QoL of cancer patients

(25,26).

In clinical practice, care interventions have been

confirmed to be beneficial for maintaining psychological health in

cancer patients. For instance, one study reported that the health

education level of patients prior to treatment initiation was

associated with decreased anxiety and depression, as assessed by

HADS-A/D scores (6). Another study

revealed that, compared with the baseline, the HADS-D score was

decreased in patients with CRC after a nurse-assisted screening and

referral for participation in a care program (27). Although certain previous studies have

demonstrated the positive impact of care interventions on mental

health among patients with CRC, only few have investigated the

effects of an IPCP on anxiety and depression in patients with CRC

receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. In the present study, a novel IPCP

was designed in three steps as follows: i) After a literature

search, the common care methods for carcinoma were reviewed. ii)

The detailed program was designed and three nurses with nursing

experience of >10 years at the department of digestion were

invited to rate and make decisions regarding the intervention

program; the final result was selected as the final program. iii) A

preliminary study was performed to confirm the effectiveness of the

IPCP in 10 patients with CRC receiving adjuvant chemotherapy, and

its efficacy was indicated to be good in these patients. The

difference in the contents between IPCP and traditional care were

that i) IPCP was performed more intensively, while, for traditional

care, the post-operative medicine management and usual advice on

post-operative rehabilitation were provided according to patients'

requirements (28); ii) IPCP

consisted of patient health education, physical exercise, telephone

counseling, regular examination as well as care activities. iii)

During the care activities, all caregivers were provided with

lessons with regard to how to help patients complete their daily

exercise. The present study demonstrated the possible efficacy of

IPCP in slightly decreasing anxiety and reducing depression. The

possible reasons were as follows: First, IPCP included regular

patient health education, which may provide correct information and

knowledge on risk factors, treatment and prognosis of CRC to

patients, thereby decreasing their fear and confusion that may

arise from inaccurate information and rumors from unreliable

websites, thus reducing their risk of anxiety and depression.

Furthermore, IPCP is a care intervention with low- and

high-intensity physical exercise, and the physical exercise may

promote the motor and sensory recovery thereby increasing patient

confidence and reducing the risk of anxiety and depression

(29). Finally, IPCP is a program

for patients that relies on assistance from caregivers and nurses,

thus providing more opportunities for patients to increase

communication. Increased communication between patients and nurses

may contribute to increased psychological health, including

decreased anxiety and depression, among patients with CRC receiving

adjuvant chemotherapy.

QoL is a critical outcome measure in the assessment

of health status and treatment efficacy in different patients, in

including patients with cancer and rheumatoid arthritis. According

to accumulating evidence, favorable outcomes of care interventions

regarding QoL have been identified in cancer patients. For

instance, one previous study suggested that QoL, as assessed by the

EORTC QLQ-C30 and EuroQol-5 dimensions scales, was improved among

patients receiving chemotherapy for CRC after they received health

education prior to treatment initiation (6). According to a review of 11 studies,

various forms of psychosocial intervention, including health

educational interventions, cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation

exercise and supportive group therapy, contribute to a decreased

length of hospital stay, decreased days to stoma proficiency and

decreased hospital-associated anxiety and depression, as well as

improved QoL outcomes in patients with CRC (30). Therefore, for patients with CRC, care

interventions have a positive effect regarding the improvement of

QoL. In the present study, the influence of IPCP on QoL was also

explored, and assessment via the QLQ-C30 global health status

scores, QLQ-C30 function scores and QLQ-C30 symptom scores

suggested that IPCP contributed to an improvement in QoL among

patients with CRC receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. The first

possible reason for this effect is that IPCP is a safe and

effective way to provide low- and high-intensity physical exercise

that contributes to functional recovery and to achieve long-term

improvements in activities of daily living, thereby increasing

physical health and improving QoL of patients with CRC.

Furthermore, IPCP has an important role in maintaining a good

environment for increasing communication among patients, family

members and nurses, thereby promoting mutual understanding and

cooperation and decreasing anxiety and depression, thus improving

mental health and increasing QoL.

Of note, the present study had certain limitations.

First, the sample size was relatively small, leading to low

statistical power. Furthermore, all patients enrolled in the

present study were from a single centre; thus, further studies

should be performed recruiting patients from multiple centres.

Finally, the duration of follow-up was relatively short; thus, the

long-term effects on IPCP on anxiety, depression and QoL in

patients with CRC remain elusive.

In conclusion, IPCP led to a slight decrease in

anxiety to a certain extent and contributed to a significant

reduction in depression and an improvement in QoL in patients with

CRC receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. The present study provided a

novel IPCP that may serve as an efficient care program for outcome

improvements in CRC.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

XL designed the experiment, JL and XL performed the

experiments and wrote the manuscript, and XL analyzed the data and

revised the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was performed according to the

tenets established in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved

by the Ethics Committee of the 2nd Affiliated Hospital of Harbin

Medical University (Harbin, China). Written informed consent was

obtained from all patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Brenner H, Kloor M and Pox CP: Colorectal

cancer. Lancet. 383:1490–1502. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D,

Mathers C and Parkin DM: Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in

2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 127:2893–2917. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J,

Lortet-Tieulent J and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA

Cancer J Clin. 65:87–108. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 64:9–29. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gonzalez-Saenz de Tejada M, Bilbao A, Baré

M, Briones E, Sarasqueta C, Quintana JM and Escobar A; CARESS-CCR

Group, : Association between social support, functional status, and

change in health-related quality of life and changes in anxiety and

depression in colorectal cancer patients. Psychooncology.

26:1263–1269. 2017. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Polat U, Arpaci A, Demir S, Erdal S and

Yalcin S: Evaluation of quality of life and anxiety and depression

levels in patients receiving chemotherapy for colorectal cancer:

Impact of patient health education before treatment initiation. J

Gastrointest Oncol. 5:270–275. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wan Puteh SE, Saad NM, Aljunid SM, Abdul

Manaf MR, Sulong S, Sagap I, Ismail F and Muhammad Annuar MA:

Quality of life in Malaysian colorectal cancer patients. Asia Pac

Psychiatry. 5 (Suppl 1):S110–S117. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Tsunoda A, Nakao K, Hiratsuka K, Yasuda N,

Shibusawa M and Kusano M: Anxiety, depression and quality of life

in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 10:411–417. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Alacacioglu A, Binicier O, Gungor O, Oztop

I, Dirioz M and Yilmaz U: Quality of life, anxiety, and depression

in Turkish colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer.

18:417–421. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Medeiros M, Oshima CT and Forones NM:

Depression and anxiety in colorectal cancer patients. J

Gastrointest Cancer. 41:179–184. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Demark-Wahnefried W and Jones LW:

Promoting a healthy lifestyle among cancer survivors. Hematol Oncol

Clin North Am. 22:319–342. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Morey MC, Snyder DC, Sloane R, Cohen HJ,

Peterson B, Hartman TJ, Miller P, Mitchell DC and Demark-Wahnefried

W: Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes

among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: A

randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 301:1883–1891. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Allgayer H, Owen RW, Nair J, Spiegelhalder

B, Streit J, Reichel C and Bartsch H: Short-term moderate exercise

programs reduce oxidative DNA damage as determined by

high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass

spectrometry in patients with colorectal carcinoma following

primary treatment. Scand J Gastroenterol. 43:971–978. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Xiao F, Song X, Chen Q, Dai Y, Xu R, Qiu C

and Guo Q: Effectiveness of psychological interventions on

depression in patients after breast cancer surgery: A meta-analysis

of randomized controlled trials. Clin Breast Cancer. 17:171–179.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li Z, Geng W, Yin J and Zhang J: Effect of

one comprehensive education course to lower anxiety and depression

among Chinese breast cancer patients during the postoperative

radiotherapy period-one randomized clinical trial. Radiat Oncol.

13:1112018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG,

Greene FL and Trotti A III: AJCC Cancer Staeging Manual. 7th. New

York: Springer; 2010

|

|

17

|

Seligman MEP, Walker EF and Rosenhan DL:

Abnormal Psychology. 4th. W.W. Norton & Company; New York, NY:

2001

|

|

18

|

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric

Association. 2013.

|

|

19

|

Zigmond AS and Snaith RP: The hospital

anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 67:361–370.

1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Barcaccia B: ‘Quality Of Life: Everyone

Wants It, But What Is It?’. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tung HY, Chao TB, Lin YH, Wu SF, Lee HY,

Ching CY, Hung KW and Lin TJ: Depression, fatigue, and QoL in

colorectal cancer patients during and after treatment. West J Nurs

Res. 38:893–908. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Van Vulpen JK, Velthuis MJ, Steins

Bisschop CN, Travier N, Van Den Buijs BJ, Backx FJ, Los M, Erdkamp

FL, Bloemendal HJ, Koopman M, et al: Effects of an exercise program

in colon cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Med Sci Sports

Exerc. 48:767–775. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Mols F, Schoormans D, de Hingh I,

Oerlemans S and Husson O: Symptoms of anxiety and depression among

colorectal cancer survivors from the population-based, longitudinal

PROFILES Registry: Prevalence, predictors, and impact on quality of

life. Cancer. 124:2621–2628. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Aminisani N, Nikbakht H, Asghari

Jafarabadi M and Shamshirgaran SM: Depression, anxiety, and health

related quality of life among colorectal cancer survivors. J

Gastrointest Oncol. 8:81–88. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Thomas BC, Devi N, Sarita GP, Rita K,

Ramdas K, Hussain BM, Rejnish R and Pandey M: Reliability and

validity of the Malayalam hospital anxiety and depression scale

(HADS) in cancer patients. Indian J Med Res. 122:395–399.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Matsumoto T, Ohashi Y, Morita S, Kobayashi

K, Shibuya M, Yamaji Y, Eguchi K, Fukuoka M, Nagao K, Nishiwaki Y,

et al: The quality of life questionnaire for cancer patients

treated with anticancer drugs (QOL-ACD): Validity and reliability

in Japanese patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Qual

Life Res. 11:483–493. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Livingston PM, Craike MJ, White VM,

Hordern AJ, Jefford M, Botti MA, Lethborg C and Oldroyd JC: A

nurse-assisted screening and referral program for depression among

survivors of colorectal cancer: Feasibility study. Med J Aust 193

(5 Suppl). S83–S87. 2010.

|

|

28

|

Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y, Tanaka

S, Ito Y, Ajioka Y, Hamaguchi T, Hyodo I, Igarashi M, Ishida H, et

al: Japanese society for cancer of the colon and rectum (JSCCR)

guidelines 2014 for treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin

Oncol. 20:207–239. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Sheiner LB: Is intent-to-treat analysis

always (ever) enough? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 54:203–211. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hoon LS, Chi Sally CW and Hong-Gu H:

Effect of psychosocial interventions on outcomes of patients with

colorectal cancer: A review of the literature. Eur J Oncol Nurs.

17:883–891. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|